Kids telling a story

4 Benefits of kids telling their own stories by Rainforest Learning Centre

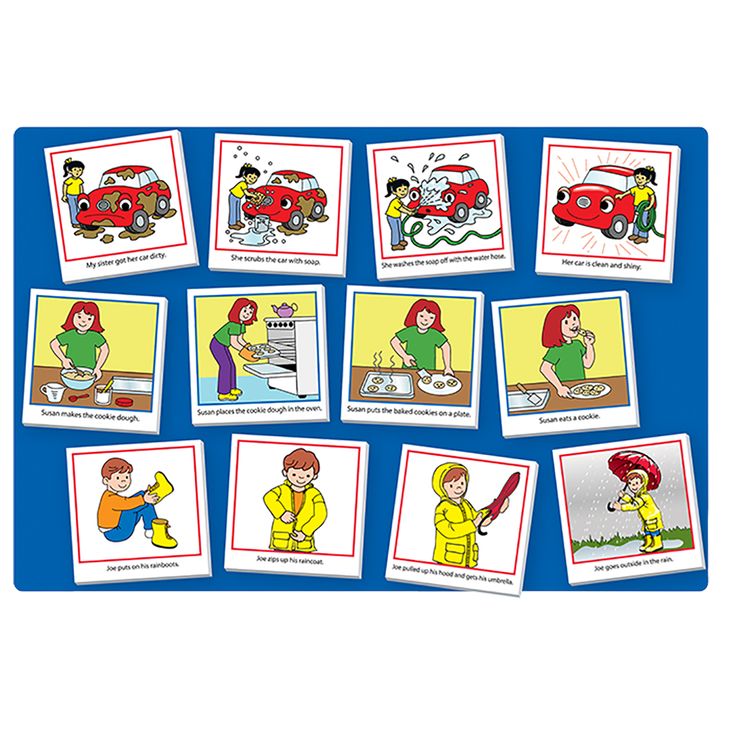

We often think of story time as adults telling kids stories, or reading storybooks. But we probably less often think of story time as an opportunity for kids to be creative. There are benefits to kids telling their own stories, however.

In this article, we’ll explain the pros of allowing kids to be the storyteller, and to make up their own stories to tell you, the adult.

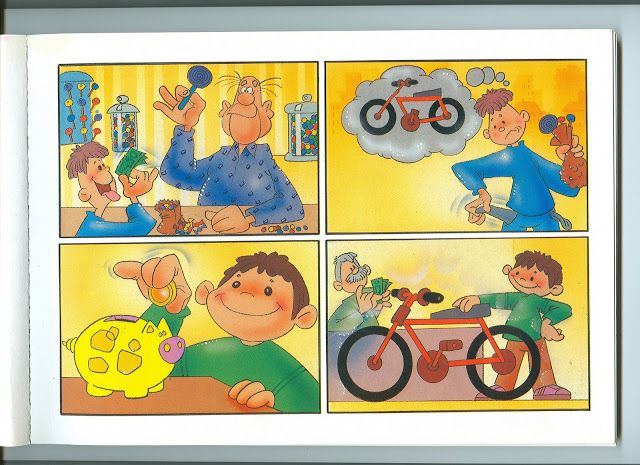

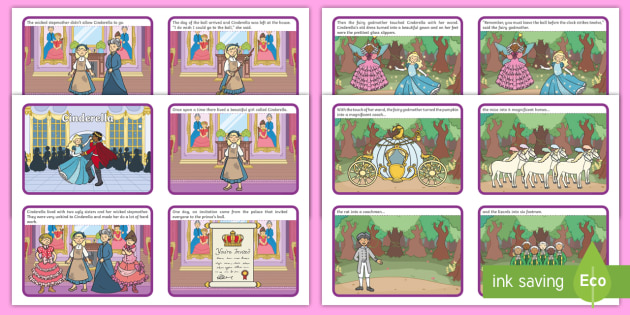

1) Kids telling their own stories fosters creative thinking

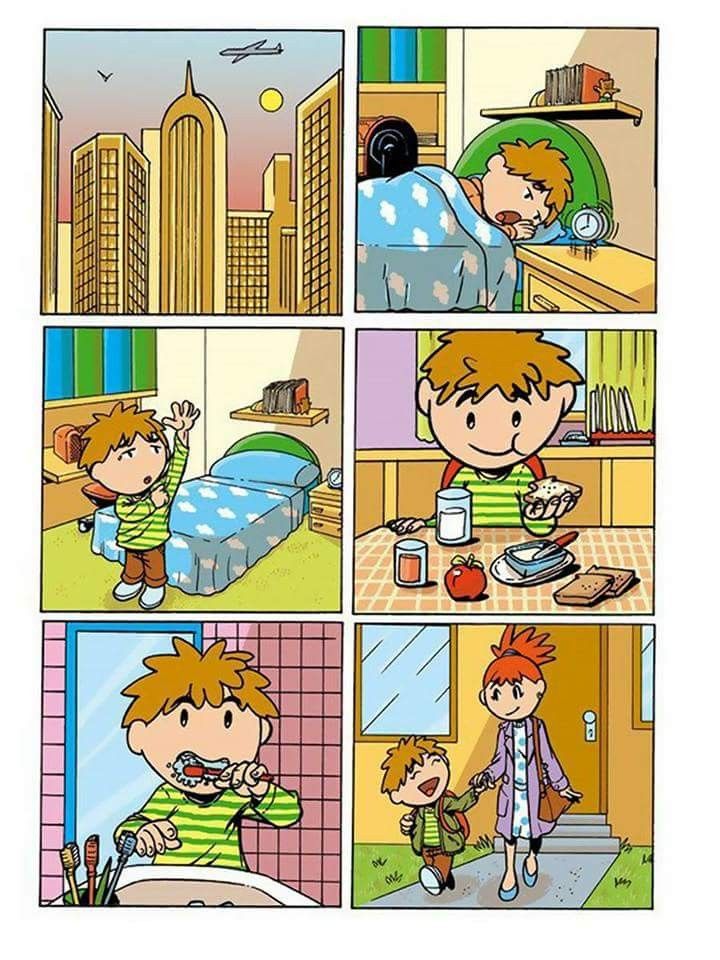

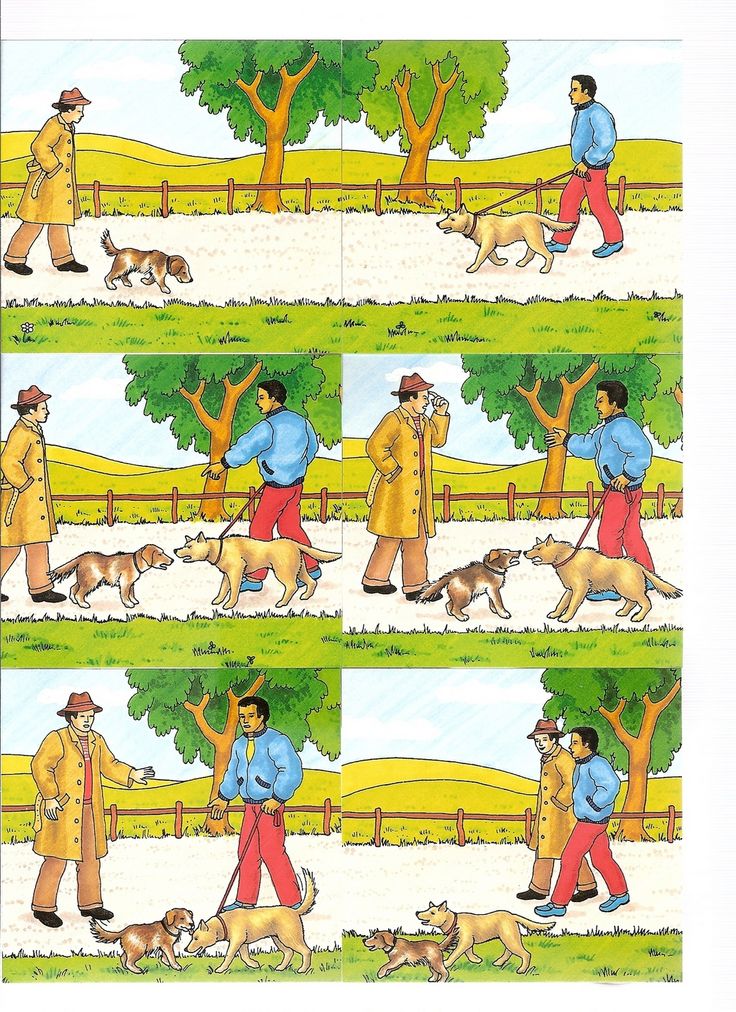

This is probably the most obvious point. When kids get a chance to make up and tell their own stories to adults, by necessity, they have to get creative. They have to come up with an interesting plot, some unique characters and their traits, and they have to think ahead of ‘what happens next’ in this story.

Imagination is a wide open world when kids tell their own stories – and that means that they can be the main protagonist, with untold, desired abilities and then go through experiences they dream of having. Or they can name characters after their best friends or siblings, out of affection. Or tell the story of their pet’s adventures in the outdoors when nobody’s watching. Making things up means coming up with ideas that no one has told them before. And this can be the starting point to even more creative thinking.

And, as Albert Einstein has said,

“Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution. It is, strictly speaking, a real factor in scientific research.”

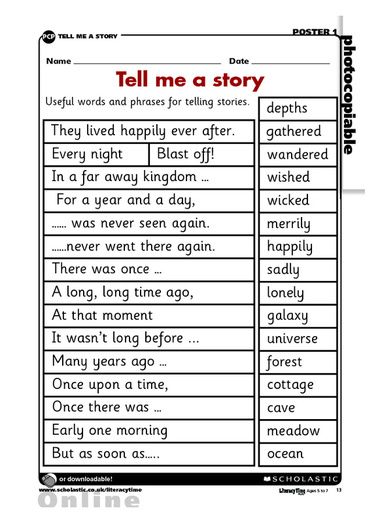

Of course, you can start kids off with the first sentence or two if they’re feeling stuck! But encouraging imagination through kids’ own storytelling can help open their minds to new creative ideas, according to Einstein.

2) Kids being the storyteller can develop language skills

But, stories don’t have to be made up to encourage creativity. Even finding the words to retell what really happened can encourage new ways of being able to express oneself. This is described as a benefit of a writer whose mother encouraged storytelling as a child. In addition to language skills, and exercised creativity, the writer realized about his mother’s strategy that:

This is described as a benefit of a writer whose mother encouraged storytelling as a child. In addition to language skills, and exercised creativity, the writer realized about his mother’s strategy that:

“What seemed like just a game to us was really a fantastic learning opportunity. She was teaching us to translate the information and knowledge we had picked up throughout the day into words.”

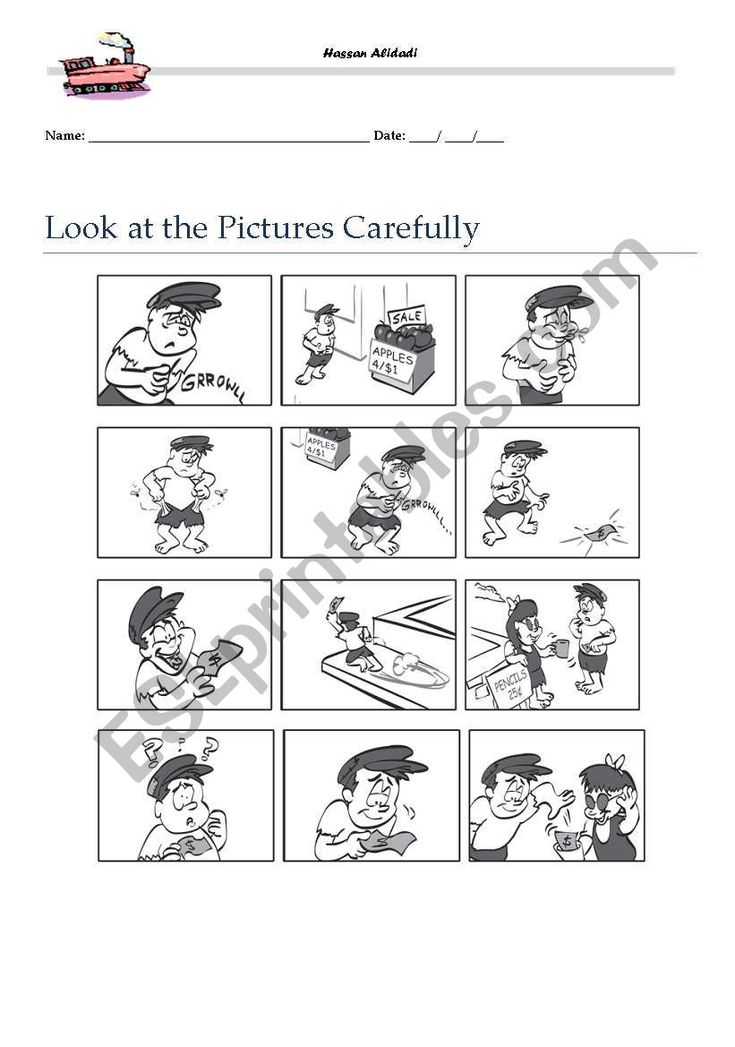

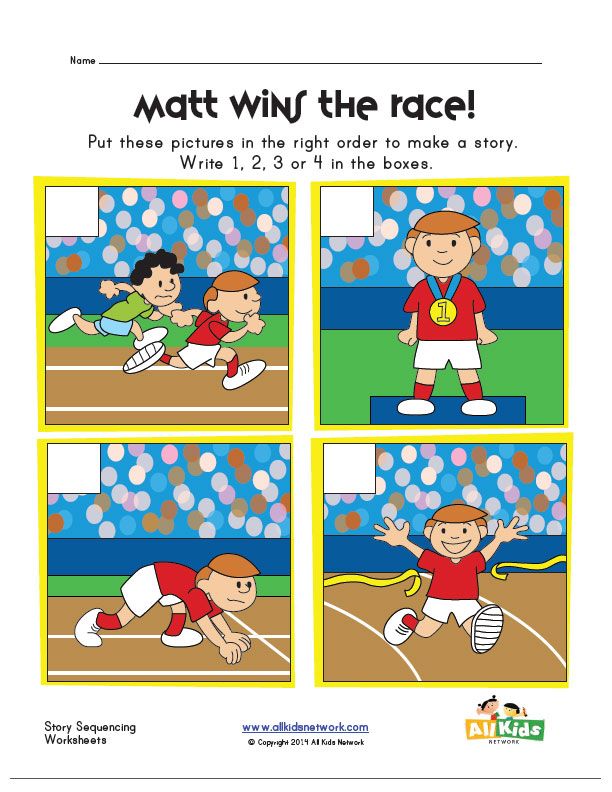

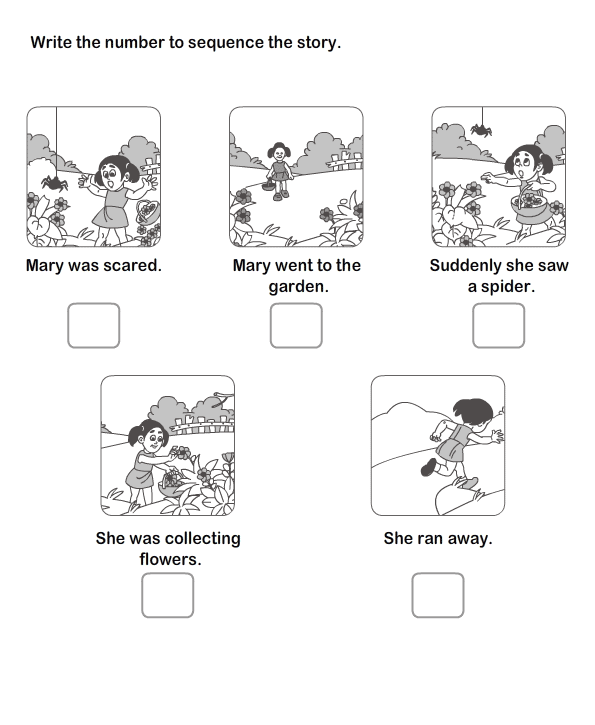

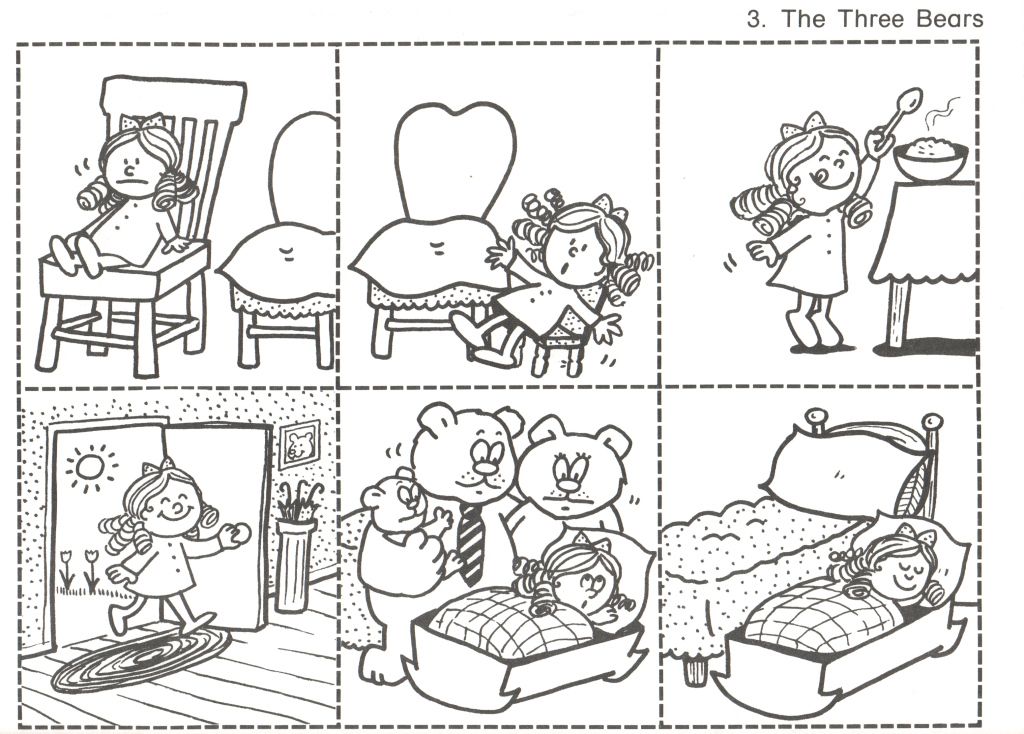

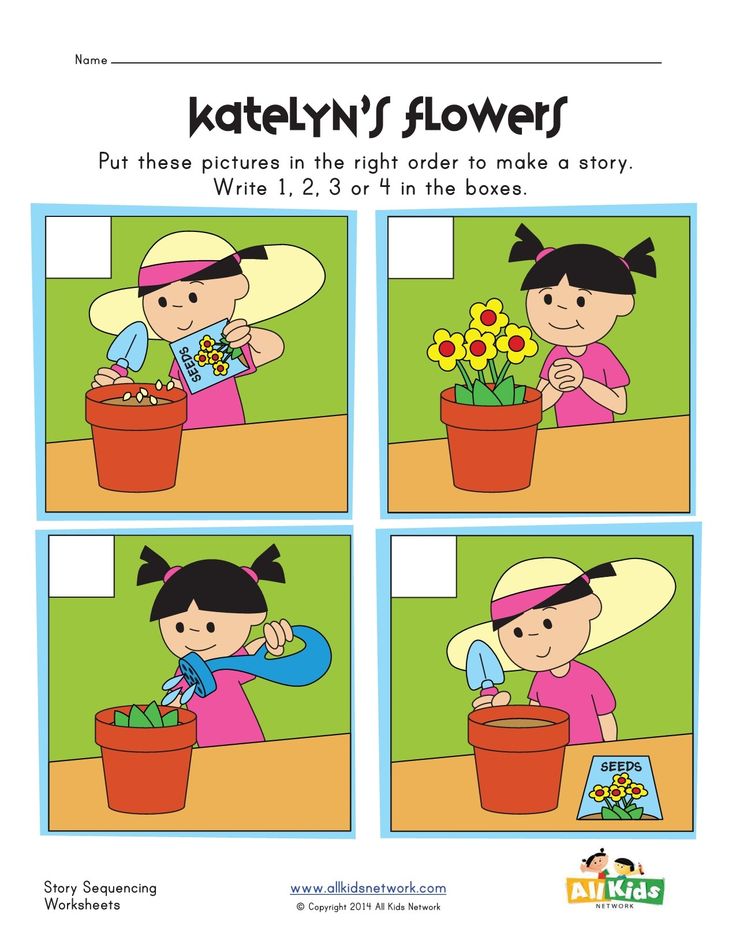

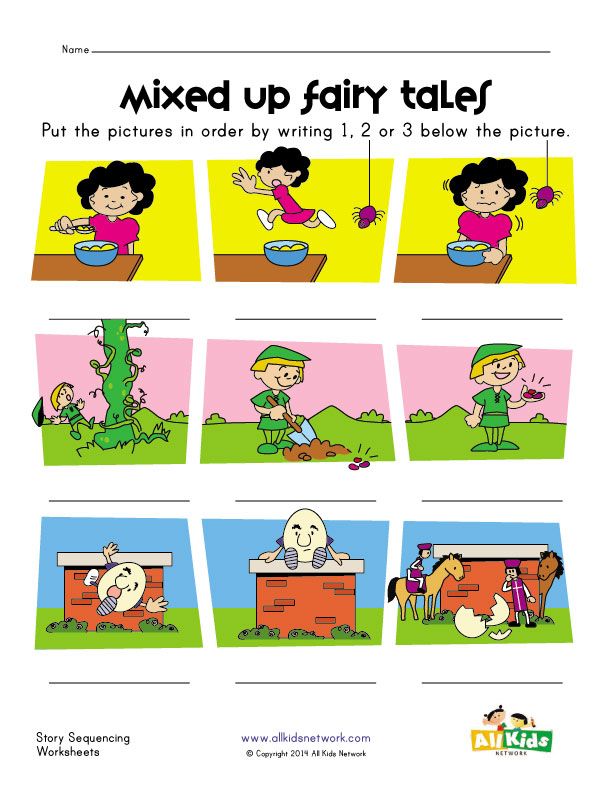

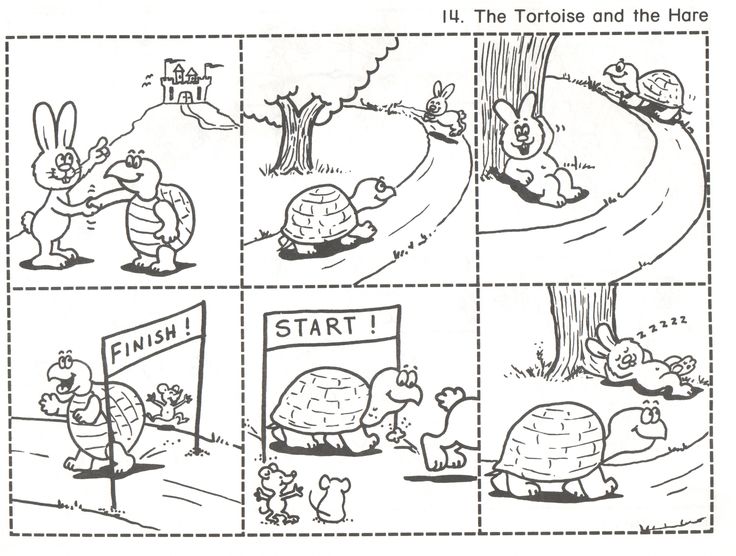

3) Kids can learn presentation skills and organizational thought when telling stories

Part of the skill of storytelling is being able to maintain audience interest. This involves at least two things:

- Being able to dramatize the story verbally through bodily actions, or tone of voice and use of descriptive language.

- Being able to organize a story with a clear beginning, middle, climax and end. Sometimes this also involves coming up with a morale to a story, which takes planning and deeper thought.

Being able to read out loud a story that a child wrote and illustrated can also result in self confidence. As adults, we know it’s hard to put ourselves out there. But when we take that risk, and then see that people loved our work, and it wasn’t so scary after all, we can get better at doing it again. Thus, kids can learn to be good presenters and articulators of information through the practice of telling stories.

As adults, we know it’s hard to put ourselves out there. But when we take that risk, and then see that people loved our work, and it wasn’t so scary after all, we can get better at doing it again. Thus, kids can learn to be good presenters and articulators of information through the practice of telling stories.

4) Telling stories helps kids with learning other subjects

You may have heard this quote in your lifetime, which rings true for all learners, not just little ones:

“Tell me and I forget. Teach me and I remember. Involve me and I learn.”

-Benjamin Franklin

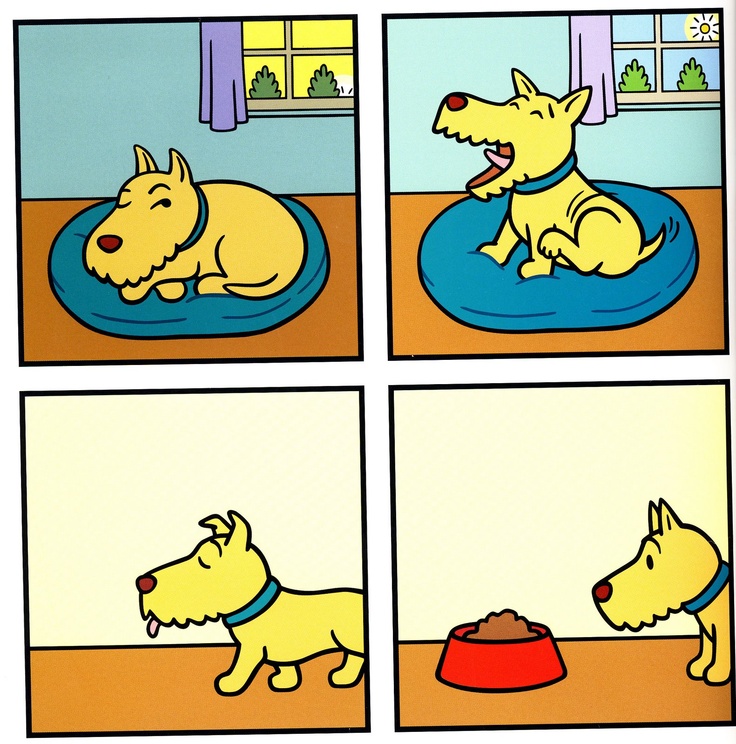

So, based on that logic, it makes a lot of sense that when you make kids the storytellers, they can learn easier. According to this essay, “the process of constructing stories in the mind, is one of the most fundamental ways of making meaning, and thus pervades all aspects of learning.”

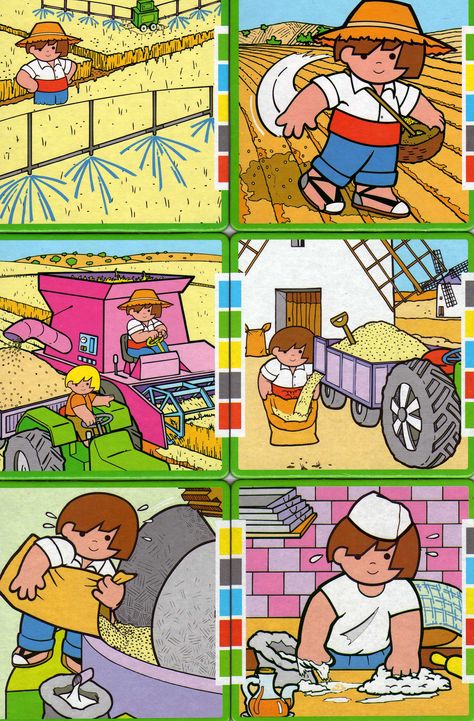

In other words, encouraging kids to tell stories helps them remember things. Let’s take vocabulary for example. It is a literacy skill that all adults will need in their life, according to the article above. So if you learn a word, that is one thing. But if you then find a way to use it in your own story, you have made it ‘yours,’ in a sense. It’s more likely you’ll remember that word in the future, especially having used that new knowledge in a real-life application or context. And in storytelling, you are, in a sense, teaching what you’ve just learned.

It is a literacy skill that all adults will need in their life, according to the article above. So if you learn a word, that is one thing. But if you then find a way to use it in your own story, you have made it ‘yours,’ in a sense. It’s more likely you’ll remember that word in the future, especially having used that new knowledge in a real-life application or context. And in storytelling, you are, in a sense, teaching what you’ve just learned.

But far beyond that, as the essay linked to above notes, you can use storytelling to help kids memorize facts about any subject. If they are learning a science lesson, telling stories about that subject can help them “internalize” it.

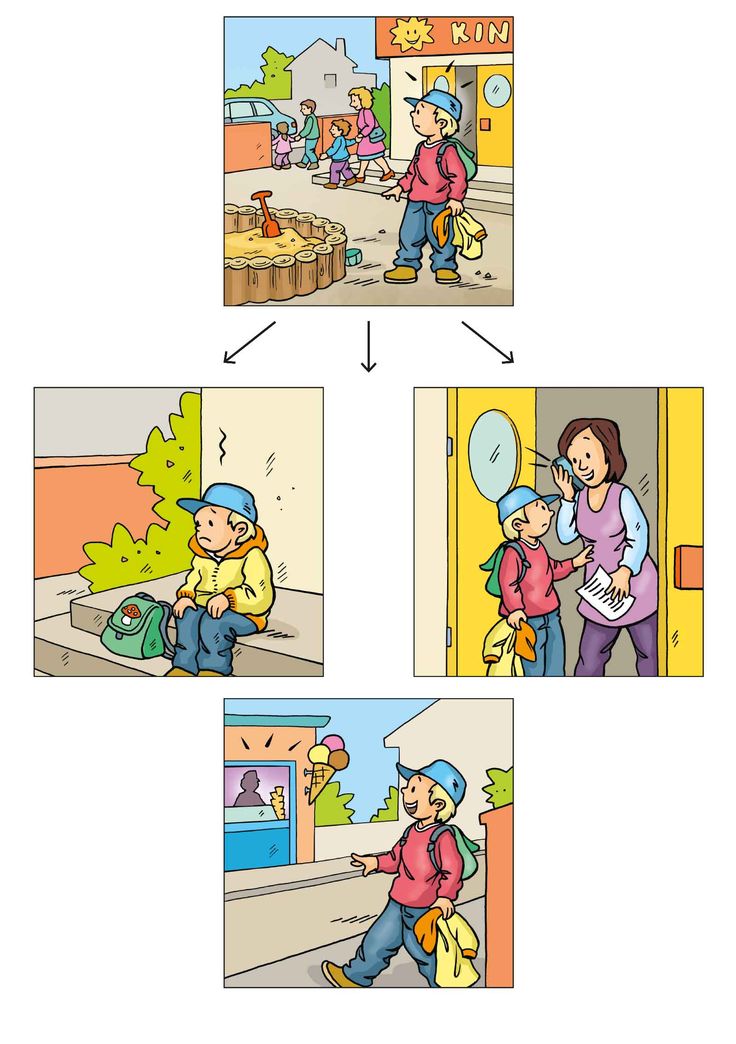

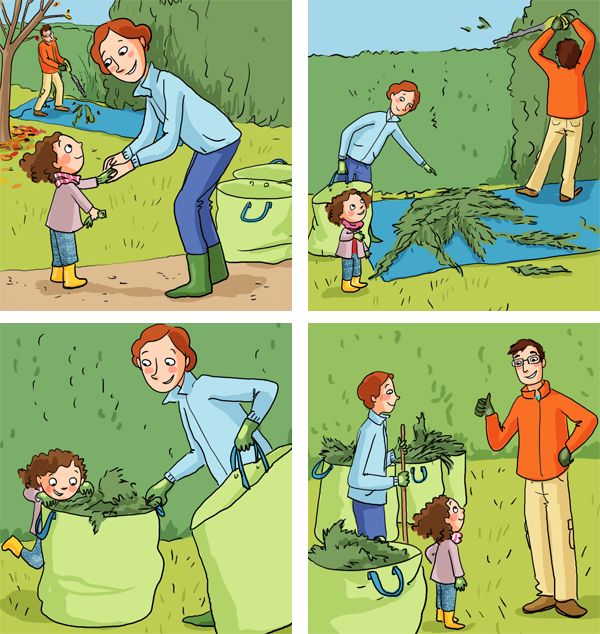

Kids telling their own stories can happen anytime of day

The great thing about storytelling with kids is that it can happen anywhere. You can encourage the benefits of kids telling their own stories while driving them somewhere, at night before bed, during bath time or even at the dinner table to spark conversation. Storytelling can be a way for you to bond with your child, and to keep them engaged with you. It can also be a great ‘downtime’ activity, if you’re tired of chasing them while playing more active games!

Storytelling can be a way for you to bond with your child, and to keep them engaged with you. It can also be a great ‘downtime’ activity, if you’re tired of chasing them while playing more active games!

See more on our blog:

- Essential props to have or make for your preschool dramatic play corner

- Why is literacy crucial in the early years? How can parents and preschools help with reading skills?

- 4 preschool journaling experiences to try in early childhood

- 5 Imagination games to play with toddlers and young kids

How to Tell Awesome Stories to Your Kids

Since our kids were little, we’ve read to them every night before bed. Sometimes after we put the book we’re currently reading aside, I’ll also give them a bonus, impromptu storytelling session as I tuck them in. I just tell them a story that I conjure up on the spot. While Gus (age 10) has kind of aged out of it, Scout (age 7) still really enjoys hearing Dad’s imaginative yarns.

I didn’t use any guides to come up with my stories, and instead just drew upon my years of consuming narratives in books, comics, TV, and movies to figure out what to say and how to (lightly) structure things.

On the recommendation of an AoM reader, however, I recently picked up a short book called How to Tell Stories to Children, co-written by two Waldorf and forest school educators. Looking to hone my paternal storytelling skills, I gave it a read. I was pleasantly surprised to learn that I was already using many proven tactics on crafting stories for kids on the fly, and I garnered a few new tips too.

If you’re a dad (or cool uncle or even grandpa) looking to connect with your kiddos via storytelling, below I share the nuts and bolts of crafting stories for children that I’ve personally field-tested and found work well.

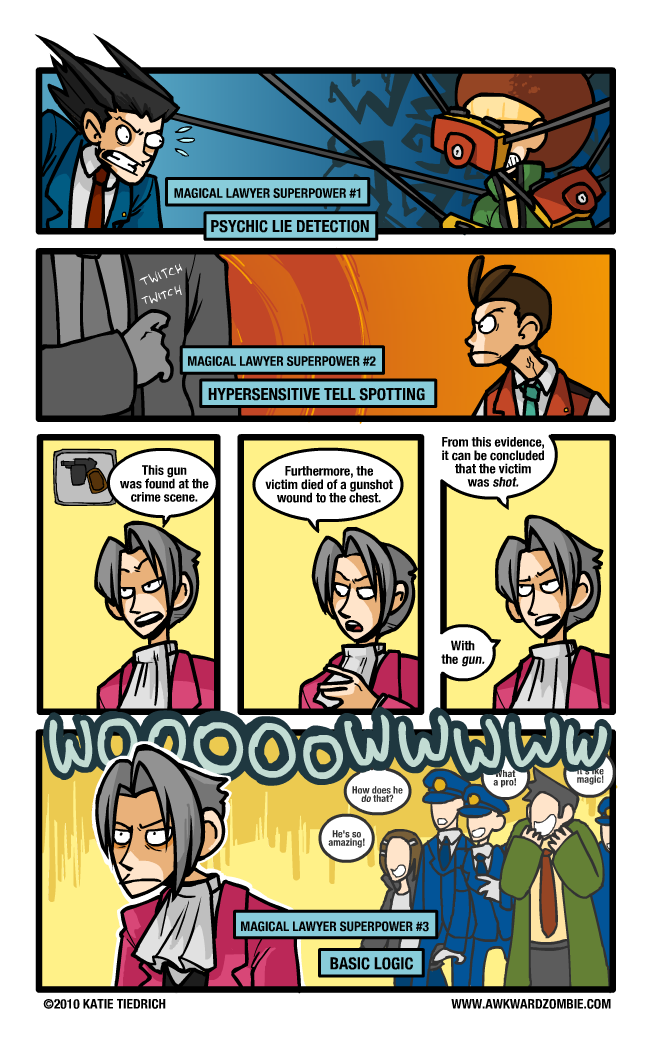

Master the Storytelling Loop to Tell Great Stories

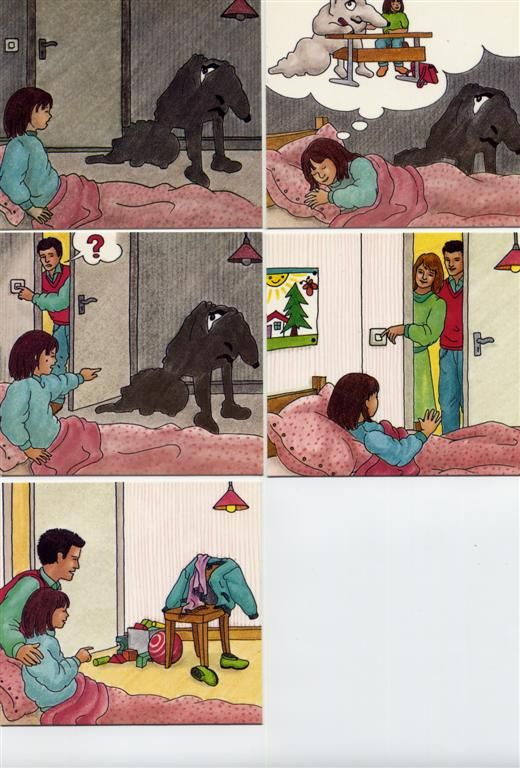

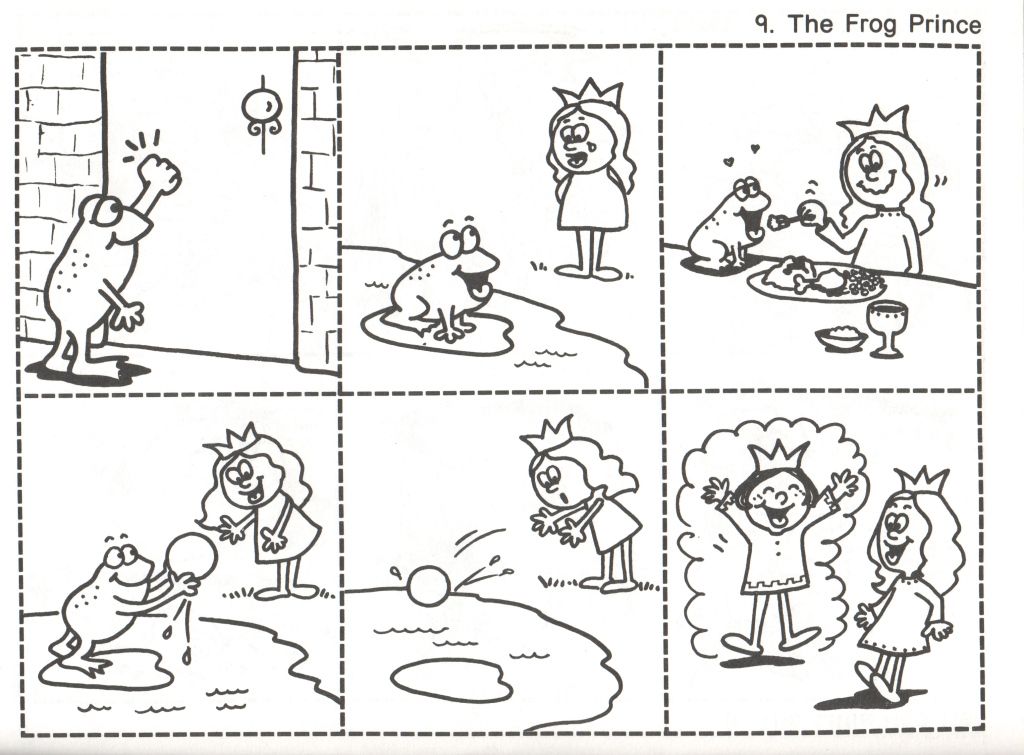

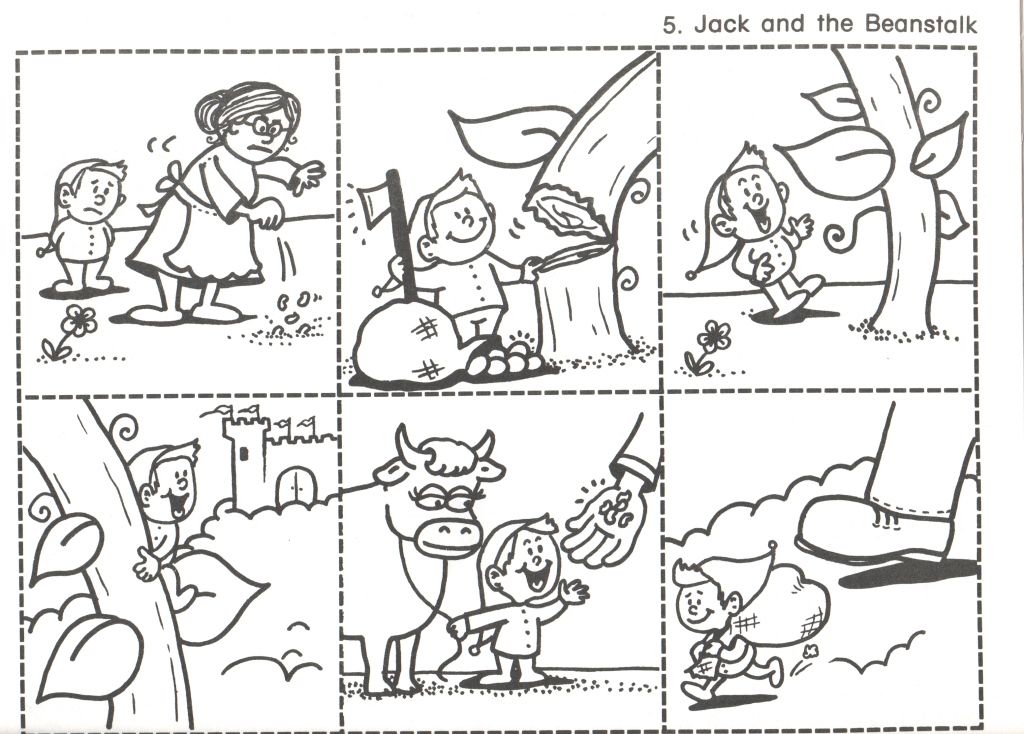

In How to Tell Stories to Children, authors Silke Rose West and Joseph Sarosy say the best stories for children are structured in the form of a loop. The story starts off in reality, in the world your kid lives in; then it moves into a world of imagination where reality and fantasy mix together to create a new world, and a conflict must be resolved; then it ends up back in reality.

The story starts off in reality, in the world your kid lives in; then it moves into a world of imagination where reality and fantasy mix together to create a new world, and a conflict must be resolved; then it ends up back in reality.

I’ve been unwittingly following this pattern since I first started telling stories to my kids.

A series of stories I’ve been telling my daughter Scout for the past few years is called “Magic Mirror Land.” I basically ripped off the story of Alice in Through the Looking Glass and The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe and made Scout the hero of the story.

She walks through the big mirror that’s in the hallway outside her bedroom door (reality). She enters a world where everything is kooky (fantasy). She’s a chicken, her brother is an elf, her parents are a dog and a cat, the sky is pink, and the sun is a lemon. In Magic Mirror Land, Scout fights all sorts of monsters to save her Magic Mirror Family. But she always makes it back to her bed before sunrise (reality). Real world→imaginative world→real world.

Real world→imaginative world→real world.

I’ve got similar stories like this. During Christmas time, I tell a story that the kids have a tunnel in the back of their closet that takes them to the North Pole. Before freezing to death, they get picked up by an elf and placed in a cozy bed in Santa’s house. They have a great time with Mr. and Mrs. Claus sipping hot chocolate, eating cookies, and playing with toys. At the end of the story, they get brought back to their home via sleigh. Real world→imaginative world→real world.

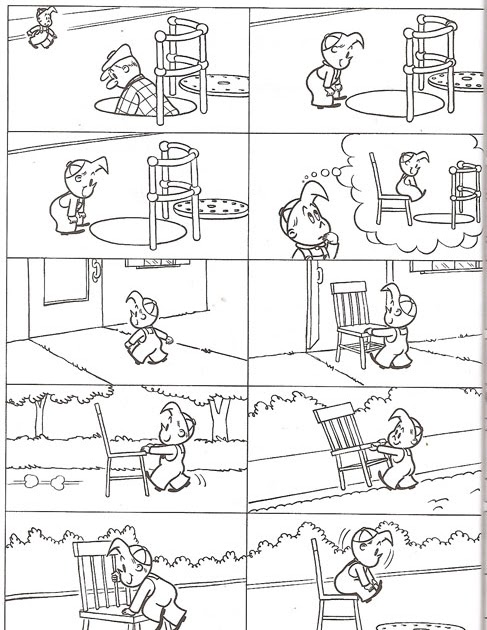

The set-up doesn’t even have to be that whimsical. If you saw a squirrel in your backyard earlier, you can make up a story about what its day is like and the problems it has to solve — avoiding fights with birds, not getting run over by a car, collecting enough nuts for winter, etc. Then the story ends with the squirrel coming back to sleep in the tree in your yard. Real world→imaginative world→real world.

Use a Portal to Connect Reality to the World of Imagination

To make the transition from the real world to the world of imagination, use portals. A few favorites that I’ve used:

A few favorites that I’ve used:

- Mirrors

- Tunnels

- Caves

- Whirlpools

- Closets

- Forests

- Wishing wells

Some of those portals are more fantastical, but by my lights the most compelling kinds are objects/structures in your kids’ current environment. Think of the types of nooks, rooms, holes, and shafts that piqued your curiosity when you were a kid, and made you wonder what they held and where they led. West and Sarosy give an example of a story where a metal drainage pipe on the side of the road turns into a passageway to a world of adventure.

Stir Up Some Conflict

Once you’re in imagination land, create a conflict that has to be resolved. An evil dragon needs to be slayed; a set of characters need to be rescued; a city needs to be saved from a slime flood. The conflict can even be just getting back to reality. I’ve used that device a few times in my stories.

Make the characters struggle. I usually tell stories where the protagonist is on the verge of defeat, but figures out at the last minute how to vanquish the bad guy or solve the problem. It’s a trope I picked up from Harry Potter, but it works. If it made J.K. Rowling a billionaire, it can make me an awesome storytelling dad.

It’s a trope I picked up from Harry Potter, but it works. If it made J.K. Rowling a billionaire, it can make me an awesome storytelling dad.

Add Fun Details

Leading up to the conflict and the resolution, describe the world of imagination in a richly detailed and compellingly whimsical way. Remember, this is a make-believe world so anything can happen. The sky can be a different color, the ocean can be red jello, gravity doesn’t work, animals talk, cars can sprout wings and fly. Run wild.

This is the part that my kids like the best. They crack up over all the weird stuff I come up with and keep asking for more. When they bring up the story in conversation, they usually want to talk about all the fun details of the imaginary world Dad spun for them.

Resolve the Conflict

The main character has to resolve the conflict in the story. In Magic Mirror Land, that usually involves Scout using skills or attributes that she has in the real world; I’ve had her employing cartwheels to beat bad guys and beams of love to unfreeze her Magic Mirror Family (I think I might have subconsciously been riffing off the Care Bears on that one).

Return to Reality

Once the conflict has been resolved, get back to reality. It could be via the original magic portal or through some other means. For example, in my North Pole stories, the kids get to the North Pole via a tunnel in their closet but come back home via sleigh.

Bring the Imaginative World Into the Real World

You can mix up the storytelling loop by bringing the world of fantasy into the realm of reality. That can create some hijinks. Think Who Framed Roger Rabbit. What would happen if a cartoon character ran around in the real world? Sometimes in our Magic Mirror Stories, the characters in Magic Mirror Land come to our world, and Scout has to figure out how to disguise a talking dog and cat.

So that’s how I make up stories on the fly for my kids. Start in the world your kids know, transition to a fantasy world, come back to the real world. The more you do it, the better you’ll get at it. Don’t be afraid to goof it up. Your kids don’t care. The thing they’ll remember the most is that their dad took the time to tell them a story before they drifted off to Dreamland.

The thing they’ll remember the most is that their dad took the time to tell them a story before they drifted off to Dreamland.

Read online "How the story is told to children around the world" - Ferro Mark - RuLit

Marc Ferro

Telling stories to children around the world

Author's note

Ten years have passed since the publication of Telling a Story to Children. You have the Soviet edition in your hands. Prior to this, translations of the book were published in England and the USA, Japan and Italy, Portugal, Brazil, and the Netherlands. German and Spanish editions are being prepared.

But, of course, the publication of this book in Russian is of the greatest interest to me. It is in your country that today, as nowhere else, the stakes of history are high. You cannot build the future of a country without having a good idea of its past and without knowing anything about how other societies see their history.

I did not change anything in the text of the book, although the very course of history changes a lot in life. Only in the chapter on the USSR did I add a few pages on the problems of history during the perestroika period. A chapter on World War II has also been added; it was written very recently. In other places, everything remained the same as it was ten years ago. Moreover, I must warn the reader that if the history of Western Europe occupies a limited place in the book, then this is done deliberately. The time has come to abandon the Eurocentric understanding of history. And I aspired to it.

It remains to add that without the qualified and intelligent help of Elena Lebedeva this edition would not have seen the light of day. And I give her my thanks.

Marc Ferro

From the translator

It was difficult to translate Marc Ferro's work. “The gigantic idea of the book, which smacks of megalomania”, which the author justifies in the preface, poses many problems for the translator in mastering heterogeneous and extensive material: historical, country and film studies, and pedagogical. Absolutely invaluable in this work was the help of specialists in various fields of history, who answered my questions, gave bibliographic references, and finally took the trouble to read the texts of individual chapters in translation and express their comments. I offer my most heartfelt gratitude to M. S. Alperovich, A. S. Balezin, I. A. Belyavskaya, Yu. L. Bessmertny, O. I. Varyash, A. A. Vigasin, R. R. Vyatkina, A. Ya Gurevich, M. V. Isaeva, A. V. Korotaev, S. I. Luchitskaya, A. N. Meshcheryakov, A. S. Namazova, S. V. Obolenskaya, B. N. Flora, G. S. Chertkova .

Absolutely invaluable in this work was the help of specialists in various fields of history, who answered my questions, gave bibliographic references, and finally took the trouble to read the texts of individual chapters in translation and express their comments. I offer my most heartfelt gratitude to M. S. Alperovich, A. S. Balezin, I. A. Belyavskaya, Yu. L. Bessmertny, O. I. Varyash, A. A. Vigasin, R. R. Vyatkina, A. Ya Gurevich, M. V. Isaeva, A. V. Korotaev, S. I. Luchitskaya, A. N. Meshcheryakov, A. S. Namazova, S. V. Obolenskaya, B. N. Flora, G. S. Chertkova .

The reader of this book will also face many problems. A kaleidoscope of dates, names, titles, historical events, scholarly writings and textbooks for children, films and comics - which is not here. And not everything is easily perceived without the help of comments. However, it was absolutely impossible to comment on every name, every fact, event that may not be known to the non-specialist reader. It would be another book. Comments (they are indicated by asterisks in the text) are given only where they are necessary for an accurate perception of the author's thought, and especially in cases where it is difficult to find information in Soviet reference publications.

Comments (they are indicated by asterisks in the text) are given only where they are necessary for an accurate perception of the author's thought, and especially in cases where it is difficult to find information in Soviet reference publications.

Despite what has been said, Marc Ferro's book is intended not only for historians and educators. It is intended primarily for the general reader. The author does not confine himself to the rules of a strict scientific composition, this essay is written in a completely relaxed manner, just as its composition itself is also relaxed.

Certain constructions of the author may cause doubts, desire to argue; the text of the book stirs the mind all the time, excites the thought. It makes you think, and not only about the meaning of the science of history, about how science relates to history, "released" to everyone. You also think about its role in shaping relationships between people, groups of people, between peoples. And many thoughts of the author of this book turn out to be interesting for us, first of all for us. That is why, despite all the difficulties, working on the translation was a pleasure. I hope that readers will share it with me.

That is why, despite all the difficulties, working on the translation was a pleasure. I hope that readers will share it with me.

E. Lebedeva

Foreword

Dedicated to Vonnie

Don't deceive yourself: the image of other peoples or our own image that lives in our soul depends on how we were taught history in childhood. It is imprinted for life. For each of us, this is the discovery of the world, the discovery of its past, and both fleeting reflections and stable concepts of something are subsequently superimposed on the ideas that have developed in childhood. However, what satisfied our first curiosity, awakened our first emotions, remains indelible.

We must be able to discern, to distinguish this indelible, whether it is about us or about others - about Trinidad, as well as about Moscow or Yokohama. It will be a journey through space, but, of course, through time as well. Its peculiarity is the refraction of the past in unsteady images. This past is not only not common to all, but in the memory of everyone it is transformed over time; our ideas change as knowledge and ideologies are transformed, as the functions of history change in this or that society.

It has become extremely important today to compare all these ideas, because with the expansion of the world's borders, with the desire for its economic unification while maintaining political isolation, the past of various societies becomes more than ever one of the stakes in the clashes of states, nations, cultures and ethnic groups. Knowing the past, it is easier to master the present, to give legal grounds to power and claims. After all, it is the ruling structures - the state, the church, political parties and groups connected by private interests - that own the media and book publishing, finance them from the production of school textbooks or comics to cinema or television. The past, which they release to everyone and everyone, becomes more and more uniform. Hence the deaf protest on the part of those whose history is "banned".

However, what nation, what group of people can still recreate their own history? Even among the ancient peoples who had associations and states in ancient times (like the Volga Khazars or the kingdom of Arelat), their group identity is dissolved in the nameless past. In the East, from Prague to Ulaanbaatar, all ethnic and national conflicts until recently were explained according to the same model, supposedly belonging to Marx, but in a Moscow interpretation. And all the societies of the South are decolonizing their history, and often by the same means used by the colonizers, i.e. construct a story opposite to that which was imposed on them before.

In the East, from Prague to Ulaanbaatar, all ethnic and national conflicts until recently were explained according to the same model, supposedly belonging to Marx, but in a Moscow interpretation. And all the societies of the South are decolonizing their history, and often by the same means used by the colonizers, i.e. construct a story opposite to that which was imposed on them before.

Today, every or almost every nation has several stories that overlap and juxtapose one another. In Poland, for example, the history that was recently taught at school differs markedly from that which was told at home. The Russians did not play exactly the same role in these stories ... We find here a clash of collective memory with official historiography, and in it, probably, the problems of historical science are manifested much more clearly than in the works of historians.

History, as it is told to children, and adults as well, allows one to simultaneously learn what society thinks of itself and how its position changes over time. You just need not be limited to studying school textbooks, comics, but try to compare them with the postulates of modern science. For example, the history of the Armenian people, the one taught in Soviet Armenia, the one taught by the children of the Diaspora (and many children in Armenia, but at home, in the home circle), and the one that is the generally accepted interpretation of world history, are three different versions of history. . Moreover, it cannot be argued that the latter is more realistic or more legitimate than others.

You just need not be limited to studying school textbooks, comics, but try to compare them with the postulates of modern science. For example, the history of the Armenian people, the one taught in Soviet Armenia, the one taught by the children of the Diaspora (and many children in Armenia, but at home, in the home circle), and the one that is the generally accepted interpretation of world history, are three different versions of history. . Moreover, it cannot be argued that the latter is more realistic or more legitimate than others.

Indeed, history, regardless of its attraction to scientific knowledge, has two functions: healing and struggle. These missions were carried out in different ways at different times, but their meaning remains unchanged. Whether Jesus Christ is praised in Francoist Spain, the nation and state in the Republican era in France, the Communist Party in the USSR or in China, history remains missionary in the same way: scientism and methodology serve as little more than an ideological fig leaf. Benedetto Croce wrote at the beginning of the 20th century that history poses more the problems of its time than of the era it is supposed to study. Thus, the films "Alexander Nevsky" by Eisenstein and "Andrey Rublev" by Tarkovsky, resurrecting the Russian Middle Ages, inform us one about Stalin's Russia and its fears associated with Germany, the other about the USSR of the Brezhnev era, its desire to gain freedom and its problems in relations with China. The history that is taught today to little Africans speaks about the modern problems of the black continent no less than about its past. Children's books are intended there to glorify the great African empires of the past, the splendor of which is compared with the decline and backwardness of feudal Europe in the same era. This is definitely the function of healing. Or in the same place - and this is also very relevant - the tangle of controversial issues generated by the conflict with Islam is hushed up, they are downplayed, or even with the help of the subjunctive mood their legitimacy is called into question.

Benedetto Croce wrote at the beginning of the 20th century that history poses more the problems of its time than of the era it is supposed to study. Thus, the films "Alexander Nevsky" by Eisenstein and "Andrey Rublev" by Tarkovsky, resurrecting the Russian Middle Ages, inform us one about Stalin's Russia and its fears associated with Germany, the other about the USSR of the Brezhnev era, its desire to gain freedom and its problems in relations with China. The history that is taught today to little Africans speaks about the modern problems of the black continent no less than about its past. Children's books are intended there to glorify the great African empires of the past, the splendor of which is compared with the decline and backwardness of feudal Europe in the same era. This is definitely the function of healing. Or in the same place - and this is also very relevant - the tangle of controversial issues generated by the conflict with Islam is hushed up, they are downplayed, or even with the help of the subjunctive mood their legitimacy is called into question.

Sevastopol children tell about the history of their kind

Eighth grader Anzhela Samofalova became a participant in the project of the National Association for the Development of Education "Book of Friendship". The girl writes on the pages of her notebook about the fate of her forefathers, who lived in Sevastopol at different historical milestones. Angela wants to add to her work the genealogical tree of her family, starting from the 30s of the 19th century.

The ancestor, the oldest representative of the family known to Angela's family, was a merchant Danila Samofalov, living in Sevastopol during the reign of Nicholas I. place of residence.

From which province Danila arrived in Sevastopol is not known for certain, but his affairs went smoothly, and he firmly settled in the city. Danila's son, Alexei, continued his father's work, the wealth of the merchant family only increased over the years. The surname Samofalova, according to the schoolgirl, is mentioned among the townspeople who met Emperor Alexander III, as well as among those invited to the ball on the occasion of the arrival of the reigning person in Sevastopol.

The surname Samofalova, according to the schoolgirl, is mentioned among the townspeople who met Emperor Alexander III, as well as among those invited to the ball on the occasion of the arrival of the reigning person in Sevastopol.

Relatives of the Sevastopol schoolgirl cherish the bright memories of the forefathers, and old yellowed photos of witnesses of those distant events have also been preserved. In 1905, they saw an armed uprising of sailors of the Black Sea Fleet and soldiers of the Sevastopol garrison, led by Lieutenant Schmidt, and in 1911, the Samofalovs met the last Russian Emperor Nicholas II in Sevastopol. However, perhaps the most striking and tragic moments in the biography of several generations are associated with the Great Patriotic War.

“When the Germans found out that all the sons in the family were commanders of the Red Army, they came to the house, tortured the grandmother and broke both her arms, and then decided to hang her. The rope was attached to an iron hook in the fence above the doghouse. The kennel saved the grandmother, her feet touched the roof. Leaning on a doghouse, with a noose around her neck, she stood for several hours, ”Angela told a monstrous story that her whole family knows and remembers by heart to the smallest detail.

The kennel saved the grandmother, her feet touched the roof. Leaning on a doghouse, with a noose around her neck, she stood for several hours, ”Angela told a monstrous story that her whole family knows and remembers by heart to the smallest detail.

However, the most honorable place in the large family of a schoolgirl is occupied by Angela's great-great-grandfather - Hero of the Soviet Union Andrey Efimovich Chertsov . The commander of the torpedo boats of the Black Sea Fleet, senior lieutenant Chertsov participated in the battles for the defense of Odessa, Sevastopol, Kerch, and the Caucasus. In the distant 43rd, under heavy enemy fire, he struck a boom-net barrier, providing passage to the Novorossiysk port of ships with paratroopers. During the liberation of Sevastopol, he sank three German self-propelled barges. Andrey Efimovich is also the author of the books "In the fire of torpedo attacks", "Azov flotilla in the battles for the Motherland" and the story "The feat of the cabin boy". A bust of the Hero was erected in Sevastopol and a street was named after him.

A bust of the Hero was erected in Sevastopol and a street was named after him.

“It's an amazing feeling to go through old yellowed photographs of your grandparents and great-grandfathers and suddenly feel that these are not just photographs, but a story. Moreover, the story, which may be of interest not only to family members. The biography of the Angela family is very informative - the time was turbulent and harsh then, through the fate of these people we see different historical milestones: first Sevastopol during the reign of Russian autocrats, then Sevastopol - rebellious, Sevastopol and the townspeople during the Great Patriotic War ...

It's great that the Friendship Notebook project encourages teenagers to remember their roots. And it is very important to remember and honor your ancestors, and, most importantly, to pass on the history of the family from generation to generation” , - says Olga Dronova, chairman of the public organization “Our Sevastopol” .

Organization "Our Sevastopol" promotes the project of the National Association for the Development of Education "Notebook of Friendship" in the Crimea and Sevastopol.

Angela's creative work will be presented in one of the Friendship Notebook nominations. The history of the Angela family and the Samofalov family deserves the closest attention and is worthy of being told about it in the framework of the competitive nomination. We hope that under the strict guidance of the class teacher Lyudmila Evgenievna Tyutyunnikova, Angela's work will be interestingly framed. We will immediately send it to Perm, where a competitive selection will take place " , - said the regional coordinator of the project Margarita Kuvshinova.

According to the coordinator, about two hundred schoolchildren from Sevastopol joined the project "Book of Friendship". More recently, schools from Simferopol and Yalta have joined the Friendship Notebook.