When does the development of phonological awareness skills take place

Phonological Awareness: What Is It? What Are the Developmental Milestones?

Skip to contentPrevious Next

- View Larger Image

By: Katrina Wasserman MA, CCC-SLP

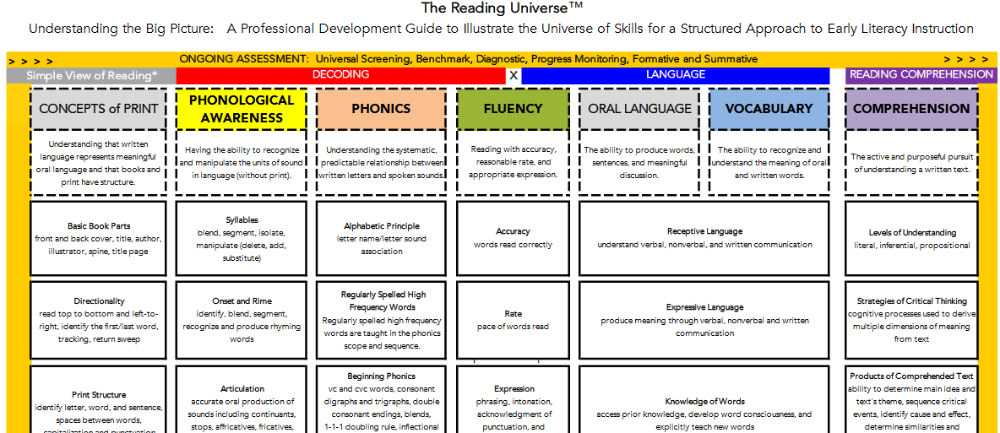

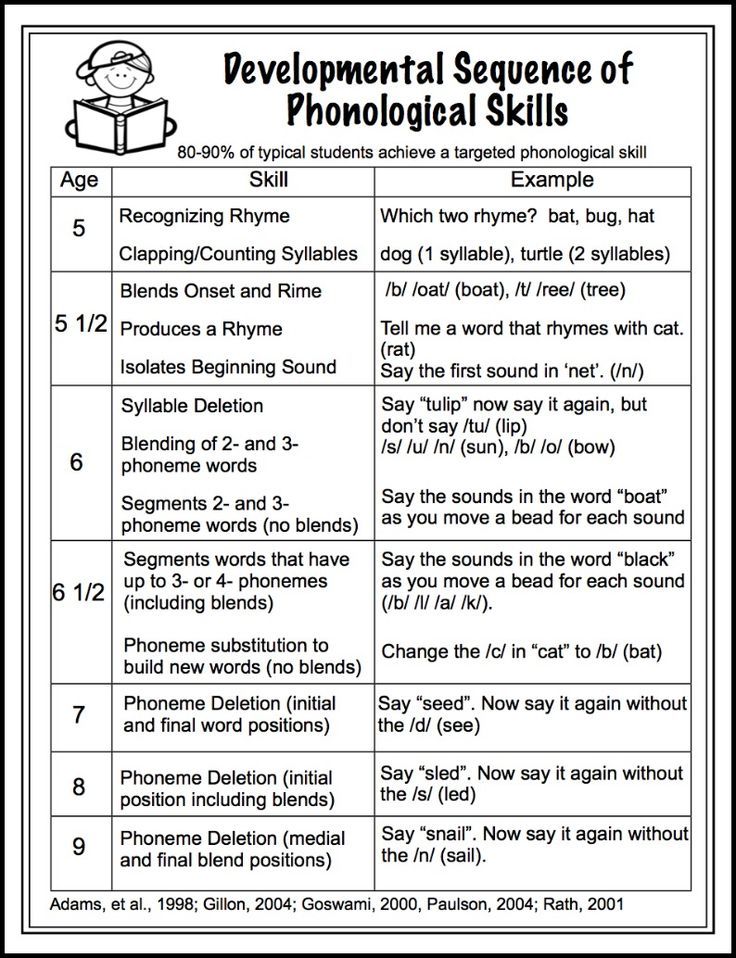

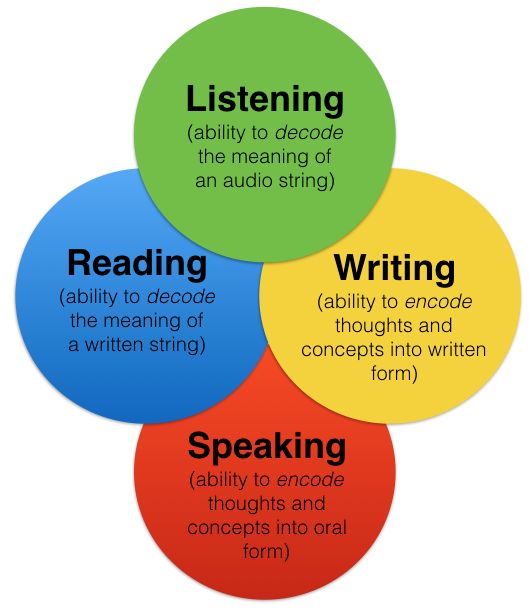

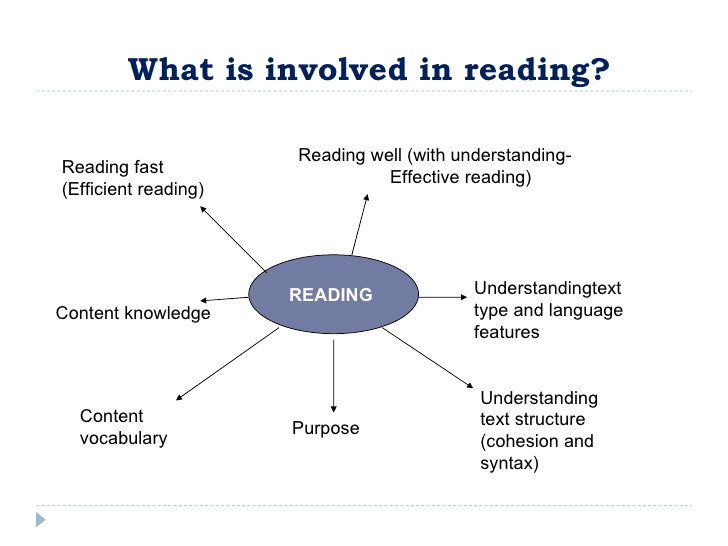

Phonological awareness refers to the knowledge of sounds and how sounds can be manipulated to form words. It is a crucial foundational skill, as it is correlated to success in reading and writing. Prior to phonological awareness, a child must have strong basic listening skills.

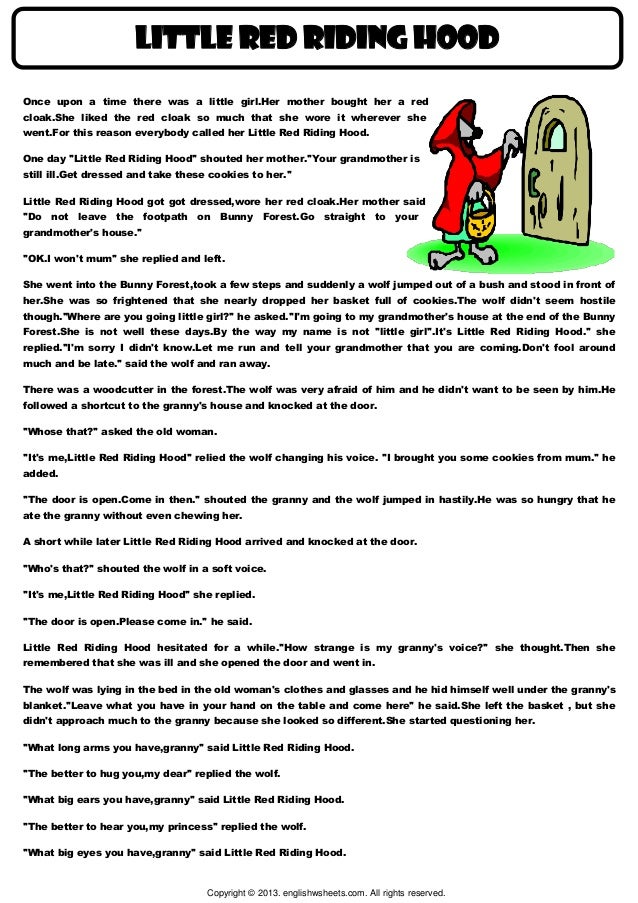

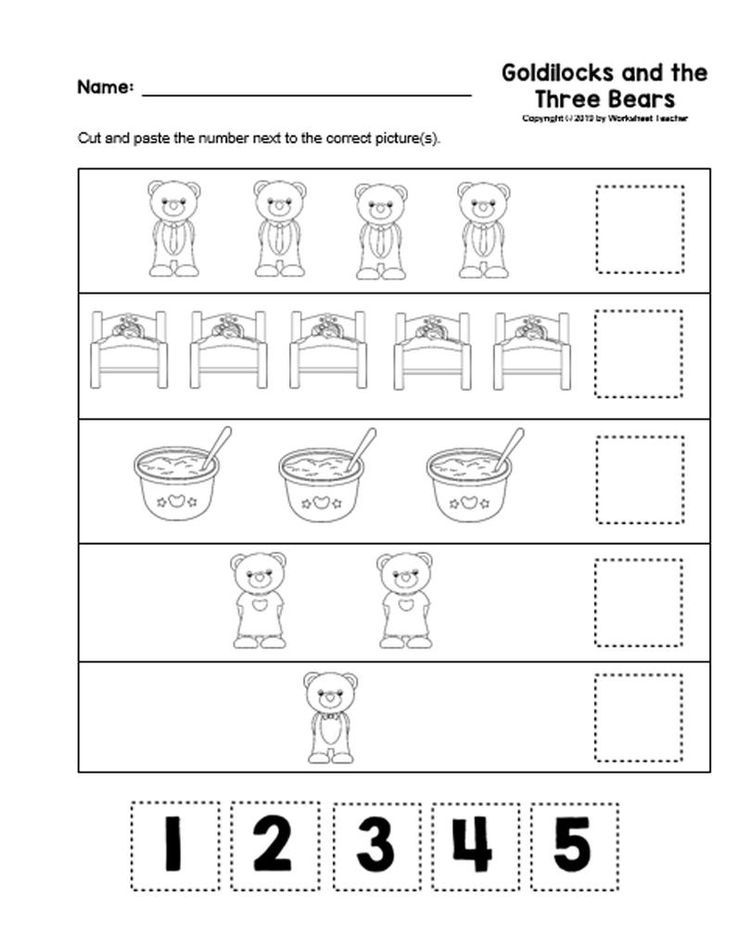

Pre-phonological awareness skills include word awareness and enjoying rhyming and alliterations in songs and stories. These skills are generally acquired before the age of 4, and children learn them through songs, nursery rhymes, and finger play songs. Some songs that highlight these skills include B-I-N-G-O, Hickory Dickery Dock, and Down By the Bay.

The first phonological awareness skill to develop is rhyming. Between the ages of 3 and 4, a child begins to generate rhyming words. At this time, the child may have a mix of real and nonsense rhyming words. Children frequently enjoy playing with rhyming words and get excited when they produce a real rhyming word that they haven’t heard before!

Between the ages of 4 and 5, many phonological skills develop. Children will break words into their individual syllables; this is usually achieved by clapping or tapping out the individual sounds in multisyllabic words such as butterfly. Children will begin to recognize two words that begin with the same sound (e.g., dog and dance). Word segmentation and blending are also acquired at this time.

Segmentation refers to the separating of sounds in words and blending refers to the combining of sounds into words. For example, given the sounds S- U- N, the child would blend these sounds together to form the word sun. Conversely, segmentation is when a child is given a word like boat and segments it into its individual sounds B-OA-T. Both sills involve the manipulation of sounds within words. After the child has acquired this skill, he/she should be able to count how many phonemes (sounds) are in a word. (e.g., boat = 3 sounds)

Both sills involve the manipulation of sounds within words. After the child has acquired this skill, he/she should be able to count how many phonemes (sounds) are in a word. (e.g., boat = 3 sounds)

Between the ages of 5 and 6, the prior phonological skills are expanded and more finely tuned. Children will be able to blend and segment words that have 4 sounds, specifically with consonant blends (e.g., hand). Children will be able to identify the first and last sounds in a word. Once this skill is achieved, a child will be able to generate words that begin with the same sound.

For example, given the word mop, a child would be able to generate other words that begin with the M sound such mat, make, milk. Auditorally, the child will be able to determine which word does not rhyme in a set (e.g., fin- win- car) and which word is different in a set of three (e.g., pick- pack- pick).

Between the ages of 6 and 7, children’s skills include a variety of higher-level sound manipulation. Children should be able to delete syllables from words (e.g., say the word cowboy, now say it without boy) and delete sounds from words (e.g., say the word mice, now say it without M). Sound and syllable substitutions will be acquired during this time. For example, say the word fast, now change the f to a p (i.e., past).

Children should be able to delete syllables from words (e.g., say the word cowboy, now say it without boy) and delete sounds from words (e.g., say the word mice, now say it without M). Sound and syllable substitutions will be acquired during this time. For example, say the word fast, now change the f to a p (i.e., past).

By the age of 8, children will use their phonological awareness skills in their writing to spell words correctly. Phonological awareness is crucial in a child’s ability to read and write. It enables them to understand that our language is comprised of sounds that work together to form words and is a predictor of reading success.

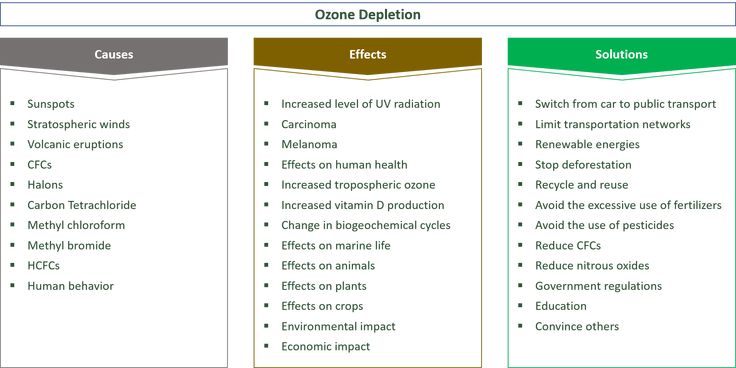

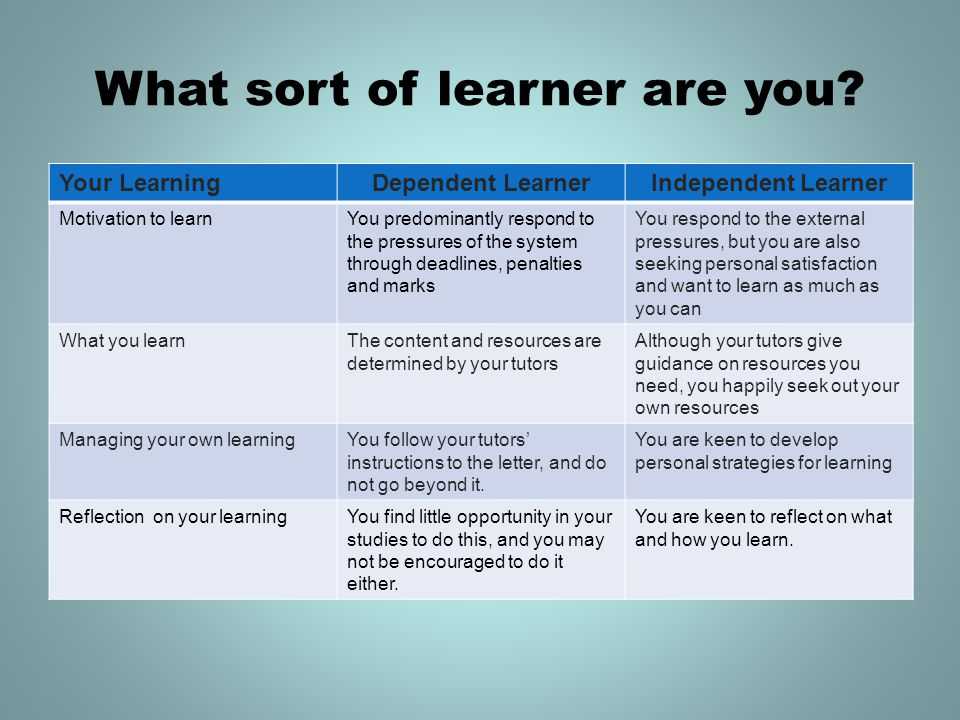

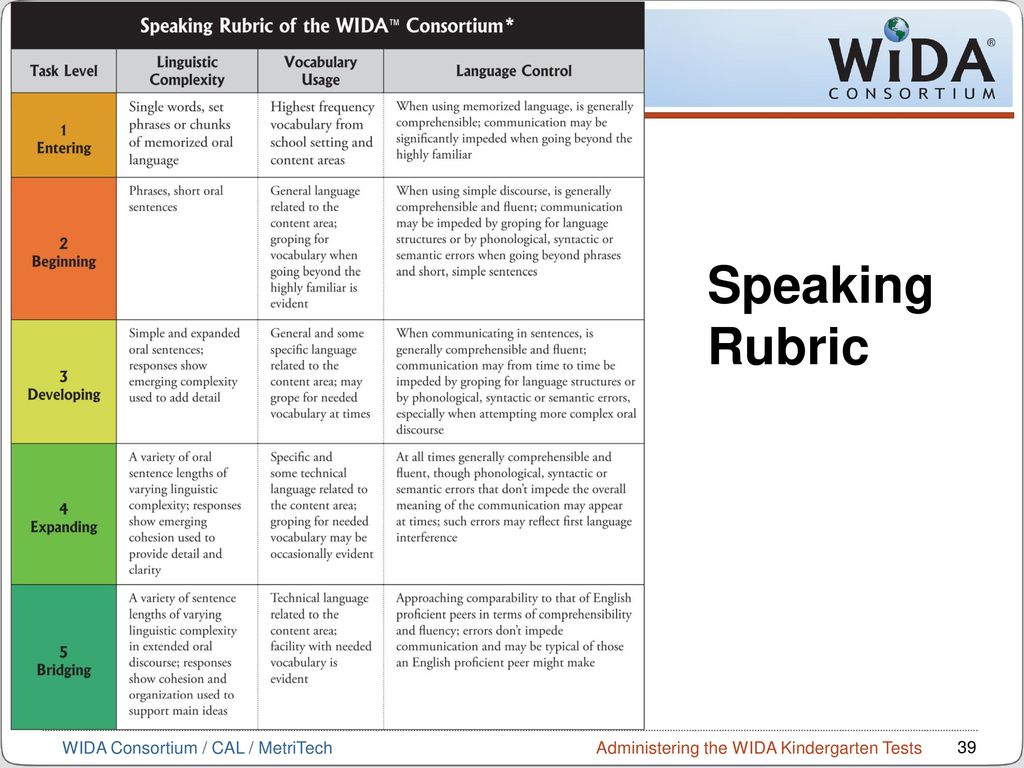

Check out this chart, which highlights the information above!

If you have questions about your child’s phonological awareness skills or would like to know if therapy is appropriate for your child, contact us today!

Page load link Go to TopPhonological (Sound) Awareness Development Chart

< Back to Child Development Charts

Phonological Awareness is the knowledge of sounds (i. e. the sounds that letters make) and how they go together to make words.

e. the sounds that letters make) and how they go together to make words.

Note: Each stage of development assumes that the preceding stages have been successfully achieved.

How to use this chart: Review the skills demonstrated by the child up to their current age. If you notice skills that have not been met below their current age contact Kid Sense Child Development on 1800 KIDSENSE (1800 543 736).

| Age | Developmental milestones | Possible implications if milestones not achieved |

| 0-2 years |

|

|

| 2-3 years |

|

|

| 3-4 years |

|

|

| 4-5 years |

|

|

| 5-6 years |

|

|

| 6-7 years |

|

|

| 7-8 years |

|

|

This chart was designed to serve as a functional screening of developmental skills per age group. It does not constitute an assessment nor reflect strictly standardised research.

It does not constitute an assessment nor reflect strictly standardised research.

The information in this chart was compiled over many years from a variety of sources. This information was then further shaped by years of clinical practice as well as therapeutic consultation with child care, pre-school and school teachers in South Australia about the developmental skills necessary for children to meet the demands of these educational environments. In more recent years, it has been further modified by the need for children and their teachers to meet the functional Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) requirements that are not always congruent with standardised research.

6 Reading Comprehension Skills

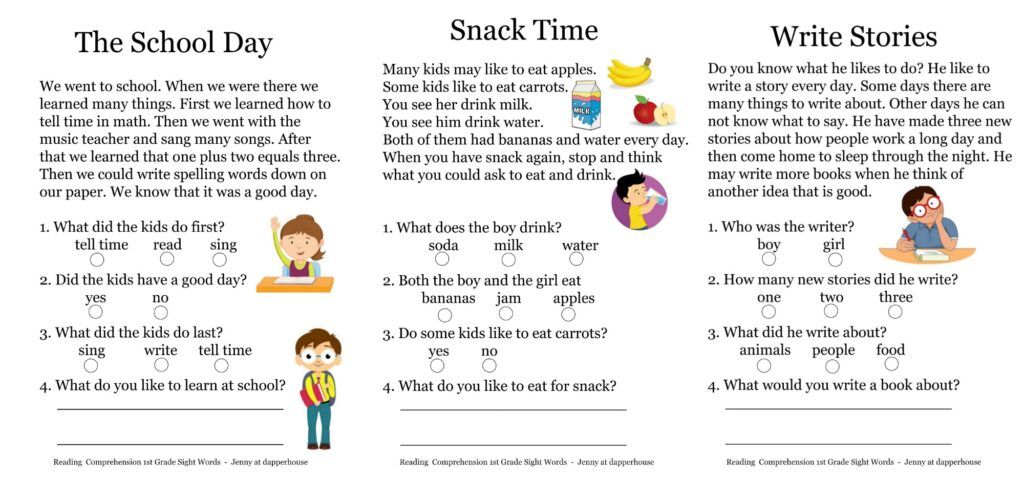

For some people, reading is like a walk in the park on a warm summer day, an enjoyable activity that is easy to master. In fact, reading is a complex process that involves many different skills. Together, these skills lead to the ultimate goal of learning to read: comprehensive reading comprehension.

Text comprehension can be difficult for children for many reasons, but regardless of them, knowing what underdeveloped skills this is due to, you will be able to provide your child with the best help.

Let's take a look at the six reading comprehension skills and how you can help your child develop them.

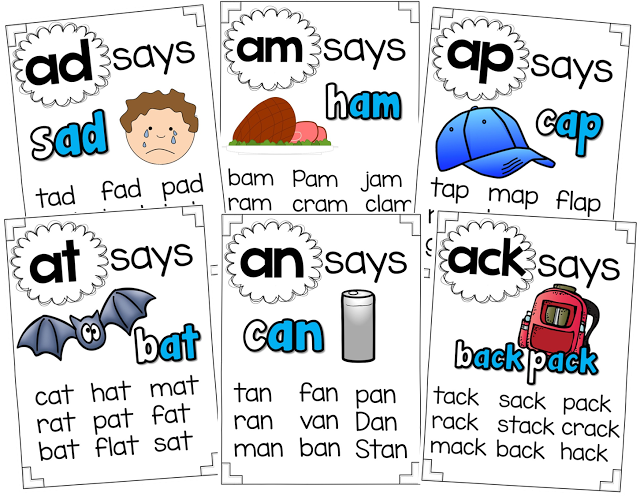

1. Decoding

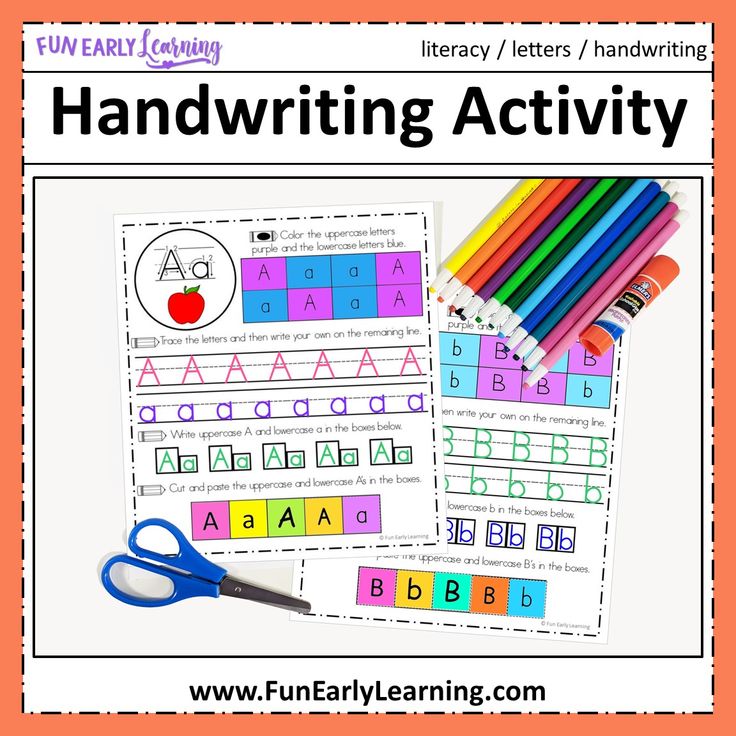

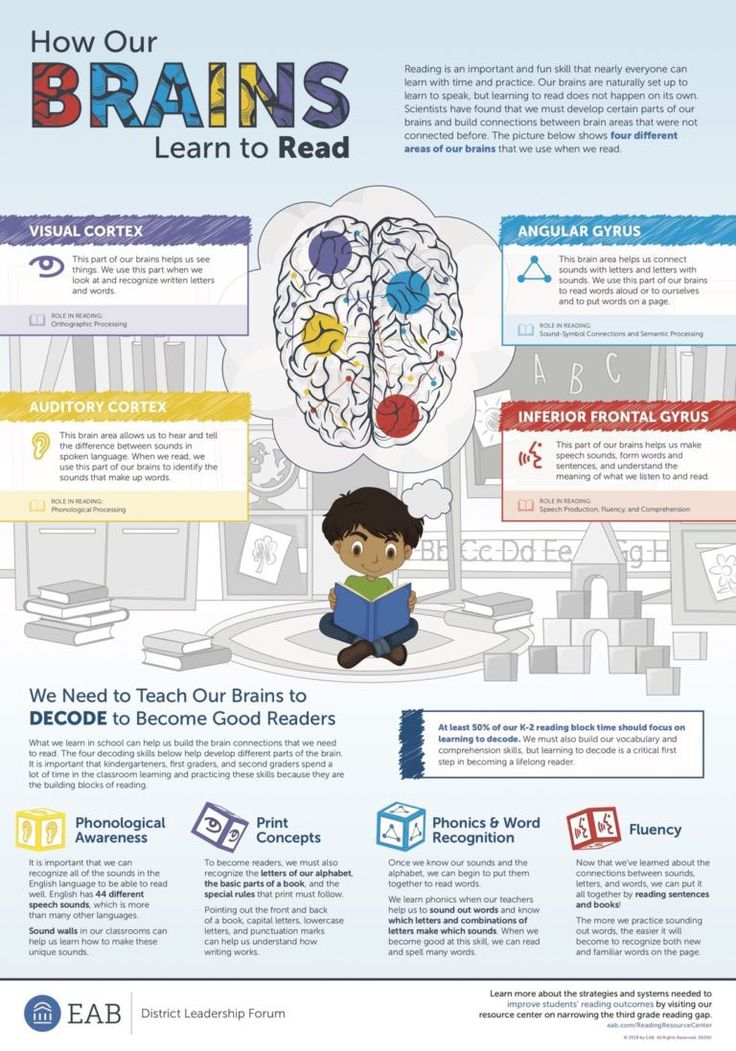

Decoding is an extremely important step in the reading process. Children use this skill to sound out words they have heard before but not seen written. The ability to decode is the foundation of all other reading skills.

Decoding relies on one of the first language skills to develop, phonemic comprehension (this skill is part of a broader set of skills called phonological comprehension). Phonemic awareness allows children to hear and distinguish individual sounds in words (also known as phonemes). It also allows them to "play" with sounds in syllables and words.

Decoding also relies on the ability to match individual sounds and letters. For example, to read the word "sun", the child must know that the letter "s" sounds like "s". Understanding the relationship between letters and sounds is an important step towards "voicing" words.

For example, to read the word "sun", the child must know that the letter "s" sounds like "s". Understanding the relationship between letters and sounds is an important step towards "voicing" words.

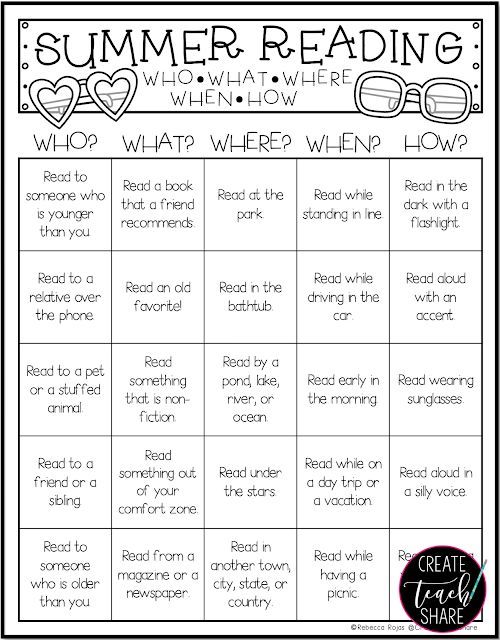

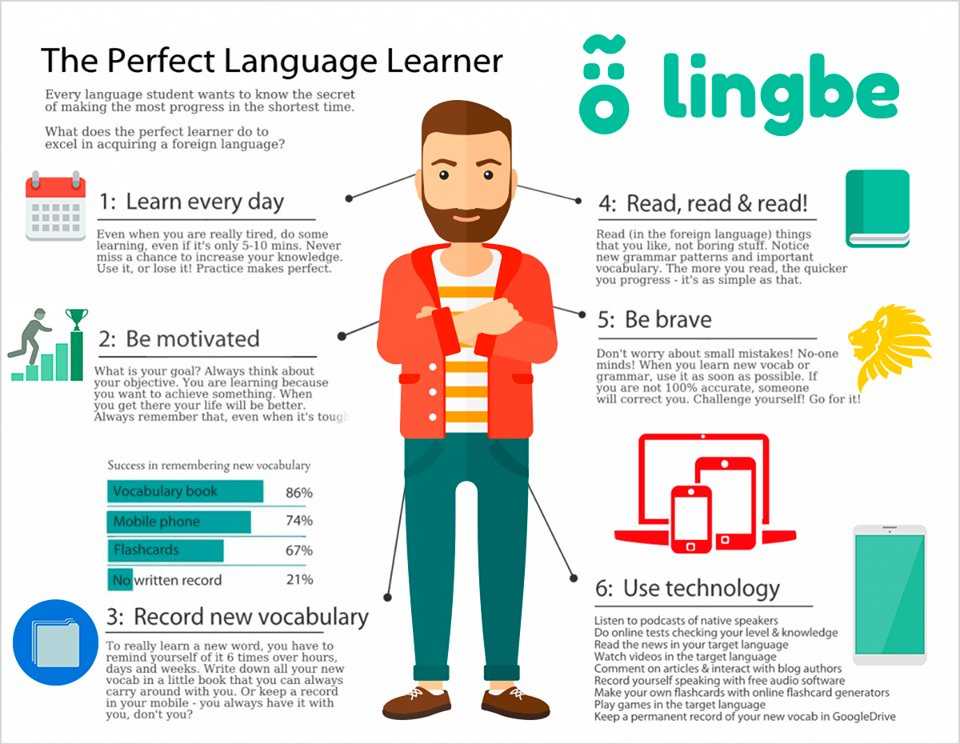

How to help: Many children learn phonological awareness naturally by reading books, listening to songs and poems. But for some children it is not so easy. In fact, one of the earliest signs of reading difficulty is trouble with rhyming, counting syllables, or identifying the first sound in a word.

The best way to help your child improve these skills is to guide them with precise instructions and lots of practice. Children need to be taught how to correctly identify sounds and work with them. You can also develop phonological perception by playing with words, reading poems aloud to your child, or using special computer techniques aimed at developing phonemic perception and decoding.

2. Reading fluently

To read fluently, children must recognize words immediately, including words that do not read as they are written. By developing reading fluency, the child increases not only reading speed, but also reading comprehension.

By developing reading fluency, the child increases not only reading speed, but also reading comprehension.

Decoding and reading each word can be a lot of work. Word recognition is the ability to recognize a word instantly just by looking at it, without having to read it out loud. When children can read quickly and with almost no errors, they are said to be able to read "fluently".

People who can read fluently read fluently and rhythmically. They use the context to understand the meaning and change the intonation in their voice depending on what they are reading about. The ability to read fluently is critical to a good understanding of the text.

How to help: Word recognition can be a big hurdle for beginning readers. Usually a person needs to see a word from 4 to 14 times in order to learn to automatically recognize it. But, for example, children diagnosed with dyslexia may need to see the word up to 40 times.

Many children have difficulty reading fluently. To improve word recognition and other reading skills, children need help and a lot of practice. The best way to strengthen these skills is to practice reading books. It is important to choose books that are appropriate for the child's reading level.

To improve word recognition and other reading skills, children need help and a lot of practice. The best way to strengthen these skills is to practice reading books. It is important to choose books that are appropriate for the child's reading level.

3. Vocabulary

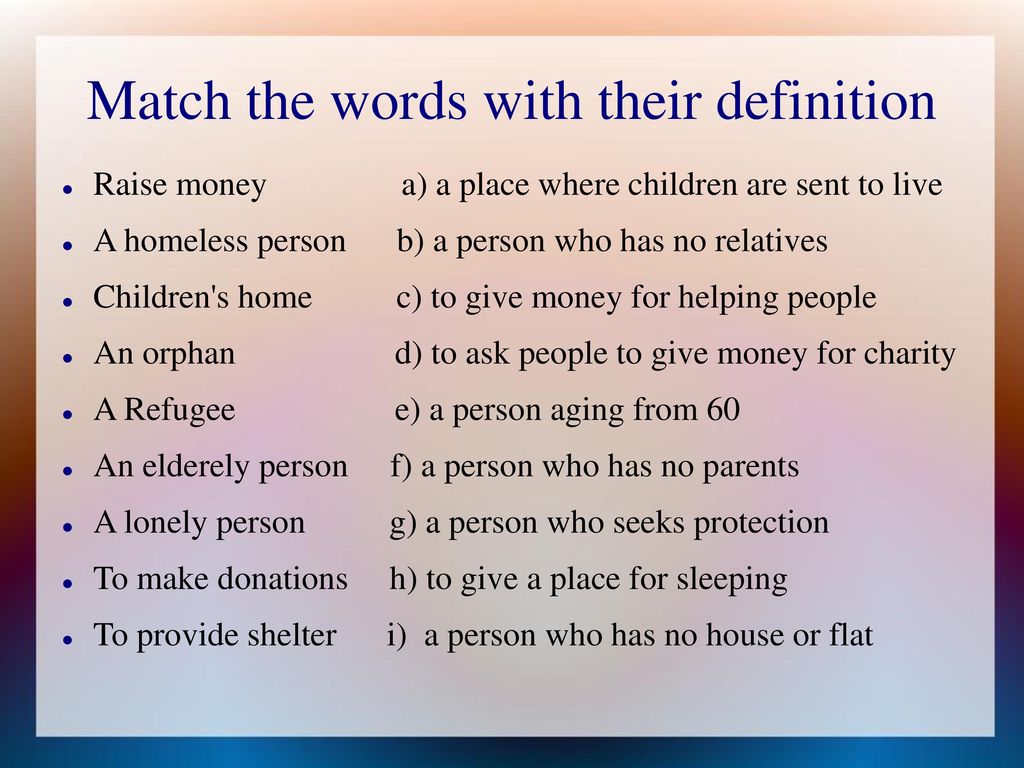

To understand what you read, you need to understand at least most of the words in the text. A rich vocabulary is a key component of text comprehension. Students can learn new words during class, but they usually learn the meaning of words through everyday situations and while reading.

How to help: The more new words children learn, the more their vocabulary grows. You can help your child develop vocabulary by talking to him often about different topics, introducing him to new words and concepts. Word games and funny jokes are also fun ways for children to reinforce these skills.

Daily reading together also helps to build vocabulary. When reading aloud to your child, stop when you encounter new words and explain their meaning. But it is also important that the child reads independently. Even if there is no one to explain the meaning of a new word, the child can guess its meaning from the context, and also learn with the help of a dictionary.

But it is also important that the child reads independently. Even if there is no one to explain the meaning of a new word, the child can guess its meaning from the context, and also learn with the help of a dictionary.

Teachers can also help by choosing interesting words to study and learning them all together in class. To practice vocabulary, the teacher can engage students in dialogue during the lesson, or play word games to make learning new words fun.

4. Sentence construction and cohesion

Understanding how sentences are built can seem like a skill necessary for writing. The same can be said about the connection of ideas within and between sentences, which is called cohesion. But these skills are also important for reading comprehension.

Knowing how ideas connect at the sentence level helps children make sense of passages and entire texts. This also leads to what is called coherence, or the ability to relate ideas to other ideas in a common work.

How to help: Explain the basics of sentence construction to your child. Work with him to connect two or more thoughts, both in writing and orally.

5. Expanding horizons and reasoning

read. It is also important to teach the child to “read between the lines” and find meaning where it is not literally written.

How to help: Your child can broaden their horizons through reading, socializing, watching movies and TV shows, and exploring art. Also many things come with years of personal experience.

Open up opportunities for your child to gain new useful knowledge in different areas and discuss with him what you have learned from the experience gained, both together and separately. Help your child make connections between new and old knowledge and ask questions that require extended answers and thoughtful explanations.

You can also read these tips on how to use cartoons to help your child learn to judge for themselves.

6. Working memory and attention

These two skills are part of a group of skills also known as executive functions. They are different, but closely related.

When children read, attention allows them to absorb information from the text. Working memory helps them retain this information and use it to make sense and gain knowledge from what they read.

The ability to control oneself while reading is also related to executive functions. The child must be able to recognize when he does not understand something, stop, go back and reread, so that there is no doubt about the understanding of what he read.

How to help: There are many ways to help your child improve working memory, and it doesn't have to look like a lesson. There are many games and daily activities that can help develop working memory in a way that your child won't even notice!

To improve your child's concentration, look for reading materials that interest and/or motivate your child. For example, some children love graphic novels. Teach your child to stop and reread the text when something is not clear to him. And show him how you “think out loud” when you read to make sure it makes sense.

For example, some children love graphic novels. Teach your child to stop and reread the text when something is not clear to him. And show him how you “think out loud” when you read to make sure it makes sense.

More ways to help with text comprehension

When children have difficulty learning the above skills, they may find it difficult to fully understand what they read.

Find out what might be causing your child's reading difficulties. Remember, if a child has difficulty reading, it does not mean that he is not smart. But some children need extra support to successfully develop reading skills. The sooner you contact a specialist or start applying a special corrective technique, the less stress and lag in learning and development your child will receive. Pay attention to the computer technique Fast ForWord, aimed at developing the skills of phonemic perception, decoding, memory, concentration and other executive functions.

Pins

-

Decoding, reading fluency and vocabulary are key skills needed for reading comprehension.

-

Understanding how ideas connect within and between sentences helps children understand the entire text.

-

Reading aloud and discussing experiences can help a child develop reading skills.

Literacy as a result of language development and its impact on the psychosocial and emotional development of children

Bruce Tomblin, PhD

University of Iowa, USA

, 2nd ed. (English language). Translation: June 2016

Introduction

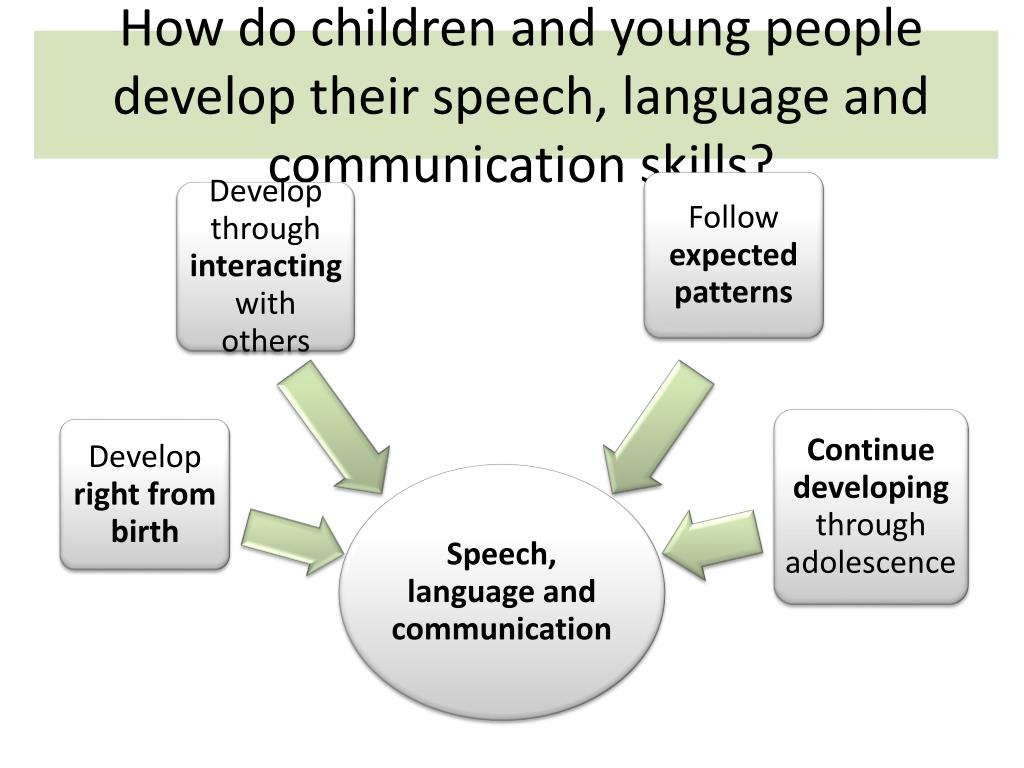

One of the most amazing achievements in the preschool years is the child's effortless development of speech and language. From the point of view of the development of oral speech, the preschool years are a period of language learning. When children enter school, they are expected to use these newly acquired language skills as tools for learning and, to an increasing extent, for negotiating with others. The important role of oral and written communication in the lives of schoolchildren suggests that individual differences in these skills may entail risks to broader academic and psychosocial competence.

From the point of view of the development of oral speech, the preschool years are a period of language learning. When children enter school, they are expected to use these newly acquired language skills as tools for learning and, to an increasing extent, for negotiating with others. The important role of oral and written communication in the lives of schoolchildren suggests that individual differences in these skills may entail risks to broader academic and psychosocial competence.

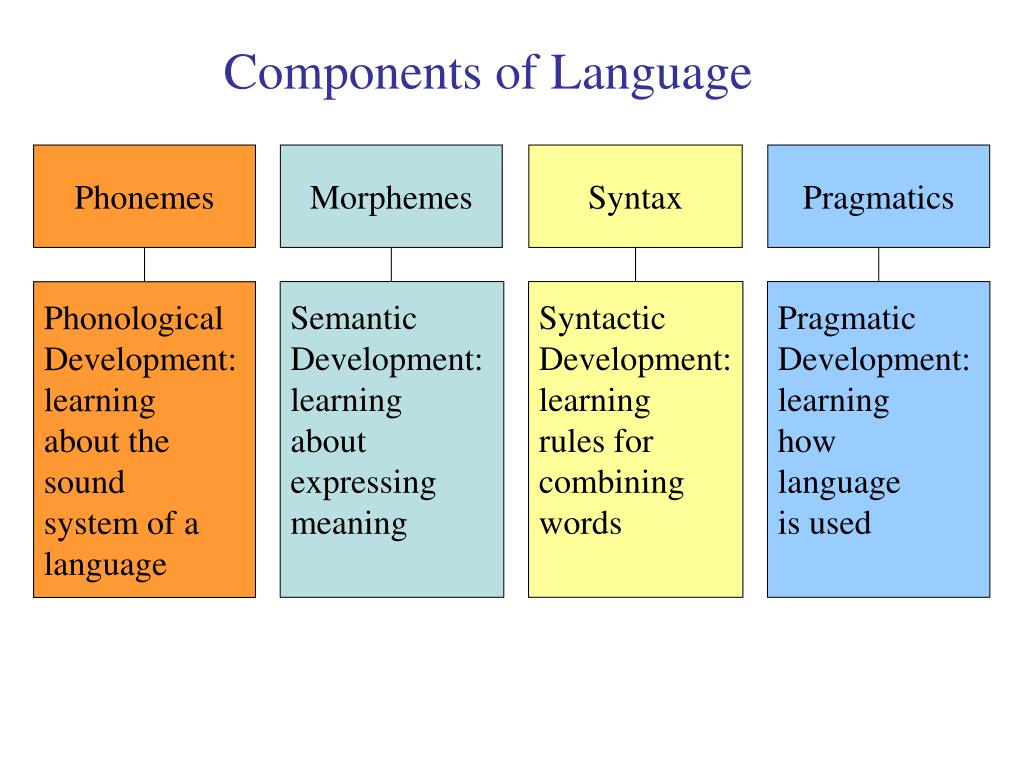

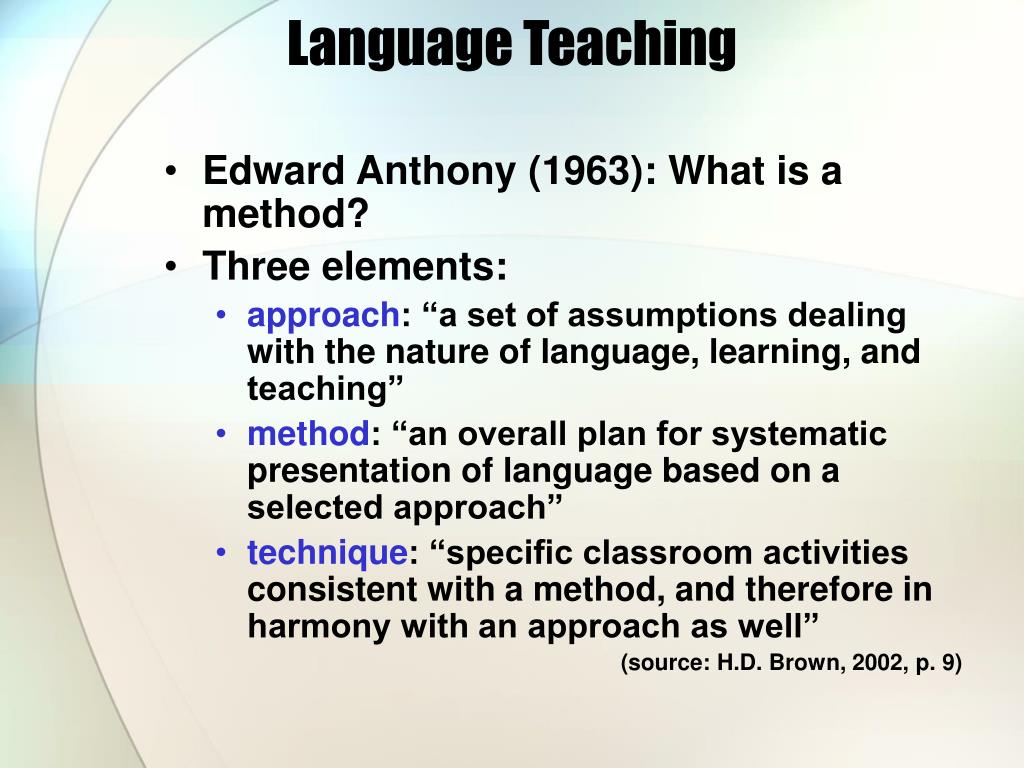

Subject

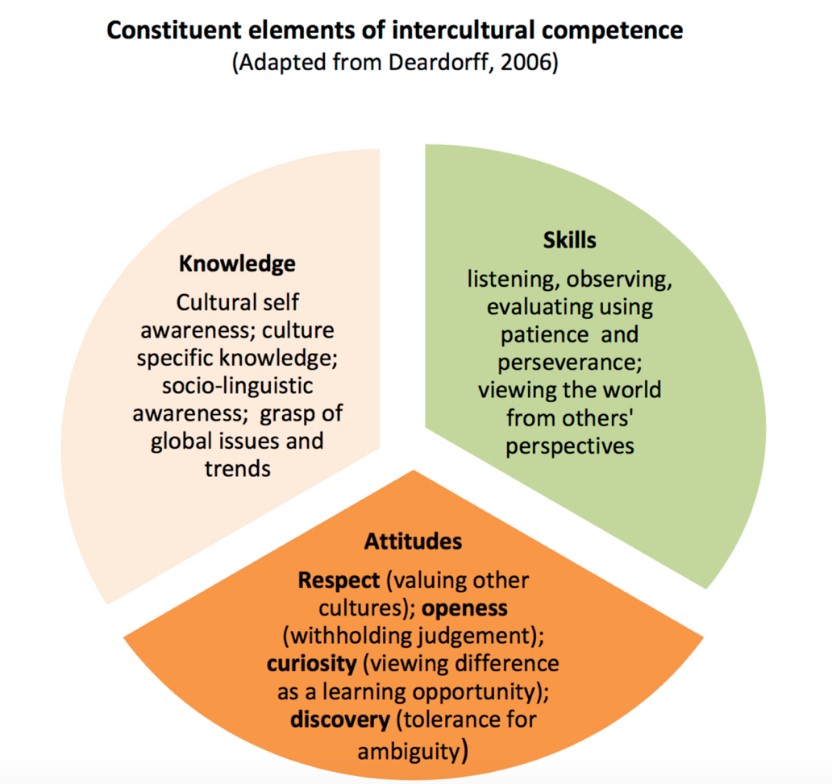

Oral language competence includes several systems. Children must master the system of representing the meaning of things in their world. Children should also achieve ease in using the forms of language, from the sound structure of words to the grammatical structure of sentences. In addition to this, social competence must be added to this knowledge. The development of these skills, which occurs in the preschool period, will allow the child to successfully act as a listener and speaker in various communication contexts. For the most part, this learning occurs naturally, without specially organized training, and, as you know, is unconscious in nature. Even as preschoolers, children begin to develop awareness of some of this knowledge. They can rhyme words, and they can also manipulate parts of words, such as dividing the word "child" into two syllables: /di/ and /tya/. This ability to think about the properties of words is called phonological processing. There is a solid body of evidence that early reading development in alphabetic languages, such as English, depends on the development of acquired phonological processing skills. 1

For the most part, this learning occurs naturally, without specially organized training, and, as you know, is unconscious in nature. Even as preschoolers, children begin to develop awareness of some of this knowledge. They can rhyme words, and they can also manipulate parts of words, such as dividing the word "child" into two syllables: /di/ and /tya/. This ability to think about the properties of words is called phonological processing. There is a solid body of evidence that early reading development in alphabetic languages, such as English, depends on the development of acquired phonological processing skills. 1

Learning to read also requires some skills. It is customary to distinguish between two main aspects of reading - word recognition and reading comprehension. Word recognition is about understanding how a word is pronounced. Experienced readers can do this using numerous "hints", but what is important is that they are able to use the conventional rules regarding the relationship between a sequence of letters and their pronunciation (decoding). It turns out that phonological processing abilities play an important role in the development of this knowledge and in the ability of an individual to recognize words. However, decoding printed words is not essential for reading competence. The reader needs to be able to interpret printed text in much the same way that he understands sentences when he hears them. The skills used in this process of reading comprehension are similar or the same as those used in listening comprehension.

It turns out that phonological processing abilities play an important role in the development of this knowledge and in the ability of an individual to recognize words. However, decoding printed words is not essential for reading competence. The reader needs to be able to interpret printed text in much the same way that he understands sentences when he hears them. The skills used in this process of reading comprehension are similar or the same as those used in listening comprehension.

Issues

Children may enter school with poor listening, speaking and/or phonological processing skills. Children with poor listening and speaking skills are defined as children with language impairments (LI) and most of them will also show poor phonological processing abilities. According to the current estimate, about 12% of children entering school in the US and Canada have JAN. 2.3 There are other children who are competent enough in listening and speaking to be considered "normal" in this regard, but for whom phonological processing remains a weakness. These children may be considered at risk for developing reading disorders (RD) when they enter school. Reading disorder is traditionally defined as a low level of reading proficiency that occurs after sufficient opportunities have been gained to learn to read. Therefore, the diagnosis of RF is made after two or three years of learning to read. RF prevalence rates among schoolchildren vary between 10% and 18%. 4.5 Behavioral problems such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and internalizing problems such as shyness and anxiety have been found to be common among children with RF and similarly among children with JD .6

These children may be considered at risk for developing reading disorders (RD) when they enter school. Reading disorder is traditionally defined as a low level of reading proficiency that occurs after sufficient opportunities have been gained to learn to read. Therefore, the diagnosis of RF is made after two or three years of learning to read. RF prevalence rates among schoolchildren vary between 10% and 18%. 4.5 Behavioral problems such as Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and internalizing problems such as shyness and anxiety have been found to be common among children with RF and similarly among children with JD .6

Scientific context

The relationship between oral language development, reading development, and social development has been studied by several researchers who have attempted to determine the extent to which these problems are related to each other and to identify the basis for these relationships.

Key questions

Significant research questions have been about the extent to which early language status portends later reading and behavioral problems, and what possible grounds for these relationships might be. In particular, two hypotheses are clearly traced in the literature. According to one hypothesis, the relationship between oral language and further outcomes is of a causal nature. According to another hypothesis, the association of behavioral problems with language problems and reading problems may stem from a common pathological condition - for example, retardation of neurobiological maturation, which leads to poor achievement in both areas.

Recent research findings

A number of researchers have studied the psychosocial consequences and outcomes of reading in primary school children with ID. Some studies have noted that children with language impairments had a lower level of reading development, and RF was more common. 7-12 In these studies, the prevalence of RF in children with JAN ranged from 25% to 90%. 11 It has been found that the strong relationship between RF and JN is due to the limitations that these children have in both language comprehension and phonological awareness. 13.14 Lack of phonological awareness may put them at risk of having difficulty learning decoding skills, and problems with listening comprehension may lead to difficulty in reading comprehension.

7-12 In these studies, the prevalence of RF in children with JAN ranged from 25% to 90%. 11 It has been found that the strong relationship between RF and JN is due to the limitations that these children have in both language comprehension and phonological awareness. 13.14 Lack of phonological awareness may put them at risk of having difficulty learning decoding skills, and problems with listening comprehension may lead to difficulty in reading comprehension.

Several studies have found an increased rate of behavioral problems among children with UI. 2.15-20 The most common behavioral problem reported in these studies was ADHD; however, problems of the internalizing type, such as anxiety disorder, have also been noted. Some studies have found that these behavioral problems seem to vary depending on the setting in which the child is observed, with these problems reported mostly by the children's teachers rather than their parents. 21 This has been interpreted as evidence that such behavioral problems may occur more frequently in the school setting than at home and are thus a response to school stress. Further support for this view comes from evidence that a predominance of behavioral problems in children with RF and/or JAN is found in children with both disorders. 6 Thus, these studies support the notion that JON combined with RF results in the child experiencing excessive failure, especially in the classroom, which in turn leads to behavioral problems of a reactive nature. These findings, however, cannot explain why behavioral problems are found in preschool children with ID. 22 This information can be used to argue that a common factor, such as neurodevelopmental delay, contributes to the development of all these disorders.

21 This has been interpreted as evidence that such behavioral problems may occur more frequently in the school setting than at home and are thus a response to school stress. Further support for this view comes from evidence that a predominance of behavioral problems in children with RF and/or JAN is found in children with both disorders. 6 Thus, these studies support the notion that JON combined with RF results in the child experiencing excessive failure, especially in the classroom, which in turn leads to behavioral problems of a reactive nature. These findings, however, cannot explain why behavioral problems are found in preschool children with ID. 22 This information can be used to argue that a common factor, such as neurodevelopmental delay, contributes to the development of all these disorders.

Conclusions

Overall, the literature supports a strong relationship between oral language skills and subsequently developed reading and behaviour. This fact stems mainly from studies of children with JD as they enter school. The basis of the relationship between early oral language and later reading development is believed to be causal, with oral language skills being fundamental precursors to later successful reading. This influence of language on reading primarily includes two components of language ability - phonological processing and listening comprehension. Children with underdeveloped phonological processing skills are at risk of early decoding problems that can later lead to reading comprehension problems. Children with hearing comprehension problems are at risk of developing reading comprehension problems, even if they can decode words. A common characteristic of children with JD is that both aspects of language are impaired, and therefore the resulting reading problems affect both aspects of reading (decoding and comprehension). The basis of the relationship between spoken language and subsequent behavioral problems is less understood.

This fact stems mainly from studies of children with JD as they enter school. The basis of the relationship between early oral language and later reading development is believed to be causal, with oral language skills being fundamental precursors to later successful reading. This influence of language on reading primarily includes two components of language ability - phonological processing and listening comprehension. Children with underdeveloped phonological processing skills are at risk of early decoding problems that can later lead to reading comprehension problems. Children with hearing comprehension problems are at risk of developing reading comprehension problems, even if they can decode words. A common characteristic of children with JD is that both aspects of language are impaired, and therefore the resulting reading problems affect both aspects of reading (decoding and comprehension). The basis of the relationship between spoken language and subsequent behavioral problems is less understood. Behavioral problems can arise from oral and written communication needs in the classroom. Accordingly, communication failure serves as a stress factor, and behavioral problems are an inadequate response to this stress factor. On the other hand, oral and written language disorders may share an underlying etiology with behavioral problems.

Behavioral problems can arise from oral and written communication needs in the classroom. Accordingly, communication failure serves as a stress factor, and behavioral problems are an inadequate response to this stress factor. On the other hand, oral and written language disorders may share an underlying etiology with behavioral problems.

Recommendations

Evidence strongly suggests that a foundation of oral language competence is important for the successful achievement of academic and social competence. Children with poor language skills, who are therefore at risk of developing psychosocial and reading problems, can be successfully identified at school entry. Remedial techniques are available to enhance language development: in particular, there are numerous programs designed to support the development of phonological processing skills. Similarly, in elementary school, listening comprehension can be improved. These methods are aimed at consolidating language skills. In addition, remedial efforts should consider methods that help provide these children with an adapted and supportive educational environment and reduce potential stressors that can lead to inappropriate behaviour. In the future, research is needed to study the mechanisms that cause this complex of oral-speech, written and behavioral problems. Of particular relevance would be research conducted in the school setting and aimed at studying how children respond to communicative expectations and failures.

In addition, remedial efforts should consider methods that help provide these children with an adapted and supportive educational environment and reduce potential stressors that can lead to inappropriate behaviour. In the future, research is needed to study the mechanisms that cause this complex of oral-speech, written and behavioral problems. Of particular relevance would be research conducted in the school setting and aimed at studying how children respond to communicative expectations and failures.

Literature

- Snow CE, Burns MS, Griffin P, eds. Preventing reading difficulties in young children . Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1998.

- Beitchman JH, Nair R, Clegg M, Patel PG, Ferguson B, Pressman E, Smith A. Prevalence of speech and language disorders in 5-year-old kindergarten children in the Ottawa-Carleton region. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders 1986;51(2):98-110.

- Tomblin JB, Records NL, Buckwalter P, Zhang X, Smith E, O'Brien M.

Prevalence of specific language impairment in kindergarten children. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research 1997;40(6):1245-1260.

Prevalence of specific language impairment in kindergarten children. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research 1997;40(6):1245-1260. - Shaywitz SE, Shaywitz BA. Unlocking learning disabilities: The neurological basis. In: Cramer SC, Ellis W, eds. Learning disabilities: Lifelong issues . Baltimore, Md: P.H. Brooks Publishing; 1996:255-260.

- Commission on Emotional and Learning Disorders in Children. One million children: A national study of Canadian children with emotional and learning disorders . Toronto, Ontario: Leonard Crainford; 1970.

- Tomblin JB, Zhang X, Buckwalter P, Catts H. The association of reading disability, behavioral disorders, and language impairment among second-grade children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines 2000;41(4):473-482.

- Aram DM, Ekelman BL, Nation JE. Preschoolers with language disorders: 10 years later. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research 1984;27(2):232-244.

- Bishop DV, Adams C. A prospective study of the relationship between specific language impairment, phonological disorders and reading retardation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines 1990;31(7):1027-1050.

- Catts HW. The relationship between speech-language impairments and reading disabilities. J ournal of Speech & Hearing Research 1993;36(5):948-958.

- Silva PA, Williams S, McGee R. A longitudinal study of children with developmental language delay at age 3: Later intelligence, reading and behavior problems. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 1987;29(5):630-640.

- Stark RE, Bernstein LE, Condino R, Bender M, Tallal P, Catts H. 4-year follow-up-study of language impaired children. Annals of Dyslexia 1984;34:49-68.

- Stark RE, Tallal P. Language, speech, and reading disorders in children: neuropsychological studies . Boston, Mass: Little, Brown and Co.

; 1988.

; 1988. - Catts HW, Fey ME, Zhang XY, Tomblin JB. Estimating the risk of future reading difficulties in kindergarten children: A research-based model and its clinical implementation. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools 2001;32(1):38-50.

- Catts HW, Fey ME, Zhang X, Tomblin JB. Language basis of reading and reading disabilities: Evidence from a longitudinal investigation. Scientific Studies of Reading 1999;3(4):331-362.

- Beitchman JH, Hood J, Inglis A. Psychiatric risk in children with speech and language disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 1990;18(3):283-296.

- Beitchman JH, Hood J, Rochon J, Peterson M. Empirical classification of speech/language impairment in children: II. behavioral characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 1989;28(1):118-123.

- Beitchman JH, Tuckett M, Batth S. Language delay and hyperactivity in preschoolers: Evidence for a distinct subgroup of hyperactives.

Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 1987;32(8):683-687.

Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 1987;32(8):683-687. - Beitchman JH, Brownlie EB, Wilson B. Linguistic impairment and psychiatric disorder: pathways to outcome. In: Beitchman JH, Cohen NJ, Konstantareas M, Tannock R, eds. Language, learning, and behavior disorders: Developmental, biological, and clinical perspectives . New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1996:493-514.

- Stevenson J, Richman N, Graham PJ. Behavior problems and language abilities at three years and behavioral deviance at eight years. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines 1985;26(2):215-230.

- Benasich AA, Curtiss S, Tallal P. Language, learning, and behavioral disturbances in childhood: A longitudinal perspective. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 1993;32(3):585-594.

- Redmond SM, Rice ML. The socioemotional behaviors of children with SLI: Social adaptation or social deviance? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research 1998;41(3):688-689.

g. cat, hat, mat, bat)

g. cat, hat, mat, bat) g. cat – hat – big)

g. cat – hat – big) g. Say ‘cupcake’. Take away ‘cup’ and what is left? cake)

g. Say ‘cupcake’. Take away ‘cup’ and what is left? cake)