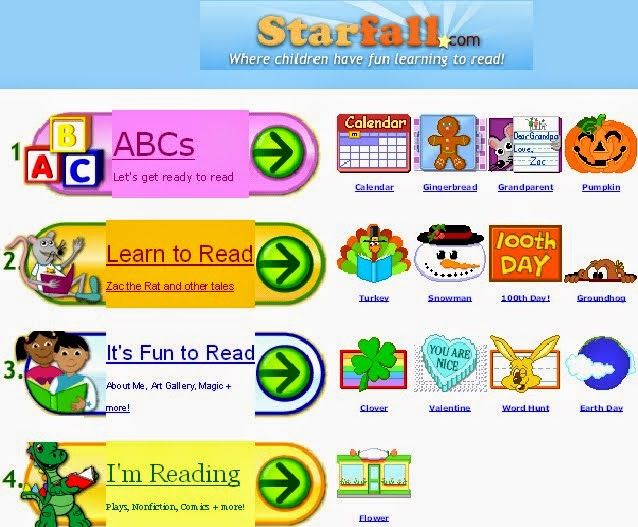

Early reader worksheets

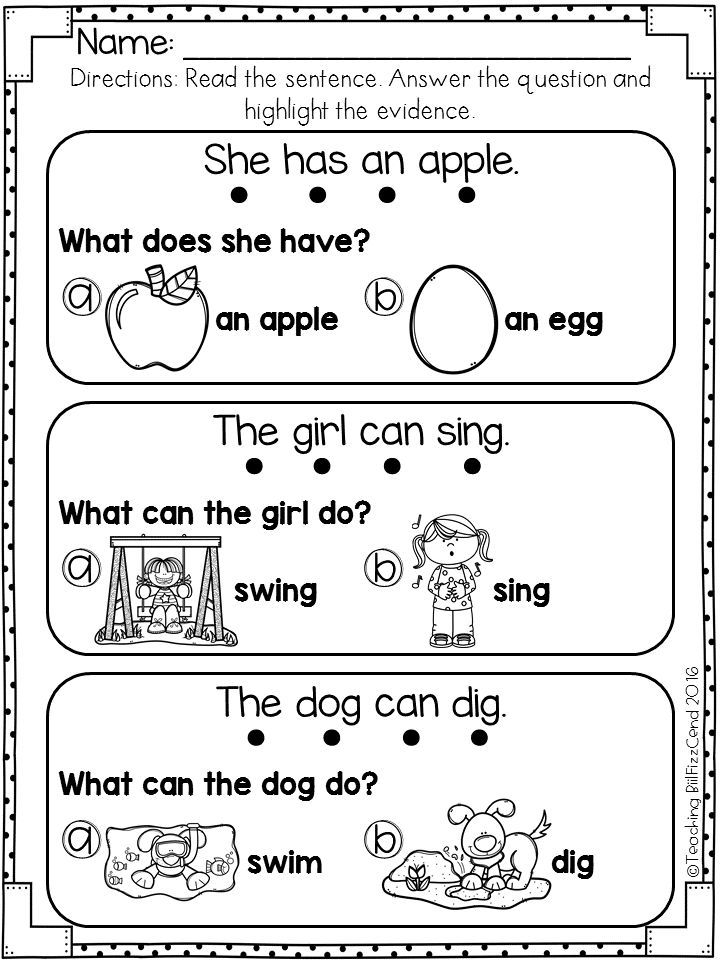

Early Literacy

Alphabet Worksheets

Students will trace, color, and write letters on these alphabet worksheets.

Mini-Books

Assemble and read these simple mini-books for very young readers.

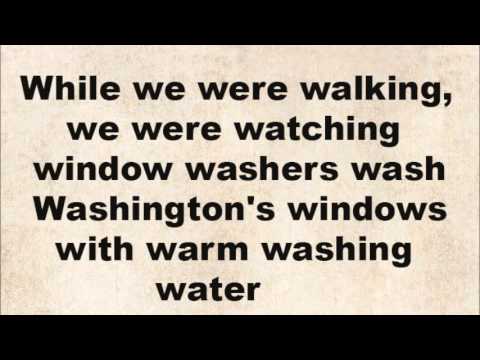

Poems and Poetry

Looking for cute poems to share with your class? We have lots!

Printing Letters

Trace and print each letter of the alphabet. We have worksheets with upper and lowercase letters.

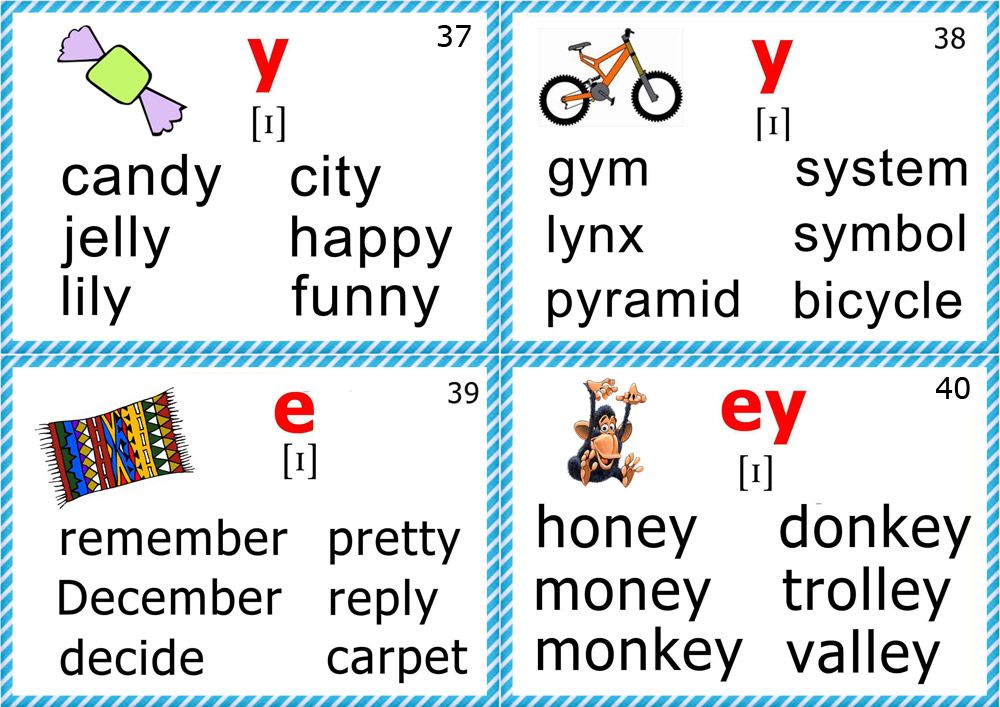

Phonics Worksheets

We have a page of worksheets for each consonant and vowel sound, as well as blends and digraphs.

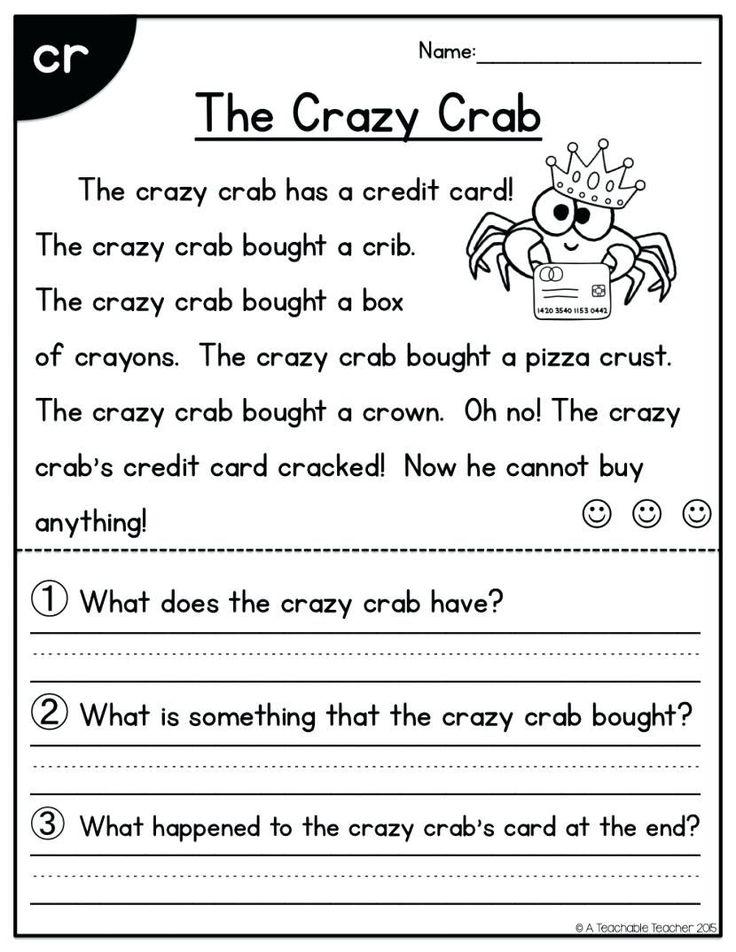

Phonics: Consonant Blends

This page will link to you hundreds of phonics worksheets for teaching consonant blends.

Phonics: Vowel Sounds

Practice reading and recognizing words with long and short vowel sounds.

Phonics Word Wheels

Assemble the word wheels. Then kids can read the word family words aloud as you spin the wheels.

Rhyming Worksheets

Learn about rhyming words with these activities.

Sentences (Basic Building Sentences)

With these cut-and-glue activities, young children can build very simple sentences.

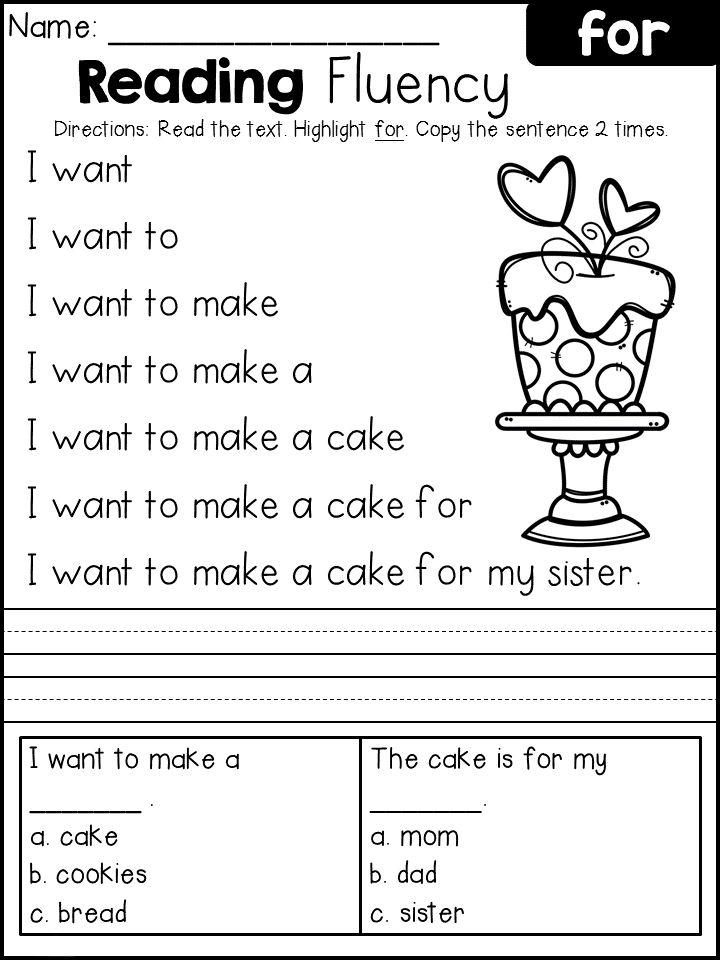

Sentences (Basic Writing)

Write basic sentences with simple, repeated beginnings. Easy writing activities for Kindergarten and first graders.

Sight Word Units

We have an entire curriculum of 30 sight word units. Each unit has a take-home list, practice worksheets, reading practice tools, and assessment sheets. We recommend doing one unit per week.

Sight Words (Individual Words)

Here you'll find a list of over 150 sight words. Each word has a several worksheets. (For example, you'll find several worksheets for teaching students to read and write the word that.)

(For example, you'll find several worksheets for teaching students to read and write the word that.)

Sight Words (Dolch Words)

Use these flashcards, bingo games, checklists, and worksheets to help your students master all 220 Dolch sight words.

Sight Words (Fry Words)

We have word wheels, games, and worksheets to help your kids master the Fry Instant Sight Words.

Word Family Units

This page contains a collection of word families units. Includes -an words, -am words, -ear words, -ack words, -ail words, and dozens more. Each unit contains worksheets, word wheels, flashcards, and sliders.

See Also:

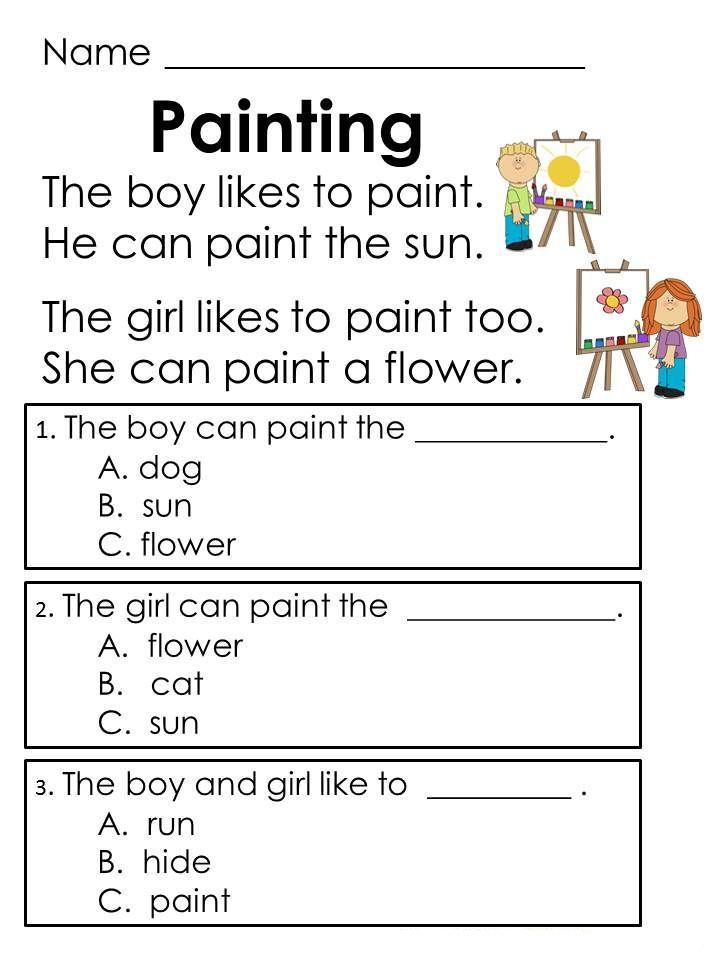

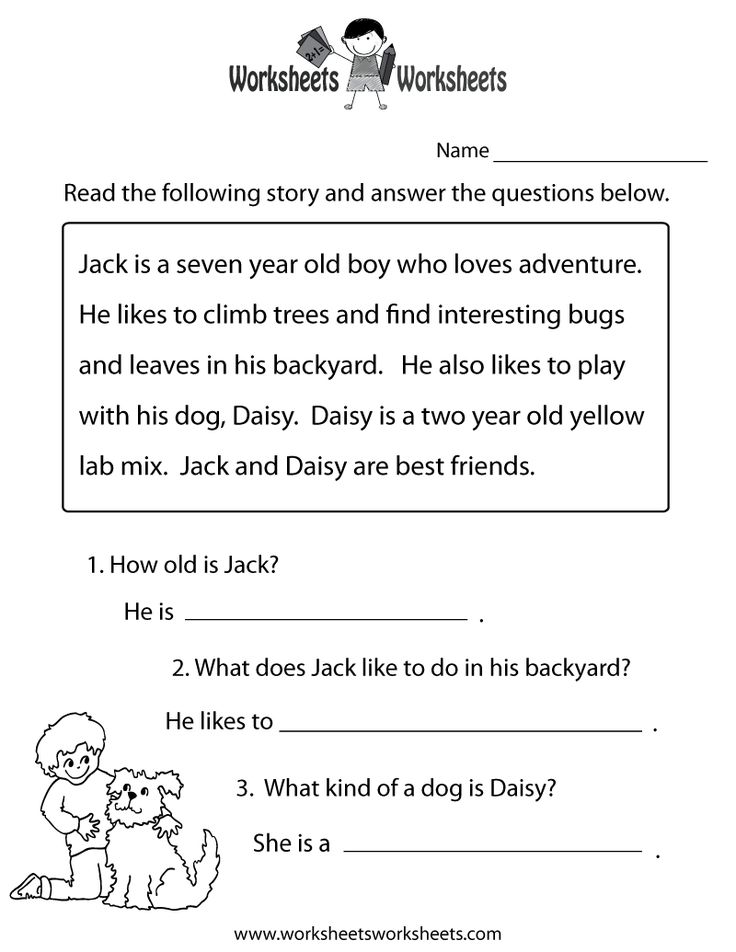

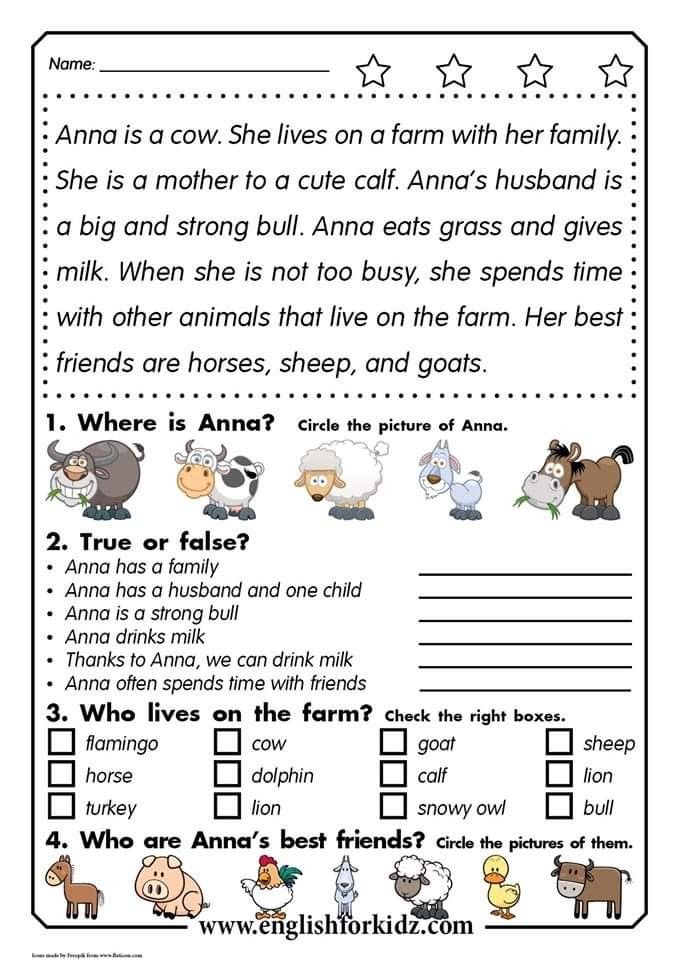

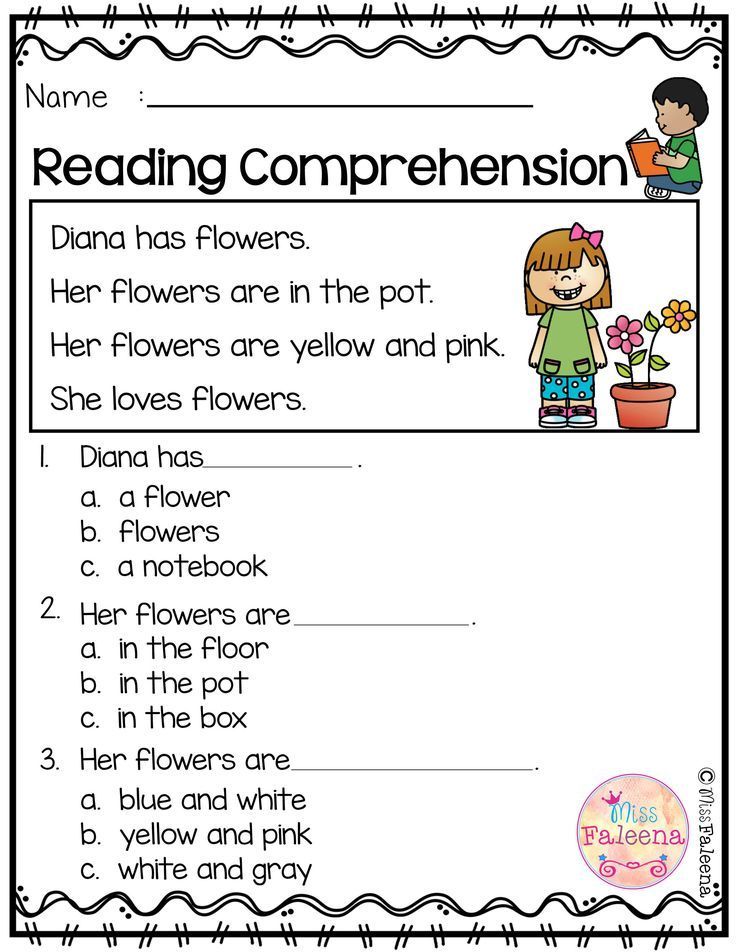

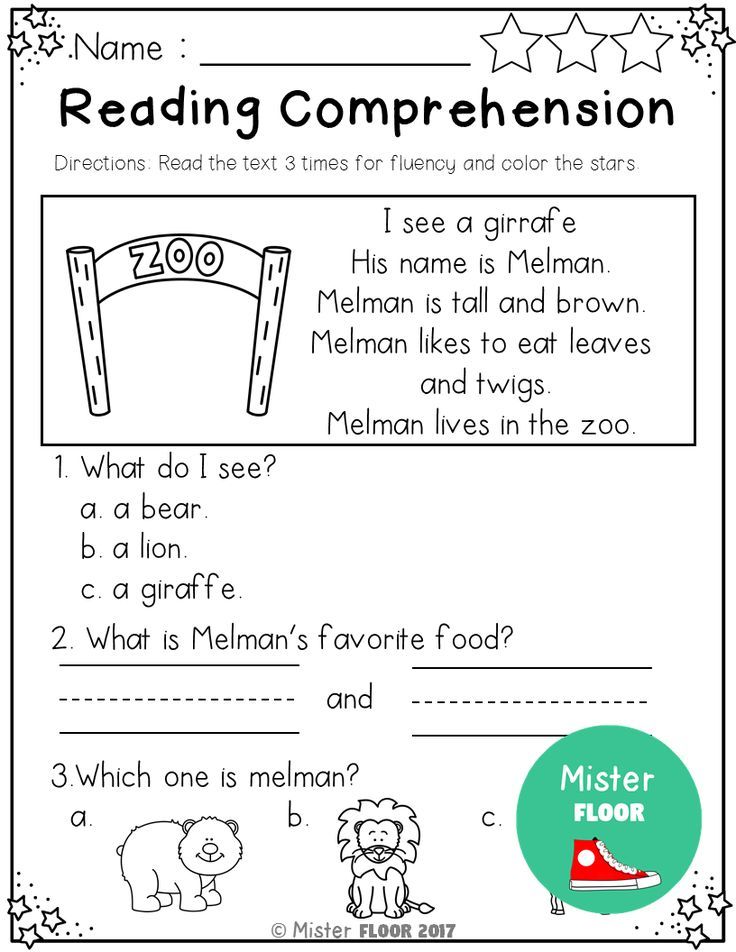

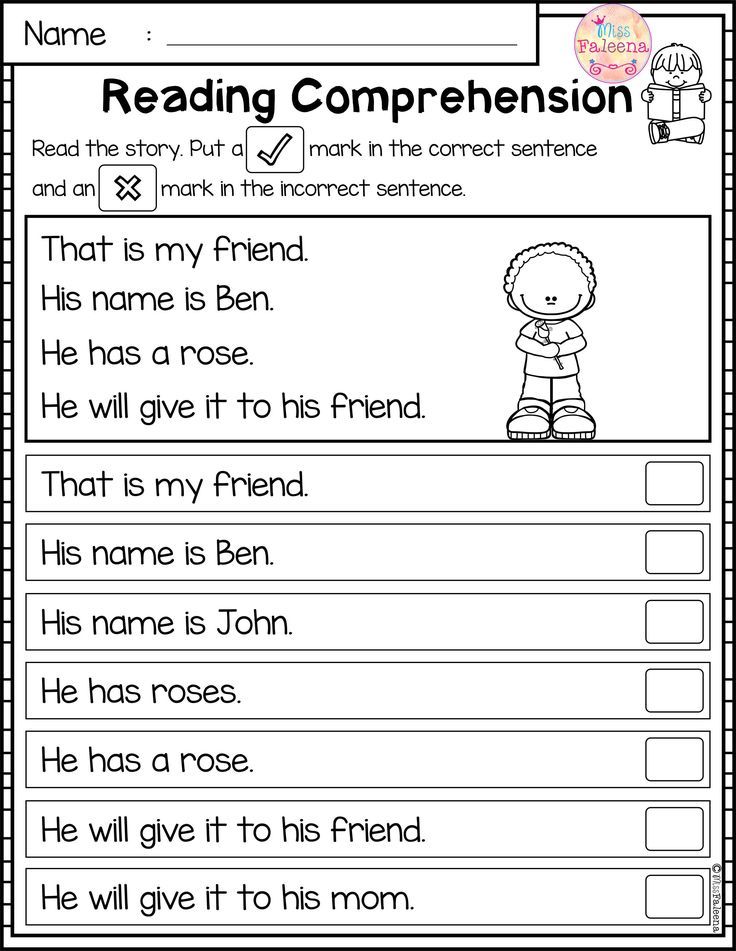

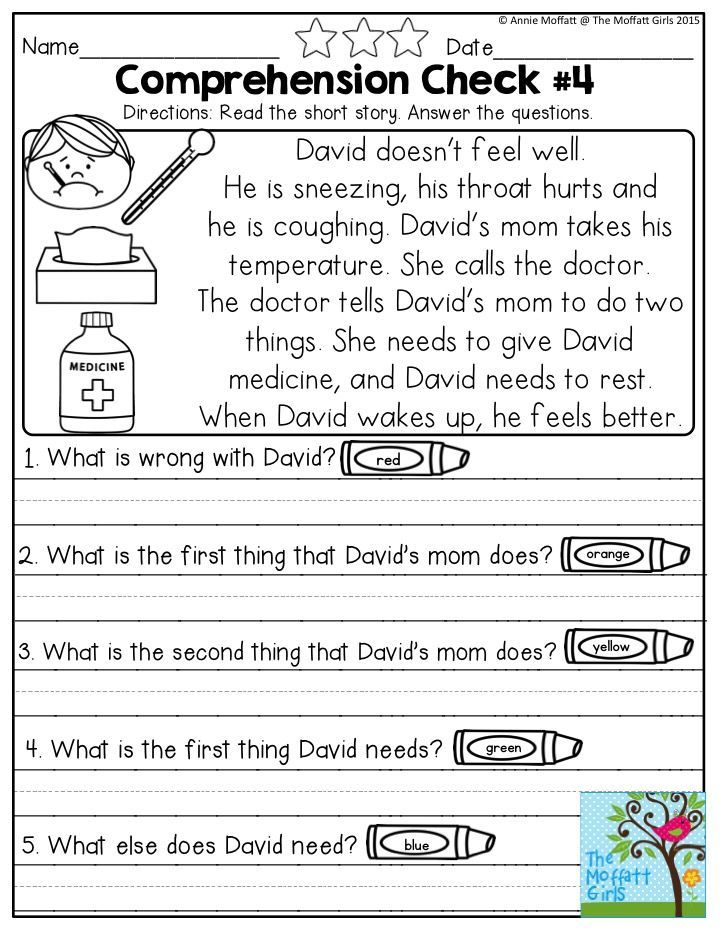

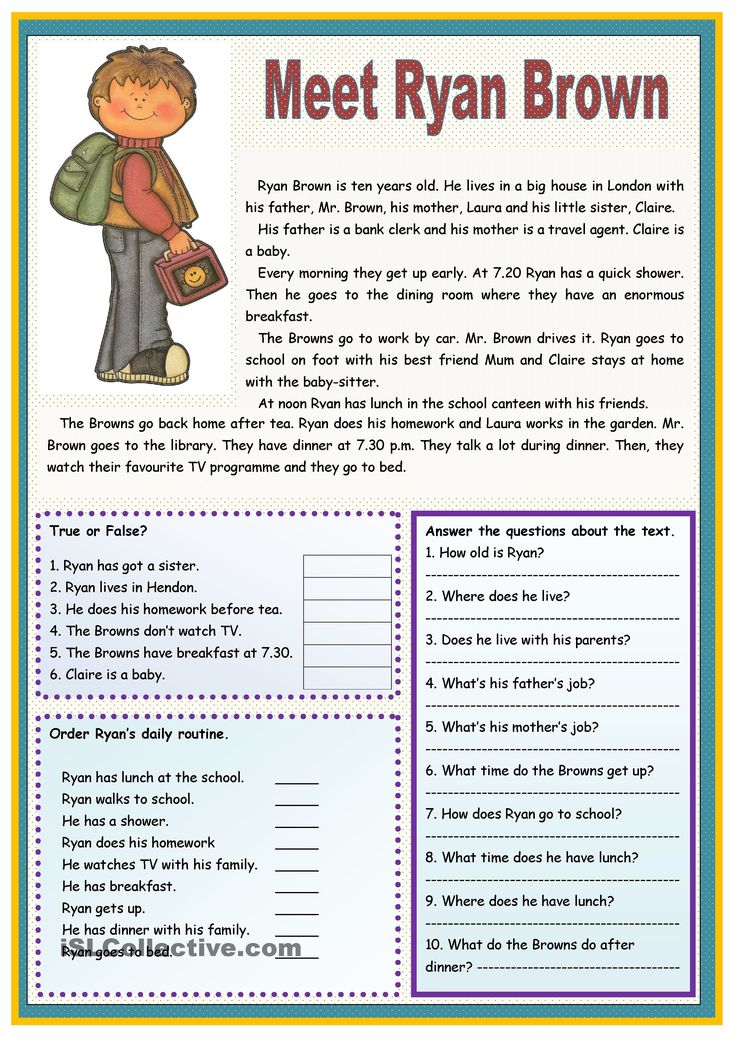

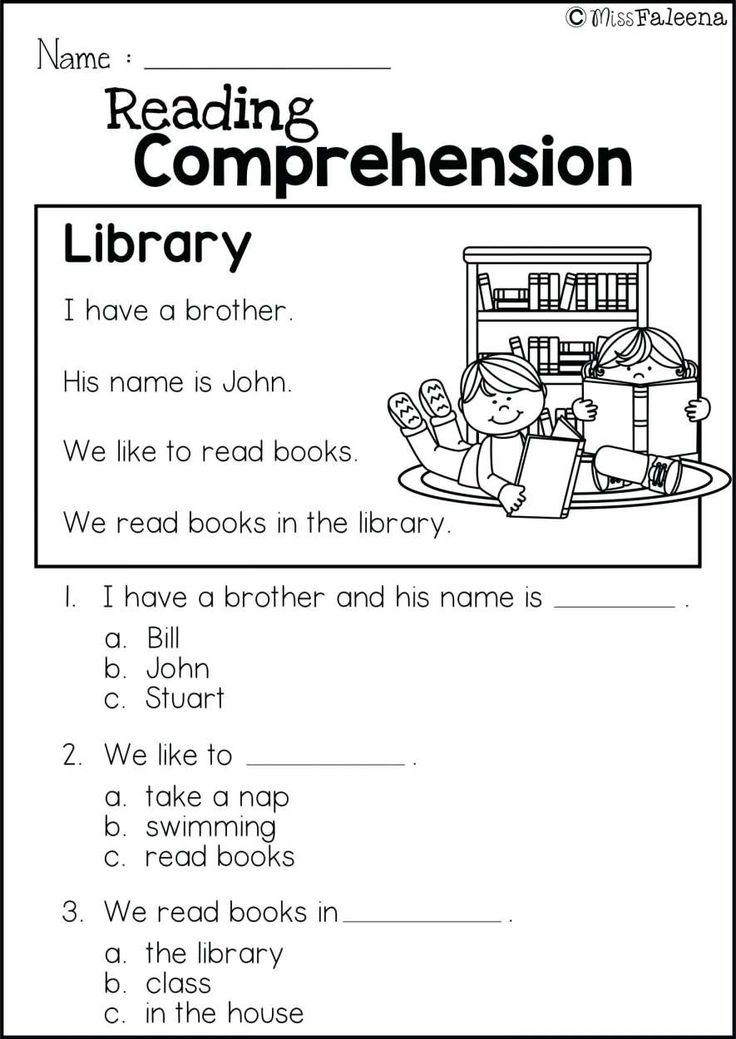

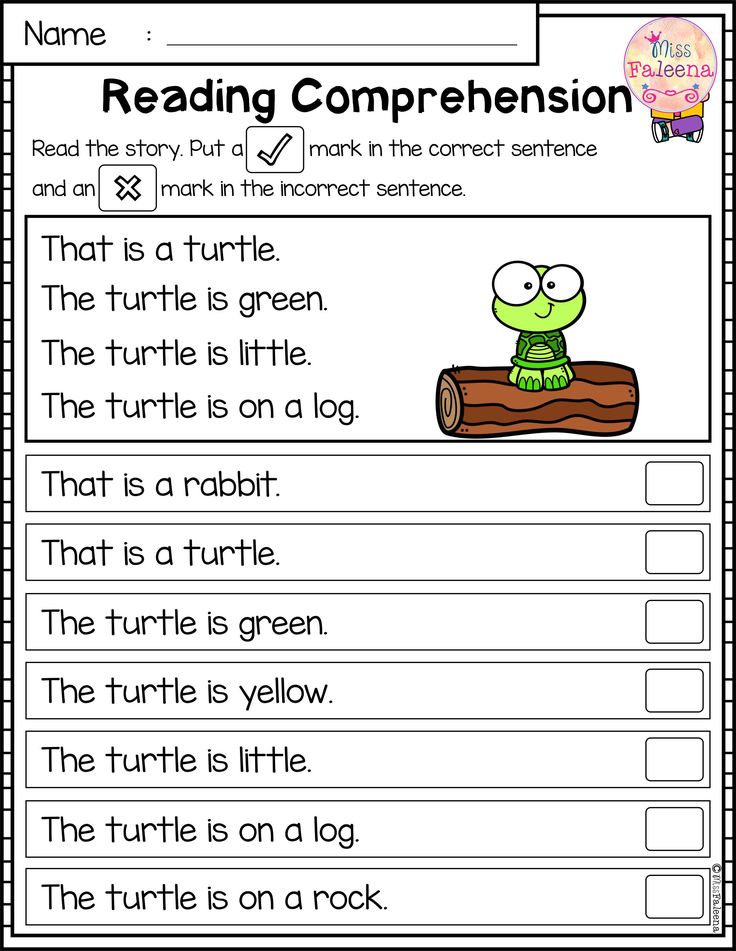

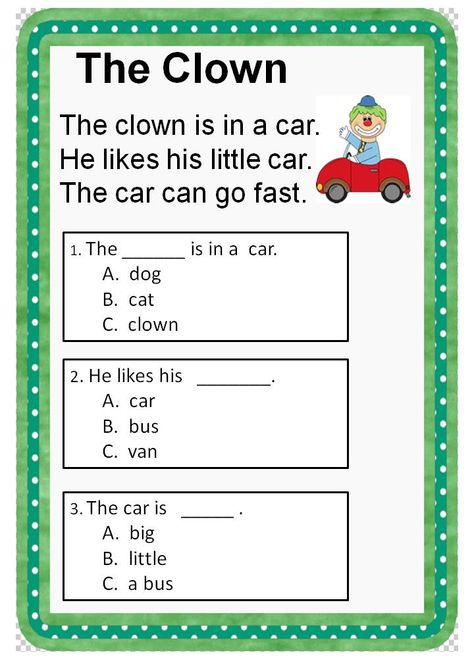

First Grade Reading Comprehension

We have simple reading comprehension passages with questions for first graders.

First Grade Spelling

We have a full first grade spelling curriculum, complete with printable word lists, worksheets, and test forms.

Kindergarten Worksheets

We have hundreds of worksheets and printable activities for Kindergarten and Pre-Kindergarten students. Browse the entire collection.

Theme Printables

Themes include farm worksheets, zoo animal printables, sea life activities, and apple worksheets.

Reading Worksheets | All Kids Network

Reading worksheets are the perfect tool to help your child develop a love for reading at an early age. By giving your child the basic tools they need to read at an early age, you can increase their chances of becoming a great reader. This collection of free reading worksheets covers a variety of subjects like alphabet recognition, phonics, sight words, comprehension and more. Each reading worksheet in this collection is easy to print in either color or black and white to meet your needs.

This comprehensive collection of alphabet worksheets will help get your child on their way. ">A child's ability to recognize the letters of t...

This group of free reading worksheets is focuss...

Correlating sounds with letters and groups of l...

Check out this set of printable sight word work...

Choose a word from the word bank to complete ea...

We created this set of word recognition workshe...

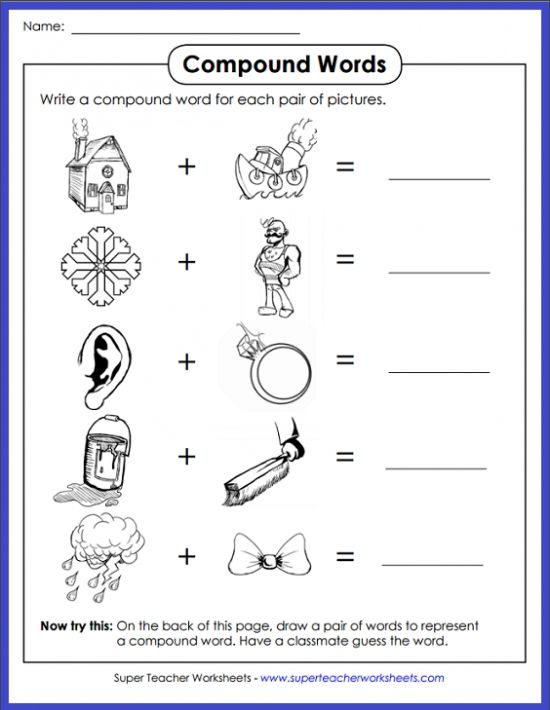

We have a nice collection of compound word work...

Follow the instructions under each picture to k...

Check out our free worksheet geared towards tea...

Help kids improve their vocabulary with our col...

This collection of free worksheets is dedicated...

This set of free phonics worksheets is geared t...

Use the pictures to help unscramble the letters...

This set of names worksheets will help teach ch...

Check out our set of free worksheets focussed o...

Groups of different worksheets for each of the ...

Check out our collection of synonym worksheets ...

Related Worksheets

Find More Worksheets

Popular

Related Crafts

Find More Crafts

Related Activities

Find More Activities

Related Teaching Resources

Find More Teaching Resources

Workstation > Workstation Catalogizer > General user interface > r.

o.WORKLIST > Input worksheet

o.WORKLIST > Input worksheet In this section:

.TRE - radar list (FmtMnu=fmt31.tre)

Input worksheet |

Input worksheet.

RL is |

a screen form that is used to enter/correct one (current) database document.

A worksheet (RL) can be viewed as an input script that provides input/adjustment of a certain set of data elements (fields) - placed in a certain order.

Depending on the database, the system offers a set of different input scenarios, ie. various types of radar.

In the case of the Electronic Catalog database, the system offers a set of RLs intended for entering/correcting various types of bibliographic description.

To select and set a specific worksheet |

serves as:

•corresponding toolbar drop-down menu or

•main menu mode Correction / Entry Worksheet / Select.

When entering a new document |

the user must explicitly (on their own) select and install the desired radar.

| When calling for correction of a previously entered document |

(already having an internal MFN number), the system automatically selects and sets the RL - the one with which this document was entered (or, more precisely, the one indicated in the special field of this document).

But this does not exclude the possibility of selecting and setting any of the existing RLs for the previously entered document.

Radar installation.

Document type selection.

The entry worksheet can consist of several pages.

Bookmarks |

The transition from one page to another is done using bookmarks.

The name of the tab (and, accordingly, the name of the page) reflects the composition and purpose of the data elements grouped on the RL page.

. those data of a real document that have no place on the main pages of the RL.

Each page of the RL is a tabular form.

Additional accelerators |

|

| Additional accelerator buttons have been introduced into the interface for entering repeating fields using RL subfields (see the figure below), which allow you to go to the next or previous repetition of the field with one click, saving or refusing to enter. |

DEFAULT VALUES as FORMAT |

|

|

It is now possible to set DEFAULT VALUES in the RL fields (files of type WS) as FORMAT (explicit or as a format name with a preceding @ symbol) This does not cancel the ability to set default values in the RL fields "in the old way" (in the form of direct values or in the form of a special reference to the INI file). It should be recalled that the default values in the RL fields are used when entering NEW documents

It is also possible to set DEFAULT VALUES in RL subfields (WSS files) - which was not possible in previous versions of the system. Default values in RL subfields can be given either as RIM values or as FORMAT (either explicitly or as a format name preceded by @).

|

.TRE filesRL list (FmtMnu=fmt31.tre) |

|

| _1 It is now possible to use hierarchical directories (files of the TRE type) to represent the main lists. |

RL list (FmtMnu=fmt31.tre)

List of input worksheets using .tre type hierarchical directories

See also:

Page of the working sheet of input

Working data sheets in EC (cataloging instructions)

Rules for filling out fields (cataloging instructions)

Cataloger Instructions

Work with elements of the main drop -down menu

22 TRE files for lists

What peasants and workers read 150 years ago: from the adventures of Tarzan to Karenina daily newspapers and popular books, and, as in the first Soviet libraries, workers massively read Cement by Gladkov and Tarzan by Burroughs.

Daily newspapers and picture books

Historically, reading did not develop in Russia in the same way as in Western Europe: there was a smaller educated public and the level of education itself was lower. Russia did not experience the Renaissance, the Reformation, or the Industrial Revolution that promoted reading elsewhere. Therefore, reading became a truly mass occupation at most 150 years ago, when the teaching of elementary literacy embraced, as they used to say, the masses of the people. The increase in literacy rates, in turn, was directly related to the emergence of, if not compulsory, then at least affordable primary education. In Russia, this happened along with the zemstvo reform of 1864, which gave the zemstvo school.

Therefore, reading became a truly mass occupation at most 150 years ago, when the teaching of elementary literacy embraced, as they used to say, the masses of the people. The increase in literacy rates, in turn, was directly related to the emergence of, if not compulsory, then at least affordable primary education. In Russia, this happened along with the zemstvo reform of 1864, which gave the zemstvo school.

Historical circumstances influenced reading no less: for example, during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, newspapers in the village began to be subscribed not only by priests and teachers. And with the beginning of the First World War, interest in the newspaper grew even more, especially after it was forbidden to sell vodka (according to a survey in the Moscow province in 1915 - excerpts from there are cited by cultural sociologist Abram Ilyich Reitblat).

In his extensive work From Bova to Balmont, Reitblat also notes that the appearance of cheap periodicals, the so-called street leaflets, increased the interest in reading among the uneducated urban population. And popular books, picture books, for many have become guides to the world of reading. Although Nekrasov still mocked them:

And popular books, picture books, for many have become guides to the world of reading. Although Nekrasov still mocked them:

"When a peasant is not Blucher

And not my lord stupid -

Belinsky and Gogol

Will he carry you from the market?"

(Blucher is the hero-victorious Napoleon at Waterloo, whose portrait was popular in the form of popular prints. By “my lord stupid” we mean the popular print edition of Matvey Komarov “The Tale of the Adventure of the English Milord George and the Brandenburg Margravine Frederick Louise.” — Note ed.)

Regarding the last author, by the way, Nekrasov was mistaken: it was Gogol's stories that served as one of the main substrates for popular prints and expositions "for the people." Along with the folklore heroes Bova Korolevich and Yeruslan Lazarevich, Taras Bulba from the story of the same name and the blacksmith Vakula from Gogol's "The Night Before Christmas" became popular characters in popular print books. In the original, the complex Gogol imagery was often incomprehensible to the peasants even in a simplified presentation.

In the original, the complex Gogol imagery was often incomprehensible to the peasants even in a simplified presentation.

Read

Sunday Schools and Posrednik Publishing House

If the development of reading differed, then the study of this reading went in the same direction as in Western Europe. The habits of the reading public were studied mainly to teach them to read what they needed to read, and not what the public wanted to read. In Europe, too, the idealistic Social Democrats dreamed of developing the workers by gradually transferring them to the reading of Karl Marx and the theoretician of Marxism, Karl Kautsky. The people themselves gravitated toward "literature that leads away from reality" - novels with sequels, adventure books, and later detective stories.

The people themselves gravitated toward "literature that leads away from reality" - novels with sequels, adventure books, and later detective stories.

It is more accurate to call such a study of reading work with the reader, and two wings, as it were, took part in this work: on the one hand, private educators, on the other, state institutions (for example, Literacy Committees and the Ministry of Public Education, more precisely, its special department) . Both liberals and guardians agreed that the reader must be taught, educated, and compiled for him the indexes of necessary reading. On the whole, the Enlighteners believed that when working with the people, one had to study, in the words of M. Milyukov, an employee of the Knizhnik magazine, "silent requests" - meaning that the people themselves were silent for the time being.

The experience of the teacher and educator Khristina Danilovna Alchevskaya is interesting here. This woman, who taught herself to read (her father believed that a girl did not need an education at all), devoted her whole life to peasant education. Her Sunday women's school in the Kharkov province not only provided primary education to many girls and women, but also became a field for collecting information for the future three-volume book What to Read to the People, which won an award at the World Exhibition in Paris in 1889. In this work, in addition to lists and annotations, there is the most valuable anthropological material - records of conversations from loud readings and records of students' statements about books.

Her Sunday women's school in the Kharkov province not only provided primary education to many girls and women, but also became a field for collecting information for the future three-volume book What to Read to the People, which won an award at the World Exhibition in Paris in 1889. In this work, in addition to lists and annotations, there is the most valuable anthropological material - records of conversations from loud readings and records of students' statements about books.

Judging by these very statements, Tolstoy's metaphor, even from his folk stories, also did not always reach the inexperienced reader. Although Tolstoy himself at first adhered to the idea “the people need to be educated” (and wrote “ABC” and “Stories for Children” on this wave), and then moved on to the idea “you need to learn from the people” - in his texts, this, apparently, is not affected. Alchevskaya's students often could not answer questions about the text, since they did not mean a direct answer, but a rethinking of the metaphor and understanding of the motive.

Alchevskaya's students often could not answer questions about the text, since they did not mean a direct answer, but a rethinking of the metaphor and understanding of the motive.

Perhaps the most important thing that Tolstoy did for public reading was not the ABC, not the Yasnaya Polyana school, and not the pedagogical magazine Yasnaya Polyana, but the Posrednik publishing house. The idea of the publishing house was to replace cheap popular literature, which was considered harmful, with more decent books for public education. However, ofeni (dealers in all sorts of trifles, including popular prints. - Ed.) were reluctant to take the books of the Intermediary, since they were a little more expensive than popular prints.

In 1884, on the initiative of Leo Tolstoy, the Posrednik publishing house was established, which produced literature that was more informative than in popular books: literary texts and educational articles. The photo shows the covers of several books published in 1910 and 1912 / State Museum of L. N. Tolstoy

N. Tolstoy The first contained questions about what kind of books readers like and dislike and why. The second was related to a new publishing project for the release of popular science books and practical manuals, and it asked what superstitions needed clarification and what practical issues the peasants needed the help of the book. In general, work on written questionnaires was traditional for the educators of the post-reform era: almost all of them compiled such questionnaires and received answers, for example, from enthusiastic teachers, self-taught peasants, and so on.

Miners-readers

There were also records of direct educational work done, for example, by the writer and ethnographer Semyon An-sky, who read books to miners in the 1880s. By the way, he noted that peasants and miners perceive books differently, primarily because their employment is structurally different: the peasant is constantly busy, if not with work, then with thoughts about work, and the miner comes home from his shift and is free.

At the same time, both peasants and miners had a special attitude towards “divine” books, perceiving them as a talisman, and interaction with them as soul-saving. This included not only religious literature, but also texts where angels or visions are present. The presence of such a plot element translated the book into "divine", and the presence of a devil, for example, made the book impious, and it was no longer acceptable to read it on a church holiday.

Semyon An-sky (Shloyme Zeinvil Rapoport) - writer, ethnographer, educator, who taught in the villages in the 1880s, worked in the mines, collected mining folklore. In the photo - Semyon An-sky talks with residents in one of the Jewish towns of Podolia / russiainphoto.ru At the same time, readers from the people did not distinguish between fantastic and real, devils and sorcerers for them were the same reality as a plow and a mine. It was especially unfortunate if, against the backdrop of a realistic narrative, one of the characters turned out to be a saint or an angel, and then the listeners felt awkward: they now could not judge the heroes of the book by the previous standard, and the opinions expressed earlier seemed sacrilege to them.

In general, books among the people were divided into "divine", fairy tales and worldly ones. The idea of fiction, according to An-sky, was far from the popular reader, he perceived moralizing texts as stories about a legendary past, and realistic stories as a real story: sometimes someone could even say that he knew the person in question in the book that it happened in his village, or to suggest that the writer visited the heroes and used a phonograph.

An important element in making a book appeal to listeners is that it points. I mean, she pointed out how to live, what is right and what is not. “Indicated! Everything is indicated”, “Evidence is proved!” - this is how, for example, the enthusiastic reviews of the miners about the book sounded.

In 1895, the book of the writer and popularizer of science Nikolai Rubakin "Etudes on the Russian Reading Public" was published - perhaps the first work in this area, made in a more descriptive manner. In the first part, he analyzes data from libraries and reading rooms, and in the second, he turns to letters, essays, and descriptions of individual readers. According to Rubakin, it is fiction of the lowest sort with titles like “Hands full of roses, gold and blood” that makes it possible to attract to reading, to give “get used to a thick book” to those who received, at best, a primary education. Special books "for the people" are not needed for this and are even useless. One of his correspondents made a very precise remark:

According to Rubakin, it is fiction of the lowest sort with titles like “Hands full of roses, gold and blood” that makes it possible to attract to reading, to give “get used to a thick book” to those who received, at best, a primary education. Special books "for the people" are not needed for this and are even useless. One of his correspondents made a very precise remark:

Nikolai Aleksandrovich Rubakin — writer, theorist of self-education, popularizer of science, who developed book and library science in Russia / wikimedia.org"The people do not need popular books, but cheap ones, because they are poor, not fools."

he doesn't understand, and so on. The normative and pedagogical framework, familiar to the second half of the 19th century, changed somewhat (but did not disappear completely) in 19The 1920s, when reading, after the elimination of illiteracy, became truly massive.

Soviet libraries

After the revolution and the Civil War, the study of readers was continued in general by the same cultural enlighteners - or at least people of the same formation. Their work was facilitated, first of all, by the fact that libraries became a centralized system subordinate to the Political Education Department, which made it possible, firstly, to explore large amounts of data, and secondly, obligated libraries to provide such data. It follows that these data were obtained under some administrative pressure and, more importantly, these were data on literate people who already used the library, which for 19The 20s was not yet something widespread.

Their work was facilitated, first of all, by the fact that libraries became a centralized system subordinate to the Political Education Department, which made it possible, firstly, to explore large amounts of data, and secondly, obligated libraries to provide such data. It follows that these data were obtained under some administrative pressure and, more importantly, these were data on literate people who already used the library, which for 19The 20s was not yet something widespread.

However, in the eyes of the ideologists of the new system, the primary task was not to form a new culture, but to create a patch in the form of culture, that is, quick learning about how the new state works and how one should behave in it. There was no time to wait for a new culture.

So, the researchers happily rushed into the development of methods for studying readers, cataloging them and, as we would say now, tagging: by social status, level of education, age, party membership. They tried all kinds of questionnaires and index cards, tried to oblige to leave reviews (“whoever does not leave, the next book will not be issued”), to keep readers' diaries. These attempts, as a rule, pursued two goals at once: to find out what the new reader is like, and to find out which books he prefers.

These attempts, as a rule, pursued two goals at once: to find out what the new reader is like, and to find out which books he prefers.

. The results of the survey turned out to be very monotonous: everyone loved Fyodor Gladkov's novel "Cement" and "useful books" - that is, books of practical purpose and those from which something informative could be extracted. In the 1920s, political and educational books written for the people were generally more analogous to popular and other grassroots literature: they allowed you to gently enter the world of reading and at the same time bring to the reader a certain set of necessary beliefs.

The drive for feedback sometimes reached almost caricatured forms. For example, G. Brylov publishes an article in the Red Librarian magazine about the experience of the Baltic Plant library with reader diaries, where they were forced to write down reviews about the books they read and questions to the librarian. The experience was an extreme case of coercion to reviews: a special diary was started for each reader, which the reader himself had to fill out. He was required to record what he read and looked through, and ask questions about what he read to the librarian in the same notebook. If someone shied away or did not write enough detail, the librarian demanded to rewrite and did not give out new books. Here is a fragment from Brylov's article:

The experience was an extreme case of coercion to reviews: a special diary was started for each reader, which the reader himself had to fill out. He was required to record what he read and looked through, and ask questions about what he read to the librarian in the same notebook. If someone shied away or did not write enough detail, the librarian demanded to rewrite and did not give out new books. Here is a fragment from Brylov's article:

“The essence of the system of diaries of readers is as follows: for each regular reader (except casual visitors), the reading room starts a diary in the form of a special notebook, ⅛ sheet in size, containing 32 pages of paper in a ruler. On the front side of the cover of the diary, the reader's number is written, his characteristic, written in the form of a cipher (for example, RMUNB means: worker, man, youth, i.e. 17-22 years old, lower education, non-partisan), last name, first name and patronymic. <...> On the front side of the cover, in addition to indicating the place for the mentioned information, it is printed: "A reader's diary .

.." (follows the name of the library-reading room). On the second page of the cover is printed "Reader's Memo". <…>

Write down in your diary what you read and looked through in the reading room today (titles of books, magazines and newspapers, titles of individual articles). Write your reviews about what you read and impressions; this will help the library to better select books and magazines. If you need any help or clarification of a question that interests you or an incomprehensible word or expression, write it down. Here in the diary you will get the answer. Use a diary for your notes about what you read, just like a memory book ... Write what books, newspapers, magazines you would like to have in the reading room. Point out the shortcomings ... and make your suggestions and wishes. When leaving the reading room, be sure to hand in the diary to the librarian.”

The memo ends with an appeal to the reader: "Write legibly."

According to the description of the researchers, the peasants constantly demanded the same books: novels by John Reed, Jack London, Upton Sinclair, Emile Zola, Les Misérables by Victor Hugo. True, it is not clear how exactly the peasants managed to read them: the fact is that, firstly, the collection of libraries in the 20s left much to be desired, and secondly, we are talking about rather complex translated literature, and it is difficult to imagine that Peasants who have recently passed the educational program will famously swallow Zola and Hugo.

True, it is not clear how exactly the peasants managed to read them: the fact is that, firstly, the collection of libraries in the 20s left much to be desired, and secondly, we are talking about rather complex translated literature, and it is difficult to imagine that Peasants who have recently passed the educational program will famously swallow Zola and Hugo.

Occasionally there are descriptions of curious reading practices. So, one reader checked Leo Tolstoy with the pre-revolutionary edition: did the Bolsheviks change anything? After making sure that they had not changed, he began to go to the library regularly. Separately, it is noted that the peasants read even during the sowing season, because they are "bored without a book." Sometimes the peasants asked: “I want to take it for the holidays”, “I want to take it for guests” - this is how the practices of the so-called secondary literacy were implemented in the conditions of the village, that is, mastering printed information “by proxy” - most often these were the practices of collective reading aloud.

Methodist-theorist of those years A. Vilenkin developed a method for processing reader reviews, which, together with another researcher Boris Bank, implemented in the works “The Village Poor and the Library” (1926) and “Peasant Youth and the Book” (1927). Both works were based on the material of the rural libraries of the Leningrad province. They studied the demand in general, not only for fiction, but also for what we would now call non-fiction literature. Here, for example, what reviews can be found there:

“In general, the novel is very good, and now they don’t write such novels. I would not have done the same as Anna Karenina. Why end your life if you got along with someone else. And if he quit, you can live on your own or go to another one.” (F., aged 21)

“I liked it very much. And how well the bourgeoisie and landowners lived, and found all the suffering for themselves. (M., 18 years old) ("Anna Karenina")

"An interesting novel about the past.

How wrong the revolutionaries were then. (M., 17 years old) (“Nov”)

"From this book I learned how the peasants suffered under serfdom." (M., 17 years old) ("Notes of a hunter")

“It's good that there are no noble nests now. Here we have a state farm instead. Liked the book. And it’s even better that they actually removed the nobility.” (M., 19 years old) (“Noble Nest”)

The most widely read authors among peasants are modern fiction writers (for example, Alexander Neverov), followed by pre-revolutionary fiction. Workers in similar studies, on the other hand, showed a “strong Americanization of demand” (the most popular authors are Jack London and Upton Sinclair). Although it is difficult to judge here how much something else was available to readers.

Most of the peasants' comments were laconic: the reader was unable to explain why he liked or disliked the book. The main criterion with which the peasant approached the book was practicality and usefulness, and the main dissatisfaction was that it was difficult to write.

"A useful concept of the February Revolution is given" (Vladimir Bakhmetiev, "Resurrection")

“Useful. Teaches what vodka leads to. (Alexander Neverov, "Avdoty's Life")

“Useful. An explanation of incomprehensible words and Morse code is placed. (Vladimir Vladimirsky, Emerald Mine)

Once, the American writer Upton Sinclair even wrote to the Central Statistical Office of the USSR (Central Statistical Office) asking how his novels are read. In response to this, Soviet librarians conducted a small study on which social groups read his novels - and answered the writer in print.

Readers of the 1920s - both workers and peasants - demanded concreteness in the text (it seems that it was easier for them to describe the plot in this way), an exciting and intense development of the action, and appreciated adventures. Therefore, books like The Red Devils by Pavel Blyakhin or Tarzan by Edgar Rice Burroughs were not only popular, but were enthusiastically retold in reviews. They did not understand and did not perceive reflections, philosophical and social concepts, speaking about them "one booza".

They did not understand and did not perceive reflections, philosophical and social concepts, speaking about them "one booza".

Most of the literature remained incomprehensible to the workers. They did not understand the books of Boris Pilnyak and Ilya Ehrenburg, at the same time they seemed to understand Lenin and even books about dialectics (it seems that in fact they were simply able to reproduce the concept itself). The author of the study found the reason in the "organic foreignness of petty-bourgeois literature." In all this, it is interesting to note how quickly and how strongly the workers and peasants began to look at books from the right side. Researchers constantly noted how easily they analyzed the text from a class point of view, which reflected their "revolutionary-communist integrity." This was important because it meant that political propaganda was working.

Sometimes the unexpected broke through these politically correct reviews, something like “I don't like to read about the city: the city is robbing us. Why should I feel sorry for him" or "I'm tired of the commissars". The researchers saw in this "the influence of the kulaks, faced with low political literacy."

The experiment moving on reached its limits: a movement of work correspondents appeared (freelance correspondents from the working environment. - Note ed.), who already had the strength and power to say what they like and what they don’t. Readers' conferences were held, where readers put forward their requirements for writers, asked them direct questions about their books. What did the workers ask for? Describe the relationship of a specialist with workers and red directors, a promoter with workers. Raise questions about the NEP. Do not forget gray everyday life:

“Write about family life, about our working life… at the factory on payday… the wife is standing at one gate, the children at another, to catch their father…”

"Describe our marital relations in connection with the new marriage law .

.. our family relations are now so complex that they require mandatory reflection in literature ..."

Of course, not everyone could speak, and for this there were notes to the presidium:

“Comrade writers! You criticize old writers, but you will not find in them such obscenity as you read in your works. Thanks to your books, all the youth have been corrupted.”

“Comrades, you sometimes write such Chubarovism that it’s embarrassing to read in front of children (meaning the high-profile case of gang rape in Leningrad in 1926, the so-called “Chubarovsky case”. - Approx. Aut.)”.

“Young workers do not understand your books, your prose does not captivate or touch. You promised to release "Red Nutpinkertonism", but for some reason everyone is dragging it out, hoping that for lack of fish and cancer, fish.

Adrian Toporov and Mayskoye Morning commune

The euphoria from the new tool of cognition began to subside along with the collapse of the New Economic Policy. Questionnaires often did not justify themselves, were poorly compiled, librarians did not have time to work at the request of researchers and did not see practical benefits in this work. As a result, the result did not satisfy either research or ideological requests. At the same time, the political course changed, and the populist, cultural classless approach began to be called apolitical, opportunistic and Menshevik. The former ladies and gentlemen who went to the people with first-aid kits and libraries, that is, those who laid the foundation for the research of readers in Russia, fell into disgrace.

Questionnaires often did not justify themselves, were poorly compiled, librarians did not have time to work at the request of researchers and did not see practical benefits in this work. As a result, the result did not satisfy either research or ideological requests. At the same time, the political course changed, and the populist, cultural classless approach began to be called apolitical, opportunistic and Menshevik. The former ladies and gentlemen who went to the people with first-aid kits and libraries, that is, those who laid the foundation for the research of readers in Russia, fell into disgrace.

The point was that the reader, according to the new ideological justifications, was to become no longer an object of study, but an object of goal-setting. And one should have relied not on a real reader who had the audacity to read The Love of Jeanne Ney by Ilya Ehrenburg or speak well of the story All Quiet on the Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque, but on a constructed reader who, in a proletarian way, correctly and classily assessed even that and other.

The reader was not supposed to be a mystery to the proletarian writer, such an approach was branded as demagogic and opportunistic. And now it was necessary to study the reader's demand only and exclusively in order to reveal harmful and even wrecking tendencies, save bourgeois writers from Yeseninism, counter-revolutionaryism, burn out and uproot these individual readers in individual libraries.

It was at this time that the teacher and educator Adrian Mitrofanovich Toporov published his book Peasants about Writers. A brief history of this book is as follows. In 1920, the commune "May morning" was created in Altai by poor peasants. Toporov worked as a teacher there, but even before that, since 1915, he had been reading among the peasants. From the point of view of the methodology of work, Toporov inherited the approach of An-sky and Alchevskaya - he read the books aloud to the peasants and then recorded the discussion.

After the Civil War, about 20 peasant families from the village of Verkh-Zhilino, Altai province, created the May Morning commune, where the writer and educator Adrian Toporov taught. In the photo - Priest Selyshev with students from the village of Verkh-Zhilino / Toporov family archive

In the photo - Priest Selyshev with students from the village of Verkh-Zhilino / Toporov family archive Toporov's choice of reading sometimes raised questions: in particular, a fragment of Boris Pasternak's poem "Spektorsky" got into peasant readings, which caused the most unflattering reviews of the peasants: "Kalina-raspberry, chicken shit ...", "Pasternak robbed the treasury with this verse." Apparently, Toporov, being subscribed to the literary magazine Krasnaya Nov, simply read to the peasants all the lyrics that appeared there (such a conclusion can be drawn from a selection of poems in the first edition of his book).

It cannot be said that the opinions of the peasants recorded by Toporov were noticeably different from those presented by other studies of popular reading. The first publications of Toporov's notes in the Siberian Lights magazine with a discussion of the texts of the writers Alexander Neverov and Lydia Seifullina were received very well. But Toporov turned out to be a very convenient figure for an ideological attack - he was just a "culturalist" of the old formation (he began working with the peasants even before the revolution), declared impartiality and classlessness.

"The 'classless', 'non-party', apolitical approach to the study of the reader objectively leads in the final analysis to distract the masses from the struggle for socialism, lulls their vigilance, weakens the leading role of the proletarian vanguard..."

In addition, Toporov's recipients were almost illiterate peasants, almost two-thirds were literate and could only sign a name or count money - the author himself writes about this, giving the peasants characteristics. He opened the layer that had not yet been worked on, and the one that was now politically dangerous to work with. As a result, "axeism" was branded in the press and at the same time anathematized the entire sociology of such work. Toporov's book was included by Glavlit in the "Annotated Lists of Politically Harmful Books to Be Removed from Libraries and Booksellers".

The ideological problem of the Soviet government was that the reader turned out to be real. And the emerging aesthetics of socialist realism needed to form the image of an ideal reader, so that the real reader could be brought up to the required level (Yevgeny Dobrenko wrote well about this feature of socialist realism - the aesthetics that shape politics - in his work “Late Stalinism”).