Use of phonics

Phonics Instruction | Reading Rockets

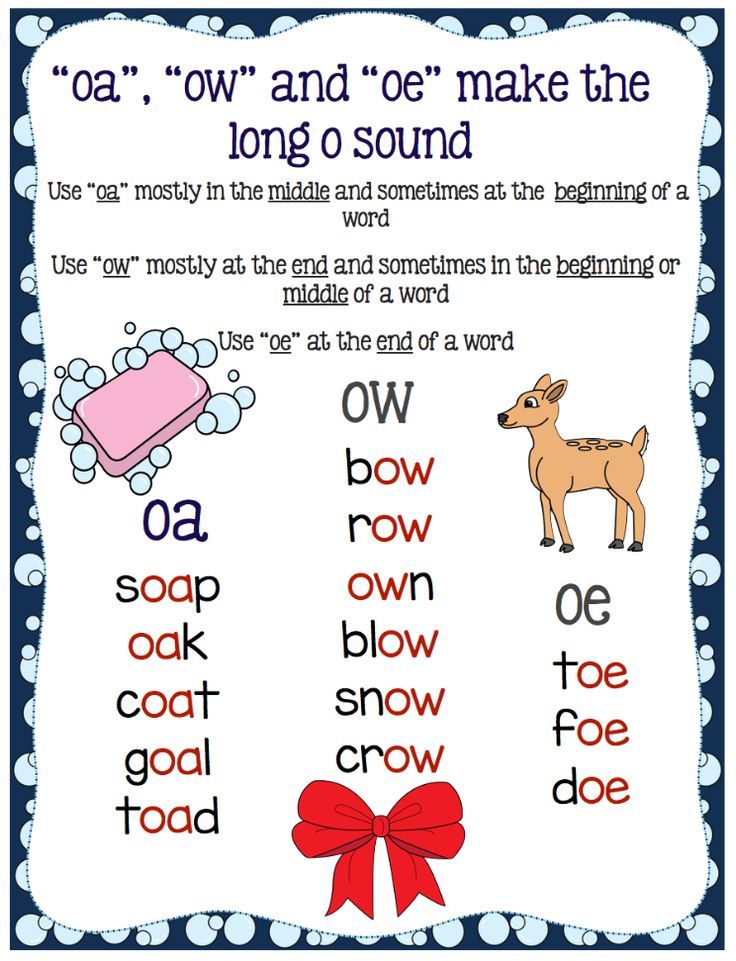

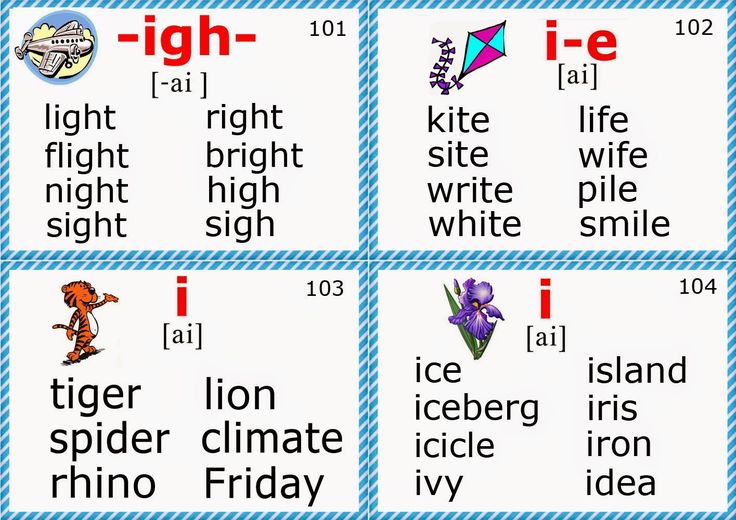

The primary focus of phonics instruction is to help beginning readers understand how letters are linked to sounds (phonemes) to form letter-sound correspondences and spelling patterns and to help them learn how to apply this knowledge in their reading.

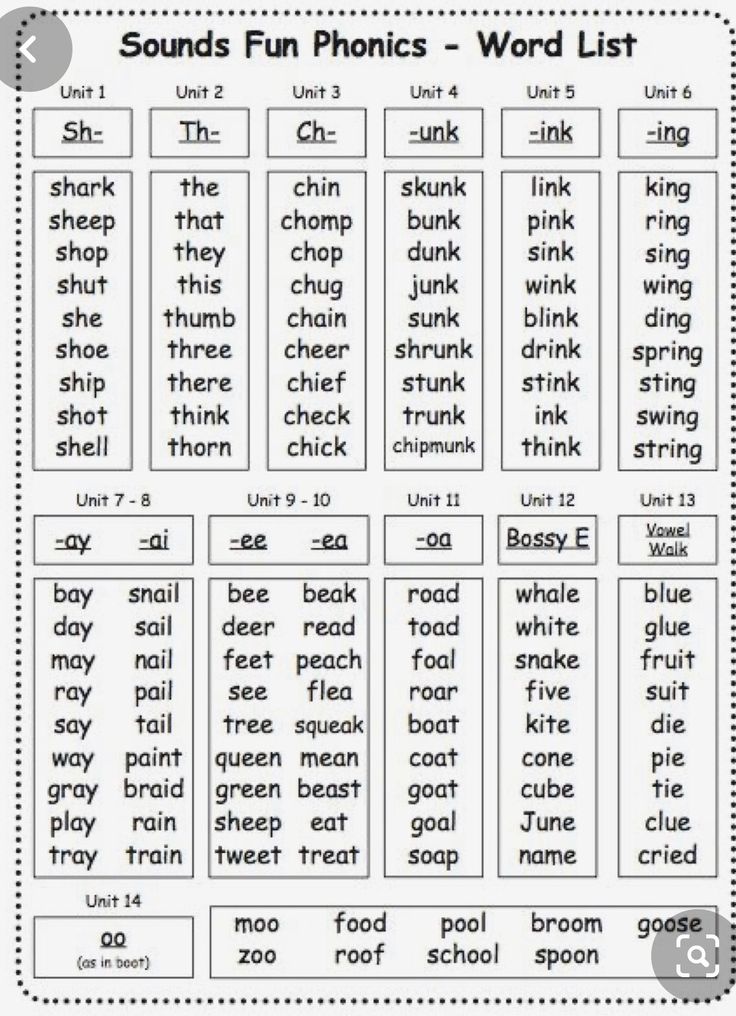

Phonics instruction may be provided systematically or incidentally. The hallmark of a systematic phonics approach or program is that a sequential set of phonics elements is delineated and these elements are taught along a dimension of explicitness depending on the type of phonics method employed. Conversely, with incidental phonics instruction, the teacher does not follow a planned sequence of phonics elements to guide instruction but highlights particular elements opportunistically when they appear in text.

Types of phonics instructional methods and approaches

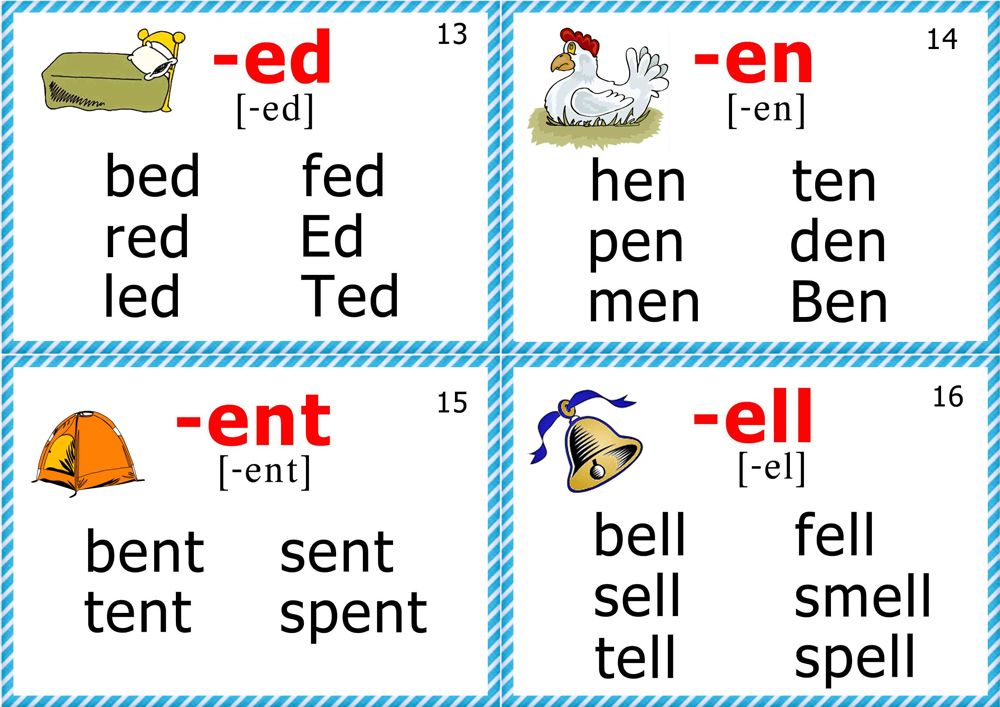

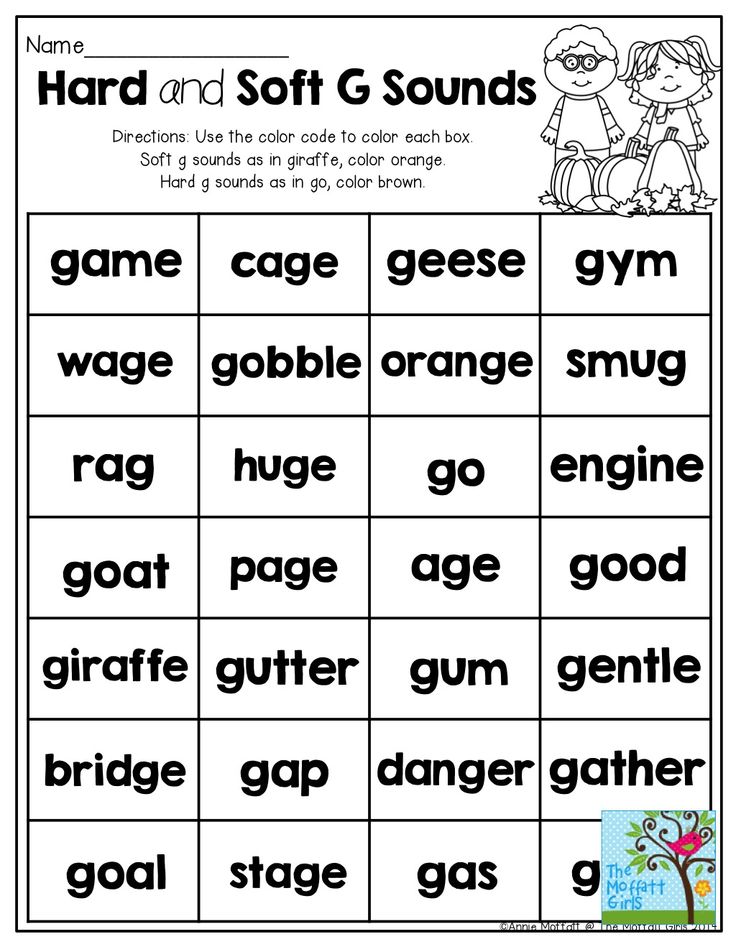

This table depicts several different types of phonics instructional approaches that vary according to the unit of analysis or how letter-sound combinations are represented to the student. For example, in synthetic phonics approaches, students are taught to link an individual letter or letter combination with its appropriate sound and then blend the sounds to form words. In analytic phonics, students are first taught whole word units followed by systematic instruction linking the specific letters in the word with their respective sounds.

Phonics instruction can also vary with respect to the explicitness by which the phonic elements are taught and practiced in the reading of text. For example, many synthetic phonics approaches use direct instruction in teaching phonics components and provide opportunities for applying these skills in decodable text formats characterized by a controlled vocabulary. On the other hand, embedded phonics approaches are typically less explicit and use decodable text for practice less frequently, although the phonics concepts to be learned can still be presented systematically.

- Analogy phonics

Teaching students unfamiliar words by analogy to known words (e.

g., recognizing that the rime segment of an unfamiliar word is identical to that of a familiar word, and then blending the known rime with the new word onset, such as reading

brick by recognizing that -ick is contained in the known word kick, or reading stump by analogy to jump).

g., recognizing that the rime segment of an unfamiliar word is identical to that of a familiar word, and then blending the known rime with the new word onset, such as reading

brick by recognizing that -ick is contained in the known word kick, or reading stump by analogy to jump). - Analytic phonics

Teaching students to analyze letter-sound relations in previously learned words to avoid pronouncing sounds in isolation.

- Embedded phonics

Teaching students phonics skills by embedding phonics instruction in text reading, a more implicit approach that relies to some extent on incidental learning.

- Phonics through spelling

Teaching students to segment words into phonemes and to select letters for those phonemes (i.e., teaching students to spell words phonemically).

- Synthetic phonics

Teaching students explicitly to convert letters into sounds (phonemes) and then blend the sounds to form recognizable words.

Findings and determinations

The meta-analysis revealed that systematic phonics instruction produces significant benefits for students in kindergarten through 6th grade and for children having difficulty learning to read. The ability to read and spell words was enhanced in kindergartners who received systematic beginning phonics instruction. First graders who were taught phonics systematically were better able to decode and spell, and they showed significant improvement in their ability to comprehend text. Older children receiving phonics instruction were better able to decode and spell words and to read text orally, but their comprehension of text was not significantly improved.

Systematic synthetic phonics instruction (see table for definition) had a positive and significant effect on disabled readers' reading skills. These children improved substantially in their ability to read words and showed significant, albeit small, gains in their ability to process text as a result of systematic synthetic phonics instruction. This type of phonics instruction benefits both students with learning disabilities and low-achieving students who are not disabled. Moreover, systematic synthetic phonics instruction was significantly more effective in improving low socioeconomic status (SES) children's alphabetic knowledge and word reading skills than instructional approaches that were less focused on these initial reading skills.

This type of phonics instruction benefits both students with learning disabilities and low-achieving students who are not disabled. Moreover, systematic synthetic phonics instruction was significantly more effective in improving low socioeconomic status (SES) children's alphabetic knowledge and word reading skills than instructional approaches that were less focused on these initial reading skills.

Across all grade levels, systematic phonics instruction improved the ability of good readers to spell. The impact was strongest for kindergartners and decreased in later grades. For poor readers, the impact of phonics instruction on spelling was small, perhaps reflecting the consistent finding that disabled readers have trouble learning to spell.

Although conventional wisdom has suggested that kindergarten students might not be ready for phonics instruction, this assumption was not supported by the data. The effects of systematic early phonics instruction were significant and substantial in kindergarten and the 1st grade, indicating that systematic phonics programs should be implemented at those age and grade levels.

The NRP analysis indicated that systematic phonics instruction is ready for implementation in the classroom. Findings of the Panel regarding the effectiveness of explicit, systematic phonics instruction were derived from studies conducted in many classrooms with typical classroom teachers and typical American or English-speaking students from a variety of backgrounds and socioeconomic levels.

Thus, the results of the analysis are indicative of what can be accomplished when explicit, systematic phonics programs are implemented in today's classrooms. Systematic phonics instruction has been used widely over a long period of time with positive results, and a variety of systematic phonics programs have proven effective with children of different ages, abilities, and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Discussion

These facts and findings provide converging evidence that explicit, systematic phonics instruction is a valuable and essential part of a successful classroom reading program. However, there is a need to be cautious in giving a blanket endorsement of all kinds of phonics instruction.

However, there is a need to be cautious in giving a blanket endorsement of all kinds of phonics instruction.

It is important to recognize that the goals of phonics instruction are to provide children with key knowledge and skills and to ensure that they know how to apply that knowledge in their reading and writing. In other words, phonics teaching is a means to an end.

To be able to make use of letter-sound information, children need phonemic awareness. That is, they need to be able to blend sounds together to decode words, and they need to break spoken words into their constituent sounds to write words. Programs that focus too much on the teaching of letter-sound relations and not enough on putting them to use are unlikely to be very effective.

In implementing systematic phonics instruction, educators must keep the end in mind and ensure that children understand the purpose of learning letter sounds and that they are able to apply these skills accurately and fluently in their daily reading and writing activities.

Of additional concern is the often-heard call for "intensive, systematic" phonics instruction. Usually the term "intensive" is not defined. How much is required to be considered intensive?

In addition, it is not clear how many months or years a phonics program should continue. If phonics has been systematically taught in kindergarten and 1st grade, should it continue to be emphasized in 2nd grade and beyond? How long should single instruction sessions last? How much ground should be covered in a program? Specifically, how many letter-sound relations should be taught, and how many different ways of using these relations to read and write words should be practiced for the benefits of phonics to be maximized? These questions remain for future research.

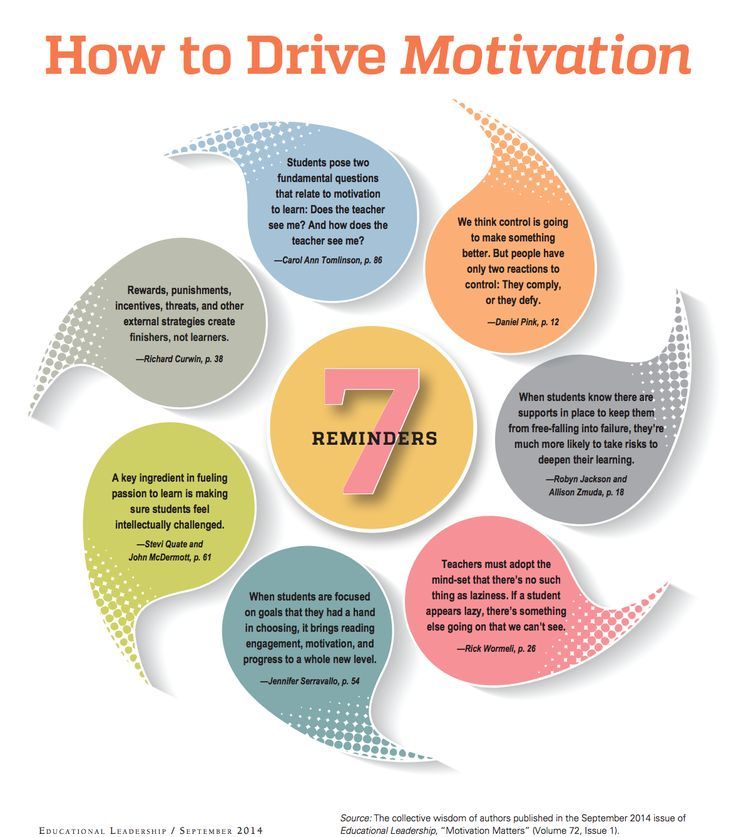

Another important area is the role of the teacher. Some phonics programs showing large effect sizes require teachers to follow a set of specific instructions provided by the publisher; while this may standardize the instructional sequence, it also may reduce teacher interest and motivation.

Thus, one concern is how to maintain consistency of instruction while still encouraging the unique contributions of teachers. Other programs require a sophisticated knowledge of spelling, structural linguistics, or word etymology. In view of the evidence showing the effectiveness of systematic phonics instruction, it is important to ensure that the issue of how best to prepare teachers to carry out this teaching effectively and creatively is given high priority.

Knowing that all phonics programs are not the same brings with it the implication that teachers must themselves be educated about how to evaluate different programs to determine which ones are based on strong evidence and how they can most effectively use these programs in their own classrooms. It is therefore important that teachers be provided with evidence-based preservice training and ongoing inservice training to select (or develop) and implement the most appropriate phonics instruction effectively.

A common question with any instructional program is whether "one size fits all. " Teachers may be able to use a particular program in the classroom but may find that it suits some students better than others. At all grade levels, but particularly in kindergarten and the early grades, children are known to vary greatly in the skills they bring to school. Some children will already know letter-sound correspondences, and some will even be able to decode words, while others will have little or no letter knowledge.

" Teachers may be able to use a particular program in the classroom but may find that it suits some students better than others. At all grade levels, but particularly in kindergarten and the early grades, children are known to vary greatly in the skills they bring to school. Some children will already know letter-sound correspondences, and some will even be able to decode words, while others will have little or no letter knowledge.

Teachers should be able to assess the needs of the individual students and tailor instruction to meet specific needs. However, it is more common for phonics programs to present a fixed sequence of lessons scheduled from the beginning to the end of the school year. In light of this, teachers need to be flexible in their phonics instruction in order to adapt it to individual student needs.

Children who have already developed phonics skills and can apply them appropriately in the reading process do not require the same level and intensity of phonics instruction provided to children at the initial phases of reading acquisition. Thus, it will also be critical to determine objectively the ways in which systematic phonics instruction can be optimally incorporated and integrated in complete and balanced programs of reading instruction. Part of this effort should be directed at preservice and inservice education to provide teachers with decision-making frameworks to guide their selection, integration, and implementation of phonics instruction within a complete reading program.

Thus, it will also be critical to determine objectively the ways in which systematic phonics instruction can be optimally incorporated and integrated in complete and balanced programs of reading instruction. Part of this effort should be directed at preservice and inservice education to provide teachers with decision-making frameworks to guide their selection, integration, and implementation of phonics instruction within a complete reading program.

Teachers must understand that systematic phonics instruction is only one component – albeit a necessary component – of a total reading program; systematic phonics instruction should be integrated with other reading instruction in phonemic awareness, fluency, and comprehension strategies to create a complete reading program.

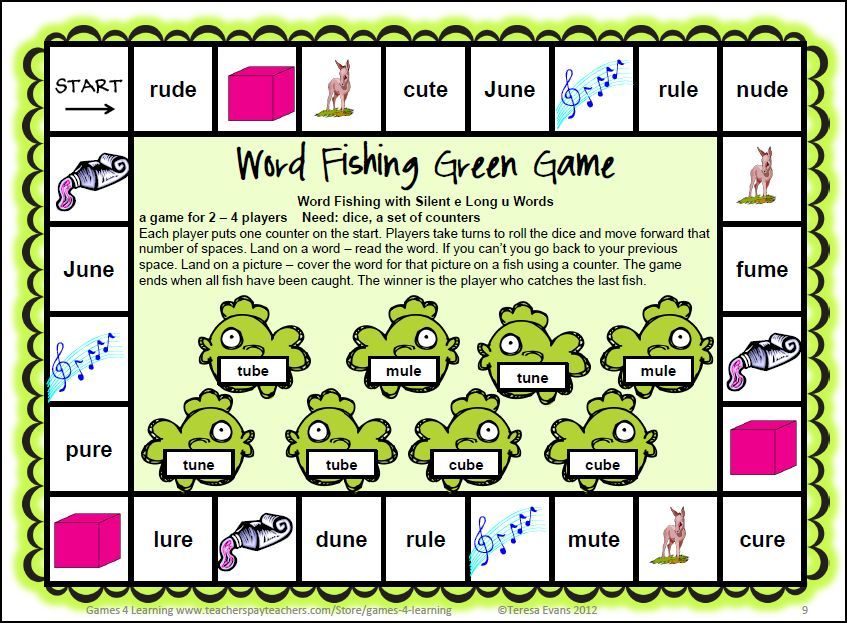

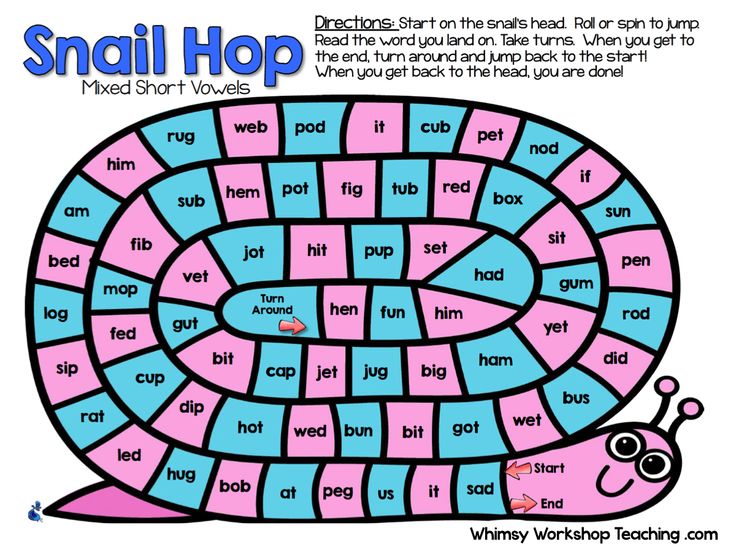

While most teachers and educational decision-makers recognize this, there may be a tendency in some classrooms, particularly in 1st grade, to allow phonics to become the dominant component, not only in the time devoted to it, but also in the significance attached. It is important not to judge children's reading competence solely on the basis of their phonics skills and not to devalue their interest in books because they cannot decode with complete accuracy. It is also critical for teachers to understand that systematic phonics instruction can be provided in an entertaining, vibrant, and creative manner.

It is important not to judge children's reading competence solely on the basis of their phonics skills and not to devalue their interest in books because they cannot decode with complete accuracy. It is also critical for teachers to understand that systematic phonics instruction can be provided in an entertaining, vibrant, and creative manner.

Systematic phonics instruction is designed to increase accuracy in decoding and word recognition skills, which in turn facilitate comprehension. However, it is again important to note that fluent and automatic application of phonics skills to text is another critical skill that must be taught and learned to maximize oral reading and reading comprehension. This issue again underscores the need for teachers to understand that while phonics skills are necessary in order to learn to read, they are not sufficient in their own right. Phonics skills must be integrated with the development of phonemic awareness, fluency, and text reading comprehension skills.

Explaining Phonics Instruction | Reading Rockets

By: International Literacy Association

This ILA brief explains the basics of phonics for parents, offering guidance on phonics for emerging readers, phonological awareness, word study, approaches to teaching phonics, and teaching English learners.

This 2018 brief explains the what, the when and the how of phonics instruction to parents, offering guidance on phonics for emerging readers, phonological awareness, word study, approaches to teaching phonics, and teaching English learners.

Key takeaways:

- Students should have acquired phonological awareness, concepts of print, concepts of word of text and alphabetic principles before beginning to learn phonics.

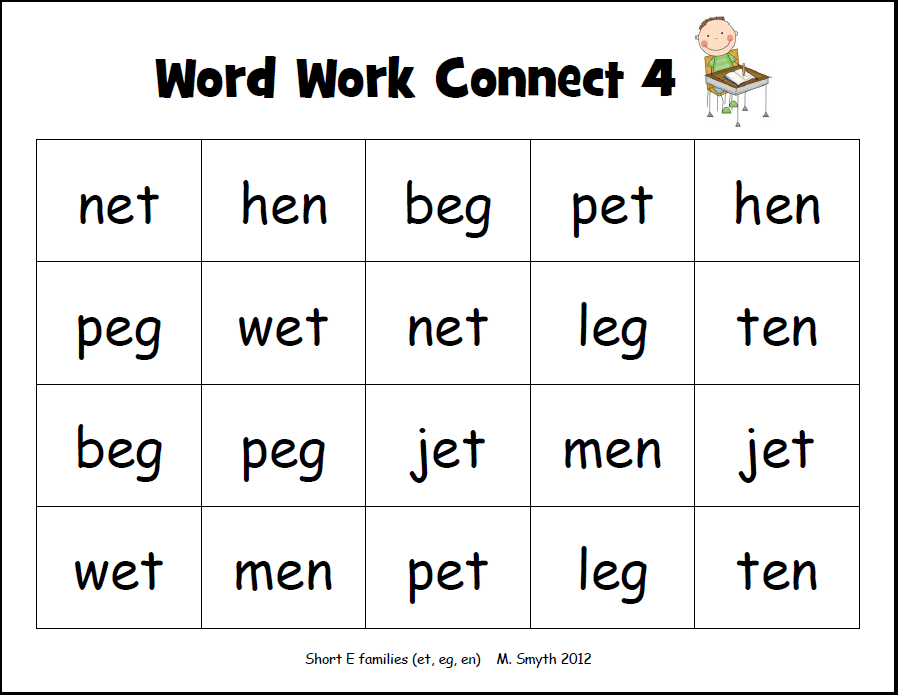

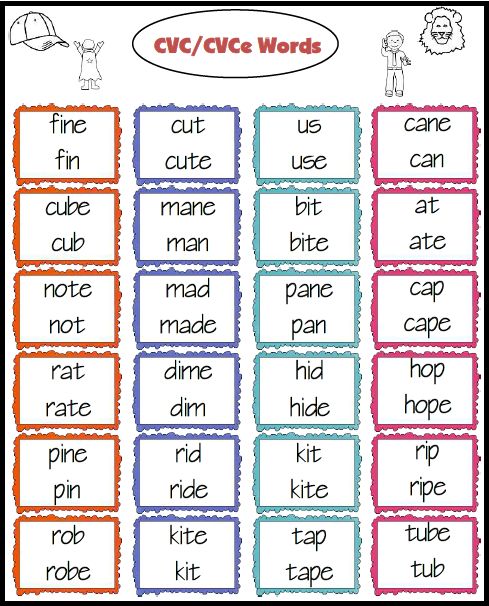

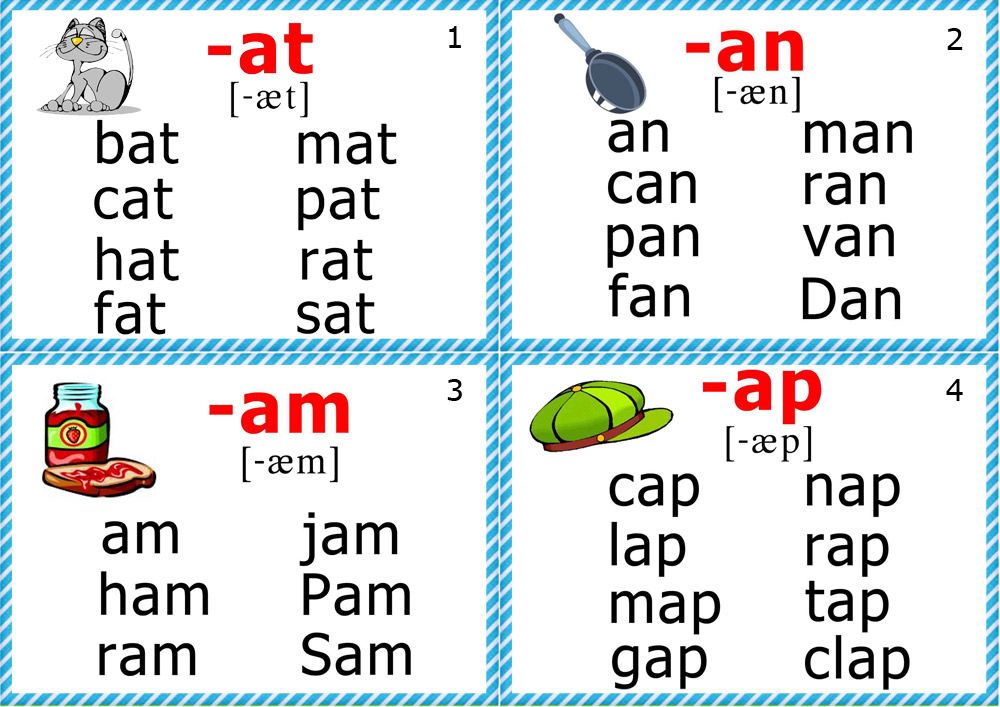

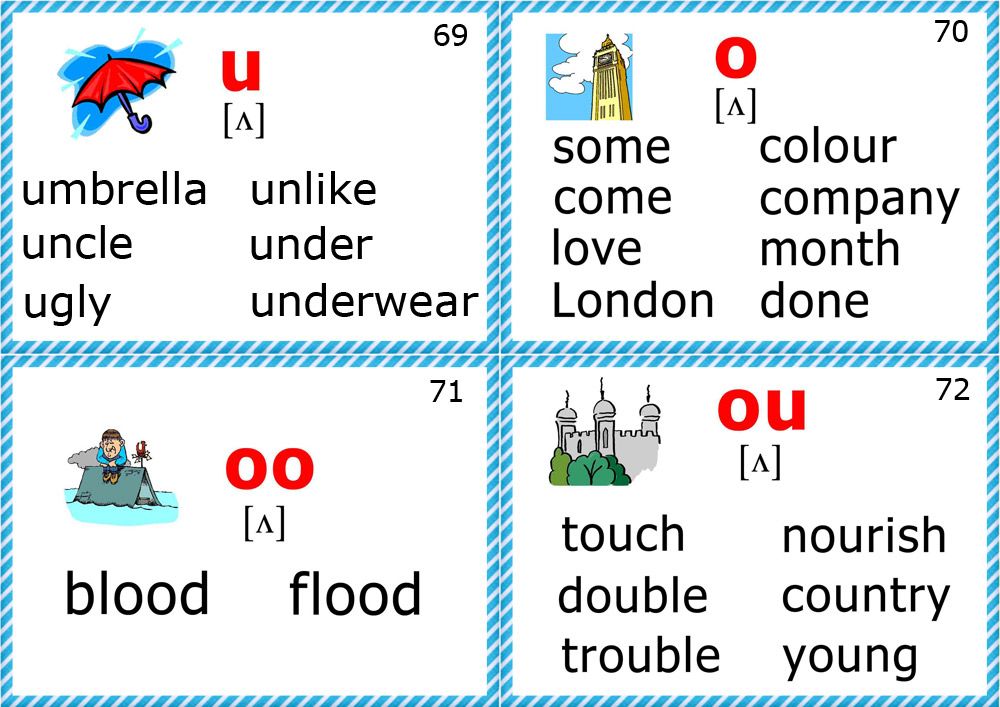

- Most phonics programs incorporate both analytic and synthetic activities. In analytic instruction, students compare words to identify patterns and apply this knowledge to new words (e.g., ran/can), or they examine word families to make analogies between segments of words (e.

g., onset and rime, r-an/c-an/f-an/m-an/p-an). In synthetic phonics, students blend individual letter sounds together to form words (e.g., c-a-t/cat).

g., onset and rime, r-an/c-an/f-an/m-an/p-an). In synthetic phonics, students blend individual letter sounds together to form words (e.g., c-a-t/cat). - Word study is an approach to teach the alphabetic layer (basic letter–sound correspondences) and pattern layer (consonant–vowel patterns) of the writing system by including spelling instruction that is differentiated by students’ development.

- Phonics instruction depends on the characteristics of a specific language; students who learn to read in multiple languages apply phonics that fit the respective letter–sound, pattern and meaning layers.

- Emergent bilingual readers and writers use their knowledge of one language to learn other languages.

See the full brief, Explaining Phonics Instruction: An Educator’s Guide.

International Literacy Association (2018)

Reprints

You are welcome to print copies for non-commercial use, or a limited number for educational purposes, as long as credit is given to Reading Rockets and the author(s). For commercial use, please contact the author or publisher listed.

For commercial use, please contact the author or publisher listed.

Related Topics

Early Literacy Development

Phonics and Decoding

Spelling and Word Study

New and Popular

Cracking the Code: How and Why Big Horn Elementary School Went All-In with Structured Literacy

Print-to-Speech and Speech-to-Print: Mapping Early Literacy

100 Children’s Authors and Illustrators Everyone Should Know

A New Model for Teaching High-Frequency Words

7 Great Ways to Encourage Your Child's Writing

Screening, Diagnosing, and Progress Monitoring for Fluency: The Details

Phonemic Activities for the Preschool or Elementary Classroom

Our Literacy Blogs

What’s the Role of Amount of Reading Instruction?

Kids and educational media

Meet Ali Kamanda and Jorge Redmond, authors of Black Boy, Black Boy: Celebrating the Power of You

Get Widget |

Subscribe

Phonetics

(from Greek φωνητικός - sound, voice) - a branch of linguistics that studies the sound side of the language. Unlike other linguistic disciplines phonetics explores not only the language function, but also the material side its object: the work of the pronunciation apparatus, as well as the acoustic characteristics of sound phenomena and their perception by native speakers. Modern phonetics distinguishes in sound four aspects of speech: functional (or linguistic), articulatory, acoustic and perceptual. Phonetics is associated with such non-linguistic disciplines as anatomy and physiology of speech production and speech perception, on the one hand, and acoustics of speech - with another. Like linguistics in general, phonetics is associated with psychology, since speech activity is part of mental human activity.

Unlike other linguistic disciplines phonetics explores not only the language function, but also the material side its object: the work of the pronunciation apparatus, as well as the acoustic characteristics of sound phenomena and their perception by native speakers. Modern phonetics distinguishes in sound four aspects of speech: functional (or linguistic), articulatory, acoustic and perceptual. Phonetics is associated with such non-linguistic disciplines as anatomy and physiology of speech production and speech perception, on the one hand, and acoustics of speech - with another. Like linguistics in general, phonetics is associated with psychology, since speech activity is part of mental human activity.

Unlike non-linguistic disciplines, phonetics deals with sound phenomena as elements of the language system, serving to translate words and sentences into a material sound form, without which communication is impossible. Outside of this function, the sound side of the language cannot be understood; even a single sound of speech stands out from the sound chain only as a representative of the phoneme, i. e. due to its connections with the semantic units of the language. Data of modern acoustics of speech indicate that the elements of articulation of the sound sequence, carried out by the most perfect acoustic methods do not coincide with speech sounds as realizations phonemes.

e. due to its connections with the semantic units of the language. Data of modern acoustics of speech indicate that the elements of articulation of the sound sequence, carried out by the most perfect acoustic methods do not coincide with speech sounds as realizations phonemes.

In accordance with the fact that the sound side of the language can be considered in acoustic-articulatory and functional-linguistic aspects, in phonetics distinguish between phonetics and phonology. Dividing them into two independent section of linguistics, many modern linguists considered unlawful.

Allocate general and private phonetics, or the phonetics of individual languages. General phonetics studies general sound generation conditions, based on the possibilities human pronunciation apparatus (for example, labial, front-lingual, back-lingual consonants, if refers to the pronunciation organ that determines the main features consonant, or stop, slotted, if we mean the method of formation necessary for the articulation of a consonant barrier for the jet of air leaving the lungs), and also analyzes acoustic features of sound units, their spectral characteristics, such as the presence or absence of a pitch of voice (zero formant) when pronouncing different types of consonants, different the position of formants in the formation of vowels. Universal classifications of speech sounds (vowels and consonants), which are based partly on articulatory, partly on acoustic signs, as well as classification according to differential signs. General phonetics also studies the patterns of combinations of sounds, influences features of one of the neighboring sounds to another (different types of accommodation or assimilation), coarticulation; the nature of the syllable, the laws of combining sounds into syllables and factors causing syllable division; phonetic organization of words in particular stress and synharmonism. She studies the means that used for intonation: the pitch of the main tone of voice, strength (intensity), duration of individual parts sentences, the speed of their pronunciation (tempo), pauses and timbre.

Universal classifications of speech sounds (vowels and consonants), which are based partly on articulatory, partly on acoustic signs, as well as classification according to differential signs. General phonetics also studies the patterns of combinations of sounds, influences features of one of the neighboring sounds to another (different types of accommodation or assimilation), coarticulation; the nature of the syllable, the laws of combining sounds into syllables and factors causing syllable division; phonetic organization of words in particular stress and synharmonism. She studies the means that used for intonation: the pitch of the main tone of voice, strength (intensity), duration of individual parts sentences, the speed of their pronunciation (tempo), pauses and timbre.

In private phonetics, all these problems are considered in relation to this particular language and through the prism of functions, which perform this or that phonetic phenomenon or unit. Particular phonetics can be descriptive, or synchronous (see Synchrony), and historical, or diachronic (see Diachrony), studying the evolution of the sound structure of a given language or group of languages.

Phonetic and phonological aspects are presented in private phonetics a single whole, since all sound units are allocated indirectly through the semantic units of the language.

Phonetics widely uses experimental methods; since special devices are used, these methods are also called instrumental. These include: palatography (static and dynamic), with which places of contact of the tongue with the palate are established at sound production, tensopalatography to measure the strength of articulation, radiography, which allows you to see the position of the speech organs and their movement (with film x-ray), oscillography, which allows you to determine the duration, height and intensity of sounds, and spectrography, giving the overall acoustic sound picture. In phonetics, in addition, various methods are used studying the perception of certain sound phenomena by native speakers, which especially important for the phonological interpretation of these phenomena. In the 80s computers began to be used in phonetics.

Phonetics has an applied value in different areas: for streamlining writing (graphics and spelling), teaching correct pronunciation, especially non-native language, for diagnosing the correction of speech deficiencies (speech therapy and deaf pedagogy). Phonetic data is used to verify funds communications and to improve their efficiency, as well as for automatic speech recognition.

The beginning of the study of the mechanism of formation of speech sounds dates back to the 17th century; it was caused by the needs of teaching the deaf and dumb (work H. P. Bonet, J. Wallis, I. K. Amman). At the end of the 18th century H. Krazenstein laid the foundation for the acoustic theory of vowels, which was developed in mid 19V. G. L. F. Helmholtz. By the middle of the 19th century. research in the areas of anatomy and physiology of sound production have been summarized in works of E. W. Brücke. From a linguistic point of view, the doctrine of sound side of the language in all its sections was first presented in the work E. Sievers "Grundzüge der Lautphysiologie" (1876; 2nd ed. - under the name "Grundzüge der Phonetik", 1881). An important role in the development of phonetics was played by the books of G. Suit, O. Jespersen, M. Grammon and others. In Russia, a significant role in the development of general phonetics was played by the works of I. A. Baudouin de Courtenay, as well as his students - V. A. Bogoroditsky and L. V. Shcherba: it was Baudouin de Courtenay and Shcherba laid the foundation for the theory of the phoneme (phonology). big the works of A. I. Thomson ("General Linguistics", 1906). In Soviet linguistics, the problems of general and particular phonetics (works by R.I. Avanesov, L.R. Zinder, M.I. Matusevich, A.A. Reformatsky and others).

Sievers "Grundzüge der Lautphysiologie" (1876; 2nd ed. - under the name "Grundzüge der Phonetik", 1881). An important role in the development of phonetics was played by the books of G. Suit, O. Jespersen, M. Grammon and others. In Russia, a significant role in the development of general phonetics was played by the works of I. A. Baudouin de Courtenay, as well as his students - V. A. Bogoroditsky and L. V. Shcherba: it was Baudouin de Courtenay and Shcherba laid the foundation for the theory of the phoneme (phonology). big the works of A. I. Thomson ("General Linguistics", 1906). In Soviet linguistics, the problems of general and particular phonetics (works by R.I. Avanesov, L.R. Zinder, M.I. Matusevich, A.A. Reformatsky and others).

- Matusevich M.I., Introduction to general phonetics, 3rd ed., M., 1959;

- Zinder L. R., General phonetics, [L.], 1960; 2nd ed., M., 1979;

- Speech. Articulation and perception, M. - L., 1965;

- Bondarko L.

V. Oscillographic analysis of speech, [L.], 1965;

V. Oscillographic analysis of speech, [L.], 1965; - Reformed A. A., Introduction to Linguistics, M., 1967;

- Abercrombie D., Elements of general phonetics, Edinburgh, 1967;

- Manual of phonetics, Amst., 1968;

- Malmberg B., La phonetique, P., 1968;

- aka , Einführung in die Phonetik als Wissenschaft, Münch., 1976;

- Pilch H., Phonemtheorie, 3 Aufl., Tl 1, Basel, 1974;

- Zwirner E., Zwirner K., Grundfragen der phonometrischen Linguistik, 3 Aufl., Basel, 1982.

L. R. Zinder.

Phonetics, phonetic means / Babylon :: lingvo.info

- Phonetics, phonetic means

"The sounds we make" - Morphology

"Words, how they are formed and how they change" - Syntax

"How to put words into a sentence" - Semantics, vocabulary

"Meanings behind the words"

Phonetics and phonology

Phonetics is a branch of linguistics that studies the sounds of human speech. The term is also used for sign languages, where she explores the gestural and visual components of signs.

The term is also used for sign languages, where she explores the gestural and visual components of signs.

Phonetics investigates the physiological production, transmission and perception of sounds. Phonology deals with the structure of the sound system in the language. Here phonemes play a special, important role. Phonemes are the smallest distinguishable units that are the building blocks in words (speech or sign language).

Transcription

Phonetic transcription is a way of representing the sounds found in human languages, regardless of the written form of the language. The best known systems are the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), which is mostly based on the Latin alphabet with the ability to describe speech characteristics such as consonants, vowels, and suprasegmental features. It was developed by the International Phonetic Association to standardize the representation of human speech sounds. IPA is used by lexicographers, singers, actors, authors of artificial languages, and translators.

Official IPA scheme as of 2005 (CC-BY-SA license)

Relationship between background (fon) and phoneme

Background (fon) is the basic unit of speech flow; A phoneme is the basic unit of speech in a given language. The phoneme is the abstract unit for a given language and will include a number of different backgrounds. This is reflected in different levels of transcription. The purpose of phonetic transcription (usually in square brackets) is to transcribe sounds (phones) to record accurate articulation, while phonemic (phonemic, phonological) (usually with slashes) transcribes words in terms of sound categories in a given language. The line between phonemic and phonetic transcriptions is not always clear - narrow phonetic transcription captures more variants of sounds, while broad phonetic transcription captures only the most prominent features and puts them into phonemic transcriptions.

For example, a normal pronunciation of an English word in a narrow transcription would look like this: [ɹ̠ʷɛd], where [ɹ] would be a reflection of the American (alveolar approximant/alveolar fricative sonorant), but the minus sign below it indicates that it is pronounced with a drawn out slightly back with the tongue (produced deeper in the mouth than usual), and [ʷ] means labialization (lips are slightly rounded).