What are the strategies for reading

Strategies for Reading Comprehension :: Read Naturally, Inc.

Comprehension: The Goal of Reading

Comprehension, or extracting meaning from what you read, is the ultimate goal of reading. Experienced readers take this for granted and may not appreciate the reading comprehension skills required. The process of comprehension is both interactive and strategic. Rather than passively reading text, readers must analyze it, internalize it and make it their own.

In order to read with comprehension, developing readers must be able to read with some proficiency and then receive explicit instruction in reading comprehension strategies (Tierney, 1982).

Strategies for reading comprehension in Read Naturally programs

General Strategies for Reading Comprehension

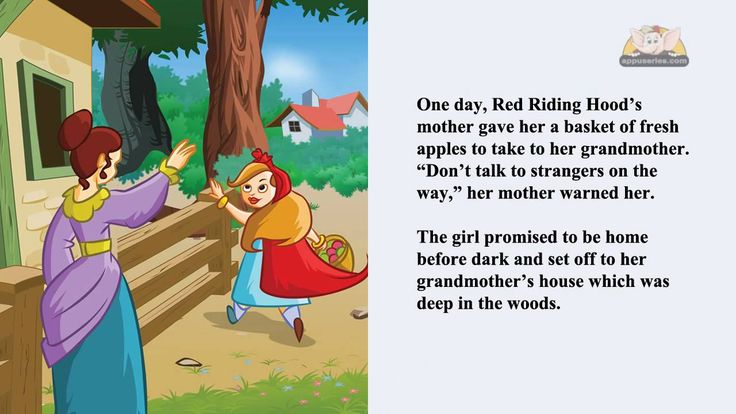

The process of comprehending text begins before children can read, when someone reads a picture book to them. They listen to the words, see the pictures in the book, and may start to associate the words on the page with the words they are hearing and the ideas they represent.

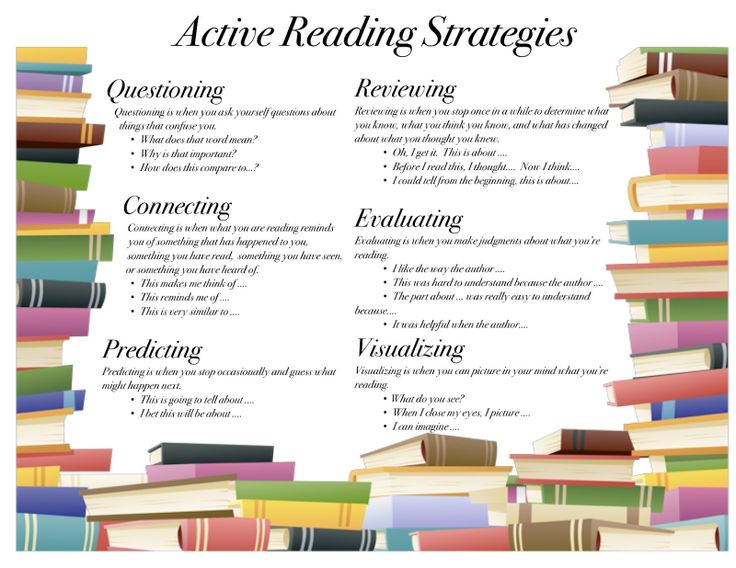

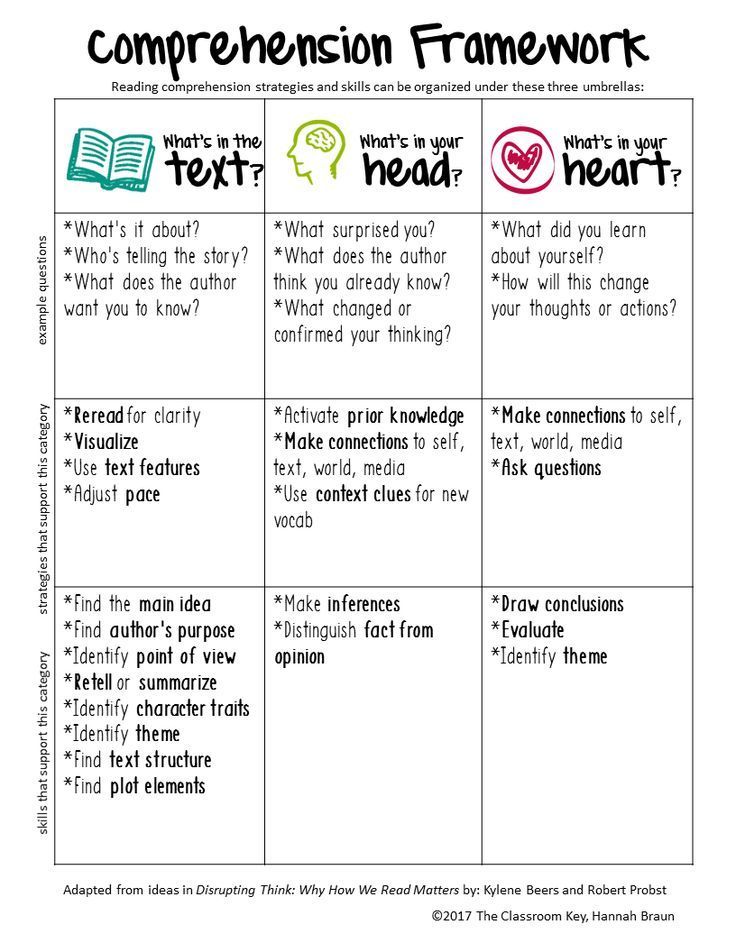

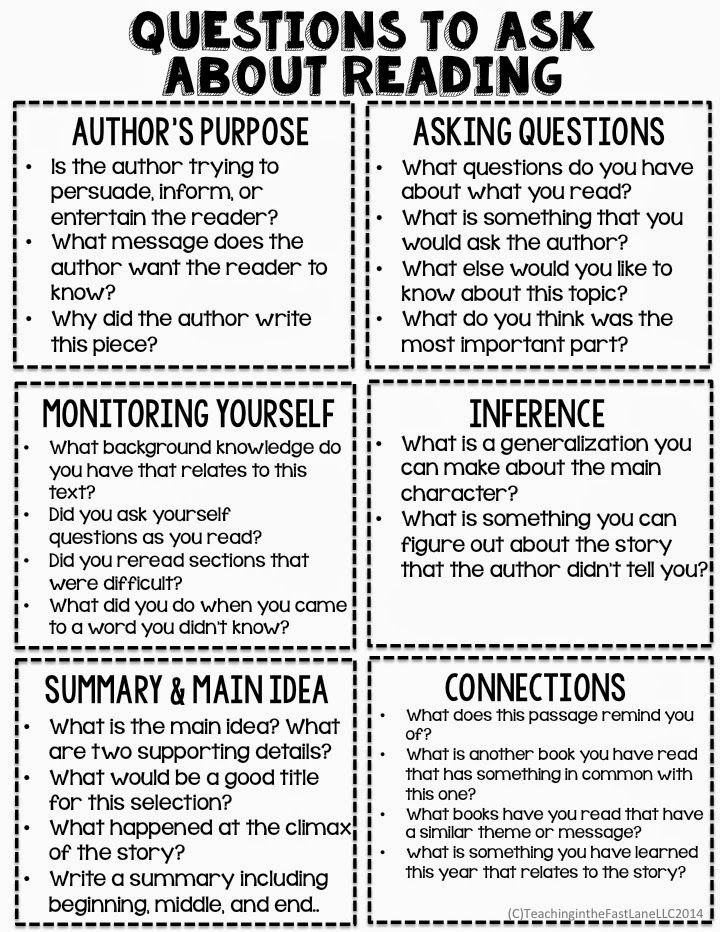

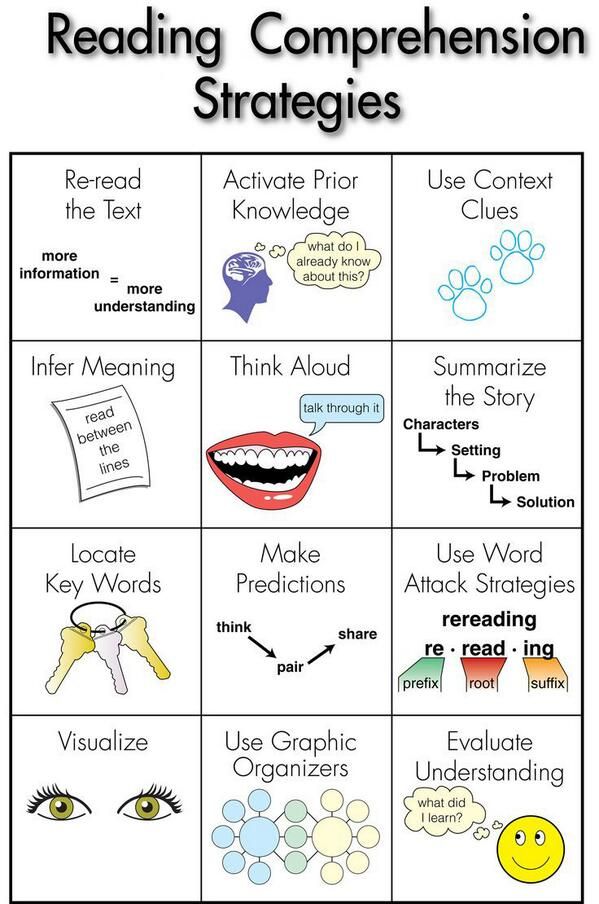

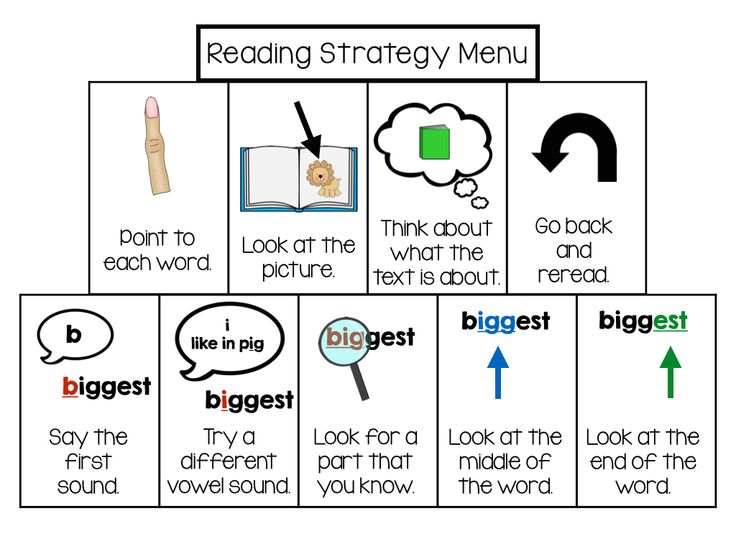

In order to learn comprehension strategies, students need modeling, practice, and feedback. The key comprehension strategies are described below.

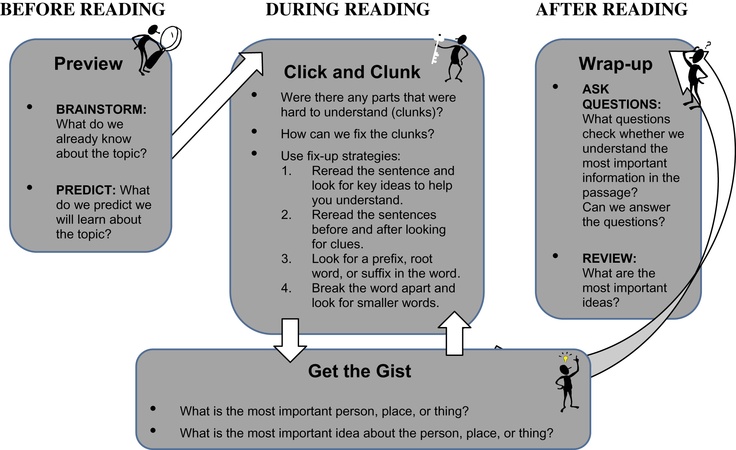

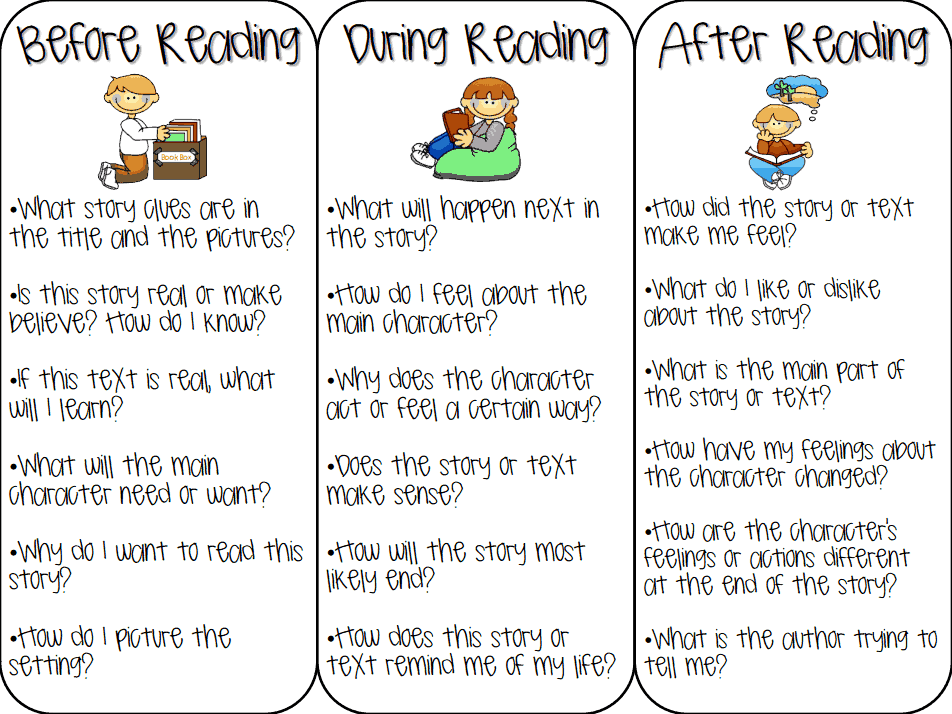

Using Prior Knowledge/Previewing

When students preview text, they tap into what they already know that will help them to understand the text they are about to read. This provides a framework for any new information they read.

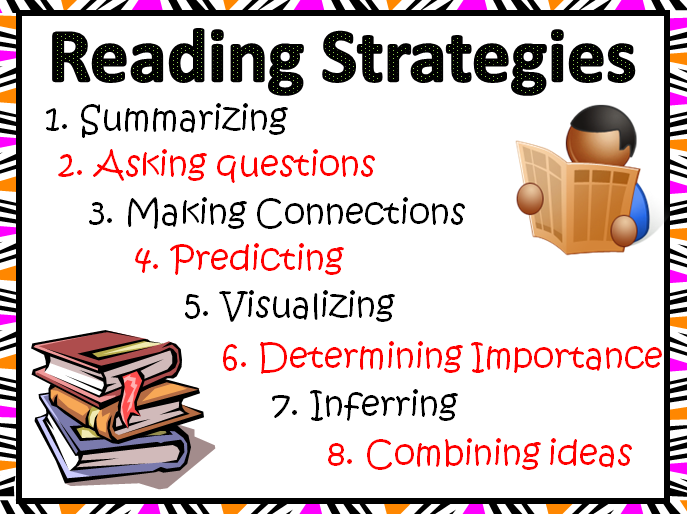

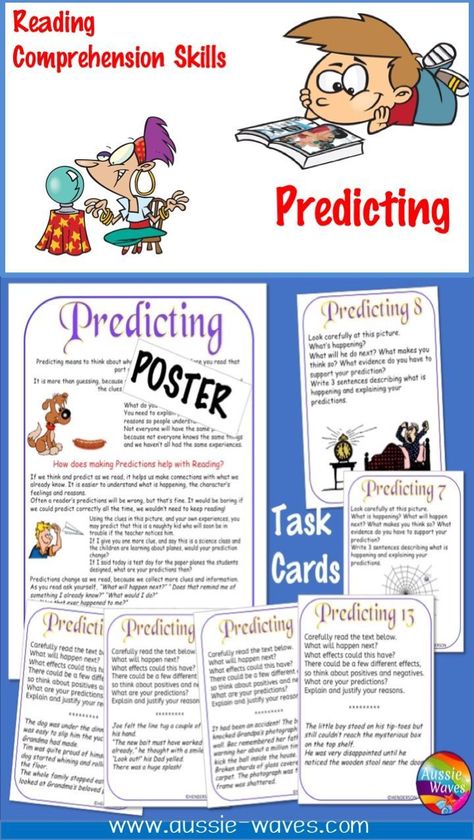

Predicting

When students make predictions about the text they are about to read, it sets up expectations based on their prior knowledge about similar topics. As they read, they may mentally revise their prediction as they gain more information.

Identifying the Main Idea and Summarization

Identifying the main idea and summarizing requires that students determine what is important and then put it in their own words. Implicit in this process is trying to understand the author’s purpose in writing the text.

Questioning

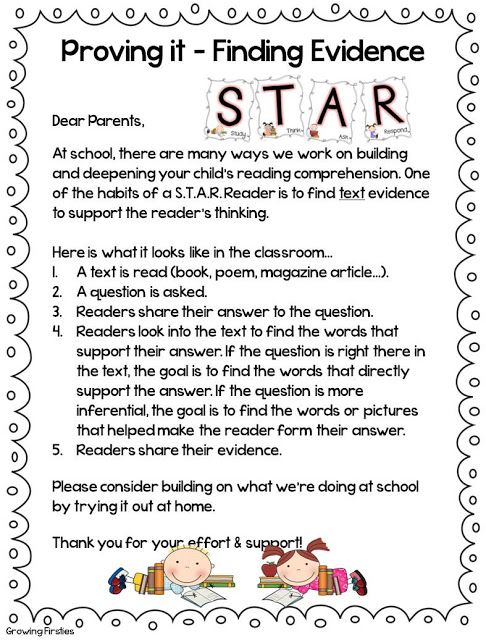

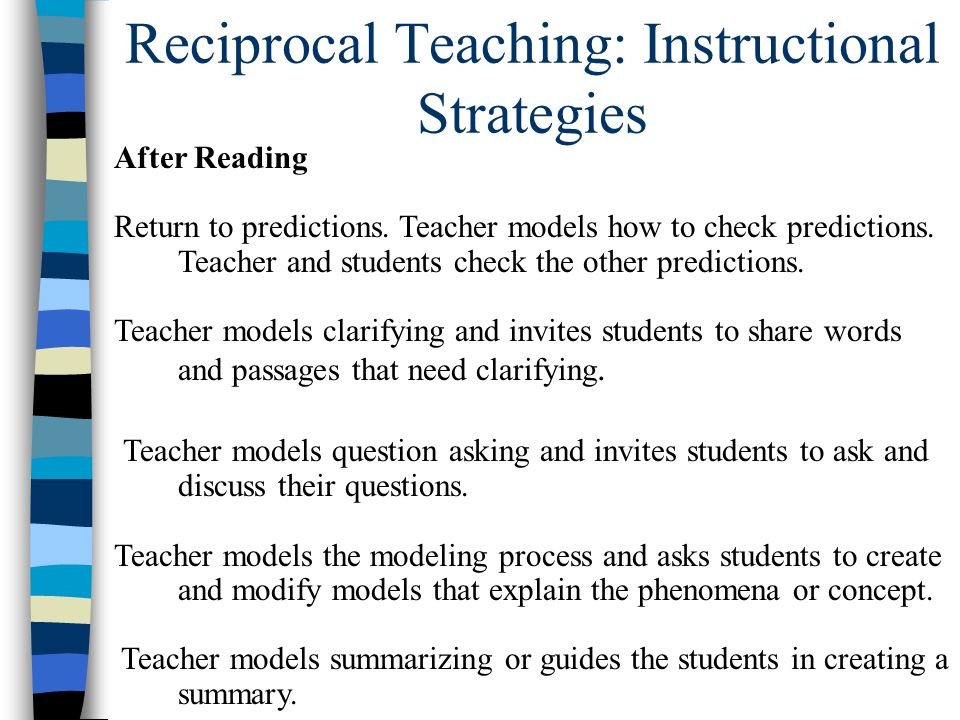

Asking and answering questions about text is another strategy that helps students focus on the meaning of text. Teachers can help by modeling both the process of asking good questions and strategies for finding the answers in the text.

Teachers can help by modeling both the process of asking good questions and strategies for finding the answers in the text.

Making Inferences

In order to make inferences about something that is not explicitly stated in the text, students must learn to draw on prior knowledge and recognize clues in the text itself.

Visualizing

Studies have shown that students who visualize while reading have better recall than those who do not (Pressley, 1977). Readers can take advantage of illustrations that are embedded in the text or create their own mental images or drawings when reading text without illustrations.

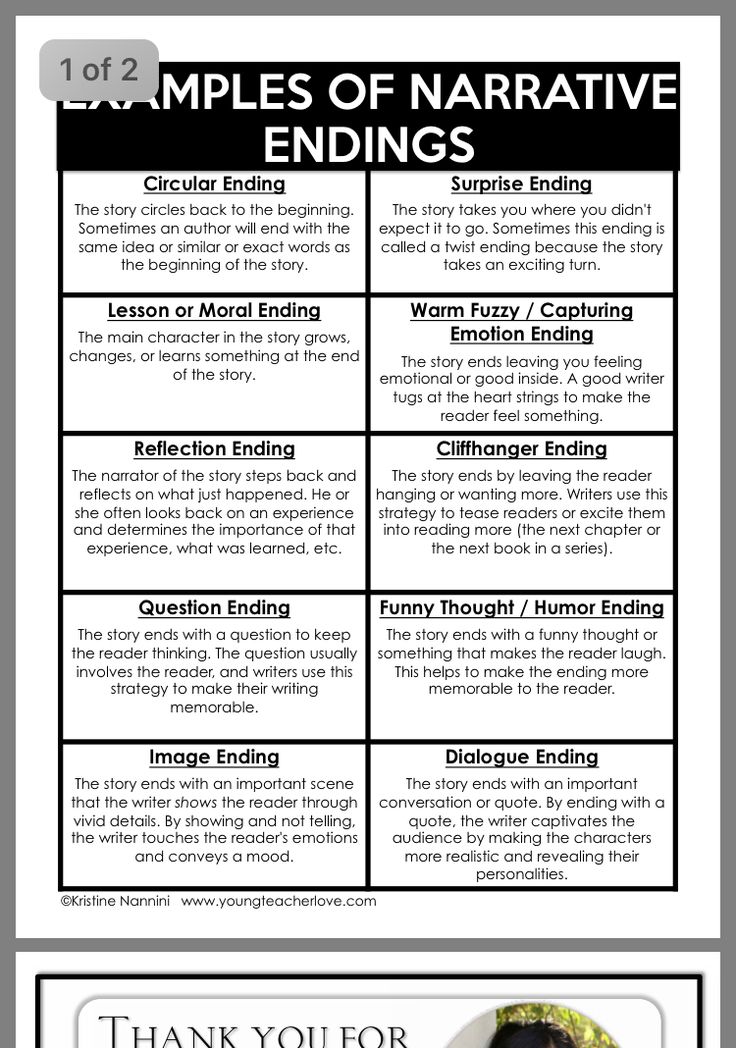

Strategies for Reading Comprehension: Narrative Text

Narrative text tells a story, either a true story or a fictional story. There are a number of strategies that will help students understand narrative text.

Story Maps

Teachers can have students diagram the story grammar of the text to raise their awareness of the elements the author uses to construct the story. Story grammar includes:

Story grammar includes:

- Setting: When and where the story takes place (which can change over the course of the story).

- Characters: The people or animals in the story, including the protagonist (main character), whose motivations and actions drive the story.

- Plot: The story line, which typically includes one or more problems or conflicts that the protagonist must address and ultimately resolve.

- Theme: The overriding lesson or main idea that the author wants readers to glean from the story. It could be explicitly stated as in Aesop’s Fables or inferred by the reader (more common).

Printable story map (blank)

Retelling

Asking students to retell a story in their own words forces them to analyze the content to determine what is important. Teachers can encourage students to go beyond literally recounting the story to drawing their own conclusions about it.

Prediction

Teachers can ask readers to make a prediction about a story based on the title and any other clues that are available, such as illustrations. Teachers can later ask students to find text that supports or contradicts their predictions.

Teachers can later ask students to find text that supports or contradicts their predictions.

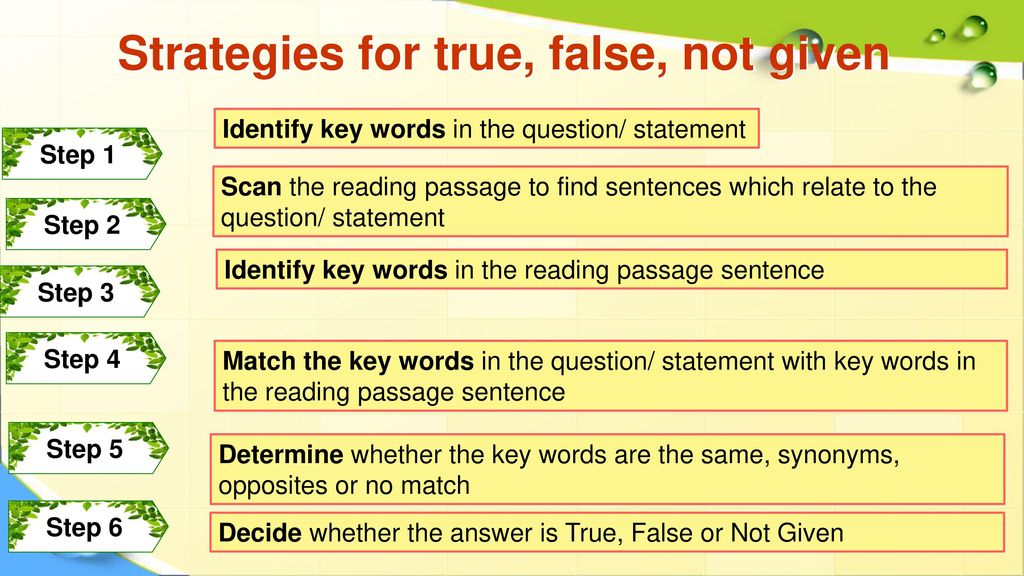

Answering Comprehension Questions

Asking students different types of questions requires that they find the answers in different ways, for example, by finding literal answers in the text itself or by drawing on prior knowledge and then inferring answers based on clues in the text.

Strategies for Reading Comprehension: Expository Text

Expository text explains facts and concepts in order to inform, persuade, or explain.

The Structure of Expository Text

Expository text is typically structured with visual cues such as headings and subheadings that provide clear cues as to the structure of the information. The first sentence in a paragraph is also typically a topic sentence that clearly states what the paragraph is about.

Expository text also often uses one of five common text structures as an organizing principle:

- Cause and effect

- Problem and solution

- Compare and contrast

- Description

- Time order (sequence of events, actions, or steps)

Teaching these structures can help students recognize relationships between ideas and the overall intent of the text.

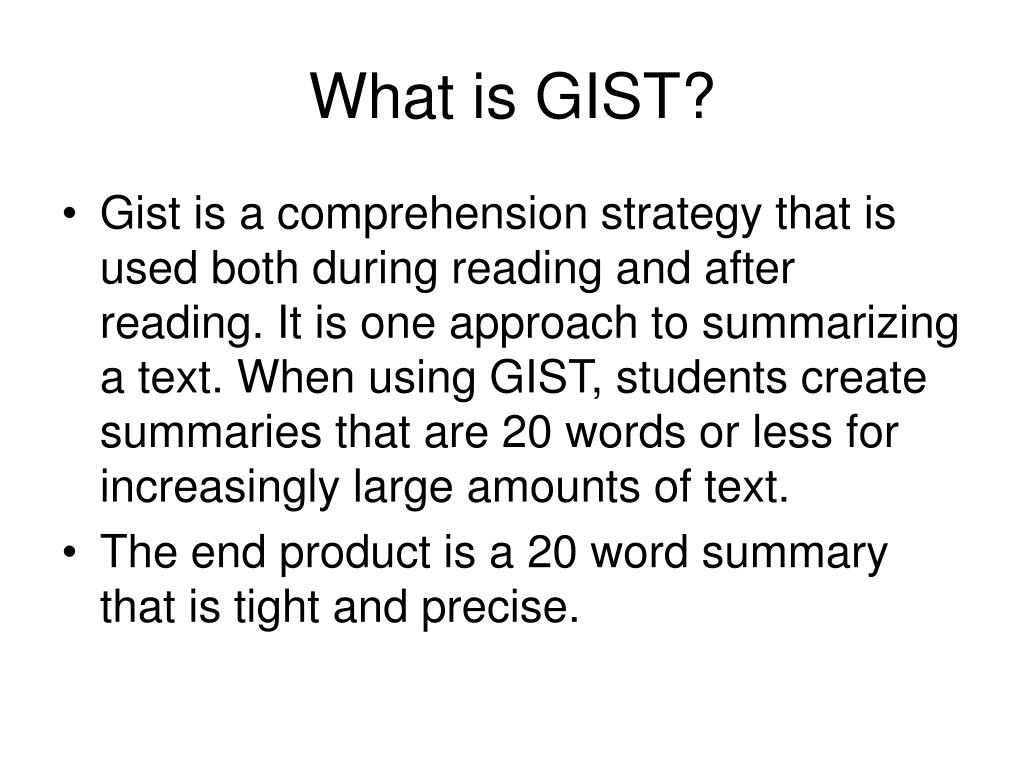

Main Idea/Summarization

A summary briefly captures the main idea of the text and the key details that support the main idea. Students must understand the text in order to write a good summary that is more than a repetition of the text itself.

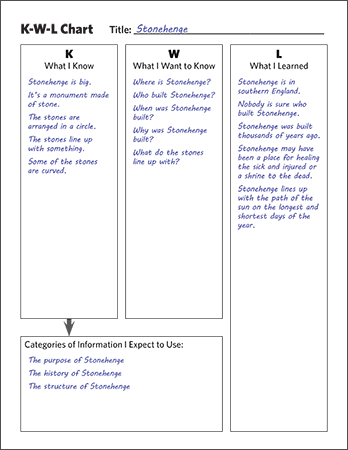

K-W-L

There are three steps in the K-W-L process (Ogle, 1986):

- What I Know: Before students read the text, ask them as a group to identify what they already know about the topic. Students write this list in the “K” column of their K-W-L forms.

- What I Want to Know: Ask students to write questions about what they want to learn from reading the text in the “W” column of their K-W-L forms. For example, students may wonder if some of the “facts” offered in the “K” column are true.

- What I Learned: As they read the text, students should look for answers to the questions listed in the “W” column and write their answers in the “L” column along with anything else they learn.

After all of the students have read the text, the teacher leads a discussion of the questions and answers.

Printable K-W-L chart (blank)

Graphic Organizers

Graphic organizers provide visual representations of the concepts in expository text. Representing ideas and relationships graphically can help students understand and remember them. Examples of graphic organizers are:

Tree diagrams that represent categories and hierarchies

Tables that compare and contrast data

Time-driven diagrams that represent the order of events

Flowcharts that represent the steps of a process

Teaching students how to develop and construct graphic organizers will require some modeling, guidance, and feedback. Teachers should demonstrate the process with examples first before students practice doing it on their own with teacher guidance and eventually work independently.

Strategies for Reading Comprehension in Read Naturally Programs

Several Read Naturally programs include strategies that support comprehension:

| Read Naturally Intervention Program | Strategies for Reading Comprehension | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prediction Step | Retelling Step | Quiz / Comprehension Questions | Graphic Organizers | |

| Read Naturally Live:

| ✔ | ✔ |

| |

| Read Naturally Encore:

| ✔ | ✔ |

| |

| Read Naturally GATE:

| ✔ | ✔ |

| |

| One Minute Reader Live:

|

| |||

| One Minute Reader Books/CDs:

|

| |||

| Take Aim at Vocabulary: A print-based program with audio CDs that teaches carefully selected target words and strategies for independently learning unknown words. Students work mostly independently or in teacher-led small groups of up to six students.

|

| ✔ | ||

Bibliography

Honig, B. , L. Diamond, and L. Gutlohn. (2013). Teaching reading sourcebook, 2nd ed. Novato, CA: Arena Press.

, L. Diamond, and L. Gutlohn. (2013). Teaching reading sourcebook, 2nd ed. Novato, CA: Arena Press.

Ogle, D. M. (1986). K-W-L: A teaching model that develops active reading of expository text. The Reading Teacher 38(6), pp. 564–570.

Pressley, M. (1977). Imagery and children’s learning: Putting the picture in developmental perspective. Review of Educational Research 47, pp. 586–622.

Tierney, R. J. (1982). Essential considerations for developing basic reading comprehension skills. School Psychology Review 11(3), pp. 299–305.

Teach the Seven Strategies of Highly Effective Readers

To assume that one can simply have students memorize and routinely execute a set of strategies is to misconceive the nature of strategic processing or executive control. Such rote applications of these procedures represents, in essence, a true oxymoron-non-strategic strategic processing.

— Alexander and Murphy (1998, p.

33)

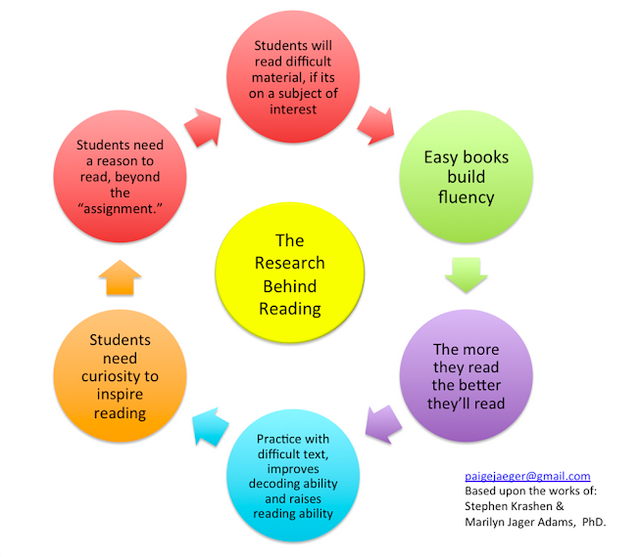

If the struggling readers in your content classroom routinely miss the point when “reading” content text, consider teaching them one or more of the seven cognitive strategies of highly effective readers. Cognitive strategies are the mental processes used by skilled readers to extract and construct meaning from text and to create knowledge structures in long-term memory. When these strategies are directly taught to and modeled for struggling readers, their comprehension and retention improve.

Struggling students often mistakenly believe they are reading when they are actually engaged in what researchers call mindless reading (Schooler, Reichle, & Halpern, 2004), zoning out while staring at the printed page. The opposite of mindless reading is the processing of text by highly effective readers using cognitive strategies. These strategies are described in a fascinating qualitative study that asked expert readers to think aloud regarding what was happening in their minds while they were reading. The lengthy scripts recording these spoken thoughts (i.e., think-alouds) are called verbal protocols (Pressley & Afflerbach, 1995). These protocols were categorized and analyzed by researchers to answer specific questions, such as, What is the influence of prior knowledge on expert readers’ strategies as they determine the main idea of a text? (Afflerbach, 1990b).

The lengthy scripts recording these spoken thoughts (i.e., think-alouds) are called verbal protocols (Pressley & Afflerbach, 1995). These protocols were categorized and analyzed by researchers to answer specific questions, such as, What is the influence of prior knowledge on expert readers’ strategies as they determine the main idea of a text? (Afflerbach, 1990b).

The protocols provide accurate “snapshots” and even “videos” of the ever-changing mental landscape that expert readers construct during reading. Researchers have concluded that reading is “constructively responsive-that is, good readers are always changing their processing in response to the text they are reading” (Pressley & Afflerbach, 1995, p. 2). Instructional Aid 1.1 defines the seven cognitive strategies of highly effective readers, and Instructional Aid 1.2 provides a lesson plan template for teaching a cognitive strategy.

Instructional Aid 1.1: Seven Strategies of Highly Effective Readers | |

|---|---|

| Strategy | Definition |

| Activating | “Priming the cognitive pump” in order to recall relevent prior knowledge and experiences from long-term memory in order to extract and construct meaning from text |

| Inferring | Bringing together what is spoken (written) in the text, what is unspoken (unwritten) in the text, and what is already known by the reader in order to extract and construct meaning from the text |

| Monitoring-Clarifying | Thinking about how and what one is reading, both during and after the act of reading, for purposes of determining if one is comprehending the text combined with the ability to clarify and fix up any mix-ups |

| Questioning | Engaging in learning dialogues with text (authors), peers, and teachers through self-questioning, question generation, and question answering |

| Searching-Selecting | Searching a variety of sources in order to select appropriate information to answer questions, define words and terms, clarify misunderstandings, solve problems, or gather information |

| Summarizing | Restating the meaning of text in one’s own words — different words from those used in the original text |

| Visualizing-Organizing | Constructing a mental image or graphic organizer for the purpose of extracting and constructing meaning from the text |

| Download chart » (8K PDF)* |

Instructional Aid 1. 2: A Lesson Template for Teaching Cognitive Strategies 2: A Lesson Template for Teaching Cognitive Strategies | |

|---|---|

| Steps | Teacher Script |

| 1. Provide direct instruction regarding the cognitive strategy | |

| a. Define and explain the strategy | |

| b. Explain the purpose the strategy serves during reading | |

| c. Describe the critical attributes of the strategy | |

| d. Provide concrete examples/nonexamples of the strategy | |

| 2. Model the strategy by thinking aloud | |

| 3. Facilitate guided practice with students | |

| Download chart » (8K PDF)* |

Instructional Aid 1.3: A Lesson Template for Teaching Summarizing | |

|---|---|

| Lesson Template for Teaching Cognitive Strategies | Lesson Plan for Teaching Summarizing |

1. Provide direct instruction regarding the cognitive strategy Provide direct instruction regarding the cognitive strategy | |

| a. Define and explain the strategy. | Summarizing is restating in your own words the meaning of what you have read—using different words from those used in the original text—either in written form or a graphic representation (picture of graphic organizer). |

| b. Explain the purpose the strategy serves during reading | Summarizing enables a reader to determine what is most imporant to remember once the reading is completed. Many things we read have only one or two bid ideas, and it’s important to identify them and restate them for purposed of retention. |

| c. Describe the critical attributes of the strategy. | A summary has the following characteristics. It: –Is short –Is to the point, containing the big idea of the text –Omits trivial information and collapses lists into a word or phrase –Is not a retelling or a “photocopy” of the text |

d. Provide concrete examples/nonexamples of the strategy. Provide concrete examples/nonexamples of the strategy. | Examples of good summaries might inlude the one-sentence book summaries from The New York Times Bestsellers List, an obituary of a famous person, or a report of a basketball or football game that captures the highlights. The mistakes that students commonly make when writing summaries can be more readily avoided by showing students excellent nonexamples (e.g., a paragraph that is too long, has far too many details, or is a complete retelling of the text rather than a statement of the main idea. |

| 2. Model the strategy by thinking aloud. | Thinking aloud is a metacognitive activity in which teachers reflect on their behaviors, thoughts, and attitudes regarding what they have read and then speak their thoughts aloud for students. Choose a section of relatively easy text from your discipline and think aloud as you read it, and then also think aloud about how you would go about summarizing it — then do it. |

| 3. Facilitate guided practice with students. | Using easy-to-read content text, read aloud and generate a summary together with the whole class. Using easy-to-read content text, ask students to read with partners and create a summary together. One students are writing good summaries as partners, assign text and expect students to read it and generate summaries independently. |

| Download chart » (9K PDF)* |

McEwan, 2004. 7 Strategies of Highly Effective Readers: Using Cognitive Research to Boost K-8 Achievement. Wood, Woloshyn, & Willoughby, 1995. Cognitive Strategy Instruction for Middle and High Schools.

McEwan, E.K., 40 Ways to Support Struggling Readers in Content Classrooms. Grades 6-12, pp.1-6, copyright 2007 by Corwin Press. Reprinted by permission of Corwin Press, Inc.

How to Master Critical Thinking with a Reading Strategy

Whether you're a writer, a business executive, or in some area of self-improvement, you're no doubt inundated with text: news articles on your phone, school textbooks, hundreds of pages of a business report. You scroll through one report after another until they all merge into an amorphous mass. But what if, simply by organizing your reading process, you could easily understand everything you read with a little extra effort? nine0003

You scroll through one report after another until they all merge into an amorphous mass. But what if, simply by organizing your reading process, you could easily understand everything you read with a little extra effort? nine0003

Reading improvement is a key skill that enables you to think critically and clearly on any subject. And critical thinking on any subject will give you influence.

In How to Write Well, William Zinsser says, "Clear thinking becomes clear storytelling, one cannot exist without the other." To think clearly, you need to be a strong reader. A critical reading strategy can take your critical thinking to the next level and help you reach your goals. Clear thinking + critical thinking = powerful clear writing. nine0003

Since 1986, when I began teaching composition and English in college, I have introduced thousands of students to the SQ3R critical reading method: survey (evaluate), question (ask questions), read (read), recall (remember) and review ( summarize). I have seen how, using this method, beginners and advanced students turn into first-class scientists and thinkers.

I have seen how, using this method, beginners and advanced students turn into first-class scientists and thinkers.

I myself have always been a slow, methodical reader. There is something right about reading literary texts slowly and carefully, paying attention to the special language of literature. But large theoretical texts were my enemy. I could wade through the narrative, but by the time I got to the end, I didn't remember much of what I'd read. While reading a long textbook, I couldn't understand the difference between the main points and the secondary ideas. I needed some kind of strategy that would include more than just highlighting important points. nine0003

I started using the SQ3R method and saw results within a few weeks. This approach helped me organize my heavy reading load and improved comprehension and response. Now I read quickly with solid understanding. I have confidence that I can master any material.

Early in my teaching career, I knew that helping students meant teaching them critical reading strategies. But the SQ3R method can also be applied outside the university. This is an effective method for those who deal with complex texts. Using this approach, you can truly master any material and understand the intricacies of even the most complex texts. nine0003

But the SQ3R method can also be applied outside the university. This is an effective method for those who deal with complex texts. Using this approach, you can truly master any material and understand the intricacies of even the most complex texts. nine0003

Critical thinking leads to new knowledge

We create new knowledge based on the expertise of the past. Critical thinking means you don't just accept what the author has to offer. Reading critically means reading skeptically, comparing the author's opinion with one's own knowledge and worldview. Sometimes your ideas coincide with the author's ideas. But more often than not, your worldview and that of the author conflict.

Reading is a process of discovery. We are not just empty vessels that are filled from the cup of knowledge. While reading we are in a symbiotic relationship with the author, we create new meaning and new knowledge. By following a critical reading strategy, you can identify the strengths and weaknesses of an argument or approach and develop a new path. The author's view plus your own leads to new knowledge. The SQ3R method helps identify areas of the text that you can challenge to create a new understanding of the world. nine0003

The author's view plus your own leads to new knowledge. The SQ3R method helps identify areas of the text that you can challenge to create a new understanding of the world. nine0003

If all we had to do while reading was accept the author's point of view, our worldview would be hopelessly stuck at the level of the fourth grade or a book picture: so the author said. This passive reading strategy is important for young children who are just starting to read, but as we get older, we need to read much more actively in order to not only understand what the authors are saying, but also develop our own understanding of the world. And this is where the SQ3R comes to the rescue. You already know how to read. SQ3R organizes the reading process so that you can understand as much as you read. This is how reading becomes effective. nine0003

SQ3R Critical Reading Strategy

The method was proposed by educational psychologist Francis Pleasant Robinson in his 1946 book, Effective Teaching, which was intended to improve the reading skills of military personnel. The strategy is most useful for highly structured texts, but it can be applied just as effectively to fiction and shorter works. By following the five-part structure, you can become an active reader and improve your critical thinking skills. nine0003

The strategy is most useful for highly structured texts, but it can be applied just as effectively to fiction and shorter works. By following the five-part structure, you can become an active reader and improve your critical thinking skills. nine0003

Step 1 - Evaluate: look around before you jump

The first step is to evaluate the text, literally look at the material. If you have a text of 1000 pages, you must first understand what you are dealing with. Look at a book without reading it. Look at the cover. Scroll through the title. Then flip through it in its entirety, page by page, from beginning to end.

In the case of an e-book, you may need to make some adjustments to this step. However, you can look at the table of contents, note the length of the book, its structure, and (if possible) scroll through the pages. I read and teach using paper books and this article is based on applying the SQ3R method to them. You'll have to figure out how to apply these methods to e-books yourself. nine0003

nine0003

Do not read the text yet. Patterns should emerge. You will see the systematic presentation of ideas in the structure of the book. You will see chapter titles, subtitles and sub-subtitles. In academic textbooks, you can see new words in bold or italics. You may see illustrations, graphs, or action lists at the end of chapters. You can see illustrated examples. Scroll through the entire book. Studying the text is an important step, the basis for the rest of the strategy.

If your material is shorter, this process will take much less time. Look at the essay, for example. What is it called, who is the author? Does it have a subtitle? How many paragraphs are there? Are there empty spaces? Are any parts of the text highlighted? Regardless of what you read, pay attention to the structure of the piece when you evaluate it. nine0003

The human brain is an amazing organ. He finds patterns in everything he sees. By skimming through the text, you are tuning your brain to a subconscious understanding of the patterns that you present to it. That is, the brain finds meaning in them. You create a basis for the brain to understand the material. This skeleton supports the structure of the book's content in the same way that a human skeleton helps you stand upright. Without this structure, the content would be useless jelly that is difficult to understand in any structured way. nine0003

That is, the brain finds meaning in them. You create a basis for the brain to understand the material. This skeleton supports the structure of the book's content in the same way that a human skeleton helps you stand upright. Without this structure, the content would be useless jelly that is difficult to understand in any structured way. nine0003

Step 2 - ask questions: research plan

The second step is to write questions for each subheading in the text. Formulate them based on headings and subheadings. For example, a writing textbook might have a "Preparing to Write" section, and one of the subheadings might sound like "Freewriting." On a piece of paper, write down “What is freewriting?” Go through the entire text and write down questions for each heading and subheading.

At this time, you may be tempted to write down the answers to these questions, especially when these answers pop up in the text in front of you. But for now, it’s best to just write down all the questions and wait. You will answer them as you read. nine0003

You will answer them as you read. nine0003

Note: Recording material improves memory. When using the SQ3R, I write questions with pen and paper, while other times I mostly type on the computer. You can choose the recording method yourself - write or print. These recorded questions will be used as you read.

Step 3 - read: turn off all distractions and read

The third step is reading. Reading text is a two-step process. Read without a pencil for the first time. Just read quickly to grasp the main ideas and structure of the text. The second time, read carefully and take notes. nine0003

Reading without a pencil. Find a quiet place and read the material. Turn off your phone and TV. Personally, light or classical music in the background helps me concentrate better. The researchers believe that classical music puts "students in a heightened emotional state, making them more receptive to information."

If you have a lot to read, review the text first and perhaps split it into several sessions.

Reading is an activity of muscle memory. It takes 5-10 minutes to immerse yourself in reading. We can then read comfortably and with maximum productivity for about 40–60 minutes. After that, the mind starts to wander and we need a break. Rest 5-10 minutes, relax. Warm up and take a breather for the brain. And then keep reading or wait for the next session. nine0003

Second part of the reading: take notes. Comments will help you understand the patterns of the text. The purpose of reading is to find the main points of the text. How to highlight the most important in a sea of text? Professional text carefully edited and formatted.

Even the sentences themselves are well structured. Offers focus on details and supporting materials.

If the author writes: “The important point is…” or “The main point is…” or “The most important point to remember is…”, then you know that this point needs to be noted or emphasized. nine0003

By understanding where to find the most important information, you will be able to highlight the essential points.

Look for answers to the questions you wrote down in the second step. When you see the answer, write it down. If the answer is not provided directly, it may be implied. Write down any answer you can find in the text.

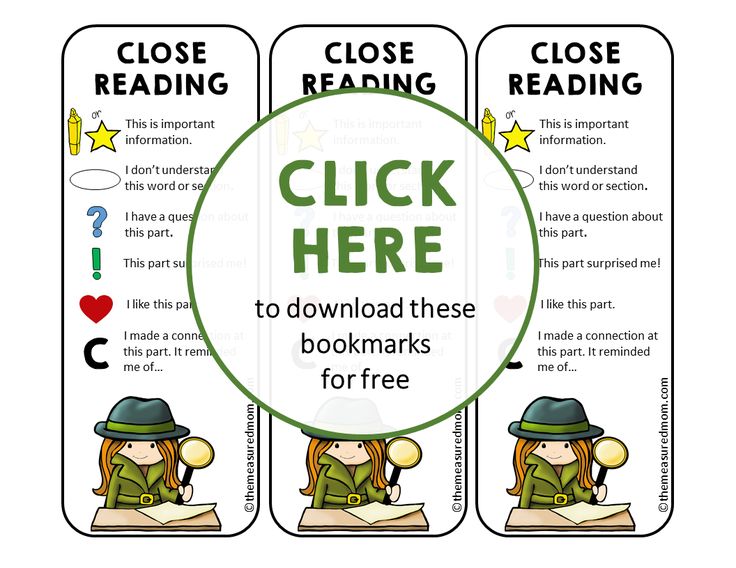

When you take notes, you actively read. Write throughout the text. If you work with paper, you can develop your own symbol system, as I did. (With e-books, you'll have to see what can be done, given the reader you're using. Because of these limitations, it may make more sense to work with a printed book, especially important texts.)

I underline key points and circle words I don't know. I look up the word in a good dictionary and write "Od" in the margin along with the definition. If I agree with the author's opinion, I write "Yes!". If I am skeptical of the author's point of view, I write "Hmmm" to indicate that I need to think a little more about this issue. If I do not agree with the author, then I write "Bullshit!" or something like that. If I see a pattern, like "First. ..Second...Third...", I box those structural elements and draw lines between them. If I have thoughts or comments about a passage, I write them in the margin. All these notes will be useful to me when I turn to this material again. nine0003

..Second...Third...", I box those structural elements and draw lines between them. If I have thoughts or comments about a passage, I write them in the margin. All these notes will be useful to me when I turn to this material again. nine0003

Here, for example, I have made many minor comments in an attempt to follow the thread of the argument. De Beauvoir has an extensive vocabulary, so to be precise, I check for any word that may have some nuanced meaning. I check words that I think I know well, and it turns out that I do not have a completely accurate working meaning of the word. It's important to be honest with yourself and check for words you don't know or that might not mean exactly what you think.

Develop your own note-taking system. Whatever you do, write in the text. If you don't want to write in the book, make a copy to read and take notes in it. Recording comments is an important step in understanding the material. nine0003

As for highlighting: I have seen many beginning students highlight entire pages of text. When everything is selected, nothing is selected. Use selection sparingly. I try to highlight only the main points of each chapter, if at all.

When everything is selected, nothing is selected. Use selection sparingly. I try to highlight only the main points of each chapter, if at all.

Step 4 - Remember: Voice Your Ideas

The fourth step is to tell the main points of the text to a friend or to yourself. When we voice any material, we form memories of it in the brain. By telling a friend about what you read, you can remember it. It will also help you clarify any disagreements you may have with the text. Why do you disagree with the author and what is your own position? It is not enough to simply disagree with the author's point of view. You should also try to formulate the reason for your disagreement, which will help you formulate your own view on the subject. This step in critical thinking is important for creating new knowledge. nine0003

Step 5 - Summarize: strengthen the whole process to really absorb the text

The fifth and final step is to sum up. This is the sixth time you will be looking at the material being studied. You didn’t just understand the author’s point of view, you actively read the text.

You didn’t just understand the author’s point of view, you actively read the text.

After you have critically reviewed the text six times, I guarantee that, if you are faithful to the SQ3R method, you have mastered most of the material. Your task is not to remember the text, although some parts of it will be deposited in memory verbatim. Rather, your task is to understand the main points and structure of the text, to know its strengths and weaknesses, as well as your reaction and attitude to this material. You have now become an expert on this material and have created new knowledge. nine0003

You are now ready to do something with this new knowledge—present information to the board of directors, take an exam, or write an article that takes the other author's position into account along with your arguments.

Using the SQ3R strategy for critical reading may require more reading time, especially when you are writing focused questions and developing a workable note outline. But if you use this strategy consistently, you will noticeably improve your reading comprehension. nine0003

But if you use this strategy consistently, you will noticeably improve your reading comprehension. nine0003

Reading is often the first step not only in learning new knowledge, but also in creating it. The SQ3R critical reading strategy will help you understand any text, from the most difficult to the most trivial. It will increase your interest in reading, help you think critically about what you read, and allow you to create new knowledge for the world.

We don't just discover the world through reading. We create the world we live in. Now it's your turn to create the beautiful world you want to live in. nine0003

Strategies for meaningful reading in literature lessons (from work experience)

Knowledge is knowledge only when it is acquired by the efforts of one's thought, and not by memory. L.N. Tolstoy To understand a text means to understand it as a word that the author speaks to us with.

Three-level model of text comprehension

The name of the level of understanding

depth

1. Actual

penetration into the meaning

Facts of text, expressed explicitly in the lines of text

2. Interprete

Where is the answer?

3. Application

Text and context, their understanding and interpretation, reading between the lines

In text sentences

Purpose of reading

Cognitive

Text, context, generalization and evaluation beyond lines of text

Compilation of an answer from: a) separate parts of the text;

b) the position of the author of the text and the reader

Cognitive

Compiling an answer from:

a) the position of the author of the text and the reader;

Emotional

b) only the position of the reader

According to this model, the "Bloom's taxonomy" (taxonomy - from other Greek. arrangement, structure, order) of questions was built. nine0104

arrangement, structure, order) of questions was built. nine0104

The Question Tree strategy was created on the basis of a three-level model of text comprehension. KRONA (actual level): What? Where? When? BARREL (interpretive): Why? How? Could you…? What if…? Should...? ROOTS (application): How does the text relate to life? How does the text relate to current events? What was the author trying to show us?

From work experience Let's analyze an excerpt from story "The Captain's Daughter" grade 8, chapter "Duel". CROWN (purpose of reading: cognitive; facts of the text expressed clearly in the sentences of the text): What? Duel... Where? At the fortress… When? Day…

BARREL ( target reading : cognitive) (text and context, their understanding and interpretation, reading between the lines composing an answer from separate parts of the text; the position of the author of the text and the reader): Why? Insulted… How? An unambiguous allusion was made to Masha Mironova, discrediting her honor. .. Could you resolve this situation in another way? … What if Shvabrin would apologize to Masha Mironova?.. Should Petr Grinev stand up for Masha?...

.. Could you resolve this situation in another way? … What if Shvabrin would apologize to Masha Mironova?.. Should Petr Grinev stand up for Masha?...

ROOTS ( purpose of reading : emotional) (text, context and subtext, generalization and evaluation beyond the lines of text; making up an answer from: the position of the author and the reader or only the position of the reader): How to correlate the events of this chapter with life, current events? ... What did the author try to show us by using the opposition technique in the chapter? ...

Question tree

- What? Where? When?

- Why? How?

- How? What?

From the strategy of guided reading, the transition to the strategy of reader responses is carried out.

Focuses on fluency and phonics with additional support for vocabulary.

Focuses on fluency and phonics with additional support for vocabulary.