Socialization skills for preschoolers

5 Ways to Build Social Skills

Teachers share with us all the time that in addition to learning ABCs and 123s, helping little ones develop healthy social skills in preschool is a big contributor to becoming successful students as the elementary school years unfold. Parents play a key role in helping their children build early social and sharing skills at home each and every day.

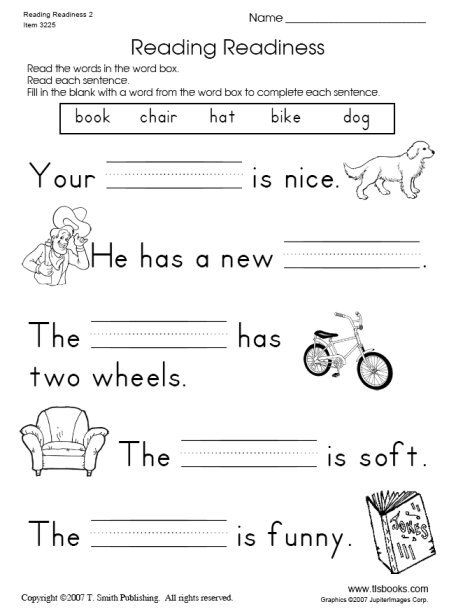

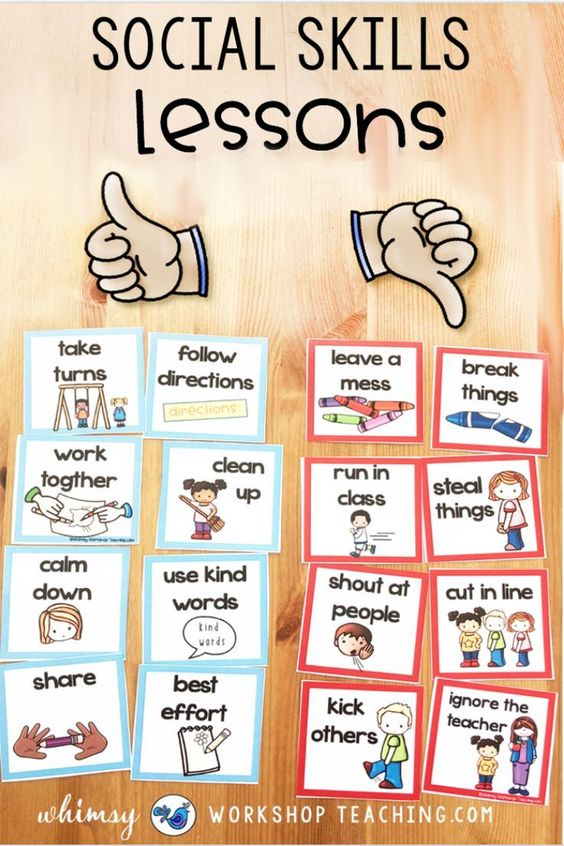

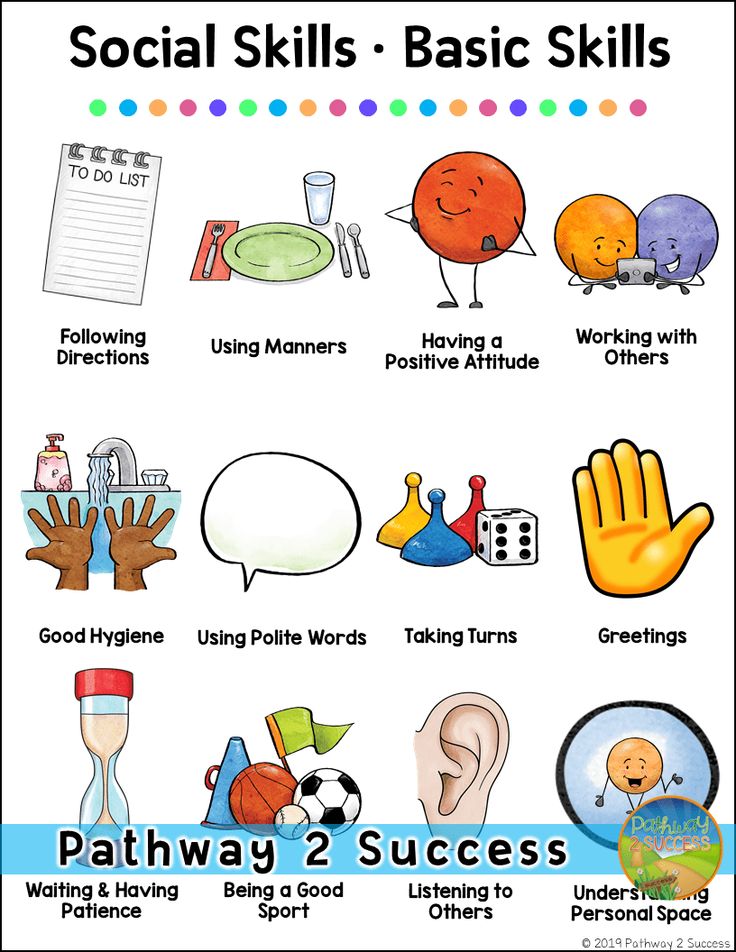

In preschool, children will learn how to share and cooperate, to work together and take turns, to participate in group activities, to follow simple directions, and to communicate wants and needs. Knowing how to do these things builds self-esteem and confidence and helps children thrive in group settings – both in school and out.

Here are 5 simple ways you can help to develop and strengthen your child's social skills outside the classroom:

- Arrange play dates, and go to play groups and to the playground. Giving kids the opportunity to engage with other children frequently will provide them with lots of opportunities to take turns, share, and play together.

- Give your preschooler simple responsibilities like helping you to set the table for dinner or simple cleaning and tidying. These activities are also very empowering for little ones and help build their confidence.

- At home, be consistent about simple rules your child must follow, such as making the bed or putting her toys away.

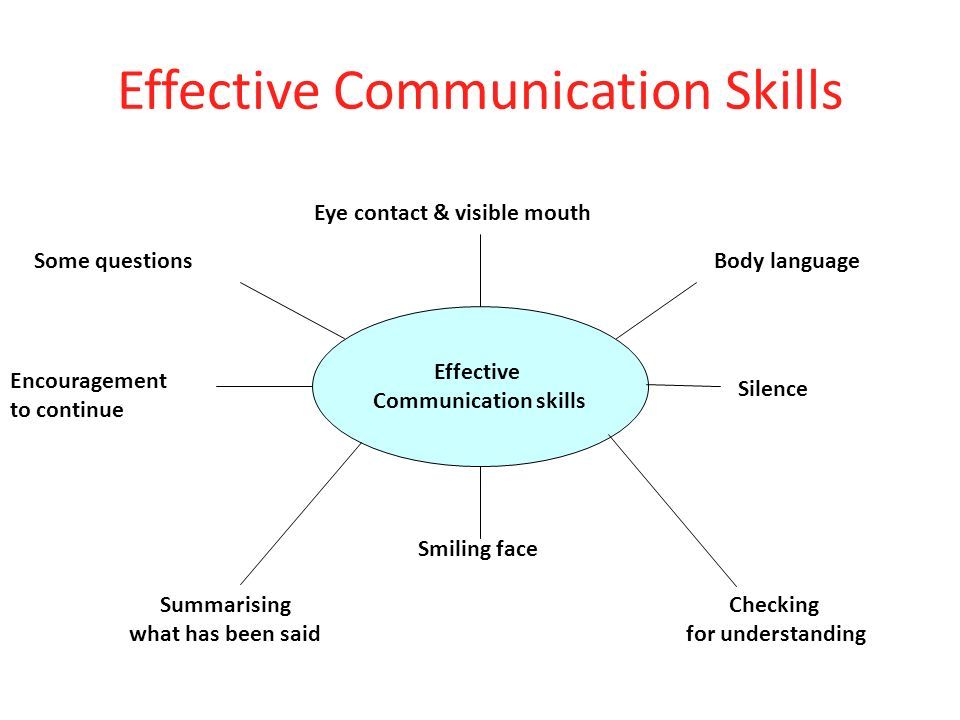

- Model appropriate social interaction and politeness, help them to remember "please" and "thank you" in appropriate moments/settings, and model behavior and language that shows them how to share, wait their turn, and work with others. Playing board games together and taking turns talking about your day at dinner time are two great ways to begin teaching little ones how to take turns.

- Help your child learn how to express his emotions, understand them, and learn self-control. In preschool, your little one will rely on his own words and actions to express his needs to his teachers and classmates on a daily basis and sometimes emotions can be big and scary.

Help your child realize and understand his own emotions – feeling sad, mad, happy, excited -- and talk to him about what makes him feel that way. Provide him with ideas on how to best communicate those feelings with others.

Help your child realize and understand his own emotions – feeling sad, mad, happy, excited -- and talk to him about what makes him feel that way. Provide him with ideas on how to best communicate those feelings with others.

In addition to you modeling healthy ways to express emotions at home, reading books together about characters who are learning about their emotions and talking with your child about the characters' actions is another great way to help your little one begin to understand his own emotions. Ask questions like, "What did the character do to help her communicate how she was feeling?" or "Why do you think she felt angry/sad/upset?" and " What would you do/say if you felt this way?

Some favorite stories that speak to feelings and emotions and are perfect for preschoolers include:

- When Sophie Gets Angry – Really, Really Angry by Molly Bang

- Sometimes I'm Bombaloo by Rachel Vail

- Wemberly Worried by Kevin Henkes

- The Pigeon Has Feelings, Too! by Mo Willems

- My Friend Is Sad (an Elephant and Piggie book) by Mo Willems

- The Feelings Book by Todd Parr

- How Do Dinosaurs Say I'M MAD! by Jane Yolen

How do you help your little one learn to share, cooperate, communicate, and participate? We'd love to know.

Share your ideas with us on the Scholastic Parents Facebook page and let's continue the conversation!

Featured Book

learn more

GRADES

Social Development in Preschoolers - HealthyChildren.org

During your child's preschool-age years, they'll discover a lot about themselves and interacting with people around them.

Once they reach age three, your child will be much less selfish than they were before. They'll also be less dependent on you, a sign that their own sense of identity is stronger and more secure. Now they'll actually play with other children, interacting instead of just playing side by side. In the process, they'll recognize that not everyone thinks exactly as they do and that each of their playmates has many unique qualities, some attractive and some not. You'll also find your child drifting toward certain kids and starting to develop friendships with them. As they create these friendships, children discover that they, too, each have special qualities that make them likable—a revelation that gives a vital boost to self-esteem.

There's some more good news about your child's development at this age: As they become more aware of and sensitive to the feelings and actions of others, they'll gradually stop competing and will learn to cooperate when playing with her friends. They take turns and share toys in small groups, though sometimes they won't. But instead of grabbing, whining, or screaming for something, they'll actually ask politely much of the time. You can look forward to less aggressive behavior and calmer play sessions. Three-year-olds are able to work out solutions to disputes by taking turns or trading toys.

Learning how to cooperate

However, particularly in the beginning, you'll need to encourage this cooperation. For instance, you might suggest that they "use their words" to deal with problems instead of acting out. Also, remind them that when two children are sharing a toy, each gets an equal turn. Suggest ways to reach a simple solution when your child and another child want the same toy, such as drawing for the first turn or finding another toy or activity. This doesn't work all the time, but it's worth a try. Also, help children with the appropriate words to describe their feelings and desires so that they don't feel frustrated. Above all, show by your own example how to cope peacefully with conflicts. If you have an explosive temper, try to tone down your reactions in their presence. Otherwise, they'll mimic your behavior whenever they're under stress.

This doesn't work all the time, but it's worth a try. Also, help children with the appropriate words to describe their feelings and desires so that they don't feel frustrated. Above all, show by your own example how to cope peacefully with conflicts. If you have an explosive temper, try to tone down your reactions in their presence. Otherwise, they'll mimic your behavior whenever they're under stress.

When anger or frustration gets physical

No matter what you do, however, there probably will be times when your child's anger or frustration becomes physical. When that happens, restrain them from hurting others, and if they don't calm down quickly, move them away from the other children. Talk to them about her feelings and try to determine why they're so upset. Let them know you understand and accept her feelings, but make it clear that physically attacking another child is not a good way to express these emotions.

Saying sorry

Help them see the situation from the other child's point of view by reminding them of a time when someone hit or screamed at them, and then suggest more peaceful ways to resolve their conflicts. Finally, once they understand what they've done wrong—but not before—ask them to apologize to the other child. However, simply saying "I'm sorry" may not help your child correct their behavior; they also needs to know why they're apologizing. They may not understand right away, but give it time; by age four these explanations will begin to mean something.

Finally, once they understand what they've done wrong—but not before—ask them to apologize to the other child. However, simply saying "I'm sorry" may not help your child correct their behavior; they also needs to know why they're apologizing. They may not understand right away, but give it time; by age four these explanations will begin to mean something.

Make-believe play

Fortunately, the normal interests of three-year-olds keep fights to a minimum. They spend much of their playtime in fantasy activity, which tends to be more cooperative than play that's focused on toys or games. As you've probably already seen, preschooler enjoy assigning different roles in an elaborate game of make-believe using imaginary or household objects. This type of play helps develop important social skills, such as taking turns, paying attention, communicating (through actions and expressions as well as words), and responding to one another's actions. And there's still another benefit: Because pretend play allows children to slip into any role they wish—including superheroes or the fairy godmother—it also helps them explore more complex social ideas. Plus it helps improve executive functioning such as problem-solving

Plus it helps improve executive functioning such as problem-solving

By watching the role-playing in your child's make-believe games, you may see that they're beginning to identify their own gender and gender identity. While playing house, boys naturally will adopt the father's role and girls the mother's, reflecting whatever they've noticed in the hemworld around them.

Development of gender roles & identity

Research shows that a few of the developmental and behavioral differences that typically distinguish boys from girls are biologically determined. Most gender-related characteristics at this age are more likely to be shaped by culture and family. Your daughter, for example, may be encouraged to play with dolls by advertisements, gifts from well-meaning relatives, and the approving comments of adults and other children. Boys, meanwhile, may be guided away from dolls in favor of more rough-and-tumble games and sports. Children sense the approval and disapproval and adjust their behavior accordingly. Thus, by the time they enter kindergarten, children's gender identities are often well established.

Thus, by the time they enter kindergarten, children's gender identities are often well established.

As children start to think in categories, they often understand the boundaries of these labels without understanding that boundaries can be flexible; children this age often will take this identification process to an extreme. Girls may insist on wearing dresses, nail polish, and makeup to school or to the playground. Boys may swagger, be overly assertive, and carry their favorite ball, bat, or truck everywhere.

On the other hand, some girls and boys reject these stereotypical expressions of gender identity, preferring to choose toys, playmates, interests, mannerisms, and hairstyles that are more often associated with the opposite sex. These children are sometimes called gender expansive, gender variant, gender nonconforming, gender creative, or gender atypical. Among these gender expansive children are some who may come to feel that their deep inner sense of being female or male—their gender identity—is the opposite of their biologic sex, somewhere in between male and female, or another gender; these children are sometimes called transgender.

Given that many three-year-old children are doubling down on gender stereotypes, this can be an age in which a gender-expansive child stands out from the crowd. These children are normal and healthy, but it can be difficult for parents to navigate their child's expression and identity if it is different from their expectations or the expectations of those around them.

Experimenting with gender attitudes & behaviors

As children develop their own identity during these early years, they're bound to experiment with attitudes and behaviors of both sexes. There's rarely reason to discourage such impulses, except when the child is resisting or rejecting strongly established cultural standards. If your son wanted to wear dresses every day or your daughter only wants to wear sport shorts like her big brother, allow the phase to pass unless it is inappropriate for a specific event. If the child persists, however, or seems unusually upset about their gender, discuss the issue with your pediatrician.

Your child also may imitate certain types of behavior that adults consider sexual, such as flirting. Children this age have no mature sexual intentions, though; they mimic these mannerisms. If the imitation of sexual behavior is explicit, though, they may have been personally exposed to sexual acts. You should discuss this with your pediatrician, as it could be a sign of sexual abuse or the influence of inappropriate media or videogames.

Play sessions: helping your child make friends

By age four, your child should have an active social life filled with friends, and they may even have a "best friend." Ideally, they'll have neighborhood and preschool friends they see routinely. But what if your child is not enrolled in preschool and doesn't live near other children the same age? In these cases, you might arrange play sessions with other preschoolers. Parks, playgrounds, and preschool activity programs all provide excellent opportunities to meet other children.

Once your preschooler has found playmates they seems to enjoy, you need to take initiative to help build their relationships. Encourage them to invite these friends to your home. It's important for your child to "show off" their home, family, and possessions to other children. This will establish a sense of self-pride. Incidentally, to generate this pride, their home needn't be luxurious or filled with expensive toys; it needs only be warm and welcoming.

Encourage them to invite these friends to your home. It's important for your child to "show off" their home, family, and possessions to other children. This will establish a sense of self-pride. Incidentally, to generate this pride, their home needn't be luxurious or filled with expensive toys; it needs only be warm and welcoming.

It's also important to recognize that at this age your child's friends are not just playmates. They also actively influence their thinking and behavior. They'll desperately want to be just like them, even when they break rules and standards you've taught them rrm birth. They now realize there are other values and opinions besides yours, and they may test this new discovery by demanding things you've never allowed him—certain toys, foods, clothing, or permission to watch certain TV programs.

Testing limits

Don't despair if your child's relationship with you changes dramatically in light of these new friendships. They may be rude to you for the first time in their life. Hard as it may be to accept, this sassiness actually is a positive sign that they're learning to challenge authority and test their independence. Once again, deal with it by expressing disapproval, and possibly discussing with them what they really mean or feel. If you react emotionally, you'll encourage continued bad behavior. If the subdued approach doesn't work and they persist in talking back to you, a time-out (or time-in) is the most effective form of punishment.

Hard as it may be to accept, this sassiness actually is a positive sign that they're learning to challenge authority and test their independence. Once again, deal with it by expressing disapproval, and possibly discussing with them what they really mean or feel. If you react emotionally, you'll encourage continued bad behavior. If the subdued approach doesn't work and they persist in talking back to you, a time-out (or time-in) is the most effective form of punishment.

Bear in mind that even though your child is exploring the concepts of good and bad, they still have an extremely simplified sense of morality. When they obey rules rigidly, it's not necessarily because they understand them, but more likely because they wants to avoid punishment. In their mind, consequences count but not intentions. When theybreaks something of value, they'll probably assume they are bad, even if they didn't brea it on purpose. They need to be taught the difference between accidents and misbehaving.

Separate the child from their behavior

To help them learn this difference, you need to separate them from their behavior. When they do or say something that calls for punishment, make sure they understand they are being punished for the act not because they're "bad." Describe specifically what they did wrong, clearly separating person from behavior. If they are picking on a younger sibling, explain why it is wrong rather than saying "You're bad." When they do something wrong without meaning to, comfort them and say you understand it was unintentional. Try not to get upset, or they'll think you're angry at them rather than about what they did.

When they do or say something that calls for punishment, make sure they understand they are being punished for the act not because they're "bad." Describe specifically what they did wrong, clearly separating person from behavior. If they are picking on a younger sibling, explain why it is wrong rather than saying "You're bad." When they do something wrong without meaning to, comfort them and say you understand it was unintentional. Try not to get upset, or they'll think you're angry at them rather than about what they did.

It's also important to give your preschooler tasks that you know they can do and then praise them when they do them well. They are ready for simple responsibilities, such as setting the table or cleaning their room. On family outings, explain that you expect them to behave well, and congratulate them when they do. Along with responsibilities, give them ample opportunities to play with other children, and tell him how proud you are when they shares or is helpful to another child.

Sibling relationships

Finally, it's important to recognize that the relationship with older siblings can be particularly challenging, especially if the sibling is three to four years older. Often your four-year-old is eager to do everything their older sibling is doing; just as often, your older child resents the intrusion. They may resent the intrusion on their space, their friends, their more daring and busy pace, and especially their room and things. You often become the mediator of these squabbles. It's important to seek middle ground. Allow your older child their own time, independence, and private activities and space; but also foster cooperative play appropriate. Family vacations are great opportunities to enhance the positives of their relationship and at the same time give each their own activity and special time.

The information contained on this Web site should not be used as a substitute for the medical care and advice of your pediatrician. There may be variations in treatment that your pediatrician may recommend based on individual facts and circumstances.

There may be variations in treatment that your pediatrician may recommend based on individual facts and circumstances.

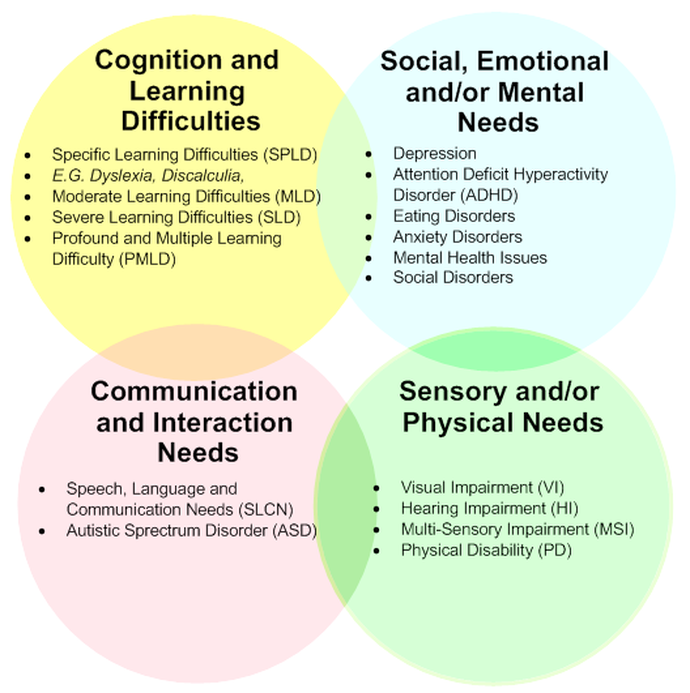

6 skills of successful socialization that a child will not receive in school and kindergarten

Socialization, socialization. Parents in recent years rush about with her like mad. Socialization is needed so that the child learns to behave correctly in society and maintain social contacts. Some parents shift it to institutions such as kindergarten and school. It is understood that it is from their peers that the child acquires such valuable skills. This is wrong. I will tell you why it is in the family that a child learns to build relationships and masters the only effective way to communicate “I am OK. You are OK."

1.

Understanding the boundaries of oneself and another person "The freedom of one person ends where the freedom of another begins." A capacious phrase with which many agree, but its application in practice causes difficulties. If a child does not clean his room, and we strongly insist on this, is this a violation of his boundaries or upholding ours? We need order in the house. If a child experiments with clothes and wears absolutely incompatible things in your opinion, should he make comments? How then to instill in him a sense of beauty? If we don't like a teenager's friends and try to protect him from bad influences, is this a violation of boundaries or concern for others?

If a child does not clean his room, and we strongly insist on this, is this a violation of his boundaries or upholding ours? We need order in the house. If a child experiments with clothes and wears absolutely incompatible things in your opinion, should he make comments? How then to instill in him a sense of beauty? If we don't like a teenager's friends and try to protect him from bad influences, is this a violation of boundaries or concern for others?

To answer these questions correctly, we put ourselves in the place of a child. Are we going to change something in our room, buy different clothes and look for new friends, because someone close to us doesn't like it? If your answer is "no", then you do not need to demand this from the child. It is to demand. It will be a violation of his boundaries. If your answer is yes, then you yourself first need to decide on an understanding of boundaries. Check if co-dependent relationships have leaked into your family.

Kindergarten and school will not help a child acquire this skill. Moreover, the system, on the contrary, merges the boundaries of one personality with others. Like it or not, the child wakes up early in the morning instead of sleeping. Teaches subjects that he does not want to learn. Communicates with peers with whom he has nothing in common. How can you understand the place of your desires in the system? Therefore, it remains either to abandon the kindergarten, transfer to SO, or raise awareness in the child, for which he does this. Internal restrictions do not break boundaries, unlike external ones.

Moreover, the system, on the contrary, merges the boundaries of one personality with others. Like it or not, the child wakes up early in the morning instead of sleeping. Teaches subjects that he does not want to learn. Communicates with peers with whom he has nothing in common. How can you understand the place of your desires in the system? Therefore, it remains either to abandon the kindergarten, transfer to SO, or raise awareness in the child, for which he does this. Internal restrictions do not break boundaries, unlike external ones.

2.

Understanding one's needsAbility to find them behind desires. A child wants a new toy every day - this is desire. Most likely, behind this is the need for attention from adults. The child does not want to go to school. Perhaps he has accumulated fatigue, and behind this desire is the need for rest. Or maybe he doesn’t have relationships in the class. Then it is the need to be accepted among your peers.

Can you imagine a situation in which the teacher asks: “Petya Ivanov, why didn’t you do your homework? Maybe you don’t understand the topic, or something happened in the family?” Perhaps there are such teachers, but not in classes of 30 people and with a load of eight lessons a day.

If we are attentive to our children and help them understand their true needs, they learn from us. Building their social relationships in the future, it will be easier for them to understand another person. What is important to both of us is what unites us.

3.

The ability to say "no"Our children do not say "no" to us because they have learned to say no. We just got them. We have lost their attachment to us, and they no longer want to listen to us. But they became attached to their peers. They begin to copy their behavior patterns.

Kindergarten is inevitable. The lack of critical thinking does not divide the actions of peers into good or bad. It is simply important for a child to be with someone. In adolescence, personal desires are added.

If there was no “no” practice in the family, peers will not hear this “no” either. It's not about the fact that "everyone tries and I want to." It's about the fact that if I don't want, I don't like it, I can refuse

"No, I don't want to run around abandoned garages with everyone else. " "No, I'm not going to steal for fun." "No, I don't want to participate in bullying." The ability not to merge with others, but to remain true to yourself and your interests. The fourth point follows smoothly from this.

" "No, I'm not going to steal for fun." "No, I don't want to participate in bullying." The ability not to merge with others, but to remain true to yourself and your interests. The fourth point follows smoothly from this.

4.

First me, then the othersAnd this is not about egocentrism. It's about resources and their use. "I won't give up my last shirt because I'll be left with nothing." “I don’t want to hear about your problems right now, because I won’t be able to support. I need help right now."

The ability to stop in time and not give yourself away saves you from burnout, overload and other stressful situations. Living on the edge is not the norm. The norm, when I took care of myself, and from a state of well-being I want and can take care of others. In relation to school, I can’t imagine how you can get this skill.

5.

Do not compare yourself with others You will either remain a loser forever, or vice versa, you risk becoming arrogant. At school, five people wrote an essay with "excellent", eight with "good", one person got a deuce. The rest have three. At home: “Last time you got a three for your essay, and this time a four. It is clear that you have worked." Or “Always fives, and today three. Something happened? Do you need help?"

At school, five people wrote an essay with "excellent", eight with "good", one person got a deuce. The rest have three. At home: “Last time you got a three for your essay, and this time a four. It is clear that you have worked." Or “Always fives, and today three. Something happened? Do you need help?"

Comparing yourself today with yourself yesterday, you can evaluate your coefficient of effort or level of ability. Gives an understanding of one's own value and makes one independent of the assessments of others. Works in reverse as well. "I'm fine - You're fine."

6.

Empathy as a counterbalance to total devaluation"What's the problem with doing homework? It's simple though." “Yes, you spit, you will have new friends!”.

School does not have the task of raising successful people. Only the educated. We make our children successful ourselves

Empathy is necessary for communication so that the interlocutor feels that he is understood. He is important. His problems and joys are not nonsense. Support your child properly and he will learn to do it himself.

His problems and joys are not nonsense. Support your child properly and he will learn to do it himself.

Socialization skills in preschool children

2020 has shown us that communication is very important. Not only outside, but also on the scale of one apartment.

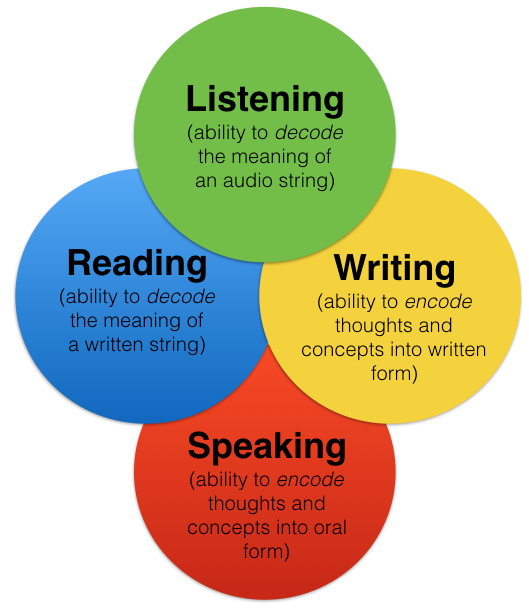

First of all, you need to understand that communication is a skill of effective communication. This is the ease in establishing contact, maintaining a conversation, the ability to negotiate and defend one's interests.

Every parent asks the question "when and how to socialize a child?" and “is it possible to compensate for communication skills at home without going to kindergarten?”

Let's figure it out. A child's communication begins at birth. The newborn "reads" the behavior and reactions of the parents. It adapts to them and shows its desires with its behavior. At this age, the only tool a child has is crying. With tears, the child conveys to the parent all his desires, worries, attracts attention. With age, more and more tools for communication appear and the range of interests of the child expands. Of course, a child should receive a number of skills at home. Namely: what is the "correct" way of life should be in the family. How relationships are built between its members, what kind of hierarchy is in the house, the appropriateness of behavior and reactions to situations. This is all the child will embody, including in adulthood. And here it is important to understand the possible consequences of the actions of parents in relation to children or in general in the family. For example, consider several situations.

With age, more and more tools for communication appear and the range of interests of the child expands. Of course, a child should receive a number of skills at home. Namely: what is the "correct" way of life should be in the family. How relationships are built between its members, what kind of hierarchy is in the house, the appropriateness of behavior and reactions to situations. This is all the child will embody, including in adulthood. And here it is important to understand the possible consequences of the actions of parents in relation to children or in general in the family. For example, consider several situations.

- If you overly admire the actions of a child and indulge all whims, then this can lead to the fact that he will grow up pampered and capricious, will painfully perceive the lack of adoration from other people;

- If a child is taught that it is important to observe only outward decorum, then in the future he may grow up to be a hypocrite;

- If a child is constantly punished for every wrongdoing or disobedience, then this can lead to a self-perception "I am a difficult child";

- If the child's desire to help ignore or praise someone else, then this can become the basis for the development of envy and self-doubt;

But let's assume that the parents do not make possible mistakes. Will parents, especially in the context of a pandemic and confined spaces, be able to replace their child's communication with a peer and harmoniously develop communication skills?

Will parents, especially in the context of a pandemic and confined spaces, be able to replace their child's communication with a peer and harmoniously develop communication skills?

What a child learns in communication:

-

Introduce yourself and get to know each other. But how will he learn this with the parents he has known all his life?

-

Negotiate and play together. How do parents model possible situations and reactions of other children? And even if we imagine that at some point the mother will begin to play the situation, for example, a greedy boy or a bully boy, will the child be able to correctly understand why his beloved mother offends him?

-

Explain exactly what the child needs and why. Everything is a little simpler here, but just like in the previous case, not all situations can be modeled by parents and show the whole range of possible reactions of their peers.

Let's look at the most popular qualities that parents want to see in their children:

-

Leadership. The child must learn to take responsibility for the decisions he makes and the people around him. For example, if no one wants to play, it should not be difficult for the child to suggest or organize the game himself. If all the time parents organize games or solve all problems, then the child will be passive. Of course, a child can try to involve his parents in the game, try to show himself, but adults always have a lot of worries, household chores or remote work, and they are not up to games. Then the child becomes invisible to himself.

-

Work in a group or team. Having learned to work in a group, the child will not be afraid to follow the rules of the game, accept his role and enjoy it. The family is certainly also a group, but a group with already formed rules.

A family cannot be different every day - this would lead to a violation of the family model itself.

A family cannot be different every day - this would lead to a violation of the family model itself. -

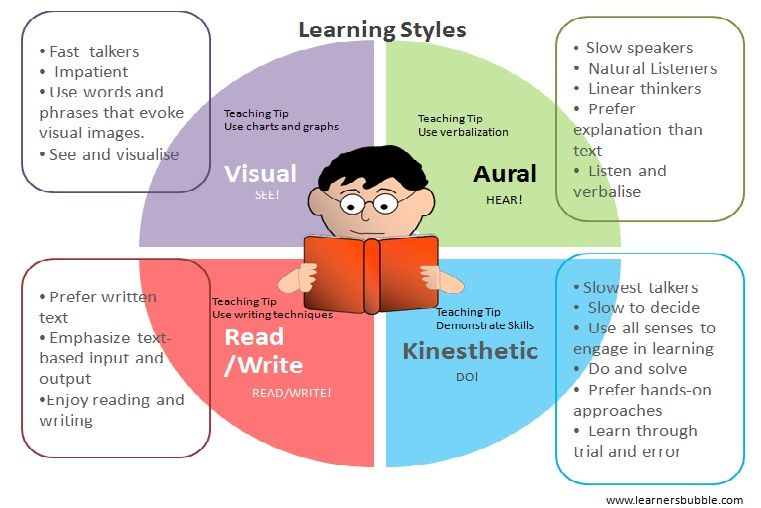

Emotional intelligence. This skill helps to manage your emotions, avoid neurosis, depression and apathy in time. The spectrum of emotions is wide, and all of them are important: both positive and negative. It is also important to feel them in the right dosage and in the right situational conditions. Will parents be able to correctly model situations and predict how the child will react to them. And keep the line so as not to turn the life of a child into a theater.

There have always been and will always be parents who are against socialization through preschool institutions. They believe that 30-60 minutes of “dosed” society per day in the form of developmental or sports sections is enough for a child to form communication skills. But they do not take into account that children are subject at that moment to the rules of the lesson or the purpose of the lesson and do not have the opportunity for free communication and the exchange of personal experience.