Learning your shapes

Why Teach Shapes? Why It Matters and Easy Learning Activities (Plus Printables!)

Why teach shapes? Learn why children need to learn shapes and the best activities to help. Plus printables!

Shapes are one of those things we work on with kids from a young age. We teach what a circle is, a triangle, a square. Colors, letters, numbers, shapes.

These are some of the first things we work on with children.

Colors are easy and fun to point out. Numbers and letters are building blocks for their entire future.

But why do we focus on shapes? Are they just easy?

There are actually some very concrete reasons for teaching toddlers and preschoolers shapes.

Here are 5 big reasons to teach preschoolers and toddlers shapes, plus some fun printables to color or use play-doh for sensory shape fun.

What's In This Post?

- Why Teach Shapes?

- Same or Different

- Categorization

- Problem Solving and Spatial Relations

- Math Skills

- Grab these printables for more shape practice!

- Letter Recognition

- Ways to Learn and Practice Shapes

- Just Talk

- Shape Hunts

- Shape Toys

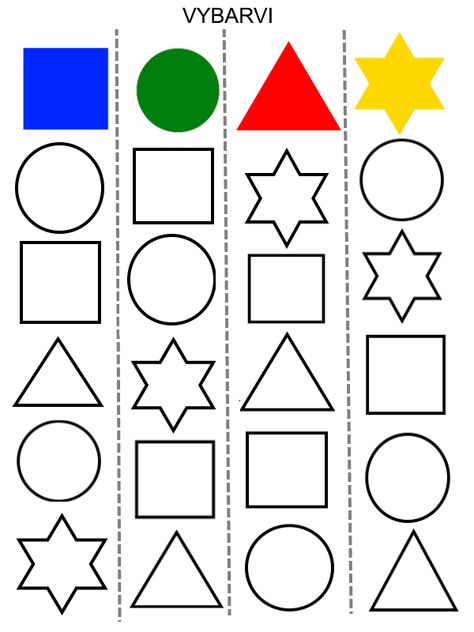

- Coloring and Tracing

- Play-Doh Shapes

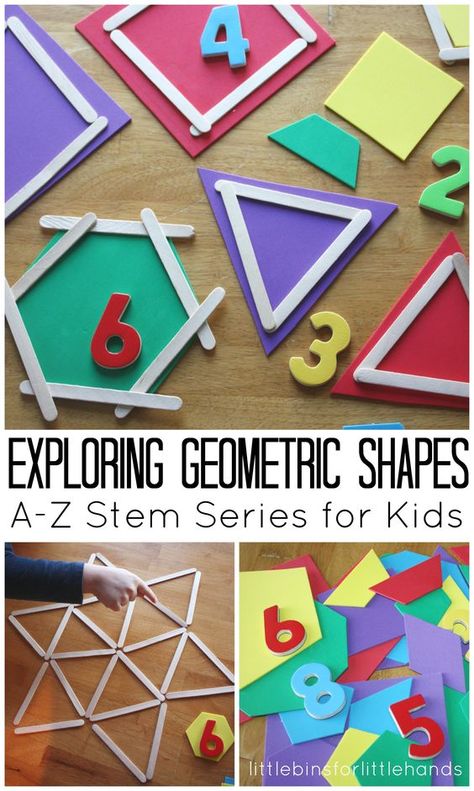

- Shape Sticks

- Shapes Everywhere

- I want the Freebies!

- Thank you!

- Bonus Shape Practice Printables

- Related

Why do we teach shapes to our children?

It isn’t just because it is easy. Shapes are building blocks for several bigger concepts that children will use throughout their schooling and lives.

There are big reasons to start shape learning early. Here are some major concepts they work.

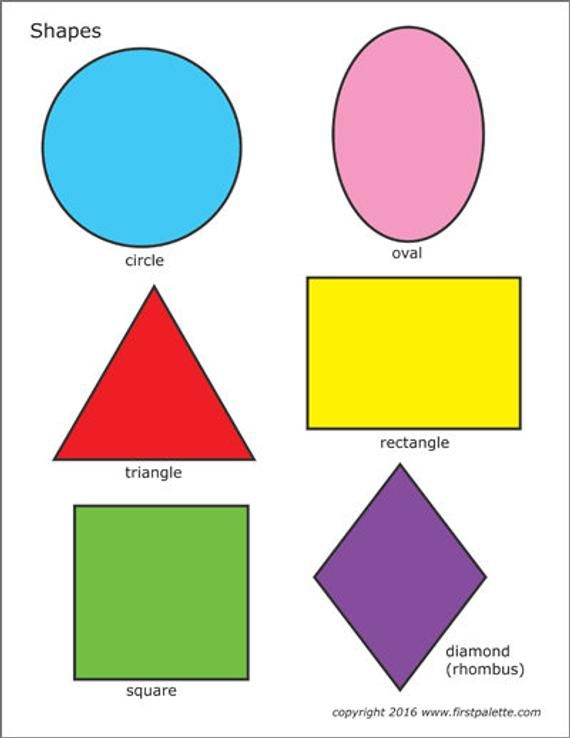

Same or DifferentBasic shapes like circles, triangles, and squares are distinctly different from each other. This makes them great for practicing same and different.

Same and different is the start of really recognizing distinctive traits objects can have. It is also the first level of categorizing.

Are these two objects the same or different? This is the start of basic observation skills.

CategorizationOnce the basic same or different concept is down, children can move into more complicated categorization.

What makes a circle different from a square? This is detailed recognition of traits objects have.

An important skill is being able to find a common characteristic among different items. A great way to practice this is to send your child on a shape hunt.

A great way to practice this is to send your child on a shape hunt.

How many circle objects can they find? How many squares? This shows them that shape is something that many different things can have in common.

Categorization is an important science skill.

Problem Solving and Spatial RelationsShapes are a great way to introduce problem-solving skills.

Take a shape sorter. Your child needs to determine which shape goes in which hole, and then they need to actually fit it in.

This works spatial relation skills as well. How do objects fit together? (As your children grow puzzles work the same sort of skill. How do you recognize what piece fits where?)

Anything that works problem-solving is helpful for children, and this sort of trait recognition is key for future science skills.

Math SkillsI feel math skills are an obvious area that gets worked when you teach your children shapes.

Geometry is in part the study of shapes. Having a basic understanding of them from a young age will make this math class a lot easier for kids.

Having a basic understanding of them from a young age will make this math class a lot easier for kids.

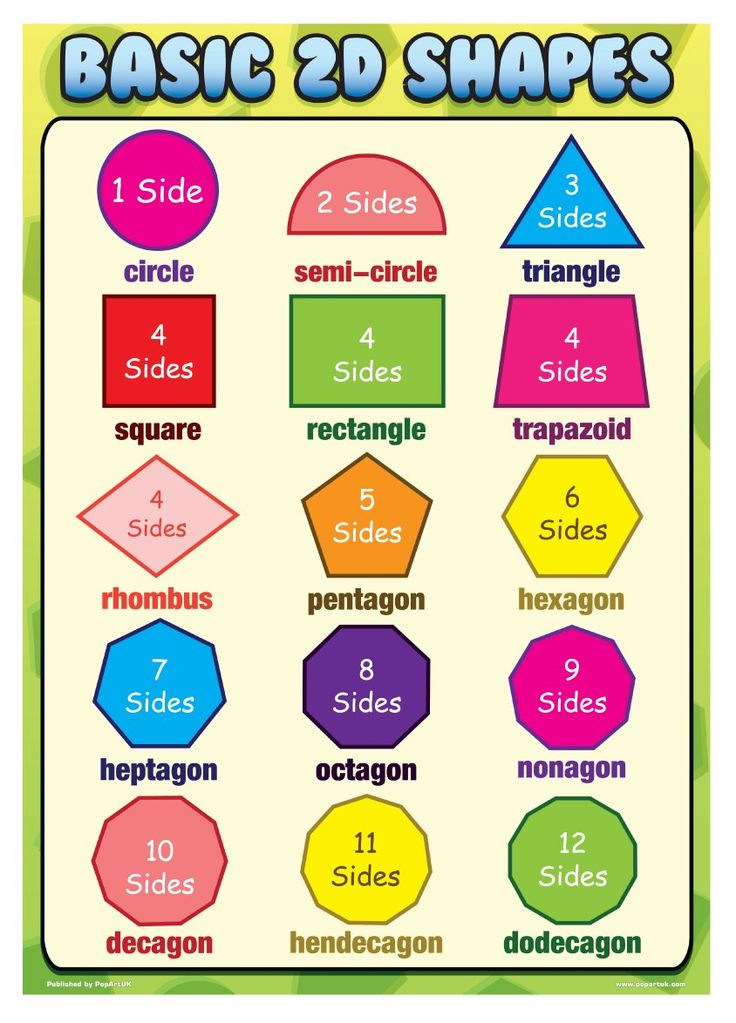

Understanding the characteristics of shapes involves a lot of counting. How many sides does a shape have? This easily folds in number practice when you play with your toddlers and preschoolers.

Pattern recognition comes into play as well. Every time you add a side you get a new shape, this is a pattern. Being able to physically see the difference between a shape with three sides and one with five helps with number sense, a key to all math success.

(Learn more about number sense and why it matters here.)

Grab these printables for more shape practice!

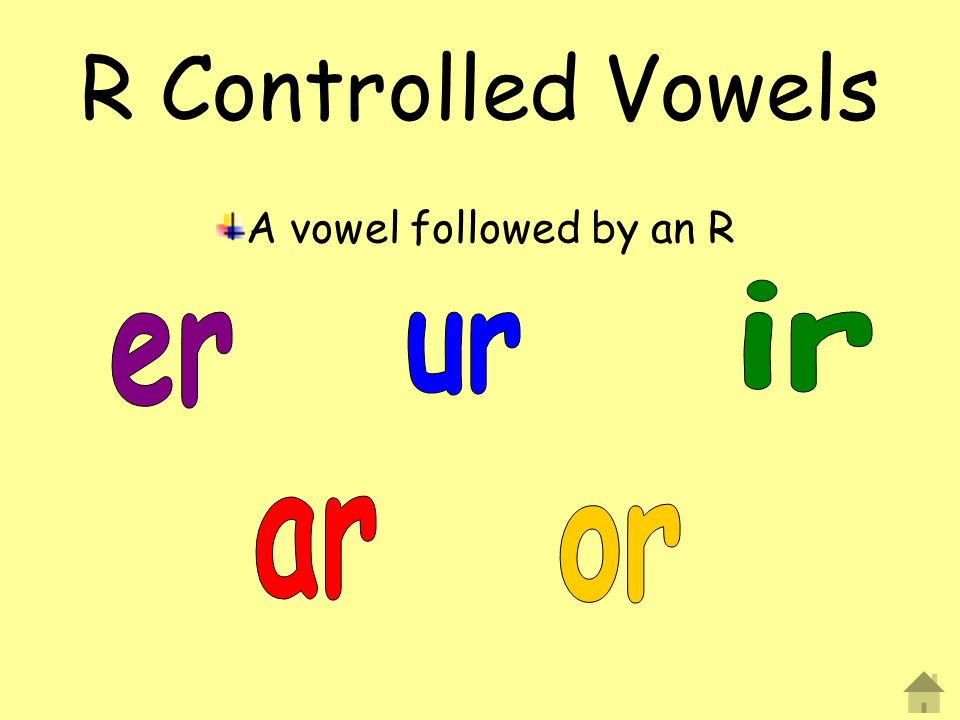

Letter Recognition

This is one of the biggest reasons to work on shapes early. Shapes help with letter recognition.

Think about letters, they are very similar to shapes. The letter V is a triangle missing a side, and the letter O is just a circle.

Understanding what shapes are and that they have meaning starts to build literacy. Practicing distinguishing between a square and a triangle help kids recognize between different letters.

The same is true for reading numerals. Having children draw shapes and working on the lines and angles needed to draw a triangle or rectangle helps them later in life when they are learning to write their letters.

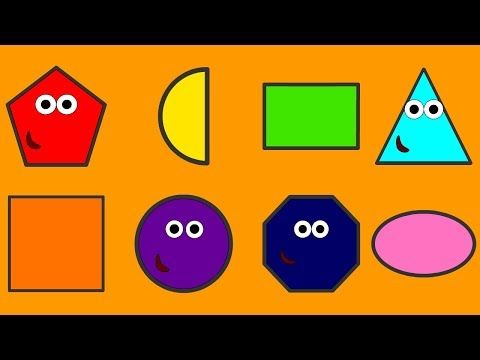

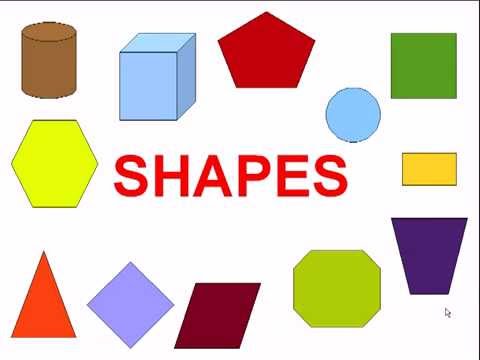

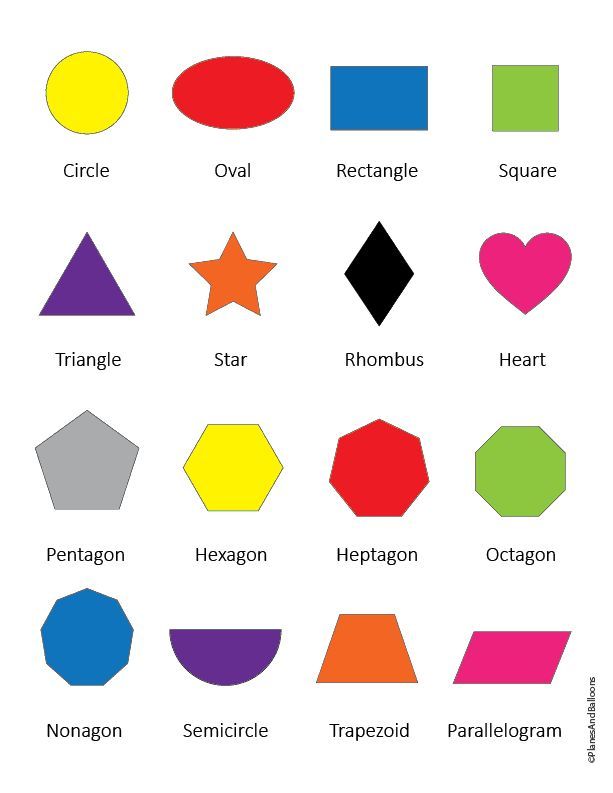

Ways to Learn and Practice ShapesThere are lots of ways to practice shapes. One of my favorite things about this topic is that you can make it more and more challenging as your child learns more and more.

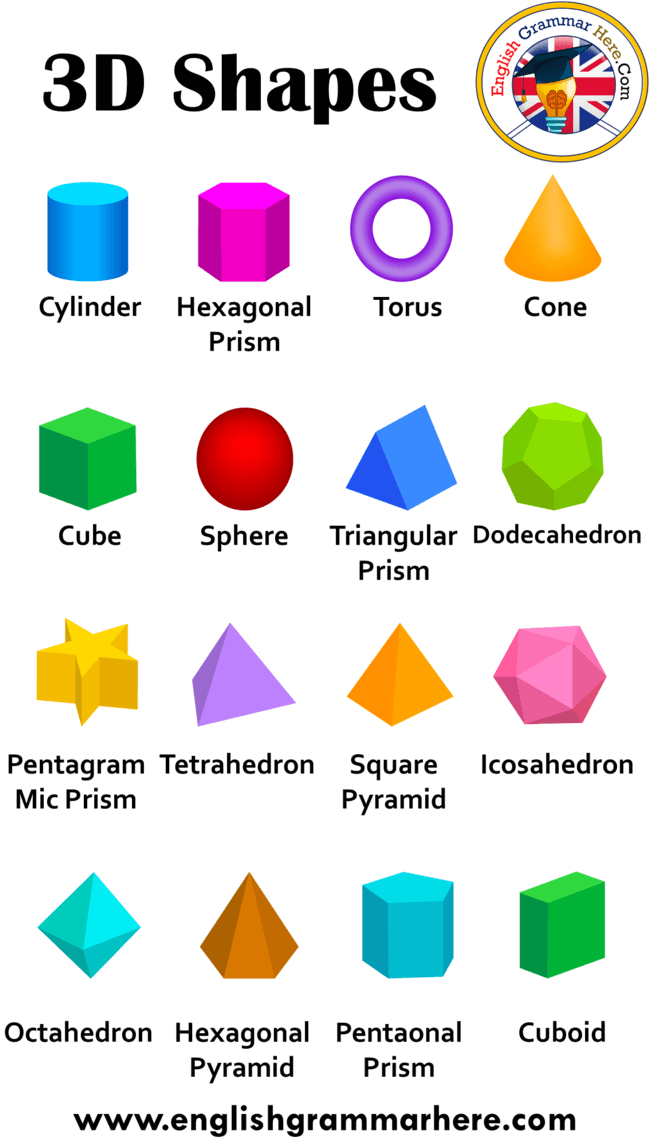

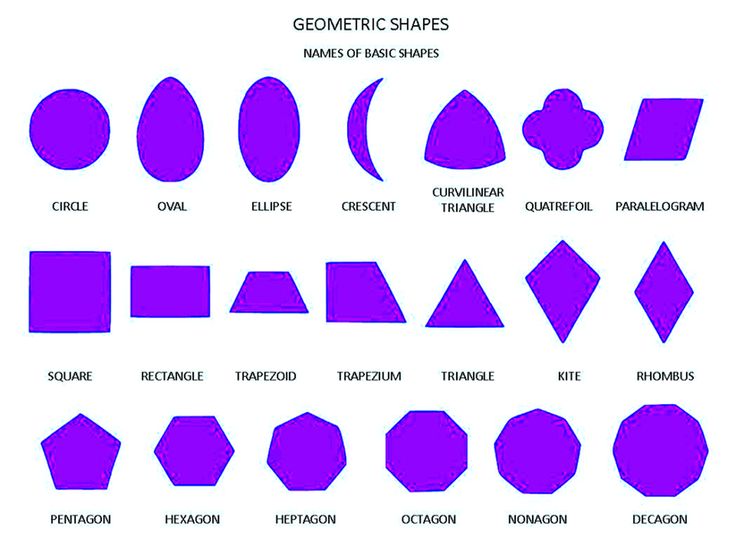

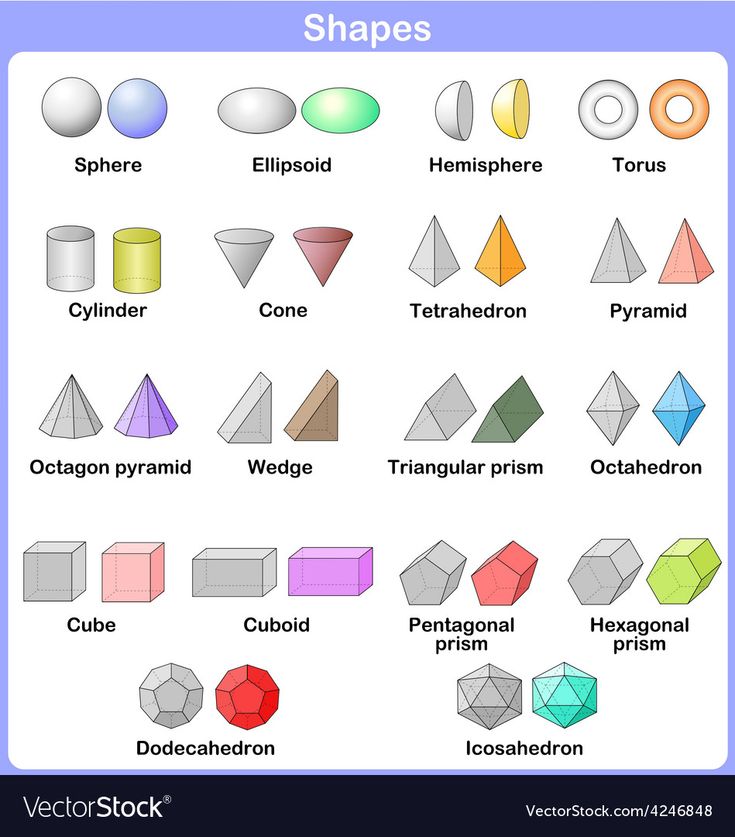

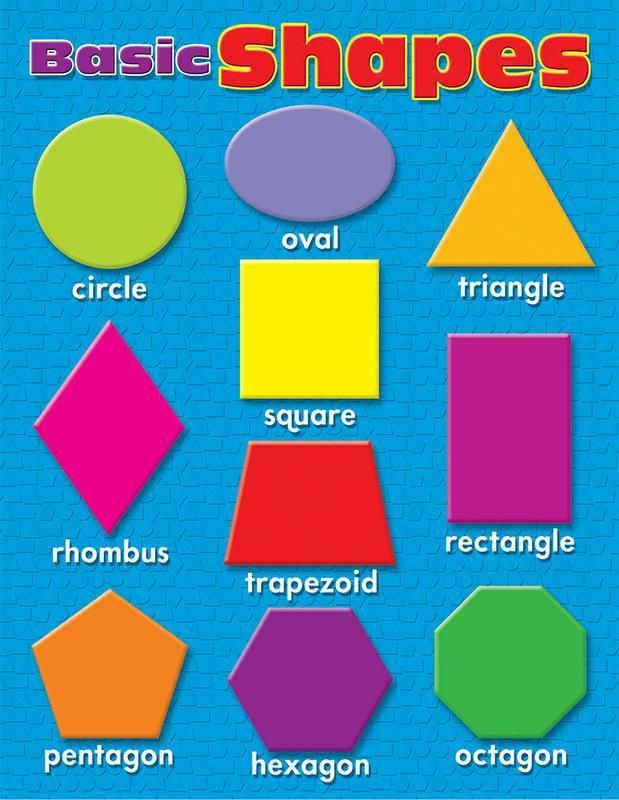

You start with circles, triangles, and squares. Then there are pentagons, hexagons, heptagons, octagons, and more. (This is a great lesson in prefixes too.)

Even with just 4 sides, there are a variety of shapes to work on. Square versus rectangle. Trapezoids, diamonds, parallelograms.

And don’t forget hearts, stars, crescents, and more. There is just so much depth to this simple subject.

There is just so much depth to this simple subject.

Here are some fun and easy ways to work on shapes with your children. Play is key with these.

Just TalkI think we try to make teaching our children too hard sometimes. The simplest way to work on shapes is just to talk about them.

My mother-in-law calls the toddler years the years of two names. Everything you share with your children has two names. For example, you don’t just hand your child a cup you hand them the blue cup. Or we play with the red ball.

Whatever it is, we can naturally add descriptors that are teaching our children. Use shapes the same way. You can read the square book or play with the triangle magnet. You don’t need big explanations, especially with very young toddlers.

Just start using the vocabulary.

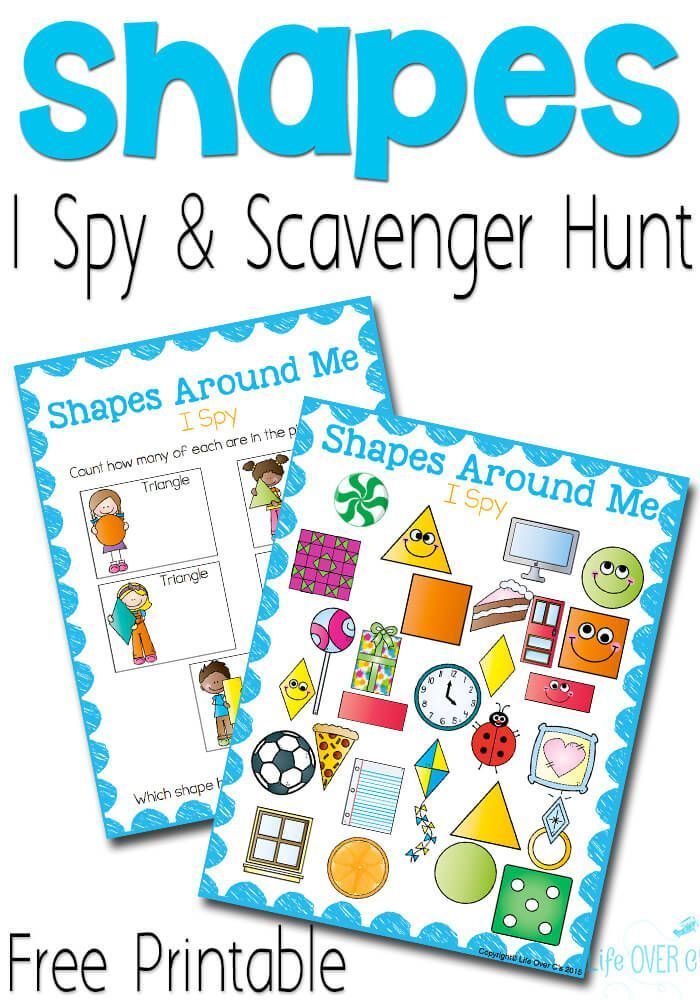

Shape HuntsMy kids love going on scavenger hunts. It doesn’t matter what we are looking for, they adore it.

So send your kids on a shape hunt!

I have my children gather up anything that is triangle shaped, or circles. It is easier to focus on one shape at a time with toddlers. Preschoolers can look for more than one shape at a time, adding in sorting practice along with the shape practice.

It is easier to focus on one shape at a time with toddlers. Preschoolers can look for more than one shape at a time, adding in sorting practice along with the shape practice.

You don’t need anything special for this. Regular household items and kid toys come in all shapes. But if you want to make it more specific, try cutting shapes out of construction paper.

Low cost and easy cleanup.

Shape ToysShape sorters are a staple for a reason. You can find them in every price range. (In fact, Ali and Sammy’s favorite shape sorter came from Walgreens for about $5.)

These sorters practice shape recognition, problem-solving skills, and spatial relations, all in one little toy.

You can even make your own. Grab some blocks or other key shapes and trace them onto a shoebox or other box. Then cut the shapes out and let your children sort!

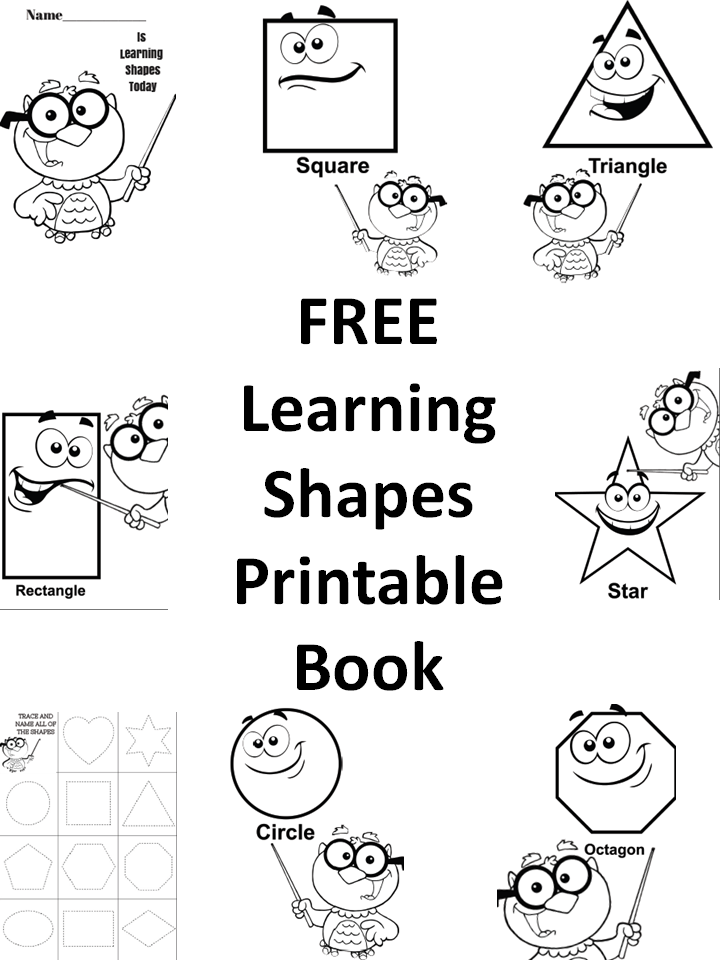

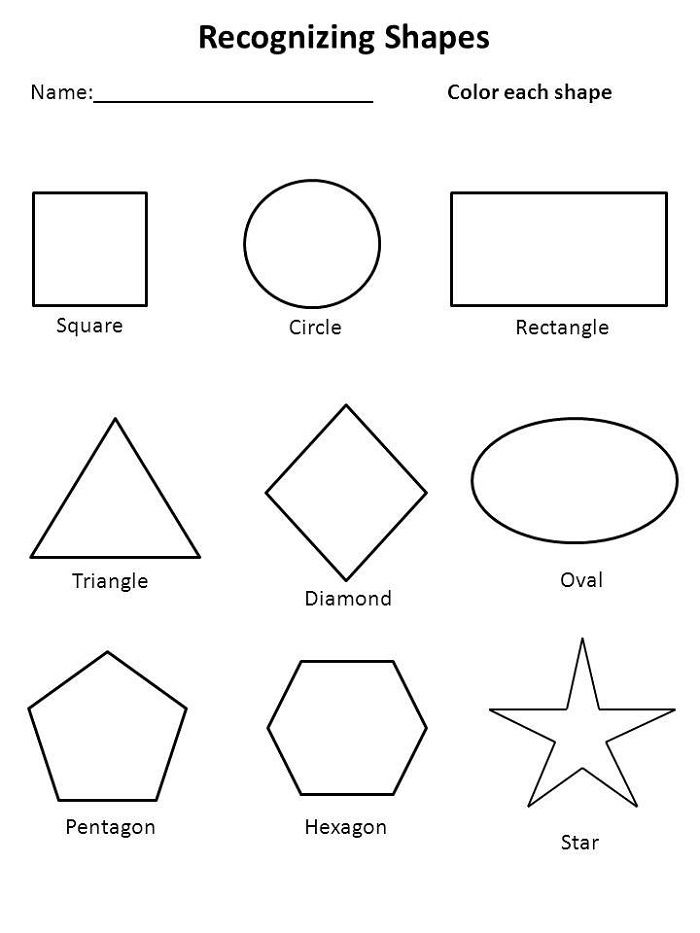

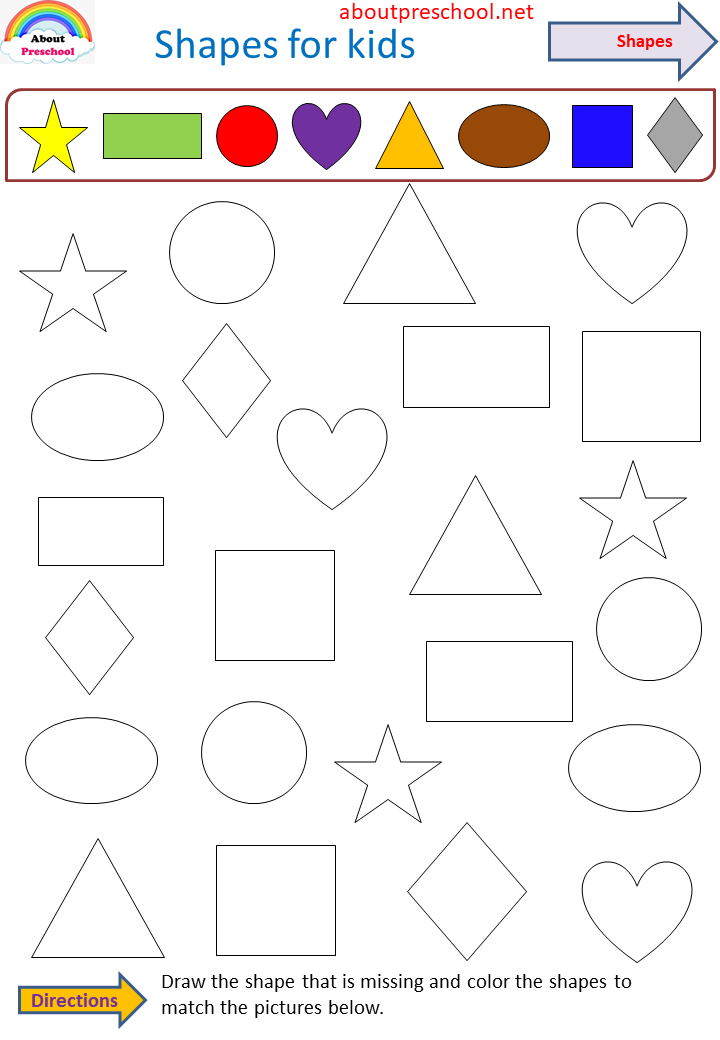

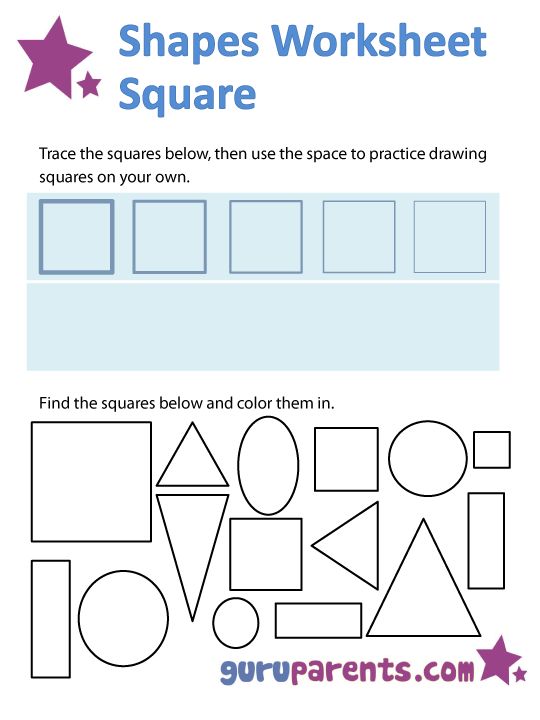

Coloring and TracingColoring books and shape workbooks are a wonderful way to work on shapes. Plus you get work on sitting still and focus skills.

Plus you get work on sitting still and focus skills.

Coloring is a childhood staple that is full of benefits. (Learn all about the benefits of coloring here!)

While your child is coloring, talk about the shapes on the page just as you would talk about the colors they are using. Tracing books provide additional writing practice that will come in handy when they are older.

Play-Doh Shapes

This is one of my favorite ways to work shapes. Sensory activities are stepping-stones for STEM skills in life, plus they help children really engage in what they are learning.

I created some shape printables for my children. You can laminate them and have your child fill the shapes in with Play-Doh. (Or slime, if you have a slime loving child.)

I don’t have a laminator, as much as I want one. So instead of that I purchased a few clear plastic sleeves used for binders and put the printables in those.

Easy to put together and easy to clean up. Head to the bottom of this post to learn how to get these for free to use with your children!

Head to the bottom of this post to learn how to get these for free to use with your children!

A great shape activity you can use as a busy bag activity is shape sticks!

Learn how to make them all here: Shape sticks for Preschool and Toddlers

The short version is to group sticks to make shapes and write the number of sticks needed on each group. So write 3 on three sticks for a triangle, etc. This is a great way to build independent play skills while practicing shapes!

Shapes EverywhereShapes are another one of those seemingly simple topics that have big implications for children. And adults.

Think of all the symbols and signs we can recognize just by the shape, even without words. Octagons are stop signs. An upside down triangle is a warning. Hearts mean love and stars are usually a good thing.

Shapes are such an important first step towards literacy and math skills. Things like shapes seem so simple and basic, yet they are teaching our children more than we can imagine.

You can get these coloring pages and Play-Doh mats for your kids! These are available for download in my free printables section. You can gain access to all the free resources by signing up for the Team Cartwright mailing list. Once you sign up you will get an email with the printables password. This library contains all kinds of learning aids. The color by number pages, train learning activities, and my Lego coding worksheets. It also unlocks my twin tracking worksheets! Signing up also adds you to my email list, which you can, of course, unsubscribe from at any time.

I want the Freebies!

Sign me up to join the team! This gives me access to the free printables and adds me to the Team Cartwright mailing list.

Bonus Shape Practice Printables

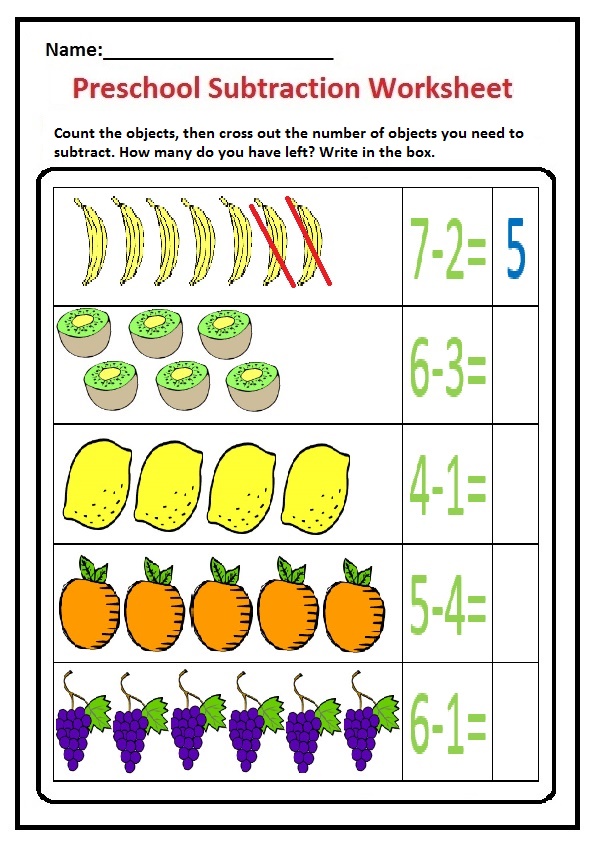

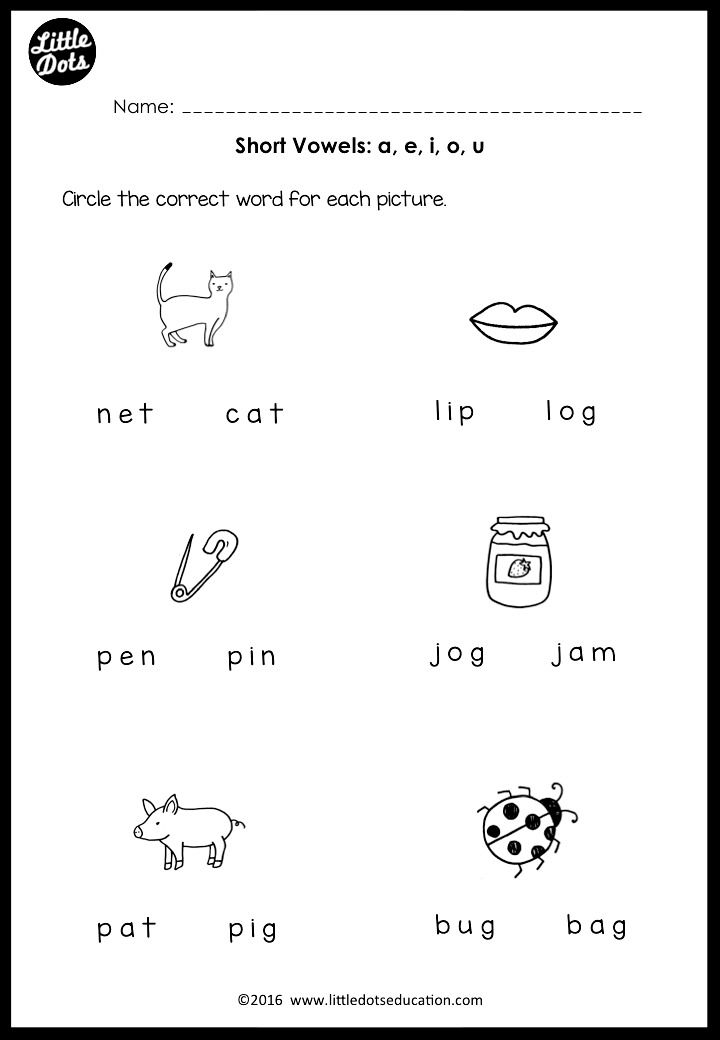

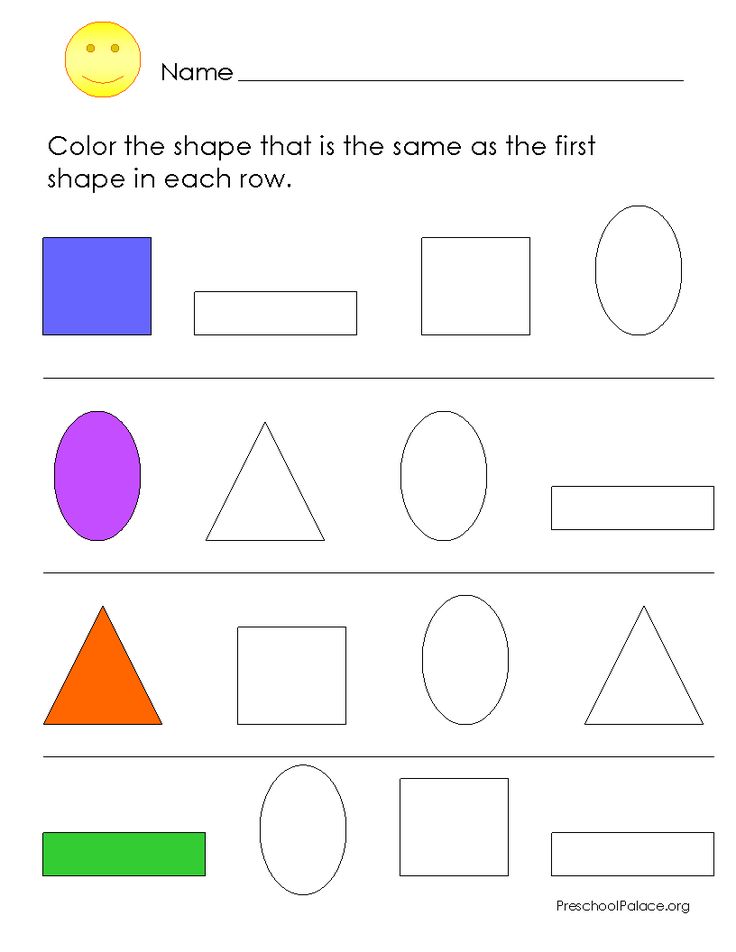

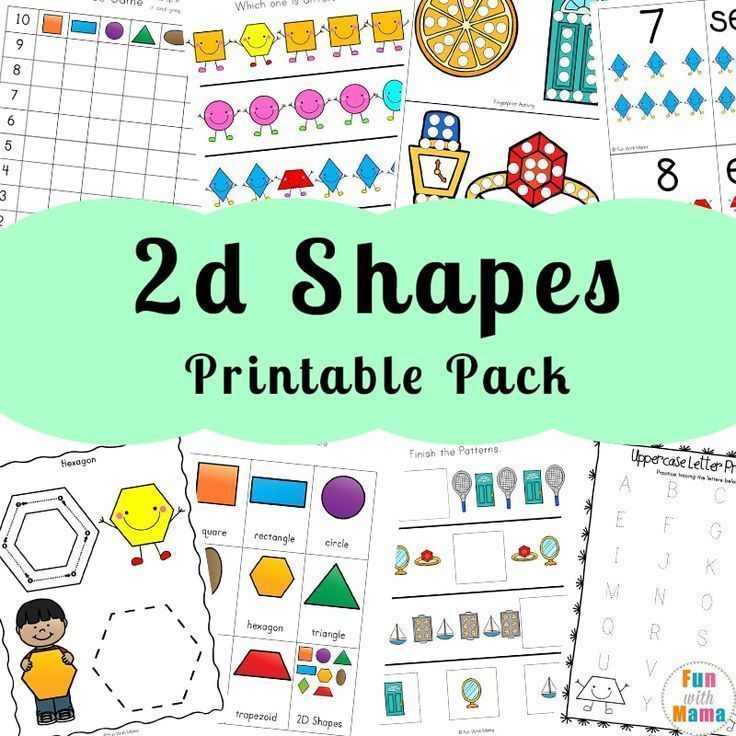

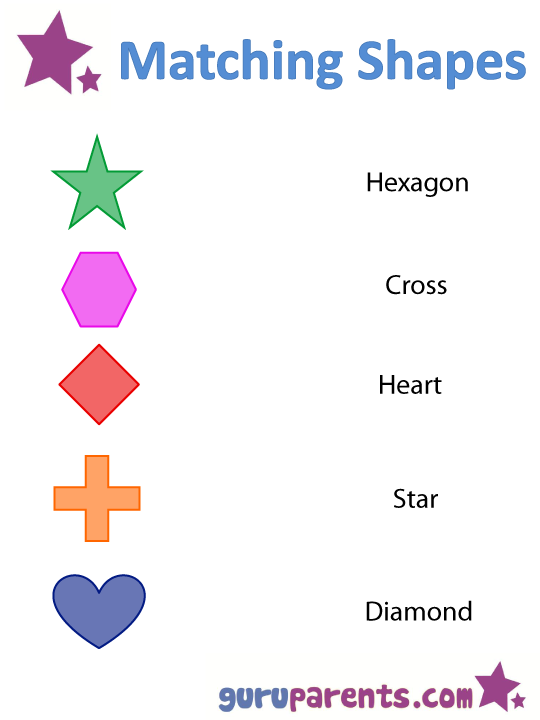

Hands-on activities are amazing for learning about shapes. But worksheets can be helpful as well. These three free worksheets are great for shape practice.

But worksheets can be helpful as well. These three free worksheets are great for shape practice.

Your child can practice tracing the shapes and then draw them in with the dots. Finally, practice scissor skills while you cut and paste the pictures with the proper shape. Easy and fun! (And don’t forget to let them color their shapes too.)

Get the worksheets!

Find your next fun activity! Where would you like to start?

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

25 Creative Activities and Ideas For Learning Shapes

Learning shapes is one of the earliest concepts we teach kids. This readies them for geometry in the years ahead, but it’s also an important skill for learning how to write and draw. We’ve rounded up our favorite activities for learning shapes, both 2-D and 3-D. They all work well in the classroom or at home.

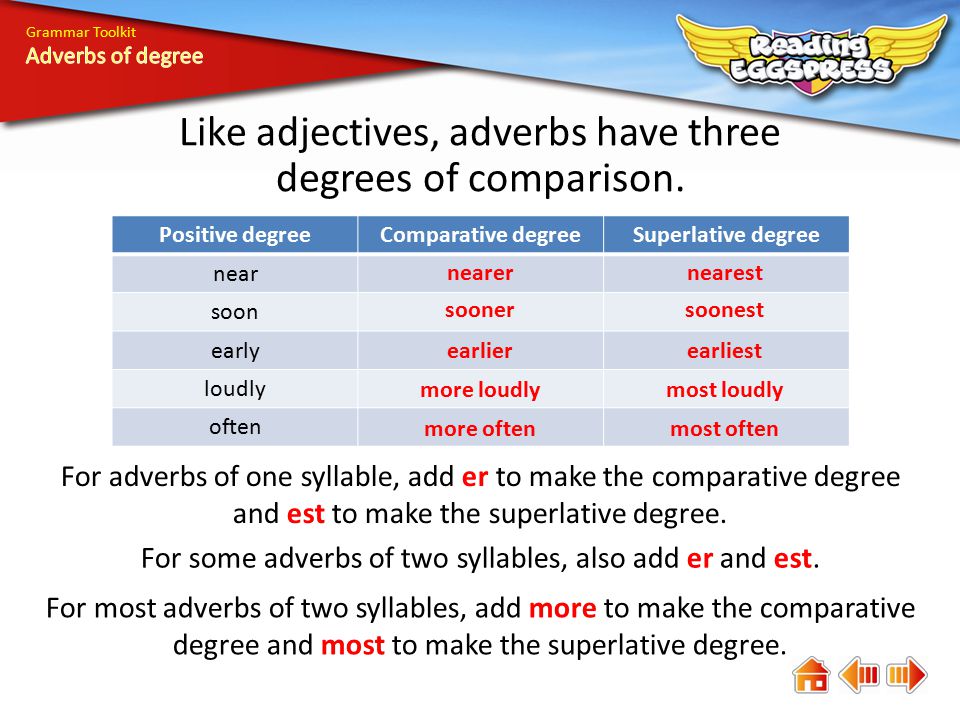

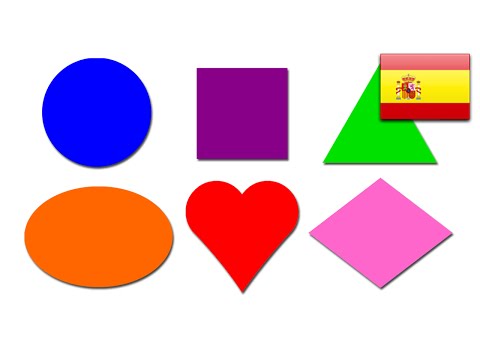

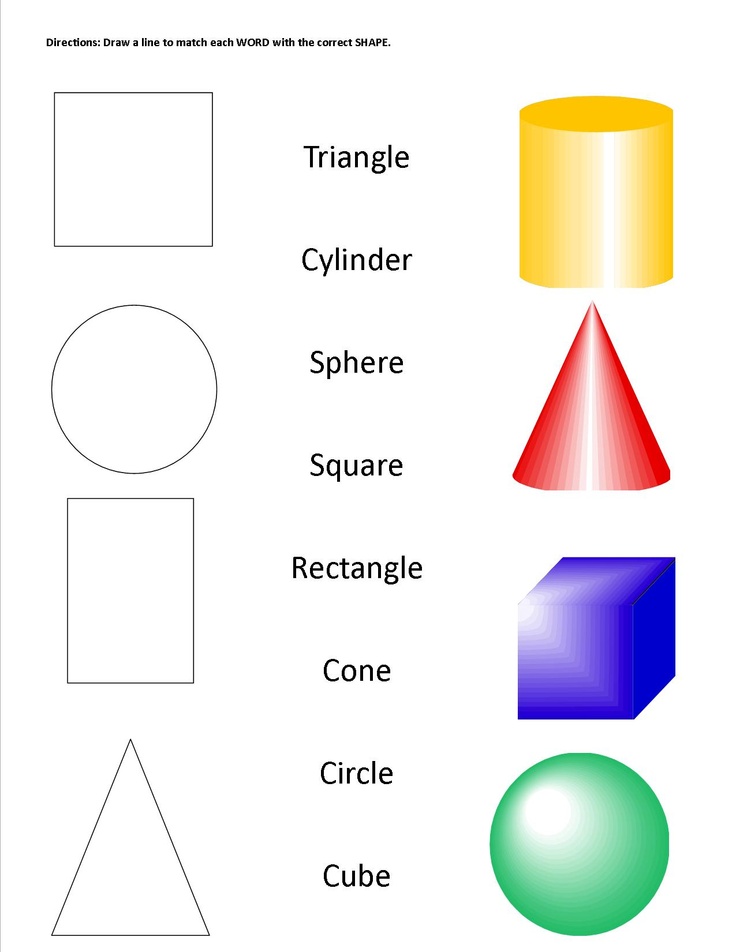

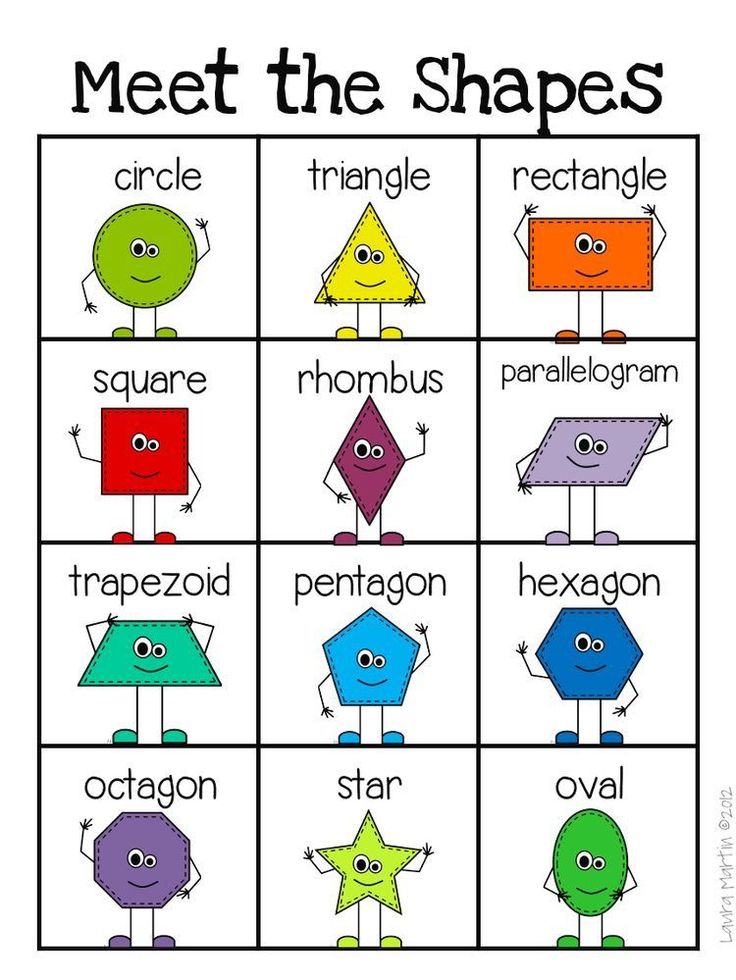

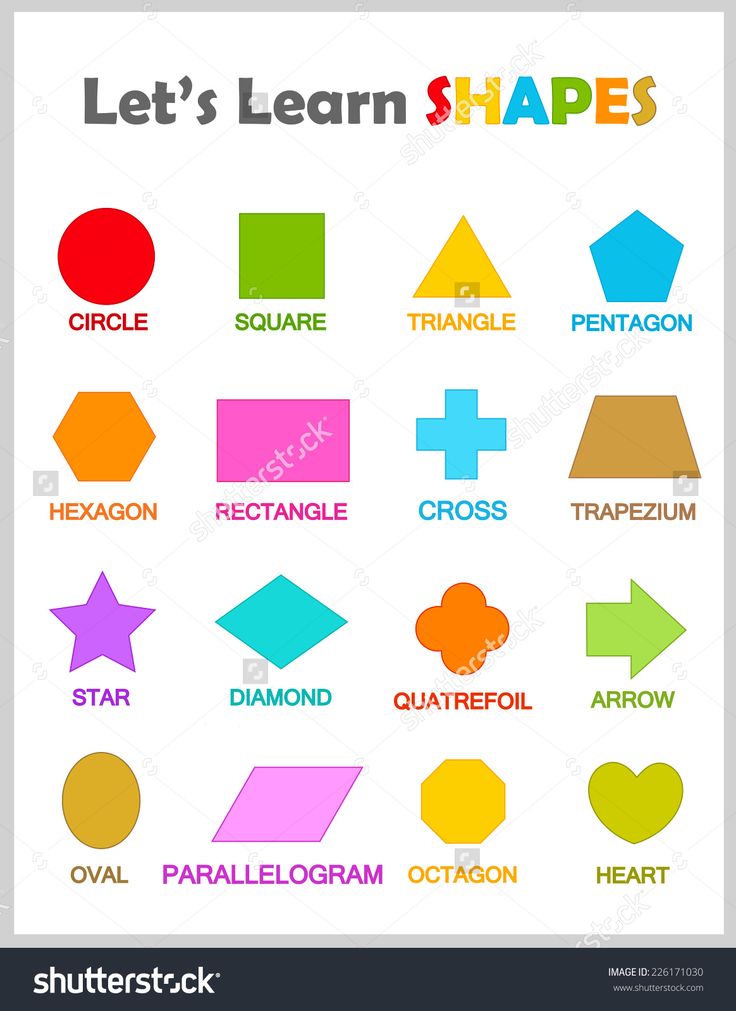

1. Start with an anchor chart

Colorful anchor charts like these are terrific reference tools for kids learning shapes. Have kids help you come up with examples for each one.

Learn more: A Spoonful of Learning/Kindergarten Kindergarten

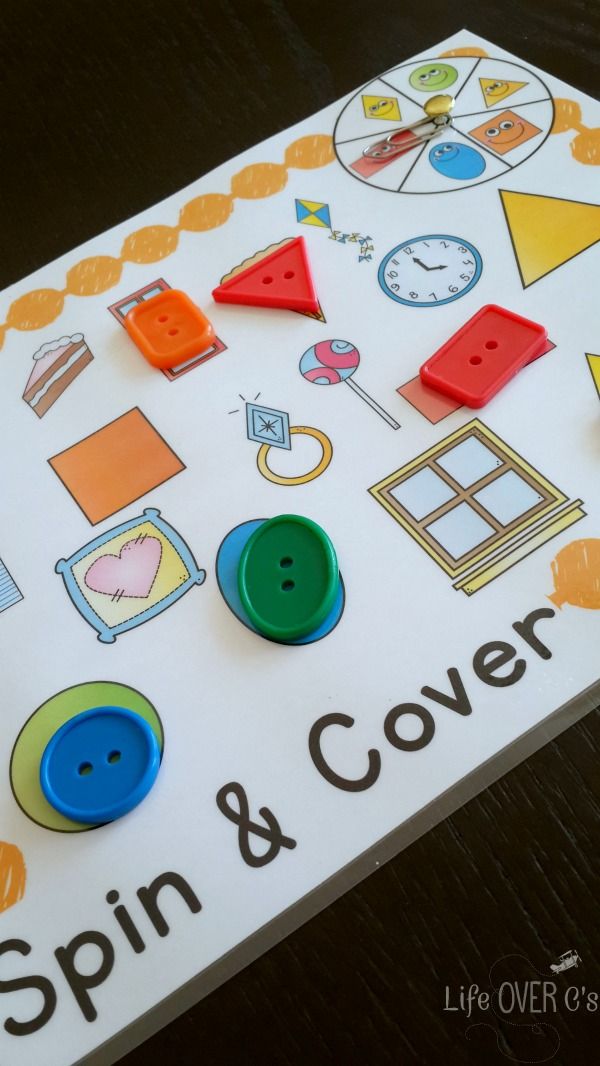

2. Sort items by shape

Collect items from around the classroom or house, then sort them by their shapes. This is a fun way for kids to realize that the world around them is full of circles, squares, triangles, and more.

Learn more: Busy Toddler/Shape-Sorting

3. Snack on some shapes

Everyone loves a learning activity you can eat! Some food items are already the perfect shape; for others, you’ll have to get a little creative.

Learn more: Chieu Anh Urban

4. Print with shape blocks

Grab your shape blocks and some washable paint, then stamp shapes to form a design or picture.

Learn more: Pocket of Preschool

5.

Go on a shape hunt

Go on a shape huntThese “magnifying glasses” make an adventure of learning shapes! Tip: Laminate them for long-term use.

Learn more: Nurture Store UK

6. Hop along a shape maze

Use sidewalk chalk to lay out a shape maze on the playground or driveway. Choose a shape and hop from one to the next, or call out a different shape for every jump!

Learn more: Creative Family Fun

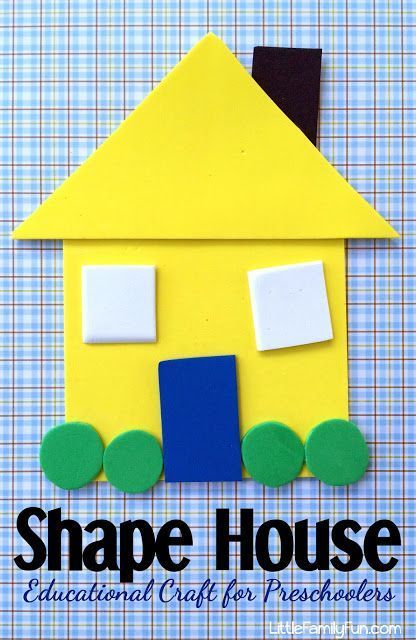

7. Assemble a truck from shapes

Cut out a variety of shapes (excellent scissors skills practice!), then assemble a series of trucks and other vehicles.

Learn more: Little Family Fun

8. Stretch out shapes on geoboards

Teachers and kids love geoboards, and they’re a great tool for learning shapes. Give students example cards to follow, or ask them to figure out the method on their own.

Learn more: Mrs. Jones’ Creation Station

9. Drive on shaped roads

Use these free printable road mats to work on shapes. Bonus: Make your own road shapes from sentence strips!

Bonus: Make your own road shapes from sentence strips!

Learn more: PK Preschool Mom

10. Find shapes in nature

Take your shape hunt outside and look for circles, rectangles, and more in nature. For another fun activity, gather items and use them to make shapes too.

Learn more: Nurture Store UK

11. Put together craft stick shapes

Add Velcro dots to the ends of wood craft sticks for quick and easy math toys. Write the names of each shape on the sticks for a self-correcting center activity.

Learn more: Surviving a Teacher’s Salary

12. Blow 3-D shape bubbles

This is a STEM activity that’s sure to fascinate everyone. Make 3-D shapes from straws and pipe cleaners, then dip them in a bubble solution to create tensile bubbles. So cool!

Learn more: Babble Dabble Do

13. Prep a shape pizza

Cover a paper plate “pizza” with lots of shape toppings, then count the number of each. Simple, but lots of fun and very effective.

Simple, but lots of fun and very effective.

Learn more: Mrs. Thompson’s Treasures

14. Construct shapes from toothpicks and Play-Doh

This is an excellent STEM challenge: how many shapes can you make using toothpicks and Play-Doh? Marshmallows work well for this activity too.

Learn more: Childhood 101

15. Outline shapes with stickers

Kids adore stickers, so they’ll enjoy filling in the outlines of the shapes they’re learning. They won’t realize it, but this gives them fine motor skills practice too!

Learn more: Busy Toddler/Sticker Shapes

16. Lace shapes

Lacing cards have long been a classic, but we really like this version that uses drinking straws. Just cut them into pieces and glue them along the edges of the cards.

Learn more: Planning Playtime

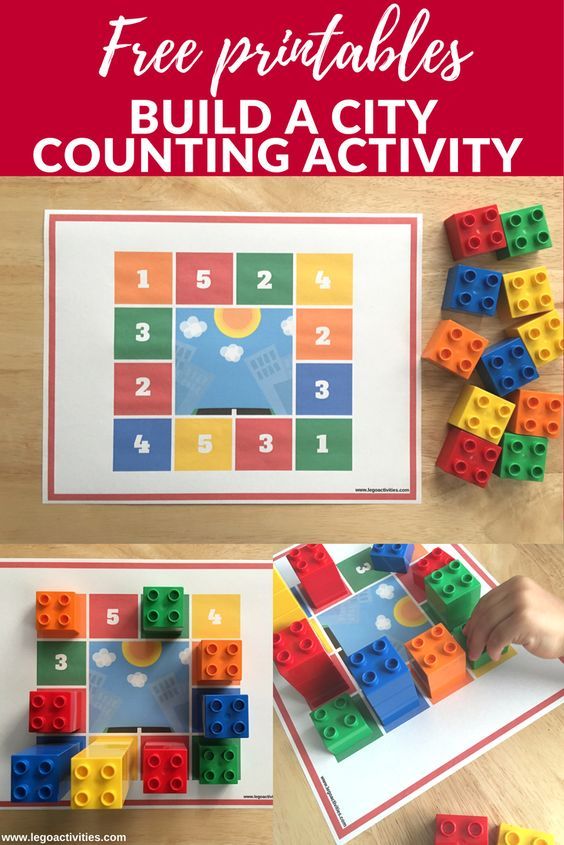

17. Make shapes with LEGO bricks

LEGO math is always a winner! This activity also makes a good STEM challenge. Can your students figure out how to make a circle from straight-sided blocks?

Can your students figure out how to make a circle from straight-sided blocks?

Learn more: Pocket of Preschool

18. Categorize shapes by their attributes

Work on geometry terms like “sides” and “vertices” when you sort shapes using these attributes. Start by placing shapes into paper bags and asking students questions like, “The shape in this bag has 4 sides. What could it be?”

Learn more: Susan Jones Teaching

19. Count and graph shapes

These free printable worksheets challenge kids to identify shapes, then count and graph them. Lots of math skills, all in one!

Learn more: Playdough to Plato

20. Create a shape monster

Add arms, legs, and faces to create cheery (or scary) shape monsters! These make for a fun classroom display.

Learn more: Fantastic Fun and Learning

21. Sift through rice for shapes

Sure, kids can identify their shapes by sight, but what about by touch? Bury blocks in a bowl of rice or sand, then have kids dig them out and guess the shape without seeing them first.

Learn more: Fun With Mama

22. Craft an ice cream cone

Ice cream cones are made up of several shapes. Encourage kids to see how many different ways they can make a sphere of “ice cream.”

Learn more: Extremely Good Parenting

23. Ask “What does the shape say?”

If you don’t mind the risk of getting that song stuck in your kids’ heads, this is such a neat way to combine writing and math.

Learn more: Around the Kampfire

24. Piece together shape puzzles

Use wood craft sticks to make simple puzzles for kids who are learning their shapes. These are inexpensive enough that you can make full sets for each of your students.

Learn more: Toddler at Play

25. Feed a shape monster

Turn paper bags into shape-eating monsters, then let kids fill their hungry bellies!

Learn more: Teach Pre-K

From teaching shapes to long division and everything in between, these are the 25 Must-Have Elementary Classroom Math Supplies You Can Count On.

Plus, 22 Active Math Games and Activities For Kids Who Love to Move.

"Art helps a person to clarify their own emotions" • Arzamas

You have Javascript disabled. Please change your browser settings.

- History

- Art

- Literature

- Anthropology

I'm lucky!

Anthropology, Art

On February 14, the exhibition "Playing with Masterpieces: from Henri Matisse to Marina Abramovich" opens at the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center. Exhibition curator Alexei Munipov talked with Andrey Zorin about what the history of emotions is and whether one can learn to feel art

— What does modern science think about emotions?

- I will not undertake to speak on behalf of all modern science, especially since it thinks differently. Let's say, when I became interested in the topic of emotions, I was not very interested in neurophysiology, but meanwhile, today it is neuroscientists who set the tone for the study of emotions. My research is related to the cultural-historical approach. As a historian, I am interested in the impact of the cultural environment, the history of the formation of cultural stereotypes and norms in the field of feelings. How should one perceive certain events, how do you understand and evaluate them, what types of reactions are expected to them. We are talking about the cultural mechanics of the formation of a person's emotional experience, about the norms that regulate emotions within certain groups of people that Barbara Rosenwein Barbara Rosenwein (b. 1945) is a medieval historian, professor at Loyola Catholic University (Chicago), a specialist in the history of emotions. called "emotional communities".

Let's say, when I became interested in the topic of emotions, I was not very interested in neurophysiology, but meanwhile, today it is neuroscientists who set the tone for the study of emotions. My research is related to the cultural-historical approach. As a historian, I am interested in the impact of the cultural environment, the history of the formation of cultural stereotypes and norms in the field of feelings. How should one perceive certain events, how do you understand and evaluate them, what types of reactions are expected to them. We are talking about the cultural mechanics of the formation of a person's emotional experience, about the norms that regulate emotions within certain groups of people that Barbara Rosenwein Barbara Rosenwein (b. 1945) is a medieval historian, professor at Loyola Catholic University (Chicago), a specialist in the history of emotions. called "emotional communities".

But there are other approaches to the emotional world of a person. Now we know much more about the physiology of the brain, very interesting research is taking place at the intersection of humanitarian and neurophysiological approaches. In general, the study of emotions is a rapidly developing field, it is only 30-40 years old. The entire behavioral economics is focused on the study of emotional, subconscious human behavior. And not only it, but a lot of different disciplines. There was even such a term as "emotional turn", referring to the study of the inner world, emotions, experiences.

Now we know much more about the physiology of the brain, very interesting research is taking place at the intersection of humanitarian and neurophysiological approaches. In general, the study of emotions is a rapidly developing field, it is only 30-40 years old. The entire behavioral economics is focused on the study of emotional, subconscious human behavior. And not only it, but a lot of different disciplines. There was even such a term as "emotional turn", referring to the study of the inner world, emotions, experiences.

- Science is so actively engaged in this, because the topic of emotions seems to us as a society more valuable than before?

- Partly yes, and this is due to the revision of the idea that a person is a rational being: he makes deliberate decisions, guided by rational interests. Moreover, this turn took place precisely in the scientific environment, the inhabitants never considered that a person is rationally arranged. And they were always interested in emotions, it was simply assumed that this topic was not for science. Writers, directors, artists have always turned to the emotional world of man, but historians were not allowed to make assumptions about the emotions of people of the past, this was considered tabloid. A novelist can, but a historian can't. The man died long ago - how do you know how he felt? But the techniques of analysis are being improved, and now we are cautious, with a due degree of skepticism, but we can say something about this.

Writers, directors, artists have always turned to the emotional world of man, but historians were not allowed to make assumptions about the emotions of people of the past, this was considered tabloid. A novelist can, but a historian can't. The man died long ago - how do you know how he felt? But the techniques of analysis are being improved, and now we are cautious, with a due degree of skepticism, but we can say something about this.

- There is a popular theory that people at all times and in all cultures experience the same basic emotions. Of these, six or seven are usually distinguished: fear, joy, sadness, anger, surprise, disgust, sometimes even contempt. What do you think about this? Basic human emotions. Engraving from the book of Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon "General and private natural history". 1749 Art.com

- There is a radical way to say this - and a neat one. To put it bluntly, the theory of basic emotions, which was formulated and promoted by the American psychologist Paul Ekman, has nothing to do with serious science. I can carefully note that I belong to a different scientific school, which does not adhere to the point of view about the existence of basic emotions. From my point of view, there are no basic emotions. Every real human emotion is an infinitely complex combination.

I can carefully note that I belong to a different scientific school, which does not adhere to the point of view about the existence of basic emotions. From my point of view, there are no basic emotions. Every real human emotion is an infinitely complex combination.

Of course, you always want to reduce the complex to the simple, decompose it into elements, highlight the components. This is a normal analytical procedure. There is nothing wrong with trying to break down any emotional reaction or experience into its components: a little delight, combined with embarrassment or surprise. The bad begins where we assume that the basic emotions are indeed found in nature: pure surprise, pure delight, or pure fear.

- As far as I understand, two scientific schools have formed in the dispute around human emotions: one argues that emotions are universal, because they are caused by human physiology, and the other that they are shaped by culture and therefore they are different in each society.

Is the theory about basic emotions what universalists stand for?

Is the theory about basic emotions what universalists stand for? - That's a different question. Talking about whether emotions are universal or culturally determined is not the same as talking about whether emotions are reducible to basics. The answer to the second question is very simple: no, they are not reducible. And in the debate about what shapes our emotions, each school has its own strong arguments.

I think we are dealing with a complex combination of the universal and the socially constructive. Well, do we somehow understand another person, despite cultural and social barriers? These barriers always exist and between everyone, not only when we speak of a resident of another country or a person from the 14th century. And some reactions that are universal for all probably exist. Of course, our understanding of the other is always incomplete and incorrect, but if we dealt with social constructions in their pure form, then it would be impossible at all.

Therefore, the suggestion that there is an element of universality in human emotions does not strike me as absurd. The question is which is more important. An active study of historical and cultural emotions began with anthropology: researchers found that the people they studied not only think, but also feel differently. And it was a completely unexpected discovery!

It was the supporters of historical and cultural anthropology who wrote back in the 1970s that part of the universal nature of man is his incompleteness. That is, a person is not born ready, he is completed in the process, and it is the completion of construction that is part of his biological nature, which distinguishes him from any other creatures. We receive a system of norms, taboos and prescriptions from the outside, from culture.

Of all living beings, humans are the least determined by genetic factors. Due to the cultural mechanism of differentiation, we are very different. And it was the ability to assimilate culture, to be guided by it, that provided man with his amazing bioevolutionary triumph. Once upon a time, a handful of naked, insignificant, defenseless and poorly adapted creatures roamed the East Asian desert, and now we are the masters of at least the globe. There are more than 7 billion of us, and we decide the fate of all other living beings on the planet.

It turned out that culture is the most important of the possible mechanisms that provide man as a biological being with dominance on Earth. Therefore, I do not see an insurmountable contradiction between the universal and social constructivist approaches. There is no discussion here between science and charlatanism, this is a discussion between schools that place emphasis in different ways.

— Perhaps the basic emotion theory is so popular because it resonates with the popular notion that people don't change? We can understand Shakespeare and Ovid, because people have always rejoiced, fell in love and fought - in general, they felt the same as now. Henry Fuseli.

Lady Macbeth takes the daggers. Around 1812 Tate

Lady Macbeth takes the daggers. Around 1812 Tate - If a person is thrown out of an airplane, then he will be scared. There is almost no cultural component in this fear - pure physiology. Everyone will be scared, even the cat. There are instincts - reproduction, saturation, avoidance of death. They unite us with our animal ancestors, but the essence of man is that these absolute universals take real form only in a cultural context.

Take any sphere. Satisfying hunger? The sphere of food has always been regulated and is regulated by systems of taboos, norms and regulations. Satisfaction of sexual needs? Let's not even start. Fear of death? Many cultures have developed relatively effective mechanisms to mitigate or block it.

We do not have an analytical scalpel with which to separate in a person what is inherent in nature and what is invented by culture. Because culture is part of human nature. Culture in a broad sense is a mechanism of non-genetic transmission of norms, taboos, prescriptions, rules from generation to generation. And it is impossible to separate it from the natural.

And it is impossible to separate it from the natural.

This is remarkably demonstrated by researchers who study humans in extreme situations. Read Lydia Ginzburg's book about besieged Leningrad: people are on the verge of survival, starvation is near, but they stubbornly write scientific papers and worry about how they are perceived by their colleagues. That is, the mechanism of self-affirmation continues to work even in this situation. Moreover, such a well-known cultural phenomenon as a death fast indicates that even the basic universal instinct “to eat so as not to die” is not compulsory for a person. A person may choose to starve himself to death.

— Is the desire to continue working during the blockade precisely self-affirmation, and not a way of psychological protection in an unbearable situation?

— Self-affirmation is a way of psychological protection. The desire to be recognized and appreciated by others. Ginzburg has a striking aphorism: a person, of course, wants to be better than others, but this is not enough for him, the main thing is to be no worse than others. It's amazingly accurate and very deep. The mechanism of self-realization in the environment, the feeling of being part of the human society are the most important things that to a large extent are able to block even such a fundamental thing as hunger. And it's not just self-defense in an unbearable situation, because then we might assume that as soon as the unbearable situation ends, these mechanisms will weaken. But nothing of the kind happens.

It's amazingly accurate and very deep. The mechanism of self-realization in the environment, the feeling of being part of the human society are the most important things that to a large extent are able to block even such a fundamental thing as hunger. And it's not just self-defense in an unbearable situation, because then we might assume that as soon as the unbearable situation ends, these mechanisms will weaken. But nothing of the kind happens.

- Can we say that our emotional spectrum is steadily expanding over time? Boredom is a relatively new emotion, isn't it?

— My colleague Vera Sergeevna Dubina once dealt with boredom, this is a very interesting topic. For centuries, man has been completely absorbed in survival. Finally, people defeated nature relatively late, 200-300 years ago, when it became clear that natural disasters would not destroy humanity (more precisely, when such an illusion arose and became stronger). The idea was immediately born that nature should be protected, protected and loved. Rousseauism arises, talk about a return to nature, and this is an unmistakable symptom that nature has ceased to be an enemy, it has been defeated. And then you can idealize it, admire it, condemn the separation from it, and so on.

Rousseauism arises, talk about a return to nature, and this is an unmistakable symptom that nature has ceased to be an enemy, it has been defeated. And then you can idealize it, admire it, condemn the separation from it, and so on.

Of course, the love of nature is part of a refined urban civilization. Outside of it, nature is not idealized: everyone knows that it is dangerous, insidious, hostile to man, that it must be fought. But at a certain stage in the development of urban civilization, people have a new emotion - love for nature.

It can be assumed that boredom is also a historical emotion, arising when a person is freed from the need to continuously search for ways to survive. Then there is a need to somehow spend time, but boredom is connected precisely with the passage of time: how to kill it, to occupy it. In addition, a person always has an instinct to search for something new, changes, the whole development of science and civilization is based on this. I think boredom is generated by an imbalance between the ordinary and the new, the predominance of the familiar and the lack of the unknown.

- Many languages have specific names for various complex emotions that others do not have, from the Portuguese "saudade" to the Russian "longing". Can we experience an emotion if there is no name for it in our language? Lucas Cranach the Elder. Melancholy. First half of the 16th century Christie's

- This is a famous discussion, there are whole scientific schools studying the linguistic nature of emotions. The answer is more or less clear: yes, of course, a person can feel an emotion, even if it is not called in any way in his language. In addition, even if an emotion is called not by one label word, but by two or three, this does not mean that this emotion is blocked in culture.

But, of course, the presence in the language of a special word indicates that behind the emotion expressed by it there is a certain cultural norm and it is broadcast and dictated in one way or another. The presence of such a word forms expectations, creates a representable visual image, so that this thing is significant, although not unconditionally defining.

On the other hand, two people will not understand a single word in the same way, even native speakers of the same language. And I'm not talking about such complex and dimensionless concepts as love, but about seemingly obvious joy or anxiety. Even speaking in our native language, we always translate the interlocutor into our personal language - what does he mean, but how does he understand it? It is a continuous process of interpreting other people's statements.

— And how does art work from the point of view of the researcher of emotions?

- I started by saying that science began to study emotions quite recently, and art has been working with this topic since its inception. Artists have always known that man is not a rational being. That the appeal to the emotional life of a person is always stronger than to the intellect - to rationally conscious skills and interests. It took science centuries to come to this idea.

Even before I got into emotions, I studied ideology, and I was often asked: why do I say that decisions are made on the basis of political metaphors, because people always proceed from their own interests? Yes, but in order to proceed from interests, you must have a clear idea of \u200b\u200bwhat they are, and this is a deeply irrational thing.

If you are a statesman, then your interest may be to expand the territory of your country, or maybe it is to improve the welfare of its inhabitants or implement some ideas, etc. And someone else's interest - in immediately drinking and falling. Or in saving a lot of money. Each person understands his interest in accordance with his own cultural ideas. In particular, art helps us to realize, understand and feel our interests.

Of course, it exists for more than just that. Any important thing is multifunctional, even from an ordinary glass you can drink water, or you can punch your neighbor in the head with it - what can we say about art. But one of the most important functions of art is that it helps a person to clarify his own emotions. It provides a mirror through which our emotions become clearer to us. We get images of the feelings we experience, we see how they can be experienced, what is regulated and what is not, what is good and what is bad. We can evaluate ourselves and see our emotional world from the outside. And for this you need to look into the emotional world of another person, in which we are looking for reflections, parallels to ourselves. People who know how to go into their own world to a great depth get the opportunity to say something to another about his world. Due to this, the most important artistic effect arises - identifying oneself with a character, hero, author, projecting oneself into the world of a work of art, allowing one to perceive certain emotions that are contained there.

And for this you need to look into the emotional world of another person, in which we are looking for reflections, parallels to ourselves. People who know how to go into their own world to a great depth get the opportunity to say something to another about his world. Due to this, the most important artistic effect arises - identifying oneself with a character, hero, author, projecting oneself into the world of a work of art, allowing one to perceive certain emotions that are contained there.

— If we perceive art as a language through which we are taught to feel and understand ourselves, then it is obvious that this language should be understood by the viewer. But contemporary art seems to many to be hermetic, completely incomprehensible language. How does it work in this case?

- First, of course, contemporary art works for a certain circle of those who understand it. It leaves behind a significant part of those who will not perceive it, and creates an institutional layer of interpreters. In addition, contemporary art, starting with modernism, has a romantic idea that the creator goes ahead of the consumer: what today is not clear to anyone but an artistic genius, tomorrow becomes clear to many, and the day after tomorrow - to everyone. And if you look at how much Van Gogh and other unrecognized art used to cost and how much it costs now, it turns out that in the end these social mechanisms worked.

It leaves behind a significant part of those who will not perceive it, and creates an institutional layer of interpreters. In addition, contemporary art, starting with modernism, has a romantic idea that the creator goes ahead of the consumer: what today is not clear to anyone but an artistic genius, tomorrow becomes clear to many, and the day after tomorrow - to everyone. And if you look at how much Van Gogh and other unrecognized art used to cost and how much it costs now, it turns out that in the end these social mechanisms worked.

Now we see another type of art. Modern artists often strive to make their art as clear as possible. Graffiti, actionism, instant, quickly readable art - all this is a reaction to the modernist cult of artistic genius, to the notion of a genius-medium, extracting from the depths of the subconscious meanings that are incomprehensible today, but someday will become the property of mankind.

— Our exhibition is built on the assumption that modernist art is not necessarily understood.

It can be felt, because it primarily refers not to the intellect, but to the emotional sphere, and many modernists, from Picasso and Matisse to Rothko and Pollock, have said this directly.

It can be felt, because it primarily refers not to the intellect, but to the emotional sphere, and many modernists, from Picasso and Matisse to Rothko and Pollock, have said this directly. - I am not an art critic, but for me this hypothesis is quite convincing. Modernist art is characterized by the rejection of narrative, figurativeness. Instead, it is proposed to appeal to the deep emotional layer of a person, which does not require rationalization. Expressionism is all about this, it is a visual expression of the power of feeling that unites the creator and the viewer in a single emotional field. So I would agree with your interpretation, unless we are trying to reduce this emotional charge to a well-understood formula, to the notorious basic emotion: this picture expresses fear, this one expresses anxiety, this one expresses delight.

We are always dealing with a very complex emotion that can be experienced, read into it. Of course, a person cannot experience someone else's emotion. But he can imagine the emotional state that this work gave rise to, that is, go from the text to the reflected emotion. Of course, this will be your personal emotion, since the author's emotion could be completely different, but due to these mechanisms of translation and mutual understanding, you will be able to put yourself in the place of the author.

But he can imagine the emotional state that this work gave rise to, that is, go from the text to the reflected emotion. Of course, this will be your personal emotion, since the author's emotion could be completely different, but due to these mechanisms of translation and mutual understanding, you will be able to put yourself in the place of the author.

— In the process of working on the exhibition, at some point we tried to sort the works by emotions, that is, to literally collect a hall of joy, sadness, fear... And, of course, we encountered the fact that art does not work like that. There are no paintings that evoke only one bright emotion, it is always a complex spectrum. And for everyone he is his own.

- Art doesn't work that way, of course, because human experience is a constellation of complex experiences. As Tolstoy said, there is not enough ink in the world to describe the impressions of one day. If the proverbial basic emotions really existed, why create new works of art? These basic emotions would have been reflected a hundred times already, and all their combinations too - and it would be possible to close the shop. But each time we are dealing with an absolutely unique alloy. Of course, the author has his own, and the viewer has his own. But the viewer can get into resonance, react to something, feel something stronger, and something weaker.

But each time we are dealing with an absolutely unique alloy. Of course, the author has his own, and the viewer has his own. But the viewer can get into resonance, react to something, feel something stronger, and something weaker.

— If this system of conveying emotions is so complex and unpredictable, how exactly does the artist translate what he wants to convey?

— There is art, and there is a lot of it, which is designed to replicate ready-made emotional models. It does not produce something new, but works with ready-made stamps that are already in the culture. This is not just epigonism, it is a necessary component of the artistic process: people have always had and will need such models. Techniques, emotional prompts, ready-made sensual repertoire. It is important for people to live in such an environment, to know that your emotional patterns are sanctioned, recognized, reproducible. Therefore, everyone loves Hollywood films so much, which broadcast a fairly standard emotional set.

But at some point you feel that this is not enough, that it does not convey the full complexity of your emotional experience, that it is more complex, more difficult, more incomprehensible and does not fit into common patterns at all. Hence the need arises for something absolutely specific, unique, new, because only in someone else's uniqueness can you recognize your own uniqueness. Your own unique problems and experiences.

- You are studying how emotional patterns are conveyed in literature. And there are clear mechanisms for this - the hero, the plot, the author's explanations. And how does this system work in art and, in particular, in painting?

- Good question. I am not an art historian and really analyze only narrative tools - stories, plots. It is obvious, however, that in a huge number of paintings there is also an easily understandable plot. How does, say, a historical canvas work? It selects the main moments from the story and broadcasts to the viewer how to react to them correctly. This method has advantages and disadvantages. The advantage is that you immediately get a visual image - this is more than what the text has to offer. And the downside is that the presence of a visual image blocks or at least limits the mechanisms of implantation. In the book it is easy to imagine yourself in the place of the main character, but in the picture he is already drawn, and this is obviously not you.

This method has advantages and disadvantages. The advantage is that you immediately get a visual image - this is more than what the text has to offer. And the downside is that the presence of a visual image blocks or at least limits the mechanisms of implantation. In the book it is easy to imagine yourself in the place of the main character, but in the picture he is already drawn, and this is obviously not you.

And genres without a clear plot can also be analyzed. Take, say, a landscape. It is clear that it is easy to read the meaning into it: eternal rest or Russian space there. Or a portrait - there is also no plot, but the life lived by this person, ideas about his character are read. Art is always suggestive. Even a story told in detail never tells everything: you have to think of something, set it up, reincarnate.

Kazimir Malevich. Three figures in the field. 1928–1930 Collection of Valery Dudakov and Marina Kashuro But the situation when visual art completely breaks away from the narrative series and appeals directly to the emotional layer is a rather new phenomenon. Maybe modernist, abstract art affects us so strongly precisely because it destroys the distance of alienation. I cannot identify myself with the drawn person, because he is not me. Or I can, but with great difficulty. And when you look at an abstract picture, you begin to imagine the creator absent from the canvas or that image of feeling that they are trying to convey to you and which somehow corresponds to your feelings. And there is the possibility of direct contact.

Maybe modernist, abstract art affects us so strongly precisely because it destroys the distance of alienation. I cannot identify myself with the drawn person, because he is not me. Or I can, but with great difficulty. And when you look at an abstract picture, you begin to imagine the creator absent from the canvas or that image of feeling that they are trying to convey to you and which somehow corresponds to your feelings. And there is the possibility of direct contact.

After all, communication is not only linguistic. It is transmitted through visual images, through sound, through gestures. When one person pats another on the shoulder, he tactilely conveys an emotion to him, that is, he seeks to evoke an understandable emotion of another person. And language comes relatively late, it's one of the most complicated ways, there's too much of everything: words have their own meanings that can be manipulated, there are grammatical norms, and so on.

— Even seemingly primitive drawings of cavemen have a very powerful emotional charge.

We don't know anything about these people, but we definitely feel something.

We don't know anything about these people, but we definitely feel something. - Yes, we certainly feel something, it is only important to get rid of the idea that we feel the same way they do. It's impossible!

- But we were brought up in the idea of the universality of art: we can feel the Scandinavian saga or the ancient Chinese landscape, feel what the artist felt.

- No, we can't. But we can imagine the world of this person, then imagine ourselves and try to understand what emotion I could experience if I were in the place of the author. This is a complex and sophisticated procedure, but it happens quickly and almost unconsciously.

Even Adam Smith, who lived in the 18th century, emphasized that our sympathy for another person does not mean that we feel the same as him. Our ability to emotionally imagine ourselves in his place is at the heart of art. But we cannot literally feel what he felt. I myself have spent many years trying to get closer to the world of feelings of long-dead people, so, obviously, I do not consider this activity completely meaningless. But Lotman also noticed that even if in some incredible way we learn everything that a person of another time knew, we still won’t be able to forget everything that he didn’t know, which means we won’t be able to relive his feelings.

I myself have spent many years trying to get closer to the world of feelings of long-dead people, so, obviously, I do not consider this activity completely meaningless. But Lotman also noticed that even if in some incredible way we learn everything that a person of another time knew, we still won’t be able to forget everything that he didn’t know, which means we won’t be able to relive his feelings.

A complete understanding of a foreign world is impossible: we still bring ourselves there. We are immersed in a world invented or described by someone, without ceasing to be ourselves. And if we could completely stop being ourselves and become someone else, the whole procedure would be absolutely useless. What for? What will it give us?

Viktor Pivovarov. Dedication to Pasha. 2004 © Viktor Pivovarov— Is there a difference between how a child perceives contemporary art and an adult? Is it possible to say that a child, for example, looks more directly?

- The meaning of the word "directly" is not very clear to me. A child is just as loaded with cultural clichés as any other person of any age. By the time the child begins to read books and go to museums, mom and dad have already given him a lot of things. No, there is no unmediated feeling.

A child is just as loaded with cultural clichés as any other person of any age. By the time the child begins to read books and go to museums, mom and dad have already given him a lot of things. No, there is no unmediated feeling.

Of course, children and adults have different cultural experiences. The child saw less, does not know so well that all people are different, but on the other hand, he is much more ready to find out, this is part of his bioevolutionary program - to learn, to master new things. The mechanisms are different, I just wouldn't use the word "directly".

- But perhaps they haven't really taught him yet how to react correctly, and therefore it's easier for him?

- They might not be in time, but still he saw some pictures, and the reaction of adults or other children to them, that is, he has some idea. Yes, many adults have not been taught either. I would say that most adults have not been taught how to react to a work of art. It's just that they already often think that they know what art should look like, so they have a feeling of confusion when they see something different. But the child does not yet have this feeling, he does not yet know that portraits, landscapes and still lifes should be shown in the museum, and he should be surprised or indignant if he stumbles upon something else.

It's just that they already often think that they know what art should look like, so they have a feeling of confusion when they see something different. But the child does not yet have this feeling, he does not yet know that portraits, landscapes and still lifes should be shown in the museum, and he should be surprised or indignant if he stumbles upon something else.

By the way, many modern artists are happy to work with this deception of expectations. So you came to the museum, you have to look and not touch anything with your hands. And then again, an installation that you can climb into, ring the bell, twist the handle and hit the board. Of course, children are delighted, but many adults also like it.

Maurizio Cattelan. Untitled. 2000 © Maurizio Cattelan / Private collection / Maurizio Cattelan Archive You might say that this turns an adult into a child, but in fact we are offered a different type of communication with art. Previously, you were taught that in a museum you look only with your eyes, and all your other senses - hearing, smell, touch - have nothing to do with this. It is not so easy to get rid of this knowledge, and, having climbed into a modern installation, you will still look around all the time to see if they are going to arrest you. And the child has fewer of these stereotypes, although they are absorbed instantly. If he was yelled at at least once in the museum, he will be just as afraid of everything.

It is not so easy to get rid of this knowledge, and, having climbed into a modern installation, you will still look around all the time to see if they are going to arrest you. And the child has fewer of these stereotypes, although they are absorbed instantly. If he was yelled at at least once in the museum, he will be just as afraid of everything.

— Is it possible to learn to feel art?

— Of course you can! And this is done in the same way that a person learns everything else - by continuous use. The only thing it takes is motivation.

A person masters his native language unconsciously, because he needs to understand those around him. But learning a foreign language requires will, effort and understanding why you are doing it. Grammar helps, textbooks help, but the best way to learn anything, in particular a language you don't know, is to use it continuously around native speakers.

Art is no exception. To master the language of art, you need to use it continuously: draw something yourself, produce something, live in this environment. If your parents are artists and you are immersed in conversations about art from birth, then you will simply absorb it with mother's milk. This does not mean that you will love it - on the contrary, you can hate it, but it will happen as if by itself. If not, then you need to spend some effort and time - if you think that this will make your life richer. Why else? Life is short, we don't have much time and energy. You can spend them on something else.

If your parents are artists and you are immersed in conversations about art from birth, then you will simply absorb it with mother's milk. This does not mean that you will love it - on the contrary, you can hate it, but it will happen as if by itself. If not, then you need to spend some effort and time - if you think that this will make your life richer. Why else? Life is short, we don't have much time and energy. You can spend them on something else.

— In one of your lectures, you told how your student told you that she didn’t understand the meaning of the word “love”: for her generation, this word is too abstract, there are many different models of relationships, and they just can’t fit in her head in one box labeled "love". That is, we are talking about the fact that "big" emotions are fragmented, become more special, and they may have new names. How to talk about emotions with a modern viewer, if even the most familiar words are no longer clear to him what they mean?

- In the modern world, instead of one "love", many different ones appear, and it is obvious that emotions will be much more diverse, fractional, variable, helping a person understand how to feel correctly in completely different situations - and designed for a much shorter life span. The authors who previously wrote about love proceeded from the idea that love is unchanged in all eras. Of course, we can conduct a historical analysis, figure out who, from what and when this image was assembled: these are very different feelings that were once tied into one bag and written on top: “Love”. The creators of the love we are accustomed to once invented exactly what it was, although they themselves felt themselves not inventors, but pioneers; people who described a continent that has always existed.

The authors who previously wrote about love proceeded from the idea that love is unchanged in all eras. Of course, we can conduct a historical analysis, figure out who, from what and when this image was assembled: these are very different feelings that were once tied into one bag and written on top: “Love”. The creators of the love we are accustomed to once invented exactly what it was, although they themselves felt themselves not inventors, but pioneers; people who described a continent that has always existed.

The creators of the current models understand in advance that these are temporary structures and their use is limited, they are not designed to last for centuries. At the same time, they are much more diverse, there are more of them. It is clear that even a small fraction of them is enough for one human life. But due to the much lesser durability of these models, our emotional repertoire has expanded incredibly.

The emotions themselves change, the attitude towards them changes. Entire blocks of emotions soldered together are destroyed. For example, romantics came up with a model of childhood as an ideal time when you feel the absolute fullness of existence. A person once lost this fullness due to original sin and can approach it only in childhood and later, when he falls in love. And, for example, the most important feeling of nostalgia for culture began precisely as nostalgia for childhood. This whole complex - nostalgia, longing for childhood, growing up, the search for love, the thirst to find the fullness of being in it - is now greatly undermined.

Entire blocks of emotions soldered together are destroyed. For example, romantics came up with a model of childhood as an ideal time when you feel the absolute fullness of existence. A person once lost this fullness due to original sin and can approach it only in childhood and later, when he falls in love. And, for example, the most important feeling of nostalgia for culture began precisely as nostalgia for childhood. This whole complex - nostalgia, longing for childhood, growing up, the search for love, the thirst to find the fullness of being in it - is now greatly undermined.

- What about the emergence of such a term as "emotional intelligence"? Now business coaches are teaching that being smart, that is, having a high IQ, is not enough: you need to feel people, train empathy, otherwise you will not be successful.

- This is what William Reddy, in Navigating the Feelings, called emotional management. Emotional intelligence is the ability to control and properly organize one's own emotional world. How was it considered before? A person controls everything with the intellect and, of course, must pacify his feelings. But real feelings are not controlled by the mind. This is a sign of their authenticity. You are overcome by rage, love or compassion, passion boils up like a wave, and the mind turns off.

How was it considered before? A person controls everything with the intellect and, of course, must pacify his feelings. But real feelings are not controlled by the mind. This is a sign of their authenticity. You are overcome by rage, love or compassion, passion boils up like a wave, and the mind turns off.

Actually, the idea of the need to manage emotions appeared at the same time when people lost faith in the model of rational behavior. The idea of emotional intelligence is based precisely on the rejection of these ideas. It turned out that our behavior is always a complex combination of the conscious and the unconscious. And you can only manage your emotions to a certain extent. This is a complex art, and it is not clear whether one should strive for this at all. Because there is more to lose than to gain. Emotional intelligence in a person may turn out to be more rational, some things are much easier to feel than to understand.

- You are researching the cultural history of emotions.

And how often are you aware of your own emotions?

And how often are you aware of your own emotions? - Good question. I’ll note aside that I don’t plan to deal with this topic anymore, I can’t drill one hole for a long time: when I get to something, I immediately want to turn off the equipment, go to another place and start working there. But studies of this kind help to avoid the naturalization of one's own feelings and experiences, that is, the idea that they are such by nature and there are no others. This is a very important intellectual skill, because without it you cannot understand other people. My scientific activity helped me to some extent. Of course, this problem cannot be completely solved. You still measure people by yourself; to expect that it is possible to get rid of it would be arrogant. But at least a little distance from your loved one is possible.

On the other hand, the study of a person's emotional world always involves an outside perspective. It is impossible to qualitatively explore your own emotional world, just as it is impossible to see your own head without a mirror. But it is possible to ask yourself some questions. After all, I am also subject to various emotional matrices, but where did I get them from? This is an interesting intellectual exercise. I would not print a study on this topic, but you can occupy yourself with it before going to bed or while traveling in transport.

But it is possible to ask yourself some questions. After all, I am also subject to various emotional matrices, but where did I get them from? This is an interesting intellectual exercise. I would not print a study on this topic, but you can occupy yourself with it before going to bed or while traveling in transport.

For example, in conversations with my granddaughters, I often find myself in the role of an old curmudgeon, muttering: “Well, the youth has gone!” And this, of course, is a venerable cultural model with a long history. One of its important components is nostalgia (I was young too), as well as envy, the burden of life experience - well, of course. But God forbid you try to divide this model into basic emotions: it is too complex and at the same time lives for centuries. Everyone knows this beautiful quote: “Today’s youth are accustomed to luxury, have bad manners, scorn authority, have no respect for elders, children argue with adults, greedily swallow food, harass teachers.” As if it was said yesterday - either it's my grandfather talking, or I myself, and this is Socrates. Each next generation says something similar about the previous one, and this should mean that humanity is degrading endlessly. But it seems that this is still not the case. So doing science helps us to be a little more modest and not to absolutize our own experience.

Everyone knows this beautiful quote: “Today’s youth are accustomed to luxury, have bad manners, scorn authority, have no respect for elders, children argue with adults, greedily swallow food, harass teachers.” As if it was said yesterday - either it's my grandfather talking, or I myself, and this is Socrates. Each next generation says something similar about the previous one, and this should mean that humanity is degrading endlessly. But it seems that this is still not the case. So doing science helps us to be a little more modest and not to absolutize our own experience.

— And, probably, to understand not only others, but also yourself?

- To a certain extent. I try to work without anger and passion, but you cannot treat yourself impartially. Well, how is it? Impossible! Obviously, it is much easier to understand another than oneself, precisely because of a certain distance. Especially if this is not your loved one, but some person of the 18th century.

This is also true of one's own culture and history. How to remove yourself from it? You can and should try to understand everyone, but am I ready to dispassionately read books where such an understanding is manifested in relation to fascists or Stalinists? Yes, not very much! I just seethe with rage. That is, a moral assessment overshadows everything else. I'm afraid that it takes a thousand years for the shed blood of the slain to stop standing before our eyes and we begin to understand what happened to us. We can already talk calmly about the Egyptian pyramids, although we know how many lives their construction cost.

Once I was writing a script for a historical documentary, and my friend, the director, called me for a voiceover. It was about Venice of the 18th century, the actor read the text with all the actor's clichés, and the director all the time had to remind: "Calm down, calm down, everyone died a long time ago!" It didn’t help, but I remember the phrase, I often remember it. Recently I even saw a history book with an epigraph: “History is when everyone died.” Professor Zorin. So, until everyone is dead, we can hardly impartially evaluate ourselves and others.

Recently I even saw a history book with an epigraph: “History is when everyone died.” Professor Zorin. So, until everyone is dead, we can hardly impartially evaluate ourselves and others.

At the attraction exhibition for children and adults, you can see the works of Kazimir Malevich and Francis Bacon, Roy Lichtenstein and Viktor Pivovarov, Natalia Goncharova and Marina Abramovich, Alberto Giacometti and Bridget Riley, Anselm Kiefer and Niko Pirosmani. The Masterpiece Game: From Henri Matisse to Marina Abramović will be open from February 14 to April 14.

Images: Thomas Rowlandson. Exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts. Around 1815

Yale Center for British Art

Tags

Interview

Expert

Microstroughs

Daily short materials that we have produced for the past three years

Frescoes of the day

Generatives from Macedonia

Ethnonymous Day

Romanians, Romanian 9000 9000 Tetris (1984)

Archive

History

Tramp, the son of a gypsy artist or a fictional character?

About the projectLecturersTeamLicencePrivacy policyFeedback

Arzamas Radio GooseGooseArzamas stickers

OdnoklassnikiVKYouTubePodcastsTwitterTelegramRSSHistory, literature, art in lectures, cheat sheets, games and expert answers: new knowledge every day

© Arzamas 2022 From Russia? Instructions here

Learning Geometric Shapes: Preschool Games

One of the important aspects of the development of mathematical concepts in preschoolers is the study of the basics of geometry. In the course of acquaintance with geometric shapes, the child acquires new knowledge about the properties of objects (shape) and develops logical thinking. In this article, we will talk about how to help a preschooler remember geometric shapes, how to properly organize games for teaching geometry, and what materials and aids can be used to develop a child’s mathematical abilities.

In the course of acquaintance with geometric shapes, the child acquires new knowledge about the properties of objects (shape) and develops logical thinking. In this article, we will talk about how to help a preschooler remember geometric shapes, how to properly organize games for teaching geometry, and what materials and aids can be used to develop a child’s mathematical abilities.

At what age can one start learning geometric shapes?

Many parents are wondering if young children need to get acquainted with geometric shapes. Experts believe that it is optimal to start classes in a playful, relaxed form from the age of 1.5. Until this age, it is appropriate to pronounce to the child the names of the shapes of objects that the baby meets in real life (for example, “round plate”, “square table”).

Introducing the child to geometric shapes, be guided by his reaction. If your baby started to show interest in them at an early age (by playing with the sorter or looking at pictures), encourage his curiosity.

At the age of 2, the baby should be able to distinguish between:

- Circle;

- Square;

- Triangle.

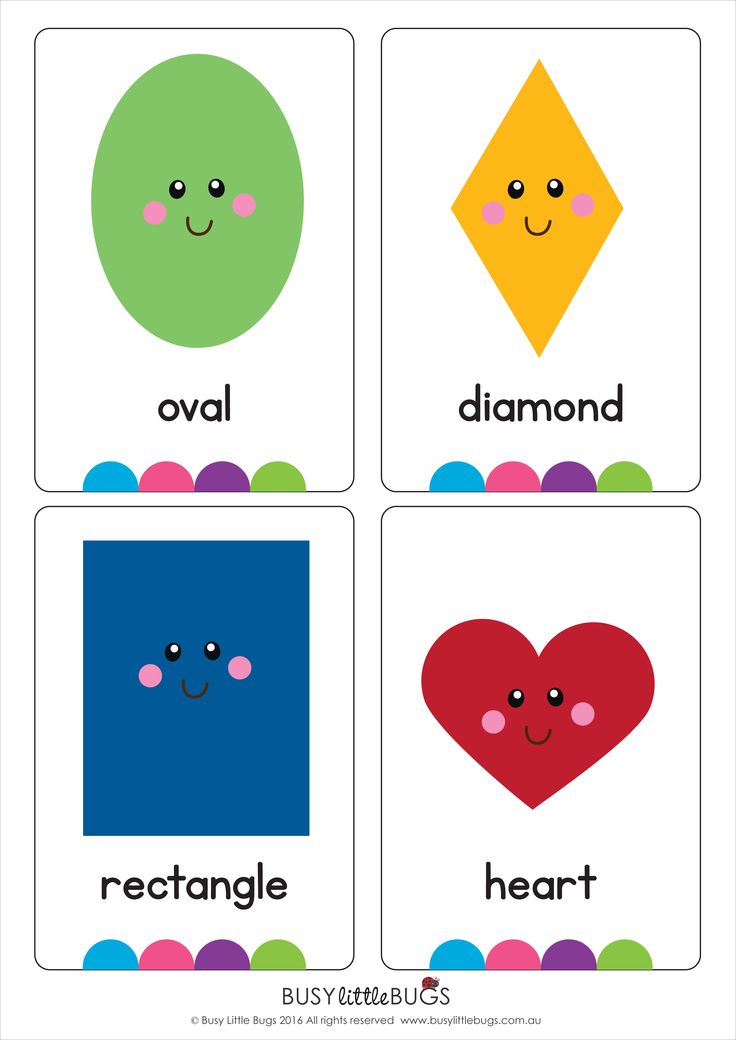

By the age of 3 you can add:

- Oval;

- Rhombus;

- Rectangle.

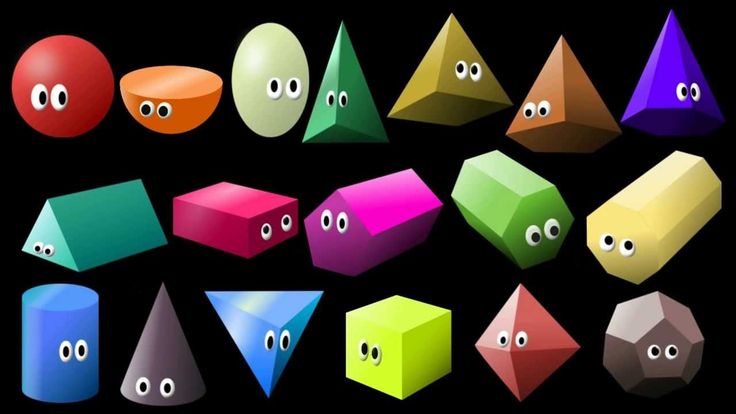

At an older age, a child can memorize such shapes as a trapezoid, a pentagon, a hexagon, a star, a semicircle. Also, children visiting the Constellation Montessori Center get acquainted with geometric bodies with interest.

How to help a child remember geometric shapes?

Teaching a child geometric shapes should take place in stages. You need to start new figures only after the baby remembers the previous ones. The circle is the simplest shape. Show your child round objects, feel them, let the baby run his finger over them. You can also make an application from circles, mold a circle from plasticine. The more sensations associated with the concept being studied, the child receives, the better the baby will remember it.

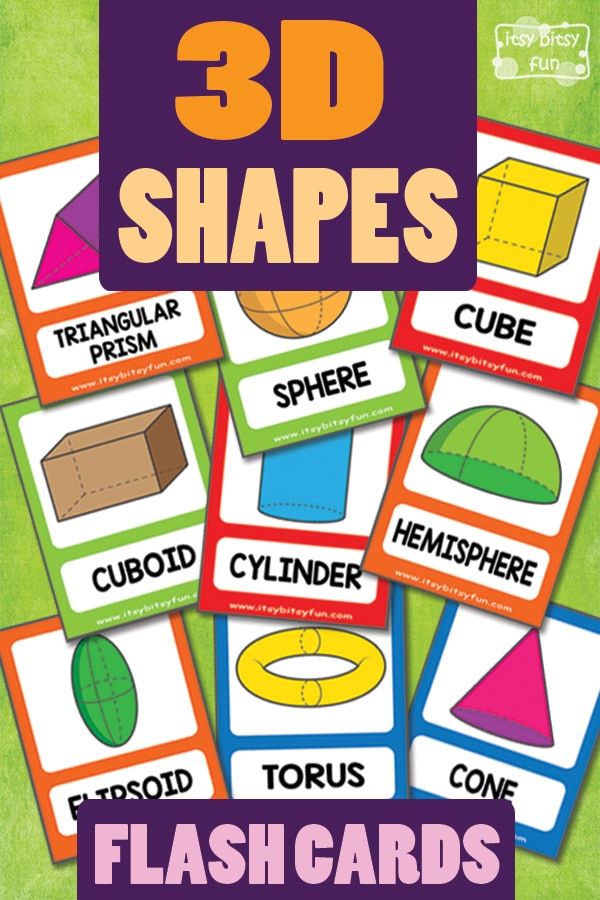

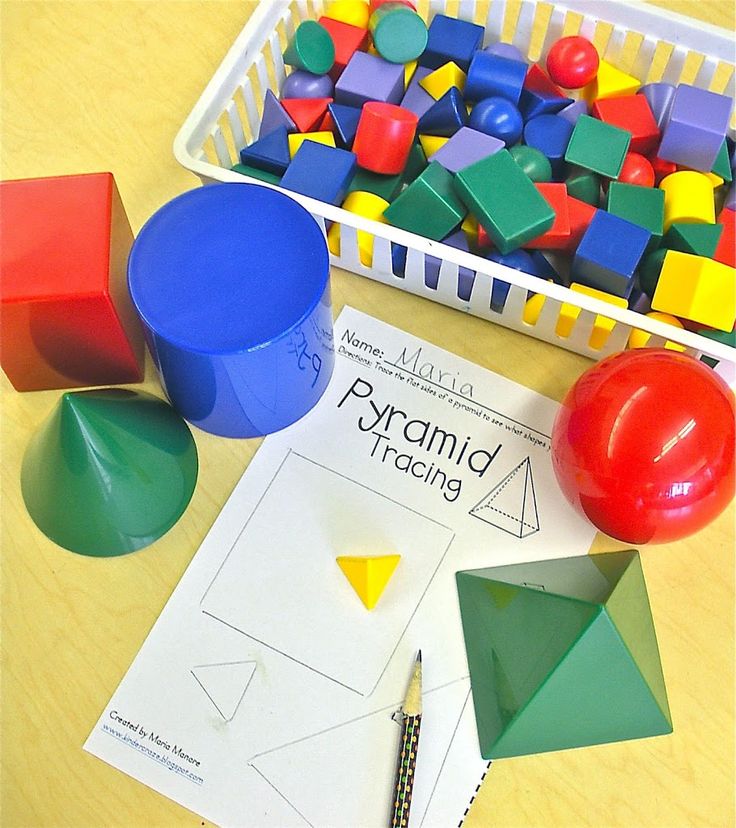

Three-dimensional figures can be used to get acquainted with forms. It can be made by a designer, a sorter, lacing, frame inserts. Since at an early age the visual-effective type of thinking is most developed, various actions with figures will help to remember them better.

How children of different ages perceive geometric figures

The operations that a child can perform with geometric figures and how he perceives shapes depend on the age of the baby. In accordance with age characteristics, the following stages of training can be distinguished:

- In the second year of life, the baby is able to visually recognize familiar figures and sort objects according to shape.

- At 2 years old, the child can find the desired figure among a number of other geometric shapes.

- By the age of 3, babies can name shapes.

- At the age of 4, a child is able to correlate three-dimensional figures with a flat image.

- At the senior preschool age (and sometimes even earlier) it is possible to start studying geometric bodies (ball, cube, pyramid). Also at this age, the child can analyze complex pictures consisting of many shapes.

Regardless of the child's age, try to pay attention to the shapes of the surrounding objects and compare them with known geometric shapes. This can be done at home and on the go.

Games for learning geometric shapes

For a child to be interested, learning geometric shapes should take place in a playful way. You should also select bright and colorful materials for classes (you can buy them in a store or do it yourself). Here are some examples of games and tutorials for learning geometric shapes:

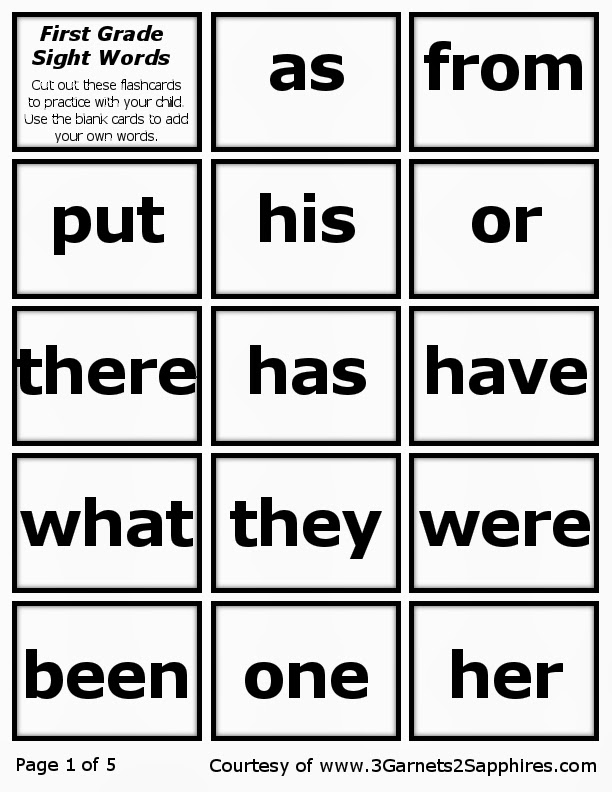

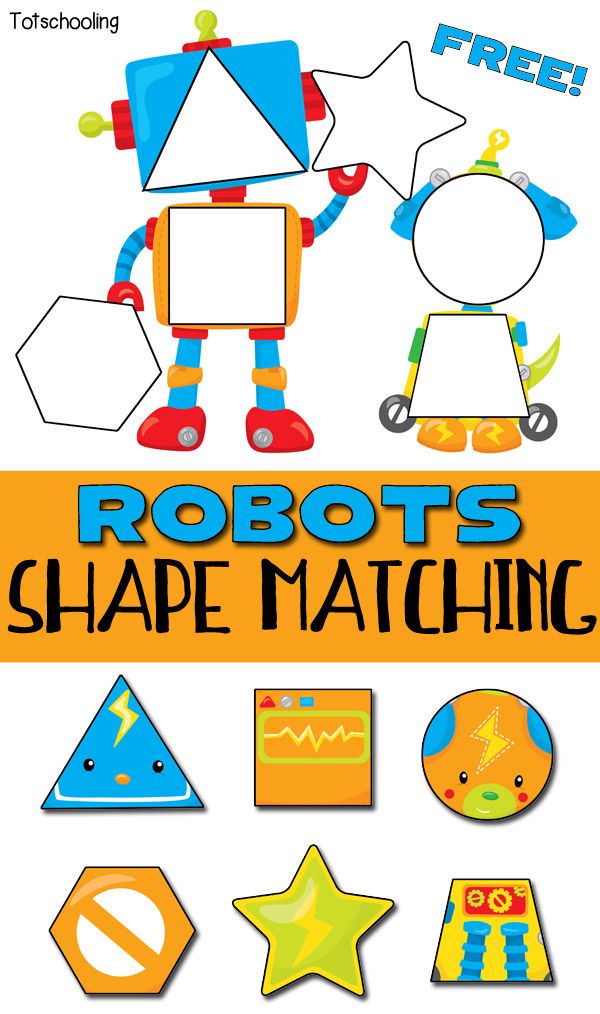

- Sorting. Games with a sorter can be started from the age of 1. Invite the child to find its window for the figure. So the child will not only memorize geometric shapes, but also develop fine motor skills, thinking and spatial representations, because in order for the part to fall into the hole, you need to turn it at the right angle.

You can also sort any other items, such as building blocks, Gyenesch blocks, or counting material.

You can also sort any other items, such as building blocks, Gyenesch blocks, or counting material. - Insert frames. In fact, this manual is similar to a sorter. For each geometric figure, you need to find its place.

- Geometric lotto. To play, you will need a field with the image of geometric shapes and handout cards with each figure separately. A child can take small cards out of a chest or bag, and then look for their place on the playing field. This game also perfectly trains the attention of the baby.

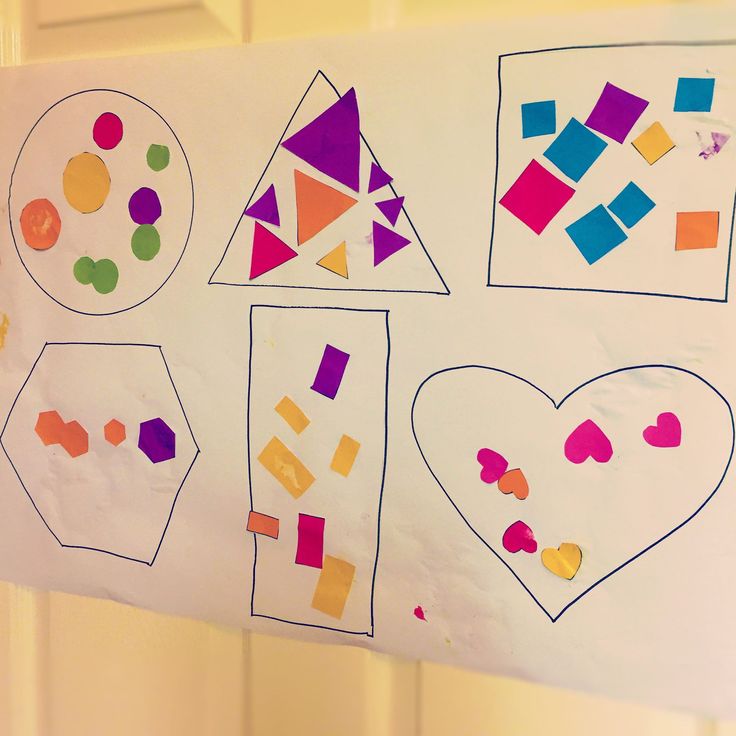

- Geometric appliqué. Cut out various geometric shapes from paper and, together with your child, make a picture out of them (for example, you can make a Christmas tree from triangles, a house from a square and a triangle).

- Drawing (including stencils).

- Modeling.

- Laying out figures from counting sticks.

- Geometric mosaic.

- Laces with geometric shapes.

- Card games.

- Guess by touch.

- Active games. Draw geometric shapes on the pavement with chalk. Ask the child to imagine that the figures are houses that you need to run into on a signal. Next, you name a geometric figure, and the child runs to it.

In addition, educational cartoons can be used to study geometric shapes. Here is one of them:

Conclusions

Teaching the basics of geometry at preschool age is an important part of developing a child's mathematical and sensory perceptions. Acquaintance with the figures should occur gradually (first, simple figures - a circle, a square, a triangle). To keep your child interested, study geometric shapes in a playful way. Your assistants in this can be such educational aids as insert frames, mosaics, lotto, sorters, sets of geometric shapes and bodies, stencils.