Early math skills

Help Your Child Develop Early Math Skills

Before they start school, most children develop an understanding of addition and subtraction through everyday interactions. Learn what informal activities give children a head start on early math skills when they start school.

Children are using early math skills throughout their daily routines and activities. This is good news as these skills are important for being ready for school. But early math doesn’t mean taking out the calculator during playtime. Even before they start school, most children develop an understanding of addition and subtraction through everyday interactions. For example, Thomas has two cars; Joseph wants one. After Thomas shares one, he sees that he has one car left (Bowman, Donovan, & Burns, 2001, p. 201). Other math skills are introduced through daily routines you share with your child—counting steps as you go up or down, for example. Informal activities like this one give children a jumpstart on the formal math instruction that starts in school.

What math knowledge will your child need later on in elementary school? Early mathematical concepts and skills that first-grade mathematics curriculum builds on include: (Bowman et al., 2001, p. 76).

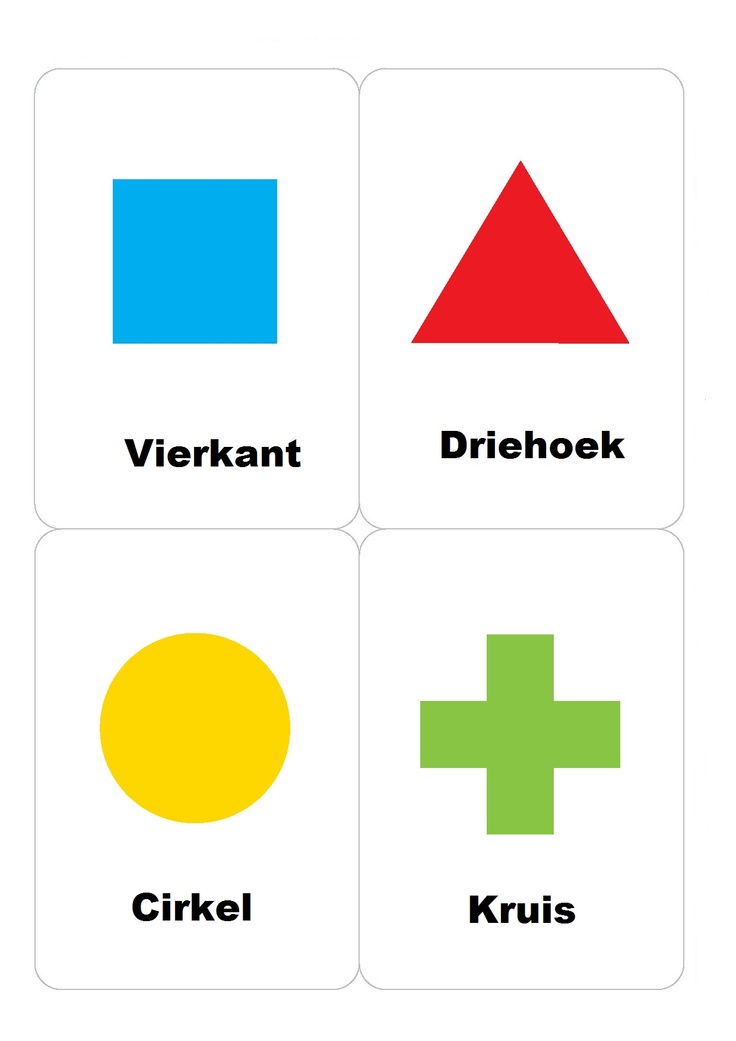

- Understanding size, shape, and patterns

- Ability to count verbally (first forward, then backward)

- Recognizing numerals

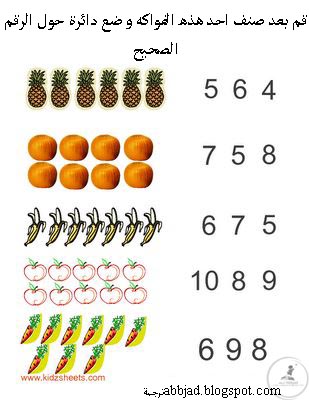

- Identifying more and less of a quantity

- Understanding one-to-one correspondence (i.e., matching sets, or knowing which group has four and which has five)

Key Math Skills for School

More advanced mathematical skills are based on an early math “foundation”—just like a house is built on a strong foundation. In the toddler years, you can help your child begin to develop early math skills by introducing ideas like: (From Diezmann & Yelland, 2000, and Fromboluti & Rinck, 1999.)

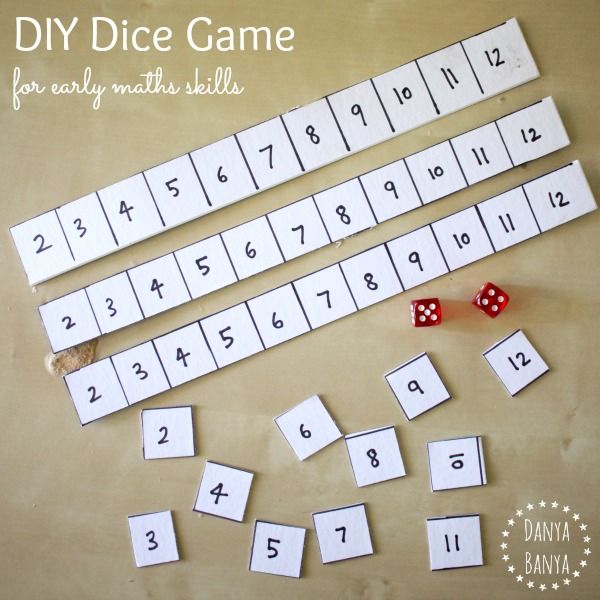

Number Sense

This is the ability to count accurately—first forward. Then, later in school, children will learn to count backwards. A more complex skill related to number sense is the ability to see relationships between numbers—like adding and subtracting. Ben (age 2) saw the cupcakes on the plate. He counted with his dad: “One, two, three, four, five, six…”

A more complex skill related to number sense is the ability to see relationships between numbers—like adding and subtracting. Ben (age 2) saw the cupcakes on the plate. He counted with his dad: “One, two, three, four, five, six…”

Representation

Making mathematical ideas “real” by using words, pictures, symbols, and objects (like blocks). Casey (aged 3) was setting out a pretend picnic. He carefully laid out four plastic plates and four plastic cups: “So our whole family can come to the picnic!” There were four members in his family; he was able to apply this information to the number of plates and cups he chose.

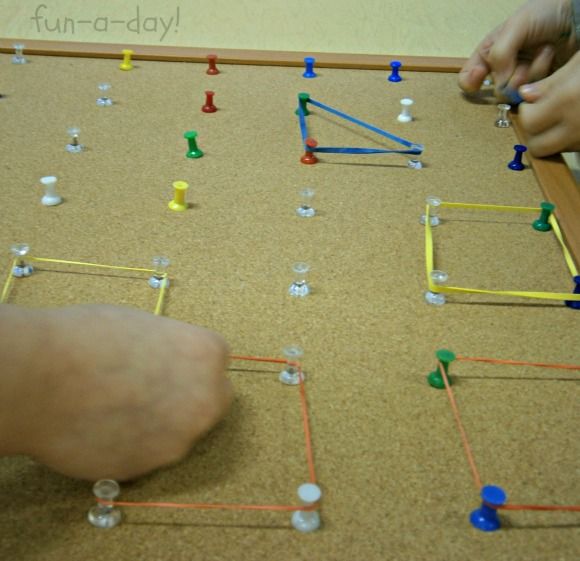

Spatial sense

Later in school, children will call this “geometry.” But for toddlers it is introducing the ideas of shape, size, space, position, direction and movement. Aziz (28 months) was giggling at the bottom of the slide. “What’s so funny?” his Auntie wondered. “I comed up,” said Aziz, “Then I comed down!”

Measurement

Technically, this is finding the length, height, and weight of an object using units like inches, feet or pounds. Measurement of time (in minutes, for example) also falls under this skill area. Gabriella (36 months) asked her Abuela again and again: “Make cookies? Me do it!” Her Abuela showed her how to fill the measuring cup with sugar. “We need two cups, Gabi. Fill it up once and put it in the bowl, then fill it up again.”

Measurement of time (in minutes, for example) also falls under this skill area. Gabriella (36 months) asked her Abuela again and again: “Make cookies? Me do it!” Her Abuela showed her how to fill the measuring cup with sugar. “We need two cups, Gabi. Fill it up once and put it in the bowl, then fill it up again.”

Estimation

This is the ability to make a good guess about the amount or size of something. This is very difficult for young children to do. You can help them by showing them the meaning of words like more, less, bigger, smaller, more than, less than. Nolan (30 months) looked at the two bagels: one was a regular bagel, one was a mini-bagel. His dad asked: “Which one would you like?” Nolan pointed to the regular bagel. His dad said, “You must be hungry! That bagel is bigger. That bagel is smaller. Okay, I’ll give you the bigger one. Breakfast is coming up!”

Patterns

Patterns are things—numbers, shapes, images—that repeat in a logical way. Patterns help children learn to make predictions, to understand what comes next, to make logical connections, and to use reasoning skills. Ava (27 months) pointed to the moon: “Moon. Sun go night-night.” Her grandfather picked her up, “Yes, little Ava. In the morning, the sun comes out and the moon goes away. At night, the sun goes to sleep and the moon comes out to play. But it’s time for Ava to go to sleep now, just like the sun.”

Patterns help children learn to make predictions, to understand what comes next, to make logical connections, and to use reasoning skills. Ava (27 months) pointed to the moon: “Moon. Sun go night-night.” Her grandfather picked her up, “Yes, little Ava. In the morning, the sun comes out and the moon goes away. At night, the sun goes to sleep and the moon comes out to play. But it’s time for Ava to go to sleep now, just like the sun.”

Problem-solving

The ability to think through a problem, to recognize there is more than one path to the answer. It means using past knowledge and logical thinking skills to find an answer. Carl (15 months old) looked at the shape-sorter—a plastic drum with 3 holes in the top. The holes were in the shape of a triangle, a circle and a square. Carl looked at the chunky shapes on the floor. He picked up a triangle. He put it in his month, then banged it on the floor. He touched the edges with his fingers. Then he tried to stuff it in each of the holes of the new toy. Surprise! It fell inside the triangle hole! Carl reached for another block, a circular one this time…

Surprise! It fell inside the triangle hole! Carl reached for another block, a circular one this time…

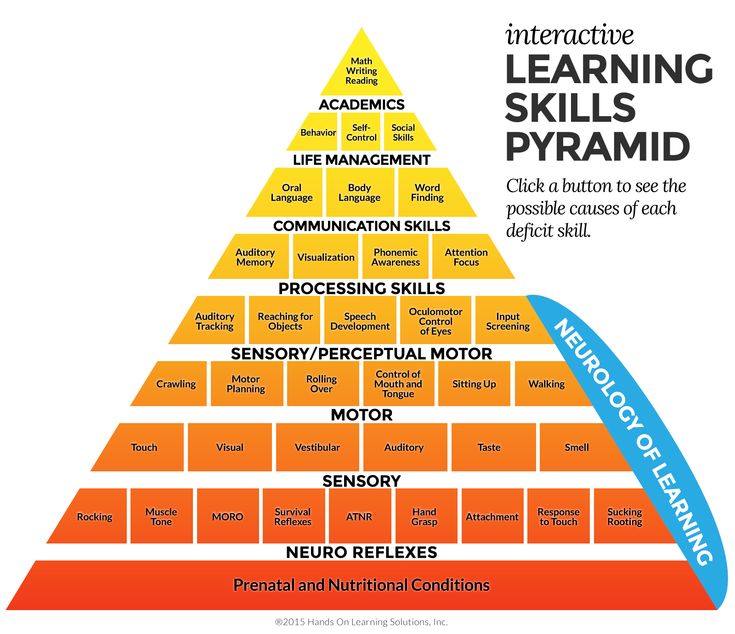

Math: One Part of the Whole

Math skills are just one part of a larger web of skills that children are developing in the early years—including language skills, physical skills, and social skills. Each of these skill areas is dependent on and influences the others.

Trina (18 months old) was stacking blocks. She had put two square blocks on top of one another, then a triangle block on top of that. She discovered that no more blocks would balance on top of the triangle-shaped block. She looked up at her dad and showed him the block she couldn’t get to stay on top, essentially telling him with her gesture, “Dad, I need help figuring this out.” Her father showed her that if she took the triangle block off and used a square one instead, she could stack more on top. She then added two more blocks to her tower before proudly showing her creation to her dad: “Dada, Ook! Ook!”

You can see in this ordinary interaction how all areas of Trina’s development are working together. Her physical ability allows her to manipulate the blocks and use her thinking skills to execute her plan to make a tower. She uses her language and social skills as she asks her father for help. Her effective communication allows Dad to respond and provide the helps she needs (further enhancing her social skills as she sees herself as important and a good communicator). This then further builds her thinking skills as she learns how to solve the problem of making the tower taller.

Her physical ability allows her to manipulate the blocks and use her thinking skills to execute her plan to make a tower. She uses her language and social skills as she asks her father for help. Her effective communication allows Dad to respond and provide the helps she needs (further enhancing her social skills as she sees herself as important and a good communicator). This then further builds her thinking skills as she learns how to solve the problem of making the tower taller.

What You Can Do

The tips below highlight ways that you can help your child learn early math skills by building on their natural curiosity and having fun together. (Note: Most of these tips are designed for older children—ages 2–3. Younger children can be exposed to stories and songs using repetition, rhymes and numbers.)

Shape up.

Play with shape-sorters. Talk with your child about each shape—count the sides, describe the colors. Make your own shapes by cutting large shapes out of colored construction paper. Ask your child to “hop on the circle” or “jump on the red shape.”

Ask your child to “hop on the circle” or “jump on the red shape.”

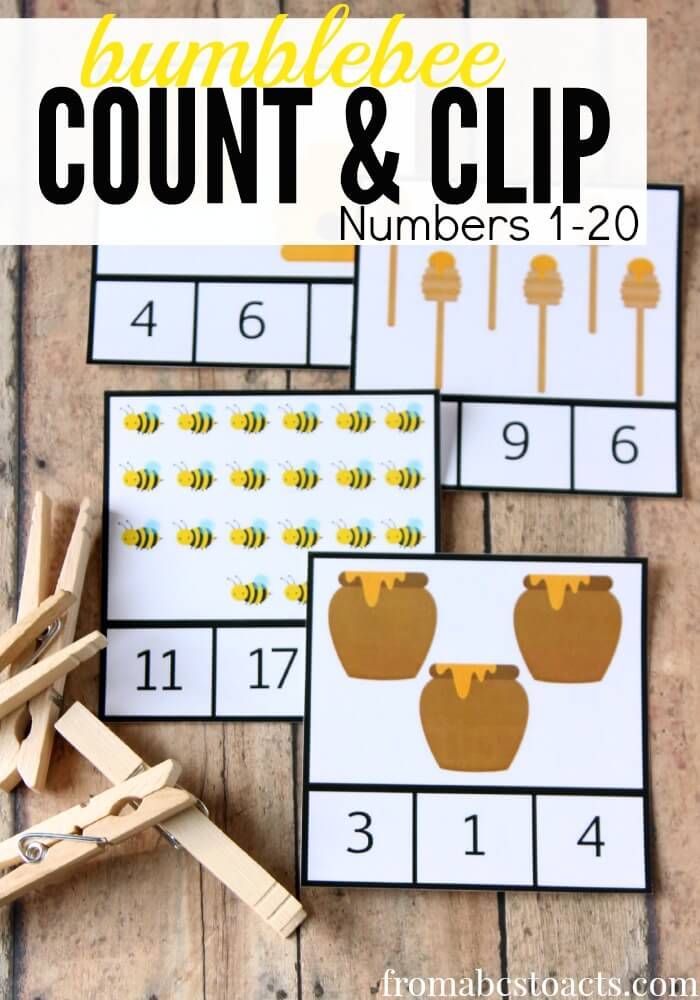

Count and sort.

Gather together a basket of small toys, shells, pebbles or buttons. Count them with your child. Sort them based on size, color, or what they do (i.e., all the cars in one pile, all the animals in another).

Place the call.

With your 3-year-old, begin teaching her the address and phone number of your home. Talk with your child about how each house has a number, and how their house or apartment is one of a series, each with its own number.

What size is it?

Notice the sizes of objects in the world around you: That pink pocketbook is the biggest. The blue pocketbook is the smallest. Ask your child to think about his own size relative to other objects (“Do you fit under the table? Under the chair?”).

You’re cookin’ now!

Even young children can help fill, stir, and pour. Through these activities, children learn, quite naturally, to count, measure, add, and estimate.

Walk it off.

Taking a walk gives children many opportunities to compare (which stone is bigger?), assess (how many acorns did we find?), note similarities and differences (does the duck have fur like the bunny does?) and categorize (see if you can find some red leaves). You can also talk about size (by taking big and little steps), estimate distance (is the park close to our house or far away?), and practice counting (let’s count how many steps until we get to the corner).

Picture time.

Use an hourglass, stopwatch, or timer to time short (1–3 minute) activities. This helps children develop a sense of time and to understand that some things take longer than others.

Shape up.

Point out the different shapes and colors you see during the day. On a walk, you may see a triangle-shaped sign that’s yellow. Inside a store you may see a rectangle-shaped sign that’s red.

Read and sing your numbers.

Sing songs that rhyme, repeat, or have numbers in them. Songs reinforce patterns (which is a math skill as well). They also are fun ways to practice language and foster social skills like cooperation.

Songs reinforce patterns (which is a math skill as well). They also are fun ways to practice language and foster social skills like cooperation.

Start today.

Use a calendar to talk about the date, the day of the week, and the weather. Calendars reinforce counting, sequences, and patterns. Build logical thinking skills by talking about cold weather and asking your child: What do we wear when it’s cold? This encourages your child to make the link between cold weather and warm clothing.

Pass it around.

Ask for your child’s help in distributing items like snacks or in laying napkins out on the dinner table. Help him give one cracker to each child. This helps children understand one-to-one correspondence. When you are distributing items, emphasize the number concept: “One for you, one for me, one for Daddy.” Or, “We are putting on our shoes: One, two.”

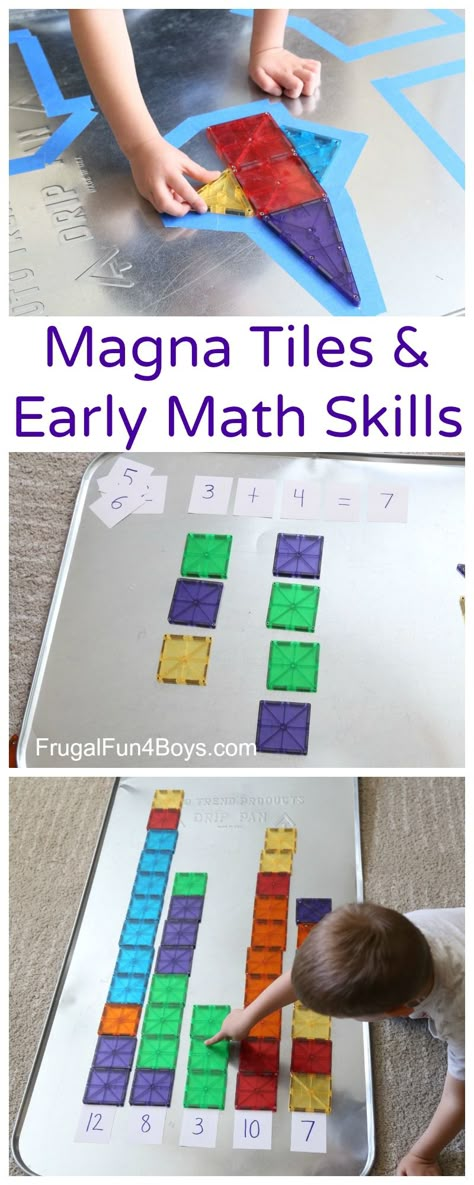

Big on blocks.

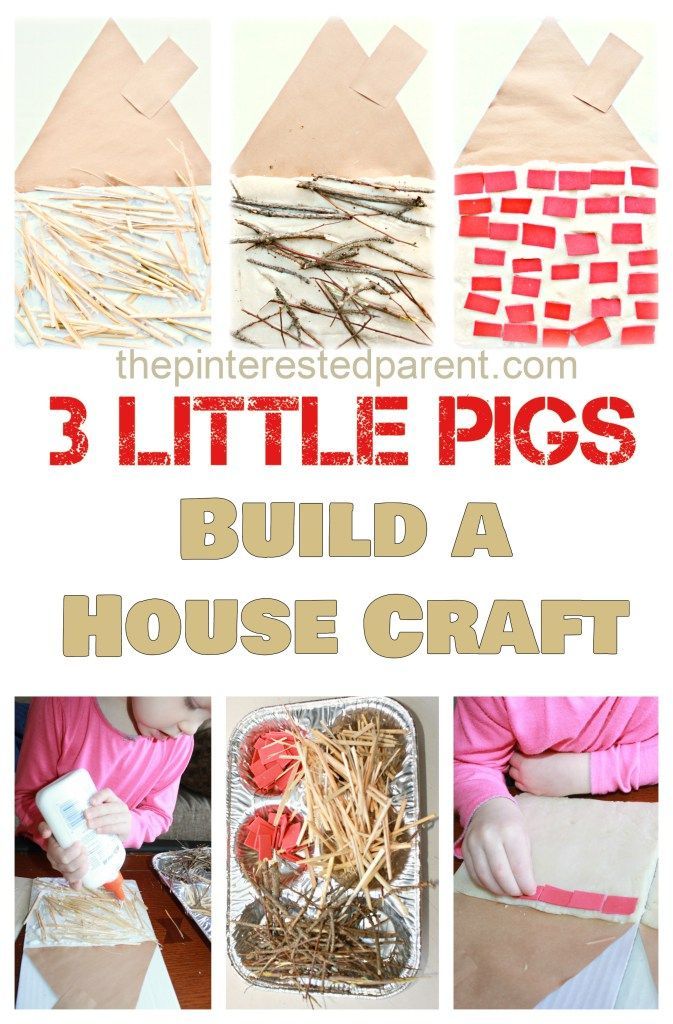

Give your child the chance to play with wooden blocks, plastic interlocking blocks, empty boxes, milk cartons, etc. Stacking and manipulating these toys help children learn about shapes and the relationships between shapes (e.g., two triangles make a square). Nesting boxes and cups for younger children help them understand the relationship between different sized objects.

Stacking and manipulating these toys help children learn about shapes and the relationships between shapes (e.g., two triangles make a square). Nesting boxes and cups for younger children help them understand the relationship between different sized objects.

Tunnel time.

Open a large cardboard box at each end to turn it into a tunnel. This helps children understand where their body is in space and in relation to other objects.

The long and the short of it.

Cut a few (3–5) pieces of ribbon, yarn or paper in different lengths. Talk about ideas like long and short. With your child, put in order of longest to shortest.

Learn through touch.

Cut shapes—circle, square, triangle—out of sturdy cardboard. Let your child touch the shape with her eyes open and then closed.

Pattern play.

Have fun with patterns by letting children arrange dry macaroni, chunky beads, different types of dry cereal, or pieces of paper in different patterns or designs. Supervise your child carefully during this activity to prevent choking, and put away all items when you are done.

Supervise your child carefully during this activity to prevent choking, and put away all items when you are done.

Laundry learning.

Make household jobs fun. As you sort the laundry, ask your child to make a pile of shirts and a pile of socks. Ask him which pile is the bigger (estimation). Together, count how many shirts. See if he can make pairs of socks: Can you take two socks out and put them in their own pile? (Don’t worry if they don’t match! This activity is more about counting than matching.)

Playground math.

As your child plays, make comparisons based on height (high/low), position (over/under), or size (big/little).

Dress for math success.

Ask your child to pick out a shirt for the day. Ask: What color is your shirt? Yes, yellow. Can you find something in your room that is also yellow? As your child nears three and beyond, notice patterns in his clothing—like stripes, colors, shapes, or pictures: I see a pattern on your shirt. There are stripes that go red, blue, red, blue. Or, Your shirt is covered with ponies—a big pony next to a little pony, all over your shirt!

Or, Your shirt is covered with ponies—a big pony next to a little pony, all over your shirt!

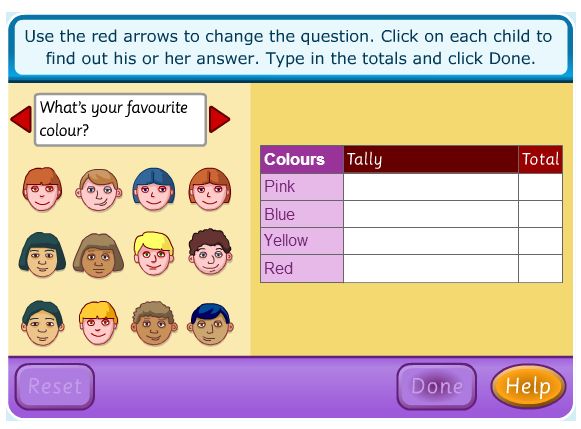

Graphing games.

As your child nears three and beyond, make a chart where your child can put a sticker each time it rains or each time it is sunny. At the end of a week, you can estimate together which column has more or less stickers, and count how many to be sure.

References

Bowman, B.T., Donovan, M.S., & Burns, M.S., (Eds.). (2001). Eager to learn: Educating our preschoolers. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

Diezmann, C., & Yelland, N. J. (2000). Developing mathematical literacy in the early childhood years. In Yelland, N.J. (Ed.), Promoting meaningful learning: Innovations in educating early childhood professionals. (pp.47–58). Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

Fromboluti, C. S., & Rinck, N. (1999 June). Early childhood: Where learning begins. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement, National Institute on Early Childhood Development and Education. Retrieved on May 11, 2018 from https://www2.ed.gov/pubs/EarlyMath/title.html

Retrieved on May 11, 2018 from https://www2.ed.gov/pubs/EarlyMath/title.html

5 math skills your child needs to get ready for kindergarten

Leer en español.

Parents play a critical role in their children’s early math education. They not only can provide math-related toys and games, but serve as role models demonstrating how math is used in everyday activities.

Children who see their parents doing everyday math engage more often in math activities. This, in turn, builds early math skills, which serve as the foundation for later learning.

As researchers who study children’s math development, we believe there are five math skills that children should have at the start of kindergarten. Opportunities for learning these skills are everywhere – and there are simple, enjoyable activities that parents can lead to foster these skills.

This will help children acquire the age-appropriate vocabulary and skills needed for learning math, while staying engaged and having fun.

1. Counting and cardinality

According to the college and career-ready standards in our state, Maryland, children are expected to demonstrate simple counting skills before starting kindergarten. These skills include counting to 20; ordering number cards; identifying without counting how many items are in a small set; and understanding that quantity does not change regardless of how a set of items is arranged.

Children also will need to learn cardinality. That means they should understand that the last item counted represents the number of items in the set.

Counting and cardinality can be easily integrated into daily life. Children can count their toys as they clean up or count how many steps it takes to walk from the kitchen to their bedroom. Parents can point out numbers on a clock or phone.

In the grocery store, parents can ask children to find numbers while shopping. In the car, parents can have children read the numbers on license plates or count passing cars. Parents should ask, “How many?” after a child has counted, to reinforce the idea of cardinality.

Parents should ask, “How many?” after a child has counted, to reinforce the idea of cardinality.

Board games like Trouble, Hi Ho Cherry-O and Chutes and Ladders are helpful and fun ways to hone counting and cardinality skills. Have children identify the number on the die or spinner when they take their turn and count aloud when they move their piece. Active games that involve counting aloud – like jump rope, hopscotch or clapping – also foster these skills.

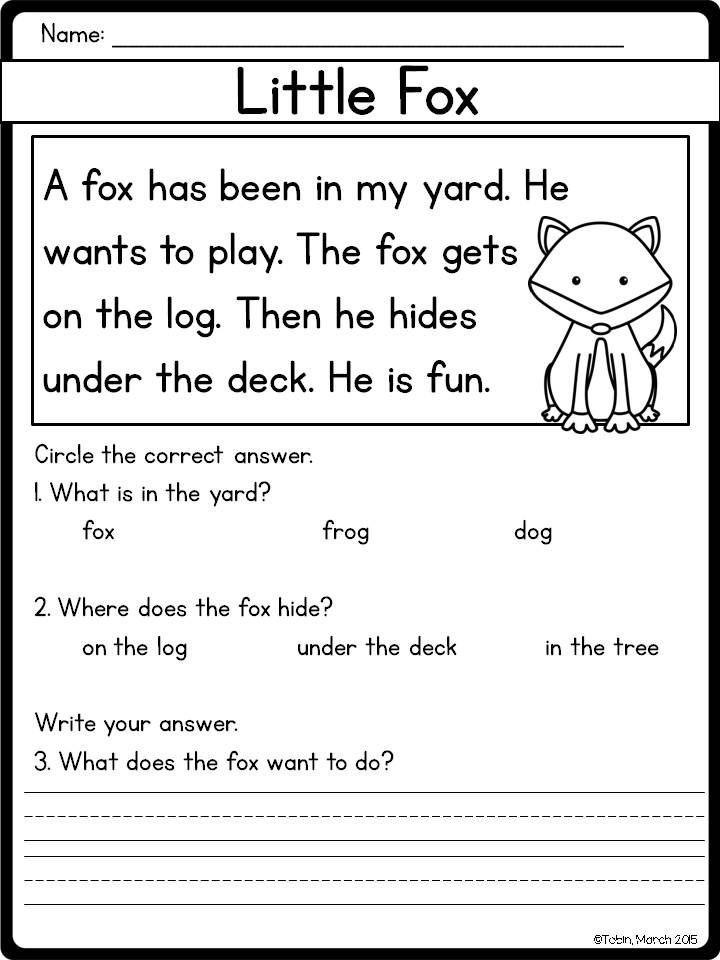

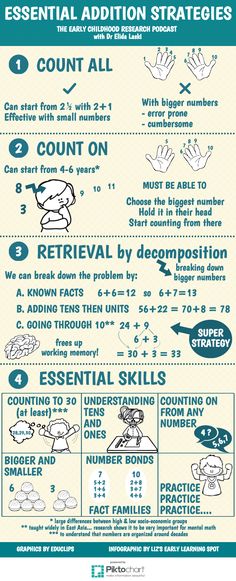

2. Operations and algebraic thinking

Kindergartners are expected to solve simple addition and subtraction problems using objects.

Parents can have children do simple math problems during everyday tasks. For example, they can ask children to take out the correct number of plates or utensils when setting the table for dinner. Remember, the math language children hear matters. Parents can ask questions like, “How many more plates do we need?”“

During play, parents can use toys and say things like, "I’m going to give you one of my cars. Let’s count how many cars you have now.” Songs and rhymes that include counting up or counting down, such as Five in the Bed or Teasing Mr. Crocodile, can also be useful for teaching early addition and subtraction.

Let’s count how many cars you have now.” Songs and rhymes that include counting up or counting down, such as Five in the Bed or Teasing Mr. Crocodile, can also be useful for teaching early addition and subtraction.

3. Numbers and operations in base 10

Children need to begin to understand that the number “ten” is made up of 10 “ones.”

Playing with coins can help children learn about numbers. A3pfamily/shutterstockCounting fingers and toes is a great way to emphasize the numbers one through 10. Money, coins in particular, is another great way to emphasize base 10. Parents can play store with their children using pennies and have them “purchase” toys for differing amounts of pennies. During play, they can talk about how many toys they can buy with 10 cents.

4. Measurement and data

Kindergartners are expected to sort objects by their features – like shape, color and size – or identify the feature by which objects have been sorted. They also are expected to order objects by some measurable feature, such as from bigger to smaller.

They also are expected to order objects by some measurable feature, such as from bigger to smaller.

In the kitchen, children can begin experimenting with measurement using spoons or cups. Children can sort utensils, laundry or toys as they put them away. Card and dice games, such as War, are helpful for talking about number magnitude. Additionally, several inexpensive sorting games, such as Ready Sets Go or Ready Set Woof, are commercially available.

Additionally, kindergartners should be able to compare objects and use language like more than or less than, longer or shorter, and heavier or lighter. Parents can help by using these words to emphasize comparisons. When children are helping with tasks, parents can ask questions like, “Can you hand me the biggest bowl?” or “Can you put the smaller forks on the table?”

5. Geometry

Early geometry skills include naming and identifying 2D shapes like circles, squares and triangles. Children also need to realize that shapes of different sizes, orientations and dimensions are similar. Children should be able to recognize that a circle is like a sphere and use informal names like “box” and “ball” to identify three-dimensional objects.

Children should be able to recognize that a circle is like a sphere and use informal names like “box” and “ball” to identify three-dimensional objects.

Parents can draw children’s attention to shapes found in the environment. On a walk, parents can point out that wheels are circles and then have children find other circles in the environment. Commercially available games like Perfection or Tangrams can help children learn to identify simple and more complex shapes. Puzzles, blocks and Legos are another great way to help build early spatial skills.

A propensity for mathematics: how to identify and develop mathematical abilities in a child

Education

- Photo

- Getty Images

“I am a humanist,” my son makes a dramatic gesture with his hands, having received another C in algebra. - All in you.

I only sigh in response, remembering how, at the age of three, a child's favorite toy was numbers in all its variants: on cubes, plastic, foam rubber. After all, he could become a genius from mathematics - where did everything go?

After all, he could become a genius from mathematics - where did everything go?

Is it true that a humanist cannot become a "technician"? Does love for numbers depend on genetics? Can math skills be developed? Let's figure it out with the experts.

When is the best time to start doing math with your child? The main thing is to see the child’s interest in mathematics in time and start developing his abilities, because regular classes are the key to success in any field. Often, diligent children who are able to learn succeed more often than children with more developed intellectual abilities.

How do you show your ability in mathematics?

First of all, as an interest in knowledge, a desire to get an answer to a question, to get to the bottom of a phenomenon, a problem. Another important indicator is a high level of memory development. Children can quickly and permanently remember what they heard, saw, and use this knowledge if necessary.

No less important is a developed imagination, although it is generally considered to be the lot of the humanities. A child with a developed imagination often tries to improve the games that surround him, builds and invents various fantastic worlds in his head. This suggests that he has no problems with spatial representations and data visualization, which greatly facilitates the process of solving mathematical problems in the future.

A child with a developed imagination often tries to improve the games that surround him, builds and invents various fantastic worlds in his head. This suggests that he has no problems with spatial representations and data visualization, which greatly facilitates the process of solving mathematical problems in the future.

Important!

Activities with preschool children should be in the form of a game. For example, outdoor activities: find three leaves and five cones in the park. Also, games will be an excellent help for the development of mathematical abilities: with real objects ( cubes, pyramids, the Tower of Hanoi, constructor), desktop (lotto, dominoes) and even role-playing (“Shop”, “Traffic Light”, "Cook").

Games on the phone or computer might be useful. For example, games for the development of a city or some kind of ecosystem in conditions of limited resources teach you to combine moves, calculate options.

Suitable for schoolchildren are educational cards, logic exercises and puzzles, age-appropriate board and intellectual games, puzzles.

The competitive moment is another stimulus for the development of mathematical abilities. Therefore, participation in olympiads and mathematical competitions should not be neglected.

- Photo

- Getty Images

Why do many kids in school stop loving math?

Skysmart Academic Director of Mathematics

There are many studies showing that the better a child gets in math, the more they like it. And vice versa - the worse the results, the less interest. Often in such a situation, we get a spiral movement: the child did not learn some topic at school, received a low grade, against this background, he develops a bad attitude towards mathematics, which results in even worse results, and so on. Such a snowball - and as a result we get a huge number of guys who consider themselves "humanitarians", although under a different set of circumstances (as well as the approach of teachers and parents) they would have shown excellent results in the natural sciences.

Such a snowball - and as a result we get a huge number of guys who consider themselves "humanitarians", although under a different set of circumstances (as well as the approach of teachers and parents) they would have shown excellent results in the natural sciences.

Ideally, this spiral should be reversed. For example, we give tasks that the student can cope with, thus forming a good attitude towards mathematics, reinforcing this with interesting material and presentation. Mathematics can be practiced at any age, as soon as the baby begins to count, there are many different methods for early preschool development. The main thing is that it brings pleasure.

What do children's mathematical abilities depend on: genetics, efforts, training started on time?

Deputy Head of Education at the School of Programmers, teacher of mathematics and data analysis

There are no early signs of a mathematical mindset, because there is no so-called mathematical mindset. This is one of the myths that has been circulating in society for a long time.

This is one of the myths that has been circulating in society for a long time.

Lack of understanding of mathematics does not make anyone a humanist. What makes a person a humanitarian is his ability to understand the humanitarian discipline: to know the tools and be able to interpret phenomena. A person working in the humanitarian field is not limited in any way in his ability to understand mathematics. It just requires the study of a completely different toolkit and ways of interpreting phenomena. The question of their study depends on the desire, but not on the initial predisposition.

That a penchant for the humanities or the exact sciences is genetically inherited is another myth. The genetic mechanisms that appeared billions of years ago cannot in any way influence the concepts that appeared in the 16th century (it was then that the philosopher Francis Bacon classified the sciences into the categories closest to us). So the humanities and techies are definitely not because of genetic characteristics.

How to develop mathematical skills?

Mathematical skills can and should be developed at almost any age. And this development should go from the question “Why?”:

— Why does this mathematical formula work?

- Why do computers run on zeros and ones?

If you push the child to the question "Why?" in mathematics, by answering it, he will develop mathematical tools. This, of course, must be done. But asking this question in other areas is also essential for comprehensive development.

When they talk about developing mathematical abilities, they mean only one of the tools for working with patterns. And math is a great tool for that. But do not forget that he is not the only one. After all, there is, for example, formal logic. But it is even more important to remember that in addition to patterns, there is an interpretation. And one cannot develop mathematical abilities, which are usually understood simply as the ability to count, without developing the ability to interpret phenomena.

Head of the SIDS project, head of the psychological service of the CPM, psychologist of the online school "Coalition", specialist in working with children.

It is necessary to instill in children a love of learning gradually, the optimal age is 3-4 years. There is nothing to worry about if the dates are slightly shifted, because everything depends on the individual characteristics of the development of the organism.

Parallels with real life should be drawn to make it easier for a child to master the world of mathematics: explain to the child where the exact sciences are used, how they affected the formation of society and the creation of inventions that used to seem fantastic.

Start with simple addition and subtraction calculations, then add division and multiplication, combine examples. Show your child how to compare indicators, introduce him to geometric shapes. During walks or home gatherings, ask to find shapes in space and count the number of objects.

During walks or home gatherings, ask to find shapes in space and count the number of objects.

How to determine what is closer to a child - mathematics or the humanities

You can determine this either with a child psychologist or career guidance specialist, or on your own at home. You should observe the child and answer a few questions of the test.

You bought a new toy and gave it to your child. How does he interact with her?

-

Carefully examines, disassembles and reassembles, passionately examines each component.

-

Gives the toy its own story, "acquaints" it with other toys, creates interpersonal communication between objects.

You give your child a book with fun tasks and puzzles. His reaction is :

-

Looking for a solution with pleasure, considering various options and combinations.

-

Performs a task at random to complete the collection faster.

In the company of other children, your child:

-

Finds something to do alone, constructs something.

-

Gathers everyone around him, assigning roles to the participants in the game.

You are telling a fairy tale to a child. His actions:

-

Requires an explanation of all unusual phenomena in terms of logic.

-

Thinks out the development of events, adds mythical characters.

While studying the child:

-

Works with difficulty with a large amount of information, long text, does not like to learn large blocks of material, prefers interaction with numbers and tasks.

-

Dedicated to the humanities and creates his own short stories.

If more than 1 answers, this indicates the child's mathematical inclinations, 2 - about the humanities.

Lyubov Vysotskaya

Scientists have found out what children's mathematical abilities depend on

https://ria. ru/20201022/mozg-1581057464.html what children's mathematical abilities depend on - RIA Novosti, 10/23/2020

ru/20201022/mozg-1581057464.html what children's mathematical abilities depend on - RIA Novosti, 10/23/2020

Scientists have found out what children's mathematical abilities depend on

German neuroscientists have studied the relationship between variations in certain genes, the volume of the cerebral cortex and mathematical abilities in children. Results ... RIA Novosti, 23.10.2020

2020-10-22T21: 00

2020-10-22t21: 00

2020-10-23t12: 01

Science

Germany

Health

Biology

neurophysiology

neurobiology

social navigator

/html/head/meta[@name='og:title']/@content

/html/head/meta[@name='og:description']/@content

https:/ /cdnn21.img.ria.ru/images/156073/19/1560731952_0:75:1440:885_1920x0_80_0_0_dd6b81676e0b93c5fdb3e16f5daa929a.jpg

MOSCOW, Oct 22 — RIA Novosti. German neuroscientists have studied the relationship between variations in certain genes, cortical volume and mathematical ability in children. The results of the study were published in the journal PLOS Biology. It is known that mathematical abilities are inherited and are associated with several genes that express proteins in the brain. But until now, it was not clear how these genes affect brain development, and how their variations are critical for the manifestation of mathematical abilities at an early age. To fill this gap, scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Cognitive Research in Human and Brain, led by neuropsychologist Michael Skeide ( Michael Skeide, together with colleagues from the University of Leipzig and Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, conducted a study of the volume of the cerebral cortex in preschool children to predict their ability in mathematics in the lower grades of school, and then tested their predictions in practice. Initially, in the study 178 ordinary children from three to six years old who did not have special mathematical training participated. Then, a few years later, the scientists compared the data with the results of math tests when these children were already between seven and nine years old.

The results of the study were published in the journal PLOS Biology. It is known that mathematical abilities are inherited and are associated with several genes that express proteins in the brain. But until now, it was not clear how these genes affect brain development, and how their variations are critical for the manifestation of mathematical abilities at an early age. To fill this gap, scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Cognitive Research in Human and Brain, led by neuropsychologist Michael Skeide ( Michael Skeide, together with colleagues from the University of Leipzig and Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, conducted a study of the volume of the cerebral cortex in preschool children to predict their ability in mathematics in the lower grades of school, and then tested their predictions in practice. Initially, in the study 178 ordinary children from three to six years old who did not have special mathematical training participated. Then, a few years later, the scientists compared the data with the results of math tests when these children were already between seven and nine years old. The scientists used genotyping and brain imaging methods using magnetic resonance imaging. They analyzed 18 genetic variants of single nucleotide polymorphisms that affect the block of DNA, which includes ten genes that previous studies have identified as responsible for mathematical ability in children. They then studied the relationship between these variants and the volume of gray matter, consisting of nerve cell bodies, in the brains of children. . Finally, they identified areas of the brain where gray matter volume correlated with math test scores. The scientists found that the ROBO1 gene regulates prenatal growth of the outermost layer of neural tissue in the brain and gray matter volume in the right parietal cortex, an area of the brain that plays a key role in shaping the idea of quantity and the development of the data processing system. Researchers have found that the anatomical differences determined by this gene are formed at a very early age, and by the age of seven or nine are already clearly manifested in tests in mathematics, as well as the fact that a fundamental genetic component of the quantitative data processing system is associated with the early development of the parietal cortex.

The scientists used genotyping and brain imaging methods using magnetic resonance imaging. They analyzed 18 genetic variants of single nucleotide polymorphisms that affect the block of DNA, which includes ten genes that previous studies have identified as responsible for mathematical ability in children. They then studied the relationship between these variants and the volume of gray matter, consisting of nerve cell bodies, in the brains of children. . Finally, they identified areas of the brain where gray matter volume correlated with math test scores. The scientists found that the ROBO1 gene regulates prenatal growth of the outermost layer of neural tissue in the brain and gray matter volume in the right parietal cortex, an area of the brain that plays a key role in shaping the idea of quantity and the development of the data processing system. Researchers have found that the anatomical differences determined by this gene are formed at a very early age, and by the age of seven or nine are already clearly manifested in tests in mathematics, as well as the fact that a fundamental genetic component of the quantitative data processing system is associated with the early development of the parietal cortex. The authors believe that by studying the genetic variations of ROBO1 and the volume of the right parietal cortex in young children, one can accurately predict their mathematical abilities in the future.

The authors believe that by studying the genetic variations of ROBO1 and the volume of the right parietal cortex in young children, one can accurately predict their mathematical abilities in the future.

https://ria.ru/20201022/koronavirus-1581028171.html

https://ria.ru/20201008/muzyka-1578840431.html

Germany

RIA Novosti

9000 1 9000 3000 9000 4.796

7 495 645-6601

FSUE MIA "Russia Today"

https: //xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

2020 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 9000 RIA Novosti

1

5

4.7

96

7 495 645-6601

Rossiya Segodnya

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

News ru-RU

https://ria.ru/docs/about/copyright.html

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/

RIA Novosti

1

5

4. 3

3

96

7 495 645-6601

Rossiya Segodnya 95 645-6601

Federal State Unitary Enterprise MIA Russia Today

https: //xn---C1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/Awards/

RIA Novosti

1

5

4.7 9000 9000

Internet- [email protected]

7 495 645-6601

Rossiya Segodnya

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

social navigator

Science, Germany, Health, biology, neurophysiology, Neurobiology, Social navigator

MOSCOW, October 22 - RIA Novosti. German neuroscientists have studied the relationship between variations in certain genes, cortical volume and mathematical ability in children. The results of the study are published in the journal PLOS Biology.

Mathematical ability is known to be inherited and is associated with several genes that express proteins in the brain. But until now, it was not clear how these genes affect brain development, and how their variations are critical for the manifestation of math abilities at an early age.

To fill this gap, scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Research, led by neuropsychologist Michael Skeide, together with colleagues from the University of Leipzig and the Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg, conducted a study of the volume of the cerebral cortex in preschool children to predict their math ability in elementary school, and then tested their predictions in practice.

Initially, the study involved 178 ordinary children from three to six years old who did not have special mathematical training. Then, a few years later, the scientists compared the data with the results of tests in mathematics, when these children were already from seven to nine years old.

October 22, 2020, 16:27Science

Scientists have established how coronavirus affects the nervous system

Scientists used genotyping and brain imaging methods using magnetic resonance imaging. They analyzed 18 genetic variants of single nucleotide polymorphisms that affect the block of DNA, which includes ten genes that previous studies have been found to be responsible for mathematical ability in children.