Alphabetic principle stages

The Alphabetic Principle: From Phonological Awareness to Reading Words

What Is The Alphabetic Principle?

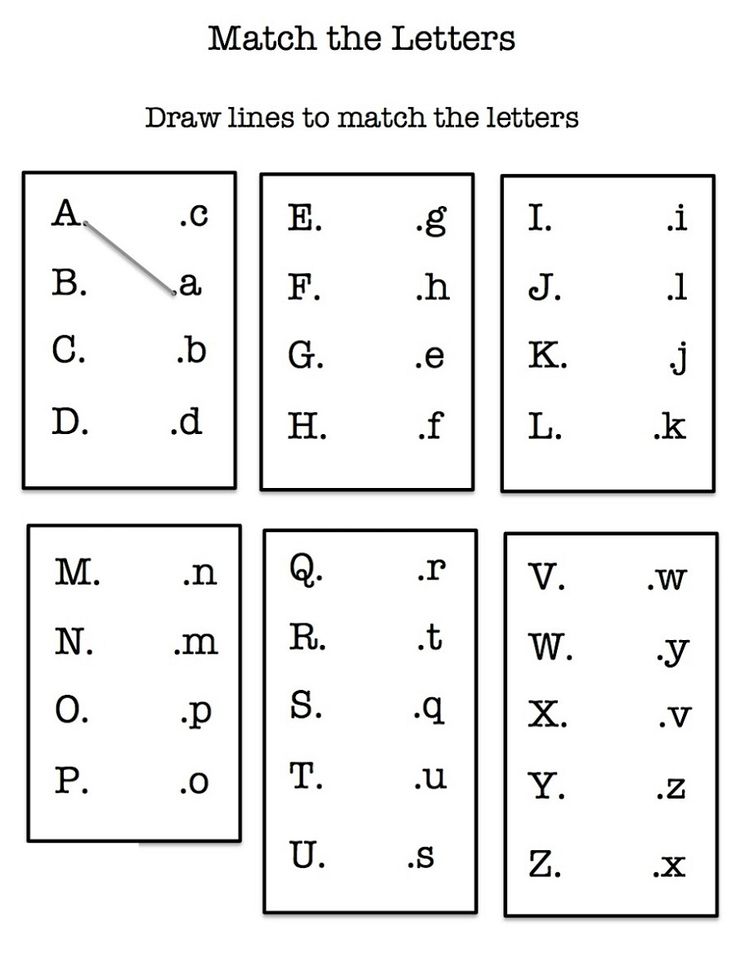

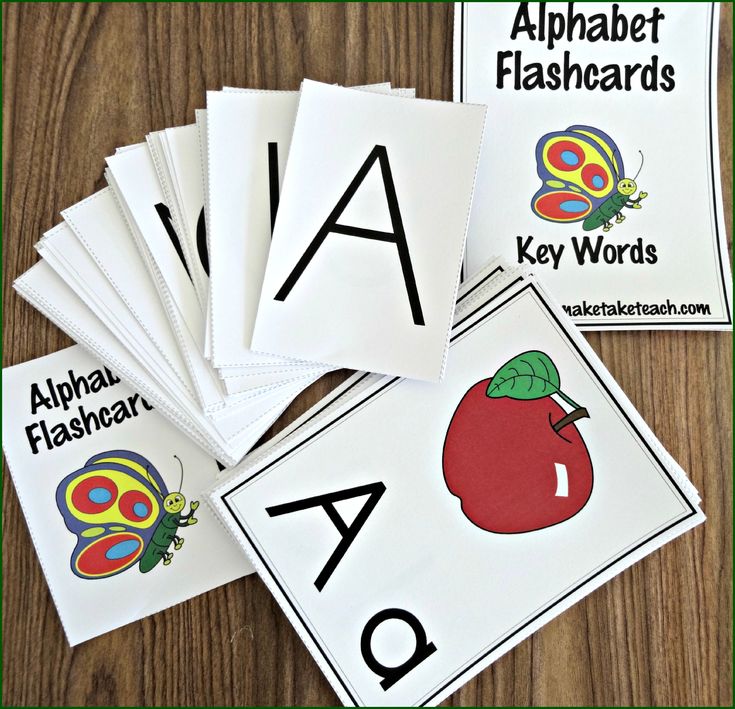

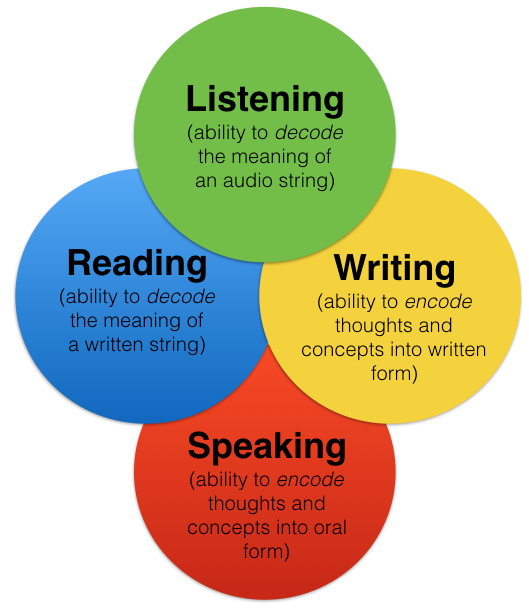

Connecting letters with their sounds to read and write is called the “alphabetic principle.” For example, a child who knows that the written letter “m” makes the /mmm/ sound is demonstrating the alphabetic principle.

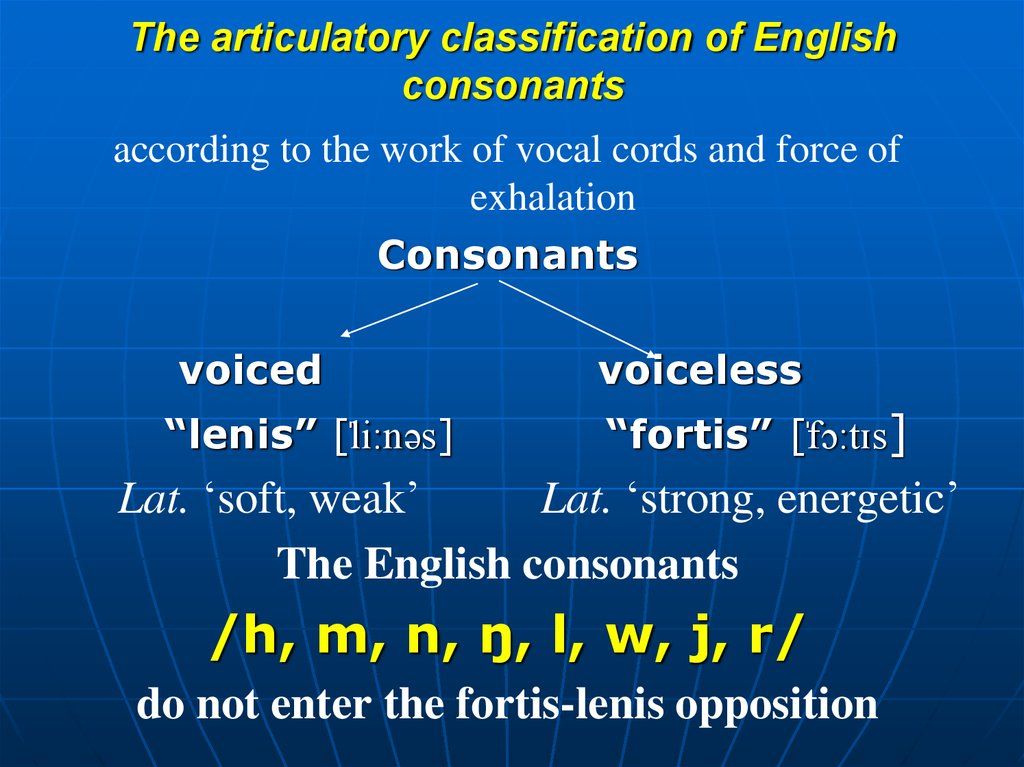

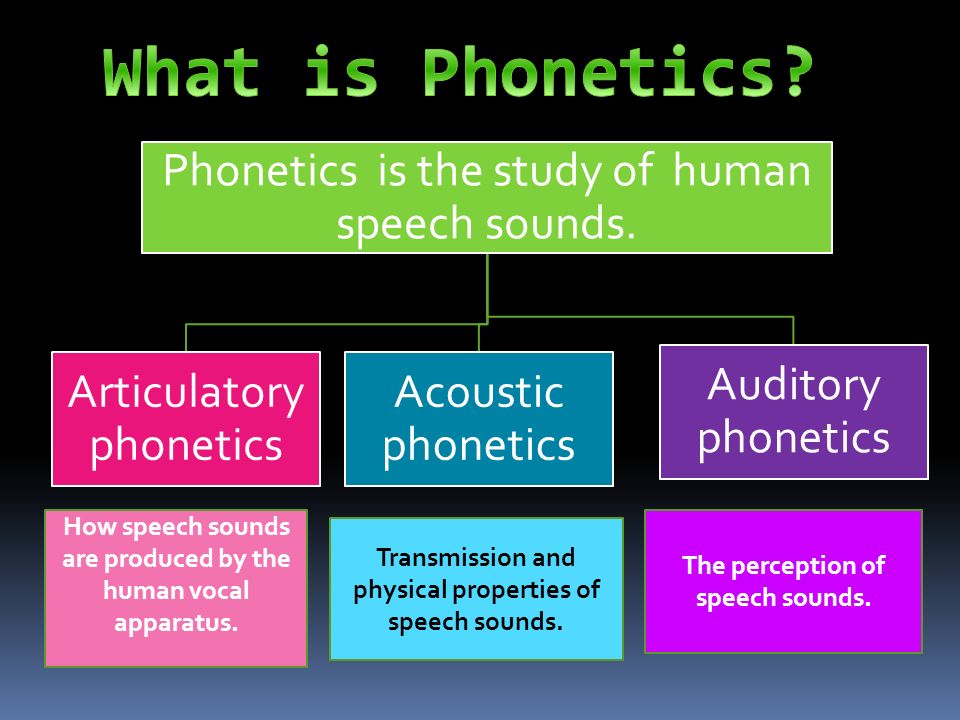

Letters in words tell us how to correctly “sound out” (i.e., read) and write words. To master the alphabetic principle, readers must have phonological awareness skills and be able to recognize individual sounds in spoken words. Learning to read and write becomes easier when sounds associated with letters are recognized automatically.

The alphabetic principle has two parts:

- Alphabetic understanding is knowing that words are made up of letters that represent the sounds of speech.

- Phonological recoding is knowing how to translate the letters in printed words into the sounds they make to read and pronounce the words accurately.

The alphabetic principle is critical in reading and understanding the meaning of text. In typical reading development, children learn to use the alphabetic principle fluently and automatically. This allows them to focus their attention on understanding the meaning of the text, which is the primary purpose of reading.

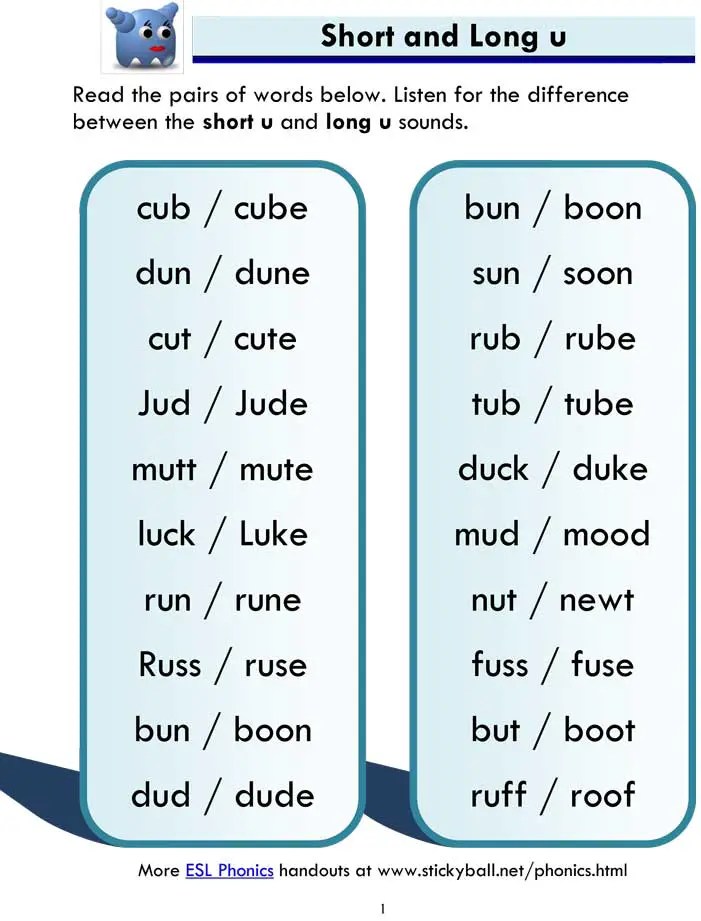

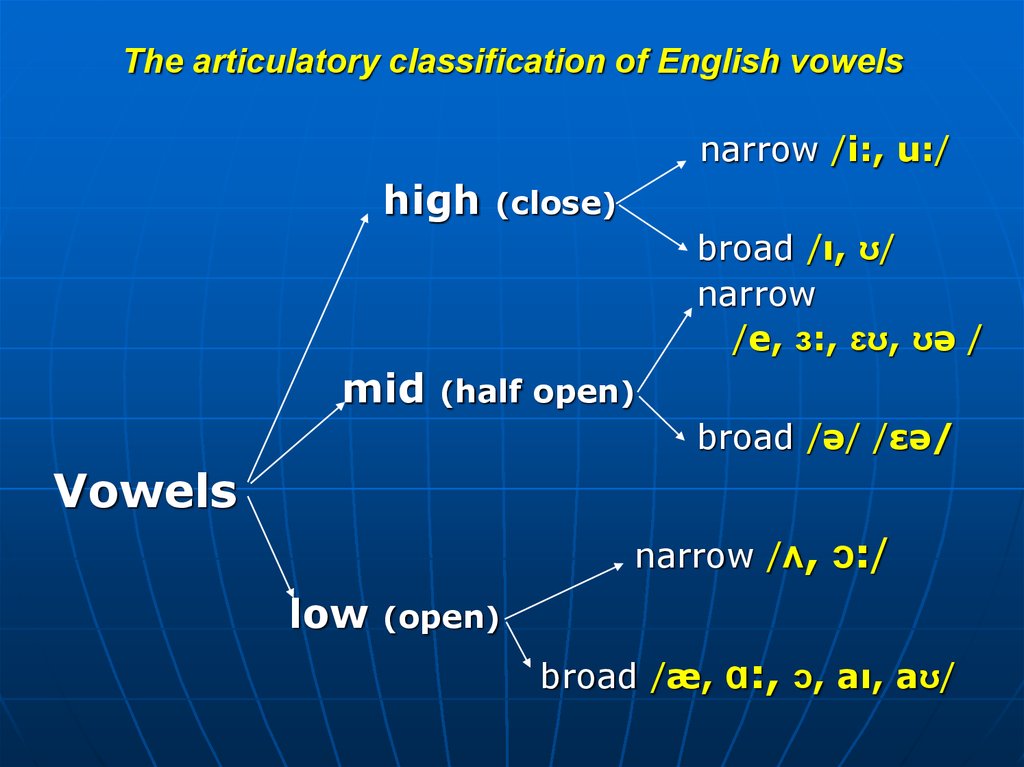

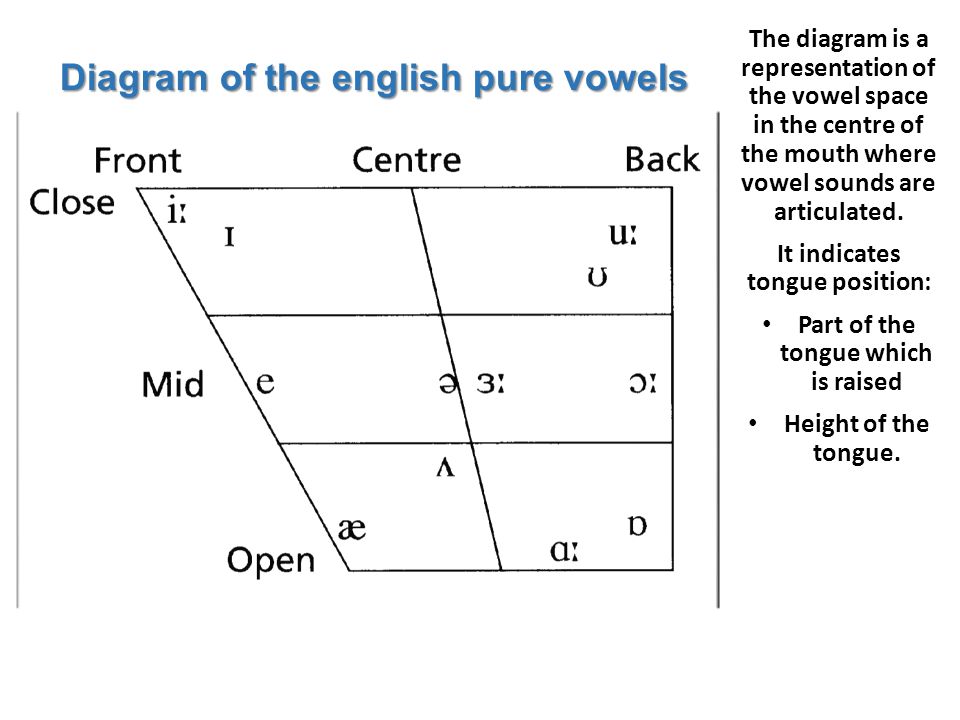

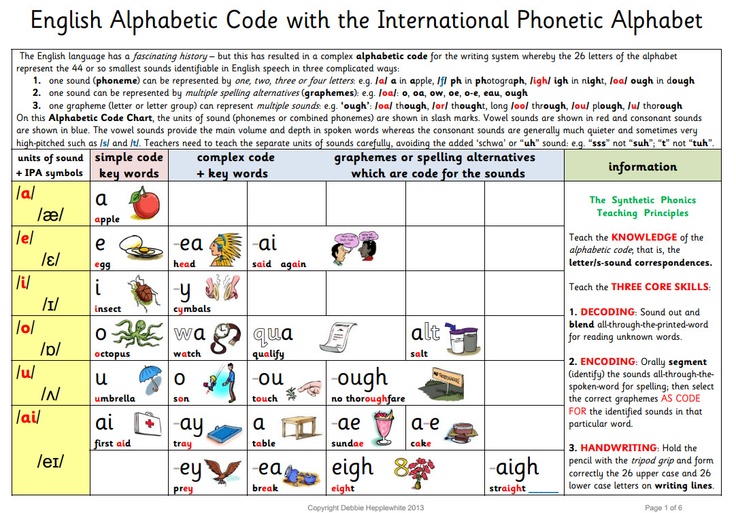

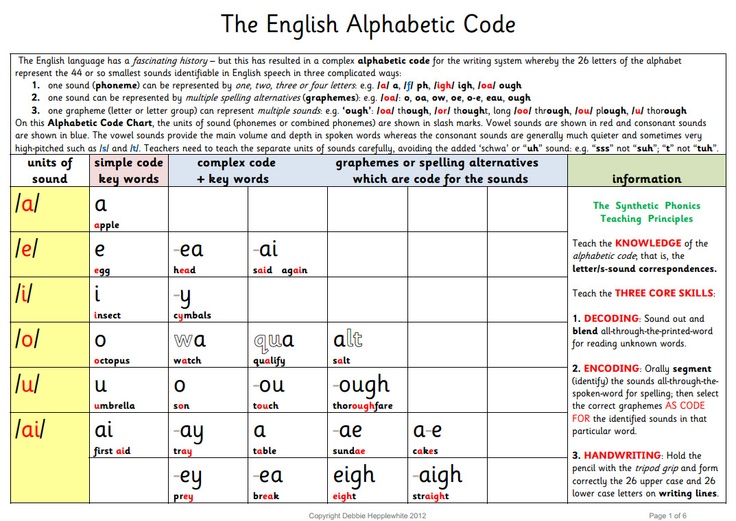

Learning and applying the alphabetic principle takes time and is difficult for most children. There are many letters to learn the sounds of, and there are many ways to arrange the letters to produce the vast number of different words used in print. Also, in English, the same letter can represent more than one sound, depending on the word (e.g., the /a/ sounds are different in the words “mat” and “mate”). In Spanish, by contrast, which also includes the vowel “a” in its alphabet, the /a/ sound is always pronounced the same way (e.g., the /a/ in “casa”) regardless what word it is in.

Irregular Words

Some words, called irregular words, cannot be read accurately using the alphabetic principle to “sound them out” (e. g., the words “was,” “is,” and “know” are not accurately pronounced using phonics rules). Irregular words require a different teaching approach than teaching how to read words that follow a rule-based, letter-sound structure.

g., the words “was,” “is,” and “know” are not accurately pronounced using phonics rules). Irregular words require a different teaching approach than teaching how to read words that follow a rule-based, letter-sound structure.

Despite the presence of irregular words, learning the alphabetic principle thoroughly and using it to read unfamiliar words, is a much better strategy than trying to memorize how to accurately read each word as a whole word, or guessing what the word might be based on its first letter and the words before or after it in the text.

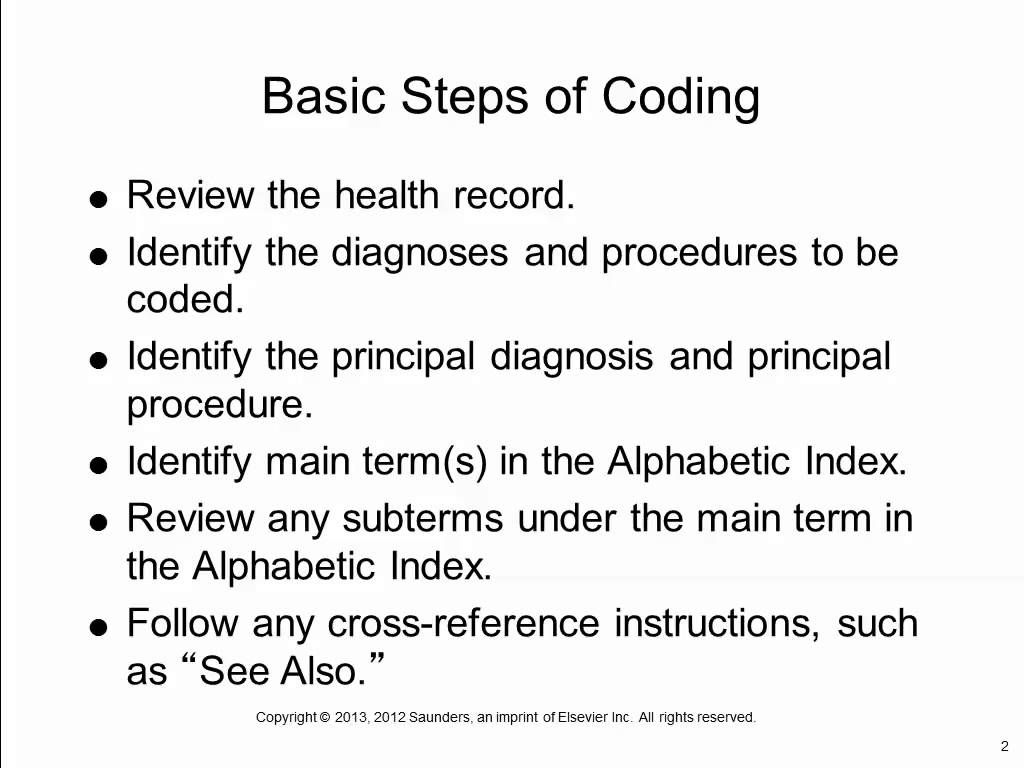

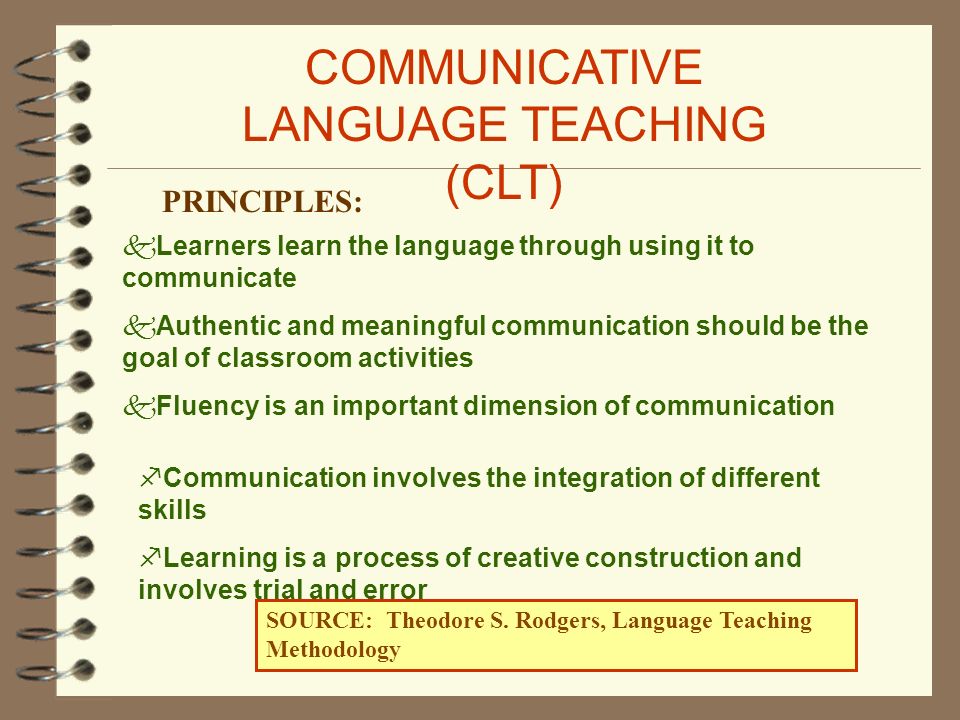

Explicit Phonics Instruction

Explicit phonics instruction—i.e., how the alphabetic principle works, step by step—and extensive practice enables most children to learn the alphabetic principle. Below are effective strategies for teaching the alphabetic principle. These same strategies can be used with children who struggle learning to read, including children with reading disabilities or dyslexia. For students who struggle, highly systematic and explicit instruction plus lots of accuracy practice will be necessary for them to learn the alphabetic principle thoroughly.

All alphabetic languages can be taught using phonics and the alphabetic principle to guide instruction. However, alphabetic languages—English, Spanish, French, Turkish, Vietnamese, and many others—differ dramatically in their alphabetic principle complexity. For example, English is quite complex—there are many rules and exceptions to those rules that need to be learned to read and write correctly. Spanish is much less complex. Letters typically make only one sound regardless of the word they are in and rule exceptions are very few compared to English. For example, Spanish vowels only make one sound. In some cases, the vowel is silent as the letter “u” is in the word, “que.”

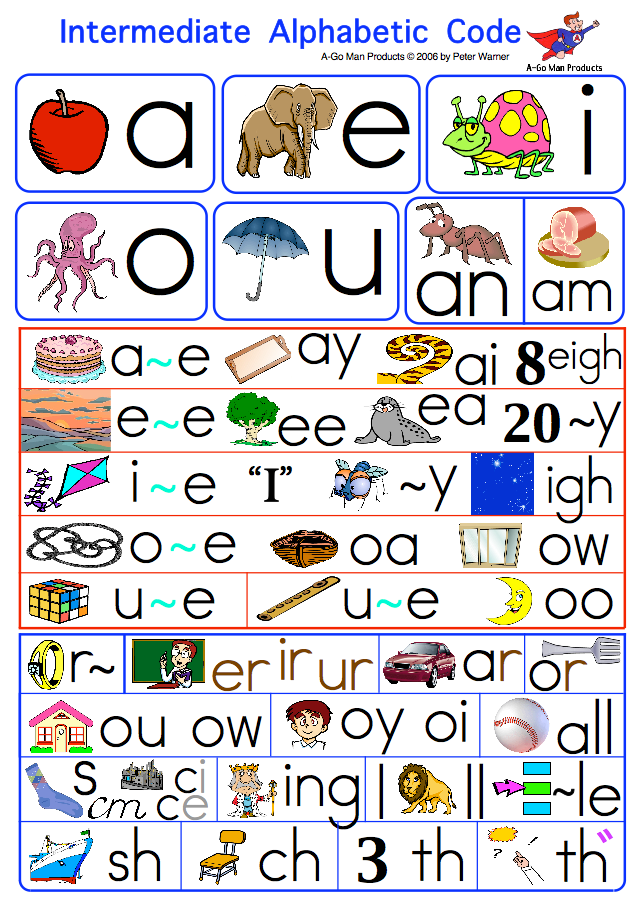

Teach Students To Connect Letters To Their Most Common Sound Or Sounds

All 26 letters in English make at least one predictable or common sound depending on the other letters in the word. For example, each of the three letters in the word “mat” makes its most common sound. In the word “meat” the “m” and “t” make the same sound as they do in “mat” and the “ea” letter combination makes its most common sound when these letters are together in a word. Notice that in the word “meat,” there is only one sound for “ea” even though there are two letters. Teachers can sequence and deliver instruction in a way that helps students efficiently learn the “rules” for the different sounds that letters and letter combinations make.

Notice that in the word “meat,” there is only one sound for “ea” even though there are two letters. Teachers can sequence and deliver instruction in a way that helps students efficiently learn the “rules” for the different sounds that letters and letter combinations make.

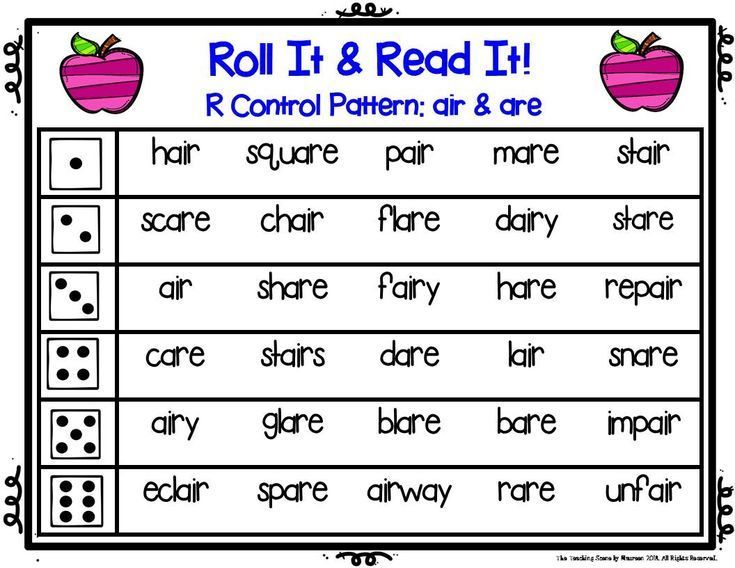

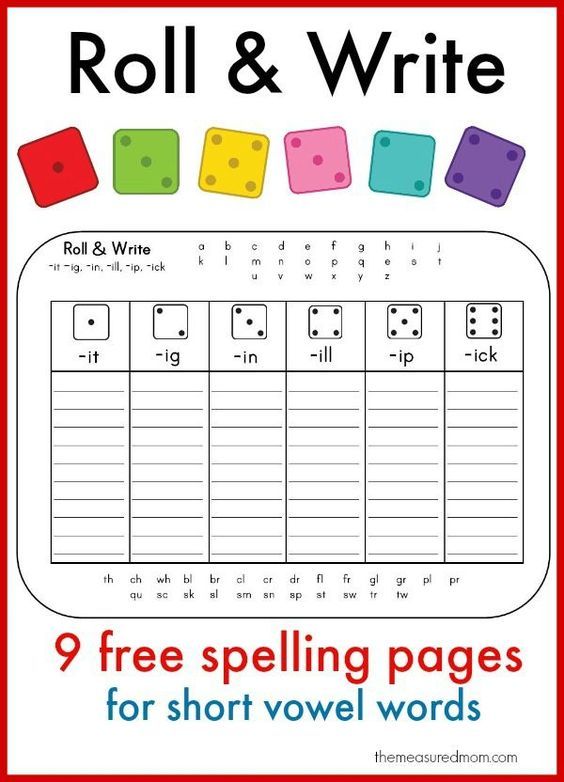

Teach Students To Read Words Using What They Know About The Sounds That Letters And Letter Combinations Make

In using the alphabetic principle, students “blend” the sounds made by individual letters into a whole word. For example, the sounds /m/ /a/ /t/ made by the letters “m,” “a,” and “t” are blended together seamlessly to make the word “mat.” Students should begin learning to read by producing the individual sounds in words and blending the sounds together quickly to produce the whole word with simple CVC words (consonant-vowel-consonant) before progressing to more complex word types that follow other important phonics rules. During instruction, teachers can use a strategy such as “I Do, We Do, You Do” to show students what to do (how to blend), practice with them (students do it with the teacher), and then the students do it on their own to show their teacher they know how to do it. Teaching several of the most common sounds for a few individual letters allows students to read many different words depending on letter order. Teaching other rule types (e.g., letter combinations such as “ea” and “th,” the “Bossy E” rule when “e” comes at the end of a CVC word, and so forth) enables students to accurately read a vast number of words they have never encountered in text.

Teaching several of the most common sounds for a few individual letters allows students to read many different words depending on letter order. Teaching other rule types (e.g., letter combinations such as “ea” and “th,” the “Bossy E” rule when “e” comes at the end of a CVC word, and so forth) enables students to accurately read a vast number of words they have never encountered in text.

Have Students Begin Reading Texts That Contain A High Percentage Of Decodable Words

Early in learning to read, students can begin reading simple books that contain words they can read on their own using the rules of the alphabetic principle. These decodable texts have a high percentage of words that follow common alphabetic principle rules. Students can practice reading these books to build their reading fluency, which helps them focus their attention on understanding the meaning of the text.

Many common words such as “was,” “said” and “of” are irregular words—i.e., they do not follow common alphabetic principle rules. The most common irregular words should be taught early in reading development so that students will be able to read more expanded and interesting texts that are otherwise highly decodable.

The most common irregular words should be taught early in reading development so that students will be able to read more expanded and interesting texts that are otherwise highly decodable.

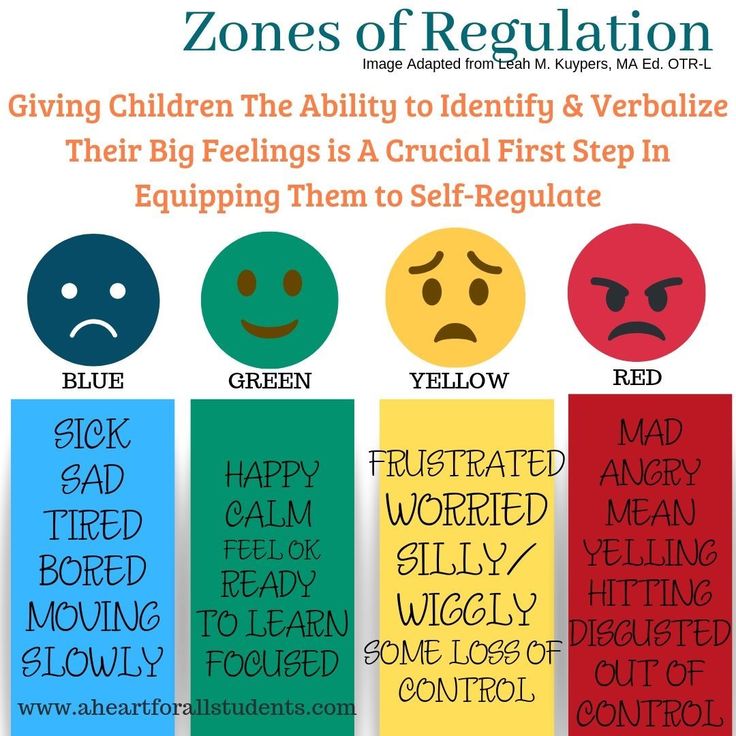

Infographics

Suggested Citation

Baker, S.K., Santiago, R.T., Masser, J., Nelson, N.J., & Turtura, J. (2018). The Alphabetic Principle: From Phonological Awareness to Reading Words. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, Office of Special Education Programs, National Center on Improving Literacy. Retrieved from http://improvingliteracy.org.

References

Carnine, D., Silbert, J., & Kame’enui, E. J. (1997). Direct instruction reading. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill.

Ehri, L. C. (1991). Development of the ability to read words. In R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, & P. D. Pearson (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. 2), 383–417. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Harn, B., Simmons, D. C., & Kame’enui, E. J. (2003). Institute on Beginning Reading II: Enhancing alphabetic principle instruction in core reading instruction [PowerPoint slides]. Retrieved from http://oregonreadingfirst.uoregon.edu/downloads/instruction/big_five/enh...

Liberman, I. Y., & Liberman, A. M. (1990). Whole language vs. code emphasis: Underlying assumptions and their implications for reading instruction. Annals of Dyslexia, 40(1), 51–76. doi:10.1007/bf02648140

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction No. 00-4769). Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Retrieved from http://www.nichd.nih.gov/publications/nrp/smallbook.htm

Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21(4), 360–407. doi:10.1598/rrq.21.4.1

doi:10.1598/rrq.21.4.1

Wagner, R. K., & Torgesen, J. K. (1987). The nature of phonological processing and its causal role in the acquisition of reading skills. Psychological Bulletin, 101(2), 192–212. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.101.2.192

Related Resources

Enhancing the Core: Alphabetic Principle

Oregon Reading First Center

Read presentation slides summarizing ways to enhance alphabetic principle instruction in core reading contexts.

Topic: Phonics

Reading Basics Webinar

Michigan Alliance for Families

This 50-minute webinar overviews the five big ideas of reading, discusses tips for supporting your child's literacy development at home, and explains how schools assess and monitor your child's progress.

Topic: Beginning Reading, Assessments

Alphabetic Principle: Concepts and Research

| Print this page. |

Concepts and Research

- What is the Alphabetic Principle?

- Definitions of key Alphabetic Principle terminology

- Examples of Alphabetic Principle skills

- Alphabetic Principle Research

What is the Alphabetic Principle?

The alphabetic principle is composed of two parts:

- Alphabetic Understanding: Words are composed of letters that represent sounds.

- Phonological Recoding: Using systematic relationships between letters and phonemes (letter-sound correspondence) to retrieve the pronunciation of an unknown printed string or to spell words. Phonological recoding consists of:

- Regular Word Reading

- Irregular Word Reading

- Advanced Word Analysis

Regular Word Reading

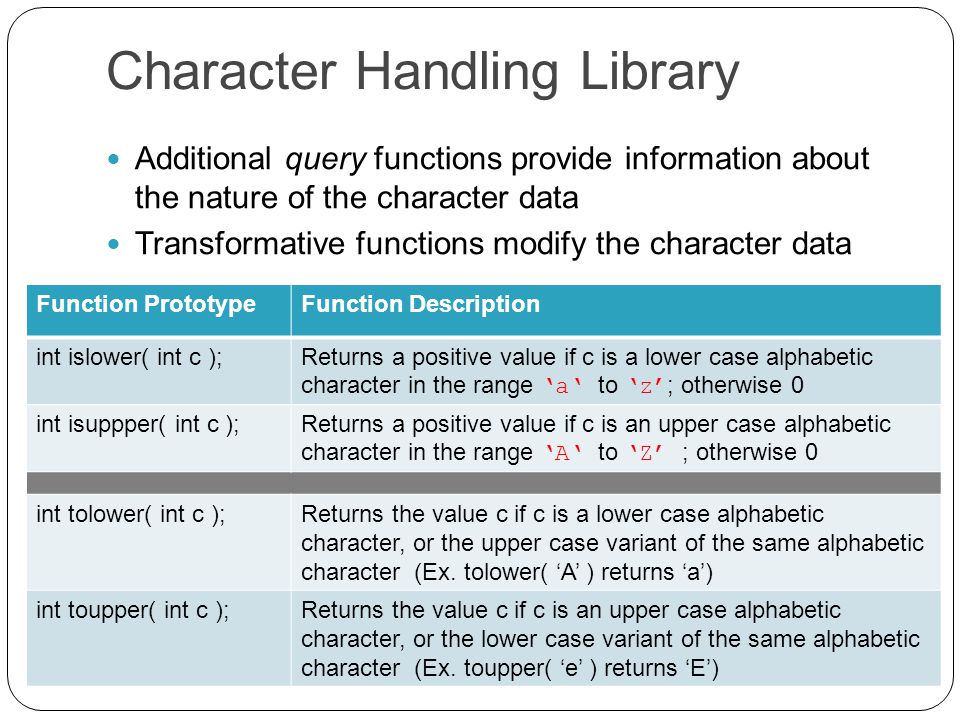

A regular word is a word in which all the letters represent their most common sounds. Regular words are words that can be decoded (phonologically recoded).

Because our language is alphabetic, decoding is an essential and primary means of recognizing words. There are simply too many words in the English language to rely on memorization as a primary word identification strategy (Bay Area Reading Task Force, 1997, see References).

Beginning decoding ("phonological recoding") is the ability to:

- read from left to right, simple, unfamiliar regular words.

- generate the sounds for all letters.

- blend sounds into recognizable words.

Beginning spelling is the ability to:

- translate speech to print using phonemic awareness and knowledge of letter-sounds.

Progression of Regular Word Reading

| Sounding Out (saying each individual sound out loud) | Saying the Whole Word (saying each individual sound and pronouncing the whole word) | Sight Word Reading (sounding out the word in your head, if necessary, and saying the whole word) | Automatic Word Reading (reading the word without sounding it out) |

Simple Regular Words - Listed According to Difficulty

| Word Type | Reason for Relative Ease/Difficulty | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| VC and CVC words that begin with continuous sounds | Words begin with a continuous sound | it, fan |

| VCC and CVCC words that begin with a continuous sound | Words are longer and end with a consonant blend | lamp, ask |

| CVC words that begin with a stop sound | Words begin with a stop sound | cup, tin |

| CVCC words that begin with a stop sound | Words begin with a stop sound and end with a consonant blend | dust, hand |

| CCVC | Words begin with a consonant blend | crib, blend, snap, flat |

| CCVCC, CCCVC, and CCCVCC | Words are longer | clamp, spent, scrap, scrimp |

Irregular Word Reading

Although decoding is a highly reliable strategy for a majority of words, some irregular words in the English language do not conform to word-analysis instruction (e. g., the, was, night). Those words are referred to as irregular words.

g., the, was, night). Those words are referred to as irregular words.

Irregular Word: A word that cannot be decoded because either (a) the sounds of the letters are unique to that word or a few words, or (b) the student has not yet learned the letter-sound correspondences in the word (Carnine, Silbert & Kame'enui, 1997; see References).

Texas Center for Reading and Language Arts, 1998; see References

- In beginning reading there will be passages that contain words that are "decodable" yet the letter sound correspondences in those words may not yet be familiar to students. In this case, we also teach these words as irregular words.

- To strengthen students' reliance on the decoding strategy and communicate the utility of that strategy, we recommend not introducing irregular words until students can reliably decode words at a rate of one letter-sound per second. At this point, irregular words may be introduced, but on a limited scale.

- The key to irregular word recognition is not how to teach them. The teaching procedure is simple. The critical design considerations are how many to introduce and how many to review.

Advanced Word Analysis

Advanced word analysis involves being skilled at phonological processing (recognizing and producing the speech sounds in words) and having an awareness of letter-sound correspondences in words.

Advanced word analysis skills include:

- Knowledge of common letter combinations and the sounds they make

- Identification of VCe pattern words and their derivatives

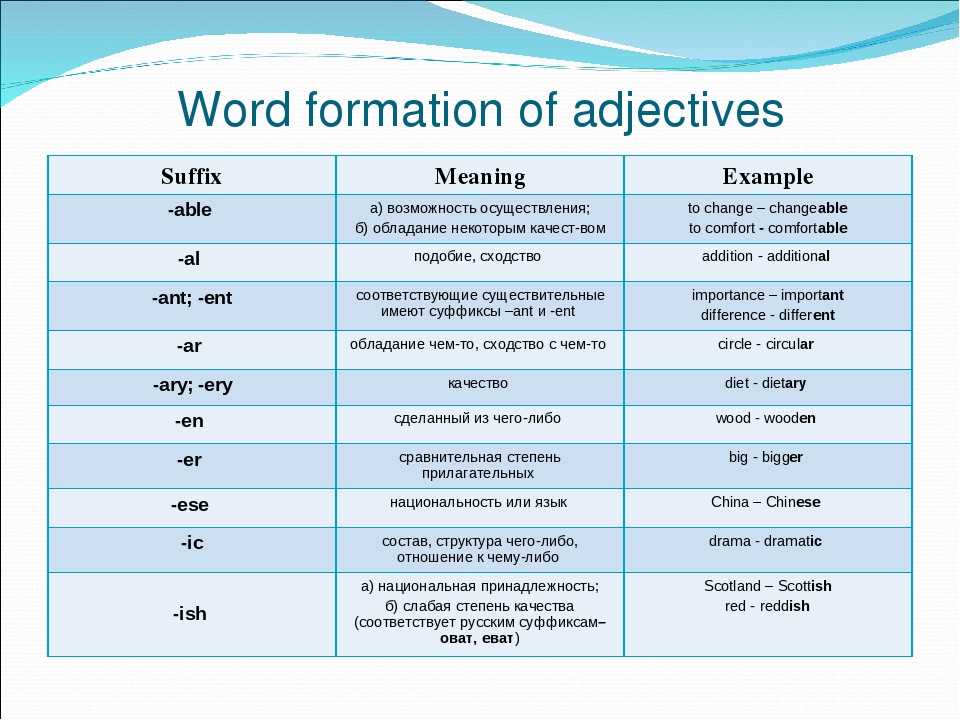

- Knolwedge of prefixes, suffixes, and roots, and how to use them to "chunk" word parts within a larger word to gain access to meaning.

Knowledge of advanced word analysis skills is essential if students are to progress in their knowledge of the alphabetic writing system and gain the ability to read fluently and broadly.

Texas Center for Reading and Language Arts, 1998; see References

Go to top of page

Definitions of key Alphabetic Principle terminology:

- Alphabetic Awareness: Knowledge of letters of the alphabet coupled with the understanding that the alphabet represents the sounds of spoken language and the correspondence of spoken sounds to written language.

- Alphabetic Understanding: Understanding that the left-to-right spellings of printed words represent their phonemes from first to last.

- Continuous Sound: A sound that can be prolonged (stretched out) without distortion (e.g., r, s, a, m).

- Decodable Text: Text in which the majority of words can be identified using their most common sounds. Reading materials in which a high percentage of words are linked to phonics lessons using letter-sound correspondences children have been taught. Decodable text is an intermediate step between reading words in isolation and authentic literature. These texts are used to help students focus their attention on the sound-symbol relationships they are learning. Effective decodable texts contain some sight words that allow for the development of more interesting stories.

- Decoding: The process of using letter-sound correspondences to recognize words.

- Grapheme: The individual letter or sequence of written symbols (e.

g., a, b, c) and the multiletter units (e.g., ch, sh, th) that are used to represent a single phoneme.

g., a, b, c) and the multiletter units (e.g., ch, sh, th) that are used to represent a single phoneme. - Irregular Word: A word that cannot be decoded because either (a) the sounds of the letters are unique to that word or a few words, or (b) the student has not yet learned the letter-sound correspondences in the word.

- Letter Combination: A group of consecutive letters that represents a particular sound(s) in the majority of words in which it appears.

- Letter-Sound Correspondence: A phoneme (sound) associated with a letter.

- Most Common Sound: The sound a letter most frequently makes in a short, one syllable word, (e.g., red, blast). Click here to see a list of the most common sounds of single letters.

- Nonsense or Pseudoword: A word in which the letters make their most common sounds but the word has no commonly recognized meaning (e.g., tist, lof).

- Orthography: A system of symbols for spelling.

- Phonological Recoding: Translation of letters to sounds to words to gain lexical access to the word.

- Regular Word: A word in which all the letters represent their most common sound.

- Sight Word Reading: The process of reading words at a regular rate without vocalizing the individual sounds in a word (i.e., reading words the fast way).

- Sounding Out: The process of saying each sound that represents a letter in a word without stopping between sounds.

- Stop Sound: A sound that cannot be prolonged (stretched out) without distortion. A short, plosive sound (e.g., p, t, k).

- VCe Pattern Word: Word pattern in which a single vowel is followed by a consonant, which, in turn, is followed by a final e (i.e., lake, stripe, and smile).

Go to top of page

Alphabetic Principle Skills

To develop the alphabetic principle across grades K-3, students need to learn two essential skills:

- Letter-sound correspondences: comprised initially of individual letter sounds and progresses to more complex letter combinations.

- Word reading: comprised initially of reading simple CVC words and progresses to compound words, multisyllabic words, and sight words.

Kindergarten Skills

- Letter-sound correspondence: identifies and produces the most common sound associated with individual letters.

- Decoding: blends the sounds of individual letters to read one-syllable words.

- When presented with the word fan the student will say "/fffaaannn/, fan."

- Sight word reading: Recognizes and reads words by sight (e.g., I, was, the, of).

First Grade Skills

- Letter-sound and letter-combination knowledge: produces the sounds of the most common letter sounds and combinations (e.g., th, sh, ch, ing).

- Decoding: sounds out and reads words with increasing automaticity, including words with consonant blends (e.g., mask, slip, play), letter combinations (e.g., fish, chin, bath), monosyllabic words, and common word parts (e.g., ing, all, ike).

- Sight words: Reads the most common sight words automatically (e.g., very, some, even, there).

2nd and 3rd Grade Skills

- Letter-Sound Knowledge: produces the sounds that correspond to frequently used vowel diphthongs (e.g., ou, oy, ie) and digraphs (e.g., sh, th, ea).

- Decoding and Word Recognition:

- applies advanced phonic elements (digraphs and diphthongs), special vowel spellings, and word endings to read words.

- Reads compound words, contractions, possessives, and words with inflectional word endings.

- Uses word context and order to confirm or correct word reading efforts (e.g., does it make sense?).

- Reads multisyllabic words using syllabication and word structure (e.g. base/root word, prefixes, and suffixes) in word reading.

- Sight word reading: increasing number of words read accurately and automatically.

| What Teachers Should Know | What Teachers Should Be Able to Do |

|---|---|

|

|

| (modified from Moats, 1999; see References) | |

What Does the Lack of Alphabetic Understanding Look Like?

Children who lack alphabetic understanding cannot:

- Understand that words are composed of letters.

- Associate an alphabetic character (i.e., letter) with its corresponding phoneme or sound.

- Identify a word based on a sequence of letter-sound correspondences (e.g., that "mat" is made up of three letter-sound correspondences /m/ /a/ /t/).

- Blend letter-sound correspondences to identify decodable words.

- Use knowledge of letter-sound correspondences to identify words in which letters represent their most common sound.

- Identify and manipulate letter-sound correspondences within words.

- Read pseudowords (e.g., "tup", with reasonable speed).

Go to top of page

Alphabetic Principle Research Says:

Letter-sound knowledge is prerequisite to effective word identification. A primary difference between good and poor readers is the ability to use letter-sound correspondence to identify words (Juel, 1991; see References).

Students who acquire and apply the alphabetic principle early in their reading careers reap long-term benefits (Stanovich, 1986; see References).

Teaching students to phonologically recode words is a difficult, demanding, yet achievable goal with long-lasting effects (Liberman & Liberman, 1990; see References).

The combination of instruction in phonological awareness and letter-sounds appears to be the most favorable for successful early reading (Haskell, Foorman, & Swank, 1992; see References).

Good readers must have a strategy to phonologically recode words (Ehri, 1991; NRP, 2000; see References).

During the alphabetic phase, reading must have lots of practice phonologically recoding the same words to become familiar with spelling patterns (Ehri, 1991; see References).

Awareness of the relation between sounds and the alphabet can be taught (Liberman & Liberman, 1990; see References).

Because our language is alphabetic, decoding is an essential and primary means of recognizing words. There are simply too many words in the English language to rely on memorization as a primary word identification strategy (Bay Area Reading Task Force, 1996; see References).

The table below illustrates the important correlation between the ability to decode words and reading comprehension.

| (Foorman, et. al., 1997; see References) |

Go to top of page

news-15122019 | ibt.org.ru

Writing and alphabetic writing systems – the South Caucasian experience

K. Gadiliya

The invention of writing can be equated with such revolutionary events that changed the course of human history as the domestication of fire, the invention of the wheel, the discovery of penicillin. The writing system is a way of fixing, storing and transmitting information using signs, symbols, as well as a way of communication and a way of expressing ideas and emotions. These functions of writing in the specific life of society are implemented in many areas: the management of state institutions (orders, laws), diplomatic relations (relationships between the rulers of states), the management of religious institutions (recording codes and laws, religious treatises). The role of writing is also very significant in the cultural life of mankind.

The role of writing is also very significant in the cultural life of mankind.

The history of writing dates back to ancient times. Everyone has at least the most general idea of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, Sumerian cuneiform or Chinese hieroglyphs. The evolution of writing goes from the pictorial principle to the phonetic one, followed by the construction of an alphabetic writing system. The alphabetic system means that each character stands for a different sound of the language. The first phonetic alphabet known to us is Phoenician (an ancient Semitic script), in which only consonants were represented. The next stage is the Greek alphabet, descending from this writing system, the first alphabet with signs for vowel sounds. It was the Greek system that became the prototype for the well-known Cyrillic and Latin alphabets.

How is writing in the modern world? Do all languages have their own alphabets, their own writing system? Unfortunately, there are still quite a few unwritten modern languages.

The problem of the written implementation of translated texts for non-written languages has to be solved even today. The Institute for Bible Translation developed systems for the non-written Pamir languages (Yazgulyam, Rushan, Vakhani), for the Bezhta language (Dagestan) (see the collection on the IPB website "Translation of the Bible as a factor in the development and preservation of the languages of the peoples of the Russian Federation and the CIS countries. Problems and solutions ". M., IPB, 2010). The article by D. I. Edelman describes the process of developing the conceptual basis of the alphabets of the Pamir languages, which helps to recreate the basic principles for creating alphabetic systems in ancient times: 1. Ease and possibility of further use. 2. Use of an alphabet that already exists and is known to the audience. 3. A systematic approach to the development of graphemes, the ratio of the plan of expression (grapheme) and the plan of content (phoneme, sound) - one sound, one letter.

There are two ways to create national script :

, English (th, sh ch) or German (sсh, ch) digraphs based on the Latin alphabet, additional dots in Arabic writing for the languages of the Near and Middle East, etc.

2. The alphabet of another language is used only as a model, a sample is created a new, original graphic image, to designate sounds that are absent in the alphabet-model, additional new graphemes are created, and unnecessary graphemes acquire a different meaning, for example, they can take on the function of designating numbers. The following features are characteristic of alphabetic systems:

- Grapheme sequence

- Original graphic form

- Writing direction (right to left or vice versa, top to bottom, etc.)

- Transfer of phonetic meaning, i.e. the ratio of sound and graphic image (one sound - one grapheme)

- The numerical value of graphemes (mainly for ancient alphabetic systems, such as Greek, Georgian; over time, the so-called extra graphemes become obsolete and disappear)

The history of writing systems, stages of evolution is a fascinating page of human civilization, but I would like to focus on one specific episode - the appearance of three alphabets almost simultaneously and geographically in the same region in the South Caucasus. Let us pay attention to the two most important aspects in this story: historiographic and grammatical (grammatology is the science of writing).

Let us pay attention to the two most important aspects in this story: historiographic and grammatical (grammatology is the science of writing).

Outstanding linguist Tamaz Gamkrelidze in his bilingual Russian-Georgian book “Alphabetical Writing and Ancient Georgian Writing. Typology and origin of alphabetic writing systems" (Tbilisi, 1989) writes: "A specific group of alphabetic scripts that emerged from the Greek writing system is represented by the scripts of the Christian period: Coptic, Gothic, Old Armenian, Old Slavonic, and also Old Georgian (Iberian) writing systems" (p. .238). T. V. Gamkrelidze does not separately consider the ancient Albanian alphabet due to the lack of the same documentary history in Armenia and Georgia.

Before describing the South Caucasian situation, I will briefly dwell on the typologically similar Old Slavonic (Glagolitic, Cyrillic), Coptic and Gothic scripts. Historical tradition attributes the creation of two Old Slavonic writing systems - Glagolitic and Cyrillic - to the brothers Cyril and Methodius in the 9th century. AD We do not know of historically reliable information or archaeological artifacts of the existence of another original writing system. In the IV century. AD Visigothic bishop Wulfila (318–383) creates the Gothic alphabet specifically for translating the Bible. Prior to this, the Visigoths used monumental runic writing, which they considered pagan and inappropriate for Christian culture. The Coptic alphabet is not as strongly tied to Christianity as the Old Church Slavonic and Gothic. During the Hellenization era in Egypt, the Greek language was at the forefront. It seems that along with Christian culture, the national Coptic language is being revived and instead of a complex demotic script, its own writing system is gradually taking shape based on the Greek alphabet (2nd-3rd centuries AD).

AD We do not know of historically reliable information or archaeological artifacts of the existence of another original writing system. In the IV century. AD Visigothic bishop Wulfila (318–383) creates the Gothic alphabet specifically for translating the Bible. Prior to this, the Visigoths used monumental runic writing, which they considered pagan and inappropriate for Christian culture. The Coptic alphabet is not as strongly tied to Christianity as the Old Church Slavonic and Gothic. During the Hellenization era in Egypt, the Greek language was at the forefront. It seems that along with Christian culture, the national Coptic language is being revived and instead of a complex demotic script, its own writing system is gradually taking shape based on the Greek alphabet (2nd-3rd centuries AD).

There is a widespread opinion about Mesrop Mashtots, an Armenian scholar and priest of the 4th-5th centuries, as the creator of Armenian, Georgian and ancient Albanian (Caucasian-Albanian) writing. Shortly after the death of Mesrop Mashtots (361/2 - 440), his students Koryun (“Life of Mashtots”) and Movses Khorenats (“History of Armenia”) described the activities of Mesrop Mashtots in their writings, including the history of the creation of the Armenian, as well as Georgian and the Caucasian-Albanian alphabets, however, in Georgian historiography there is not the slightest mention of the contribution of Mesrop Mashtots to the creation of the Georgian alphabet. Leonti Mroveli in the 11th century, author of “Kartlis tskhovreba (Life of Kartli)”, Mkhitar Ayrivanksky (Ayrivanetsi), author of the historical work “New History” or “History of Armenia” in the 13th century. King Parnavaz (presumably II-III centuries AD) is called the creator of Georgian writing.

Shortly after the death of Mesrop Mashtots (361/2 - 440), his students Koryun (“Life of Mashtots”) and Movses Khorenats (“History of Armenia”) described the activities of Mesrop Mashtots in their writings, including the history of the creation of the Armenian, as well as Georgian and the Caucasian-Albanian alphabets, however, in Georgian historiography there is not the slightest mention of the contribution of Mesrop Mashtots to the creation of the Georgian alphabet. Leonti Mroveli in the 11th century, author of “Kartlis tskhovreba (Life of Kartli)”, Mkhitar Ayrivanksky (Ayrivanetsi), author of the historical work “New History” or “History of Armenia” in the 13th century. King Parnavaz (presumably II-III centuries AD) is called the creator of Georgian writing.

From the point of view of the graphic plan, “the ancient Georgian script asomtavruli, the ancient Armenian yerkatagir and the old Slavonic Glagolitic fall under a common typological class, being opposed to the Coptic and Gothic scripts and the Cyrillic alphabet,” writes T. V. Gamkrelidze and notes that from a paradigmatic point of view, asomtavruli and Glagolitic are typologically closer to Coptic and Gothic writing systems.

V. Gamkrelidze and notes that from a paradigmatic point of view, asomtavruli and Glagolitic are typologically closer to Coptic and Gothic writing systems.

From the point of view of grammar between the Armenian, Georgian and ancient Caucasian Albanian alphabets, structural differences are revealed, namely the order of graphemes:

- The Armenian alphabet yerkatagir is divided into 4 sections, at the end of each section those Armenian graphemes are inserted that are absent in Greek. The Albanian alphabet is built on the same principle, as well as, in part, the Gothic one.

- The Georgian alphabet is built according to a different principle:

The first 26 letters are Georgian-Greek phonetic correlates, they completely follow the Greek pattern, and 9 specifically Georgian sounds are located at the very end of the alphabet (as in Coptic).

- The Georgian alphabet uses the same model of the Greek alphabet, which includes two Greek letters already out of use in the 4th century.

These are digamma with a numerical value of 6 and koppa with a numerical value of 90. The Georgian alphabet was used for counting, and therefore it was considered an important criterion for creation to follow the numerical value of the characters of the Greek alphabet.

These are digamma with a numerical value of 6 and koppa with a numerical value of 90. The Georgian alphabet was used for counting, and therefore it was considered an important criterion for creation to follow the numerical value of the characters of the Greek alphabet. - The graphic image of the Georgian asomtavruli and the Armenian yerkatagir (as well as the Glagolitic alphabet) completely and consciously deviate from the graphics of the Greek prototype, although the methods of solving this problem differ from each other. Peeters Publishers supervised. Perhaps the most reasonable thing would be to adopt this opinion, until stronger arguments appear to prove or deny the authorship of Mesrop Mashtots of the three Transcaucasian alphabets.

- author Gerasimova Svetlana Anatolyevna

- section cosmography (book II) is devoted to the description of the structure of the Earth;

- in the geography section (books III-VI) concepts from the field of geography are introduced;

- section anthropology (book VII) gives information about the inhabitants of the planet;

- sections of zoology (books VIII-XI) and botany (books XII-XIX) are devoted to the story of the animal and plant worlds;

- sections medicine (books XX-XXXII) and mineralogy (books XXXIII-XXXVII) touch upon the spheres of human life and everyday life known at that time.

Writing as a way of communication and expression of ideas is a universal property of mankind, which in different eras under the influence of various historical and cultural factors is realized in a variety of writing systems.

Biblical Translation Newsletter #2(49), 2019 (origins, stages of formation) Scientific article The purpose of the study is to analyze the origins of the encyclopedia genre as a phenomenon of literature and culture, which has its own history of origin. Scientific novelty lies in a comprehensive analysis of the formation of the encyclopedia as a genre of popular science literature, its transformation from a systematic order of knowledge presentation to an alphabetical organization of articles. Encyclopedic scientists, as compilers of knowledge of the designated period, created reference publications, primarily as educational resources. The result of the study was the presentation of the stages of the formation of encyclopedia from the first ancient encyclopedic works to medieval systematic encyclopedias, which served as teaching aids for students of general education university faculties. The relevance of the chosen research topic is due to the fact that the formation and poetics of the encyclopedia genre in its historical development address the problem of knowledge cyclicity, as well as the evolution and specialization of the term encyclopedia. Currently, the encyclopedia as a special literary work is considered as a universal reference book with an objective presentation of documentary material based on facts (Nikolyukin, 2018) 1 . However, the appearance of encyclopedic works in the period of the VI-XIII centuries. poses an urgent problem for researchers of the typological status of reference publications, determining their contribution to the popularization of scientific knowledge. The use of the genre category in relation to these works of the early Middle Ages will make it possible to concretize certain provisions on the status and originality of reference publications in literary criticism. As part of the study, the following tasks are supposed to be solved: firstly, to characterize the history of the formation of the encyclopedia genre in the diachronic interval on the material of significant reference publications of the 6th-13th centuries; secondly, to analyze the genre of the encyclopedia in terms of the influence of the sociocultural context on its formation; thirdly, to clarify the circumstances of the transformation of this genre from scientific to popular science. To do this, the article uses a combination of comparative historical, biographical and context-interpretative methods of literary analysis. With the help of a systematic approach, an analytical description of the formation of European medieval encyclopedism is provided. Theoretical base of research along with the works of domestic scientists (http://granat.wiki/enc/ee/entsiklopediya; Ukolova, 1989 2 ; Petrov, 2000 3 ; Simon, 2001 4 3 ; Saitov, 2010 9020 5 ), the work of foreign researchers (Le Goff, 1994 6 ; Beyer de Ryke, 2003 7 ), who considered the genre of the encyclopedia in its historical development, served. The practical significance of the study lies in the fact that its results and conclusions can be used by literary critics to continue studying the encyclopedia genre as a system of categories of historical poetics. Encyclopedias as a phenomenon of literature and culture have their own history of origin and formation. Until the appearance in the XVIII century. French Encyclopedia D. Diderot and JL D'Alembert this genre of reference literature had its forerunner in Europe. Researchers of the problem of encyclopedism note that the need for a code and classification of knowledge arose already in Antiquity, which was distinguished by a universal view of the world (Artemyeva, Mikeshin, 2005 8 ; Saitov, 2010 9 ). Foreign researchers distinguish two stages in the development of European medieval encyclopedism. The first stage dates back to 500-1200, when it was important to preserve what was left of the ancient heritage, and there was an acute shortage of philological works: transmettre ce qui reste de l'héritage antique en un temps de pénurie philologique (Beyer de Ryke, 2003, p. The works of Aristotle (Ἀριστοτέλης, 384 BC — 322 BC) were encyclopedically comprehensive in nature, arranged according to the system of knowledge. The collected works of the scientist with comments were published in 1489 in Venice, Basel (1531), Frankfurt (1584), and at the end of the 18th century. published in Greek and Latin. In book. VIII "Policy" dedicated to public education, the expression eleutherioi epistemai 9 is found for the first time0129 , translated as free arts (Simon, 2001) 12 , studied by full (free-born) members of ancient society. Among the authors of the first ancient encyclopedias, more specific in terms of genre, they name a Roman scholar-systematizer, historian, philologist, poet, author of one of the first linguistic works “On the Latin Language” M. T. Varro (Marcus Terentius Varrō, 116-27 BC). In his main encyclopedic work Disciplinae ( Nauki ) the scientist considered nine sciences, each of which he dedicated a separate book: grammar, rhetoric, dialectics, astronomy, geometry, arithmetic, architecture, medicine, music. The work was not called an encyclopedia, but in its form it was a systematic reference publication. Subsequently, the work of M. T. Varro became known due to his citation by other authors, since the work itself was lost. The prototype of all subsequent European encyclopedias in terms of volume, citing authors, certain statements and the presence of an index and content is "Naturalis historia" ( Natural History ) of the ancient Roman writer-erudite Pliny the Elder (Gaius Plinius Secundus, between 22- 24 AD - 79 AD). The ancient Roman writer himself called his work "circular (comprehensive) education" (ἐγκύκλιος παιδεία - enkyuklios paideia). Most likely, this expression formed the basis of the word "encyclopedia". Pliny the Elder tried to connect the development of ancient science with practical activities, namely, with agriculture, trade, and mining. It has become important for the author to establish a connection between man and nature (Albrecht, 2004) 15 . Based on more than 2000 books read, Pliny built the sections of the encyclopedia "Naturalis historia" in the following order (Beyer de Ryke, 2003)

Introduction

Main part

1245) 10 . The second stage in general terms fits into the period 1200-1500. and is characterized by the desire to give access to all knowledge, but by choice and selection of material, since in an era of abundance of books it became necessary to sort out the mass of new knowledge coming from outside: par la volonté de donner accès à l'ensemble du savoir, mais au travers d'un choix et d'une selection car, époque d'abondance livresque, il est devenu nécessaire de faire le tri dans la masse des connaissances nouvelles issues (Beyer de Ryke, 2003, p. 1246) 11 .

1245) 10 . The second stage in general terms fits into the period 1200-1500. and is characterized by the desire to give access to all knowledge, but by choice and selection of material, since in an era of abundance of books it became necessary to sort out the mass of new knowledge coming from outside: par la volonté de donner accès à l'ensemble du savoir, mais au travers d'un choix et d'une selection car, époque d'abondance livresque, il est devenu nécessaire de faire le tri dans la masse des connaissances nouvelles issues (Beyer de Ryke, 2003, p. 1246) 11 .  The number eleutherioi epistemai included seven sciences: grammar, rhetoric, dialectics, geometry, arithmetic, music and astronomy. An inferior citizen (slave) was only allowed access to craft knowledge (Simon, 2001) 13 .

The number eleutherioi epistemai included seven sciences: grammar, rhetoric, dialectics, geometry, arithmetic, music and astronomy. An inferior citizen (slave) was only allowed access to craft knowledge (Simon, 2001) 13 .  Since not a single encyclopedic work of the ancient Greeks has reached the modern era, Varro is considered as the founder of the encyclopedia genre, representing popular science literature on European soil (Simon, 2001) 14 .

Since not a single encyclopedic work of the ancient Greeks has reached the modern era, Varro is considered as the founder of the encyclopedia genre, representing popular science literature on European soil (Simon, 2001) 14 .  First, the areas of study were described, and then their constituent elements, which made it possible to create a fairly clear structure of the work. The beginning of Latin scientific terminology should be sought precisely in the "Natural History" of Pliny the Elder.

First, the areas of study were described, and then their constituent elements, which made it possible to create a fairly clear structure of the work. The beginning of Latin scientific terminology should be sought precisely in the "Natural History" of Pliny the Elder.

In 37 books ( 2493 chapters or paragraphs) that have survived almost completely to this day, a detailed table of contents (first book) is presented for the subsequent thirty-six books. The table of contents, unusual for ancient practice, according to Pliny's justification, was supposed to help the reader overcome the difficulties of continuous reading, which involved the use of "Natural History" for reference purposes. Despite the impressive volume of Pliny's work, his work does not belong to the works of "critical learning", with its authority it spread and illuminated for many years.0116 centuries , along with valuable and real information, the most fantastic fables and superstitions. “In a very imperfectly systematized presentation, he gives information on astronomy (very scarce), physics (also scarce), chemistry, botany, zoology, technology, agriculture and medicine. Speaking about technology, he often gives information about architecture, painting and sculpture. Thus, Pliny completely leaves out all the “verbal” sciences and pays only weak attention to mathematics, physics and philosophy. He prefers applied knowledge to all these sciences: agriculture, medicine, technology” (http://granat.wiki/enc/ee/entsiklopediya).

Thus, Pliny completely leaves out all the “verbal” sciences and pays only weak attention to mathematics, physics and philosophy. He prefers applied knowledge to all these sciences: agriculture, medicine, technology” (http://granat.wiki/enc/ee/entsiklopediya).

We agree with the statement that it was the ancient authors Aristotle, Varro, Pliny who presented encyclopedism as an ideal of culture in their works: c'est l'Antiquité qui a imposé l'encyclopédisme comme idéal culturel (Beyer de Ryke, 2003, p. 1245-1246) 17 .

A brief analysis of Greek and Roman works that were of a reference nature allows us to conclude that there is no single term enkyklopaideia in relation to literary works of this genre. Word encyclopedia among the Greeks and Romans was transferred to general education, limited to the basics of certain sciences, meant a certain “reading circle”, and not a kind of reference or popular science literature.

The birth of medieval encyclopedism is associated with the name of the priest, scholar and writer Isidore of Seville (San Isidoro de Sevilla, about 570-636 AD). Thanks to the work created in the 20 books "Etymologiae sive Origines" ( Etymology, or Beginning ), where a general outline of the knowledge of the era was presented in the form of an explanation of the meanings of words, he is considered one of the mediators between ancient and medieval cultures.

Thanks to the work created in the 20 books "Etymologiae sive Origines" ( Etymology, or Beginning ), where a general outline of the knowledge of the era was presented in the form of an explanation of the meanings of words, he is considered one of the mediators between ancient and medieval cultures.

Etymologies included 48 chapters of the well-known scholar's treatise De natura rerum ( On the Nature of Things , written between 613-621). According to V. I. Ukolova (1989), the treatise was divided into three parts:

- science hemerology (division of time into days, hours, years) the scientist devoted I-VIII chapters;

- Chapters IX-XXVII conveyed knowledge about the Universe (cosmography) and astronomy;

- Isidore of Seville gives a description of the earth and sky, parts of the world, natural phenomena in chapters XXVIII-XLVII (p. 196-197).

This work became the foundation of medieval education, representing the middle, "school" level of reasoning about nature. The composition of "Etymologiae sive Origines" became both an "intellectual" knowledge of nature in the Middle Ages and a salvation for science - "une œuvre de sauvetage" (Beyer de Ryke, 2003, p. 1246) 18 , used for clerics in teaching cosmography (a scientific and educational discipline that studied the structure of the Universe). Scientists have identified seventeen surviving manuscripts, containing in full or in fragments the texts of Etymologies , which allows us to speak about the influence of the treatise of Isidore of Seville on early medieval education. Since the appearance of this work, more than 1000 works have been written imitating the authoritative author: Les Etymologies connaîtront pendant plusieurs siècles un succès considérable dans tout l'Occident, attesté par un nombre impressionnant de manuscrits (plus d'un millier) (Beyer de Ryke, 2003, p. 1250) 19 . "Beginnings" by Isidore of Seville served as one of the main sources as an explanatory, etymological and terminological dictionary for subsequent compilers of encyclopedias (http://granat.

The composition of "Etymologiae sive Origines" became both an "intellectual" knowledge of nature in the Middle Ages and a salvation for science - "une œuvre de sauvetage" (Beyer de Ryke, 2003, p. 1246) 18 , used for clerics in teaching cosmography (a scientific and educational discipline that studied the structure of the Universe). Scientists have identified seventeen surviving manuscripts, containing in full or in fragments the texts of Etymologies , which allows us to speak about the influence of the treatise of Isidore of Seville on early medieval education. Since the appearance of this work, more than 1000 works have been written imitating the authoritative author: Les Etymologies connaîtront pendant plusieurs siècles un succès considérable dans tout l'Occident, attesté par un nombre impressionnant de manuscrits (plus d'un millier) (Beyer de Ryke, 2003, p. 1250) 19 . "Beginnings" by Isidore of Seville served as one of the main sources as an explanatory, etymological and terminological dictionary for subsequent compilers of encyclopedias (http://granat. wiki/enc/ee/entsiklopediya).

wiki/enc/ee/entsiklopediya).

The most prominent figure in education among the Anglo-Saxons Benedictine monk Beda the Venerable (Beda Venerabilis, 672-673 - about 736) compiled a small natural science encyclopedia "De natura rerum" ( On the Nature of Things ), which had a purely educational purpose for the monastic school. The treatise was a compulsory textbook in Carolingian schools (Petrov, 2000, p. 539) 20 .

Lack of understanding of the unity and completeness of general secular education as a result of the pedagogical practice of the Western Middle Ages by the 6th century. contributed to the disappearance of the word enkyklopaideia from the literary lexicon of Western Europe (Simon, 2001) 21 .

Glossaries - alphabetical explanatory dictionaries of little-used words and expressions become a characteristic variety of scientific literature throughout the Middle Ages. Among the authoritative explanatory dictionaries of the early Middle Ages, we will name "Liber glossarum" ( Book of gloss ), written in the VIII century. Carolingian minuscule. Glosses were actively used in teaching, which indicates their influence on the intellectual life of the society of the era of their creation.

Carolingian minuscule. Glosses were actively used in teaching, which indicates their influence on the intellectual life of the society of the era of their creation.

Philosophers involved in the history of gloss note that “numerous glossaries are an excellent source for understanding the peculiarities of Western European science and the school of the early Middle Ages, since the educational and research processes were reflected in them not in the form of already completed works, but imprinted in fieri, in the formation: as they were at one time or another inside the walls of the classroom. Each manuscript containing glosses on a school text records the activities of a particular center at a specific time. By examining the glosses, one can understand what and how they taught and studied” (Petrov, 2000, p. 537) 22 . Glossaries did not have the same significance and distribution as systematic encyclopedias, were not designed for a wide range of readers, were not adapted for educational purposes, but focused on those who independently studied various sciences (http://granat. wiki/enc/ee/entsiklopediya ).

wiki/enc/ee/entsiklopediya ).

However, the desire to cover the totality of human knowledge, as well as the desire for grandiose synthesis, contributed to the emergence of numerous works similar to encyclopedias in the modern sense of the word. But one common term did not arise for them, which was a lot of obstacles: the low level of scientific research, the lack of division into disciplines, “the diversity of the content of the relevant works, covering various subjects: from God and angels to ways of smoking herrings and treating maids; variety of types of medieval encyclopedias, their readership and target settings” (Simon, 2001) 23 . Until the 12th century, encyclopedias mainly reflected the philosophical system of Augustine , and Plato , who had a significant impact on this system with his works, influenced the encyclopedias that popularized it (http://granat.wiki/enc/ee/entsiklopediya).

The 13th century became the golden age of medieval encyclopedism, as the authoritative historian once wrote Jacques Le Goff (Le Goff, 1994) 24 . Four works of the end of the XII century. and the end of the thirteenth century. are key in this regard, when the compilation of knowledge and its popularization become significant. This is a small encyclopedia "De naturis rerum" ( On the nature of things ) English theologian, scientist-encyclopedist Alexander Neckam (Alexander Neckam, 1157-1217). Along with reverence for the name of Aristotle, Neckam is characterized by an increase in geographical information in the encyclopedia and their relative clarification as a result of the Crusades. Neckam's interest in technology is noted: in his work, he, the first European, spoke about the compass and glass mirrors (http://granat.wiki/enc/ee/entsiklopediya).

Four works of the end of the XII century. and the end of the thirteenth century. are key in this regard, when the compilation of knowledge and its popularization become significant. This is a small encyclopedia "De naturis rerum" ( On the nature of things ) English theologian, scientist-encyclopedist Alexander Neckam (Alexander Neckam, 1157-1217). Along with reverence for the name of Aristotle, Neckam is characterized by an increase in geographical information in the encyclopedia and their relative clarification as a result of the Crusades. Neckam's interest in technology is noted: in his work, he, the first European, spoke about the compass and glass mirrors (http://granat.wiki/enc/ee/entsiklopediya).

The compendium "De proprietatibus rerum" ( On the Properties of Things ) Bartholomeus of England (lat. Bartholomaeus Anglicus, French Barthélémy l'Anglais, 1190-1250), consisting of 19 books. In his work, the author presented various aspects of medieval science: theology, medicine, astronomy, geography, etc. It is curious that Bartholomew the English, like some earlier encyclopedists (Pliny, Isidore of Seville), in many cases refused a systematic arrangement, giving material in the alphabet of the names of objects, although this alphabet is very imperfect: only the first letter of the word is taken into account. Due to its relatively small format by medieval standards, which included a fairly large amount of information, the encyclopedia of Bartholomew of England was a success with the medieval reader for a long time, becoming a manual for students of the so-called faculties of arts.

It is curious that Bartholomew the English, like some earlier encyclopedists (Pliny, Isidore of Seville), in many cases refused a systematic arrangement, giving material in the alphabet of the names of objects, although this alphabet is very imperfect: only the first letter of the word is taken into account. Due to its relatively small format by medieval standards, which included a fairly large amount of information, the encyclopedia of Bartholomew of England was a success with the medieval reader for a long time, becoming a manual for students of the so-called faculties of arts.

The popularity of the compendium is evidenced by the fact that from the end of the 15th century. until the beginning of the 17th century. the work of Bartholomew the English was reprinted 75 times in Latin and translated into languages new for that era (English, French, Spanish). According to the calculations of the German researcher E. Voigt , by the beginning of the 20th century. about 90 manuscripts of the essay "On the Properties of Things" (Matuzova, 1979) 25 were stored in the libraries of Europe.

Encyclopedic work "Liber de natura rerum" ( The Book of the Nature of Things ) Thomas of Cantempre (lat. Thomās Cantimpratensis, French Thomas de Cantimpré, 1201-1270) dedicated more than 15 years. He focused his attention on natural science, primarily on the world of animate and inanimate nature. In its final form, the work contains twenty books (in imitation of Isidore of Seville's Etymologies), each of which is devoted to a separate branch of the science of nature. All material about quadrupeds, birds, sea monsters, fish, snakes, worms, trees, plants and stones, the author arranged alphabetically. Thomas supplemented the long-established, canonical list with new characters, devoting a separate book to the monsters of the sea (https://facetia.ru/node/2781).

Encyclopedist and philosopher, theologian Vincent of Beauvais (Latin Vincentius Bellovacensis; French Vincent de Beauvais, 1190-1264) created a huge universal encyclopedia Speculum majus ( Great Mirror ), based on a systematic order presentation. Written in Latin, the work consists of 80 books, including 9885 chapters, with the volume of each volume being about thousand pages. This is the most significant encyclopedia of the Middle Ages, it consists of 4 parts:

Written in Latin, the work consists of 80 books, including 9885 chapters, with the volume of each volume being about thousand pages. This is the most significant encyclopedia of the Middle Ages, it consists of 4 parts:

- Speculum naturale (Natural mirror) - 32 books in 3718 chapters;

- Speculum doctrinale (Doctrine mirror) — 17 books in 2374 chapters;

- Speculum historiale (Historical mirror) — 31 book in 3793 chapters;

- Speculum morale (Moral Mirror) (Shishkov, 2003, p. 168-169) 26 .

To compile his work, the philosopher attracted a huge literature, having analyzed the works of approximately 350 writers, whose names are mentioned in the largest part in terms of volume - "Speculum naturale" . In addition to individual author's names, the creator of "Speculum majus" mentions anonymous texts dedicated to the lives of saints, conciliar acts, etc. , which allows us to talk about a huge number of sources to which he turned. Asked how could one people to cope with such a huge literature, the Russian historian notes that “in the libraries of medieval monasteries, partly for economic reasons, mainly because of the high cost of parchment, instead of complete collections of authors, they willingly resorted to selections from them, to the so-called florilegia, i.e. . actually "flower beds", extending them to both pagan and Christian literature, mainly for the purposes of textbooks and educational, i.e. as role models, especially in sermons, and additions to lectures. <...> But these florilegions were not enough to read, they had to be rewritten either in their entirety or in extracts” (McLein, 1932) 27 . Comprehensive assistance was provided by brothers in the order, they copied the necessary texts, as well as articles edited by the scientist himself. In addition, King Saint Louis IX , interested in the success of the work, provided extensive assistance by paying the cost of the books needed for the encyclopedia and providing funds for making copies.

, which allows us to talk about a huge number of sources to which he turned. Asked how could one people to cope with such a huge literature, the Russian historian notes that “in the libraries of medieval monasteries, partly for economic reasons, mainly because of the high cost of parchment, instead of complete collections of authors, they willingly resorted to selections from them, to the so-called florilegia, i.e. . actually "flower beds", extending them to both pagan and Christian literature, mainly for the purposes of textbooks and educational, i.e. as role models, especially in sermons, and additions to lectures. <...> But these florilegions were not enough to read, they had to be rewritten either in their entirety or in extracts” (McLein, 1932) 27 . Comprehensive assistance was provided by brothers in the order, they copied the necessary texts, as well as articles edited by the scientist himself. In addition, King Saint Louis IX , interested in the success of the work, provided extensive assistance by paying the cost of the books needed for the encyclopedia and providing funds for making copies. The Great Mirror had a great influence on many didactic poems of the 14th and 15th centuries. and even reflected on the Divine Comedy Dante . Since the invention of the printing press, the Mirror has been printed at least six times . Even after the appearance of encyclopedias with alphabetical organization of articles instead of the archaic structure of the medieval manuscript (divided into sections, then into books, chapters and paragraphs), it was reprinted twice (in 1521 and 1627).

The Great Mirror had a great influence on many didactic poems of the 14th and 15th centuries. and even reflected on the Divine Comedy Dante . Since the invention of the printing press, the Mirror has been printed at least six times . Even after the appearance of encyclopedias with alphabetical organization of articles instead of the archaic structure of the medieval manuscript (divided into sections, then into books, chapters and paragraphs), it was reprinted twice (in 1521 and 1627).

Conclusion

A review of the works of the indicated period shows that encyclopedic works existed, but there was no term for such a genre. Most of the encyclopedic works supported medieval education. In medieval universities and numerous schools, the number of students and students who needed educational resources grew. Being generally compilers of the knowledge of the relevant period, encyclopedic scholars actually contributed to the creation of encyclopedias as educational resources. The knowledge paradigm has activated the progressive process of scientific communication. Encyclopedically educated people created popular science literature, which made up the history of the encyclopedia genre, in such proto-genres as a compendium, treatise, etymological dictionary, mirror, glossaries, etc.

The knowledge paradigm has activated the progressive process of scientific communication. Encyclopedically educated people created popular science literature, which made up the history of the encyclopedia genre, in such proto-genres as a compendium, treatise, etymological dictionary, mirror, glossaries, etc.

Prospects for further research of the problem lie in the need to study the formation and successful development of the encyclopedia in the era of the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. It is necessary to consider the reference works of this period as a form of representation and classification of knowledge, the compatibility of this literary genre with the specific socio-cultural values of the educated circle of the European language community.

Sources

- Albrecht M. fon. History of Roman literature from Andronicus to Boethius and its influence on later eras: in 3 volumes / transl. with him. A. I. Lyubzhina. M.: Greco-Latin cabinet Yu. A.

Shichalin, 2004. V. 2.

Shichalin, 2004. V. 2. - Artemyeva T. V., Mikeshin M. I. Encyclopedia as a form of universal knowledge // Man. 2005. No. 2.

- MacLein A. I. Encyclopedia of Vincenius of Beauvais // Proceedings of the Institute of Books, Documents and Letters. II. L.: AN SSSR, 1932. URL: http://annales.info/evrope/france/vincent.htm

- Matuzova V. I. Bartholomew English // English medieval sources. M.: Science. 1979.

- Nikolyukin A. Encyclopedia as a genre // Literary newspaper. April 11, 2018 URL: https://lgz.ru/article/-15-6639-11-04-2018/entsiklopediya-kak-zhanr/

- Petrov V.V. Oserra // Philosophy of nature in antiquity and the Middle Ages: a collection of translations and studies / gen. ed., comp., introduction. P. P. Gaidenko and V. V. Petrov. M.: Progress-Tradition, 2000.

- Saitov UG Pages of the history of encyclopaedics // Problems of Oriental Studies. 2010. No. 1 (47).

- Simon KR Terms Encyclopedia and Free Arts in their historical development / / Russian language.

2001. No. 34. URL: https://rus.1sept.ru/article.php?ID=200103404

2001. No. 34. URL: https://rus.1sept.ru/article.php?ID=200103404 - Ukolova V. I. Birth of medieval encyclopedism. Isidore of Seville // Antique Heritage and Culture of the Early Middle Ages (late 5th - early 7th century). Moscow: Nauka, 1989.

- Shishkov A. M. Medieval intellectual culture. Moscow: Publisher Savin S.A., 2003.

- Beyer de Ryke B. Le miroir du monde: un parcours dans l'encyclopédisme médiéval // Revue belge de Philologie et d'Histoire. 2003. T. 81. F. 4.

- Le Goff J. Pourquoi le XIIIe siècle a-t-il été plus particulièrement un siècle d’encyclopédisme? // L'enciclopedismo médiévale: Atti del convegno, San Gimignano, 8-10 October 1992. Ravenna: Ed. M. Picone, 1994.

Date of receipt of the manuscript (received): 02.11.2021; published: 12/28/2021.

- Persons

Mentioned persons, pseudonyms and characters

- Aristotle

- Bartholomew English

- Bede The Honorable

- Blessed Augustine

- Vincent of Beauvais

- Dante Alighieri

- Diderot Denis

- D'Alembert Jean Leron

- Isidore of Seville

- Le Goff Jacques

- Louis the 9th Saint

- Mark Terence Varro

- Neckam Alexander

- Plato

- Pliny the Elder

- Ukolova Victoria Ivanovna

- Voigt Edmund

- Thomas of Cantempre

- Tags

- 500-1250

- encyclopedia

- encyclopedism

- Medieval West

- Middle Ages

- pedagogical practice

- popular science literature

- Western Medieval

- popular science literature

- teaching practice

- Middle Ages

- encyclopedia

- encyclopedia

- Link to the source on the Internet https://www.

Learn more