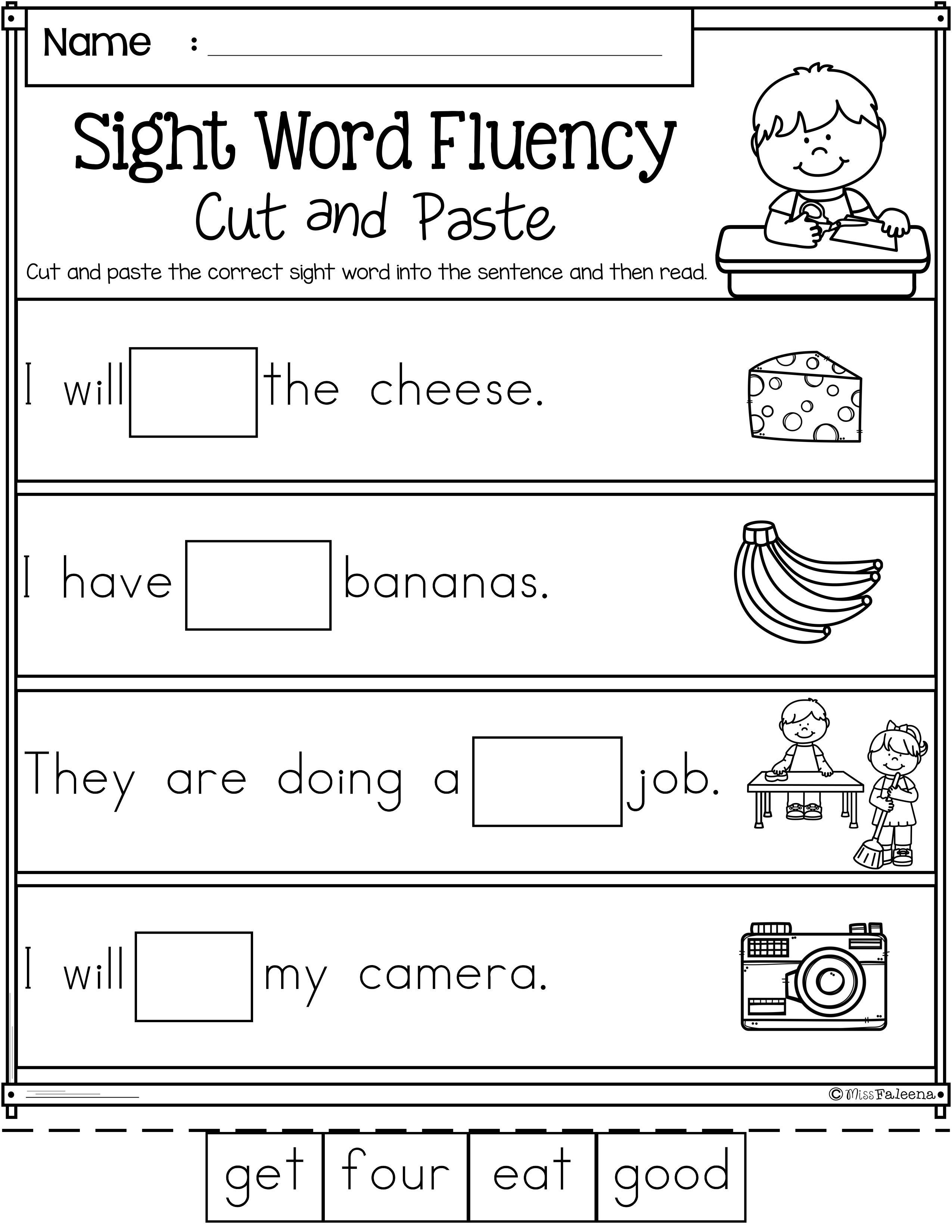

Sight word get

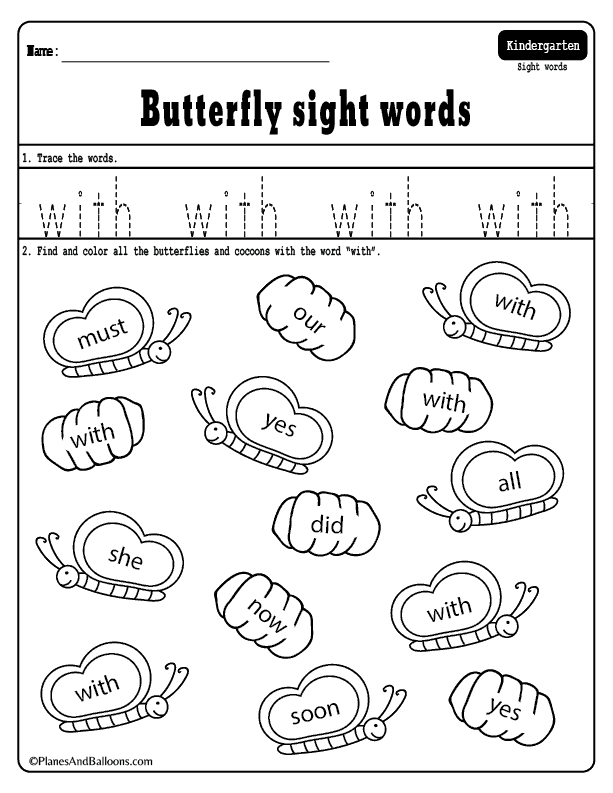

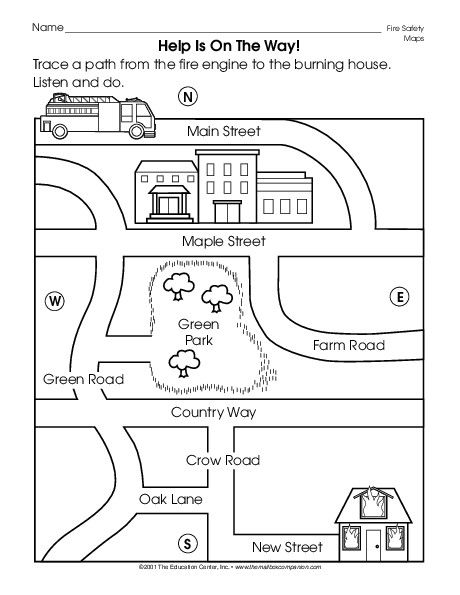

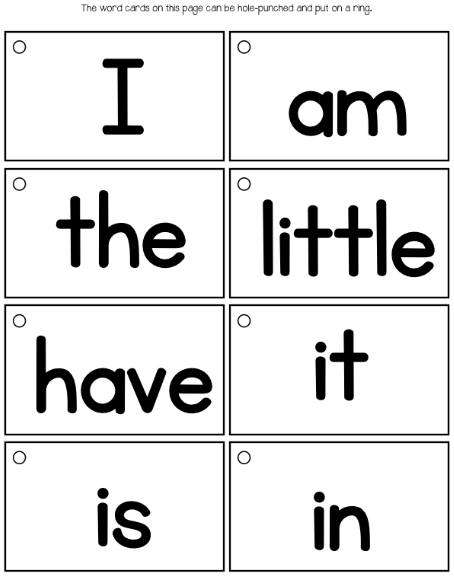

How to teach sight words

This post contains affiliate links. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases.

I receive many emails from teachers and parents asking me how to teach sight words.

Are you here to learn how to teach high frequency words? You’re in the right place!

What are sight words?

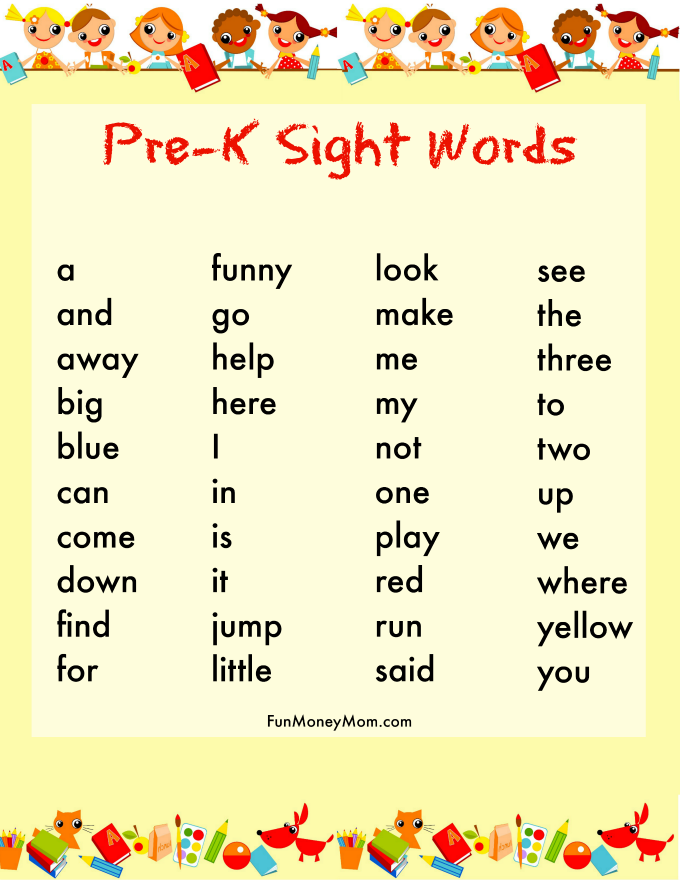

Traditionally, when teachers say “sight words,” they are referring to high frequency words that children should know by sight.

We often define sight words as words that kids can’t sound out – words like the, for example.

However, reading researchers have a different definition of sight words.

A sight word is a word that is instantly and effortlessly recalled from memory, regardless of whether it is phonically regular or irregular. A sight-word vocabulary refers to the pool of words a student can effortlessly recognize.

David A. Kilpatrick, PhD

So should we get lists of sight words and get our students to memorize them using flash cards?

Not so fast.

This doesn’t fit with how the brain learns to read.

We are not trying to get students to cram pictures of words in their brains, because there’s a limit to how many words any of us can remember by sight.

How does the brain learn “sight words”?

Researchers have discovered that strong readers do not call upon thousands of pictures of words in their brains. Instead, they (very, very quickly) connect the letters to the sounds in each word. They do this so quickly and effortlessly that it takes a tiny fraction of a second to identify each word.

How?

How do we move from sounding out words letter by letter, to recognizing thousands and thousands of words instantly?

It’s through a mental process called orthographic mapping.

Say what?

Stick with me … I promise it’s not as complicated as it sounds.

Orthographic mapping is the process we use to store printed words in long-term memory.

David A. Kilpatrick, PhD

In order for us to read words and then store them for future retrieval, we must be able to match the phonemes (sounds) to the graphemes (letters).

Does that sound familiar to you?

It’s phonemic awareness and phonics.

We need to teach children to identify individual sounds in words and then connect those sounds to letters. We teach them to sound out words, even sight words.

What about sight words that aren’t regular, like

the?We call attention to the parts of the word that are phonetic (and there’s usually at least 1-2 of them). Then we teach learners to learn the tricky parts by heart.

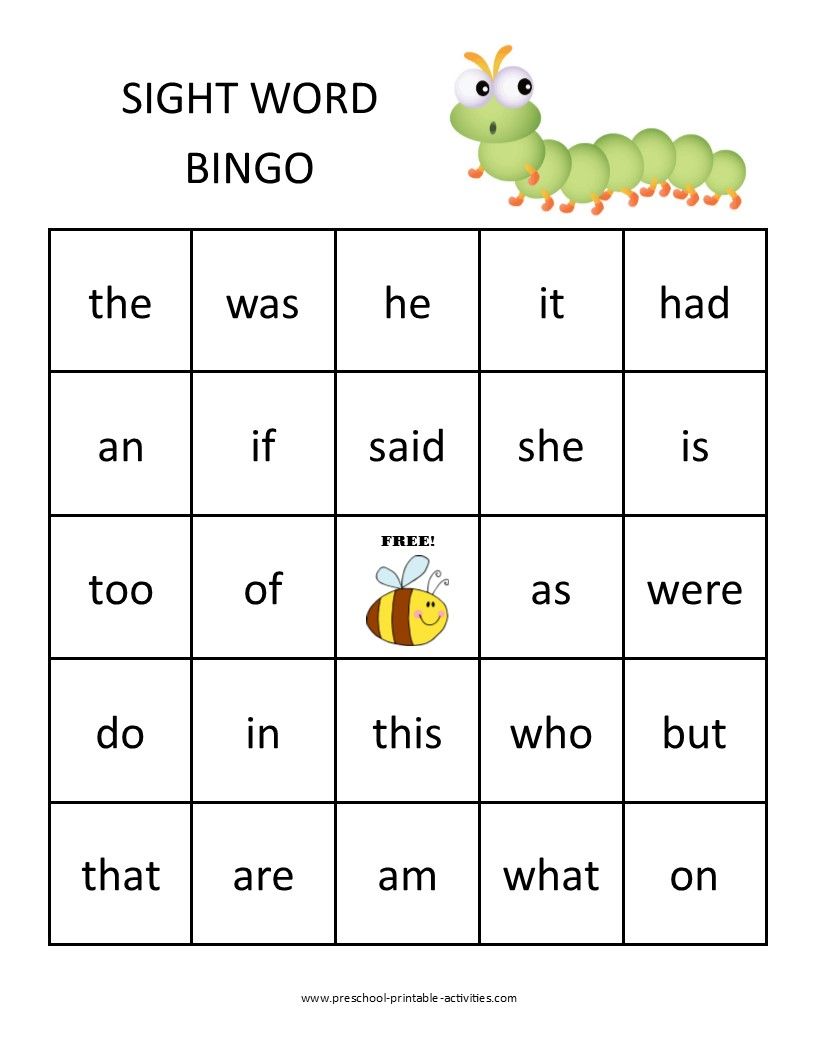

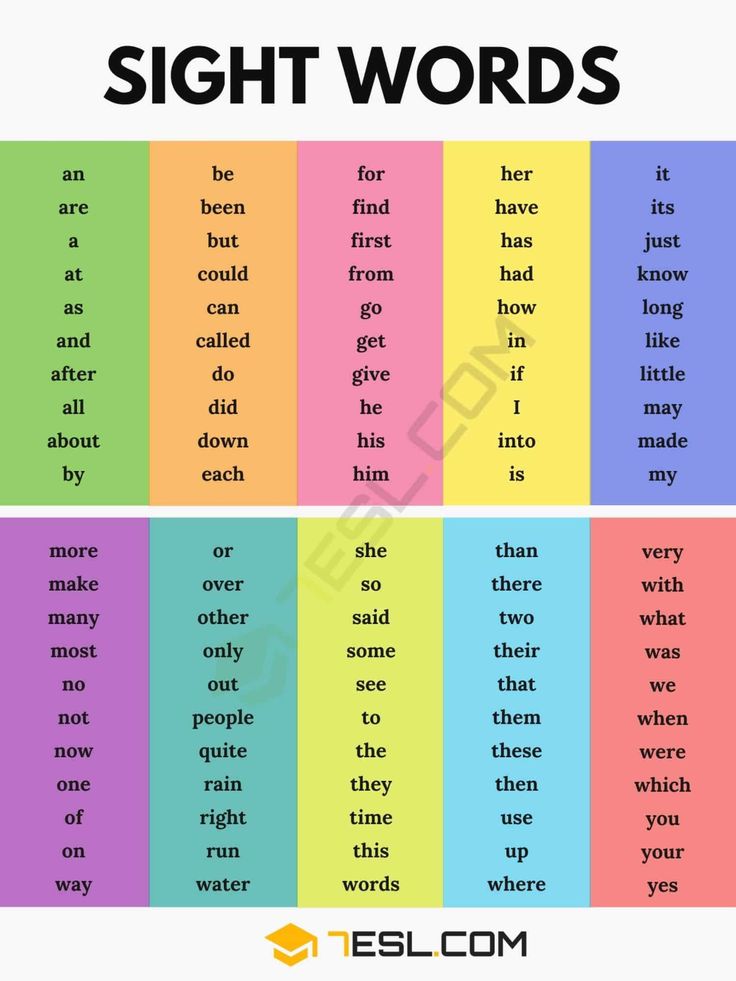

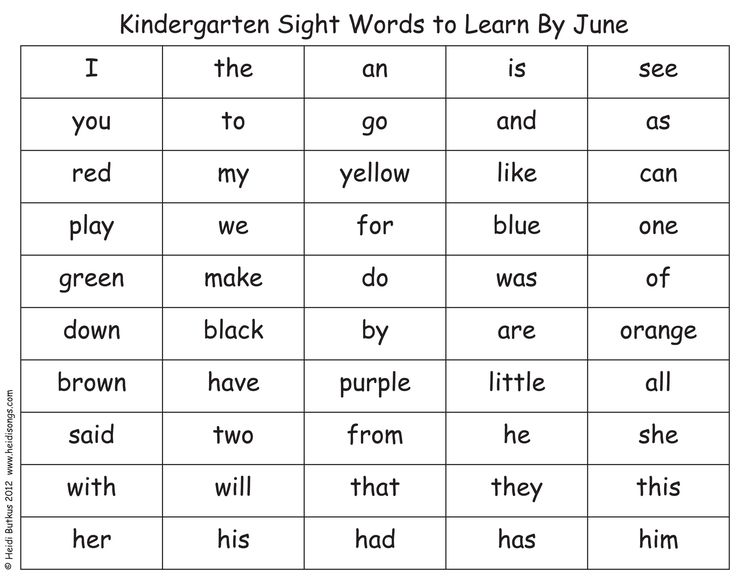

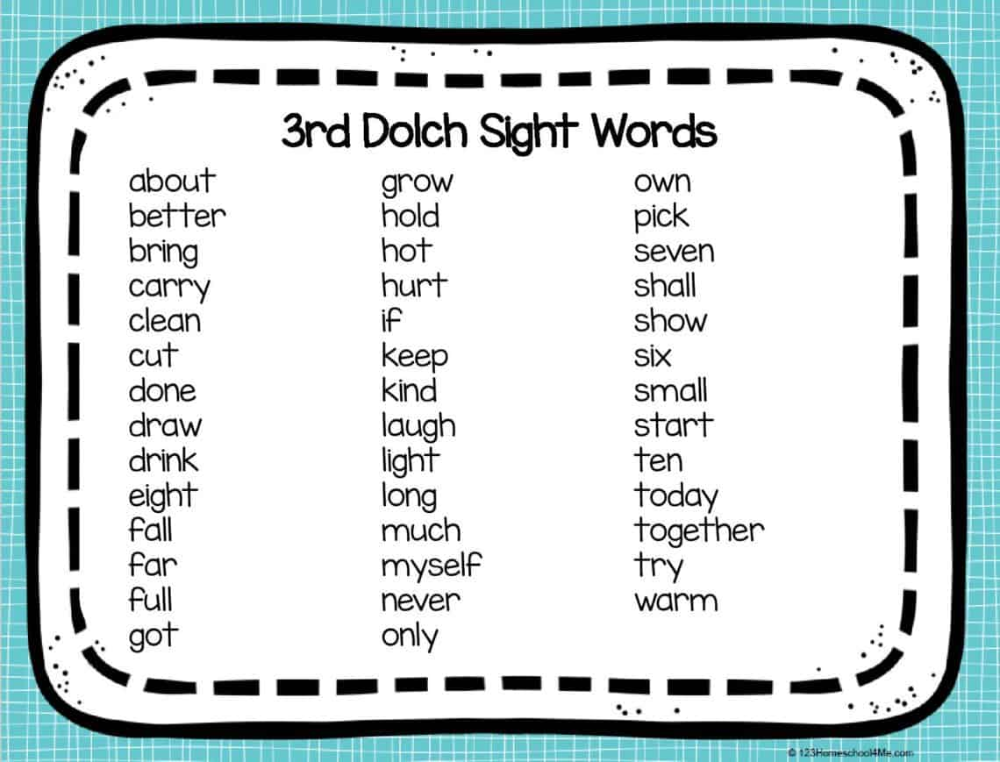

So what does this tell us about the big sight word lists … like Dolch and Fry?

I don’t think it’s wrong to teach kids to read words using those lists as a reference, but we need to approach it a different way.

We shouldn’t be sending home lists of 50 “sight words” for our kindergartners to master.

Instead, we should integrate those words into phonics lessons as often as possible.

For example, the Dolch primer list includes words like these:

on, at, did, that, ran

Each of those words is perfectly decodable, and rather than teach them by sight, we should teach kids to read them using their phonics knowledge.

When we give then opportunities to sound out the words when reading them, we are providing an environment for orthographic mapping to take place.

Is there ever room for teaching kids to memorize high frequency words?

Yes, but only a small amount (think 10-15 words), and only to make our students’ early reading material readable.

For example, a good decodable book (that actually sounds like a story) will need words like the. You will need to teach early readers to recognize the word the. And yet you can STILL call attention to the “th,” which is not irregular at all.

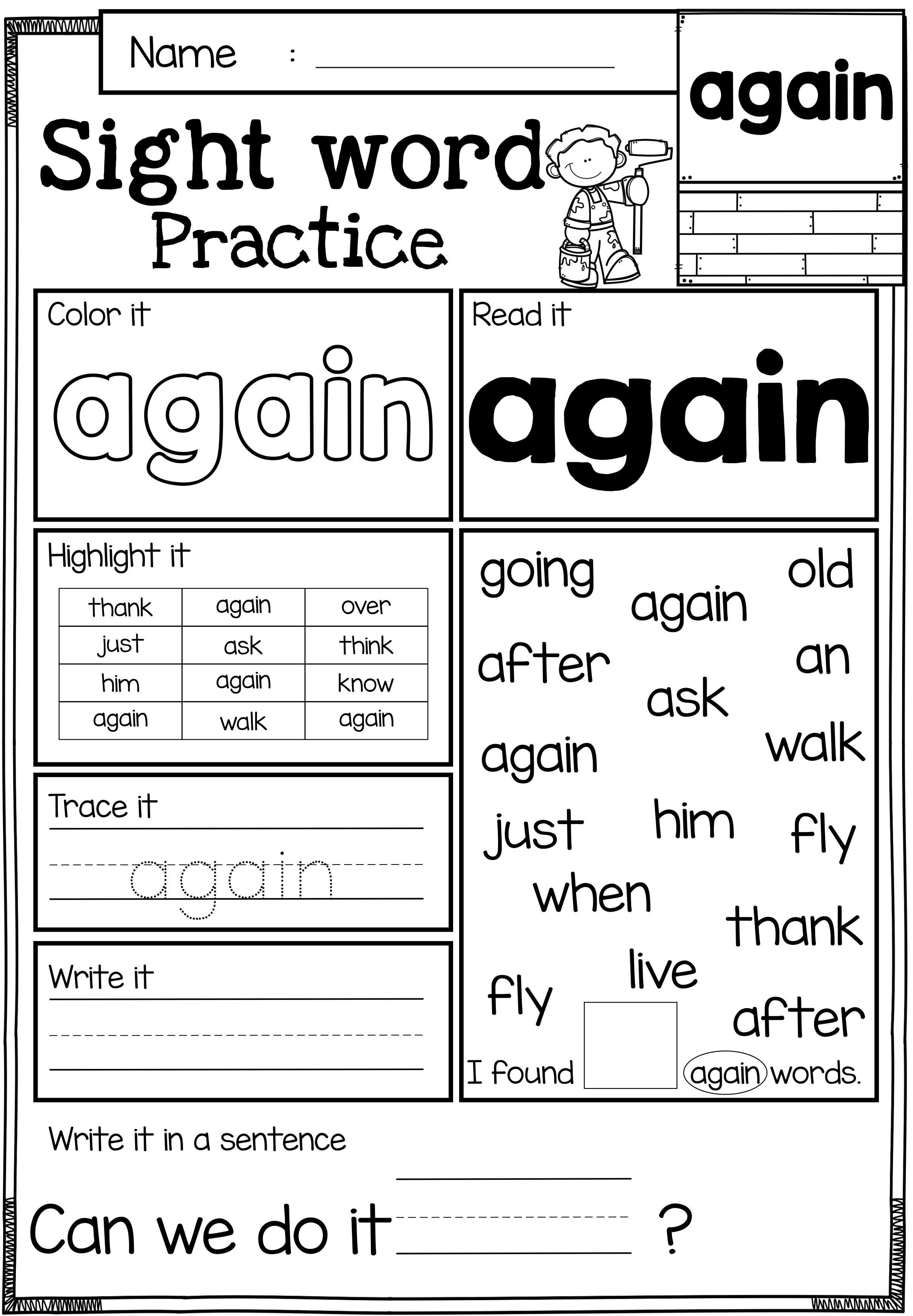

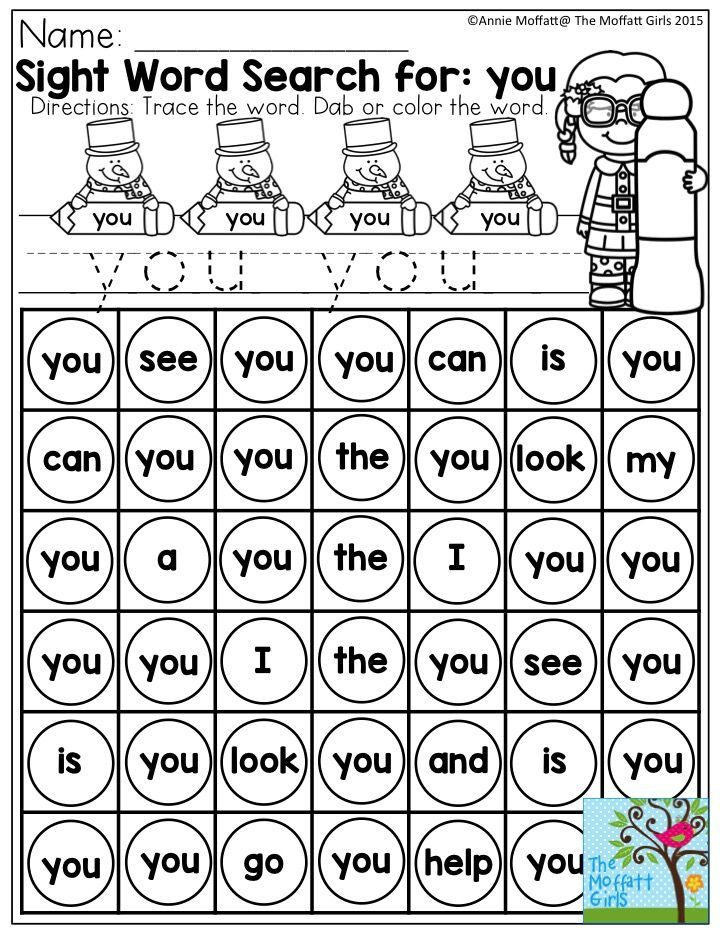

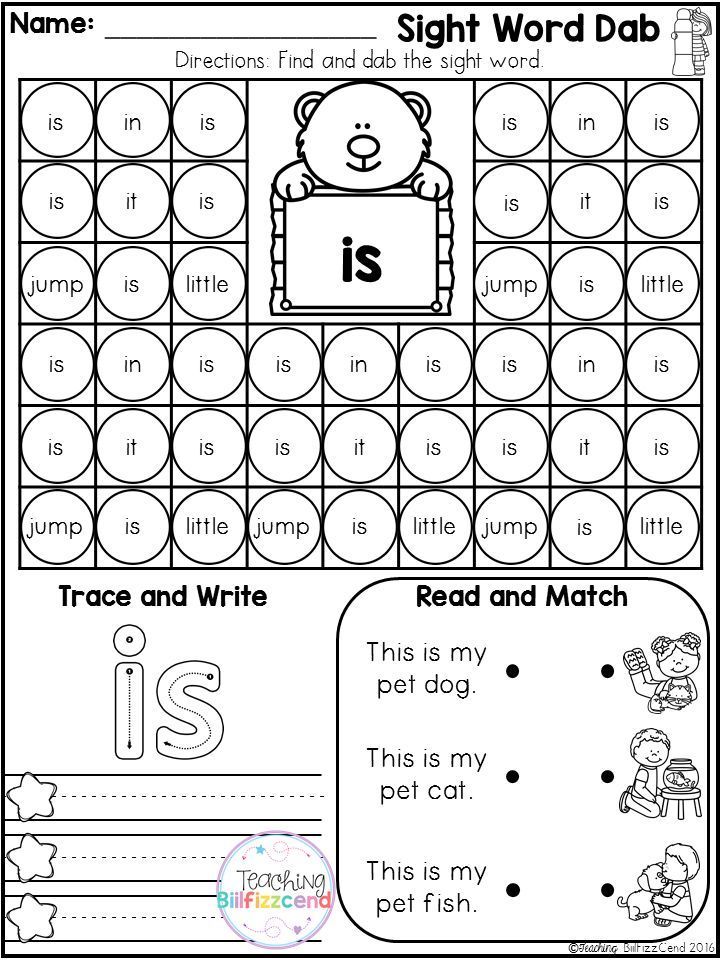

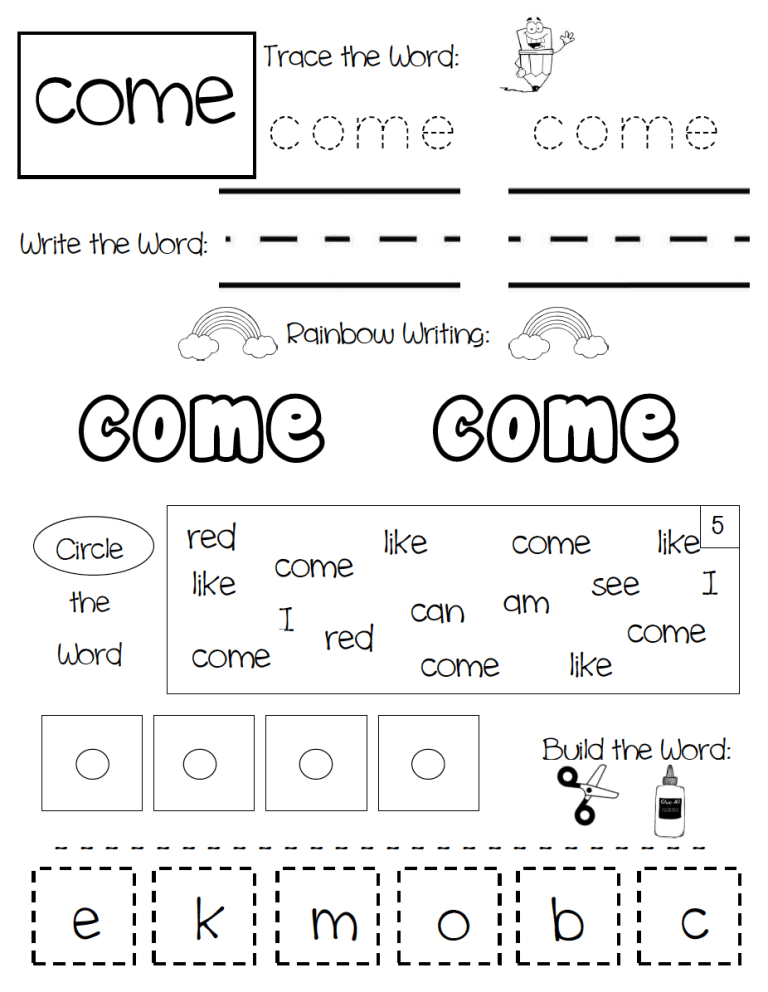

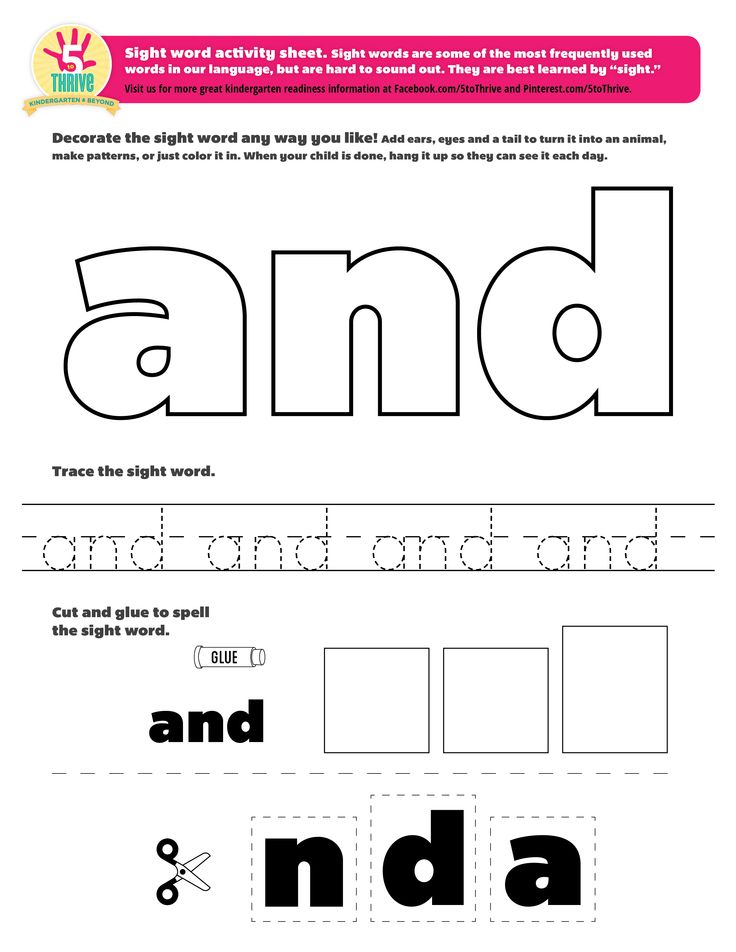

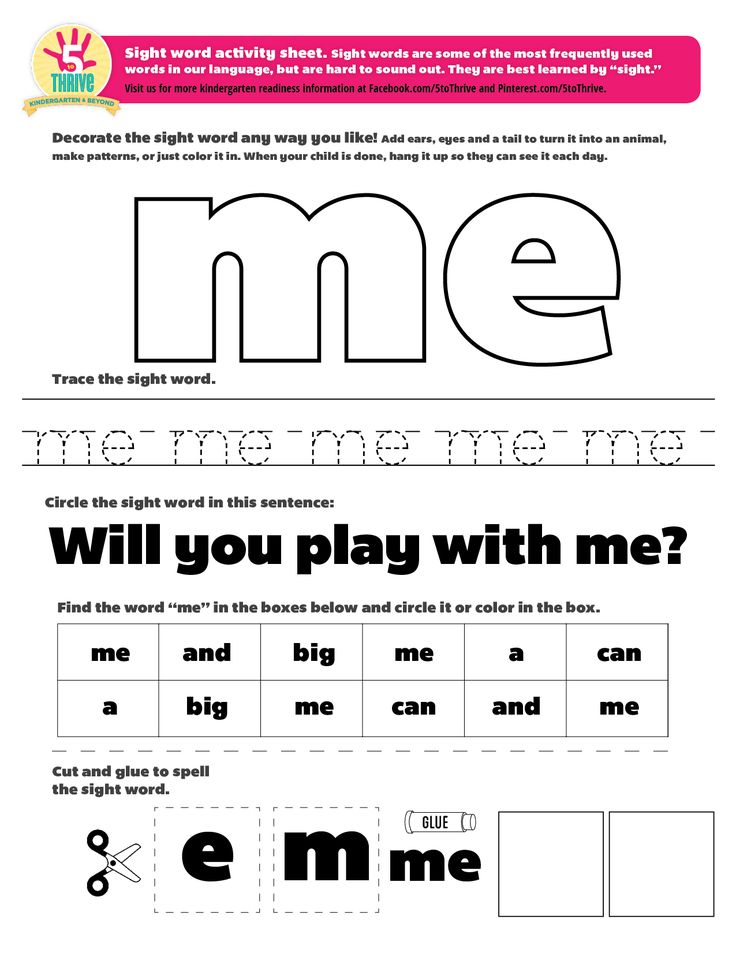

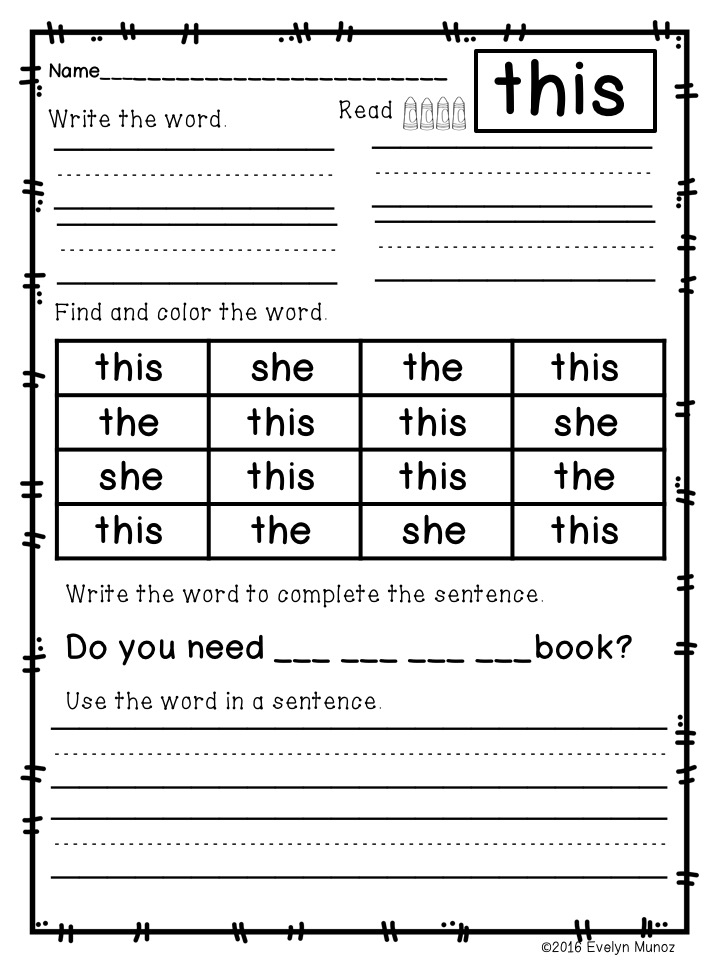

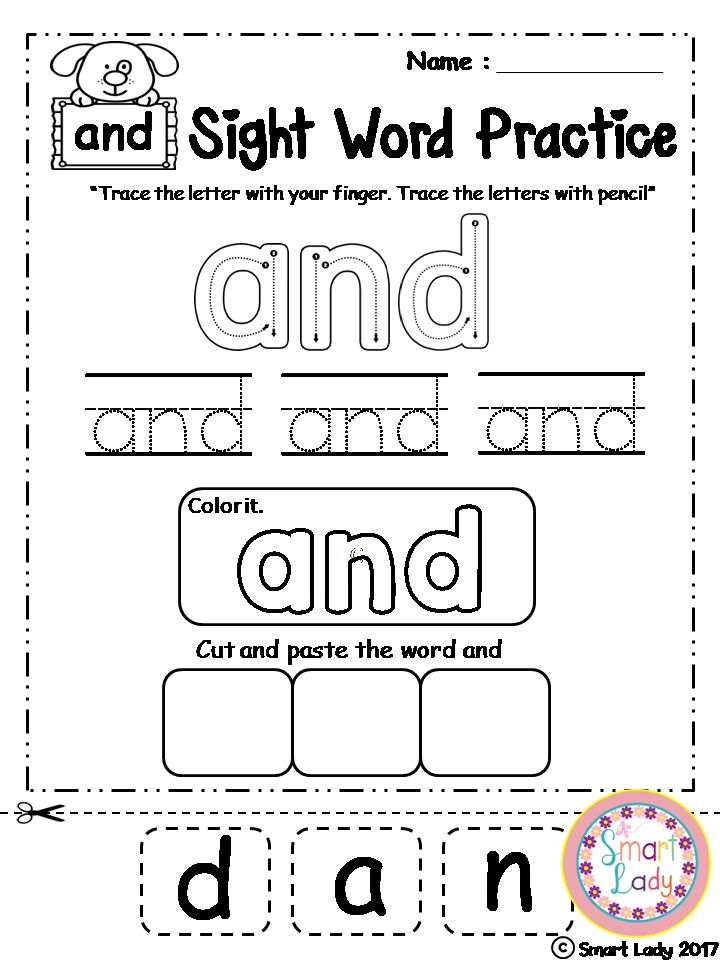

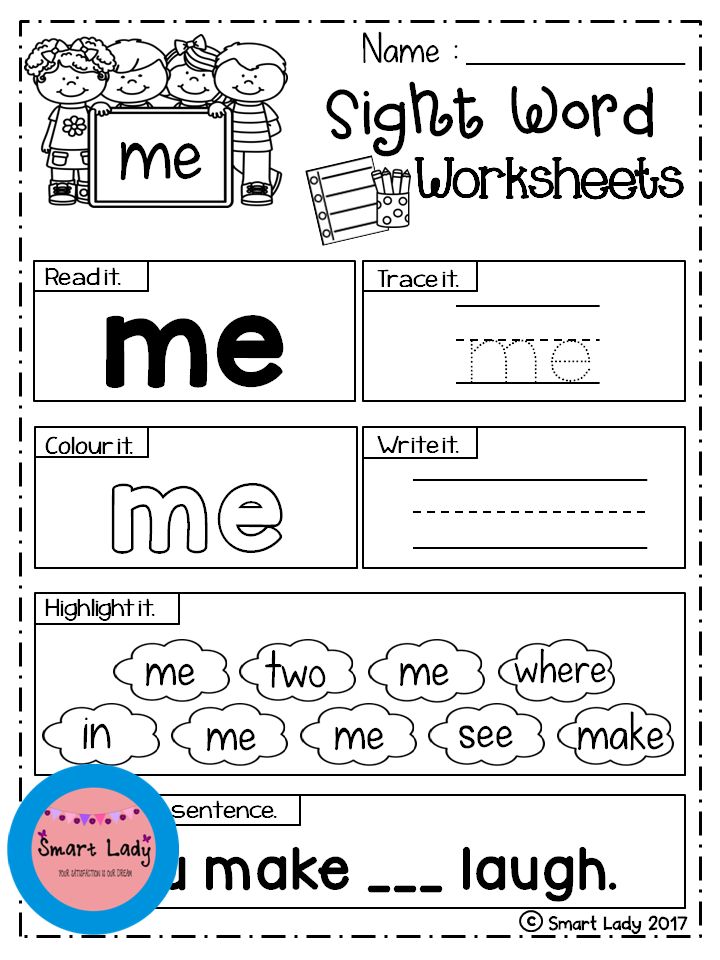

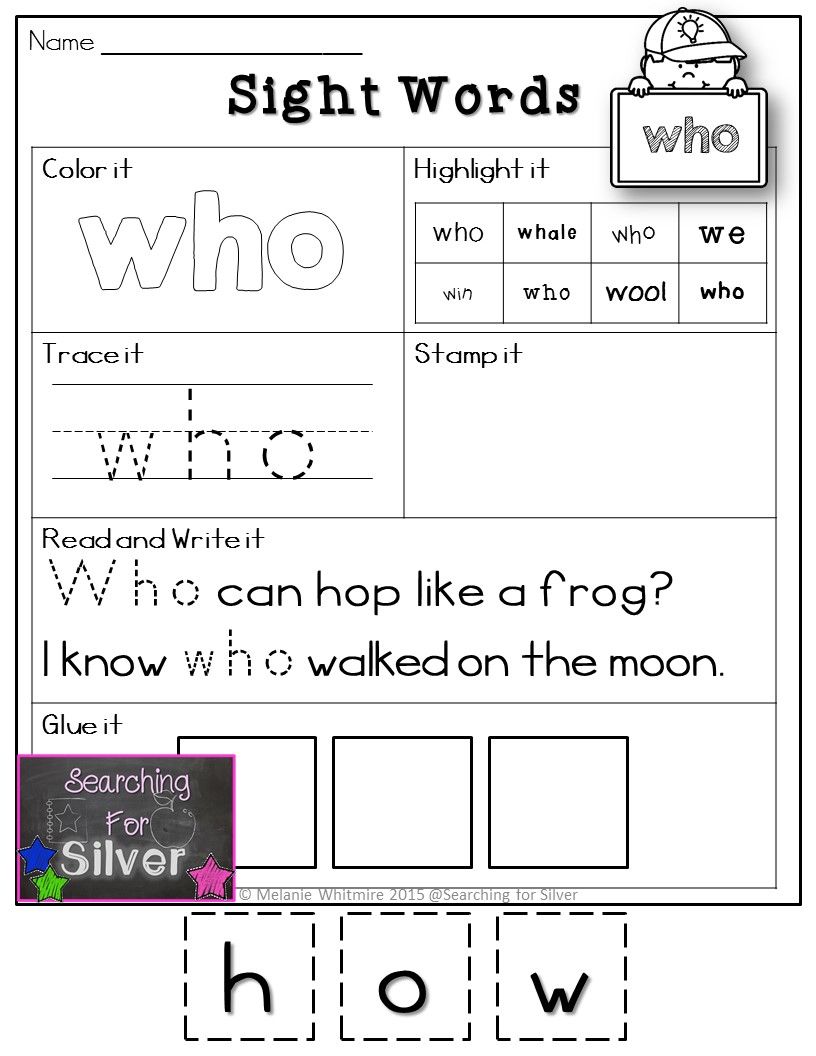

How to introduce sight words

- Assuming your learner has phonemic awareness and letter-sound knowledge, you’re ready to begin.

(Not sure about the phonemic awareness? Give this free assessment.)

(Not sure about the phonemic awareness? Give this free assessment.) - Name the new word, and have your learner repeat it.

- Name the individual phonemes (sounds) in the word. For example, in the word is, there are two phonemes: /i/ and /z/.

- Spell the sounds. Call attention to any unexpected spelling. In is, we spell /i/ with i and /z/ with s.

- If possible, have your learner read related words. Has and his are great words to read alongside is because they are short vowel words with an s that represents the the /z/ sound.

- Have your learner read connected text. Connected text can be decodable sentences or books.

Part 1 Part 2 Part 3 Part 4 Part 5 Part 6 Part 7 Part 8 Part 9

More resources for learning about high frequency words

- Free lessons and decodable books for teaching high frequency words

- A new model for teaching high frequency words – Reading Rockets

- Heart Word Magic – Really Great Reading

- Teaching Every Reader (online course)

- Essentials of Assessing Preventing, and Overcoming Reading Difficulties, by David A.

Kilpatrick

Kilpatrick

Free Reading Printables for Pre-K-3rd Grade

Join our email list and get this sample pack of time-saving resources from our membership site! You'll get phonemic awareness, phonics, and reading comprehension resources ... all free!

What Are Sight Words? Get the Definition Plus Teaching Resources

When you’re a new teacher, the number of buzzwords that you have to master seems overwhelming at times. You’ve probably heard about many concepts, but you may not be entirely sure what they are or how to use them in your classroom. For example, new teacher Katy B. asks, “This seems like a really basic question, but what are sight words, and where do I find them?” No worries, Katy. We have you covered!

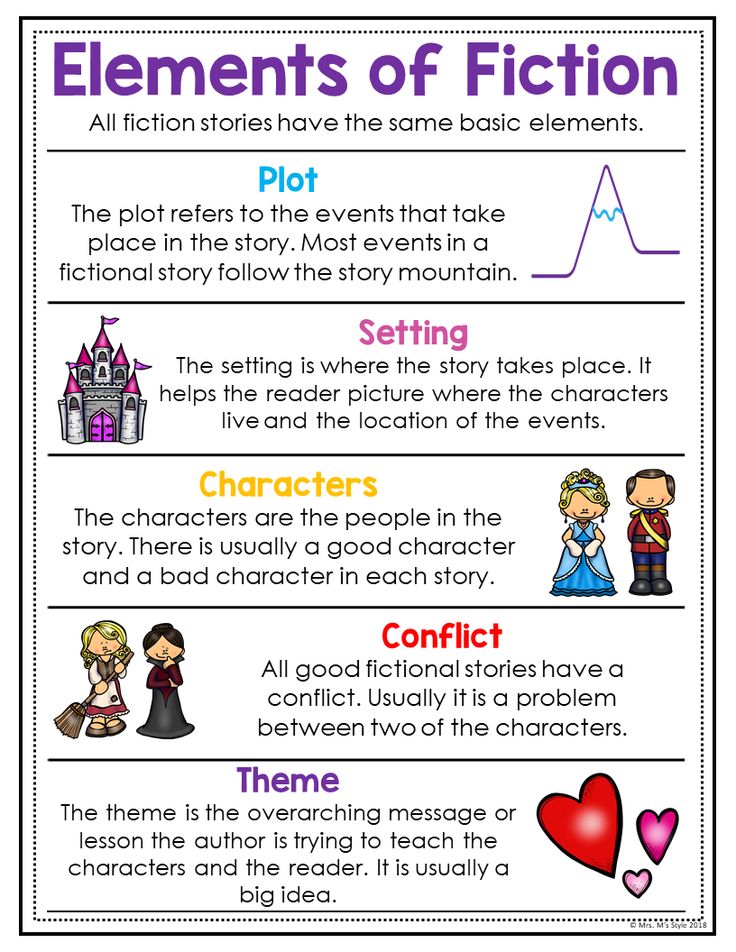

What’s the difference between sight words and high-frequency words?

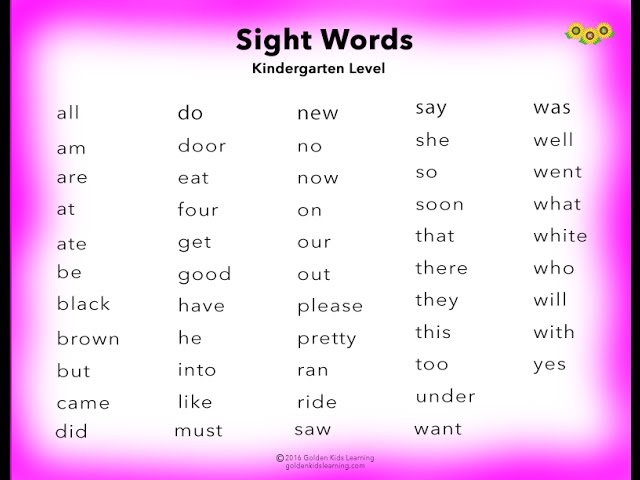

Oftentimes we use the terms sight words and high-frequency words interchangeably. Opinions differ, but our research shows that there is a difference. High-frequency words are words that are most commonly found in written language. Although some fit standard phonetic patterns, some do not. Sight words are a subset of high-frequency words that do not fit standard phonetic patterns and are therefore not easily decoded.

High-frequency words are words that are most commonly found in written language. Although some fit standard phonetic patterns, some do not. Sight words are a subset of high-frequency words that do not fit standard phonetic patterns and are therefore not easily decoded.

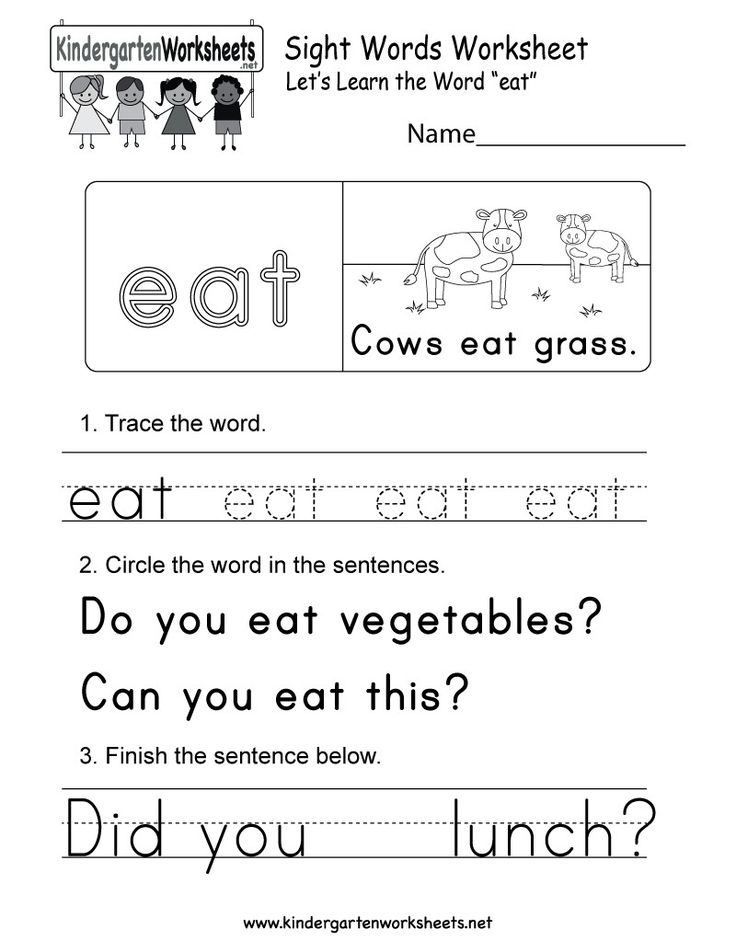

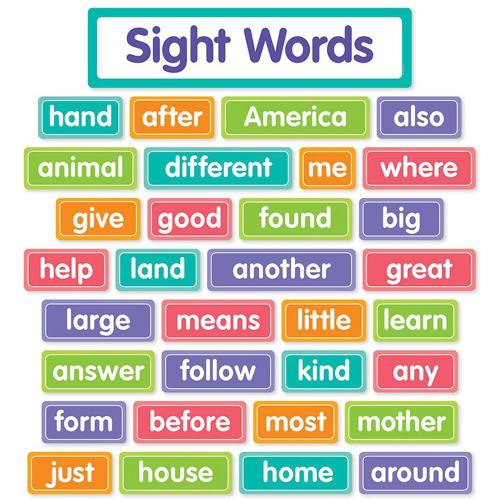

We use both types of words consistently in spoken and written language, and they also appear in books, including textbooks, and stories. Once students learn to quickly recognize these words, reading comes more easily.

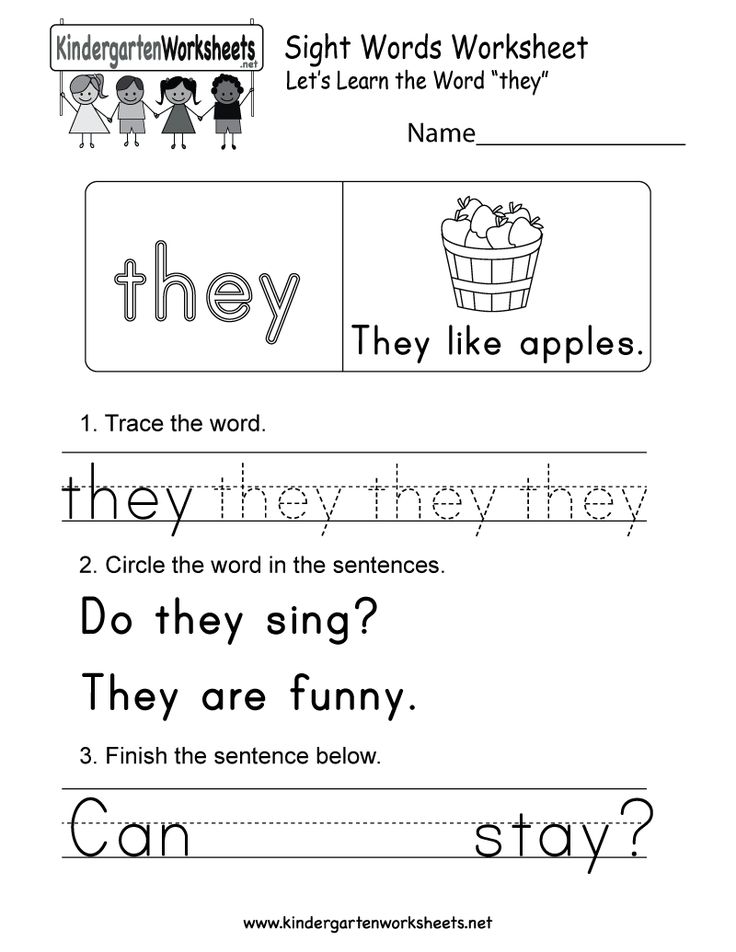

What are sight words and how can I teach my students to memorize them?

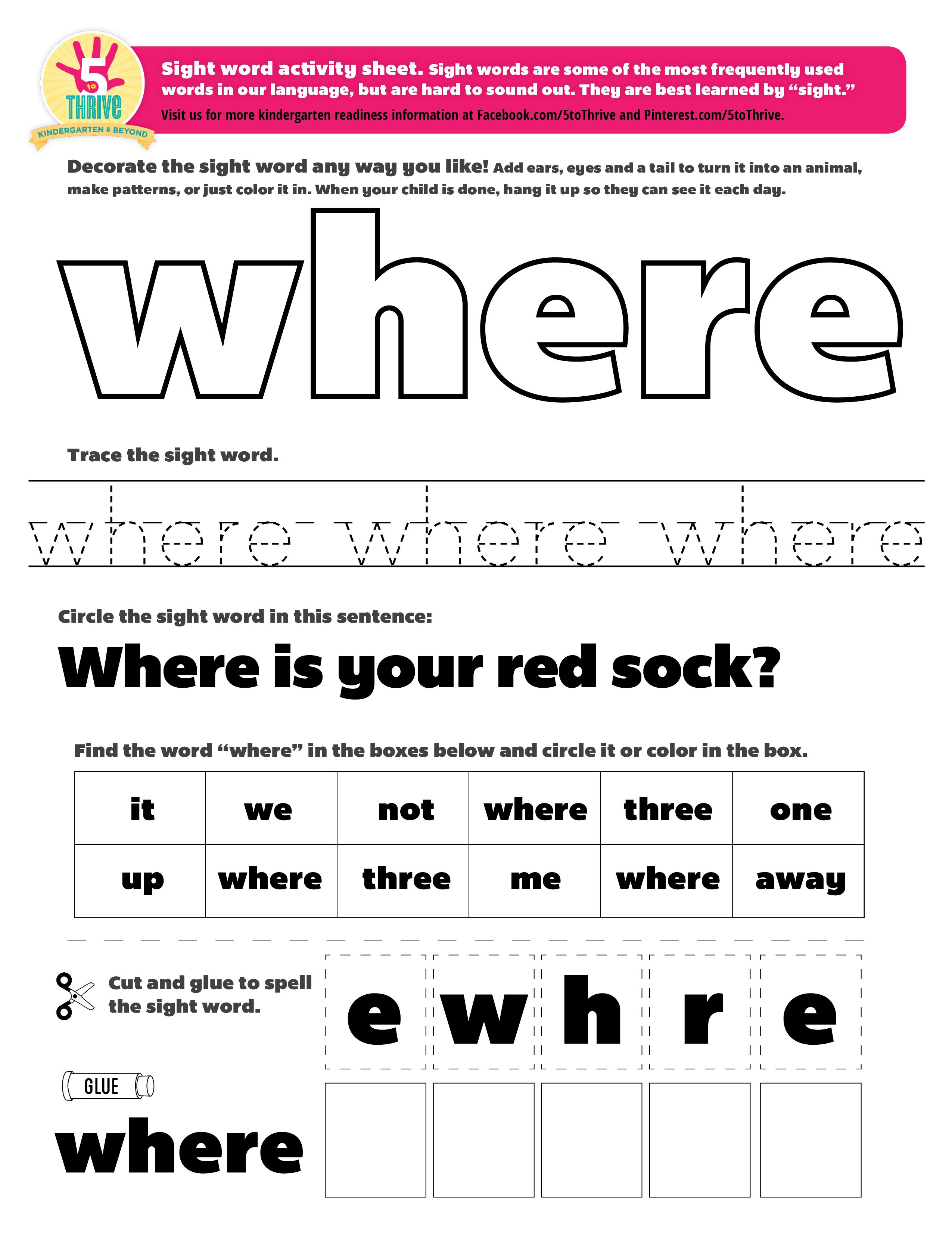

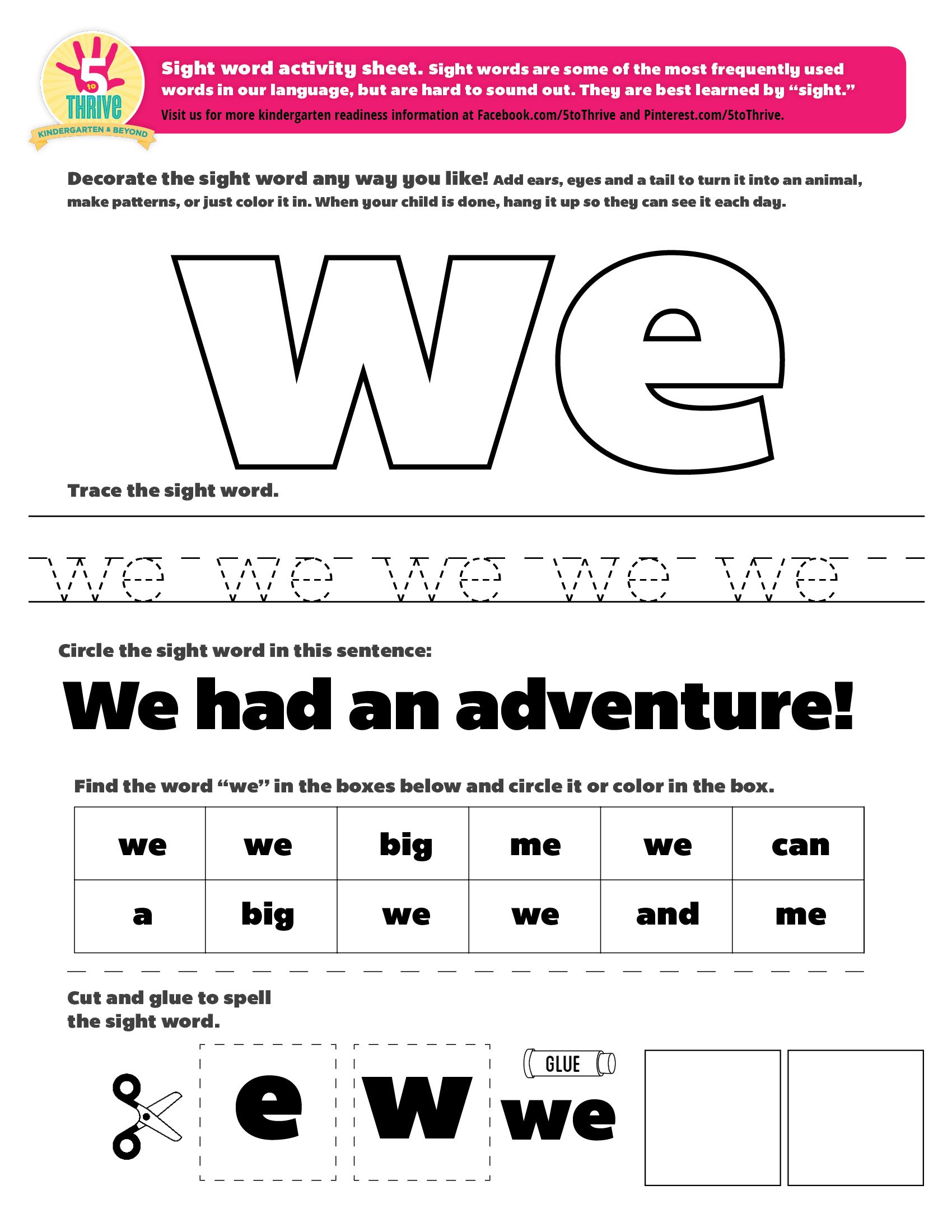

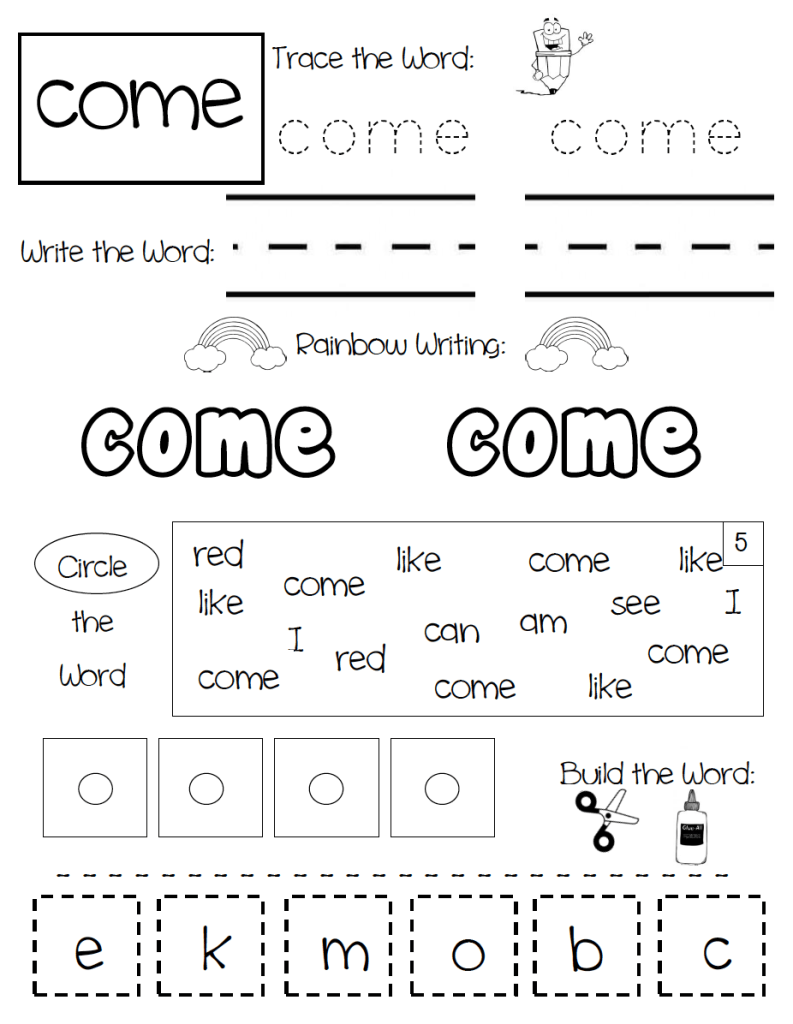

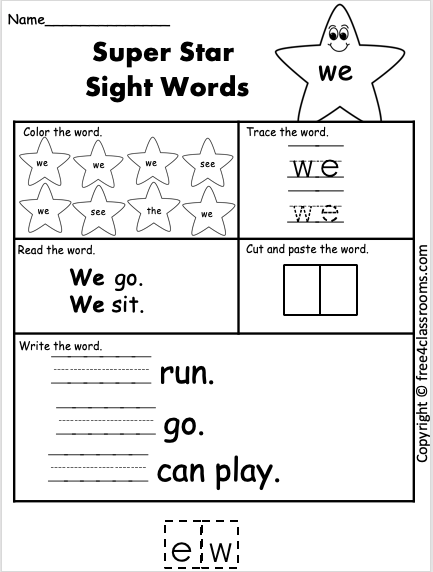

Sight words are words like come, does, or who that do not follow the rules of spelling or the six types of syllables. Decoding these words can be very difficult for young learners. The common practice has been to teach students to memorize these words as a whole, by sight, so that they can recognize them immediately (within three seconds) and read them without having to use decoding skills.

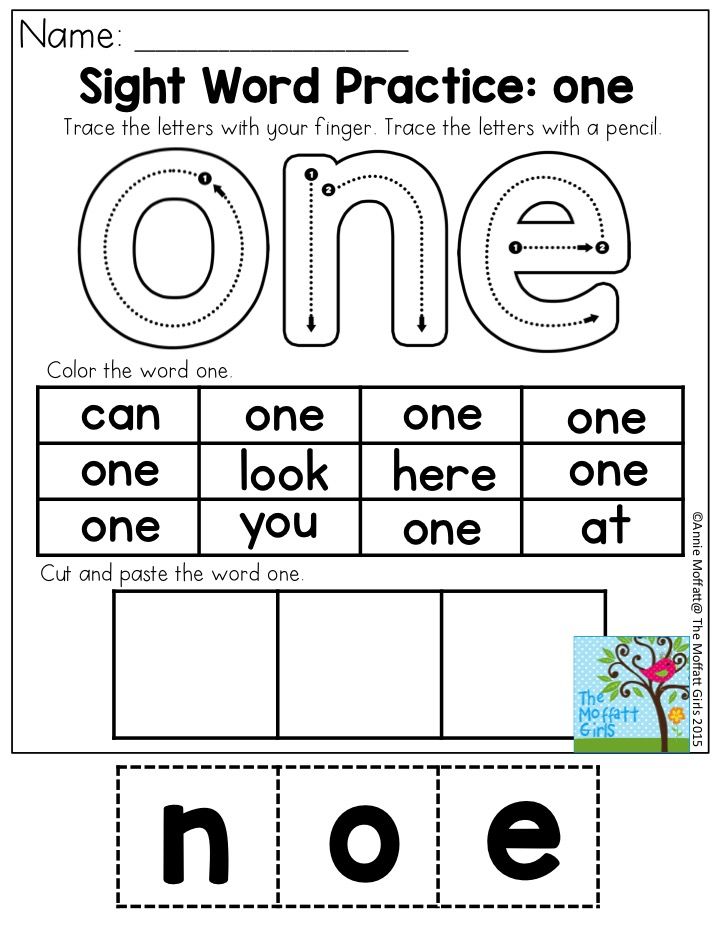

Can I teach sight words using the science of reading?

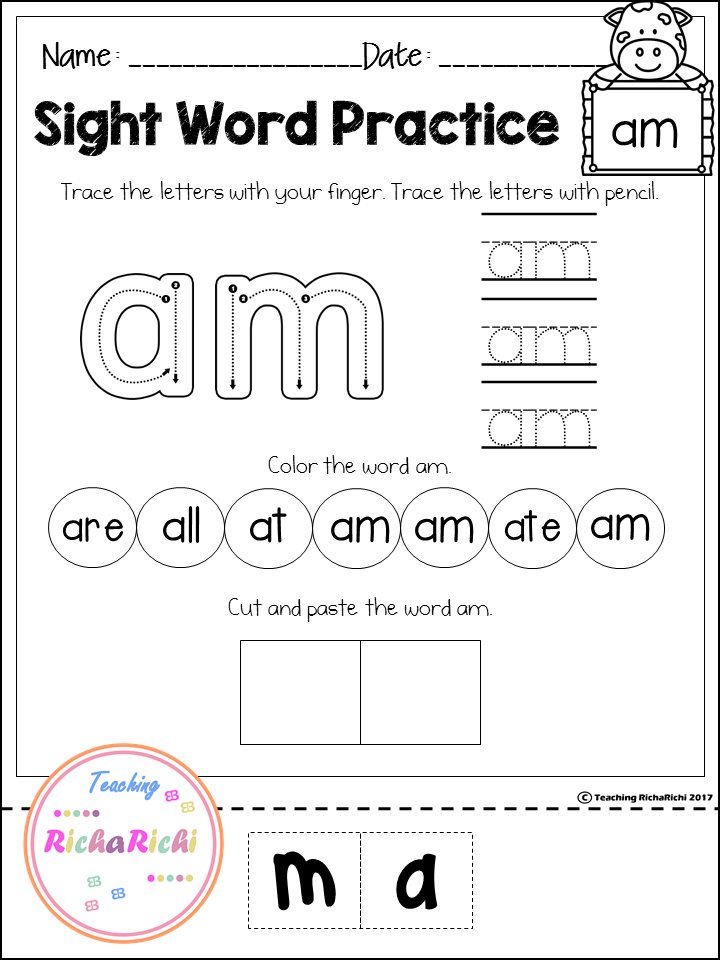

On the other hand, recent findings based on the science of reading suggests we can use strategies beyond rote memorization. According to the the science of reading, it is possible to sound out many sight words because they have recognizable patterns. Literacy specialist Susan Jones, a proponent of using the science of reading to teach sight words, recommends a method called phoneme-grapheme mapping where students first map out the sounds they hear in a word and then add graphemes (letters) they hear for each sound.

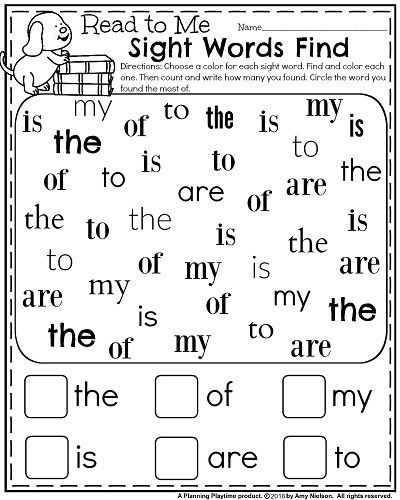

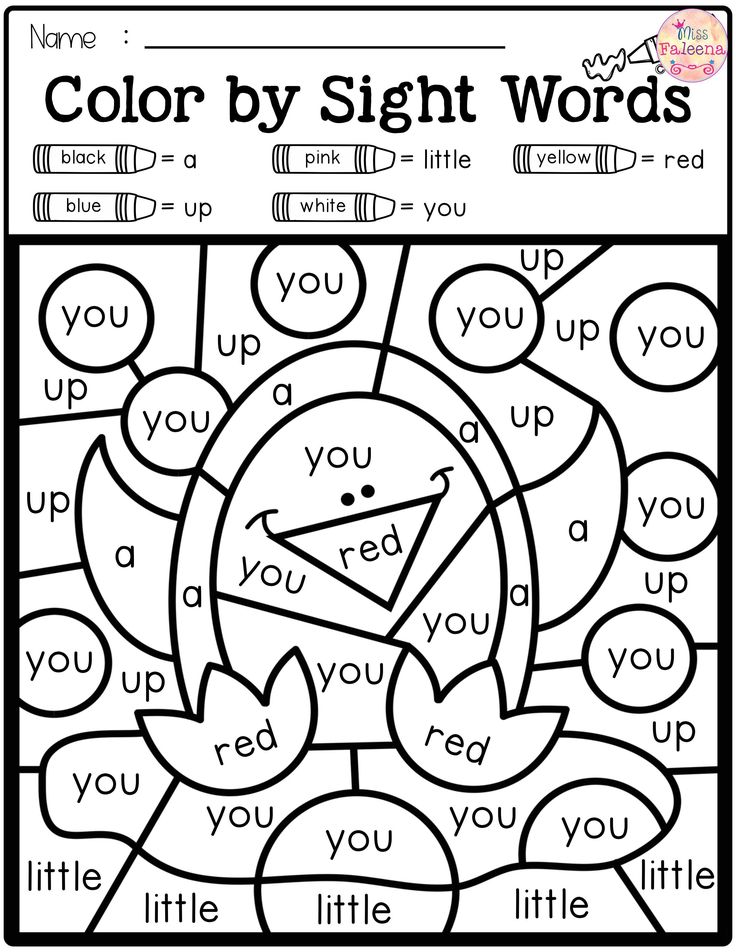

How else can I teach sight words?

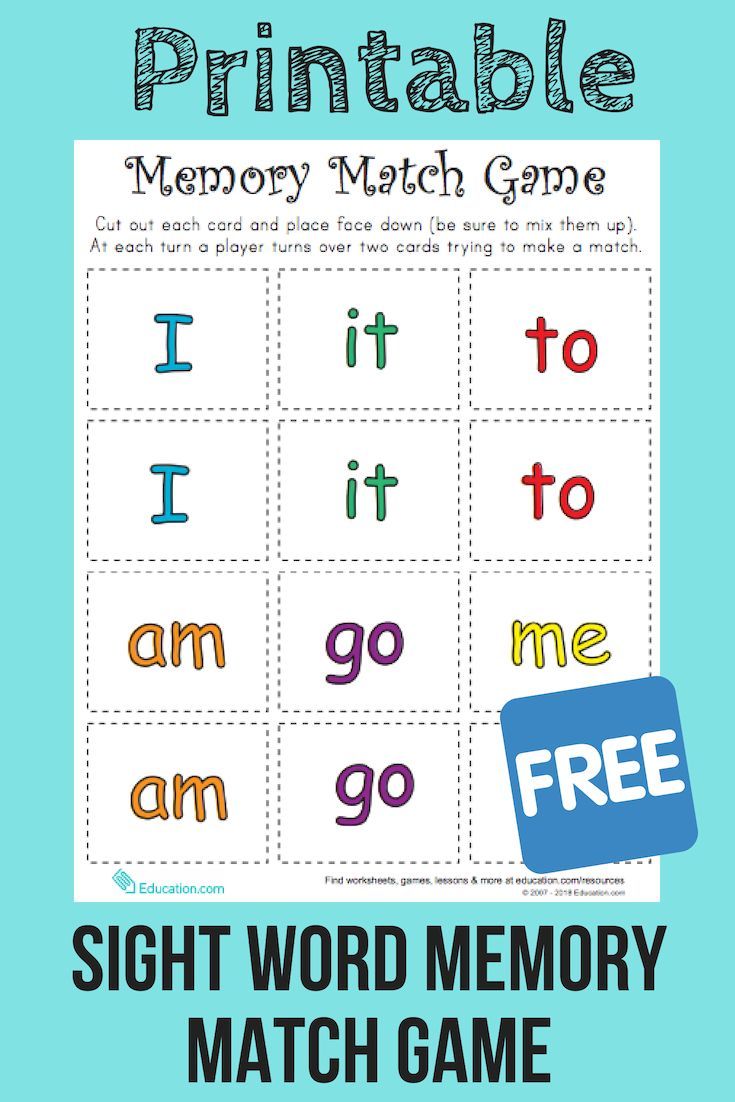

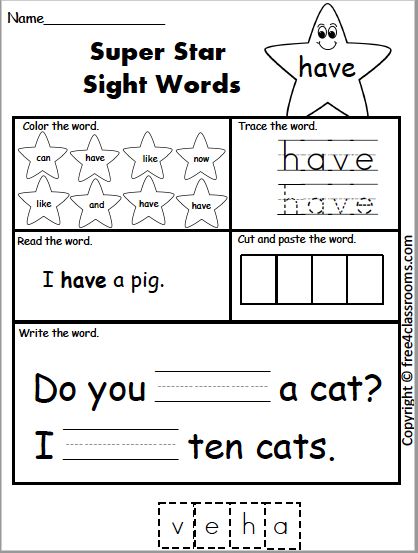

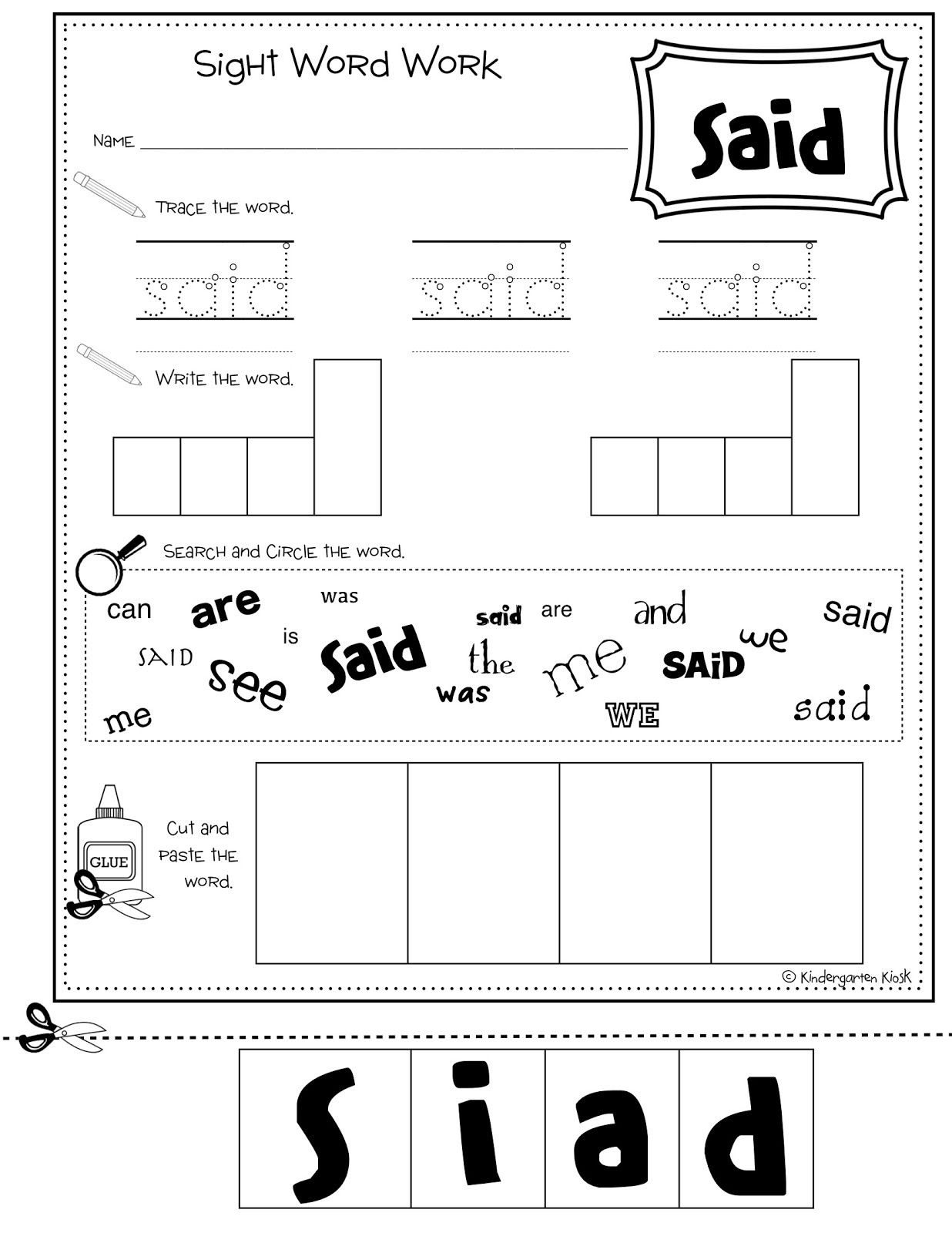

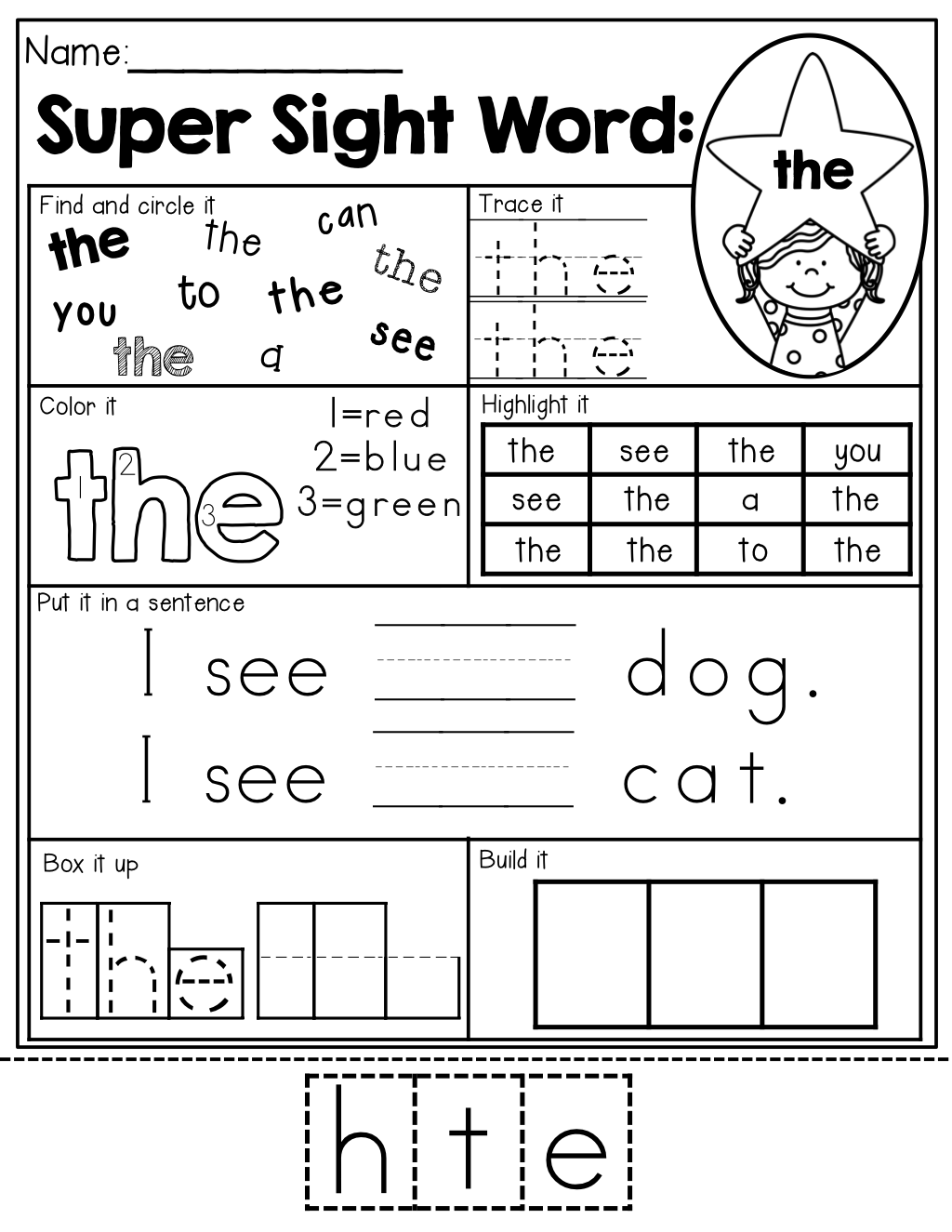

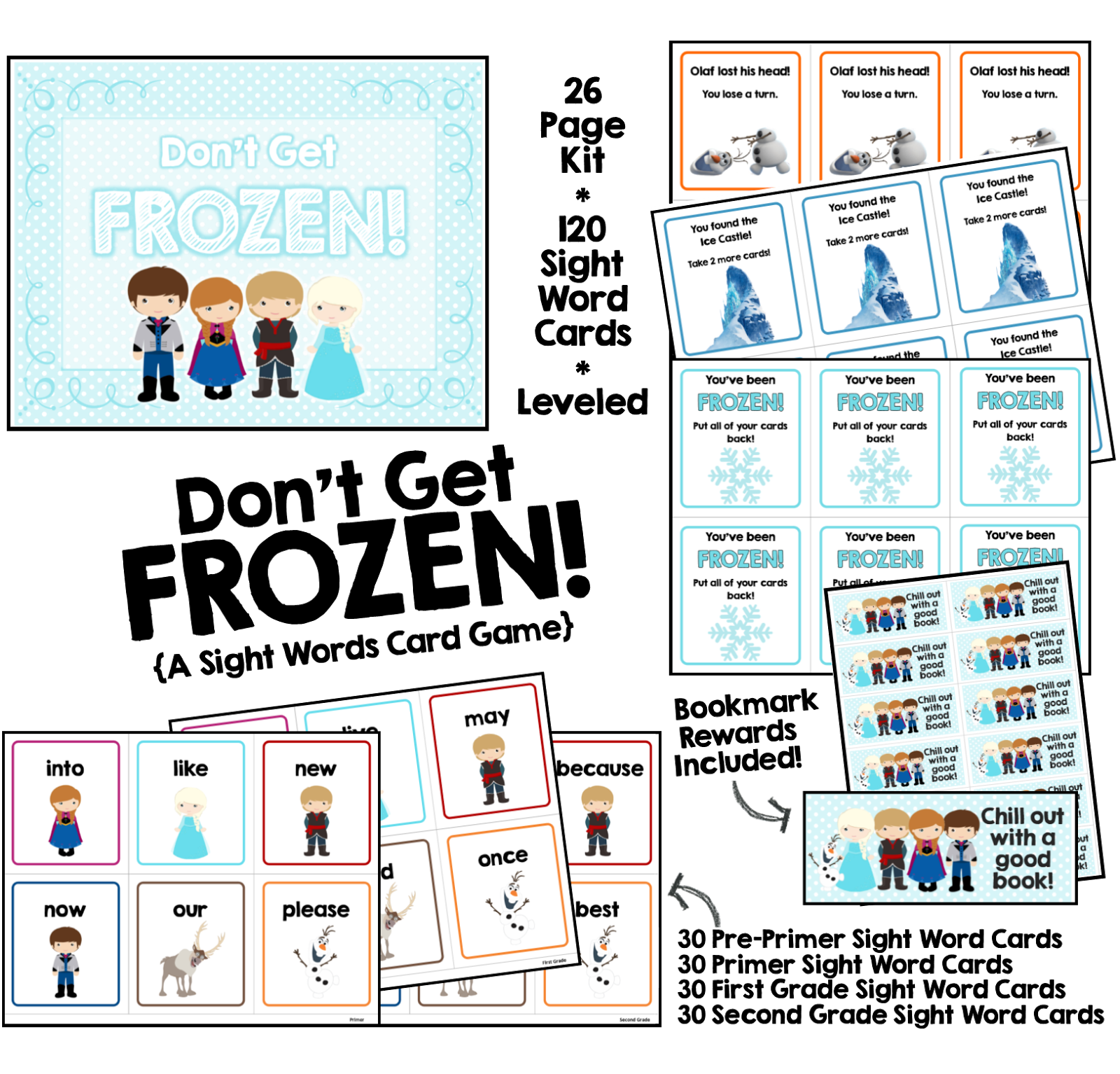

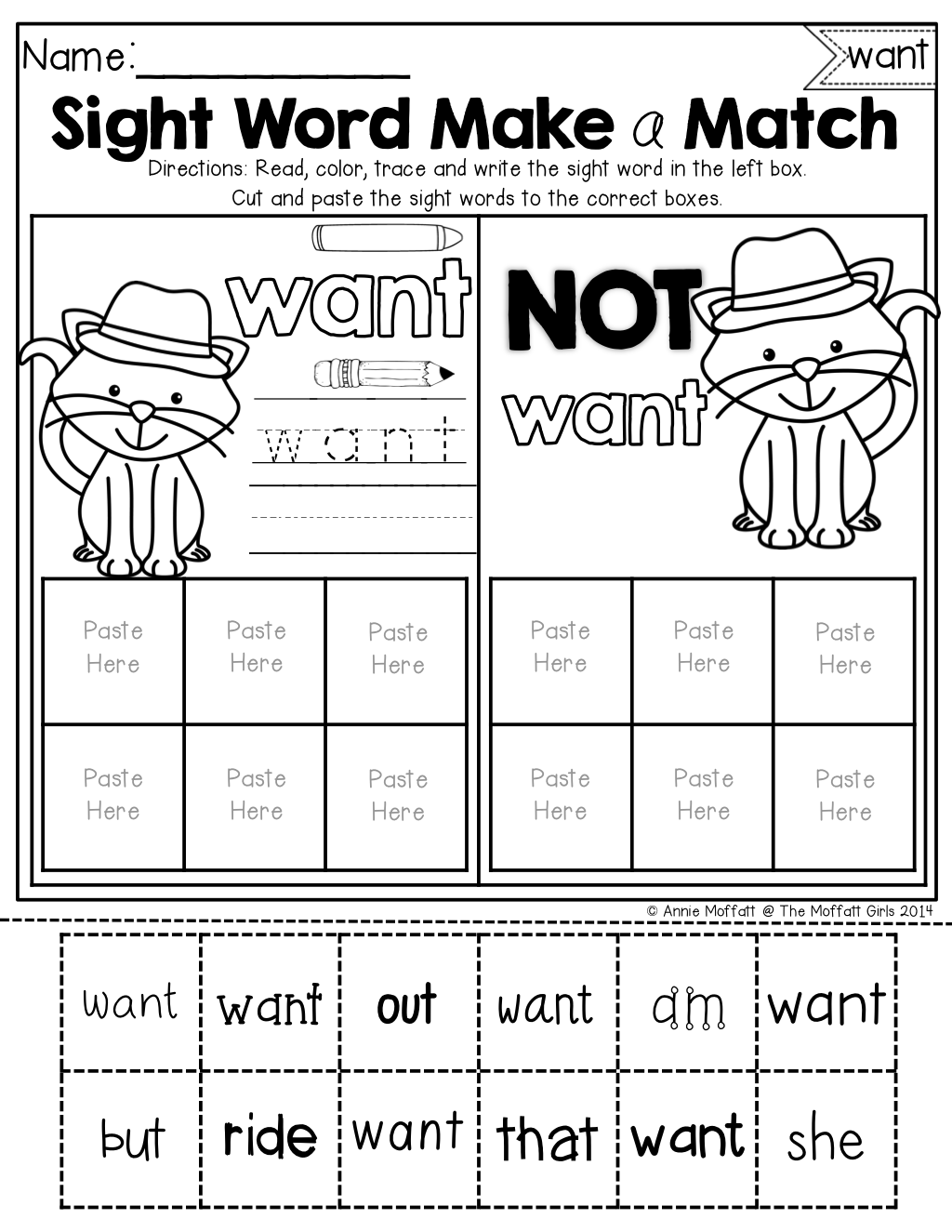

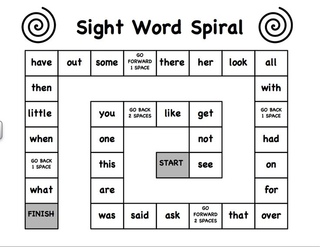

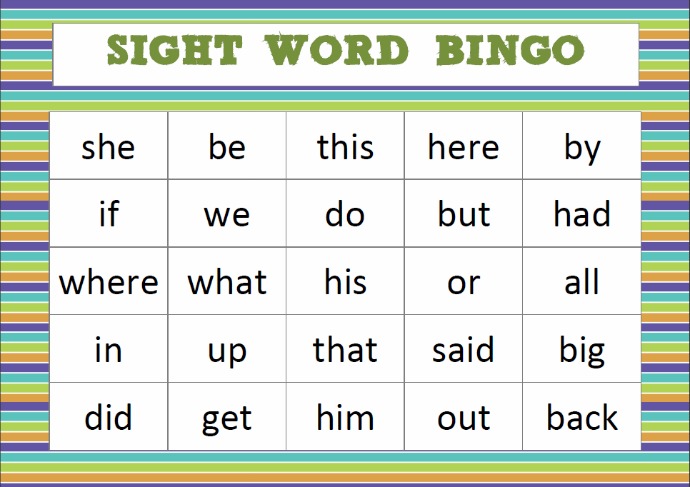

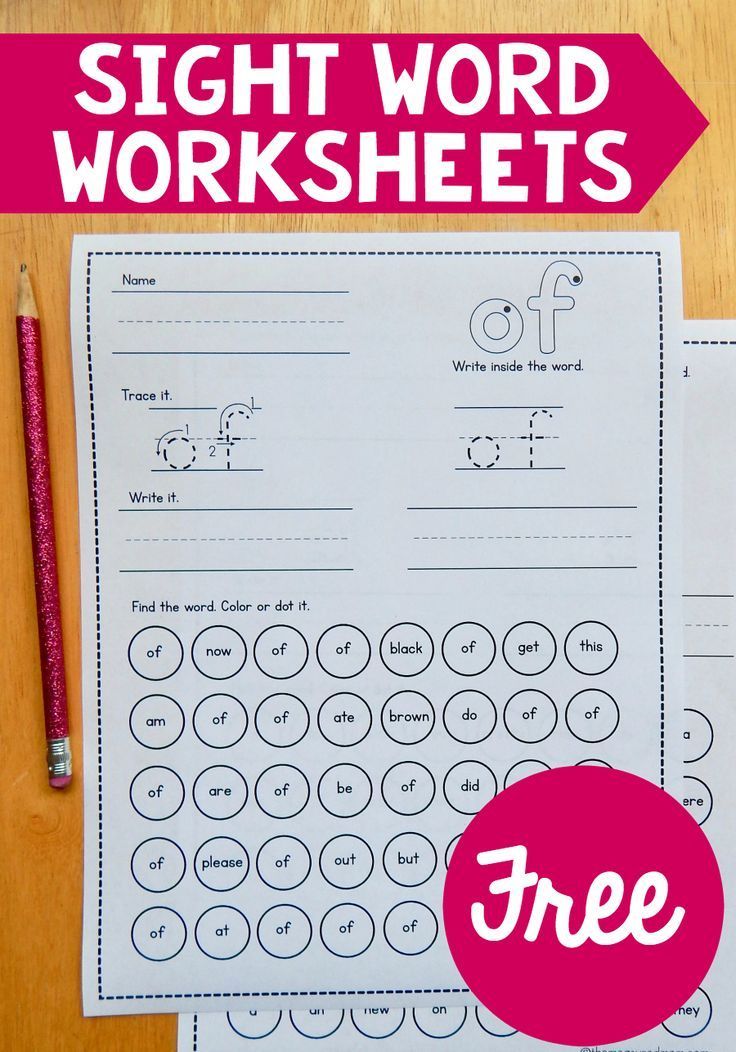

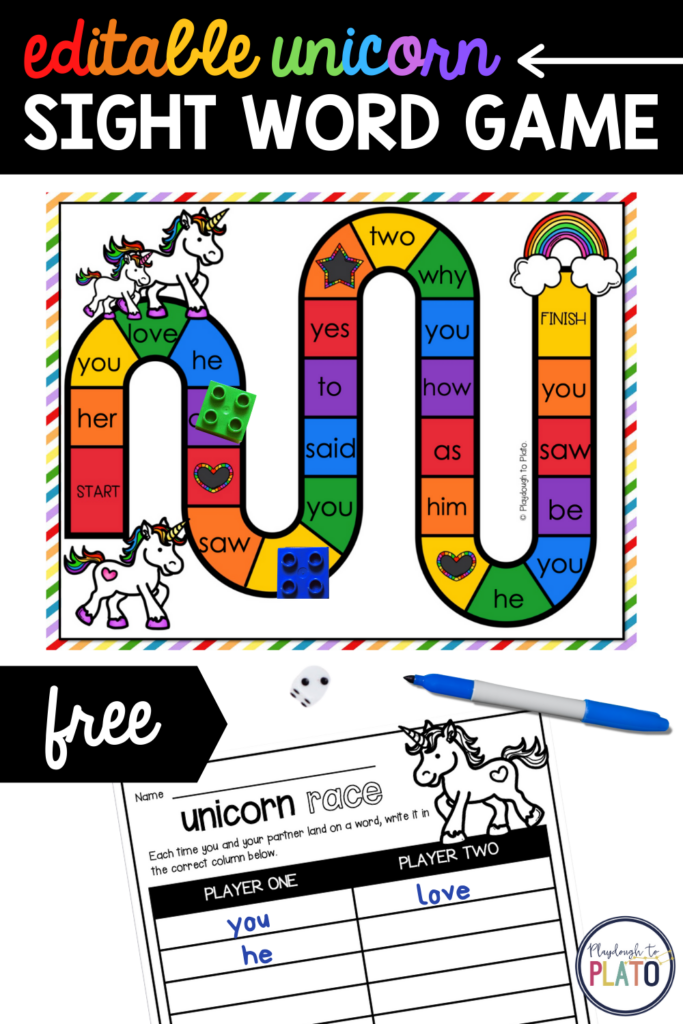

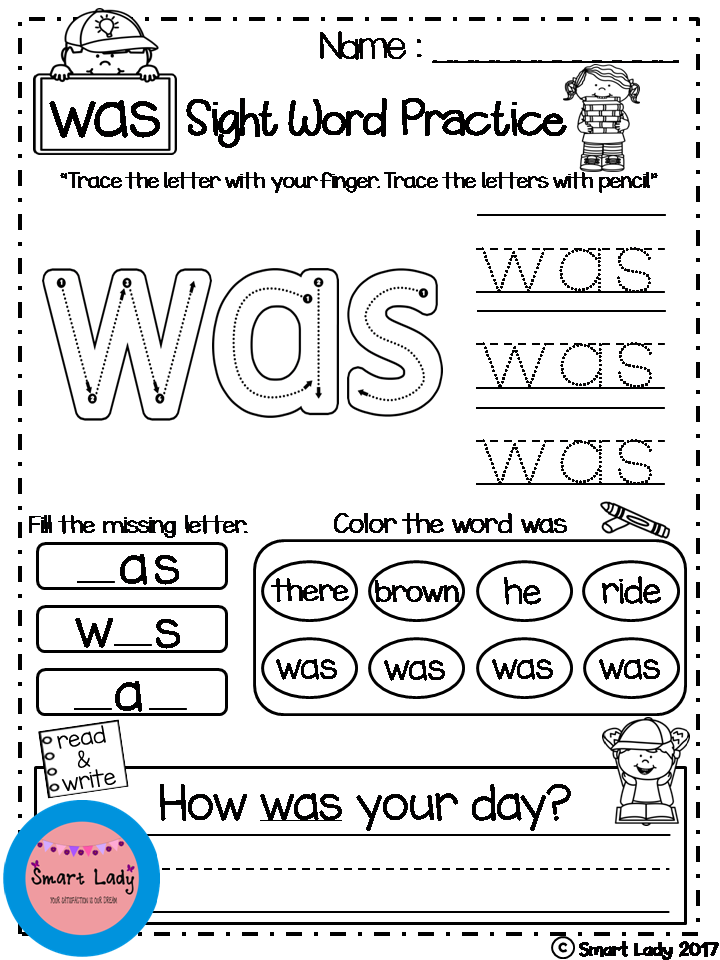

There are many fun and engaging ways to teach sight words. Dozens of books on the subject have been published, including the much-revered Comprehensive Phonics, Spelling, and Word Study Guide by Fountas & Pinnell. Also, resources like games, manipulatives, and flash cards are readily available online and in stores. To help get you started, check out these Creative and Simple Sight Word Activities for the Classroom. Also, check out Susan Jones Teaching for three science-of-reading-based ideas and more.

Also, check out Susan Jones Teaching for three science-of-reading-based ideas and more.

ADVERTISEMENT

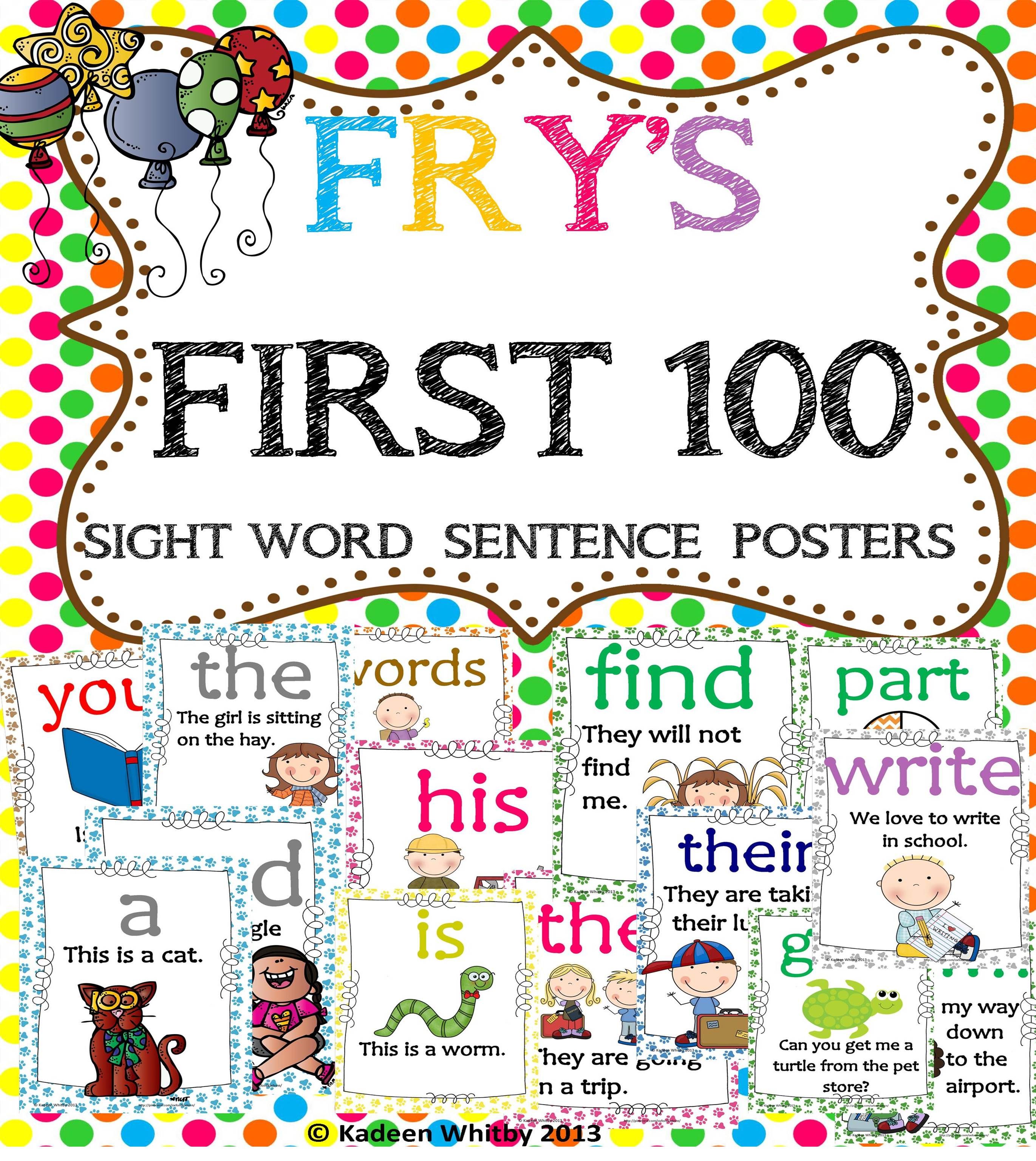

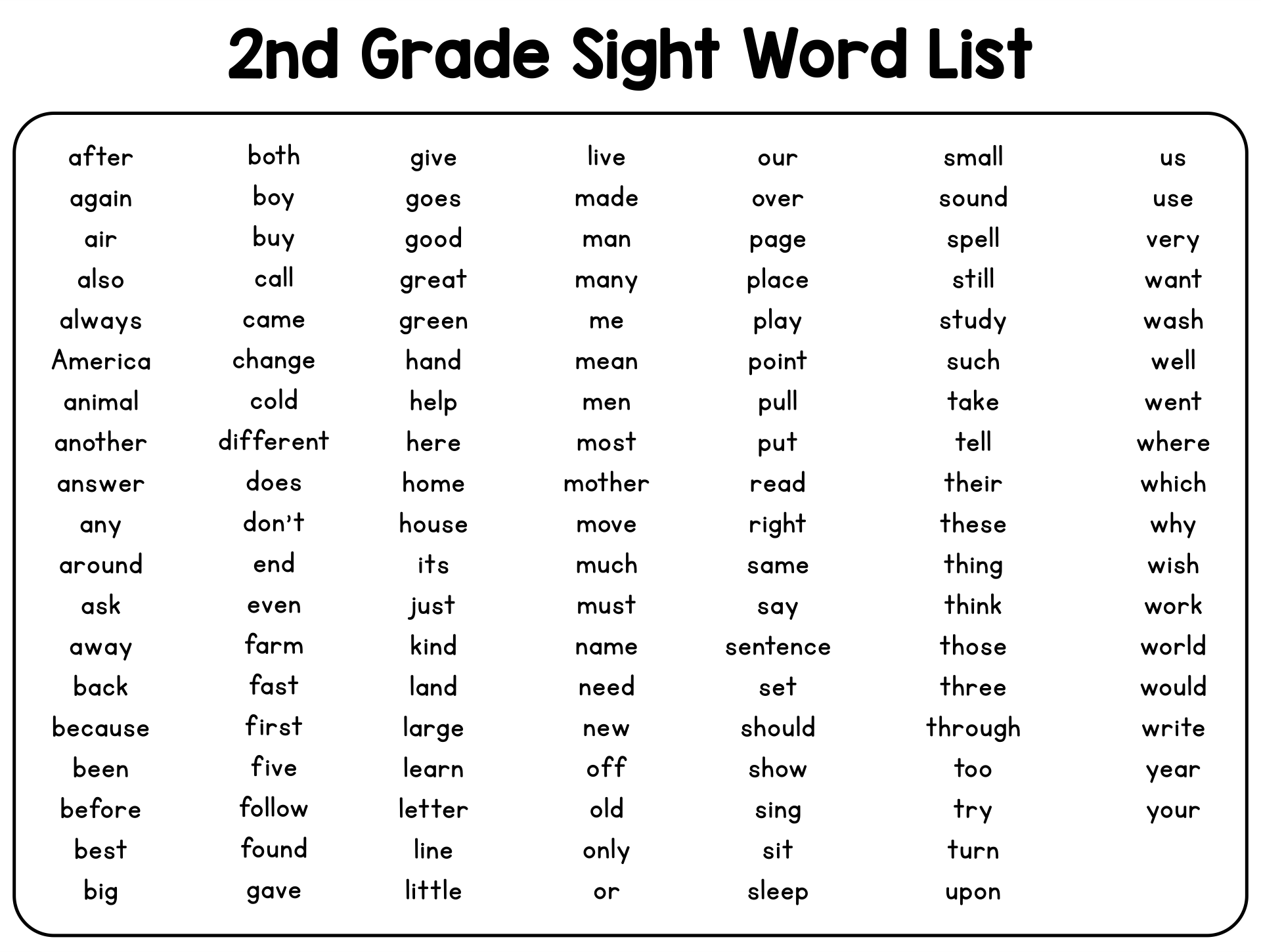

Where do I find sight word lists?

Two of the most popular sources are the Dolch High Frequency Words list and the Fry High Frequency Words list.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Dr. Edward Dolch developed his word list, used for pre-K through third grade, by studying the most frequently occurring words in the children’s books of that era. The list has 200 “service words” and also 95 high-frequency nouns. The Dolch word list comprises 80 percent of the words you would find in a typical children’s book and 50 percent of the words found in writing for adults.

Dr. Edward Fry developed an expanded word list for grades 1–10 in the 1950s (updated in 1980), based on the most common words that appear in reading materials used in grades 3–9. The Fry list contains the most common 1,000 words in the English language. The Fry words include 90 percent of the words found in a typical book, newspaper, or website.

Looking for more sight word activities? Check out 20 Fun Phonics Activities and Games for Early Readers.

Want more articles like this? Be sure to sign up for our newsletters.

Read online Targeted Thinking. Decision-making according to the methods of the British special services”, David Omand – Litres

Translator Vsevolod Baronin

Scientific editor Denis Bukin Chief Editor S. Turko

Project Manager O. Ravdanis

Art Director Yu. Buga

Cover design D. Izotov

Corrector E. Chudinova

Computer layout A. Abramov

SHITTERSTOCK.com

© 2020 9000

THE AUTHOR HAS ASSERTED rights

All rights reserved

Original English language edition first published by Penguin Books Ltd, London

© Russian edition, translation, layout. Alpina Publisher LLC, 2022

All rights reserved. This e-book is intended solely for private use for personal (non-commercial) purposes. The e-book, its parts, fragments and elements, including text, images and others, may not be copied or used in any other way without the permission of the copyright holder. In particular, such use is prohibited, as a result of which an electronic book, its part, fragment or element becomes available to a limited or indefinite circle of persons, including via the Internet, regardless of whether access is provided for a fee or free of charge.

The e-book, its parts, fragments and elements, including text, images and others, may not be copied or used in any other way without the permission of the copyright holder. In particular, such use is prohibited, as a result of which an electronic book, its part, fragment or element becomes available to a limited or indefinite circle of persons, including via the Internet, regardless of whether access is provided for a fee or free of charge.

Copying, reproduction and other use of an e-book, its parts, fragments and elements, beyond private use for personal (non-commercial) purposes, without the consent of the copyright holder is illegal and entails criminal, administrative and civil liability.

* * *

Dedicated to Keira, Robert, Beatrice and Ada

with the hope that they will grow up in a better world

Science editor's preface

This is a book about the art of thinking. Logic is a wonderful science, it gives the laws of strict, unmistakable and impeccable thinking. But life rarely provides enough information for impeccable logical conclusions. It is easy to talk about abstract things without having to do anything. In real life, when there is neither clarity nor time to clarify the facts, and circumstances force you to act, you have to rely on what is - conditionally reliable information. David Omand has lived the life of an intelligence official, in which it is not customary to answer “I don’t know,” so he rightfully shares his practical ability to build a picture of several pieces of the puzzle. Using his approaches, you can “wash” a good result from an unreliable information breed. Yes, at times you will be mistaken, but you will be able to act, and that's fine.

But life rarely provides enough information for impeccable logical conclusions. It is easy to talk about abstract things without having to do anything. In real life, when there is neither clarity nor time to clarify the facts, and circumstances force you to act, you have to rely on what is - conditionally reliable information. David Omand has lived the life of an intelligence official, in which it is not customary to answer “I don’t know,” so he rightfully shares his practical ability to build a picture of several pieces of the puzzle. Using his approaches, you can “wash” a good result from an unreliable information breed. Yes, at times you will be mistaken, but you will be able to act, and that's fine.

We have few books on methods of thinking, especially those related to intelligence. The last similar one, Washington Platt's Strategic Intelligence Information Work, was published in Russian back in 1958, and it is still recommended in specialized educational institutions to this day. At the same time, books on the work of an intelligence analyst are published regularly in English. Perhaps we are hindered by the excessive tendency of the domestic military departments to classify everything in the world, including the old, irrelevant and even known to everyone. Without a solid texture, writing a book will not work, and a fictional texture is unconvincing. Well, as long as there are no domestic books, we will read translated ones.

At the same time, books on the work of an intelligence analyst are published regularly in English. Perhaps we are hindered by the excessive tendency of the domestic military departments to classify everything in the world, including the old, irrelevant and even known to everyone. Without a solid texture, writing a book will not work, and a fictional texture is unconvincing. Well, as long as there are no domestic books, we will read translated ones.

And one more thing. As I edited this book, I often thought of Jerome K. Jerome: “In war, the soldiers of every country are always the bravest in the world. The soldiers of a hostile country are always treacherous and treacherous - that's why they sometimes win" [1] . In other cases, patriotism is an excellent virtue, but it is hardly good in intelligence, where independence of mind is much more valuable. There is no unity of interests between the various intelligence services of the country, just as there is none within the intelligence service, nor within its smallest subdivision. Deeds are determined not by organizations, but by a bizarre interaction of multidirectional interests of influential people, and these interests do not always consist in selfless service to the fatherland. Undoubtedly, any smart intelligence officer (and others in high positions are inappropriate) understands this, but will he openly write about it? Only sometimes, between the lines. And in other cases - to demonstrate ardent confidence in the correctness of the "good guys". Fortunately, fiction writers write about human ups and downs in intelligence. I am sure it will be easier to understand what is written here between the lines, recalling at times the novels of John Le Carré or the films based on these novels: The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965) and "Spy, get out!" (2011).

Deeds are determined not by organizations, but by a bizarre interaction of multidirectional interests of influential people, and these interests do not always consist in selfless service to the fatherland. Undoubtedly, any smart intelligence officer (and others in high positions are inappropriate) understands this, but will he openly write about it? Only sometimes, between the lines. And in other cases - to demonstrate ardent confidence in the correctness of the "good guys". Fortunately, fiction writers write about human ups and downs in intelligence. I am sure it will be easier to understand what is written here between the lines, recalling at times the novels of John Le Carré or the films based on these novels: The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965) and "Spy, get out!" (2011).

Denis Bukin

Foreword

Why We Need These Lessons: In Search of Independence of Thought, Honesty and Integrity

Westminster, March 1982. "This is very serious, isn't it?" asked Margaret Thatcher. She frowned and looked up from the intelligence reports I had given her. “Yes, Prime Minister,” I replied, “this information can be interpreted unequivocally: the Argentine junta is in the final stages of preparations for an invasion of the Falkland Islands. It is highly probable that the invasion will take place next Saturday.”

"This is very serious, isn't it?" asked Margaret Thatcher. She frowned and looked up from the intelligence reports I had given her. “Yes, Prime Minister,” I replied, “this information can be interpreted unequivocally: the Argentine junta is in the final stages of preparations for an invasion of the Falkland Islands. It is highly probable that the invasion will take place next Saturday.”

This conversation took place on the afternoon of Wednesday, March 31, 1982.

I was Chief Private Secretary to Secretary of Defense John Knott. We were sitting in his office in the House of Commons preparing for a speech in parliament when a liaison officer from military intelligence headquarters hurried into the government building. In his mail bag were several very conspicuously designed folders. From the red diagonal crosses on their dark covers, I immediately knew that they contained top secret material covered with a special code word UMBRA, meaning that they came from the Government Communications Center.

These folders contained decrypted radio intercepts from the Argentine navy. Reports said that an Argentine submarine was conducting covert reconnaissance near the capital of the Falkland Islands, the city of Stanley, and that the Argentine navy, which was on the exercises, was re-forming itself into battle formation. Another, more recent radio intercept mentioned an Argentine Navy task force that was due to arrive at an unspecified location early Friday, April 2. After analyzing the coordinates of the ships of this formation, the government communications headquarters came to the conclusion that only Port Stanley could be the target of the Argentines [2] .

John Knott and I looked at each other with one single thought: the loss of the Falklands would pose the gravest threat to the existence of Margaret Thatcher's government: therefore, the Prime Minister must be immediately informed of these radio intercepts. We hurried down the corridor to her office and literally burst into it.

The latest analysis the Prime Minister received from the UK Joint Intelligence Committee was that Argentina was unwilling to use military force to secure its claim to the sovereignty of the Falkland Islands. However, the Joint Intelligence Committee warned that if the British took extremely provocative action against Argentine citizens who had illegally landed on the British island of South Georgia in the South Atlantic, the junta could use this as a pretext to start hostilities. Since Britain had no intention of provoking the junta, such an assessment was misinterpreted in Whitehall as encouraging, which made the fresh intelligence all the more stunning. This was the first sign that the Argentine junta was ready to use military force to impose its demands.

The Importance of Reasoning

The shock of how the UK suddenly became involved in the Falklands Crisis is deeply ingrained in my memory. The situation showed me how important errors in our thinking can be. This is as true in the lives of individuals as it is in the administration of public affairs. And my goal in writing this book is ambitious: I want to empower people to make better decisions based on the way intelligence analysts think. I will bring lessons from our past to show exactly how one can know, explain and predict most of all the events that we face in our absolutely amazing age.

This is as true in the lives of individuals as it is in the administration of public affairs. And my goal in writing this book is ambitious: I want to empower people to make better decisions based on the way intelligence analysts think. I will bring lessons from our past to show exactly how one can know, explain and predict most of all the events that we face in our absolutely amazing age.

There are important life lessons to be learned from observing how intelligence analysts think. By studying their actions during problem solving in real situations in recent history, we learn how they organize their thoughts, distinguish between the probable and the improbable, and thus draw better conclusions. We will learn how to methodically test alternative explanations for what is happening and assess how much we need to change our own opinion as new information becomes available to us. We will try to understand how our own feelings, as well as the opinions of members of a particular community, can influence our judgments. We will also learn how one can fall prey to conspiracy thinking and be deceived through deliberate misinformation.

We will also learn how one can fall prey to conspiracy thinking and be deceived through deliberate misinformation.

We all face decision-making and choice processes, whether at home, at work or at play. But today, compared with the old days, we have negligibly little time to make a decision. We live in the digital age and are bombarded with conflicting, false and confusing information from a vast array of sources - more than ever. Information surrounds us from all sides, and we feel obliged to respond to it at the same speed with which it comes to us. There are powerful forces playing against us through messages and opinions spread through social media. We find ourselves overwhelmed by all this information and ask ourselves the question: have we become more or less ignorant than in former times? Today we need these lessons from the past, more than ever.

Looking over the shoulder of an intelligence analyst

In the history of the art of war, it has become clear to commanders the advantage that intelligence can provide.

Governments today are deliberately creating specialized services to access and analyze information that can help them make better decisions [3] . The Secret Intelligence Service of the British Foreign Office (MI6) oversees the work of intelligence agents abroad. Security Services (MI5) and its law enforcement partners investigate domestic threat situations and monitor suspects. The Government Communications Center is engaged in the interception of radio and electronic communications and the collection of digital intelligence. The military has its fair share of intelligence-gathering operations abroad, including photo reconnaissance from satellites and unmanned aerial vehicles. The task of the intelligence analyst is to piece together all the pieces of information received. Analysts are then identified with situation assessments designed to raise awareness among decision makers. They figure out what is happening, explain why it is happening, and describe how the situation might develop [4] .

The more we understand the nature of the decisions we must make, the less likely we are to misinterpret the facts, make bad choices, or be seriously surprised by the outcome. Much of what we need can be obtained from open sources, but only if we are careful enough to critically judge the quality of the information.

Being informed by the decision maker does not necessarily mean simplifying the situation. Often the assessment coming from the intelligence service is to warn that the circumstances are more complex than previously thought, that the very motivation of the enemy's behavior must be feared, and that the situation as a whole may develop in an undesirable direction. You need to have information. Having illusions in such matters leads to poor or even disastrous decisions. The task of the intelligence officer is to provide the government with information as it really is. But when you make decisions, it depends only on you, how objective and honest you are with yourself.

The work of spies includes stealing the secrets of dictators, terrorists and criminals. This is done using human or technical means and involves intrusion into personal correspondence or verbal communications. In this way, we give our intelligence officers the right to act in accordance with ethical standards that are different from those that we would like to see in everyday life. Such norms are justified by reducing the damage to society that can be achieved with such work [5] . Authoritarian states may well assume that their intelligence agencies will do without restraint and encourage their agents to do whatever they deem necessary to achieve their goals, regardless of compliance with laws or rules of conduct. In democracies, such behavior by agents will quickly undermine the credibility of both the government and the intelligence services. Consequently, intelligence activities are carefully regulated by domestic law to ensure that they remain necessary in scope and commensurate with the level of threats. So I'm making it clear that this book does not teach you how to spy on others and should not motivate you to do so. What I want to show, however, is the ways in which secret intelligence is based on ways of thinking that we can all benefit from. This book is a guide to right thinking, not a guide to bad behavior.

So I'm making it clear that this book does not teach you how to spy on others and should not motivate you to do so. What I want to show, however, is the ways in which secret intelligence is based on ways of thinking that we can all benefit from. This book is a guide to right thinking, not a guide to bad behavior.

Such thinking is not only dispassionate, cold-blooded calculation. "Negative ability" is how the poet John Keats described the writer's ability to pursue the vision of artistic beauty, even when it led to uncertainty, confusion and intellectual doubt in the process of creating a work. For analytical thinking, its equivalent is the ability to endure painful experiences and confusion from ignorance, and not the imposition of ready-made or universal solutions in ambiguous situations or emotional challenges [6] . In order to think clearly, we must have a scientific, evidence-based approach that nonetheless contains room for the "negative ability" needed to maintain open-minded thinking [7] .

Intelligence analysts like to look ahead, but they do not pretend to be predictors. There will always be unexpected results, no matter how hard we try to predict events with all diligence. The winner of the Grand National or the Indy 500 cannot be known in advance. Events sometimes develop in such a way that, as it seems to us, they are destined to confuse us. It is important to note that risk can also lead to the realization of certain opportunities - if, of course, we can use intelligence to overcome such risks.

Who am I?

The secret services prefer to remain silent about their successes in order to be able to repeat them, but the failures of the special services can become public knowledge. In the book, I have given examples of such successes and failures, along with several events from my own experience - more precisely, that part of it that is associated with the amazing development of the digital world. It's amusing when you remember that I started my first full-time job in 1965 in the mathematics department of an engineering company in Glasgow, where we learned how to write machine codes for early computers using five-character perforated paper tape to enter programs. Today, the mobile device in my pocket has direct access to more computing power than was available back in 1965 all over Europe. This digitization of our lives brings us great benefits, but it is also fraught with dangers, which will be discussed in Chapter 10 of this book.

Today, the mobile device in my pocket has direct access to more computing power than was available back in 1965 all over Europe. This digitization of our lives brings us great benefits, but it is also fraught with dangers, which will be discussed in Chapter 10 of this book.

In 1969, just after graduating from the University of Cambridge, I joined the Government Communications Centre, the UK intelligence agency responsible for the electronic intelligence and information security of government agencies and the army, where I learned about the pioneering work of the Center for the Application of Mathematics and Data Processing in intelligence activities. I abandoned my plans for a doctorate in theoretical economics and the temptation to become an economic adviser to Her Majesty's Treasury. Instead, I chose a career as a civil servant, which opened doors to the world of intelligence, defense, and national security. While serving in the Department of Defense as Assistant Chief of Staff for Military Policy, I used intelligence data to make recommendations to ministers and chiefs of staff. I worked three times in the private office of the Secretary of Defense (six ministers, to be exact - from Lord Carrington at 1973 to John Knott in 1981) and has repeatedly observed the heavy burden of decision-making in a crisis placed on the political leadership of the country. I've seen how good intelligence can be useful to a cause, and what problems its absence causes. When I worked as a UK Defense Adviser at NATO Headquarters in Brussels, it was clear to me how intelligence work shapes arms control and a nation's foreign policy. And as Assistant Undersecretary of Defense for Policy, I was an extremely voracious customer for operational intelligence on the crisis in the former Yugoslavia. In this capacity, I became a member of the UK Joint Intelligence Committee, the key intelligence-assessment unit of the Kingdom's Cabinet, in which I served for a total of seven years.

I worked three times in the private office of the Secretary of Defense (six ministers, to be exact - from Lord Carrington at 1973 to John Knott in 1981) and has repeatedly observed the heavy burden of decision-making in a crisis placed on the political leadership of the country. I've seen how good intelligence can be useful to a cause, and what problems its absence causes. When I worked as a UK Defense Adviser at NATO Headquarters in Brussels, it was clear to me how intelligence work shapes arms control and a nation's foreign policy. And as Assistant Undersecretary of Defense for Policy, I was an extremely voracious customer for operational intelligence on the crisis in the former Yugoslavia. In this capacity, I became a member of the UK Joint Intelligence Committee, the key intelligence-assessment unit of the Kingdom's Cabinet, in which I served for a total of seven years.

By the time I left the Department of Defense to return to the Government Communications Center as its director in the mid-1990s, computing had completely transformed the ability to process, store, and retrieve data on an unheard-of scale. I still remember how engineers triumphantly reported to me that they had managed to achieve stable storage of a terabyte of data with fast access - a big step at the time, although my small laptop today has only half the memory. More importantly, the Internet has become an important area of work for professionals, the World Wide Web has gained popularity, and the new Microsoft Hotmail service has made e-mail a fast and reliable form of communication. We knew that digital technologies would sooner or later permeate all areas of our lives and that organizations such as the Government Communications Center would have to radically change to cope with the challenges that arise as life and society become digital [8] .

I still remember how engineers triumphantly reported to me that they had managed to achieve stable storage of a terabyte of data with fast access - a big step at the time, although my small laptop today has only half the memory. More importantly, the Internet has become an important area of work for professionals, the World Wide Web has gained popularity, and the new Microsoft Hotmail service has made e-mail a fast and reliable form of communication. We knew that digital technologies would sooner or later permeate all areas of our lives and that organizations such as the Government Communications Center would have to radically change to cope with the challenges that arise as life and society become digital [8] .

The pace of digitalization has been faster than expected. In those years, smartphones had not yet been invented, and, naturally, there were no Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and other social media platforms and related applications. What was to become the Google search engine was at that time just a research project at Stanford University. During this small part of my working life, I saw how these and many other revolutionary achievements began to dominate our world. In less than 20 years, our economic, social and cultural priorities have come to depend on access to connected digital technologies and on learning to coexist safely with them. There is no way back.

During this small part of my working life, I saw how these and many other revolutionary achievements began to dominate our world. In less than 20 years, our economic, social and cultural priorities have come to depend on access to connected digital technologies and on learning to coexist safely with them. There is no way back.

When, in 1997, I was unexpectedly appointed as Permanent Under Secretary of State for the Home Office, this led to my close association with MI5 and Scotland Yard. These services used intelligence in investigations aimed at identifying and eliminating internal threats, including the activities of terrorist and organized crime groups. It was during this period that the Ministry of the Interior developed the Human Rights Law (1998) and legislation regulating and supervising the powers of the investigating authorities to ensure a permanent balance between our basic rights to life and security and the right to privacy in her personal and family sphere. . My career as Deputy Home Secretary was continued after the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 as the UK's first ever Security and Intelligence Coordinator. Back then, back at the UK Joint Intelligence Committee, I was responsible for keeping the British intelligence community running smoothly and developing the first UK counter-terrorism strategy, CONTEST, which is still active as of this writing in 2020.

Back then, back at the UK Joint Intelligence Committee, I was responsible for keeping the British intelligence community running smoothly and developing the first UK counter-terrorism strategy, CONTEST, which is still active as of this writing in 2020.

In this book, I offer you lessons from the world of intelligence, not only from within the intelligence service itself, but also from the perspective of a politician as an intelligence user. I have learned the hard way that intelligence is hard to come by, always fragmented and incomplete, and sometimes erroneous. But if you work with them consistently and with an understanding of the limitations of the information contained in them, then their significant role and benefit for ensuring the safety of society becomes obvious. The exact same is true for you.

BOOV: A Method of Analytical Thinking

I am currently an adjunct professor of intelligence at the Department of Military Studies at King's College London, at the Institute of Political Studies in Paris, and at the Defense University of Oslo. It's been my experience that having a methodology to review the decision making process and establish an appropriate level of trust in them really helps. The methodology I have developed - let me call it the abbreviation VOOV - is based on four types of information processing that allow you to form an intellectual product obtained at different levels of analysis:

It's been my experience that having a methodology to review the decision making process and establish an appropriate level of trust in them really helps. The methodology I have developed - let me call it the abbreviation VOOV - is based on four types of information processing that allow you to form an intellectual product obtained at different levels of analysis:

● Mastery of the situation: what is happening and what we are facing right now.

● An explanation of why we see what we see and the motivations of those involved in the current event.

● Estimates and forecasts of the development of an event under various circumstances.

● Development of a strategic notification of problems that may arise in the long term.

There is a powerful logic behind this fourfold way of thinking, the BOOB methodology.

Take as an example an investigation into an attack by far-right extremists. The first step is to find out as precisely as possible what is going on. As a starting point, the police will gather information about known crimes, interview witnesses, and obtain forensic evidence. Nowadays, there is also a fair amount of information available on social networks and the Internet, but the credibility of such sources requires careful verification. In fact, even well-verified facts can be interpreted in completely different ways, which can lead to erroneous exaggeration or underestimation of the problem under investigation.

As a starting point, the police will gather information about known crimes, interview witnesses, and obtain forensic evidence. Nowadays, there is also a fair amount of information available on social networks and the Internet, but the credibility of such sources requires careful verification. In fact, even well-verified facts can be interpreted in completely different ways, which can lead to erroneous exaggeration or underestimation of the problem under investigation.

We need to add meaning to the actions of the extremists so that we can explain what is really going on. We do this in the second phase of SBIA by constructing a better explanation of the actions that is consistent with the available evidence and understanding of the motives of the individuals involved. We see this process in every criminal court, when attorneys for the prosecution and defense offer their versions of the truth to the jury. For example, why are the accused's fingerprints on fragments of a beer bottle used to make a Molotov cocktail? Did he throw the bottle himself, or was the bottle taken from the dustbin of his house by a mob looking for materials to make weapons? The court is required to verify these facts, and then the jury must choose the explanation that they think best fits the available evidence. Facts rarely speak for themselves. At the second stage, in the case of an investigation of an attack by extremists, we must come to an understanding of the reasons that unite such people. We will understand what drives their anger and hatred. This will provide us with an explanatory model that will allow us to proceed to the third stage of WWII, in which we can assess how the situation may change over time - perhaps after a wave of arrests and successful prosecutions of extremist leaders by the police. We will also be able to assess how likely it is that arrests and convictions will lead to a reduction in the threat of violence and the anxiety of society as a whole. This third step provides the intelligence base for evidence-based policy decisions.

Facts rarely speak for themselves. At the second stage, in the case of an investigation of an attack by extremists, we must come to an understanding of the reasons that unite such people. We will understand what drives their anger and hatred. This will provide us with an explanatory model that will allow us to proceed to the third stage of WWII, in which we can assess how the situation may change over time - perhaps after a wave of arrests and successful prosecutions of extremist leaders by the police. We will also be able to assess how likely it is that arrests and convictions will lead to a reduction in the threat of violence and the anxiety of society as a whole. This third step provides the intelligence base for evidence-based policy decisions.

The SBIA methodology has a critical fourth component, the development of a strategic notification about events in the long term. For our example, we could consider the further growth of extremist movements elsewhere in Europe or the evolution of such groups in the event of major changes in the patterns of refugee movements as a result of new regional conflicts or due to climate change. This is just one example, but there are many other situations where anticipation of future events is of great importance, as it allows us to intelligently prepare for the future.

This is just one example, but there are many other situations where anticipation of future events is of great importance, as it allows us to intelligently prepare for the future.

The BOOB four-part methodology can be applied to any situation that concerns us, as long as we want to understand what happened and why, and what might happen next, from stressful situations at work to losing your sports team. The SBIA methodology is applicable to any situation where you have current information and want to make a decision about how best to act on it.

We should not be surprised to find patterns in the various types of errors inherent in working on each of the four components of the BOOB process. For example:

● Mastery of the situation depends on the difficulty of assessing what is happening at the moment. The presence of gaps in information is real and often causes a reluctance to change one's mind after receiving new facts.

● Our explanations suffer from a poor understanding of other people: their motivations, upbringing, culture and background.

● Estimates of the development of events can be thrown off by unexpected changes in situations that were not taken into account in the forecast.

● Strategic achievements are often overlooked due to being too narrowly focused and the analyst's lack of imagination about the future.

The four-part methodology for assessing a situation is applicable not only in public affairs. At its core, it contains a call for rationality in the entire course of our thinking. Our choice, even between unpleasant alternatives, will be more logical as a result of adopting methodical ways of thinking. Such ways of thinking contain the ability to distinguish what we know from what we don't know and from what we assume to be probable. This kind of thinking requires integrity.

In Buddhism there is a notion that there are three poisons that cripple the mind: anger, attachment and ignorance [9] . We must be aware that strong emotions, such as anger, can distort our perception of what is true and what is false. Attachment to old, comfortable ideas that give us hope that the world is predictable can make us blind to emergencies. This is what allows us to be taken by surprise. Still, ignorance is the most destructive poison for the mind. And the goal of intellectual analysis is to eliminate this ignorance and develop our ability to make intelligent decisions so that we can make better choices in everyday life.

Attachment to old, comfortable ideas that give us hope that the world is predictable can make us blind to emergencies. This is what allows us to be taken by surprise. Still, ignorance is the most destructive poison for the mind. And the goal of intellectual analysis is to eliminate this ignorance and develop our ability to make intelligent decisions so that we can make better choices in everyday life.

On that fateful day in March 1982, Margaret Thatcher immediately realized what the intelligence was telling her. She understood what the Argentine junta was planning and what the possible consequences of these plans for her as British Prime Minister. Her words demonstrated the ability to use this understanding: “I must contact President Reagan immediately. Only he can convince Galtieri [General Leopoldo Galtieri, leader of the junta] to stop this madness.” I was authorized to ensure that the latest intelligence from the Government Communications Center was passed on to the American authorities, including the presidential administration. The British government quickly prepared a personal message from Thatcher to Reagan, asking him to speak with Galtieri and obtain confirmation that he would not give permission for Argentine landings in the Falklands, let alone military action, and a warning that the UK would not turn a blind eye to such an invasion. . But the Argentine junta ignored Reagan's request for talks with Galtieri and did nothing about it until the invasion could no longer be cancelled.

The British government quickly prepared a personal message from Thatcher to Reagan, asking him to speak with Galtieri and obtain confirmation that he would not give permission for Argentine landings in the Falklands, let alone military action, and a warning that the UK would not turn a blind eye to such an invasion. . But the Argentine junta ignored Reagan's request for talks with Galtieri and did nothing about it until the invasion could no longer be cancelled.

But the full-scale Argentine invasion and military occupation of the islands took place only two days later, on April 2, 1982. There was only a small detachment of the Royal Marines on the islands, and only the lightly armed ice reconnaissance ship Endurance operated in their area. Effective resistance to the enemy was impossible. The islands were too far away for naval reinforcements to arrive within two days, and the only airport did not have a runway capable of receiving long-range military transport aircraft.

We lacked adequate knowledge of the situation in terms of our intelligence's knowledge of the plans of the Argentine junta. We failed to understand the facts at our disposal, and therefore could not predict how events would develop. Moreover, over the years we have not been able to get strategic notice that such a situation could ever arise, and therefore we have not taken steps that could have prevented an Argentine invasion of the Falklands. These were failures at each of the four stages of the BOOV methodology.

We failed to understand the facts at our disposal, and therefore could not predict how events would develop. Moreover, over the years we have not been able to get strategic notice that such a situation could ever arise, and therefore we have not taken steps that could have prevented an Argentine invasion of the Falklands. These were failures at each of the four stages of the BOOV methodology.

All lessons to be learned.

Structure of this book

The four chapters of the first part of this book are devoted to the above-mentioned BOIA methodology. Chapter 1 describes how we can take control of the situation and check our sources of information. Chapter 2 is about causation and the interpretation of a situation, and how a mathematical technique called Bayesian inference allows us to use new information to change the degree of confidence in our chosen hypothesis. Chapter 3 explains the process of generating estimates and forecasts. Chapter 4 describes the long-term benefit of strategic event notification.

There are lessons to be learned from these four stages of analysis:

1. 1 Jerome K. Jerome. Should we say what we think and think what we say? // Selected works in 2 volumes. - M .: GIHL, 1957. - T. 2.

2. 2 The history of these radio interceptions and the decision to set up a task force to recapture the Falklands is detailed in the official history of the Falklands Campaign by Sir Lawrence Freedman and in the memoirs of Sir John Knott and Admiral Sir Henry Leach, First Sea Lord of the time. Lawrence Freedman. The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, vol. 1. London, Routledge, 2005, ch. 19. John Nott. Here Today, Gone Tomorrow. London, Politico, 2002. Henry Leach. Endure No Makeshifts. London, Pen and Ink Books, 1993.

3. 3 One of the best summaries of the nature and use of classified intelligence is found in Chapter 1 of the Butler report on intelligence failures prior to the 2003 invasion of Iraq. This was written by Investigative Advisor, the late Peter Freeman, my former senior colleague at the UK Government Communications Centre. Robin Butler. Review of Intelligence on Weapons of Mass Destruction. London, HMSO, 2004, ch. 1

Robin Butler. Review of Intelligence on Weapons of Mass Destruction. London, HMSO, 2004, ch. 1

4.4 In the official language of the Joint Intelligence Committee, it is "the process of obtaining known information about situations and objects of strategic, operational or tactical significance and characterizing known and future actions in such situations."

5.5 The ethics of secret intelligence is the subject of a dialogue between political scientist Professor Mark Fithian and myself, as a former practitioner, in our book below. David Omand, Mark Phythian. Principled Spying. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2018.

6.6 In psychology, a specific personality trait is studied, which characterizes the ability of a person to endure ignorance of important life circumstances without suffering and anxiety - tolerance for uncertainty. – Hereinafter, except for specially noted footnotes, approx. scientific ed.

7.7 I am using the term "negative capacity" here in the sense that the 20th-century British psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion coined Keats's term to illustrate the attitude of openness of mind and the ability to dwell in uncertainty, which he considered central not only to the psychoanalytic session, but also to in life itself. Diana Voller. "Negative Capability". Contemporary Psychotherapy, vol. 2, no. 2, 2010.

Diana Voller. "Negative Capability". Contemporary Psychotherapy, vol. 2, no. 2, 2010.

8.8 A description of the problems faced by British intelligence at that time can be found in the two books below. Richard Aldrich. GCHQ. London, Harper Press, 2010, ch. 24. John Ferris. Behind The Enigma. London, Bloomsbury, 2020.

9.9 Ringu Tulku Rinpoche. Living without Fear and Anger. Oxford, Bodhicharya, 2005.

Read the book Target Thinking. Decision-Making According to the Methods of the British Intelligence Services» online in full📖 — David Omand — MyBook.

Translator Vsevolod Baronin

Scientific editor Denis Bukin , psychologist, psychotherapist, author of the book “Development of memory by special services”

Editor Oksana Puchnina

Editor -in -chief S. Turko 9000

Art director Yu. Buga

Cover design D. Izotov

Proofreader E. Chudinova

Computer proofing A. Abramov

Abramov

Cover illustration shutterstock.com

© David Omand, 2020

The author has asserted his rights

All rights reserved

Original English edition Bookin Ltd

© Edition in Russian, translation, design. Alpina Publisher LLC, 2022

All rights reserved. This e-book is intended solely for private use for personal (non-commercial) purposes. The e-book, its parts, fragments and elements, including text, images and others, may not be copied or used in any other way without the permission of the copyright holder. In particular, such use is prohibited, as a result of which an electronic book, its part, fragment or element becomes available to a limited or indefinite circle of persons, including via the Internet, regardless of whether access is provided for a fee or free of charge.

Copying, reproduction and other use of an e-book, its parts, fragments and elements, beyond private use for personal (non-commercial) purposes, without the consent of the copyright holder is illegal and entails criminal, administrative and civil liability.

* * *

Dedicated to Keira, Robert, Beatrice and Ada

in the hope that they will grow up in a better world

Foreword by Science Editor

This is a book about the art of thinking. Logic is a wonderful science, it gives the laws of strict, unmistakable and impeccable thinking. But life rarely provides enough information for impeccable logical conclusions. It is easy to talk about abstract things without having to do anything. In real life, when there is neither clarity nor time to clarify the facts, and circumstances force you to act, you have to rely on what is - conditionally reliable information. David Omand has lived the life of an intelligence official, in which it is not customary to answer “I don’t know,” so he rightfully shares his practical ability to build a picture of several pieces of the puzzle. Using his approaches, you can “wash” a good result from an unreliable information breed. Yes, at times you will be mistaken, but you will be able to act, and that's fine.

We have few books on methods of thinking, especially those related to intelligence. The last similar one, Washington Platt's Strategic Intelligence Information Work, was published in Russian back in 1958, and it is still recommended in specialized educational institutions to this day. At the same time, books on the work of an intelligence analyst are published regularly in English. Perhaps we are hindered by the excessive tendency of the domestic military departments to classify everything in the world, including the old, irrelevant and even known to everyone. Without a solid texture, writing a book will not work, and a fictional texture is unconvincing. Well, as long as there are no domestic books, we will read translated ones.

And one more thing. As I edited this book, I often thought of Jerome K. Jerome: “In war, the soldiers of every country are always the bravest in the world. The soldiers of a hostile country are always treacherous and treacherous - that's why they sometimes win" [1] . In other cases, patriotism is an excellent virtue, but it is hardly good in intelligence, where independence of mind is much more valuable. There is no unity of interests between the various intelligence services of the country, just as there is none within the intelligence service, nor within its smallest subdivision. Deeds are determined not by organizations, but by a bizarre interaction of multidirectional interests of influential people, and these interests do not always consist in selfless service to the fatherland. Undoubtedly, any smart intelligence officer (and others in high positions are inappropriate) understands this, but will he openly write about it? Only sometimes, between the lines. And in other cases - to demonstrate ardent confidence in the correctness of the "good guys". Fortunately, fiction writers write about human ups and downs in intelligence. I am sure it will be easier to understand what is written here between the lines, recalling at times the novels of John Le Carré or the films based on these novels: The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965) and "Spy, get out!" (2011).

In other cases, patriotism is an excellent virtue, but it is hardly good in intelligence, where independence of mind is much more valuable. There is no unity of interests between the various intelligence services of the country, just as there is none within the intelligence service, nor within its smallest subdivision. Deeds are determined not by organizations, but by a bizarre interaction of multidirectional interests of influential people, and these interests do not always consist in selfless service to the fatherland. Undoubtedly, any smart intelligence officer (and others in high positions are inappropriate) understands this, but will he openly write about it? Only sometimes, between the lines. And in other cases - to demonstrate ardent confidence in the correctness of the "good guys". Fortunately, fiction writers write about human ups and downs in intelligence. I am sure it will be easier to understand what is written here between the lines, recalling at times the novels of John Le Carré or the films based on these novels: The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965) and "Spy, get out!" (2011).

Denis Bukin

Foreword

Why We Need These Lessons: In Search of Independence of Thought, Honesty and Integrity

Westminster, March 1982. "This is very serious, isn't it?" asked Margaret Thatcher. She frowned and looked up from the intelligence reports I had given her. “Yes, Prime Minister,” I replied, “this information can be interpreted unequivocally: the Argentine junta is in the final stages of preparations for an invasion of the Falkland Islands. It is highly probable that the invasion will take place next Saturday.”

This conversation took place on the afternoon of Wednesday, March 31, 1982.

I was Chief Private Secretary to Secretary of Defense John Knott. We were sitting in his office in the House of Commons preparing for a speech in parliament when a liaison officer from military intelligence headquarters hurried into the government building. In his mail bag were several very conspicuously designed folders. From the red diagonal crosses on their dark covers, I immediately knew that they contained top secret material covered with a special code word UMBRA, meaning that they came from the Government Communications Center.

From the red diagonal crosses on their dark covers, I immediately knew that they contained top secret material covered with a special code word UMBRA, meaning that they came from the Government Communications Center.

These folders contained decrypted radio intercepts from the Argentine navy. Reports said that an Argentine submarine was conducting covert reconnaissance near the capital of the Falkland Islands, the city of Stanley, and that the Argentine navy, which was on the exercises, was re-forming itself into battle formation. Another, more recent radio intercept mentioned an Argentine Navy task force that was due to arrive at an unspecified location early Friday, April 2. After analyzing the coordinates of the ships of this formation, the government communications headquarters came to the conclusion that only Port Stanley could be the target of the Argentines [2] .

John Knott and I looked at each other with one single thought: the loss of the Falklands would pose the gravest threat to the existence of Margaret Thatcher's government: therefore, the Prime Minister must be immediately informed of these radio intercepts. We hurried down the corridor to her office and literally burst into it.

We hurried down the corridor to her office and literally burst into it.

The latest analysis the Prime Minister received from the UK Joint Intelligence Committee was that Argentina was unwilling to use military force to secure its claim to the sovereignty of the Falkland Islands. However, the Joint Intelligence Committee warned that if the British took extremely provocative action against Argentine citizens who had illegally landed on the British island of South Georgia in the South Atlantic, the junta could use this as a pretext to start hostilities. Since Britain had no intention of provoking the junta, such an assessment was misinterpreted in Whitehall as encouraging, which made the fresh intelligence all the more stunning. This was the first sign that the Argentine junta was ready to use military force to impose its demands.

The Importance of Reasoning

The shock of how the UK suddenly became involved in the Falklands Crisis is deeply ingrained in my memory. The situation showed me how important errors in our thinking can be. This is as true in the lives of individuals as it is in the administration of public affairs. And my goal in writing this book is ambitious: I want to empower people to make better decisions based on the way intelligence analysts think. I will bring lessons from our past to show exactly how one can know, explain and predict most of all the events that we face in our absolutely amazing age.

The situation showed me how important errors in our thinking can be. This is as true in the lives of individuals as it is in the administration of public affairs. And my goal in writing this book is ambitious: I want to empower people to make better decisions based on the way intelligence analysts think. I will bring lessons from our past to show exactly how one can know, explain and predict most of all the events that we face in our absolutely amazing age.

There are important life lessons to be learned from observing how intelligence analysts think. By studying their actions during problem solving in real situations in recent history, we learn how they organize their thoughts, distinguish between the probable and the improbable, and thus draw better conclusions. We will learn how to methodically test alternative explanations for what is happening and assess how much we need to change our own opinion as new information becomes available to us. We will try to understand how our own feelings, as well as the opinions of members of a particular community, can influence our judgments. We will also learn how one can fall prey to conspiracy thinking and be deceived through deliberate misinformation.

We will also learn how one can fall prey to conspiracy thinking and be deceived through deliberate misinformation.

We all face decision-making and choice processes, whether at home, at work or at play. But today, compared with the old days, we have negligibly little time to make a decision. We live in the digital age and are bombarded with conflicting, false and confusing information from a vast array of sources - more than ever. Information surrounds us from all sides, and we feel obliged to respond to it at the same speed with which it comes to us. There are powerful forces playing against us through messages and opinions spread through social media. We find ourselves overwhelmed by all this information and ask ourselves the question: have we become more or less ignorant than in former times? Today we need these lessons from the past, more than ever.

Looking over the shoulder of an intelligence analyst

In the history of the art of war, it has become clear to commanders the advantage that intelligence can provide.

Governments today are deliberately creating specialized services to access and analyze information that can help them make better decisions [3] . The Secret Intelligence Service of the British Foreign Office (MI6) oversees the work of intelligence agents abroad. Security Services (MI5) and its law enforcement partners investigate domestic threat situations and monitor suspects. The Government Communications Center is engaged in the interception of radio and electronic communications and the collection of digital intelligence. The military has its fair share of intelligence-gathering operations abroad, including photo reconnaissance from satellites and unmanned aerial vehicles. The task of the intelligence analyst is to piece together all the pieces of information received. Analysts are then identified with situation assessments designed to raise awareness among decision makers. They figure out what is happening, explain why it is happening, and describe how the situation might develop [4] .

The more we understand the nature of the decisions we must make, the less likely we are to misinterpret the facts, make bad choices, or be seriously surprised by the outcome. Much of what we need can be obtained from open sources, but only if we are careful enough to critically judge the quality of the information.

Being informed by the decision maker does not necessarily mean simplifying the situation. Often the assessment coming from the intelligence service is to warn that the circumstances are more complex than previously thought, that the very motivation of the enemy's behavior must be feared, and that the situation as a whole may develop in an undesirable direction. You need to have information. Having illusions in such matters leads to poor or even disastrous decisions. The task of the intelligence officer is to provide the government with information as it really is. But when you make decisions, it depends only on you, how objective and honest you are with yourself.

The work of spies includes stealing the secrets of dictators, terrorists and criminals. This is done using human or technical means and involves intrusion into personal correspondence or verbal communications. In this way, we give our intelligence officers the right to act in accordance with ethical standards that are different from those that we would like to see in everyday life. Such norms are justified by reducing the damage to society that can be achieved with such work [5] . Authoritarian states may well assume that their intelligence agencies will do without restraint and encourage their agents to do whatever they deem necessary to achieve their goals, regardless of compliance with laws or rules of conduct. In democracies, such behavior by agents will quickly undermine the credibility of both the government and the intelligence services. Consequently, intelligence activities are carefully regulated by domestic law to ensure that they remain necessary in scope and commensurate with the level of threats. So I'm making it clear that this book does not teach you how to spy on others and should not motivate you to do so. What I want to show, however, is the ways in which secret intelligence is based on ways of thinking that we can all benefit from. This book is a guide to right thinking, not a guide to bad behavior.

So I'm making it clear that this book does not teach you how to spy on others and should not motivate you to do so. What I want to show, however, is the ways in which secret intelligence is based on ways of thinking that we can all benefit from. This book is a guide to right thinking, not a guide to bad behavior.

Such thinking is not only dispassionate, cold-blooded calculation. "Negative ability" is how the poet John Keats described the writer's ability to pursue the vision of artistic beauty, even when it led to uncertainty, confusion and intellectual doubt in the process of creating a work. For analytical thinking, its equivalent is the ability to endure painful experiences and confusion from ignorance, and not the imposition of ready-made or universal solutions in ambiguous situations or emotional challenges [6] . In order to think clearly, we must have a scientific, evidence-based approach that nonetheless contains room for the "negative ability" needed to maintain open-minded thinking [7] .

Intelligence analysts like to look ahead, but they do not pretend to be predictors. There will always be unexpected results, no matter how hard we try to predict events with all diligence. The winner of the Grand National or the Indy 500 cannot be known in advance. Events sometimes develop in such a way that, as it seems to us, they are destined to confuse us. It is important to note that risk can also lead to the realization of certain opportunities - if, of course, we can use intelligence to overcome such risks.

Who am I?

The secret services prefer to remain silent about their successes in order to be able to repeat them, but the failures of the special services can become public knowledge. In the book, I have given examples of such successes and failures, along with several events from my own experience - more precisely, that part of it that is associated with the amazing development of the digital world. It's amusing when you remember that I started my first full-time job in 1965 in the mathematics department of an engineering company in Glasgow, where we learned how to write machine codes for early computers using five-character perforated paper tape to enter programs.