Name the sound

A2: Name That Sound | Sight Words: Teach Your Child to Read

- Overview

- Materials

- Activity

- Confidence Builder

- Extension

- Variation

- Small Groups

- Questions and Answers

1. Overview

The child listens to a sound and has to identify the sound. This helps the child learn to focus their attention onto a particular sound.

A2: Name That Sound

↑ Top

2. Materials

A smartphone or computer that can play the sounds below:

- alarm

- ambulance / police siren

- applause / cheering

- baby

- bell ringing

- bird

- cat

- coughing

- cow

- dog

- donkey

- duck

- fog horn / train

- footsteps

- frog

- heartbeat

- horse

- knocking / tapping

- lion

- mosquito

- owl

- pig

- race car

- rooster

- running water

- sawing

- sheep

- sneeze

- snoring

- toilet flushing

- wolf

- yawning

NOTE: There is no need to use all or even most of these sounds. Just pick a few that your child is familiar with. This game is about paying attention, not sound identification!

↑ Top

3. Activity

Prepare the child by playing all the sounds you are going to use, naming each sound as you hear it. This gets the child familiar with the sounds and their names.

Adult: [plays Cow] That was a cow.

[plays Rooster] That was a rooster.

[plays Baby] That was a baby.

Talk to your child about how to listen. Show him how to close his eyes and focus on what he hears, not just what he sees.

Video: How to play Name That Sound

Have your child sit with his eyes closed and listen while you play a sound for him. Then ask what he thinks it is.

Then ask what he thinks it is.

Adult: Listen. [plays Dog]

What was that sound?

Child: Umm…

Adult: Let’s play it again. Listen. [plays Dog]

What did you hear?

Child: A dog!

Repeat this several times with a variety of sounds.

↑ Top

4. Confidence Builder

If the child has trouble identifying a sound, help by giving two options.

Adult: Listen. [plays Cow] OK, what was that sound?

Child: Umm…I dunno.

Adult: Was it a cow, or a drum?

Child: Cow!

↑ Top

5. Extension

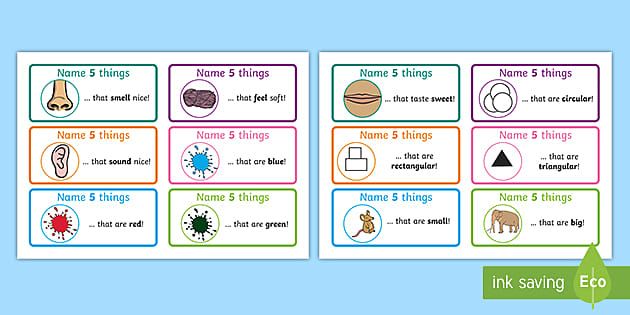

Instead of playing sound clips, use environmental sounds—anything happening around you. Have him sit with his eyes closed and just listen to the sounds around him for a few minutes. Then ask him to identify or describe the sounds he heard.

Start with just the usual noises (e.g., hum of the refrigerator) and then maybe add some of your own (e.g., crumpling paper). Here are some examples:

- Wind blowing

- Trees rustling

- Cars driving on street

- Airplane flying overhead

- Appliances running

- Clock ticking

- Jingling dog collar

- Crumpling paper

- Bouncing a ball

- Whistling

- Chewing something crunchy

- Snapping fingers

This game forms the foundation for First Sound, Last Sound (A4) and First, Next & Last Sounds (A6), where the child starts to identify and order longer sound sequences.

↑ Top

6. Variation

You can engage in this activity outside the home as well. Ask your child what he hears while you’re in the car, at the park, in the grocery store, etc.

↑ Top

7.

Small Groups (2-5 children)

Small Groups (2-5 children)

Lesson Objective: Children will be able to focus their attention and identify a specific sound.

GELDS (Georgia Early Learning & Development Standards): CLL2.2b, PDM4

Adaptation: Read the main activity, watch the video, and follow the instructions above, with the following changes:

- Have the children take turns making sounds for the others to identify.

- Have the children select an animal sound for the children to identify.

Reinforcement: Do a quick check to see that children are paying proper attention to the sounds. Play or make a sound, such as a dog barking. Then prompt the children with questions that they answer with a thumbs up or thumbs down gesture, like this:

Adult: Listen. [makes sound] Was that a cat?

Children: [thumbs down]

Adult: Was that a baby?

Children: [thumbs down]

Adult: Was that a dog?

Children: [thumbs up]

Use this Reinforcement at Home form to tell parents and guardians how they can reinforce lessons outside the classroom.

↑ Top

Leave a Reply

INFANTS’ RECOGNITION OF THE SOUND PATTERNS OF THEIR OWN NAMES

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

- PMC4140581

Psychol Sci. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2014 Aug 21.

Published in final edited form as:

Psychol Sci. 1995 Sep; 6(5): 314–317.

doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1995.tb00517.x

PMCID: PMC4140581

NIHMSID: NIHMS278507

PMID: 25152566

,1,1 and 2,3

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Among the earliest and most frequent words that infants hear are their names. Yet little is known about when infants begin to recognize their own names. Using a modified version of the head-turn preference procedure, we tested whether 4.5-month-olds preferred to listen to their own names over foils that were either matched or mismatched for stress pattern. Our findings provide the first evidence that even these young infants recognize the sound patterns of their own names. Infants demonstrated significant preferences for their own names compared with foils that shared the same stress patterns, as well as foils with opposite patterns. The results indicate when infants begin to recognize sound patterns of items frequently uttered in the infants’ environments.

Yet little is known about when infants begin to recognize their own names. Using a modified version of the head-turn preference procedure, we tested whether 4.5-month-olds preferred to listen to their own names over foils that were either matched or mismatched for stress pattern. Our findings provide the first evidence that even these young infants recognize the sound patterns of their own names. Infants demonstrated significant preferences for their own names compared with foils that shared the same stress patterns, as well as foils with opposite patterns. The results indicate when infants begin to recognize sound patterns of items frequently uttered in the infants’ environments.

Research on early cognitive and perceptual capacities indicates that infants enter the world equipped with a surprisingly broad set of abilities. For example, infants seem to have a notion of physical identity that matches adult conceptions of object properties. Not only do young infants demonstrate sensitivity to the relative permanence of objects (Baillargeon, Graber, DeVos, & Black, 1990), they also appear to have at least a rudimentary understanding of causal relations (Leslie & Keeble, 1987) and of number (Starkey, Spelke, & Gelman, 1990; Wynn, 1992).

The precocious capacities of infants are perhaps best documented for the domain of language. It is well established that within the first 2 months of life, infants are able to discriminate a wide range of speech contrasts (Eimas, Siqueland, Jusczyk, & Vigorito, 1971; Trehub, 1976). Moreover, they appear to be able to compensate for stimulus variability introduced into speech by changes in speaking rate (Eimas & Miller, 1980) and talkers’ voices (Jusczyk, Pisoni, & Mullennix, 1992; Kuhl, 1979). These early abilities allow infants to begin the process of categorizing the information available in speech and ultimately lead to acquisition of a native language.

Infants’ basic speech perception capacities provide a starting point for discovering how sound patterns are organized in their native language. Because languages differ in their organization of sounds into meaningful units, infants must learn about the characteristics that hold for utterances in their language. There is now evidence that infants begin learning about particular properties of native-language utterances from an early age. For example, it has been demonstrated that even newborns show some capacity to discriminate utterances in their mothers’ native language from those in another language (Mehler et al., 1988). There are also indications that within the 1st year, infants learn about various aspects of sound organization in their native language: phonetic categories and their internal structure (Kuhl, Williams, Lacerda, Stevens, & Lindblom, 1992; Werker & Tees, 1984), the characteristic sequences of sounds permitted in words (Jusczyk, Friederici, Wessels, Svenkerud, & Jusczyk, 1993), and the prosody typical of words (Jusczyk, Cutler, & Redanz, 1993). However, communication in language requires not only learning about the distinctive sound properties of one’s language, but also learning to recognize certain sound patterns and to relate these to particular meanings.

There is now evidence that infants begin learning about particular properties of native-language utterances from an early age. For example, it has been demonstrated that even newborns show some capacity to discriminate utterances in their mothers’ native language from those in another language (Mehler et al., 1988). There are also indications that within the 1st year, infants learn about various aspects of sound organization in their native language: phonetic categories and their internal structure (Kuhl, Williams, Lacerda, Stevens, & Lindblom, 1992; Werker & Tees, 1984), the characteristic sequences of sounds permitted in words (Jusczyk, Friederici, Wessels, Svenkerud, & Jusczyk, 1993), and the prosody typical of words (Jusczyk, Cutler, & Redanz, 1993). However, communication in language requires not only learning about the distinctive sound properties of one’s language, but also learning to recognize certain sound patterns and to relate these to particular meanings.

Whereas many investigations have focused on infants’ sensitivities to various sound properties of language, relatively few studies have explored the antecedents of relating sounds to meanings. What information is available on the latter issue comes largely from studies with approximately 9-month-old infants on the verge of producing their first words (e.g., Benedict, 1979; Huttenlocher, 1974). Such studies indicate that infants at this age show some limited comprehension of a few words. However, these studies do not indicate just when or how the process of lexical development actually begins.

What information is available on the latter issue comes largely from studies with approximately 9-month-old infants on the verge of producing their first words (e.g., Benedict, 1979; Huttenlocher, 1974). Such studies indicate that infants at this age show some limited comprehension of a few words. However, these studies do not indicate just when or how the process of lexical development actually begins.

One potential antecedent of relating sounds to meanings is beginning to recognize sound patterns that are uttered frequently in communicative settings that actively engage an infant’s attention. For example, while playing with an infant, parents frequently use the child’s name. To what extent does the infant begin to recognize the sound patterns corresponding to his or her own name? Considering the potential implications that learning one’s own name might have not only for beginning to learn relations between sounds and meanings, but also for eventually establishing a sense of identity, it is surprising that so little attention has been given to this issue in previous research. The present study was designed to explore whether infants as young as 4.5 months demonstrate even the first signs of recognizing their own names.

The present study was designed to explore whether infants as young as 4.5 months demonstrate even the first signs of recognizing their own names.

One aspect of recognizing one’s name is to treat utterances of that name as being different from utterances of other names. For example, are repetitions of an infant’s own name more likely to capture the infant’s attention than repetitions of other names? Certainly, adults’ attention is more apt to be drawn to utterances of their own names (Howarth & Ellis, 1961; Moray, 1959). Furthermore, carefully selecting which other names to present along with an infant’s own name should make it possible to gain information about just how precise the infant’s representation of the sound pattern of his or her name is. For instance, it is certainly possible that at an early stage of development, an infant encodes only some rather global features of the sound pattern (e.g., the stress pattern, the number of syllables) of his or her name. Consequently, in the present study, we examined whether infants who heard their own names along with stress-matched or stress-mismatched foils would show any significant tendency to listen to their own names.

Previous research indicates that infants between the ages of 7 and 10 months exhibit some recognition of words. For example, infants between the ages of 8 and 10 months show some comprehension of certain native-language words (Benedict, 1979; Huttenlocher, 1974). In addition, 7.5-month-olds display some rudimentary capacity for recognizing words in fluent speech and retaining them (Jusczyk & Aslin, in press). Because their own names are presumably among the first and most frequent words that infants hear, we decided to test even younger infants to see if they show some evidence for recognizing these special lexical items.

Subjects

Twenty-four infants from homes in which only English is spoken were recruited to participate in the present study (mean age = 149 days; range = 133 days-167 days). Half of the infants were males; the other half were females. An additional 13 infants were eliminated because of excessive fussiness or crying (n = 9), failure to orient properly to the test apparatus (n = 2), and experimenter error or testing interference (n = 2).

Stimuli and Apparatus

Each infant was presented with repetitions of four different names: his or her own name and three foils. The foils were designed to assess whether the infant would commit false alarms to names with prosodic patterns similar to those of the infant’s own name. Specifically, one foil matched the stress pattern of the infant’s name; the other two followed the opposite stress pattern. For example, an infant whose name was Aaron might be presented with three foils such as “Corey” (same stress), “Christine” (opposite stress), and “Michelle” (opposite stress). provides a full listing of all infants’ names and foils used in the present study.1 Although all infants heard foils that either matched or mismatched the stress patterns of their own names, they did not all hear exactly the same set of foils. Rather, a different set of foils was used for each infant to control for the possibility that some names might be inherently more interesting to listen to. Each name was repeated 15 times to create a stimulus file for testing. The names were digitally recorded by a naive female talker who was not informed about which names were foils and which belonged to infants participating in the experiment. In fact, some foils were actually the names of other infants in the study. These precautions ensured that each infant’s own name would not be unduly emphasized relative to any of the foil names. The talker was encouraged to record the names with lively affect, as if calling to an infant, and to vary her productions across the different repetitions of the names.

Each name was repeated 15 times to create a stimulus file for testing. The names were digitally recorded by a naive female talker who was not informed about which names were foils and which belonged to infants participating in the experiment. In fact, some foils were actually the names of other infants in the study. These precautions ensured that each infant’s own name would not be unduly emphasized relative to any of the foil names. The talker was encouraged to record the names with lively affect, as if calling to an infant, and to vary her productions across the different repetitions of the names.

Table 1

List of children’s names and corresponding foil sets

| Child’s name | Same- stress foil | Different-stress foils | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | ||

| Joshua | Agatha | Maria | Eliza |

| Johnny | Abby | Elaine | Lamont |

| Sarah | Michael | Kathleen | Nicole |

| Becca | Aaron | Rumiz | Michele |

| Abby | Carol | Michele | Rumiz |

| Emmie | Connor | Denise | Marie |

| Christopher | Jessica | Eliza | Marissa |

| Henry | Corey | Rumiz | Christine |

| Katie | Kevin | Denise | Lavern |

| Cameron | Jenna | Elaine | Nicole |

| Brandon | Kevin | Lorraine | Nicole |

| Emily | Christopher | Marissa | Samantha |

| Rachel | Meghan | Darlene | Justine |

| Dana | Brandon | Elaine | Justine |

| Nick | Ben | Lucy | Travis |

| Erin | Connor | Rumiz | Christine |

| Corey | Lucy | Christine | Nicole |

| Ky | Meg | Audrey | Connor |

| Sam | Bob | Carol | Henry |

| Jojo | Mimi | Denise | Lavern |

| Philip | Kathy | Michele | Rumiz |

| Steven | Kyle | Rumiz | Michele |

| Emily | Joshua | Marissa | Maria |

| Travis | Lucy | Darlene | Michele |

Open in a separate window

All names were digitized on a VAXStation Model 3176 computer at a sampling rate of 10 kHz via a 12-bit analog-to-digital converter. The digitized stimuli were then transferred to a PDP 11/73 computer, which controlled the presentation of the names and recorded the observer’s coding of the infant’s responses throughout the testing session.

The digitized stimuli were then transferred to a PDP 11/73 computer, which controlled the presentation of the names and recorded the observer’s coding of the infant’s responses throughout the testing session.

Procedure

A modified version of the head-turn preference procedure was employed (see Jusczyk & Aslin, in press, and Kemler Nelson et al., 1995, for an extensive review of the procedure). Each infant sat on a caregiver’s lap in the middle of a three-sided enclosure constructed out of pegboard panels (4 ft by 6 ft) on three sides and open at the back. On the center panel of the enclosure, directly facing the infant, was a green light, mounted at eye level, that could be flashed to attract the infant’s attention to midline. A red light was mounted on each side panel, and a loudspeaker was mounted at the infant’s ear level behind each side panel. In addition, a video camera mounted behind the center panel recorded each test session. An experimenter, seated behind the center panel, observed the infant through a small hole. She began and terminated trials, recording the infant’s looking times by operating a response box linked to a PDP 11/73 computer.

She began and terminated trials, recording the infant’s looking times by operating a response box linked to a PDP 11/73 computer.

A test trial began with the flashing of the green light on the center panel. When the infant was facing center, the green light was extinguished, and a red light on one of the side panels began to flash. When the infant made a head turn of at least 30° in the direction of the flashing light, the experimenter initiated a speech sample from the loudspeaker on the same side as the light and began recording the infant’s looking time by pressing a button on the response box. If the infant turned away from the loudspeaker by 30° for less than 2 consecutive seconds, and then reoriented in the appropriate direction, the trial continued, but the time spent looking away from the loudspeaker was eliminated from the total orientation time on that particular trial (the experimenter pressed another button on the response box that stopped the timer). If the infant looked away for more than 2 consecutive seconds, the trial was terminated.

Both the experimenter and the caregiver wore SONY MDR-V600 sound-insulated headphones and listened to loud masking music to prevent them from hearing the stimulus materials throughout the duration of the experiment. The music was highly effective in masking the test stimuli (see Kemler Nelson et al., in press).

Each session began with a preparatory phase in which the infant was presented with musical stimuli to familiarize the infant with the lights on the sides of the testing booth and to ensure that he or she was capable of making the required orienting response.2 This phase continued until the infant accumulated 40 s of listening time to the musical stimuli. The loud-speaker from which the stimuli were emitted varied randomly from trial to trial. After the infant completed this preparatory phase, the test phase began. Stimuli for the test phase consisted of the stimulus file of the 15 repetitions of the infant’s name and the files for the three foils. Test trials were blocked in groups of four. The stimulus set for each of the four names (the infant’s own, along with the three foils) appeared once in a given block in random order. Each infant was tested on three blocks, completing 12 test trials in all.

The stimulus set for each of the four names (the infant’s own, along with the three foils) appeared once in a given block in random order. Each infant was tested on three blocks, completing 12 test trials in all.

Mean listening time to each name was calculated for each infant across the three blocks of trials. These means were then averaged for the infants’ own names and for each group of foils (one group of same-stress names and two groups of different-stress names). Across all 24 subjects, the average listening times were 16.14 s (SD = 5.49 s) for the infants’ own names, 13.03 s for names with the same stress pattern (SD = 6.26 s), and 12.17 s and 12.39 s for the two groups of different-stress names (SD = 5.46 s and 5.10 s). An analysis of variance revealed that these means were significantly different, with a main effect of name category, F(3, 69) = 5.60, p = .0017. Moreover, a series of planned comparisons indicated that infants demonstrated significant listening preferences for their own names compared with names that had identical stress patterns (t[23] = 2. 64, p = .014), as well as compared with names that followed opposite patterns (t[23] = 3.98, p = .000, and t[23]= 3.54, p = .002, for the two groups of oppositely patterned names). No other comparisons reached significance.

64, p = .014), as well as compared with names that followed opposite patterns (t[23] = 3.98, p = .000, and t[23]= 3.54, p = .002, for the two groups of oppositely patterned names). No other comparisons reached significance.

The present results indicate that by 4.5 months of age, infants listen longer to their own names than to other infants’ names. In addition, the pattern of longer listening times to one’s own name occurred even in the presence of prosodically similar foils. This finding suggests that 4.5-month-olds have a rather detailed representation of the sound patterns of their names. Each infant responds differentially to a particular sound pattern that will eventually have special social and perceptual significance for him or her (Howarth & Ellis, 1961; Moray, 1959; Van Lancker, 1991; Wood & Cowan, in press).

Although the present results do not demonstrate that infants actually comprehend their own names, the ability to recognize and respond to sound patterns of frequently occurring items is clearly a prerequisite for relating sounds to meanings. Ultimately, learning a word involves recognizing that a particular sound pattern consistently refers to a given object or meaning. This process requires that the learner not only has stored the appropriate meaning, but also recognizes and remembers the sound pattern that is associated with it. Thus, word learning may sometimes involve storing away an interesting sound pattern that will be subsequently attached to a meaning, as well as learning the names that correspond to meanings one wants to express—the more traditional view (MacWhinney, 1987; Pinker, 1984). Sound patterns of words frequently uttered when parents interact with their infants, such as the infants’ names, are apt to be salient. Consequently, they are good candidates to be encoded into memory. Of course, the major breakthrough in word learning comes when infants learn that these sound patterns can stand for specific meanings.

Ultimately, learning a word involves recognizing that a particular sound pattern consistently refers to a given object or meaning. This process requires that the learner not only has stored the appropriate meaning, but also recognizes and remembers the sound pattern that is associated with it. Thus, word learning may sometimes involve storing away an interesting sound pattern that will be subsequently attached to a meaning, as well as learning the names that correspond to meanings one wants to express—the more traditional view (MacWhinney, 1987; Pinker, 1984). Sound patterns of words frequently uttered when parents interact with their infants, such as the infants’ names, are apt to be salient. Consequently, they are good candidates to be encoded into memory. Of course, the major breakthrough in word learning comes when infants learn that these sound patterns can stand for specific meanings.

It is possible that, in addition to their own names, 4.5-month-olds recognize other words that occur frequently in their language-learning environments (e. g., terms that relate to other socially salient persons, objects, or events). Regardless of whether there are other items that are learned even earlier than infants’ own names, infants as young as 4.5 months of age are learning to recognize sound patterns that will have a special personal significance for them. This achievement, in turn, may set the stage for relating sounds to meanings.

g., terms that relate to other socially salient persons, objects, or events). Regardless of whether there are other items that are learned even earlier than infants’ own names, infants as young as 4.5 months of age are learning to recognize sound patterns that will have a special personal significance for them. This achievement, in turn, may set the stage for relating sounds to meanings.

We thank A.M. Jusczyk and N.J. Redanz for their help in testing, and A. Worden and D. Dombrowski for recruiting subjects. We also thank D.G. Kemler Nelson for helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. This work was supported by research grants from the National Institute for Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) and the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development to P.W.J. and from NIDCD to D.B.P.

1Because studies of this type have not been done previously, it was hard to know a priori which variable would prove most important in infants’ representations of names at this early stage. Given the wealth of research suggesting that prosodic factors play a substantial role in early language acquisition, we decided to begin our investigation by manipulating stress pattern alone. Certainly, other variables (e.g., phonetic and featural information) might play an important role as well, and remain a topic for future investigation.

Given the wealth of research suggesting that prosodic factors play a substantial role in early language acquisition, we decided to begin our investigation by manipulating stress pattern alone. Certainly, other variables (e.g., phonetic and featural information) might play an important role as well, and remain a topic for future investigation.

2Prior research using this procedure has demonstrated that infants at this age often fail to orient to their sides without some degree of prompting. This beginning phase was added to our study to deal with the possibility that infants would not spontaneously make the required orienting response. We chose musical rather than linguistic stimuli for this phase so as not to influence responding during the test phase.

- Baillargeon R, Graber M, DeVos J, Black J. Why do young infants fail to search for hidden objects? Cognition. 1990;36:255–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict H. Early lexical development: Comprehension and production.

Journal of Child Language. 1979;6:183–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Journal of Child Language. 1979;6:183–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Eimas PD, Miller JL. Contextual effects in infant speech perception. Science. 1980;209:1140–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eimas PD, Siqueland ER, Jusczyk PW, Vigorito J. Speech perception in infants. Science. 1971;171:303–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howarth CI, Ellis K. The relative intelligibility threshold for one’s own name versus other names. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1961;13:236–240. [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher J. The origins of language comprehension. In: Solso RL, editor. Theories in cognitive psychology. New York: Wiley; 1974. pp. 331–368. [Google Scholar]

- Jusczyk PW, Aslin RN. Infants’ detection of the sound patterns of words in fluent speech. Cognitive Psychology. in press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jusczyk PW, Cutler A, Redanz N. Infants’ preference for the predominant stress pattern of English words. Child Development. 1993;64:675–687.

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Jusczyk PW, Friederici AD, Wessels J, Svenkerud VY, Jusczyk AM. Infants’ sensitivity to the sound patterns of native language words. Journal of Memory and Language. 1993;32:402–420. [Google Scholar]

- Jusczyk PW, Pisoni DB, Mullennix J. Some consequences of stimulus variability on speech processing by 2-month-old infants. Cognition. 1992;43:253–291. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemler Nelson DG, Jusczyk PW, Mandel DR, Myers J, Turk A, Gerken LA. The headturn preference procedure for testing auditory perception. Infant Behavior and Development. 1995;18:111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl PK. Speech perception in early infancy: Perceptual constancy for spectrally dissimilar vowel categories. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1979;66:1668–1679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl PK, Williams KA, Lacerda F, Stevens KN, Lindblom B. Linguistic experience alters phonetic perception in infants by six months of age.

Science. 1992;255:606–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Science. 1992;255:606–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Leslie AM, Keeble S. Do six-month-olds perceive causality? Cognition. 1987;25:265–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney B. The competition model. In: MacWhinney B, editor. Mechanisms of language acquisition. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1987. pp. 249–308. [Google Scholar]

- Mehler J, Jusczyk PW, Lambertz G, Halsted L, Bertoncini J, Amiel-Tison C. A precursor of language acquisition in young infants. Cognition. 1988;29:143–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moray N. Attention in dichotic listening: Affective cues and the influence of instruction. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1959;11:56–60. [Google Scholar]

- Pinker S. Language learnability and language development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Starkey P, Spelke ES, Gelman R. Numerical abstraction by human infants. Cognition. 1990;36:97–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trehub SE. The discrimination of foreign speech contrasts by infants and adults.

Child Development. 1976;47:466–472. [Google Scholar]

Child Development. 1976;47:466–472. [Google Scholar] - Van Lancker D. Personal relevance and the human right hemisphere. Brain and Cognition. 1991;17:64–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werker JF, Tees RC. Cross-language speech perception: Evidence for perceptual reorganization during the first year of life. Infant Behavior and Development. 1984;7:49–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wood N, Cowan N. The cocktail party phenomenon revisited: How frequent are attention shifts to one’s own name in an irrelevant auditory channel? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. in press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynn K. Addition and subtraction by human infants. Nature. 1982;358:749–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Didactic games for knowledge of sounds and letters | Methodological development for the development of speech (preparatory group) on the topic:

IF THERE IS NOTHING TO DO IN THE EVENING

Didactic game "Name the word"

Purpose: To exercise children in finding words for a given sound.

Description: Option 1: The host invites the children to take turns naming words for a certain sound (which sound, the host determines before the game or the children choose). The children take turns saying the words.

Option 2: For more interest, you can offer to play for cookies (small sweets, marmalade, etc.) In front of each child is a plate with the same amount of sweets. There is an empty plate in the center of the table. Children take turns saying words with the correct sound. The child who does not name the word shifts one cookie from his plate to a common plate in the center of the table. The one with the most sweets left wins.

Option 3: You can play for chips. For each word, the driver gives out a chip (for example, counting sticks or any small toys). The player with the most chips wins. You can offer some kind of encouragement as a reward: candy, watch your favorite cartoon, read a fairy tale. Encouragement is negotiated in advance.

Didactic game "Chain of words"

Purpose: To exercise children in inventing words for a given sound.

Description: Option 1: The first player says any word. The next player comes up with a word that sounds like the end of the first player's word. Etc. (cat - cake - tank - pan - apple - sheep - chicken, etc.) An adult monitors the correct naming of words.

Option 2: This game can be played by writing down your word. The first player (or the leader - an adult) writes down the word on a piece of paper and passes the sheet to the next in turn. That player writes down his word on the sound with which the previous word ended and passes the sheet of paper to the next. The duration of the game is 15 - 20 minutes (depending on the perseverance of the children). An adult monitors the correct spelling of words and the implementation of the rules of the game (name words for the last sound of the previous word).

Didactic game "Who will write more words"

Purpose: To exercise children in finding words for a certain sound (or with a certain sound). Exercise in finding the place of sound in a word.

Description: Option 1: In front of each child is a sheet of paper, preferably in a wide ruler, and a simple pencil. The driver determines the time of the game (15 - 20 minutes), during this time the children will write down the words to the sound proposed by the driver. At the end of the game time, the driver - an adult checks the spelling of words (spelling errors are not taken into account, but are corrected with the child so that the latter tries to visually remember the correctly spelled word). At the end of the game, the number of written words for each child is counted. The winner is the player who wrote the most words.

Option 2: The speaker suggests writing down words with a given sound and emphasizing the sound in the word, thereby determining its place in the word (at the beginning, middle, end of the word). The one with the most words written wins.

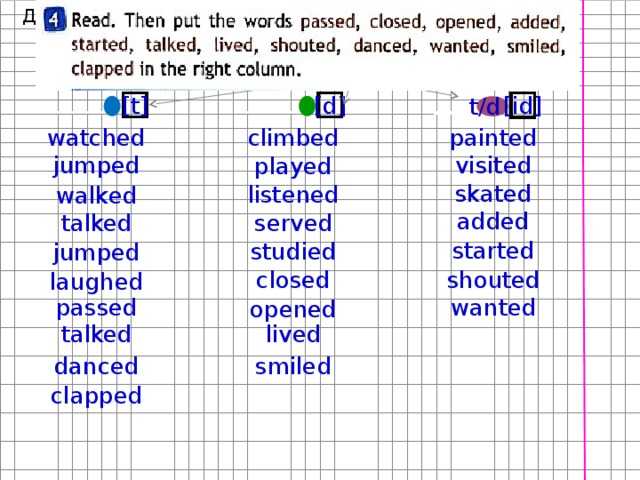

Didactic game "Disassemble the word into sounds"

Purpose: To exercise children in finding vowel sounds, in the ability to identify soft and hard consonant sounds by ear, using the reading of syllables and words.

Description: An adult writes 6-10 words on a piece of paper and invites the child to parse the words into sounds. First, the whole word is read. When parsing a word, it is easier to find vowel sounds first (they stretch during pronunciation, nothing interferes in the mouth, they are indicated by a red circle). Next, you should invite the child to read the first syllable and hear the first consonant sound - how it sounds when reading it with a vowel sound. A soft consonant is indicated by a green circle, a hard consonant by a blue circle.

Didactic game "Find the sound in the word"

Purpose: To exercise children in finding the place of the sound in the word.

Description: Option 1: At the beginning of the game, the sound that children will look for in words is determined. An adult calls a word with the right sound, the child looks for its place in the word (at the beginning, middle, end of the word).

Option 2: You can complicate the task (if the child can easily cope with the first version of the game), and invite the child to name which sound counts. For example, the sound "SH" is searched for. Shshshum - the first; marchshsh - fourth; ourssh - third, etc.

For example, the sound "SH" is searched for. Shshshum - the first; marchshsh - fourth; ourssh - third, etc.

Didactic game "Make a word"

The game requires letters of the alphabet, preferably 2-3 sets. Letters cut out of paper (cardboard) are also suitable: vowels - red, soft consonants - green, hard consonants - blue.

Purpose: To consolidate knowledge of letters. Exercise in the ability to hear soft and hard sounds, as well as vowel sounds.

Description: Option 1: The leader calls the word (the word is pronounced clearly, highlighting all the sounds), the child puts this word in letters on the table. The driver checks the spelling of the word by sounds. For example, juice - JUICE; linden - LINDE, etc.

Option 2: Children independently lay out different words, trying not to repeat themselves. The driver checks the spelling of the words.

Didactic game "Disassemble words into syllables"

Purpose: To exercise children in dividing words into syllables. To consolidate knowledge of the rule: how many vowels in a word, so many syllables.

To consolidate knowledge of the rule: how many vowels in a word, so many syllables.

Description: Option 1: An adult calls the word, the child divides it into syllables by ear, pronouncing the word in parts. (Machine - machine-shi-na, doll - doll-la, etc.)

Option 2: An adult writes 6-8 words on a piece of paper and invites the child to parse the words into syllables. First, the whole word is read. The number of vowel sounds in a word is determined. The word is pronounced syllable by syllable, separating the syllables with a vertical line and underlining each syllable as it is pronounced.

CAR DOLL

Option 3: Children lay out a word from a set of letters and divide it into syllables, pushing the word apart.

Web mastering.

Web mastering.