The 4 b's

The 4 B's | Learning Forward

When we learn about an educational intervention that is inspiring, innovative, or appears effective, we often think our next step is obvious: Take it back to our schools or systems and replicate it. We may be so enchanted by the content of what we’ve encountered that we just charge ahead, forgetting all the other things we know about the necessary conditions for change, especially when we adopt an idea from elsewhere. That’s when many problems begin.

A practice that is seemingly perfect in someone else’s class or school can become a shadow of itself if you try to adopt it exactly as is, without considering your context. Professional learning communities, instructional rounds, learning walks, data teams, peer review, lesson study, and improvement science — you name it, and we’ll show you examples of how educators have misapplied them because they did not understand the conditions that enable success.

Although sometimes this is the result of a desire for a quick fix, more often it is the result of educators’ enthusiasm for learning and making a difference. When their efforts fall flat, they can feel crestfallen.

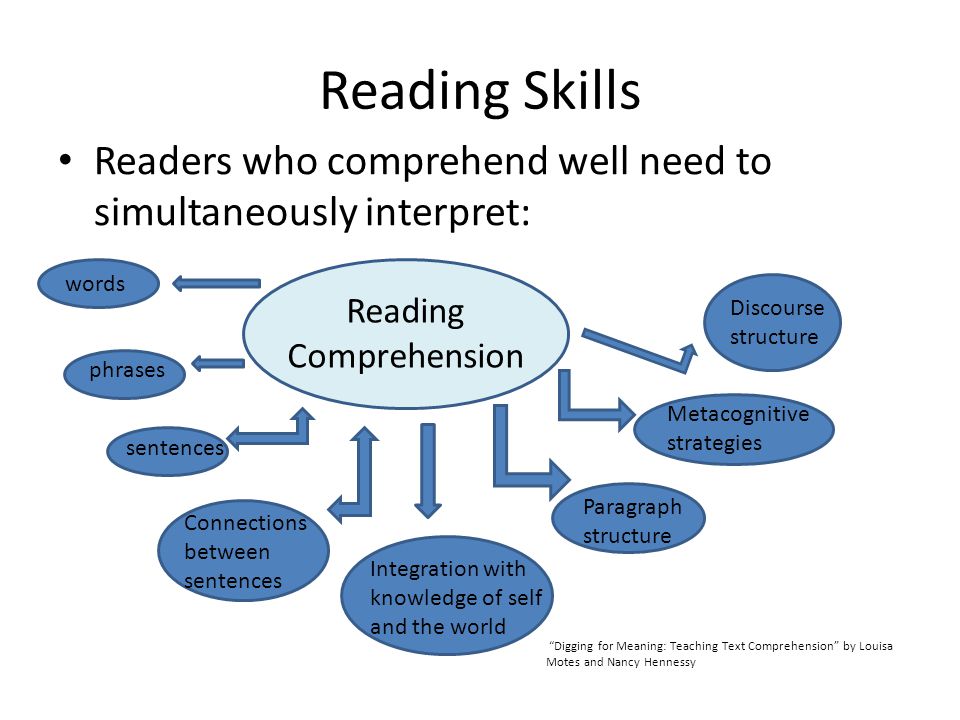

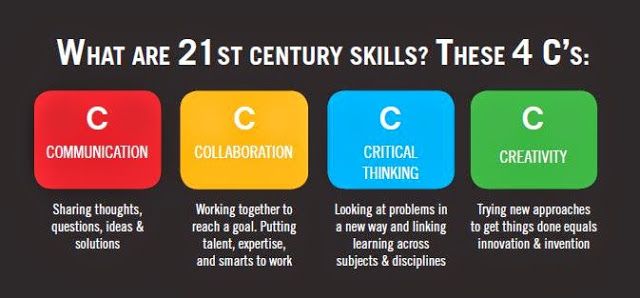

This situation is avoidable, however. Asking probing questions and digging beneath the surface are essential for understanding what makes a particular model of teacher collaboration (or other innovation) successful. To help educators engage in this kind of thinking, we have developed a model we call the four B’s.

THE FOUR B’S

The four B’s framework grew out of our global study of collaborative professionalism (Hargreaves & O’Connor, 2017, 2018). We define collaborative professionalism as ways educators work together with depth, trust, and precision to achieve impact. We set out to study how it manifests in different cultures and countries.

As we looked across these settings, we found that particular designs for collaborating, like lesson study or teacher-led learning communities, seemed to work brilliantly in one culture or context but had features that might not work as well or in the same way in other contexts.

What would it take, we wondered, for these strategies to be just as effective elsewhere? What would we need to understand to take a collaborative practice from the Canadian wilderness, the forests of Colombia, the tower blocks of Hong Kong, or the forgotten small towns of rural America and successfully move it into a suburb or inner city? What would educators need to know, above and beyond the specific features of the collaboration method —because what you see isn’t self-evidently what you get?

We have summed up what educators need to know about the conditions for success according to four B’s: What was happening before, beside, beyond, and betwixt the collaboration. When we encounter and examine any new practice, as well as noting things about the practice itself, we also need to learn what happened:

- Before the moment we witnessed it, including the trust that had to be established, how long key leaders had been at the school, and so on;

- Beside the innovation, such as funding, policies, priorities, and competing initiatives that supported the innovation, or at least did not undermine it;

- Beyond the practice itself, including teachers’ and leaders’ engagement in additional networks and learning opportunities, and the contribution of resources or policies from provincial, state, or national systems; and

- Betwixt the collaborators, in the sense of shared understandings and cultural norms of collaboration (or its absence) in the school, the system, or the whole society.

Let’s look at these four B’s in action in two different examples of collaborative professionalism.

COOPERATIVE LEARNING AMONG TEACHERS

Drammen Elementary School in Norway is less than an hour’s train ride outside Oslo. When we walked around the schoolyard, we spied a simple but innovative design. Two young girls were sitting on a stone bench. “That’s our friendship bench,” Principal Lena Killen explained. “If a child has no one to play with, they sit down there and someone else will come and play with them.” How beautifully simple. “Why couldn’t every school everywhere have one of these?” we thought.

When we got home, an item on U.S. National Public Radio was devoted to this very issue — the introduction of “buddy benches” in American schools (Cimini & Howard, 2017). To our surprise, the reviews were not all positive. In some schools, one commentator noted, buddy benches marked children who sat on them and made them targets for bullying. An anti-bullying invention in Norway could actually incite bullying in the U. S. The bench was the same, but what went on betwixt the cultures in each of the two societies was quite different.

S. The bench was the same, but what went on betwixt the cultures in each of the two societies was quite different.

If simple benches can have different meanings in different places, this is even more true for complex organizational designs. At Drammen, the school has adopted the cooperative learning strategies of U.S. psychologist Spencer Kagan. Students cooperate in multiple structured ways through carefully designed group processes to pursue learning and achievement together.

The school uses these strategies not only with the children, but also among the staff. Teachers share and commit to expanding the range of strategies they use in their classes. They get involved in understanding and shaping the big picture of where their school is headed. And they look collaboratively at student achievement data to identify patterns. For example, they found that, contrary to a national trend, the girls were performing less well than the boys.

Sometimes, the staff work in carefully designed subgroups of mixed age, experience, and specialist expertise. At other times, they will snake around the room as if they are in a game of musical chairs until they are signaled to stop and work with whoever happens to be around them. The system seems very impressive, so why shouldn’t observers who witness this awesome design go back and implement it in their own schools right away?

At other times, they will snake around the room as if they are in a game of musical chairs until they are signaled to stop and work with whoever happens to be around them. The system seems very impressive, so why shouldn’t observers who witness this awesome design go back and implement it in their own schools right away?

Well, the design works in building positive and engaged collaboration not just because it’s a brilliant design, but also because of the four B’s that surround it:

- Before initiating structured cooperative learning, principal Killen had been building collaboration more informally for nine years. Her predecessor had decided everything for the school, right down to choosing the curtains and furnishings. It took time for Killen to get everyone to decide things together.

- Beyond her school, staff had learned about cooperative learning by participating in training programs in the United Kingdom and by seeing examples of effective cooperation through school partnerships with Ontario, Canada.

- Beside her efforts has been a national government that endorses a broad curriculum, provides data support, and has an agreement with the teacher unions that includes scheduled collective time for teachers to work together.

- Betwixt the formal participation in cooperative learning, the staff has many other ways of collaborating, including eating together. The entire culture of Norwegian schools is also one where teachers and students spend a lot of school time together outdoors in nature in all kinds of weather, even in the depths of winter. This way everyone really gets to know and trust each other, the teachers say.

All of these factors likely impact the effectiveness of the cooperative learning structures in a positive way. If the conditions were different, the implementation and outcomes might be different. Consider, for example, what might happen if the cooperative learning structures were used in a school where there is a new principal, no history of collaboration, no scheduled time to collaborate, or an obsession with standardization and test scores and a lack of time for building relationships outside the building as well as inside it.![]()

RURAL COLLABORATIVE PLANNING NETWORKS

As another example, consider the four B’s in a network we facilitated of rural schools in economically disadvantaged communities. Teacher isolation is a major hindrance to school effectiveness and student achievement, and the problem is especially acute in rural communities. There may be only one teacher per subject or grade level, and staff members feel they have to be a Jack or Jill of all trades. As one teacher we worked with put it, “It’s hard to collaborate with yourself.”

Over five years, with colleagues from Boston College, we have collaborated with the Northwest Comprehensive Center at Education Northwest to develop a network among educators in rural and remote schools in five Pacific Northwest states. Many of these communities have high levels of poverty and face other challenges exacerbated by being isolated from other communities and resources.

Because of the unique nature of every rural environment, the problems of educational equity for rural schools cannot be resolved simply by exporting solutions that have worked in urban school reform. So we worked collaboratively with state education agency representatives, then principals and teachers, to co-design and then steer an evolving network that suited rural contexts and that now comprises 32 schools in total (Hargreaves, Parsley, & Cox, 2015).

So we worked collaboratively with state education agency representatives, then principals and teachers, to co-design and then steer an evolving network that suited rural contexts and that now comprises 32 schools in total (Hargreaves, Parsley, & Cox, 2015).

At the core of the network, teachers plan curriculum collaboratively, twice a year in person and online in between, with job-alike colleagues from other schools. They shared each other’s ideas, and they challenged them, too. Teachers were engaged and appreciated the collaboration.

After a while, not only were teachers collaborating, but their students were, as well. Danette Parsley, chief program officer at Education Northwest who played a major role in initiating the network, described how the English language arts group first developed its planning work into a combination of sharing resources and designing some lessons.

“Not too far into it,” she said, “they realized, ‘Wait a minute. Instead of us just designing lessons together, why not get our kids involved?’ ” So high school students across schools started to peer review each other’s writing, saying that it was actually easier to give honest feedback to students far away than ones who sat next to them in class.

The result was that, according to teachers in the English language arts group, students’ writing became more authentic and argumentative as the students debated the pros and cons of using drones in the military or agriculture and presented their assessments of 1:1 devices in schools to local politicians.

As one student reported, he made intentional language choices in his writing when directed to the state representative on a topic he cared about because “I thought I could be heard.” Teachers weren’t isolated anymore, and students had their eyes opened to a world beyond their own community.

The network was really buzzing and continues to thrive. So why wouldn’t another system or other project leaders want to come in and copy it exactly as it is? Well, if they did, in addition to describing how the network has been designed, we’d also need to explain to them that:

- Before the network functioned this way, it had evolved carefully, collaboratively, and inclusively over five years.

It wasn’t a club of like-thinking schools with a badge, a brand, and an annual conference they could instantly sign up for. And it wasn’t a top-down bunch of regional clusters created by a state bureaucracy to get its mandates and standards implemented. They couldn’t just copy our network. They’d have to evolve their own.

It wasn’t a club of like-thinking schools with a badge, a brand, and an annual conference they could instantly sign up for. And it wasn’t a top-down bunch of regional clusters created by a state bureaucracy to get its mandates and standards implemented. They couldn’t just copy our network. They’d have to evolve their own. - Beyond the other schools in the network, participants also had the opportunity to engage with us (from the Northwest Comprehensive Center at Education Northwest and Boston College) and learn from our experience designing and evaluating networks in other systems and countries. They had listened to and engaged with keynote speakers who had come to their twice-yearly meetings to disrupt their thinking and shake up their ideas. And they had engaged with teachers from other networks in the U.S. and Canada who came to talk about their own networks and their impact. These schools and teachers therefore drew on multiple examples in co-designing their own network.

- Beside the network were representatives of the states who gently ensured that network activities meshed with state standards. They encouraged teachers to see the Common Core State Standards as an opportunity, a common cross-state learning touchstone, that could help to drive collaboration, and teachers responded once they saw this potential value. Because of this integration, they actively supported the development of the network and its efforts to increase student engagement over time.

- Betwixt the network was a culture of rural educators who wanted to help their students succeed and increase opportunities for all of them. But rather than just getting caught up in idealistic bold visions, teachers knew they had to do the hard work of creating engaging, relevant learning opportunities, and that they had to view their rural environments and cultures as opportunities and assets, not only or mainly as deficits.

If anyone looked at a snapshot of the network and missed all that happened to bring it to this point or all the things going on behind the scenes, they might have tried to adopt the model in another setting with little success. For example, if school leaders set up the operations for a new network, failing to understand that teachers in our network had co-constructed it, they might have failed to build professional investment and incurred teachers’ disapproval later on.

For example, if school leaders set up the operations for a new network, failing to understand that teachers in our network had co-constructed it, they might have failed to build professional investment and incurred teachers’ disapproval later on.

Organizations shouldn’t have to reinvent the wheel. But most will have to invent or adapt their own kinds of wheels that best fit their own terrain, mindful of the other kinds of wheels that are already around.

BE ALERT

Being alert to the four B’s may make all the difference when you are working to adopt a new practice in your own school. If you look at lesson study in East Asia, as we did in Hong Kong, expect that interactions will be much more formal, structured, and even strict than in the U.S. or Canada, for instance.

And if you watch teachers collaborate in rural Colombia, you need to see that animated political, professional, and social conversations are all intertwined with each other, in ways that may not mesh so easily with cultures elsewhere.![]()

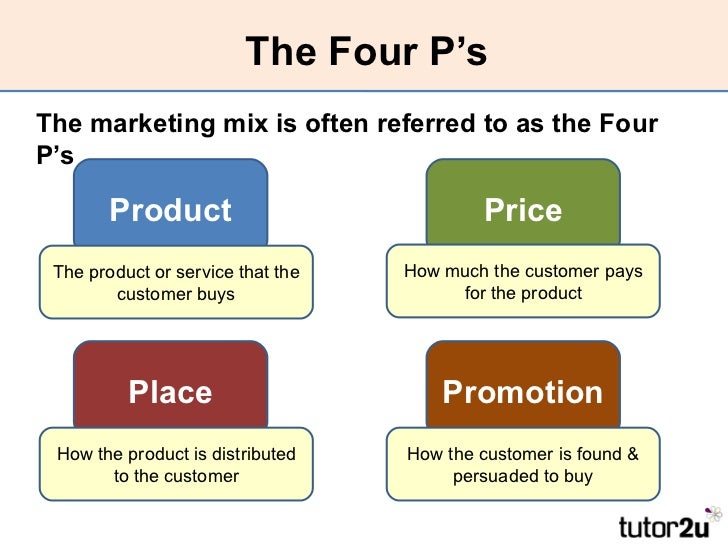

As you engage with and then reflect on new practices and how they might work for you, consider the guiding questions in the figure on p. 55. Engage with these four B’s of professional learning and you will understand and implement everything you try to adopt and adapt with greater depth and more success because it will fit your own culture and community.

Self-Evaluation and "The Four B's"

Do you feel that you are a truly worthwhile person?

What do you see when you are genuinely trying to evaluate yourself and you look in the metaphoric mirror of life? That is, when you are wholly truthful with yourself—no masks, no games, no pretense, defensiveness or guile—do you really like (respect, admire, appreciate) that person you see?

Who are we, really?

We all experience successes and pleasures in our lives, just as we do disappointment and setbacks. Life can be complicated and pressured. In these circumstances, we sometimes wonder about our personal qualities or worthiness as human beings. We might behave differently in diverse circumstances (work, school, family, recreation) and when we're with different people and settings. There may be times we worry about how we're being perceived by others, but we ultimately have to answer to ourselves.

We might behave differently in diverse circumstances (work, school, family, recreation) and when we're with different people and settings. There may be times we worry about how we're being perceived by others, but we ultimately have to answer to ourselves.

I've learned through research studies, clinical work and social relations with people of diverse ages and backgrounds that we all want to be "comfortable in our own skin." We know that if people have enough to live on and are properly clothed, sheltered and safe (admittedly a big IF), it is not the amount of accumulated material wealth which leads to self-appreciation and ease 'inside' their beings. Most people are looking for more substance and meaning in life, and in fact, have similar views about what makes them appreciative of their own worthiness.

So, what is it they (we) are all looking for?

The genuine appreciation of our worthiness and our quality depends on whether we achieve four core inner senses, which I call "The Four B’s"—the personal senses of Being, Belonging, Believing and Benevolence.

BEING (Personal): People who have achieved a sense of Being feel grounded and at ease with themselves. They have the sensation of inner peace and self-acceptance. They have insight into themselves and they have a realistic self-image, neither boastful or demeaning of themselves. They are grateful for who they have become and how they’ve acted with others. They are aware of their strengths and potential, and similarly, of their faults and limitations. They appreciate themselves in spite of the mistakes they have made and their emotional scars. They have worked at overcoming their frailties and redeeming themselves for transgressions.

They are empathic and caring, kind and generous to family, friends, and strangers, and they're respectful and tolerant of others. They are responsible and trustworthy and feel comfortable with who they have become.

BELONGING (Social): People with a sense of Belonging know they are integral members of at least one group or community of people that is very important to them, where they feel comfortable, liked and appreciated, and where they genuinely reciprocate those feelings. These groups could compose a family or close friends, a congregation, a club, gang, team, cast, platoon or a wide range of other possible communities.

These groups could compose a family or close friends, a congregation, a club, gang, team, cast, platoon or a wide range of other possible communities.

Members of these communal groups feel an organic affiliation and comfort with others who share their values and traditions. The members provide support, respect, and friendship. These kinds of relationships bestow pleasure and fulfillment. They diminish anxieties and help prevent depression associated with loneliness. The warm glow of belonging contributes to their physical and emotional health and enhances the quality of their lives.

BELIEVING (Ethical/Spiritual): A sense of Believing refers to having guiding values and principles of one's behavior. Millions of people around the world venerate (their perception of) a God(s) who gives them comfort and hope and provides moral rules for their ethical conduct. But one need not believe in a Supreme Being to be an ethical individual, and by the same token, religious followers are not inherently more principled or compassionate than agnostics and atheists. We human beings need to believe in a system of moral principles and civil behavior. Ideally, we adhere to these overriding tenets in our daily functioning and relationships and we wish to pass these down to our children. When we act according to principles based on religion or other humane social philosophies, our lives become more meaningful during times of both joy and pain.

We human beings need to believe in a system of moral principles and civil behavior. Ideally, we adhere to these overriding tenets in our daily functioning and relationships and we wish to pass these down to our children. When we act according to principles based on religion or other humane social philosophies, our lives become more meaningful during times of both joy and pain.

Our lives can be at different times and circumstances rewarding, mundane or challenging: We are concerned about ourselves and perhaps even more about our families, wanting to protect and facilitate their navigation through life's challenges. We are also at times beset with the pressures of finances, responsibilities, health, obligations, social demands, political issues and other aspects of life's travails. The details and decisions of life can get to us.

Yet when we wonder about issues beyond everyday practicalities and materialism, we can be awed by just how minuscule we are. We are microscopic in our own world, but especially infinitesimal when we consider our own infinite universe and countless other universes. Looking at the photographs taken from the Hubble telescope can be riveting and awe-inspiring. They can transport our thoughts into cosmic or spiritual realms, and help us realize we have but one life to live, and making it fulfilling and meaningful becomes of even more consequence.

Looking at the photographs taken from the Hubble telescope can be riveting and awe-inspiring. They can transport our thoughts into cosmic or spiritual realms, and help us realize we have but one life to live, and making it fulfilling and meaningful becomes of even more consequence.

BENEVOLENCE (Altruism): A sense of Benevolence refers to the extent to which we have bestowed a caring effect on others. It encompasses how we have positively affected and contributed to people in our lives. This can be in our everyday lives when we demonstrate seemingly small but important acts of kindness and generosity. The positive effects we have on others linger on in the 'social atmosphere.'

Benevolence is in a way a culmination of the other B’s. Our personal legacies are best represented by our acts of decency and respect for each other. Notwithstanding humanity's history of aggression and violence, we humans are also genetically predisposed to be helpful to others. Studies have shown that we can, in fact, learn to behave with more tolerance and generosity and with less aggression and animosity. The kindness and goodness we bestow on others throughout our lives is the essence of a sense of benevolence.

The kindness and goodness we bestow on others throughout our lives is the essence of a sense of benevolence.

Nobody is perfect. I know many wonderful people but have yet to meet a veritable saint or tzaddik who is the epitome of perfection in all of his/her personal thoughts and behaviors. While a purely noble existence may be beyond us mere mortals, most of us endeavor to be intrinsically worthwhile: decent, honest and caring—in other words, a "Mensch."

When we are evaluating the worthiness of our lives, we aspire to the goals of the Four B’s. These are the foundations for our important core legacies, “Our Emotional Footprint.”

Furnace VESUVIUS Sensation 16 Anthracite (DT-4) b/w. RF production. Products webpage.

The advantage of the stove is that the hearth of the stove consists of 3 elements. At the junction between them, a ceramic cord with an operating temperature of 1200 degrees is used. That is, the furnace furnace is absolutely hermetic! To fix the parts together, a bolted connection is used, which gives a 100% guarantee of safety during operation.

The advantage of the Sensation stove is a voluminous, ventilated heater that allows you to heat the stones as quickly as possible from four sides in the shortest possible time. A large mass of stones placed in the stove heater is heated up to 350 °C, which ensures temperature stability in the steam room and is a powerful steam generator. The heating surface of the stove is covered with a super-capacious external convection-ventilated casing, which significantly accelerates the heating of the air in the steam room due to the powerful convection flow generated by it. nine0003

|

| Humidity, % | Time, t (min) | ||||

| Temperature, ° C | FINA SUNA | 90-110 | 5-15 | 40 | Russian Bath Goryachny (Wet Saun) | 70-90 | 20-35 | 30 |

| Classic Bath (steam sauna) | 45-65 | 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9,000 | Turkish bath (steam bath) | 40-45 | about 100 | 20,0003 |

| Temperature, °С | Humidity, % | Time, t (min) | |

| Classic Russian bath | 45-65 | 40-65 | 50 |

| Hot Russian bath | 70-90 | 20-35 | 60 |

| Turkish bath | 40-45 | approx. | 40 |

| Finnish sauna | 90-110 | 5-15 | 80 |

*The appearance of the product may differ slightly from the photos on the site

Width:

410 mm

Height:

620 mm

depth:

540 mm

series:

Sensation

Partoral room:

from 8 to 18 m3

Topka material:

Heater-resistant cast iron (GOST 1412-85)

Top Lengations:

355 mm

Top thickness:

6 mm

Topo tunnel length:

85 mm

Weight:

.2 kg

9000002 Type of heater:

Open

Chimney diameter:

115 mm

Fuel:

Fire

Door Type:

WITHOUT WITH WITHER

Door Model:

DT-4 9000

Doors Material:

2 heat-resistant cast iron (GOST 1412-85)

Furnace door outer size:

290*320 mm

Furnace tunnel:

without extension

0002 Weight of stones in the convector:

20 kg

Water circuit:

No

During this time, hundreds of millions of products made of GOST cast iron have proven their quality, reliability and durability.

In the Soviet Union, the technologies for producing high-quality heat-resistant cast irons were perfected. The composition and characteristics of the resulting cast iron were based on GOST, and as a result of processing a standardized alloy, products of excellent quality were obtained. nine0003

The company Vesuvius in its technological processes relies on many years of experience of the best casters and all cast iron found in Vesuvius products is produced in accordance with GOST 1412-85.

Eurasian Economic Union declarations of conformity BHR (Eurasian_economic_union_declarations_of_compliance_BHR.pdf, 438 Kb) [Download]

TsMID-4 B | ZAO NP TsMID

CONCRETE HARDENING ADDITIVE

Additive TsMID-4B is a composite material based on the additive tsmid-4, which includes additional components that provide a sharp acceleration in the development of the design strength of concrete (up to 40 MPa at the age of 1 day), regardless of the plasticity of concrete mixtures. nine0003

nine0003

Additive TsMID-4B is produced in the form of a fine gray powder, odorless. Additive TsMID-4B is a non-combustible, fire and explosion-proof substance, the introduction of which into the concrete mixture does not change the toxin-hygienic characteristics of concrete.

TsMID-4B is an additive of complex action, with clearly adjusted proportions of the components used, which does not require the introduction of additional additives into the concrete mix.

EFFICIENCY OF ACTION

The use of the multifunctional additive TsMID-4B allows:

- provide 70-80% of the design strength of concrete in the first day of hardening;

- increase formwork turnover; increase the pace of construction work;

- use all the advantages of working with cast concrete mixes;

- provide concrete hardening in conditions of negative temperatures.

Additive TsMID-4B, like all additives of the TsMID-4 group, makes it possible to obtain concretes with high performance properties (VES) , namely: water resistance up to W 20 , increased strength up to 100MPa and frost resistance over F 600 .

Graphs of the curing of concretes with the addition of TsMID-4B and concretes without additives.

Laying of concrete mixtures with the addition of TsMID-4B can be carried out both with the help of vibration compaction and without vibration, when supplied by a concrete pump, through a concrete pipe or bucket. Mixtures are easy to pump and are distinguished by the complete absence of water separation and stratification. nine0003

PROCEDURE FOR APPLICATION OF ADDITIVE CMID-4B

Additive dosage TsMID-4B

- additive consumption per 1 cubic meter concrete mixture is 8.0% -12.0% by weight of cement.

- additive consumption per 1 cubic meter mortar mixture is 9.0% -15.0% of the mass of cement.

Concrete mixing procedure

Additive TsMID-4B is introduced during dosing of bulk components in the following sequence:

nine0371

Options for introducing the additive TsMID-4B:

- automated injection lines:

- big-bag receiver;

- screw conveyor;

- dispenser;

- mixer. - on the sand conveyor belt: the required amount of additive is poured onto the conveyor and fed into the mixer along with the sand.

- The required amount of additive is introduced directly into the mixer during the dosing of the dry ingredients. nine0327

Packing of CMID-4B additive:

| Packaging: | Weight, kg: |

| big bag | 350-530 |

| kraft bag | 16..….27* |

*- packaging in kraft bags is selected based on the convenience of introducing the additive for 1 batch.

Shelf life in the manufacturer's packaging, in a dry place 6 months.

THE TABLE SHOWS THE INDICATIVE COSTS OF THE ADDITIVE DEPENDING ON THE CONTENT OF CEMENT IN 1 M3 OF CONCRETE

|

cement consumption, kg/1 m 3 concrete |

consumption TsMID-4B, kg | flow rate cement, kg/1m 3 concrete |

consumption TsMID-4B, kg |

| 200 | 16. |

100

100