What are letter names

When to Teach Letter Names

by Shirley Houston

I recently received an email posing this question:

We are teaching systematic phonics to our little ones, but we are conflicted as when to teach letter names. When and how should letter names be taught to children?”

The timing of the introduction of letter names is important, so I’ll frame my thoughts using the Goldilocks principle – not too early, not too late, but at just the right time. It is a developmental concern, rather than a grade/year- or age-related concern.

Not Too Early

Should you teach letter names or sounds first?

Letters are used as a code for the sounds in our speech so are meaningless without knowledge of the sounds. Any squiggle/shape could represent a sound, for example:

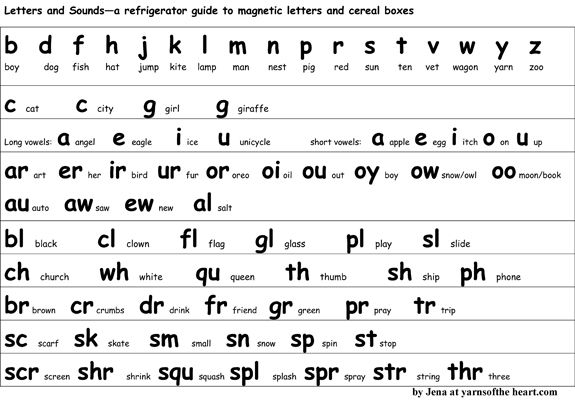

Letter names provide abstract labels for the letters, not representations of how the letters actually sound within our language. That is why teaching a child to sing the alphabet song before the child receives formal reading instruction has limited value. The first important step towards literacy success is development of phonemic awareness and not letter name singing.

Why not teach letter names and sounds together?

So, if letters make no sense without sounds, why not teach letter sounds and names side by side? The simple answer is because of the cognitive load. Working memory has to work hardest when a task is novel and therefore has a heavy cognitive load. For the beginning learner, identifying individual sounds in a word, from left to right, is quite a novel task. Forming letter shapes and discriminating between letter shapes are novel tasks. Remembering the name of a letter is a novel task. Linking a specific letter with a specific sound is a novel task.

Is it any wonder that some children, especially those with a weak working memory, struggle with reading and spelling? Cognitive load theory makes it clear that we can and should do what is necessary to reduce cognitive load. It is not necessary for school beginners to know the names of letters for reading and spelling, so, in my opinion, the teaching of letter names should be postponed until letter names are necessary. This allows students to begin to write and read more quickly.

It is not necessary for school beginners to know the names of letters for reading and spelling, so, in my opinion, the teaching of letter names should be postponed until letter names are necessary. This allows students to begin to write and read more quickly.

Teach letter-sound correspondences initially, without teaching letter names

Students need to learn letter-sound correspondences for reading and spelling. When a beginning reader is learning the single letter-sound correspondences, you do have to talk about the squiggles we make for sound symbols as ‘letters’, but that does not mean that you should refer to the letter names. Instead, the teacher can say:

or

When the child is spelling, the prompt can be:

Teaching letter names too early can confuse beginning readers

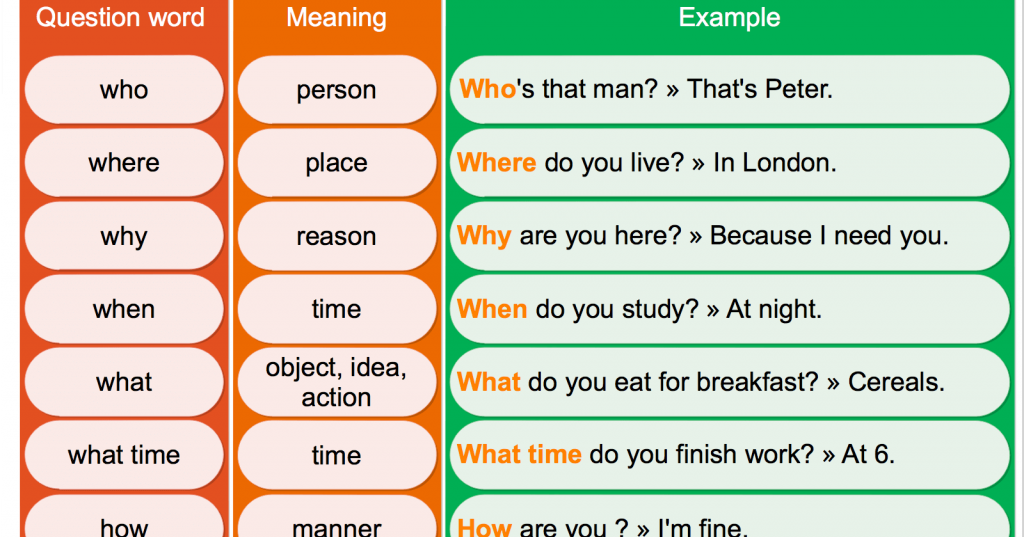

Letter names will not help a child to decode words: the word ‘cat’ is not read as ‘seeaytee’. While some may argue that teachers can use aspects of letter names as cues for students to identify the sounds they represent, the potential for confusion outweighs any benefits if letter names are introduced too early.

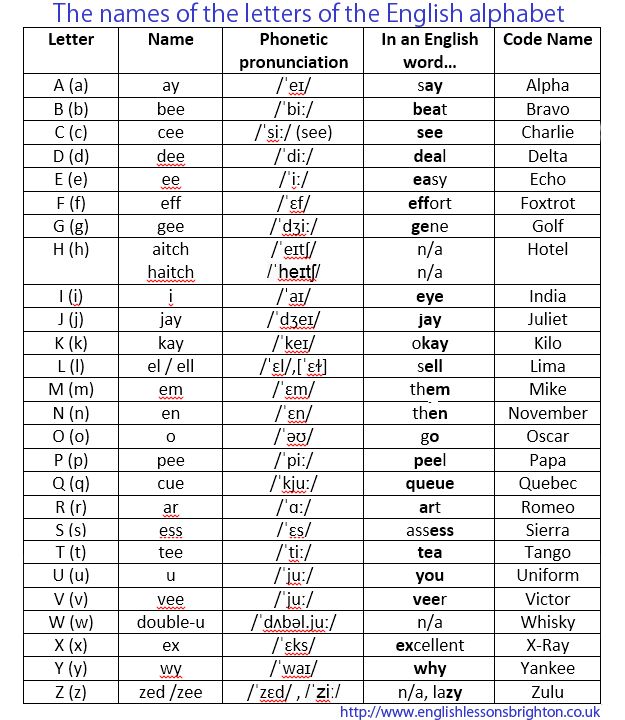

Children learning to read who have received more instruction in letter names than letter sounds are more likely to look at a word and read:

| ‘w’ | /d/ (for ‘doubleyou’) – refers to the shape of the letter, not the sound |

| ‘y’ | /w/ (for ‘why’) |

| ‘u’ | /y/ (for ‘you’) |

| ‘c’ | /s/ (for ‘see’) – this is less common than /k/ |

| ‘g’ | /j/ (for ‘jee’) – this is less common than hard /g/ |

| ‘h’ | long /a/ (as in ‘aitch’) |

| ‘f’, ‘l’, ‘m’, ‘n’, ‘s’, ‘x’ | short /e/ (as in ‘ef’, ‘el’, ‘em’, ‘en’, ‘es’, ‘ex’) |

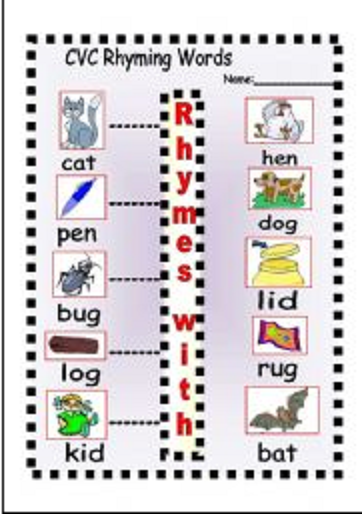

If they are taught letter names before letter sounds, beginning readers will expect vowel letters to represent a long vowel sound in words, reading, for example, ‘got’ as ‘goat’. The most common sound represented by a vowel letter is its short sound, and it is usually VC and CVC words, containing short vowel sounds, to which beginning readers are first exposed.

The most common sound represented by a vowel letter is its short sound, and it is usually VC and CVC words, containing short vowel sounds, to which beginning readers are first exposed.

…and beginning spellers

Children learning to spell who have received more instruction in letter names than letter sounds are more likely to use letter names in their spelling e.g.

Not Too Late

It will be harder for a teacher to help children who have not been taught letter names with their spelling. In the photo below, you can see what a five-year-old, who doesn’t know the letter names, produced when she asked how to spell ‘bean’ and the parent responded with letter names:

If a child asks how to spell the long /ee/ sound in ‘beach’, it is not appropriate to say “Write /eh/ then /ah/”, because blending those sounds together does not create the long /ee/ sound. You must use letter names e. g. “We spell the long /ee/ sound in ‘beach’ with the letter ‘e’ followed by the letter ‘a’. They make a

vowel team.” Similarly, if you ask a child how ‘seek’ is spelled, it is not sufficient for the child to say “/s/, long /ee/, /k/” because there are several possible spellings for each of those sounds. Developing the language that allows discussion of letter-sound correspondences is important to reading and spelling success.

g. “We spell the long /ee/ sound in ‘beach’ with the letter ‘e’ followed by the letter ‘a’. They make a

vowel team.” Similarly, if you ask a child how ‘seek’ is spelled, it is not sufficient for the child to say “/s/, long /ee/, /k/” because there are several possible spellings for each of those sounds. Developing the language that allows discussion of letter-sound correspondences is important to reading and spelling success.

When you are helping a child to encode or decode an irregular tricky word, you need to be able to draw attention to the parts that are not regular, for example by saying “The letters ‘a’ and ‘i’ together in this word, ‘said’, are representing the short /e/ sound.” Irregular words cannot be fully sounded out so knowledge of letter-sound correspondences is insufficient.

Just the Right Time

Research indicates that letter name instruction will actually strengthen letter sound knowledge. When a student understands the way in which the alphabetic code works, letter names become important. Many letters have more than one possible sound, and many sounds can be produced by a variety of different letters, so it is important to be able to reference each letter independently of the sound it makes.

Many letters have more than one possible sound, and many sounds can be produced by a variety of different letters, so it is important to be able to reference each letter independently of the sound it makes.

Teach letter names when they are needed:

To talk about alternative spellings

e.g.

Teach letter names as soon as you need to talk about alternate spellings in reading and/or spelling. Typically, the first time you need to do this will be when students learn that ‘c’, ‘k’ and ‘ck’ are all alternatives for spelling /k/. You will need to talk about where children will see these alternatives:“We usually see the letter ‘k’ representing /k/ before an ‘e’ or ‘i’ at the beginning of a word.”

“The letter ’c’ usually represents /k/ before an ‘a’, ‘o’ or ‘u’.”

“We use the letters ‘c’ and ‘k’ together after a weak vowel at the end of a word.”

Letter names must be taught for discussion of digraphs e.

g. “Because we have 44 sounds but only 26 letters in English, we have to combine some letters. The two-letter combination of ‘c’ and ‘h’ represents the sound /ch/.” When the alternative spellings of long /ee/ are taught (ea, ee, ie, ei, ey) it is no longer sufficient to just refer to ‘two-letter e’ – you must name the vowels that can be combined to represent a vowel sound, and their order.

g. “Because we have 44 sounds but only 26 letters in English, we have to combine some letters. The two-letter combination of ‘c’ and ‘h’ represents the sound /ch/.” When the alternative spellings of long /ee/ are taught (ea, ee, ie, ei, ey) it is no longer sufficient to just refer to ‘two-letter e’ – you must name the vowels that can be combined to represent a vowel sound, and their order.To talk about capital letters

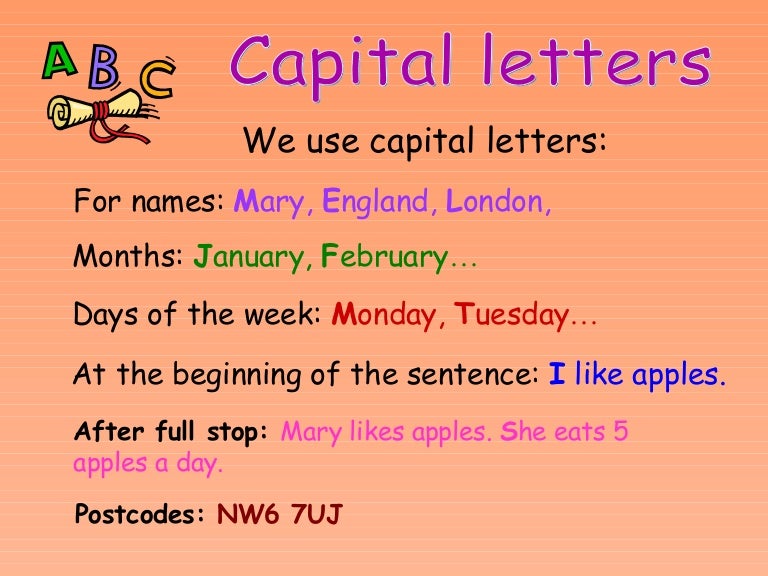

If you are teaching students about the use of a capital letter at the beginning of a sentence or name, you must refer to a letter name. There is no such thing as a capital sound! You will also need to refer to letter names when helping children to recognise letters when reading text in different fonts.To communicate the spelling of a word to someone else

Familiarity with letter names allows the teacher to respond, from a distance, to the question “How do I spell the /ie/ in ‘night’?” with “It’s the i-g-h spelling”, rather than having to go and write it down for the child. When someone asks you to spell your name, do you give him/her the sounds of your name or do you provide the letter names? Of course, you give the latter. Not to do so would require the person to go through every alternative representations of the sounds and make a choice. That could take a lot of time if your name was derived from another alphabet, like ‘Siobhan’! Consequently, a teacher may have to teach specific letter names earlier to a child with a name that cannot be sounded out easily or has an unusual spelling.

When someone asks you to spell your name, do you give him/her the sounds of your name or do you provide the letter names? Of course, you give the latter. Not to do so would require the person to go through every alternative representations of the sounds and make a choice. That could take a lot of time if your name was derived from another alphabet, like ‘Siobhan’! Consequently, a teacher may have to teach specific letter names earlier to a child with a name that cannot be sounded out easily or has an unusual spelling.To teach homophones

When the sounds of two words are the same, you must be able to describe them using their letter names. e.g. “The ‘bean’ you eat is spelled with the letters ‘e’ and ‘a’, as in the word ‘eat’. The other ‘been’ is the past tense of ‘be’ and is spelled with two e’s.”

How Do You Teach Letter Names?

Follow the order of your synthetic phonics program in choosing which letter names to teach, when. Using our earlier example, the c/k/ck alternative spellings of /k/ are the first typically met in a synthetic phonics program (in level 6 of Phonics Hero’s Playing with Sounds order and level 2A of Letters and Sounds, so these should probably be taught first, then the letters that make up consonant digraphs (l, s, f, h, t, w, n and g).

Using our earlier example, the c/k/ck alternative spellings of /k/ are the first typically met in a synthetic phonics program (in level 6 of Phonics Hero’s Playing with Sounds order and level 2A of Letters and Sounds, so these should probably be taught first, then the letters that make up consonant digraphs (l, s, f, h, t, w, n and g).

Teach the most common letter names first, the less common letter names last (q, z, x.). Every syllable of every word must have a vowel sound and there are many alternative spellings of vowel sounds, so it is very important that students have a sound knowledge of these.

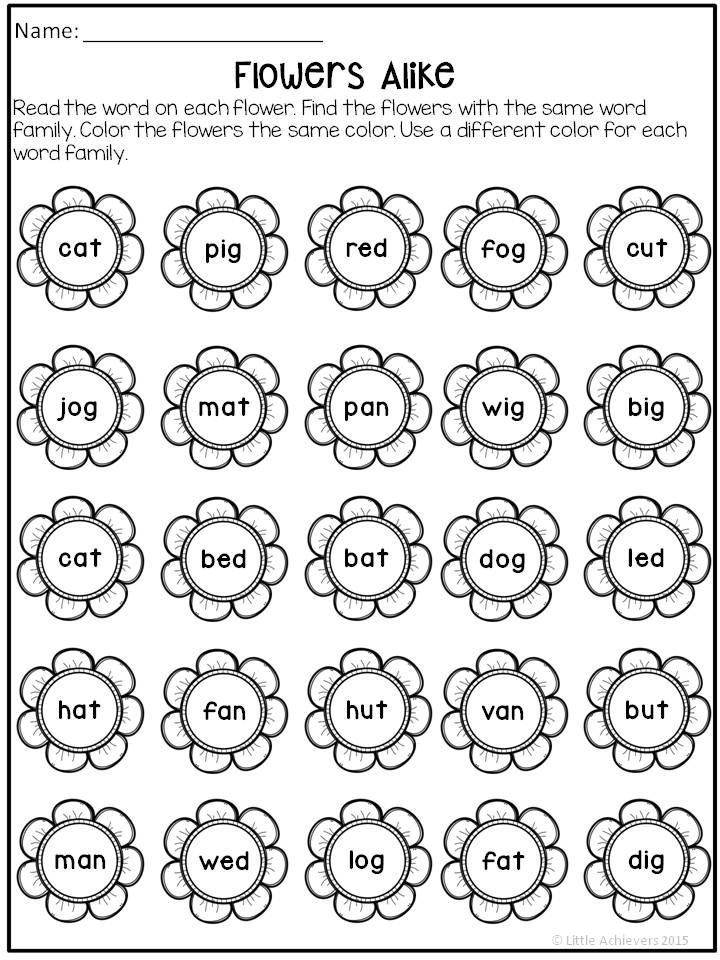

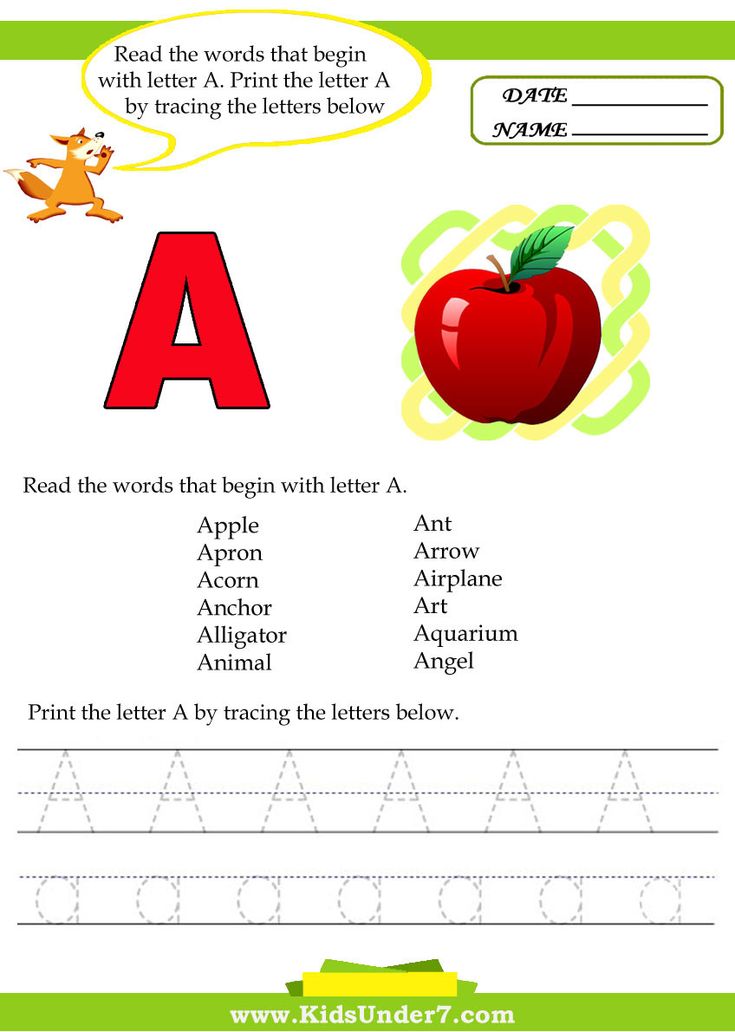

In order to have true fluency in letter recognition, children must be able to identify letters and say their names in and outside of context and in and out of sequence. It’s not just accuracy, but also automaticity, that contributes to long-term literacy success. Here are a few ideas for developing automaticity in letter naming:

- Direct instruction: “This letter’s name is __.

What letter is it? Point to another ___ on the board.”

What letter is it? Point to another ___ on the board.” - Teach letter names alongside letter formation. Have the child say the name of the letter as he or she writes it.

Have a letter of the day and reward the child for finding that letter in the classroom, in a shared book, etc. Print our free Letter of the Day poster and use it to display the letter at the front of your classroom.

Letter searches: “Circle each letter ‘p’ in this line of letters.”

- Bingo: Call out a letter name and have the child place a counter on the corresponding letter. We’ve created a free Letter Name Bingo template you can use.

- Have the student pull a letter out of a mystery bag, a sandbox etc and name it.

- Use the child’s name and other family names to practise letter recognition.

- Print out letters on paper or write them with chalk. Have children jump on/run to a letter when you call out a letter name.

Once the student can accurately name all 26 letters, return your focus to letter-sound correspondences. There are many more sounds than letters to learn and knowledge of those correspondences are key to reading and spelling successfully!

Still have questions about how or when to teach letter names to children? Leave us a comment below!

Author: Shirley Houston

With a Masters degree in Special Education, Shirley has been teaching children and training teachers in Australia for over 30 years. Working with children with learning difficulties, Shirley champions the importance of teaching phonics systematically and to mastery in mainstream classrooms. If you are interested in Shirley’s help as a literacy trainer for your school, drop the team an email on [email protected]Letter Names or Sounds First?

Teacher question:

I teach kindergarten. We are trying to follow the science of reading. We believe that is the best way to go. However, my colleague and I are disagreeing over one aspect of our program. Should we teach the letters first, the sounds first, or should we teach them together?

However, my colleague and I are disagreeing over one aspect of our program. Should we teach the letters first, the sounds first, or should we teach them together?

Shanahan response:

This is such a practical question and often research fails to answer such questions. That shouldn’t be too surprising since researchers approach reading a bit differently than the classroom teacher. A good deal of psychological study of letters and words over the past century hasn’t been so much about how best to teach reading as much as an effort to understand how the human mind works.

In this case, there is a research record that at least provides some important clues as to what the best approach may be.

There has been some disagreement over whether it is a good idea to teach letter names at all. Back in the 1970s, S.J. Samuels conducted some small studies with an artificial orthography and found that the “letter” names were neither necessary nor useful for college students learning to read this new spelling system. Later, Diane McGuiness (2004) in her popular book argued against teaching letter names because they can be a hindrance in some situations. An example of this were my first graders who figured that “what” must begin with the /d/ sound (using the name of the letter “w” as a clue to its sound, an approach that works often but not always).

Later, Diane McGuiness (2004) in her popular book argued against teaching letter names because they can be a hindrance in some situations. An example of this were my first graders who figured that “what” must begin with the /d/ sound (using the name of the letter “w” as a clue to its sound, an approach that works often but not always).

Nevertheless, newer and more relevant research has shown that letter names may play an important role in early literacy learning. Those confusions do occur, but more often the letter names facilitate the learning of letter sounds – because the names and sounds are usually in better agreement than in the confusing instances (Treiman, et al., 2008; Venezky, 1975) and letter names seem to be more effective than sounds in supporting learning early in the progression (Share, 2004; Treiman, 2001). One instructional study with preschoolers found that teaching letter names together with letter sounds led to improved letter sound learning when compared to just teaching the sounds alone (Piasta, Purpura, & Wagner, 2010) – and this benefit was clearly due to the combination and not to any differences in print exposure, instructional time or intensity. Another study (Kim, Petscher, Foorman, & Zhou, 2010) found that letter name knowledge had a larger impact on letter-sound acquisition than the reverse, and that phonological awareness had a larger impact on letter sound learning when letter names were already known.

Another study (Kim, Petscher, Foorman, & Zhou, 2010) found that letter name knowledge had a larger impact on letter-sound acquisition than the reverse, and that phonological awareness had a larger impact on letter sound learning when letter names were already known.

That learning advantage may be something specifically American, however. In the U.S., children tend to learn letter names quite early – look at the number of toys that emphasize this knowledge (type “letter name toys for infants” into Google and you get more than 8 million hits) or the Head Start curriculum. Old fashioned toys like wooden blocks emphasize letter naming, as do the latest technological gadgets. That means that many kids start school knowing at least some of the letter names and that knowledge may be the reason why letters do more to help sound learning, rather than the opposite.

One cool natural experiment compared children in the U.S. with those in England, where letter names are introduced later than letter sounds. There, the kids use their knowledge of sounds to help in the mastery of the letter names (Ellefson, Treiman, & Kessler, 2009). Essentially, the researchers figured that learning that first list of letters or sounds is just arbitrary memorization. Then, when the kids try to learn the second list, they use what they already know to make the task go easier. If I know my letter names, and they give me a clue that will help me learn the sounds, then I do that. On the other hand, if I already have mastered the sounds, then they may be used to facilitate my learning of the letter names.

There, the kids use their knowledge of sounds to help in the mastery of the letter names (Ellefson, Treiman, & Kessler, 2009). Essentially, the researchers figured that learning that first list of letters or sounds is just arbitrary memorization. Then, when the kids try to learn the second list, they use what they already know to make the task go easier. If I know my letter names, and they give me a clue that will help me learn the sounds, then I do that. On the other hand, if I already have mastered the sounds, then they may be used to facilitate my learning of the letter names.

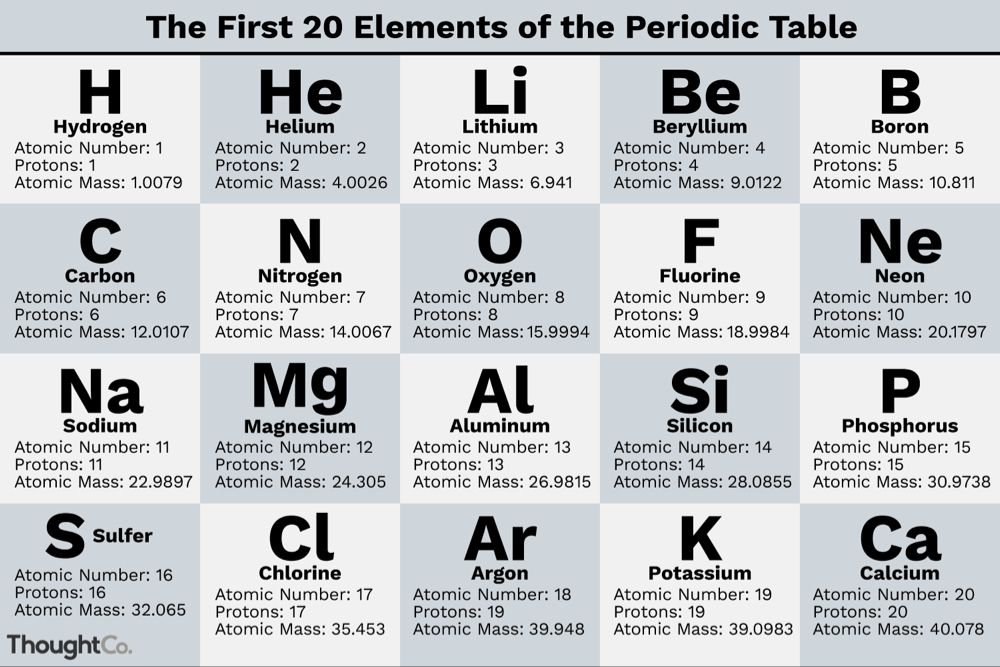

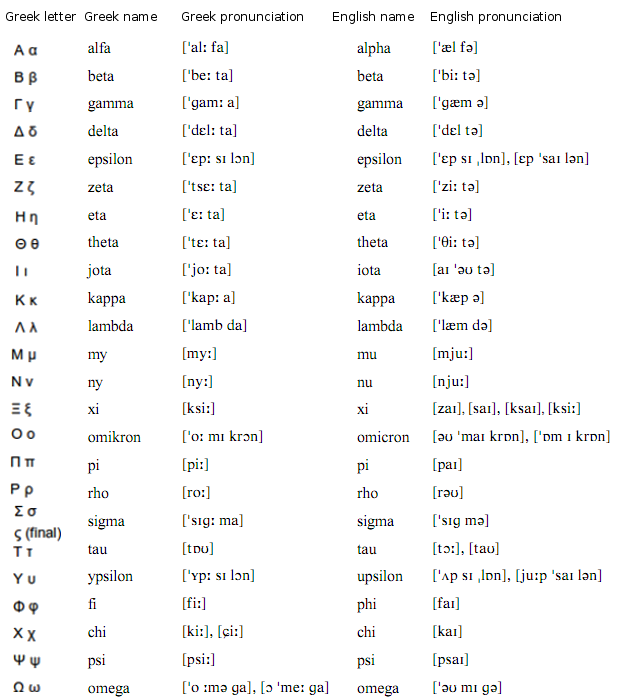

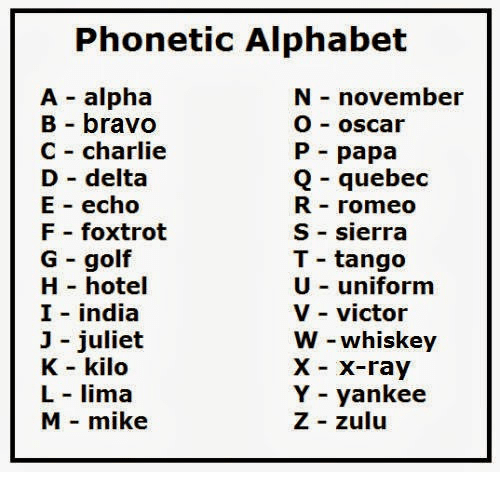

If English was more like Finnish, with everyone pronouncing the language pretty consistently, and a written symbol for every phoneme in the language, I would conclude from all of this that we only need to teach letter sounds. English is more complicated than that both in terms of the range of dialects and the conditionality of the spellings – particular sounds are often represented by multiple letters (think of the letter “s” in sick, sure, ship, and use). Having a name for the letter separate from the mélange of sounds that it will represent is helpful – it provides some stability to work with. Even in England, by the time kids are taking on English spelling in its full complexity, letter names will usually have been learned. (It should also be pointed out that consistent letter names also provide a useful consistent anchor for the visual forms of the letters as well:

Having a name for the letter separate from the mélange of sounds that it will represent is helpful – it provides some stability to work with. Even in England, by the time kids are taking on English spelling in its full complexity, letter names will usually have been learned. (It should also be pointed out that consistent letter names also provide a useful consistent anchor for the visual forms of the letters as well:

In the U.S., given that many children come to school knowing at least some letter names, it makes the greatest sense to start right there. The studies show that letters are a better base for sound learning in American schools, but they don’t reveal whether this sequence is superior to a combined approach, teaching letters and sounds simultaneously. None of the studies compared this.

My sense of this as a teacher? If kids come to school knowing a bunch of letter names – at whatever age, I would turn my focus to the letter sounds – that available letter name knowledge will be a boon. On the other hand, if they know few letters when we start, I might vary my approach a bit… with the preschoolers I’d focus more on the letter names for a while, and not sweat the sounds. While in kindergarten and grade 1, I’d try to teach names and sounds together. I think there’d be less chance that I’d confuse those kids with a combined approach – their attention spans are a bit longer. I expect that I’ll hear from preschool teachers telling of their success in teaching letters and sounds in combination, and K-1 teachers of their one skill at a time triumphs… but that just means it probably won’t matter much, one way or the other, if you can make your approach work efficiently.

On the other hand, if they know few letters when we start, I might vary my approach a bit… with the preschoolers I’d focus more on the letter names for a while, and not sweat the sounds. While in kindergarten and grade 1, I’d try to teach names and sounds together. I think there’d be less chance that I’d confuse those kids with a combined approach – their attention spans are a bit longer. I expect that I’ll hear from preschool teachers telling of their success in teaching letters and sounds in combination, and K-1 teachers of their one skill at a time triumphs… but that just means it probably won’t matter much, one way or the other, if you can make your approach work efficiently.

I definitely wouldn’t start with the sounds first, though that doesn’t seem to be a problem in the U.K. I think of the unifying value of letter names as being foundational knowledge, so I feel more comfortable starting there. That approach, however, is an opinion rather than a data-based, science of reading claim. That opinion is drawn from my experiences in teaching children and in my estimation of my own pedagogical skills (those with greater skills may be able to succeed with less likely bets).

That opinion is drawn from my experiences in teaching children and in my estimation of my own pedagogical skills (those with greater skills may be able to succeed with less likely bets).

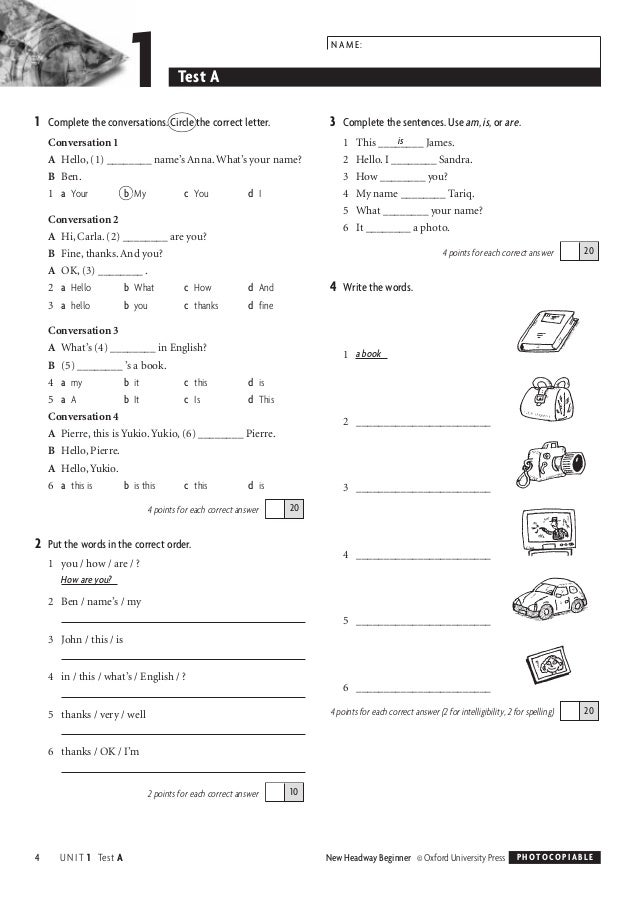

Finally, I’d add something you didn’t ask about. When teaching the letter names or sounds I’d teach students to print the letters. There is no reason to leave printing out of this equation – this added demand requires students to look at the letters more thoroughly, gaining purchase on their distinguishing features and it may increase the chances of the letters and sounds ending up in long term memory. Kids are hands on… they like to stack blocks, fingerpaint, decorate Christmas cookies, sit in water (don’t ask), and put their hands in stuff I don’t even want to think about… they like to mark on paper too, and getting them physically involved in literacy is not a bad thing. Letters then sounds, or letters and sounds together, but writing included with either approach. To me, that’s the winning hand.

References

Ellefson, M. R., Treiman, R., & Kessler, B. (2009). Learning to label letters by sounds or names: A comparison of england and the united states. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 102(3), 323-341. doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxy.cc.uic.edu/10.1016/j.jecp.2008.05.008

Piasta, S. B., Purpura, D. J., & Wagner, R. K. (2010). Fostering alphabet knowledge development: A comparison of two instructional approaches. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 23(6), 607-626. doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxy.cc.uic.edu/10.1007/s11145-009-9174-x

Share, D. L. (2004). Knowing letter names and learning letter sounds: A causal connection. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 88(3), 213-233. doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxy.cc.uic.edu/10.1016/j.jecp.2004.03.005

Treiman, R., Pennington, B. F., Shriberg, L. D., & Boada, R. (2008). Which children benefit from letter names in learning letter sounds? Cognition, 106(3), 1322-1338. doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxy.cc.uic.edu/10.1016/j.cognition.2007.06.006

doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxy.cc.uic.edu/10.1016/j.cognition.2007.06.006

Treiman, R., Sotak, L., & Bowman, M. (2001). The roles of letter names and letter sounds in connecting print and speech. Memory & Cognition, 29(6), 860-873. doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxy.cc.uic.edu/10.3758/BF03196415

Venezky, R.L. (1975). The curious role of letter names in reading instruction. Visible Language, 9, 7-23.

Russian alphabet with numbering, letters in order

Russian alphabet: educational materials, tables, pictures. Letters: numbering, vowels and consonants, frequency.

- Russian alphabet. What is an alphabet?

- Letters of the alphabet

- One line

- How many letters are there in the alphabet?

- Vowels and consonants

- Uppercase and lowercase letters

- Symmetrical

- Letter numbers

- Letter frequency

- Spell frequency of words

- General table

The modern Russian alphabet consists of 33 letters. The alphabet in its current representation has existed since 1942. In fact, the year 1918 can be considered the year of the formation of the modern Russian alphabet - then it consisted of 32 letters (without the letter ё). The origin of the alphabet, according to historical documents, is associated with the names Cyril and Methodius and dates back to the 9th century AD. From the moment of its origin until 1918, the alphabet changed several times, incorporating and excluding signs. At one time it had over 40 letters. The Russian alphabet is also sometimes called the Russian alphabet.

The alphabet in its current representation has existed since 1942. In fact, the year 1918 can be considered the year of the formation of the modern Russian alphabet - then it consisted of 32 letters (without the letter ё). The origin of the alphabet, according to historical documents, is associated with the names Cyril and Methodius and dates back to the 9th century AD. From the moment of its origin until 1918, the alphabet changed several times, incorporating and excluding signs. At one time it had over 40 letters. The Russian alphabet is also sometimes called the Russian alphabet.

On our website for each letter of the Russian alphabet there is a separate page with a detailed description, examples of words, pictures, poems, riddles. They can be printed or downloaded. Click on the letter you want to go to its page.

100%

em N n en O o o P p p pe R r er S es T t te U u u F f ff X x ha Q t tse H h che Sh sh sch sch sha b b hard sign Y y y b b soft sign uh uh reverse yu yu yu i i i

Download and print the alphabet

Image: png, 906×1018 px, 92. 3 Kb

3 Kb

Print Download

some contexts require the use of the letter ё to avoid ambiguity. Russian letters are neuter nouns. It should be borne in mind that the style of the letters depends on the font. From the site you can download the alphabet or download the letters in pdf format (on each sheet by letter).

Letters of the Russian alphabet

Frequently asked questions about the letters of the Russian alphabet are: how many letters are there in the alphabet, which are vowels and consonants, which are called uppercase and which are lowercase? Basic information about letters is often found in popular questions for primary school students, in erudition and IQ tests, in questionnaires for foreigners on knowledge of the Russian language, and other similar tasks.

Single line

Capital letters

in order:

in order, separated by a space: A B C D E E F G I J K L M N O P R S T U V X T

in order with a comma: A, B, C, D, D, E, E, F, Z, I, Y, K, L, M, N, O, P, R, C, T, U, F, X, C, H, W, W, b, S, b, E, Yu, I;

in reverse order: YOYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYYY

Lowercase letters

, in order:

in order, separated by a space:

in order with a comma: a, b, c, d, e, e, e, f, h, i, d, k, l, m, n, o, p, p, s, t, y, f, x, c, h, w, u, b, s, b, e, u, i;

in reverse order:

Number of letters

How many letters are there in the Russian alphabet?

There are 33 letters in the Russian alphabet.

Some people, in order to memorize the number of letters in the Russian alphabet, associate them with popular phrases: "33 pleasures", "33 misfortunes", "33 cows". Other people associate with facts from their lives: I live in apartment number 33, I live in region 33 (Vladimir region), I play in team number 33 and the like. And if the number of letters of the alphabet is forgotten again, then the associated phrases help to remember it. Maybe it will help you too.

Vowels and consonants

How many vowels and consonants are there in the Russian alphabet?

10 vowels + 21 consonants + 2 do not mean a sound

Among the letters of the Russian alphabet, there are:

The letter means sound. Compare: “ka”, “el” are the names of letters, [k], [l] are sounds.

Uppercase and lowercase

Which letters are uppercase and which are lowercase?

Letters are uppercase (or capital) and lowercase:

- A, B, V .

.. E, Yu, Z - uppercase letters,

.. E, Yu, Z - uppercase letters, - a, b, c ... e, u, z - lowercase letters .

Sometimes they say: big and small letters. But this wording is incorrect, since it means the size of the letter, and not its style. Compare:

B is a large capital letter, B is a small capital letter, b is a large lowercase letter, b is a small lowercase letter.

Proper names are capitalized, the beginning of sentences, appeal to "you" with an expression of deep respect. In computer programs, the term "letter case" is used: upper case letters are typed in upper case, lower case letters are typed in lower case.

Symmetrical

In the Russian alphabet, 11 letters have vertical symmetry (with respect to the Y axis): A, D, Zh, M, N, O, P, T, F, X, Sh. The left part of the letters coincides with the right part. If the letters are rotated from right to left, then their style will not change.

7 letters have horizontal symmetry (with respect to the X axis): B, E, Z, K, C, E, Yu. The upper part of the letters coincides with the lower one. If the letters are turned upside down, then their outline will not change. Note that the lowercase e has no symmetry.

The upper part of the letters coincides with the lower one. If the letters are turned upside down, then their outline will not change. Note that the lowercase e has no symmetry.

Vertical and horizontal symmetry of 5 letters: Zh, N, O, F, X. These letters are called mirror. The letter And becomes symmetrical when simultaneously rotated along two axes.

- A

Y - B

- - C

X - D

- - D

Y - E

x -

- - F

XY - K

X - and

- -

- - K 9000 9000 L - 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000.

- N

XY - O

XY - P

Y - R

- - C

x - T

Y - in

- - XY

- - H

- - Sh

Y - SH

- - b

- - s

- - b

- - E

x -

- 9000

Y

x

Press the buttons to check the turn of the letters in the list above.

Numbering of letters

In some logical tasks to determine the next element in a series, in games when solving comic ciphers, in competitions for knowledge of the alphabet and in other similar cases, it is required to know the serial numbers of the letters of the Russian alphabet, including numbers when counting from the end to the beginning of the alphabet. Our visual "strip" will help you quickly determine the number of a letter in the alphabet.

- A

1

33 - B

2

32 - B

3

31 - G

4

- D

5

29 - 9000 E

6 9005 -

8

26 - С

9

25 - and

10

24 -

11

23,0006 - K

12

22 - L

13

9000 9000 9000 m 9005 - H

15

19 - O

16

18 - P

17

17 - R

18

16 - C

19

15,0005

20

14 - 9000

- x

23

11 - C

24

10 - h

25

9,0006 - Sh

26

8 - SH

27

7 -

28

6 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 b

30

4 - E

31

3 - Yu

32

2 - I

33

1

P - "middle" letter of the alphabet, 3rd - first vowel I position), B - the first consonant (2nd position), Щ - the last consonant (27th position) in the alphabet.

Letter frequency

There is a concept of letter frequency. Frequency shows how many times a letter is used in all words of the Russian language. The more often a letter is used in speech, the higher its frequency. In Russian, the letter O has the highest frequency, the letter Yo has the smallest. This means that there are many Russian words with the letter O and very few words with the letter Y.

In Russian:

letters O, E, A, I, N, T, C are often found;

letters Ё, Ъ, F, E, Shch, C, Yu, Sh, Zh, X are rare;

common vowels: O, E, A, I;

common consonants: H, T, C, R, V, L;

rare vowels: Yo, Yu;

rare consonants: Ф, Ш, Ц, Ш, Ж, Х.

The word “often” means a frequency above 4%, the word “rarely” means a frequency less than 1%.

The frequency of a letter is determined by the ratio of the use of the letter itself in speech to the number of uses of all letters in the Russian language. To calculate the frequency, the formula was used:

F letter = Q letter Q all ,

Materials of the National Corpus of the Russian Language were used to analyze the frequency of letters. The corpus contains information about the use of each letter of the alphabet in speech and the total number of letters used in all words of the Russian language, which is 505 266 851. Thus, the formula for calculating the frequency of a letter is reduced to the form F = Q letter 505 266 851.

The corpus contains information about the use of each letter of the alphabet in speech and the total number of letters used in all words of the Russian language, which is 505 266 851. Thus, the formula for calculating the frequency of a letter is reduced to the form F = Q letter 505 266 851.

Below the letters of the Russian alphabet, indicating the frequency in percent.

- A

8.01% - B

1.59% - B

4.54% - G

1.70% - D

9000 - Z

1.65% - I

7.35% - Y

1.21% - K

3.49% - L

4.40% - M0006

- H

6.70% - O

10.97% - P

2.81% - R

4.73% - C

5.47% - 9000 X

0.97% - C

0.48% 9000. 0.32% - Yu

0.64% - I

2.01%

Each letter of the alphabet has its own rank - a position depending on the frequency indicator. Since the letter O has the highest frequency, its rank is 1, the letter E has the smallest frequency, rank 33.

Since the letter O has the highest frequency, its rank is 1, the letter E has the smallest frequency, rank 33.

- O

1 - E

2 - A

3 - and

4 9000 H - T

6 - C

7 - R

8 - V

9 - L

10 - to

11 - m

12 - D

13 - P

14 - U

15 - I

16 - 9,0006

- B

18 -

199000 9000 9000 9 ° 9005 20000 20000 20000 20000 20000 - b

21 - h

22 -

23 - x

24 -

25 - Sh

26 -

27 9000 - F

31 - Ъ

32 - Ё

33

5

Spell frequency of words

In linguistics, there is the concept of word frequency, which determines the ratio of the number of word usages of a word to the total number of word usages in speech. Within the framework of our project, the frequency of words by letters is understood as the ratio of words beginning with the corresponding letter to the total number of words in the Russian language. The counting formula is similar to the formula for the frequency of letters:

The counting formula is similar to the formula for the frequency of letters:

F word-letter = Q word-letter Q all words ,

words.

Let's show the indicators calculated by us as a percentage for each letter. To analyze the frequency of words, the dictionary of N. Tikhonov was taken.

- A

3.26% - B

3.83% - C

6.36% - D

3.20% - D

4.20% - E

0.28% -

0.02% - F

0.64% - ° C

4.36% - and

2.69% -

% 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000. - m

4.52% - N

6.09% - 7.16%

- P

17.28% -

4.93% - 8.9000% 9000,000

- T 9005 3.62% 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 943 2 %

- F

1.65% - x

1.20% - C

0.62% - h

1. 02%

02% - Sh

1.28% - 0.16%

- KO

0.00% - 0.00%

- 9000

1.40% - S

0.15% - R

0.31%

2.16%

Words beginning with Y are names of geographical features.

In Russian:

most words starting with the letter P,

most words starting with the letter O among vowels,

few words starting with the letters Yo, Y, Yu,

the fewest words starting with the letter Y,

among consonants the least words starting with the letter Y,

no words on the letters b, b.

Taking into account the calculated indicators, the rank of a letter is easily determined by the number of words beginning with a letter.

- R

1 - C

2 - O

3 - B

4 - C

5 - H 6

6

- R

7 - m

8 - С

- D

10 - B

11 - T

12 - A

13 - G 9005

- l

17 - 18

- E

19 - Sh

20,0006 - x

21 9000. -

23 - 9005 24 9000 9000

- Sh.

27 - U

28 - I

29 -

30 - 31

-

32 - B

32

22

Summarizing table

9000 direct and reverse numbering, spelling, name, sound (transcription), absolute value of frequency, percentage value of frequency and rank of frequency.

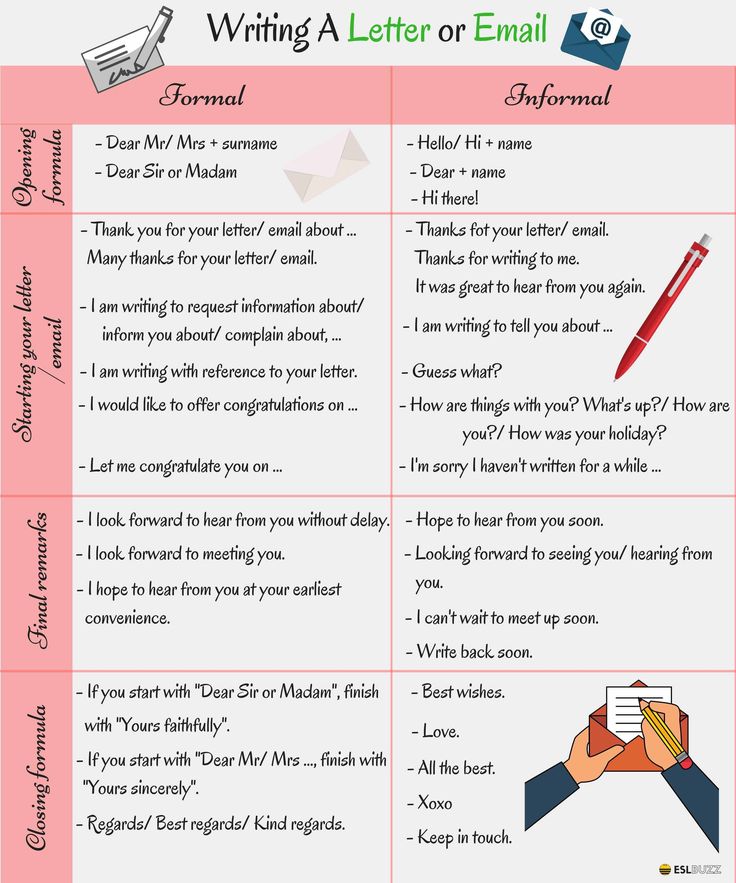

. What are the names of the letters of the Russian alphabet?

. What are the names of the letters of the Russian alphabet?  ) that begin with the corresponding sound, like the letters of the Greek alphabet. At the beginning of the 20th century, this principle of naming letters was completely supplanted by the principle of naming by the designated sound (a, be, ve), like the Latin alphabet. The advantage of the second principle is the convenience of learning to read. According to the first principle they taught, for example:

) that begin with the corresponding sound, like the letters of the Greek alphabet. At the beginning of the 20th century, this principle of naming letters was completely supplanted by the principle of naming by the designated sound (a, be, ve), like the Latin alphabet. The advantage of the second principle is the convenience of learning to read. According to the first principle they taught, for example:  .. ”(Talking about the orthography of Mr. Trediakovsky, 1748; University Church and Civil Alphabet with brief notes on spelling, 1768).

.. ”(Talking about the orthography of Mr. Trediakovsky, 1748; University Church and Civil Alphabet with brief notes on spelling, 1768).

"

"

F. Modern Russian language. Graphics and spelling. - 2nd ed. - M .: Education, 1976. - 288 p.

F. Modern Russian language. Graphics and spelling. - 2nd ed. - M .: Education, 1976. - 288 p.