Dinosaur can fly

Dinosaurs Evolved Flight at Least Three Times | Science

A Microraptor, a small four-winged dinosaur that could fly, eats a fish. Emily Willoughby / Stocktrek Images via Getty ImagesFlight is a relatively rare ability. Many animals crawl, slither, burrow, walk and swim, but comparatively few have the ability to take to the air. There’s something about evolving the ability to fly that’s more difficult than other ways of getting around. Yet, despite these challenges, dinosaurs didn’t just evolve the ability to fly once, but several times.

The previously-unappreciated aerodynamic capabilities of many feathered dinosaurs allowed more of the “terrible lizards” to fly than previously thought. That’s the conclusion of a new study conducted by University of Hong Kong paleontologist Michael Pittman and colleagues, published earlier this year in

Current Biology. Instead of flight evolving as a single process of greater aerodynamic ability in one lineage alone, the process was something that might be called experimental with many different feathered dinosaurs moving, flapping, fluttering and flying in different ways. “The current paradigm shift involves recognition that flight was arising independently from different, closely-related groups at nearly the same time,” Pittman says. “This moves away from the traditional idea that flight is a rare gem.”

Much of what we know about dinosaur flight comes from birds. That’s because all birds are living dinosaurs, the last remaining members of the family. The raptor-like ancestors of birds split off from their closest dinosaur relatives during the Jurassic, about 150 million years ago, and were just another part of the Age of Dinosaurs. When an asteroid strike sparked a mass extinction 66 million years ago, beaked birds were the only dinosaurs to survive the catastrophe and carry on the legacy of the terrible lizards to the present day.

But this picture is still relatively new. For decades, in books and museum displays, paleontologists differentiated dinosaurs from other ancient reptiles by the fact that dinosaurs didn’t fly or swim. “Flight is not something dinosaurs were traditionally expected to do,” says Pittman. The change came not only from new discoveries, including finds of feathered dinosaurs, but from new ways of analyzing and thinking about fossils. Beyond the gross anatomy of the fossils, paleontologists use an evolutionary classification called cladistics focused on which traits are shared between animals—a technique that allows a clearer picture of how each dinosaur species is related to others. Being able to discern who is most closely related to whom—such as which non-bird dinosaurs were most closely-related to the first birds—is an important part of reconstructing how feathery dinosaurs evolved the ability to fly. Paleontologists have also been able to borrow from engineering techniques to study the aerodynamic capabilities of feathered dinosaurs, allowing experts to better test which species could flap through the air and which were permanently grounded.

The change came not only from new discoveries, including finds of feathered dinosaurs, but from new ways of analyzing and thinking about fossils. Beyond the gross anatomy of the fossils, paleontologists use an evolutionary classification called cladistics focused on which traits are shared between animals—a technique that allows a clearer picture of how each dinosaur species is related to others. Being able to discern who is most closely related to whom—such as which non-bird dinosaurs were most closely-related to the first birds—is an important part of reconstructing how feathery dinosaurs evolved the ability to fly. Paleontologists have also been able to borrow from engineering techniques to study the aerodynamic capabilities of feathered dinosaurs, allowing experts to better test which species could flap through the air and which were permanently grounded.

In the new Current Biology study, the evolutionary tree of dinosaurs related to birds lined up with what paleontologists have reported. The closest relatives to early birds, the study found, were deinonychosaurs—the family of raptor-like, feathered dinosaurs that contains the likes of Velociraptor and Troodon. But then the researchers went a step further. By looking at whether the dinosaurs could overcome some of the mechanical constraints needed to make flapping motions required for flying, the paleontologists found that the potential for deinonychosaurs to fly evolved at least three times.

The closest relatives to early birds, the study found, were deinonychosaurs—the family of raptor-like, feathered dinosaurs that contains the likes of Velociraptor and Troodon. But then the researchers went a step further. By looking at whether the dinosaurs could overcome some of the mechanical constraints needed to make flapping motions required for flying, the paleontologists found that the potential for deinonychosaurs to fly evolved at least three times.

Given that all living vertebrates capable of powered flight leap into the air—whether bats or birds—Pittman and colleagues hypothesize that dinosaurs did the same. Even though paleontologists previously debated whether dinosaurs evolved flight from the “ground up” by running and jumping, or from the “trees down” by gliding, the fact that living animals take off by leaping indicates that deinonychosaurs did, too, regardless of what substrate they pushed off from. “This isn’t exclusive to take off from the ground or from height,” Pittman notes, “so birds in a tree also leap to take off. ”

”

Naturally, birds and their closest relatives—such as the small, magpie-colored deinonychosaur Anchiornis—had the anatomical hallmarks of powered flight. These dinosaurs were small, had lightweight bones, possessed long feathers along their arms and had strong legs that allowed the dinosaurs to leap after prey—and sometimes into the air. The researchers also looked at wing loading, or the size of each deinonychosaur’s wing relative to their body size. By comparing the wing loading estimates to figures derived from animals known to fly today, the researchers were able to narrow down which deinonychosaurs could likely fly and which could not.

In addition to the deinonychosaurs most closely-related to birds, the paleontologists found that two other deinonychosaur lineages had wings capable of powered flight. Within a group of Southern Hemisphere raptors called unenlagines, a small, bird-like dinosaur called Rahonavis would have been able to fly. On a different branch, the four-winged, raven-shaded dinosaur Microraptor shared similar abilities. More than that, the researchers found a few other species on varied parts of the deinonychosaur family tree—such as Bambiraptor and Buitreraptor—that were getting anatomically close to fulfilling the requirements for flight. Flight wasn’t just for the birds, in other words. Many non-bird dinosaurs were evolving aerodynamic abilities, but only a few were able to actually flap their wings and fly.

More than that, the researchers found a few other species on varied parts of the deinonychosaur family tree—such as Bambiraptor and Buitreraptor—that were getting anatomically close to fulfilling the requirements for flight. Flight wasn’t just for the birds, in other words. Many non-bird dinosaurs were evolving aerodynamic abilities, but only a few were able to actually flap their wings and fly.

“The new paper is really exciting and opens new views on bird origins and the early evolution of flight,” says Bernardino Rivadavia Natural Sciences Argentine Museum paleontologist Federico Agnolin. So far, other studies haven’t found the same pattern of dinosaurs evolving flight more than once. Given that dinosaur family trees are bound to change with the discovery of new fossils, Agnolin adds, this might mean that the big picture of how many times flight evolved might change. All the same, he adds, “I think that the new study is really stimulating.”

The major question facing paleontologists is why so many feathered dinosaurs evolved the ability to fly, or got close to it. Flight has particular physical requirements—such as wings capable of generating enough lift to get the animal’s weight off the ground—and paleontologists have long proposed that what dinosaurs were doing on the ground might have had a role to play in opening up the possibility to flight. “Repeated evolution of powered flight is almost certainly related to feathery deinonychosaurs doing things that opened up the possibility of flight,” Pittman says. Feathers were important to display, insulation, fluttering to pin down prey, flapping to create more grip while running up inclines and other activities. Becoming more maneuverable on the ground, in other words, may have helped dinosaurs repeatedly stumble upon the ability to fly.

Flight has particular physical requirements—such as wings capable of generating enough lift to get the animal’s weight off the ground—and paleontologists have long proposed that what dinosaurs were doing on the ground might have had a role to play in opening up the possibility to flight. “Repeated evolution of powered flight is almost certainly related to feathery deinonychosaurs doing things that opened up the possibility of flight,” Pittman says. Feathers were important to display, insulation, fluttering to pin down prey, flapping to create more grip while running up inclines and other activities. Becoming more maneuverable on the ground, in other words, may have helped dinosaurs repeatedly stumble upon the ability to fly.

Getting a clearer picture of when and how flight evolved among dinosaurs surely rests on finding more fossils. Each one adds another paleontological puzzle piece in the effort to understand when and how dinosaurs evolved the ability to fly. Now flight seems to have evolved more than once, experts may very well find new dinosaurs that were not ancestors of birds but still took to the skies all the same. As paleontologists continue to scour rocky outcrops and museum collections for new clues, a new understanding of flight in the Age of Dinosaurs seems cleared for take off.

As paleontologists continue to scour rocky outcrops and museum collections for new clues, a new understanding of flight in the Age of Dinosaurs seems cleared for take off.

Recommended Videos

Pterodactyl: Facts about pteranodon & other pterosaurs

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

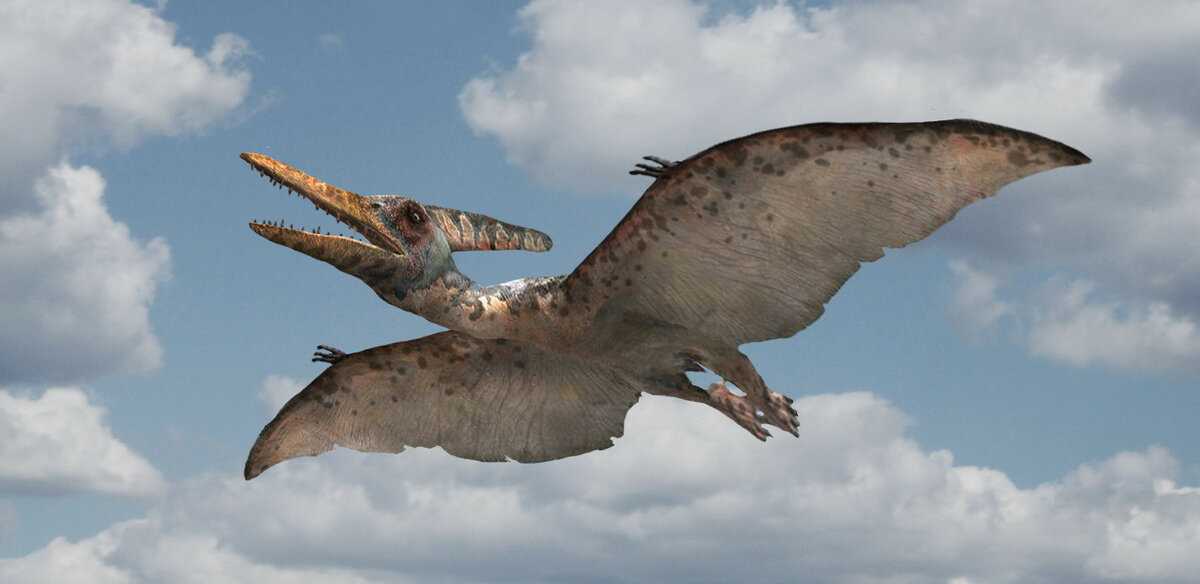

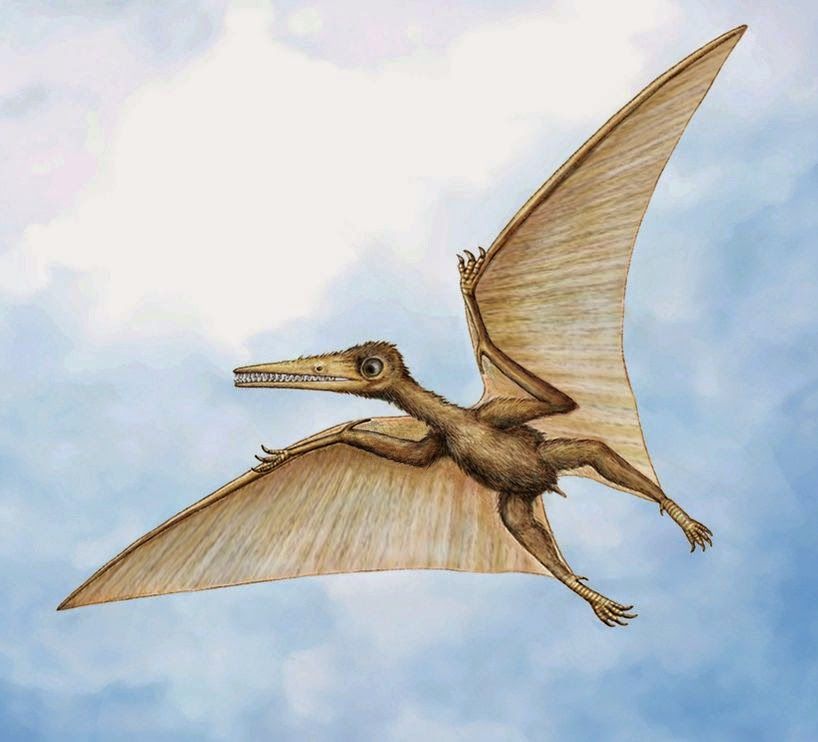

An illustration of a pteranodon flying during the Mesozoic era. (Image credit: Getty Images)Pterodactyl is the common term for the winged reptiles properly called pterosaurs, which belong to the taxonomic order Pterosauria, according to McGill University . Scientists typically avoid using the term and concentrate on individual genera, such as Pterodactylus and Pteranodon.

There are at least 130 valid pterosaur genera, according to David Hone, a palaeontologist at Queen Mary University of London. They were widespread and lived in numerous locations across the globe, from China to Germany to the Americas.

Pterosaurs first appeared in the late Triassic Period and roamed the skies until the end of the Cretaceous period (228 million to 66 million years ago), according to the journal Zitteliana . Pterosaurs lived among the dinosaurs and became extinct around the same time, but they were not dinosaurs. Rather, pterosaurs were flying reptiles.

Modern birds didn't descend from pterosaurs; birds' ancestors were small, feathered, terrestrial dinosaurs.

The first pterosaur discovered was Pterodactylus, identified in 1784 by Italian scientist Cosimo Collini, who thought he had discovered a marine creature that used its wings as paddles, according to the Geological Society of London .

A French naturalist, Georges Cuvier, proposed that the creatures could fly in 1801, and then later coined the term "Ptero-dactyle" in 1809 after the discovery of a fossil skeleton in Bavaria, Germany. This was the term used until scientists realized they were finding different genera of flying reptiles. However, "pterodactyl" stuck as the popular term.

However, "pterodactyl" stuck as the popular term.

Pterodactylus comes from the Greek word pterodaktulos, meaning "winged finger," which is an apt description of its flying apparatus. The primary component of the wings of Pterodactylus and other pterosaurs were made up of a skin and muscle membrane that stretched from the animals' highly elongated fourth fingers of the hands to the hind limbs, according to Mcgill University.

The reptiles also had membranes running between the shoulders and wrists (possibly incorporating the first three fingers of the hands), and some groups of pterosaurs had a third membrane between their legs, which may have connected to or incorporated a tail.

related links

Early research suggested pterosaurs were cold-blooded animals that were more suited to gliding than active flying. However, scientists later discovered that some pterosaurs, including Sordes pilosus and Jeholopterus ninchengensis, had furry coats consisting of hairlike filaments called pycnofibers, suggesting they were warm-blooded and generated their own body heat, according to the Chinese Science Bulletin .

What's more, a study published in the journal PLOS One suggested pterosaurs had powerful flight muscles, which they could use to walk as quadrupeds (on all fours) like vampire bats and vault into the air. Once airborne, the largest pterosaurs (Quetzalcoatlus northropi) could reach speeds of over 67 mph (108 kph) for a few minutes and then glide at cruising speeds of about 56 mph (90 kph), the study found.

Sizes of pterosaurs

The smallest pterosaur, called Nemicolopterus crypticus, was discovered in the western part of China's Liaoning Province. It had a wingspan of only 10 inches (25 centimeters), according to a description of the animal, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences . The remains of this flying reptile revealed that over half of the length of its wing was occupied by a long finger, which anchored the membrane that made up the wing to the body, according to the Carnegie Museum of Natural History .

Pterodactylus antiquus (the only known species of the genus) was also a comparatively small pterosaur, with an estimated adult wingspan of about 3. 5 feet (1.06 meters), according to the journal Paläontologische Zeitschrift . There was some confusion early on as to the size of the Pterodactylus, because some of the specimens turned out to be juveniles rather than adults.

5 feet (1.06 meters), according to the journal Paläontologische Zeitschrift . There was some confusion early on as to the size of the Pterodactylus, because some of the specimens turned out to be juveniles rather than adults.

The largest species that would have soared during the Jurassic period – 201.3 militon to 145 million years ago – was the Dearc sgiathanach. The remains of this pterosaur were found in Scotland’s Isle of Skye an revela the reptile had a wingspan of more than 8 feet (2.5 meters), according to the journal Current Biology .

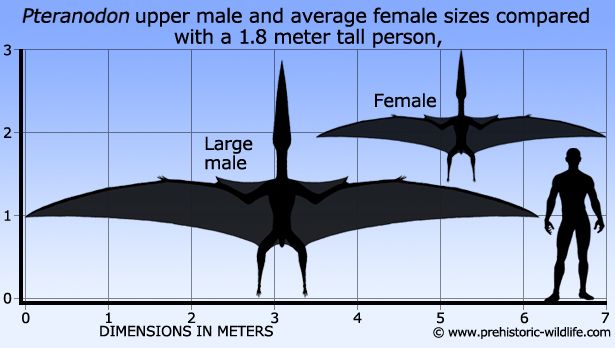

Pteranodon, discovered in 1876 by Othniel C. Marsh, was much bigger. It had a wingspan that ranged from 9 to 20 feet (2.7 to 6 m), according to Current Research in Earth Sciences , a peer-reviewed bulletin of the Kansas Geological Survey. It's thought that Pteranodon spent its time soaring over open ocean in the hunt for fish. These pterosaurs would have been rarely seen on land and potentially spent their time on the water when not in the air, according to the American Museum of natural History . This means that their wings would have had to generate enormous amounts of force to lift them from the water back into the sky.

This means that their wings would have had to generate enormous amounts of force to lift them from the water back into the sky.

Another large pterosaur was Coloborhynchus capito, which had a wingspan of about 23 feet (7 m). This discovery, described in the journal Cretaceous Research, followed an examination of a fossil that had been in the Natural History Museum of London since 1884.

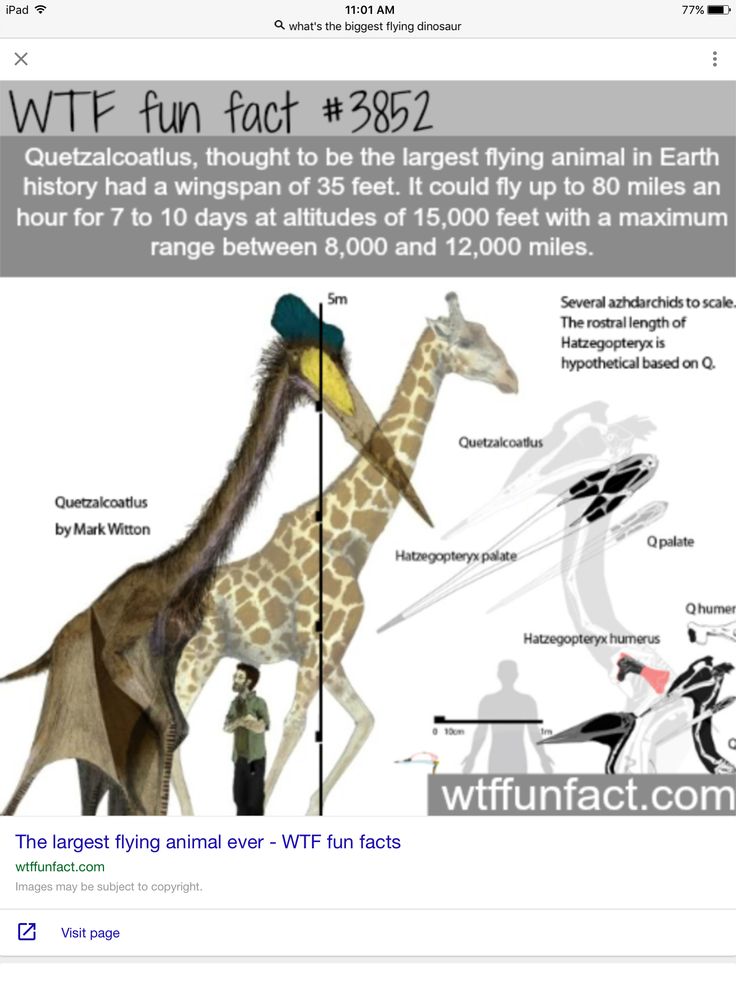

One of the largest pterosaurs is believed to be Quetzalcoatlus northropi, whose wingspan reached 36 feet (11 m), according to the journal PLOS One .

An artist illustration of Quetzalcoatlus northropi. (Image credit: Mark Witton/Darren Naish/ CC BY 3.0)Physical characteristics

Given the large number of different types of pterosaurs, the physical characteristics of the winged reptiles varied widely depending on the genera.

Pterosaurs often had long necks, which sometimes had throat pouches similar to pelicans' for catching fish. Most pterosaur skulls were long and full of needle like teeth. However, pterosaurs of the taxonomic family Azhdarchidae, which ruled the Late Cretaceous skies and included Quetzalcoatlus northropi, were toothless, according to the journal ZooKeys .

However, pterosaurs of the taxonomic family Azhdarchidae, which ruled the Late Cretaceous skies and included Quetzalcoatlus northropi, were toothless, according to the journal ZooKeys .

A distinguishing feature of pterosaurs was the crest on their heads. Though it was initially thought that pterosaurs had no crests, it's now known that crests were widespread across pterosaur genera and came in various forms.

For instance, some pterosaurs had big, bony crests, while other crests were fleshy with no underlying bone. Some pterosaurs even appear to have had a saillike crest made up of a membrane sheet connecting two large bones on the head. "We now know that pterosaur crests had all kinds of [bone and flesh] combinations," Hone told Live Science.

Over the years, scientists have proposed many possible purposes for these crests, including that they were used for heat regulation or to serve as rudders during flight. "But almost all of the hypotheses have failed the most basic tests," Hone said, adding that models show the crests aren't effective rudders and many small pterosaurs have crests even though they wouldn't have needed them to dissipate heat.

What seems most likely is that the crests were used for sexual selection, Hone and his colleagues argued in a 2011 study in the journal Lethaia .

There are several lines of evidence that support this function of the crests, Hone explained, perhaps most notably that juveniles, which look like miniature versions of adult pterosaurs, don't have crests, suggesting the structures are used for something that is only relevant to adults, such as mating.

What did pterosaurs eat?

Pterosaurs were carnivores, though some may have occasionally ate fruits, Hone said. What the reptiles ate depended on where they lived — some species spent their lives around water, while others were more terrestrial.

Terrestrial pterosaurs ate carcasses, baby dinosaurs, lizards, eggs, insects and various other animals. "They were probably fairly active hunters of small prey," Hone said. Water-loving pterosaurs ate a variety of marine life, including fish, squid, crab and other shellfish.

In 2014, Hone sought to learn more about the lives of marine pterosaurs. With these animals, juveniles dominate the fossil record, Hone said. This is odd because young animals are generally those that are targeted by predators, preventing them from becoming part of the fossil record.

One hypothesis to explain this strange occurrence is that the juvenile pterosaurs often died by drowning instead of being eaten. To test this, Hone and his colleague Donald Henderson modelled how well could pterosaurs float on water (like ducks). They found that pterosaurs floated well, but they had poor floating postures, in which their heads rested very close to the water, if not on the water.

This suggests that aquatic pterosaurs wouldn't spend much time on the water's surface and would launch into the air shortly after diving for food to avoid drowning. However, young pterosaurs that don't yet have strong muscles or are still learning to fly would have more difficulties launching back into the air from a dive, possibly resulting in drowning, Hone said.

Amongst the toothed species of pterosaur, researchers have discovered wear patterns on fossilised teeth that help to reveal their diets, according to Nature . For example, dimorphodon – a roughly 3 feet (1 meter) long pterosaur – had previously believed to be a fishing reptile, until dental evidence revealed wear patterns that would have been produced by eating insects and land vertebrates rather than marine life.

Additional resources

For more information about pterosaurs check out “Pterosaurs : Natural History, Evolution, Anatomy ”, by Mark P. Witton, “Age of Pterosaurs ” by Yang Yang and “Dinosaurs: New Visions of a Lost World ” by Michael J. Benton.

Bibliography

Natalia Jagielska and Stephen L. Brusatte, “Pterosaurs”, Volume 31, Current biology, August 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.06.086

David M. Martill, “The early history of pterosaur discovery in Great Britain”, Geological Society, London,Volume 343, January 2010, https://doi. org/10.1144/SP343.18

org/10.1144/SP343.18

David M.Martill and David M.Unwin, “The world’s largest toothed pterosaur, NHMUK R481, an incomplete rostrum of Coloborhynchus capito (Seeley, 1870) from the Cambridge Greensand of England”, Cretaceous Research, Volume 34, April 2012, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2011.09.003

Armand J. de Ricqlès, et al, “Palaeohistology of the bones of pterosaurs (Reptilia: Archosauria): anatomy, ontogeny, and biomechanical implications”, Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, Volume 126, July 2000, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.2000.tb00016.x

David Hone, et al, “Does mutual sexual selection explain the evolution of head crests in pterosaurs and dinosaurs?”, Lethaia, Volume 45, April 2012, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1502-3931.2011.00300.x

Joseph Bennington-Castro is a Hawaii-based contributing writer for Live Science and Space.com. He holds a master's degree in science journalism from New York University, and a bachelor's degree in physics from the University of Hawaii. His work covers all areas of science, from the quirky mating behaviors of different animals, to the drug and alcohol habits of ancient cultures, to new advances in solar cell technology. On a more personal note, Joseph has had a near-obsession with video games for as long as he can remember, and is probably playing a game at this very moment.

His work covers all areas of science, from the quirky mating behaviors of different animals, to the drug and alcohol habits of ancient cultures, to new advances in solar cell technology. On a more personal note, Joseph has had a near-obsession with video games for as long as he can remember, and is probably playing a game at this very moment.

which dinosaur can fly

Are there any dinosaurs that can fly?

The best hotel to...

Please enable JavaScript

The best hotel to get free nights loyalty program rewards in Dubai

They were pterosaurs which included plesiosaur, pteranodon, pterodactyl, dimorphodon, rhamphorhynchus, quetzalcolus and many others. (pronounced TER-o-SAWRS) Pterosaurs (meaning "winged lizard") were prehistoric flying reptiles. nine0007

Which dinosaurs had wings?

Pterodactyl flew with the help of wings formed by a rigid thin membrane that stretched along the body to an elongated ring finger. Like birds, pterosaurs had light, hollow bones. Pterosaur skeletons only survive as fossils when their bodies rest in a highly protected environment.

Like birds, pterosaurs had light, hollow bones. Pterosaur skeletons only survive as fossils when their bodies rest in a highly protected environment.

What is the largest flying dinosaur?

Quetzalcoatl Quetzalcoatl

The extinction wiped out everything else, leaving only the bird dinosaurs.

The extinction wiped out everything else, leaving only the bird dinosaurs.  rex or colloquially T-Rex, is one of the best represented of these large theropods. Tyrannosaurus rex lived in what is now western North America, on what was then an island continent known as Laramidia. nine0007

rex or colloquially T-Rex, is one of the best represented of these large theropods. Tyrannosaurus rex lived in what is now western North America, on what was then an island continent known as Laramidia. nine0007  … Paleontologists have suggested that the fossil eggs in the Burning Rocks were laid by Protoceratops because it was the most common dinosaur in the area where the eggs were found.

… Paleontologists have suggested that the fossil eggs in the Burning Rocks were laid by Protoceratops because it was the most common dinosaur in the area where the eggs were found.

Their bodies are streamlined, as if for flight, so they still cut through the water cleanly. ... There was no way they could fly with such short wings and heavy bodies.

Their bodies are streamlined, as if for flight, so they still cut through the water cleanly. ... There was no way they could fly with such short wings and heavy bodies.  Emus were once able to fly , but evolutionary adaptation has since robbed them of this gift. A cursory glance at the emu suggests that it is too heavy to fly, but the reasons for this are more complex.

Emus were once able to fly , but evolutionary adaptation has since robbed them of this gift. A cursory glance at the emu suggests that it is too heavy to fly, but the reasons for this are more complex.  Another dinosaur, Ceratosaurus, was likely able to swim and catch aquatic prey such as fish and crocodiles.

Another dinosaur, Ceratosaurus, was likely able to swim and catch aquatic prey such as fish and crocodiles.  … Longrich discovered a Tyrannosaurus rex fossil with large tooth notches.

… Longrich discovered a Tyrannosaurus rex fossil with large tooth notches.  ". Beth Shapiro, an evolutionary molecular biologist and professor at the Institute of Genomics at the University of California, Santa Cruz, echoed this view. Because no dinosaur DNA survived, she told Newsweek, "there will be no dinosaur clones."

". Beth Shapiro, an evolutionary molecular biologist and professor at the Institute of Genomics at the University of California, Santa Cruz, echoed this view. Because no dinosaur DNA survived, she told Newsweek, "there will be no dinosaur clones."  " nine0007

" nine0007  Because both dromaeosaurids and birds are in Group Paraves are dinosaurs, such a comparison is quite justified.

Because both dromaeosaurids and birds are in Group Paraves are dinosaurs, such a comparison is quite justified.  In this dinosaur, flight was provided not only by the forelimbs (actual wings), but also by the hind limbs. It is believed, however, that he rather planned from branch to branch than actively flew. nine0007

In this dinosaur, flight was provided not only by the forelimbs (actual wings), but also by the hind limbs. It is believed, however, that he rather planned from branch to branch than actively flew. nine0007  The authors tend to believe that it was consistent. If this is true, then the microraptor most likely relied for survival (search for food and protection from enemies) on flight - moreover, on a real flywheel, and not on planning over short distances, which is usually attributed to it. Randomly changing feathers would allow for gliding, but not well suited for active flight, which requires wing symmetry. nine0007

The authors tend to believe that it was consistent. If this is true, then the microraptor most likely relied for survival (search for food and protection from enemies) on flight - moreover, on a real flywheel, and not on planning over short distances, which is usually attributed to it. Randomly changing feathers would allow for gliding, but not well suited for active flight, which requires wing symmetry. nine0007