Little jack horner

'Little Jack Horner' : NPR

Reason Behind the Rhyme: 'Little Jack Horner' Host Debbie Elliott and Chris Roberts dissect the meaning of the nursery rhyme "Little Jack Horner." It's about a real estate swindle in 16th-century England. Roberts is the author of Heavy Words Lightly Thrown: The Reason Behind the Rhyme.

Heard on All Things Considered

Reason Behind the Rhyme: 'Little Jack Horner'

Host Debbie Elliott and Chris Roberts dissect the meaning of the nursery rhyme "Little Jack Horner." It's about a real estate swindle in 16th-century England. Roberts is the author of Heavy Words Lightly Thrown: The Reason Behind the Rhyme .

DEBBIE ELLIOTT, host:

This is ALL THINGS CONSIDERED from NPR News. I'm Debbie Elliott.

You think the real estate market is treacherous today, try England in the late 1530s. That's what the nursery rhyme "Little Jack Horner" is really all about.

(Soundbite of music)

ELLIOTT: Here to explain is our London librarian Chris Roberts. He's the author of "Heavy Words Lightly Thrown: The Reason Behind the Rhyme," and he's at our London bureau.

Hello again, Chris.

Mr. CHRIS ROBERTS (Author, "Heavy Words Lightly Thrown"): Hello. Hi, Debbie.

ELLIOTT: So who was Little Jack Horner?

Mr. ROBERTS: Little Jack Horner was actually Thomas Horner. The name Jack comes up in nursery rhymes a lot, usually to reflect a slightly knavish character, a bit of a ne'er-do-well. So I suspect that's why they changed his name to Jack from Thomas.

(Reading) `Little Jack Horner sat in a corner eating his Christmas pie. He stuck in a thumb and pulled out a plum and said, "What a good boy am I."'

Where to begin with this? This is talking about the dissolution of the monasteries, Henry VIII taking property from the Catholic Church..gif) Jack, as we know, is actually called Thomas Horner. Now he was a steward to the Abbot of Glastonbury during the reign of Henry VIII. This is how the story goes: He was entrusted to take some title deeds of properties to Henry VIII as a bribe so the abbot could keep the main monastery, but was prepared to give away some of the lesser properties.

Jack, as we know, is actually called Thomas Horner. Now he was a steward to the Abbot of Glastonbury during the reign of Henry VIII. This is how the story goes: He was entrusted to take some title deeds of properties to Henry VIII as a bribe so the abbot could keep the main monastery, but was prepared to give away some of the lesser properties.

Now the title deeds were held and sealed in a pie, and Jack's off to London. But instead of delivering the bribe to Henry VIII, he helps himself to the pie, puts his hand in, pulls out a plum piece of real estate--in this case, a place called Mells Manor--and thinks he's very clever for doing this. That's one version of it, that Jack is a thief and he's stealing the bribe that's intended for the king. And he...

ELLIOTT: So was this common? Is there historical evidence to support the theory that bribes were often delivered in pies?

Mr. ROBERTS: It comes up bewilderingly often in nursery rhyme. And it's--I think the pie is used as a metaphor. I think it's not necessarily what we would think of as a pie. It's just referring to a means of concealing a document, concealing anything. It could be jewels in some cases. Now the Horner family, who incidentally lived in Mells Manor until the 20th century, are quite outraged at this slander of their ancestor and understandably so.

And it's--I think the pie is used as a metaphor. I think it's not necessarily what we would think of as a pie. It's just referring to a means of concealing a document, concealing anything. It could be jewels in some cases. Now the Horner family, who incidentally lived in Mells Manor until the 20th century, are quite outraged at this slander of their ancestor and understandably so.

And there are actually two rhymes that mention Mr. Horner. The first one that mentions him is: `Hopton(ph), Horner, Smith and Finn, when the abbots went out, they came in.' And a much more likely reading of what happened is that Thomas Horner, along with the other people mentioned in the previous rhyme--Hopton and Smith and Finn--were up-and-coming gentry. They were Protestant, they were local merchants doing quite well for themselves in the area around Glastonbury, and that they bought the property. You could see it as an early example of gentrification. They bought the property at the time admittedly at a knockdown rate, and admittedly the land had been stolen from the Catholic Church by Henry VIII. This seems to be what happened after the dissolution of the monasteries. The king didn't keep all the land for himself; he distributed it amongst his supporters so he then could rely on their loyalty should anything occur in the future, should there be a rebellion in the future. I suspect, though I can't prove this, that the popular `Little Jack Horner sat in a corner, eating his Christmas pie' version is actually the Catholic take on proceedings there.

They bought the property at the time admittedly at a knockdown rate, and admittedly the land had been stolen from the Catholic Church by Henry VIII. This seems to be what happened after the dissolution of the monasteries. The king didn't keep all the land for himself; he distributed it amongst his supporters so he then could rely on their loyalty should anything occur in the future, should there be a rebellion in the future. I suspect, though I can't prove this, that the popular `Little Jack Horner sat in a corner, eating his Christmas pie' version is actually the Catholic take on proceedings there.

ELLIOTT: Chris Roberts is the author of "Heavy Words Lightly Thrown: The Reason Behind the Rhyme," and he's a librarian at Lambeth College in South London.

Thank you, Chris.

Mr. ROBERTS: Thank you, Debbie.

Copyright © 2006 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www. npr.org for further information.

npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

Sponsor Message

Become an NPR sponsor

A Short Analysis of the ‘Little Jack Horner’ Nursery Rhyme – Interesting Literature

LiteratureBy Dr Oliver Tearle

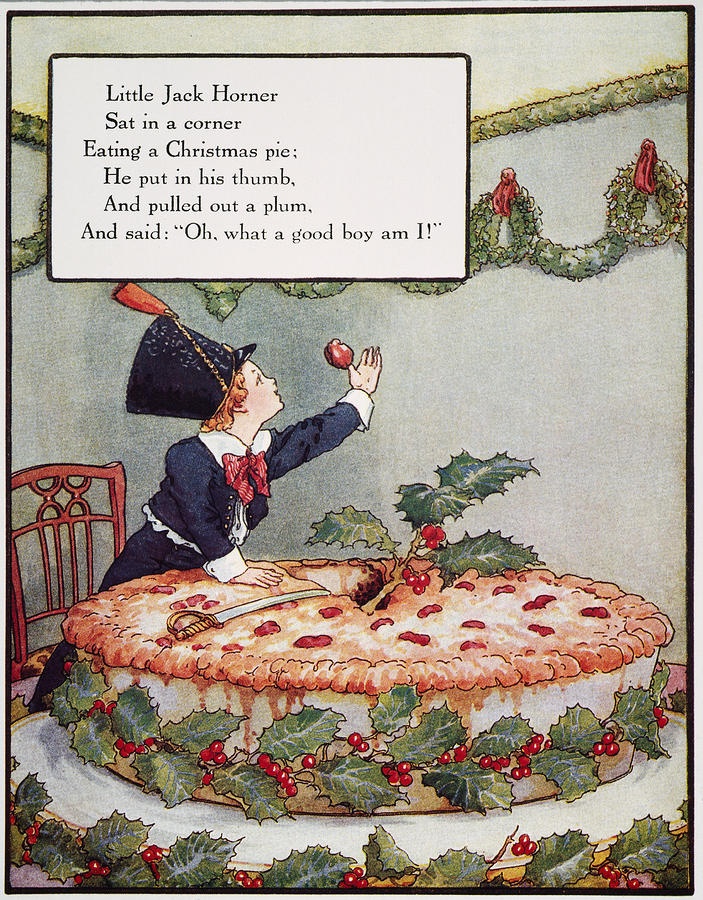

‘Little Jack Horner’ has attracted a good deal more speculation than many other famous nursery rhymes, and others have had a fair bit. But for some reason, this little children’s rhyme about a boy eating a Christmas pie and pulling out a plum has been the subject of more debate than 90% of nursery rhymes in the English language. Why has the rhyme of ‘Little Jack Horner’ attracted such wild analysis, interpretation, and speculation? First, here’s a reminder of the words:

Little Jack Horner

Sat in the corner,

Eating a Christmas pie;

He put in his thumb,

And pulled out a plum,

And said, ‘What a good boy am I!’

We mentioned in our analysis of another nursery rhyme, ‘Sing a Song of Sixpence’, that some scholars or enthusiasts of nursery rhymes seem to want to make all of them about the Dissolution of the Monasteries and the English Reformation. But Reformation intrigue also surrounds ‘Little Jack Horner’, and here the case is a little more persuasive and interesting, although nevertheless nothing more than speculation.

But Reformation intrigue also surrounds ‘Little Jack Horner’, and here the case is a little more persuasive and interesting, although nevertheless nothing more than speculation.

The story goes as follows. A man named Thomas Horner was steward to Richard Whiting, the last of the abbots at Glastonbury Abbey. When King Henry VIII was dissolving the monasteries, the abbot sent Horner to London with the gift of a Christmas pie, in which were concealed the title deeds to twelve manors, which were designed to appease Henry in the hope that he would allow Glastonbury to survive the purging of the monasteries. But, when Horner returned to Glastonbury he opened the pie and pilled out the deeds of the Manor of Mells, which he had kept from Henry, meaning the monastery still had some of its own land.

What makes the link between this story and the rhyme of Little Jack Horner a little more scintillating is that we know that a man named Thomas Horner took up residence at Mells not long after the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Neat, huh? But the Horner family descended from this sixteenth-century Thomas Horner claim that their ancestor bought the manor, rather than plucking it from a pie. So it’s difficult to know whom to believe.

Neat, huh? But the Horner family descended from this sixteenth-century Thomas Horner claim that their ancestor bought the manor, rather than plucking it from a pie. So it’s difficult to know whom to believe.

‘Little Jack Horner’ was later worked into a longer rhyme, which was published as a chapbook in 1764. (Many familiar nursery rhymes were popularised by the chapbook form around this time: ‘Old Mother Hubbard’ first became a bestseller and household name when it was published as a chapbook in the early nineteenth century.) But it seems clear that the original six-line rhyme of ‘Little Jack Horner’ was of an older vintage, and may well have been penned in reference to Thomas Horner’s acquisition of his Mells estate. Even if the real Thomas Horner acquired his manor fair and square, tongues may have wagged in those divided times. In the last analysis, we’ll probably never know for sure just how closely the events of Thomas Horner’s life and the pie-poking events described in the rhyme were related.

The author of this article, Dr Oliver Tearle, is a literary critic and lecturer in English at Loughborough University. He is the author of, among others, The Secret Library: A Book-Lovers’ Journey Through Curiosities of History and The Great War, The Waste Land and the Modernist Long Poem.

Image: via Wikimedia Commons.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Tags: Analysis, Children's Literature, Henry VIII, History, Little Jack Horner, Nursery Rhymes, Origins, Summary, Thomas Horner

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Songs For Children - Little Jack Horner

Songs For Children - Little Jack Horner

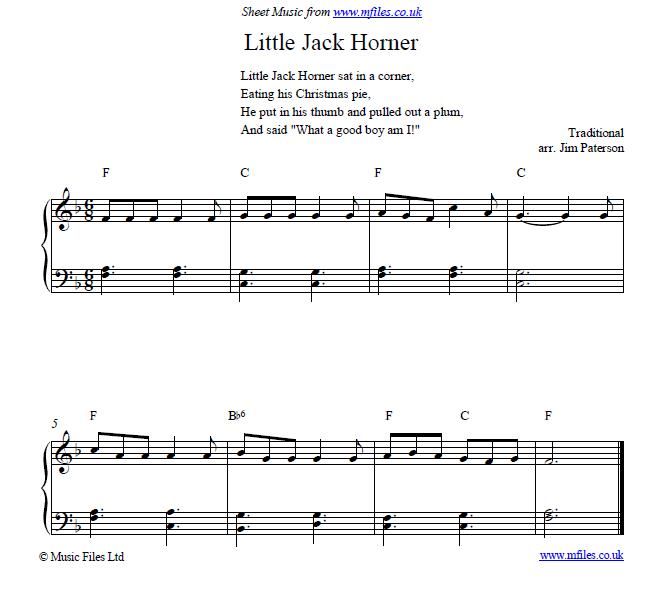

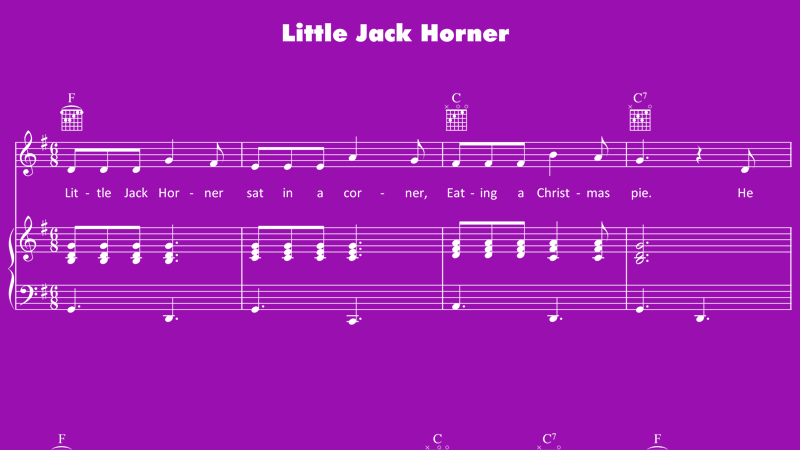

Little Jack Horner sat in a corner eating his Christmas pie

He put in his thumb, and pulled out a plum

And said, "What a good boy am I"

Little Jack Horner knew he was born the day before Christmas day

He said to himself, "I'll sit on the shelf and Merrily carol away"

The girls and the boys on hearing the noise

Came running from far and near

They saw the great plum on top on top of Jack's thumb

And everyone started to Cheer

Everyone started to cheer, "Hooray!"

Album

A to Z of Childrens Stories, Songs & Nursery Ryhmes

release date

22-03-2010

one Over The Hills And Far Away

2 The Animals Went In Two By Two

3 She'll Be Coming 'Round The Mountain

four Polly Put the Kettle On

5 Diddle Diddle Dumpling (Childrens Vocal Version)

6 George Porgie

7 Girls And Boys Come Out To Play (Female Vocal Version)

eight Beauty and the Beast (Story)

9 Hey Diddle Diddle (Sing-Along Version)

ten Hop, Skip and Jump (Female Vocal Version)

eleven Bobby Shafto (Alt. Female Vocal Version)

Female Vocal Version)

12 There Was A Crooked Man

13 Puppy Doodle Puppy

fourteen Pop Goes The Weasel

fifteen Three Blind Mice

16 Here We Go Looby Loo (Alt. Female Vocal Version)

17 Gee Up Neddy

eighteen Eight Rowers In A Boat

19 Any More For The Skylark

twenty There Once Was An Ugly Duckling

21 Flying In My Balloon

22 Sur Le Pont D'Avignon

23 Higgledy Piggledy (Childrens Vocal Version)

24 Hey De Ho

25 good old father time

26 Grandpa Ted's Spoons

27 Gerald The Giraffe

28 Don't Tamper With Time

29 Don't Upset The Camel

thirty Ding Dong Bell, Pussy's In The Well

31 Better Go Steady Father Time

32 Cobbler Cobbler Mend My Shoe

33 A Tisket A Tasket (Alt.

I. 274

I. 274  : 245915 (Author of the post: Galina Shanenko VIP ), added: 24.12.2020 20:22

: 245915 (Author of the post: Galina Shanenko VIP ), added: 24.12.2020 20:22  09 KB) |

09 KB) |  ru - photos of old towns.

ru - photos of old towns.