Phonics what is

What is phonics? | ReadwithPhonics

What is phonics? (UK)

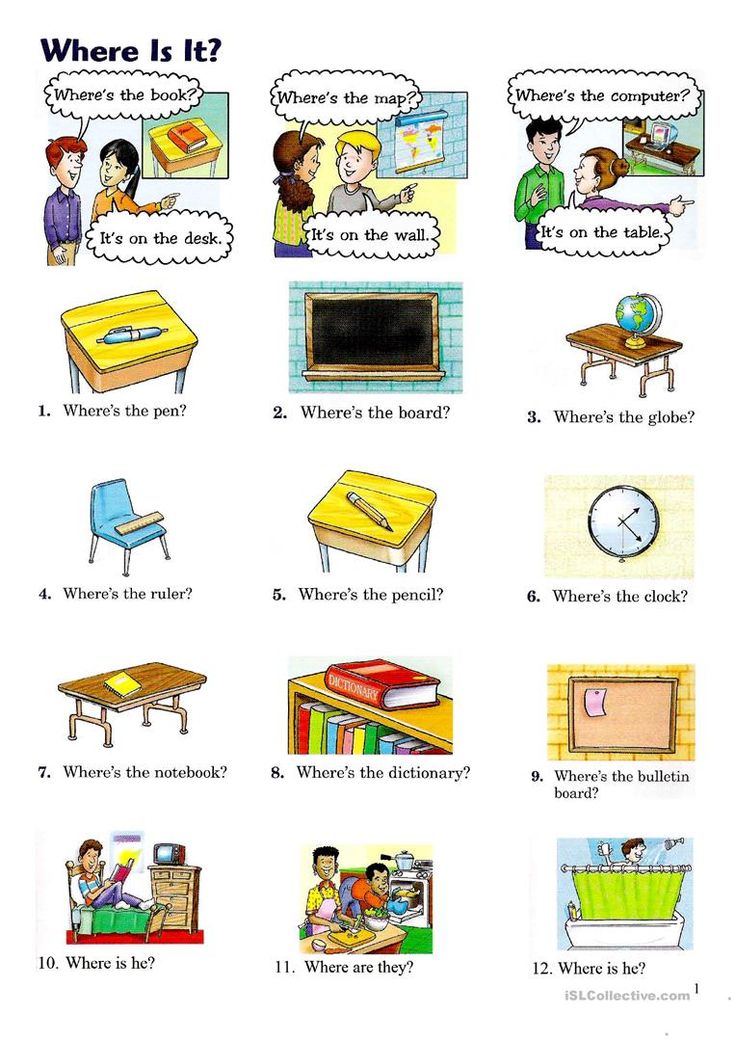

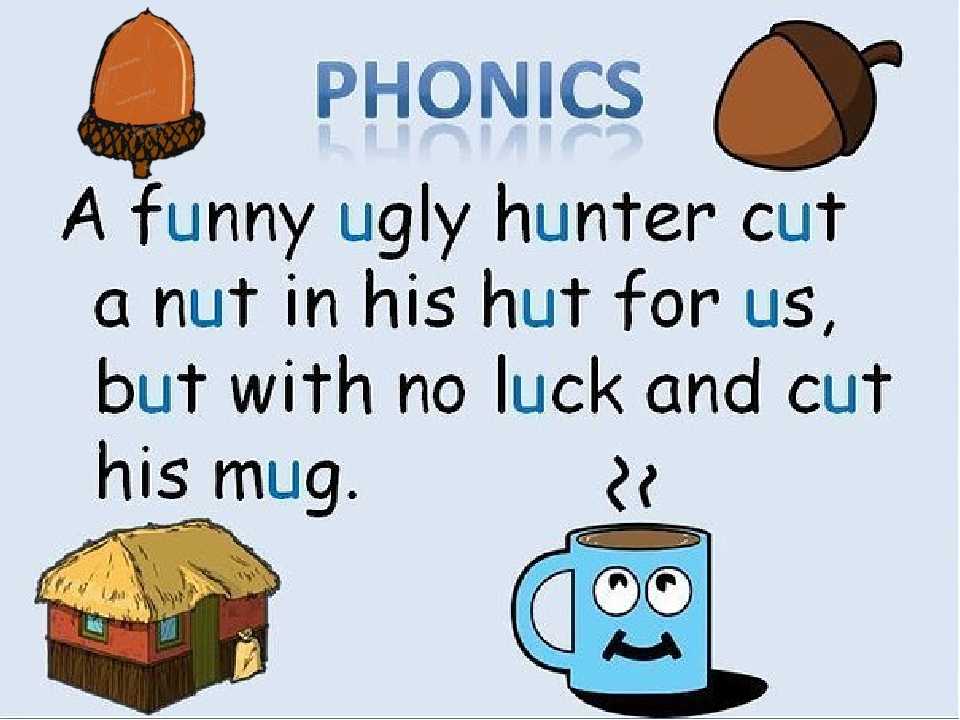

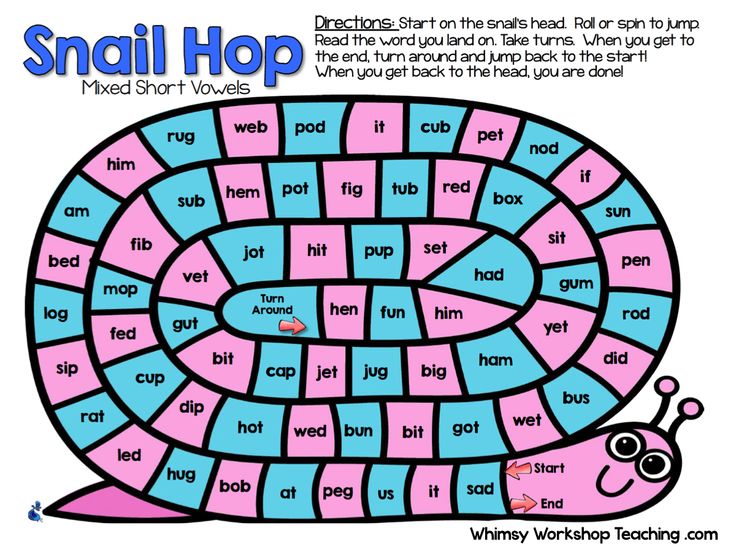

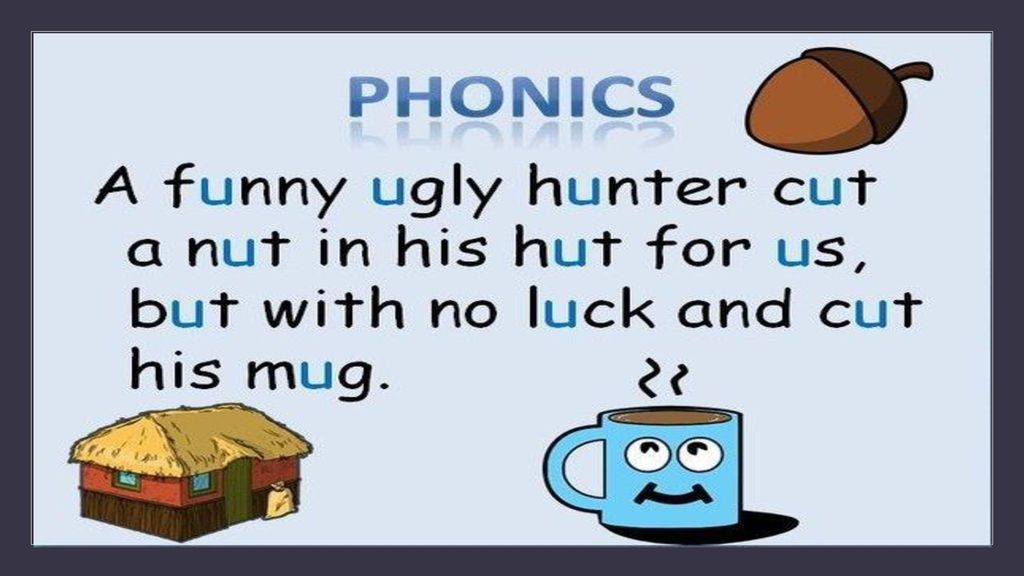

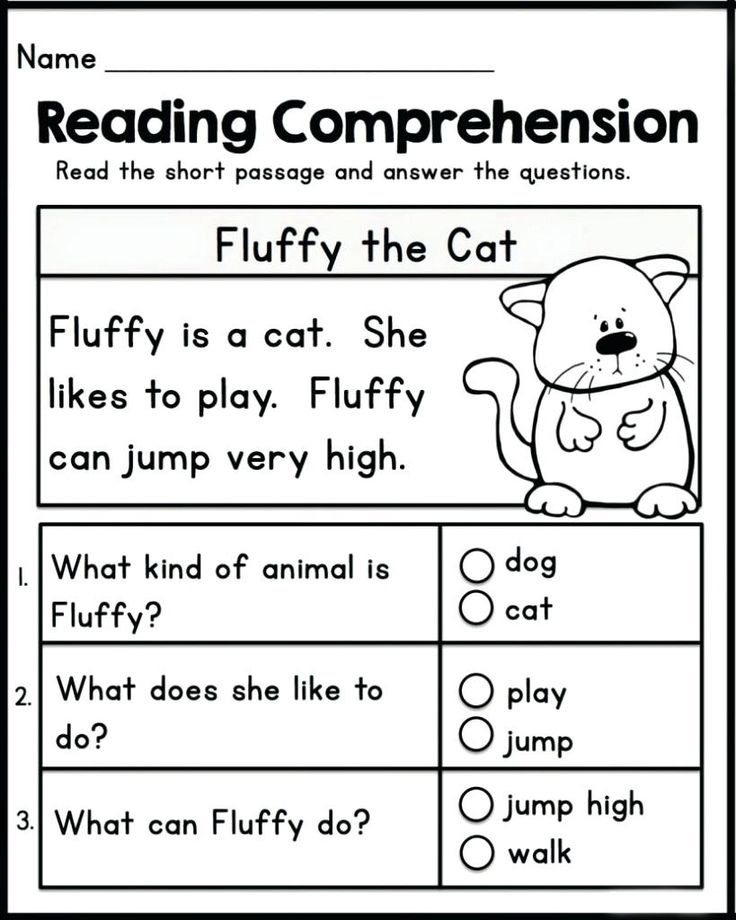

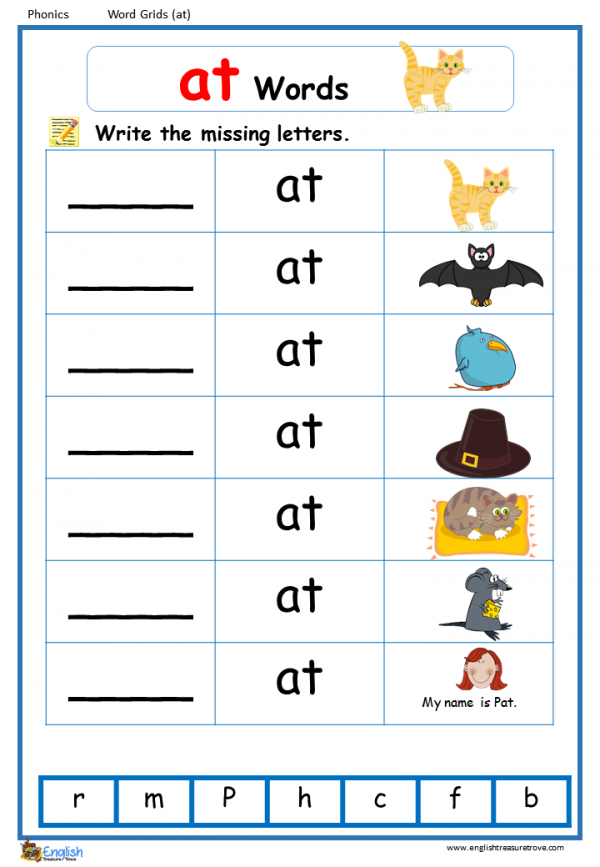

Phonics is a method of learning to read. Phonics works by breaking each word up into it’s individual sounds before blending those sounds back together to make the word. Children learn to 'decode' words by breaking it down into sounds rather than having to memorise 1,000's of words individually. Research has shown that phonics, when taught correctly, can be the most effective way of teaching children to learn to read. Sounds are taught from easiest to hardest: starting with single letter sounds and then moving on to two letters making a sound and then three and so on. Learning phonics and learning to read is one of the most important stepping stones in early education as it gives your child the skills they need to move forward in every subject, you simply cannot progress without it.

All over the UK (and now in some primary schools in New Zealand and Australia), schools are using phonics as their preferred method of learning to read. Phonics was first introduced in the UK in 2012 and since then has had great results. Unlike learning words by sight and shape, phonics has provided students with the ability to learn a skill that enables them to work out how to read almost any word in the English language.

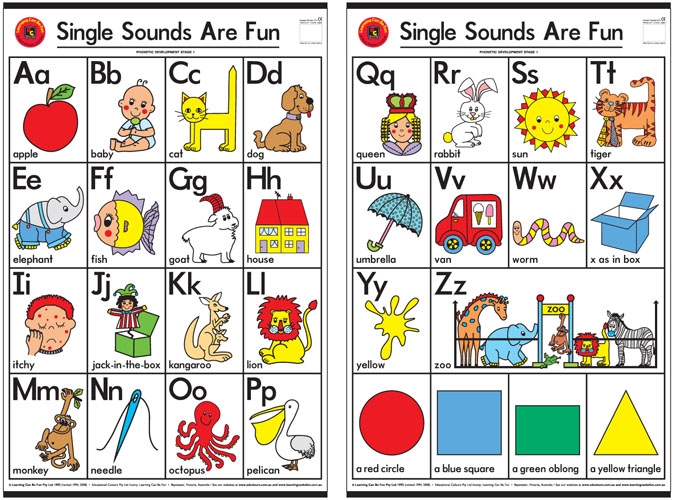

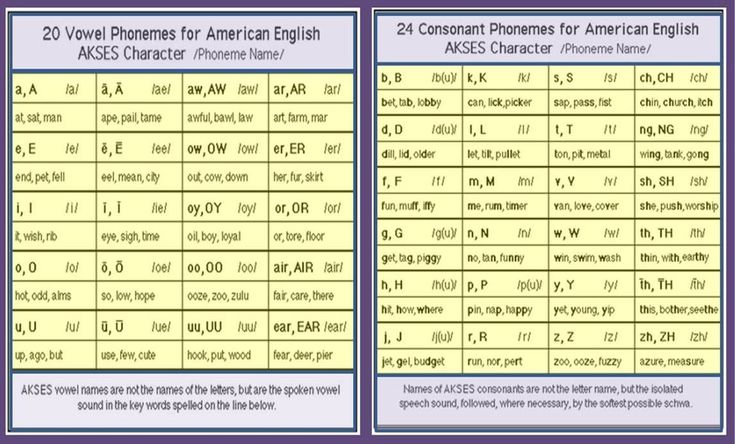

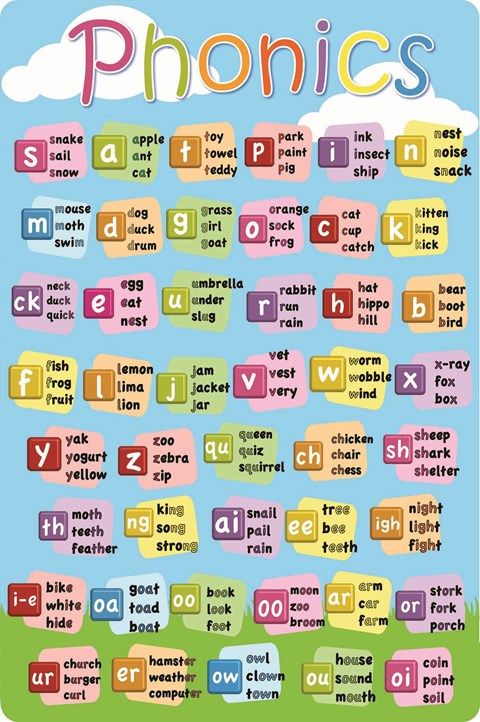

The alphabet is a great place to start learning phonics as if you learn the simple 26 letter sounds of the alphabet you will be well on your way to learning all 44 sounds. Our alphabet phonics song is a good way to learn all of the alphabet letter sounds:

Phonics Terminology

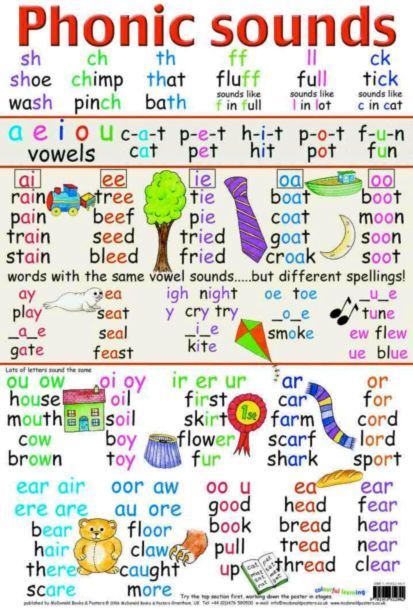

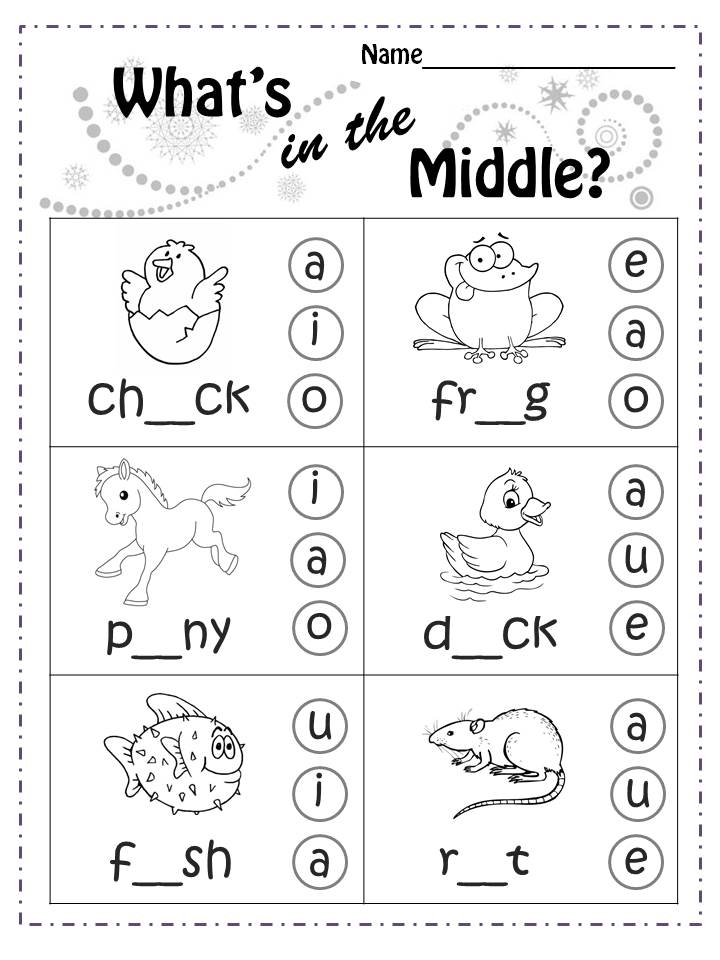

To start to understand phonics terminology its important to understand the difference between sounds that are said and sounds that are written. A sounds that is written is called a grapheme and a sound that is said is called a phoneme. Phoneme and grapheme recognition come hand in hand as your child starts to learn phonics they will make an association between the two. For example when you write the letter ‘a’ this is a grapheme, it makes the short ‘a’ sound (like in ‘ant’), but when the short ‘a’ is said this is the phoneme.

For example when you write the letter ‘a’ this is a grapheme, it makes the short ‘a’ sound (like in ‘ant’), but when the short ‘a’ is said this is the phoneme.

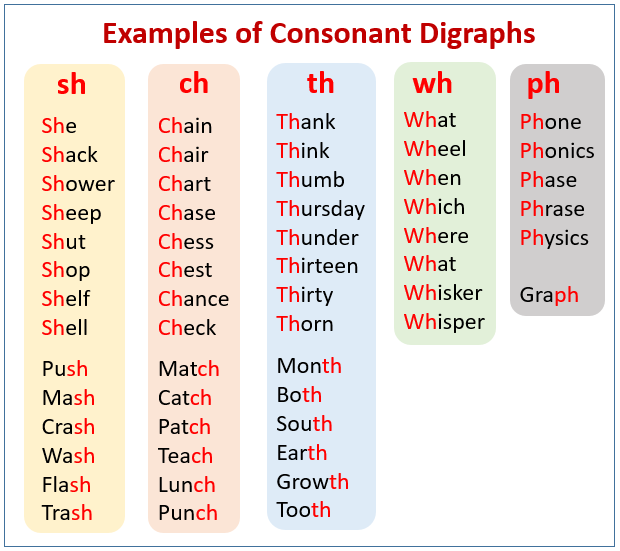

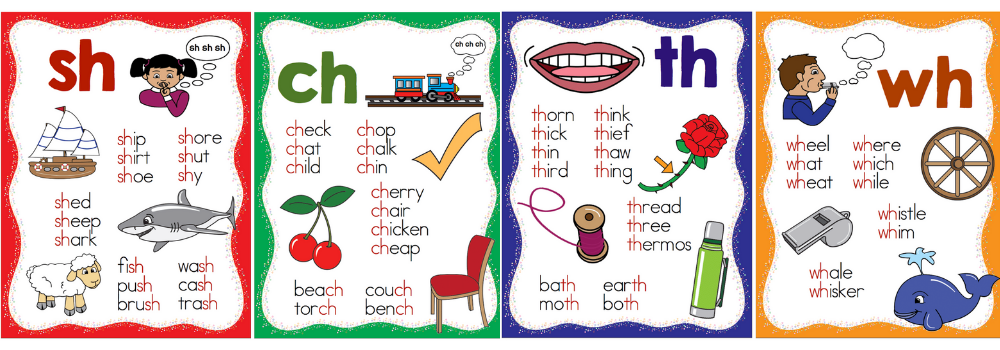

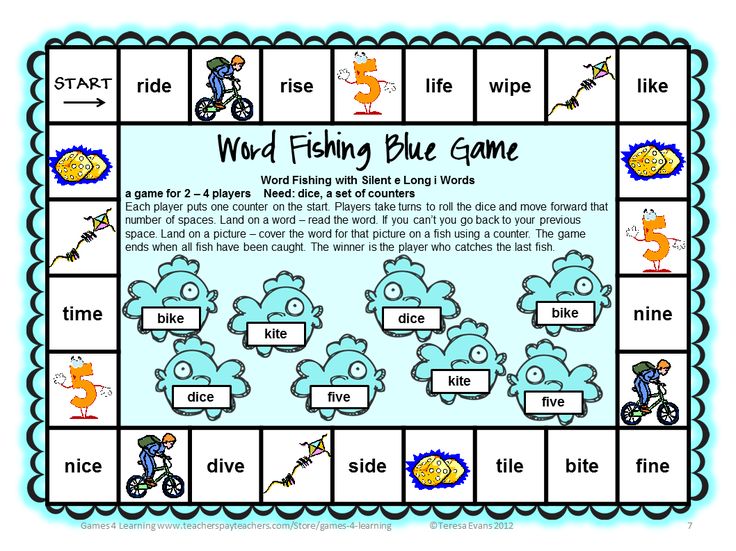

The 44 sounds of the english language are not just made by up by single letters sounds, two letters can work together, sometimes three! These are know as: digraphs, trigraphs and split digraphs. A digraph is made up of two letters working together to make the same sound, for example ‘oa’ like in ‘boat’. Trigraphs are three letters working together to make the same sound, for example ‘air’ in ‘hair’. A split digraph is two letters that work together to make the same sound but are separated by another letter for example ‘i_e’ in ‘bike’.

There are some combinations of letters that sound the same but are spelt differently for example, ‘oa’ in boat an the ‘o_e’ in ‘bone’, both words have the ‘o’ sound but different combinations of letters are used. We call this alternative spelling combinations.

The sound that most children struggle to spot the most when breaking down words into its individual sounds is the 'split digraph'. Like a normal digraph, this is when two letters work together to make one sound, however with a split digraph, they are separated and have a letter in the middle.

Like a normal digraph, this is when two letters work together to make one sound, however with a split digraph, they are separated and have a letter in the middle.

E.g. cake, make, bike, phone

Below is a little phonics codebreaker to help you remember the terminology.

The phonics codebreaker

Phoneme - a sound as it is said

Grapheme - a sound that is written

Digraph- two letters that work together to make the same sound

Trigraph - Three letters that work together to make the same sound

Split digraph - Two letters that work together to make the same sound, separated by another letter

If you are unsure of letter sounds, download Read with Phonics Parent Guide

What is the Phonics Screening Check?

The Phonics Screening check is a compulsory assessment that all children in the UK take at the end of Year 1. It is designed to make sure students have developed phonic decoding skills to an appropriate standard. It was first introduced in 2012 and has shown promising results in raising attainment in literacy and reading.

It was first introduced in 2012 and has shown promising results in raising attainment in literacy and reading.

The Phonics Screening check is made of up of 40 words, 20 ‘real words’ and 20 ‘pseudo words’. Each child reads the words and the teacher observes.

The question is, how important is the screening check to the child?

It can benefit the child by giving them a solid foundation of which to progress through school. If they have passed the screening it means they have phonic decoding skills that they can use to decode most words.

The importance of the check should be to make sure that a child is ready to progress into Year 2. The simple fact is, if a child can read, passing the check is easy.

Phonics in the USA

In America, phonics is taught a little differently to the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Australia.

Below are some of the key differences:

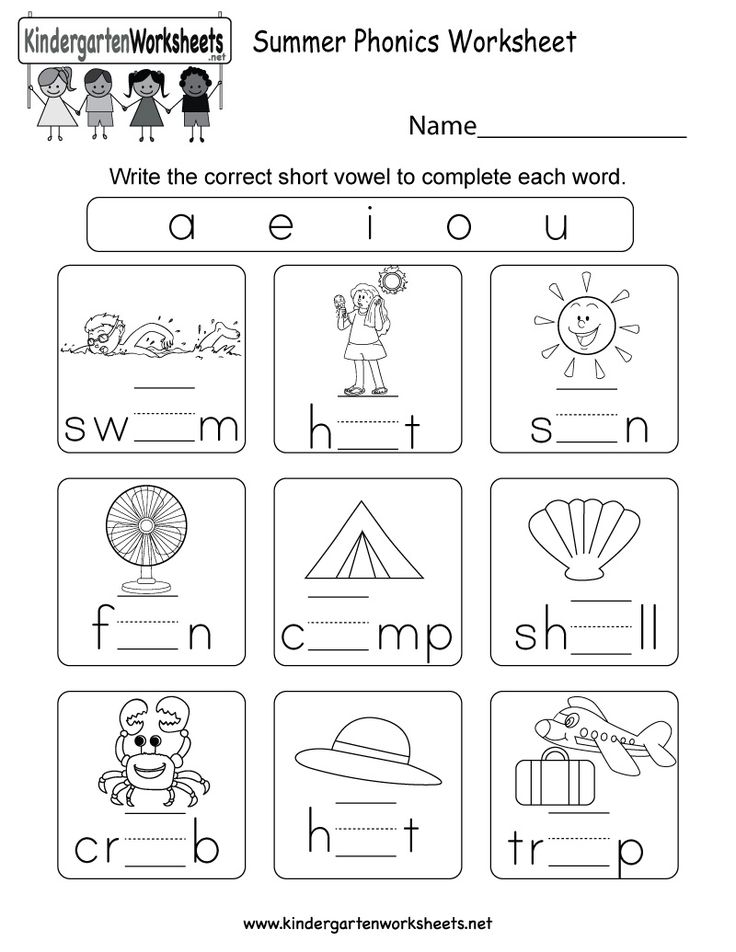

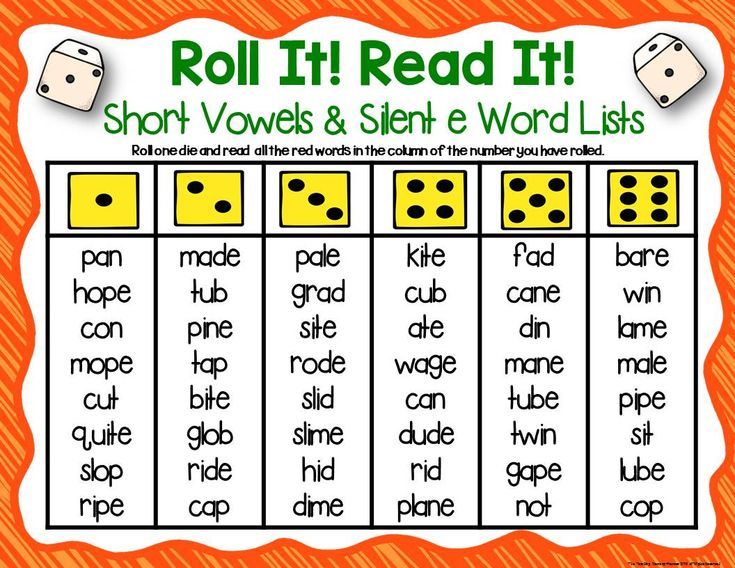

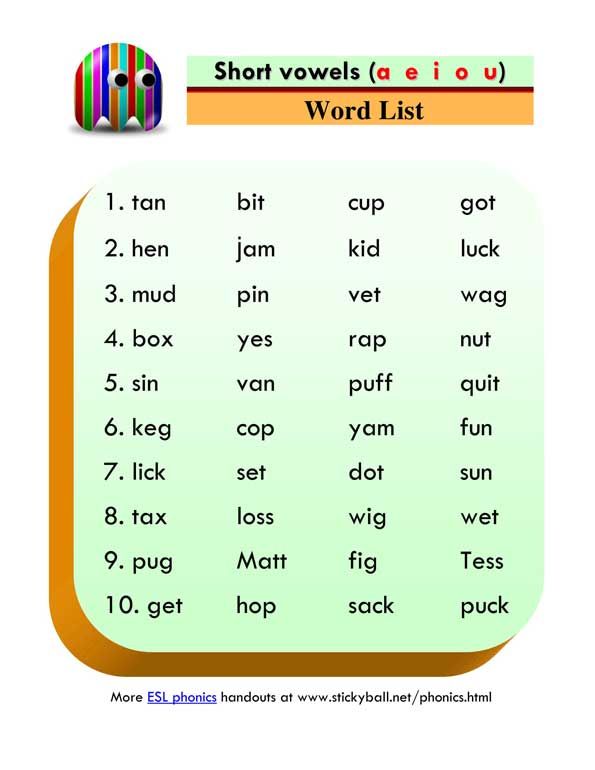

Short and Long Vowels: When a vowel (a,e,i,o,u) is followed by one consonant, that vowel is usually short for example ‘e’ makes the ‘e’ sound in ‘get’.

A vowel is long when it says its own name. When a single vowel is at the end of a word or syllable, it usually makes the long vowel sound, as in ‘go’ and ‘paper’.

Silent ‘e’: When ‘e’ is the last letter in a word and there is only one other vowel in that word, the first vowel usually says its own alphabet name and the ‘e’ is silent, like in ‘cake’.

Consonant digraphs and blends: In a consonant digraph, two consonants work together to form one sound that isn’t like either of the letters it is made from.

E.g.

ship

think

Consonant blends are groups of two or three consonants whose individual sounds can be heard as they blend together.

E.g.

clam

scrub

grasp.

Phonics in Australia

Phonics in Australia is taught much the same as in United Kingdom. The terminology and methods of teaching mirror that of synthetic phonics programs taught in the UK.

Phonics in New Zealand

Over the past decade, New Zealand’s educational system has favoured the whole language approach to reading. This teaches children to learn new words based on context: for example, by encouraging them to guess a word in the book they’re reading based on the story, pictures, or words around it.

This teaches children to learn new words based on context: for example, by encouraging them to guess a word in the book they’re reading based on the story, pictures, or words around it.

With a whole reading approach, children don’t learn to break down sounds individually, but to take words at face value and associate them with prior knowledge. If a child sees the word ‘dog’ written enough times with a picture of a dog he or she will then associate that word, in it’s entirety, with the idea of a dog.

But phonics is making a come back! More teachers are using phonics as a way to learn to read instead of a whole reading approach, as used by teachers in the UK and Australia.

What Is Phonics, Explicit Phonics Instruction :: Read Naturally, Inc.

What Is Phonics?

Phonics is "a system of teaching reading that builds on the alphabetic principle, a system of which a central component is the teaching of correspondences between letters or groups of letters and their pronunciations" (Adams, 1990, p. 50). Decoding is the process of converting printed words to spoken words. Readers use phonics skills, beginning with letter/sound correspondences, to pronounce words and then attach meaning to them. As readers develop, they apply other decoding skills, such as recognizing word parts (e.g., roots and affixes) and the ability to decode multisyllable words. Students also learn to apply decoding skills to irregular words that are almost decodable.

50). Decoding is the process of converting printed words to spoken words. Readers use phonics skills, beginning with letter/sound correspondences, to pronounce words and then attach meaning to them. As readers develop, they apply other decoding skills, such as recognizing word parts (e.g., roots and affixes) and the ability to decode multisyllable words. Students also learn to apply decoding skills to irregular words that are almost decodable.

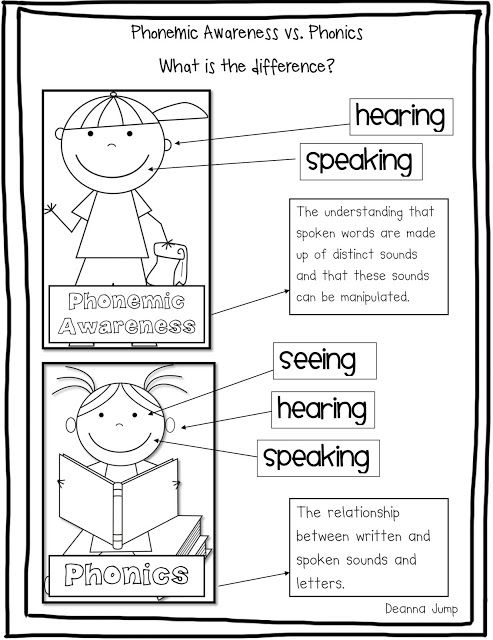

Phonemic awareness and phonics are not the same, but instruction in phonemic awareness and phonics tends to overlap. As students begin to transition to phonics, they learn the relationship between a phoneme (sound) and grapheme (the letter(s) that represent the sound) in written language. Phonemic awareness instruction improves phonics skills, and phonics skills improve phonemic awareness (Lane and Pullen, 2004).

Read Naturally programs for teaching phonics

Key Concepts

Implicit vs. Explicit Phonics Instruction

There are two approaches to phonics instruction:

- Systematic, explicit phonics instruction: Sound/spelling correspondences are taught directly and systematically.

- Incidental, implicit phonics instruction: Sound/spelling correspondences are inferred from reading whole words and introduced as students encounter them in text.

The National Reading Panel (2000) conducted a meta-analysis to review and evaluate research on the effectiveness of various approaches for teaching children to read. Their findings showed that students who received systematic and explicit phonics instruction were better readers at the end of instruction than students who received non-systematic or no phonics instruction (Ehri, 2006; Armbruster, Lehr, and Osborn, 2001).

The National Reading Panel also stated that "the hallmark of systematic phonics programs is that they delineate a planned, sequential set of phonic elements, and they teach these elements, explicitly and systematically" (2000, p. 2-99).

Regular and Irregular Words

Word recognition involves two types of words: regular words (the words which students can decode by sounding them out) and irregular words (the words students cannot completely decode by sounding them out). For example:

For example:

| Regular Words (decodable) | Irregular Words (not decodable) |

|---|---|

| hot | they |

| black | was |

| plain | said |

In some programs, regular words that can be decoded are called sound-out words. Irregular words that must be learned by memory are called spell-out words.

In the beginning stages of phonics instruction, an irregular word can also be a word that the student does not yet have the specific phonics skills to read (Carnine et al., 2006). For example, before a student learns that together the letters k-n say /n/, the words knew and know are irregular words. Once a student learns that together the letters k-n say /n/, these words are no longer irregular.

High-Frequency Words

Another important emphasis of phonics and word recognition is learning high-frequency words. Eight words account for 18% of all the words students typically read and write, 25 words for 33%, 100 words for 50%, and 300 words for 65% (Fry, Fountoukidis, & Kress, 2000). High-frequency words can be regular or irregular.

High-frequency words can be regular or irregular.

First 200 High-Frequency Words

Multisyllabic Words

The average number of syllables in the words students read increases steadily in the primary grades. In fifth grade and beyond, knowing how to decode multisyllabic words is essential, because most of the words students encounter in print are words of 7 or more letters and two or more syllables (Nagy and Anderson, 1984).

Systematic and explicit instruction in decoding multisyllabic words is important. Explicit instruction in how to decode multisyllabic words is most successful for students who can already accurately decode single-syllable words and accurately pronounce all of the typical vowel combinations. However, the ability to decode single-syllable words does not necessarily transfer to reading multisyllabic words (Just & Carpenter, 1987).

Research shows that students can be taught to flexibly segment multisyllabic words into spelling units (chunks) that can be decoded (Bhattacharya and Ehri, 2004; Archer et al. 2003, 2006). Students need two key skills to successfully decode multisyllabic words:

2003, 2006). Students need two key skills to successfully decode multisyllabic words:

- Pronouncing Affixes: About 80% of all words have one or more affixes—prefixes or suffixes (Cunningham, 1998). Affixes are worth teaching, because there are a limited number of them, they occur frequently, and suffixes are especially consistent across words (Shefelbine and Newman, 2004). Students who have learned to read prefixes and suffixes by sight (e.g., re-, -tion, ex-, -sion, -ism, ad-, -sive) and are able to pronounce them in isolation are more successful at decoding multisyllabic words.

Common affixes (prefixes and suffixes) - Pronouncing Open and Closed Syllables: We know that open and closed syllables make up almost 75% of syllables in English words (Stanback, 1992). Research has shown that there is a significant relationship between students’ sight knowledge of open and closed syllables and students’ ability to read multisyllabic words (Shefelbine, Lipscomb, and Hern, 1989).

The Importance of Developing Automaticity in Phonics

Research tells us that in order to become fluent readers, students need to learn to decode unknown words accurately and automatically. Students who must use all of their mental energy to sound out the words are not able to focus on the meaning of what they are reading (LaBerge and Samuels, 1974). In fact, research findings show that those students who have not developed automaticity by the beginning of second grade are at risk for reading failure (Berninger et al., 2003, Berninger et al., 2006).

Most phonics programs teach students to decode accurately, but learning phonics does not guarantee that students are able to decode words automatically. Students must develop the ability to read words quickly and effortlessly.

Progression of Phonics Skills

Children typically progress through a sequence of identified phonics skills as they learn to read and spell—whether they learn slowly or quickly (Ehri, 2004; Moats, 1995; Templeton and Bear, 1992; Treiman and Bourassa, 2000).

Here is a simple sequence of phonics elements for teaching sound-out words that moves from the easiest sound/spelling patterns to the most difficult:

- Consonants & short vowel sounds

- Consonant digraphs and blends

- Long vowel/final e

- Long vowel digraphs

- Other vowel patterns

- Syllable patterns

- Affixes

Read Naturally Programs for Teaching Phonics

Read Naturally offers several programs that are based on the research about phonics and word recognition described above.

| Signs for SoundsTM Teacher-led instruction for teaching regular phonetic spelling patterns and regular and irregular high-frequency words through spelling. Focuses on spelling and phonics with additional support for phonemic awareness. Learn more about Signs for Sounds Signs for Sounds samples |

| Read Naturally® GATE Teacher-led instruction for small groups of early readers.  Focuses on phonics, high-frequency words, and fluency instruction with additional support for phonemic awareness and vocabulary. Focuses on phonics, high-frequency words, and fluency instruction with additional support for phonemic awareness and vocabulary.Learn more about Read Naturally GATE Read Naturally GATE samples |

| Read Naturally® Live A mostly independent, cloud-based program with built-in audio support. The Phonics series focuses on phonics and fluency with additional support for phonemic awareness and vocabulary. Learn more about Read Naturally Live Video: Working through phonics stories (Note: This video walks through the steps in the Read Naturally Live Phonics series, but the steps in the Read Naturally Encore Phonics series are essentially the same.) |

Bibliography

Adams, M. J. (1990). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Archer, A., M. Gleason, and V. Vachon. (2003). Decoding and fluency: Foundation skills for struggling older readers. Learning Disability Quarterly, 26, pp. 89-101.

Learning Disability Quarterly, 26, pp. 89-101.

Archer, A., M. Gleason, and V. Vachon. (2006). REWARDS: Reading excellence: Word attack and rate development strategies. Longmont, CO: Sopris West.

Armbruster, Lehr, and Osborn. (2001). Put reading first: The research building blocks for teaching children to read. Jessup, MD: National Institute for Literacy.

Berninger, V. W., K. Vermeulen, R. B. Abbott, D. McCutcheon, S. Cotton, J. Cude, S. Dorn, and T. Sharon. (2003). Comparison of three approaches to supplementary reading instruction for low-achieving second-grade readers. Language, Speech, & Hearing Services in Schools, 34, pp. 101-116.

Berninger, V. W., R. B. Abbott, K. Vermeulen, and C. M. Fulton. (2006). Paths to reading comprehension in at-risk second-grade readers. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39, pp. 334-351.

Bhattacharya, A., and L. Ehri. (2004). Graphosyllabic analysis helps adolescent struggling readers read and spell words. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37, pp. 331-348.

Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37, pp. 331-348.

Carnine, D. W., J. Silbert, E. J. Kame’enui, S. G. Tarver, and K. Jungjohann. 2006. Teaching struggling and at-risk readers. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Cunningham, P. M. (1998). The multisyllabic word dilemma: Helping students build meaning, spell, and read “big” words. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 14(2), pp. 189-218.

Ehri, L. (2004). Teaching phonemic awareness and phonics. In P. McCardle and V. Chhabra (eds.). The voice of evidence in reading research, pp. 153-186. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing.

Ehri, L. (2006). More about phonics: Findings and reflections. In K. A. Dougherty Stahl and M. C. McKenna (eds.), Reading research at work: Foundations of effective practice. New York: Guilford.

Fry, E. B., Fountoukidis, D. L., & Kress, J. E. (2000). The reading teacher’s book of lists, 4th ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Honig, B. , L. Diamond, and L. Gutlohn. (2013). Teaching reading sourcebook, 2nd ed. Novato, CA: Arena Press.

, L. Diamond, and L. Gutlohn. (2013). Teaching reading sourcebook, 2nd ed. Novato, CA: Arena Press.

Just, M. A., and P. A. Carpenter. (1987). The psychology of reading and language comprehension. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

LaBerge, D., & Samuels, S. J. (1974). Toward a theory of automatic information processing in reading. Cognitive Psychology, 6, pp. 292–323.

Lane, H. B., and P. C. Pullen. (2004). A sound beginning: Phonological awareness assessment and instruction. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Moats, L. C. (1995). Spelling: Development, disability, and instruction. Baltimore, MD: York Press.

Nagy,W. E., and R. C. Anderson. (1984). How many words are there in printed school English? Reading Research Quarterly, 19, pp. 304-330.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Shefelbine, J., L. Lipscomb, and A. Hern. (1989). Variables associated with second, fourth, and sixth grade students’ ability to identify polysyllabic words. In S. McCormick and J. Zutell (eds.), Cognitive and social perspectives for literacy research and instruction, pp. 145-149. Chicago: National Reading Conference.

Shefelbine, J., and K. Newman. (2004). SIPPS: Systematic instruction in phoneme awareness, phonics, and sight words. Challenge level, polysyllabic decoding, 2nd ed. Oakland, CA: Developmental Studies Center.

Stanback, M. L. (1992). Syllable and rime patterns for teaching reading: Analysis of a frequency-based vocabulary of 17,602 words. Annals of Dyslexia, 42, pp. 196-221.

Templeton, S. & Bear, D. (eds.) (1992). Development of orthographic knowledge and the foundation of literacy. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Treiman, R. & Bourassa, D. (2000). The development of spelling skill. Topics in Language Disorders, 20, 1-18.

& Bourassa, D. (2000). The development of spelling skill. Topics in Language Disorders, 20, 1-18.

is ... What is the phonetics of the Russian language?

Phonetics is a branch of the science of language, the subject of which is sound. Sound is the basic unit of language along with the word and the sentence, but unlike them, it has no meaning by itself.

Phonetics and sound

Sounds play an important semantic role in the language. They form the word phonetically, creating its external sound shell.

Here is Wikipedia's definition of phonetics:

Phonetics (from Greek φωνή - “sound”, φωνηεντικός - “sound” ) is a branch of linguistics that studies the sounds of speech and the sound structure of the language (syllables, sound combinations, patterns of connecting sounds in a speech chain).

Sounds, combined in different combinations, help to distinguish words in speech. Each word contains a certain number of sounds. Compare:

Compare:

- boron - collection;

- port - sport;

- cat - window;

- helmet — fairy tale

Words differ in the set of sounds and the sequence of their arrangement. Let's observe the words that differ

with one sound

- wagon - flowerpot;

- hike - approach;

- city-garden;

two sounds

- spoon - cover;

- beans - password;

- grease - putty.

In the phonetic appearance of words, we observe a difference in the sequence of sounds:

- variety - torso;

- lace kite;

- box - threshold ([box] - [pair]).

Formation of sounds of language

Phonetics studies each sound from the point of view of acoustics, as a physical object, and articulation - a way of sound formation with the help of human speech organs. Sounds are formed in the speech apparatus when air is exhaled. The speech apparatus includes the larynx with vocal cords, oral and nasal cavities, tongue, lips, and palate.

Sounds are formed in the speech apparatus when air is exhaled. The speech apparatus includes the larynx with vocal cords, oral and nasal cavities, tongue, lips, and palate.

Vowel sounds

In the speech apparatus, the exhaled air passes through the larynx between the tense vocal cords and through the oral cavity, which can change its shape. This is how vowels are formed: [a], [o], [y], [e], [i], [s].

They consist only of voice.

Consonants

Exhaled air can meet an obstruction in the oral cavity in the form of a closure or convergence of the speech organs and exit through the mouth or nose. This is how consonants are formed. They are made up of noise, and some are made up of voice and noise.

Image source: abv-stand.rf

Phonetic position of sound

In speech, all sounds are either in a strong position or in a weak one. In a strong position, the sound is heard clearly. For vowels, a strong position is finding the sound under stress, and a weak one is without stress, for example: position if there are vowels next to it:

beard, gate, hurricane, hand, table, closet, trails .

A weak position for consonants is their location

1. at the end of a word 2. before voiceless consonants

video tutorial “Phonetic transcription”

Video lesson “Phonetic analysis of the word”

Training material

4. 7

7

Average rating: 4.7

Total ratings received: 403.

4.7

Average rating: 4.7

Total ratings received: 403.

The initial stage of learning the Russian language is the study of the phonetic level of the language. In this article, we will consider what phonetics is, what are the features of this section, what are its objects of study.

Definition

Phonetics is a branch of linguistics that considers the linguistic structure of language and speech.

The term "phonetics" of Greek origin, it is translated as "sound", "sound".

Objects of study

Phonetics studies the sounds of speech, their formation and properties; combinations of sounds, features of combining sounds into a single whole; syllables.

The basic unit of phonetics is sound.

In the course of studying this section of linguistics, there is an understanding of how sound is created and what organs are involved in creating sound. Sounds are formed with the help of such speech organs as the oral cavity, nasal cavity, larynx with vocal cords, tongue, lips, palate.

Sounds are formed with the help of such speech organs as the oral cavity, nasal cavity, larynx with vocal cords, tongue, lips, palate.

The phonetics of the Russian language involves considering the characteristics of a sound or combinations of sounds, establishing a connection between sounds and letters, considering the differences between them.

When studying phonetics, there is a brief introduction to certain concepts, which are presented below in the form of a table:

| Term | Definition |

| Sound | smallest unit in phonetics |

| Accent | selection with the help of intensity, intonation of speech of a certain sound in a word, a single phonetic organization |

| Tone | emotional background of speech, which is created using the rhythmic organization of sound |

| Temp | the speed of the speech flow, which is created by pronouncing a certain number of sounds in a fragment of time |

| Syllable | smallest unit of sound chain |

Sounds

Since sound is the basic unit of phonetics, special attention is paid to it.

Phonetics involves the study of sounds and their division into vowels and consonants, which in turn are divided into soft and hard, deaf and voiced.

In speech, sounds are either in a strong position, when the sound is heard clearly, or in a weak position, when a person does not understand which letter to put on a letter. For vowels, a strong position is associated with being under stress, a weak position is associated with the fact that the vowel sound is unstressed.

What have we learned?

Phonetics is a branch of linguistics that considers the linguistic structure of language and speech. Phonetics studies the sounds of speech, their formation and properties; combinations of sounds, features of combining sounds into a single whole; syllables. In the course of studying this section of linguistics, there is an understanding of how sound is created and what organs are involved in creating sound. Phonetics involves the study of such concepts as sound, stress, tone, tempo, syllable.