Do kids learn to read in kindergarten

When Your Child Doesn't Learn to Read in Kindergarten

My son is in Kindergarten this year. It’s now May and I have watched him struggle with learning to read.

If you’ve been reading my blog posts this past year, you’ll know that I’m a big proponent of phonics-based early reading instruction. I taught K-2 for a number of years, have presented teacher professional development on early reading, and worked with countless students who were struggling readers.

I have a strong background in early reading instruction.

There are a couple of reasons why my son hasn’t learned to read in Kindergarten this past year. Partly he’s just a six-year-old boy, who would rather play than read, and is not really interested in school yet.

The other part is that he just needs some solid, consistent instruction in reading, which he hasn’t gotten this year at school. In a way, I’m okay with the fact that the reading instruction hasn’t been solid because he’s not ready for it.

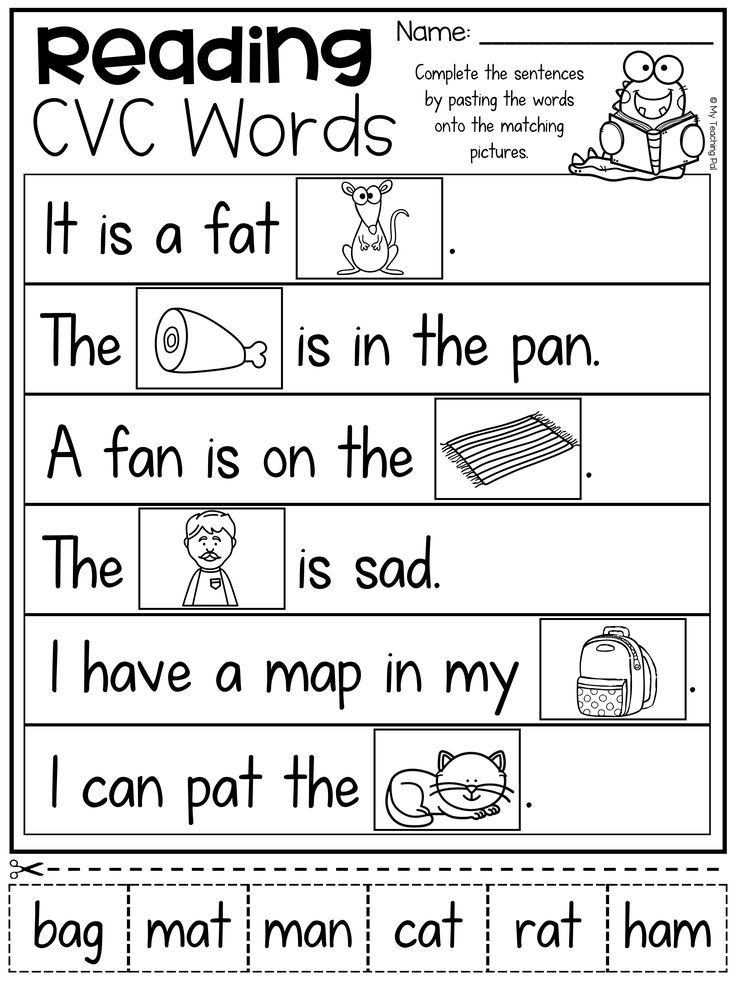

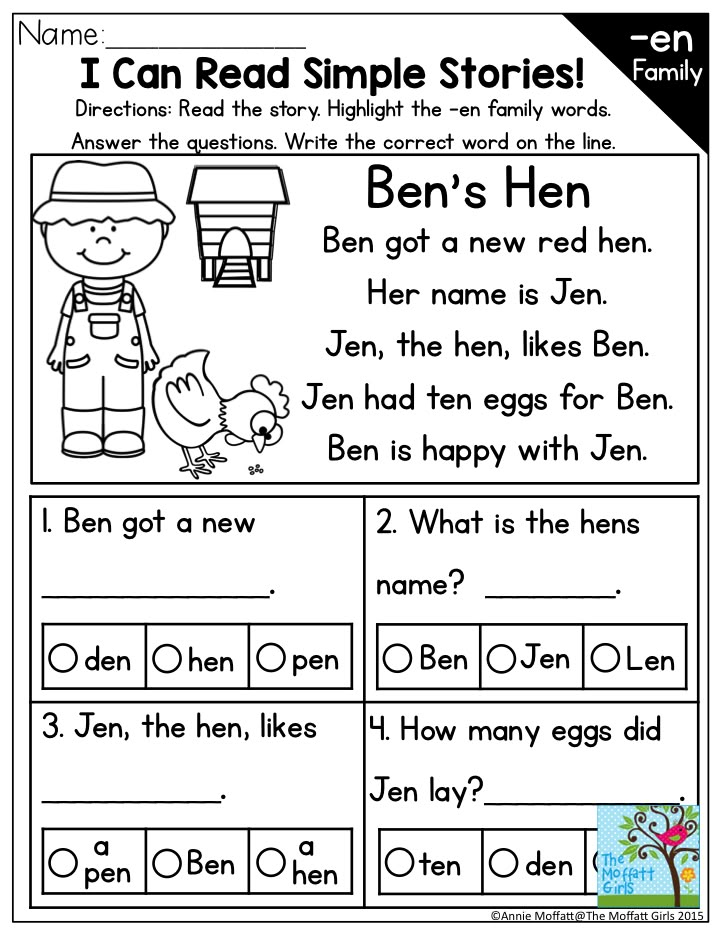

The strange thing is that, as a teacher and a former Kindergarten teacher, I know what he needs. I know exactly what sounds he knows and doesn’t know. I know that he cannot smoothly blend some CVC words, especially those with stop sounds. He knows all of his continuous sounds, but still struggles to remember the stop sounds. I know that he needs to work on his phonemic awareness skills.

I know all of these things and at the same time, I have not provided systematic instruction at home for him this past year.

I am pulled in two directions.

In August of this past school year, my son asked me to teach him to read. If only it were that simple. I think he expected to learn how to read quickly and it was something I could teach him easily, like within a day or two.

At the time I knew he wasn’t ready yet. He didn’t know many of his sounds and lacked quite a few phonemic awareness skills that needed to be in place first.

The teacher-part of me wants to create a scope and sequence of instruction that will meet his needs and push him to the next level in reading. I can totally do that. I know how to do it and I can create or find the resources I need to teach him to read.

I can totally do that. I know how to do it and I can create or find the resources I need to teach him to read.

The teacher in me feels like I am somehow failing him by not teaching him to read.

As a parent, I want to see him love school. That is the most important thing for me. I had a love/hate relationship with school myself (it was too easy for me) and my husband disliked school (it was boring). I want school to be a safe, comfortable place for my son to spend 6+ hours a day for 13+ years of his life. I don’t want him to feel anxious or stressed about not performing well enough.

My son has gone through his Kindergarten year and continually voiced to me that he doesn’t like school. His reason? It’s boring. We all know that school is not built for boys, especially little boys who like to run, jump, and wrestle rather than sit still in a classroom. My son does not have a learning disability, nor does he have ADHD. He excels in math. He can tell elaborate stories and wants me to document them. He understands everything read aloud to him and asks great questions when he doesn’t. He can sit still when he needs to do so.

He understands everything read aloud to him and asks great questions when he doesn’t. He can sit still when he needs to do so.

He would be considered behind by normal, traditional Kindergarten standards. But, I also know the research. Most kids learn to read between the ages of 4-7 and some do not until age 8. If kids don’t learn to read in Kindergarten, they’re not behind. They don’t have a learning disability, although some may. They just may not be ready to or interested in reading yet. It’s okay if he doesn’t learn to read until he’s 7 or 8. That doesn’t mean that he’s not learning.

I am pulled in two directions. The teacher in me knows how to provide systematic instruction at home that could meet his reading needs and the parent side of me that wants him to love learning. Are those two things isolated? No, but when he comes home tired from school the last thing I want to do is make him sit down and do more “school stuff.”

He can run faster than any kid in his class. He’s very proud of that.

He’s very proud of that.

He can create elaborate, imaginative stories. He’s always asking us for the paper to draw them out.

He can create whole cities in MindCraft. That’s a lot of geometric and spatial thinking.

He excels in math and can think outside of the box when solving problems.

He’s happy, even though he doesn’t like school. It’s not a bad place for him. It’s just not as fun as playing with Legos, engaging in pretend-play with his friends, or climbing trees. That’s okay for now. At least it’s not a struggle to get him to go to school.

Thankfully, we chose a school for him that does not push academics over social and emotional development. At my son’s school, it’s okay that he’s not reading at the end of Kindergarten. He’s not looked down upon and he doesn’t feel shamed for not reading.

He has learned and grown so much this past year. No, he hasn’t learned to read, but he’s learned other life skills that he will take with him when he leaves Kindergarten.

We have done very few academic things after school. I have tried to work with him in the afternoons, but he is so tired. It’s a struggle to get him to concentrate, focus and sit still. No, he’s doesn’t have ADHD. Not even close. He’s just a six-year-old boy who is tired from a long day at school and can’t concentrate on more reading work at home. It has been difficult for me to be consistent while working with him at home.

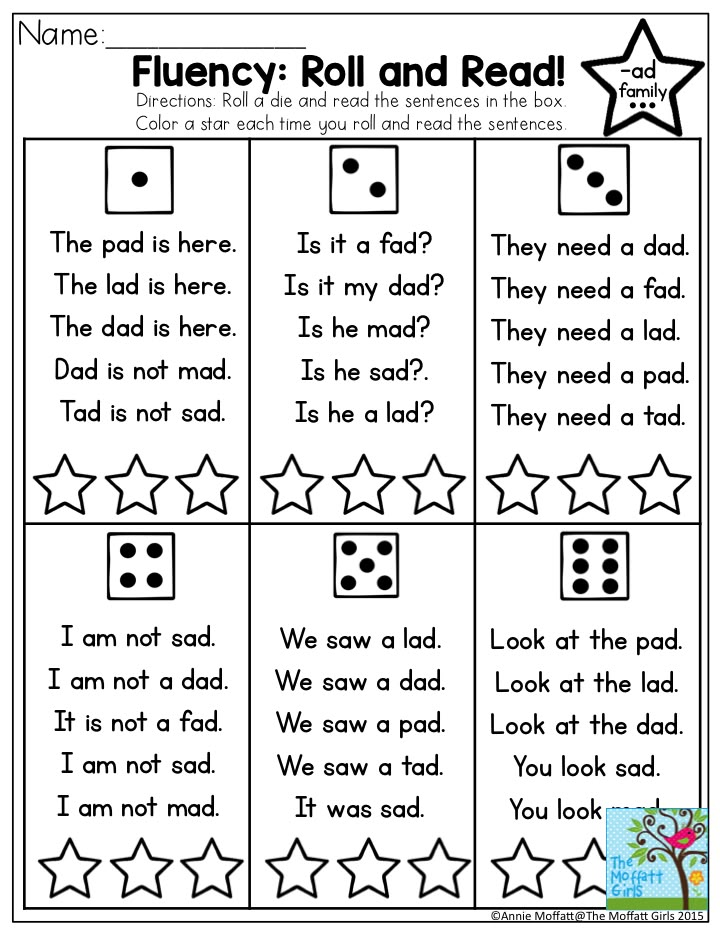

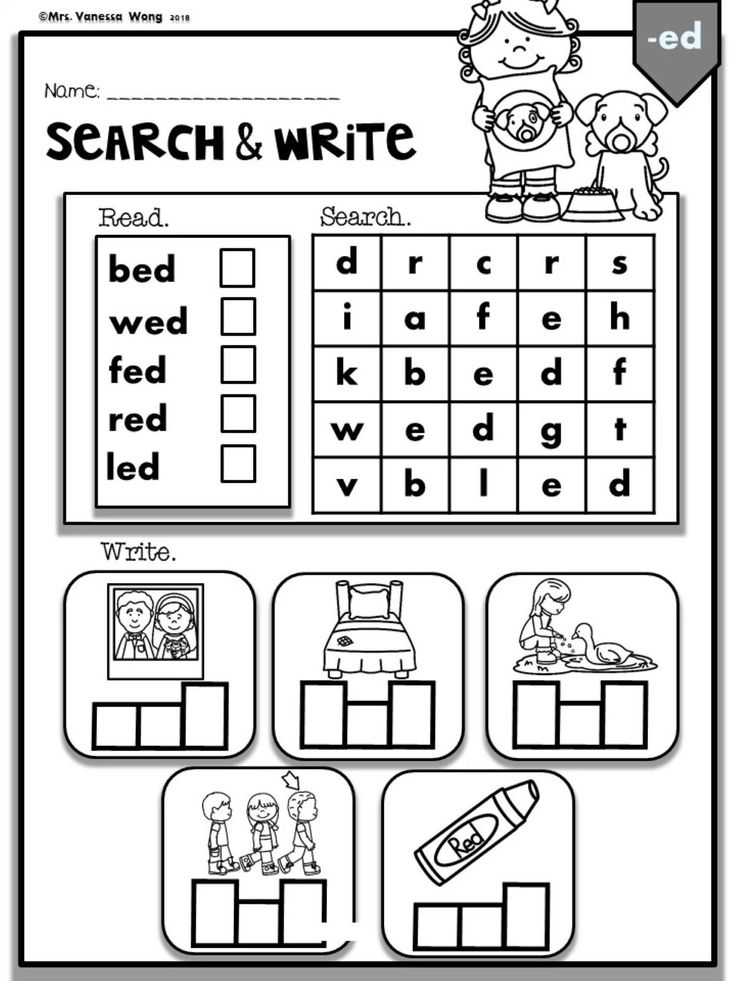

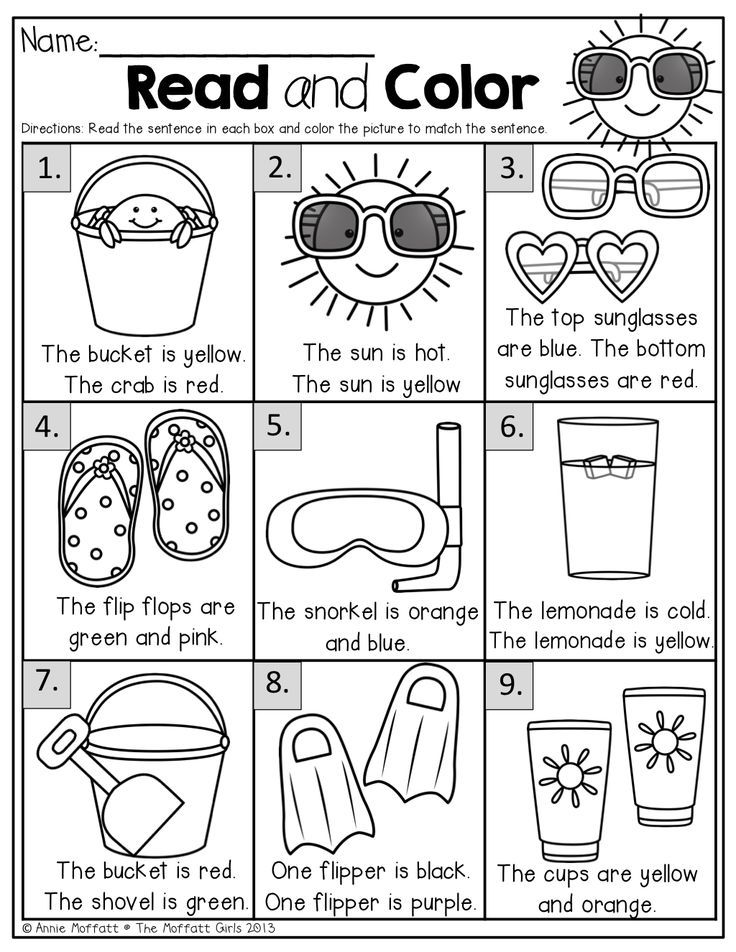

What do we do after school? At the beginning of the year, I worked in fun word-play and phonemic awareness activities throughout the afternoon. These were not formal lessons, but just oral sound play.

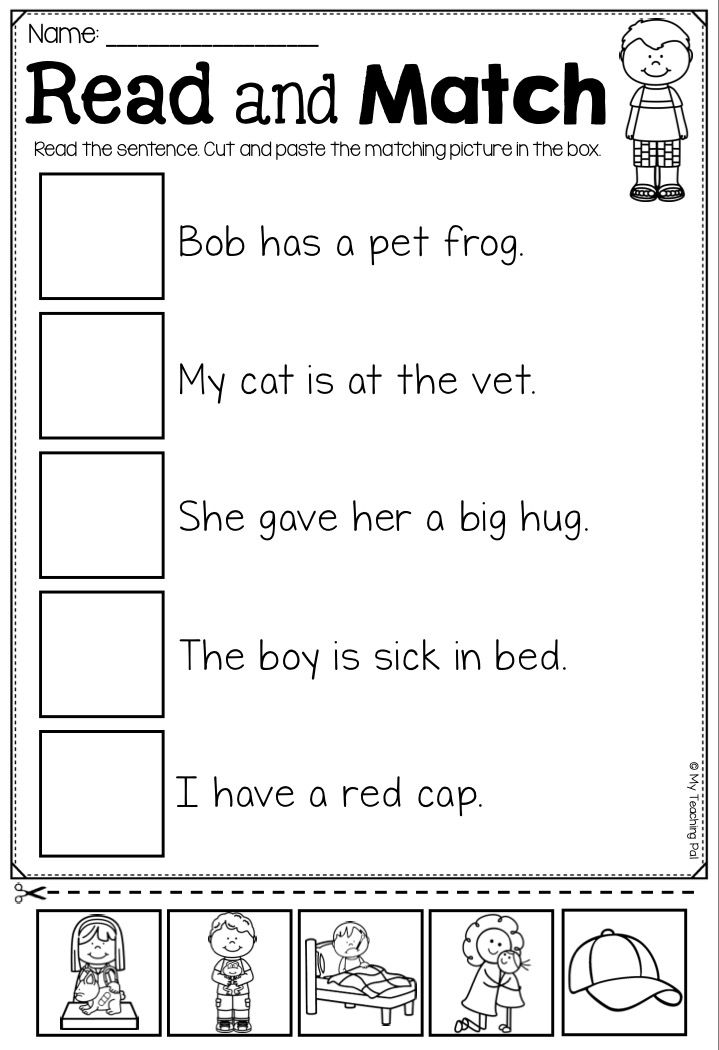

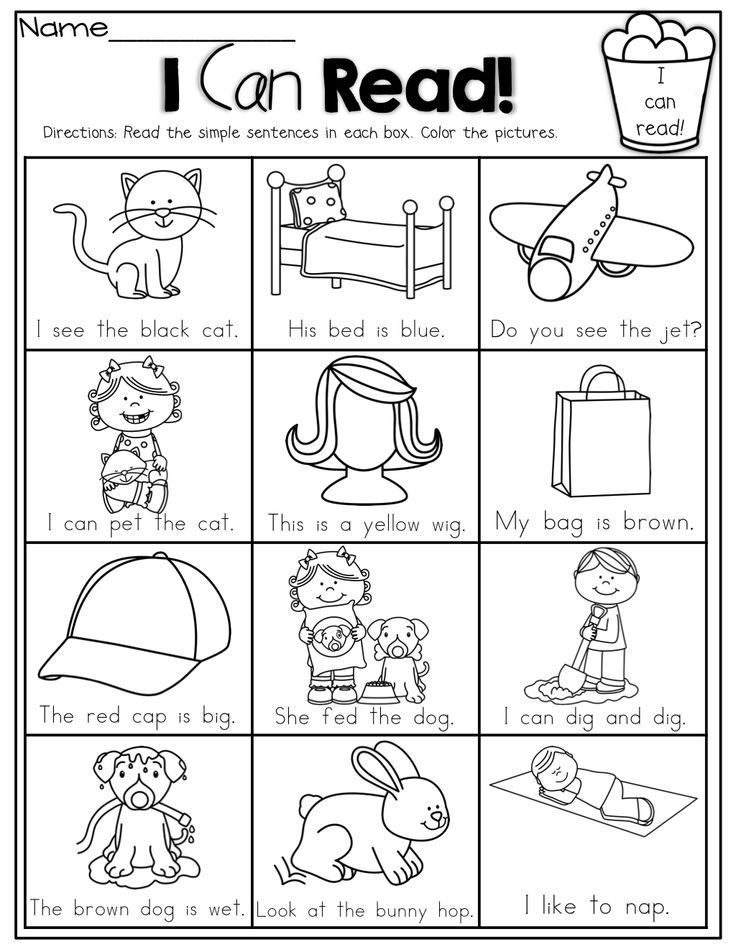

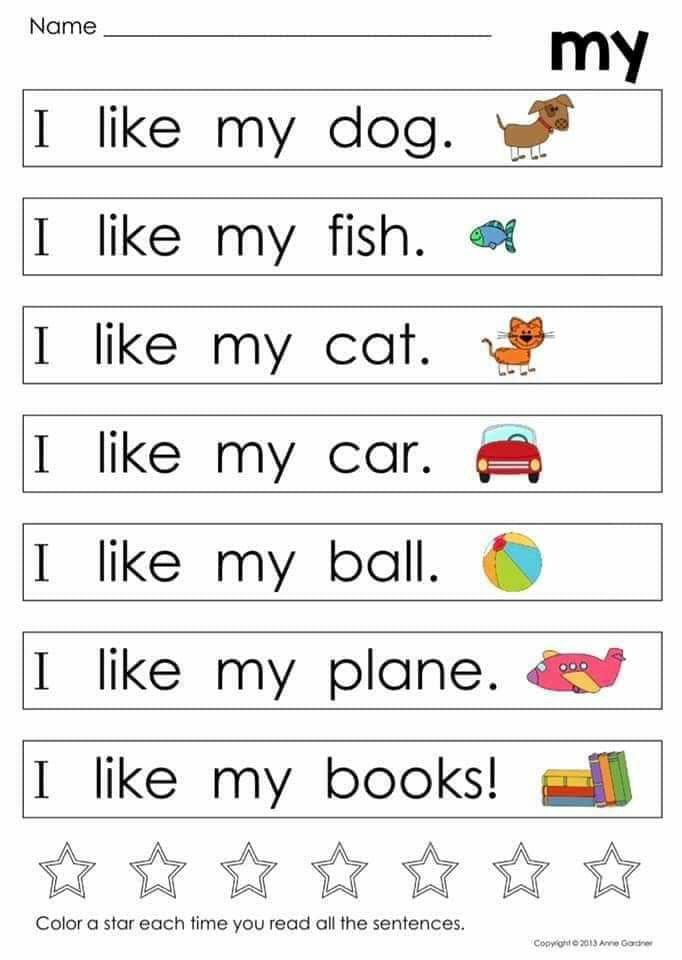

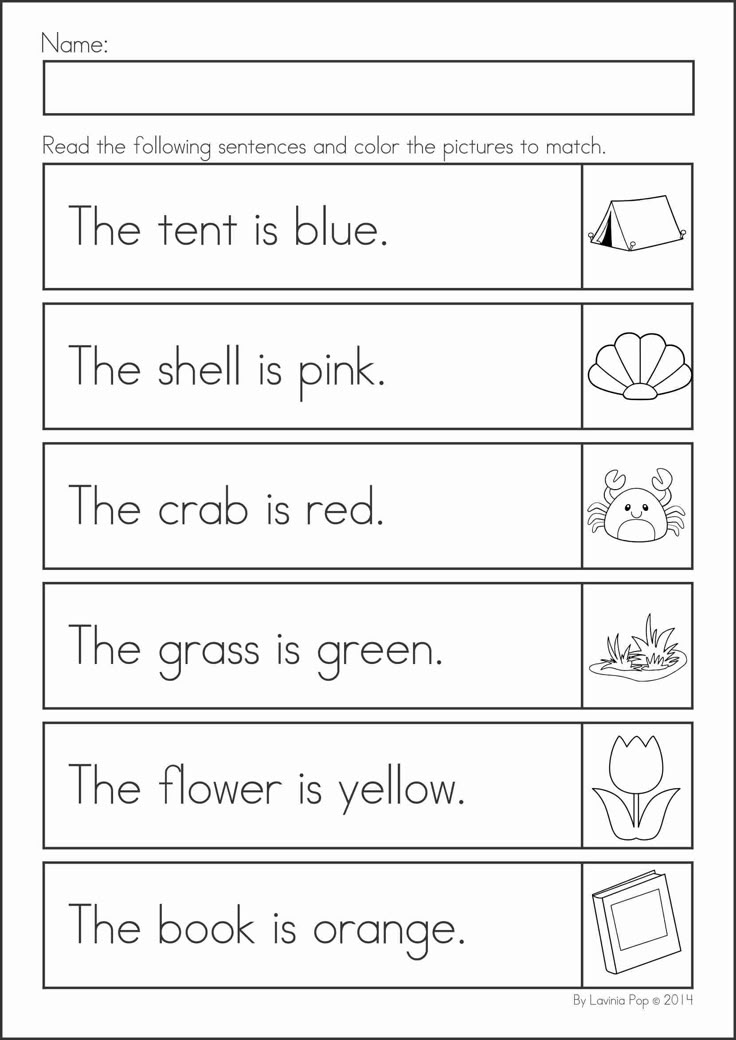

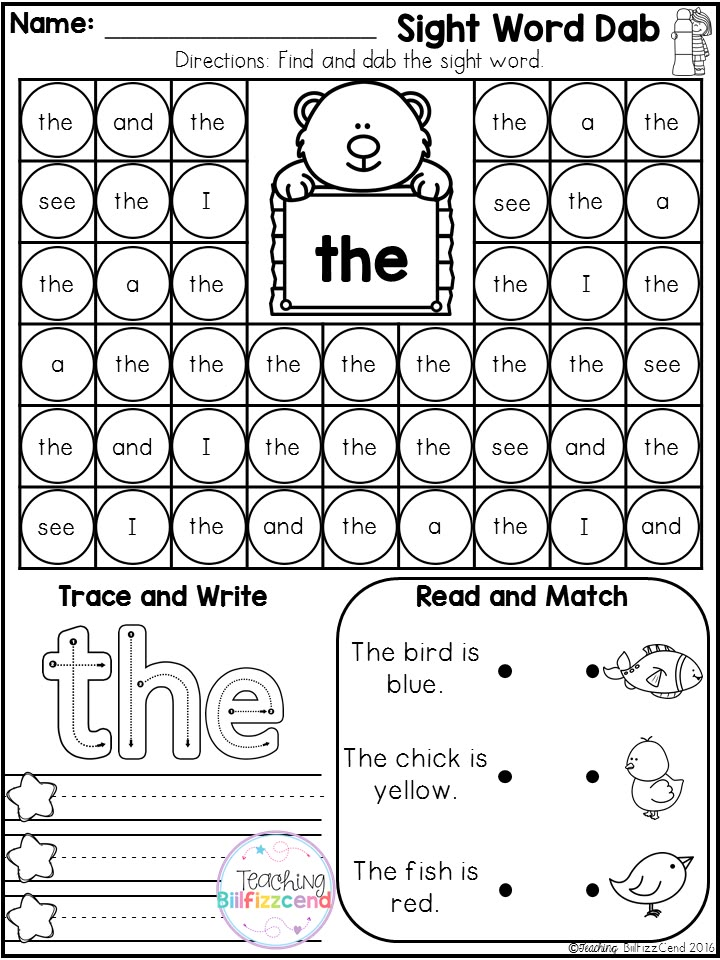

Now, we work on blending sounds using these blending cards. I developed these CVC Cut & Paste Worksheets & Phonics Cards that we do once a week or so. I love that we can do the worksheet and I can make them into a ring of review cards.

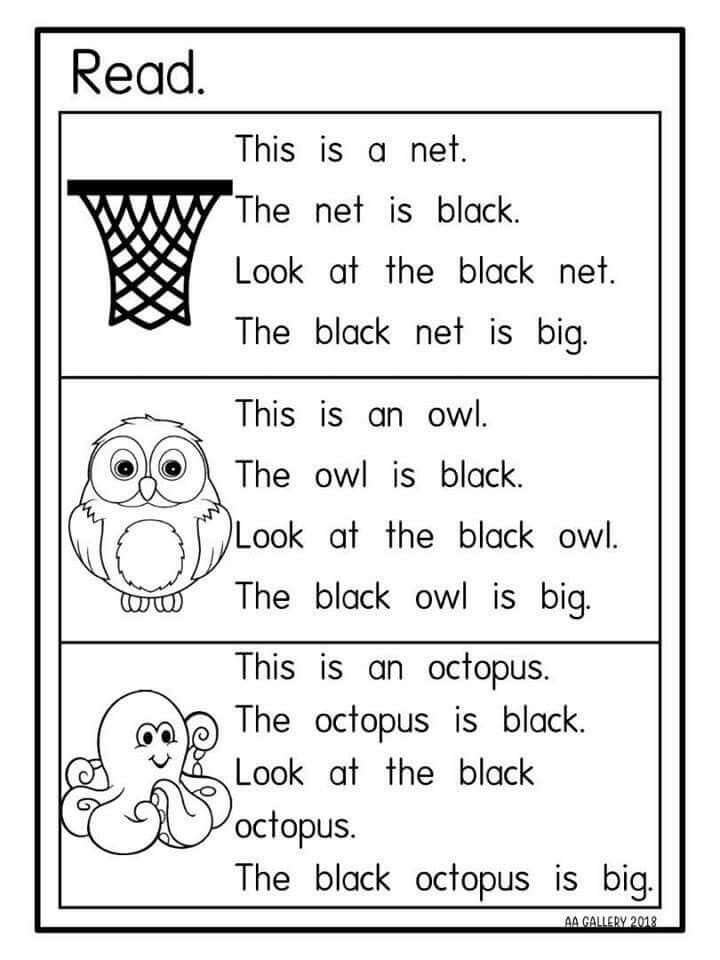

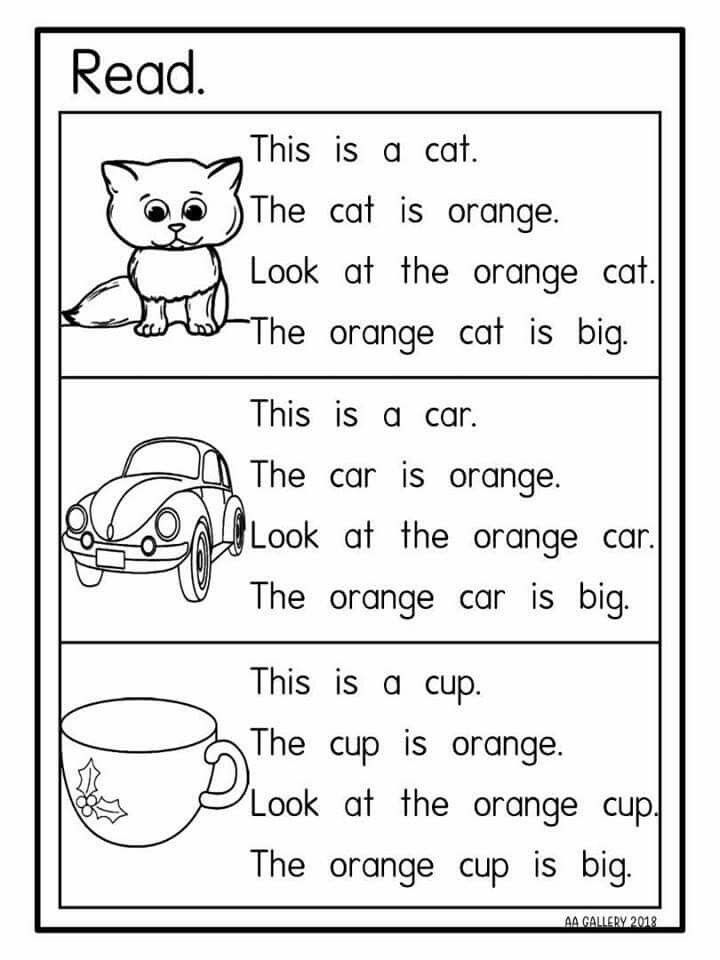

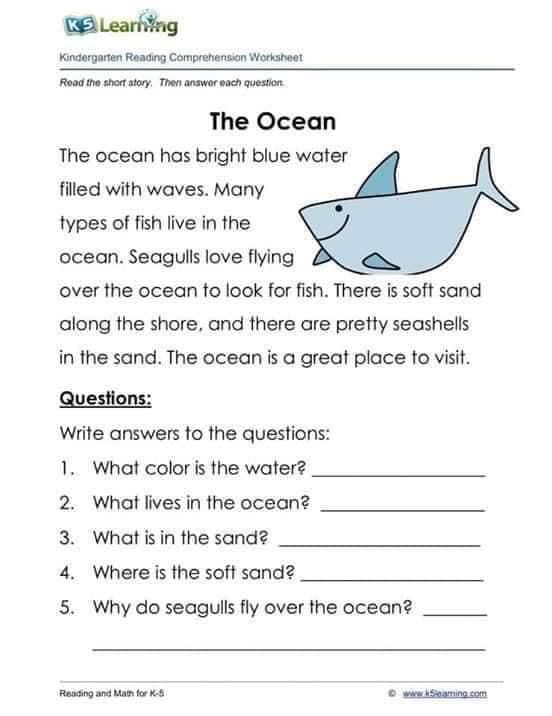

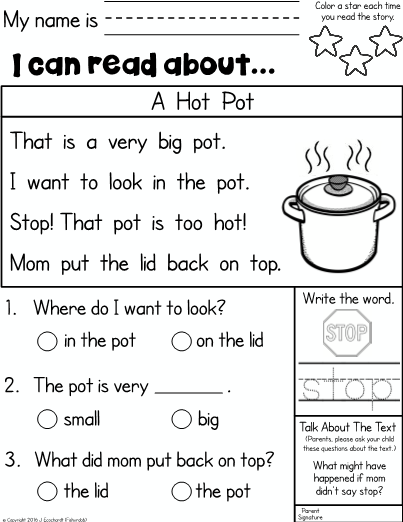

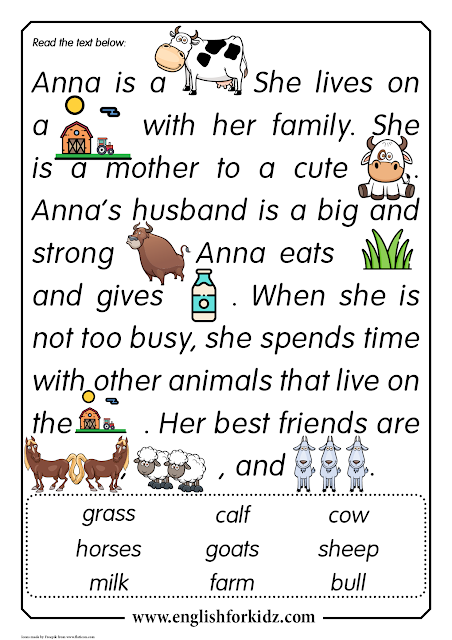

I have put together some reading passages that are highly controlled for cvc word family and sight words. We have just started working on these reading passages and will continue them throughout the summer.

We have just started working on these reading passages and will continue them throughout the summer.

I’ve also started using a computerized program that is geared toward homeschool families called Funnix. It requires that an adult sit with the child to make sure he is pronouncing the sounds correctly and following the program. It does a really good job teaching reading without a lot of teacher prep and materials. As a reading teacher, I can see that it addresses all the important components of reading at just the right pace.

While we do a lot at home, one thing I am not is consistent.

My son is in school all morning long (it’s half-day Kindergarten). He comes home tired. I want him to love learning and pushing him to do reading after school every day has been a struggle. So, we are not consistent in our work at home. Come summer, we’ll concentrate on it much more when he’s less tired from school.

Give your child time. Some children just need a little more time.

While you’re waiting, observe. Watch your child and see if they have a learning disability or if they need some intervention that you or their teacher can provide.

Can they learn what they are taught in other academic areas? Are they imaginative? Do they want to tell you stories and interact with you about the world around them? Are they making friends? Do they like school?

Learning how to read used to be taught in first grade. We, as a society, have pushed learning to read down to Kindergarten. There’s nothing wrong with teaching reading in Kindergarten. On the same token, there’s nothing wrong with a Kindergartener who doesn’t learn to read.

I wrote another blog post about my son learning to read. It’s been two years since I wrote this original post and I’ve had a few commenters ask about how he’s doing now. This blog post, When Your Child Struggles with Reading, is about where we are now, two years later.

Teaching children to read isn’t easy. How do kids actually learn to read?

A student in a Mississippi elementary school reads a book in class. Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger Report

Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger ReportTeaching kids to read isn’t easy; educators often feel strongly about what they think is the “right” way to teach this essential skill. Though teachers’ approaches may differ, the research is pretty clear on how best to help kids learn to read. Here’s what parents should look for in their children’s classroom.

How do kids actually learn how to read?

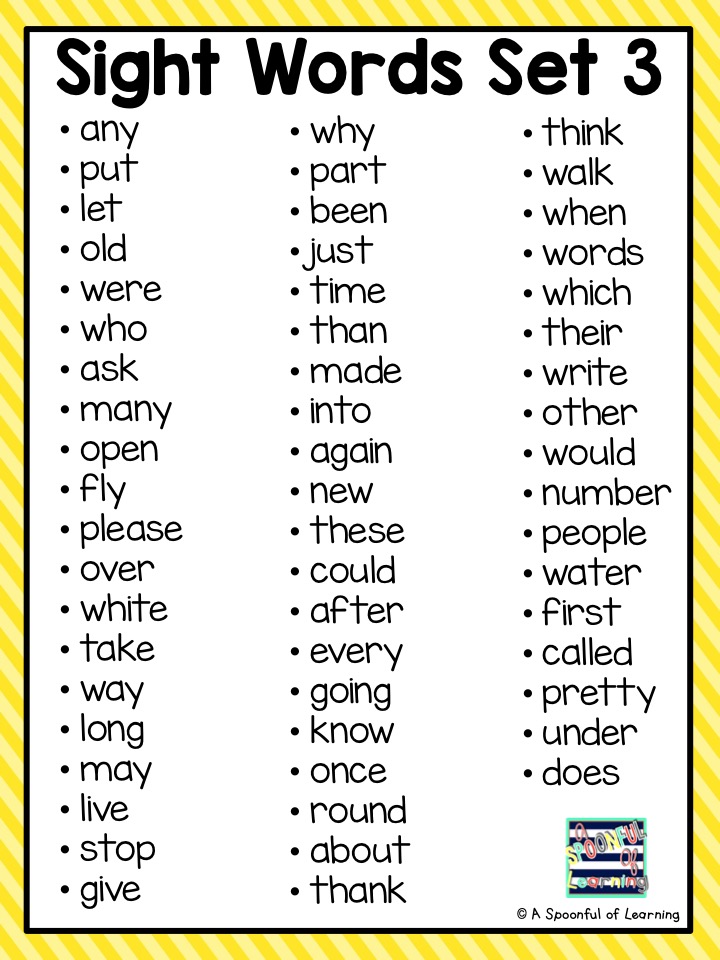

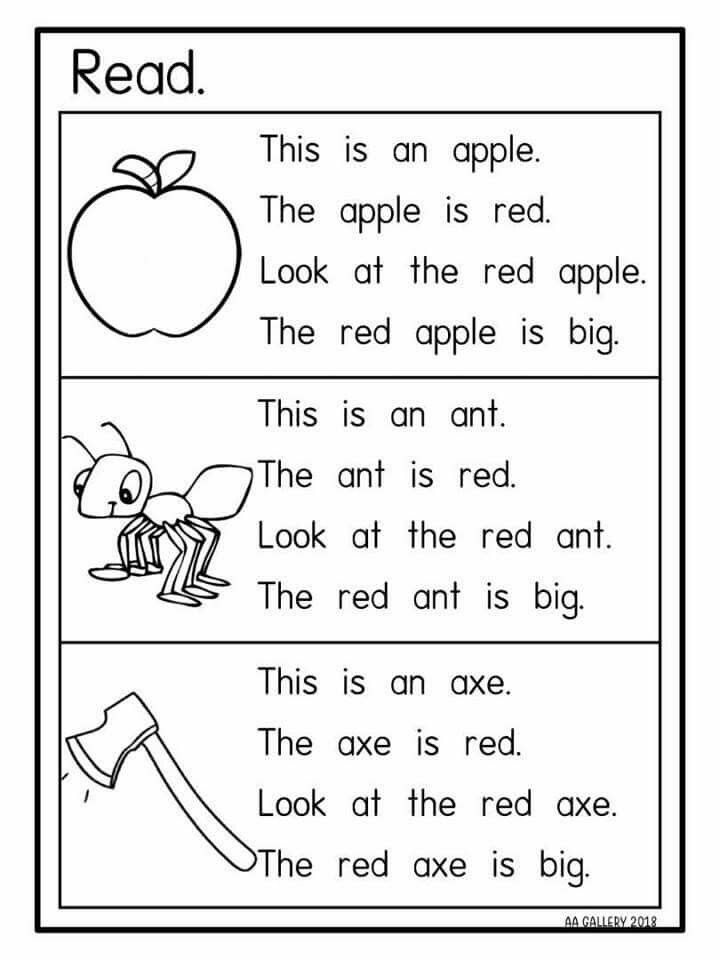

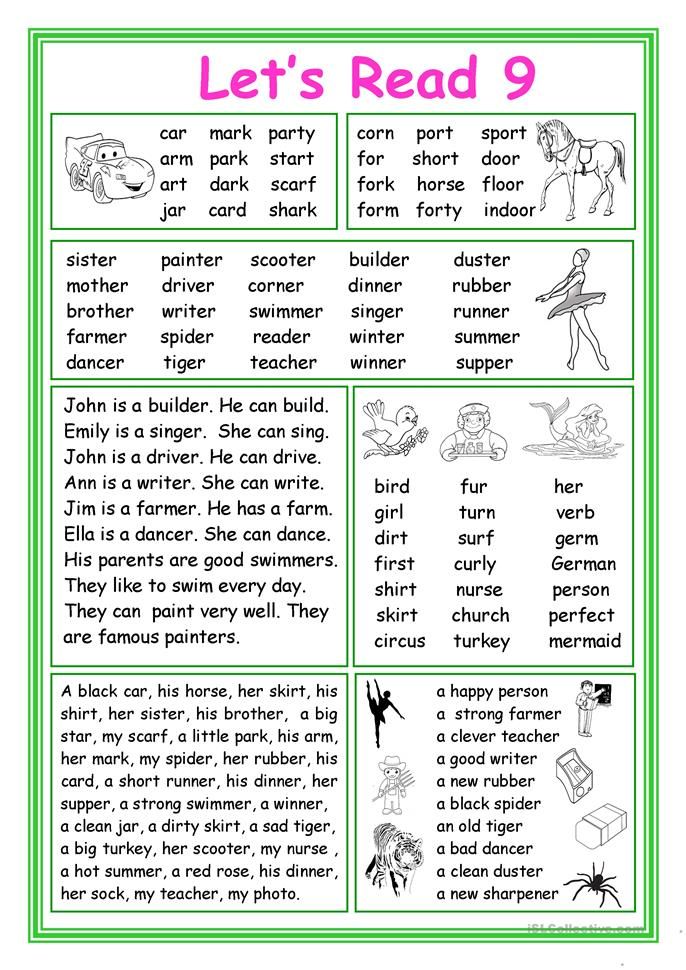

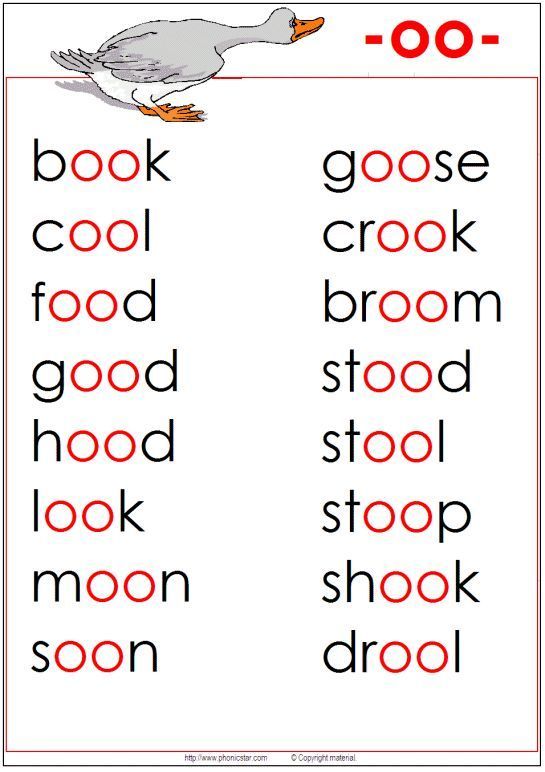

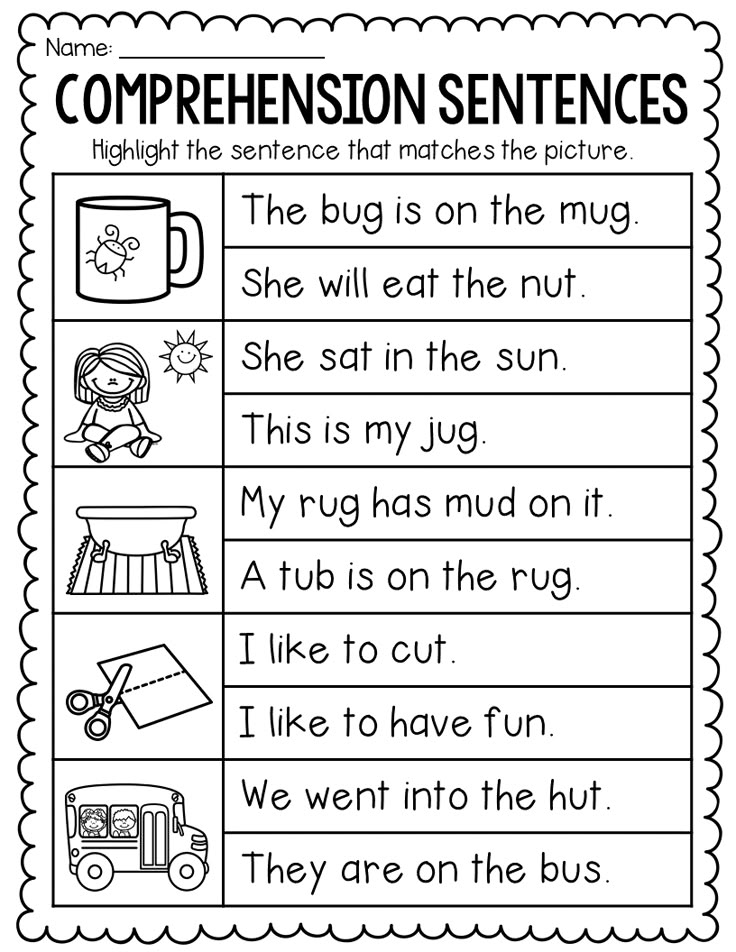

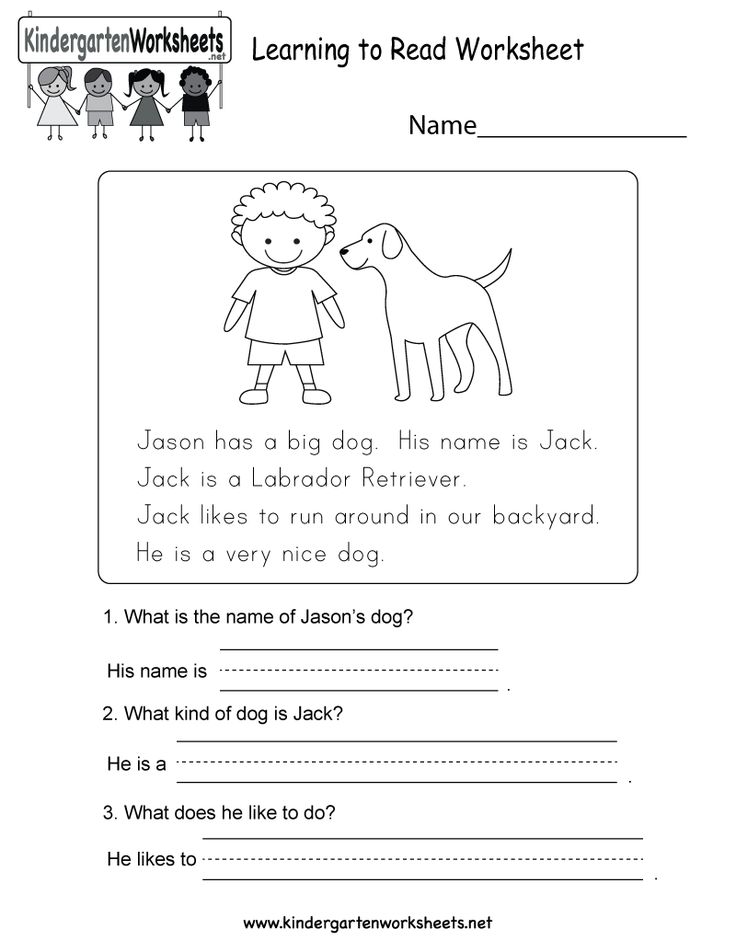

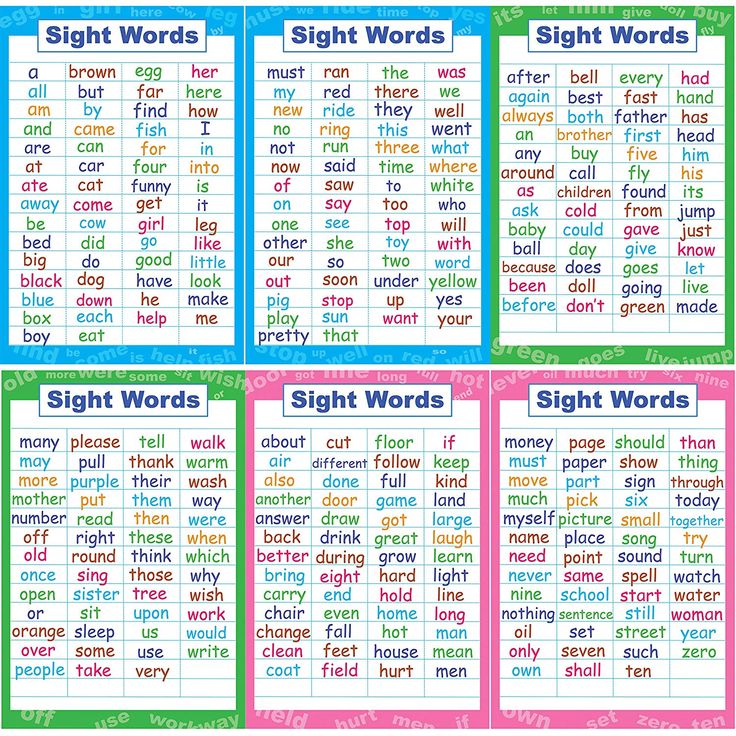

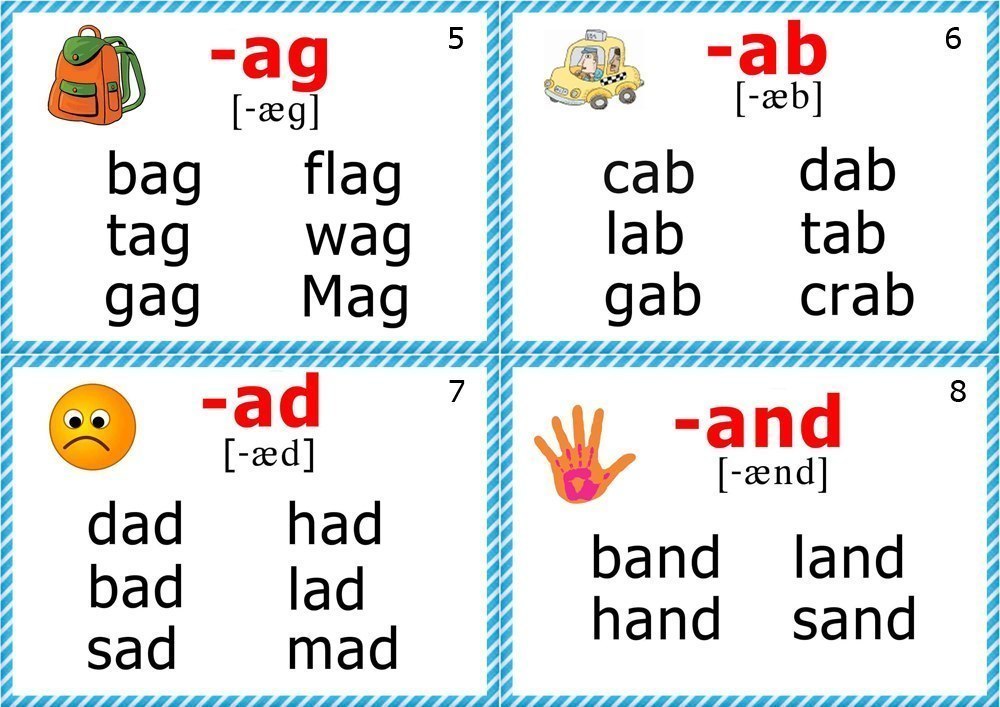

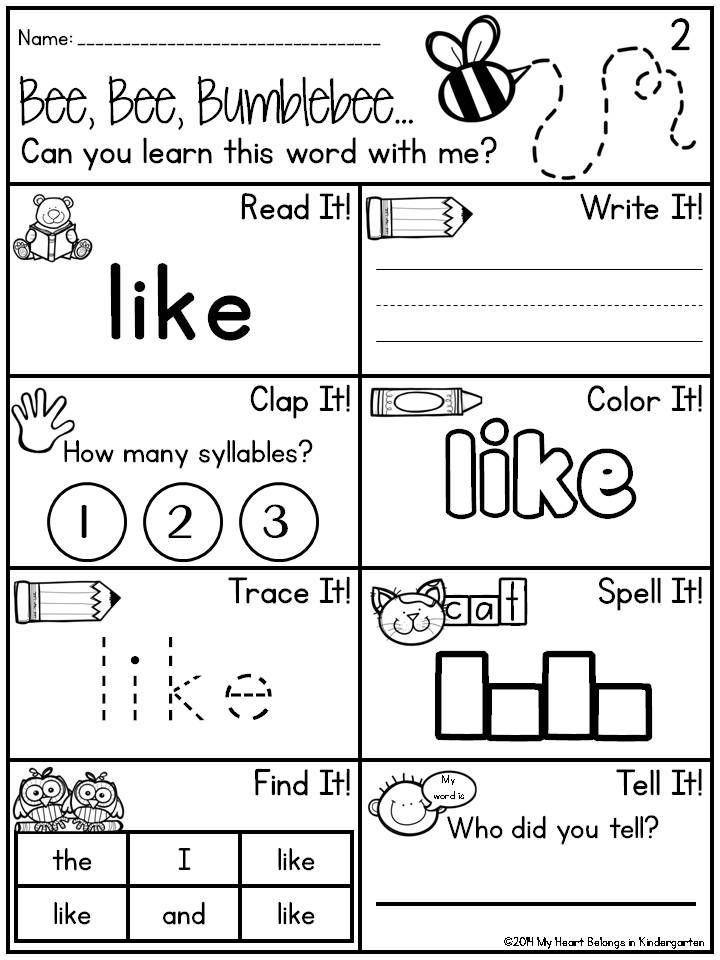

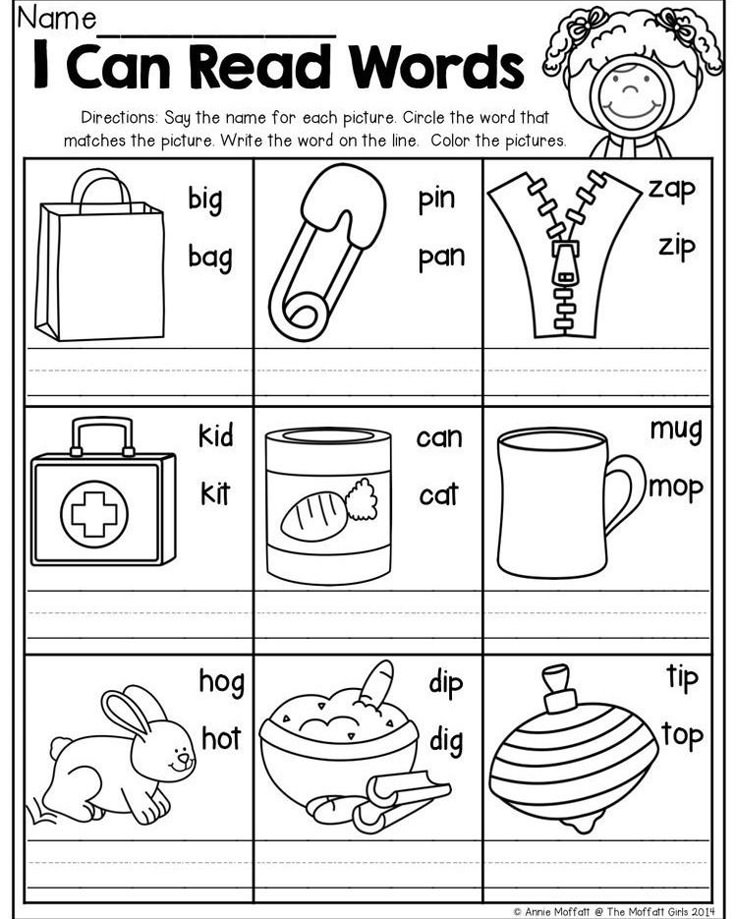

Research shows kids learn to read when they are able to identify letters or combinations of letters and connect those letters to sounds. There’s more to it, of course, like attaching meaning to words and phrases, but phonemic awareness (understanding sounds in spoken words) and an understanding of phonics (knowing that letters in print correspond to sounds) are the most basic first steps to becoming a reader.

If children can’t master phonics, they are more likely to struggle to read. That’s why researchers say explicit, systematic instruction in phonics is important: Teachers must lead students step by step through a specific sequence of letters and sounds. Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

That’s why researchers say explicit, systematic instruction in phonics is important: Teachers must lead students step by step through a specific sequence of letters and sounds. Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

How should your child’s school teach reading?

Timothy Shanahan, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago and an expert on reading instruction, said phonics are important in kindergarten through second grade and phonemic awareness should be explicitly taught in kindergarten and first grade. This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

The wars over how to teach reading are back. Here’s the four things you need to know.

Wiley Blevins, an author and expert on phonics, said a good test parents can use to determine whether a child is receiving research-based reading instruction is to ask their child’s teacher how reading is taught. “They should be able to tell you something more than ‘by reading lots of books’ and ‘developing a love of reading.’ ” Blevins said. Along with time dedicated to teaching phonics, Blevins said children should participate in read-alouds with their teacher to build vocabulary and content knowledge. “These read-alouds must involve interactive conversations to engage students in thinking about the content and using the vocabulary,” he said. “Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

“Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

Rasmussen’s school uses a structured approach: Children receive lessons in phonemic awareness, phonics, pre-writing and writing, vocabulary and repeated readings. Research shows this type of “systematic and intensive” approach in several aspects of literacy can turn children who struggle to read into average or above-average readers.

What should schools avoid when teaching reading?

Educators and experts say kids should be encouraged to sound out words, instead of guessing. “We really want to make sure that no kid is guessing,” Rasmussen said. “You really want … your own kid sounding out words and blending words from the earliest level on.” That means children are not told to guess an unfamiliar word by looking at a picture in the book, for example. As children encounter more challenging texts in later grades, avoiding reliance on visual cues also supports fluent reading. “When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

“When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

Related: Teacher Voice: We need phonics, along with other supports, for reading

Blevins and Shanahan caution against organizing books by different reading levels and keeping students at one level until they read with enough fluency to move up to the next level. Although many people may think keeping students at one level will help prevent them from getting frustrated and discouraged by difficult texts, research shows that students actually learn more when they are challenged by reading materials.

Blevins said reliance on “leveled books” can contribute to “a bad habit in readers.” Because students can’t sound out many of the words, they rely on memorizing repeated words and sentence patterns, or on using picture clues to guess words. Rasmussen said making kids stick with one reading level — and, especially, consistently giving some kids texts that are below grade level, rather than giving them supports to bring them to grade level — can also lead to larger gaps in reading ability.

How do I know if a reading curriculum is effective?

Some reading curricula cover more aspects of literacy than others. While almost all programs have some research-based components, the structure of a program can make a big difference, said Rasmussen. Watching children read is the best way to tell if they are receiving proper instruction — explicit, systematic instruction in phonics to establish a foundation for reading, coupled with the use of grade-level texts, offered to all kids.

Parents who are curious about what’s included in the curriculum in their child’s classroom can find sources online, like a chart included in an article by Readingrockets.org which summarizes the various aspects of literacy, including phonics, writing and comprehension strategies, in some of the most popular reading curricula.

Blevins also suggested some questions parents can ask their child’s teacher:

- What is your phonics scope and sequence?

“If research-based, the curriculum must have a clearly defined phonics scope and sequence that serves as the spine of the instruction. ” Blevins said.

” Blevins said.

- Do you have decodable readers (short books with words composed of the letters and sounds students are learning) to practice phonics?

“If no decodable or phonics readers are used, students are unlikely to get the amount of practice and application to get to mastery so they can then transfer these skills to all reading and writing experiences,” Blevins said. “If teachers say they are using leveled books, ask how many words can students sound out based on the phonics skills (teachers) have taught … Can these words be fully sounded out based on the phonics skills you taught or are children only using pieces of the word? They should be fully sounding out the words — not using just the first or first and last letters and guessing at the rest.”

- What are you doing to build students’ vocabulary and background knowledge? How frequent is this instruction? How much time is spent each day doing this?

“It should be a lot,” Blevins said, “and much of it happens during read-alouds, especially informational texts, and science and social studies lessons. ”

”

- Is the research used to support your reading curriculum just about the actual materials, or does it draw from a larger body of research on how children learn to read? How does it connect to the science of reading?

Teachers should be able to answer these questions, said Blevins.

What should I do if my child isn’t progressing in reading?

When a child isn’t progressing, Blevins said, the key is to find out why. “Is it a learning challenge or is your child a curriculum casualty? This is a tough one.” Blevins suggested that parents of kindergarteners and first graders ask their child’s school to test the child’s phonemic awareness, phonics and fluency.

Parents of older children should ask for a test of vocabulary. “These tests will locate some underlying issues as to why your child is struggling reading and understanding what they read,” Blevins said. “Once underlying issues are found, they can be systematically addressed. ”

”

“We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs. But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York

Rasmussen recommended parents work with their school if they are concerned about their children’s progress. By sitting and reading with their children, parents can see the kind of literacy instruction the kids are receiving. If children are trying to guess based on pictures, parents can talk to teachers about increasing phonics instruction.

“Teachers aren’t there doing necessarily bad things or disadvantaging kids purposefully or willfully,” Rasmussen said. “You have many great reading teachers using some effective strategies and some ineffective strategies.”

What can parents do at home to help their children learn to read?

Parents want to help their kids learn how to read but don’t want to push them to the point where they hate reading. “Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

“Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

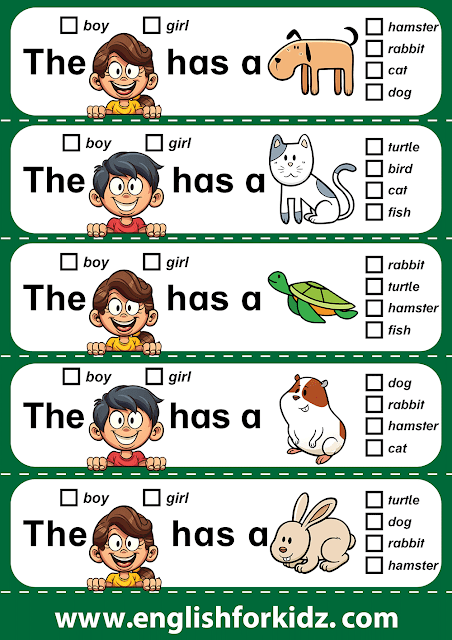

- Challenge kids to find everything in the house that starts with a specific sound.

- Stretch out one word in a sentence. Ask your child to “pass the salt” but say the individual sounds in the word “salt” instead of the word itself.

- Ask your child to figure out what every family member’s name would be if it started with a “b” sound.

- Sing that annoying “Banana fana fo fanna song.” Jiban said that kind of playful activity can actually help a kid think about the sounds that correspond with letters even if they’re not looking at a letter right in front of them.

- Read your child’s favorite book over and over again. For books that children know well, Jiban suggests that children use their finger to follow along as each word is read. Parents can do the same, or come up with another strategy to help kids follow which words they’re reading on a page.

Giving a child diverse experiences that seem to have nothing to do with reading can also help a child’s reading ability. By having a variety of experiences, Rasmussen said, children will be able to apply their own knowledge to better comprehend texts about various topics.

This story about teaching children to read was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

Is it necessary to teach a child to read before school - Kindergarten No. 101

municipal budgetary preschool educational institution "Kindergarten No. 101"

Teacher V. I. Lysenko

Dear parents! You are your child's first and most important teacher. His first school, your home, will have a huge impact on what he considers important in life, on the formation of his value system. No matter how long we live, we still constantly return to the experience of childhood - to life in the family.

Until recently, parents thought that children learned to read at school. Today, thanks to the research of educators and psychologists J. Piaget, B. Bloom, E. Erickson, we know that the child receives the stock of knowledge that is necessary in order to learn to read before school.

Piaget, B. Bloom, E. Erickson, we know that the child receives the stock of knowledge that is necessary in order to learn to read before school.

Parents often ask if their child should be taught to read and write before school? There are different opinions on this matter. Many parents have a strong idea that if a child comes to school knowing how to read well, then school will be boring and uninteresting for him. In such families, the natural curiosity of the child is deliberately inhibited, believing that he will be taught everything at school. There is a completely different position - the child must be given in advance all the knowledge that he should receive in the 1st grade. And, armed with the school “Primer” or “ABC”, parents begin to intensively teach the child to read. As a rule, this leads to a persistent unwillingness of the child to study. Under any pretext, a small student tries to evade reading. So what to do? If you have the time, are ready to play different sound and word games with your child, if you know how to enjoy all this and want to teach your baby to also enjoy activities, from the need to think, to overcome difficulties - start teaching him to read. This will make his future school life easier and save him from many problems. In addition, psychologists say that 5 years is the most sensitive age for learning to read. But, before starting to read, the child must learn to hear what sounds the word he pronounces consists of. How to teach to read? Many parents want to teach their children to read. Currently, there are many different recommendations and manuals. However, the result of teaching reading depends not only on the chosen system, but also on who teaches and under what conditions. The main thing is the child himself, his level of preparation for learning. And the level can be different:

This will make his future school life easier and save him from many problems. In addition, psychologists say that 5 years is the most sensitive age for learning to read. But, before starting to read, the child must learn to hear what sounds the word he pronounces consists of. How to teach to read? Many parents want to teach their children to read. Currently, there are many different recommendations and manuals. However, the result of teaching reading depends not only on the chosen system, but also on who teaches and under what conditions. The main thing is the child himself, his level of preparation for learning. And the level can be different:

- does not know letters,

- knows letters,

- reads by syllables.

Looking closely at the child, you can catch the right moment of his interest in reading. And it does not depend on age at all. It may even be earlier than 5 years. However, one should not wait long for the manifestation of interest in reading. It can be called up in many ways: beautiful books, pictures, bright letters, expressive reading, watching special TV shows, games, toys. Any action that is interesting for a child can be connected, connected with letters, with reading. It's important to do it on time. It has long been known that the later a child is taught to read, the more difficult it is for him. It has been noticed that it is easier to start introducing reading when the child learns to speak, when he simultaneously hears and sees what he himself or others say. Today, many parents undertake to teach reading on their own. It is believed that it is quite possible to teach a child what you yourself are good at. It's not always justified. It is also necessary to interest, and clearly explain, patiently repeat many times, and at the same time not impose.

It can be called up in many ways: beautiful books, pictures, bright letters, expressive reading, watching special TV shows, games, toys. Any action that is interesting for a child can be connected, connected with letters, with reading. It's important to do it on time. It has long been known that the later a child is taught to read, the more difficult it is for him. It has been noticed that it is easier to start introducing reading when the child learns to speak, when he simultaneously hears and sees what he himself or others say. Today, many parents undertake to teach reading on their own. It is believed that it is quite possible to teach a child what you yourself are good at. It's not always justified. It is also necessary to interest, and clearly explain, patiently repeat many times, and at the same time not impose.

For more than 4 years, our preschool has been providing additional services to teach children to read in the Chitayka circle for children of 5 years of age. The methodology of A. N. Zaitsev, which we use, showed that reading in “warehouses” (the term of the methodology) speeds up the learning process. After 2-3 months, children master reading by syllable.

The methodology of A. N. Zaitsev, which we use, showed that reading in “warehouses” (the term of the methodology) speeds up the learning process. After 2-3 months, children master reading by syllable.

Acquaintance with each "mistress" of sound helps children expand their vocabulary, develop phonemic hearing. The “mistresses” of sounds are included in word games, tongue-twisters, sayings, which makes it possible to comprehend reading. At the request of parents, consultations and open classes are held. They can always see the results of reading in their children and rejoice at their success.

Learning to read | Kindergarten No. 74 of a general developmental type

Home » Our consultations » From the experience of our teachers » Learning to read

For you, parents!

(from the work experience of the educator MADOU No. 74 Rubtsova Marina Vasilievna )

Parents of preschool children attending kindergarten often rely on the fact that their children will be prepared for school by the efforts of educators. Indeed, specially organized classes help children prepare for school, but without the help of parents, such preparation will not be of high quality.

Indeed, specially organized classes help children prepare for school, but without the help of parents, such preparation will not be of high quality.

Experience shows that no best children's institution - neither kindergarten nor elementary school - can completely replace the family, family education. In a preschool institution, children are taught many useful skills, they are taught to draw, count, write and read. But if the family does not take an interest in the child’s activities, do not attach due importance to them, do not encourage diligence and diligence, the child also begins to treat them with disdain, does not strive to work better, correct his mistakes, and overcome difficulties in work. Some children are deeply offended by such inattention of their parents, they cease to be sincere and frank. On the contrary, the interest of parents in the affairs of the child attaches particular importance to all the achievements of the child. Help in overcoming the difficulties that arise in the performance of any kind of activity is always accepted with gratitude and contributes to the closeness of parents and children. At home, the ability to read can come as naturally to a child as the ability to walk or talk. Dear parents, grandparents! If you want to teach your child to read before he goes to school, pay attention and understanding to all our advice. To avoid the sad consequences of illiterate learning.

At home, the ability to read can come as naturally to a child as the ability to walk or talk. Dear parents, grandparents! If you want to teach your child to read before he goes to school, pay attention and understanding to all our advice. To avoid the sad consequences of illiterate learning.

Learning to read

It is believed that learning to read early gives a child great intellectual potential. A pre-reader or a first-grader who is already reading develops faster, learns easier and better, and remembers more.

Where to start?

- The main rule of learning to read: "Do not chase the result!". First, show your child the alphabet. If he is interested, consider it, name the letters, syllables. Learning to read is best started on their own initiative. Your task is to support, not to ruin the initiative with excessive zeal.

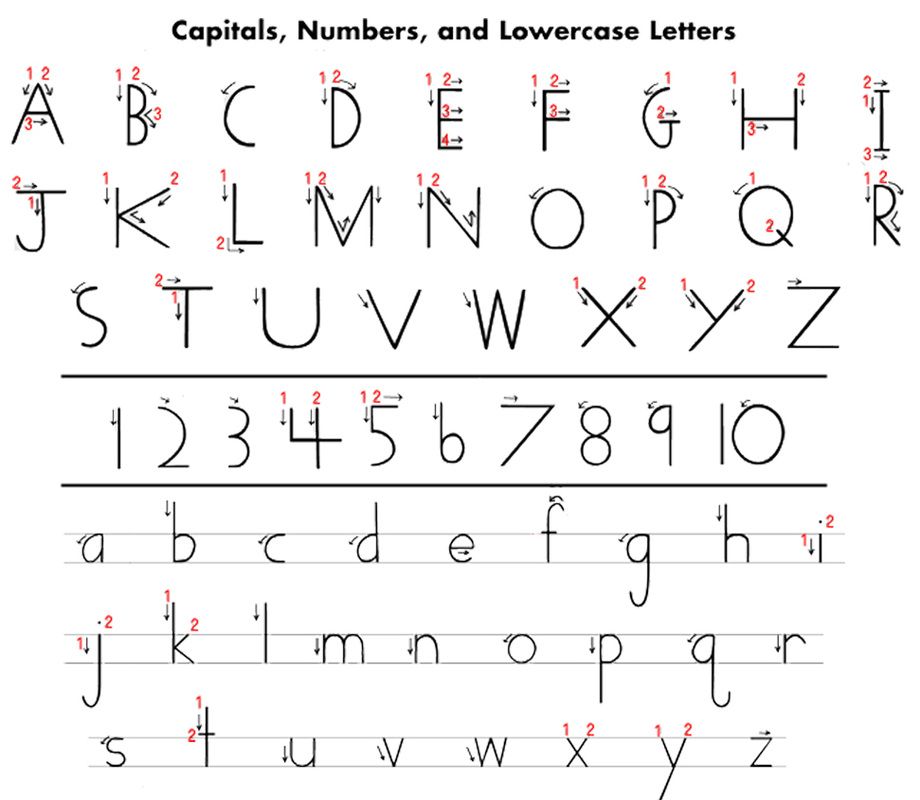

- Learning to read can begin with the study of letters or syllables. Colorful tables, posters, cubes are well suited for these purposes. The material may change from time to time. And it is not at all necessary to memorize the alphabetic name of the letters with the kids.

The material may change from time to time. And it is not at all necessary to memorize the alphabetic name of the letters with the kids.

-Pay special attention to the game form of the lessons, as well as their duration (15-20 minutes). Do not forget how joyful and interesting they will be, his further education largely depends. The main thing is not to forget that all this is just a game, and not preparation for the exam.

-If a child is ill or not in the mood to study, it is better to postpone the “lesson”, do not study by force.

- Classes should be varied, change tasks more often, because small children get tired quickly and their attention is scattered. So you will have to constantly maintain the interest of the child in what you propose to do.

- Read with the child. Mom is the best role model.

- In parallel with reading, you can learn to write. The child will be quite capable of performing graphic tasks: circle simple figures point by point with your hand. You can "type" on the old keyboard. Maze toys prepare a hand well for writing, in which small details need to be raised, for example, from bottom to top, or swiped from left to right.

You can "type" on the old keyboard. Maze toys prepare a hand well for writing, in which small details need to be raised, for example, from bottom to top, or swiped from left to right.

Important about letters

You can often see such a picture on the street. Mom asks the child, pointing to any letter of the sign on the house: "What is this letter?" The child happily answers: "PE!", Or "EM!", Or "ES!" One feels like saying:

“Dear adults! If this is how you call letters to children,

, then how will your little student read the syllable "MA"? Imagine, he will most likely get "EMA"! And he will be right: EM + A = EMA. And the word "MA-MA" in this case will be read as "EMA-EMA"!

Most teachers and speech therapists agree that when teaching preschool children, the alphabetic army should be called in a simplified way: not “pe”, but “p”, not “me”, but “m”.

Learning to read at home

How to teach to read and not injure the psyche, not to force, but on the contrary, arouse interest and desire? If you actively played with the child, while attracting a book, then this will greatly facilitate the task.

The first unsuccessful experiences can completely discourage you from starting to learn to read. The child understands that learning to read is not so easy and hardly repeats attempts. Learn more letters back and forth. But to combine them into words and read, and then understand what you read - it's pretty hard. But gradually the child overcomes this difficulty.

Learn to read in the game. But, most importantly, what we should remember is not to torment the child and ourselves. Don't make it an unpleasant duty, don't compare one child to another.

Here we need patience, love, consistency, fantasy. You can beat the learning process, turn it into a holiday, into an exciting game. Keep it short but effective.

So, let's move on to the study of letters and sounds.

1. Learning is best to start with vowels.

Some parents have already introduced their children to different letters, but where do you start? You need to start with vowels, which you need to determine whether the child remembers them well.

To teach children to read, you can use cut out letters, paint, plasticine, whatever you want.

Now I will show you some exercises that will help you to consolidate the learned vowels.

- I will call you a letter, and you take it out of the magic box and we are building a house with you:

E e

A A

O o O O O O O O O O O O O O O O O am

,0003and

U has

EE

This is needed for that. so that the child learns to read and write lines. ( Can be read)

It will take some time to memorize one letter, three, four, five or even six days. If the child remembers longer, it's okay. It is important that the child not only read a new letter, but also knows how to find it. You can ask the child to find the letter O , then the letter A , and so quietly the child makes a train.

A U O E I S E Y Y Y Y YO

Later, when the train is completed, the child can read it. If a child has a hard time remembering vowels, you can remember them associatively. But A , as always, does not cause difficulties, U are ears, And - we smile, O - this is a circle, what we see, then we say, the letter Yu - can be remembered as a skirt, E - the car is driving, E - hedgehog, If the child has forgotten the letter, then ask him: "Prickly with eyes."

The most difficult letter of the vowels is the letter E . This letter is difficult because some children pronounce it like E , this is wrong. It is necessary to monitor the correct pronunciation of the sound and correct the child.

A U O E I S E Y Y Y E

The letter E came out to the yard for a walk, which letter came out to her, choose.

EO , change places you get OE .

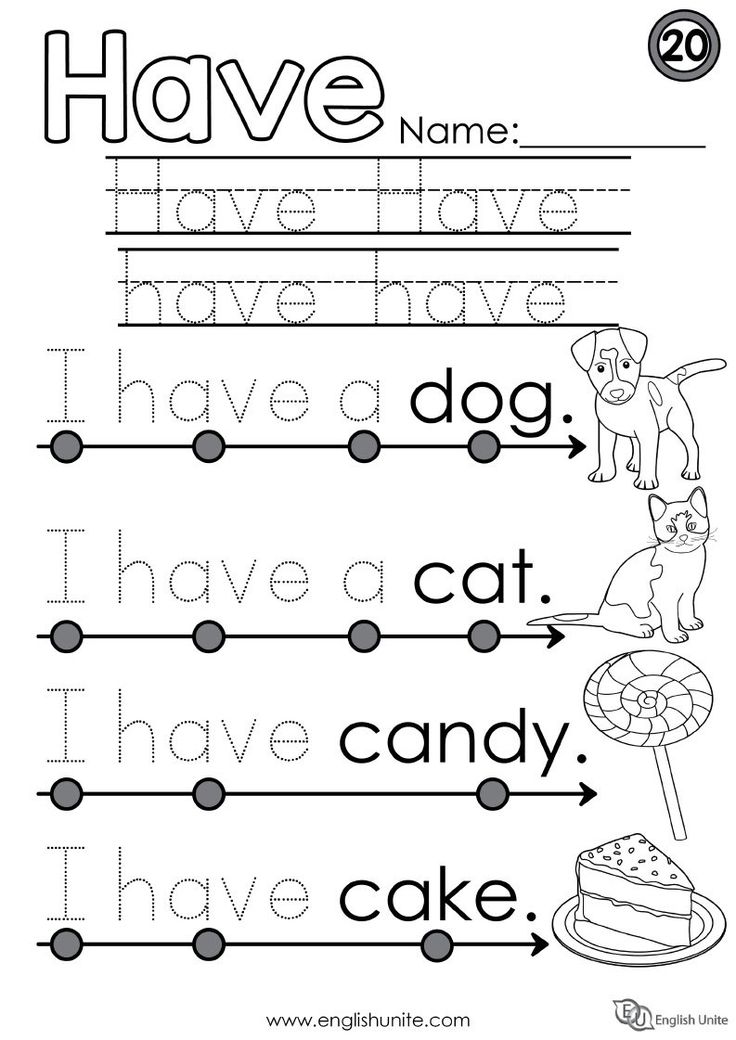

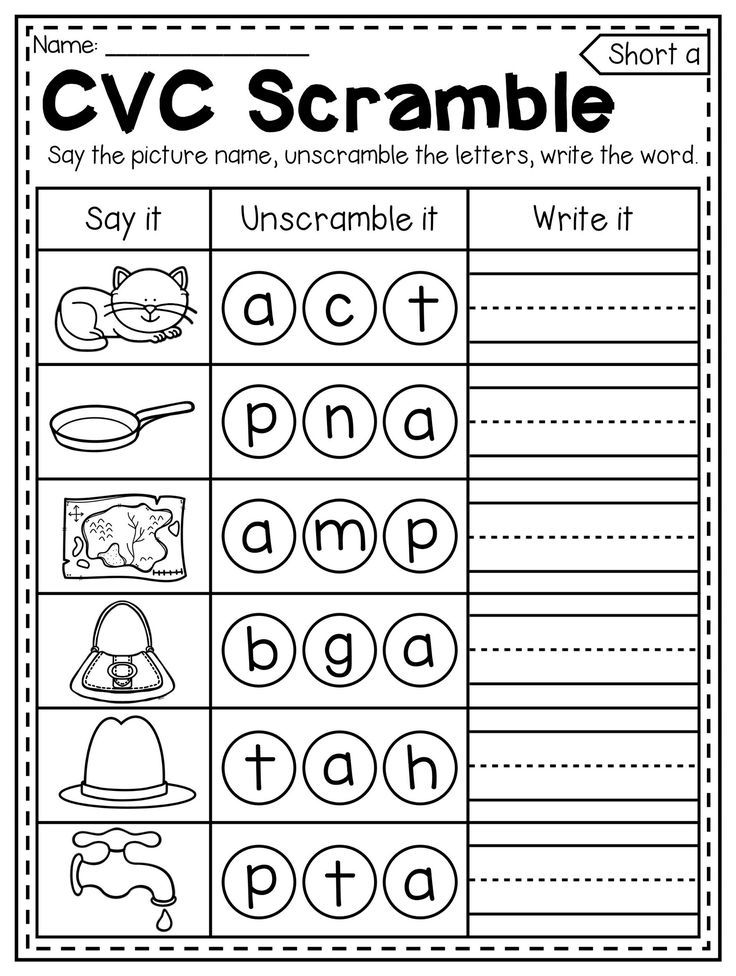

So, we have already learned the vowels, let's move on to the consonants.

Consonants

To study consonants, choose the first voiced letter, M, N, L, R .

Consonants are best studied immediately with a familiar vowel. It is easier for a child to remember a new letter. In addition, we thus imperceptibly approach the syllables.

To do this, the child needs to build a house out of vowels:

A E

O UU

and I

S

Next, we introduce a child with a new consonant letter. We tell the child to raise the letter on the elevator while reading the syllable.

If a child cannot remember a letter or pronounces it incorrectly, an exercise called "Pens, Pens" will come in handy.

The child sits in front of you so that he is not distracted, take his hands. This exercise is difficult and requires a lot of attention.

This exercise is difficult and requires a lot of attention.

You hold the child by the hands, and he, looking into your mouth, repeats after you.

The peculiarity of this exercise is that the child does not see the letter, he perceives it by ear.

First, show the child the letter with your hand, and let him name them, later you remove your hand and the child should show and name the letters. For example: with the letter , will have NU , etc. It is necessary to ensure that the child reads not only when you show him with your finger, but so that he himself can take and read.

Syllables

Children usually stumble at this stage. It is difficult for them to read syllables together. It is important that the child not only read the syllables first consonants and then vowels, but also to be able to distinguish when, on the contrary, there are first a vowel and then a consonant.

We offer you a manual that makes it easy for children to learn syllabic reading.

Didactic manual for teaching reading "Magic Windows"

At the stage of learning to read syllables, it is useful to use such a device. Making this educational game is not an easy task. But all preschoolers like to play with "windows", and you will not regret taking the time to make this manual.

You will need:

2 sheets of white or colored card stock;

sketchbook;

ruler;

simple pencil;

colored pencils or markers;

scissors, glue.

Make a markup on one sheet of cardboard: lay the sheet horizontally, divide it into 2 equal parts with a vertical line, mark windows at the same level in each half, observing the same indentation from the edges and from the middle line. Cut out the windows with scissors. On the reverse side, glue a cap from the second sheet of cardboard. Apply glue only along the middle line, along the right and left edges.

Open the album in the middle, unfasten the staples and pull out the double sheet of paper. Cut it in half lengthwise so that you get two identical strips. Mark each strip along its entire length: draw rectangles with a width corresponding to the height of the window in the part made of cardboard earlier. On one strip, write the vowels A, O, U, Y, I, E, E, I, Yu, E (one letter in each rectangle). On the second strip, write the consonants M, P, N, K, C, C, T, B, D, G, 3, F (also one letter in each rectangle).

Cut it in half lengthwise so that you get two identical strips. Mark each strip along its entire length: draw rectangles with a width corresponding to the height of the window in the part made of cardboard earlier. On one strip, write the vowels A, O, U, Y, I, E, E, I, Yu, E (one letter in each rectangle). On the second strip, write the consonants M, P, N, K, C, C, T, B, D, G, 3, F (also one letter in each rectangle).

Insert the strips into the cardboard frame: the vowel strip on the right, the consonant strip on the left.

Now set any consonant letter in the left window, and move the right bar so that vowels appear in turn in the right window. Let the child read the resulting syllables. For example: MA - MO - MU - WE - MI - ME - MY - MY - MU - ME. Move the bar on the left to make a new consonant appear, move the right bar again, inviting the child to read new syllables.

Next time, leave the vowel you chose unchanged, and change the consonant by moving the left bar in the boxes.