Learning about sentences

How to Teach Sentence Writing & Structure

Teaching Tips

October 22, 2020

0

8 mins

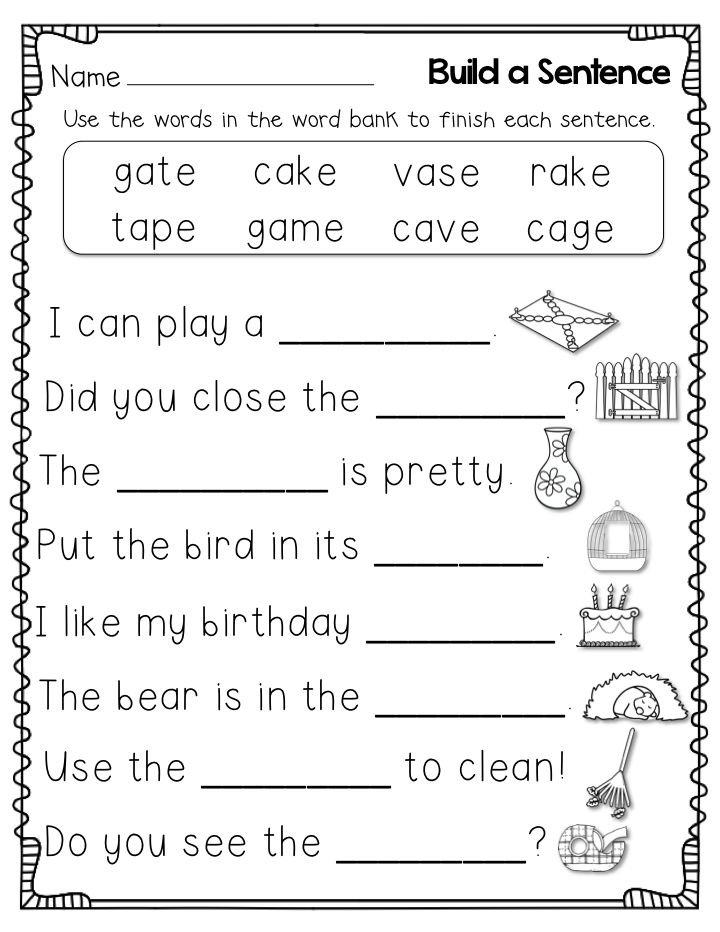

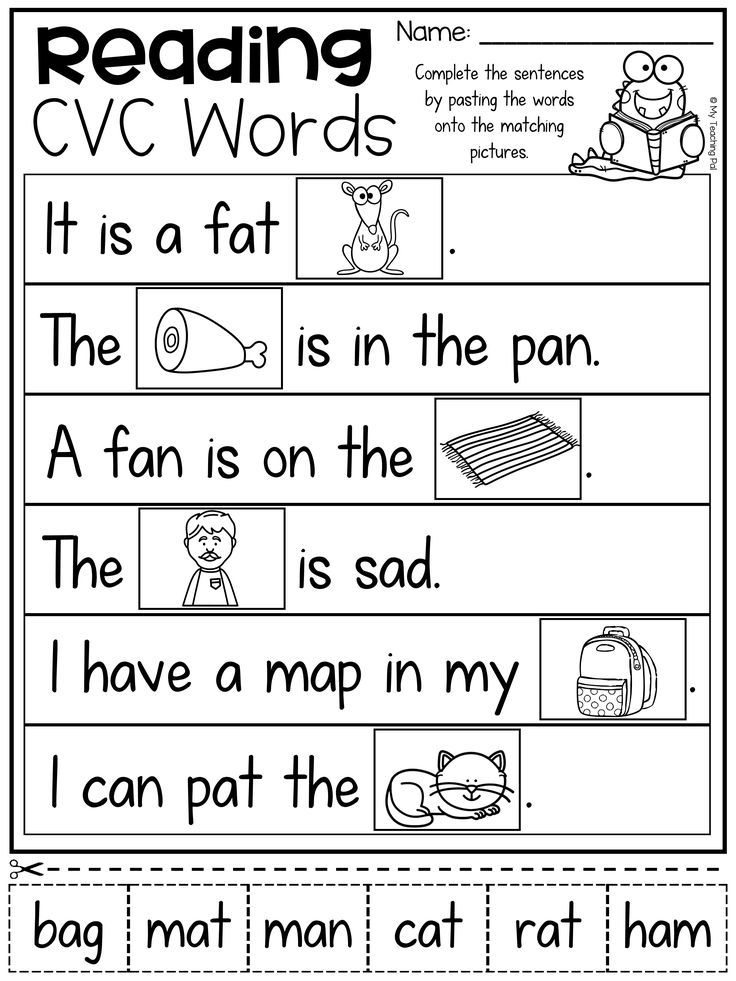

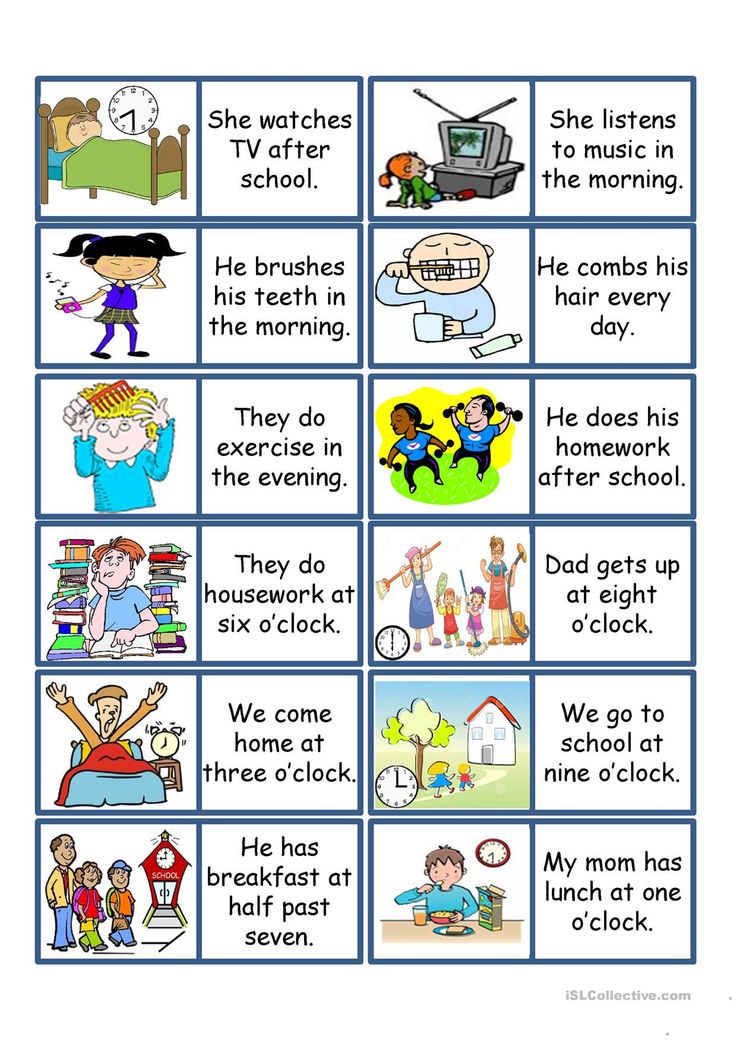

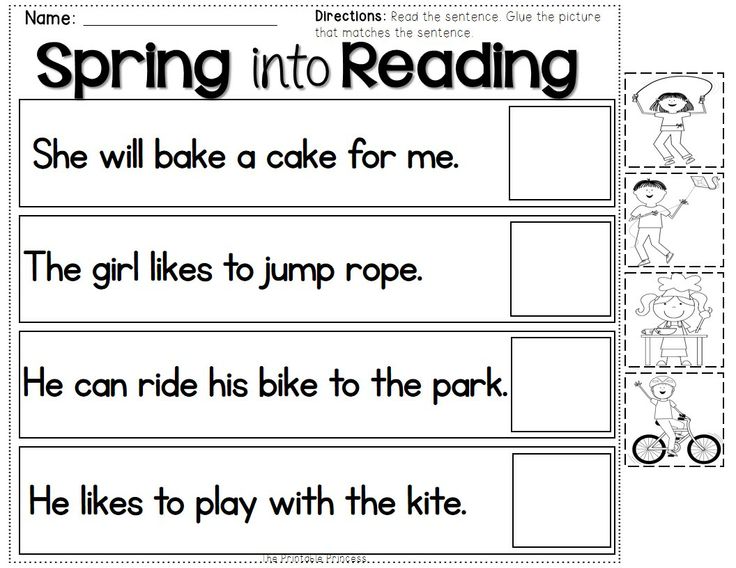

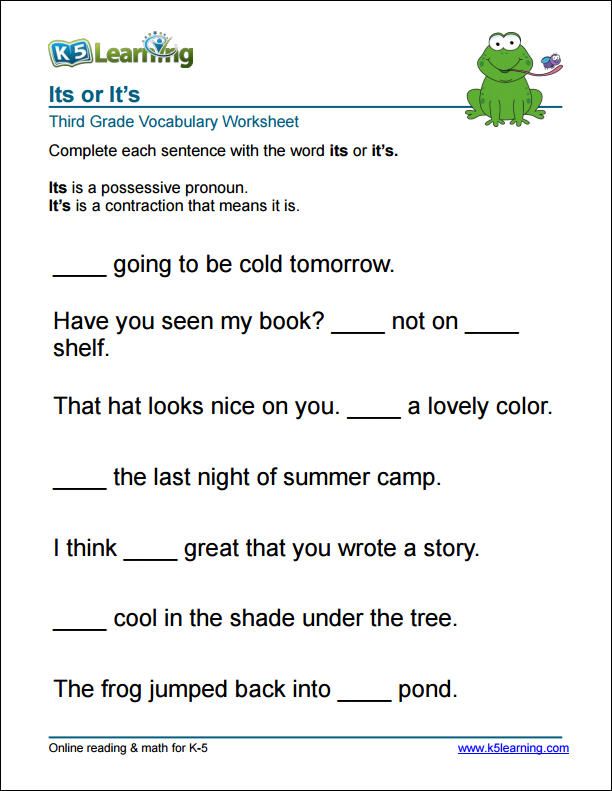

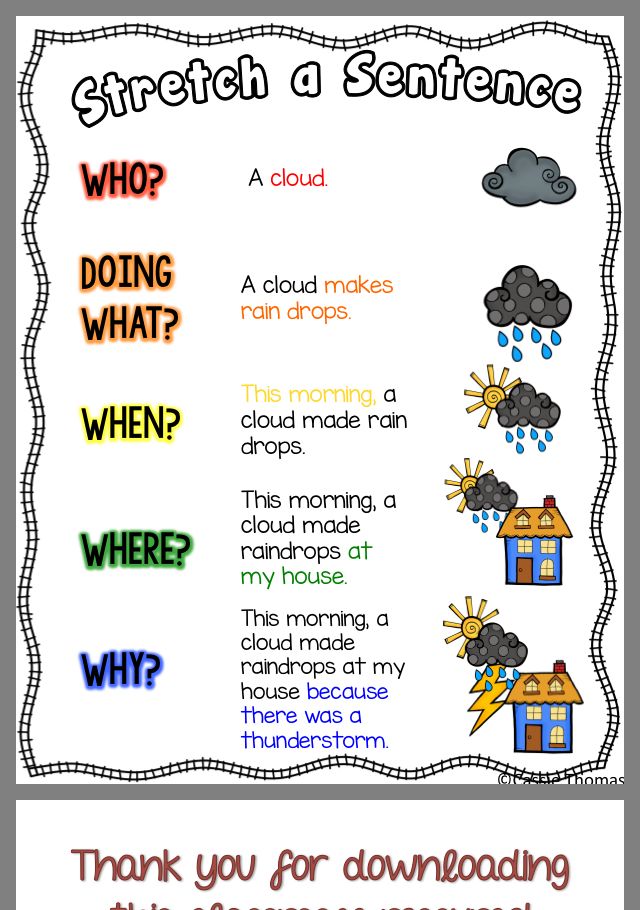

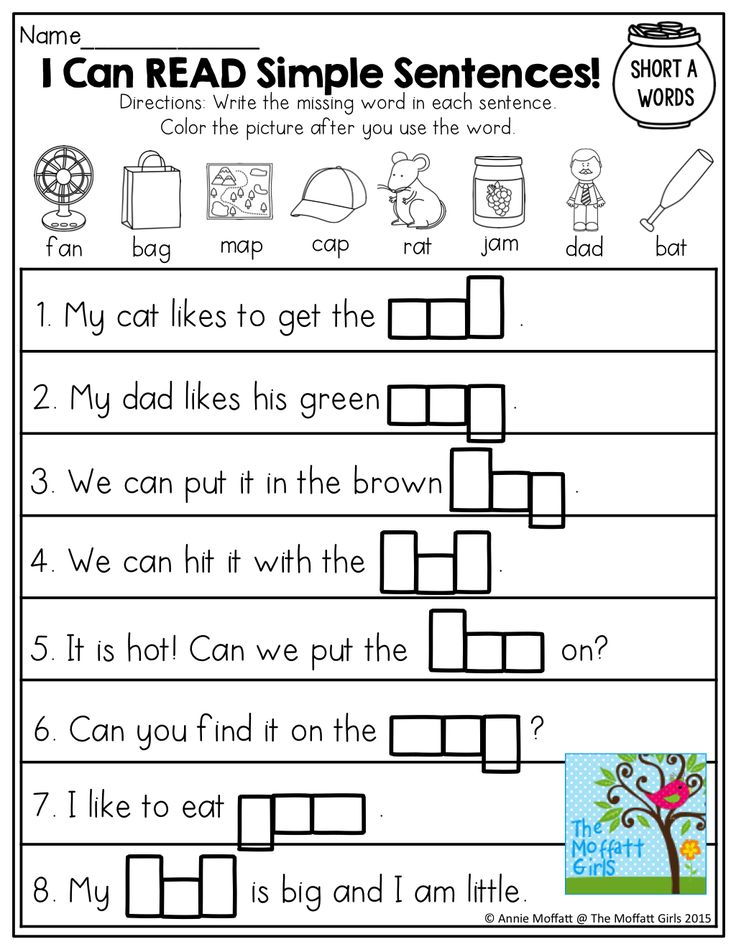

So, your student can write letters and is developing early literacy skills to read high-frequency words and sound out some new words. What comes next? Sentence writing, of course!

How exciting it is when children move from being able to express their ideas only by drawing pictures to writing sentences that everyone can read! Before we can help children learn to write a sentence, we first need to teach them what a sentence is! Then we need effective teaching strategies and good materials to make teaching and learning sentences fun.

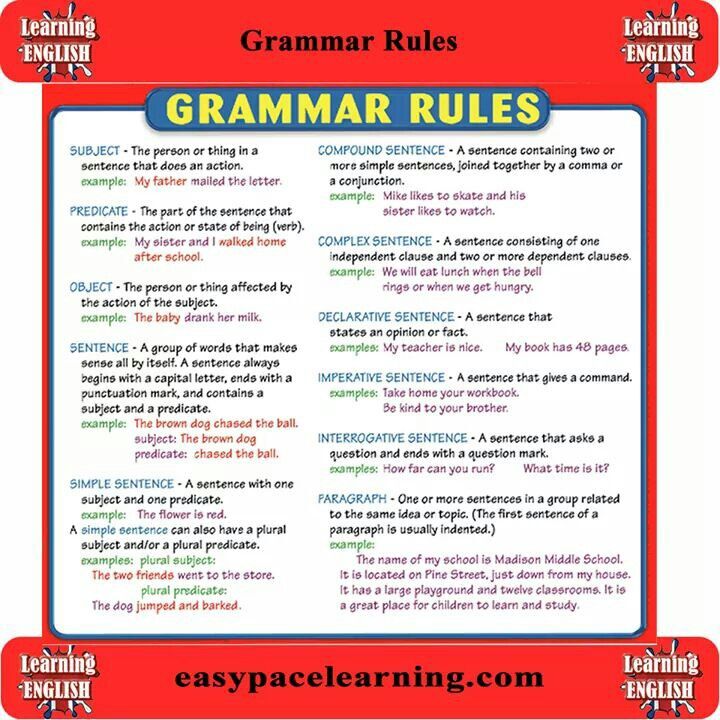

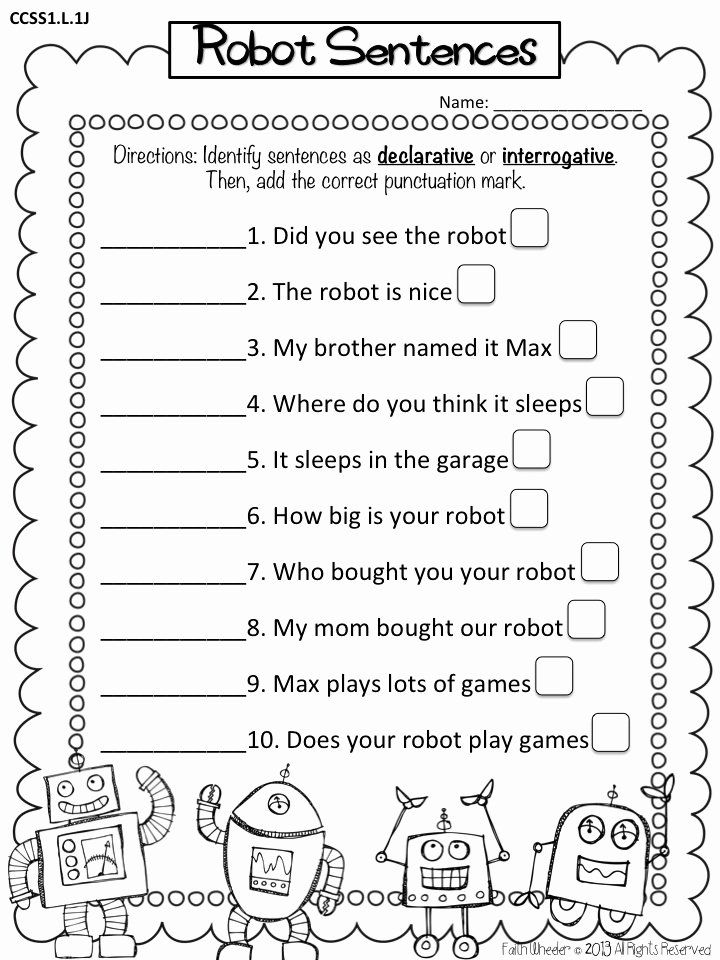

What is a Sentence?

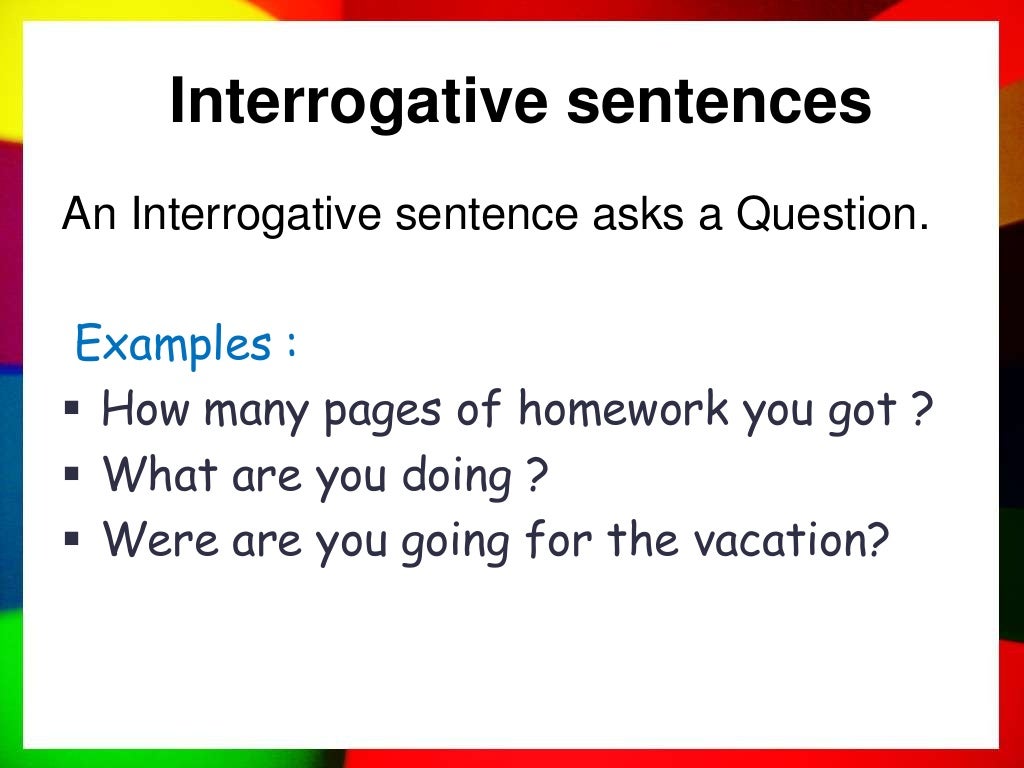

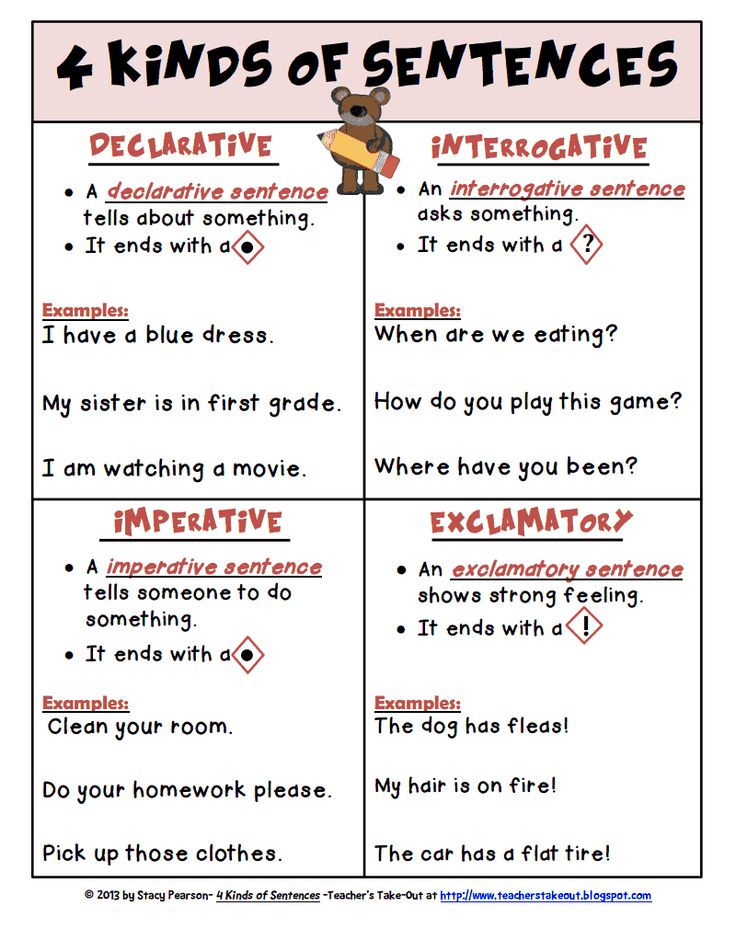

A sentence:

- is a group of words that expresses a complete thought that can stand alone (also called an independent clause)

- starts with a capital letter

- has spaces between each word

- ends with punctuation (period, question mark, or exclamation point)

- contains a subject (someone or something) and a predicate (what the someone or something is being or doing)

There are three main types of sentence structures:

- Simple Sentence: One independent clause with a subject and a predicate

- Ex: The dog wags her tail.

- Ex: The dog wags her tail.

- Compound Sentence: Two or more independent clauses joined together by a coordinating conjunction (i.e., and, but, for, or, nor, yet, so)

- Ex: I open the door, and the dog wags her tail.

- Complex Sentence: Contains at least one independent clause and one dependent clause

A dependent clause is a group of words with a subject and verb that expresses a complete thought, so it cannot stand alone (e.g., “when I get home”).- Ex: The dog wags her tail when I get home

How to Teach Sentence Structure

Want your students to have success with writing sentences? The formula is simple!

Active Teaching + Good Materials = Writing Success.

Let’s first look at Active Teaching.

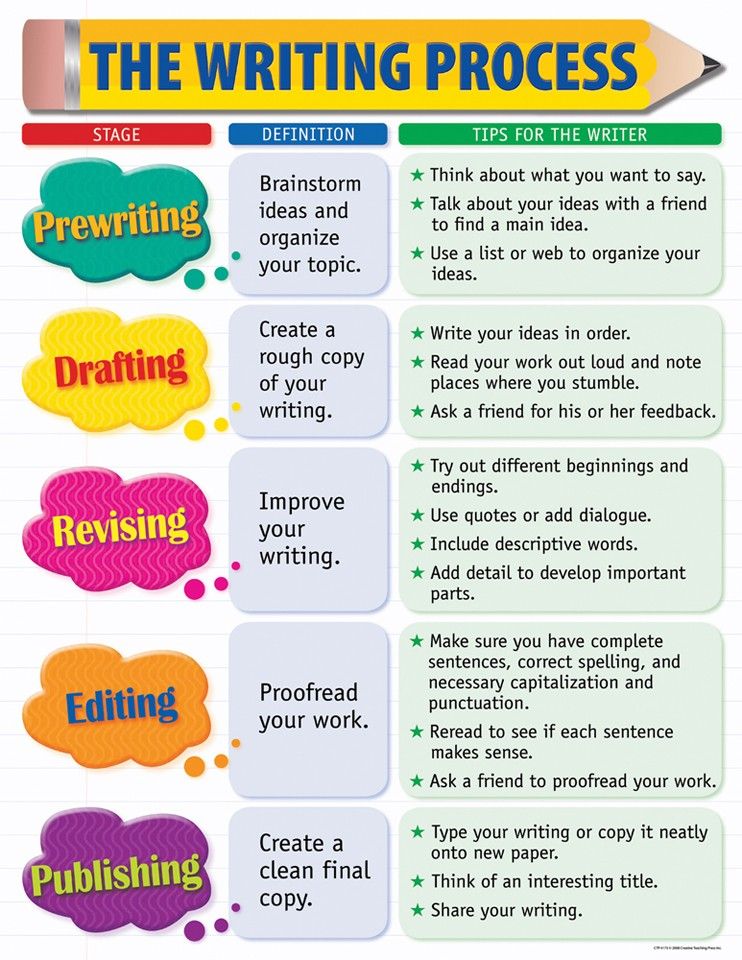

Three Instructional Stages for Teaching SuccessfullyThere is an important, three-step process that sets children up for success when learning. This process can not only be used when teaching sentence structure but also for handwriting instruction and so many other skills!

This process can not only be used when teaching sentence structure but also for handwriting instruction and so many other skills!

- The first stage is Direct Instruction. During this stage, you directly instruct by actively demonstrating how to write a sentence. To get all eyes on you as you demonstrate, say, “My Turn! Watch me write the sentence.” Explain the important concepts as you write such as capitalization, spacing, and punctuation. Then say, “Your Turn,” indicating it’s their turn to imitate you in their workbook, worksheet, or lined paper. This step assures students are watching and learning how to write correctly, which is a foundation piece for good habits.

- The next stage is Guided Practice. This requires that teachers guide students to their workbook or worksheet where they copy sentences from a model. While students write, teachers should walk around and closely monitor and guide their students. Resist the temptation to let workbook and worksheet practice be independent work as they can copy incorrectly and reinforce bad habits.

Students need direct instruction prior to and continued guidance during this stage so they practice correctly.

Students need direct instruction prior to and continued guidance during this stage so they practice correctly. - The final stage is Independent Practice. This happens when children write sentences on their own without a visual model, and it is an important part of your lesson to help students develop independence with writing sentences. Provide lined paper or journals for this stage.

Make Teaching Sentences Fun!

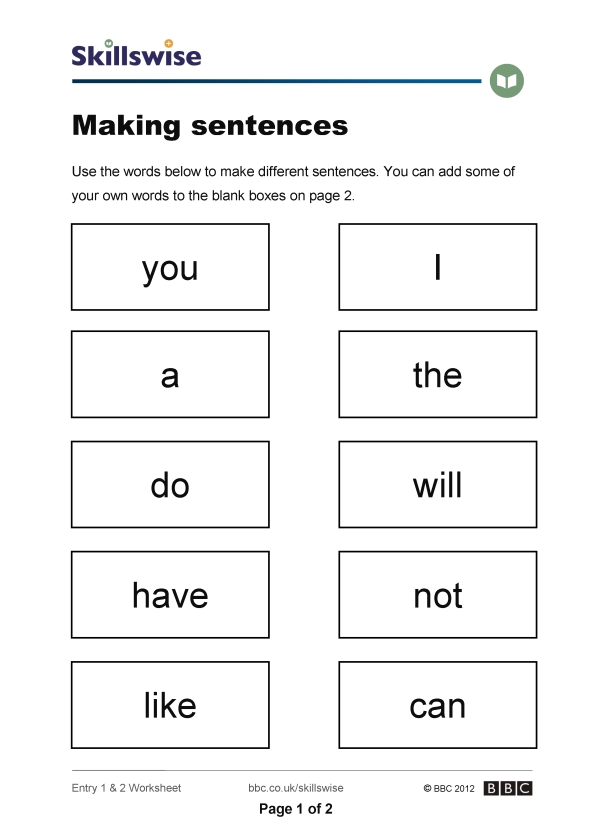

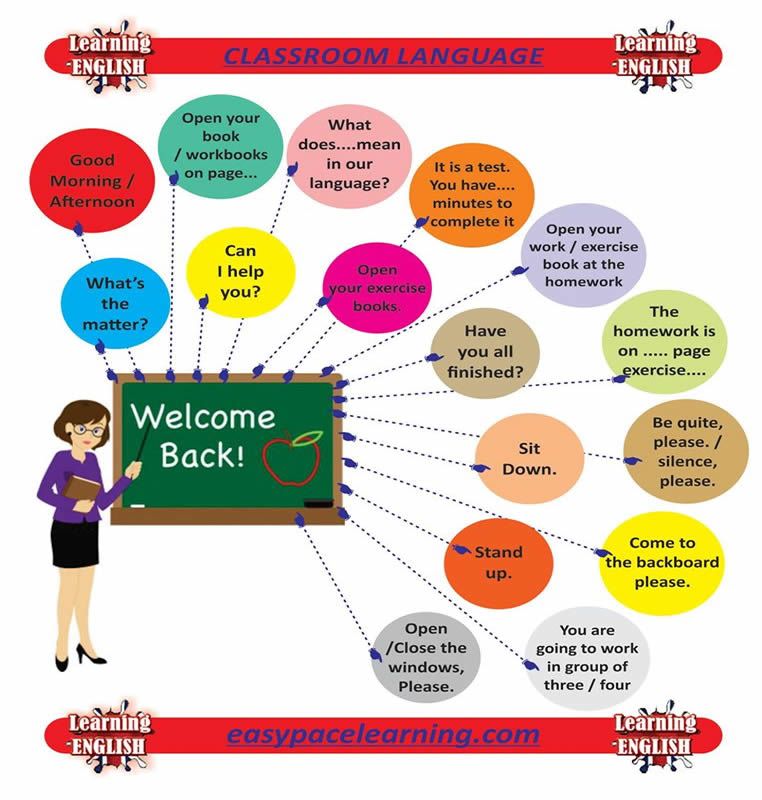

Research tells us that multisensory teaching is the best way to teach children so that we appeal to each child’s learning style. It’s also part of active teaching! Add one or more of these multisensory ideas to your sentence structure lessons to get children excited and engaged in the lesson!

Sentence School

Sentence School is a kindergarten level program offered from Learning Without Tears designed to reinforce good handwriting habits as you teach students to form sentences and become confident writers. It works alongside any language arts program and takes only 10-15 minutes per day. Daily lessons in the included teacher's guide promote vocabulary and sentence skills with word cards and common classroom objects. Each lesson plan includes an active, hands-on activity to help children learn the words and formulate sentences with what they see and experience in the activity.

It works alongside any language arts program and takes only 10-15 minutes per day. Daily lessons in the included teacher's guide promote vocabulary and sentence skills with word cards and common classroom objects. Each lesson plan includes an active, hands-on activity to help children learn the words and formulate sentences with what they see and experience in the activity.

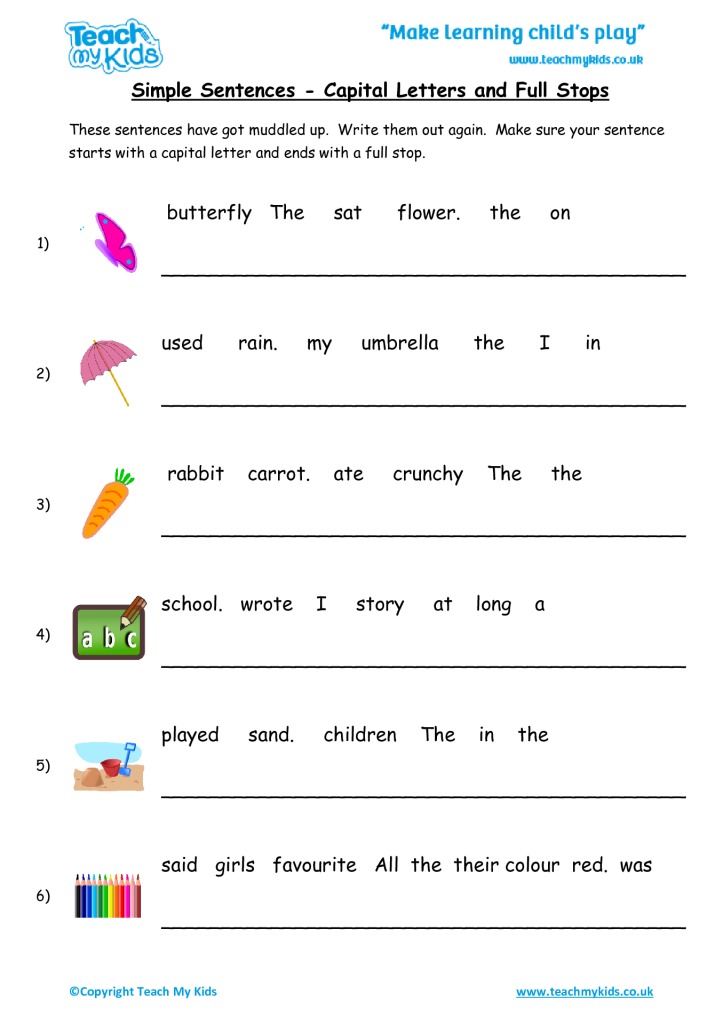

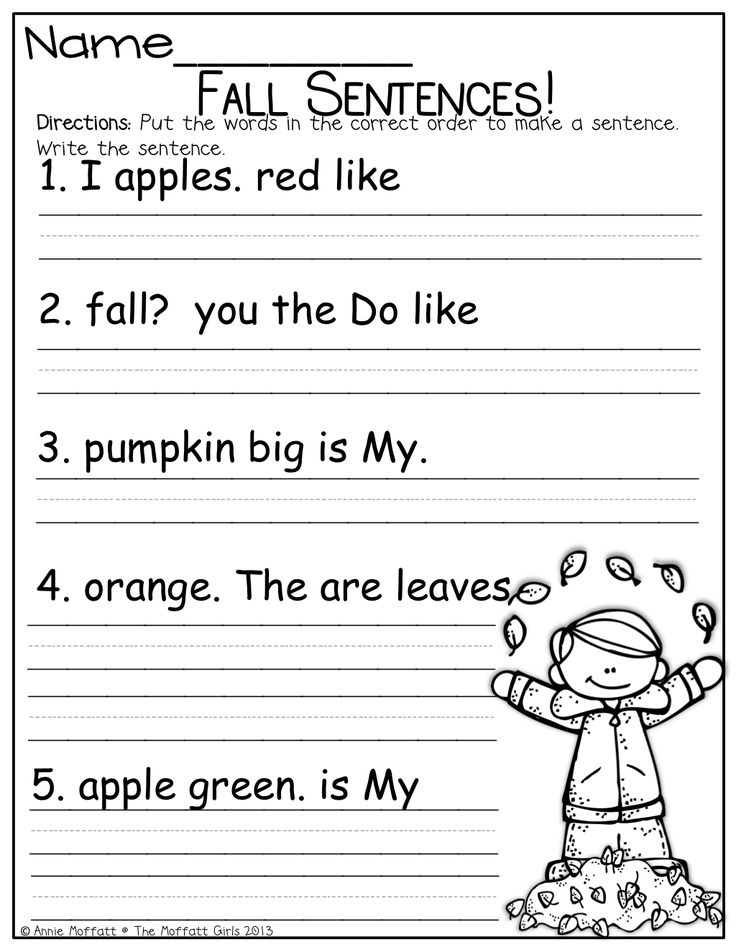

Mixed-Up Sentences

Write the subject on one popsicle stick and the predicate on another for several sentences. Talk with your students about the two parts of a sentence and then let them mix them up to make silly mixed-up sentences!

Sentence Song

The Sentence Song is on the Rock, Rap, Tap, and Learn Music album from LWT. It is sung to the tune of "Yankee Doodle" and helps children learn about capitalization, spacing between words, and punctuation in a fun way!

Spacing Strategies

One of the challenges children face when starting to write sentences is spacing! We don’t use spaces when we speak, so the concept of spacing isn’t natural for children. There are many creative ways to help children learn to space their words. Here are a few:

There are many creative ways to help children learn to space their words. Here are a few:

- Nothing Bottle: What is a space? It’s “nothing,” right? Take a large, empty plastic bottle or pitcher, and write the word “nothing” across it. Before writing time, ask students to hold out their hands and pour some “nothing” into them. Instruct them to use a little “nothing” after every word as they write!

- Sick Sentence Clinic: Write a sentence on the board or with the A+ Worksheet Maker without any spaces between the words. Discuss with students why that sentence is difficult to read and explain that it is a “sick sentence”. Tell them they are going to be “sentence doctors” and make that sentence healthy again! Give them lined paper to re-write the sentence with good spacing.

- Spaghetti and Meatballs: Explain that there should be no more than a spaghetti-sized space between letters inside words, and we need a meatball-sized space between words! Give students a large cotton ball and a piece of string to use as their “spaghetti and meatball” to measure spaces as they write.

What Else Do You Need to Help Children Write Sentences Effectively?

You need Good Materials! Teachers need good materials to demonstrate sentences and students need well-designed materials to practice on. The products below will promote success for you as a teacher and for your students as they are developing their writing skills.

For Teachers

- Worksheet Maker Lite: This free and easy-to-use resource lets you create worksheets for students using the LWT double lines. There are worksheet templates for grades K-4 in both print and cursive with grade-appropriate lines and spacing. Templates include spelling, vocabulary, sentence writing, and graphic organizers.

- Double Line Writer: To help with demonstrating sentences on your board, insert two markers in the holes of this handy tool to easily draw straight double lines on chalkboards or dry erase boards.

- Double Line Sentence Strips: These 24”x3” strips are great for modeling sentences and come in a pack of 100.

You might want to keep one on your bulletin board with a sample sentence as an example for students to reference!

You might want to keep one on your bulletin board with a sample sentence as an example for students to reference! - Double Line Chart Tablet: These 24”x32” tablets can be used with your easel to demonstrate sentences for students.

For Students

- Grade Level Handwriting Workbook: Handwriting Without Tears workbooks teach letters and numbers and include page after page of writing activities to practice sentence writing and handwriting skills.

- Building Writers: This program includes grade-level workbooks for grades K-5 for children to practice and build core writing skills. It offers a scaffolded approach to develop proficiency with writing narrative, information, and opinion pieces.

- Double Line Paper: Children need extra paper for writing practice. Double Line Notebook Paper comes in packs of 100 or 500 sheets in wide, regular, or narrow width.

- Curious about double lines and why they work? Double lines control children’s letter size, spacing, and placement, which promotes legible writing that is easily transferred to other styles of paper. Watch this video to learn more:

- Big Sheet Draw & Write Paper: These 11”x17” sheets are perfect for students to have space for drawing and writing sentences about their drawing! They come in a pack of 100 double-sided sheets.

- Writing Journal: The LWT grade-level journals provide grade-appropriate double lines for students to use during independent writing time.

- Keyboarding Without Tears: Sentence writing doesn’t just happen on paper! Now more than ever it is crucial that elementary students practice composing sentences and paragraphs in digital form.

The KWT curriculum includes fun, grade-appropriate lessons for children to develop automatic keyboarding skills.

The KWT curriculum includes fun, grade-appropriate lessons for children to develop automatic keyboarding skills.

Assessment

Don’t forget about assessment! We need a way to assess children’s writing skills and track progress. The LWT Screener of Handwriting Proficiency is a free, easy-to-administer, whole class assessment that helps educators and specialists assess critical and measurable skills that children need for success including the sentence components of capitalization, spacing, and punctuation.

Sentence Writing is Fun with Learning Without Tears!

With these teaching tips and good materials, you can help children achieve sentence writing success! Don’t forget that handwriting is a foundational skill that should be taught prior to and alongside sentence structure! For more information about the products mentioned above and more ways to support children learning handwriting skills, explore LWTears.com.

Related Tags

Teaching Tips

Teaching Tips

Making the Most of Your Funding Options

September 9, 2022

0 2 mins

Readiness, Summer, Teaching Tips, Multisensory Learning

5 Ways to Support Your Students this Summer

June 7, 2022

0 5 minutes

Readiness, Summer, Teaching Tips, Multisensory Learning

4 Guidelines to Support Students Over Long Breaks in Learning

February 14, 2022

0 5 mins

There are no comments

Sentence Structure (A Complete Guide for Students and Teachers)

This article is part of the ultimate guide to language for teachers and students. Click the buttons below to view these.

Click the buttons below to view these.

A TEACHER’S GUIDE TO SENTENCE STRUCTURE

This article aims to inform teachers and students about writing great sentences for all text types and genres. I would also recommend reading our complete guide to writing a great paragraph here. You will find great advice, teaching ideas, and resources in both articles.

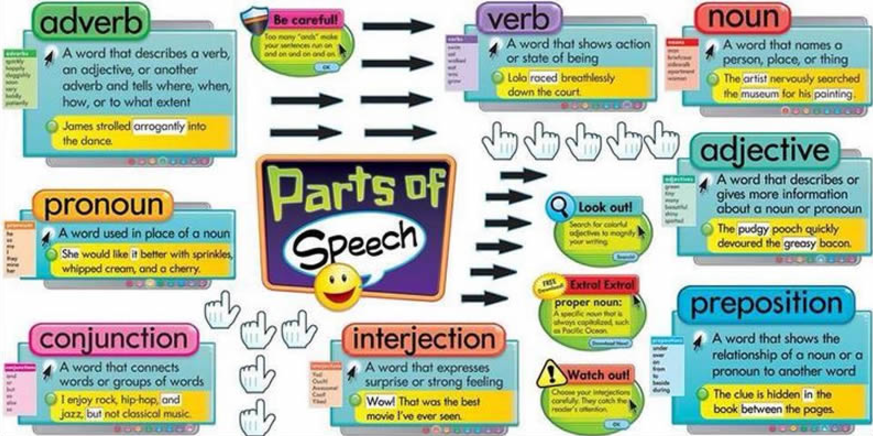

WHAT IS SENTENCE STRUCTURE?When we talk about ‘sentence structure’, we are discussing the various elements of a sentence and how these elements are organized on the page to convey the desired effect.

Writing well in terms of sentence structure requires our students to become familiar with various elements of grammar and the various types of sentences that exist in English.

In this article, we will explore these areas and discuss various ideas and activities you can use in the classroom to help your students on the road to mastering these different sentence structures. This will help to make their writing more precise and more interesting in the process.

This will help to make their writing more precise and more interesting in the process.

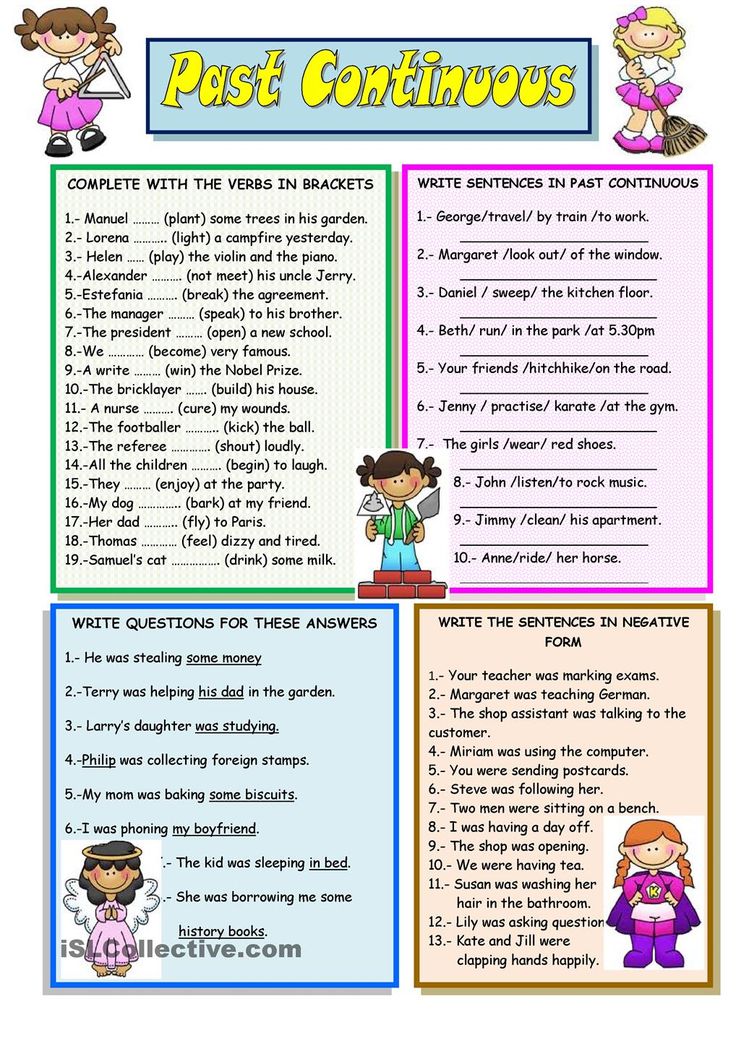

TYPES OF SENTENCE STRUCTURE

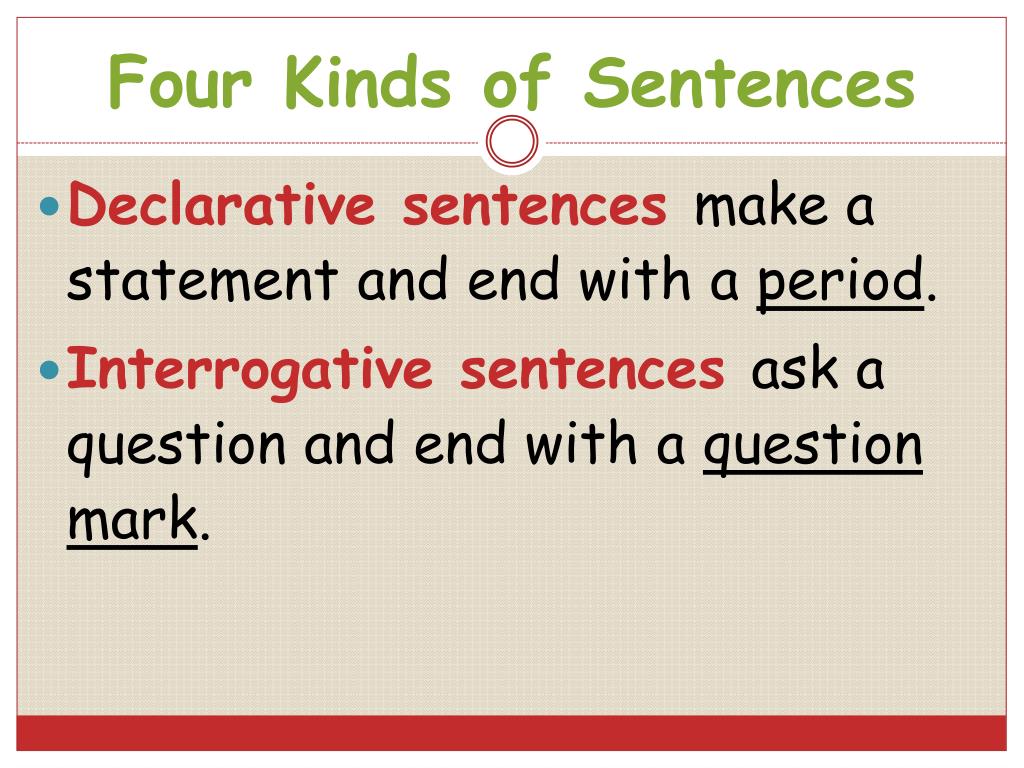

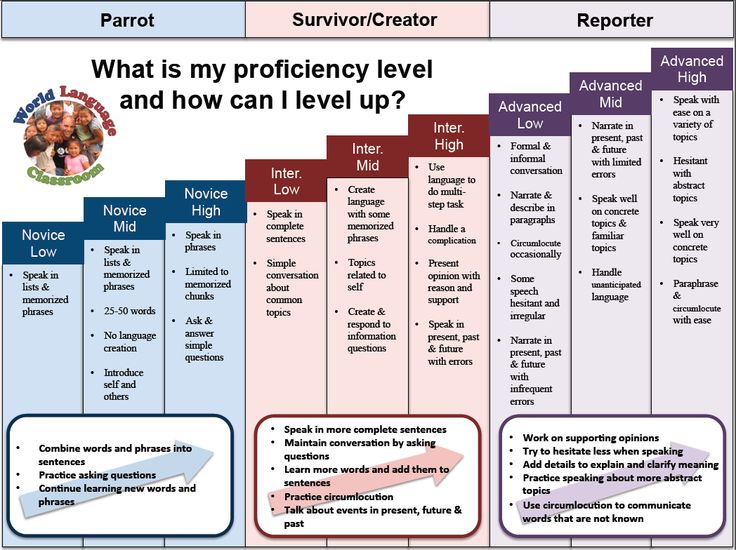

In English, there are four types of sentences that students need to get their heads around. They are:

- Simple sentences

- Compound sentences

- Complex sentences

- Compound-complex sentences

Mastering these four types of sentences will enable students to articulate themselves effectively and with personality and style.

Achieving this necessarily takes plenty of practice, but the process begins with ensuring that each student has a firm grasp on how each type of sentence structure works.

But, before we examine these different types of structures, we must ensure our students understand the difference between independent and dependent clauses. Understanding clauses and how they work will make it much easier for students to grasp the different types of sentences that follow.

A COMPLETE UNIT ON TEACHING SENTENCE STRUCTURE

This complete SENTENCE STRUCTURE UNIT is designed to take students from zero to hero over FIVE STRATEGIC LESSONS to improve SENTENCE WRITING SKILLS through PROVEN TEACHING STRATEGIES covering:

- Clauses

- Fragment or Sentence?

- Simple Sentences

- Compound Sentences

- Complex Sentences

- Compound-Complex Sentences

- FANBOYS with Run-ons

DOWNLOAD NOW

SENTENCE CLAUSES

Independent ClausesPut simply; clauses are parts of a sentence containing a verb. An independent clause can stand by itself as a complete sentence. It expresses a complete thought or idea and contains a subject and a verb – more on this shortly!

Dependent Clauses / Subordinate ClausesDependent clauses, on the other hand, are not complete sentences and cannot stand by themselves. They do not express a complete idea. To become complete, they must be attached to an independent clause. Dependent clauses are also known as subordinate clauses.

They do not express a complete idea. To become complete, they must be attached to an independent clause. Dependent clauses are also known as subordinate clauses.

An excellent way to illustrate the difference between the two is by providing an example that contains both.

For example:

Even though I am tired, I am going to work tonight.

As the non-underlined portion of the sentence doesn’t work as a sentence on its own, it is a dependent clause. The underlined portion of the sentence could operate as a sentence in its own right, and it is, therefore, an independent clause.

Now we’ve got clauses out of the way; we’re ready to take a look at each type of sentence in turn.

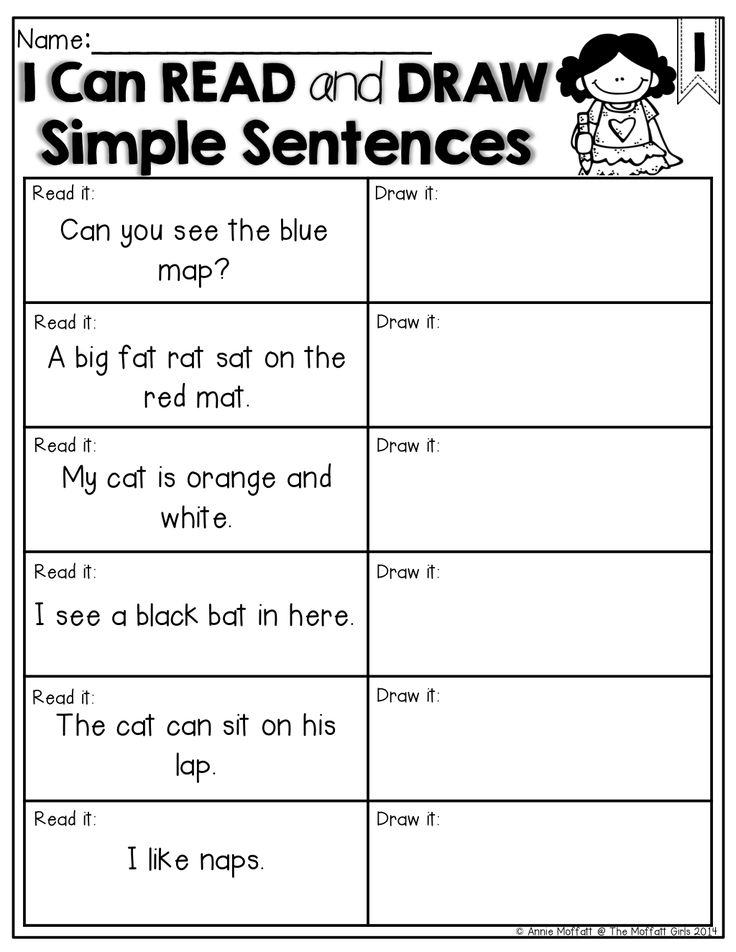

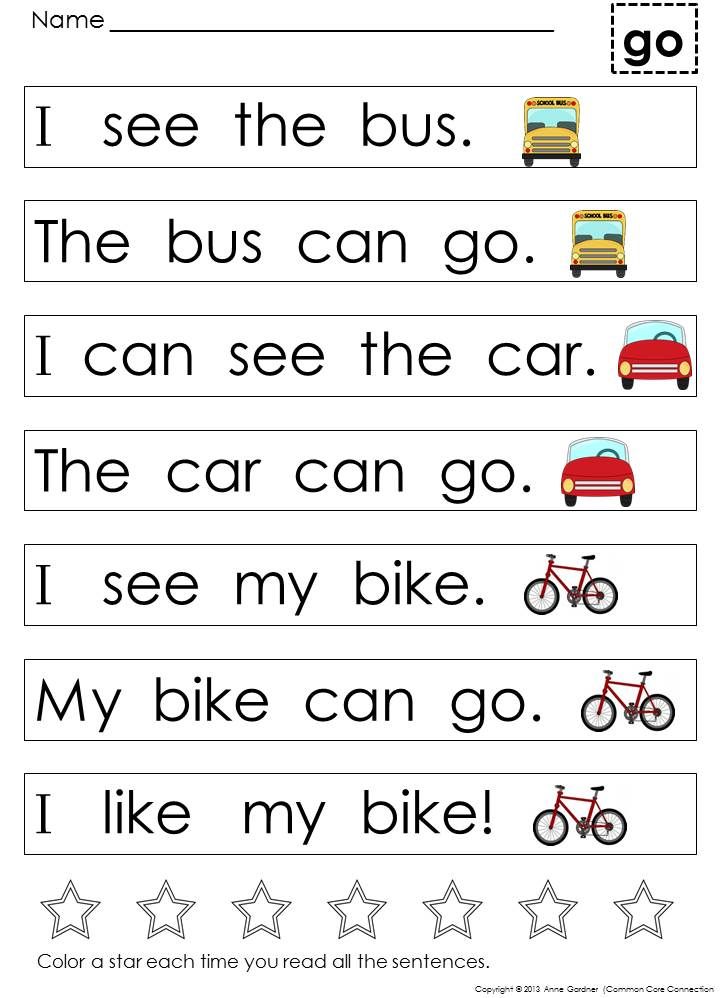

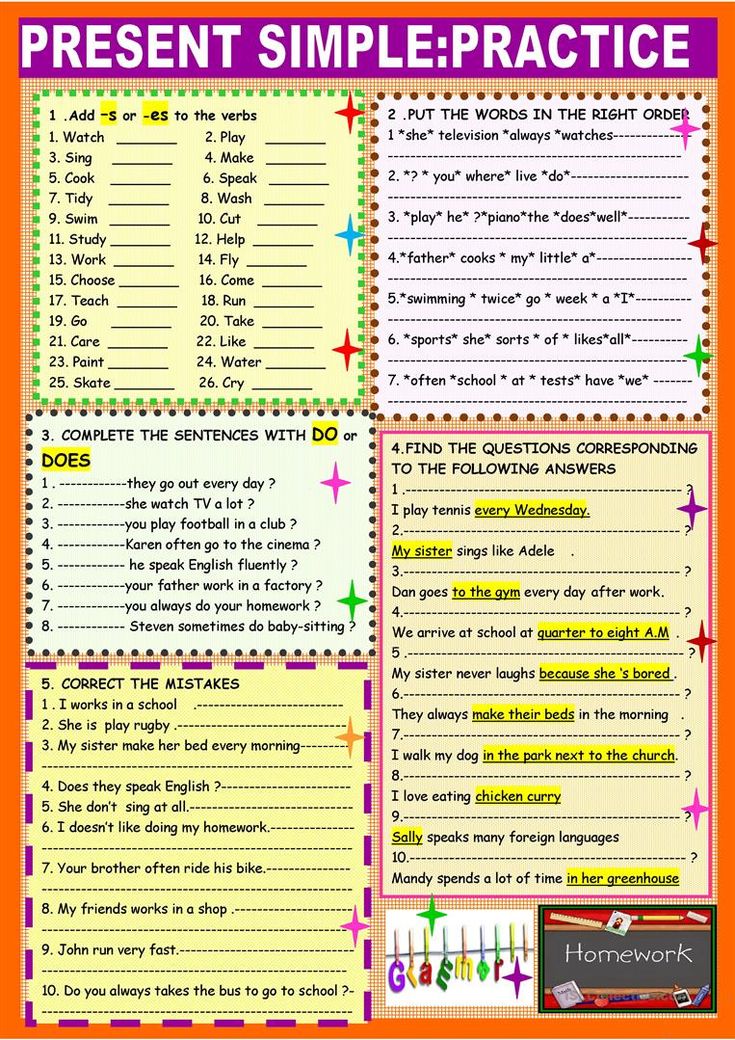

Simple SentencesSimple sentences are, unsurprisingly, the easiest type of sentence for students to grasp and construct for themselves. Often these types of sentences will be the first sentences that children write by themselves, following the well-known Subject – Verb – Object or SVO pattern.

The subject of the sentence will be the noun that begins the sentence. This may be a person, place, or thing, but, most importantly, it is the doer of the action in the sentence.

The action itself will be encapsulated by the verb, which is the action word that describes what the doer does.

The object of the sentence follows the verb and describes that which receives the action.

This is again best illustrated by an example. Take a look at the simple sentence below:

Tom ate many cookies.

In this easy example, the doer of the action is Tom, the action is ate, and the receiver of the action is the many cookies.

Therefore,

Subject = Tom

Verb = ate

Object = many cookies

After a little practice, students will become adept at recognizing SVO sentences and forming their own. It’s important to point out, too that simple sentences don’t necessarily have to be short.

For example:

This research reveals that an active lifestyle can have a great impact for the good on the life expectancy of the average person.

Despite this sentence looking more sophisticated (and longer!), this is still a simple sentence as it follows the SVO structure:

Subject = research

Verb = reveals

Object = that an active lifestyle can have a great impact for the good on the life expectancy of the average person.

Though basic in construction, it is essential to point out that a simple sentence is often the perfect structure to deal with complex ideas. Simple sentences can effectively provide clarity and efficiency of expression, breaking down complex ideas into manageable chunks.

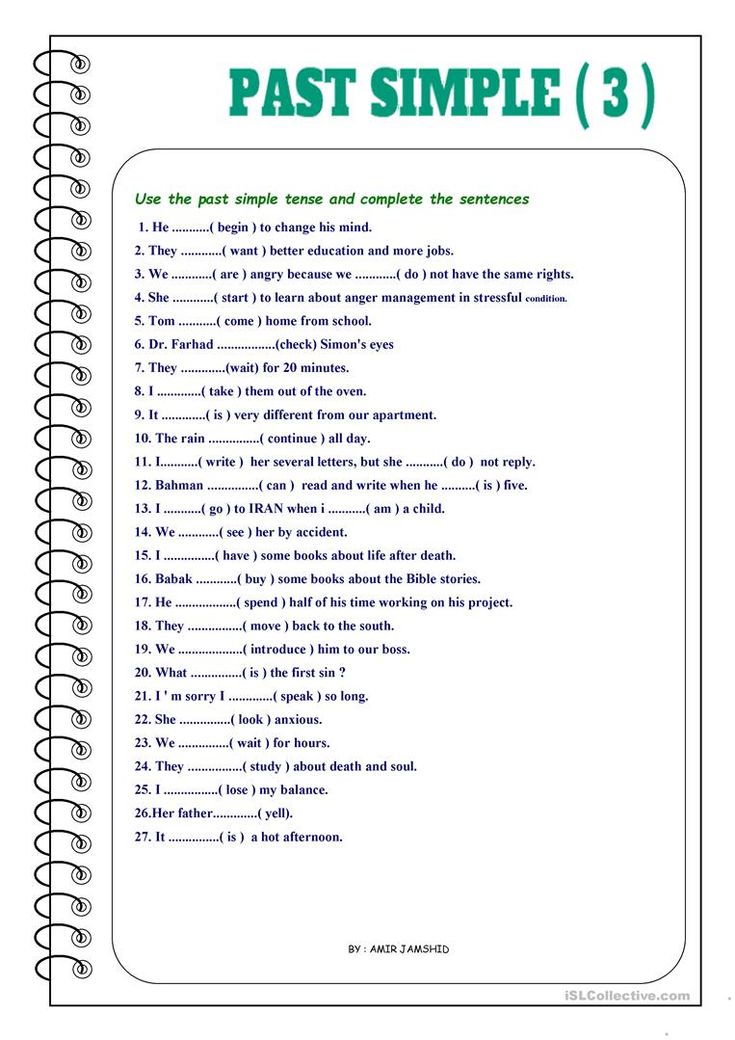

Simple Sentence Reinforcement Activity

To ensure your students grasp the simple sentence structure, have them go through a photocopied text pitched at a language level suited to their age and ability.

On the first run-through, have students identify and highlight simple sentences in the text. Then, students should use various colors of pens to pick out and underline the subject, the verb, and the object in each sentence.

This activity helps ensure a clear understanding of how this structure works, as well as helping to internalize it. This will reap rich rewards for students when they come to the next stage, and it’s time for them to write their own sentences using this basic pattern.

After students have mastered combining subjects, verbs, and objects into both long and short sentences, they will be ready to move on to the other three types of sentences, the next of which is the compound sentence.

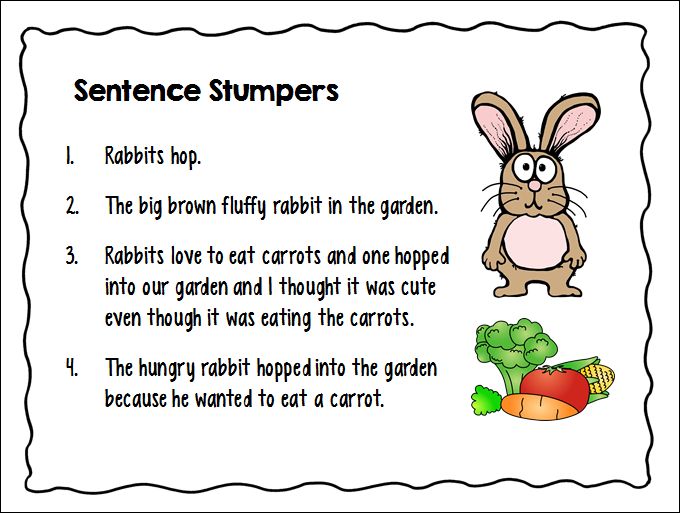

FOLLOW THESE EXAMPLES TO MAKE SENSE OF SIMPLE, COMPLEX AND COMPOUND SENTENCES

Reinforcement Activity

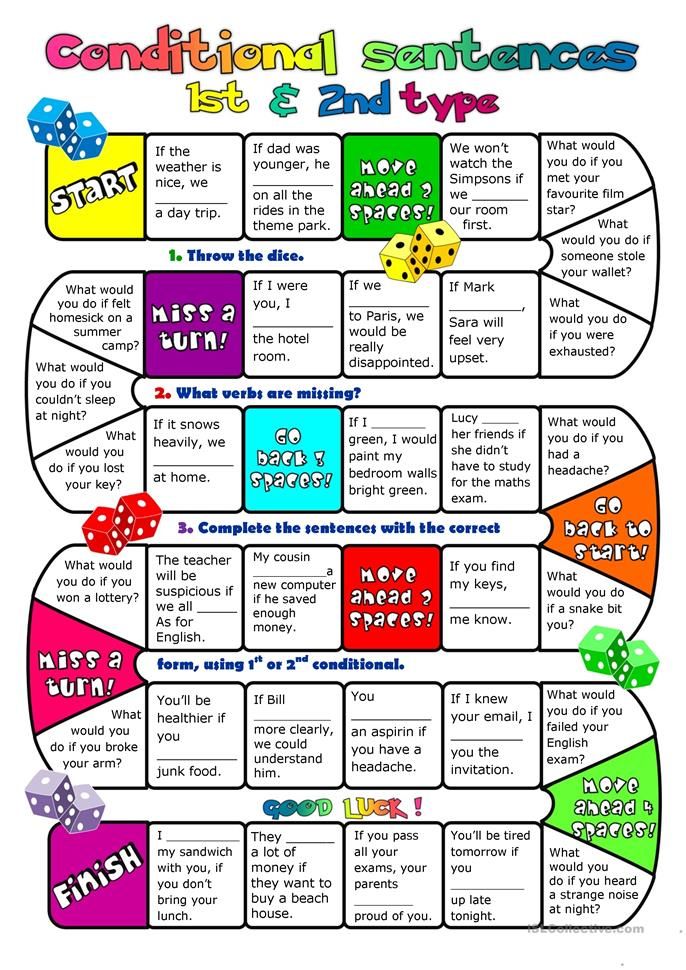

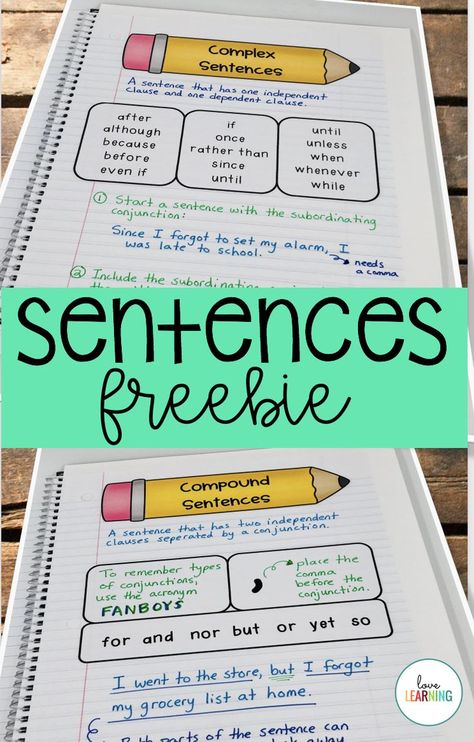

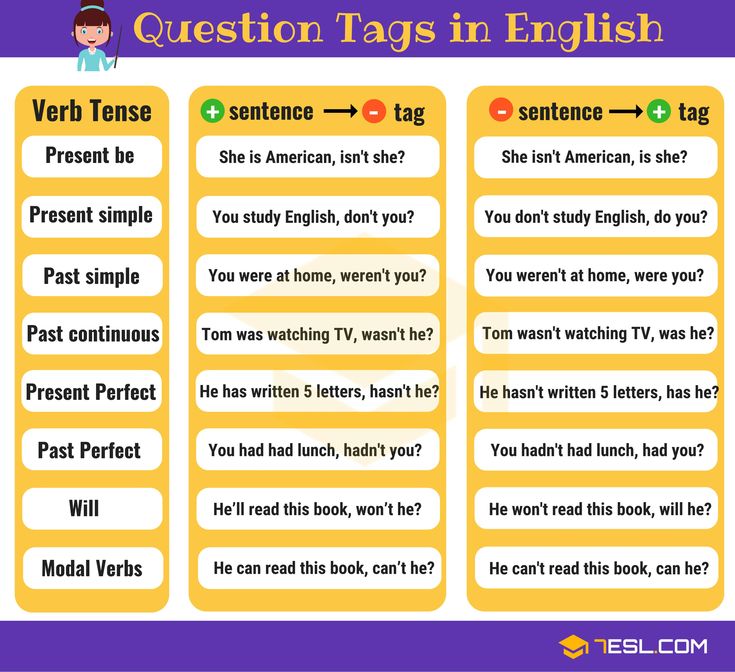

COMPOUND SENTENCE STRUCTUREWhile simple sentences consist of one clause with a subject and a verb, compound sentences combine at least two independent clauses that are joined together with a coordinating conjunction.

There’s a helpful acronym to help students remember these coordinating conjunctions; FANBOYS.

For

And

Nor

But

Or

Yet

So

Some of these conjunctions will be more frequently used than others, with the most commonly used being and, but, or, and so.

Whichever of the conjunctions the student chooses to use, it will connect the two halves of the compound sentence – each of which could stand alone as a complete sentence.

Compound sentences are an important way of bringing variety and rhythm to a piece of writing. The decision to join two sentences together into one longer compound sentence is made because there is a strong relationship between the two, but it is important to remind students that they need not necessarily be joined as they can remain as separate sentences.

The decision to join or not is often a stylistic one.

For example, the two simple sentences:

1. She ran to the school.

2. The school was closed.

It can be easily joined together with a coordinating conjunction that reveals an essential relationship between the two:

She ran to the school, but the school was closed.

As a bonus, while working on compound sentences, a convenient opportunity arises to introduce the correct usage of the semicolon. Often, where two clauses are joined with a conjunction, that conjunction can be replaced with a semicolon when the two parts of the sentence are related, for example:

She ran to the school; the school was closed.

While you may not wish to muddy the waters by introducing the semicolon while dealing with compound sentences, more advanced students may benefit from making the link here.

Reinforcement Activity:

THESE BOOKS CONTAIN RHYMING PATTERNS, WHICH IS PERFECT FOR THIS ACTIVITYA good way for students to practice forming compound sentences is to provide them with copies of simple books from early on in a reading scheme. Books for emergent readers are often written in simple sentences that form repetitive patterns that help children internalize various language patterns.

Books for emergent readers are often written in simple sentences that form repetitive patterns that help children internalize various language patterns.

Challenge your students to rewrite some of these texts using compound sentences where appropriate. This will provide valuable practice in spotting such opportunities in their writing and experience in selecting the appropriate conjunction.

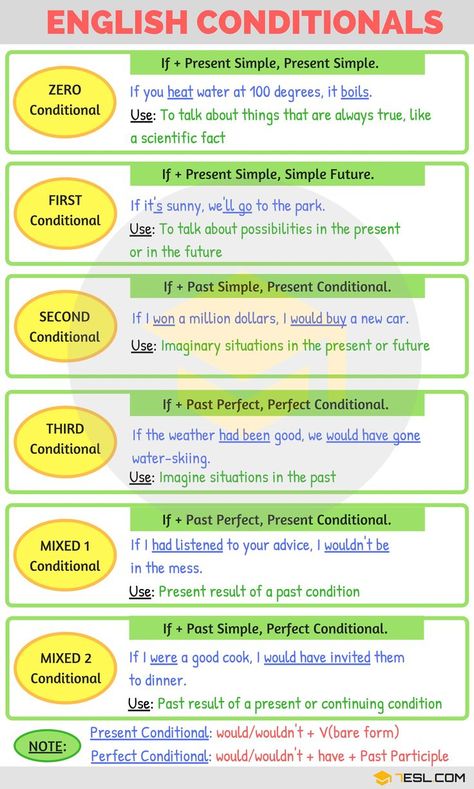

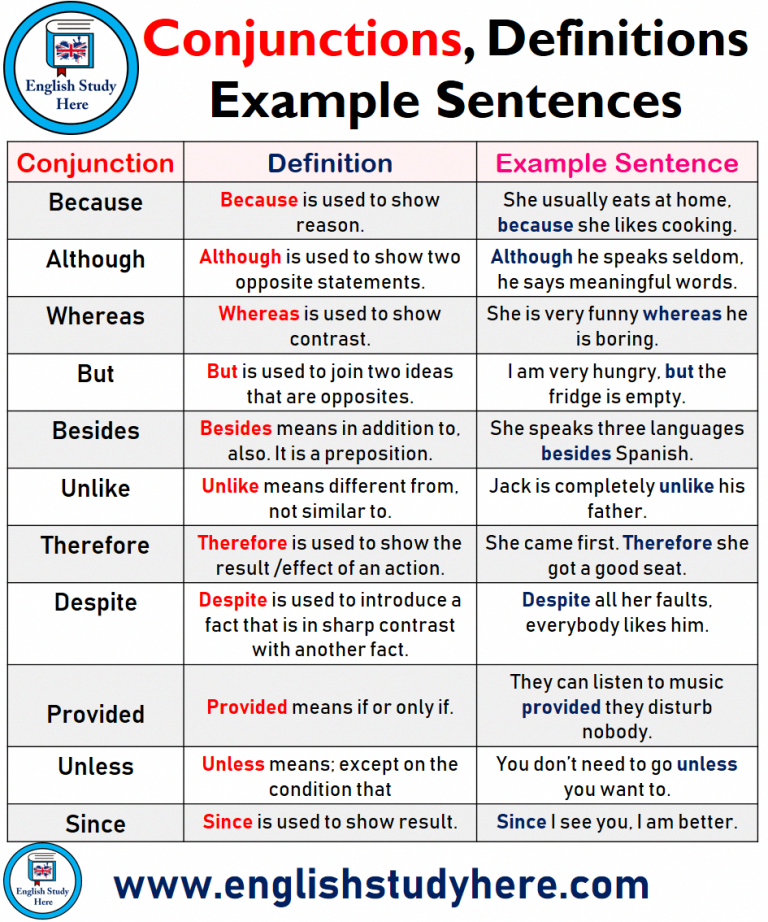

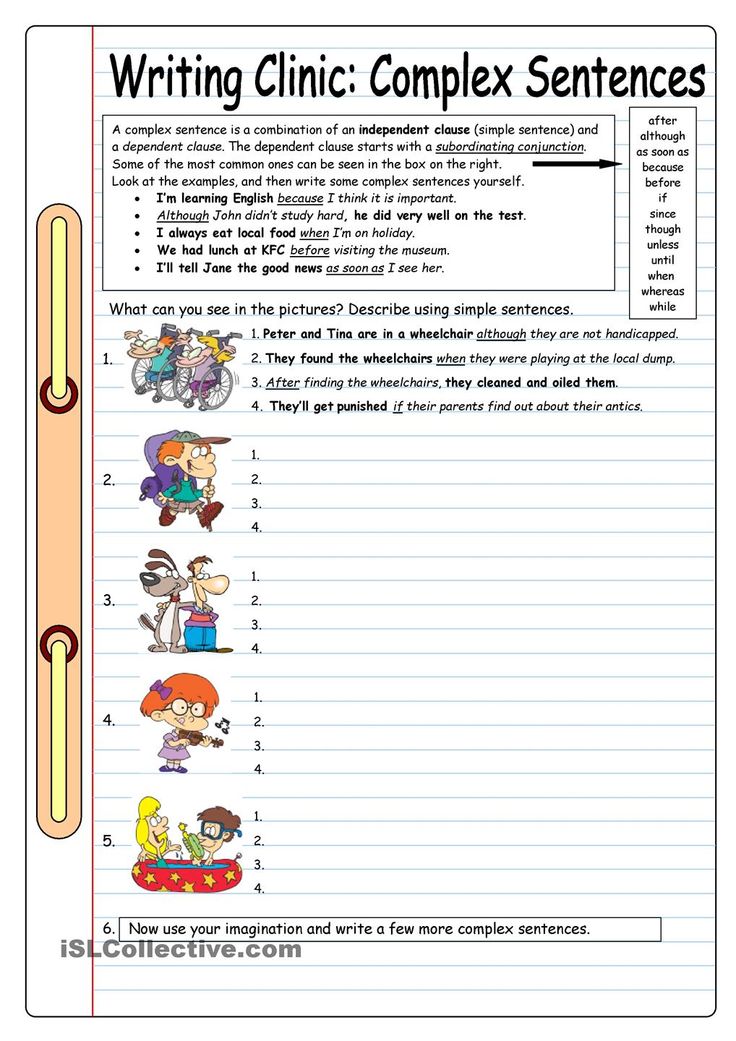

COMPLEX SENTENCESThere are various ways to construct complex sentences, but essentially any complex sentence will contain at least one independent and one dependent clause. However, these clauses are not joined by coordinating conjunctions. Instead, subordinating conjunctions are used.

Here are some examples of subordinating conjunctions:

● after

● although

● as

● as long as

● because

● before

● even if

● if

● in order to

● in case

● once

● that

● though

● until

● when

● whenever

● wherever

● while

Subordinating conjunctions join dependent and independent clauses together. They provide a transition between the two ideas in the sentence. This transition will involve a time, place, or a cause and effect relationship. The more important idea is contained in the sentence’s main clause, while the less important idea is introduced by the subordinating conjunction.

They provide a transition between the two ideas in the sentence. This transition will involve a time, place, or a cause and effect relationship. The more important idea is contained in the sentence’s main clause, while the less important idea is introduced by the subordinating conjunction.

For example:

Although Catherine ran to school, she didn’t get there in time.

We can see that the first part of this complex sentence (in bold) is a dependent clause that cannot stand alone. This fragment begins with the subordinating conjunction ‘although’ which joins it to, and expresses the relationship with, the independent clause which follows.

When complex sentences are organized this way (with the dependent clause first), you’ll note the comma separates the dependent clause from the independent clause. If the structure is reorganized to place the independent clause first, with the dependent clause following, then there is no need for this comma.

For example:

You will not do well if you refuse to study.

Complex sentences can be great tools for students to not only bring variety to their writing but to explore complex ideas, set up comparisons and contrasts, and convey cause and effect.

Reinforcement Activity

A helpful way to practice writing complex sentences is to provide students with a subordinating conjunction and dependent clause and challenge them to provide a suitable independent clause to finish out the sentence.

For example:

After returning home for work,…

or,

Although it was late,…

You may also flip this and provide the independent clause first before challenging them to come up with a suitable dependent clause and subordinating conjunction to finish out the sentence.

DOWNLOAD OUR 52 DIGITAL WRITING JOURNAL TASKS

Our FUN TEN-MINUTE DAILY WRITING TASKS will teach your students the fundamentals of creative writing across all text types. 52 INDEPENDENT TASKS are perfect for DISTANCE LEARNING.

52 INDEPENDENT TASKS are perfect for DISTANCE LEARNING.

These EDITABLE Journals are purpose-built for DIGITAL DEVICES on platforms such as Google Classroom, SeeSaw and Office 365. Alternatively, you can print them out and use them as a traditional writing activity.

30+ 5-star Ratings ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

$3.95 Download from TpT

COMPOUND-COMPLEX SENTENCESCompound-complex sentences are, not surprisingly, the most difficult for students to write well. If, however, your students have put the work in to gain a firm grasp of the preceding three sentence types, then they should manage these competently with a bit of practice.

Before teaching compound-complex sentences, it’ll be worth asking your students if they can make an educated guess at a definition of this type of sentence based on its title alone.

The more astute among your students may well be able to work out that a compound-complex sentence refers to joining a compound sentence with a complex one. More accurately, a compound-complex sentence combines at least two independent clauses and one dependent clause.

More accurately, a compound-complex sentence combines at least two independent clauses and one dependent clause.

Since the school was closed, Sarah ran home and her mum made her some breakfast.

We can see here the sentence begins with a dependent clause followed by a compound sentence. We can also see a complex sentence nestled there if we look at the bracketed content in the version below.

(Since the school was closed, Sarah ran home) and her mum made her some breakfast.

This is a fairly straightforward example of complex sentences, but they can come in lots of guises, containing lots more information while still conforming to the compound-complex structure.

For example:

Because most visitors to the city regularly miss out on the great bargains available here, local companies endeavor to attract tourists to their businesses and help them understand how to access the best deals the capital has to offer.

A lot is going on in this sentence, but it follows the same structure as the previous one on closer examination. That is, it opens with a dependent clause (that starts with subordinating conjunction) and is then followed by a compound sentence.

With practice, your students will soon be able to quickly identify these more sophisticated types of sentences and produce their own examples.

Compound-complex sentences can bring variety to a piece of writing and help articulate complex things. However, it is essential to encourage students to pay particular attention to the placement of commas in these sentences to ensure readers do not get confused. Encourage students to proofread all their writing, especially when writing longer, more structurally sophisticated sentences such as these.

Reinforcement Activity:

You could begin reinforcing student understanding of compound-complex sentences by providing them with a handout featuring several examples of this type of sentence.

Working in pairs or small groups, have the students identify and mark the independent clauses (more than 1) and dependent clauses (at least 1) in each sentence. When students can do this confidently, they can then begin to attempt to compose their own sentences.

Another good activity that works well as a summary of sentence structure work is to provide the students with a collection of jumbled sentences of each of the four types.

Challenge the students to sort the sentences into each of the four types. In a plenary, compare each group’s findings and examine those sentences where the groups disagreed on their categorization.

In teaching sentence structure, it is essential to emphasize to our students that though the terminology may seem quite daunting at first, they will quickly come to understand how each structure works and recognize them when they come across them in a text.

Much of this is often done by feel, especially for native English speakers. Just as someone may be a competent cyclist and struggle to explain the process verbally, grammar can sometimes feel like a barrier to doing.

Be sure to make lots of time for students to bridge the gap between the theoretical and the practical by offering opportunities to engage in activities that allow students to get creative in producing their own sentences.

WRITING CHECKLISTS FOR ALL TEXT TYPES

CLICK TO DOWNLOAD THESE WRITING CHECKLISTS

WHAT IS A SENTENCE FRAGMENT?

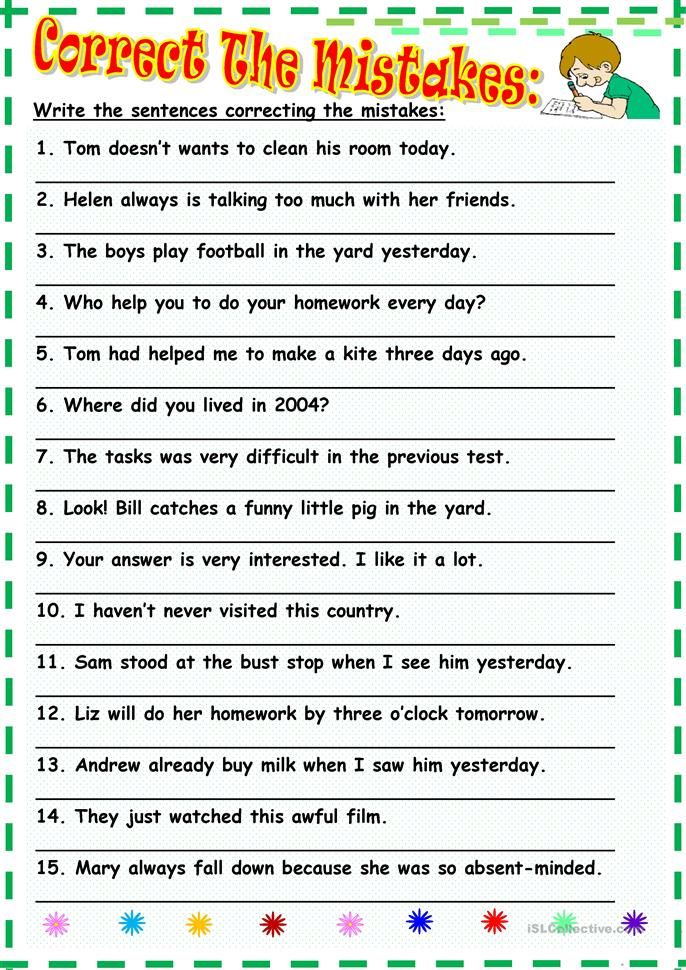

A sentence fragment is a collection of words that looks similar to a sentence but actually isn’t a complete sentence. Sentence fragments usually lack a subject or verb or don’t express a complete thought. Whilst a fragmented sentence can be punctuated to appear similar to a complete sentence; it is no substitute for a sentence.

Sentence fragment features:

These are the distinguishing features of a sentence fragment:

- It lacks a subject

- Example: Jumped further than a Kangaroo. (Who jumped?)

- It lacks a verb or has the wrong verb form

- Example: My favorite math teacher.

(What did the teacher do or say?)

(What did the teacher do or say?)

- Example: My favorite math teacher.

- It is a residual phrase

- Example: For better or worse. (What is better or worse? What is it modifying?)

- It is an abandoned clause

- Example: When my mother married my father. (What happened when “my mother married my father?”)

- It is an improper use of “such as, for example, especially,” etc.

- Example: Such as, my brother was practising martial arts. (It is unclear; did something happen when my brother was practising martial arts?)

The methods for correcting a sentence fragment are varied, but essentially it will boil down to three options. Either attach it to a nearby sentence, revise and add the missing elements or rewrite the entire passage or fragment until they are operating in sync with each other.

SENTENCE STRUCTURE VIDEO TUTORIALS

OTHER GREAT ARTICLES RELATED TO SENTENCE STRUCTURE

The content for this page has been written by Shane Mac Donnchaidh. A former principal of an international school and English university lecturer with 15 years of teaching and administration experience. Shane’s latest Book, The Complete Guide to Nonfiction Writing, can be found here. Editing and support for this article have been provided by the literacyideas team.

A former principal of an international school and English university lecturer with 15 years of teaching and administration experience. Shane’s latest Book, The Complete Guide to Nonfiction Writing, can be found here. Editing and support for this article have been provided by the literacyideas team.

Sentences with the word "study"

We found 80 sentences with the word "study". Synonyms for study. Meaning of the word. Characters. "study" - morphemic analysis.

- The study of Roman law had a great influence on Calvin's mental development.

- After all, studying Afghans doesn't seem to be my job here.

- At first, Fanny and Horatio dreamed of spending the winter in France, where the head of the family could continue learning French.

- During his stay in the fortress, the prisoner spent learning English.

- He fixed a week of time for this undertaking and, having bought somewhere a textbook of Laugier's harmony, immersed himself in the study of this harmony.

- True, a more objective study of the question shows that even this only Jew did not play any such "active role".

- But the study of law did not absorb all of Montesquieu's time.

- Study of the material part of the Shpagin submachine gun.

- At this time he went into the forerunners of Shakespeare, in studying Taine's studies on the Old English theatre.

- In my time the study of Russian ended in an incomplete secondary school.

- Have you informed anyone that you are studying these Afghans?

- In his opinion, " the study of the ancients must be a true introduction to philosophy."

- A thorough study of the flight area was also obligatory.

- Soon the members of the commission delved into the study of activities of the administration in the defense sector.

- I set as my task a deep independent study of the diagnosis and therapy of purulent diseases.

- The study of special literature went in parallel with independent research.

- The foregoing does not mean that a beginner hand-to-hand fighter should immediately sit down for study of laws of mechanics.

- Studying methods of using this new technique in combat in cooperation with the infantry.

- The study of physical and mathematical sciences gave Kant's mental activity a completely new direction.

- The study of the philosophy of Schelling and Hegel has become a real cult.

- The study of Latin syntax has already begun in this class.

- All the more necessary is such a study to evaluate the great work of the Scottish philosopher.

- Under the influence of Wittenbach, young people left the church fathers and enthusiastically set about studying St.

- And studying this lasts for years, until the flight itself.

- So, the small Poquelin plunged into the study of Plautus, Terence and Lucretius.

- The course of international law, the study of higher mathematics and physics were also compulsory.

- The need to move as far as possible the study of exegesis and Semitic philology prompts him to study the German language.

- Months spent in the archives, study of previously almost inaccessible historical sources allowed me to identify an important pattern.

- In "David Copperfidd" we have a vivid description of how difficult it was for him to study this art.

- Characteristically, the formalists also came to it in the late 1920s, trying to solve this problem in study "literary life".

- Here a thorough study of the Hebrew language and the Bible led him, so to speak, to the primary sources of Christian dogmas.

- The study of these questions is the subject of our work.

- The study of , based on the indications of our external senses, gives us only an approximate knowledge.

- How did this study progress, how was Dehn's theory given to Dargomyzhsky without the living guidance of the author of the manuscripts?

- Started study of flight disciplines: aerodynamics, navigation, aircraft operation.

- The study of the specifics of publicistic skill is obviously as difficult a process as the study of the skill of fiction.

- Not only the adoption of Orthodoxy and the study of the language made her "Russian".

- Gradually, introducing the Unified State Examination, we redistributed hours for study of this or that subject.

- The study of sources and archival data allowed me to compile a list of the organizers and the most active participants in bullying.

- The only useful occupation at that time for him was the independent study of multiplication tables.

- https://sinonim.org/

- Following this, he plunged headlong into the study of the work of the Berlin professor.

- Attentive study of archival documents shows that this case is completely invented.

- A professional study not only of cinema itself, but also study of oneself within the framework of cinema has begun.

- To be honest, learning the arts was only the beginning of my problems.

- One can safely say that Rubakin was the first to point out that in book business the study of the reader is just as important as the study of the writer.

- I'm not talking about Oriental languages, which are extremely difficult to study and there are very few means.

- So, shortly after moving to Lille, Pasteur began studying the fermentation process.

- We were already well trained in the motorist program, and the transition to to study the tank was easy for us.

- In order to improve the efficiency of activities, their study is carried out and directed change.

- In the first month of his stay in the regiment, Bonaparte spent all his time on studying the artillery service.

- Here, at leisure, using the rich monastery library, Zwingli completely retired to study St.

- The annual program included the study of foreign languages, special disciplines, certain aspects of the history of the CPSU (b), regional studies.

- Both jurisprudence and the study of the German language had too much influence on him.

- The study of Latin became very interesting (of course, only for the minority and for the teacher).

- The study of historical sciences confirmed his idea that only a merciless manifestation of the will can lead to power.

- The study of his religious and philosophical journalism of the 1840s has just begun.

- There was very little time left for study of equipment during working hours.

- The course was based on the basics of human behavior.

- The study of new methods of using infantry weapons in combat and practice in managing modern tactical formations.

- Wasting no time, he set about studying philosophy at its place of origin.

- But even a superficial study of Lenin's letters about the uprising shows quite the opposite.

- I was assigned to the fifth grade of a school where it was obligatory to study the Tatar language.

- Perhaps, in a strictly ecclesiastical and moral sense, this study of brought rich fruits, but it influenced the brain in an amazing way.

- He had a deep respect for Scripture and tried to introduce its study into monasteries subordinate to him.

- Having recovered, I again enthusiastically took up the study of my favorite subjects: history, geography and mathematics.

- Then Monty began to study engineering, but here too he was in for a failure, as he was weak in mathematics.

- An idea of him can be given, first of all, by studying the poet's reading circle and his notes in the margins of the books he has read.

- Continued study of the German language, flight operations manuals (NMP).

- The study of is not the method of these random and personal notes.

- This was a translation of Eshenburg's work, from whose works Zhukovsky began his study of aesthetics [Yanushkevich 1984].

- According to the instructions, they were required to behave decently, diligent study of sciences, after which practical study of mines.

- The study of planetary movements is essential.

- After the change that had taken place in her outlook on the world, she began to study philosophy with particular enthusiasm.

- These investigations continue to this day, bringing new light to the study of both the life and works of the great Spanish genius.

- The study of economic theory was a kind of ritual sacrifice.

- Probably partly under their influence, Rabelais set to work on studying law and even gained some notoriety as a knowledgeable jurist.

- The

- cessation of lessons weakened Schumann's musical zeal, but he again set to work with ardor the study of literature.

- On the other hand, with all the greater zeal he took up the study of jurisprudence, in order to victoriously wage the war that had begun, fully armed with legal knowledge.

- At the age of fourteen, Smith entered the University of Glasgow, where he zealously began to study mathematics and natural philosophy.

- The study of languages was, of course, not a goal, but only a means to another, most important cause.

Open other sentences with this word

Source - introductory fragments of books with LitRes.

Synonyms for "study". Meaning of the word. Characters. "study" - morphemic analysis.

We hope that our service has helped you come up with or write an offer. If not, write a comment. We will help you.

Top ↑

Antonyms | Synonyms | Associations | Morphemic parsing of a word | Search for offers online | Sound-alphabetic analysis of the word

Share

- The search took 0.

039 seconds. Remember how often you are looking for something to replace a word with? Bookmark sinonim.org to quickly look up synonyms, antonyms, associations, and sentences.

039 seconds. Remember how often you are looking for something to replace a word with? Bookmark sinonim.org to quickly look up synonyms, antonyms, associations, and sentences.

Random: soiled, immanent, pecked, extravagant, popular print, oil, sea, suffer, some, association

Write, we welcome comments

Up ↑

Studying sentences with attached components in Russian language and literature lessons at school (on the material of I. S. Turgenev's story "Bezhin meadow") »

1UDK 81.367(5) BBK 81.411.2

study of sentences with attached components in Russian language and literature lessons at school

(based on the story by I. S. Turgenev "Bezhin meadow")

E. V. Sevryugina

Today, in schools and even higher educational institutions, the study of such an important type of syntactic connection as attachment is given insufficient attention. Accordingly, the main objectives of this article are: 1) demonstrating possible ways to study connecting sentences at school - in particular, with the involvement of fiction texts that are mandatory for the school curriculum; 2) description of sentences with attached components and identification of the features of their functioning in the texts of word artists. This study is carried out on the material of Turgenev's prose, namely, the story "Bezhin Meadow" is taken as the basis. Analyzing the nature of the use of connecting sentences in Turgenev's prose, we take into account external and internal factors, that is, both the objective laws of the language process and idiostyle features. Main research methods: method of comparative and contextual analysis. The materials of this article can be used in the practice of school teaching of the Russian language and literature.

This study is carried out on the material of Turgenev's prose, namely, the story "Bezhin Meadow" is taken as the basis. Analyzing the nature of the use of connecting sentences in Turgenev's prose, we take into account external and internal factors, that is, both the objective laws of the language process and idiostyle features. Main research methods: method of comparative and contextual analysis. The materials of this article can be used in the practice of school teaching of the Russian language and literature.

Keywords: addition, attached components, proposition, modus, author's intention.

the study of sentences wiTH attached components

on the lessons of RussiAN language and uterature at school studying of such important type of a syntactic link as connection, is paid insufficient attention to. So the main task of this article is: 1) to demonstrate possible ways of studying the connecting sentences at school using the texts of fiction obligatory for the school program in particular; 2) to describe the sentences with the connected components and detect the features of their functioning in the texts. This research is conducted on the material of Turgenev's prose, namely on the story "Bezhin Meadow". Analyzing the nature of the use of connecting sentences in Turgenev's prose, the authors consider external and internal factors, that is both objective regularities of language process and the features of idiostyle. The basic methods of research are the method of the comparative and contextual analysis. The materials of this article can be used in school practice and teaching Russian language and literature.

This research is conducted on the material of Turgenev's prose, namely on the story "Bezhin Meadow". Analyzing the nature of the use of connecting sentences in Turgenev's prose, the authors consider external and internal factors, that is both objective regularities of language process and the features of idiostyle. The basic methods of research are the method of the comparative and contextual analysis. The materials of this article can be used in school practice and teaching Russian language and literature.

Keywords: connection, connected components, proposition, modus, the author's intention.

Since the time of AS Pushkin, sentences with attached components have become an integral part of written speech. Representing initially living conversational constructions, these types of sentences become for word artists a powerful means of linguistic expression, as well as a way of artistic embodiment of the author's intentions and emotional states.

The main way of penetration of connecting constructions into the literature was their linguistic adaptation to the traditional Russian syntax with its characteristic means of grammatical and logical connection of words in phrases and sentences. These means, first of all, include unions and allied words, namely, three groups of allied means: 1) proper connecting unions; 2) coordinating conjunctions in

These means, first of all, include unions and allied words, namely, three groups of allied means: 1) proper connecting unions; 2) coordinating conjunctions in

connection value; 3) subordinating unions in the connecting meaning.

Non-union means of connection of the basic and attached parts of the sentence were also found in the texts of fiction in the first half of the 19th century, but much less frequently. For example, in Pushkin's story "The Captain's Daughter" there are a total of 71 sentences with an allied connection, and only 11 with an allied one. Sentences with additions also played a special role in Pushkin's poetry. For example, V. V. Vinogradov, referring to V. Solovyov in his work “Language and Style of Pushkin”, notes that the poet “took from biblical poetry only that which deepened, replenished and sharpened his “European” syntax, his previously defined system artistic composition based on the principles of "discontinuous", connecting structures" [1, p. 132]. Thus, starting from Pushkin, sentences with attached parts become an important means of expressive syntax.

Thus, starting from Pushkin, sentences with attached parts become an important means of expressive syntax.

Connecting sentences continue to be actively used in the second half of the 19th century: Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, and almost all prominent writers of that era turn to these constructions.

We come across the original, authorial use of sentences with attached components in the prose of IS Turgenev. To more specifically describe the nature of the functioning of these syntactic constructions in Turgenev's texts, let us turn to his story "Bezhin Meadow". In doing so, we will take into account such aspects as: 1) ways of grammatical expression of the connecting connection; 2) features of the content expressed by the connecting structure; 3) stylistic function in the text.

So, in the story "Bezhin Meadow" there are many connecting sentences with a traditional allied connection. Among them there are also proposals with actually connecting unions:

1. The small one was unsightly - to be sure! But all the same, I liked him: he looked very intelligent and direct, and there was strength in his voice.

The small one was unsightly - to be sure! But all the same, I liked him: he looked very intelligent and direct, and there was strength in his voice.

2. No, I didn't see him, and you can't even see him... but I heard... and I'm not the only one.

3. My brother Avdyushka and I had to, and Fyodor Mikheevsky, and Ivashka Kosy, and another Ivashka from Red Hills, and even

with Ivashka Sukhorukov, and there were other kids there too.

4. So she calls him, and she is all fair, white, sitting on a branch, like some kind of small fish or gudgeon - otherwise crucian carp can be so whitish, silver ...

5. The damp freshness of the late evening has changed midnight dry warmth, and for a long time it was to lie in a soft canopy on the dormant fields; there was still a lot of time left before the first babble, before the first rustles and rustles of the morning, before the first dewdrops of dawn.

As you can see, most often Turgenev's proper adjunctive conjunctions are combinations of a coordinating conjunction with a particle. As a rule, this is the union "yes" (1-3rd sentence), or the unions "and" (4th sentence) and "a" (5th sentence). They are joined by amplifying ("yes," "yes," "and more") and indicative ("otherwise") particles.

As a rule, this is the union "yes" (1-3rd sentence), or the unions "and" (4th sentence) and "a" (5th sentence). They are joined by amplifying ("yes," "yes," "and more") and indicative ("otherwise") particles.

Sometimes the particle “pulls” the function of the joining union onto itself and is used without it:

then...

2. But there was no way to return home, especially at night; my legs wobbled beneath me from exhaustion.

In some cases, Turgenev expresses the connective connection with the help of coordinating and subordinating conjunctions used in the connecting meaning:

1. He went again to the door above and began to go down the stairs, and in this way he goes down, as if in no hurry; the steps beneath him even groan.

2. So she calls him, and she is all fair, white, sitting on a branch, like some kind of small roach or gudgeon.

3. . I cry, I am hurt because you were baptized; Yes, I will not be the only one to be killed: be killed, and you until the end of days.

Turgenev most often uses the unions “and” and “da” in the meaning of “and” as the conjunctions of the connecting meaning. Subordinating conjunctions of a similar function are practically not found in Turgenev's story.

A striking distinguishing feature of the use of connecting constructions in the story “Be-

zhin meadow”, indicating a gradual transition to modern syntax, is the “tendency towards analyticism” and the informative isolation of the statement. So, in Turgenev, union-free connecting constructions are more common than in Pushkin's prose, and they are very diverse. For example, the writer expresses the connective connection by non-union sentences with lexical repetition:

1. So he sat down under a tree; Come on, they say, I'll wait for the morning, - sat down and dozed off.

2. If the peasants want to take it, for example; they will come out at him with a cudgel, cordon him off, but he will avert their eyes - he will avert their eyes so that they themselves will beat each other.

Also in Turgenev's story we encounter non-union connecting sentences with a secondary member-distributor:

1. He went straight ahead, following the stars - at random ...

3. His boots with low tops were like his boots - not his father's.

In the first example, the propagator member is the adverb of manner, and in the second, the definition.

Particular attention in Turgenev's story deserves those connecting sentences with an allied and non-union connection, in which words-markers of attachment are used. On the basis of our observations, we can conclude that Turgenev’s most often used such marker words are the adverb “suddenly”, emphasizing the suddenness or rapid change of action, and the verb “added” (“added”):

1. First they chatted about this and that, tomorrow's work, about horses; but suddenly Fedya turned to Ilyusha and, as if resuming an interrupted conversation, asked him:

2. - No, more cheeses ... Look, splashed, - he added, turning his face in the direction of the river, - it must be a pike . ..

..

3. Nothing, - answered Pavel, waving his hand at the horse, - so the dogs smelled something. I thought it was a wolf,” he added in an indifferent voice, breathing quickly with all his chest.

4. - A heron, - repeated Kostya... - And what is it, Pavlusha, I heard last night, - he added after a pause, - perhaps you know...

5. I, unfortunately , I must add that in the same year Paul died. He did not drown: he

killed himself by falling from his horse. Too bad, he was a nice guy!

A thorough analysis of this type of sentences in Turgenev's prose allows us to come to the following important conclusions: the marker words used by the writer in the adjunctive construction become an integral part of speech discourse and are perceived as "borders of transition" (sometimes quite sharp) from one proposition to another . This is how one of the key author's intentions (directions of thoughts and feelings) is realized and draws us to the logical-semantic aspect of the connection.

I. S. Lebedeva in her dissertation “Discursive-pragmatic and sociolinguistic characteristics of the functioning of statements with an attached element in the English language” notes that “the description of the semantics of statements with an attached element should be built on the concepts of a proposition (which is contained in the joining part) and mode, as a pronounced psychological state of the speaker at the moment of communication (which is reflected both in the connecting part and in the attached element)" [2, p. 250].

Lebedeva identifies different types of connecting sentences according to the nature of the intentional orientation of the utterance. The author's intentions can be different: this is an assessment of a proposition, and an expression of a psycho-emotional state, and an appeal to oneself or to a potential addressee, and a focus on achieving some goal.

In Turgenev's sentences with an attached element, one can often observe a transition from one proposition to another, a sharp switching of action plans, which can even be expressed in metalanguage words.

It is interesting that syntactic constructions of this kind are used by Turgenev in the context of a certain speech situation - dialogue. Thus, the author's intention becomes more obvious to the reader:

1. First they chatted about this and that, about tomorrow's work, about horses; but suddenly Fedya turned to Ilyusha and, as if resuming an interrupted conversation, asked him:

2. - No, more cheese... Look, splashed, - he added, turning his face in the direction of the river, - it must be a pike...

In both examples, the attached component indicates a sudden change in the original proposition. In the first case, this is a sharp resumption of the interrupted conversation, and Turgenev even includes elements of "metalinguage" in the sentence, conveying the speaker's intentions ("as if resuming the interrupted conversation"). In the second case, this is an unexpected transition from one plane of reality to another. With the help of metalanguage, this can be expressed as follows: the author's attention has switched to another object of the surrounding world.

It is also interesting to note that in Turgenev's story there are such connecting sentences that serve as a significant author's addition to the entire text:

Unfortunately, I must add that in the same year Pavel died. He did not drown: he killed himself by falling off his horse. Too bad, he was a nice guy!

This statement is a completely new, not directly related to the story, plan of the story and also marks a sharp transition from the events of the past to the fact of the present.

In this sense, Turgenev's entire story is an extended connecting structure and demonstrates the unique possibilities of this type of connection, which is capable of performing, among other things, the function of compositional and logical-semantic organization of a literary text.

On the basis of the observations made, we can draw the following conclusions:

1. Since the time of AS Pushkin, sentences with adjuncts have become an important fact of written speech.

2. In Turgenev's story "Bezhin Meadow" there are various types of connecting constructions, including non-union sentences, which, unlike similar constructions in Pushkin's prose, are very diverse.

3. In Turgenev's prose, such types of connecting sentences are often found,

which become an integral part of speech discourse and express a semantic transition from one proposition to another.

4. The experience of analyzing sentences with attached components on the material of Turgenev's prose demonstrates the unique possibilities of this type of connection, which is capable of performing, among other things, the function of compositional and logical-semantic organization of a literary text.

In conclusion, we add that the materials of this article can be used in literature and Russian language classes at school. For example, a small linguistic analysis of Turgenev's story with the involvement of connecting sentences can be carried out either at the stage of initial acquaintance of students with the text of a work of art, or after a detailed study of the content of the story and its artistic features. One can trace, for example, how the language of a literary text, the syntactic constructions used in it, help to reveal the author's intention.

One can trace, for example, how the language of a literary text, the syntactic constructions used in it, help to reveal the author's intention.

Such work contributes to the formation of students' linguistic vigilance, as well as the skills of professional, multi-aspect analysis of a work of art.

list of sources and references

1. Vinogradov, VV Pushkin's style [Text] / VV Vinogradov. - M.: Nauka, 1999.

2. Lebedeva, IS Discursive-pragmatic and sociolinguistic characteristics of the functioning of statements with an attached element in the English language [Text] / IS Lebedeva. - M., 2004.

references

1. Vinogradov V. V. Stil Pushkina. Moscow: Nau-ka, 1999.

2. Lebedeva I.S. Moscow, 2004.

Sevryugina Elena Vyacheslavovna, Candidate of Philological Sciences, Associate Professor of the Russian Language and Literature Department of the Russian State Social University, doctoral student of the Moscow State Pedagogical University e-mail: elena_s2003@list.