Social needs in children

A Practical Guide to Developing Resilient Learners

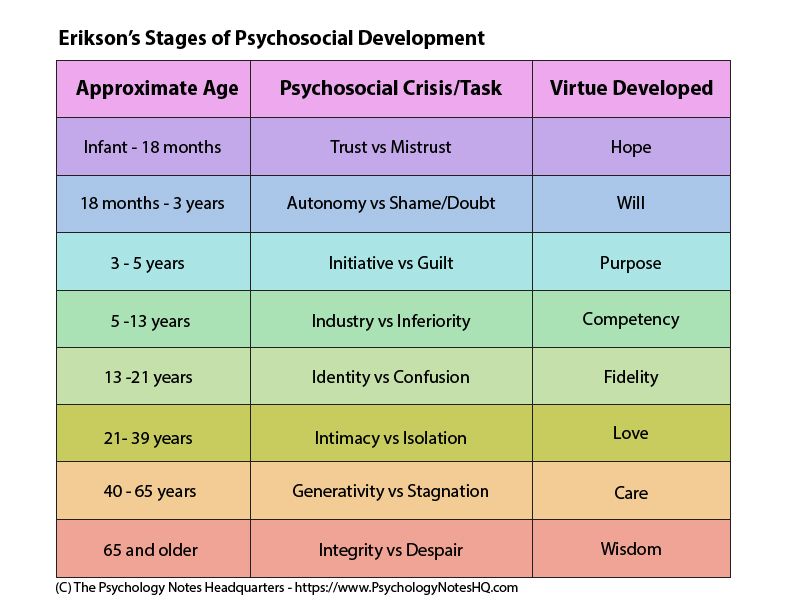

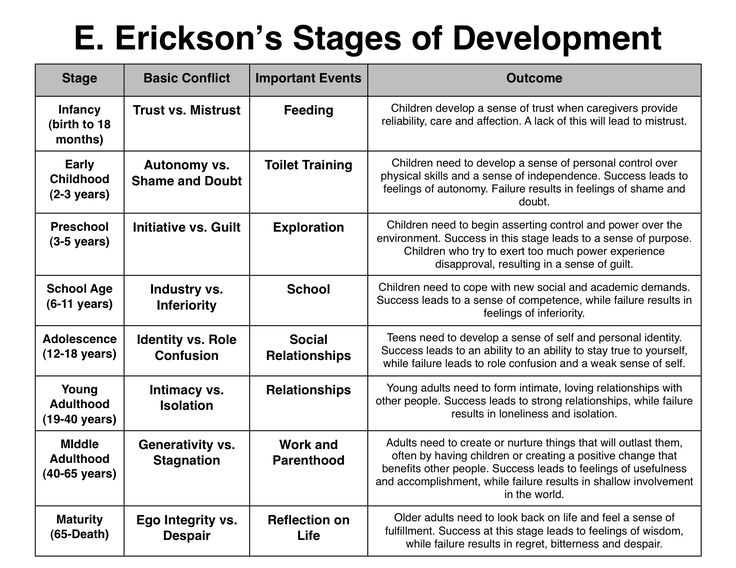

As introduced in detail in the previous chapter on attachment, the first formation of relationships is critical to future experiences and the social-emotional wellbeing of the child. The development of safe and secure relationships within which children learn how to manage emotions and self-regulate form the blueprint for successful future regulation of emotions and social competence.

Two kids in school uniform by Cyberscooty used under CC0.There are quite a few evidenced-based programs that promote social-emotional learning for young children and at the same time reduce disruptive behaviour.

Take a look at the Teaching Pyramid (https://www.eciavic.org.au/pdevents/the-teaching-pyramid) The teaching pyramid originally developed by Fox, Dunlap, Hemmeter, Joseph and Strain (2003) is a positive behaviour support framework that outlines practices to prevent challenging behaviour and promote social-emotional competence in children.

The foundation is relationships. Quality relationships with children, families, colleagues and other practitioners, are the base from which evidence-based strategies can be implemented to cater for social emotional needs of children.

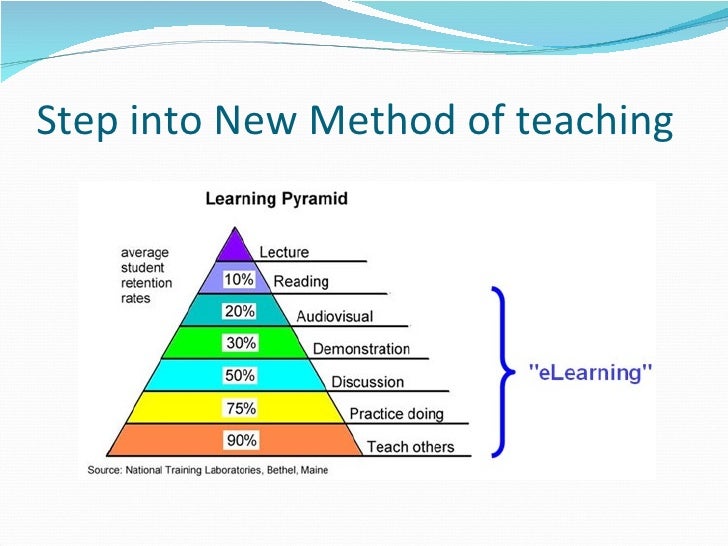

The teaching pyramid is an example of a multi-tiered framework particularly designed for supporting social emotional learning in early childhood contexts. Multi-tiered frameworks consist of the following three tiers of intervention and support: Universal or tier one, targeted or tier two and intensive or tier three. The tiers of the teaching pyramid reflect the same focus areas: promotion (universal), prevention (targeted) and intervention (intensive). The goal of a multi-tiered framework is to endeavour to provide support to all children across social, emotional, behavioural and academic domains of development, to promoting positive behaviour and reduce the occurrence of disruptive behaviour (Bayat, 2015; Hemmeter et al., 2012). Promotion (universal tier one) is targeted at all children, prevention (targeted tier two) at smaller groups of children and intervention (intensive tier three) at individual children with more intensive needs. For most children, the universal level will probably be enough, however for children with trauma, the secondary prevention and tertiary intervention tiers are more likely to better address their needs. Let us have a closer look at the key features of each tier of the teaching pyramid.

For most children, the universal level will probably be enough, however for children with trauma, the secondary prevention and tertiary intervention tiers are more likely to better address their needs. Let us have a closer look at the key features of each tier of the teaching pyramid.

Promotion (Universal tier 1): Building relationships between teachers and children, teachers and caregivers and children and children. It is also important to include here those adults who are significant in the child’s life beyond the school and home such as practitioners from government and community agencies, if applicable.

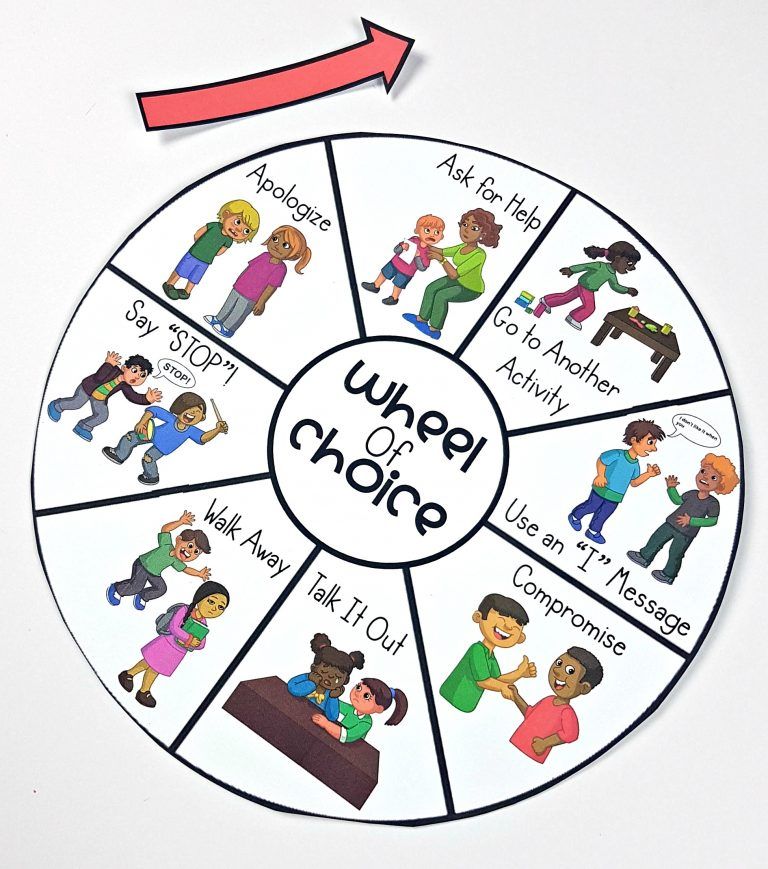

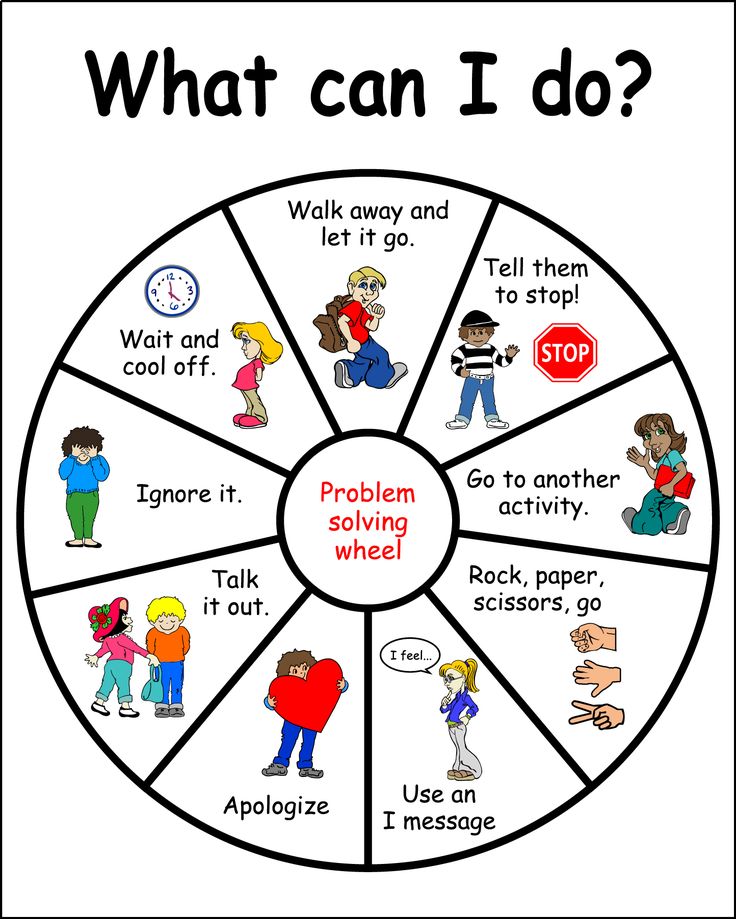

Prevention (targeted tier 2): Focused teaching of social and emotional skills needed to solve problems, demonstrate feelings and develop friendships. The ‘teachable moments’ throughout the day are the perfect opportunities for this teaching.

Intervention (intensive tier 3)

: For those individual children needing targeted support. Functional behavioural assessment to ascertain the function of behaviour and develop an intervention plan, is the focus of this tier. Teaching new appropriate behaviours to replace the inappropriate behaviours – new behaviours that serve the same function but are acceptable in the environment. The evidence-based practices of the teaching pyramid are equally important to consider for the primary aged child and the adolescent.

Functional behavioural assessment to ascertain the function of behaviour and develop an intervention plan, is the focus of this tier. Teaching new appropriate behaviours to replace the inappropriate behaviours – new behaviours that serve the same function but are acceptable in the environment. The evidence-based practices of the teaching pyramid are equally important to consider for the primary aged child and the adolescent.

Bailey, Denham, Curby and Bassett (2016) found that emotional and organisational supports were significant factors in guiding social-emotional learning and self-regulation in pre-schoolers (four to five-year-olds). The authors found that a classroom that was emotionally supportive reduced behaviour problems and increased social competence. Plenty of opportunity was given for children to self-regulate within an environment of safety where expression and learning were valued, and close relationships were formed. These classrooms were well-organised promoting high levels of learning engagement with clear expectations taught and understood (this would equate to the universal promotion area of the teaching pyramid).

Meeting the child where they are emotionally and socially is a key underpinning strategy for developing social-emotional competence in children. Whatever the strategy, research has shown that it is important for children to learn, practise, view and talk about the new skill with examples to illustrate what it looks like, sounds like and feels like (Corso, 2007). For those children who have experienced complex trauma the following strategies have been shown to be very helpful in assisting them to regulate emotions:

- Name your emotions. Talk aloud so there is connection between feeling and words.

- Make clear links between the emotion and the event.

- Use a feeling die (use at carpet time for children to tell about the time they felt…).

- Dance to different kinds of music and talk about how it feels.

- Explicitly teach children how to read the nonverbal cues of others. Why do people frown, grimace, look upset?

- Read picture books that discuss emotions.

An article by Harper (2016) discusses how picture books can be useful in developing social-emotional competence.

An article by Harper (2016) discusses how picture books can be useful in developing social-emotional competence.

When you live a life of mistrust and hurt, your internal workings tell you that relationships with others are not a good idea because they are unsafe and to protect yourself it is easier to just avoid them all together. How does this child know how to form and ‘be in’ friendships with others? They don’t. They need to be taught. Sorrels (2015) details the following social skills:

- Empathy – Children from chaotic backgrounds often arrive at school ‘not ready to learn’. Providing time to check in nurtures empathy, encourages regulation and shows care and concern.

- Turn-taking – my turn, your turn (This is not sharing. Sharing is different. We share collage materials and food; we take turns going through the tunnel and down the slippery dip). Children with trauma have lost so much, they do not want to give-up anything so find turn-taking difficult.

Use timers, visuals and solve problems aloud.

Use timers, visuals and solve problems aloud. - Sharing – children with trauma ‘accumulate stuff’ whenever they can because they fear the opportunity may never arise again. They are fearful of not having. They are not greedy. Plan activities where they can practice sharing and ensure they know what it looks like and sounds like to share.

- Joining in – join the game with the child and stay and play for a moment by guiding them in and helping them engage.

- Conflict resolution – talk through situations of conflict. The child with trauma is often overwhelmed by these situations. Remember Elliott from the true story at the beginning of the chapter? He used to climb into a cupboard and slide the door almost shut (the track was fixed so that the door could not be fully closed). Many children with trauma will hide in times of conflict.

Please note that the above material from Reaching and Teaching Children Exposed to Trauma by Barbara Sorrels, EdD, ISBN

9780876593509, is used with permission from Gryphon House, Inc. , P. O. Box 10, Lewisville, NC 27023 (800) 638-

, P. O. Box 10, Lewisville, NC 27023 (800) 638-

0928 www.gryphonhouse.com. No further reproduction of this content is permitted without prior permission from the copyright holder.

Read the following resources from the Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning:

- Strategies for teachers

- “What Works Briefs” (practical strategies and handouts)

Watch this video on social and emotional competence. A transcript and Closed Captions are also available within the video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KJjUpmJ8SqE

Bailey, C. S., Denham, S. A., Curby, T. W., & Bassett, H. H. (2016). Emotional and organizational supports for preschoolers’ emotion regulation: Relations with school adjustment. Emotion, 16(2), 263-279.

Bayat, M. (2015). Addressing challenging behaviors and mental health issues in early childhood. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Corso, R. M. (2007). Practices for enhancing children’s social-emotional development and preventing challenging behavior. Gifted Child Today, 30(3), 51-56.

Gifted Child Today, 30(3), 51-56.

Fox, L., Hemmeter, M., Snyder, P., Binder, D. P., & Clarke, S. (2011). Coaching early childhood special educators to implement a comprehensive model for promoting young children’s social competence. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 31(3), 178-192. doi: 10.1177/0271121411404440.

Harper, L. J. (2016). Using picture books to promote social-emotional literacy. Young Children, 17(3), 80-86

Hemmeter, M. L., Ostrosky, M. M., & Corso, R. M. (2012). Preventing and addressing challenging behavior: Common questions and practical strategies. Young Exceptional Children, 15, 32-46.

Sorrels, B. (2015). Reaching and teaching children exposed to trauma. Lewisville, NC: Gryphon House.

Social Development in Children | SCAN Families

Ask any parent about their child’s development, and they’ll often talk about speech and language development, gross motor skills or even physical growth. But a child’s social development—her ability to interact with other children and adults—is a critical piece of the development puzzle.

But a child’s social development—her ability to interact with other children and adults—is a critical piece of the development puzzle.

Social development refers to the process by which a child learns to interact with others around them. As they develop and perceive their own individuality within their community, they also gain skills to communicate with other people and process their actions. Social development most often refers to how a child develops friendships and other relationships, as well how a child handles conflict with peers.

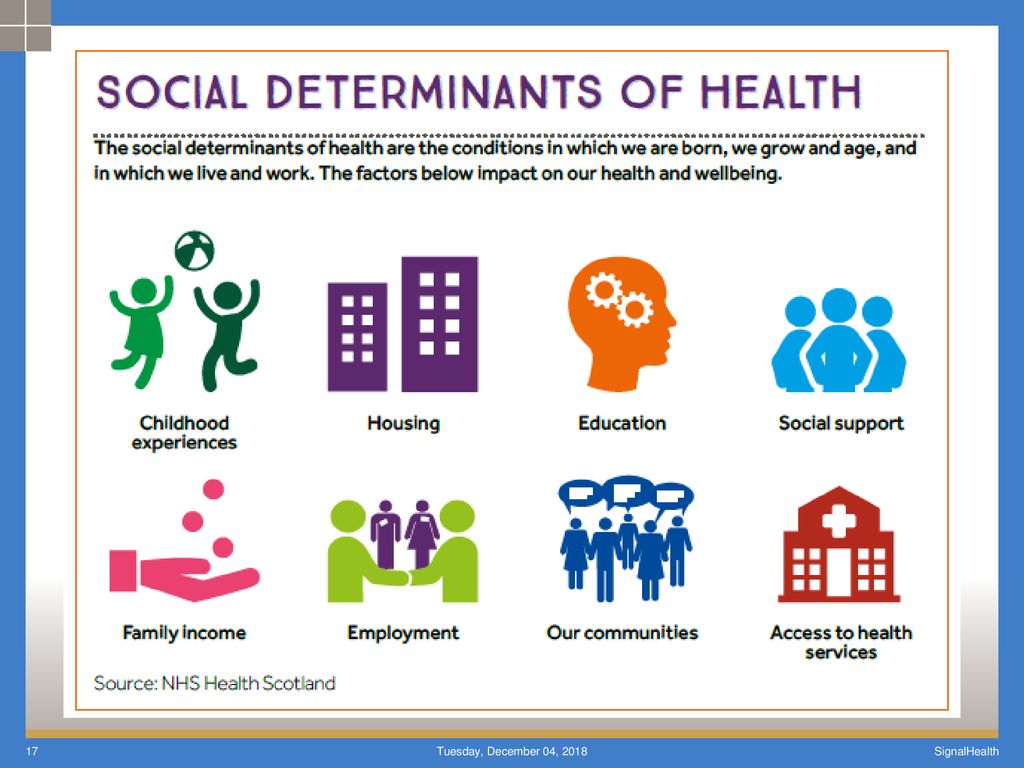

Why is social development so important?Social development can actually impact many of the other forms of development a child experiences. A child’s ability to interact in a healthy way with the people around her can impact everything from learning new words as a toddler, to being able to resist peer pressure as a high school student, to successfully navigating the challenges of adulthood. Healthy social development can help your child:

Healthy social development can help your child:

- Develop language skills. An ability to interact with other children allows for more opportunities to practice and learn speech and language skills. This is a positive cycle, because as communication skills improve, a child is better able to relate to and react to the people around him.

- Build self esteem. Other children provide a child with some of her most exciting and fun experiences. When a young child is unable to make friends it can be frustrating or even painful. A healthy circle of friends reinforces a child’s comfort level with her own individuality.

- Strengthen learning skills. In addition to the impact social development can have on general communication skills, many researchers believe that having healthy relationships with peers (from preschool on up) allows for adjustment to different school settings and challenges. Studies show that children who have a hard time getting along with classmates as early as preschool are more likely to experience later academic difficulties.

- Resolve conflicts. Stronger self esteem and better language skills can ultimately lead to a better ability to resolve differences with peers.

- Establish positive attitude. A positive attitude ultimately leads to better relationships with others and higher levels of self confidence.

Studies show that everyday experiences with parents are fundamental to a child’s developing social skill-set. Parents provide a child with their very first opportunities to develop a relationship, communicate and interact. As a parent, you also model for your child every day how to interact with the people around you.

Because social development is not talked about as much as some other developmental measures, it can be hard for parents to understand the process AND to evaluate how their child is developing in this area. There are some basic developmental milestones at every age, as well as some helpful tips a parent can use to support their child.

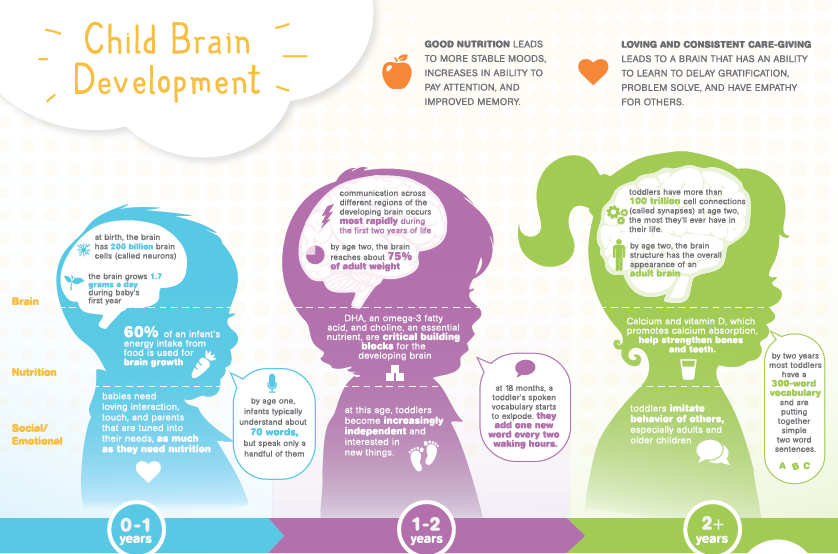

During the first 2 years of life, huge amounts of development are rapidly occurring. You can expect your child to:

– Smile and react positively to you and other caregivers

– Develop stranger anxiety—though it can be frustrating, this is a normal step in development

– Develop an attachment to a comfort object such as a blanket or animal

– Begin to show anxiety around other children

– Imitate adults and children—just as a child develops in other ways, many social skills are learned simply through copying what a parent or sibling does

– Already be affected by emotions of parents and others around them

As a parent, you can:

– Respond to your baby’s needs promptly—your child is learning how to trust someone

– Make eye contact with your baby—get down to their level and connect visually when you interact with them

– Babble and talk to your baby, always pausing to allow them to respond

– Play copycat with words and actions

– Play “peekaboo”—this teaches your child that even if you “disappear” you will come back, and sets the stage for less stranger anxiety in the future

– Involve your baby in daily activities such as running errands or visiting friends—this shows them how you interact with others in a respectful, positive way

– Begin to arrange playdates so that your child can interact with peers

By this age, the stage has been set in the earliest years (mostly by parental and other family interactions) for a child to branch out. As preschool begins your child can:

As preschool begins your child can:

– Explore independently

– Express affection openly, though not always accurately—there can still be much frustration for your child as language development is still happening

– Still show some stranger anxiety

– Perfect the temper tantrum—it can be stressful, but tantrums are a normal part of child development

– Learn how to soothe themselves

– Be more aware of others’ emotions

– Cooperate with other children

– Express fear or anxiety before an upcoming event (such as a doctor visit)

As a parent, you can:

– Demonstrate your own love through words and physical affection—which is a great way to begin teaching a child how to express other emotions as well

– Help your child express their emotions by talking through what they are feeling

– Play with your child in a “peer-like” way to encourage cooperative play—this is helpful when they are in a group environment and have to share toys and cooperate

– Continue to provide play dates and opportunities to interact with other children

– Provide examples of your trust in others, such as your own friendships or other relationships

By 5 and older, a child’s social development begins to reach new levels. This is a point in time when most children will spend more hours in a day with other children than with their parents. It is normal for them to:

This is a point in time when most children will spend more hours in a day with other children than with their parents. It is normal for them to:

– Thrive on friendships

– Want to please friends, as well as be more like their friends

– Begin to recognize power in relationships, as well as the larger community

– Recognize and fear bullies or display bully-like behavior themselves

– As early as 10, children may begin to reject parents’ opinion of friends and certain behaviors—this is a normal step, but can be especially frustrating for parents

As a parent, you can:

– Talk with your child about social relationships and values by asking them about school and friends every day

– Allow children the opportunity to discuss social conflicts and problem-solve their reactions/actions

– Discuss the subject of bullying and harassment, both in person and on the Internet

– Allow older children to work out everyday problems on their own

– Keep the lines of communication open—as a parent, you want to make yourself available to listen and support your child in non-judgmental ways

Your child’s social development is a complex issue that is constantly changing. But the good news is that parents can have a big impact on how it progresses. By modeling healthy relationships and staying connected with your child, you can help them relate to the people around them in positive, beneficial ways. By encouraging them to engage with other children and adults, you’re setting them up to enjoy the benefits of social health—from good self esteem to strong communication skills to the ability to trust and connect with those around them.

But the good news is that parents can have a big impact on how it progresses. By modeling healthy relationships and staying connected with your child, you can help them relate to the people around them in positive, beneficial ways. By encouraging them to engage with other children and adults, you’re setting them up to enjoy the benefits of social health—from good self esteem to strong communication skills to the ability to trust and connect with those around them.

Social needs of a child at preschool age

Features of the social situation of development at preschool age

Note 1

At preschool age most of the significant changes in a child's personality are based on his active entry into the world of social relations. The child moves from the world of things to the world of people, the child's social ties with the world expand and it is filled with communication with close adults. In addition, the child gradually expands the range of interaction with society through contacts with peers and strangers.

The child has a need to establish and expand personal relationships with other people, which directs him to a complete search and knowledge of the social sphere.

Communication from extra-situational-cognitive turns into extra-situational-personal, which allows the child to build social connections and relationships. One of the main areas of social needs at this age is the need for a child to communicate with surrounding adults. The leading motive is the motive of personal understanding and empathy on the part of the senior communication partner.

Social needs dominating in preschool age

- Need for self-identification;

- need for attention and kindness;

- need for affection and recognition;

- the need to communicate with other people;

- the need to communicate with peers;

- Need for respect from peers.

Realizing the need for self-identification, the preschooler strives to be like a significant adult (parents, relatives, adult friends) the existing image for the child is positively colored, the attitude of the preschooler is emotional. The child identifies with the parent of the same gender and is aware of being a boy or a girl.

The child identifies with the parent of the same gender and is aware of being a boy or a girl.

The preschooler tries to “include” his social behavior in the surrounding microenvironment, in accordance with its requirements and norms. The child can pay attention to how he moves, how he said hello, etc., relying on the external side of social interaction.

The need to communicate with other people encourages the child to learn the norms of behavior accepted in society, establish relationships with partners in interaction and resolve conflicts in a way acceptable in society. At this age, the assimilation of moral and moral norms and socially established actions takes place. The child is interested in mastering these, new for him, forms of behavior.

Another group of social motives for a preschool child is associated with the need to communicate with peers. If in relations with adults children act as an object of regulation, then within the children's microsociety each child becomes both an object and a subject of regulation. This has an impact on the formation of ethical standards and self-regulation.

This has an impact on the formation of ethical standards and self-regulation.

The need for communication with peers arises in a child already in the third year of life. If at an early age contacts with peers were situational, of little content, and sometimes even led to conflict, at preschool age the child learns the rules of joint play and interaction.

Gradually, communication with peers becomes non-situational, children can figuratively talk about the events that happened to them, about the books and films they read, show their skills and knowledge, gleaned from the conversations of adults, etc.

The most important social need is also the desire to win the respect of a peer. For a child of senior preschool age, his reputation and authority in the social group to which he belongs is very important.

Note 2

Thus, among the social needs, one of the most important is the need for communication. It always has content and can be a joint activity, conversation, problem solving, etc.

The need to know the world around through communication with other people makes it possible to know oneself through another and to know another person.

Essential social needs | Psylist.net

The problem of human needs is complex and ambiguous. We do not undertake to cover it completely, because it is beyond the scope of this book. It seems most expedient to dwell only on the most important social needs of early adolescence: the need for communication and isolation, for achievement and search.

The need for communication has a specifically human character and is formed in the child in the process of relationships that he develops with other people.

With age, the need for communication deepens and becomes more and more significant in the lives of children, although there is no reason to assert that its development is only on the ascending line and that temporary stops and even some regression are not characteristic of it. Obviously, one of the peaks in the development of a person's need for communication is early youth.

What explains the high level of development of the need for communication in early adolescence? There are several reasons. The most obvious is the constant physical and mental development of the student and, in connection with this, the expansion of his interests, the growth of interest in the world. An important circumstance is the need for activity: it largely finds its satisfaction in communication. In youth, the need especially increases, on the one hand, for new experience, and on the other, for recognition, protection in an intimate reaction. This determines the growth of the need to communicate with people, the need to be accepted by them and feel confident in their recognition.

This is necessary to solve those problems that are characteristic of adolescence and that can be solved only in communication with others. Numerous studies undeniably indicate that an effective solution to the problems of self-consciousness, self-determination, self-affirmation is impossible without communication with other people, without their help.

The problems are so important and so intimate that in order to solve them, to "outlive" youth, it is necessary to find a person who would understand its problems. With age (from 14 years to 17 years), the need for understanding increases markedly, and in girls it is more pronounced than in boys. Understanding does not necessarily imply rationality. Mainly, understanding should have the character of a purely emotional sympathy, empathy. Naturally, such a person first of all thinks of a peer who is overwhelmed by the same problems and the same experiences.

Boys and girls are in constant expectation of communication. This state of mind makes them actively seek communication with others. Each new person attracts attention as a possible partner for communication. Communication in youth is distinguished by special trust, intensity, confession, which leaves an imprint of intimacy and passion on the relationship that connects high school students with people close to them. Because of this, failures in communication are so acutely experienced in early youth.

The words of Pascal can be most attributed to high school students: “Whatever a person on earth possesses, excellent health and any blessings of life, he is still dissatisfied if he does not enjoy respect among people. He respects the mind of man so much that, having all possible advantages, he feels dissatisfied if he does not occupy an advantageous place in the minds of people. This is the place that attracts him most in the world, and nothing can divert him from this goal.

Speaking about the need for isolation, one must keep in mind that the development of personality can be regarded as a two-pronged process. On the one hand, this is likening oneself in something to other people in the process of communication, and on the other hand, distinguishing oneself from others as a result of the process of isolation. Moreover, communication and isolation proceed in close unity with each other.

The need for isolation, which is clearly manifested in early adolescence, finds its concrete expression both in communication (in isolation within more or less large communities) and in solitude. Separation in communication is of primary importance. Communicating with people, young men and women feel the need to find their position in theirs. environment, one's self. But understanding this need and ways to implement it is obviously possible if there is a need for solitude.

Separation in communication is of primary importance. Communicating with people, young men and women feel the need to find their position in theirs. environment, one's self. But understanding this need and ways to implement it is obviously possible if there is a need for solitude.

Speaking about the isolation of personality in early youth, one must keep in mind several of its levels: the first is the isolation of high school students within their entire age group; the second - as part of fairly broad communities - groups of peers; the third is isolation within peer groups, friendly and friendly, and, finally, the fourth is isolation of the individual within collectives and groups ...

The need for solitude is social in its content and normally has nothing to do with the manifestation of individualism…

The activity of high school students in solitude can be both objective (reading, designing, etc.) and communicative. The latter arises when a boy or girl has no desire to communicate with possible real partners, but there is a desire to communicate in solitude with some imaginary ideal partner or one's self. Let's dwell on some of them.

Let's dwell on some of them.

In early youth there is an intensive knowledge of the wealth accumulated by world culture. A certain part of this knowledge (and a considerable part) can be effective only in solitude: both the perception of knowledge, and their comprehension, and the construction of certain logical schemes based on the perception and comprehension of knowledge.

Further, one can know oneself only in communication with others, but to understand oneself, comprehend oneself - in solitude. In this regard, one cannot fail to recall that some tribes included prolonged loneliness in the initiation rite (transition to adulthood). In youth, it is a special pleasure to immerse yourself in yourself, to explore your thoughts, feelings, actions. Sixteen-year-old M.Yu. Lermontov wrote to M.A. Lopukhina: “Can I name everyone I visit? I am the person with whom I visit with the greatest pleasure. Apparently, this is not accidental: in order to find a way to peace, you need to find a way to yourself. He cannot be an interlocutor who avoids himself. In this case, he does not know how to think about the world in general and about his relations with the world in particular, he cannot soberly assess himself and life situations.

He cannot be an interlocutor who avoids himself. In this case, he does not know how to think about the world in general and about his relations with the world in particular, he cannot soberly assess himself and life situations.

The perception of a young man by those around him, his perception of himself, as well as the perception of the phenomena of reality by him and his communication partners can differ significantly from each other. This is due to the fact that the vision of the same phenomenon by different people depends on their past experience. In solitude, a high school student has the opportunity to comprehend these differences, to realize the difference between his own and other norms of perception, assessments and behavior. As a result, he can determine his own line of behavior, which will help him to better contact with others. On the other hand, in solitude, a boy or girl has the opportunity to realize those objective and subjective changes that occur in them, and develop a new vision of themselves, a new self-esteem, etc.

In early youth, the creative potential of the individual is unusually diverse. Solitude makes it possible to realize many of them: musical, artistic, literary, partly technical ... Solitude in early youth is fundamentally different from the solitude of adults. Adults, remaining alone with themselves, seem to shed the burden of the roles that they play in life, and, at least it seems to them, become themselves. Young men, on the contrary, are only in solitude and can play those numerous roles that are inaccessible to them in real life, present themselves in those images that appeal to them most. They do this in the so-called daydreams and dreams, in which many of the functions of solitude are realized and which are “like a carnival experienced alone, with a keen consciousness of this unity”.

The difference between dream games and daydreams can be conditionally defined as follows.

In dream games, young men and women play roles and situations created by them in their imagination, without a real prototype, impossible in life. Dream games are an attempt to compensate for the irreplaceable deficit of real life. This includes fantasies in which the boys and girls themselves act, and real people from their environment, as well as invented by them, but quite realistic characters. These imaginary situations have never happened, and their real characters are not even aware of the adventures in which they participate at the behest of the authors. Nevertheless, such fantasies are sometimes presented by young men and women to their peers, most often to raise their own prestige in their eyes.

Dream games are an attempt to compensate for the irreplaceable deficit of real life. This includes fantasies in which the boys and girls themselves act, and real people from their environment, as well as invented by them, but quite realistic characters. These imaginary situations have never happened, and their real characters are not even aware of the adventures in which they participate at the behest of the authors. Nevertheless, such fantasies are sometimes presented by young men and women to their peers, most often to raise their own prestige in their eyes.

In a dream, young men and women play roles and situations that exist and are possible in life, but are inaccessible to them at all or at this time for some objective or subjective reasons. A dream is a compensation for a really replenishable deficit that cannot be made up now, in the actual reality for a young man and a girl...

A dream in solitude is a completely different opportunity: a life organized according to other laws than ordinary life. Life, seen in a dream, removes (from the word "strange") ordinary life, makes us understand and evaluate it in a new way (in the light of a different opportunity seen). And a young man in a dream becomes a different person, reveals new possibilities in himself (I am the best, and the worst), is tested and tested by a dream.

Life, seen in a dream, removes (from the word "strange") ordinary life, makes us understand and evaluate it in a new way (in the light of a different opportunity seen). And a young man in a dream becomes a different person, reveals new possibilities in himself (I am the best, and the worst), is tested and tested by a dream.

In early youth, the need for solitude is the norm. The absence of this need indicates that the personality does not develop intensively enough for its age. On the other hand, a sharp predominance of the need for solitude is sometimes an alarming sign.

The need for solitude can be considered as a reflection of a certain stage of personality development, and the realization of this need as one of the conditions for personality development at this age.

The striving for isolation in early youth (both in communion and in solitude) is by no means an opposition to sociality and collectivism. The social nature of the interests and goals of the individual does not in the least exclude individual ways of achieving and satisfying them. Moreover, the individualization of ways to implement the socially significant aspirations of the individual is becoming an increasingly necessary condition for genuine collectivism. The modern collective is strong, first of all, by the extent to which the individualities of the people included in it, performing common collective tasks, are revealed and clearly revealed, to what extent their individual interests are filled with social content.

Moreover, the individualization of ways to implement the socially significant aspirations of the individual is becoming an increasingly necessary condition for genuine collectivism. The modern collective is strong, first of all, by the extent to which the individualities of the people included in it, performing common collective tasks, are revealed and clearly revealed, to what extent their individual interests are filled with social content.

Many classifications of needs highlight the need for achievement. The need for achievement is understood by a number of researchers as an inherent desire for success in activities, in competition with a focus on a certain standard of high quality performance.

This need is formed from childhood. In early youth, in a large part of the children, it is quite developed. It is implemented in different ways: for some in the field of cognitive activity, for others in various types of hobbies, for others in sports, etc. There is reason to believe that those high school students who have a particularly strong need for achievement have a weaker need for communication. At the same time, it is in youth that the need for achievement can be directed towards achieving success in one or another area of communication and, as it were, strengthens the need for communication in a high school student.

At the same time, it is in youth that the need for achievement can be directed towards achieving success in one or another area of communication and, as it were, strengthens the need for communication in a high school student.

The need for achievement is an important characteristic of a person, because the solution to the problems of self-determination and self-assertion largely depends on it….

Subsection: Reader on developmental psychology

Similar materials in the Reader section:

- Personality and its formation

- W. James Psychology. M., 1991.

- Stendhal. About love

- Problems of communication and interaction (Myers D. Social psychology / Translated from English. St. Petersburg: Peter, 1997, S. 315-339.)

- Primary and secondary teaching

- Non-situational-personal form of communication between children and adults (6-7 years old)

- S.L. Rubinstein The problem of abilities and questions of psychological theory

- Social psychology as history (Gergen K.