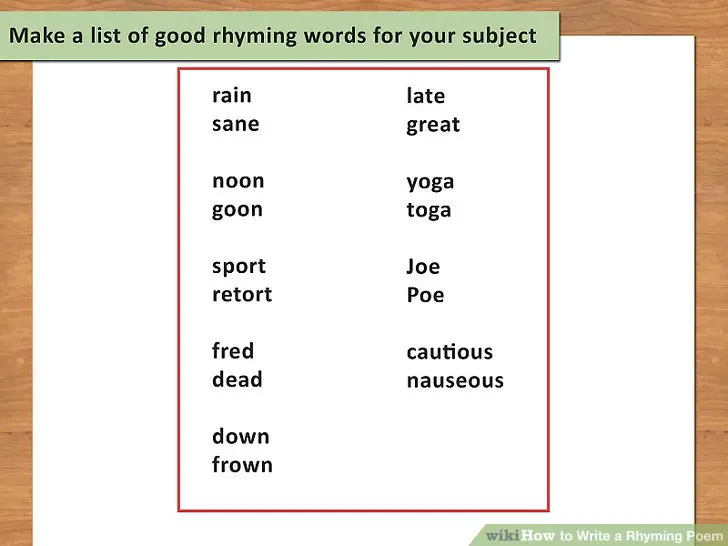

Example of rhyming word

Rhyming Words | List of 70+ Interesting Words that Rhyme in English

by Issabella

Words that Rhyme in English! List of rhyming words. Learn 70 useful words that rhyme in English with example sentences and ESL printable infographics.

Table of Contents

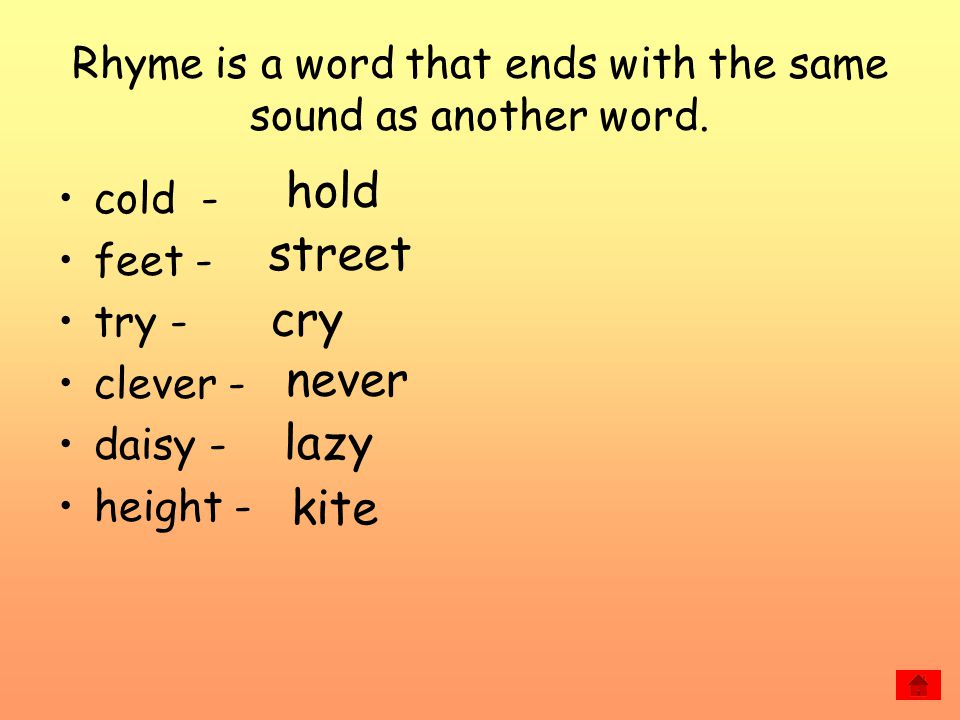

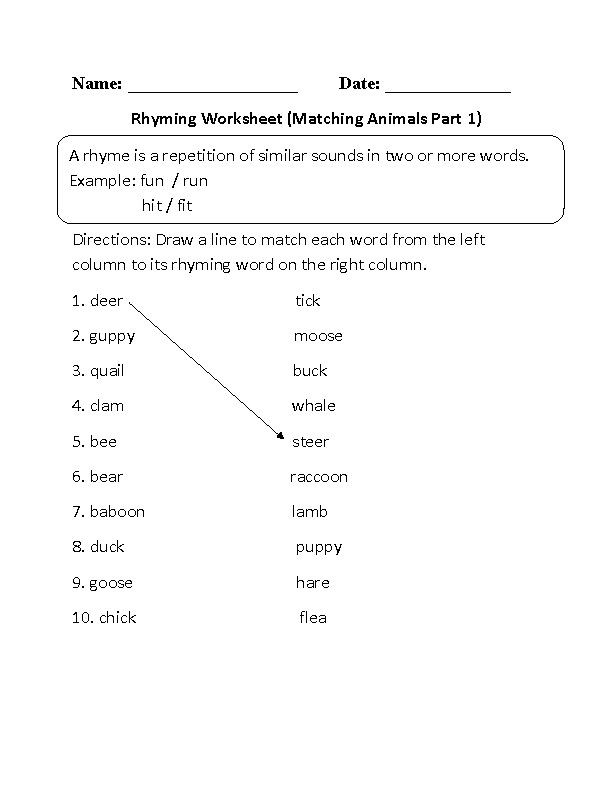

What are Rhyming Words?

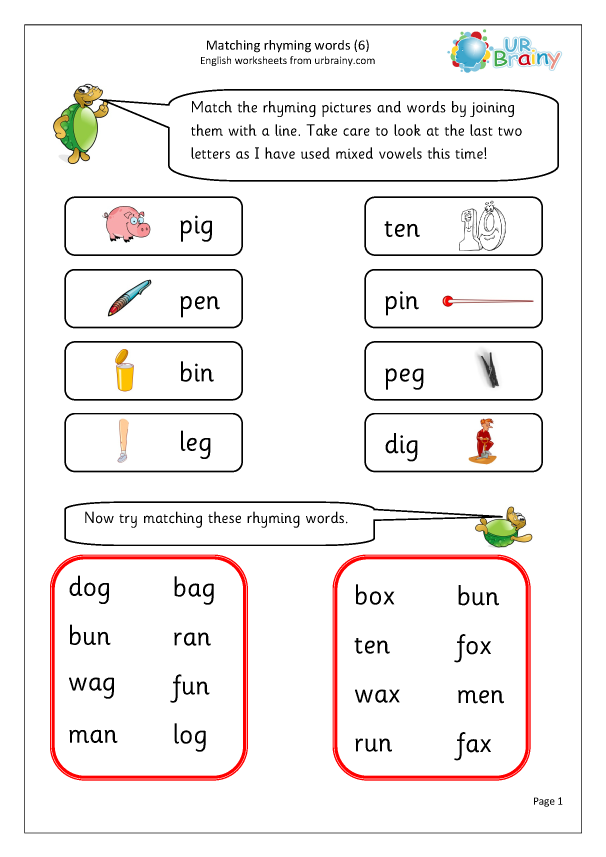

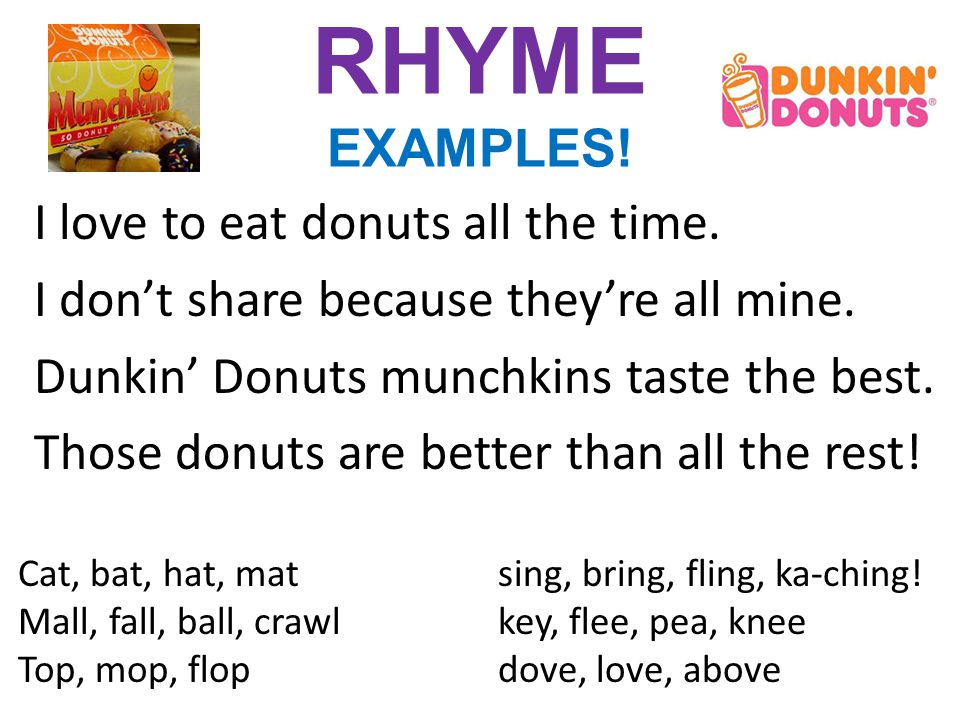

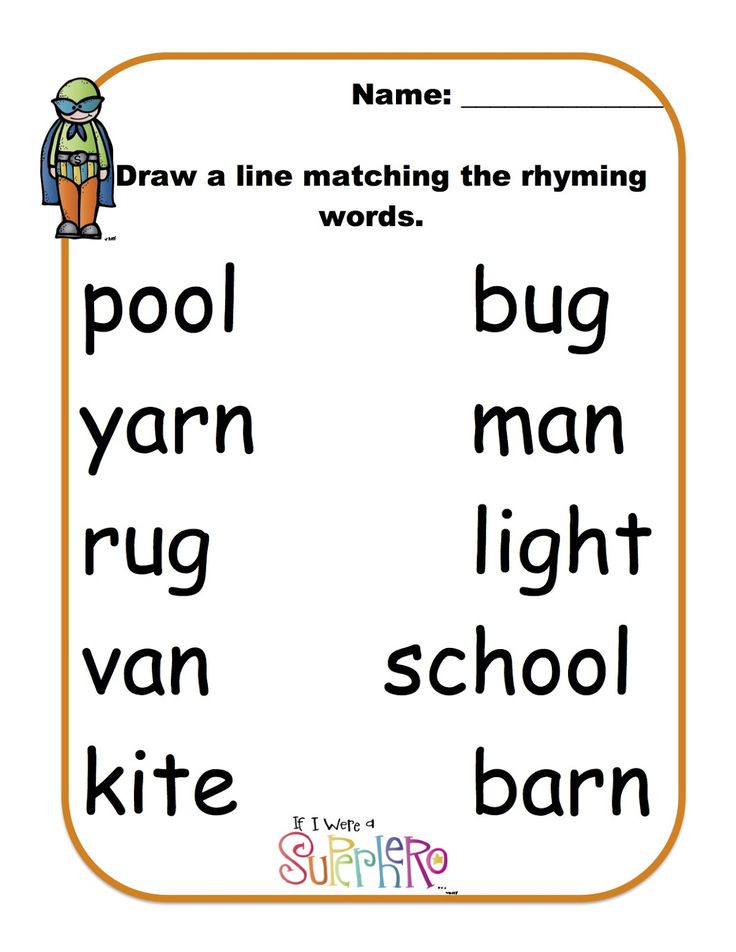

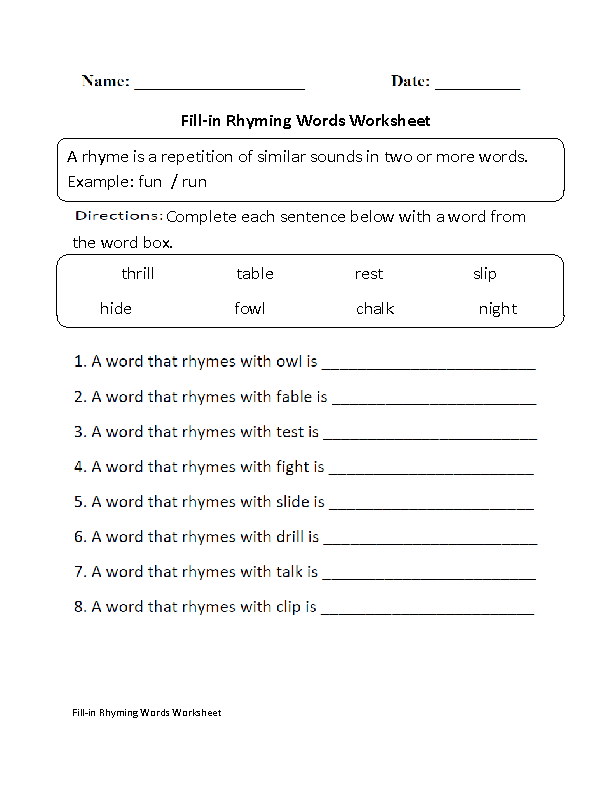

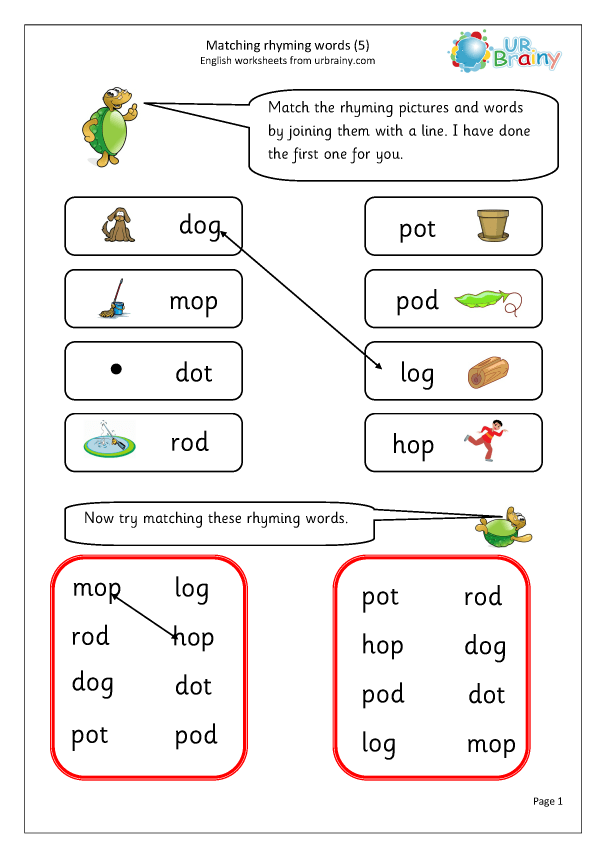

A rhyme is a repetition of similar sounds (usually, exactly the same sound) in the final stressed syllables and any following syllables of two or more words. In other words, rhyming words are two or more words that don’t start with the same sound, but they end with the same sound (maybe with the same letters). Some examples of rhyming words are: cat, fat, bad, ad, add, sad, etc.

Poems and songs often use rhyming to create a rhythm or a repeated pattern of sound, and sometimes poems will also tell a story. By learning these words, students will increase their sentence building and creative writing skills.

Things to remember about the difference between rhyming words and homophones:

Rhyming words have different beginning sounds, but have the same vowel and ending sounds, for example: cat/sat/pat/hat, spin/fin/chin/pin, etc. Homophones are words that sound alike but have different meanings and spellings, for example: pain/pane, hi/high/, you/yew/ewe, there/their/they’re, to/too/two.

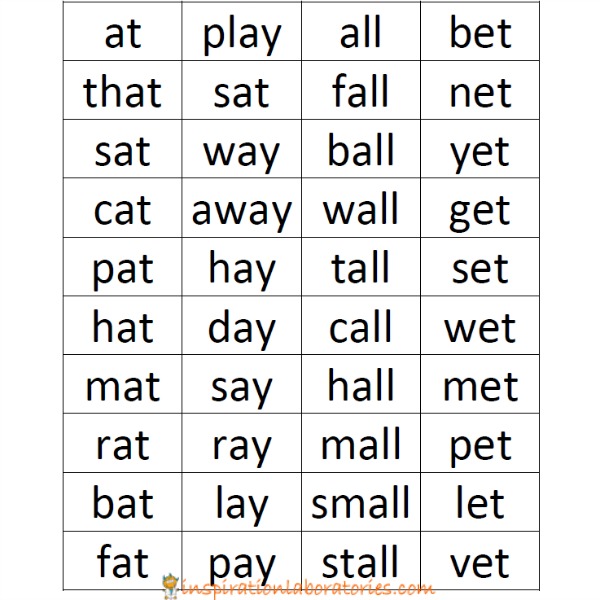

Words that Rhyme in English

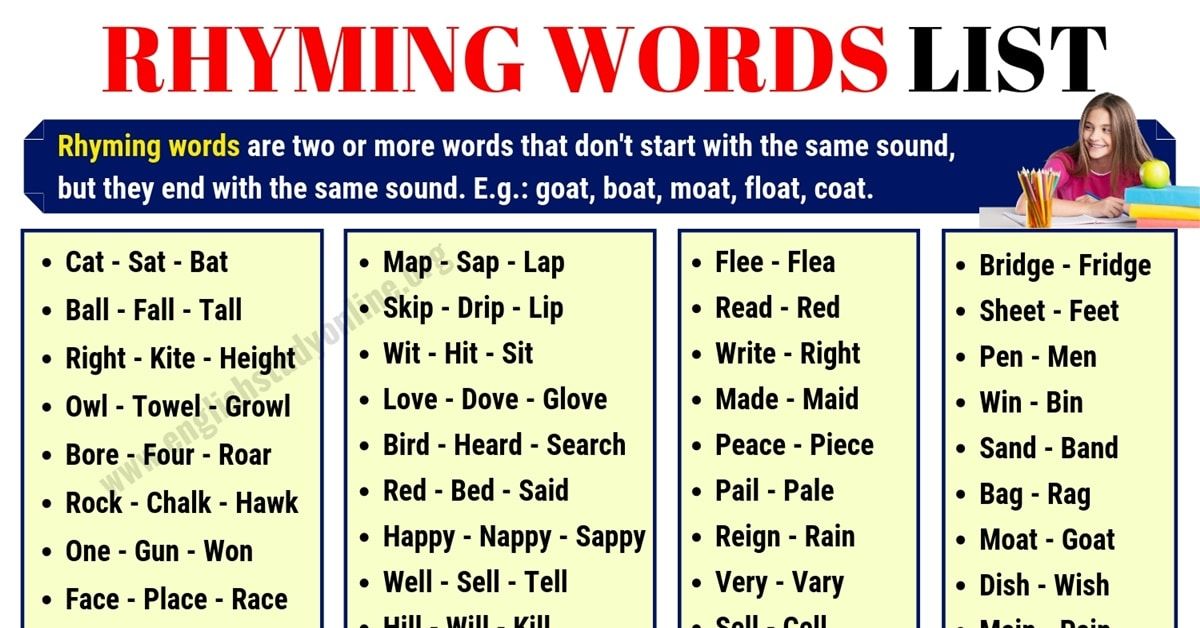

Rhyming Words List

Here is the list of 70+ words that rhyme in English.

- Cat – Sat – Bat

- Ball – Fall – Tall

- Right – Kite – Height

- Owl – Towel – Growl

- Bore – Four – Roar

- Rock – Chalk – Hawk

- One – Gun – Won

- Face – Place – Race

- Boat – Coat – Float

- All – Ball – Call

- Cave – Gave – Save

- Jump – Bump – Lump

- Day – Stay – Hay

- Hole – Mole – Stole

- Hot – Not – Cot

- Cook – Look – Hook

- Seed – Feed – Weed

- Map – Sap – Lap

- Skip – Drip – Lip

- Wit – Hit – Sit

- Love – Dove – Glove

- Bird – Heard

- Red – Bed – Said

- Happy – Nappy – Sappy

- Well – Sell – Tell

- Hill – Will – Kill

- Hide – Tide – Wide

- Sing – Wing – King

- Cow – How – Now

- Kick – Pick – Lick

- Ad – Add

- Blew – Blue

- Bear – Bare

- Days – Daze

- Flee – Flea

- Read – Red

- Write – Right

- Made – Maid

- Peace – Piece

- Pail – Pale

- Reign – Rain

- Very – Vary

- Wool – Fool

- Rig – Dig

- Pet – Met

- Soon – Moon

- Hop – Pop

- Make – Cake

- Hero – Zero

- Change – Range

- Caller – Taller

- Bridge – Fridge

- Sheet – Feet

- Pen – Men

- Win – Bin

- Sand – Band

- Bag – Rag

- Moat – Goat

- Dish – Wish

- Main – Pain

- Meet – Greet

- Seven – Heaven

- Nine – Wine

- Ten – Hen

- Four – Door

- Three – Tree

- Two – Shoe

- Six – Sticks

- Eight – Skate

Rhyme Words in English | Infographic

Categories VocabularyExamples of Rhyme and Its Many Types

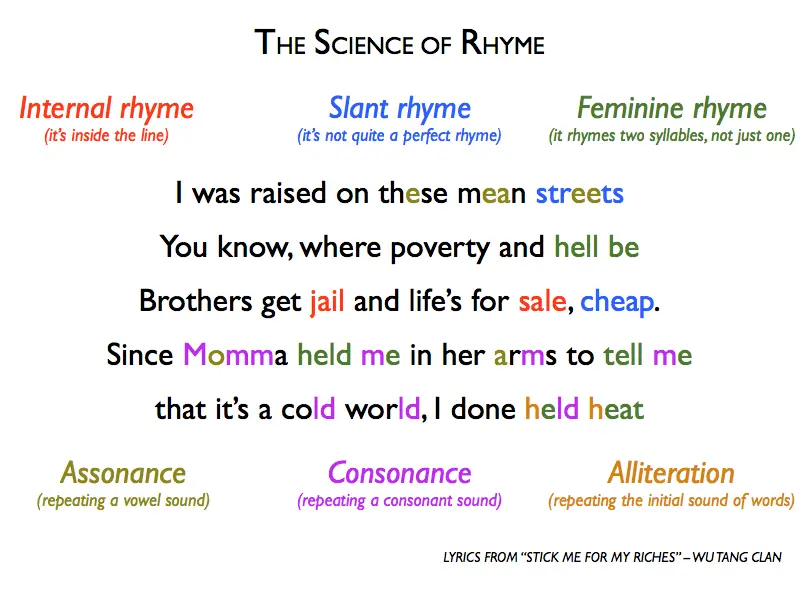

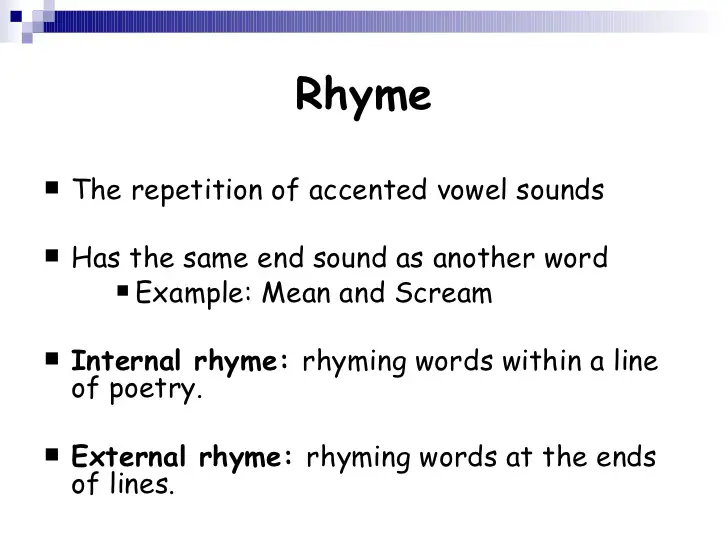

A rhyme occurs when two or more words have similar sounds. Typically, this happens at the end of the words, but this isn't always the case. Review several of the many types of rhymes along with rhyme examples for each type.

Typically, this happens at the end of the words, but this isn't always the case. Review several of the many types of rhymes along with rhyme examples for each type.

rhyme example using dactyl meter

Advertisement

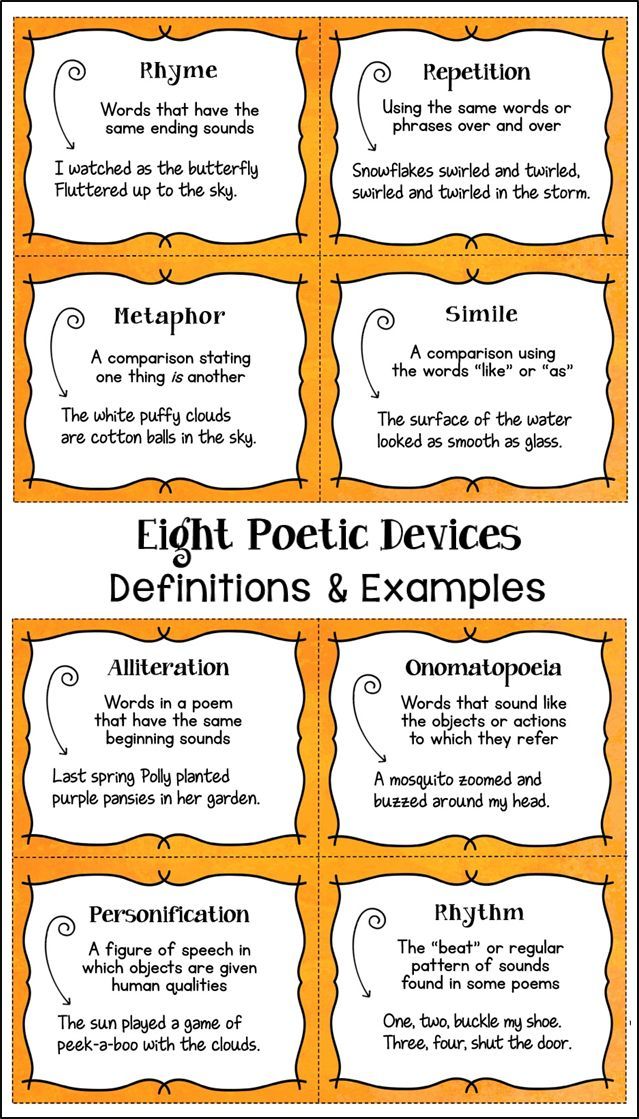

Different Types of Rhymes

Poetry is a beautiful form of expression. Just as there are numerous kinds of poetry, there are also many types of rhymes.

Assonance in Rhyme

Assonance involves using repeated vowel sounds in words that are close to each other. It is sometimes referred to as a slant rhyme. There are many examples of assonance in poetry. This technique is also common in literature and prose. The following word combinations illustrate assonance.

- tip, slip and limp

- that, spat and bat

- bow, no and home

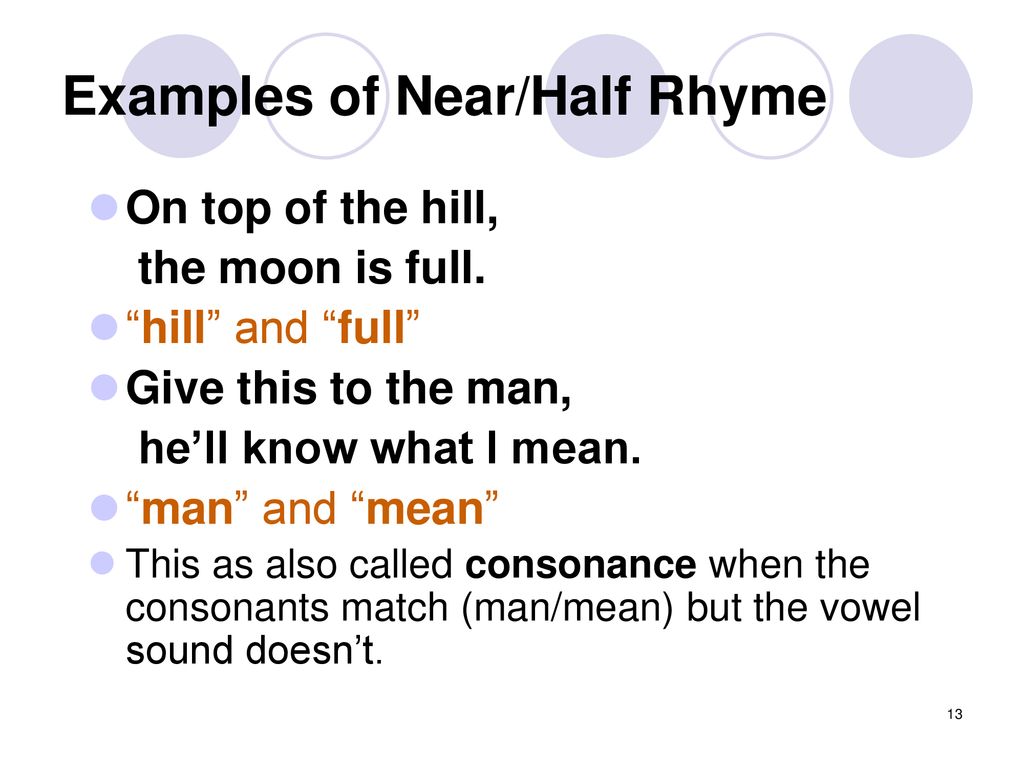

Consonance in Rhyme

Consonance involves repeating consonant sounds in words that are close together. There are many examples of consonance, including:

There are many examples of consonance, including:

- dump, dame and damp

- meter, miter and metric

- mile, mole and meal

Dactyl Meter

Dactyl meter is a rhyming pattern in which the first syllable is stressed and followed by two unstressed syllables. Words of at least three syllables can be dactylic on their own. Lines of poetry with shorter words can be dactylic as well. What matters is that the pattern of stressed syllable, unstressed syllable, unstressed syllable is followed.

- cacophonies (single word)

- hickory, dickory, dock (line of a poem)

Eye Rhyme

Eye rhyme is based on spelling and not sound. It refers to words with similar spellings that look as if they would rhyme when spoken, yet are not pronounced in a way that actually rhymes. Example of eye rhyme word pairs include:

It refers to words with similar spellings that look as if they would rhyme when spoken, yet are not pronounced in a way that actually rhymes. Example of eye rhyme word pairs include:

- move and love

- cough and bough

- food and good

- death and wreath

Feminine Rhyme

Feminine rhyme occurs when a word has two or more syllables that rhyme with each other. This type of rhyme is also referred to as double, triple, multiple, extra-syllable, or extended rhyme. Examples of feminine rhyme word pairs include:

- backing and hacking

- tricky and picky

- moaning and groaning

- generate and venerate.

Head Rhyme

Also called alliteration or initial rhyme, head rhyme has the same initial consonant at the beginning of the words. There are many examples of alliteration in poems. Head rhyme is also common in literature. Word pairs that illustrate head rhyme include:

- blue and blow

- sun and sand

- merry and monkey

Advertisement

Identical Rhyme

Identical rhyme is rhyming a word with itself by using the exact same word in the rhyming position. In some cases, the repeated word refers to a different meaning. For example:

- day by day, until the break of day

- I'll find my way, come what may / There must be a better way / No barriers do I see in the way

Another example is the way the word ground is used in Emily Dickinson's "Because I Could not Stop for Death. "

"

"We paused before a House that seemed

A Swelling of the Ground —

The Roof was scarcely visible —

The Cornice — in the Ground."

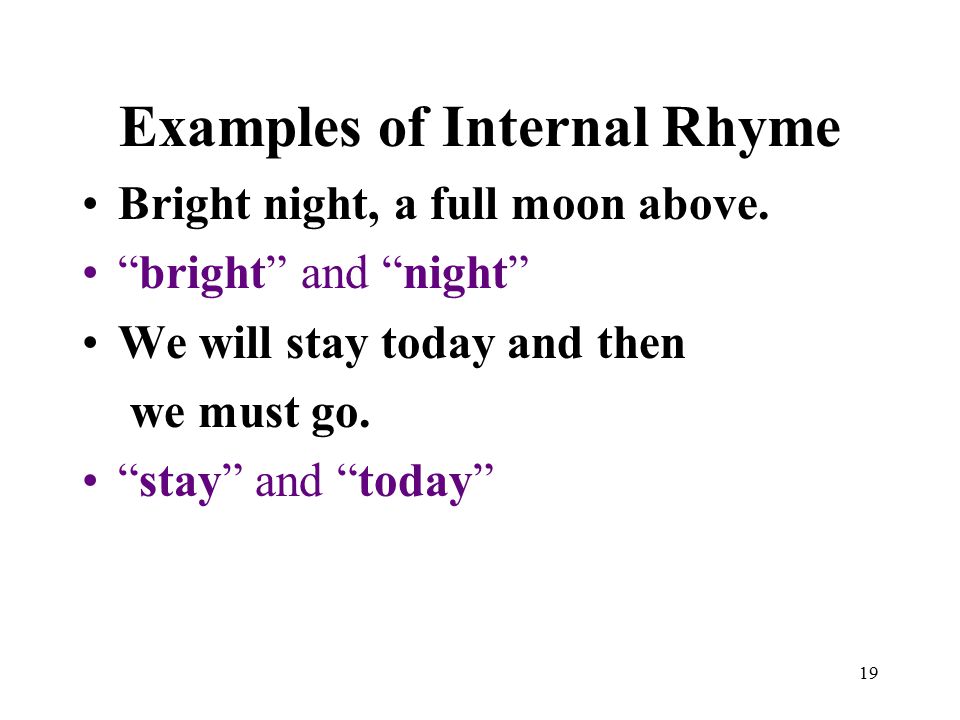

Internal Rhyme

With internal rhyme, rhyming occurs within lines of poetry. Sometimes the rhyming happens within a single line of poetry, but not always.

- Every day I say I wonder, if I may

- What could have been if only I were let in

- A new outcome perhaps, at least for some

- "Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary" (from "The Raven," by Edgar Allen Poe)

Light Rhyme

With light rhyme, one syllable is stressed and another is not. Examples include:

- frog and dialog

- mat and combat

Macaronic Rhyme

Macaronic rhyme is a technique that rhymes words from different languages. Below, English words are on the left and words from other languages that rhyme with them are on the right.

Below, English words are on the left and words from other languages that rhyme with them are on the right.

- favor and amor

- sure and kreatur

- lay and lei

- guitar and sitar

Masculine Rhyme

With masculine rhyme, the rhyme is based on a single stressed syllable in both words. Examples that illustrate masculine rhyme include:

- support and report

- dime and sublime

- divulge and bulge

Advertisement

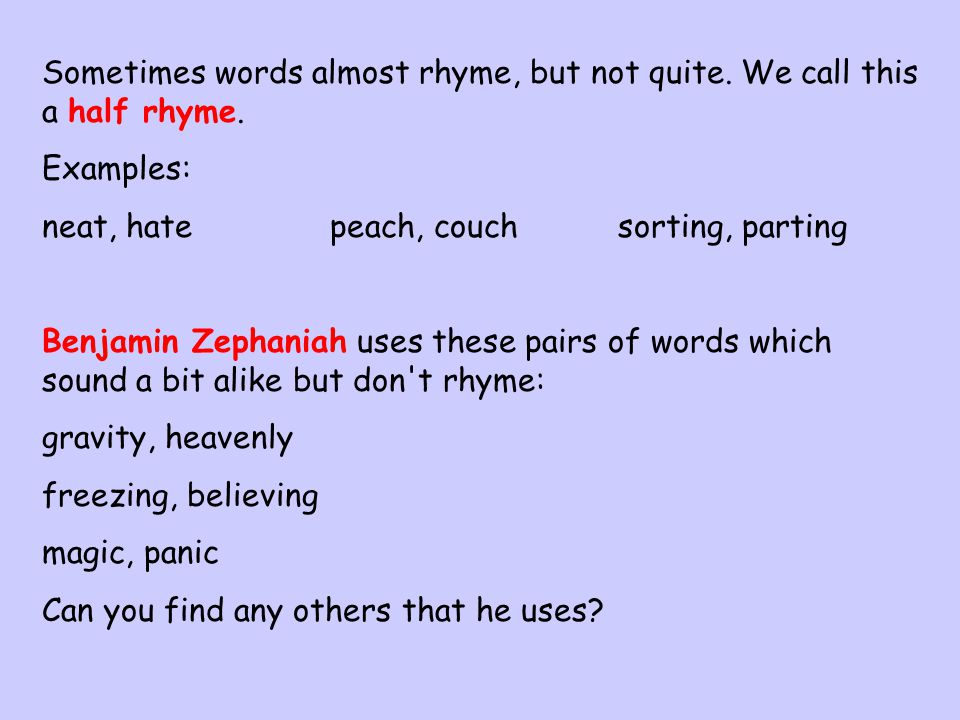

Near Rhyme

Near rhyme goes by several different names. This type of rhyme is also referred to as half, approximate, off, oblique, semi, or slant rhyme. It rhymes the final consonants of words, but not the vowels or initial consonants. Because the sounds do not exactly match, this type of rhyme is considered an imperfect rhyme. Examples include:

Examples include:

- blueprint and abhorrent

- quick and back

- fun and mean

- climb and thumb

Perfect Rhyme

Sometimes called exact, full or true, a perfect rhyme is the typical rhyme where the ending sounds match exactly. Examples include:

- cat and hat

- egg and beg

- ink and pink

- boo and true

- soap and hope

Rich Rhyme

Rich rhymes involve words that are pronounced the same but are not spelled alike and have different meanings. In other words, rich rhymes feature terms that are homonyms. Examples include:

- raise and raze

- break and brake

- vary and very

- lessen and lesson

Scarce Rhyme

Scarce rhyme is a type of imperfect rhyme used for words that have very few other words that rhyme with them. For example, not a lot of words sound like different.

For example, not a lot of words sound like different.

- wisp rhymed with lips

- motionless with oceanless

Syllabic Rhyme

Syllabic rhyme involves rhyming the last syllable of words. It is also called tail rhyme or end rhyme.

- sliver and cleaver

- litter and latter

Wrenched Rhyme

Wrenched rhyme is an imperfect rhyme pattern. It rhymes a stressed with an unstressed syllable.

- caring and wing

- lady and a bee

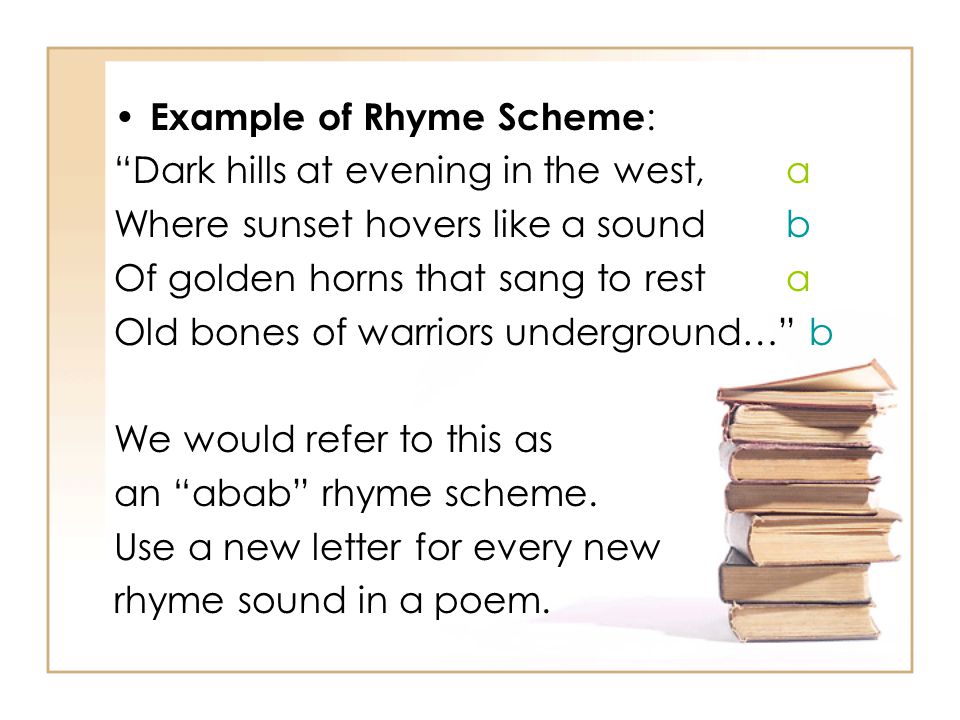

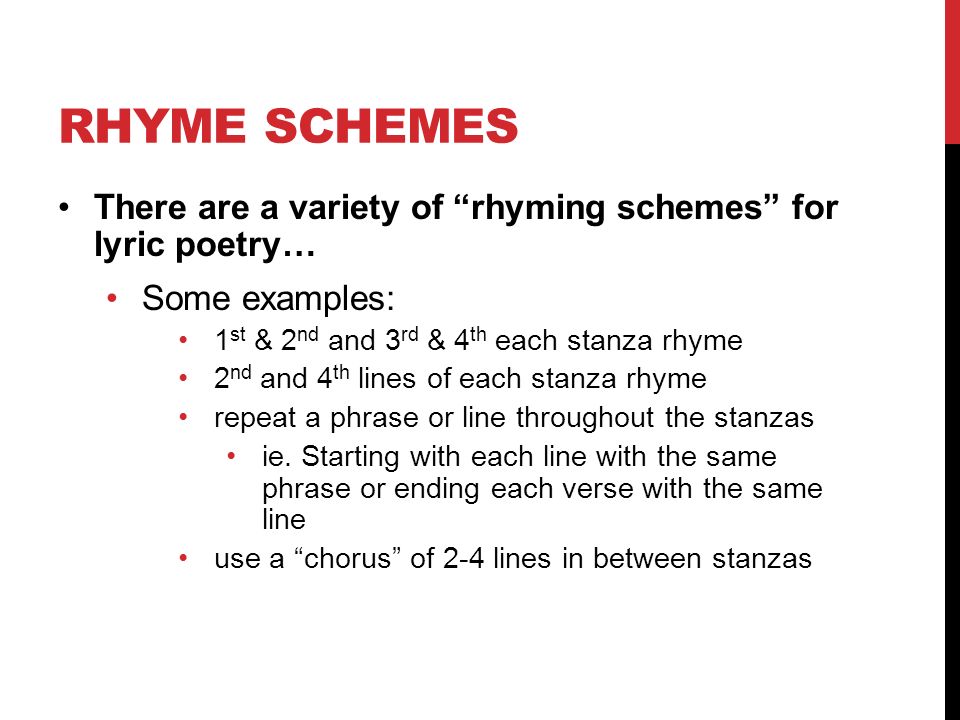

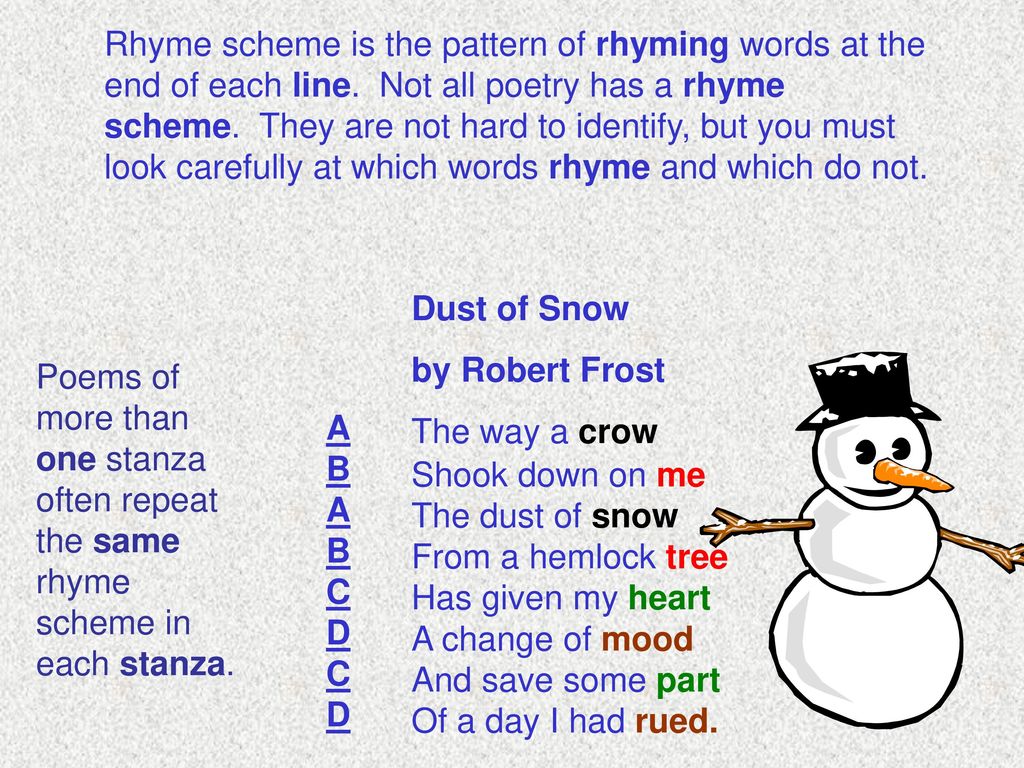

Using Rhyme Schemes in Verse

The different types of rhymes can be used in all types of poems and prose. Many include more than one type. Be on the lookout for different rhyme scheme examples in poems.

- Alternating rhyme features an ABAB pattern. It is also referred to as crossed rhyme or interlocking rhyme.

- Intermittent rhyme is a pattern in which every other line rhymes.

- Envelope rhyme or inserted rhyme has an ABBA rhyming pattern.

- Irregular rhyme does not have a fixed pattern to the rhyming. This is common in free verse poetry.

- Sporadic rhyme or occasional rhyme has an unpredictable pattern with mostly unrhymed lines.

- Thorn rhyme features a line that does not rhyme in a passage that would be expected to rhyme based on the pattern of the poem.

Advertisement

Staff Writer

modern history and position in society / Habr

Cockney is one of the most famous slangs of the English language, which in the 19th and even in the 20th century was very popular among certain segments of the population of Britain and, in particular, London. But what is happening to him today? Why do some linguists say cockney is dying? Let's figure it out.

What is cockney: a bit of history

Cockney is a variant of the English language that has been used since the Middle Ages.

The term itself is quite old - it first appears in literature as early as 1362 in William Langland's Plowman.

The term "cockney" is translated as "rooster's egg" ("cock" - English "rooster", "ey" - cf. English "egg"). In the Middle Ages, deformed and underdeveloped chicken eggs were called so - it was believed that such eggs were laid by a rooster.

Later, this word began to refer to people who were born and raised in cities. Rural residents believed that city dwellers were weaker because they worked less.

In the 17th century, the meaning of the word approached the modern one - this is how the inhabitants of London, who lived in the City area, began to be called. John Mishu in his book "Ductor in linguas" (1617) wrote: "Cockney applied only to those who were born to the sound of the Bow-bell, that is, in the City of London." But even then the designation was offensive.

By the 18th century, two completely different models of language were spreading in London. In the West End, the so-called "polite pronunciation" - gentlemanly English - prevailed. And in the East End, Cockney. So they began to call not only people, but also the slang they spoke.

In the West End, the so-called "polite pronunciation" - gentlemanly English - prevailed. And in the East End, Cockney. So they began to call not only people, but also the slang they spoke.

Cockney phonetics

The pronunciation and sound of Cockney is quite different from literary or "standard" English. This slang is characterized by the deliberate distortion of sounds and the replacement of individual words with rhyming counterparts - in fact, it was because of this that Cockney began to be called rhyming slang.

Let's look at typical speech features:

- Omitting [h] - for example, "'alf" instead of "half" or "'Ampton" instead of "Hampton".

- Using ain't instead of "am not" or "isn't".

- Pronunciation of sound [θ] as [f]. For example, "frust" instead of "thurst" or "faasn'd" instead of "thousand".

- Pronunciation of sound [ð] as [v]. For example, "bover" instead of "bother".

- Pronunciation of the diphthong [aʊ] as [æ:].

For example, "down" is pronounced "dæ:n".

For example, "down" is pronounced "dæ:n". - Omitting double [t] using a glottal stop. For example, "cattle" is pronounced [kæ'l].

- Use of an unaccented [l] as a vowel. For example, Millwall is pronounced "miowɔː".

One of the most interesting features is the use of rhyming slang. When words in a sentence are replaced by words or phrases that rhyme with the replaced ones.

Here are some examples of cockney words:Believe - Adam and Eve.

Do you Adam and Eve him? - Do you believe him?Appendix - Jimi Hendrix.

I just 'ad my Jimi Hendrix taken out! “I just had my appendix removed.Tea - You and Me.

Do you want a cup of You and Me? — Would you like a cup of tea?Sense - Eighteen pence.

He hasn't got eighteen pense! - He has no brains!

In some cases, the second, rhyming part of the phrase is omitted altogether, which made it extremely problematic to understand the true meaning.

Try to guess what the following phrases mean:

- Hello, my old China.

- Take a Butcher's at this!

- Lend me a few pounds please, I'm complete Boratic.

- Get your Plates off the table!

If you couldn't guess, here's the transcript.

Hello, my old China.

China = China and plate = mate.

Hello my old friend.

Take a Butcher's at this!

Butcher's = Butcher's hook = look.

Look at it!

Lend me a few pounds please, I'm complete Boratic.

Boratic = Boratic lint = skint.

Lend me a couple of pounds, please, I don't have any money at all.

Get your Plates off the table!

Plates = Plates of meat = feet.

Get your feet off the table!

Often this abbreviation is used only for well-known lexemes that are often used in conversations. Otherwise, there is a possibility that the interlocutor simply does not understand the reference and he will have to explain it in ordinary human language. (What a horror!)

(What a horror!)

Contemporary Cockney

It was because of the rhyming of words in the 19th century that Cockney was often associated with the code language of criminals. And that's when Cockney went from a narrowly localized slang to a language spoken throughout South East England.

At the beginning of the 20th century, cockney went beyond London and began to spread to the nearest locations. This type of slang was especially popular in such counties as Essex and Bedfordshire. Basically, cockney speakers were people of a working specialty, without any special education.

Television spreads cockney throughout England. However, the concentration of carriers in the southeast is still the highest.

First of all, Cockney's popularity is due to such TV shows as "Steptoe and Son" (1962-1974), "Minder" (1979-1994), "Porridge" (1974-1977), "Only Fools and Horses" (1983-2003).

Watch an episode of the sitcom Steptoe and Son as an example. It will be extremely difficult for a person who studies English as a foreign language to perceive such a language by ear, even with a high level of knowledge. And be warned, the humor is very, very

It will be extremely difficult for a person who studies English as a foreign language to perceive such a language by ear, even with a high level of knowledge. And be warned, the humor is very, very blunt specific:

Beginning in the 1980s, the number of people who speak Cockney in Britain began to increase. It was mainly used by young people who wanted to stand out in society and emphasize their individuality through the use of idiomatic expressions.

There were even attempts to somehow fix slang at the legislative level, but they all failed.

In our time, the development of cockney has slowed down, and the number of people who speak it has decreased. Apparently, young people who began to speak it under the influence of TV programs eventually switched to standard English.

Nevertheless, native speakers distinguish as many as 3 types of Cockney:

- Classic Cockney. He appeals more to grammar and pronunciation of words.

In fact, this is the heir to the original cockney, which was spoken in the East End 300 years ago. Naturally, it has changed under the influence of Standard English, but the main phonetic features remain.

In fact, this is the heir to the original cockney, which was spoken in the East End 300 years ago. Naturally, it has changed under the influence of Standard English, but the main phonetic features remain. - Contemporary cockney. This is the version of the language that was popularized by TV programs. It has slightly fewer phonetic differences from standard English, but a lot more rhyming word substitutions. More on these borrowings below.

- Mockney. The so-called fake cockney. Artificial accent, phonetically similar to cockney. It is used by speakers of standard English as a language game or parody of classic cockney.

Modern cockney linguistically develops quite poorly - the vast majority of rhyming substitutions (96%) were created before the 19th century.

Today, new cockney phrases are predominantly created using the names of famous people.

- Al Capone - telephone;

- Conan Doyle - boil;

- Britney Spears-beers;

- Brad Pitt-fit;

- Barack Obama - pajamas;

- Jackie Chan—plan.

Hey, haven't you seen my working Jackie Chan?

Hey, have you seen my work plan?

Most of the lexical units that are currently used in cockney are not of a historical nature, but are used only as a language game. In fact, the main task of the speaker is to create verbal reflection that evokes associations by forming rhythm and rhyme with the replaced word.

If you look at the historical aspect, then from a specific code language, which was Cockney in the 17th-19th centuries, slang has turned into a kind of pun, where the individuality of native speakers is simply demonstrated with the help of puns. There are fewer and fewer real Cockney speakers, despite the fact that certain phonetic features of the dialect are still very common.

As an example of a classic cockney accent, let's look at an interview with Lionstone-born bassist Steve Harris of Iron Maiden:

You can clearly hear that the word "thing" Steve says through the sound [f] and not through [θ].And "down" he says like [dæ:n]. In addition, omissions of sounds [t] and [d] are noticeable in words with the endings -ing and the consonant t or d before it - for example, building and starting. In general, speech sounds quite comfortable and understandable, even for a person who studies English as a foreign language, but it should be borne in mind that Steve Harris uses only some of the phonemes that are inherent in Cockney and, of course, does not use rhyming substitutions at all.

The future of the Cockney dialect is rather vague. Linguistic researchers have several theories about what will happen to the Cockney dialect in the future.

David Crystal, Professor of Linguistics at Bangor University, argues that it is entirely possible for Cockney to disappear completely, but its significance indicates that the impulse that makes us rhyme words still has a fairly large impact. Perhaps that is why the classic cockney is being transformed from a dialect into a linguistic game.

At the same time, individual phonemes from the Cockney dialect are used extremely widely. The same Professor Crystal, in the course of his research, found that up to 93% of the inhabitants of Bradford from the working classes omit the sound [h] in a conversation - especially at the beginning of a word. That is, instead of "ham" they say "'am".

As for the future of Cockney, Paul Kerswill, Professor of Sociolinguistics at Lancaster University, is more categorical. He believes that Cockney will disappear from the streets of London within the next 30 years and be replaced by "multicultural London English, that is, a mixture of Cockney, Bangladeshi and Caribbean accents."

Despite the fact that some expressions from Cockney slang have taken root in the English language as phraseological units, and individual phonemes are used almost everywhere, there are fewer and fewer speakers of classic Cockney. So yes, it is quite possible that very soon (on a historical scale) it will be simply unrealistic to hear a real cockney from a native speaker.

EnglishDom.com is an online school that inspires you to learn English through innovation and human care

Only for readers of Habr - the first lesson with a teacher via Skype for free ! And when buying 10 lessons, enter the promo code goodhabr2 and get 2 more lessons as a gift. The bonus is valid until 05/31/19.

Get Premium access to ED Words and learn English vocabulary without limits. Get it right now at the link

Our products:

Learn English words in the ED Words mobile app

Download ED Words

Learn English from A to Z in the ED Courses mobile app

Download ED Courses

Install the Google Chrome extension, translate English words online and add them to study in the Ed Words app

Install the

Learn English in a playful way in online simulator

Online simulator

Improve your speaking skills and find friends in conversation clubs

Conversation clubs

Watch English life hacks video on EnglishDom 9 YouTube channel0048 Our YouTube channel

Rhyming translation and free verse translation Text of a scientific article in the specialty "Linguistics and Literary Studies"

Rhymed and vers libre translation Abstract:

The problems of rhyming and non-rhyming translation of Russian poetry into French are touched upon. It is noted that the loss of rhyme in the translation of the poetic original leads to dissonance between the original and the translation, the rhyme cements the verbal-artistic information into a single whole, performing a text-forming function. The analysis shows that non-rhyming translation reduces the emotional and aesthetic potential of rhymed poetic speech.

It is noted that the loss of rhyme in the translation of the poetic original leads to dissonance between the original and the translation, the rhyme cements the verbal-artistic information into a single whole, performing a text-forming function. The analysis shows that non-rhyming translation reduces the emotional and aesthetic potential of rhymed poetic speech.

Keywords:

Rhymed translation, non-rhymed translation, free verse, rhyming function, sound assonance, poetic meaning formation.

Makarova L.S.

Doctor of Philology, Professor of French Philology Department, the Adyghe State University, e-mail: [email protected]

A rhymed translation and a translation by using a free verse

Abstract:

The present research focuses upon rhymed and unrhymed translation of Russian poetry into the French language. The author demonstrates that loss of a rhyme in translation of the poetic original leads to a discord between the original and translation. The rhyme cements the verbal-art information in a single whole, implementing a text-forming function. The analysis shows that unrhymed translation reduces the emotional-aesthetic potential of rhymed poetic speech.

The rhyme cements the verbal-art information in a single whole, implementing a text-forming function. The analysis shows that unrhymed translation reduces the emotional-aesthetic potential of rhymed poetic speech.

Keywords:

Rhymed translation, unrhymed translation, free verse, rhyme-forming function, sound assonance, poetic sense formation.

The object of our research is the translation of Russian poetry into French. Recently, more and more unrhymed translations have appeared. To a certain extent, this is explained by the interest in free verse in modern poetry in general, which often refuses rhyme (especially easily predictable rhyme) and compensates for its absence due to the specific rhythmic organization of the verse and the complication of the conceptual component of poetic information.

In European poetic culture, the transition to non-rhyming poetry has been going on for a long time. First, there was a transition from exact rhyme to inexact. M.L. Gasparov points out that the cult of exact rhyme has been held in European literature since the Renaissance: “rhyme had to be accurate not only by ear, but also by eye” [1: 222]. With a stable set of poetic themes, this meant a rather stereotypical set of rhymes in stable pairs (such as: love - again in Russian or amours - toujours in French). Rhyme renewal was put forward as one of the fundamental requirements of French symbolism and post-symbolism, based on the rhyming of unexpected sound combinations (for example, riche - chere). It was the era of symbolism that was marked by the rejection of exact rhyme.

It is known that this attitude has not received sufficient practical support in French poetry, except for prescriptions related to

"spelling restrictions" for the eye. For example, the classics allowed only vide - humide, while the poets of the 20th century had vides - humide, chant - champ. The tradition of exact rhyme in French versification was very strong, and it was easier for poets to abandon rhyme altogether than to use inexact rhyme.

L.M.Gasparov writes: “In the rivalry between the renewed rhyme and the complete lack of rhyme, rhyme has found itself in a disadvantageous position: already by virtue of its

unaccustomed, it was felt as "difficult", "embarrassing", suitable only for the expressiveness of individual poems, but not for poetry as a whole. Meanwhile, behind the absence of rhyme stood the old traditions of high poetry, dating back to ancient and biblical verse. Both of these traditions - both antiquity and the Bible - had a strong influence on the formation of European free verse" [1: 224].

French free verse takes shape at the end of the 19th century and becomes widespread in the first half of the 20th century. During the years of the Resistance, he retreated before more traditional forms of verse, behind which national strength and tradition were felt, but after the end of the Second World War, there was a new surge of interest in free verse as a way of freer embodiment of poetic images, not constrained by the search for exact rhyme.

At the same time, non-rhyming translation is becoming more widespread, which, as is commonly believed, allows for a higher semantic similarity without being limited by rhyme. These two modes of poetic translation have coexisted for a long time. Much has been written about the preference for one or the other of them, but the problem has not found a final solution, which determined our interest in this aspect of poetic translation. It is quite obvious that the choice of translation method is mediated by the aesthetic creed of the poet-translator, his tastes and predilections, and it is interesting to trace what actually distinguishes non-rhyming and rhyming translations (besides the obvious absence or presence of rhyme).

As is known, rhyme as a conventional sound repetition at the end of a scale plays an important role in the process of poetic meaning formation. It is generally accepted that in the translation of poetry it is the search for rhyme that, in the first place, makes the original rebuild and change.

It seems to us that various assumptions are possible regarding what comes first in the translation choice - the desire to get away from the restraining "omnipotence" of rhyme and thus approach the poetic meaning, the fundamental focus on innovative poetic forms, the rejection of the principle of formally following the poetic original or something else.

It remains obvious that the non-rhyming translation of Russian poetry in France coexists alongside the rhymed one. In the last decade, a number of reprints and new editions of prose translations by A. Blok, V. Mayakovsky, A. Akhmatova and other Russian poets have appeared. Of course, this is a special kind of poetic translation, which needs to be analyzed from both linguistic and literary points of view.

Such an analysis could be the subject of a separate study. In this work, we will only touch upon the most general aspects of comparing these two methods of translation using the example of the first approximation to the analysis of rhymed and non-rhymed translations of the same poetic original.

Let's give the following example [2]:

...And there is my marble double,

Defeated under the old maple tree,

Face given to lake waters,

Heeds green rustles.

And light rains wash His dried wound...

Cold, white, wait,

I will also become marble.

(A. Akhmatova)

Je vois mon double...c’est un marbre Qui, foudroye, git sous les arbres,

Abandonnant ses pales traits Aux eaux du lac de la foret.

De claires pluies lavent sa plaie Qui s ’est deja coagulee...

Attends ! Attends! ...A l'avenir Je vais de marbre devenir.

(Translated by K.Granoff)

... Voici mon double. Il est en marbre.

Renverse sous le vieil erable,

La face vers les eaux du lac,

Il ecoute les bruits verdatres.

La lumiere des pluies lave Sa blessure ou le sang noircit...

Tu es froid, tu es blanc. Patience!

Moi aussi, je deviendrai marbre.

(Transl. - J.-L. Bakes)

- J.-L. Bakes)

Comparison of two translations, rhymed and non-rhymed, shows the presence of semantic transformations in both translations. In particular, in the first (rhymed) translation, the lexical unit "maple" is replaced on the basis of generalization by the lexical unit "arbres" (trees), which performs a rhyming function (marbre - arbre), the words traits - foret play the same role in the clause (adding foret - the forest supports and develops the theme of "green rustles", omitted in the translation - Listens to green rustles). The cross rhyme of the original is converted into a double rhyme in translation. In the second quatrain, the Cold, White segment, which is very significant for the emotional tone of the verse, is omitted (it is replaced by the repetition Wait! Wait!), As a result, the original color and tactile "impressionism" that is present in the original disappears.

The non-rhyming translation is, at first glance, closer to the original, but also less expressive. The loss of the emotional potential of poetic information occurs as a result of demetaphorization in the second and third lines of the first quatrain: instead of the brightly expressive “defeated” - the more prosaic “overturned” (Renverse), instead of the lake waters, the face is given - “Turning to face the lake waters” (La face vers les eaux du lac). On the other hand, the segment Cold, white (omitted in the first translation) is not only reproduced, but also strengthened by being separated into a separate structure, delimited by a dot (You are cold, you are white), which emphasizes the caesura in this line.

The loss of the emotional potential of poetic information occurs as a result of demetaphorization in the second and third lines of the first quatrain: instead of the brightly expressive “defeated” - the more prosaic “overturned” (Renverse), instead of the lake waters, the face is given - “Turning to face the lake waters” (La face vers les eaux du lac). On the other hand, the segment Cold, white (omitted in the first translation) is not only reproduced, but also strengthened by being separated into a separate structure, delimited by a dot (You are cold, you are white), which emphasizes the caesura in this line.

The first observation that can be made is that free verse translation does not lead to a decrease in the subjective component of the interpretation of poetic information in translation, i.e. precisely the component that marks the optional transformation of information. Optional transformations reflect, first of all, the perception of the poetic meaning by the translator, which, of course, is not free from subjective interpretation and can produce unjustified modifications of the verbal and artistic

information and - even - introduce new meaning formations into it that are absent in the original (see about this: [3]).

The undertaken analysis convinces us that the translation of poetry by vers libre, which is becoming more and more widespread in France, in a number of cases allows us to come closer to the transfer of the semantic texture of the verse. However, at the same time, he deprives the poetic work of its peculiar (almost musical) rhythm, melodiousness, formed by a special phonic combination of rhyme repetitions in the clause, and, ultimately, reduces the emotional intensity of verbal and artistic information.

The importance of rhyme is confirmed by the following observation. Despite the choice in favor of a non-rhyming translation, the rejection of rhyme, translators tend to use rhyme where possible, thereby reinforcing the rhythmic and sound structure of the verse. In a non-rhyming translation, sound assonances arise, similar to rhyme, cf. [4]:

Oh, how often you will remember Sudden melancholy of unnamed desires And in the pensive cities look for That street that is not on the plan!

At the sound of a voice behind the half-open door, You will think: “Here she came to the aid of my disbelief. ” 9couterai tes ordres, /Et j'attendrai, /Timide, au rendez-vous furtif -/Espererai.

” 9couterai tes ordres, /Et j'attendrai, /Timide, au rendez-vous furtif -/Espererai.

Rhyme structures the verse, gives it an aesthetic "aura" and actively participates in the formation of meaning. As a result of the prosaic reformulation of poetic information, a gap arises between the original and the translation. After all, rhyme, as a distinctive feature of poetic speech, “tropeizes” and cements verbal and artistic information into a single whole, performing a text-forming function. A rhymed translation seeks to reproduce all the features of the poetics of the original, not only words and images, but also its inherent rhythm and formal features, which makes it possible to convey all the richness of the associations inherent in the original.

Notes:

1. Gasparov M.L. Essay on the history of European verse. M.: Fortuna Limited, 2003. 271 p.

2. Akhmatova A. Poems of my white flock. M.: Eksmo-Press, 2000. 600 p.

3. Makarova L.S. Poetic discourse and translation // Bulletin of the Adyghe State University.