Speak lexile level

Speak - Booksource

Despite global supply chain issues, Booksource is making sure customers get their book orders. Click to learn more.

See larger image

Speak

ISBN-10: 1250302358

ISBN-13: 9781250302359

Author: Anderson, Laurie Halse

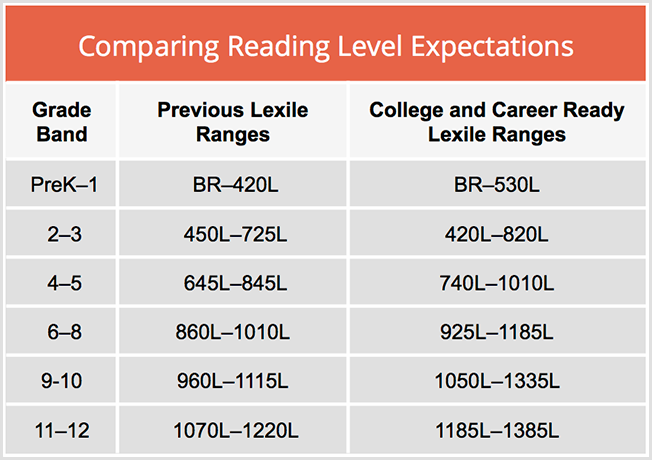

Interest Level: 7-12

Publisher: Square Fish

Publication Date: January 2019

Copyright: 1999

Page Count: 224

(Be the first to review)

Paperback

$8. 24

Quantity

Up Down

Add to Wish List Icon Add to Cart

Interest Level

Grades 7-12

Reading Level

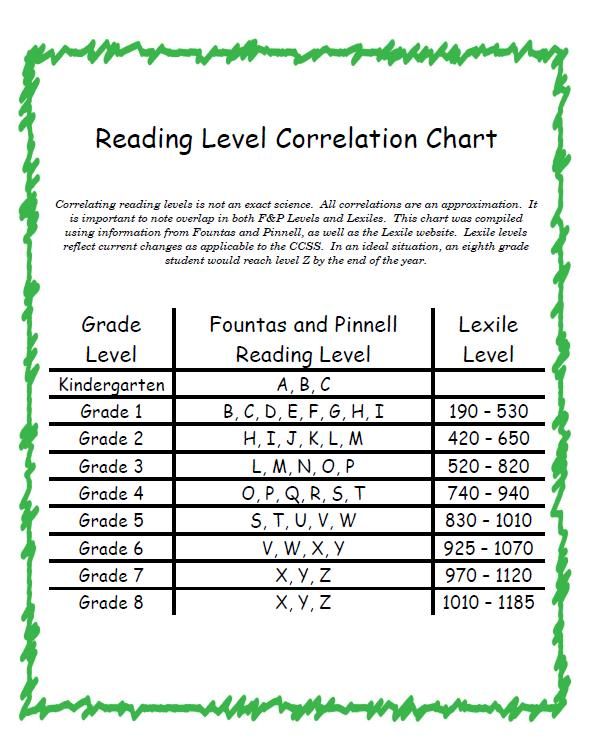

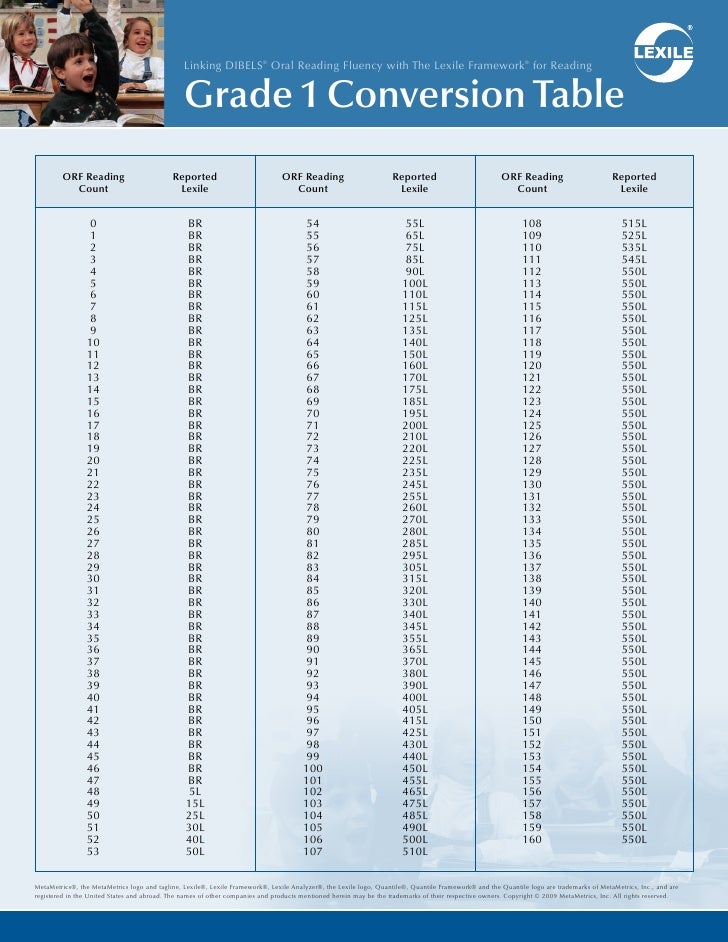

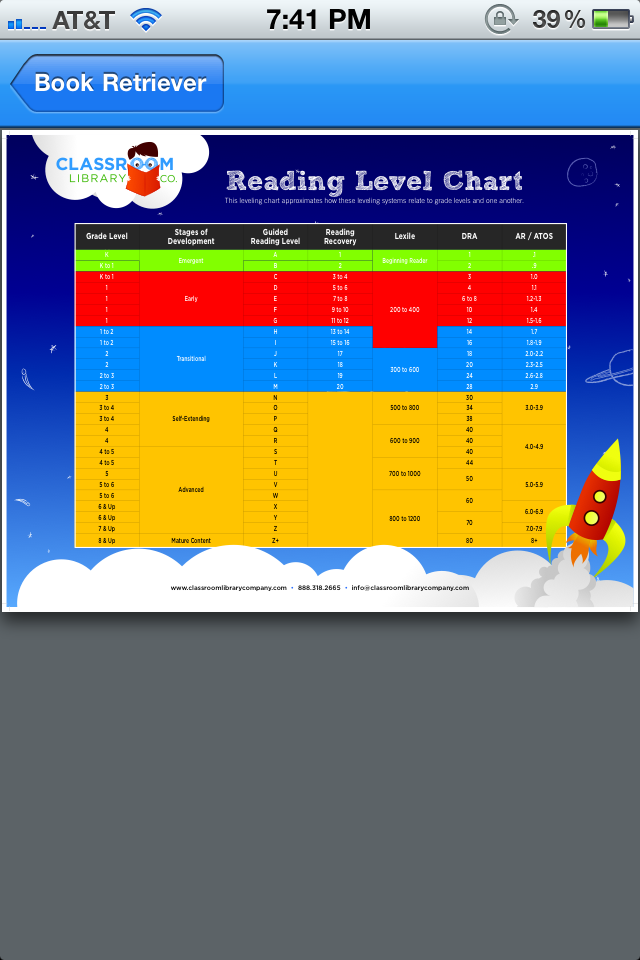

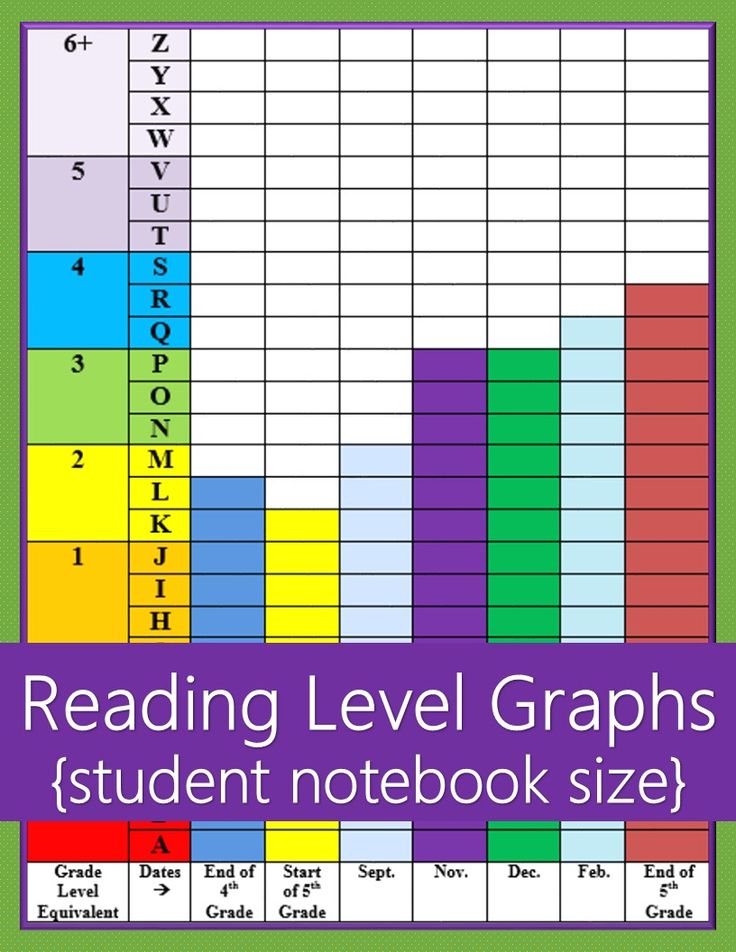

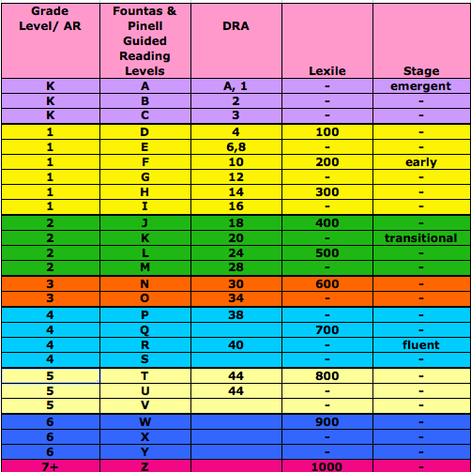

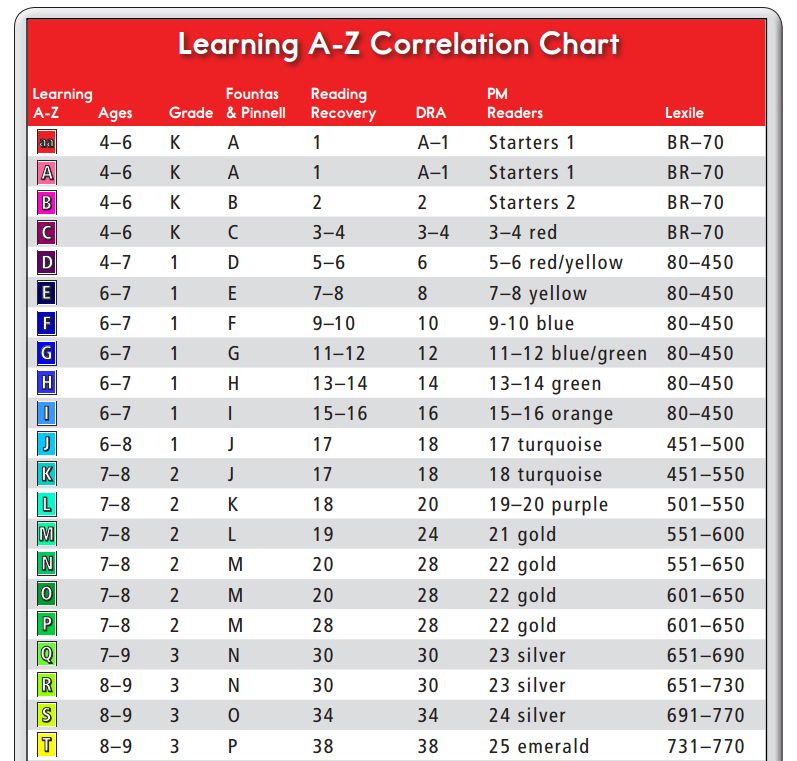

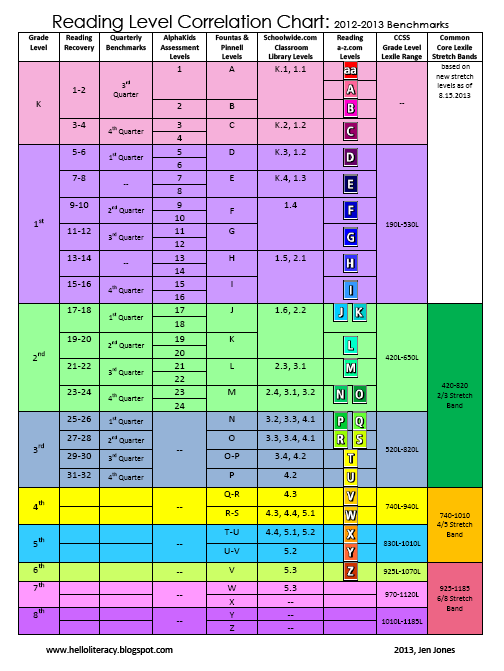

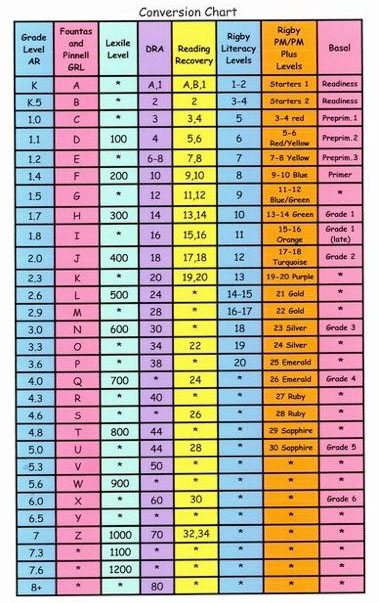

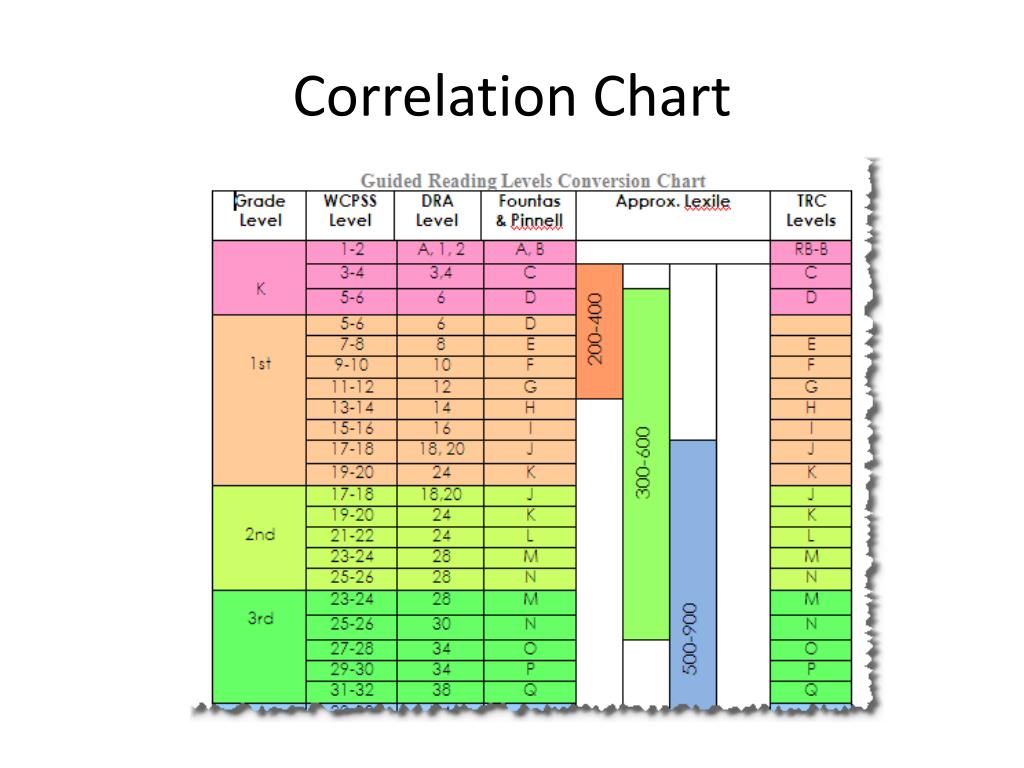

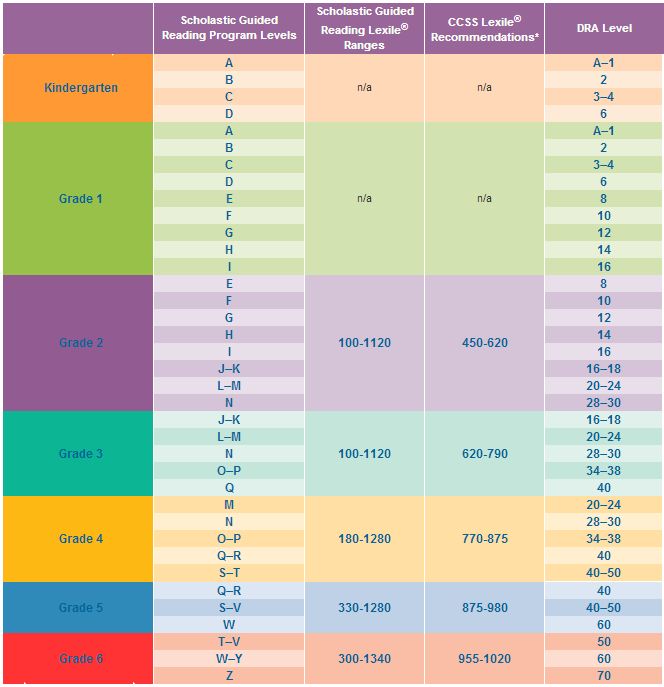

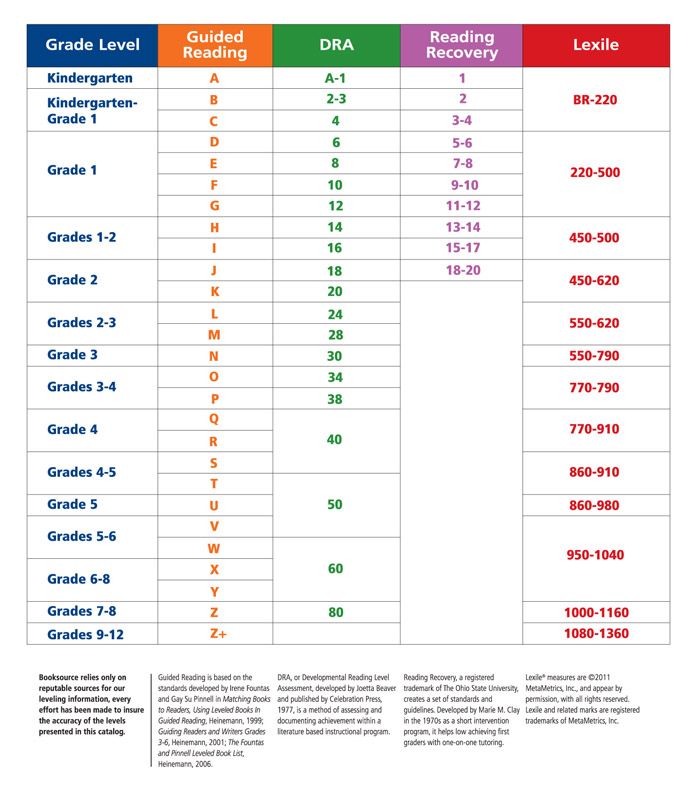

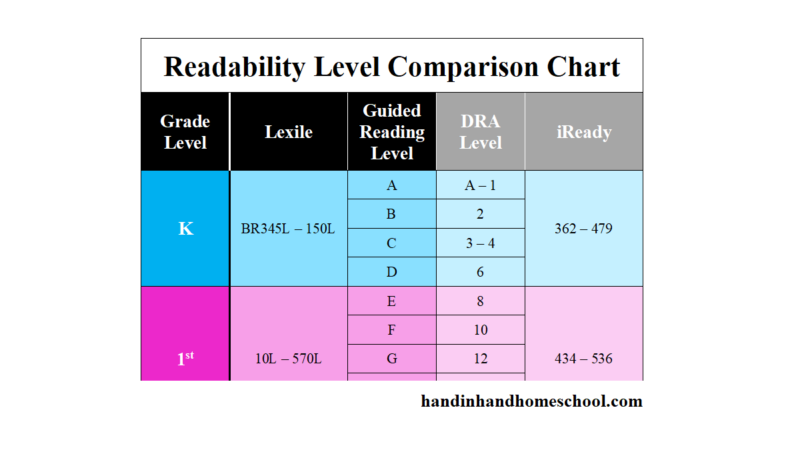

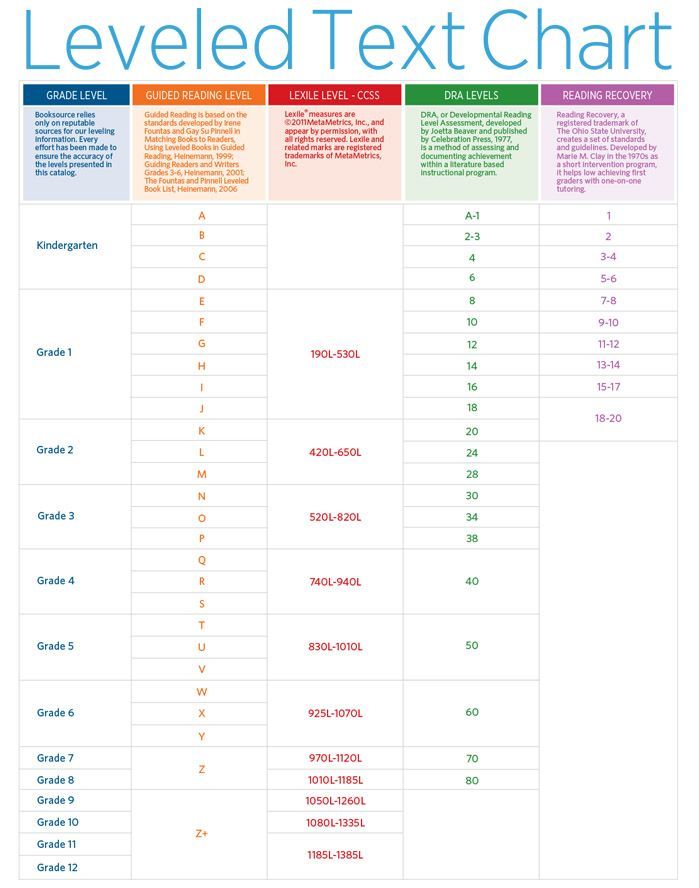

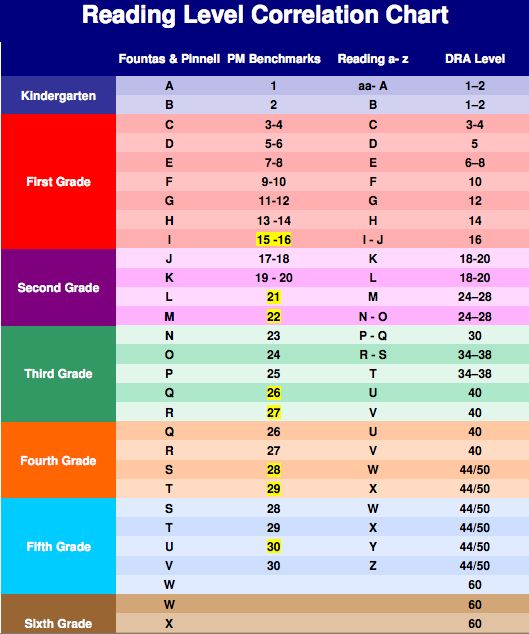

Guided Reading: Z

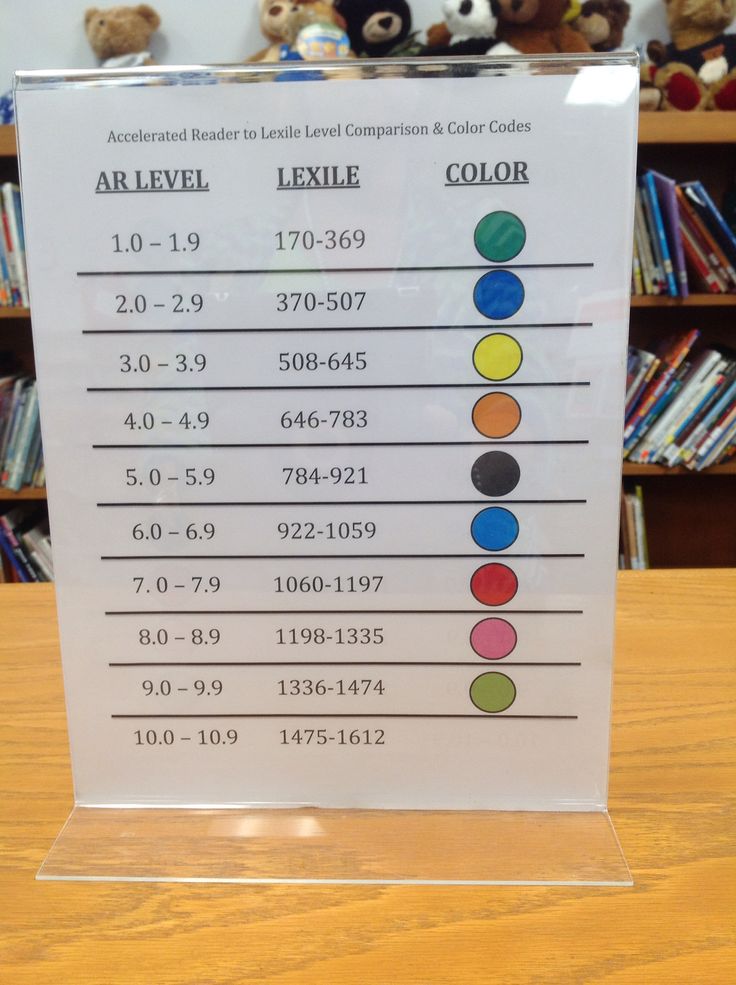

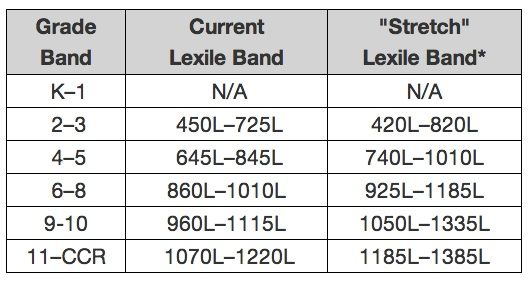

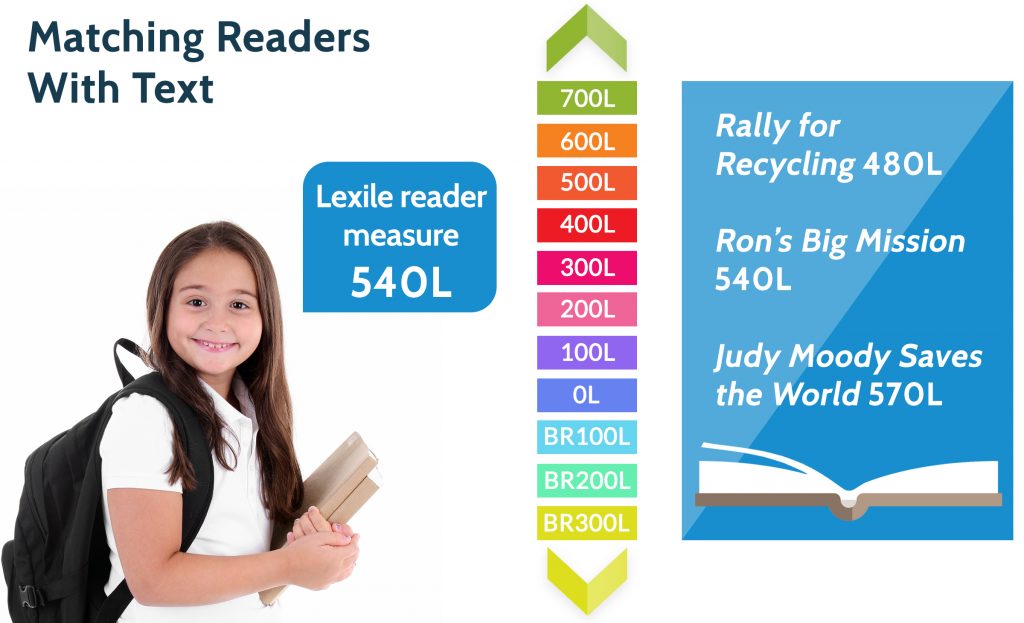

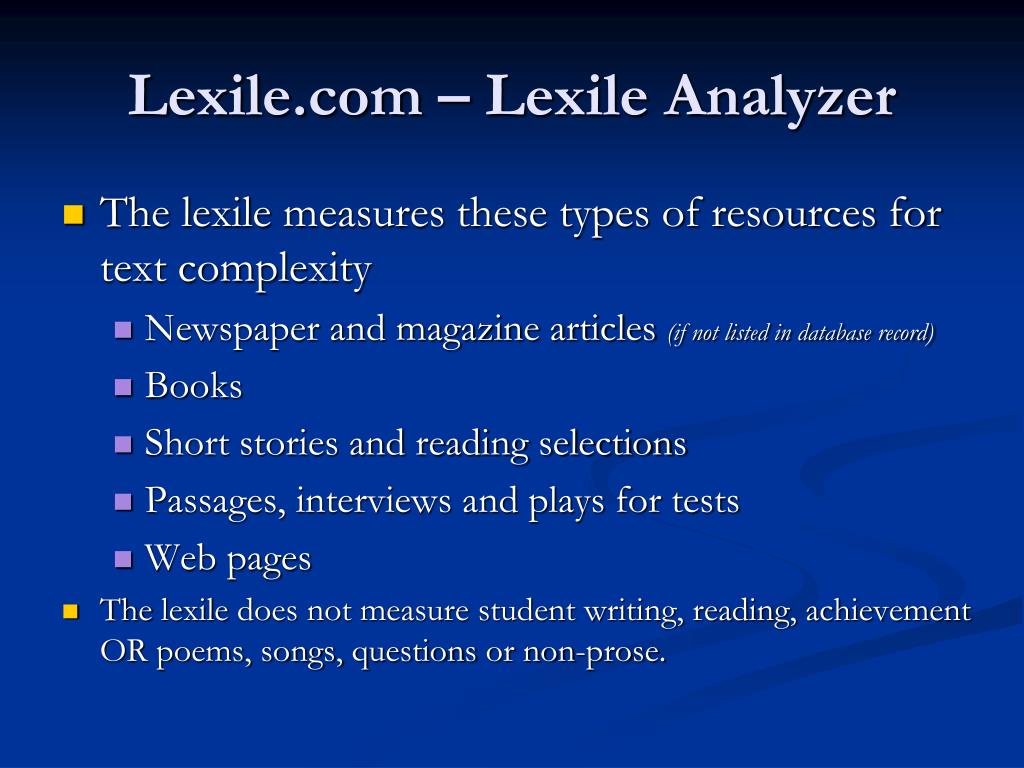

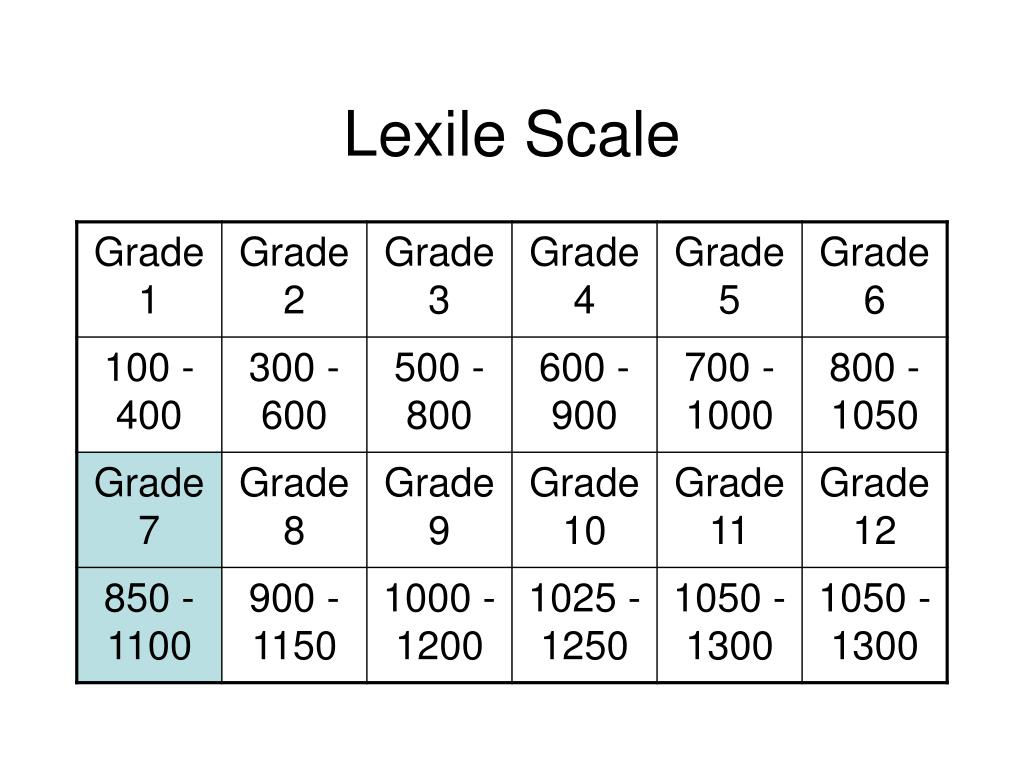

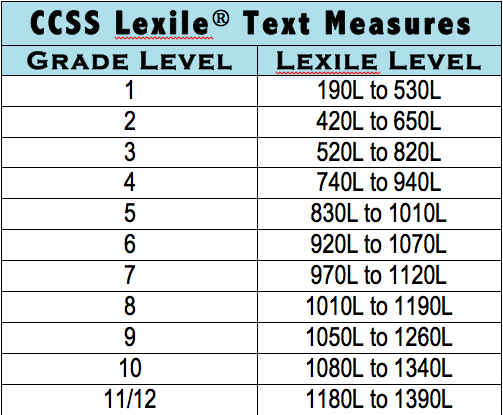

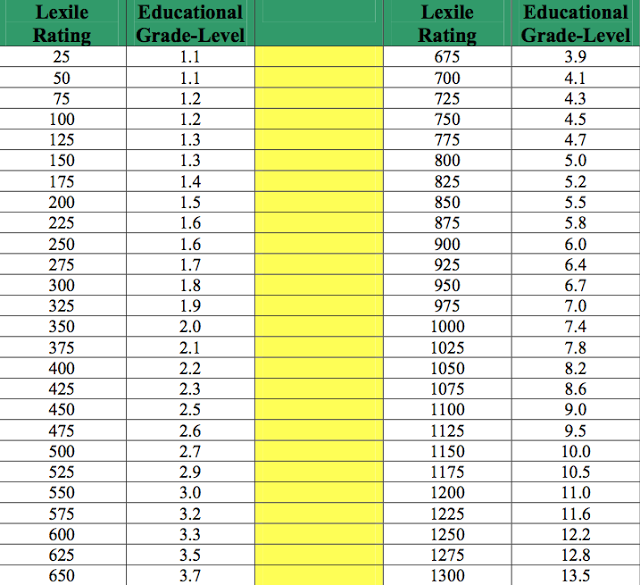

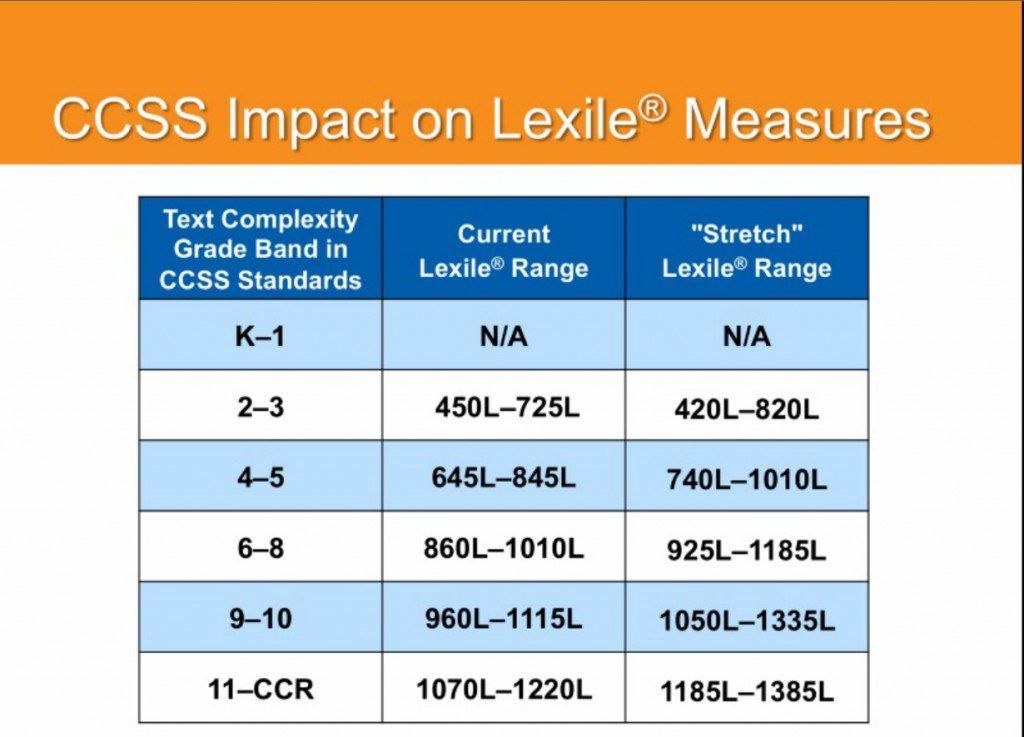

Lexile: 690L

Accelerated Reader Level: 4.5

Accelerated Reader Points: 7.0

Grade Level Equivalent: 6

Booksource Subjects

Chapter Book

Mature Subject Matter

Realistic Fiction

Sexual Assault and Abuse

Social Issues

Striving Reader Recommendation

BISAC Subjects

YOUNG ADULT FICTION / Social Themes / General (see also headings under Family) *

Description

A violent event near the end of the summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman year in high school. Unable to discuss her trauma with anyone, Melinda sinks further into depression and becomes selectively mute.

Unable to discuss her trauma with anyone, Melinda sinks further into depression and becomes selectively mute.

Other Formats Available

Hardcover

List Price: $19.99

Your Price: $14.99

Quantity

Up Down

Icon Add to Cart

Complete Expanded Library Grade 8

Complete Leveled Library Grade 8 (U-Z)

Complete Leveled Library Grade 8 (U-Z)

Complete Starter Grade 8 Library

Expanded Library Series & Favorite Authors Grade 8

View More

Speak Book Review | Common Sense Media

A Lot or a Little?

The parents' guide to what's in this book.

What Parents Need to Know

Parents need to know that this National Book Award finalist is about a girl traumatized by a rape (and is then isolated from her peers). Wounded, silent Melinda ditches class, steals passes from teachers, and deliberately cuts herself. Accurate descriptions of the minutiae of high school will appeal to any teen who has felt like an outsider, and when Melinda is finally able to speak, readers will rejoice in her triumphs. This is a gritty, powerful book that teachers and parents could use to launch a number of discussions. Readers must meld short descriptive passages to form the narrative.

Community Reviews

lizd6396 Adult

September 25, 2019

age 14+

Word choices

This book is pretty negative. There are very few redeeming characters. The main character has been raped and that frames her narrative. The words 'spaz' and 'retarded' are used more than once and it feels like lazy writing.

CSMContentDefault Adult

November 5, 2018

age 12+

boring with no new messege

The book “Speak” by Laurie Halse Anderson had its ups and downs. Anderson’s did an excellent job with making the language simple, as most teenagers would like. She also succeeded with the moral of the story, it served a great importance. Rape is a sensitive content to the author since it also happened to her when she was a teenager, and it was inspiring that she portrayed it to a story. As Melinda, the main character felt like an outcast, she couldn’t help but go through depression, anxiety, and loss of hope; That’s where the downfall in my opinion was. The author wanted teenagers to read it in order to raise awareness, but I feel like it also tried to say that throughout everything that brings you down, you will go through wild pain. I felt like if the character was stronger it would’ve motivated teenagers to be like the character. If the character didn’t lose hope and tried pushing forward it would’ve had a greater moral. At the end of the book, the character speaks up for herself, which is the highlight of the book, but I still think she went through so much sensitive content that teenagers shouldn’t be thinking about it. In my opinion, the book was stereotypical, Melinda was shy, weak and quite, something happens to her, she changes. What if a strong person goes through something tough? Maybe that would’ve been different. There are some points of the book were the readers wanted her to be defensive, as kids were laughing at her, it was a need for her to respond, but she didn’t. On the other hand, the character should go through a dark time after what happened, although I feel like she didn’t persevere through it as much as readers wanted to see happen. This book explained highschool the wrong way, it makes parents worried about their children. Most high schools don’t really care about how you look, everyone studies and go home, in my opinion, it was a little exaggerated and unrealistic.

If the character didn’t lose hope and tried pushing forward it would’ve had a greater moral. At the end of the book, the character speaks up for herself, which is the highlight of the book, but I still think she went through so much sensitive content that teenagers shouldn’t be thinking about it. In my opinion, the book was stereotypical, Melinda was shy, weak and quite, something happens to her, she changes. What if a strong person goes through something tough? Maybe that would’ve been different. There are some points of the book were the readers wanted her to be defensive, as kids were laughing at her, it was a need for her to respond, but she didn’t. On the other hand, the character should go through a dark time after what happened, although I feel like she didn’t persevere through it as much as readers wanted to see happen. This book explained highschool the wrong way, it makes parents worried about their children. Most high schools don’t really care about how you look, everyone studies and go home, in my opinion, it was a little exaggerated and unrealistic. In conclusion, it felt like it didn’t introduce new concepts, I didn’t find it succeeding at the originality part. It was a very negative book although it ended in a positive way. Some teenagers will use this book as a tool to cope with being raped, and the fact that the book is dark and the main hcarecter tried cutting herself, portrays a bad messege. In addition, the teachers, counselors, the students were very underrated, not labeled correctly, as the book should prove that there’s always someone to talk to, someone to help you, and not because someone raped you, everyone is bad. Furthermore, the book was pretty boring and slow at times which made some readers stop reading it. Lastly, I would rather read a story that has a bigger plot-line, and less about the unrealistic darkness of high school.

In conclusion, it felt like it didn’t introduce new concepts, I didn’t find it succeeding at the originality part. It was a very negative book although it ended in a positive way. Some teenagers will use this book as a tool to cope with being raped, and the fact that the book is dark and the main hcarecter tried cutting herself, portrays a bad messege. In addition, the teachers, counselors, the students were very underrated, not labeled correctly, as the book should prove that there’s always someone to talk to, someone to help you, and not because someone raped you, everyone is bad. Furthermore, the book was pretty boring and slow at times which made some readers stop reading it. Lastly, I would rather read a story that has a bigger plot-line, and less about the unrealistic darkness of high school.

What's the Story?

High school should be the best time of Melinda's life. Instead, freshman year is a nightmare as Melinda finds herself rejected by her friends, cut off from her parents, and unable to reveal a terrible secret. In fact, she isn't speaking at all. Melinda's slow healing process is a realistic and compelling one, and readers will cheer for her when she finally does use her voice.

In fact, she isn't speaking at all. Melinda's slow healing process is a realistic and compelling one, and readers will cheer for her when she finally does use her voice.

Is It Any Good?

This is one of the most devastatingly true and painful portrayals of high school to come along in a long time. The cliques, from the Jocks to the Big Hair Chix to the Marthas (devotees of a certain Ms. Stewart), are pigeonholed to perfection. Outsider Melinda seems somehow familiar, too. Her witty, ironic commentaries can't cover up her pain at being excluded.

Kids who are genuine outsiders stand to gain a lot from this compassionate novel. The author offers real solutions to Melinda's pain: Melinda's connection to a mentor, her artistic creations, and even her plans for a flower garden all feed her inner strength. When she's finally able to speak, readers will rejoice in her triumphs.

Talk to Your Kids About ...

Book Details

- Author: Laurie Halse Anderson

- Genre: Coming of Age

- Book type: Fiction

- Publisher: Puffin

- Publication date: January 1, 1999

- Publisher's recommended age(s): 12 - 12

- Number of pages: 198

- Last updated: April 12, 2019

Lexical level as a platform for creating language jokes

Bibliographic description:

Shirova, E. S. Lexical level as a platform for creating language jokes / E. S. Shirova. - Text: direct // Young scientist. - 2015. - No. 6 (86). - S. 843-846. — URL: https://moluch.ru/archive/86/15909/ (date of access: 11/10/2022).

S. Lexical level as a platform for creating language jokes / E. S. Shirova. - Text: direct // Young scientist. - 2015. - No. 6 (86). - S. 843-846. — URL: https://moluch.ru/archive/86/15909/ (date of access: 11/10/2022).

The article is devoted to the consideration of ways to create a language joke in the texts of the German humorist of the first half of the 20th century Karl Valentin at the lexical level. Units of the lexical language level have a powerful game potential, which K. Valentin uses in his works to create a comic effect. At the same time, the creation of a comic effect is based on a deviation from the typical use of a particular lexical unit and the implementation of the principle of bisociation of the meanings assigned to it.

Keywords: bisociation, language joke, language game, comic effect, pun, play potential of language.

The work of the Bavarian comedian and humorist of the first half of the 20th century Karl Valentin is an inexhaustible source of materials for studying the playful and creative potential of German language units. His ability to handle the plasticity, flexibility and variability of individual linguistic units to implement a comic effect proves the fact that the comic effect from the use of language units can be created at absolutely all language levels, from the simplest - phonetic, ending with the level of the whole text in various aspects of it. study. Most linguists dealing with questions of language jokes, following the maxims of ancient philosophers, consider the comic effect as a reaction to a deviation from certain norms. A language joke that generates a comic effect by language means is based on a language game. At the same time, the language game, as a term that first appeared in the works of L. Wittgenstein, implies a kind of linguistic experiment, during which the scope of the typical use of a particular language unit is expanded. Any deviation from the linguistic norm in this case does not lead to a language error in its gross manifestation, but contributes to the disclosure of the gaming potential contained in the language units.

His ability to handle the plasticity, flexibility and variability of individual linguistic units to implement a comic effect proves the fact that the comic effect from the use of language units can be created at absolutely all language levels, from the simplest - phonetic, ending with the level of the whole text in various aspects of it. study. Most linguists dealing with questions of language jokes, following the maxims of ancient philosophers, consider the comic effect as a reaction to a deviation from certain norms. A language joke that generates a comic effect by language means is based on a language game. At the same time, the language game, as a term that first appeared in the works of L. Wittgenstein, implies a kind of linguistic experiment, during which the scope of the typical use of a particular language unit is expanded. Any deviation from the linguistic norm in this case does not lead to a language error in its gross manifestation, but contributes to the disclosure of the gaming potential contained in the language units.

A linguistic joke can already be created at the phonetic level by playing on individual phonemes, or as a result of intentional violation of grammatical norms, that is, at the morphological level, or through the skillful use of word-building models to create author's occasionalisms, that is, at the word-building level. But still, the greatest game potential is contained in the already existing lexical units of languages, which have secured a certain semantics, pushing the author to perform even more linguistic experiments by shifting and mixing the formal and semantic levels of these units.

The lexical level is most often considered in linguistic studies of the category of the comic, since for a long time the pun was considered one of the forms of manifestation of the comic. However, a pun created using lexical means is one of the techniques for creating a comic effect. homonyms of various types (including homophones and homoforms) can take part in its creation. The possibility of including two or more homonyms in the same context creates all the necessary conditions for the realization of a comic effect. A. Koestler described these conditions as the principle of bisociation. By bisociation, Koestler means any mental activity in which one phenomenon is simultaneously associated with two usually incompatible contexts. Indeed, such, undoubtedly, is the basis of all literature of an absurdist nature, in which a logically deduced conclusion intersects with a typical for this situation, no less logical, act or phrase. Intersecting, two similar logical streams form a "junction", in the place of which, according to A. Koestler, a comic effect arises [Koestler 1964:51]. Homonyms played within the same context fit perfectly into this concept.

The possibility of including two or more homonyms in the same context creates all the necessary conditions for the realization of a comic effect. A. Koestler described these conditions as the principle of bisociation. By bisociation, Koestler means any mental activity in which one phenomenon is simultaneously associated with two usually incompatible contexts. Indeed, such, undoubtedly, is the basis of all literature of an absurdist nature, in which a logically deduced conclusion intersects with a typical for this situation, no less logical, act or phrase. Intersecting, two similar logical streams form a "junction", in the place of which, according to A. Koestler, a comic effect arises [Koestler 1964:51]. Homonyms played within the same context fit perfectly into this concept.

Full-fledged homonyms, that is, lexical units that completely coincide with each other formally, are played out in the following example. K. Valentin thinks about how much money he could sell his bones for. « Ich hab mich kürzlich ausgezogen und hab meine Knochen so abgegriffen und da hab’ ich ‘rausgefunden, dass ich 50 Knochen hab’ und weil ich in jedem Knochen „a Mark” hab‘, bin ich 50 Mark wert? "(Hereinafter our translation - Shirova E. S .:" Recently I undressed and felt my bones and found that I have 50 bones, and since I have bone marrow in each bone, am I worth 50 marks? ") [Valentin 1992: 16]. In this context, two meanings of the language unit Mark are realized: monetary unit (mark) and bone marrow. Due to the complete coincidence of the linguistic form, it is possible to replace one homonym with another quickly and painlessly for the context, or rather, the substitution of their meanings.

« Ich hab mich kürzlich ausgezogen und hab meine Knochen so abgegriffen und da hab’ ich ‘rausgefunden, dass ich 50 Knochen hab’ und weil ich in jedem Knochen „a Mark” hab‘, bin ich 50 Mark wert? "(Hereinafter our translation - Shirova E. S .:" Recently I undressed and felt my bones and found that I have 50 bones, and since I have bone marrow in each bone, am I worth 50 marks? ") [Valentin 1992: 16]. In this context, two meanings of the language unit Mark are realized: monetary unit (mark) and bone marrow. Due to the complete coincidence of the linguistic form, it is possible to replace one homonym with another quickly and painlessly for the context, or rather, the substitution of their meanings.

Homoforms existing in the language , which can be played at any moment unconsciously even in the course of an everyday conversation by any native speaker, when noticed, bring some aesthetic pleasure to native speakers. Sometimes Karl Valentin does not need to artificially create anything, everything is already at hand: [Valentin 1992: 230].

| Lehrer: Gut, und was ist ein Fremder? Schüler: Fleisch, Gemüse, Obst, Mehlspeisen usw. | Teacher: Well, what is a stranger? Student: Meat, vegetables, fruits, pastries, etc. |

The homonymy of the 3rd person singular forms of the verbs essen ( is ) and sein ( is ) is probably known to every native German speaker. Moreover, it is interesting that in Russian these two verbs in some of their forms coincide ( is ), which most likely indicates the importance of eating food to maintain life. In the following example, we are dealing with homophones : " Es hat eben alles auf der Welt seinen Vorteil und seinen Hinterteil, ah, seinen Nachteil, wollte ich sagen - nicht Nachteul, denn Nachteul ist ja ein Raubvogel " ("All on light has its front and back, um, its flaw, I mean, not a night owl0004") [Valentin 1992: 22]. The phonetic features of the speaker lead to smoothing out the difference between the sound of the diphthongs eu and ei . The dropping out of the unstressed vowel e at the end of the word Nachteuele (apocope) is also typical of oral speech, which makes the sound of the two lexical units under consideration Nachteil and Nachteul even closer. Thanks to the indicated phonetic transformations of lexemes and, this pair of situational homophones appears, which is used in the example.

The phonetic features of the speaker lead to smoothing out the difference between the sound of the diphthongs eu and ei . The dropping out of the unstressed vowel e at the end of the word Nachteuele (apocope) is also typical of oral speech, which makes the sound of the two lexical units under consideration Nachteil and Nachteul even closer. Thanks to the indicated phonetic transformations of lexemes and, this pair of situational homophones appears, which is used in the example.

The theme of the ban on mentioning the name of Adolf Hitler or his party after the end of the Second World War in Germany often slips into the stage monologues of Karl Valentin with his characteristic comic direction and is even played up in lexical ways, including homophones. "Mei Sohn, der Ignatz - wir haben halt immer Nazi dazu gesagt - jetzt sagn wir wieder Ignatz" ("My son is Ignaz - we always called him affectionately Nazi - now we say Ignaz again") [Valentin 1992:151]. The diminutive form of the name of the author's own son of this statement coincides with the colloquial form of the designation of the National Socialist Party of Germany, better known as the fascist party. Another pair of homophones for ridiculing the same taboo is also occasional in nature and depends entirely on the pronunciation of the language units playing in it. It is interesting to give this example in its entirety to recreate the context in which this pair of homophones is realized. "Nur mit den römischen Ziffern auf der Uhr kommt er nicht recht mit, und deshalb hats ihm mein Mann auf seiner Taschenuhr erklärt, --- siegst Walter, hat er gsagt, das hier ist der Einser, das hier der Zweier, dashier der Dreier und das der Vierer --- das ist der "Führer" uhi - hat der Walter gsagt, das derfens nimmer sagn, da werns von de Amerikaner aufghängt "("Only in Roman numerals on the clock, he will not understand in any way, and therefore my husband explained him on his pocket watch, - you see, Walter, he said, here is a one, here is a two, here is a three, here is a four --- this is the Fuhrer, uh, - said Walter.

The diminutive form of the name of the author's own son of this statement coincides with the colloquial form of the designation of the National Socialist Party of Germany, better known as the fascist party. Another pair of homophones for ridiculing the same taboo is also occasional in nature and depends entirely on the pronunciation of the language units playing in it. It is interesting to give this example in its entirety to recreate the context in which this pair of homophones is realized. "Nur mit den römischen Ziffern auf der Uhr kommt er nicht recht mit, und deshalb hats ihm mein Mann auf seiner Taschenuhr erklärt, --- siegst Walter, hat er gsagt, das hier ist der Einser, das hier der Zweier, dashier der Dreier und das der Vierer --- das ist der "Führer" uhi - hat der Walter gsagt, das derfens nimmer sagn, da werns von de Amerikaner aufghängt "("Only in Roman numerals on the clock, he will not understand in any way, and therefore my husband explained him on his pocket watch, - you see, Walter, he said, here is a one, here is a two, here is a three, here is a four --- this is the Fuhrer, uh, - said Walter. - We cannot say this, otherwise the Americans will hang us") [Valentin 1992:154]. By a happy coincidence, Karl Valentin finds another potentially playful component: a child who learns to understand by the clock, hearing the word Vierer, repeats it in a manner more familiar to him - Führer, not realizing the taboo of this expression, and maybe even its meaning. The phonetic similarity of these units forms a language joke.

- We cannot say this, otherwise the Americans will hang us") [Valentin 1992:154]. By a happy coincidence, Karl Valentin finds another potentially playful component: a child who learns to understand by the clock, hearing the word Vierer, repeats it in a manner more familiar to him - Führer, not realizing the taboo of this expression, and maybe even its meaning. The phonetic similarity of these units forms a language joke.

Along with homonyms, the creation of a pun is facilitated by the phenomenon of polysemy . Often the author neutralizes the metaphorical or figurativeness attached to one of the meanings of the word, thereby implementing the techniques demetaphorization or dehyperbolization . In the following example, one can observe just such a loss of the metaphorical meaning contained in the additional figurative meaning. “ AUF EINMAL SAGT ZU MIR , ICH SOLL IHM ' Reinbringen 9000 3 ihm or rechte Fu ß eingeschlafen ist "(" Suddenly he tells me that I should bring him an alarm clock, because his right leg fell asleep (numb) ") [: 19] . Due to this semantic narrowing of the meaning of the word einschlafen to its first literal and further development of a causal relationship (if something falls asleep, you need to set the alarm), a comic effect is born.

Due to this semantic narrowing of the meaning of the word einschlafen to its first literal and further development of a causal relationship (if something falls asleep, you need to set the alarm), a comic effect is born.

Karl Valentin is a master of game chains. Once played, he includes the element in the context, where other language units are waiting for their turn to participate in the game. "Mein Vater hat mich sehr streng musikalisch erzogen . Als Kind habe ich nur mit der Stimmgabel essen dürfen, geschlagen hat mich mein Vater nach Noten "(" My father raised me strictly musically. As a child, I could only eat with the help of a tuning fork, my father beat me on notes ”) [Valentin 1992: 25]. Musical education here boils down to the fact that the child eats with the help of a tuning fork, and they beat him according to the notes. That is, the word Stimmgabel , which belongs to the semantic field "music" replaces the adequate here G abe l (fork), which is used during meals, and the usual punishment for the child is replaced by the polysemy of the verb schlagen , tools.

The topic of hunger, which was relevant during the period of his work, is quite tragic in itself. However, she also gives Karl Valentin a reason to create a comic effect. “Es wirkt heute direkt lächerlich, wenn ein armer Kranker vom Doktor gewarnt wird, Sie dürfen sich nie mit vollem Magen ins Bett legen (“Today it even seems ridiculous when a doctor warns a poor patient against going to bed with a full stomach » [Valentin 1992:162]. Ein armer Kranker - the poor patient also contains an element of polysemy: 1) the poor patient, 2) the poor patient. The realization of the comic effect in such jokes depends entirely on the reaction of the viewer or reader, on his ability to find the veiled irony and see the sarcasm of life in this. The doctor just does his job, mechanically gives advice. It is hardly possible for a poor person who has nothing to eat anyway to lie down after having just eaten. Further in the same monologue we meet: “Was sagen Sie zu der jetzigen Lage? - A nette Lage, bald werden wir uns hinlegen, weil wir vor Hunger nimmer stehen können, dann haben wir die richtige Lage ”(“ What can you say about the current situation? - Nice position, soon we will all lie down, because we can no longer stand from hunger, and then we will take the right position") [Valentin 1992:162]. The noun Lage comes into play based on its ambiguity. On the one hand, this is a position, a situation, on the other hand, a position, a posture. And another important realized meaning here is its derivational connection with the verb liegen, which is used in the context of the direct spatial meaning — to lie down. This is how the third meaning of the noun Lage appears - the prone position. An advantageous combination of values based on a common component is hunger in the country as an indicator of the economic situation, and hunger, from which the legs give way, that one wants to lie down. Further context reinforces the effect created by the position. In such a lying position, it is very convenient to ascertain death from starvation.

The noun Lage comes into play based on its ambiguity. On the one hand, this is a position, a situation, on the other hand, a position, a posture. And another important realized meaning here is its derivational connection with the verb liegen, which is used in the context of the direct spatial meaning — to lie down. This is how the third meaning of the noun Lage appears - the prone position. An advantageous combination of values based on a common component is hunger in the country as an indicator of the economic situation, and hunger, from which the legs give way, that one wants to lie down. Further context reinforces the effect created by the position. In such a lying position, it is very convenient to ascertain death from starvation.

Paronyms can also be used to implement the pun technique. For example: “ Ich War Ein Damalyiger Knabe von Ungefährlich 15 Jahren ” (“ then I was young people non -hazardous years ”) [Valentin 1992: 127]. The comic effect of this case is created due to a mistake made out of ignorance. The word is used incorrectly instead of a lexeme ungef ä hr (approximately, approximately), the hero says ungef ä hrlich (not dangerous), due to which his comic image of an ignoramus is created, which is revealed in the subsequent context.

The comic effect of this case is created due to a mistake made out of ignorance. The word is used incorrectly instead of a lexeme ungef ä hr (approximately, approximately), the hero says ungef ä hrlich (not dangerous), due to which his comic image of an ignoramus is created, which is revealed in the subsequent context.

Phraseologisms have a huge playing potential, which is skillfully used by Karl Valentin. He dismembers them, introduces alien elements into their composition, combines them with other stable combinations, thereby giving rise to the phenomenon of contamination, and also rethinks their meaning using the technique dephraseologization . The atypical use of phraseological units with the loss of the portable component underlying it leads to the loss, in general, of the entire meaning of the phraseological unit, however, undoubtedly, it gives rise to a comic effect, as, for example, in the sentence: “ Ja , der Ring liegt mir heute noch am Herzen , nicht in Witke , sondern man sagt eben so , denn wenn er mir in Wirklichkeit am Herzen liegen t ä t , Dann W ü SSTE ICH Wo ER W ä r "("Yes, the ring is very close to my heart today, not really, but just like that, because if it was really close to my heart, then I would know where it is" ) [Valentin 1992: 31].

Often the demetaphorization of a phraseologism occurs exactly according to this scheme, when one of its components is included in relations with other components of meaning within the framework of the situation being played out. On the example of idioms, this is most clearly manifested: "Der Mensch denkt und Gott lenkt", - wie ich das gelesen habe, habe ich mein Radl gepackt, bin auf die Straße hinaus, habe mich hinaufgesetzt und bin dahin gefahren, ohne zu lenken" (" Man proposes, but God disposes (here: manages),” as soon as I read this, I quickly grabbed my bicycle, went out into the street, sat on it and rode without holding on to the steering wheel” [Valentin 1992:37]. The verb lenken (to drive, including a vehicle) breaks out of the well-known idiom and is understood literally due to the meager cognitive ideas about the world of the depicted hero. This example clearly demonstrates the potential vulnerability of any metaphor. The presence of a figurative component in it indicates that with a minimal change in the context, the semantic unity of everything metaphorically designated as a whole is violated.

The illustrated examples of language jokes prove the hypothesis that the lexical level of the language hides a great play potential. The meaning assigned to a certain lexeme is vulnerable to creative influence on it, which allows creating a large number of game precedents that entail a comic effect.

Literature:

1. Wittgenstein L. Philosophical Investigations. - In the book: New in foreign linguistics, vol. 16. M., 1985. - 353 p.

2. Sannikov V. Z., Russian in the mirror of the language game, M., 2002.

3. Karl Valentin, Sämtliche Werke: Monology und Soloszenen, München, 1992. Band1.

4. Koestler A. The Act of creation. N.Y.: Hutchinson Press, 1964. — 751 rubles

Basic terms (automatically generated) : comic effect, language joke, unit, game potential, volume, language game, bone marrow, lexical level, my heart, German.

The lexical level of the language as an open system - Studopediya

PETROVSKY

Department of the Russian language and its teaching methods

Voronichev O. E.

E.

Lexical style

and speech Culture

Bryansk - 2007

BBK 81.2 RREA73

V - 75

Voronichev O.E. Lexical stylistics and culture of speech: Textbook for teachers and teachers of the Russian language and literature working in lyceums, gymnasiums, humanitarian classes. - Bryansk: Cursive, 2007. - 246 p.

Textbook, written mostly in popular science style, full of illustrative material and quotations from the works of prominent linguists and devotees of the culture of speech, contains information about the main sections and concepts of lexical stylistics. For an objective and complete idea of the stylistic qualities of vocabulary, the manual contains information about the history of formation and the current state of the lexical composition of the Russian language, about general and multi-level features of functional styles; a stylistic assessment of phraseological units and lexical means of figurative speech is given. The book is addressed to teachers and teachers of the Russian language and literature of lyceums, gymnasiums, humanitarian classes of general education schools, but may be useful to students of philological and non-philological specialties studying disciplines stylistics of the modern Russian literary language and Russian language and culture of speech , teachers of colleges and higher educational institutions, people of creative professions, as well as everyone who is interested in the problems of speech culture and seeks to improve their own level of normative word usage. The materials of the manual can also be used in the development of special courses lexical stylistics and practical lexicology .

The book is addressed to teachers and teachers of the Russian language and literature of lyceums, gymnasiums, humanitarian classes of general education schools, but may be useful to students of philological and non-philological specialties studying disciplines stylistics of the modern Russian literary language and Russian language and culture of speech , teachers of colleges and higher educational institutions, people of creative professions, as well as everyone who is interested in the problems of speech culture and seeks to improve their own level of normative word usage. The materials of the manual can also be used in the development of special courses lexical stylistics and practical lexicology .

© Voronichev O.E., 2007.

© Italics, 2007

Nec Caesar supra grammaticos[1]

The lexical composition of the modern Russian language as a mirror of historical changes in the life of society

The lexical level of the language as an open system : he is very conservative, but at the same time extremely mobile. It develops through the continuous accumulation of words. At the same time, the meaning of neologism enters into systemic relations with the meanings of other words. They can be synonymous, antonymous, homonymous, etc. The appearance of neologism often affects the use of words already rooted in the language. For example, word dessert penetrated into the Russian language from French in the 18th century and was originally used only in court life, and then began to actively interact with the words appetizer and snack (meaning "sweets, fruits served at the end of the meal"). As a result, the word appetizer gradually changed its meaning and began to refer to dishes served at the beginning of a meal; and the word snack became colloquial (i.e. stylistically limited).

It develops through the continuous accumulation of words. At the same time, the meaning of neologism enters into systemic relations with the meanings of other words. They can be synonymous, antonymous, homonymous, etc. The appearance of neologism often affects the use of words already rooted in the language. For example, word dessert penetrated into the Russian language from French in the 18th century and was originally used only in court life, and then began to actively interact with the words appetizer and snack (meaning "sweets, fruits served at the end of the meal"). As a result, the word appetizer gradually changed its meaning and began to refer to dishes served at the beginning of a meal; and the word snack became colloquial (i.e. stylistically limited).

Thus, the lexical level of the language is an open system. At the center of this system are commonly used words; their number is relatively small - it does not exceed thirty thousand lexical and phraseological units, of which no more than 50% are actively used in everyday speech. Away from the center - on the 2nd plane of use - there are about 50 - 70 thousand words that we use much less often in our speech (many of them are incomprehensible to most native speakers and are attributes of the speech of only highly educated people). So, the total active stock of modern Russian vocabulary fluctuates within 100 thousand words (compare: in the "Dictionary ..." by Ozhegov and Shvedova there are about 80,000 words; in the 4-volume MAS, published in 1981 - 1984 - over 90,000 units; in the 17-volume BAS - 120,000 words). And then - an innumerable number of words that we do not use or extremely rarely use in our speech, although we are able to understand the meanings of some of them. This is a passive vocabulary. This includes various obsolete words (archaisms and historicisms), super-new neologisms, narrow-territorial dialectisms, narrow professional terms, jargon, etc.

Away from the center - on the 2nd plane of use - there are about 50 - 70 thousand words that we use much less often in our speech (many of them are incomprehensible to most native speakers and are attributes of the speech of only highly educated people). So, the total active stock of modern Russian vocabulary fluctuates within 100 thousand words (compare: in the "Dictionary ..." by Ozhegov and Shvedova there are about 80,000 words; in the 4-volume MAS, published in 1981 - 1984 - over 90,000 units; in the 17-volume BAS - 120,000 words). And then - an innumerable number of words that we do not use or extremely rarely use in our speech, although we are able to understand the meanings of some of them. This is a passive vocabulary. This includes various obsolete words (archaisms and historicisms), super-new neologisms, narrow-territorial dialectisms, narrow professional terms, jargon, etc.

However, neither the "center" nor the "periphery" of the lexical level has been established once and for all. A long-forgotten word or expression may again become one of the most common (for example, State Duma , Governor , Gymnasium , Lyceum , Governor , etc.), and what was on everyone’s lips just yesterday is forgotten (as, for example, the words kerenka 900, maximka (train), gavrilka (collar), bagging or abbreviations of the 20s - 30s shkrab, commander, commander, detkor, accountant, military specialist , etc.). Therefore, it is impossible to strictly separate the history of vocabulary and its current state: the gradual updating of the dictionary takes place constantly, daily.

A long-forgotten word or expression may again become one of the most common (for example, State Duma , Governor , Gymnasium , Lyceum , Governor , etc.), and what was on everyone’s lips just yesterday is forgotten (as, for example, the words kerenka 900, maximka (train), gavrilka (collar), bagging or abbreviations of the 20s - 30s shkrab, commander, commander, detkor, accountant, military specialist , etc.). Therefore, it is impossible to strictly separate the history of vocabulary and its current state: the gradual updating of the dictionary takes place constantly, daily.

Vocabulary of a language is, first of all, a reflection of the surrounding world.

Language reflected everything - the surrounding reality, nature and the Cosmos, imaginary objects and fruits of fantasy, our relationships - family and work, everything that was and is. He will certainly fix what is not yet, but what will be, because language is inextricably linked with consciousness, "this is our real consciousness. " Language named everything that is in a person, with his appearance and spiritual world, with his feelings, emotions, affects, with his assessments and relationships (89, p.60).

" Language named everything that is in a person, with his appearance and spiritual world, with his feelings, emotions, affects, with his assessments and relationships (89, p.60).

At the same time, people and peoples who speak different languages see the world differently, as evidenced by the language. For example, in Russian the concepts snow, cold, ice are distinguished, but the Aztecs do not need such a distinction, who convey all this in one word; or, on the contrary, in the language of the Eskimos there are special names for falling snow, melting snow, etc. Some words convey to us ancient ideas about the world. For example, we say the sun rises, sets or sits down , not thinking that these statements reflect the ancient idea of the movement of the Sun around the Earth. Consequently, the lexical level of the language contains a certain worldview, or concept, in a particular period of the history of society, due to which we can speak of conceptuality of the lexical level.