Short boy stories

Shortboy Stories - Wattpad

#1

My Sweet Mr. Short ! by Nratqh

ARYA | AYRA Dia seorang yang hampir sempurna. Namun seperti yang digambar hanya lah ' HAMPIR ' sempurna. Kenapa ? 155 cm. Itu ketinggiannya. Itu biasa bagi perempuan ta...

Completed

- sadlove

- shortboy

- ieqahkazumi

+6 more

#2

Unluckyby Borrower62

In a distant reality, the average height of a person is 8'9, most people believe that the taller you are the more luck you bring, altho people that fall under 6 feet tal...

- shortboy

- feelingusless

- caring

+21 more

#3

Nishinoya Yuu x Reader Oneshotsby ❀ ouma kokichi no mono ❀

just a bunch of oneshots about you and the noya baby. mostly fluffs, tho. please pardon the grammatical errors. my english isn't that good and i tend to use the same wor...

Completed

- fluffs

- haikyuu

- noya

+14 more

#4

FALL OUTby Kyle Bigayan

A bubbling romance between a short boy and a tall girl who's relationship started on a wrong foot after a ball-in-the-face incident. Date started writing: some time in A...

Completed

- humor

- sliceoflife

- tallgirl

+12 more

#5

Tall Girl and Short Boyby lexicvn

High School+being different=difficult.

Completed

- shortboy

- meangirls

- bullies

+2 more

#6

Starco: Kill Or Kiss Me? |COMPLETE. ..by thegirlwithevilface

..by thegirlwithevilface

March 15,2020 C O M P L E T E D Marco Diaz and Star Butterfly are the popular comedy duo of Class II. With their different complexes such as Star being the tallest girl...

Completed

- shortboy

- enemies

- oscar

+20 more

#7

Small White Wolf (BxB)by izumi

A boyxboy werewolf story. (Wattys2018) AlfaxWerepuppy (really small wolf :p) Don't like, don't read. Maybe be cliche at some point, but I'll put in some ORIGiNAL plot t...

- jock

- boyxboy

- wattpride

+18 more

#8

Kitten Tiesby Duffudydufduf

Julian Foster, a British boy with a past. 17 years of age and still, he can't seem to forget his mistakes. Living in Wales now with his single father, Julian seems to be. ..

..

- england

- oldergirl

- britishboy

+22 more

#9

"..𝐈 ...𝐋𝐢𝐤𝐞 𝐘𝐨𝐮..."by eiiko

{ 𝕐𝕒𝕟𝕕𝕖𝕣𝕒!ℂ𝕙𝕖𝕒𝕥𝕖𝕣!𝕄𝕒𝕝𝕖 𝚇 𝕊𝕙𝕪!𝕄𝕒𝕝𝕖 𝚇 ℝ𝕖𝕒𝕕𝕖𝕣 } .... " .. Why I changed her.. She look more good like this.. I want her.." .... &qu...

- tomboykinda

- fem

- yanderathing

+8 more

#10

Looking up to you | Hinata Shoyo x...by 𝑾𝑨𝑺𝑺𝑼𝑷

[Ongoing] ❝ 𝘌𝘷𝘦𝘯 𝘵𝘩𝘰𝘶𝘨𝘩 𝘐'𝘮 𝘵𝘢𝘭𝘭𝘦𝘳 𝘵𝘩𝘢𝘯 𝘴𝘩𝘰𝘺𝘰, 𝘐 𝘴𝘵𝘪𝘭𝘭 𝘭𝘰𝘰𝘬 𝘶𝘱 𝘵𝘰 𝘩𝘪𝘮 . ❞ 𝘪𝘯 𝘸𝘩𝘪𝘤𝘩. . . A tall calm and composed girl...

- nishinoya

- shortboy

- tsukishima

+19 more

#11

FANTASIAby TechnosBuddy

"help me Brett. " "Save me Eddy." "Don't let go of me, Eddy." "Please leave me , Brett."

" "Save me Eddy." "Don't let go of me, Eddy." "Please leave me , Brett."

- month

- bromance

- brettyang

+12 more

#12

Lipsby redhairedotaku32

Soft 1. easy to mold, cut, compress, or fold; not hard or firm to the touch. Or 2. sympathetic, lenient, or compassionate, especially to a degree perceived as excessive;...

- makeout

- crush

- âu

+10 more

#13

The Alpha~Gay Love Storyby Lunar

Lukas has always liked girls but when a boy named Noah comes that all changes Noah is alpha and has 10 days to make Lukas fall for him can Noah make Lukas fall for him o...

- shortboy

- badboy

- nerd

+2 more

#14

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐒𝐧𝐨𝐰𝐛𝐚𝐥𝐥 '𝟖𝟒by ⓚⓐⓣ

╔══════════════════════════╗ "𝘊𝘰𝘮𝘦 𝘰𝘯, 𝘥𝘰𝘯'𝘵 𝘺𝘰𝘶 𝘸𝘢𝘯𝘯𝘢 𝘥𝘢𝘯𝘤𝘦 𝘸𝘪𝘵𝘩 𝘢 𝘤𝘩𝘦𝘦𝘳𝘭𝘦𝘢𝘥𝘦𝘳? 𝘐 𝘱𝘳𝘰𝘮𝘪𝘴𝘦 𝘐 𝘥𝘰𝘯'𝘵 𝘣𝘪𝘵𝘦. &q...

&q...

Completed

- femaleoc

- dorky

- shortboy

+16 more

#15

Imagines with h/n by Kimberly:]🕸

This story is mainly for me because this is stuff I would do with my crush if ew was dating 🤭

- oneshot

- bottom

- domreader

+3 more

#16

Something To Laugh Aboutby Luna-chan~!

Hard to say, he can't say anything. Guess it's just something to laugh about.

- happy

- mute

- anime

+13 more

#17

Average Boyby Sir_Madam

First perspective of a story that follows just another average boy. There's him and this girl, the girl he's crushing on. Figuring out how to feel and what to do takes h. ..

..

- lovestory

- student

- cute

+10 more

#18

me, him and his fatherby muahjjunie

A couple takes desperate but hilarious measures to hide their relationship from Parker's father. I do not own any images, only the story.

Completed

- romance

- comedy

- adorable

+22 more

#19

Quotes by Mystery girl

I do not own any of the quotes

- love

- shortboy

- tallboy

+8 more

#20

sweetenedby Valorant234

Gaints have reigned victorious over humans for many years,for 200 years they were in control. Humans were pets they full and well knew humans were sentient but never did...

- gaint

- shortboy

- owner

+7 more

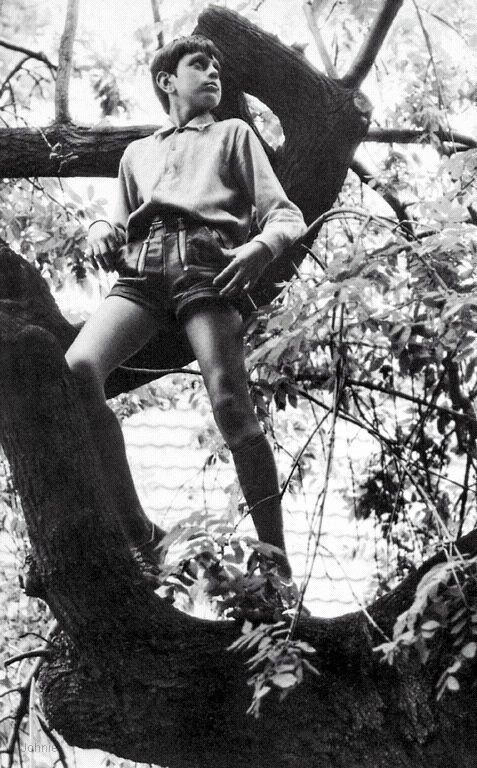

Keith Ridgway: 'The Boy,' a Short Story

The trees are living things. The grass, the clumps of ragwort, the hard full ground. All of it alive. In the sky an airplane is on its side, turning east with its belly up, its engines whining, a rumble in its wake that is felt in the gut, an additional tremble in the limbs. They are all frightened.

The grass, the clumps of ragwort, the hard full ground. All of it alive. In the sky an airplane is on its side, turning east with its belly up, its engines whining, a rumble in its wake that is felt in the gut, an additional tremble in the limbs. They are all frightened.

There are eight men. And the boy. Nine of them. There are six soldiers. The soldiers are outnumbered, and the men can count. But they can also count the guns, and although at least three of the soldiers are drunk, and one seems worse than drunk, another two are sharp and steady, with eyes that flit and rest, flit and rest, and the men know that it would be madness, it would be impossible, it would be suicide.

They are under the trees, near the edge of the meadow. They had been driven for a while, not for long, not far from the place they had been. They had stopped by the side of the road and had been ordered out of the vehicle, the truck, and they had been made to leave the road then, to leave the road that went back to what they knew. Other soldiers had stayed there, with the truck. Two had stayed. So they must have thought, the soldiers, that six were enough. That six could herd, could guard, eight others. Nine. And if the soldiers thought that, then how could the men think that it was a mistake? That they stood a chance? Who were the professionals here?

Other soldiers had stayed there, with the truck. Two had stayed. So they must have thought, the soldiers, that six were enough. That six could herd, could guard, eight others. Nine. And if the soldiers thought that, then how could the men think that it was a mistake? That they stood a chance? Who were the professionals here?

They had climbed a hill through brambles and rubbish to a wide, green meadow, and they had walked across, the soldiers at their backs, directing them. Left. Left more. There. To that line of trees. The meadow was empty, a faded green, perhaps a stream to their right as they crossed, in the distance, where the land seemed to dip and disappear. The sun had shone on them and they had talked to the boy, inasmuch as they could. Inasmuch as they could find in themselves something to say to him. Something comforting, distracting. Inasmuch as the soldiers would let them talk at all. Shut up. You. Shut up.

There had been no airplanes as they crossed the field. The men had looked for them but they did not come; they were not there. Watch where you’re going. What could they have done anyway? The senior soldier, the one in charge, he was the most nervous. He did not seem drunk, but he was not sober. He was sweating and his eyes were bloodshot and he squinted at the light and watched the sky, and he stopped every few meters to look toward the top of the meadow where perhaps there was a stream, and he seemed to want them to both move faster and never arrive.

The men had looked for them but they did not come; they were not there. Watch where you’re going. What could they have done anyway? The senior soldier, the one in charge, he was the most nervous. He did not seem drunk, but he was not sober. He was sweating and his eyes were bloodshot and he squinted at the light and watched the sky, and he stopped every few meters to look toward the top of the meadow where perhaps there was a stream, and he seemed to want them to both move faster and never arrive.

Now, though, they are in the trees. And one of the soldiers has gone ahead. They wait. The men all sit on the ground. And the soldiers sit or squat on the ground. Only the boy stands, until a soldier shouts at him, and he squats down, then sits, carefully, not unfolding his arms, which the men can see are kept crossed over his chest because he wants to stop shaking, and he cannot.

He is about, what, 8 years old. He was suddenly in their midst. They were moved from one vehicle to another, three of them, four of them, and then they were with these other men whom they did not know, and the boy. And both sets of men thought that the boy was with the others. Who is the boy? Your boy? No, is he not yours? Did he not come with you? And realizing then that none of them knew who he was. And the boy would not speak. What’s your name, kid? You’ll be all right. What’s your name? Who were you with? But he said nothing, and when they tried to ask the soldiers, the soldiers shouted at them to shut up. And yet they felt somehow that the presence of the boy changed everything. That his presence meant that they would not be killed. Everything was heading in that direction. But then there was this boy. Like a form that had been incorrectly filled in. An administrative error. Which would mean eventually that the soldiers would scratch their heads, blow out their cheeks, complain that some higher-up had made a mess, that they’d have to go back, have to take them all back, that this was wrong, that you can’t murder the men in front of the boy. And that you cannot murder the boy.

And both sets of men thought that the boy was with the others. Who is the boy? Your boy? No, is he not yours? Did he not come with you? And realizing then that none of them knew who he was. And the boy would not speak. What’s your name, kid? You’ll be all right. What’s your name? Who were you with? But he said nothing, and when they tried to ask the soldiers, the soldiers shouted at them to shut up. And yet they felt somehow that the presence of the boy changed everything. That his presence meant that they would not be killed. Everything was heading in that direction. But then there was this boy. Like a form that had been incorrectly filled in. An administrative error. Which would mean eventually that the soldiers would scratch their heads, blow out their cheeks, complain that some higher-up had made a mess, that they’d have to go back, have to take them all back, that this was wrong, that you can’t murder the men in front of the boy. And that you cannot murder the boy.

The youngest of the soldiers scares the men the most. He is drunk. He carries a flask and sips from it, cradling his gun, staring at them while he does so. He is skinny. His head and his arms jerk as if there is some stiffness in his body, which might be fear or anger. It is probably fear. The men are managing their fear. Their minds are working and their eyes dart but they are trying very hard not to make any movements that are not ponderous, that do not seem entirely unthreatening. They are trying to appear lazy, slow. Their minds have never worked harder; their bodies are scared.

Or perhaps the senior soldier scares them the most. He is looking into the woods where the soldier went ahead. He squats, leaning on his gun, looking off through the trees. He is middle-aged, ordinary-looking. The men wonder if they can talk to him, reason with him. What are you doing? How can you do this? How can this be right? They think that if they can form a good argument, something that appeals to him as a man, perhaps as a father, or as a brother, or as … at least as a man, that he will be persuaded. Run, go, fend for yourselves, he will tell them, and tell them that if they are caught, they will be shot. But they know that he is a professional. He looks away from them. He looks ahead. He squats, and his back is to them and he is paid a wage and he is patriotic and does his duty and is not a coward, not a traitor, not a sentimentalist, not any of those things that the other soldiers might think of him if he let them go. The men form their arguments. But they wait.

Run, go, fend for yourselves, he will tell them, and tell them that if they are caught, they will be shot. But they know that he is a professional. He looks away from them. He looks ahead. He squats, and his back is to them and he is paid a wage and he is patriotic and does his duty and is not a coward, not a traitor, not a sentimentalist, not any of those things that the other soldiers might think of him if he let them go. The men form their arguments. But they wait.

The youngest soldier shuffles closer to one of his comrades and mutters. He is agitated. He seems to be asking where the other soldier—the one who went ahead—has got to. The senior soldier, without turning around, tells him to shut up.

And what if they are wrong, the men? What if they are not going to be shot? The boy is there. The sun. A meadow. There is a stream just out of sight. Who would shoot them? The young drunken soldier who is as scared as them? The ordinary middle-aged man? Who would do that? They are being taken to another place. As prisoners. They are being moved. That must be it. They are valuable. They can be traded.

As prisoners. They are being moved. That must be it. They are valuable. They can be traded.

And if they are wrong, and even if they are right, why scare the boy more by pleading for their lives? Why? Why do that?

The boy looks at no one. He looks at the ground. The men think that maybe he is small enough, nimble enough, perhaps the trees are dense enough, maybe if he runs he will get away, dodging his way through the forest, through the woods, running, ducking, maybe he can make it. But none of them knows how to say this to him. None of them knows how to make him understand that he might try. Even if they could say it to him, they are scared that he would still be shot, shot as he ran, and that they, then, they would be responsible. And perhaps they would be led to another place, or back to the truck, back to the town, released, and the boy would be dead.

These thoughts are like the heat. They are dense and thorough and they come but do not go. Fear is the slowest use of time, the largest part of death. It is a trap, like a leg trap, a claw, one of those, where you cannot move and suddenly the time you have left is all the time that is left in the universe.

It is a trap, like a leg trap, a claw, one of those, where you cannot move and suddenly the time you have left is all the time that is left in the universe.

They do not know what he is thinking. The boy. Sometimes he will glance at one of the men, or at one of the soldiers. Very quickly. It is possible to see his eyes picking out the position of everyone around him, picking out the guns, picking out the trees, the sky, in tiny darting glances, mapping out his situation, the fear on his face at times looking to the men like it might in fact be courage, determination, cunning. Maybe he is thinking about running. But he is so tense. Maybe that is good. Maybe he is like a spring. But he is shaking so much. Maybe that is anger.

They try to talk to him. They do not know what to say. The soldiers tell them to shut up.

There is a shout nearby and the soldiers throw themselves down flat, and the men are doing the same when there is another shout, and the soldiers shout back, and sit back up and put their guns up again and laugh. Another group of soldiers passes close by. There are about 10 of them. One of them is the soldier who had gone ahead. He comes back. The boy has started to cry, the men notice. He is silent, but his face is wet and his nose is messy and his shoulders rise and fall. The passing soldiers are shouting, complaining about the heat. They shout about shovels and digging. They shout something about clothes. They are, some of them, carrying sacks. Black plastic sacks. They become quieter and then they disappear.

Another group of soldiers passes close by. There are about 10 of them. One of them is the soldier who had gone ahead. He comes back. The boy has started to cry, the men notice. He is silent, but his face is wet and his nose is messy and his shoulders rise and fall. The passing soldiers are shouting, complaining about the heat. They shout about shovels and digging. They shout something about clothes. They are, some of them, carrying sacks. Black plastic sacks. They become quieter and then they disappear.

The men speak to the boy. The soldiers shout at them. They make a decision, the men. They decide to continue to speak to the boy. He is crying, gasping for breath; he is as tense as a dry twig and they are afraid he might snap and turn to dust, so they speak to him. Hey, kid. You like playing? You like hide-and-seek games? What sort of games do you like? You like “I spy” games? The youngest soldier stands suddenly and walks toward the boy but the senior soldier shouts something and he stops. Let them talk. He stops, the youngest soldier. On his face is a terrible sort of hatred for the boy, and for the men, and for the senior soldier, and for himself. He wants nothing more than to raise his rifle and shoot the boy, or raise it and use the butt to hit the boy and hit him again, and again, not only until the boy is dead—the boy will die on the second blow—but until his anger is dead, and then until he has the courage to stop, or until exhaustion stops him. But he stands; he stares at the boy. He stares at the men. He turns and goes back and sits down again.

Let them talk. He stops, the youngest soldier. On his face is a terrible sort of hatred for the boy, and for the men, and for the senior soldier, and for himself. He wants nothing more than to raise his rifle and shoot the boy, or raise it and use the butt to hit the boy and hit him again, and again, not only until the boy is dead—the boy will die on the second blow—but until his anger is dead, and then until he has the courage to stop, or until exhaustion stops him. But he stands; he stares at the boy. He stares at the men. He turns and goes back and sits down again.

What games do you like? I have a son; when he was your age, we used to try to count the trees in the woods when we went walking. Do you count trees? It’s hard to do. It’s difficult. You begin, and you count, but there are so many, and then you wonder, Have I counted that one already? Have I counted that one? Or this other game. Don’t look at your shoe. And now I ask you—what color is your shoe? What color are the laces? What color are the things at the side? The stripes. How many holes are there for the laces? You’re not allowed to look. You have to remember.

How many holes are there for the laces? You’re not allowed to look. You have to remember.

They think, the men, that the senior soldier will hear them, listen to them. That he will hear about their lives, hear the sort of men they are, and that it will go in their favor. And they think that they are perhaps persuading him, indirectly.

They do not crowd the boy with their voices. They take turns. They try to gauge if one voice works any better than another. The boy begins to look at whoever is speaking. That is progress, they think. That is something. But he doesn’t speak. Perhaps he cannot. Or perhaps he is foreign? Who knows? But they make their voices gentle. Even the men who do not have voices that are accustomed to children. They make their eyes soft, their faces kindly; they try, all of them, they try to calm him.

They watch, too, the back of the senior soldier. They look for a change. They look for a softening in the muscles of his back. Perhaps if they mention again their own sons? Their own daughters? Perhaps. They watch. The boy, his face; the senior soldier, his back.

They watch. The boy, his face; the senior soldier, his back.

They try to think of games. Some of them, in remembering games, in seeing the boy’s eyes look directly into theirs, remember the children that they played them with, and this brings them distress and the heat is thick even in the forest, as if another forest. The woods. They remember their own children. Some of them feel that they will never see their own children again. Some of them feel that they certainly will, that they certainly will, that life continues until it stops, that where there’s life … They look at the boy, some of the men, and he looks back at them, and they see their own children. Or they see their nephews, their nieces, their grandchildren, the children of their friends, their neighbors, or they see themselves, the children they were; they see in the boy the boy that they remember. And as the soldiers stir and stand and call, they want, more than anything else, for the boy to live, even if they don’t. That is all.

Some of the soldiers that passed by have come back. Why? Why have they done that? Four of them have come back. Now the men are outnumbered. They could have. They could have tried. But not now. Perhaps if they had tried, the boy might have gotten away. In the confusion. The boy. But now. If they.

There are too many possibilities.

He might have lived. He might yet. They will die. But they might not. Maybe they have got it all wrong. Everything is not becoming smaller. Everything is becoming bigger. More complicated. They have lost their chance. Haven’t they? The chance they might have taken when things were simpler, when life was simpler, but the boy at least has stopped crying. He has said nothing. But he looks at the men now; he looks into their eyes. He is stiller. He seems a little calmer. So perhaps.

The soldiers stand, shout at them, get them to stand up, and the men’s thoughts become a concentration on nothing, a sort of void, but it is not that; it is simply that time has started to fail for them now. They all stand. They put a hand on the boy’s shoulder as he too stands, and they can feel the tremble in him like music in the distance, like something coming, but there is nothing coming, and the soldiers tell them to walk, to move, to walk on, go further in, go on.

They all stand. They put a hand on the boy’s shoulder as he too stands, and they can feel the tremble in him like music in the distance, like something coming, but there is nothing coming, and the soldiers tell them to walk, to move, to walk on, go further in, go on.

And they do. And the trees come with them, and crowd in on them, and then lose interest and thin out, and they come to a clearing where there is a sharp smell as if of meat or dung or metal and the heat is precise, and they stop and see ahead a ditch or a hole in the ground and they know that they are, they are, they are where. And they look at the boy and he looks now only at them. As if in faces he can save something. As if in their eyes he can see that he is still living, and that they are still living, and that as long as he has faces to look at and faces are looking at him … maybe that’s what he is thinking; the men don’t know.

They should speak up now. It is hopeless now. They clear their throats.

The soldiers tell them to strip. What? Why? The men protest. Why? Everything? Why? But the soldiers just shout at them. Take off your clothes, all of your clothes, throw them here, put them here. One of the soldiers picks up their clothes, puts them in some bags. The clothes are all mixed up. The soldier doesn’t keep them separate. So how? So how will they get them back? How will that happen? They will be all mixed up. They will have to stand naked sorting through their clothes. Is this your shirt? Are these your boxer shorts? The small clothes. The men look at their shirts, their trousers, their underpants and socks and shoes being mixed up, being separated, combined with another man’s clothes, going into different bags. They follow their own clothes with their eyes, but they are lost.

They will be shot now, they know. They stand with their hands in front of their genitals. As if dignity is simple. They shiver in the heat. The boy looks smaller still, his legs as thin as grass, his shoulders square but tiny, like a square of cloth, like skin. But perhaps they will be spared. They have heard of fake executions. Of last-minute reprieves. They have heard of Dostoyevsky; they have read great literature; they have loved people; they have memories, homes; they have friends and lovers and enemies, but not enemies like these, but they have memories, all these memories, and they feel they should think of their lives. But maybe they will be saved. Maybe they will escape.

But perhaps they will be spared. They have heard of fake executions. Of last-minute reprieves. They have heard of Dostoyevsky; they have read great literature; they have loved people; they have memories, homes; they have friends and lovers and enemies, but not enemies like these, but they have memories, all these memories, and they feel they should think of their lives. But maybe they will be saved. Maybe they will escape.

The boy is crying again. The soldiers want them to line up. Over there. Over there. Over there is a ditch. They walk toward it; they try to keep the boy in front of them, shielded from the soldiers. He holds a hand. He takes a hand. One of the men finds himself holding the boy’s hand. Then they want him not to be in front, because of what is in the ditch. They see it first, because they are taller. So they move him back among them so that he cannot see. And this they do together. And it saves them, perhaps, from understanding fully what they have seen. And they think, as they shuffle the boy back behind them, as they walk up to the edge of the ditch, closer, to the edge, move, that this is the case, that they are not really here, that they are instead in a separate place, watching themselves. They turn so that they face the soldiers. No one tells them to do that. They do it for the boy perhaps, so that he does not see, through their legs, past them, the bodies. He turns as well.

And they think, as they shuffle the boy back behind them, as they walk up to the edge of the ditch, closer, to the edge, move, that this is the case, that they are not really here, that they are instead in a separate place, watching themselves. They turn so that they face the soldiers. No one tells them to do that. They do it for the boy perhaps, so that he does not see, through their legs, past them, the bodies. He turns as well.

The taste in the mouths of the men is a new one. The trees are so still, as if the air has gone.

The boy does a strange thing. It is. What is he doing? The men look at him. He puts his hands up. He stretches out his arms, straight up, into the air, his palms facing forward. The men look at him. What is he doing? Trying to be tall.

A game. Trying to reach a branch. He is even maybe on his tiptoes.

The soldiers all stare at the boy. But they seem divided. The young soldier is furious. Another two, the same. The rest seem lost in a slumber, lazy, forgetful, as if they don’t know where they are, or what they are doing. The senior soldier, most of all, seems sleepy.

The senior soldier, most of all, seems sleepy.

Stop it. Stop. The youngest soldier is shouting, stamping forward, his gun raised. Put your arms down. I will shoot. I will shoot.

The men pull at the boy’s arms, pull them down. He is stubborn for a moment. He resists. You’ll get yourself shot, they say to him. Stand behind us.

They are almost annoyed, the men. What does he think he’s doing? Surrendering? Giving himself up? Arranging his body in a way that he thinks can be read, and understood. As if it is a password, a secret sign. As if this gesture supersedes all other gestures, and puts an end to this. Like the games he plays, in which a certain phrase, or a tap on the shoulder, or a hand on a tree, makes him safe.

There is no time for this.

They shuffle him again, backwards, so that they stand in front of him. He should not be here. He is a child. They step in front of him. They move him behind their bodies. He stumbles. They face forward. And when they can no longer see the boy because they are looking at the soldiers, and when the soldiers can no longer see the boy because he is behind the men, then of course, of course, that is when the shooting starts.

They face forward. And when they can no longer see the boy because they are looking at the soldiers, and when the soldiers can no longer see the boy because he is behind the men, then of course, of course, that is when the shooting starts.

The soldiers don’t know how. Suddenly their guns are firing and they are holding them and that is just how it is. They shoot all the men. Some of them several times. The bullets go into their bodies. Some of them die instantly; others linger for a few seconds and see the sky go over them and then the trees are upside-down. Only one bullet hits the boy. It hits his chest, at the side. He falls backwards into the ditch and he lands on the old dead. And the new dead fall backwards into the ditch on top of him. After just one or two moments, the shooting stops and the men are all dead. The soldiers look for twitches. They cannot see the boy, hidden as he is by the dead men.

The boy is alive. For a short while. The bullet in his chest would have killed him on its own, eventually. But he suffocates beneath the bodies of the men whose last act was a forlorn attempt to protect him. Perhaps he realizes this, as he dies. Perhaps it comforts him.

But he suffocates beneath the bodies of the men whose last act was a forlorn attempt to protect him. Perhaps he realizes this, as he dies. Perhaps it comforts him.

The soldiers withdraw. Later the ditch is filled in by other soldiers who have been tasked with the work. They do a good job of it. They tamp down the dirt. They remove a dropped sock, a pen, some shell casings. They throw branches and leaves and clumps of ragwort on the disturbed ground. These men are lucky. They see only the dead. They see only dead men. This is war. What do you expect.

They saw no boy.

The soldiers who did the shooting take the bags of clothes and burn them on a distant fire where other clothes have been burned before. Then they drive back toward their comrades, their quiet bodies carrying the war in their heads. Their truck is hit by a shell seven kilometers from the place of the murder. All but two die. One survivor shoots himself later that day. The other never regains consciousness. He dies after five weeks, in a hospital bed, in white sheets, his handsome, unmarked face mourned by his sister, the war over.

No one knows about the boy. What boy? The men are dead. The soldiers are dead. His family, dead. There is no one who knows what happened.

No one.

Modern children's stories • Arzamas

You have Javascript disabled. Please change your browser settings.

Children's room ArzamasMaterialsMaterials

Arzamas for classes with schoolchildren! A selection of materials for teachers and parents

Everything you can do in an online lesson or just for fun

Cartoons are festival winners. Part 2

Tales, parables, experiments and absurdity

A guide to Yasnaya Polyana

Leo Tolstoy's favorite bench, greenhouse, stable and other places of the museum-estate of the writer worth seeing with children boys named Petya

Migrants: how to fight for your rights with the help of music

Hip-hop, carnival, talking drums and other non-obvious ways

Old records: fairy tales of the peoples of the world

We listen and analyze the Japanese, Italian, Scandinavian and Russian fairy tales

videos: The ISS commander asks the scientist about space

9000 animation techniquesVR, sunbeams, jelly and spice cartoons

Play the world's percussion instruments

Learn how the gong, marimba and drum work and build your own orchestra

How to put a performance

shadows, reading and other home performance options for children

Soviet rebuses

Well-ups children's puzzles of the 1920-70s

22 cartoons for the smallest

What if you are not six

From "The Wild Dog Dingo" to "Timur and His Team"

What you need to know about the main Soviet books for children and teenagers

A guide to children's poetry of the 20th century

From Agnia Barto to Mikhail Yasnov: children's poems in Russian

10 books by artists

The pages of tracing paper are Milanese fog, and the binding is the border between reality and fantasy

How to choose a modern children's book

“Like Pippi, only about love”: explaining new books through old ones

Verbal games

"Hat", "telegrams", "MPS" and other old and new games

Games from classic books

What the heroes of the works of Nabokov, Lindgren and Milne play

Plasticine animation: Russian school

From "Plasticine Crow" to plasticine "Sausage"

Cartoons - winners of festivals

"Brave Mom", "My Strange Grandfather", "A Very Lonely Rooster" and others

Non-fiction for children

How the heart beats whale, what's inside the rocket and who plays the didgeridoo - 60 books about the world around

Guide to foreign popular music

200 artists, 20 genres and 1000 songs that will help you understand the music of the 1950s-2000s

Cartoons based on poems

Poems by Chukovsky, Kharms, Gippius and Yasnov in Russian animation

Home games

Shadow theater, handicrafts and paper dolls from children's books and magazines of the 19th-20th centuries

Books for the smallest

0 to 5: read, look at, study

Puppet animation: Russian school

Amorous Crow, Imp No. 13, Lyolya and Minka and other old and new cartoons

13, Lyolya and Minka and other old and new cartoons

Smart coloring books

Museums and libraries offer to paint their collections

Reprints and reprints of children's books

Favorite fairy tales, novels and magazines of the last century, which can be bought again

What can be heard in classical music by voices,

4 cuckoos and night forest sounds in great compositions of the 18th–20th centuries

Soviet educational cartoons

Archimedes, dinosaurs, Antarctica and space — popular science cartoons in the USSR

Logic problems

Solve the wise men's dispute, make a bird out of a shirt and count kittens correctly

Modern children's stories

The best short stories about grandmothers, cats, spies and knights

why you can't lie down on the edge. Bonus: 5 lullabies by Naadya

Musical fairy tales

How Tchaikovsky, Rimsky-Korsakov and Prokofiev work with the plots of children's fairy tales

Armenian School of Animation

The most rebellious cartoons of the Soviet Union

Dina Goder’s collection of cartoons

The program director of the Big Cartoon Festival advises what to watch with a child

Cartoons about art

How to tell children about art

40 riddles about everything in the world

What burns without fire and who has a sieve in his nose: riddles from "Chizh", "Hedgehog" and books by Marshak and Chukovsky

Yard games

Traffic light, Shtander, Ring and other games for a large company

Poems that are interesting to learn by heart

What to choose if you were asked to learn a poem about mother, New Year or autumn

Old audio performances for children

"Ole Lukoye", "The Gray Sheika", "Cinderella" and other interesting Soviet recordings

Cartoons with classical music

How animation works with the music of Tchaikovsky, Verdi and Glass

How children's counting rhymes work

"Ene, bene, slave, kvanter, manter, toad": what does it all mean

Short stories are one of the favorite children's genres: it's easy to read and follow the plot. Arzamas chose the best collections of stories about everything in the world: grandmothers, losers, knights, spies, cats and hippos

Arzamas chose the best collections of stories about everything in the world: grandmothers, losers, knights, spies, cats and hippos

Author Lisa Birger

Sylvia Vanden Heide. Fox and Bunny

0+. Translator Irina Trofimova. "Kick scooter". M., 2017

Stories about Fox and Bunny have been published in Holland since 1998: there are more than twenty books in total, five have been translated into Russian. As befits a book from the "I Read It Myself" series, here are very simple texts with short clear sentences, feasible for those who are just getting used to independent reading. Tae Tung Kin's illustrations are built into stories, they are placed several times on a page, and this creates the illusion of movement. And the book tells about the most important thing - about love and friendship. The fox loves the Bunny (and she is the Fox), the Owl loves the Pip-Pip chick, and no matter how difficult it is for them all sometimes with each other, love conquers everything.

Gudrun Mebs. "'Grandma!' Frieder shouts"

0+. Translator Vera Komarova. "Kick scooter". M., 2017

The German Gudrun Mebs became an actress at the age of 17, traveled all over the world with her theater troupe and successfully starred in television series until the age of forty, and in the 80s she began to write fairy tales and philosophical stories for children and became a popular writer. Her first book about Grandma and Frieder came out in 1984, her fourth in 2010, and all four are illustrated by Susanne Rotraut Berner, another great children's author. The main characters are the five-year-old tomboy Frieder and his incredibly patient grandmother. Each story is arranged in the same way: Frieder starts something, and then the grandmother deals with his ideas cheerfully and wisely. He wants to learn how to write - she makes him letters from dough, he wants to go on a picnic in the rain - she has a picnic at the bus stop. And this is again about love - more precisely, about the science of listening to and understanding another.

Bernard Friot. Impatient Stories

6+. Translator Asya Petrova. "Compass Guide". M., 2013

Before becoming a writer and publisher of children's books, the Frenchman Bernard Friaud worked at school for a long time and invented short stories with his students - they form the basis of five collections of Impatient Stories. Brief, absurd and meaningless at first glance, these stories represent the world through the eyes of a child, when everything needs to be turned upside down, rethought, and then, maybe, everything will become much better. Like in the story about the teacher who yelled so much at the children (“Quiet!”) that the students caught her, put her in a jar and calmly redid all her affairs while she, sitting in the jar, opened her mouth with indignation. Or about the boy who tidied up his room so well that he cleaned himself too, and his mother had to scatter everything back to find her son. A good reminder that the world is not always comprehended and measured by parental rules and that sometimes it can be understood only by turning it inside out.

Christine Nöstlinger. "Stories about Franz"

0+. Translator Vera Komarova. "Compass Guide". M., 2017

Franz grows from book to book: in the first collection he is six, in the final, nineteenth, he is already nine. Each story (there are usually three or four of them in a book, ten pages each) is some recognizable situation from a child’s life, whether it’s waiting for gifts for Christmas or a trip to a summer camp, the first meeting with injustice or a sick stomach. As always in such stories with a sequel, it is very important what the hero is like. Franz is a charming, slightly unlucky, not at all ideal child who can both lie and be stupid. And that is why the stories about him are truly funny and instructive. Whatever Franz arranges, in whatever situation he finds himself, he will be supported by a large family and true friends, so here we are talking not only about growing up, but also about the fact that a small child should not be alone.

Jurg Schubiger. "Where does the sea lie?"

6+. Translator Elena Leenson. "Kick scooter". M., 2013

In the funny absurdist stories of the German writer Jürg Schubiger, something strange or nothing happens. The pigs ask the cows how they can get to the sea. The girl got caught in the rain on a bridge in Hamburg and thought: she herself got wet, but her name remained dry. The boy put on his pants and changed his mind because he was tired. The cow is in love with sorrel. The sun and the moon created the world so that there was a place to direct the rays. All these stories have one important feature in common: they invariably provoke mental effort, the need to feel someone else's sadness or love, to look at the world around, because in fact they are still real philosophical parables.

Anastasia Orlova. "I love walking on clouds"

6+. "Egmont". M., 2018

The wonderful children's poetess Anastasia Orlova wrote a series of short stories no longer than her cheerful children's poems. Orlova has a wonderful ability to turn any everyday things into a big event. Mom puts on makeup - an event, clouds are reflected in a puddle - an event, with my mother by the hand I went for a walk, stumbled and fell on the street - also a whole thing. He drank orange juice - there was a swamp in his stomach, there was a rustle in his ears - there the janitor was sweeping the leaves with a broom. Everything around the child turns out to be alive and important, even if only socks.

Orlova has a wonderful ability to turn any everyday things into a big event. Mom puts on makeup - an event, clouds are reflected in a puddle - an event, with my mother by the hand I went for a walk, stumbled and fell on the street - also a whole thing. He drank orange juice - there was a swamp in his stomach, there was a rustle in his ears - there the janitor was sweeping the leaves with a broom. Everything around the child turns out to be alive and important, even if only socks.

Socks

I am sitting in the morning, getting dressed. I take yesterday's socks, but they are dirty. And they smell somehow impolite - yesterday's puddle. And I rather went to wash my socks with strawberry soap.

Marie-Aude Muray. "Dutch without problems"

6+. Translator Marina Kadetova. "Kick scooter". M., 2014

Frenchwoman Marie-Aude Murail wrote her first stories for children at the turn of 1990s, and today in France she is already known as the author of several dozen books. Her teenage novels "Umnik", "Oh, boy!" were published in Russian. and Miss Charity. "Dutch Without Problems" is a collection of three of her early stories. Short but very inspiring. In one, a boy who is sent to learn German for the summer invents his own language and speaks it well; in the second, two girls compare New Year's gifts; in the third, a father stays with his four sons for the weekend and does not cope very well with them. Everything seems to be simple, but each situation is in the treasury of the writer's favorite topic: all of us - both adults and children - need to learn to talk to each other, come up with the "Dutch" language again and again, which will help overcome misunderstanding.

Her teenage novels "Umnik", "Oh, boy!" were published in Russian. and Miss Charity. "Dutch Without Problems" is a collection of three of her early stories. Short but very inspiring. In one, a boy who is sent to learn German for the summer invents his own language and speaks it well; in the second, two girls compare New Year's gifts; in the third, a father stays with his four sons for the weekend and does not cope very well with them. Everything seems to be simple, but each situation is in the treasury of the writer's favorite topic: all of us - both adults and children - need to learn to talk to each other, come up with the "Dutch" language again and again, which will help overcome misunderstanding.

Xenia Dragunskaya. "Angels and Pioneers"

12+. "Time". M., 2018

In the new book by Ksenia Dragunskaya, the confusion of Orthodoxy, patriotism and fear of the Unified State Examination, which the modern school has turned into, is very coolly conveyed. But the main thing is not how funny, with her signature absurdist humor, Dragunskaya plays up all this modern childhood life, but her willingness to offer an alternative - a family where they don’t scold for grades, robot schoolchildren ready to stand up for classmates, a grandfather who turns into watchdog to keep evil teachers out of the doorstep, the school where the writer teaches literature, and the sea captain teaches geography.

But the main thing is not how funny, with her signature absurdist humor, Dragunskaya plays up all this modern childhood life, but her willingness to offer an alternative - a family where they don’t scold for grades, robot schoolchildren ready to stand up for classmates, a grandfather who turns into watchdog to keep evil teachers out of the doorstep, the school where the writer teaches literature, and the sea captain teaches geography.

Maria Bershadskaya. "Big Little Girl"

0+. "Compass Guide". M., 2018

A happy example of a domestic book series for children - 12 stories (each story is a separate lavishly illustrated booklet) about the girl Zhenya, the most ordinary, but so tall that her mother has to stand on a stool to braid her pigtail. The metaphor here is understandable: maybe Zhenya looks quite big, but she is still growing inside, and Bershadskaya's stories are dedicated to this inner growth. 12 books is a year from Zhenya's life. She bakes dad a birthday cake, walks her dog, goes to the village, waits for the New Year: the simplest things always turn into funny adventures. Or thoughts, including about very difficult things: is it possible to think about a holiday when grandfather is sick? Which way to roam if you are completely lost in the forest? And what if someone left a dog on the street?

She bakes dad a birthday cake, walks her dog, goes to the village, waits for the New Year: the simplest things always turn into funny adventures. Or thoughts, including about very difficult things: is it possible to think about a holiday when grandfather is sick? Which way to roam if you are completely lost in the forest? And what if someone left a dog on the street?

Stanislav Vostokov. "Don't feed or tease!"

6+. "Egmont". M., 2017

Stanislav Vostokov is a very talented writer and a true animal lover. He worked at the Moscow and Tashkent zoos, as well as at the Durrell Nature Conservation Center on the island of Jersey, participated in the construction of a rehabilitation center for gibbons in Cambodia ... But the point is not in a romantic biography, but in that special ironic-love intonation with which he writes his stories about animals and people. "Don't feed or tease!" - his most famous book, the stories of a Moscow Zoo attendant: short portraits, sketches of monkeys and capybaras, as well as hippos, which are not.

Where's the hippopotamus?

Visitors often ask:

— And where is your hippopotamus? Why is there no hippopotamus?

And there is no hippopotamus. And you begin to feel very uncomfortable about such an omission, as if you didn’t bring a hippopotamus from Africa.

Visitors shake their heads reproachfully:

- What are you looking at here if there is no hippopotamus? Not for monkeys.

— Why not monkeys? - you answer. — Just for monkeys. After all, some of them are also from Africa. And you probably saw a hippopotamus there!

Bart Muyart. "Brothers"

12+. Translator Irina Mikhailova. "Kick scooter". M., 2017

In Belgium, Bart Muyart is one of the most famous writers, author of more than forty books, winner of numerous awards. And so far only his Brothers, a collection of stories about childhood in Bruges in the late 1960s, have been translated into Russian. There are seven brothers, and they are tirelessly interested in everything in a row. Is it true that whistling in your ear is the echo of dancing on your future grave? How does the pipe help dad think? Is it possible to get sick if you put a bulb in your armpit? And did the king himself really drive in the royal car to give silver spoons to the youngest of the brothers? Time flows slowly in these stories, so that both the characters and the reader can look at the world around and find that everything in it is worth a separate story and full of meaning.

There are seven brothers, and they are tirelessly interested in everything in a row. Is it true that whistling in your ear is the echo of dancing on your future grave? How does the pipe help dad think? Is it possible to get sick if you put a bulb in your armpit? And did the king himself really drive in the royal car to give silver spoons to the youngest of the brothers? Time flows slowly in these stories, so that both the characters and the reader can look at the world around and find that everything in it is worth a separate story and full of meaning.

Victor Lunin. "My Beast"

12+. "Bering". M., 2015

Victor Lunin - poet, translator and writer, holder of the Andersen diploma for translations of children's poetry, author of the story "The Adventures of Butter Liza". “My Animal” are stories about animals that the author met at different moments in his life: an elk in the forest, a cat in the kitchen, a nightingale in the country - unpretentious, like drinking stories or family anecdotes. A simple, but surprisingly pleasant book in its unpretentiousness.

A simple, but surprisingly pleasant book in its unpretentiousness.

Asya Petrova. "Wolves on Parachutes"

12+. "Black River". St. Petersburg, 2017

Writing for teenagers is much more difficult than for middle schoolers, to whom most modern children's stories are addressed. Including because teenagers instantly and acutely feel falsehood. In this collection by Asya Petrova, honesty is almost overwhelming. The experiences of the maturing hero are conveyed with the utmost accuracy: these are stories about how you are afraid of death, how fantasies become larger than life, how difficult it is to trust another, how joy is inseparable from suffering, and it is always easier to believe in tragedy than in happiness. And in each story there is not insipid morality, but a life lesson, something that makes it possible to move on.

Artur Givargizov. "Control dictation and ancient Greek tragedy"

6+. Melik-Pashayev. M., 2017

M., 2017

In fact, it is absolutely impossible to choose the best of Givargizov's books, because all of them are a cure for boredom and sadness. And the point is not only that they are easy to read and very funny (you start laughing from the very first pages). The reader, tormented by school, work, parents and other walking on the string, is here to arrange a real holiday of disobedience. This is liberating laughter, not knowing hierarchies, not striving for education and some kind of "pedagogy", which is already abundant everywhere. It is not surprising that Givargizov is especially good at books about the school: “Notes of an outstanding loser”, “Control dictation and an ancient Greek tragedy”, “Airplane flight according to notes”, “How the director of the school disappeared”. But kings and generals, and pirates, and pensioners, he also turns out to be very charming, not without weaknesses and with passions.

Irina Zartaiskaya. "The Best Age"

6+. "Egmont". M., 2018

"Egmont". M., 2018

Irina Zartaiskaya's stories are ideal for parents who are worried about the pedagogical safety of children's reading: there are no hooligans here, and the losers are somehow unconvincing, too cute. In fact, the author's school life is not so interesting, in her stories the main thing is the family. The most traditional: mom is always in the kitchen, and dad is at work. And in this immutability of all positions one can see the guarantee of the constancy of the world. Now you can play linguistic games in it (what if instead of breakfast there is today or yesterday?), argue with puddles and go to school in tights and T-shirts, because the content is more important than the form.

Mikhail Yesenovsky. "Main Spy Question"

0+. "Egmont". M., 2017

Writer and poet Mikhail Yesenovsky continued the absurdist tradition of Russian literature, using it for almost therapeutic purposes. In the "Main Spy Question", a very brave boy Yura enters into wonderfully funny dialogues with things that he is afraid of: a crocodile under the bed, a skeleton behind the curtain, a grandfather's portrait on the wall. And, of course, with the spy who tortures Yura with the main spy question: "Who do you love more - mom or dad?" Of course, laughter conquers fear, just like in the continuation of Tasty Yura, where the hero has his absurdist conversations with a fox and a jerboa who are going to eat him. And in "Angina Marina" Yura all the time gets sick with something, and even in rhyme:

And, of course, with the spy who tortures Yura with the main spy question: "Who do you love more - mom or dad?" Of course, laughter conquers fear, just like in the continuation of Tasty Yura, where the hero has his absurdist conversations with a fox and a jerboa who are going to eat him. And in "Angina Marina" Yura all the time gets sick with something, and even in rhyme:

"Sickly Yura does not breathe with health: he does not walk during the day, and does not sleep at night, and does not hear with his nose, and does not breathe with his ear, and shoots in the heel, and his neck creaks."

Nikolai Nazarkin. "Emerald fish. Mandarin Islands»

6+. "Egmont". M., 2018

The subtitle of the book is "Ward Stories": these are stories about children for whom the hospital has become everyday life. The book is partly autobiographical: Nazarkin grew up with a diagnosis of hemophilia and was in the hospital much more often than at school. The inhabitants of the chambers dream of fishing, begging each other for sausages, exchanging toys, weaving fish from filters for droppers, and the real trouble here is when brilliant green disappeared from the chamber and the fish from the filters cannot be painted emerald green. Nazarkin does not embellish hospital life, namely that he does not see tragedy in it. More precisely, he is not interested in tragedy: everyday droppers, ECG, rounds of doctors and waiting for parcels from home become only the background for a strong boyish friendship. It’s just that these boys are real knights, and “a knight must look his fate in the eye.”

The inhabitants of the chambers dream of fishing, begging each other for sausages, exchanging toys, weaving fish from filters for droppers, and the real trouble here is when brilliant green disappeared from the chamber and the fish from the filters cannot be painted emerald green. Nazarkin does not embellish hospital life, namely that he does not see tragedy in it. More precisely, he is not interested in tragedy: everyday droppers, ECG, rounds of doctors and waiting for parcels from home become only the background for a strong boyish friendship. It’s just that these boys are real knights, and “a knight must look his fate in the eye.”

Sergey Georgiev. Lilac Hippo Tamer

0+. "Egmont". M., 2017

For many happy years in children's literature, the writer Sergei Georgiev has polished his stories to absolute brevity. Some literally consist of one line: "Remember: a horse in apples is not a culinary recipe." And not only linguistic virtuosity is impressive, but the ability to create a three-dimensional picture with one movement. A few phrases - and you see a fifth grader meowing in a music lesson, or a third grader looking at a chocolate candy under a magnifying glass to make it bigger. These stories can be told like jokes, but their main task is to make the gears of even the laziest fantasy turn rapidly.

A few phrases - and you see a fifth grader meowing in a music lesson, or a third grader looking at a chocolate candy under a magnifying glass to make it bigger. These stories can be told like jokes, but their main task is to make the gears of even the laziest fantasy turn rapidly.

Oleg Kurguzov. "Our cat is an alien"

0+. "Egmont". M., 2017

For his first book of short stories, The Sun on the Ceiling. Stories of a Little Boy”, published in 1997, Oleg Kurguzov received the Janusz Korczak International Prize. From the late 1980s, he was the editor of children's publications: from the magazine "Tram" to the newspaper "Little Cart" invented by him. In 2003, his last book, Our Cat Is an Alien, was published, and in 2004 Kurguzov passed away. And what a pity that he did not live to see the current flourishing of children's literature! "Our Cat Is an Alien" is a book about a family in which everything is unusual: a father flies and crawls with his son, a goat turns into a dog, and a horse comes to visit for cleaning. And also a book about love, because this strange family, together with the cat, is an example of complete harmony.

And also a book about love, because this strange family, together with the cat, is an example of complete harmony.

Sergei Makhotin. Grunt Virus

6+. "Detgiz". M., 2014

Sergei Makhotin - the author of novels, poems, stories, historical novels - in 2011 became the winner of the Korney Chukovsky Prize "for outstanding creative achievements in Russian children's literature." The Grunt Virus itself received the Scarlet Sails Award and the Andersen International Diploma, and yet finding this book is not at all easy - but definitely worth it. "Grumbling Virus" is the stories of the inhabitants of one house, inspired, according to the author, by his childhood in St. Petersburg. The stories in the collection are both fabulous - for example, about a hairdresser who bewitched a girl's pigtails, so that whoever pulls them immediately decreases - and piercingly realistic. For example, about two classmates who were sent to visit a third one, but it turned out that he did not get sick, but went to Boston, and left a grandmother, a skinny cat on a branch outside the window, and a dreary feeling of broken conversations. Makhotin is better than many at showing that life can be both surprisingly easy and strangely sad at the same time.

Makhotin is better than many at showing that life can be both surprisingly easy and strangely sad at the same time.

Alexander Blinov. "The House That Went"

12+. "Kick scooter". M., 2018

Alexander Blinov is a graphic artist, architect and aircraft designer who started writing stories for children just a few years ago. Blinov already has six wonderful books, and in all of them - be it fairy tales, like in The Moon Who Loved Eclairs, or autobiographical stories, like in Pure Lies - some incredible liberty is felt. There are no borders, no tightness and wear, full of tramcars, inside of which a seven-story house can fit, suddenly thinking of going on a hiking trip. Paris - Berlin - Vienna - Rome and everywhere else. But in the end, the house still returns, having escaped from Hollywood to the Novoye Khodilovo microdistrict. In these stories, Blinov perfectly managed to convey the feeling of a man of the world, equally his own in Italy and Israel, and equally frivolously alien.

Children's room

Special project

Children's room Arzamas

Tags

Children

What to read

Yuri Berezkin: “As an archaeologist I was always lucky”

Skeletons of babies, golden horns, the tomb of priests. How is the life of an archaeologist and why are some people lucky and others not? In the new issue of the "Scientific Council" - a specialist in prehistory and archaeologist Yuri Berezkin. He also talks about how he collected a giant database of mythology and folklore and why the myths of completely different peoples are similar

© Arzamas 2022. All rights reserved

left before the subscription price increase.

Buy now

.

top hair trends this spring - FW-Daily

The time has come when hats are no longer essential, and frost and wind do not harm our hair. It's time to think about how to stylishly refresh your hair and what haircut to choose this spring.

It's time to think about how to stylishly refresh your hair and what haircut to choose this spring.

In the new year, we say goodbye to fashion casualness and natural coloring in one color: these trends are replaced by smooth texture, neatly combed back hair, short bangs and unusual pastel colors. We talk about the main trends in hairstyles for the spring-summer 2019 seasonyears and show vivid examples from the catwalks.

Side Parting

The side parting trend has been on the runway for a few seasons now, but it's still going strong this spring. You can make trendy styling very quickly and, most importantly, without going to the hairdresser. And no casualties! Combing your hair to one side, you can collect it in a low bun, which is also one of the main trends of the season, or decorate loose hair with stylish accessories.

Wet hair effect

Wet hair styling promises to be one of the main trends of this spring. The most popular hairstyle options are strands slightly raised at the roots and pulled back, complemented by special products for the “just out of the shower” effect, or hair parted with a side part and neatly smoothed on the sides. This hairstyle will look perfect with light spring trench coats, massive accessories and sunglasses.

This hairstyle will look perfect with light spring trench coats, massive accessories and sunglasses.

Casual waves

It's time for light dresses, floral prints and airy fabrics. Such truly spring looks are perfectly complemented by styling with light waves and slightly tousled hair in the style of Parisian chic. This hairstyle is made very simply and gives any image more femininity and elegance.

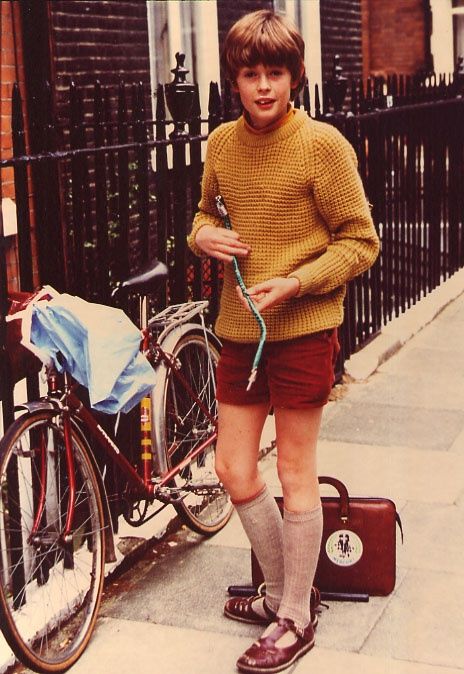

Ultra-short haircuts

Ultra-short boy-style haircuts and a short bob to the ears have already become one of the main hair trends this spring. Many options for such hairstyles were presented at the shows of the spring-summer 2019 season., and now fashion bloggers and many fashionista began to show off in the photo with a minimum hair length and careless disheveled styling. A bold decision, but it will definitely attract the attention of others, especially in tandem with another spring trend - pastel hair coloring.