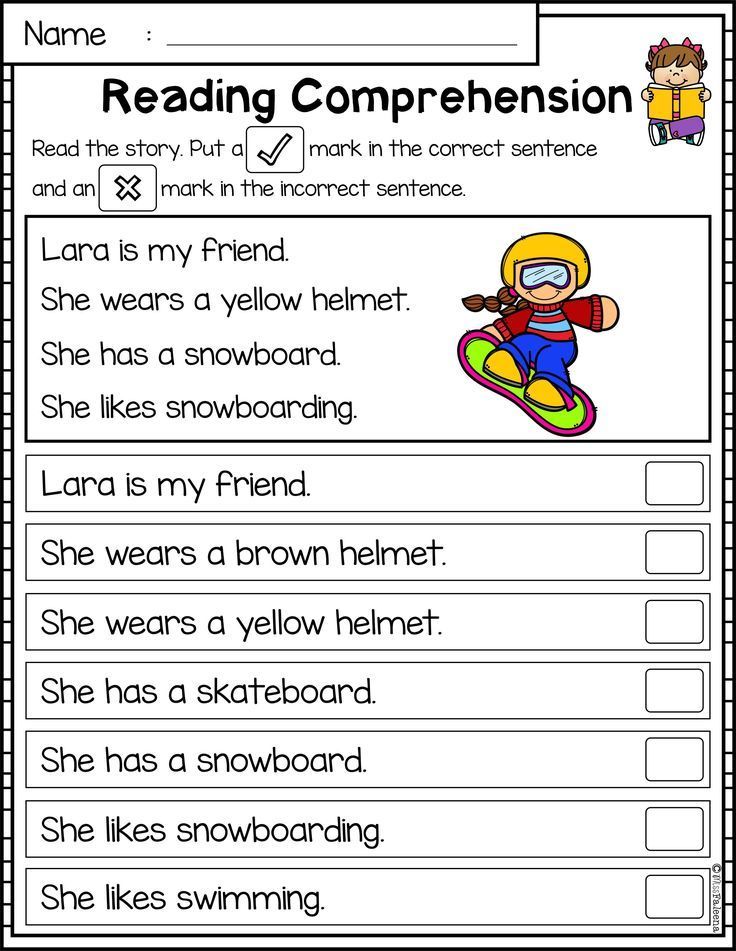

Reading skills children

Reading Development and Skills by Age

Even as babies, kids build reading skills that set the foundation for learning to read. Here’s a list of reading milestones by age. Keep in mind that kids develop reading skills at their own pace, so they may not be on this exact timetable.

Babies (ages 0–12 months)

- Begin to reach for soft-covered books or board books

- Look at and touch the pictures in books

- Respond to a storybook by cooing or making sounds

- Help turn pages

Toddlers (ages 1–2 years)

- Look at pictures and name familiar items, like dog, cup, and baby

- Answer questions about what they see in books

- Recognize the covers of favorite books

- Recite the words to favorite books

- Start pretending to read by turning pages and making up stories

Preschoolers (ages 3–4 years)

- Know the correct way to hold and handle a book

- Understand that words are read from left to right and pages are read from top to bottom

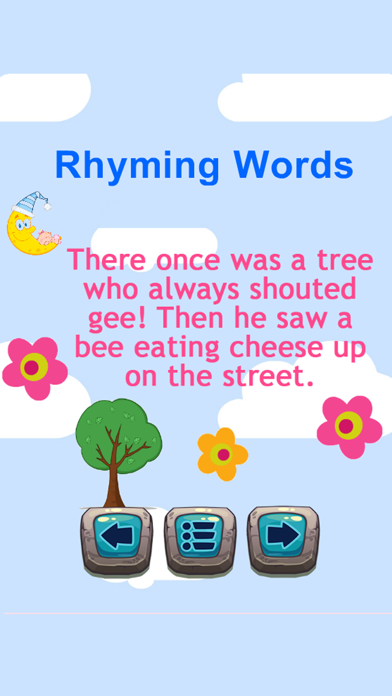

- Start noticing words that rhyme

- Retell stories

- Recognize about half the letters of the alphabet

- Start matching letter sounds to letters (like knowing b makes a /b/ sound)

- May start to recognize their name in print and other often-seen words, like those on signs and logos

Kindergartners (age 5 years)

- Match each letter to the sound it represents

- Identify the beginning, middle, and ending sounds in spoken words like dog or sit

- Say new words by changing the beginning sound, like changing rat to sat

- Start matching words they hear to words they see on the page

- Sound out simple words

- Start to recognize some words by sight without having to sound them out

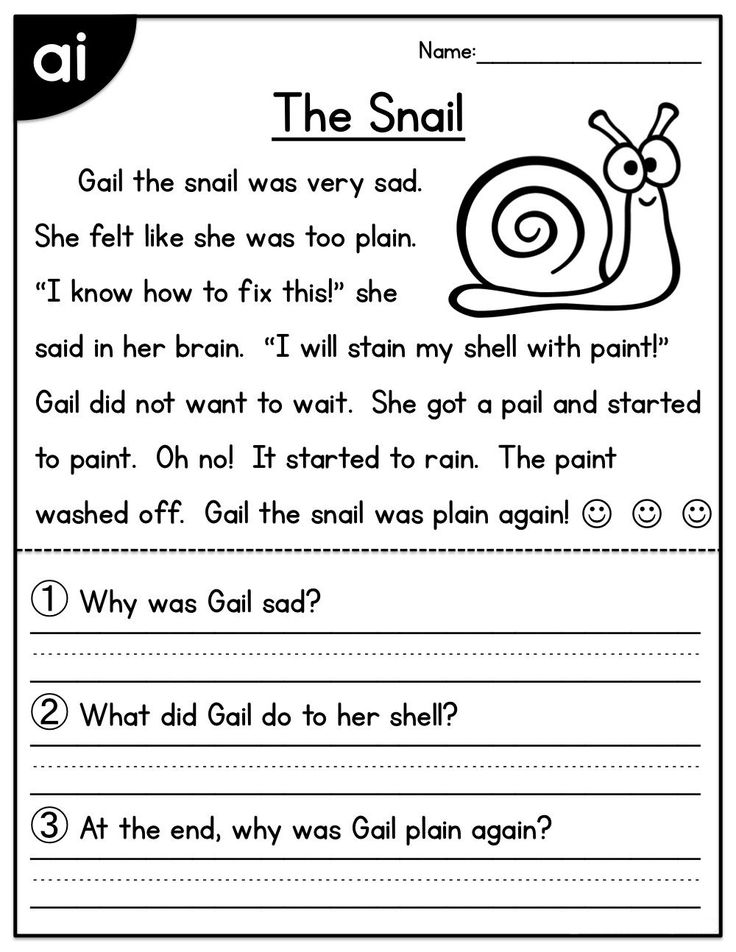

- Ask and answer who, what, where, when, why, and how questions about a story

- Retell a story in order, using words or pictures

- Predict what happens next in a story

- Start reading or asking to be read books for information and for fun

- Use story language during playtime or conversation (like “I can fly!” the dragon said.

“I can fly!”)

Younger grade-schoolers (ages 6–7 years)

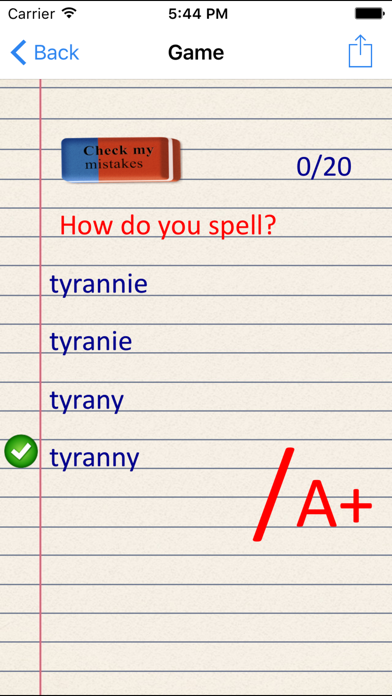

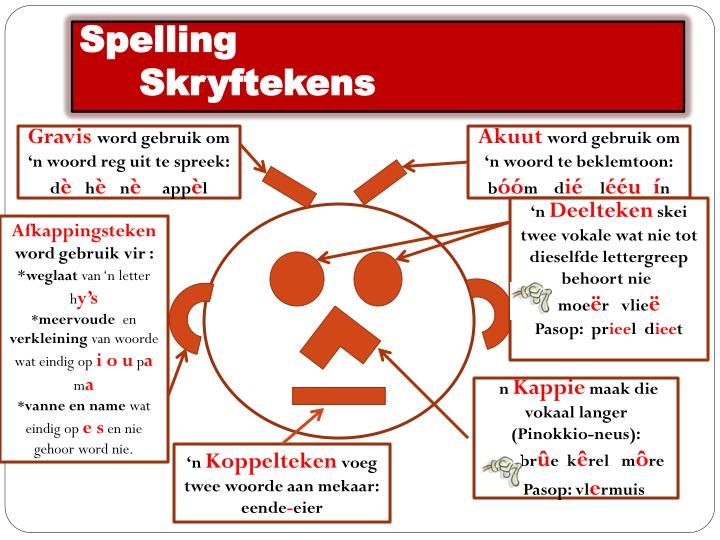

- Learn spelling rules

- Keep increasing the number of words they recognize by sight

- Improve reading speed and fluency

- Use context clues to sound out and understand unfamiliar words

- Go back and re-read a word or sentence that doesn’t makes sense (self-monitoring)

- Connect what they’re reading to personal experiences, other books they’ve read, and world events

Older grade-schoolers (ages 8–10 years)

- In third grade, move from learning to read to reading to learn

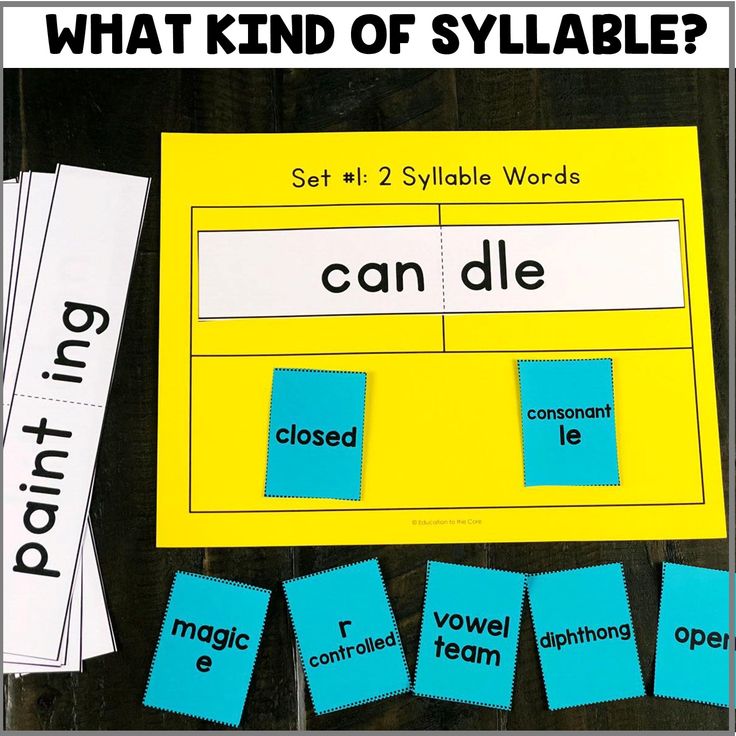

- Accurately read words with more than one syllable

- Learn about prefixes, suffixes, and root words, like those in helpful, helpless, and unhelpful

- Read for different purposes (for enjoyment, to learn something new, to figure out directions, etc.)

- Explore different genres

- Describe the setting, characters, problem/solution, and plot of a story

- Identify and summarize the sequence of events in a story

- Identify the main theme and may start to identify minor themes

- Make inferences (“read between the lines”) by using clues from the text and prior knowledge

- Compare and contrast information from different texts

- Refer to evidence from the text when answering questions about it

- Understand similes, metaphors, and other descriptive devices

Middle-schoolers and high-schoolers

- Keep expanding vocabulary and reading more complex texts

- Analyze how characters develop, interact with each other, and advance the plot

- Determine themes and analyze how they develop over the course of the text

- Use evidence from the text to support analysis of the text

- Identify imagery and symbolism in the text

- Analyze, synthesize, and evaluate ideas from the text

- Understand satire, sarcasm, irony, and understatement

Keep in mind that some schools focus on different skills in different grades. So, look at how a child reacts to reading, too. For example, kids who have trouble reading might get anxious when they have to read.

So, look at how a child reacts to reading, too. For example, kids who have trouble reading might get anxious when they have to read.

If you’re concerned about reading skills, find out why some kids struggle with reading.

Related topics

Reading and writing

How Most Children Learn to Read

By: Derry Koralek, Ray Collins

Between the ages of four and nine, your child will have to master some 100 phonics rules, learn to recognize 3,000 words with just a glance, and develop a comfortable reading speed approaching 100 words a minute. He must learn to combine words on the page with a half-dozen squiggles called punctuation into something – a voice or image in his mind that gives back meaning. (Paul Kropp, 1996)

Emerging literacy

Emerging literacy describes the gradual, ongoing process of learning to understand and use language that begins at birth and continues through the early childhood years (i. e., through age eight). During this period children first learn to use oral forms of language (listening and speaking) and then begin to explore and make sense of written forms (reading and writing).

e., through age eight). During this period children first learn to use oral forms of language (listening and speaking) and then begin to explore and make sense of written forms (reading and writing).

Listening and speaking

Emerging literacy begins in infancy as a parent lifts a baby, looks into her eyes, and speaks softly to her. It's hard to believe that this casual, spontaneous activity is leading to the development of language skills. This pleasant interaction helps the baby learn about the give and take of conversation and the pleasures of communicating with other people.

Young children continue to develop listening and speaking skills as they communicate their needs and desires through sounds and gestures, babble to themselves and others, say their first words, and rapidly add new words to their spoken vocabularies. Most children who have been surrounded by language from birth are fluent speakers by age three, regardless of intelligence, and without conscious effort.

Each of the 6,000 languages in the world uses a different assortment of phonemes – the distinctive sounds used to form words. When adults hear another language, they may not notice the differences in phonemes not used in their own language. Babies are born with the ability to distinguish these differences. Their babbles include many more sounds than those used in their home language. At about 6 to 10 months, babies begin to ignore the phonemes not used in their home language. They babble only the sounds made by the people who talk with them most often.

During their first year, babies hear speech as a series of distinct, but meaningless words. By age 1, most children begin linking words to meaning. They understand the names used to label familiar objects, body parts, animals, and people. Children at this stage simplify the process of learning these labels by making three basic assumptions:

- Labels (words) refer to a whole object, not parts or qualities (Flopsy is a beloved toy, not its head or color).

- Labels refer to classes of things rather than individual items (Doggie is the word for all four-legged animals).

- Anything that has a name can only have one name (for now, Daddy is Daddy, and not a man or Jake).

As children develop their language skills, they give up these assumptions and learn new words and meanings. From this point on, children develop language skills rapidly. Here is a typical sequence:

- At about 18 months, children add new words to their vocabulary at the astounding rate of one every 2 hours.

- By age 2, most children have 1 to 2,000 words and combine two words to form simple sentences such as: "Go out." "All gone."

- Between 24 to 30 months, children speak in longer sentences.

- From 30 to 36 months, children begin following the rules for expressing tense and number and use words such as some, would, and who.

Reading and writing

At the same time as they are gaining listening and speaking skills, young children are learning about reading and writing.

At home and in child care, Head Start, or school, they listen to favorite stories and retell them on their own, play with alphabet blocks, point out the logo on a sign for a favorite restaurant, draw pictures, scribble and write letters and words, and watch as adults read and write for pleasure and to get jobs done.

Young children make numerous language discoveries as they play, explore, and interact with others. Language skills are primary avenues for cognitive development because they allow children to talk about their experiences and discoveries. Children learn the words used to describe concepts such as up and down, and words that let them talk about past and future events.

Many play experiences support children's emerging literacy skills. Sorting, matching, classifying, and sequencing materials such as beads, a box of buttons, or a set of colored cubes, contribute to children's emerging literacy skills. Rolling playdough and doing fingerplays help children strengthen and improve the coordination of the small muscles in their hands and fingers. They use these muscles to control writing tools such as crayons, markers, and brushes.

They use these muscles to control writing tools such as crayons, markers, and brushes.

As their language skills grow, young children tell stories, identify printed words such as their names, write their names on paintings and creations, and incorporate writing in their make-believe play. After listening to a story, they talk about the people, feelings, places, things, and events in the book and compare them to their own experiences.

Reading and writing skills develop together. Children learn about writing by seeing how the print in their homes, classrooms, and communities provides information. They watch and learn as adults write – to make a list, correspond with a friend, or do a crossword puzzle. They also learn from doing their own writing.

The chart below offers examples of activities preschool and kindergarten children engage in, and describes how they are related to reading and writing.

What children might do | How it relates to reading and writing |

|---|---|

Make a pattern with objects such as buttons, beads, small colored cubes. | By putting things in a certain order, children gain an understanding of sequence. This will help them discover that the letters in words must go in a certain order. |

| Listen to a story, then talk with their families, teachers, or tutors and each other about the plot, characters, what might happen next, and what they liked about the book. | Children enjoy read-aloud sessions. They learn that books can introduce people, places, and ideas and describe familiar experiences. Listening and talking helps children build their vocabularies. They have fun while learning basic literacy concepts such as: print is spoken words that are written down, print carries meaning, and we read from left to right, from the top to the bottom of a page, and from the front to the back of a book. |

| Play a matching game such as concentration or picture bingo. | Seeing that some things are exactly the same leads children to the understanding that the letters in words must be written in the same order every time to carry meaning. |

| Move to music while following directions such as, put your hands up, down, in front, in back, to the left, to the right. Now wiggle all over. | Children gain an understanding of concepts such as up/down, front/back, and left/right, and add these words to their vocabularies. Understanding these concepts leads to knowledge of how words are read and written on a page. |

| Recite rhyming poems introduced by a parent, teacher, or tutor, and make up new rhymes on their own. | Children become aware of phonemes – the smallest units of sounds that make up words. This awareness leads to reading and writing success. |

| Make signs for a pretend grocery store. | Children practice using print to provide information – in this case, the price of different foods. |

| Retell a favorite story to another child or a stuffed animal. | Children gain confidence in their ability to learn to read. They practice telling the story in the order it was read to them – from the beginning to the middle to the end. |

| Use invented spelling to write a grocery list at the same time as a parent is writing his or her own list. | Children use writing to share information with others. By watching an adult write, they are introduced to the conventions of writing. Using invented spelling encourages phonemic awareness. |

| Sign their names (with a scribble, a drawing, some of the letters, or "correctly") on an attendance chart, painting, or letter. | Children are learning that their names represent them and that other words represent objects, emotions, actions, and so on. They see that writing serves a purpose to let their teacher know they have arrived, to show others their art work, or to tell someone who sent a letter. |

Becoming readers and writers

By the time most children leave the preschool years and enter kindergarten, they have learned a lot about language. For five years, they have watched, listened to, and interacted with adults and other children. They have played, explored, and made discoveries at home and in child development settings such as Head Start and child care.

They have played, explored, and made discoveries at home and in child development settings such as Head Start and child care.

Kindergarten

Beginning or during kindergarten, most children have naturally developed language skills and knowledge. They…

Know print carries meaning by:

- Turning pages in a storybook to find out what happens next

- "writing" (scribbling or using invented spelling) to communicate a message

- Using the language and voice of stories when narrating their stories

- Dictating stories

Know what written language looks like by:

- Recognizing that words are combinations of letters

- Identifying specific letters in unfamiliar words

- Writing with "mock" letters or writing that includes features of real letters

Can identify and name letters of the alphabet by:

- Saying the alphabet

- Pointing out letters of the alphabet in their own names and in written texts

Know that letters are associated with sounds by:

- Finger pointing while reading or being read to

- Spelling words phonetically, relating letters to the sounds they hear in the word

Know the sounds that letters make by:

- Naming all the objects in a room that begin with the same letter

- Pointing to words in a text that begin with the same letter

- Picking out words that rhyme

- Trying to sound out new or unfamiliar words while reading out loud

- Representing words in writing by their first sound (e.

g., writing d to represent the word dog)

g., writing d to represent the word dog)

Know using words can serve various purposes by:

- Pointing to signs for specific places, such as a play area, a restaurant, or a store

- Writing for different purposes, such as writing a (pretend) grocery list, writing a thank-you letter, or writing a menu for play

Know how books work by:

- Holding the book right side up

- Turning pages one at a time

- Reading from left to right and top to bottom

- Beginning reading at the front and moving sequentially to the back

Because children have been learning language since birth, most are ready to move to the next step – mastering conventional reading and writing. To become effective readers and writers children need to:

- Recognize the written symbols letters and words used in reading and writing

- Write letters and form words by following conventional rules

- Use routine skills and thinking and reasoning abilities to create meaning while reading and writing

The written symbols we use to read and write are the 26 upper and lower case letters of the alphabet. The conventional rules governing how to write letters and form words include writing letters so they face in the correct direction, using upper and lower case versions, spelling words correctly, and putting spaces between words.

The conventional rules governing how to write letters and form words include writing letters so they face in the correct direction, using upper and lower case versions, spelling words correctly, and putting spaces between words.

Routine skills refer to the things readers do automatically, without stopping to think about what to do. We pause when we see a comma or period, recognize high-frequency sight words, and use what we already know to understand what we read. One of the critical routine skills is phonemic awareness – the ability to associate specific sounds with specific letters and letter combinations.

Research has shown that phonemic awareness is the best predictor of early reading skills. Phonemes, the smallest units of sounds, form syllables, and words are made up of syllables. Children who understand that spoken language is made up of discrete sounds – phonemes and syllables – find it easier to learn to read.

Many children develop phonemic awareness naturally, over time. Simple activities such as frequent readings of familiar and favorite stories, poems, and rhymes can help children develop phonemic awareness. Other children may need to take part in activities designed to build this basic skill.

Simple activities such as frequent readings of familiar and favorite stories, poems, and rhymes can help children develop phonemic awareness. Other children may need to take part in activities designed to build this basic skill.

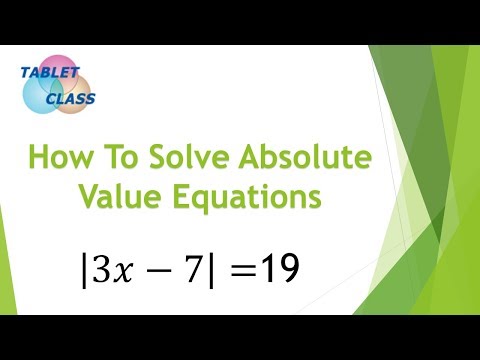

Thinking and reasoning abilities help children figure out how to read and write unfamiliar words. A child might use the meaning of a previous word or phrase, look at a familiar prefix or suffix, or recall how to pronounce a letter combination that appeared in another word.

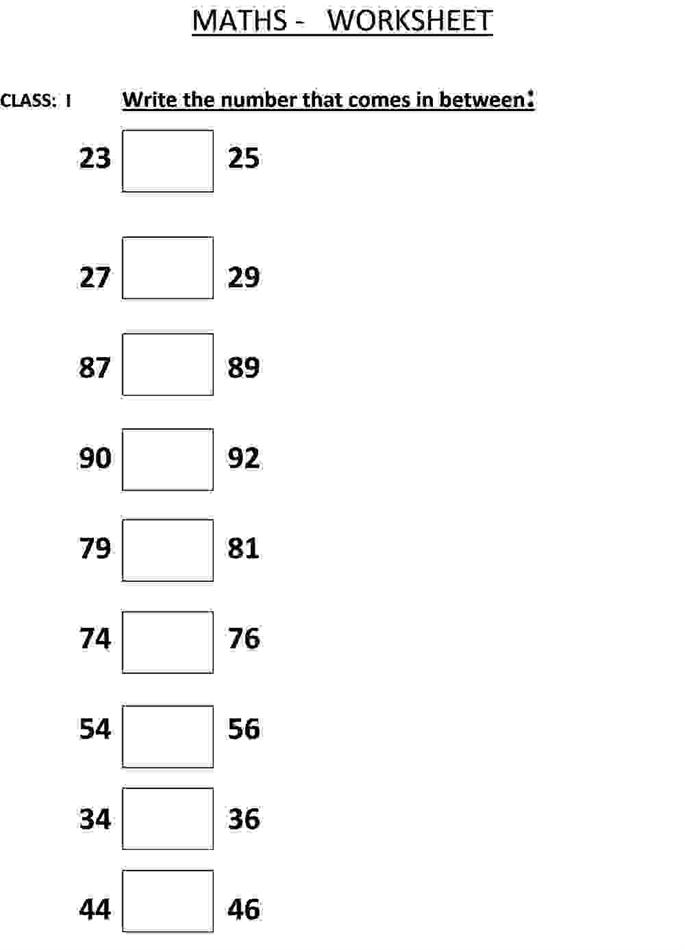

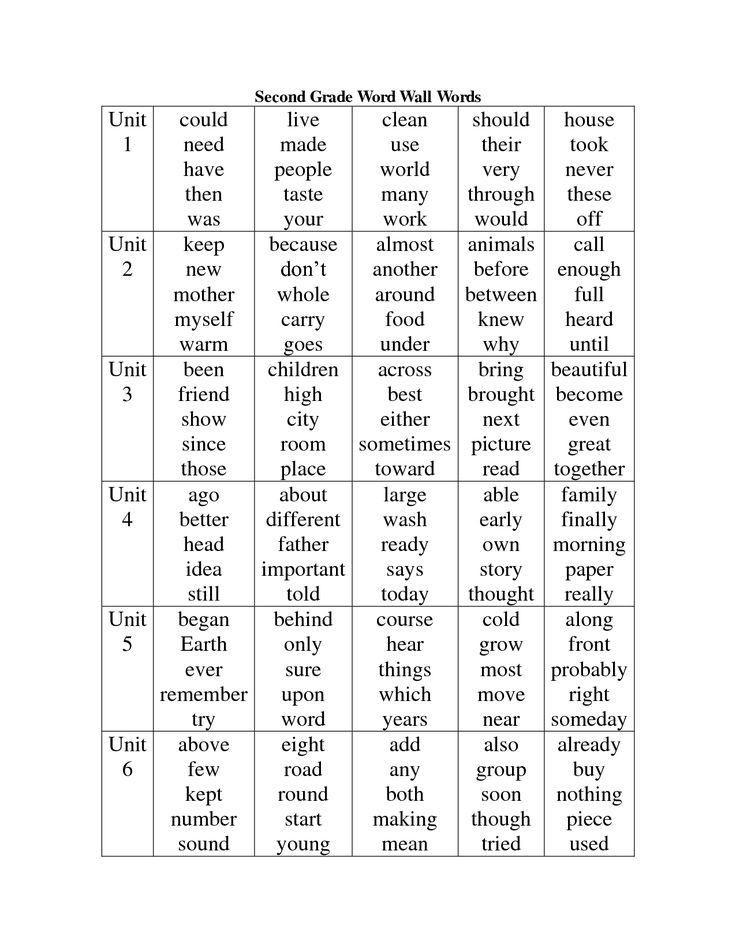

First and second grades

By the time most children have completed the first and second grades, they have naturally developed the following language skills and knowledge. They…

Improve their comprehension while reading a variety of simple texts by:

- Thinking about what they already know

- Creating and changing mental pictures

- Making, confirming, and revising predictions

- Rereading when confused

Apply word-analysis skills while reading by:

- Using phonics and simple context clues to figure out unknown words

- Using word parts (e.

g., root words, prefixes, suffixes, similar words) to figure out unfamiliar words

g., root words, prefixes, suffixes, similar words) to figure out unfamiliar words

Understand elements of literature (e.g., author, main character, setting) by:

- Coming to a conclusion about events, characters, and settings in stories

- Comparing settings, characters, and events in different stories

- Explaining reasons for characters acting the way they do in stories

Understand the characteristics of various simple genres (e.g., fables, realistic fiction, folk tales, poetry, and humorous stories) by:

- Explaining the differences among simple genres

- Writing stories that contain the characteristics of a selected genre

Use correct and appropriate conventions of language when responding to written text by:

- Spelling common high-frequency words correctly

- Using capital letters, commas, and end punctuation correctly

- Writing legibly in print and/or cursive

- Using appropriate and varied word choice

- Using complete sentences

The chart below offers examples of activities children engage in and describes how they are related to reading and writing.

What children might do | How it relates to reading and writing |

|---|---|

| Discuss the rules for an upcoming field trip, watch their teacher write them on a large sheet of paper, and join in when she reads the rules aloud. | Children experience first-hand how different forms of language – listening, speaking, reading, and writing – are connected. They see language used for a purpose, in this case to prepare for their field trip. They see their words written down and hear them read aloud. |

| Look in a book to find the answer to a question. | Children know that print provides information. They use books as a resource to learn about the world. |

| Read and reread a book independently for several days after the teacher reads it aloud to the class. | Children read and reread the book because it's fun and rewarding. They can recall some of the words the teacher reads aloud and figure out others because they remember the sequence and meaning of the story. They can recall some of the words the teacher reads aloud and figure out others because they remember the sequence and meaning of the story. |

| Read some words easily without stopping to decode them. | Children gradually build a sight vocabulary that includes a majority of the words used most often in the English language. They can read these words automatically. |

| Read words they have never seen before. | Children use what they already know about letter combinations, root words, prefixes, suffixes, and clues in the pictures or story to figure out new words. |

| Use new words while talking and writing. | Children build their vocabularies by reading and talking, sharing ideas, discussing a question, listening to others talk, and exploring their interests. Using new words helps them fully understand the meaning of the words. |

Recognize their own spelling mistakes and ask for help to make corrections. | Children understand that spelling is not just matching sounds with letters. They are learning the basic rules that govern spelling and the exceptions to the rules. |

| Ask questions about what they read. | Children understand that there is more to reading than pronouncing words correctly. They may ask questions to clarify what they have read or to learn more about the topic. |

| Choose to read during free time at home, at school, and in out-of-school programs. | Children learn to enjoy reading independently, particularly when they can read books of their own choosing. The more children read, the better readers they become. |

Key points about development

- Children develop in four, interrelated areas – cognitive and language, physical, social, and emotional.

- Most children follow the same sequence and pattern for development, but do so at their own pace.

- Language skills are closely tied to and affected by cognitive, social, and emotional development.

- Children first learn to listen and speak, then use these and other skills to learn to read and write.

- Children's experiences and interactions in the early years are critical to their brain development and overall learning.

- Emerging literacy is the gradual, ongoing process of learning to understand and use language.

- Children make numerous language discoveries as they play, explore, and interact with others.

- Children build on their language discoveries to become conventional readers and writers.

- Effective readers and writers recognize letters and words, follow writing rules, and create meaning from text.

- Successful programs to promote children's reading and literacy development should be based on an understanding of child development, recent research on brain development, and the natural ongoing process through which most young children acquire language skills and become readers and writers.

Formation of reading skills in children: stages and exercises

Primary school is a special stage in the life of any child, which is associated with the formation of the basics of his ability to learn, the ability to organize his activities. It is a full-fledged reading skill that provides the student with the opportunity to independently acquire new knowledge, and in the future creates the necessary basis for self-education in subsequent education in high school and after school.

It is a full-fledged reading skill that provides the student with the opportunity to independently acquire new knowledge, and in the future creates the necessary basis for self-education in subsequent education in high school and after school.

Interest in reading arises when a child is fluent in conscious reading, while he has developed educational and cognitive motives for reading. Reading activity is not something spontaneous that arises on its own. To master it, it is important to know the ways of reading, the methods of semantic text processing, as well as other skills.

Reading is a complex psychophysiological process in which visual, speech-auditory and speech-motor analyzers take part. A child who has not learned to read or does it poorly cannot comprehend the necessary knowledge and use it in practice. If the child can read, but at the same time he does not understand what he read, then this will also lead to great difficulties in further learning and, as a result, failure at school.

Reading begins with visual perception, discrimination and recognition of letters. This is the basis on the basis of which the letters are correlated with the corresponding sounds and the sound-producing image of the word is reproduced, i.e. his reading. In addition, through the correlation of the sound form of the word with its meaning, the understanding of what is read is carried out.

Stages of developing reading skills

T.G. Egorov identifies several stages in the formation of reading skills:

- Acquisition of sound-letter designations.

- Reading by syllable.

- The formation of synthetic reading techniques.

- Synthetic reading.

The mastery of sound-letter designations occurs throughout the entire pre-letter and literal periods. At this stage, children analyze the speech flow, sentence, divide it into syllables and sounds. The child correlates the selected sound from speech with a certain graphic image (letter).

Having mastered the letter, the child reads the syllables and words with it. When reading a syllable in the process of merging sounds, it is important to move from an isolated generalized sound to the sound that the sound acquires in the speech stream. In other words, the syllable must be pronounced as it sounds in oral speech.

At the stage of syllable-by-syllable reading, the recognition of letters and the merging of sounds into syllables occurs without any problems. Accordingly, the unit of reading is the syllable. The difficulty of synthesizing at this stage may still remain, especially in the process of reading long and difficult words.

The stage of formation of synthetic reading techniques is characterized by the fact that simple and familiar words are read holistically, but complex and unfamiliar words are read syllable by syllable. At this stage, frequent replacements of words, endings, i.e. guessing reading takes place. Such errors lead to a discrepancy between the content of the text and the read.

The stage of synthetic reading is characterized by the fact that the technical side of reading is no longer difficult for the reader (he practically does not make mistakes). Reading comprehension comes first. There is not only a synthesis of words in a sentence, but also a synthesis of phrases in a general context. But it is important to understand that understanding the meaning of what is read is possible only when the child knows the meaning of each word in the text, i.e. Reading comprehension directly depends on the development of the lexico-grammatical side of speech.

Features of the formation of reading skills

There are 4 main qualities of reading skill:

- Correct. By this is understood the process of reading, which occurs without errors that can distort the general meaning of the text.

- Fluency. This is reading speed, which is measured by the number of printed characters that are read in 1 minute.

- Consciousness.

It implies understanding by the reader of what he reads, artistic means and images of the text.

It implies understanding by the reader of what he reads, artistic means and images of the text. - Expressiveness. It is the ability by means of oral speech to convey the main idea of the work and one's personal attitude to it.

Accordingly, the main task of teaching reading skills is to develop these skills in schoolchildren.

All education in the primary grades is based on reading lessons. If the student has mastered the skill of reading, speaking and writing, then other subjects will be given to him much easier. Difficulties during training arise, as a rule, due to the fact that the student could not independently obtain information from books and textbooks.

Methods and exercises for developing reading skills

In educational practice, there are 2 fundamentally opposite methods of teaching reading - linguistic (the method of whole words) and phonological.

Linguistic method teaches the words that are most commonly used, as well as those that are read the same as they are written. This method is aimed at teaching children to recognize words as whole units, without breaking them into components. The child is simply shown and said the word. After about 100 words have been learned, the child is given a text in which these words are often found. In our country, this technique is known as the Glenn Doman method.

This method is aimed at teaching children to recognize words as whole units, without breaking them into components. The child is simply shown and said the word. After about 100 words have been learned, the child is given a text in which these words are often found. In our country, this technique is known as the Glenn Doman method.

The phonetic approach is based on the alphabetical principle. Its basis is phonetics, i.e. learning to pronounce letters and sounds. As knowledge is accumulated, the child gradually moves to syllables, and then to whole words.

Reading begins with visual perception, discrimination and recognition of letters. This is the basis on the basis of which the letters are correlated with the corresponding sounds and the sound-producing image of the word is reproduced, i.e. his reading. In addition, through the correlation of the sound form of the word with its meaning, the understanding of what is read is carried out.

In addition, there are several other methods:

- Zaitsev method .

It involves teaching children warehouses as units of language structure. A warehouse is a pair of a consonant and a vowel (either a consonant and a hard or soft sign, or one letter). Warehouses are written on different faces of the cube, which differ in size, color, etc.

It involves teaching children warehouses as units of language structure. A warehouse is a pair of a consonant and a vowel (either a consonant and a hard or soft sign, or one letter). Warehouses are written on different faces of the cube, which differ in size, color, etc. - Moore method. Learning begins with sounds and letters. The whole process is carried out in a specially equipped room, where there is a typewriter that makes sounds and names of punctuation marks and numbers when a certain key is pressed. Next, the child is shown a combination of letters that he must type on a typewriter.

- Montessori method. It involves teaching children the letters of the alphabet, as well as the ability to recognize, write and pronounce them. After they learn how to combine sounds into words, they are encouraged to combine words into sentences. The didactic material consists of letters that are cut out of rough paper and pasted onto cardboard plates. The child repeats the sound after the adult, after which he traces the outline of the letter with his finger.

- Soboleva O.L. This method is based on the “bihemispheric” work of the brain. By learning letters, children learn them through recognizable images or characters, which makes it especially easy for children with speech disorders to learn and remember letters.

There is no universal methodology for developing reading skills. But in modern teaching methods, a general approach is recognized when learning begins with an understanding of sounds and letters, i.e. from phonetics.

There are certain exercises that help build reading skills. Here are a few of them:

- Reading lines backwards letter by letter. The exercise contributes to the development of letter-by-letter analysis. The meaning is simple - the words are read in reverse order, i.e. from right to left.

- Reading through the word. You do not need to read all the words in a sentence, but jumping over one.

- Reading dotted words. Words are written on the cards, but some letters are missing (dotted lines are drawn instead).

- Read only the second half of the word. Read only the second part of the word, the first part is omitted. The exercise contributes to the understanding that the second part of the word is no less important than the first, thereby preventing the omission (or reading with distortion) of the endings of words in the future.

- Reading lines with the upper half covered. A sheet of paper is superimposed over the text so that the top of the stitching is covered.

- Fast and multiple repetition. The child should repeat a line of a poem or a sentence aloud as quickly as possible and several times in a row. Correct pronunciation is extremely important, so if necessary, you need to stop and correct the child.

- Find the words in the text. The child is faced with the task of finding words in the text as quickly as possible.

First, they are shown in pictures, then voiced by the teacher.

First, they are shown in pictures, then voiced by the teacher. - Buzzing reading. The text is read by all students aloud, but in an undertone.

A. Herzen wrote: “Without reading, there is no real education, no, and there can be neither taste, nor style, nor the many-sided breadth of understanding.”

Indeed, mastering a full-fledged reading skill is the most important condition for success in basic subjects at school. At the same time, this is one of the main ways of obtaining information, which is vital for the speech, mental and aesthetic development of children.

____________________________________________

We are waiting for you in our speech center! We are always glad to you and your kids.

Call us: 8 (962) 758-53-62, 8 (909) 391-08-08

5 Key Skills to Master Reading

Teachers and parents today are fortunate to have access to a wealth of evidence-based research on what works in teaching children to read.

Because of this, we know that teaching children to read, their ability to learn and become proficient readers, depends on the five key skills that we bring you today.

From birth

The level of literacy of children begins to form long before the child goes to school. Even the youngest children can begin to be prepared to successfully learn to read. Studies conducted have identified skills that are important for literacy development:

-

knowledge of the sound of letters

-

knowledge of letter names

-

speech sound control

-

remembering what was heard

Childhood

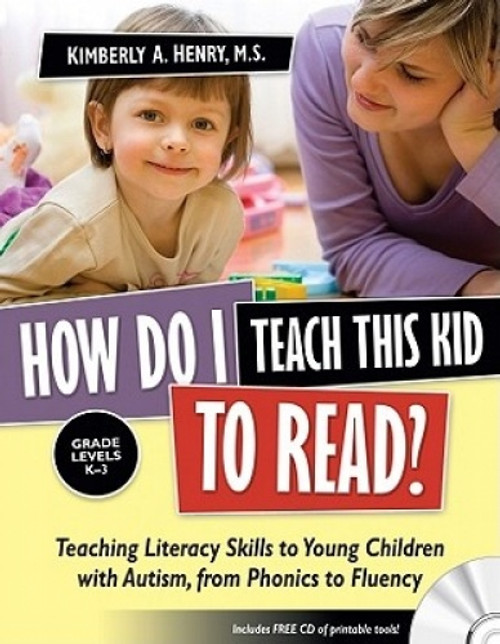

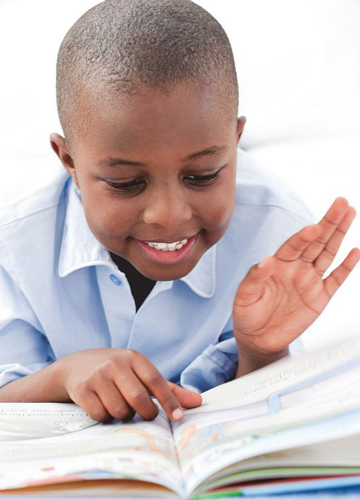

From kindergarten through grade 3, young readers actively develop all five key reading skills, from phonemic awareness to reading comprehension. Studies have shown that learning to read during this period requires a certain combination of techniques and strategies. Teachers and parents must understand how children learn and must adapt teaching methods to the individual student's abilities.

This is especially important when it comes to children who have difficulty learning to read.

1. Phonemic perception is the ability to perceive a word as a sequence of phonemes - the smallest units of sound that affect the meaning of words. Phonemes are speech sounds represented by the letters of the alphabet.

2. Phoneme decoding - the ability to identify new words by rebuilding groups of letters back into the sounds they represent, link them into a word and learn its meaning.

As challenging as reading is, thanks to advances in neuroscience and technology, we can now target key learning centers in the brain and identify areas and neural pathways that the brain uses to read. Not only do we understand why experienced readers read well and novice readers struggle with reading, but we can also help any reader on the journey from early language acquisition to reading and reading comprehension - it all happens in the brain.

Adolescence

Although the child has already mastered the skills of phonemic perception and decoding, reading comprehension difficulties can often arise at this age. In middle and high school, literacy is formed not only in the language sphere, but also in the development of other disciplines. In order to prepare a student for high school, teachers and parents need to focus on developing the three skills necessary for reading: vocabulary, fluent reading, and reading comprehension.