Social skill training for child

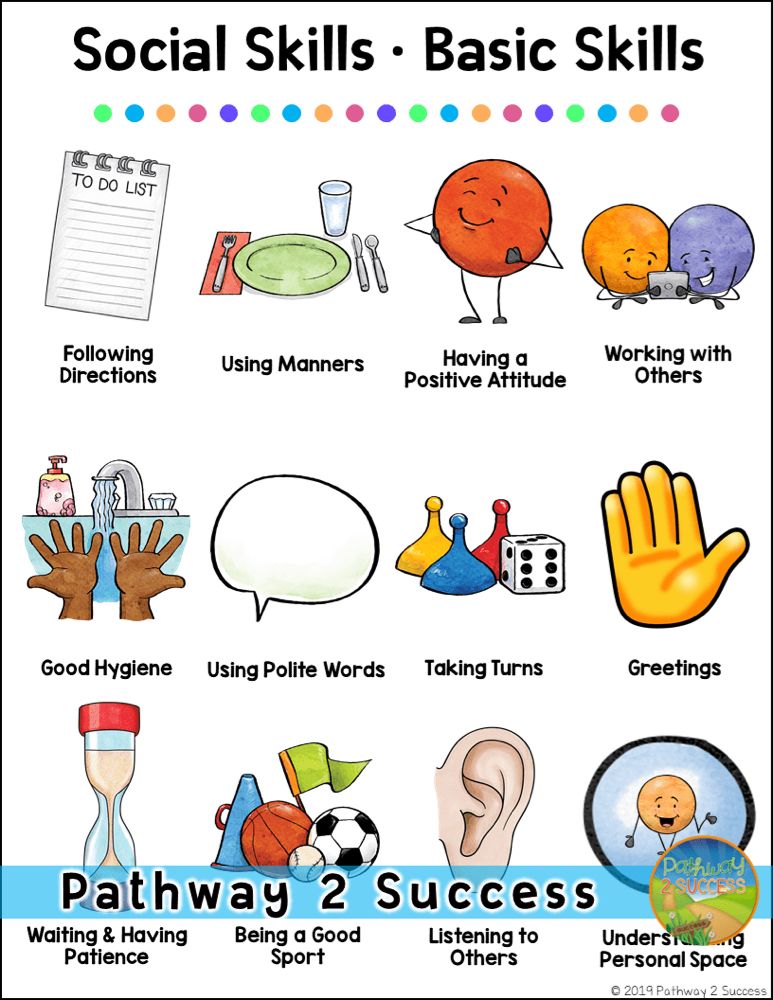

Evidence-based social skills activities for children & teens (w/ teaching tips)

© 2009 – 2021 Gwen Dewar, Ph.D., all rights reserved

These social skills activities can help kids forge positive relationships — and better understand what other people are feeling and thinking.

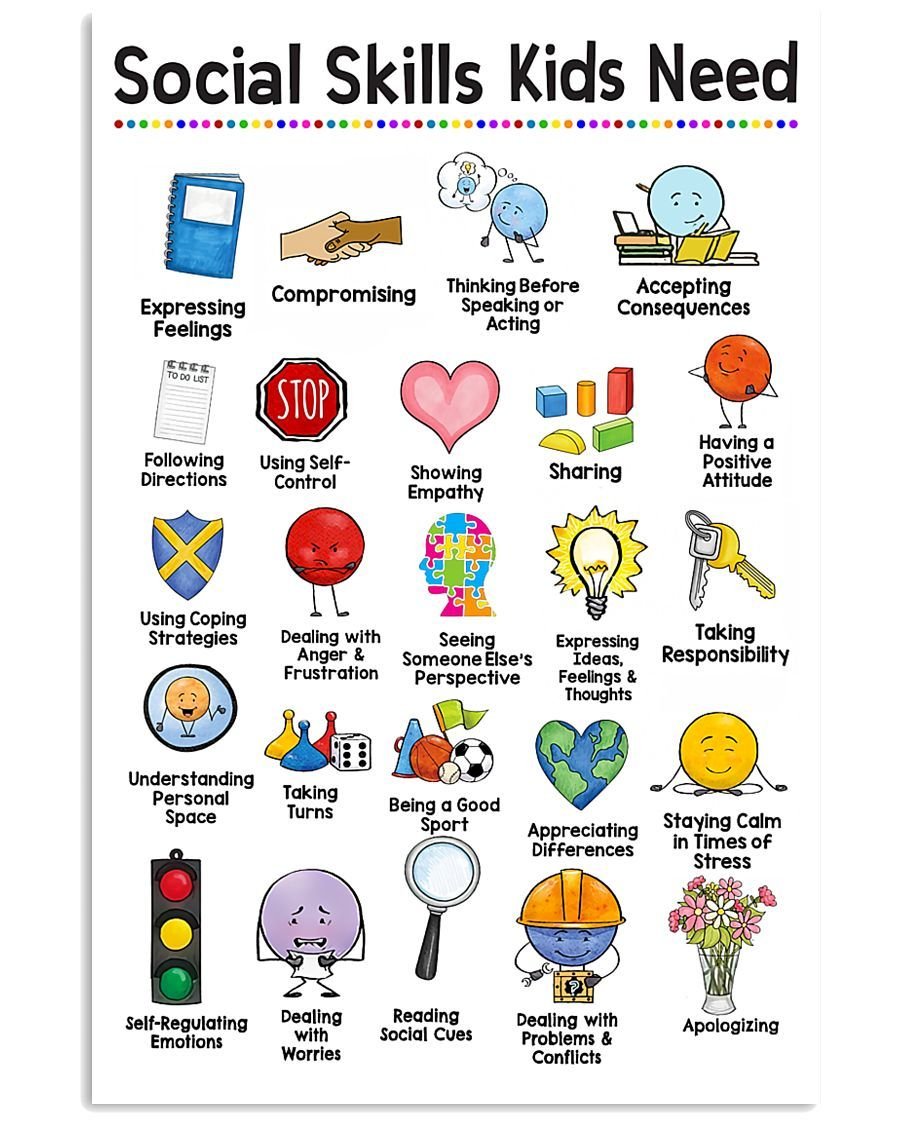

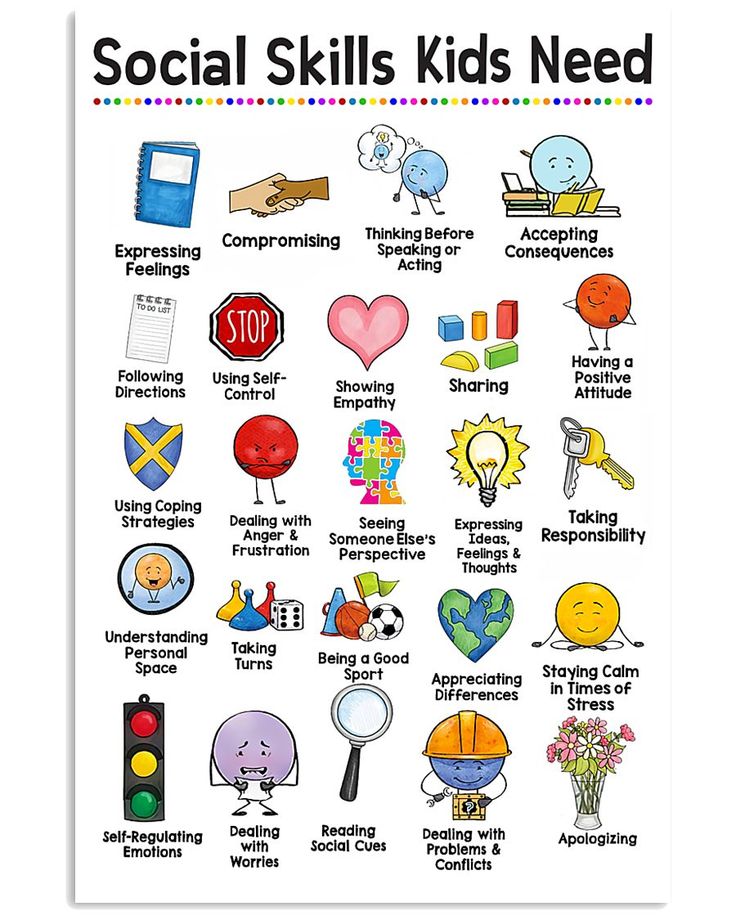

How can we help children develop social competence — the ability to read emotions, cooperate, make friends, and negotiate conflicts? Kids learn when we act as good role models, and they benefit we create environments that reward self-control. But there is nothing quite like practice. To develop and grow, kids need first-hand experience with turn-taking, self-regulation, teamwork, and perspective-taking.

Here are 17 research-inspired social skills activities for kids, organized by age-group. I begin with games suitable for the youngest children, and end with social skills activities appropriate for older kids and teens.

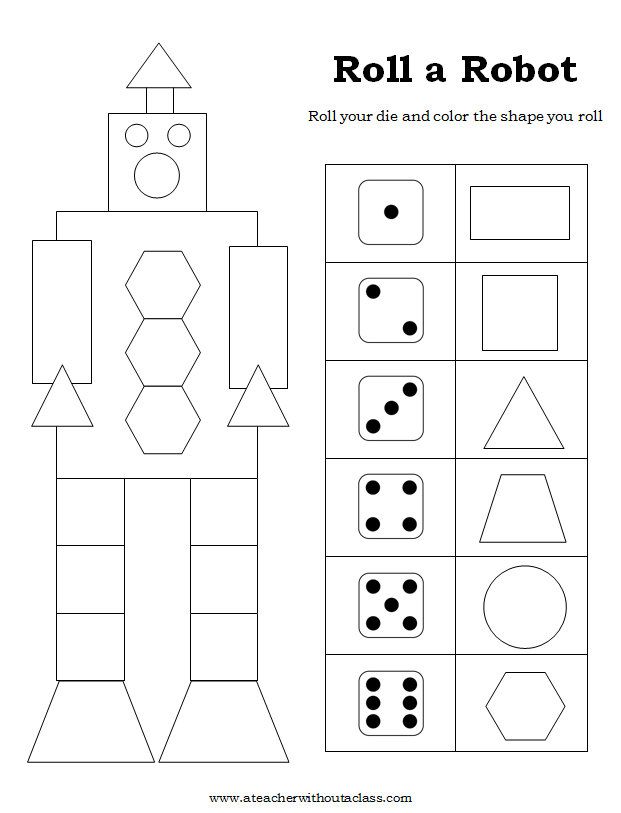

1. Turn-taking games

Young children — including some babies — are capable of spontaneous acts of kindness, but they can be shy around new people. So how can we teach them that a new person is a friend?

One powerful method is to have a child engage in playful acts of reciprocity with the stranger. For example, the child take turns pressing the button on a toy, or rolling a ball back and forth. The child and stranger might hand each other interesting objects.

When psychologists Rodolfo Cortes Barragan and Carol Dweck (2014) tested this simple tactic on 1- and 2-year-olds, the children seemed to flip a switch.

The babies began to respond to their new playmates as people to help and share with. By contrast, there was no such effect if children merely played alongside the stranger — without engaging in acts of reciprocity.

2. The toddler “name game”

As early childhood specialist Kathleen Cochran has noted, many children need help with the fundamentals of getting someone else’s attention. They don’t yet understand that it’s important to speak the person’s name.

“It’s such a simple thing,” Cochran says, “yet it’s the beginning of being able to understand another person’s point of view. ” So how do we teach this concept? Cochran and her colleagues recommend this simple social game (Teachers’ College, Columbia University 1999) :

” So how do we teach this concept? Cochran and her colleagues recommend this simple social game (Teachers’ College, Columbia University 1999) :

- Seat children in a circle, and give one of them a ball.

- Ask this child to choose another person in the circle and speak his or her name. Then the child rolls the ball to named individual.

- Once the ball has been received, the next child follows the same procedure — naming an intended recipient and passing the ball along.

3. Music-making and rhythm games for young children

Young children are often inclined to help other people. How can we encourage this impulse? Research suggests that joint singing and music-making are effective social skills activities for fostering cooperative, supportive behavior.

For example, consider this game.

“Waking Up The Frogs”

First, you take a bunch of preschoolers who don’t know each other, and direct their attention to a “pond” — a blue blanket spread on the floor with several “lily pads” on it. Toy frogs sit on the lily pads.

Toy frogs sit on the lily pads.

Then you tell the children the frogs are sleeping. It’s morning, and the frogs need our help to wake up! So you give the children simple music instruments (like maracas), and ask them to sing a little wake-up song while they walk around the pond in time with the music.

When researchers played this game with 4-year-olds, they subsequently tested the children’s spontaneous willingness to help other kids. Compared with children who had “awakened the frogs” with a non-musical version of the activity, the music-makers were more likely to help out a struggling peer (Kirschner and Tomasello 2010).

4. Preschool games that reward attention and self-control

To get along well with others, children need to develop focus, attention skills, and the ability to restrain their impulses. The preschool years are an important time to learn such self-control, and we can help them do it.

Traditional games like “Simon Says” and “Red light, Green light” give youngsters practice in following directions and regulating their own behavior. For more information, see the research-tested games described in my article about teaching self-control. For additional advice about the socialization of young children, see this Parenting Science article about preschool social skills.

For more information, see the research-tested games described in my article about teaching self-control. For additional advice about the socialization of young children, see this Parenting Science article about preschool social skills.

5. Group games of dramatic, pretend play

To get along with others, kids need to be able to calm themselves down when something upsetting happens. They need to learn to keep their cool. And one promising way for kids to hone these skills is to engage in dramatic make-believe with others.

To try this approach, lead young children in games of joint make-believe, like

- pretending to be a family of non-human animals,

- dressing up as chefs and pretending to bake a cake together, or

- taking turns pretending to be statues (and having peers pose the statues in various ways).

In a randomized experiment of preschoolers from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, Thalia Goldstein and Matthew Lerner found evidence that these these playful scenarios helped children develop better emotional self-regulation (Goldstein and Lerner 2018). After 8 weeks of teacher-led play, kids assigned to play group games of dramatic, pretend play improved more than did children assigned to alternative social skills activities, like playing together with blocks.

After 8 weeks of teacher-led play, kids assigned to play group games of dramatic, pretend play improved more than did children assigned to alternative social skills activities, like playing together with blocks.

6. “Emotion charades” for young children

In this game, one player acts out a certain emotion, and the other players must guess which feeling is being portrayed. In effect, it’s simple version of charades for the very young.

Is it helpful? At the very least, it’s a way to motivate young children to think about and discuss different emotions. And the game has been included (along with several other social skills activities) in a preschool program developed by researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

In a small experimental study, the program, called the “Kindness Curriculum,” was linked with successful outcomes: Compared with kids in a control group, graduates of the “Kindness Curriculum” experienced greater improvements in teacher-rated social competence (Flook et al 2015).

7. Drills that help kids read facial expressions

People who are good at interpreting facial expressions can better anticipate what others will do. They are also more “prosocial,” or helpful towards others.

Experiments suggest that kids can improve their face-reading skills with practice. For more information, see these Parenting Science social skills activities for teaching kids about faces.

8. Checker stack: A game for keeping up a two-way conversation

Some kids, including those with autism spectrum disorders, have difficulty maintaining a conversation with peers. Dr. Susan Williams White has developed a number of social skills activities to help them, including Checker Stack, a game that requires kids to take turns and stay on topic.

To play this two-player game, you need only a set of stackable tokens — like checkers or poker chips — and an adult or peer group to help judge the relevance of each player’s contributions.

The game begins when Player One sets down a token and says something to initiate a conversation. Next, Player Two responds with an appropriate utterance, and places another checker on top of the first one.

Next, Player Two responds with an appropriate utterance, and places another checker on top of the first one.

The players keep taking turns to advance the conversation. How long can they sustain it? How tall can their stack become? When a player says something irrelevant or off-topic, the conversational flow is broken and the game is over (White 2011).

9. Passing the ball: A game for honing group communication skills

Here is another activity recommended by Dr. Susan Williams White — a game where players form a circle, and take turns contributing to a group conversation.

The game begins with a player who starts the chat, and then tosses a ball to someone else in the circle. Next, the recipient responds with an appropriate, relevant contribution of his or her own, and tosses the ball to another child. And so on.

To play successfully, kids must monitor body language. They must pay attention to whomever is speaking, and make eye contact during the exchange of the ball.

White advises that you participate in the game yourself, and, if you notice that one of the kids isn’t getting the opportunity to contribute, you can request that you receive the ball next. Then you can complete your turn by tossing the ball to the child who was left out (White 2011).

You can find this game, Checker Stack, and other social skills activities in White’s book, Social Skills Training for Children with Asperger Syndrome and High-Functioning Autism (see the references section below)

10. Cooperative games

There are many kinds of cooperative social skills games. Some are more sedentary, like the many cooperative board games being sold today. Others are active or physical, like the games “Islands” and “Timeball” invented by William Haskell, and tested on older elementary school students (Street et al 2004).

In one study, researchers found that playing these games over a period of 12 weeks led to small but noticeable improvements in “prosocial” behavior — being kind and helpful towards others (Street et al 2004).

“Islands”

To play “Islands” you need a bunch of young children and some hula hoops — about one hoop for every three kids in the class. Then you spread the hoops out on the ground, and let the kids mill around them. When you whistle, every child must step inside a hoop, and each hoop must contain at least three kids. Children will have to cooperate — and hold onto each other — to fit inside a hoop.

“Timeball”

In this game, kids spread out in an open space, each standing with his or her feet together. One child is given a ball. Then this child passes the ball to someone else, and immediately sits down. The second child repeats the exercise, until all kids are seated.

The catch? The object of the game is to get everyone seated as quickly as possible, and the ball must never touch the ground, so kids need to toss the ball with care. Moreover, when deciding where to pass the ball next, they need to consider how difficult it will be for other kids on subsequent turns: If kids pass the ball in a pattern that leaves some children “stranded” at a distance — making it harder to toss the ball without dropping it — the whole team will lose. So kids will likely want to discuss tactics.

So kids will likely want to discuss tactics.

What are the effects of these and other games?

The most obvious benefit is that they encourage kids to act, well…nicer. In one study, researchers found that playing games like “Islands” and “Timeball,” over a period of 12 weeks led to small but noticeable improvements in children’s prosocial behavior. They tended to show more kindness, helpfulness, and empathy (Street et al 2004).

But other research suggests this could be the tip of the iceberg. For example, studies show that successful experiences with cooperation encourage children to continue the trend: If you cooperate with me today, I’m more likely to cooperate with you tomorrow (Blake et al 2015; Keil et al 2017). So it seems likely that cooperative games could serve as a kind of “ally-making” tool between players.

And it also appears that certain types of cooperative games could help children develop their ability to persuade and convince others with well-reasoned arguments.

“Match animals to the right habitat”

In an experimental study of 5- and 7-year-olds, kids had to work in pairs on a sorting task. They had to match different animal species with an appropriate habit, and explain their decisions.

Half the kids were randomly assigned to a cooperative version of this game, where both players worked together as a team. The remaining children played the game competitively. And what happened? The kids who played the cooperative game offered more justification for their ideas. They were also more likely to produce arguments that considered both sides of the question (Domberg et al 2018).

You can read more about the study — and the benefits of cooperative games — in this Parenting Science article.

11. Cooperative construction

Another form of play that promotes cooperation is team construction. When kids create something together with blocks, they must communicate, negotiate, and coordinate. Do such social skills activities make a difference?

It makes sense intuitively, and there is scientific evidence that a specialized program of cooperative construction therapy — called “LEGO®-based therapy” — can help kids who need extra support to develop their social communication skills (Owens et al 2008).

In a recent review of published studies, researchers concluded that “LEGO®-based therapy” is a “promising treatment” for enhancing social interactions with kids on the ASD spectrum (Narzisi et al 2020). If you had a child with special needs, it’s worth asking your pediatrician about this form of therapy.

I haven’t found any rigorous experiments on the subject, but it makes sense that cooperative gardening could help kids hone social skills, and observational research supports the idea.

Kids tend to improve their social competence when they engage in community-based or school-based gardening (Ozer et al 2007; Block et al 2012; Gibbs et al 2013; Pollin and Retzlaff-Fürst 2021).

What sorts of things can children do in the garden? Take a cue from a recent study of cooperative gardening in 6th graders. The kids were assigned to groups, and each group was given the responsibility for tending a specific garden bed. In addition, kids were asked to identify different plants, document plant growth, conduct soil tests, and make observations of snails (Pollin and Retzlaff-Fürst 2021).

13. Story-based discussions about emotion

Here’s a social skills activity you can try just about anywhere: Read a story with emotional content, and have kids talk about it afterwards.

Why did the main character get angry? What kinds of things make you get angry? What do you do to cool off? When kids participate in group conversations about emotion, they reflect on their own experiences, and learn about individual differences in the way people react to the world. And that understanding may help kids develop their “mind-reading” abilities.

In one study, 7-year-old school children met twice a week to discuss an emotion featured in a brief story. Sometimes their teachers encouraged them to talk about recognizing the signs of a given emotion. In other sessions, the kids discussed what causes emotions, or shared ideas about how to handle negative emotions (“When I feel sad, I play video games,” or “I feel better when my mother hugs me”).

After two months, participants outperformed peers in a control group, showing significant improvements in their understanding of emotion. They also scored higher on tests of empathy and “theory of mind” — the ability to reason about other people’s thoughts and beliefs (Ornaghi et al 2014).

They also scored higher on tests of empathy and “theory of mind” — the ability to reason about other people’s thoughts and beliefs (Ornaghi et al 2014).

14. Classic charades for older kids and teens

We’ve already mentioned “Emotion Charades” for young children. The traditional or classic version of the game is also an excellent activity for honing social skills among older kids.

Consider why. In the traditional game, a player draws a slip of paper from a container and silently reads what is written there — a phrase that describes a situation (like “walking the dog”) or that names a famous book, film, song, or television show. Then, through pantomime, the player tries to convey this phrase to his or her unknowing team-mates.

What gestures are most likely to communicate the crucial information? To perform an effective pantomime, you need to be good at perspective-taking, or imagining what viewers need to see in order to guess the answer. You also have to stay focused on the rules, and refrain from talking.

And if you are one of the players who must guess the answer? Once again, mind-reading is important. In fact, there is evidence that watching charades switches our brains into “mind-reading mode.”

During a study using fMRI scans, players observing gestures experienced enhanced activity in the temporo-parietal junction, a part of the brain associated with reflecting on the mental states of other people (Schippers et al 2009).

It seems, then, that charades encourages kids to think about other perspectives, and fine-tune their nonverbal communication skills.

15. Team athletics that feature training in good sportsmanship

Research suggests that team athletics can function as effective social skills activities — if adults model the right behavior, and actively teach kids to be good sports.

In one study, elementary school students who received explicit instruction in good sportsmanship showed greater leadership and conflict-resolution skills than did their control group peers (Sharpe et al 1995).

In another study, researchers found that adolescents displayed better social skills if their athletic coaches took a democratic approach to leadership, and offered lots of social support and positive feedback. When kids perceived the coach to be autocratic, they were less likely to report growth in social competence (de Albuquerque et al 2021).

And — in a variety of studies — researchers have found that players are more likely to stay motivated and positive if their coaches avoid authoritarian tactics, like intimidation, threats, and the manipulative use of rewards (e.g., Sevil-Serrano et al 2021).

So what’s a good way to ensure that kids learn the right lessons from team sports?

It sounds like adults need to allow kids to participate in decisions about a team’s goals. They also need to maintain a pleasant, emotionally supportive relationship with athletes, and motivate kids with positive comments about their successes. And it makes sense to actively instruct kids on the principles of good sportsmanship, including

- Being a good winner (not bragging; showing respect for the losing team)

- Being a good loser (congratulating the winner; not blaming others for a loss)

- Showing respect to other players and to the referee

- Showing encouragement and offering help to less skillful players

- Resolving conflicts without running to the teacher

During a game, we should give kids the chance to put these principles into action before we swoop in. And when the game is over, we should give kids feedback on their good sportsmanship.

And when the game is over, we should give kids feedback on their good sportsmanship.

These become increasingly important as kids get older, and they require more than empathy and good manners. They also require more than native “smarts.”

Studies indicate that most people — regardless of IQ — fall prey to “myside bias” — the tendency to evaluate neutral evidence in favor of one’s personal interests (Stanovich et al 2013).

But that doesn’t mean we can’t fight this tendency. People become less prone to myside bias as a function of the years they spend in higher education, even after controlling for age and cognitive ability (Toplak and Stanovich 2003). So it seems likely that kids will benefit if we expose them to diverse viewpoints, debate, and the tools of critical thinking.

One classic approach is to assign students to take turns advocating both sides of a given debate. Not only will kids practice perspective-taking, they will hone critical thinking skills. For more information, see my article about training kids to engage in formal, disciplined debate.

Researchers Geoff Kauffman and Anna Flanagan perceive a problem with many “consciousness-raising” social skills activities: They’re too preachy, and that tends to turn people off.

So Kauffman and Flanagan recommend a more subtle approach, one that embeds the social message in a fun, lighthearted game. To date, Flanagan has created two such games.

The first is a card game called the Resonym Awkward Moment Card Game, a party game that requires players to choose solutions to thorny social problems. It has been tested on kids as young as 11 years old, and found to improve players’ perspective-taking skills. Compared to students in a control group, kids who played this game showed subsequent improvements in their ability to imagine another person’s perspective (Kaufman and Flanagan 2015).

They were also more likely to reject social biases, and imagine females pursuing careers in science. In addition, they showed more interest in confronting detrimental social stereotypes (Kaufman and Flanagan 2015).

The second game, called the Buffalo The Name Dropping Game, is intended for ages 14 and up. Buffalo asks players to think of real or fictional examples of people who fit a random combination of descriptors (like tattooed grandparent, misunderstood vampire, or Asian descent comedian).

After playing this game, high school students showed increased motivation to recognize and check their social biases, agreeing more strongly with statements like “I attempt to act in non-prejudiced ways toward people from other social groups because it is personally important to me” (Kaufman and Flanagan 2015).

Both the Resonym Awkward Moment Card Game and Buffalo The Name Dropping Game are available from Amazon. If you purchase them through these links, a small portion of the proceeds will benefit this website.

For more information about boosting social competence, see my evidence-based tips for fostering friendships, teaching empathy, and encouraging kindness. In addition, check out my article about promoting preschool social skills, as well as my article about the potential benefits of playing prosocial video games.

In addition, check out my article about promoting preschool social skills, as well as my article about the potential benefits of playing prosocial video games.

Bakeman R, Adamson LB, Konner MJ, and Barr RG. 1990. !Kung infancy: The social context of object exploration. Child Development 61: 794-809.

Blake PR, Rand DG, Tingley D, Warneken F. 2015. The shadow of the future promotes cooperation in a repeated prisoner’s dilemma for children. Sci Rep. 5:14559.

Block K, Gibbs L, Staiger PK, Gold L, Johnson B, Macfarlane S, Long C, Townsend M. 2012. Growing community: the impact of the Stephanie Alexander Kitchen Garden Program on the social and learning environment in primary schools. Health Educ Behav. 39(4):419-32.

Cortes Barragan R and Dweck CS. 2014. Rethinking natural altruism: simple reciprocal interactions trigger children’s benevolence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.111(48):17071-4.

de Albuquerque LR, Scheeren EM, Vagetti GC, de Oliveira V. 2021. Influence of the Coach’s Method and Leadership Profile on the Positive Development of Young Players in Team Sports. J Sports Sci Med. 20(1):9-16.

J Sports Sci Med. 20(1):9-16.

Domberg A, Köymen B, Tomasello M. 2018. Children’s reasoning with peers in cooperative and competitive contexts. Br J Dev Psychol. 36(1):64-77.

Flook L., Goldberg S.B., Pinger L., and Davidson R.J. 2015. Promoting prosocial behavior and self-regulatory skills in preschool children through a mindfulness-based Kindness Curriculum. Dev Psychol. 51(1):44-51.

Gibbs L, Staiger PK, Townsend M, Macfarlane S, Gold L, Block K, Johnson B, Kulas J, Waters E. 2013. Methodology for the evaluation of the Stephanie Alexander Kitchen Garden program. Health Promot J Austr. 24(1):32-43.

Goldstein TR and Lerner MD. 2018. Dramatic pretend play games uniquely improve emotional control in young children. Dev Sci. 21(4):e12603.

Kaufman G and Flanagan M. 2015. A psychologically “embedded” approach to designing games for prosocial causes. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace,9(3), article 1.

Keil J, Michel A, Sticca F, Leipold K, Klein AM, Sierau S, von Klitzing K, White LO. 2017. The Pizzagame: A virtual public goods game to assess cooperative behavior in children and adolescents. Behav Res Methods. 49(4):1432-1443.

2017. The Pizzagame: A virtual public goods game to assess cooperative behavior in children and adolescents. Behav Res Methods. 49(4):1432-1443.

Kirschner S and Tomasello M. 2010. Joint music making promotes prosocial behavior in 4-year-old children. Evolution and Human Behavior 31(5): 354-364.

Lancy D. 2012. Ethnographic perspectives on cultural transmission/acquisition. Paper prepared for School of Advanced Research, Santa Fe, Multiple Perspectives on the Evolution of Childhood. November 4-8, 2012.

Lancy D. 2008. The anthropology of childhood: Cherubs, chattel and changelings. Cambridge University Press.

Legoff DB and Sherman M. 2006. Long-term outcome of social skills intervention based on interactive LEGO play. Autism. 10(4):317-29.

Ozer EJ. 2007. The effects of school gardens on students and schools: conceptualization and considerations for maximizing healthy development. Health Educ Behav. 34(6):846-63.

Pellegrini AD, Dupuis D, and Smith PK. 2007. Play in evolution and development. Developmental Review 27: 261-276.

Pellegrini AD and Smith PK. 2005. The nature of play: Great apes and humans. New York: Guilford.

Pollin S, Retzlaff-Fürst C. 2021. The School Garden: A Social and Emotional Place. Front Psychol. 12:567720.

Sevil-Serrano J, Abós Á, Diloy-Peña S, Egea PL, García-González L. 2021. The Influence of the Coach’s Autonomy Support and Controlling Behaviours on Motivation and Sport Commitment of Youth Soccer Players. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(16):8699.

de Albuquerque LR, Scheeren EM, Vagetti GC, de Oliveira V. 2021. Influence of the Coach’s Method and Leadership Profile on the Positive Development of Young Players in Team Sports. J Sports Sci Med. 20(1):9-16.

Sharpe T, Brown M and Crider K. 1995. The effects of a sportsmanship curriculum intervention on generalized positive social behavior of urban elementary students. Journal of applied behavior analysis 28(4): 401-416.

Spinka, M. , Newberry, RC, and Bekoff, M. 2001. Mammalian play: Training for the unexpected. Quarterly Review of Biology 76: 141-16.

Stanovich KE, West RF, Toplak ME. 2013. Myside Bias, Rational Thinking, and Intelligence. Current Directions in Psychological Science 2(4): 259-264.

Street H, Hoppe D, and Ma T. 2004. The Game Factory: Using Cooperative Games to Promote Pro-social Behaviour Among Children. Australian Journal of Educational & Developmental Psychology. 4:997-109.

Teacher’s College, Columbia University. 1999. Conflict resolution for preschoolers. TC Media Center website. Accessed on 9/28/2015 at http://www.tc.columbia.edu/news.htm?articleID=4023.

Weiss MJ and Harris SL. 2001. Teaching social skills to people with autism. Behav Modif. 25(5):785-802.

White SW. 2011. Social Skills Training for Children with Asperger Syndrome and High-Functioning Autism. New York: The Guilford Press.

Portions of this article are adapted from an earlier work about social skills activities by the same author.

Image credits for “Social skills activities”:

image of children’s faces in a circle by Wavebreakmedia / istock

Image of preschoolers with musical instruments by Liderina / shutterstock

Content of “Social Skills Activities” last modified 9/2021

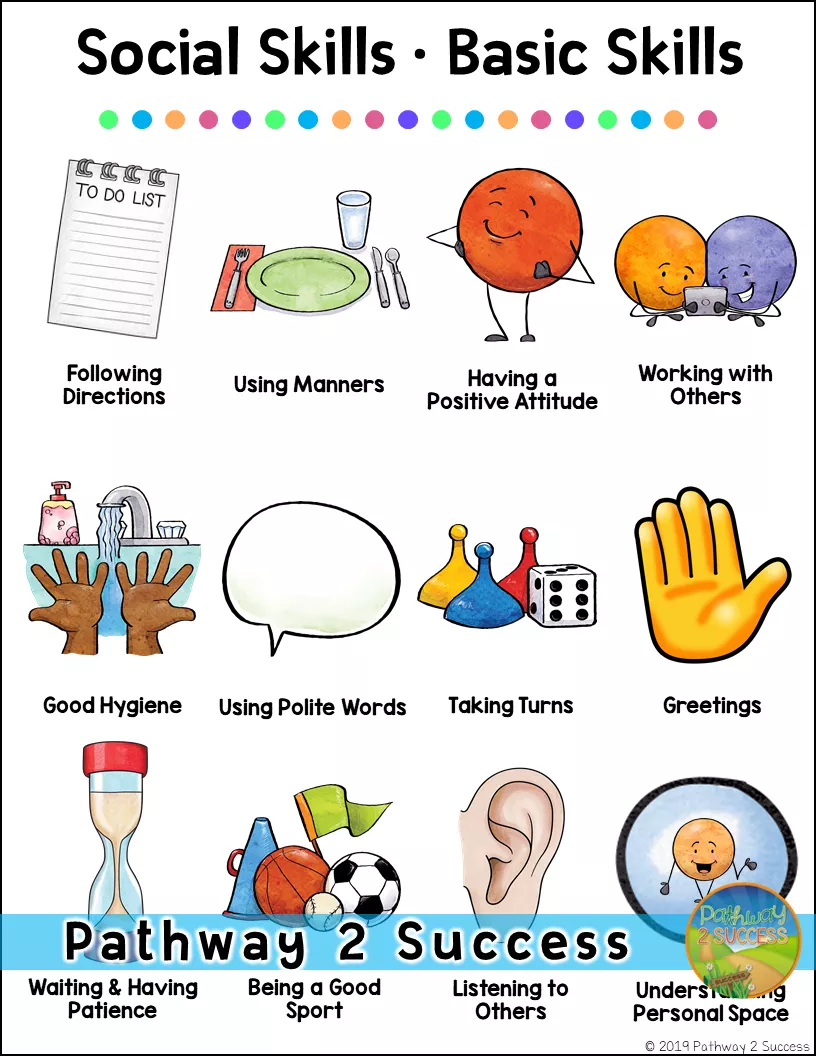

Social Skills Training for Kids: Top Resources for Teachers

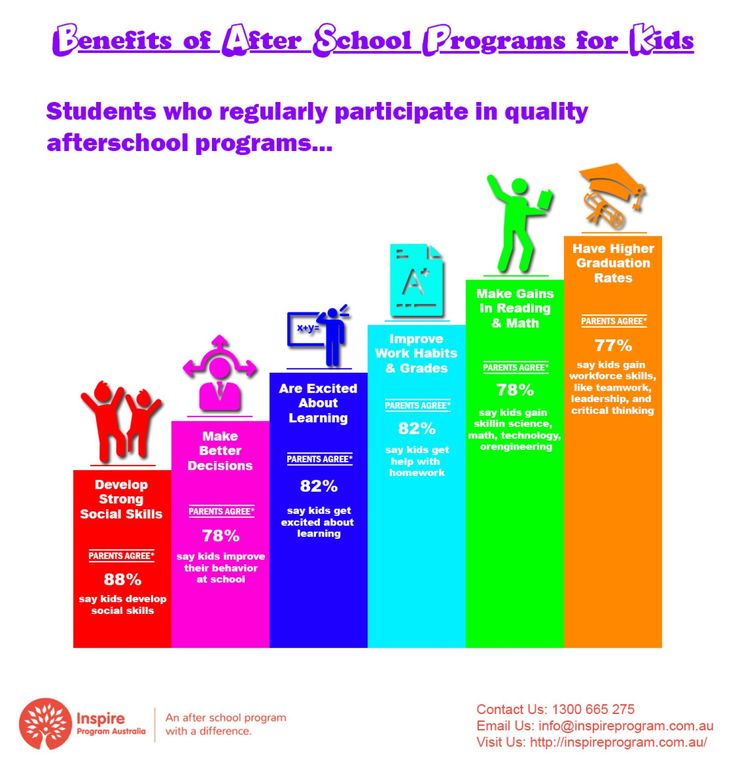

School is a place where children and adolescents go to become educated, academically and socially.

Learning how to interact with other people, make friends, and foster cooperation are all social skills that are taught by facilitating students’ interactions with each other.

Even though children gain social skills through naturally interacting with others, since most of these interactions take place at school, it is essential that teachers master the elements of social skills training to facilitate social development in their students.

This article will provide guidance on social skills training for teachers and resources to help integrate social skills training for all stages (i. e., toddlers, young children, and teenagers). Also included are lesson plans to help break down social skills education.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Emotional Intelligence Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will enhance your ability to understand and work with your emotions and give you the tools to foster the emotional intelligence of your clients or students.

This Article Contains:

- How Do Social Skills Develop?

- Fostering Social Skills in Toddlers

- 3 Important Social Skills for Teenagers

- Teaching Social Skills 101

- Social Skills Training for Kids: 3 Games & Activities

- 4 Online Games & Board Games

- Resources for Teachers: 3 Lesson Plans & Tips

- PositivePsychology.com’s Helpful Tools

- A Take-Home Message

- References

How Do Social Skills Develop?

Similar to riding a bike, social skills cannot be developed without practice. Arguably, the abilities to understand and consider another’s worldview are two of the most fundamental pieces of social interaction.

Theory of mind, which develops in a child’s preschool years, refers to the ability to understand that another individual’s perspective differs from yours (Moll & Meltzoff, 2011). The development of theory of mind takes place throughout childhood in a predictable manner, as outlined below (Lowry, 2015; Ruhl, 2020):

- Wanting:

Understanding that people do not always want the same things and act in a variety ways to get the things they want. - Thinking:

Understanding that people may have differing beliefs about the same event or topic. - Knowledge:

Recognizing that everyone’s access to knowledge is different, and if they have not seen it, they may need additional context to understand. - False beliefs:

Recognizing that different people may have false beliefs that differ from reality. - Hidden feelings:

Understanding that people can hide their emotions and feel a different emotion than the one they are displaying.

The development of these theory-of-mind concepts eventually leads to children becoming better at another key social skill: perspective taking.

Perspective taking refers to an individual’s ability to understand both visual (viewpoint) and perceptual (understanding) situations (Duffy, 2019). Perspective taking develops over the course of the preschool years and continues throughout childhood and adolescence.

Think of a conversation or experience when another person was incredibly rigid about their beliefs and lacked interest in hearing about your experiences. That individual may not have developed the necessary skills to engage in perspective taking and may lack flexibility in accepting that others’ beliefs may be different from their own.

Fostering Social Skills in Toddlers

If you are a parent or educator, you understand that it’s difficult to get younger children, especially toddlers, to ‘tune in,’ as development can be so varied across different individuals.

When considering strategies to help foster social skills in toddlers, you should not underestimate the significance of pretend play and role-play.

For example, if your child is playing doctor and wants you to play with them, it is important to stay ‘in character’ and take off the parent or teacher hat while you are playing with them. This will allow children to become comfortable playing different roles and developing a variety of skills in everyday life.

A few other strategies for caregivers and early childhood educators to foster social skills in toddlers include:

- Follow the toddler’s lead

Start by observing the toddler while they are playing. Get onto their level (crouch or sit down) and join the play by copying their actions. Slowly, add more as the play develops. - Put your child’s perspective into words

Even if your toddler is not talking yet, putting their actions/feelings or your own into words can be helpful in developing perspective taking.It can also encourage them to use more language when communicating, rather than just actions or words.

- Use picture books to help discuss feelings

When learning about feelings, having pictures that display the feelings your toddler might be experiencing is helpful in having them visualize what these feelings look like. Providing dialogue such as “Oh, Pig’s mouth is pointed downward, and he has a tear. He seems sad,” can also help toddlers understand what emotions look like.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

3 Important Social Skills for Teenagers

In today’s technology-driven society, developing social skills can be more difficult for young adults and teenagers. Considering that a lot of their social activity is powered by devices, there are fewer opportunities for them to engage in meaningful in-person interactions.

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “Children’s capacity to achieve goals, work effectively with others and manage emotions will be essential to meet the challenges of the 21st century” (OECD, 2015). Social skills that apply to goal attainment, cooperation, and emotional awareness include:

1. Active listening

Active listening is a type of listening that focuses on hearing the words another person is saying as well as recognizing the emotions that come out through their nonverbal behavior.

A good activity to practice active listening with adolescents and teenagers is to ask all participants to sit in a circle. The facilitator then chooses one participant to tell a story. After three to five sentences, the teacher says ‘stop’ and chooses another student to continue the story. This person now has to repeat the last sentence the previous person said and continue making up the story.

2. Assertiveness

Assertive communication is characterized by the ability to express one’s opinions, feelings, or attitudes while still respecting the perspectives of others.

The most important piece of teaching assertiveness is to assure teens it’s okay to claim their rights and express their opinions and feelings, especially when saying “no” respectfully.

3. Self-awareness

Being aware of one’s emotions is an important component of self-awareness. Understanding why they feel a certain way and their emotions in specific situations is an essential part of the development of teenagers’ empathy.

Empathy not only helps teenagers understand the emotions others are feeling, but also allows them to understand when they are feeling specific emotions and implement specific coping strategies to help them.

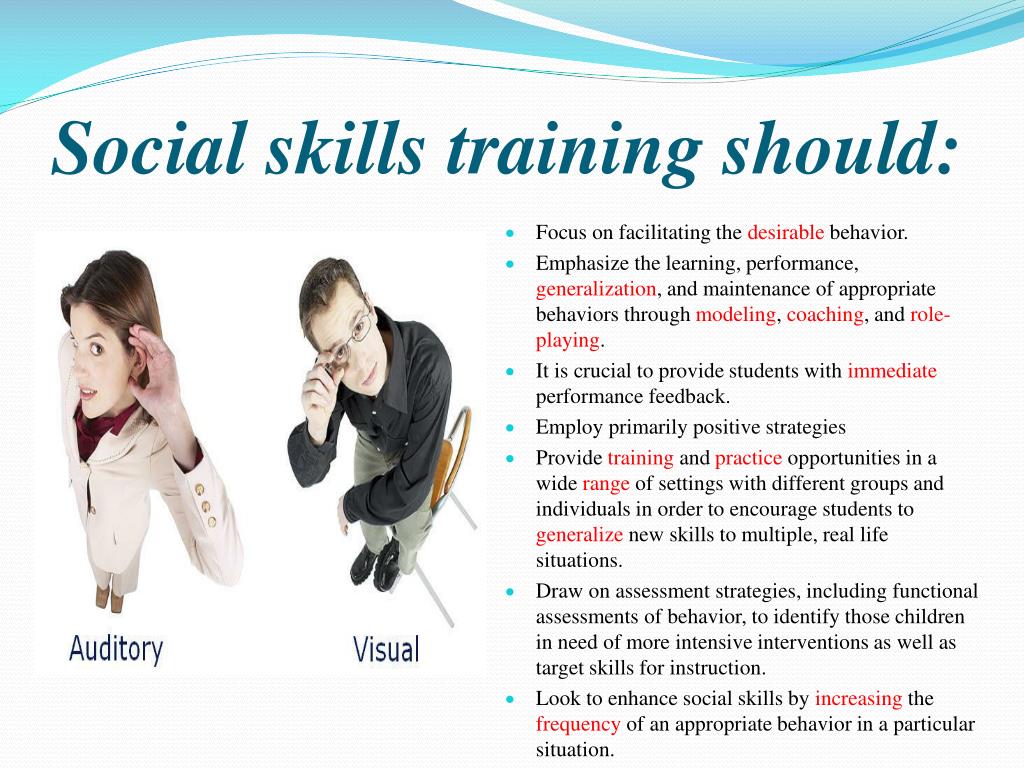

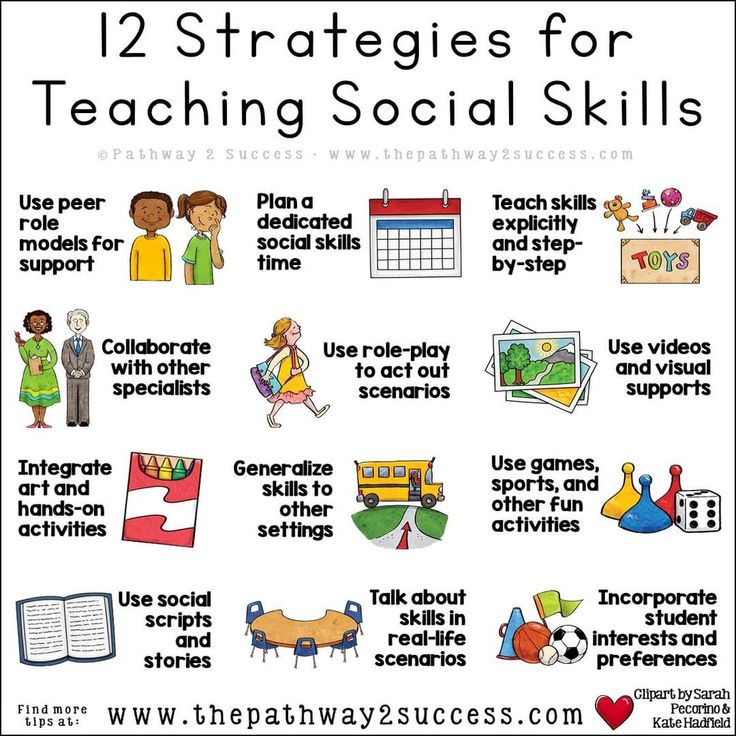

Teaching Social Skills 101

Engaging in social skills training can be overwhelming, especially as a teacher or caregiver, as there are so many other things to attend to.

A specific challenge that teachers face when integrating social-emotional education is integrating activities and social education into the daily curriculum.

The easiest way to do this is through short, simple activities and games that require little preparation and can be quickly set up during down times and transitions. Below, we have provided several options for integrating social skills education, whether you are a teacher, therapist, parent, or caregiver looking to enhance your child’s social skills.

Social Skills Training for Kids: 3 Games & Activities

Activities that can be played across all age groups to promote social skills education include:

1. Charades

Charades is a simple way for children to understand perspective taking, as participants are asked to write things from different categories (i.e., movies, television shows, or games).

Participants then act out the thing they select using only gestures, and other players have to guess. Since participants are communicating using only gestures, the other players have to consider their perspectives when guessing, as the person who is acting out the thing may have a different understanding or experience than they do.

2. Passing the ball

The game begins with a player starting a conversation. The teacher can give a topic to start with or allow the players to choose. It is recommended that the teacher use a timer to help time each player’s contribution so they do not talk for too long (approximately 20–30 seconds).

After the player who is holding the ball starts the conversation, they throw the ball to another person, who chimes in with a related contribution. Players must maintain eye contact with the person they are speaking to during the exchange (White, 2011).

3. Checker stack

This is a three-player game. To play this game, you need a set of stackable tokens (i.e., checkers, poker chips, coins) and a judge. The judge can be an adult or another peer, and they will judge each player’s contribution.

The game begins when the first player sets down a token and says something to start a conversation. The second player responds and stacks another token on top. The players keep taking turns stacking and talking, with the judge providing feedback when necessary. The game ends when one player says something irrelevant or off-topic, or when the tower falls down (White, 2011).

To help participants understand what this looks like, we recommend that the teacher model a round of the game, using two students as an example so participants can understand how the game is played. Participants should also rotate being the judge to practice perspective taking.

4 Online Games & Board Games

Turn taking and role-play are two skills promoted through games that can contribute to the development of social skills across all ages. Games that can help promote these skills include:

1. Apples to Apples Jr.

This game is probably one of the most natural ways to practice perspective taking for children.

At the start of the game, each player is given ‘red apple’ cards that have descriptions written on them. Each player takes turns playing the judge and selects a ‘green apple’ card, which has a one-word characteristic on it such as “amazing” or “scary.”

All the other players are then required to choose a description that they feel matches the ‘green apple’ card. Once all the ‘red apple’ cards are on the table, each player has the opportunity to convince the judge why their selection is best.

This activity gives children the opportunity to practice perspective taking, as they have to convince each other in a socially acceptable way why they think their card is a good match.

Available on Amazon.

2. Hall of Heroes

Hall of Heroes is marketed as an online middle school game where students encounter real-world social situations that they will face in middle school (e.g., bullying, peer pressure, and making new friends).

Players can choose their character and build their skills during gameplay. By providing a virtual setting where students can make mistakes and examine the impact of their decisions, young adults will be able to see the consequences of their decisions.

Characters in the game also come back with assertive retorts; for example, when faced with a situation where another student is told they cannot sit at the lunch table, one character says “Hey, didn’t I just see you come in with another kid? Did you just ditch them to come over here?”

This kind of dialogue allows young adults who are struggling to be assertive to adopt the strategies and words the characters are using when dealing with difficult situations in their own lives.

Available on Centervention. A 30-day free trial is available for educators.

3. My Feelings Game

This board game is targeted for children between the ages of 4 and 11. The goal of the game is to encourage children to recognize common feelings in themselves and others.

The game has 280 everyday situations and 7 characters who are aptly named with the most common feelings that children experience (i.e., anger, happiness).

Children are asked to do a variety of tasks that include identifying their emotions on pictures of faces, adding context to a list of typical experiences they have with a particular emotion, and acting out specific scenarios.

This provides an opportunity for children to further examine the perspectives of others. The characters provide scenarios that make them feel certain feelings (i.e., “I am happy when my mom gives me a treat”), and then players expand on things that make them happy, combining emotional awareness and perspective taking. The game also includes movement breaks so the children can move around while they are playing.

Available on Sensational Learners.

4. TeachTown Social Skills

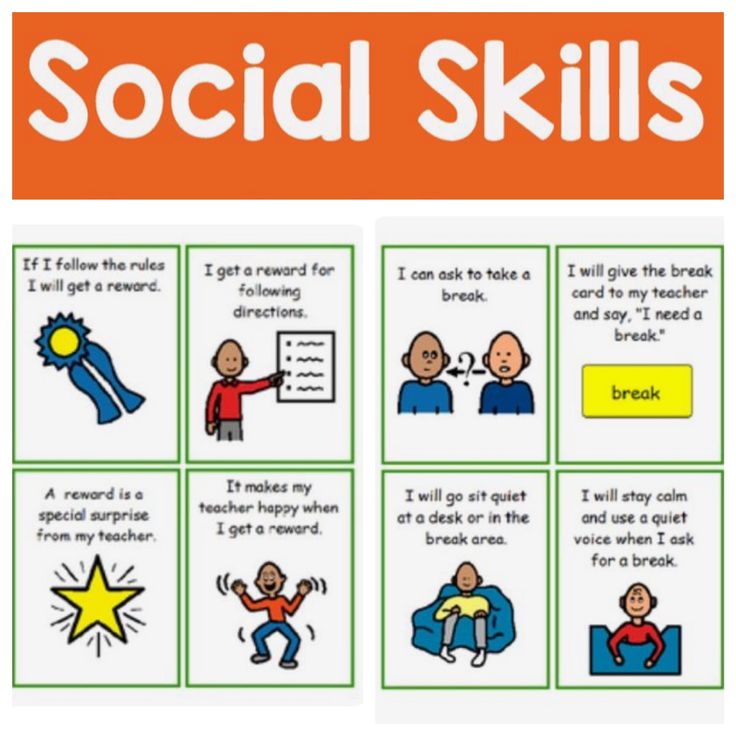

TeachTown Social Skills guides younger children (ages 4–12) through an interactive curriculum with the goal of teaching socially appropriate behaviors.

TeachTown is designed for children with special needs, as the game targets five behavioral domains:

- Following the rules

- Good communication

- Coping & self-regulation

- Friendship

- Interpersonal skills

Each of the domains contains 10 target social behaviors that are highlighted through videos, social skills worksheets, and lesson plans to help children understand appropriate social behaviors and responses to different situations.

The behavioral domains specifically target areas where these children struggle, and through the use of social storytelling and modeling, they help educate children in real time how to react to specific situations.

Each lesson plan can also be integrated into therapeutic interventions these children might already be receiving, which helps tie in social skills education to both school and therapeutic settings.

Available on TeachTown.

Resources for Teachers: 3 Lesson Plans & Tips

One of the major challenges teachers face when integrating social and emotional content across the curriculum is the ability to have materials they can quickly integrate in the classroom.

Even though lesson and course planning is an integral part of a teacher’s preparation for learning, the classroom is a fluid space where things happen rapidly without warning.

To help accommodate this, we have provided lesson plans and activities that you can implement on the fly, specifically in difficult social situations that may arise as your students go through their daily activities. Similar to the interactive activities above, these lesson plans can be adapted for use across all ages.

1.

In this activity, students create a “wanted” poster for a friend. Students can use the template provided or make their own poster.

This activity helps students identify qualities that are present in a good friend and examine whether those qualities are present in themselves.

2. How to apologize

Part of being a good friend and colleague is learning how to admit when you have done something wrong. This lesson plan provides steps for crafting a good apology and role-playing activities for students to practice saying sorry in different situations.

3. Understanding empathy

Putting yourself in another’s shoes and understanding another’s feelings are important parts of developing social skills. This lesson helps students understand what empathy is and promotes strategies to use empathy in their everyday lives.

PositivePsychology.com’s Helpful Tools

PositivePsychology.com provides several resources that can be adapted for teachers aiming to help their students develop social skills.

This article lists recommended empathy books to help cultivate compassion and empathy in your students. It also provides specific books for adults and teachers that are relevant to their everyday lives.

Mindfulness can be an important component for adults, teenagers, and children in practicing self-reflection, which ultimately leads to an increased ability to display empathy and perspective taking. These Mindfulness Worksheets can be used by teachers and other practitioners when practicing mindfulness with their students and for themselves.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others communicate better, this collection contains 17 validated positive communication tools for practitioners. Use them to help others improve their communication skills and form deeper and more positive relationships.

A Take-Home Message

While the development of social skills can be a difficult component to integrate into everyday teaching, it is an essential component of emotional and positive education that should be emphasized at every age.

Even if you do not have time to engage in specific social skill instruction daily, the strongest predictor of success is continued interaction. Ensuring that your students have time to interact in controlled and uncontrolled group settings and with peers of various ages is the best way to ensure that students have opportunities to practice social skills, specifically perspective taking and empathy.

Suggested read: Social Skills Support Groups: 10 Helpful Activities & Games

We hope this article provided you with resources and ideas to use in your classroom or home. Please let us know if you have any strategies that are not listed here that could work for your fellow educators. Remember, we are all in this together, and sharing a resource or an idea could help another individual integrate more meaningful content into their classroom.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Emotional Intelligence Exercises for free.

- Duffy, J.

(2019, June 2). The power of perspective taking. Psychology Today. Retrieved April 1, 2021, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/the-power-personal-narrative/201906/the-power-perspective-taking

- Lowry, L. (2015). “Tuning in” to others: How young children develop theory of mind. The Hanen Centre. Retrieved April 1, 2021, from https://www.dsrf.org/media/Developing%20theory%20of%20mind%20tuning%20into%20others.pdf

- Moll, H., & Meltzoff, A. N. (2011). Perspective-taking and its foundation in joint attention. In N. Eilan, H. Lerman, & J. Roessler (Eds.), Perception, causation, and objectivity. Issues in philosophy and psychology (pp. 286–304). Oxford University Press.

- OECD. (2015). OECD skills studies: Skills for social progress: The power of social and emotional skills. OECD Publishing.

- Ruhl, C. (2020). Theory of mind. Simply Psychology. Retrieved April 1, 2021, from https://www.simplypsychology.

org/theory-of-mind.html

- White, S. W. (2011). Social skills training for children with Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. Guilford Press.

Social skills training • Mosaic

What is a good way to teach social skills, especially in the group?

I work with children with autism. I confidently teach them academic and everyday skills, but, unfortunately, not social ones. I need a simple and effective flexible learning method as I need to teach a variety of skills to children of different levels. Many of my students have intermediate or advanced language skills but find it difficult to make friends and maintain relationships. Since it is not possible to organize individual work with each student, something is needed that can be done in a group. Any suggestions?

Answered by Shanti Stockley, Master of Education (MEd), Certified Behavior Analyst (BCBA), Licensed Behavior Analyst (LBA) Autism Treatment Association.

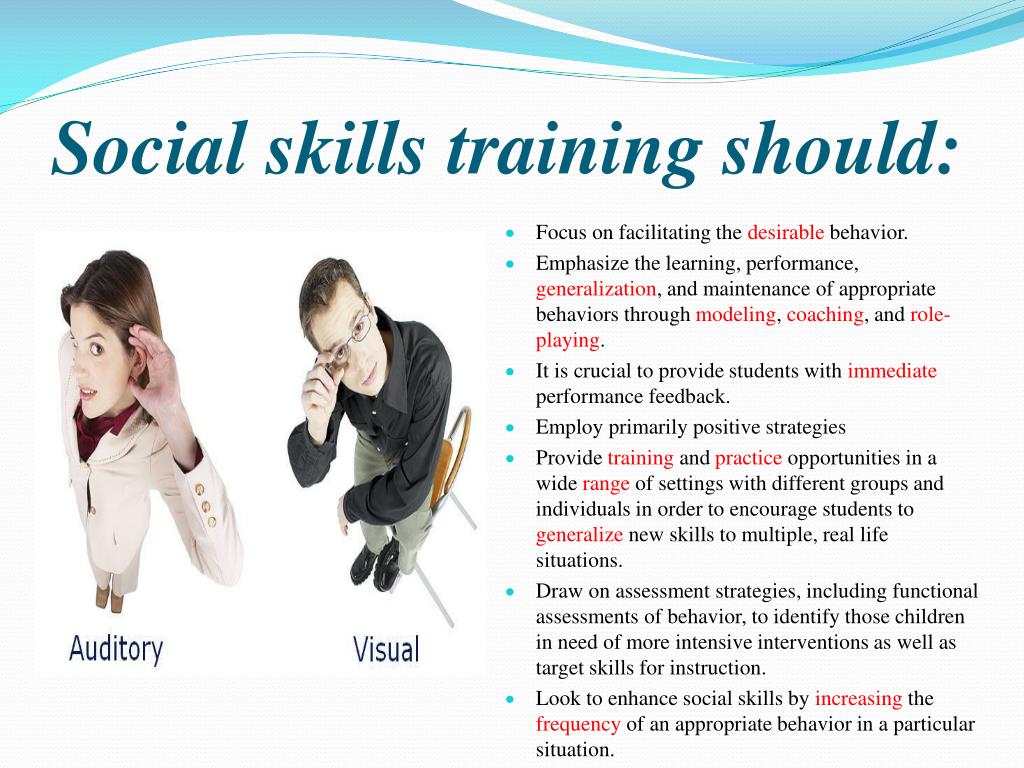

Although the amount of research available on social skills education is increasing, this question remains very common. It can be difficult for educators to find evidence-based curricula and strategies. One strategy that has proven effective in teaching social skills to children of different levels in groups is the Teaching Interaction Procedure (TIP). The learning interaction method is a 6-step process in which the educator names and defines the skill being learned, explains the need for its application, describes the steps necessary to perform it correctly, demonstrates this skill, conducts practical exercises with students in the form of a role-play, and also gives give them feedback and reinforcement. Over the past ten years, this procedure has been repeatedly studied, including its use in individual work with a child (for example, Leaf et al., 2009), in groups (e.g. Leaf, Dotson, Oppeneheim, Sheldon and Sherman, 2010) and in schools (Tullis and Gallagher, 2016). In this issue of Clinical Corner, I will share how this method is commonly used, demonstrate a variation of the procedure that may help you, compare it to other teaching methods, and tell you where to find more information.

Before you start teaching social skills, first choose the skills you will teach and develop an appropriate motivation system. While identifying the skills to learn is out of the scope of this article, it is perhaps more important than how you teach it! Teaching essential skills (that are appropriate to the student's level on the assessment, meaningful to the child and their environment, and open up new opportunities for them) is both extremely important and difficult at the same time. The process of learning in a group increases the complexity. For guidance on setting goals and assessing social skills, see Chapters 1 and 5 of Teaching Social Skills to People with Autism: Best Practices for Individual Intervention (Bondy and Weiss, 2013) by clicking here. Once the skills are chosen, set up a motivation system so that the children put in the best effort in practice. To do this, it is necessary to identify one or more favorite activities or subjects that each child would like to receive. Next, come up with a system of points or tokens that he can exchange for the selected reward. You can see how to do this effectively in the ASAT Intervention Summary. Once you've completed these steps, you're ready to start learning.

The following is a more detailed description of how the six steps of the learning interaction procedure work in practice. Examples are given that include teaching in the format of individual and group lessons for children of primary school and adolescence, both with an average and a higher level of social skills.

Step 1. Skill name and definition : Tell students what they will be learning. Give the skill a name that is descriptive and appropriate for the child's developmental level. Ask each child to tell what this skill is. It is very important that students actively respond. Therefore, each stage should include opportunities for responses. Don't let the procedure turn into a lecture!

| Examples | Teacher | Student(s) |

| Junior students Individually | “Susie, we will learn how to say hello to our friends. | "Say hello to friends!" |

| Teens In the classroom | Hello children! Today we will practice changing the topic of conversation. John, what are we going to learn today?” | "We will learn to change the subject of conversation." |

Stage 2 Skill and Prompt Need: Explain to the children why they need the skill being learned. The explanation should contain natural, significant for students, consequences of applying the skill. You could give an example and ask each child to give their own explanation. Describe the environment or landmarks that indicate the right moment to use this skill. Ask each student to share when they will use this skill.

| Examples | Teacher | Student(s) |

| Junior students Individually | “If you say hello to your friends, they will want to play with you. | "For them to play with me." |

| Junior students Individually | “You can say hello to Bobby when he comes to the water play table. Who will you say hello to? | "Bobby". |

| Teenagers in the classroom | “It is important to be able to change the topic of conversation correctly so that friends do not get tired of talking about the same thing and leave. Sarah, why do you think we need to change the subject?” | "So that my friends can also talk about whatever they want." |

| Teenagers in the classroom | “For example, I need to use this skill when I talk to my daughter about school so that she can talk about other topics that she is interested in. Jordan, when do you need to change the subject?" | "When I talk about myself for a long time." |

Stage 3 - Divide the skill into steps .

Before learning, divide a skill into a sequence of steps (usually 2 to 5). The number of steps should match the number of important elements of the skill being learned and be easy to remember. Tell the students about each step and ask them to say it in order.

| Examples | Teacher | Student(s) |

| Junior students Individually | “When you say 'hello' to a friend, look at her, smile and say 'hello' in a friendly voice. How do you say hello to your girlfriend? | "I'll look at her... I'll say hello in a friendly voice." |

| Teens In the classroom | “This is a good way to change the subject. First, wait for a pause. Second, use a transition phrase to link the old topic to the new one. A passphrase is a phrase like “By the way, oh…” or “That reminds me of…”, etc. Third, suggest a new topic. Fourth, observe your interlocutor to see if he is interested in a new topic. | “Um…wait for a pause, then say a passphrase. Start talking about a new topic and see what others are interested in” |

Step 4 - Skill Demonstration : Demonstrate the skill you are teaching.

Educational interactions often (but not always) show both right and wrong behavior so that children learn to distinguish between right and wrong responses. First, demonstrate the skill incorrectly by doing only some of the steps. Ask students to answer if everything was done correctly. Then ask the children to tell what went wrong and how to fix it. Show the correct behavior. You can demonstrate the skill with another adult, a specially trained peer, one of the students and, in some cases (depending on the skill itself), on your own.

| Examples | Teacher | Student(s) |

| Junior students Individually | “Look how I say hello to my friend Mrs. “Did I do everything right? What did I do wrong? | “No! You didn't smile and your voice wasn't sweet." |

| Junior students Individually | “That's right! How can I do it right?" | "You should smile and say in a sweet voice like this:" Hello! |

| Junior students Individually | “Well done! I'll try again. Tell me if I'm doing the right thing…” | |

| Teenagers Classroom | “Look how I change the subject. And tell me if I followed all four steps correctly. Sarah, you will be my partner. Let's talk about our favorite music and I'll change the subject." | Sarah: "Who is your favorite singer?" |

| Teenagers Classroom | Teacher: “I like the Beatles. | Sarah: "I like Taylor Swift." |

| Teenagers Classroom | Teacher: “Yesterday, while jogging, I lost my favorite headphones…” “Guys, how did I manage? On the count of three, thumbs up if I've completed all the steps and thumbs down if I haven't. One two Three!" | Pupils show thumbs down. |

| Teenagers Classroom | “Everyone thinks that she didn't do it. Right! What did I do wrong and how can I fix it? | "You didn't use a passphrase." |

| Teenagers Classroom | “That's right! I missed the passphrase. Who can invent it? | “Speaking of listening to music…” |

Stage 5 - Role Play: Give each student the opportunity to demonstrate the skill in a role play with you. Look for clues and hints that trigger the application of the skill being learned. Give feedback after the skill has been demonstrated by the students. Clarify what was done right and what mistakes were made. If there were mistakes, ask the children to try again. If mistakes are made the second time, it may be necessary to use a hint during the role-play to increase the chances of the children being successful on the third attempt.

| Examples | Teacher | Student(s) |

| Junior students Individually | “When Mrs. Smith comes into the room, show me how you say hello to her. (Mrs Smith comes in) | Susie looks at her, smiles and says "hello" in a joyful voice. |

| Junior students Individually | “Well done, Susie! You looked at Mrs Smith and said hello to her in a friendly voice. | |

| Teenagers Classroom | Now it's your turn to show the group how to change the subject. John, you start. | 0007 World of Warcraft ?” |

| Teenagers Classroom | With a pitiful look “No…” | “She's cool! What I like the most is the new equipment that I can use. There is one spell that can be cast…” |

| Teenagers Classroom | “Let's stop there. John, you said a great transitional phrase "by the way, about video games" and started a new topic that is relevant to the question asked. But you did not wait for a pause in the conversation, and also did not follow my face. You did not notice that I was not interested in a new topic. Try again". |

Stage 6 - Feedback and Reinforcement: It is desirable that throughout the procedure the student receives reinforcement (usually praise along with some other prize) for correct answers, and in case of errors - corrective feedback. Before starting training, determine the child's preferences and objects that can be used as reinforcement. Token or point systems are effective for this purpose. During the lesson, children receive points or tokens for correct answers (Steps 1-4) and correct use of the skill during the role-play (Step 5). At the end of the lesson, the students exchange them for a reward. The order of issuing tokens can be as follows: for the correct performance of the skill on the first attempt, give two tokens, on the second - one token, in case of a correct answer using the hint on the third attempt - praise. This will happen at every stage of the learning interaction procedure, not just at the end of the

Below is another example of a learning interaction procedure, also used in group sessions with elementary school students. This example includes a feedback/rewards process (tokens are issued throughout the process).

| Step | Teacher | Students |

| Step 1: Naming and defining the skill | “Today we will learn how to invite a friend to play a game. | (in unison) "Invite a friend to play a game!" |

| "That's right!" (give each student two tokens) | ||

| Step 2: Explain the need for the skill and environmental guidelines | “Why is it important to invite friends to play? Olive, what do you think?" | Olive : « I am not know ". |

| “Try to answer. Why would you want to invite a friend to play together?” | Olive: "That'll be more fun." | |

| "Yes, it's more fun!" (give Oliver 1 token for the correct answer on the second try, ask the rest of the children until each of them gives their own explanation). “When will you invite a friend to play? For example, you can invite a friend who is watching the game. | Levy: "I'm going to invite Cayden to play Square because I know he likes the game." | |

| “Great idea! I'm sure Cayden will be very happy!" (give Levi two tokens for the correct answer on the first try, ask the rest of the children) | ||

| Step 3: Skill division into steps | “You can invite a friend to play in the following way: first, find a person who might be interested. Choose a friend who is not currently playing something else. Second, approach him in a friendly way. It means to come up and smile. Third, tell what you are doing and ask if he would like to join. Fourth, if the friend agreed, tell them exactly how they can join the game, for example, say: "You can be on my team" or "You can draw with this marker." You had to memorize many steps. Let's try to say them all. Calvin, you begin." | Calvin: "Find a friend to play with and ask him if he wants to. |

| “You named two steps out of four! The two steps you missed: approach in a friendly way, and then tell how you can join. | Calvin: “Okay. Find a friend to play with, ask him to join, and tell him how to join" . | |

| “Nice try. You named three steps out of four. Try again and I'll help you remember when to approach in a friendly way." | Calvin: "Find a friend to play with..." | |

| Interrupts the student with the words "and come..." | “And approach in a friendly way. Ask to play together and tell how you can join. | |

| “You named all the steps! Great!" (do not give tokens because the child needed a hint to get the correct answer. Continue with the next student).” | ||

| Step 4: Skill Demonstration | “Now I will show you how to invite someone to play. | |

| “So, tell me, did I do everything right? What should have been done differently if a mistake was made? Olive?" | Olive: “Wrong. Mrs Smith was busy. You should have asked the other person." | |

| Great, Olive! (give Olive 2 tokens, and give each student a chance to answer). | ||

| Pitch 5: Role play | “Now it's your turn to invite a friend to play the game. Levy, you start playing Uno with the mission c Smith. | Levi sees you watching, comes up to you with a smile and asks if you want to play. When you say yes, he returns to the game. |

| “Well done, Levi! You did four steps correctly, but you forgot the last one. I needed help getting started. You could do it this way: give me some cards or tell me you're almost done and give me the cards in the next round." | Levi repeats the role play again, doing everything right. | |

| “Great! You followed all the steps correctly." (Give Levi one token and train the rest of the students) | ||

| Step 6: Feedback and Reinforcement | “You all did great! You've learned how to invite your friends to play the game! Be sure to practice again today during recess. Count your tokens and raise your hand if you want to exchange them. |

Follow these procedures until each student has mastered the skill being taught. This method can be adapted in future lessons. For example, after one or two lessons, ask students to independently determine the skill and explain its necessity. It usually takes 3 to 6 sessions to master a new skill. This parameter will vary depending on the level of development of students.

How do you know if a child has mastered a skill? One of the signs is the correct use of it the first time during a role-playing game. Even better, try without warning: create a situation outside of the group session in which it would be appropriate to apply this skill, and observe the actions of the child. In the case of the example of learning to change the subject, talk to a student at any time during the day and suddenly pretend to be bored. See if he changes the subject. In the case of the example of learning to say "hello", when the child is playing alone, suddenly come and sit next to him to see if he says hello.

Each student may progress at a different pace. It is important to make sure that each child gets enough practice. However, if the skill is not mastered by the student despite sufficient time to practice it, pay attention to the following points:

- Is the learning interaction procedure being applied correctly? Based on the steps listed in the article (or the links at the end of the article), you need to make a checklist and make sure that the teacher consistently completes all the steps of the procedure.

- Are there steps (skill items) that require more explicit description or detailed training? For example, the "decide if this person would be a good friend" step as part of the making friends skill would likely require a definition explaining who would make a good friend. It will also take more time to practice distinguishing between examples that correspond to the behavior of good and bad friends.

- Do students have the necessary prerequisite skills? As a rule, to get a good result, the child needs well-mastered basic speech skills (for example, using sentences in communication), and it may also require pre-learning certain steps (as in the previous example).

- Are students motivated enough to try hard? If not, pay attention to the reinforcement system. Make sure to use it consistently. Replace some rewards with more interesting ones. You can choose the most desired encouragement, which will be used only in lessons using the learning interaction method.

- The student does not apply the skill learned in the role play in real life. Read on.

Several steps have been added to one of the potentially successful variations of the procedure to allow generalization of the skill. That is, the child will use the learned skill not only in role play with the teacher, but also in real life situations (Kassardjian & Taubman, 2013). You can see if generalization is happening by observing the student in other settings and seeing if the skill is applied. You can also ask your child's parents if they use the skill outside of school. In order to use this option, minor changes should be made to Stage 5 and practice in real life conditions (generalization phases) should be added:

Step 5 - Role Play: Use a variety of realistic scenarios to role play. Use as many potential situations as possible, especially in which the child does not demonstrate this skill. Organize role-play with other children in such a way that they have the opportunity to interact with each other on a daily basis. For classes, you should choose materials that are usually used in the daily life of children. The role-play should be conducted in places where the skill is really needed. In the case of the example of teaching children to “invite friends to play something”, a role-play can be organized in the playground using real games.

Generalization. Phase 1 - Reminder, Praise, Reward: After the skill has been mastered by the students at the role-play level, situations should be created in which the new skill needs to be applied in a real life setting. For example, if this is one of the play skills, you can use recess or games during class. At the beginning of the exercise, remind the students to use the new skills. If the children are doing their actions correctly, praise and reinforce this.

Generalization. Phase 2 - Praise and Reward: Do not tell students to use the skill in a natural setting (same as in Phase 1). In case of correct performance, praise them and give encouragement.

Generalization. Phase 3 - Praise: Do not tell students to use the skill in a natural setting (same as in Phase 1). If performed correctly, only praise is used.

Generalization. Phase 4 - Autonomy: Create situations to demonstrate a skill without reminders or additional consequences. Now the students have to do everything in the natural environment on their own! Congratulations!

In addition to the method of learning interaction, there are other options for teaching social skills. And although there are many more, let's compare this method with "social stories" (Social Stories) and behavior skills training (Behavioral Skills Training).

Social stories ( Social Stories ): " Social stories" are stories, individual for each child, from which he learns information on social topics. At the moment, on the official website about this method, 10 signs are given, according to which "social history" can be considered as such. Social stories are a commonly used intervention method. Therefore, the researchers compared it with the learning interaction method to find out which one is more effective. In the first comparative study (Leaf et al., 2012), six children were taught six different skills, three skills using the learning interaction method and three others using the social stories method. According to the results obtained, using the learning interaction method, children mastered 18 skills out of 18 that they were taught. At the same time, students mastered only 4 of the 18 skills that they were taught with the help of "social stories". Although the comparison was made for applying both methods through individual learning, it was also replicated in a group learning setting (Kassardjian et al., 2014). In this study, the authors concluded that the learning interaction procedure was effective for all children, while the application of the "social stories" method did not lead to any improvements.

Therefore, they recommended using the method of learning interaction.

Behavioral Skills Training Behavioral Skills Behavior skills training has four components: instruction, skill demonstration, skill practice, and feedback. The main difference between the two methods is that the BST does not provide an explanation for the need to apply the skill. Another difference: in the case of learning interaction method, both correct and incorrect skill models are often shown in order to develop discernment skill. This stage implementation has been called Cool/Not Cool and has been shown to be effective on its own (Au et al., 2016). In the case of BST, only the correct response model is shown. After reviewing studies on behavioral skills training and learning interactions involving people with autism (Leaf et al., 2015), the authors of the article concluded that both methods have a sufficient evidence base and are effective.

If you are going to use the learning interaction method for teaching social skills, I recommend that you read the study guide with a detailed curriculum “Connected! Learning programs. Socialization of People with Autism Using Applied Behavioral Analysis” (Taubman M., Leaf R., MakEken J., edition in Russian: IP Tolkachev, 2018). The articles I referenced in this paper also provide examples of how the learning interaction method can be applied.

References:

- Au, A., Mountjoy, T., Leaf, J. B., Leaf, R., Taubman, M., McEachin, J., & Tsuji, K. (2016). Teaching social behavior to individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder using the cool versus not cool procedure in a small group instructional format. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 41(2), 115–124. doi:10.3109/13668250.2016.1149799

- Bondy, A., & Weiss, M. J. (2013). Teaching social skills to people with autism: Best practices in individualizing interventions (1st ed.

). Bethesda, MD: Woodbine House.

- Online download link for some chapters: https://pecsusa.com/downloadable-books/

- Kassardjian, A., Leaf, J. B., Ravid, D., Leaf, J. A., Alcalay, A., Dale, S., … Oppenheim-Leaf, M. L. (2014). Comparing the teaching interaction procedure to social stories: A replication study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(9), 2329–2340. doi:10.1007/s10803-014-2103-0

- Kassardjian, A., & Taubman, M. (2013). Utilizing teaching interactions to facilitate social skills in the natural environment. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 48(2), 245–257.

- Leaf, J. B., Dotson, W. H., Oppeneheim, M. L., Sheldon, J. B., & Sherman, J. A. (2010). The effectiveness of a group teaching interaction procedure for teaching social skills to young children with a pervasive developmental disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4(2), 186–198. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2009.09.003

- Leaf, J. B., Oppenheim-Leaf, M.

L., Call, N. A., Sheldon, J. B., Sherman, J. A., Taubman, M., ... Leaf, R. (2012). Comparing the teaching interaction procedure to social stories for people with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 45(2), 281–298. doi:10.1901/jaba.2012.45-281

- Leaf, J. B., Taubman, M., Bloomfield, S., Palos-Rafuse, L., Leaf, R., McEachin, J., & Oppenheim, M. L. (2009). Increasing social skills and pro-social behavior for three children diagnosed with autism through the use of a teaching package. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(1), 275–289. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2008.07.003

- Leaf, J. B., Townley-Cochran, D., Taubman, M., Cihon, J. H., Oppenheim-Leaf, M. L., Kassardjian, A., … Pentz, T. G. (2015). The Teaching Interaction Procedure and behavioral skills training for individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a review and commentary. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 2(4), 402–413. doi:10.1007/s40489-015-0060-y

- Taubman, M. T., Leaf, R. B.

, McEachin, J., & Driscoll, M. (2011). Crafting connections: Contemporary applied behavior analysis for enriching the social lives of persons with autism spectrum disorder. DRL Books.

- Tullis, C., & Gallagher, P. (2016). Effects of a group teaching interaction procedure on the social skills of students with autism spectrum disorders. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 51(4), 421–433.

- Citation for this article: Stoeckley, C. (2020). Clinical corner: What is a good way to teach social skills in a group? Science in Autism Treatment, 17(2).

Source: Link to the original article

Translators - Galina Chernobay, Yulia Tomilova.

We are in the social. networks

10 Rules for Success • Autism is

Appropriate and functional social and play skills are a big challenge for many children with autism. In order to ensure that your child succeeds when interacting with peers, it is important to consider the 10 recommendations below.

These rules apply to any social skills training program, but they can also be used by parents themselves to arrange meetings and games with peers in their homes. Of course, each social skills program should be individualized, depending on the strengths and needs of the individual child.

1. Identify the specific social skills you will be working on

The best way to select social skills for the program is to collect “baseline information”. Observe your child's social behavior with adults, with peers, and during independent play with toys in typical situations (for example, in the playground when another child is talking to him via video call, at home with a sibling, during a children's activity, etc.) .

What activities do children enjoy most when they are around other children? Can you think of a very small next goal for each of these activities? For example, teach a child to say “Hi” to other children and respond to their greeting? Or, if a child can say "Hi", how about if they can add the phrase "Let's play" and play the game on their tablet?

If a child can play on the tablet with another child, maybe he needs to learn to wait his turn while the other child plays? If so, how long does he need to learn to wait? Does he need to learn how to say "My turn" before taking the game for himself?

Make sure you understand what behavior is appropriate for your child's developmental level. It is important to expect from him what is the next step for this child personally, and not what children at this age are “supposed” to do (Chang & Shire, 2019).

Write a list of things the child often does on their own. Then make a list of potential "target skills" that he can be taught. Check the easiest and most basic skills that can be taught first. For example, it can be a greeting, just stay and play next to a peer, throw the ball several times with another child.

Once the simplest social skills are mastered, it will be possible to move on to more complex social skills (Barton et al., 2019). For example, it could be taking turns playing, adding new social phrases, engaging in a partially structured game, or playing by the rules.

Also note which activities and games the child enjoyed the most during the meeting with a peer. Choosing the most enjoyable activities for the child will allow him to develop his motivation for communicating with other children and a positive attitude towards joint games.

For strategies for teaching these minor social skills, it is best to consult a behavioral analyst, if possible. Perhaps, if you do not have the opportunity to hire a behavioral analyst in your area, you can find a behavioral specialist who consults and educates parents online.

It is best to find a specialist who can teach you the right strategies (parent education), who will take into account your child's strengths and preferences, and will find small steps to learn social skills that your child can regularly practice. A behavior analyst or other counselor can help you determine which target skills best suit your child's developmental level and whether other (prerequisite) skills need to be taught before moving on to teaching your chosen social skills.

2. Teach the target skills first with another adult

Make sure the child has plenty of opportunities to learn the target social skills with an adult. Only then can you arrange a meeting for him with a peer with whom he can try the same skills. As a general rule, social skills training always starts with a “lose” with an adult who knows the child’s education program and understands what to look for. An adult will be more predictable when interacting, he will encourage the desired reactions of the child and will adapt more to him than a peer.

It is recommended that the adult who teaches the child should not act out social situations with the child himself, but, if possible, involve a second adult. For example, one parent teaches a child how to play with the other parent. The second parent plays the role of a peer and tries to behave during the game as a peer will behave.

In this case, the "training" adult will provide prompts and encouragement. And it will be enough for the second “substitute peer” adult to model the behavior characteristic of other children. Teaching with a team of two adults will be more effective for the child, as he will expect more natural behavior from communication partners.

Moreover, you can involve different adults in "training" games and communication. This will help to maintain and generalize the skills as the child gets used to showing them to different people.