Why teach phonics

Phonics (emergent literacy)

Phonics is the ability to map sounds onto letters (sound-letter knowledge).

Children start to develop this early decoding ability in early childhood.

The ability to decode words is strongly reliant on children having strong phonological awareness skills, which are a gateway into letter-sound knowledge.

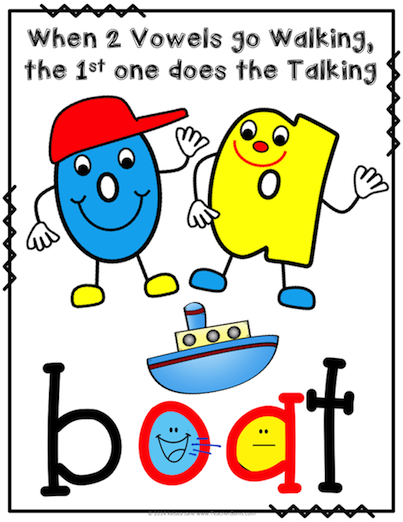

Phonics knowledge allows children to understand the link between sounds (phonemes) and letter patterns (graphemes).

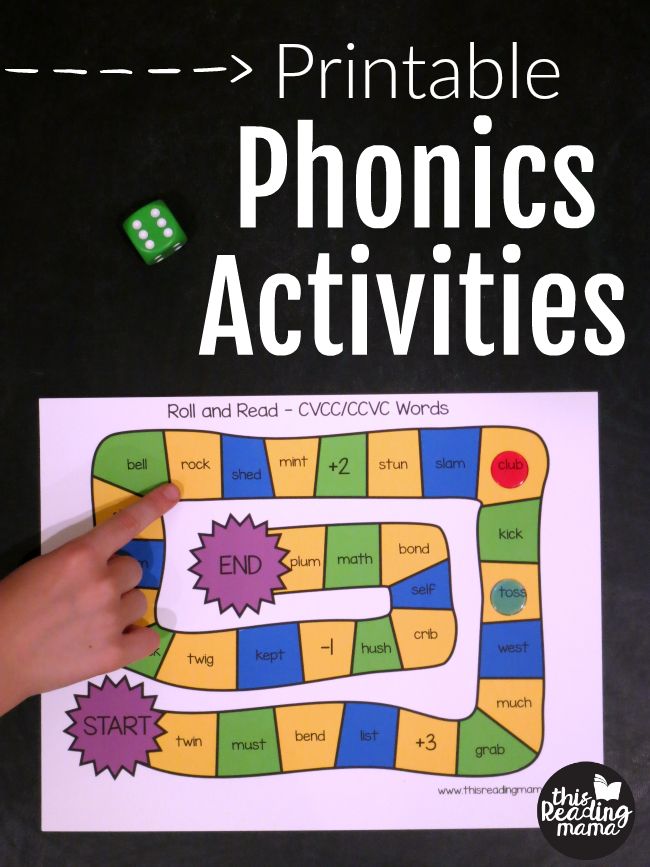

Phonics can be introduced through emergent literacy experiences.

In early childhood children will typically develop an emerging awareness of phonics, and that other aspects of emergent literacy and oral language are the main foci.

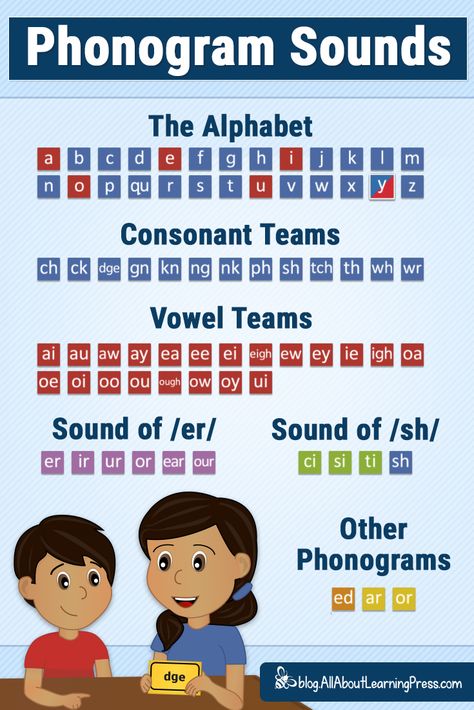

English is an alphabetic language as it has 26 letters and 44 speech sounds. Combinations of these letters are used to represent all the different speech sounds (phonemes).

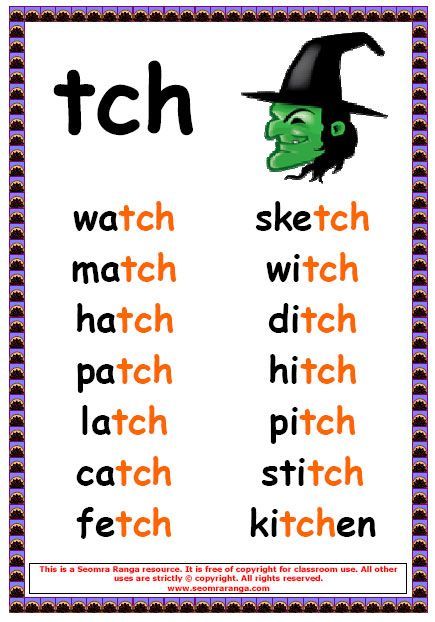

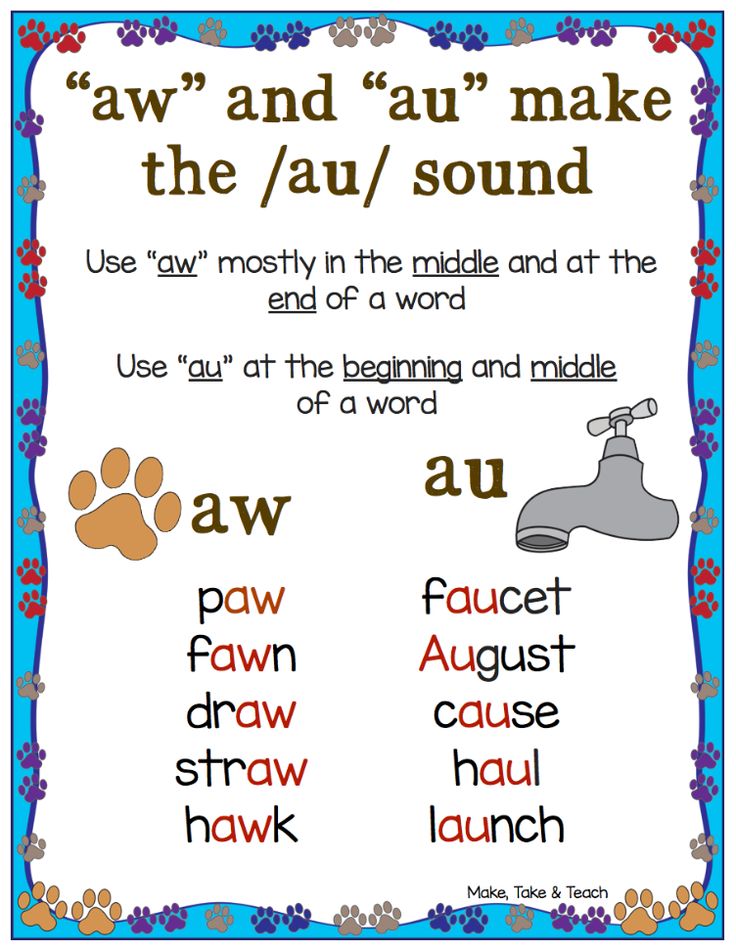

In English, sound-letter patterns can be either single letters (graph), two letters (digraph), three (trigraph), or four letters (quadgraph) to spell these sounds:

| Sound-Letter pattern | Grapheme | Example grapheme | Example word |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 letter making 1 sound | graph | b a | rub cat |

| 2 letters making 1 sound | digraph | ch oy | chop soy |

| 3 letters making 1 sound | trigraph | dge ere | ridge here |

| 4 letters making 1 sound | quadgraph | ough | through though |

Learn more about the 44 sounds of English:

- 44 sounds of English (docx - 224.

96kb)

- 44 sounds of English (pdf - 546.72kb)

- Phonological awareness

Early phonics knowledge is the key to starting to decode written words. Children can use phonics knowledge to “sound out” words.

[Children] learn to recognise how sounds are represented alphabetically and identify some letter sounds, symbols, characters and signs.

VEYLDF (2016)

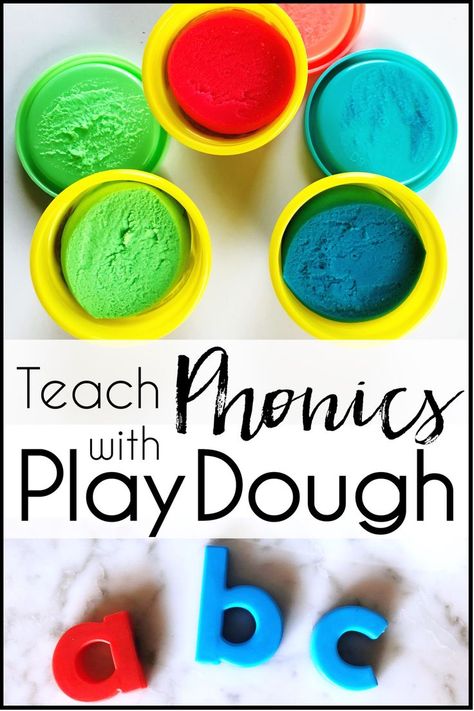

Phonics is essential for children to become successful readers and spellers/writers in the early years of schooling and beyond. Introductions to phonics through engaging learning experiences can start from the ages of 3 and 4.

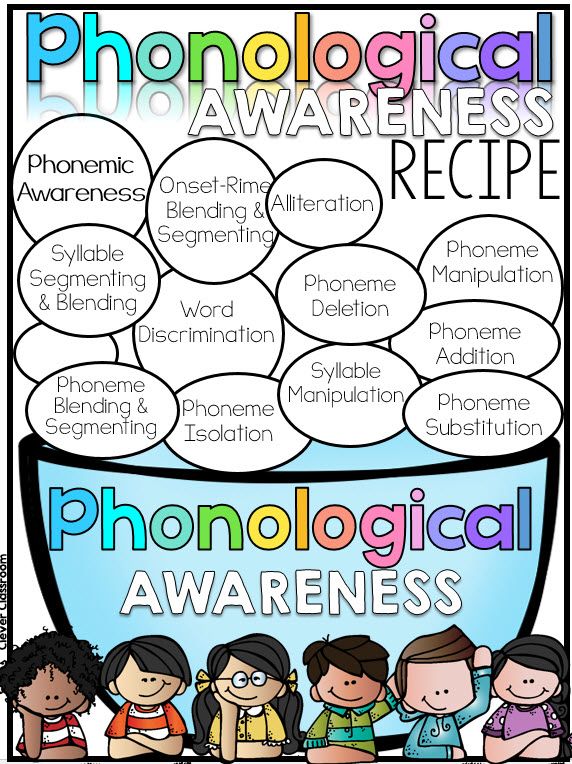

Phonological awareness is the awareness of speech sounds, syllables, and rhymes. Phonemic awareness is the phoneme (“speech sound”) part of this skill, and involves children blending, segmenting, and playing with sounds to make new words.

Phonics is the mapping of speech sounds (phonemes) to letter patterns (graphemes).

Phonological Awareness and Phonics are therefore not the same. However, these literacy foci overlap quite a lot, especially in the early years of primary school.

The following ages and stages are a guide that reflects broad developmental norms, but doesn’t limit the expectations of every child (see VEYLDF Practice Principle: High expectations for every child). It is always important to understand children’s learning and development as a continuum of growth, irrespective of their age.

Early communicators (birth - 18 months):

- developing interest in books and print

Early language users (12 - 36 months):

- interested in print

- pretending to read

- enjoying storybook reading

- interested in syllables, rhymes, sounds

- experimenting with mark making and drawing

Language and emergent literacy learners (30 - 60 months):

- growing awareness of words and print (metalinguistic skills)

- playing with sounds and language

- recognition of:

- familiar words by recognising only a few letters

- printed material

- trademarks

- own name

- scanning of material from left to right

- growing letter-sound (phonics) awareness

- starting to experiment with writing and spelling.

Early writing and spelling experiences are a great way to introduce phonics.

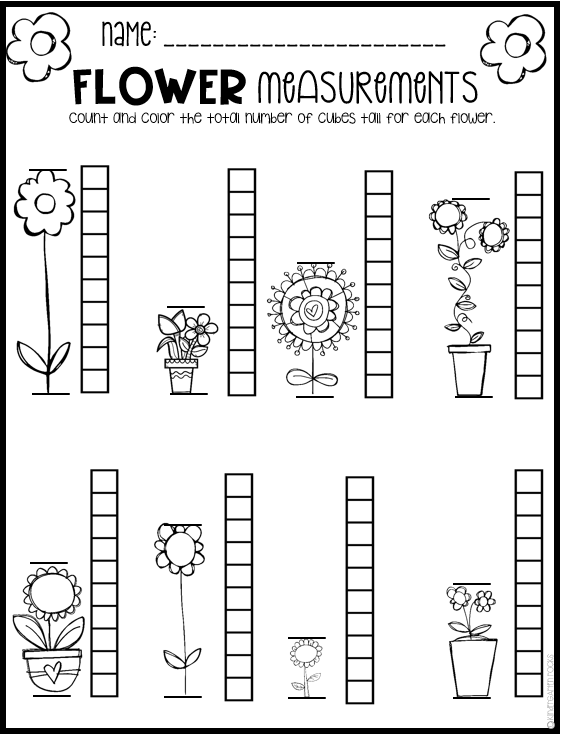

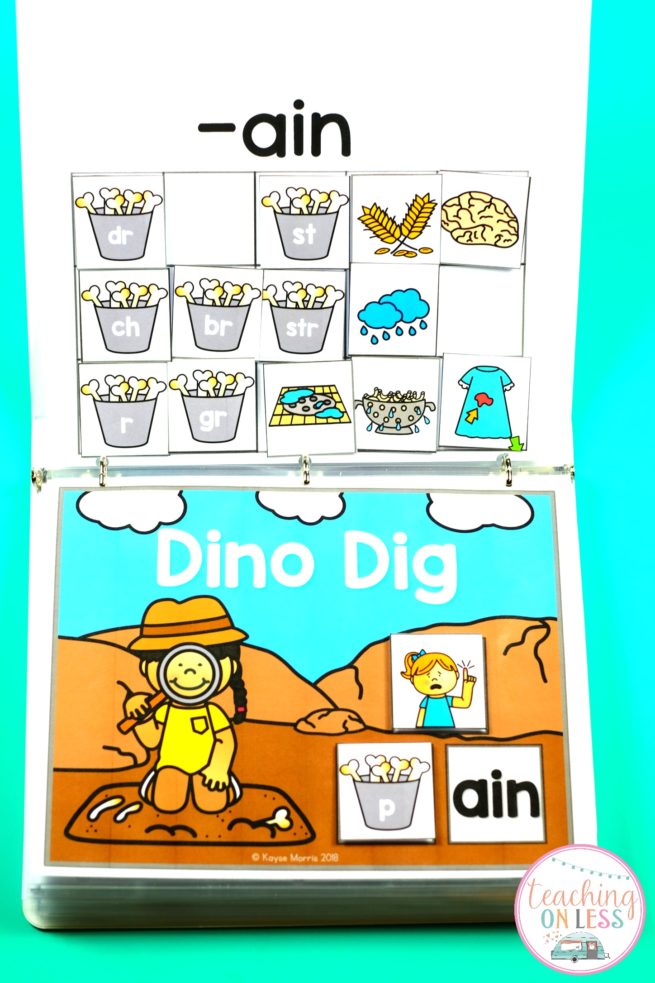

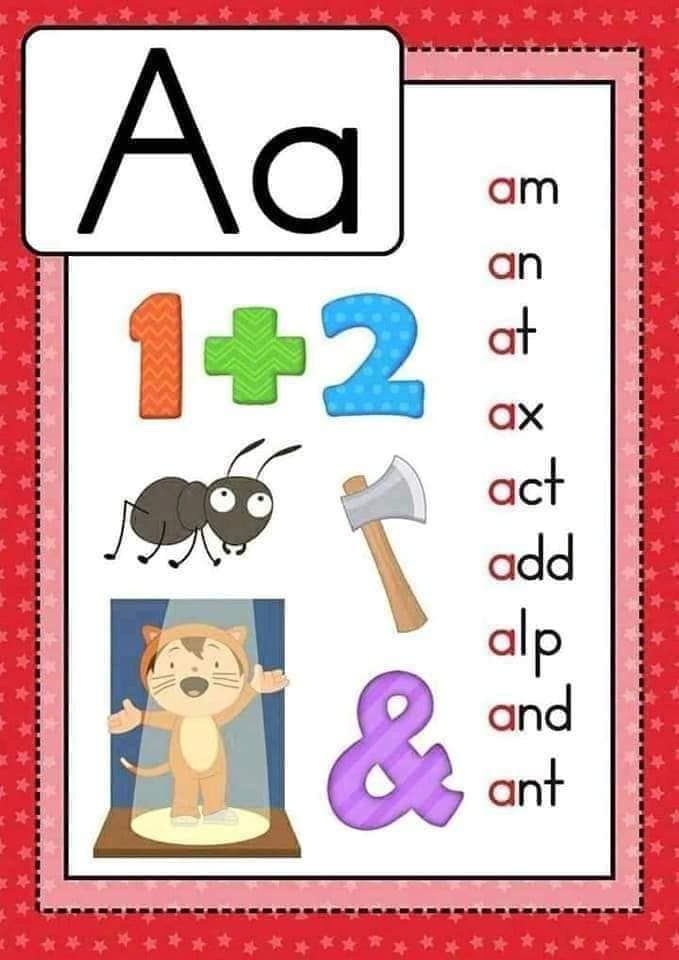

For introductions to letter-sound patterns, it is best to begin with the simplest graphemes.You can introduce these through environmental print, shared book reading, shared drawing and writing experiences, and letter games.

These introductory phonics patterns (graphemes) are the first building blocks of simple words.

Using just these simple patterns, educators and children can create 100s of words, all using these short vowel sounds:

- short /a/ — for example cat dab man tap bag

- short /e/ — for example met fed wet men get

- short /i/ — for example kit lid nip fit fix quit

- short /o/ — for example cot pod got top

- short /u/ — for example cut dub tug bun

You can download this overview of phonics patterns to see the scope of sound-letter patterns from simple to complex.

- Phonics patterns (docx - 212.49kb)

- Phonics patterns (pdf - 535.

06kb)

06kb)

Irregular words

Some words do not follow the sound-letter (phonics) rules. These are known as irregular words.

- regular words are words that can be decoded using knowledge of phonics patterns (for example get, well, which, before)

- irregular words are words that do not conform to phonics patterns (do, said, could, yacht, doubt).

Sometimes you will come across irregular words in emergent literacy experiences. For these words sounding out won’t really work, so you can read (or spell) the whole word for children.

Look at the more complex phonics patterns to know which words have intermediate/advanced patterns, and which are irregular.

- Phonics patterns (docx - 212.49kb)

- Phonics patterns (pdf - 535.06kb)

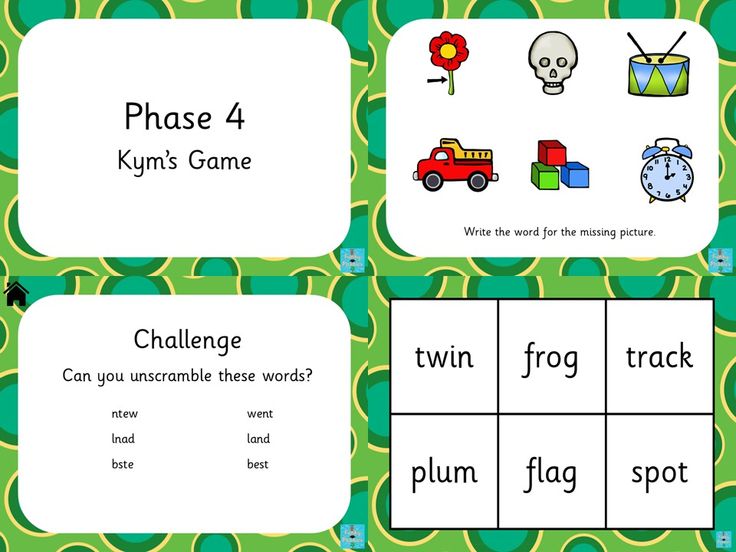

Blends vs. digraphs/trigraphs

Consonant blends are combinations of consonants that appear before or after a vowel (for example plug, splat, grump, spilt).

Sometimes blends can be confused with digraphs (for example rich, shut) and trigraphs (r i dge).

If you can break the sounds apart then you are hearing a blend:

- for example split —> /s/ /p/ /l/ /i/ /t/

- for example pink —> /p/ /i/ /n/ /k/

If the sounds will not break apart then it must be a digraph, trigraph or quadgraph:

- ship —> /sh/ /i/ /p/

- itch —> /i/ /tch/

Introducing phonics is a key to early reading and spelling success.

An awareness of the links between speech sounds (phonemes) and letter patterns (graphemes) is one of the essential parts within the Four Resources model of reading (Luke & Freebody, 1999).

When beginning to read, children need to "break the code" of written language (decoding). When spelling they need to “use the code” to turn their speech into written words (encoding).

Strong evidence demonstrates the importance of phonics for literacy teaching, particularly in the early years of Primary. When educators introduce children to sound-letter patterns through engaging emergent literacy experiences, it makes the transition to early reading and spelling much smoother.

The evidence for this includes the synthesis of research literature in the Australian National Inquiry into the Teaching of Reading (Rowe et al., 2005). In this review, they found that numerous studies support the effectiveness of phonics for early reading skills. In particular, teaching practices in early Primary school that included an explicit focus on the sound-letter patterns (graphemes), and applied these to reading and writing experiences were most effective.

These findings are also replicated in Hattie's (2009) Visible Learning, the US National Reading Panel (2000) and the UK Rose Review (2006).

Phonics: Getting started downloadable for:

- Early communicators and early language users

- Language and emergent literacy learners

- listen and respond to sounds and patterns in speech, stories and rhymes in context

- begin to understand key literacy and numeracy concepts and processes, such as the sounds of language, letter–sound relationships, concepts of print and the ways that texts are structured.

- begin to recognise patterns and relationships and the connections between them.

- develop an understanding that symbols are a powerful means of communication and that ideas, thoughts and concepts can be represented through them

- begin to be aware of the relationships between oral, written and visual representations

- listen and respond to sounds and patterns in speech, stories and rhyme.

- Phonological awareness through rhyme and stories

Victorian early years learning and development framework (VEYLDF, 2016)

Outcome 5: communication

Children engage with a range of texts and get meaning from these texts:

Children express ideas and make meaning using a range of media:

Children begin to understand how symbols and pattern systems work:

For age groups: early language users (12 - 36 months):

For age groups: language and emergent literacy learners (30 - 60 months) :

- Bee bee bumble bee

- The sounds in my name

- Clay letters: fine motor and phonics

- Phonological awareness through rhyme and stories

- Phonological awareness

- Speech sounds

Hattie, J. (2009), Visible Learning; a synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement, Routledge, London.

(2009), Visible Learning; a synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement, Routledge, London.

Luke, A., & Freebody, P. (1999). Further notes on the four resources model. Reading Online. Available from:

NRP, National Reading Panel (2000a). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Rowe, Ken and National Inquiry into the Teaching of Literacy (Australia) (2005) Teaching reading. Canberra, Australia. Available from:

"Rose Review". Department for Education, 2010, Importance of teaching: The Schools White Paper Executive Summary, TSO, London, England. Available from the UK Government website

Victorian State Government Department of Education and Training (2016, Victorian Early Years Learning and Development Framework (2016). Retrieved 3 March 2018,

Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority (2016) Illustrative maps from the VEYLDF to the Victorian Curriculum F–10. Retrieved 3 March 2018,

Retrieved 3 March 2018,

what is phonics and why is it important?

The efficacy of phonics as a method of teaching has been debated for several decades, and has recently come back to the forefront of public debate.

This time, the focus is on the phonics check – a screening tool designed to identify early readers who may be in need of intervention, and provide some indication of how successful current phonics teaching methods are. The UK has been using the Phonics Screening Check (PSC) since 2012, and now there is a push to implement a trial of the same check in Australia. This has raised some concerns.

So what’s the fuss about phonics?

What is phonics?

Scientific studies have repeatedly found that explicit systematic phonics instruction is the most effective way to teach children how to read. Without it, some children will end up having serious reading difficulties. But what is explicit systematic phonics? Let’s break this term down.

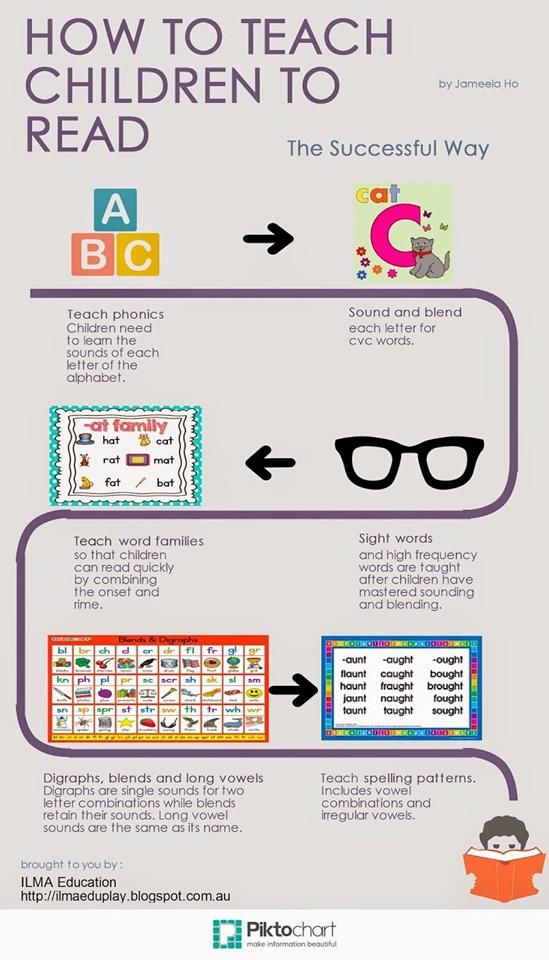

Phonics – teaching children the sounds made by individual letter or letter groups (for example, the letter “c” makes a k sound), and teaching children how to merge separate sounds together to make it one word (for example, blending the sounds k, a, t makes CAT). This type of phonics teaching is often referred to as “synthetic phonics”.

This type of phonics teaching is often referred to as “synthetic phonics”.

Explicit – directly teaching children the specific associations between letters and sounds, rather than expecting them to gain this knowledge indirectly.

Systematic – English has a complicated spelling system. It is important to teach letter sound mappings in a systematic way, beginning with simple letter sound rules and then moving onto more complex associations.

The term “phonics” has been used quite loosely by several reading programs, with some straying from these fundamental principles.

For example, some programs, such as Embedded Phonics, teach phonics by asking children to guess unfamiliar words using cues, such as the meaning of a word gleaned from sentence context.

Other programs ask children to look at words (for example, pig, page, pen all start with the same sound) and learn letter-sound rules by analysing or making comparisons between those words (analogy or analytical phonics).

These programs are not as effective as those focusing on letter-sound knowledge taught in an explicit and systematic fashion.

Why is it important?

Phonics instruction teaches children how to decode letters into their respective sounds, a skill that is essential for them to read unfamiliar words by themselves.

Keep in mind that most words are in fact unfamiliar to early readers in print, even if they have spoken knowledge of the word. Having letter-sound knowledge will allow children to make the link between the unfamiliar print words to their spoken knowledge.

Another aspect that is rarely discussed is that the letter-sound decoding process itself is a learning mechanism. For example, make a mental note of how you feel when reading the following words:

Wingardium Leviosa

When you first read these words, you probably used your letter-sound knowledge, which involved two important processing stages:

1) It helped you produce the correct sound of an unfamiliar print word. If you’re a Harry Potter fan, the pronunciation also probably lit up connections to the meaning of the word.

If you’re a Harry Potter fan, the pronunciation also probably lit up connections to the meaning of the word.

2) It drew your attention to the details and the combination of the letters of the word.

These two steps then function as a learning mechanism, allowing you to recognise the previously unfamiliar word quicker the next time around (go back to read the words again and see how you feel about them now).

This transition from slowly sounding out a word, to rapidly recognising it, is what we call “learning to read by sight”. Every reader must make this transition to read fluently.

It is true that there are many English words, such as yacht and isle that do not follow typical letter-sound rules. Even then, research has shown that children can still learn these words successfully by decoding some parts of the word (y … t for yacht), with help from spoken vocabulary knowledge to facilitate the learning.

Phonics is important not only because this knowledge allows children to read on their own, but it is also a learning mechanism that builds up a good print word dictionary that can be quickly accessed.

Will it really improve reading?

Recent National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy (NAPLAN) results have shown no improvement in reading and writing skills despite much government funding.

The Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) results demonstrated a steady decline in children’s reading ability in Australia since 2000.

So will more effective phonics instruction really help to improve these results?

Of course, reading effectively (whether to learn or for pleasure) is not just about phonics or having a decent store of single words.

Functional reading requires several other skills such as good vocabulary, the ability to extract inferences, and synthesise and hold information in memory across several sentences. But if your single word reading is not efficient, comprehension is going to be dramatically affected.

If we use building a house as an analogy, understanding text is the complete home; single word reading ability is the structural frame of the house, and phonics is the foundation of that frame.

Effective phonics instruction is important because letter-sound knowledge is the foundation needed to build up reading and writing abilities.

The phonics screening check will indicate whether children have gained the necessary skills. If not, schools need to review current methods of teaching and implement methods that stick with evidence-based principles of explicit, systematic phonics teaching.

| Semiotics, semantics and speech Speech Conquirement Semiotics school Semiotics Semantics Semantics theory

Symbols and their value Interpretation of the information 9000, EXEGUSE 9000 9000 Symbols - the essence of texts

The role of metaphors

| Go to home Registration

Fundamentals of Linguistics:

| Lexicology Study Three types of analysis Semantic groups Literary heritage

Returning to Pushkin Pushkin's Thought The unusually receptive Proteus Friendship with Chaadaev Generation of noble intelligentsia In the Demutov tavern The sun of our poetry At the zenith of glory Rejection of the poet Comprehension of Pushkin The beginning of the beginnings The XIX century Spiritual life was born in Russia 9006 9006 Russia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Why do primary school students need phonetics

Is phonetics necessary in elementary school?

– What do we know about speech sounds?

– They can be vowels and consonants!… Consonants can be hard and soft!… There are 10 vowels and 21 consonants!

- Nothing like that!

– How is it? I considered! Mom and I counted!

My advanced student is sincerely perplexed. As a result, he will remember that there are actually 6 vowels, but he will not think about the fact that hard [m] and soft [m '] are different sounds.

Parents often ask why they spend so much effort on characterizing sounds. And the type of transcription simply drives them into a stupor. However, here I understand them - an entry like [in l’isu rad’ilas’ y’olach’ka] in a second-grader’s notebook, really, how can I put it mildly? - disturbing.

So is it really necessary to spend so much time and effort on characterizing sounds? I will try to discuss this topic.

When a child learns to read , I don’t see the point in explaining to him for a long and confusing time that the letter Yo does two jobs - it means the sound Oh, while softening the previous consonant (maple) and means two sounds - yo (tree, spear). I am for syllabic learning to read (according to the Zaitsev method), where the child immediately learns syllables - “hard” and “soft.

But if a child learns to read “alphabetically” (that is, he first learns the letters, then how they merge), it is difficult to do without sound analysis. I had a student, a very smart boy, who wrote his name - "LONYA". At the same time, he read well, in whole words. The child had a synthetic way of perceiving information, he did not analyze words when reading and did not remember how they are spelled. Probably, such mistakes would not have happened if he had learned to read in a syllabic way. But in the current situation, we needed a conversation about which letter does which work.

At the same time, he read well, in whole words. The child had a synthetic way of perceiving information, he did not analyze words when reading and did not remember how they are spelled. Probably, such mistakes would not have happened if he had learned to read in a syllabic way. But in the current situation, we needed a conversation about which letter does which work.

To understand why it is necessary to write FIR-TREE AND RODS (and not YOLKA and ROTS), the child needs to understand 1) that the letter HAS A JOB - TO DESIGNATE A SOUND; 2) that there are vowels that can denote two sounds in certain positions, and there are combinations of sounds that are denoted by one letter.

The ability to HEAR and characterize sounds becomes important when the child begins to write. Here it turns out that in some cases we HEAR exactly what letter to write (i.e., scientifically speaking, the sound is in a STRONG POSITION), and in other cases (when the sound is in a WEAK POSITION), we hear it unclear and doubtful. When in doubt, you need to check the spelling (for example, put an unstressed vowel under stress).

When in doubt, you need to check the spelling (for example, put an unstressed vowel under stress).

In many programs (including the traditional, classical ones, according to which the grandmothers of today's schoolchildren studied), it is spell checking that spends the most time and effort. But in order to check the spelling in the words “head”, “mug”, “chill”, you need to 1) HEAR, an erroneous place and 2) apply the rule. In the first case, change the word by putting the vowel under stress (heads) or pick up a related word (head), in the second, change the word or choose a related one so that after the double consonant there is a vowel (circle) or sonorous (chill). That is, in order to use these simple rules, the child must know the concepts of vowel, consonant, double consonant, sonorant. When asked by a friend why her granddaughter in the first grade needed the concept of a sonorous sound, I answered with the formulation of such a rule.

There are other spelling rules that use the characteristics of sounds: spelling b after HIS, O-E after HIS, etc.

However, the question remains whether it will be convenient for the child to use spelling rules, whether he will have such a need at all. My student Stasik wrote almost without errors, but in Russian he never had a mark above four. In middle and high school, my principled friend, a linguist, regularly gave him an A. Stasik checked the unstressed vowel in the words “sawed with a saw” with the word “saw” (where this vowel is also unstressed). He just knew how to spell this root and could not even understand what we want from him.

There is another argument in favor of sound analysis. The ability to hear and analyze sounds is a direct way to correct the speech therapy problems that many children face today. The experience of the TRIZ teacher, speech therapist I.N. Krokhina shows that awakening research interest in speech sounds effectively develops the ability to hear and pronounce these sounds correctly. See how Inna Nikolaevna's students analyze sounds and with what pleasure they do it.

Well, opponents will object, "speech therapy" children may have no other choice. But is it necessary to do this if the child has no speech therapy problems? Let's open this question, dividing it into parts and try to find answers.

- Is it possible to teach reading and writing without delving deeply into which letter does which work? - It is possible, Zaitsev's cubes are an example of this.

- Is it possible to teach to write correctly without memorizing the rules? There is an opinion that this is possible. For example, by the method of spelling reading (see the description of the methodology of P.S. Totsky, for example, here).

- Are there other ways to learn good writing? And it is. Famous psychologist L.A. Yasyukova, who has worked with hearing-impaired children for many years and successfully taught them to read and write, argues that sound analysis in the early stages of learning is harmful. We write not as we hear, but as we see. Until the 80s, training was aimed at mastering the IMAGE OF THE WORD and the RULES by which words are written.

Children began to write by ear (and, accordingly, check spelling) only in the third grade. There were a lot more smart people back then. A very categorical opinion of Lyudmila Appolonovna on this issue is in the article “Pedagogy of illiteracy” (“School Technologies” No. 2-2011).

Children began to write by ear (and, accordingly, check spelling) only in the third grade. There were a lot more smart people back then. A very categorical opinion of Lyudmila Appolonovna on this issue is in the article “Pedagogy of illiteracy” (“School Technologies” No. 2-2011).

I think that now parents are completely confused about how to teach a child in our time, and they are waiting for some kind of productive advice. “Be afraid of the one who says: “I know how to do it!”, wrote the poet Alexander Galich, and, in my opinion, he was right. I will not give unambiguous advice, but I will describe my vision of the situation.

- Analyzing speech sounds is useful if children learn to HEAR and LISTEN to them. This can be successfully done without reference to letters and it is better to start at preschool age. The situation when a child analyzes sounds by transcription ([m '] is soft, because there is such a badge) does not seem useful to me. The ability to hear and analyze the sounds of speech is necessary for “speech therapy” children.

For many people, this skill helps to check spelling and thereby avoid mistakes. Many - but not all, the story of my Stasik is an example of this.

For many people, this skill helps to check spelling and thereby avoid mistakes. Many - but not all, the story of my Stasik is an example of this. - The characterization of sounds is needed already because many rules of the Russian language are based on it. By itself, the ability to hear and analyze the sounds of speech is unlikely to interfere with literate writing (although it does not always help it). Based on the experience of P.S. Totsky, it can be argued that it is possible to teach literate writing without rules. But to pass the exams without knowing the rules today will not work.

- A well-structured study of sounds develops an interest in the structure of the language and, in addition, allows the child to be taught research activities, which, in my opinion, is necessary for modern children.

- If we want children to memorize images of words, it is logical to teach them to work with word parts - morphemes. If the child knows that the root “forest” is about something related to the forest, and the root “fox” is about something related to the fox, he does not really need to check the unstressed vowel with an accent, he will correctly write all the words with the same root by memory.

Similarly, if he distinguishes between the function of the prefixes pra- and pro- (one indicates kinship - great-grandmother, great-granddaughter, the other has other meanings), he will also make the right choice. People who reason like this rarely test an unstressed vowel with an accent. Working with morphemes is also an excellent field for developing research skills.

Similarly, if he distinguishes between the function of the prefixes pra- and pro- (one indicates kinship - great-grandmother, great-granddaughter, the other has other meanings), he will also make the right choice. People who reason like this rarely test an unstressed vowel with an accent. Working with morphemes is also an excellent field for developing research skills. - There are different ways to become good at writing. Ideally, you need to give your child the tools that will allow him to choose the most convenient path for him. This approach is implemented, for example, in the textbooks of O.L. Soboleva. The approach is close to me, but personally for me and my colleagues in these textbooks, it is precisely the research component that is missing.

- Language develops, technologies develop in parallel. I'm afraid it's hard for us today to imagine how our children will work with information 10 years from now. Therefore, I try to teach them whenever possible so that they UNDERSTAND how the language works.

What for? Let's try to figure it out.

What for? Let's try to figure it out.  Phonetically, classes with schoolchildren are held in ordinary classrooms. But there are also specialized institutions with equipped language classes. A sufficient amount of educational and methodological literature on practical phonetics for children has been published: correcting articulation is important precisely in childhood.

Phonetically, classes with schoolchildren are held in ordinary classrooms. But there are also specialized institutions with equipped language classes. A sufficient amount of educational and methodological literature on practical phonetics for children has been published: correcting articulation is important precisely in childhood.