Previewing reading strategy

3.3: Reading Strategies - Previewing

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID

- 31308

- Athena Kashyap & Erika Dyquisto

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

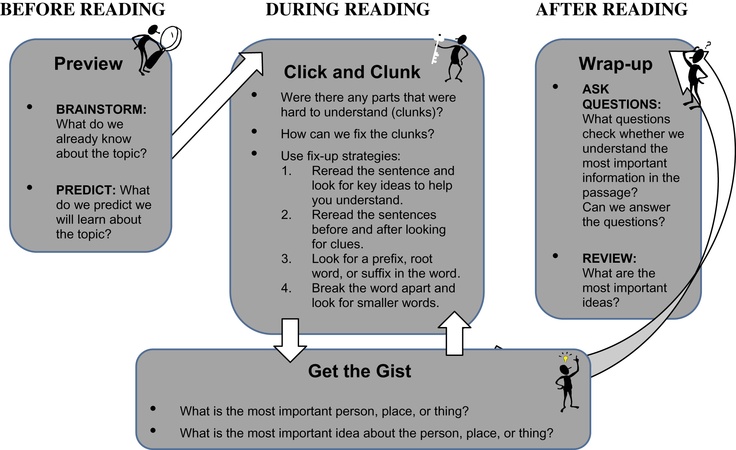

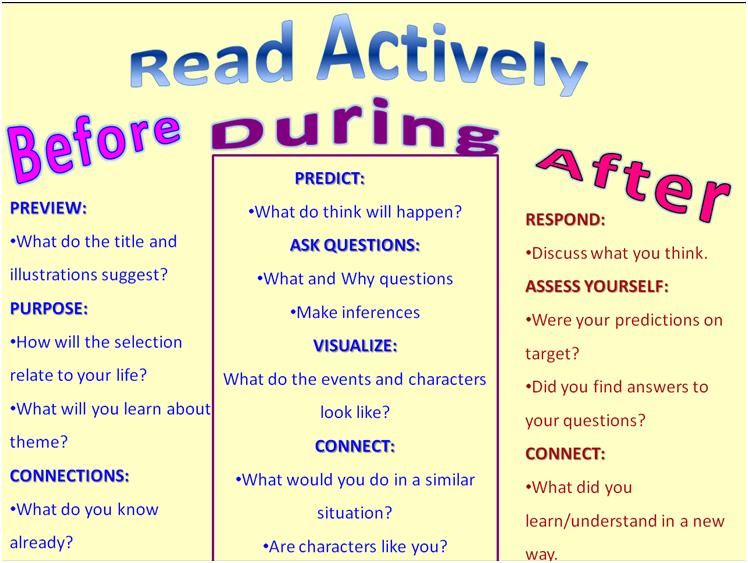

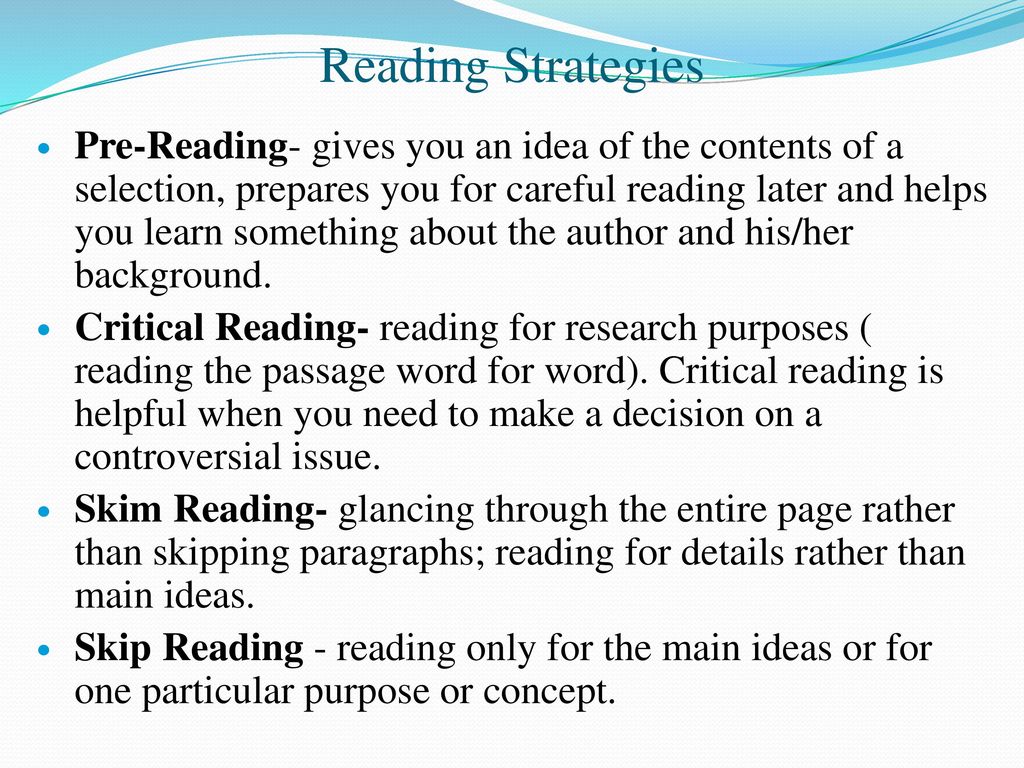

Pre-reading Strategies

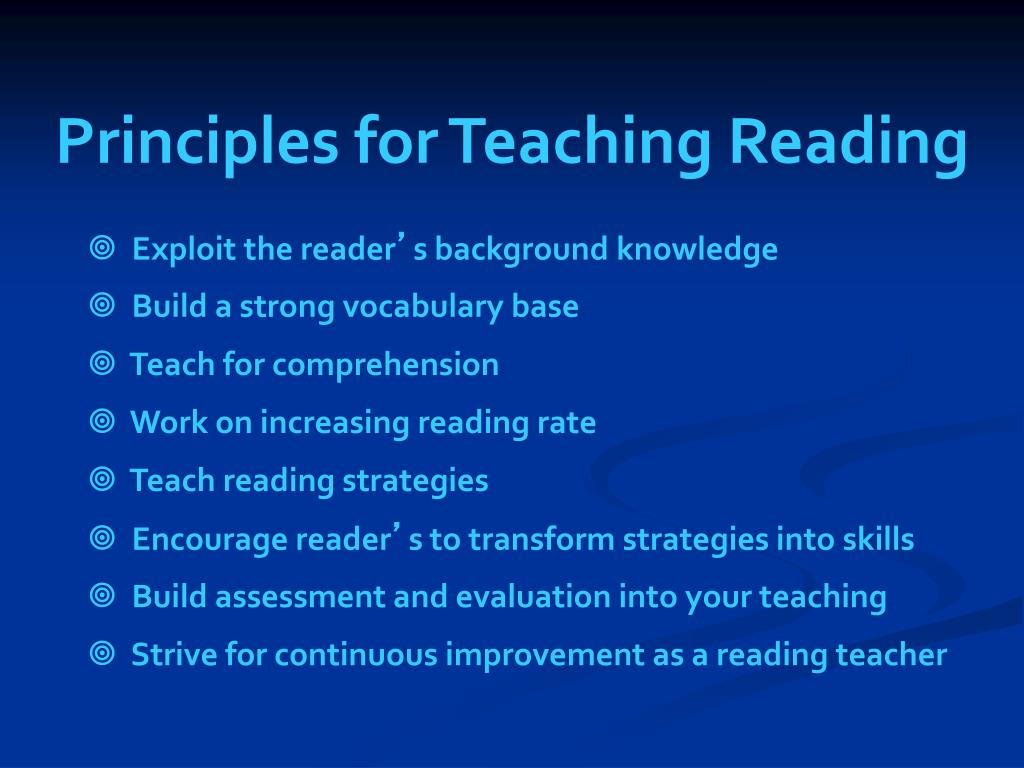

The few minutes you spend preparing BEFORE reading any difficult material can motivate you to read it, as well as increase your ability to understand and remember what you read. Think about it like this: when you are driving to a new place, you would probably look at a map first (or at least turn on your GPS) so you don’t waste time getting lost. Similarly, when you approach a new academic reading, it’s best to use the 4P’s (

purpose, preview, prior knowledge, and predict) so you don’t struggle as much to figure out what the authors want to say or how they plan to say it. Preparing to read can also help you estimate how long you’ll take to read so you can plan your time more efficiently.

Reading Strategy: Previewing

What It Is

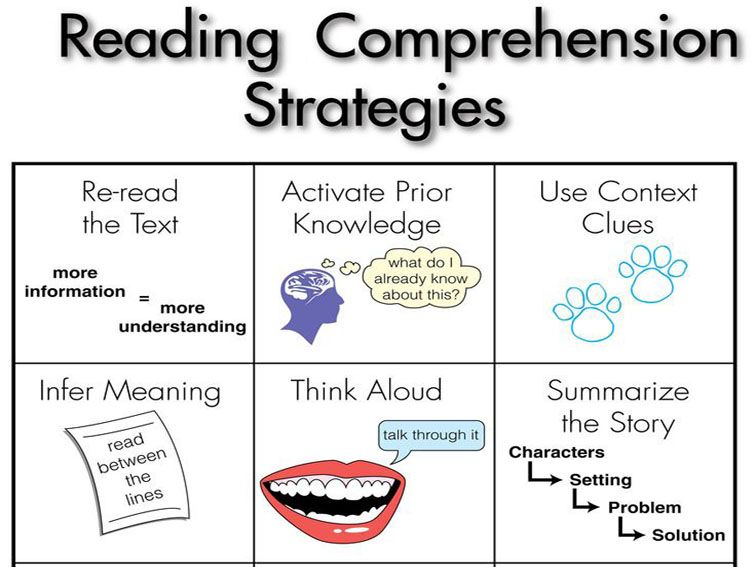

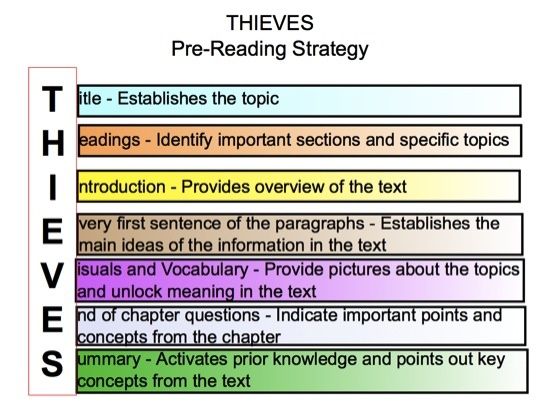

Previewing is a strategy that readers use to recall prior knowledge and set a purpose for reading. It calls for readers to skim a text before reading, looking for various features and information that will help as they return to read it in detail later.

Why Use It

According to research, previewing a text can improve comprehension (Graves, Cooke, & LaBerge, 1983, cited in Paris et al., 1991).

Previewing a text helps readers prepare for what they are about to read and set a purpose for reading.

The genre determines the reader’s methods for previewing:

- Readers preview nonfiction to find out what they know about the subject and what they want to find out. It also helps them understand how an author has organized information.

- Readers preview biographies to determine something about the person in the biography, the time period, and some possible places and events in the life of the person.

- Readers preview fiction to determine characters, setting, and plot. They also preview to make predictions about story’s problems and solutions.

When To Use It

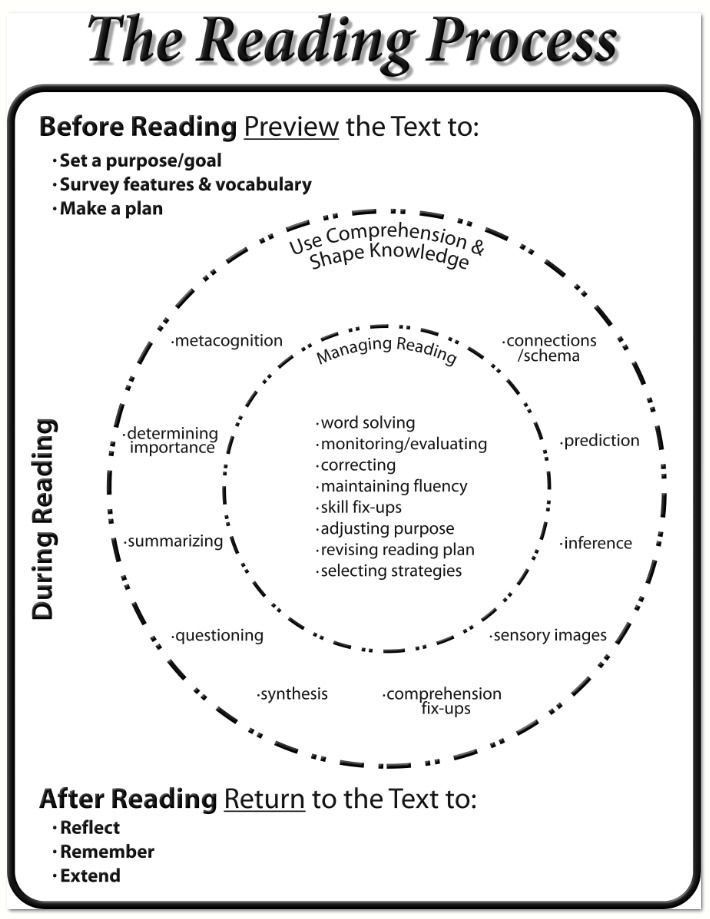

Previewing is a strategy readers use before and during reading.

How To Use It

When readers preview a text before they read, they first ask themselves whether the text is fiction or nonfiction.

- If the text is fiction or biography, readers look at the title, chapter headings, introductory notes, and illustrations for a better understanding of the content and possible settings or events.

- If the text is nonfiction, readers look at text features and illustrations (and their captions) to determine subject matter and to recall prior knowledge, to decide what they know about the subject. Previewing also helps readers figure out what they don’t know and what they want to find out.

How to Preview

Figure: CC BY-NCPreviewing a text is similar to watching a movie preview.

Think of previewing a text as similar to watching a movie trailer. A successful preview for either a movie or a reading experience will capture what the overall work is going to be about, generally what expectations the audience can have of the experience to come, how the piece is structured, and what kinds of patterns will emerge.

Previewing engages your prior experience and asks you to think about what you already know about this subject matter, or this author, or this publication. Then anticipate what new information might be ahead of you when you return to read this text more closely.

Specific Previewing Strategies

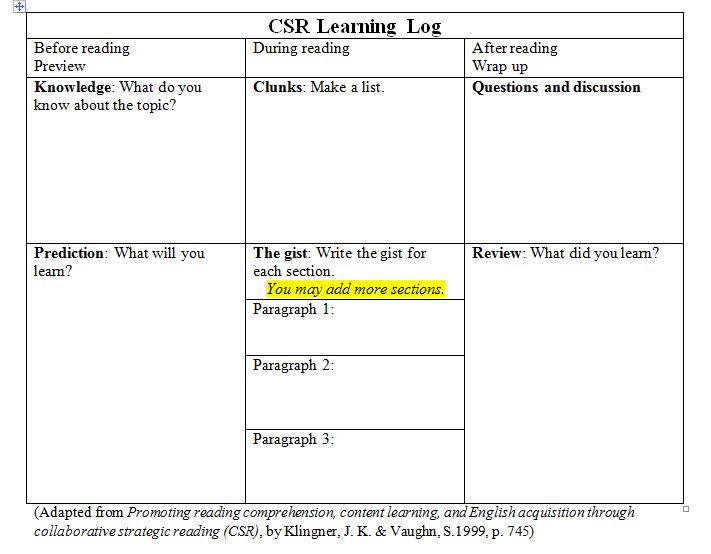

KWL+

KWL+ is a simple strategy that is both a reading-writing strategy, as well as an overall structure for research papers. K stands for "What I Know".

W stands for "What I Want to Know." L stands for "What I Learned. " + stands for "What I Still (+) Want to Know.

" + stands for "What I Still (+) Want to Know.

Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

After a brief review of the topic you will be reading about, on a piece of paper, create a table like the one below with the topic at the top of the page. Write down what you already know about the topic in the K column and what you want to learn in the W column. Use the "K" column as an "into the reading" activity and the "W" column as a guide for what you will look for as you read about the topic. After you have done your research or reading, write down what you learned in the "L" column. Then -- at the end of the research process or when you are done reading -- write down what you still want to know in the "+" column. This becomes a recursive process (routine) in which the "+" can then become the base for the next round of your inquiry.

Topic: _________________________________________________________________

| K (What I Know) | W (What I Want to Know) | L (What I Learned) | + (What I Still Want to Know) |

- Topic: _________________________________________________________________

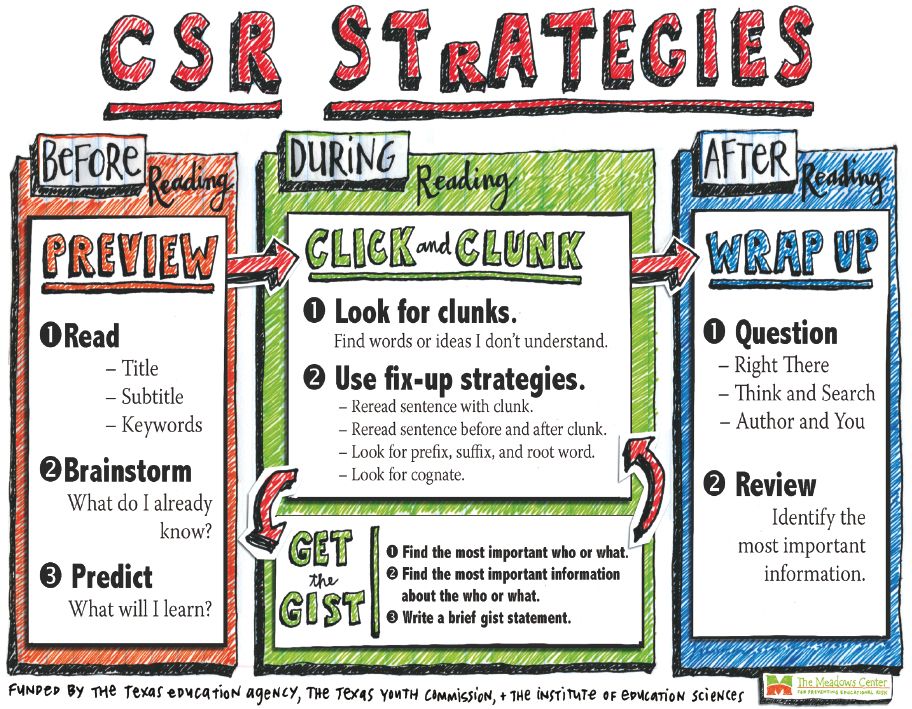

The 4 "P"s: Purpose, Preview, Prior Knowledge, Predict

1. Purpose: Determining your reading goals can help motivate you to read. It will also determine how carefully you need to read and what reading strategies you can use.

Purpose: Determining your reading goals can help motivate you to read. It will also determine how carefully you need to read and what reading strategies you can use.

- Are you looking for general main ideas or specific details, or both?

- Are you going to discuss what you read in class, take a test, use what you read in an essay? Or are you just reading for pleasure?

- How does this reading task tie into the unit or the whole course?

2. Preview: Spend a few minutes looking at visual clues to the author’s central idea, supporting points, and organization of ideas. Depending on the type of reading, look at some, or all, of the following elements:

- Title

- Introductory information about the author and/or selection

- First and last paragraphs

- First sentence of body paragraphs

- Headings and subheadings

- Italics, bold print, numbers, symbols

- Comprehension questions or, other after-reading assignment

3. Prior Knowledge: What do you already know about this topic? Using your own background knowledge and experiences can help stimulate your interest and increase your comprehension.

Prior Knowledge: What do you already know about this topic? Using your own background knowledge and experiences can help stimulate your interest and increase your comprehension.

4. Predict: After previewing a text, a reader can begin to make guesses about what the writer wants to say. These predictions are important in motivating you and keep you focused while reading.

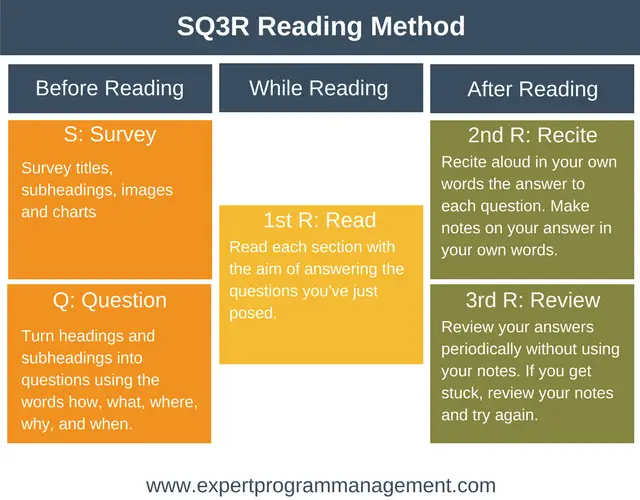

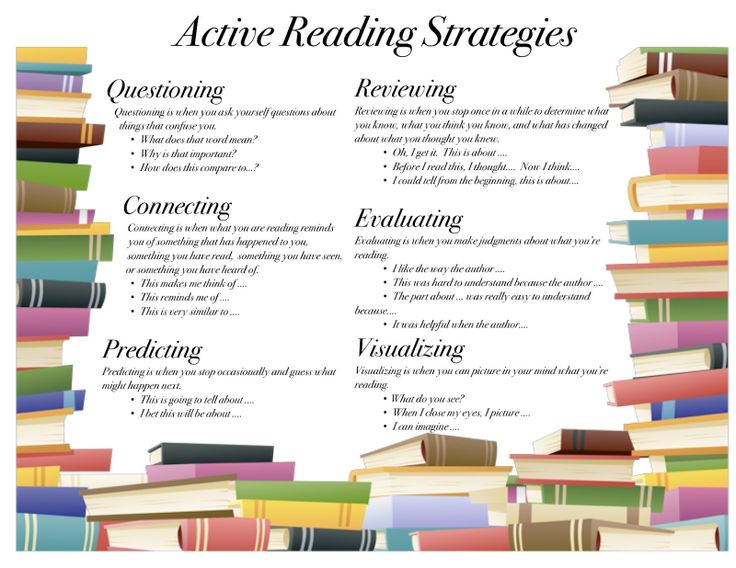

Use the SQ3R Strategy

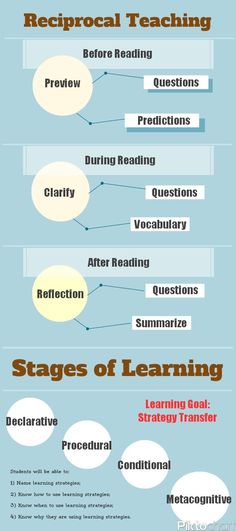

One strategy you can use to become a more active, engaged reader is the SQ3R strategy, a step-by-step process to follow before, during, and after reading. You may already be using some variation of it. In essence, the process works like this:

1. Survey the text in advance.

2. Form questions before you start reading.

3. Read the text.

4. Recite and/or record important points during and after reading.

5. Review and reflect on the text after you read.

Before reading, survey -- or preview -- the text. As noted earlier, reading introductory paragraphs and headings can help you figure out the text's main point and identify what important topics will be covered. However, surveying does not stop there. Look over sidebars, photographs, and any other text or graphic features that catch your eye. Skim a few paragraphs. Preview any boldfaced or italicized vocabulary terms. This will help you form a first impression of the material.

Next, start brainstorming questions about the text. What do you expect to learn from the reading? You may find that some questions come to mind immediately based on your initial survey or based on previous readings and class discussions. If not, try using headings and subheadings in the text to formulate questions. For instance, if one heading i your textbook reads "Medicare and Medicaid," you might ask yourself:

- When was Medicare and Medicaid legislation enacted? Why?

- What are the major differences between these two programs?

Although some of your questions may be simple factual questions, try to come up with a few that are ore open-ended. Asking in-depth questions will help you stay more engaged as you read.

Asking in-depth questions will help you stay more engaged as you read.

The next step is simple: read. As you read, notice whether your first impressions of the text were correct. Are the author's main points and overall approach about the same as what you predicted--or does the text contain a few surprises? Also, look for answers to your earlier questions and begin forming new questions. Continue to revise your impressions and questions as you read.

While you are reading, pause occasionally to record/recite important points. It is best to do this at the end of each section or where there is an obvious shift in the writer's train of thought. Put the book aside for a moment and recite aloud the main points of the section or any important answers you found there. You might also record ideas by jotting down a few brief notes in addition to, or instead of, reciting aloud. Either way, the physical act of articulating information makes you more likely to remember it.

After you have completed the reading, take some time to review the material more thoroughly. If the textbook includes review questions or your instructor has provided a study guide, use these tools to guide your review. You will want to record information in a more detailed format than you did during reading (which would be an outline or a list).

If the textbook includes review questions or your instructor has provided a study guide, use these tools to guide your review. You will want to record information in a more detailed format than you did during reading (which would be an outline or a list).

As you review the material, reflect on what you learned. Did anything surprise you, upset you, or make you think? Did you find yourself strongly agree or disagreeing with any points in the text? What topics would you like to explore further? Jot down your reflections in your notes. (Instructors sometimes require students to write brief response papers or maintain a reading journal. Use these assignments to help you reflect on what you read.)

The video below explains a little more about the SQ3R strategy.

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\)Exercise \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Choose another text that you have been assigned to read for a class. Use the SQ3R process to complete the reading. (Keep in mind that you may need to spread the reading over more than one sesion, especially if the text is long.)

Use the SQ3R process to complete the reading. (Keep in mind that you may need to spread the reading over more than one sesion, especially if the text is long.)

Be sure to complete all the steps involved. Then, reflect o n how helpful you found this process. On a scale of one to ten, how useful did you find it? How does it compare with other study techniques you have used?

Use Other Active Reading Strategies

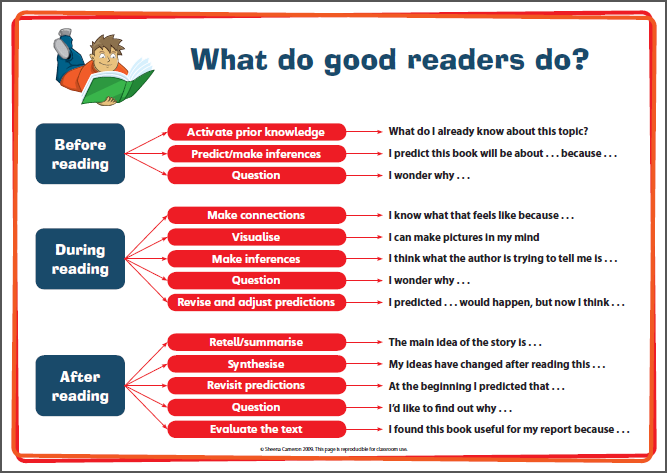

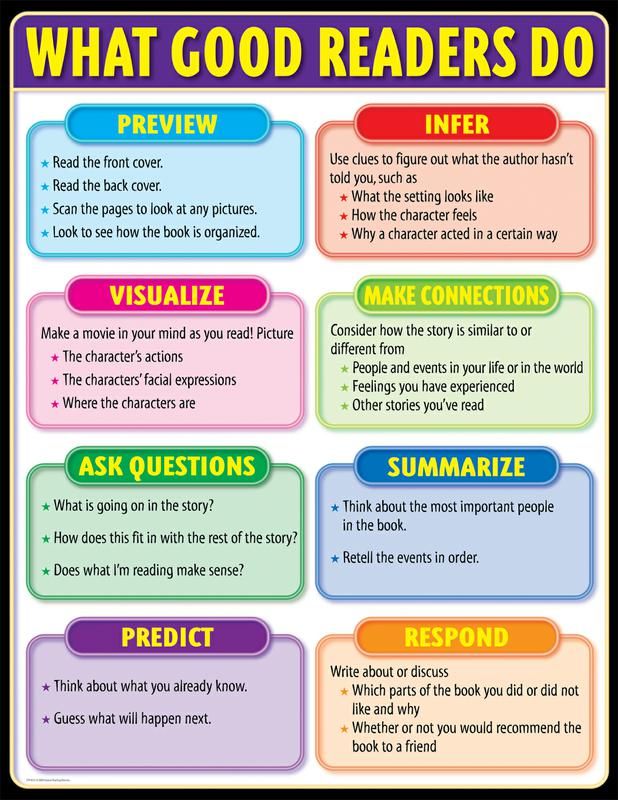

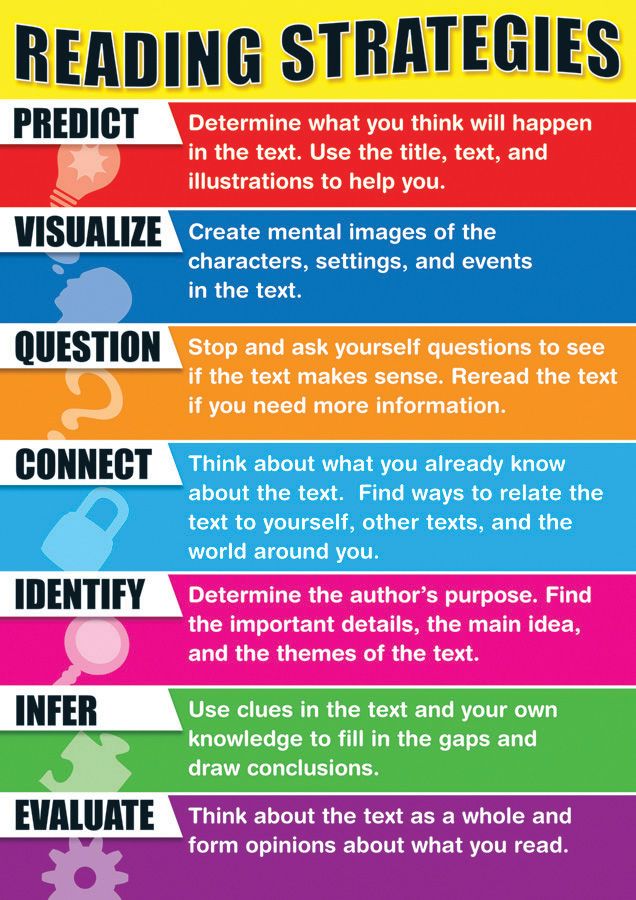

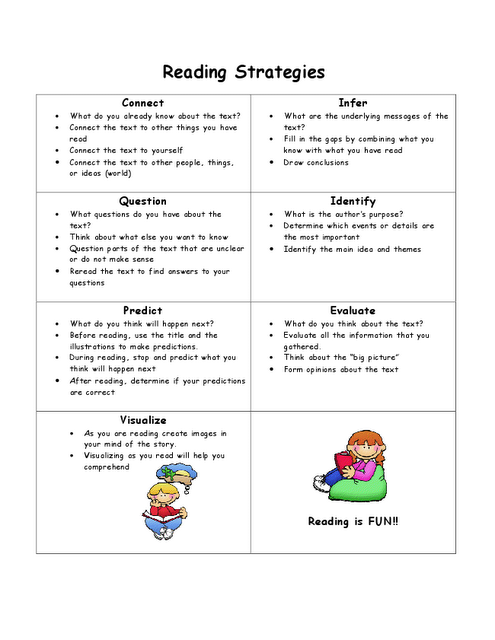

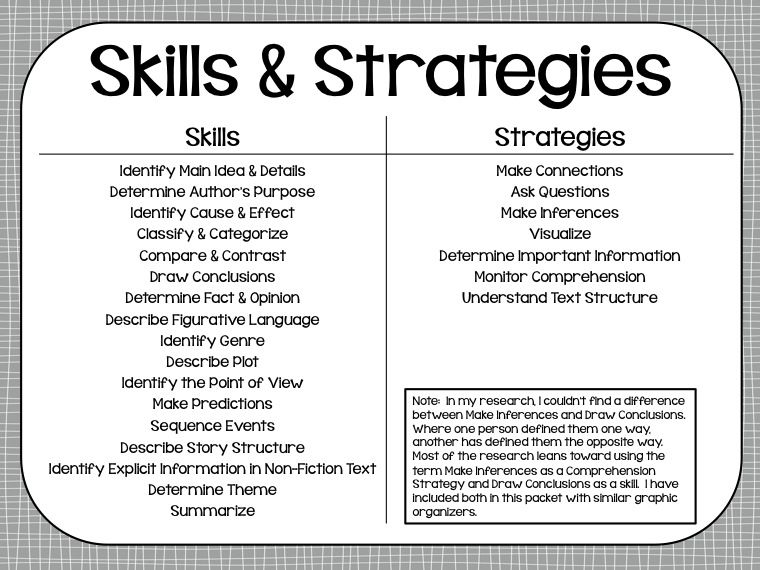

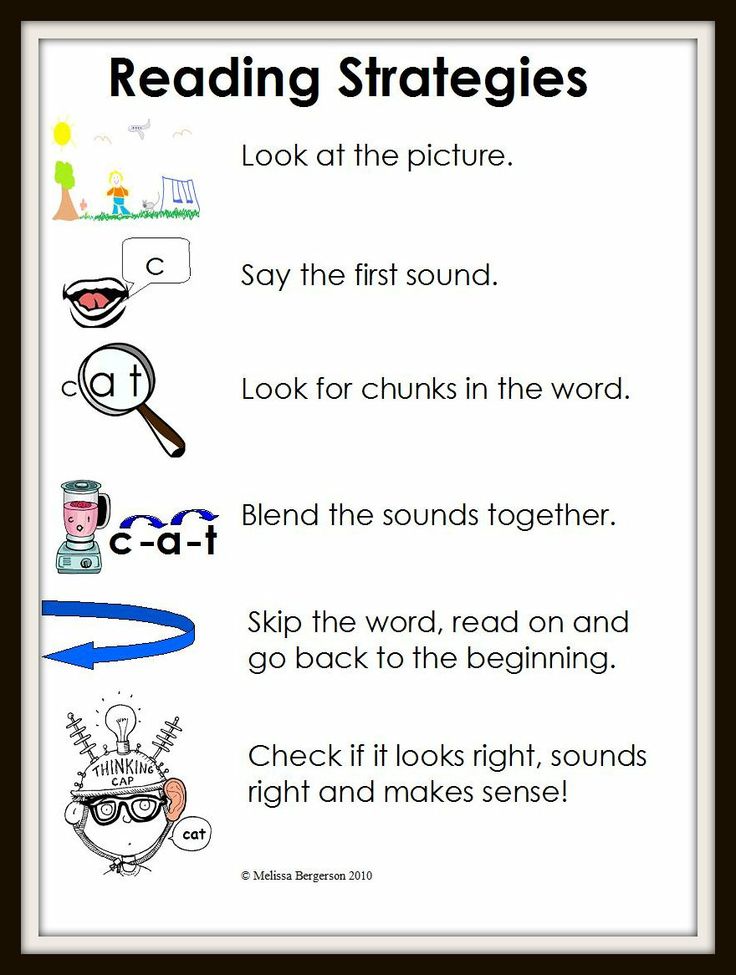

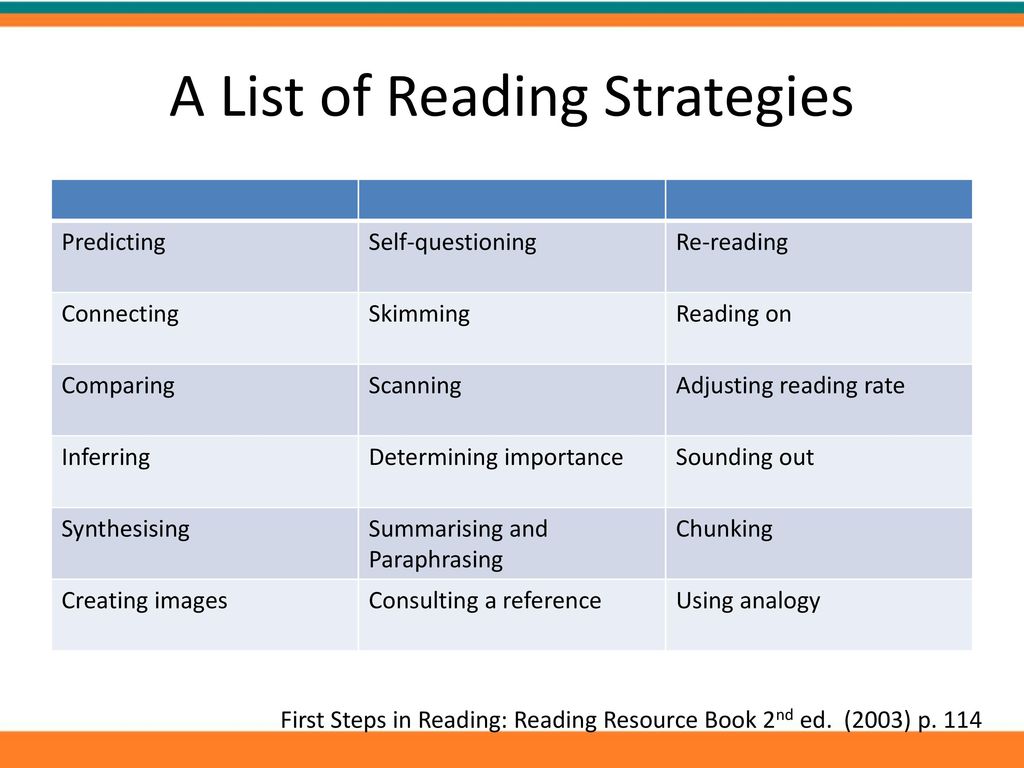

The SQ3R process encompasses a number of valuable active reading strategies: previewing a text, making predictions, asking and answering quesitons, and summarizing. You can use the following additional strategies to further deepen your understanding of what you read.

- Connect what you read to what you already know. Look for ways the reading supports, extends, or challenges concepts you have learned elsewhere.

- Relate the reading to your own life. What statements, people, or situations relate to your personal experiences?

- Visualize.

For both fiction and nonfiction texts, try to picture what is described. Visualizing is especially helpful when you are readinga narrative text, such as a novel or a historical account, or when you read expository texts that describes a process, such as how to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

For both fiction and nonfiction texts, try to picture what is described. Visualizing is especially helpful when you are readinga narrative text, such as a novel or a historical account, or when you read expository texts that describes a process, such as how to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). - Pay attention to graphics a well as text. Photographs, diagrams, flow charts, tables, and other graphics can help make abstract ideas more concrete and understandable.

- Understand the text in context. Understanding context means thinking about who wrote the text, when and where it was written, the author's purpose in writing it, and what assumptions or agendas influenced the author's ideas. For instance, two writers address the subject of health care reform, but if one article is an opinion piece and one is a news story, the rhetorical context is different.

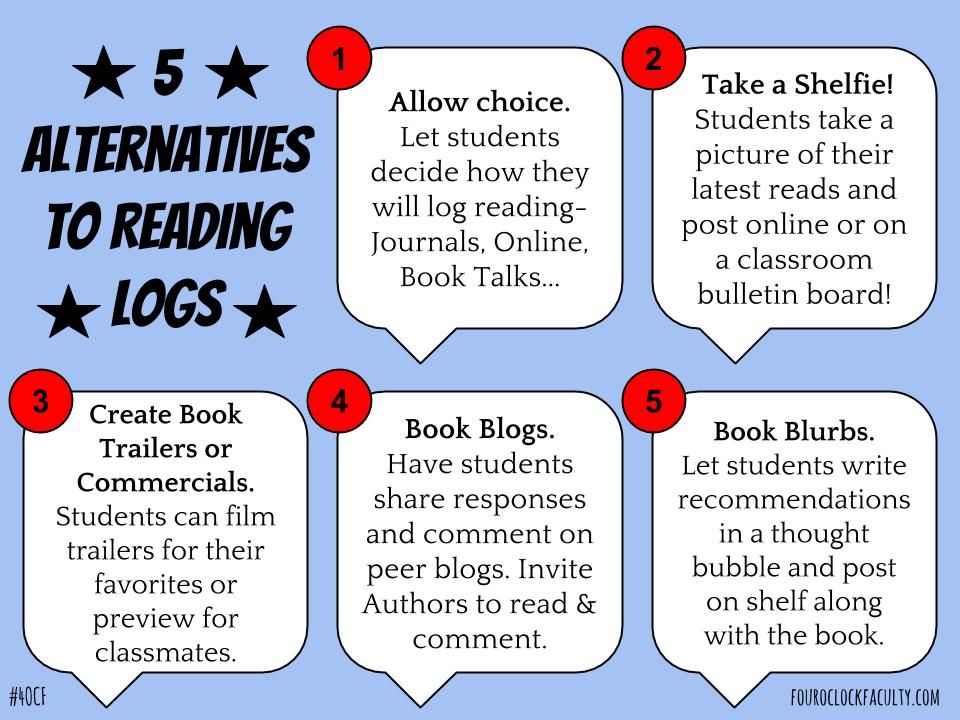

- Plan to talk or write about what you read.

Jot down a few questions or comments in your notebook so you can bring them up in class. (This also gives you a source of topic ideas for papers and presentations later in the semester.) Discuss the reading on a class discussion board or blog about it.

Jot down a few questions or comments in your notebook so you can bring them up in class. (This also gives you a source of topic ideas for papers and presentations later in the semester.) Discuss the reading on a class discussion board or blog about it.

Additional Strategies

Following are some strategies you can use to enhance your reading even further:

- Pace yourself. Figure out how much time you have to complete the assignment. Divide the assignment into smaller blocks rather than trying to read the entire assignment in one sitting. If you have a week to do the assignment, for example, divide the work into five daily blocks, not seven; that way you won’t be behind if something comes up to prevent you from doing your work on a given day. If everything works out on schedule, you’ll end up with an extra day for review.

- Schedule your reading. Set aside blocks of time, preferably at the time of the day when you are most alert, to do your reading assignments.

Don’t just leave them for the end of the day after completing written and other assignments.

Don’t just leave them for the end of the day after completing written and other assignments. - Get yourself in the right space. Choose to read in a quiet, well-lit space. Your chair should be comfortable but provide good support. Libraries were designed for reading—they should be your first option! Don’t use your bed for reading textbooks; since the time you were read bedtime stories, you have probably associated reading in bed with preparation for sleeping. The combination of the cozy bed, comforting memories, and dry text is sure to invite some shut-eye!

- Avoid distractions. Active reading takes place in your short-term memory. Every time you move from task to task, you have to “reboot” your short-term memory and you lose the continuity of active reading. Multitasking—listening to music or texting on your cell phone while you read—will cause you to lose your place and force you to start over again. Every time you lose focus, you cut your effectiveness and increase the amount of time you need to complete the assignment.

- Avoid reading fatigue. Work for about fifty minutes, and then give yourself a break for five to ten minutes. Put down the book, walk around, get a snack, stretch, or do some deep knee bends. Short physical activity will do wonders to help you feel refreshed.

- Read your most difficult assignments early in your reading time, when you are freshest.

- Make your reading interesting. Try connecting the material you are reading with your class lectures or with other chapters. Ask yourself where you disagree with the author. Approach finding answers to your questions like an investigative reporter. Carry on a mental conversation with the author.

- Highlight your reading material. Most readers tend to highlight too much, hiding key ideas in a sea of yellow lines, making it difficult to pick out the main points when it is time to review. When it comes to highlighting, less is more. Think critically before you highlight.

Your choices will have a big impact on what you study and learn for the course. Make it your objective to highlight no more than 15-25% of what you read. Use highlighting after you have read a section to note the most important points, key terms, and concepts. You can’t know what the most important thing is unless you’ve read the whole section, so don’t highlight as you read.

Your choices will have a big impact on what you study and learn for the course. Make it your objective to highlight no more than 15-25% of what you read. Use highlighting after you have read a section to note the most important points, key terms, and concepts. You can’t know what the most important thing is unless you’ve read the whole section, so don’t highlight as you read. - Annotate your reading material. Marking up your book may go against what you were told in high school when the school owned the books and expected to use them year after year. In college, you bought the book. Make it truly yours. Although some students may tell you that you can get more cash by selling a used book that is not marked up, this should not be a concern at this time—that’s not nearly as important as understanding the reading and doing well in the class!

The purpose of marking your textbook is to make it your personal studying assistant with the key ideas called out in the text.

Use your pencil also to make annotations in the margin. Use a symbol like an exclamation mark (!) or an asterisk (*) to mark an idea that is particularly important. Use a question mark (?) to indicate something you don’t understand or are unclear about. Box new words, then write a short definition in the margin. Use “TQ” (for “test question”) or some other shorthand or symbol to signal key things that may appear in test or quiz questions. Write personal notes on items where you disagree with the author. Don’t feel you have to use the symbols listed here; create your own if you want, but be consistent. Your notes won’t help you if the first question you later have is “I wonder what I meant by that?”

Use your pencil also to make annotations in the margin. Use a symbol like an exclamation mark (!) or an asterisk (*) to mark an idea that is particularly important. Use a question mark (?) to indicate something you don’t understand or are unclear about. Box new words, then write a short definition in the margin. Use “TQ” (for “test question”) or some other shorthand or symbol to signal key things that may appear in test or quiz questions. Write personal notes on items where you disagree with the author. Don’t feel you have to use the symbols listed here; create your own if you want, but be consistent. Your notes won’t help you if the first question you later have is “I wonder what I meant by that?”Watch the following video on annotating texts:

Video \(\PageIndex{1}\)

Video: Annotate It! Authored by: Janene Davison. All Rights Reserved. Standard YouTube license.

All Rights Reserved. Standard YouTube license.

- Get to Know the Conventions. Academic texts, like scientific studies and journal articles, may have sections that are new to you. If you’re not sure what an “abstract” is, research it online or ask your instructor. Understanding the meaning and purpose of such conventions is not only helpful for reading comprehension but for writing, too.

- Look up and Keep Track of Unfamiliar Terms and Phrases. Have a good college dictionary such as Merriam-Webster handy (or find it online) when you read complex academic texts, so you can look up the meaning of unfamiliar words and terms. Many textbooks also contain glossaries or “key terms” sections at the ends of chapters or the end of the book. Many books available on an e-reader have definitions already embedded if you highlight the unknown word. If you can’t find the words you’re looking for in a standard dictionary, you may need one specially written for a particular discipline.

For example, a medical dictionary would be a good resource for a course in anatomy and physiology. If you circle or underline terms and phrases that appear repeatedly, you’ll have a visual reminder to review and learn them. Repetition helps to lock in these new words and to get their meaning into long-term memory, so the more you review them, the more you’ll understand and feel comfortable using them.

For example, a medical dictionary would be a good resource for a course in anatomy and physiology. If you circle or underline terms and phrases that appear repeatedly, you’ll have a visual reminder to review and learn them. Repetition helps to lock in these new words and to get their meaning into long-term memory, so the more you review them, the more you’ll understand and feel comfortable using them. - Make Flashcards. If you are studying certain words for a test, or you know that certain phrases will be used frequently in a course or field, try making flashcards for review. For each key term, write the word on one side of an index card and the definition on the other. Drill yourself, and then ask your friends to help quiz you. Developing a strong vocabulary is similar to most hobbies and activities. Even experts in a field continue to encounter and adopt new words.

Contributors

- Adapted from Previewing in College Composition. Provided by: Lumen Learning.

CC BY-SA

CC BY-SA - Adapted from Successful College Composition. Authored by: Kathryn Crowther, Lauren Curtright, Nancy Gilbert, Barbara Hall, Tracienne Ravita, and Kirk Swenson. Provided by: Galileo, Georgia's Virtual Library. CC-NC-SA-4.0

- Adapted from EDUC 1300: Effective Learning Strategies. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Public Domain: No Known Copyright

This page most recently updated on June 6, 2020.

This page titled 3.3: Reading Strategies - Previewing is shared under a CC BY-SA license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Athena Kashyap & Erika Dyquisto (ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative) .

- Back to top

- Was this article helpful?

-

- Article type

- Section or Page

- Author

- Athena Kashyap & Erika Dyquisto

- License

- CC BY-SA

- OER program or Publisher

- ASCCC OERI Program

- Show TOC

- yes

- Tags

-

- #4Ps

- #annotation

- #KWL+

- #predict

- #preview

- #previewing

- #prior knowledge

- #purpose

- #reading

- #reading strategies

Reading strategies | UNSW Current Students

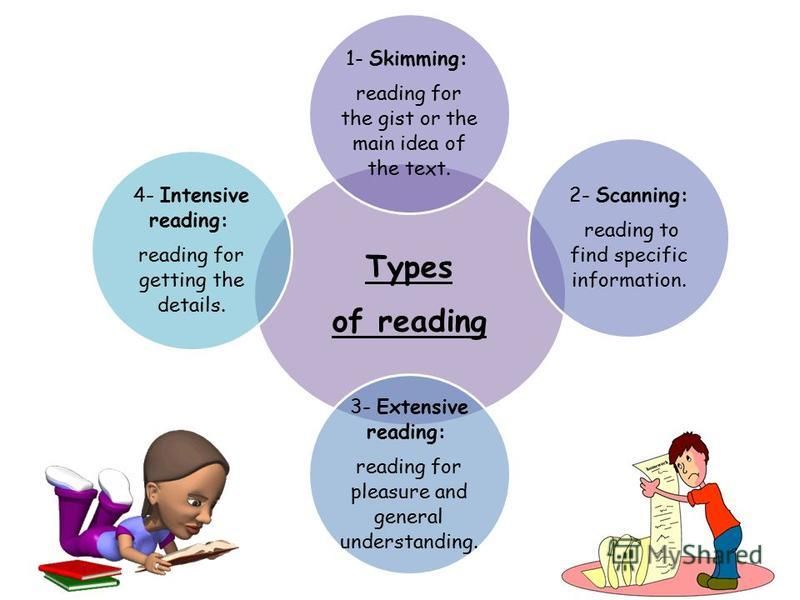

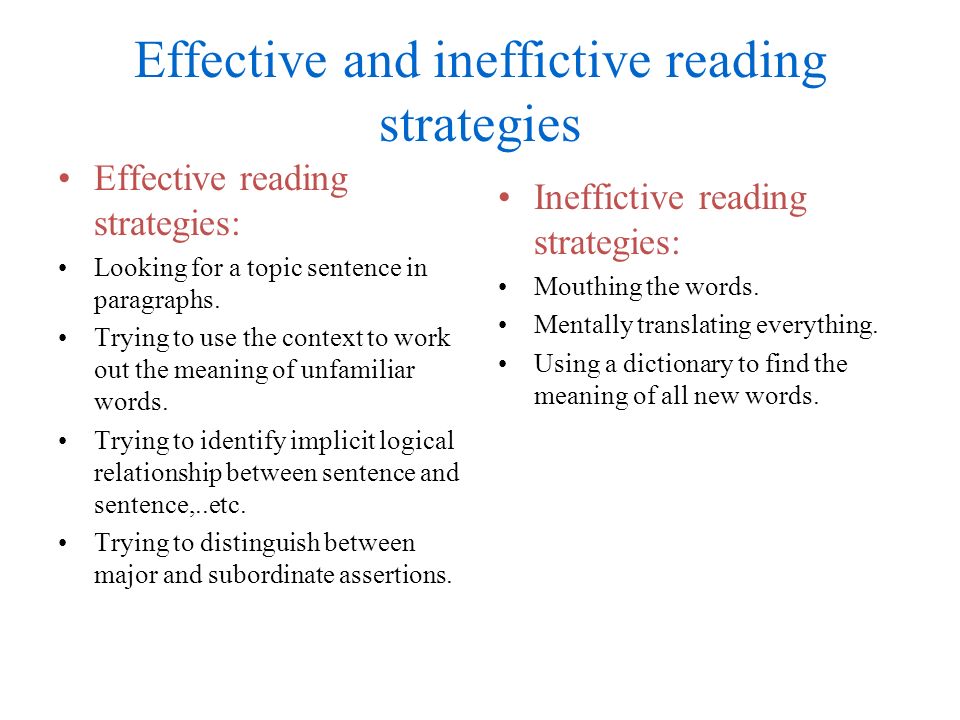

Active readers use reading strategies to help save time and cover a lot of ground. Your purpose for reading should determine which strategy or strategies to use.

Your purpose for reading should determine which strategy or strategies to use.

1. Previewing the text to get an overview

What is it? Previewing a text means that you get an idea of what it is about without reading the main body of the text.

When to use it: to help you decide whether a book or journal is useful for your purpose; to get a general sense of the article structure, to help you locate relevant information; to help you to identify the sections of the text you may need to read and the sections you can omit.

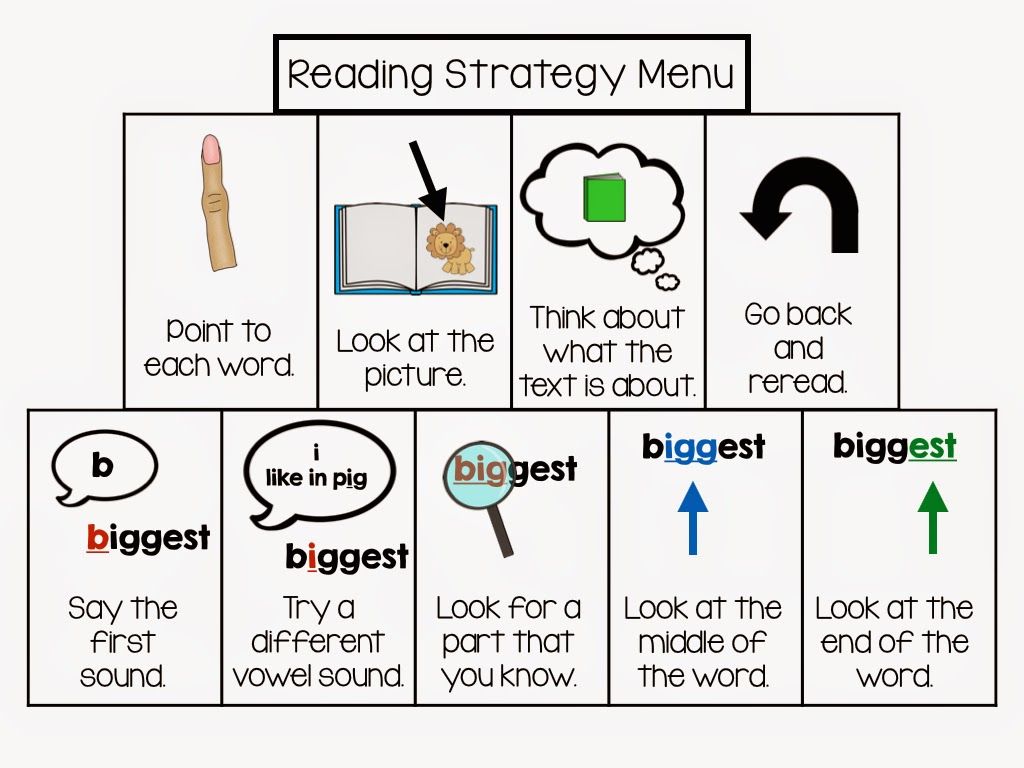

To preview, start by reading:

- the title and author details

- the abstract (if there is one)

- then read only the parts that ‘jump out’; that is: main headings and subheadings, chapter summaries, any highlighted text etc.

- examine any illustrations, graphs, tables or diagrams and their captions, as these usually summarise the content of large slabs of text

- the first sentence in each paragraph

2.

Skimming

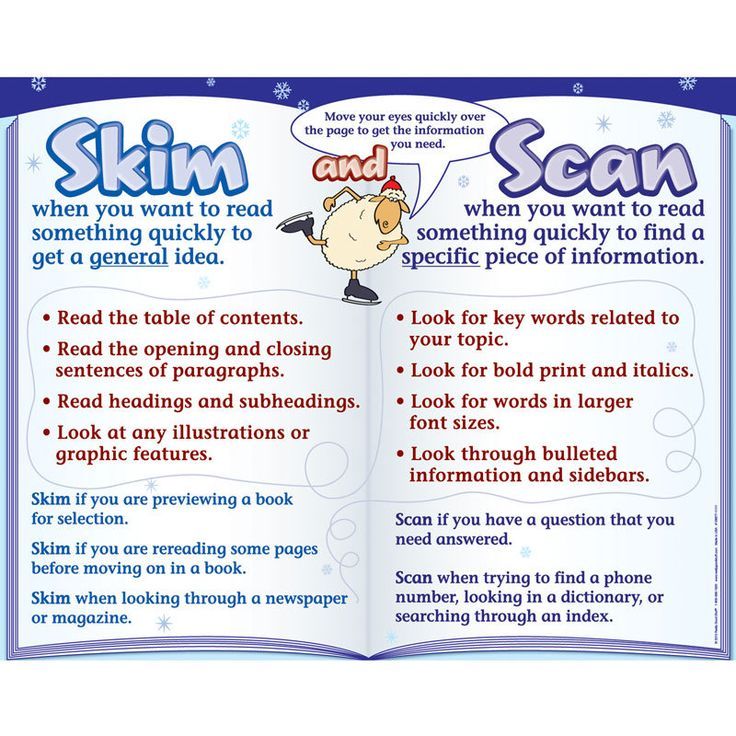

Skimming What is it? Skimming involves running your eye very quickly over large chunks of text. It is different from previewing because skimming involves the paragraph text. Skimming allows you to pick up some of the main ideas without paying attention to detail. It is a fast process. A single chapter should take only a few minutes.

When to use it: to quickly locate relevant sections from a large quantity of written material. Especially useful when there are few headings or graphic elements to gain an overview of a text. Skimming adds further information to an overview.

How to skim:

- note any bold print and graphics.

- start at the beginning of the reading and glide your eyes over the text very quickly.

- do not actually read the text in total. You may read a few words of every paragraph, perhaps the first and last sentences.

- always familiarise yourself with the reading material by gaining an overview and/or skimming before reading in detail.

3. Scanning

What is it? Scanning is sweeping your eyes (like radar) over part of a text to find specific pieces of information.

When to use it: to quickly locate specific information from a large quantity of written material.

To scan text:

- after gaining an overview and skimming, identify the section(s) of the text that you probably need to read.

- start scanning the text by allowing your eyes (or finger) to move quickly over a page.

- as soon as your eye catches an important word or phrase, stop reading.

- when you locate information requiring attention, you then slow down to read the relevant section more thoroughly.

- scanning and skimming are no substitutes for thorough reading and should only be used to locate material quickly.

4. Intensive reading

What is it? Intensive reading is detailed, focused, ‘study’ reading of those important parts, pages or chapters.

When to use it: When you have previewed an article and used the techniques of skimming and scanning to find what you need to concentrate on, then you can slow down and do some intensive reading.

How to read intensively:

- start at the beginning. Underline any unfamiliar words or phrases, but do not stop the flow of your reading.

- if the text is relatively easy, underline, highlight or make brief notes (see ‘the section on making notes from readings).

- if the text is difficult, read it through at least once (depending on the level of difficulty) before making notes.

- be alert to the main ideas. Each paragraph should have a main idea, often contained in the topic sentence (usually the first sentence) or the last sentence.

- when you have finished go back to the unfamiliar vocabulary. Look it up in an ordinary or subject-specific dictionary. If the meaning of a word or passage still evades you, leave it and read on. Perhaps after more reading you will find it more accessible and the meaning will become clear.

Speak to your tutor if your difficulty continues.

Speak to your tutor if your difficulty continues. - write down the bibliographic information and be sure to record page numbers (more about this in the section on making notes from readings).

Remember, when approaching reading at university you need to make intelligent decisions about what you choose to read, be flexible in the way you read, and think about what you are trying to achieve in undertaking each reading task.

See next: More reading strategies

Semantic reading strategy. SCH receptions.

Strategy of semantic reading

Strategy is a certain way of acquiring, storing and using information that serves to achieve certain goals in the sense that it should lead to certain results.

Innovative method

Traditional method

Types of strategies

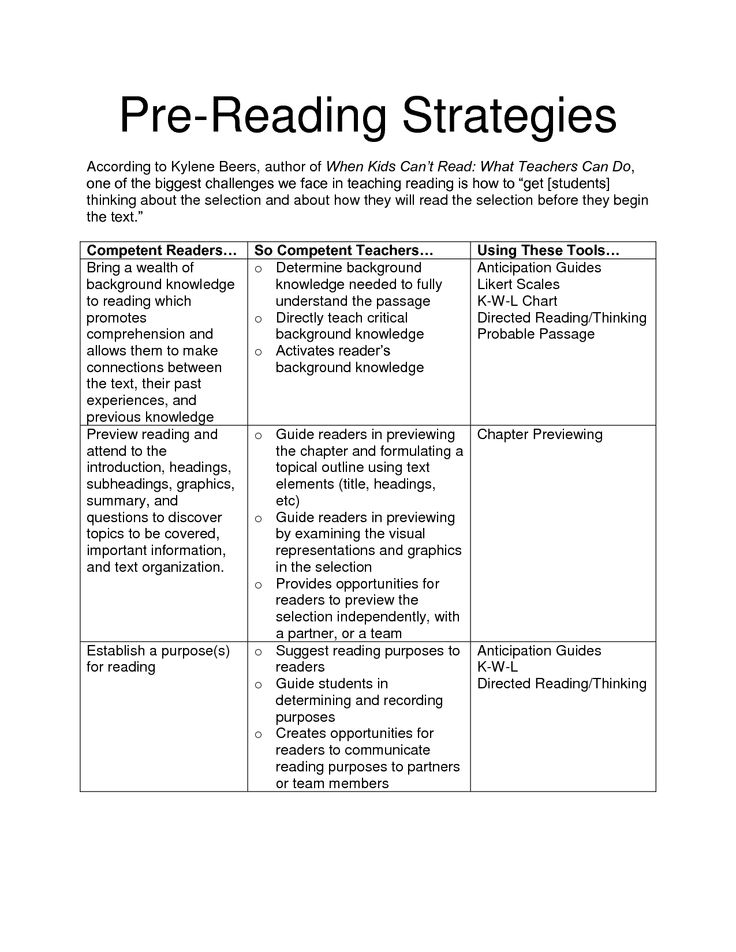

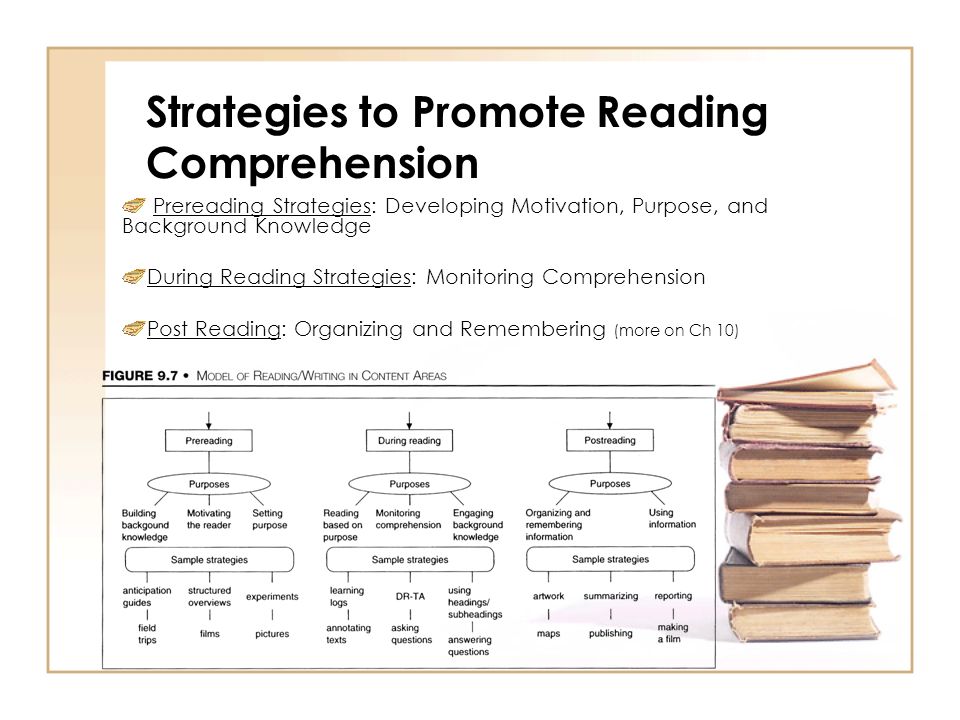

Strategies of pre-text activity

Goal:

- Setting the task of reading

- Choosing the type of reading

- Updating previous knowledge and experience, concepts and vocabulary of the text 9 Creating motivation for reading

- Brainstorming

- Glossary

- Text content anticipation guidelines

- Question Battery

- Preliminary Questions

- Question Dissection

- Look at the list of words and mark those that can be associated with the text

- When you finish reading the text, return to these words (this will be a post-text strategy ) and look at the meaning and usage of the words used in the text.

- Read the statements and mark those with which you agree

- Mark them again after reading the text.

If your answer has changed, explain why it happened (post-text strategy)

If your answer has changed, explain why it happened (post-text strategy) - Read the title of the text and divide it into semantic groups.

- What do you think the text will be about?

- “Reading in a circle” (alternating reading)

- “Reading to yourself with questions”

- “Reading to yourself with stops”

- “Reading to yourself with notes”

- Read the text in paragraphs in turn. The teacher always reads first.

Text one and passed on to the next reader. The rest are closed and put aside.

Text one and passed on to the next reader. The rest are closed and put aside. - Listeners ask questions about the content of the text, the reader answers. If the answer is incorrect or inaccurate, the listeners correct it.

- Read the first paragraph silently and ask questions. The partner answers.

- Read the second paragraph silently. Change roles.

- "Relationship between question and answer"

- "Questions after the text"

- "Time out"

- "Checklist"

- Read the question and say which group it belongs to. After that, give an answer to it.

- Factual information

- Subtext information hidden between lines

- Conceptual information, often found outside the text

- Evaluative, related to critical analysis of the text

Time-out

Purpose: self-test and assessment of understanding of the text by discussing it in pairs and group

- Read the 1st paragraph to yourself silently.

Then work in pairs.

Then work in pairs. - Ask each other clarifying questions. If you are not sure about the correct answer, bring your questions to the discussion of the whole group after the completion of the text.

- Do the same for all paragraphs

- Summarize what you have learned from the text.

Checklist "Brief retelling"

- The main idea of the text is named (Yes / No)

- The main thoughts of the text and the main details are named (Yes / No)

- There is a logical and semantic structure of the text (Yes / No)

- Available the necessary means of communication that unite the main ideas of the text (Yes/No)

- The content is stated in one's own words while maintaining the lexical units of the author's text (Yes/No)

- Strategies for working with volumetric texts

- Strategies for text Compression Strategies

- General educational strategies

- Dictionary Development Strategies

- Strategies for working with information text

- Working strategies with a convincing type of

NIT FOR YOUOM its implementation

According to scientists, it is semantic reading that can become the basis for the development of a student's value-semantic personal qualities, reliable support for successful cognitive activity throughout his life.

Since in the new sociocultural and economic conditions reading is understood as a basic intellectual technology, as the most important resource for the development of the individual, as a source of acquiring knowledge , overcoming the limitations of individual social experience.

Since in the new sociocultural and economic conditions reading is understood as a basic intellectual technology, as the most important resource for the development of the individual, as a source of acquiring knowledge , overcoming the limitations of individual social experience. Noting the complexity of the reading process, most researchers distinguish two sides of it: technical and semantic .

Technical side involves optical perception, reproduction of the sound shell of a word, speech movements, that is, decoding texts and translating them into oral-speech form (T. G. Egorov, A. N. Kornev, A. R. Luria, M. I. Omorokova, L. S. Tsvetkova, D. B. Elkonin).

The semantic side of includes understanding of the meaning and meaning of individual words and the whole statement (T.

G Egorov, A. N. Kornev, A. R. Luria, L. S. Tsvetkova, D. B. Elkonin) or translation of the author's code to its semantic code (M. I. Omorokova).

G Egorov, A. N. Kornev, A. R. Luria, L. S. Tsvetkova, D. B. Elkonin) or translation of the author's code to its semantic code (M. I. Omorokova). For a novice reader, understanding arises as a result of the analysis and synthesis of syllables into words, and for an experienced reader - the semantic side is ahead of the technical , as evidenced by the appearance of semantic guesses in the reading process (A. R. Luria, M. N. Rusetskaya ).

The concept of semantic reading

Semantic reading – a type of reading that is aimed at understanding the semantic content of the text by the reader . In the concept of universal educational activities (Asmolov A.G., Burmenskaya G.V., Volodarskaya I.A., etc.), semantic reading actions related to:

- comprehension of the purpose and choice of the type of reading depending on the communicative task;

- definition of primary and secondary information;

- formulating the problem and the main idea of the text.

Semantic reading differs from any other reading in that in the semantic form of reading, processes of comprehension by the reader of the value-semantic moment of the text take place, i.e. the process of its interpretation, endowment with meaning. Each reader will "take" from the text exactly as much as he is able to "take" at the moment, depending on his needs and abilities. Hence the difference in perception. Semantic reading allows you to master both scientific and literary texts.

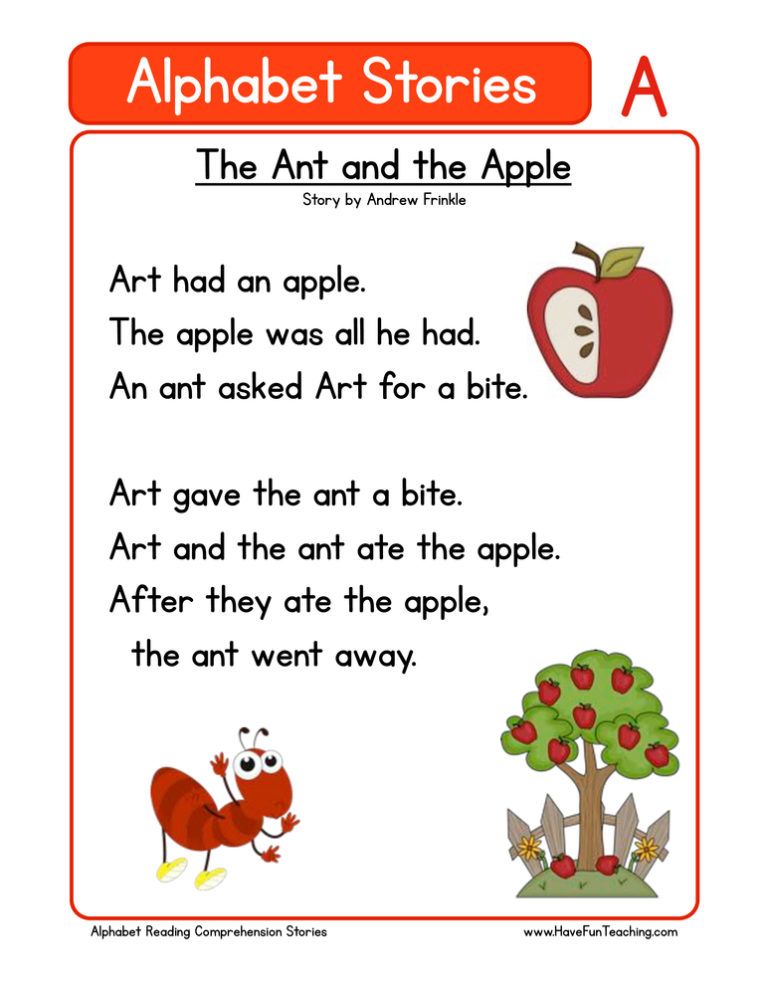

The purpose of semantic reading - to understand the content of the text as accurately and completely as possible, to catch all the details and practically comprehend the extracted information. This is a careful reading and understanding of the meaning with the help of text analysis. When a person reads really thoughtfully, then his imagination is sure to work, he can actively interact with his internal images. A person himself establishes the relationship between himself, the text and the surrounding world.

Meaningful reading is connected with understanding When a child masters semantic reading, then he develops oral speech and, as the next important stage of development, written speech.

When a child masters semantic reading, then he develops oral speech and, as the next important stage of development, written speech. What is “meaning”?

Meaning - s-thought, i.e. with thought. To put it simply, it means what thought is embedded inside a word, text, gesture, picture, building, etc. Thought, in turn, is always tied to action.

Any thought means certain actions leading to the final goal, state, image. This is not a flow of information, but a hint of action and result.

The meaning of in relation to the text and, in particular, to the minimum unit of this text is the integral content of any statement, not reducible to the meanings of its constituent parts and elements, but itself determining these meanings. Meaning actualizes in the system of meanings of the word that side of it, which is determined by the given situation, given context.

It is necessary to understand the difference between the concepts " meaning " and " meaning ". L.S. Vygotsky (“Thinking and Speech”, 1934) noted that “if “ meaning ” a word is an objective reflection of a system of connections and relations , then " the meaning of " is the introduction of subjective aspects of meaning according to the given moment and situation ".

Stages in the perception of the text, decoding the information contained in the text.

Ways of semantic reading

Analytical, or structural. In this case, the reader goes from the whole to the particular. The purpose of such reading is to understand the author's attitude to the subject or phenomenon and to identify the factors that influenced this attitude.

Synthetic or interpretive. Here the reader moves from the particular to the whole. The purpose of this method is to identify what tasks the author has set in this text and how and to what extent he solved them.

Critical or evaluation. The purpose of this method is to evaluate the author's text and decide whether the reader agrees with it.

The main stages of semantic reading

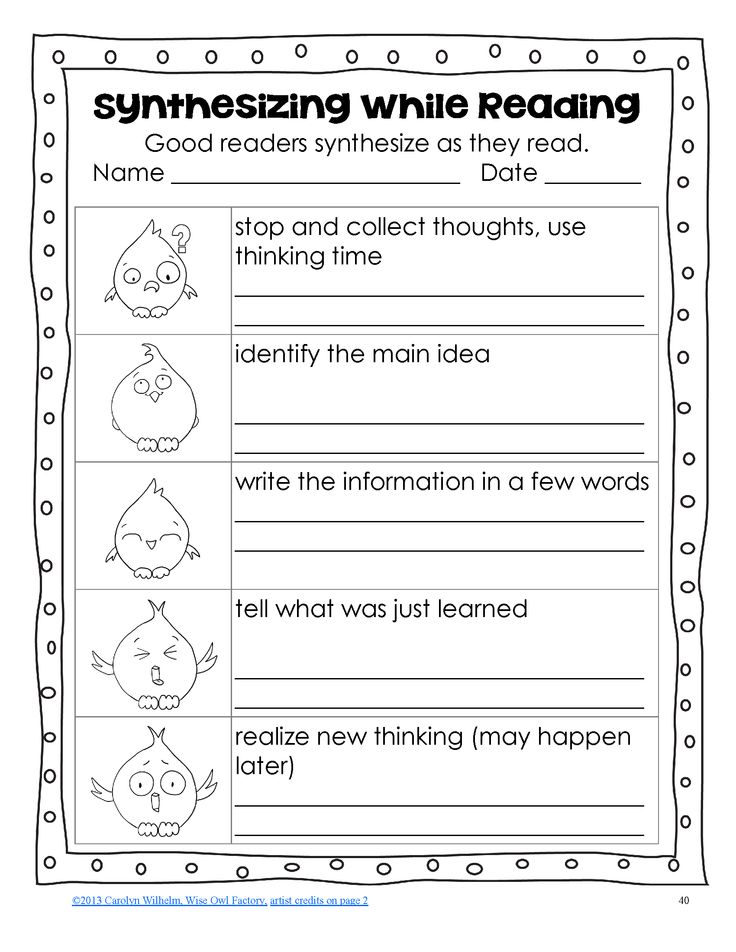

The process of reading consists of three phases.First phase (preread) is the perception of the text, the disclosure of its content and meaning, a kind of decoding, when a common content is formed from individual words, phrases, sentences. In this case, reading includes: viewing, establishing the meanings of words, finding correspondences, recognizing facts, analyzing the plot and plot, reproduction and retelling.

The second phase (reading) is the extraction of meaning, the explanation of the facts found using existing knowledge, the interpretation of the text. Here there is ordering and classification, explanation and summation, distinction, comparison and comparison, grouping, analysis and generalization, correlation with one's own experience, reflection on the context and conclusions.

Levels of text comprehension

The third phase (post-reading) is the creation of one's own new meaning, that is, the appropriation of acquired new knowledge as one's own as a result of reflection.

degree and depth perception of internal meaning depends on many reasons associated with the personality of the reader:

- Erudism,

- The level of education,

- Intuition,

- sensitivity to the word, ,

- intonation,

- skill of emotionally experienced.

- spiritual subtlety.

“The content of a text always has many degrees of freedom: different people understand the same text differently due to their individual characteristics and life experience” (L. Vygotsky).

“These two systems are a system of logical operations in cognitive activity and a system for evaluating the emotional meaning or deep meaning of a text,” writes A.R. Luria, are completely different psychological systems.

Mastering the skills of semantic reading

Meaningful reading cannot exist without cognitive activity. Indeed, in order for reading to be semantic, students need to:

- accurately and fully understand the content of the text,

- compose their own system of images,

- comprehend information, carry out cognitive activities.

There are many ways to organize cognitive activity that contribute to the development of semantic reading such as:

- problem-search method,

- discussion,

- discussion,

- modeling,

- drawing.

How to help a primary school student to master “the skills of meaningful reading of texts of various styles and genres”? One of the main ways to develop reading literacy is a strategic approach to teaching meaningful reading.

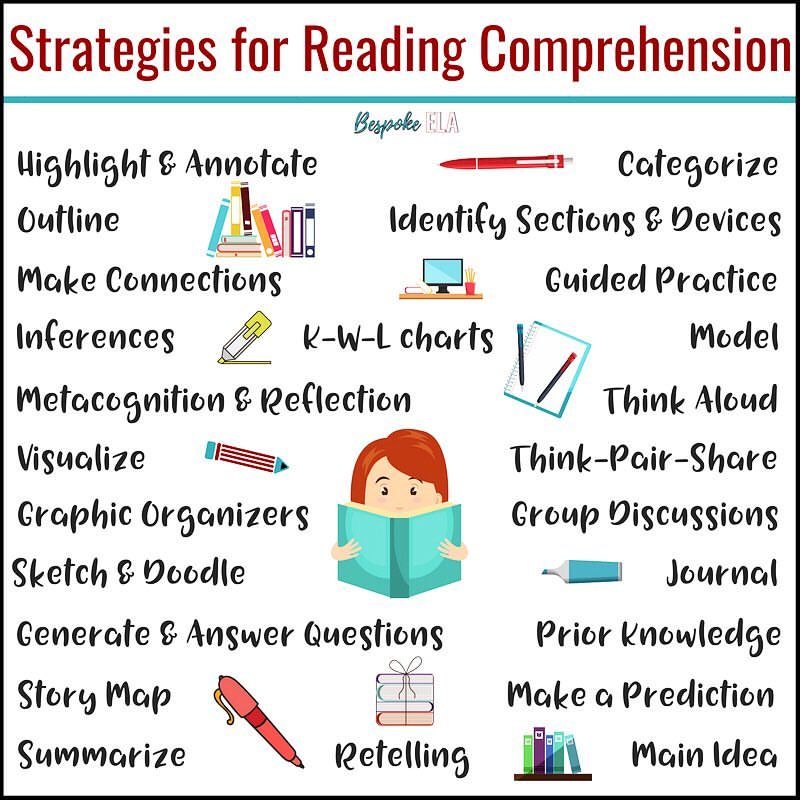

The concept of “semantic reading strategies”

Semantic reading strategies — various combinations of techniques that students use to perceive graphically designed textual information, as well as its processing into personal-semantic attitudes in accordance with the communicative-cognitive task.

According to N. Smetannikova's definition, "the way, the reader's program of actions for processing various information of the text is a strategy." Reading strategies are an algorithm of mental actions and operations in working with text. By ensuring its understanding, they help to master knowledge better and faster, retain it longer, and foster a culture of reading.

According to N. Smetannikova's definition, "the way, the reader's program of actions for processing various information of the text is a strategy." Reading strategies are an algorithm of mental actions and operations in working with text. By ensuring its understanding, they help to master knowledge better and faster, retain it longer, and foster a culture of reading. N . Smetannikova distinguishes several types of semantic reading strategies:

- pre-text activity strategies;

- strategies for textual activity;

- post-text strategies;

- strategies for working with long texts;

- text compression strategies;

- general educational strategies;

- vocabulary development strategies.

N. Smetannikova gives the following list of strategies for working with different types of texts:

- strategies for working with informational text;

- strategies for working with texts of persuasive-reasoning type;

- text frame strategies;

- Reading monitoring strategy.

Description of semantic reading strategies according to N.N. Smetannikova

In fact, the technology of mastering the skill of semantic reading, proposed by N. Smetannikova, in terms of three-stage work with the text (before reading, during reading and after reading) has something in common with the ideas of G. Granik, L. Kontseva and S. Bondarenko and the creators of the technology of productive reading in the educational program "School 2100" N. N. Svetlovskaya, E. V. Buneeva and O. V. Chindilova.

Currently, about a hundred strategies are known, many of which are actively used in the educational process.

Critical thinking and semantic reading

strategies of semantic reading include technologies aimed at developing students' critical thinking .

Critical thinking means the process of correlating external information with the knowledge available to a person, making decisions about what can be accepted, what needs to be supplemented, and what should be rejected.

At the same time, situations arise when one has to correct one's own beliefs or even abandon them if they contradict new knowledge.

At the same time, situations arise when one has to correct one's own beliefs or even abandon them if they contradict new knowledge. The methodological foundations of critical thinking include three stages that should be present in the lesson in the learning process:

- challenge (motivation),

- comprehension (implementation),

- reflection (thinking).

Consistent implementation of the basic three-phase model in the classroom improves the efficiency of the pedagogical process. Technologies for the development of critical thinking, as well as strategies for the development of semantic reading, are aimed at the formation of a thoughtful reader who analyzes, compares, contrasts and evaluates familiar and new information.

Examples of the most common strategies

System-activity approach and semantic reading

System-activity approach defines the form of learning organization: learning activity.

The key concepts of learning activity are " motivation " and " action ".

The key concepts of learning activity are " motivation " and " action ". The first stage in the organization of educational activities is the creation of conditions for motivating students to activities. Motives are expressed through the cognitive interest of students. Motive implies a special selective orientation of the individual to educational activities .

Criteria of cognitive interest are:

- active involvement in learning activities,

- focus on this activity,

- students have questions that they ask each other and the teacher, or on the basis of which they formulate an information request.

Under educational actions understand specific ways of transforming educational material in the process of completing educational tasks. Learning action is an integral element of activity, transforming not only the form of information, but also translating it into an internal plan, causing a change in the student himself, his understanding of processes and phenomena, the meaning of the material being studied.

The action is performed on the basis of operations correlated with specific conditions and means. An action is a set of operations subordinate to a goal.

The action is performed on the basis of operations correlated with specific conditions and means. An action is a set of operations subordinate to a goal. The task of the teacher is to identify the appropriate learning activities in and create conditions for their mastering by students and determine the means of activity. In exemplary programs, subject goals and planned learning outcomes are concretized to the level of learning activities that students should master in learning activities to master the subject content.

The content of education is considered as a unity of knowledge, activity and development of students. Semantic reading skills are the basis for mastering the main content of education.

Screen semantic reading

It should be noted that working on the formation of a functionally literate reader, one should take into account the modern conditions in which our students live. We are talking about the technologization of all spheres of life.

International studies show a close relationship between the quality of reading in an electronic environment and the quality of reading a text presented on paper. That is, if students show high or low levels of literacy when reading on paper, then they show similar results when reading in an electronic environment.

International studies show a close relationship between the quality of reading in an electronic environment and the quality of reading a text presented on paper. That is, if students show high or low levels of literacy when reading on paper, then they show similar results when reading in an electronic environment. However, teaching screen reading requires both a theoretical rethinking of the concept of reading and the creation of new teaching methods (new technologies).

- When screen reading increases the importance of viewing, search types of reading, as well as the role of information selection during repeated reading.

- The very structure of the electronic text can be represented as hypertext. In hypertext, the direction of reading is not necessarily linear, as in printed text.

Screen reading revolutionizes the broader field of communication, putting the image on a par with writing, and the screen with a page of written text.

Learn more

- Read the 1st paragraph to yourself silently.

Pre-text strategies

Brainstorming

Brainstorming

What associations do you have about the topic? All associations are recorded. Knowledge is being updated. We read and see if the information given by you is adequate to what we learned from the text. What have you learned? They directed the reading to the search for new information, to confirm the hypotheses expressed.

Knowledge is being updated. We read and see if the information given by you is adequate to what we learned from the text. What have you learned? They directed the reading to the search for new information, to confirm the hypotheses expressed.

"Glossary"

Purpose: updating the vocabulary related to the topic

"Semantic reading strategies and working with text"

Topic, title, thesis, graph, information, table, forum, commentary, portfolio, arguments, modeling, programming, result, process, project, equipment

“Landmarks of anticipation”

Purpose: updating of previous knowledge and experience related to the topic

Before reading the text

Judgments

After reading the text

1.

2. 9004"Dissection of the question"

Purpose: a semantic guess about the possible content of the text based on the analysis of its title.

Strategies of text activities

"Reading in a circle"

Purpose: checking the understanding of the text read aloud

"Reading to yourself with questions"

Purpose: to teach to read thoughtfully by asking increasingly difficult questions.

Work in pairs.

“Reading to yourself with notes”

Purpose: monitoring the understanding of the text being read and its critical analysis. Used to work with complex scientific texts.

The reader makes notes in the margins:

+ understood - did not understand? need to discuss

+ agree - disagree !! need to discuss

Post-text strategies

"Relationship between question and answer"

Purpose: teaching text comprehension. Show the need to search for the location of the answer.

Show the need to search for the location of the answer.

Where is the answer?

in the text in the reader's head

in one in different author and me only me

preposition. parts

find connect, connect, find the answer

exactly compose compose in your own

answer (1) answer (2) answer (3) head (4)

"Questions after the text"

"B.Blum's taxonomy" classification implies a balance between groups of questions.