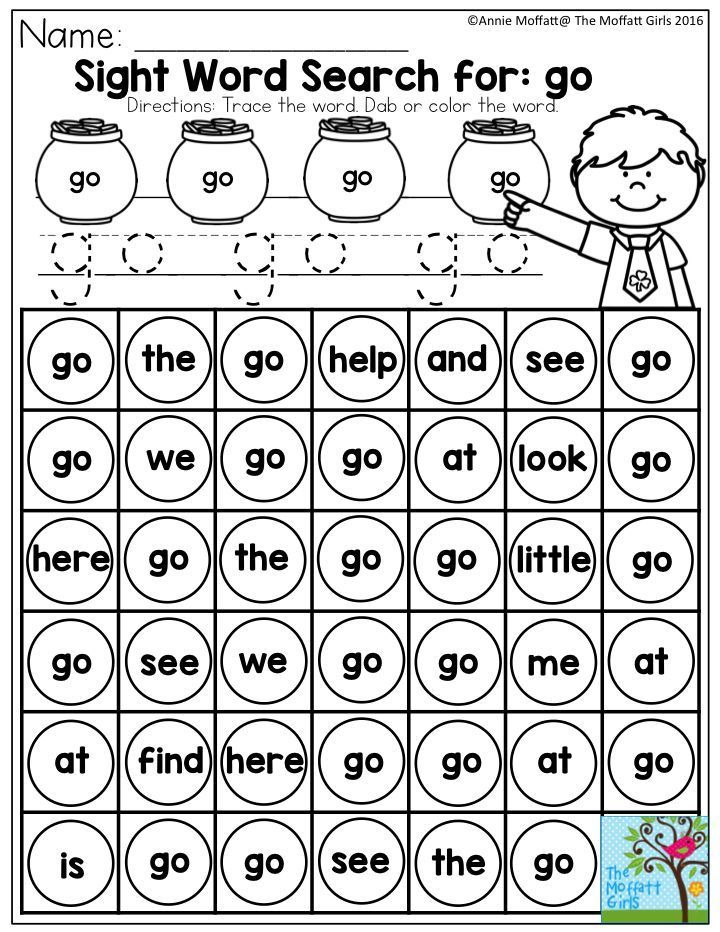

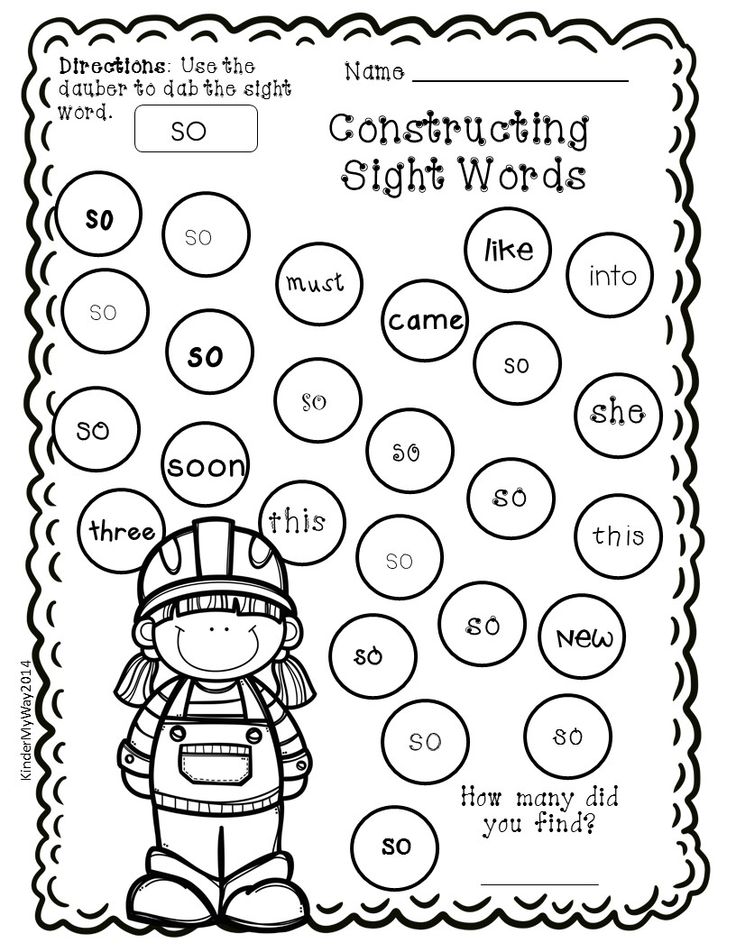

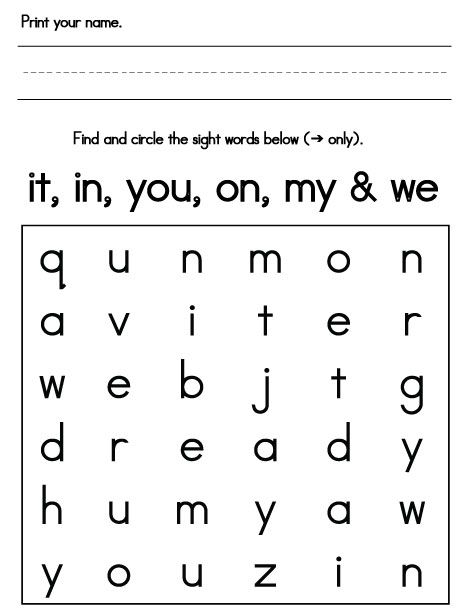

Find sight word

Sight Word Find Literacy Activity from Busy Toddler

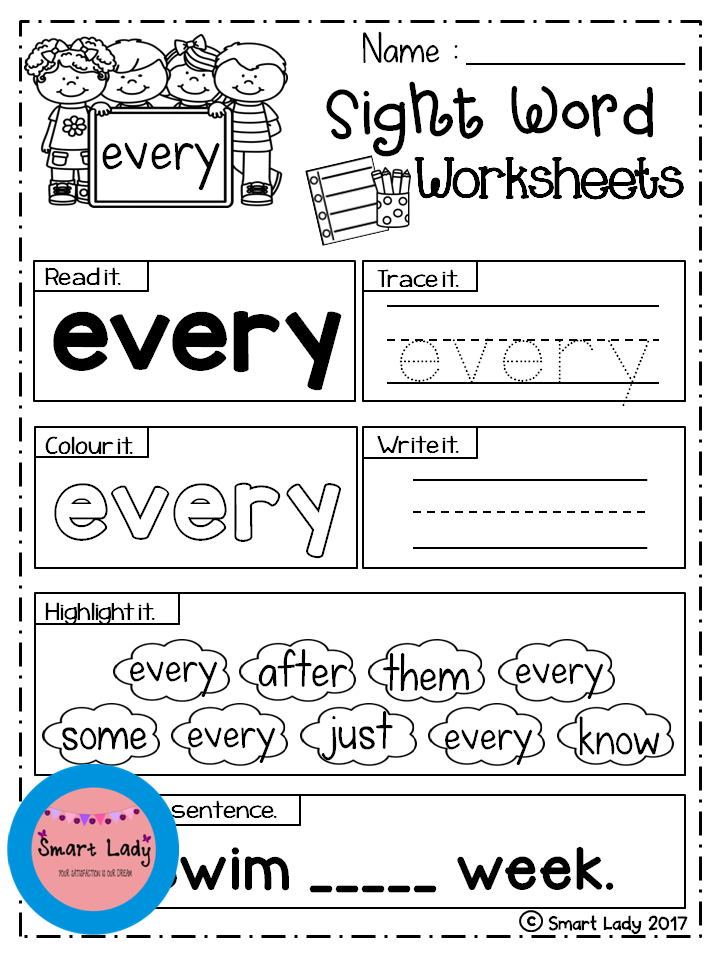

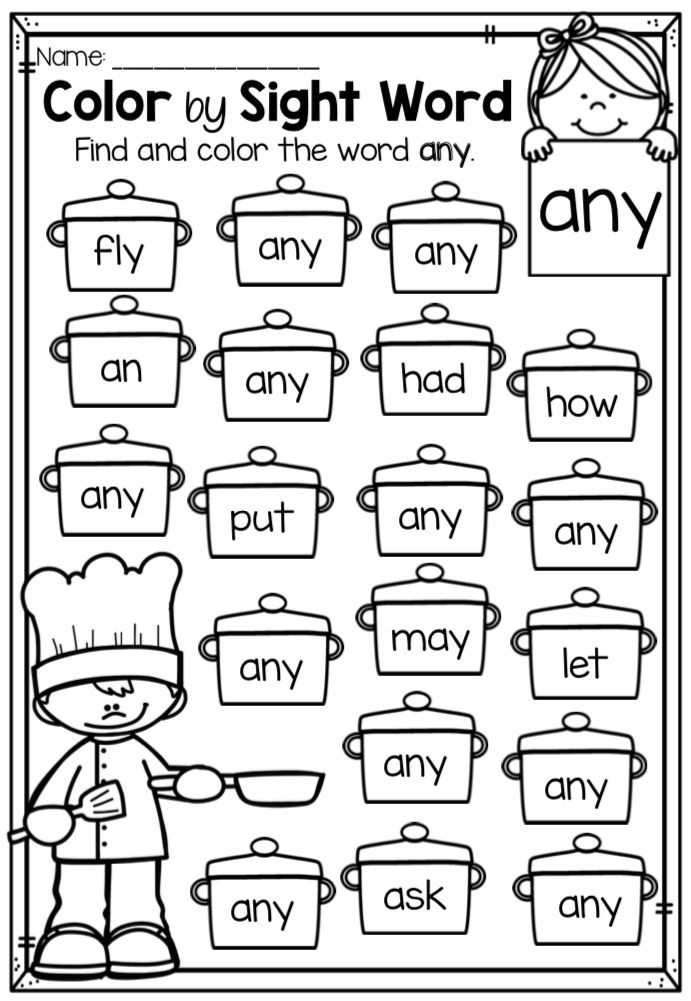

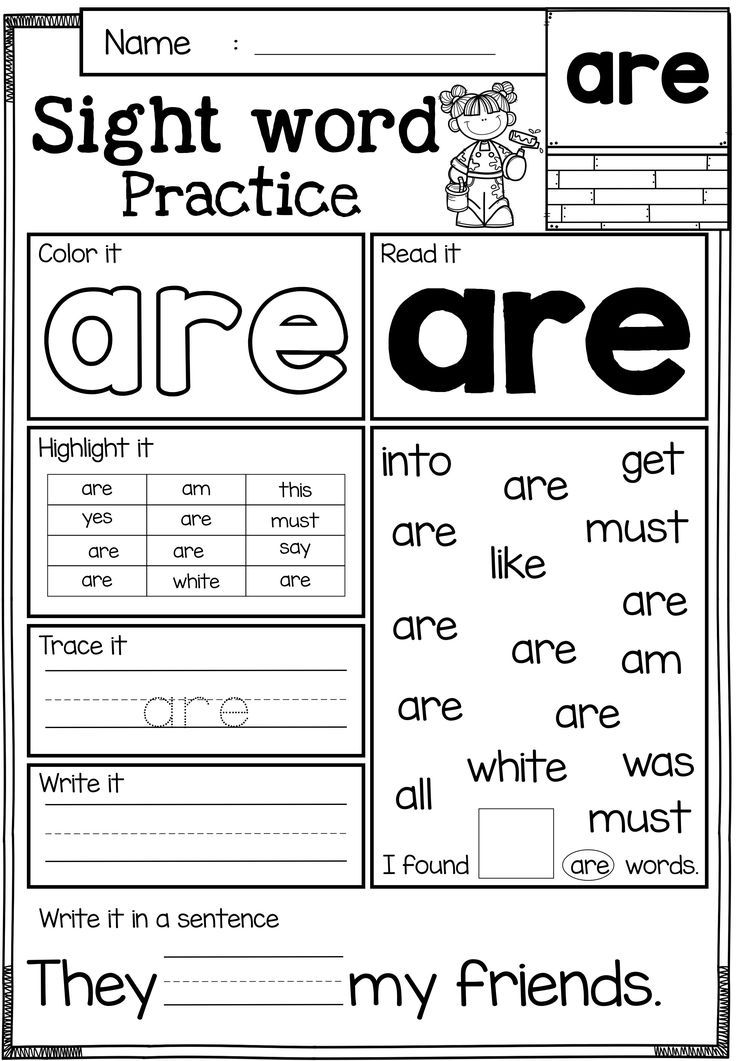

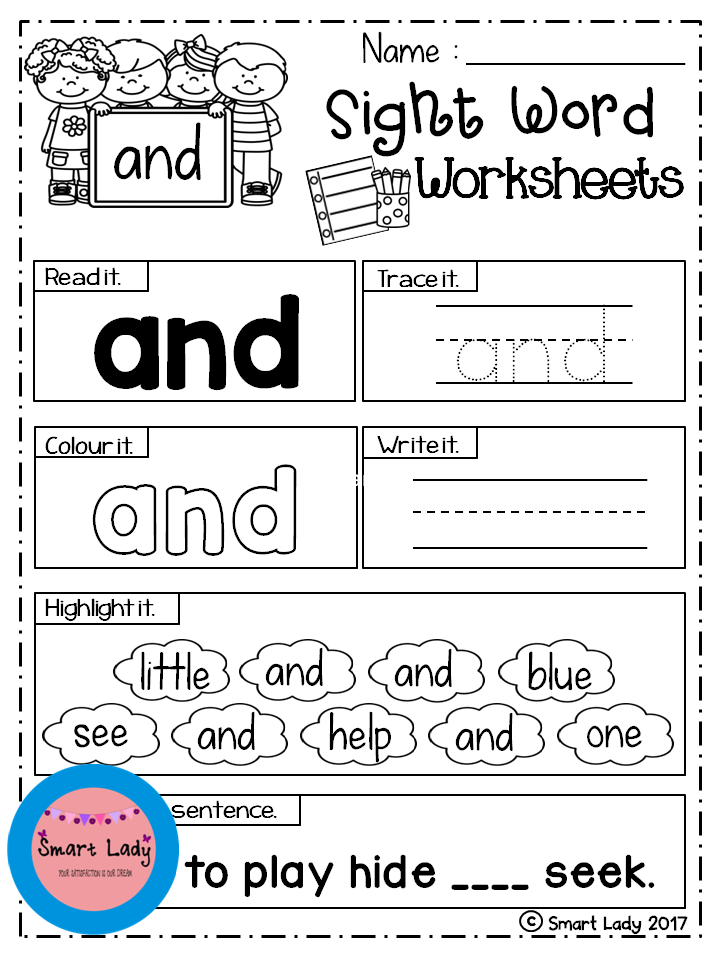

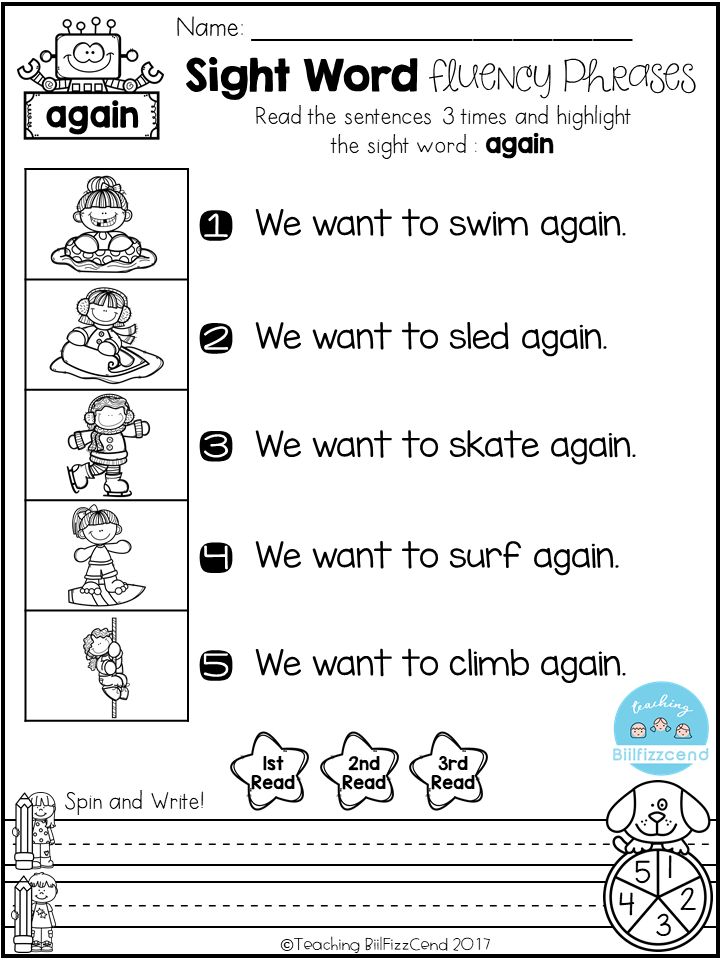

Inside: A quick and easy learning activity “Sight Word Find” – absolutely the best way for kids to work on sight

How do we make learning sight words fun?Before I even launch into this activity or the prep / how-to, I need to make something really clear: memorizing sight words is NOT reading and it is NOT how kids learn to read. Learning sight words is a very SMALL part of reading.

And while memorizing ANYTHING can be tedious and boring, we can spice it up with Sight Word Find.

RELATED: Let’s back up to the ABCs. Does your toddler know them? Here’s why you shouldn’t be worried.

Learning sight words is NOT the same as reading.When a child is reading, they are doing a complex skill involving the identification of sounds, blending those sounds, and using them to build words.

Now, when a child is learning sight words, they’re actually doing a really basic skill: memorizing. No different than when they learned letters or numbers.

Here’s a symbol – or with these words, a group of symbols – and this is what you say when you see it.

A says Aaaaaa.

/s/ /a/ /i/ /d/ says said.

Please just remember that there is a HUGE difference between the complexity of actual reading and learning sight words.

First, let your child to learn A LOT about reading.Then, introduce sight words to fill the gaps and give them words they can’t sound out.True sight words are words like the, said, come, want, was, and could.

No matter how much decoding knowledge a child has, you can’t sound these words out. But you sure do need them to make reading work.

These are the kinds of words we need to help our children memorize to help them unlock reading.

But remember, we don’t need or want our children memorizing every word. They need to have solid decoding skills to go along with these sight words.

They need to have solid decoding skills to go along with these sight words.

I based this activity off a classic from Days with Grey – hers is a name find.

For this version, I’m having my 6-year-old sight word find.

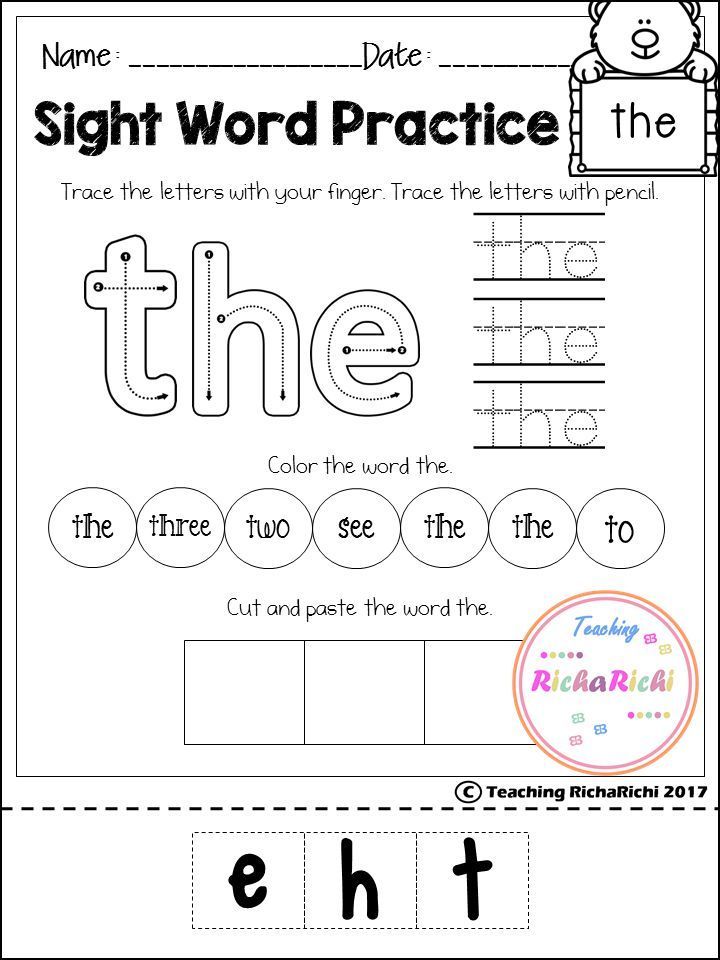

This gives him a chance to learn about sight words and practice them with his WHOLE BODY rather than asking him to memorize them off of flashcards.

When he has a chance to hunt and search for words like this, he has a chance to make the learning stick that much more.

The Materials List for sight word find activity:Busy Toddler is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program. As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases. Read more about these links in my disclosure policy.

- Butcher paper (this is what I use)

- Painter’s tape

- Markers

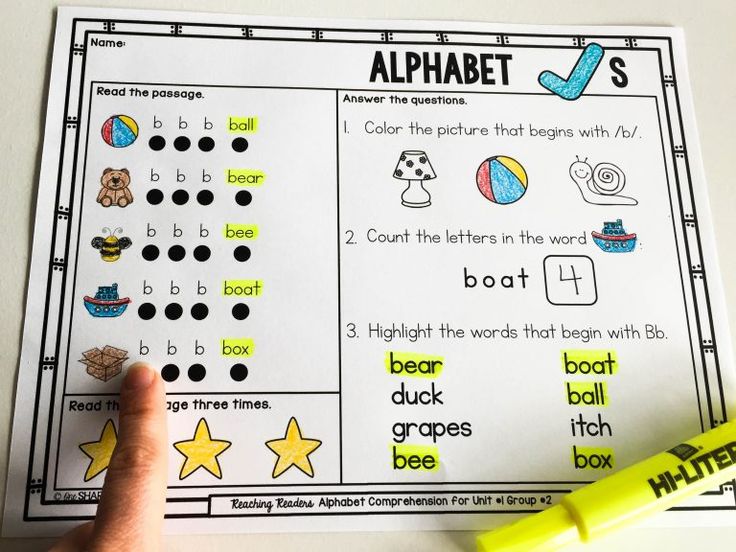

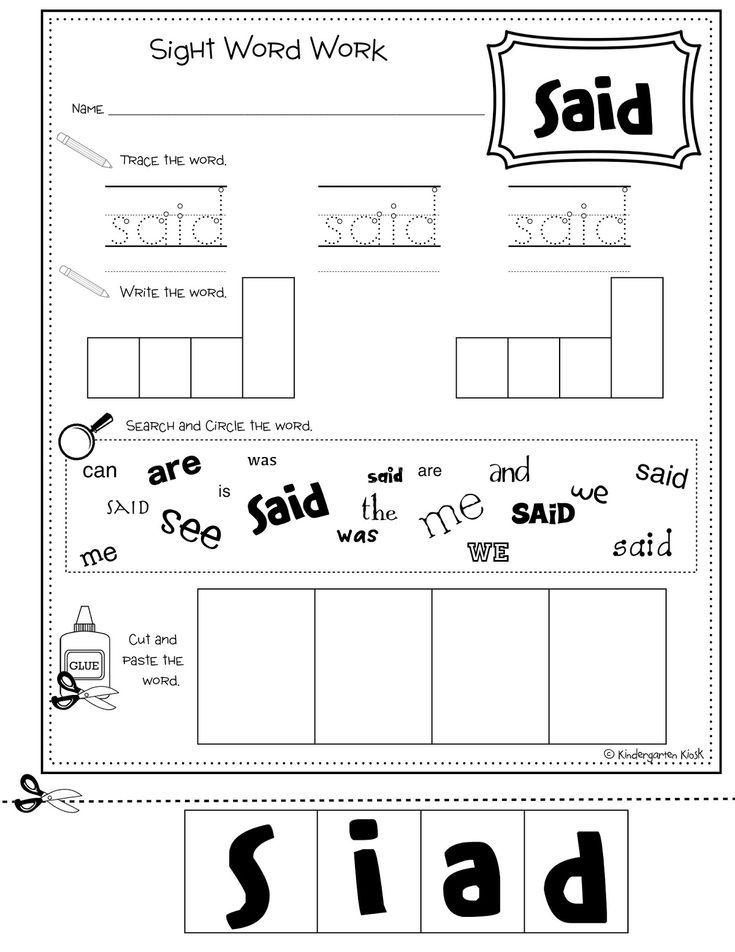

I picked 7 sight words for my son to find. I wrote them in various colors, in various directions, and using capital and lowercase letters.

I wrote them in various colors, in various directions, and using capital and lowercase letters.

RELATED: Looking for some more hands-on learning activities? Try these!

Let the fun begin!I called out a word and how to mark it: “Find the word SAID and circle it. Every time you circle it, say the word.”

We did this on repeat for all seven sight words and can you even imagine how much better and more effective this method is for learning sight words than flash cards.

He’s moving.

He’s engaging.

He’s repeating the word.

He’s visually discriminating the word from other word.

This is the kind of whole body learning we want for our children.

Sight words are great – but we need to do them rightAsking our children to memorize hundred of words, calling them sight words and then call that ready – this is not what our children need or deserve.

They deserve to learn the complex skill of reading, not a memorized half version of it.

When our children are older and reading difficult texts, trust me: the kids who actually learned to read will shine. The kids who learned to memorize will struggle.

For the words that they must learn as sight words, activities like this sight word find are the best we can offer. Fun, engaging, and memorable.

When will you make a sight word find activity?Sight Words | Sight Words: Teach Your Child to Read

Learn the history behind Dolch and Fry sight words, and why they are important in developing fluent readers.

More

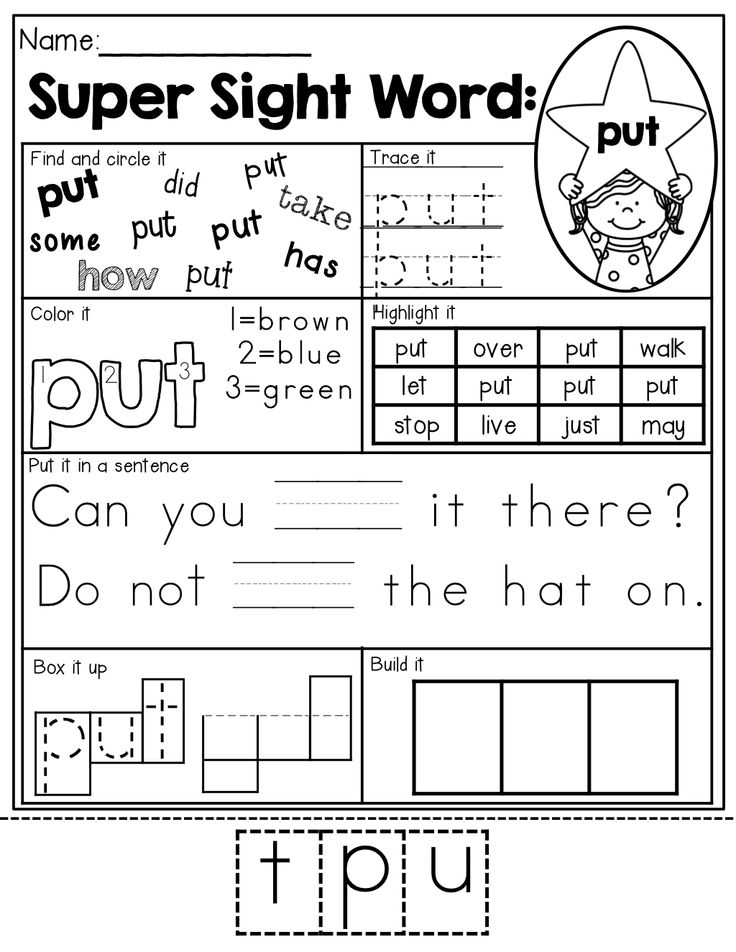

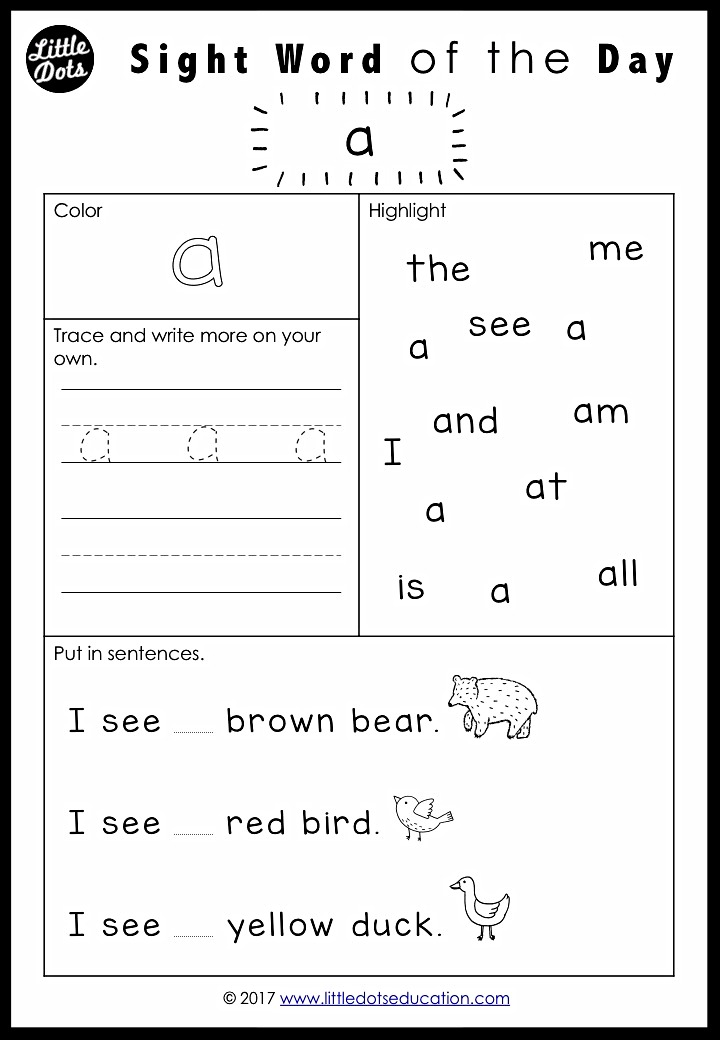

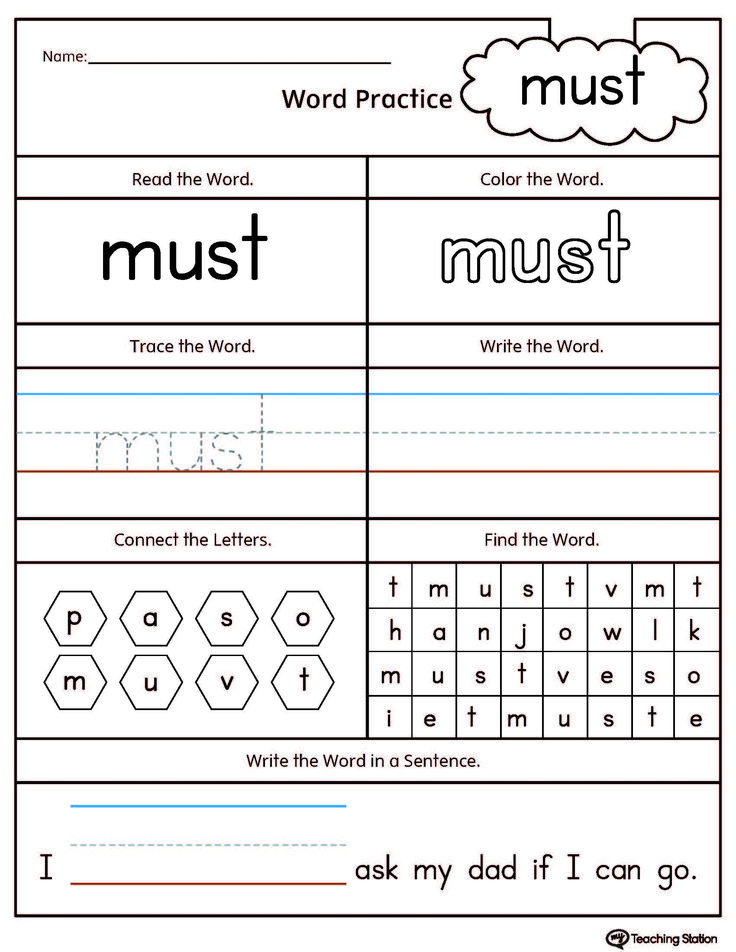

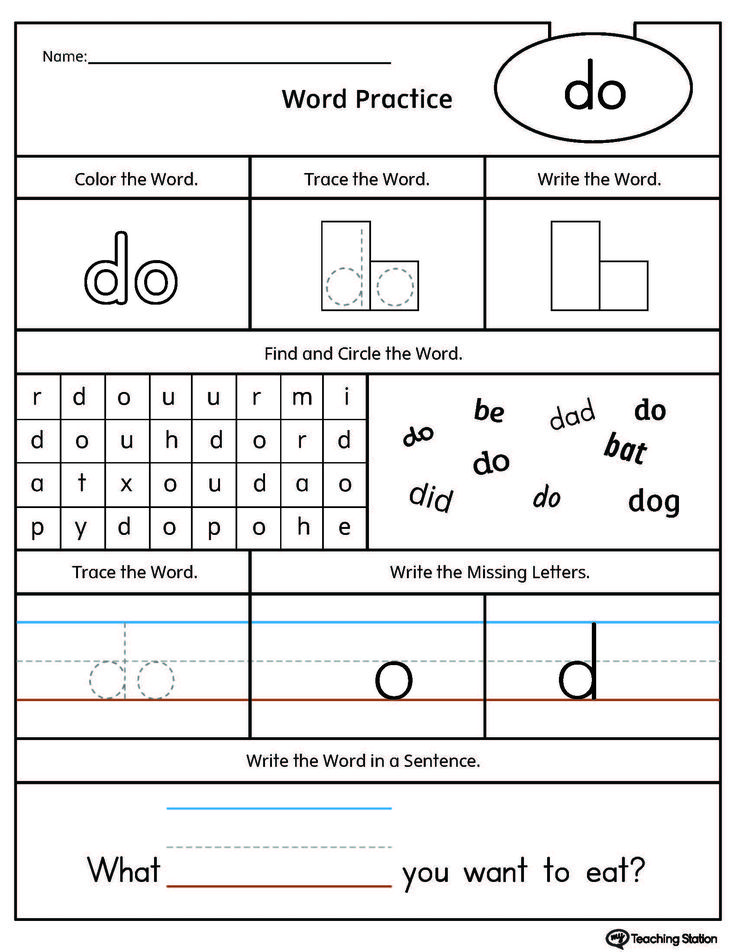

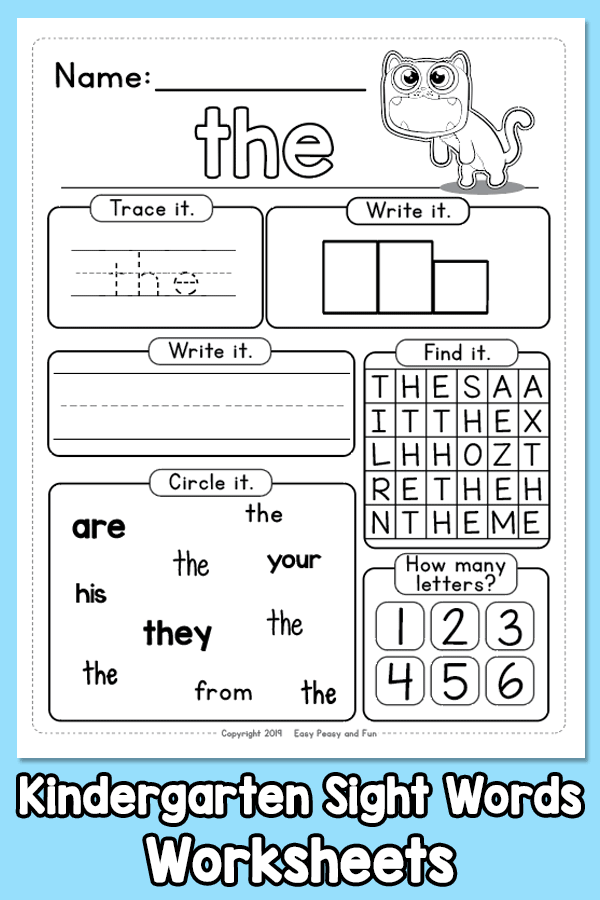

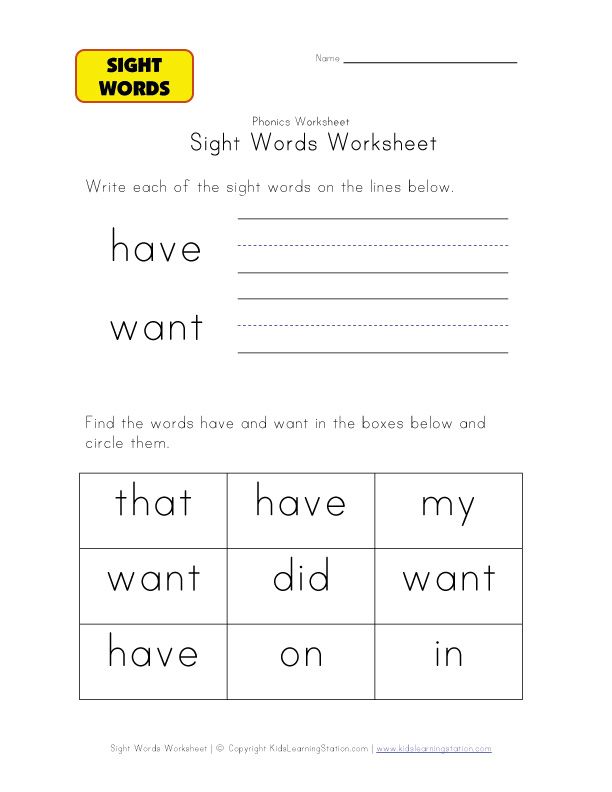

Follow the sight words teaching techniques. Learn research-validated and classroom-proven ways to introduce words, reinforce learning, and correct mistakes.

More

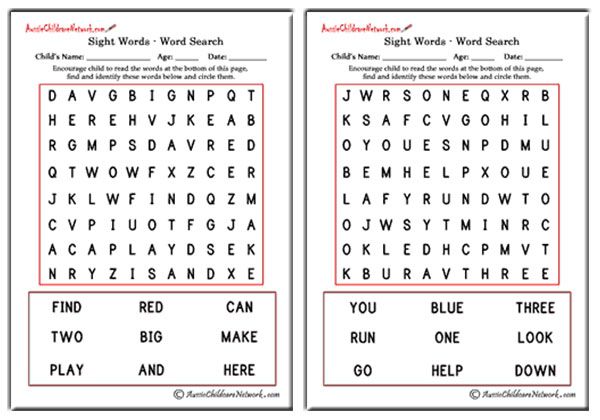

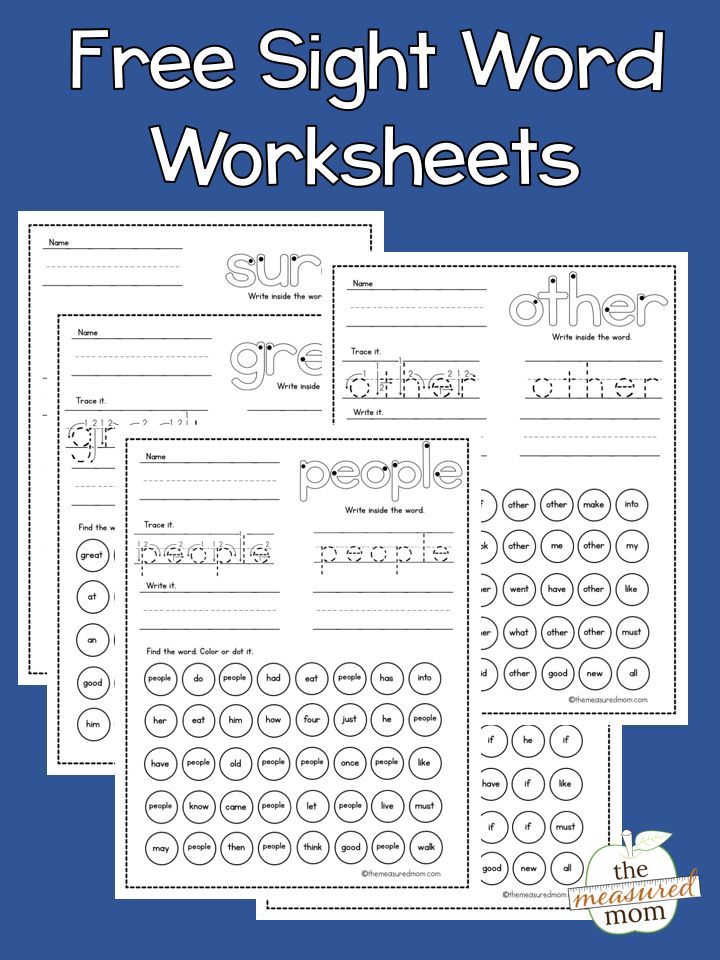

Print your own sight words flash cards. Create a set of Dolch or Fry sight words flash cards, or use your own custom set of words.

More

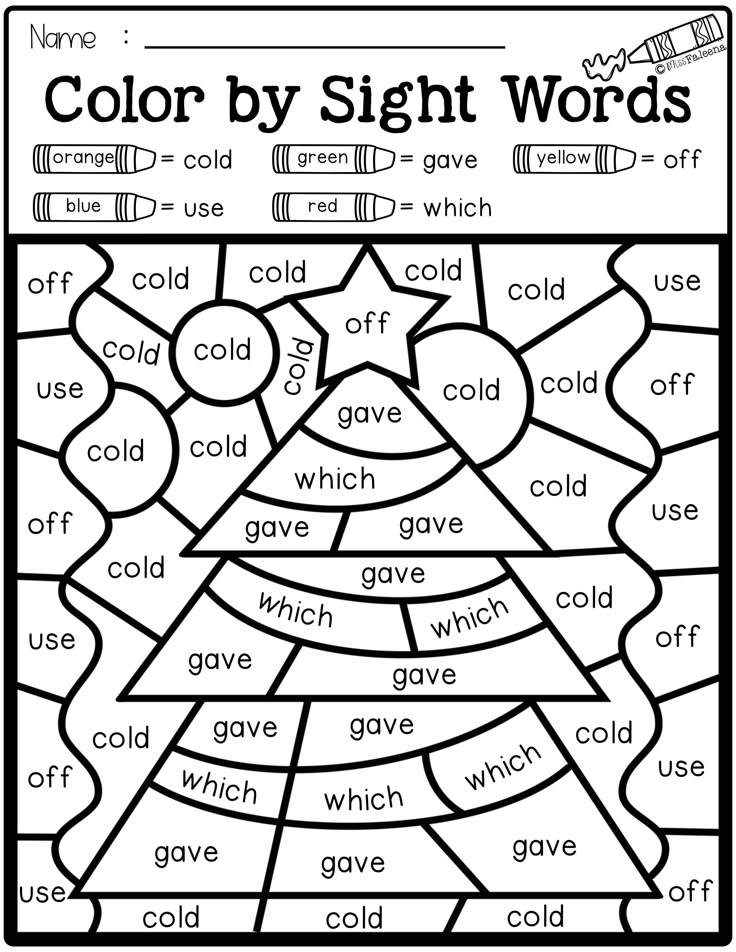

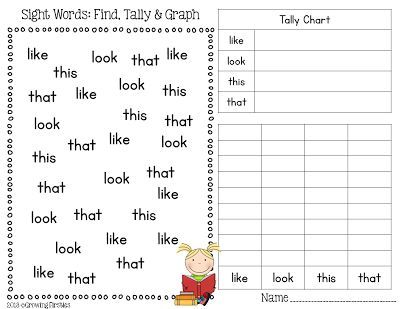

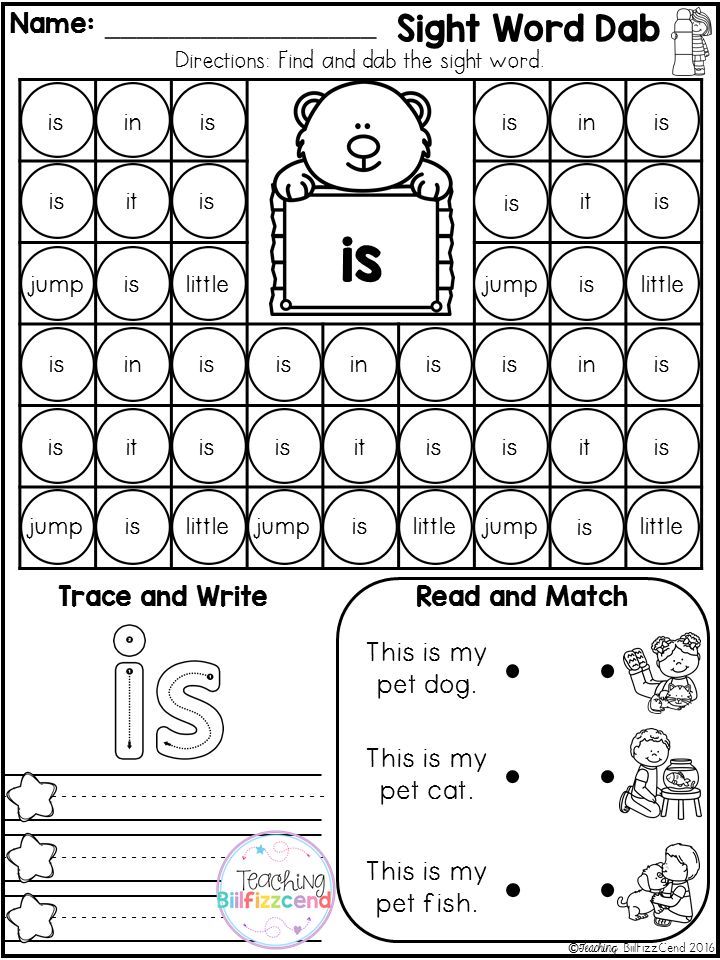

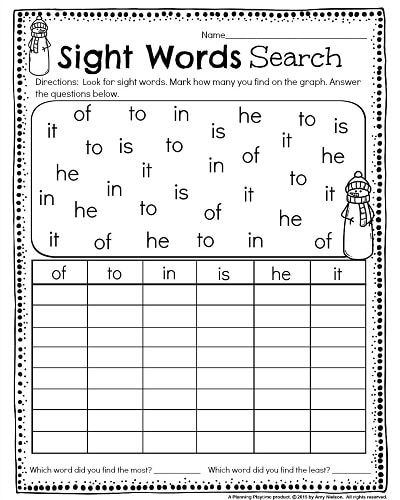

Play sight words games. Make games that create fun opportunities for repetition and reinforcement of the lessons.

More

- Overview

- What Are Sight Words?

- Types of Sight Words

- When to Start

- Scaling & Scaffolding

- Research

- Questions and Answers

Sight words instruction is an excellent supplement to phonics instruction. Phonics is a method for learning to read in general, while sight words instruction increases a child’s familiarity with the high frequency words he will encounter most often.

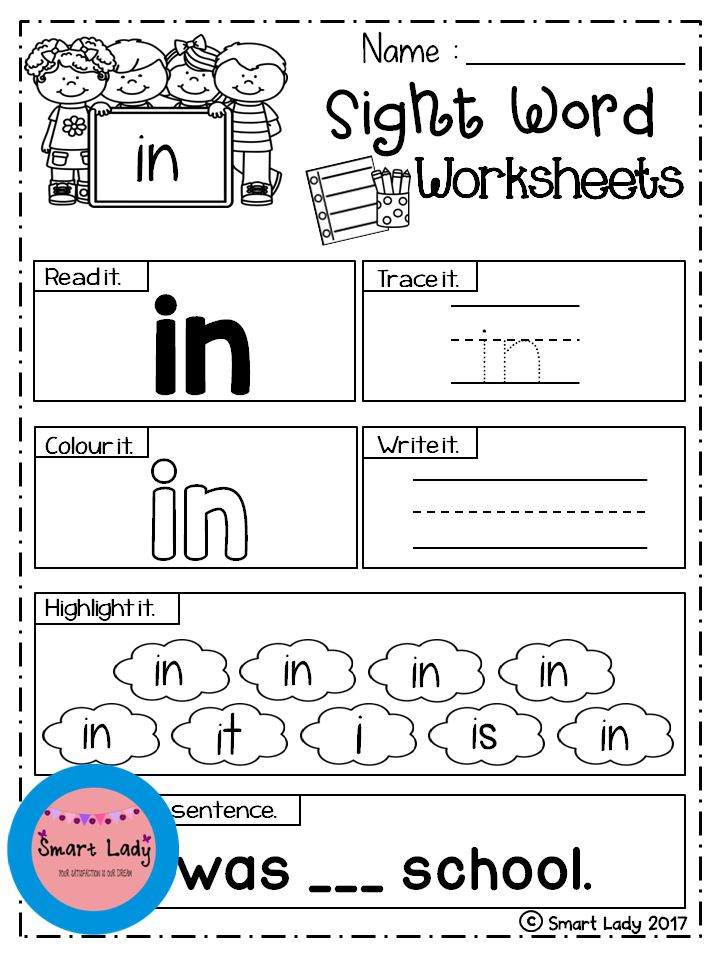

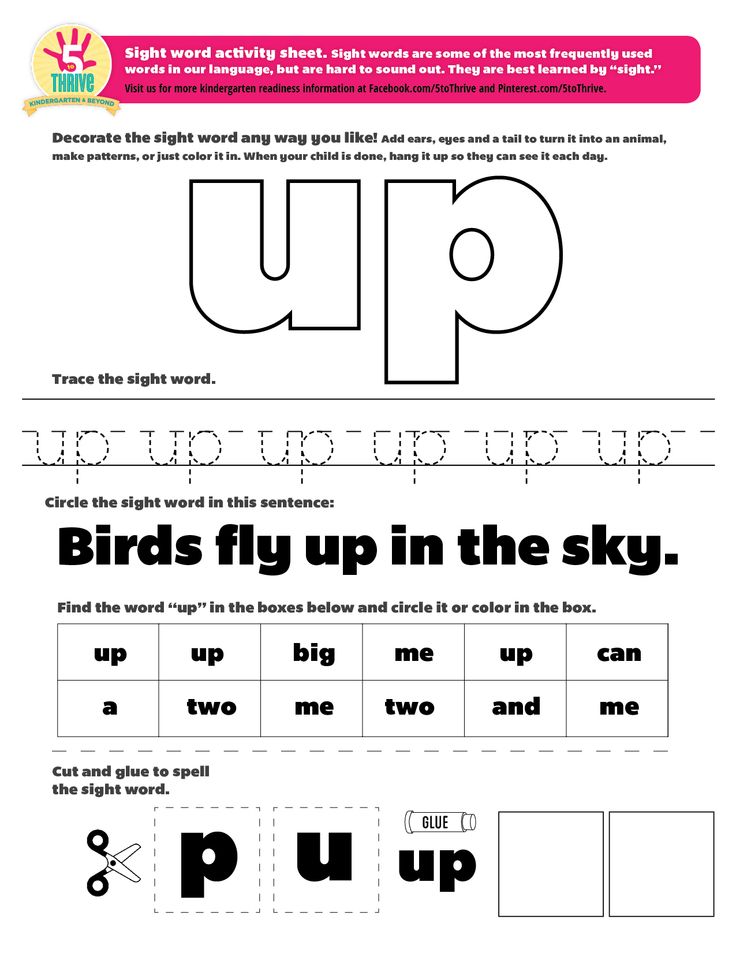

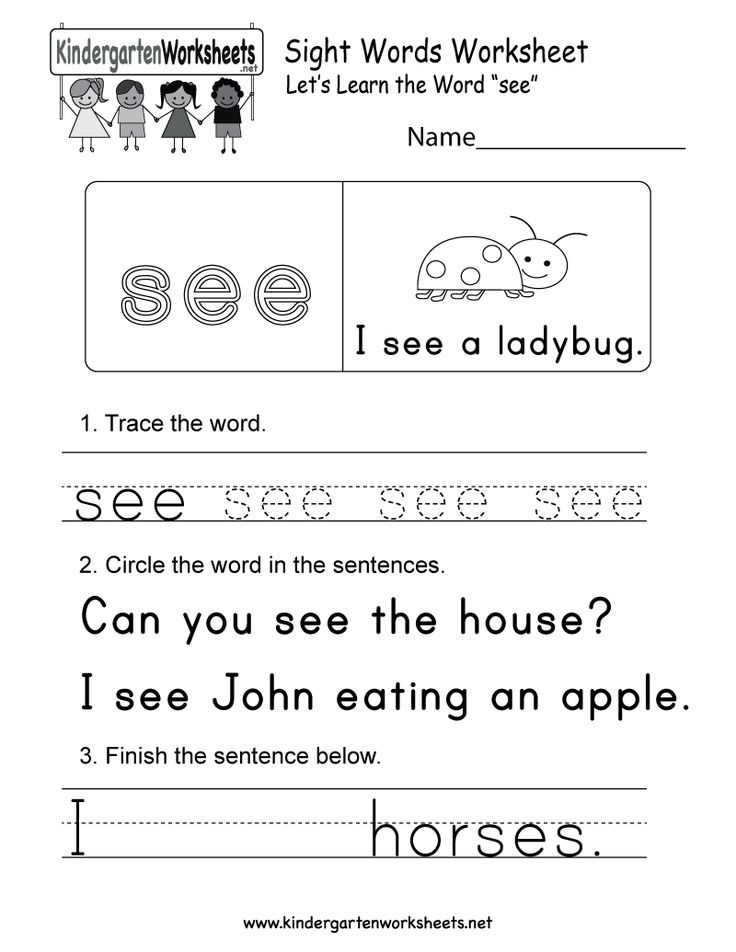

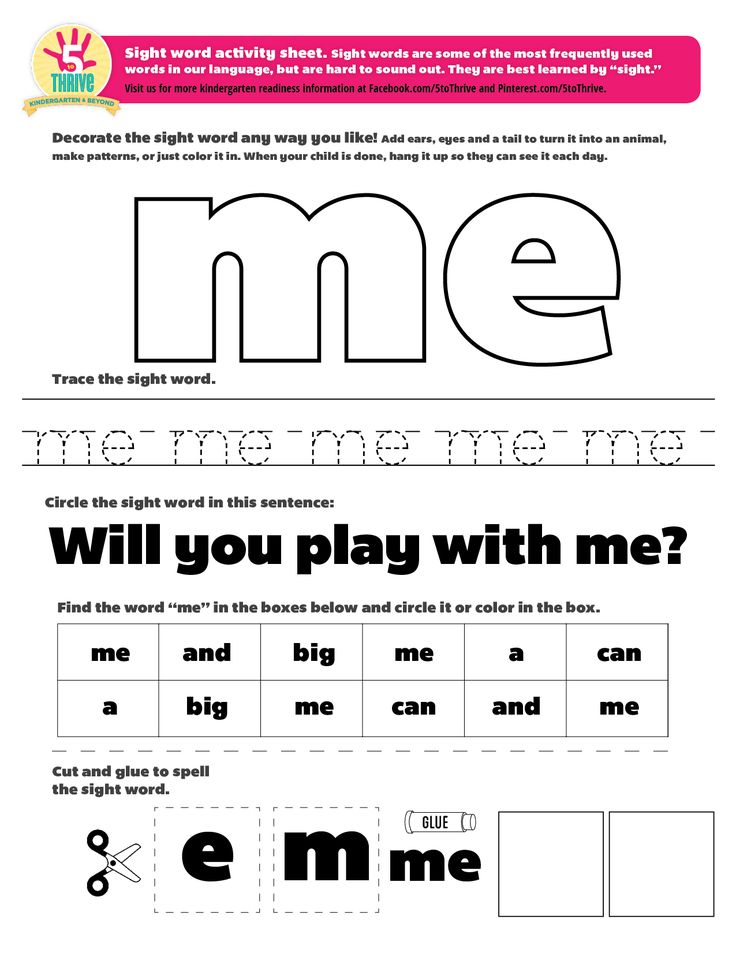

The best way to learn sight words is through lots and lots of repetition, in the form of flashcard exercises and word-focused games.

↑ Top

Sight words are words that should be memorized to help a child learn to read and write. Learning sight words allows a child to recognize these words at a glance — on sight — without needing to break the words down into their individual letters and is the way strong readers recognize most words. Knowing common, or high frequency, words by sight makes reading easier and faster, because the reader does not need to stop to try and sound out each individual word, letter by letter.

Learning sight words allows a child to recognize these words at a glance — on sight — without needing to break the words down into their individual letters and is the way strong readers recognize most words. Knowing common, or high frequency, words by sight makes reading easier and faster, because the reader does not need to stop to try and sound out each individual word, letter by letter.

Sight Words are memorized so that a child can recognize commonly used or phonetically irregular words at a glance, without needing to go letter-by-letter.

Other terms used to describe sight words include: service words, instant words (because you should recognize them instantly), snap words (because you should know them in a snap), and high frequency words. You will also hear them referred to as Dolch words or Fry words, the two most commonly used sight words lists.

Sight words are the glue that holds sentences together.

These pages contain resources to teach sight words, including: sight words flash cards, lessons, and games. If you are new to sight words, start with the teaching strategies to get a road map for teaching the material, showing you how to sequence the lessons and activities.

↑ Top

Sight words fall into two categories:

- Frequently Used Words — Words that occur commonly in the English language, such as it, can, and will. Memorizing these words makes reading much easier and smoother, because the child already recognizes most of the words and can concentrate their efforts on new words. For example, knowing just the Dolch Sight Words would enable you to read about 50% of a newspaper or 80% of a children’s book.

- Non-Phonetic Words — Words that cannot be decoded phonetically, such as buy, talk, or come.

Memorizing these words with unnatural spellings and pronunciations teaches not only these words but also helps the reader recognize similar words, such as guy, walk, or some.

Memorizing these words with unnatural spellings and pronunciations teaches not only these words but also helps the reader recognize similar words, such as guy, walk, or some.

There are several lists of sight words that are in common use, such as Dolch, Fry, Top 150, and Core Curriculum. There is a great deal of overlap among the lists, but the Dolch sight word list is the most popular and widely used.

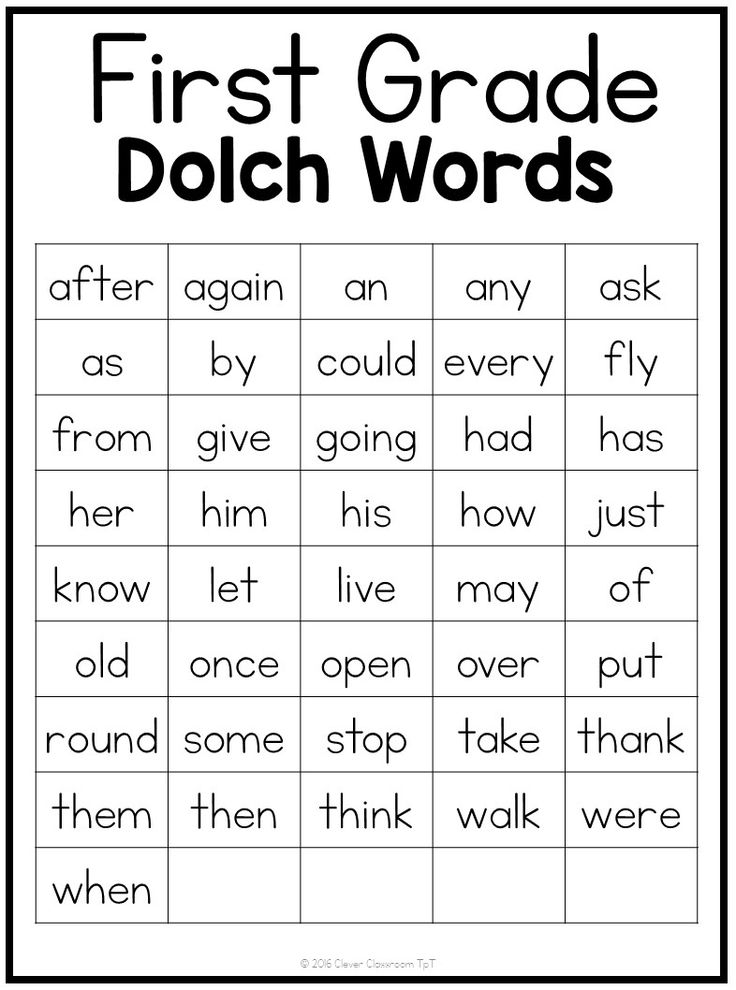

3.1 Dolch Sight Words

The Dolch Sight Words list is the most commonly used set of sight words. Educator Dr. Edward William Dolch developed the list in the 1930s-40s by studying the most frequently occurring words in children’s books of that era. The list contains 220 “service words” plus 95 high-frequency nouns. The Dolch sight words comprise 80% of the words you would find in a typical children’s book and 50% of the words found in writing for adults. Once a child knows the Dolch words, it makes reading much easier, because the child can then focus his or her attention on the remaining words.

More

3.2 Fry Sight Words

The Fry Sight Words list is a more modern list of words, and was extended to capture the most common 1,000 words. Dr. Edward Fry developed this expanded list in the 1950s (and updated it in 1980), based on the most common words to appear in reading materials used in Grades 3-9. Learning all 1,000 words in the Fry sight word list would equip a child to read about 90% of the words in a typical book, newspaper, or website.

More

3.3 Top 150 Written Words

The Top 150 Written Words is the newest of the word lists featured on our site, and is commonly used by people who are learning to read English as a non-native language. This list consists of the 150 words that occur most frequently in printed English, according to the Word Frequency Book. This list is recommended by Sally E. Shaywitz, M.D., Professor of Learning Development at Yale University’s School of Medicine.

More

3.4 Other Sight Words Lists

There are many newer variations, such as the Common Core sight words, that tweak the Dolch and Fry sight words lists to find the combination of words that is the most beneficial for reading development. Many teachers take existing sight word lists and customize them, adding words from their own classroom lessons.

↑ Top

Before a child starts learning sight words, it is important that he/she be able to recognize and name all the lower-case letters of the alphabet. When prompted with a letter, the child should be able to name the letter quickly and confidently. Note that, different from learning phonics, the child does not need to know the letters’ sounds.

Before starting sight words, a child needs to be able to recognize and name all the lower-case letters of the alphabet.

If a student’s knowledge of letter names is still shaky, it is important to spend time practicing this skill before jumping into sight words. Having a solid foundation in the ability to instantly recognize and name the alphabet letters will make teaching sight words easier and more meaningful for the child.

Having a solid foundation in the ability to instantly recognize and name the alphabet letters will make teaching sight words easier and more meaningful for the child.

Go to our Lessons for proven strategies on how to teach and practice sight words with your child.

↑ Top

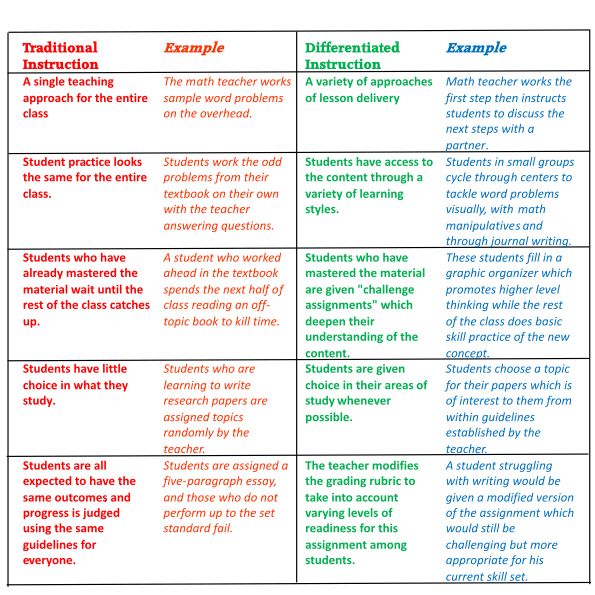

Every child is unique and will learn sight words at a different rate. A teacher may have a wide range of skill levels in the same classroom. Many of our sight words games can be adjusted to suit different skill levels.

Many of our activity pages feature recommendations for adjusting the game to the needs of your particular child or classroom:

- Confidence Builders suggest ways to simplify a sight words game for a struggling student.

- Extensions offer tips for a child who loves playing a particular game but needs to be challenged more.

- Variations suggest ways to change up the game a little, by tailoring it to a child’s special interests or making it “portable.

”

” - Small Group Adaptations offer ideas for scaling up from an individual child to a small group (2-5 children), ensuring that every child is engaged and learning.

↑ Top

Our sight words teaching techniques are based not only on classroom experience but also on the latest in child literacy research. Here is a bibliography of some of the research supporting our approach to sight words instruction:

- Ceprano, M. A. “A review of selected research on methods of teaching sight words.” The Reading Teacher 35:3 (1981): 314-322.

- Ehri, Linnea C. “Grapheme–Phoneme Knowledge Is Essential for Learning to Read Words in English.” Word Recognition in Beginning Literacy. Mahwah, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates, 1998.

- Enfield, Mary Lee, and Victoria Greene. Project Read. www.projectread.com. 1969.

- Gillingham, Anna, and Bessie W. Stillman.

The Gillingham Manual: Remedial Training for Students with Specific Disability in Reading, Spelling, and Penmanship, 8th edition. Cambridge, MA: Educators Publishing Service, 2014.

The Gillingham Manual: Remedial Training for Students with Specific Disability in Reading, Spelling, and Penmanship, 8th edition. Cambridge, MA: Educators Publishing Service, 2014. - Nist, Lindsay, and Laurice M. Joseph. “Effectiveness and Efficiency of Flashcard Drill Instructional Methods on Urban First-Graders’ Word Recognition, Acquisition, Maintenance, and Generalization.” School Psychology Review 37:3 (Fall 2008): 294-308.

- Shaywitz, Sally E. Overcoming Dyslexia: A New and Complete Science-Based Program for Reading Problems at Any Level. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003.

- Stoner, J.C. “Teaching at-risk students to read using specialized techniques in the regular classroom.” Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal 3 (1991).

- Wilson, Barbara A. “The Wilson Reading Method.” Learning Disabilities Journal 8:1 (February 1998): 12-13.

- Wilson, Barbara A. Wilson Reading System.

Millbury, MA: Wilson Language Training, 1988.

Millbury, MA: Wilson Language Training, 1988.

↑ Top

Leave a Reply

Read online Targeted Thinking. Decision-making according to the methods of the British special services”, David Omand – LitRes

Translator Vsevolod Baronin

Scientific editor Denis Bukin Chief Editor S. Turko

Project Manager O. Ravdanis

Art Director Yu. Buga

Cover design D. Izotov

Corrector E. Chudinova

Computer layout A. Abramov

Illustration on Shutterstock.com

© 20000 9000

THE AISSA MORTED rights

All rights reserved

Original English language edition first published by Penguin Books Ltd, London

© Russian edition, translation, layout. Alpina Publisher LLC, 2022

All rights reserved. This e-book is intended solely for private use for personal (non-commercial) purposes. The e-book, its parts, fragments and elements, including text, images and others, may not be copied or used in any other way without the permission of the copyright holder. In particular, such use is prohibited, as a result of which an electronic book, its part, fragment or element becomes available to a limited or indefinite circle of persons, including via the Internet, regardless of whether access is provided for a fee or free of charge.

The e-book, its parts, fragments and elements, including text, images and others, may not be copied or used in any other way without the permission of the copyright holder. In particular, such use is prohibited, as a result of which an electronic book, its part, fragment or element becomes available to a limited or indefinite circle of persons, including via the Internet, regardless of whether access is provided for a fee or free of charge.

Copying, reproduction and other use of an e-book, its parts, fragments and elements, beyond private use for personal (non-commercial) purposes, without the consent of the copyright holder is illegal and entails criminal, administrative and civil liability.

* * *

Dedicated to Keira, Robert, Beatrice and Ada

with the hope that they will grow up in a better world

Science editor's preface

This is a book about the art of thinking. Logic is a wonderful science, it gives the laws of strict, unmistakable and impeccable thinking. But life rarely provides enough information for impeccable logical conclusions. It is easy to talk about abstract things without having to do anything. In real life, when there is neither clarity nor time to clarify the facts, and circumstances force you to act, you have to rely on what is - conditionally reliable information. David Omand has lived the life of an intelligence official, in which it is not customary to answer “I don’t know,” so he rightfully shares his practical ability to build a picture of several pieces of the puzzle. Using his approaches, you can “wash” a good result from an unreliable information breed. Yes, at times you will be mistaken, but you will be able to act, and that's fine.

But life rarely provides enough information for impeccable logical conclusions. It is easy to talk about abstract things without having to do anything. In real life, when there is neither clarity nor time to clarify the facts, and circumstances force you to act, you have to rely on what is - conditionally reliable information. David Omand has lived the life of an intelligence official, in which it is not customary to answer “I don’t know,” so he rightfully shares his practical ability to build a picture of several pieces of the puzzle. Using his approaches, you can “wash” a good result from an unreliable information breed. Yes, at times you will be mistaken, but you will be able to act, and that's fine.

We have few books on methods of thinking, especially those related to intelligence. The last similar one, Washington Platt's Strategic Intelligence Information Work, was published in Russian back in 1958, and it is still recommended in specialized educational institutions to this day. At the same time, books on the work of an intelligence analyst are published regularly in English. Perhaps we are hindered by the excessive tendency of the domestic military departments to classify everything in the world, including the old, irrelevant and even known to everyone. Without a solid texture, writing a book will not work, and a fictional texture is unconvincing. Well, as long as there are no domestic books, we will read translated ones.

At the same time, books on the work of an intelligence analyst are published regularly in English. Perhaps we are hindered by the excessive tendency of the domestic military departments to classify everything in the world, including the old, irrelevant and even known to everyone. Without a solid texture, writing a book will not work, and a fictional texture is unconvincing. Well, as long as there are no domestic books, we will read translated ones.

And one more thing. As I edited this book, I often thought of Jerome K. Jerome: “In war, the soldiers of every country are always the bravest in the world. The soldiers of a hostile country are always treacherous and treacherous - that's why they sometimes win" [1] . In other cases, patriotism is an excellent virtue, but it is hardly good in intelligence, where independence of mind is much more valuable. There is no unity of interests between the various intelligence services of the country, just as there is none within the intelligence service, nor within its smallest subdivision. Deeds are determined not by organizations, but by a bizarre interaction of multidirectional interests of influential people, and these interests do not always consist in selfless service to the fatherland. Undoubtedly, any smart intelligence officer (and others in high positions are inappropriate) understands this, but will he openly write about it? Only sometimes, between the lines. And in other cases - to demonstrate ardent confidence in the correctness of the "good guys". Fortunately, fiction writers write about human ups and downs in intelligence. I am sure it will be easier to understand what is written here between the lines, recalling at times the novels of John Le Carré or the films based on these novels: The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965) and "Spy, get out!" (2011).

Deeds are determined not by organizations, but by a bizarre interaction of multidirectional interests of influential people, and these interests do not always consist in selfless service to the fatherland. Undoubtedly, any smart intelligence officer (and others in high positions are inappropriate) understands this, but will he openly write about it? Only sometimes, between the lines. And in other cases - to demonstrate ardent confidence in the correctness of the "good guys". Fortunately, fiction writers write about human ups and downs in intelligence. I am sure it will be easier to understand what is written here between the lines, recalling at times the novels of John Le Carré or the films based on these novels: The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965) and "Spy, get out!" (2011).

Denis Bukin

Foreword

Why We Need These Lessons: In Search of Independence of Thought, Honesty and Integrity

Westminster, March 1982. "This is very serious, isn't it?" asked Margaret Thatcher. She frowned and looked up from the intelligence reports I had given her. “Yes, Prime Minister,” I replied, “this information can be interpreted unambiguously: the Argentine junta is in the final stages of preparations for an invasion of the Falklands. It is highly probable that the invasion will take place next Saturday.”

"This is very serious, isn't it?" asked Margaret Thatcher. She frowned and looked up from the intelligence reports I had given her. “Yes, Prime Minister,” I replied, “this information can be interpreted unambiguously: the Argentine junta is in the final stages of preparations for an invasion of the Falklands. It is highly probable that the invasion will take place next Saturday.”

This conversation took place on the afternoon of Wednesday, March 31, 1982.

I was Chief Private Secretary to Secretary of Defense John Knott. We were sitting in his office in the House of Commons preparing for a speech in parliament when a liaison officer from military intelligence headquarters hurried into the government building. In his mail bag were several very conspicuously designed folders. From the red diagonal crosses on their dark covers, I immediately knew that they contained top secret material covered with a special code word UMBRA, meaning that they came from the Government Communications Center.

These folders contained decrypted radio intercepts from the Argentine navy. Reports said that an Argentine submarine was conducting covert reconnaissance near the capital of the Falkland Islands, the city of Stanley, and that the Argentine navy, which was on the exercises, was re-forming itself into battle formation. Another, more recent radio intercept mentioned an Argentine Navy task force that was due to arrive at an unspecified location early Friday, April 2. After analyzing the coordinates of the ships of this formation, the government communications headquarters came to the conclusion that only Port Stanley could be the target of the Argentines [2] .

John Knott and I looked at each other with one single thought: the loss of the Falklands would pose the gravest threat to the existence of Margaret Thatcher's government: therefore, the Prime Minister must be immediately informed of these radio intercepts. We hurried down the corridor to her office and literally burst into it.

The latest analysis the Prime Minister received from the UK Joint Intelligence Committee was that Argentina was unwilling to use military force to secure its claim to the sovereignty of the Falkland Islands. However, the Joint Intelligence Committee warned that if the British took extremely provocative action against Argentine citizens who had illegally landed on the British island of South Georgia in the South Atlantic, the junta could use this as a pretext to start hostilities. Since Britain had no intention of provoking the junta, such an assessment was misinterpreted in Whitehall as encouraging, which made the fresh intelligence all the more stunning. This was the first sign that the Argentine junta was ready to use military force to impose its demands.

The Importance of Reasoning

The shock of how the UK suddenly became involved in the Falklands Crisis is deeply ingrained in my memory. The situation showed me how important errors in our thinking can be. This is as true in the lives of individuals as it is in the administration of public affairs. And my goal in writing this book is ambitious: I want to empower people to make better decisions based on the way intelligence analysts think. I will bring lessons from our past to show exactly how one can know, explain and predict most of all the events that we face in our absolutely amazing age.

This is as true in the lives of individuals as it is in the administration of public affairs. And my goal in writing this book is ambitious: I want to empower people to make better decisions based on the way intelligence analysts think. I will bring lessons from our past to show exactly how one can know, explain and predict most of all the events that we face in our absolutely amazing age.

There are important life lessons to be learned from observing how intelligence analysts think. By studying their actions during problem solving in real situations in recent history, we learn how they organize their thoughts, distinguish between the probable and the improbable, and thus draw better conclusions. We will learn how to methodically test alternative explanations for what is happening and assess how much we need to change our own opinion as new information becomes available to us. We will try to understand how our own feelings, as well as the opinions of members of a particular community, can influence our judgments. We will also learn how one can fall prey to conspiracy thinking and be deceived through deliberate misinformation.

We will also learn how one can fall prey to conspiracy thinking and be deceived through deliberate misinformation.

We all face decision-making and choice processes, whether at home, at work or at play. But today, compared with the old days, we have negligibly little time to make a decision. We live in the digital age and are bombarded with conflicting, false and confusing information from a vast array of sources – more than ever. Information surrounds us from all sides, and we feel obliged to respond to it at the same speed with which it comes to us. There are powerful forces playing against us through messages and opinions spread through social media. We find ourselves overwhelmed by all this information and ask ourselves the question: have we become more or less ignorant than in former times? Today we need these lessons from the past, more than ever.

Looking over the shoulder of an intelligence analyst

In the history of the art of war, it has become clear to commanders the advantage that intelligence can provide.

Governments today are deliberately creating specialized services to access and analyze information that can help them make better decisions [3] . The Secret Intelligence Service of the British Foreign Office (MI6) oversees the work of intelligence agents abroad. Security Services (MI5) and its law enforcement partners investigate domestic threat situations and monitor suspects. The Government Communications Center is engaged in the interception of radio and electronic communications and the collection of digital intelligence. The military has its fair share of intelligence-gathering operations abroad, including photo reconnaissance from satellites and unmanned aerial vehicles. The task of the intelligence analyst is to piece together all the pieces of information received. Analysts are then identified with situation assessments designed to raise awareness among decision makers. They figure out what is happening, explain why it is happening, and describe how the situation might develop [4] .

The more we understand the nature of the decisions we must make, the less likely we are to misinterpret the facts, make bad choices, or be seriously surprised by the outcome. Much of what we need can be obtained from open sources, but only if we are careful enough to critically judge the quality of the information.

Being informed by the decision maker does not necessarily mean simplifying the situation. Often the assessment coming from the intelligence service is to warn that the circumstances are more complex than previously thought, that the very motivation of the enemy's behavior must be feared, and that the situation as a whole may develop in an undesirable direction. You need to have information. Having illusions in such matters leads to poor or even disastrous decisions. The task of the intelligence officer is to provide the government with information as it really is. But when you make decisions, it depends only on you, how objective and honest you are with yourself.

The work of spies includes stealing the secrets of dictators, terrorists and criminals. This is done using human or technical means and involves intrusion into personal correspondence or verbal communications. In this way, we give our intelligence officers the right to act in accordance with ethical standards that are different from those that we would like to see in everyday life. Such norms are justified by reducing the damage to society that can be achieved with such work [5] . Authoritarian states may well assume that their intelligence agencies will do without restraint and encourage their agents to do whatever they deem necessary to achieve their goals, regardless of compliance with laws or rules of conduct. In democracies, such behavior by agents will quickly undermine the credibility of both the government and the intelligence services. Consequently, intelligence activities are carefully regulated by domestic law to ensure that they remain necessary in scope and commensurate with the level of threats. So I'm making it clear that this book does not teach you how to spy on others and should not motivate you to do so. What I want to show, however, is the ways in which secret intelligence is based on ways of thinking that we can all benefit from. This book is a guide to right thinking, not a guide to bad behavior.

So I'm making it clear that this book does not teach you how to spy on others and should not motivate you to do so. What I want to show, however, is the ways in which secret intelligence is based on ways of thinking that we can all benefit from. This book is a guide to right thinking, not a guide to bad behavior.

Such thinking is not only dispassionate, cold-blooded calculation. "Negative ability" is how the poet John Keats described the writer's ability to pursue the vision of artistic beauty, even when it led to uncertainty, confusion and intellectual doubt in the process of creating a work. For analytical thinking, its equivalent is the ability to endure painful experiences and confusion from ignorance, and not the imposition of ready-made or universal solutions in ambiguous situations or emotional challenges [6] . In order to think clearly, we must have a scientific, evidence-based approach that nonetheless contains room for the "negative ability" needed to maintain open-minded thinking [7] .

Intelligence analysts like to look ahead, but they do not pretend to be predictors. There will always be unexpected results, no matter how hard we try to predict events with all diligence. The winner of the Grand National or the Indy 500 cannot be known in advance. Events sometimes develop in such a way that, as it seems to us, they are destined to confuse us. It is important to note that risk can also lead to the realization of certain opportunities - if, of course, we can use intelligence to overcome such risks.

Who am I?

The secret services prefer to remain silent about their successes in order to be able to repeat them, but the failures of the special services can become public knowledge. In the book, I have given examples of such successes and failures, along with several events from my own experience - more precisely, that part of it that is associated with the amazing development of the digital world. It's amusing when you remember that I started my first full-time job in 1965 in the mathematics department of an engineering company in Glasgow, where we learned how to write machine codes for early computers using five-character perforated paper tape to enter programs. Today, the mobile device in my pocket has direct access to more computing power than was available back in 1965 all over Europe. This digitization of our lives brings us great benefits, but it is also fraught with dangers, which will be discussed in Chapter 10 of this book.

Today, the mobile device in my pocket has direct access to more computing power than was available back in 1965 all over Europe. This digitization of our lives brings us great benefits, but it is also fraught with dangers, which will be discussed in Chapter 10 of this book.

In 1969, just after graduating from the University of Cambridge, I joined the Government Communications Centre, the UK intelligence agency responsible for the electronic intelligence and information security of government agencies and the army, where I learned about the pioneering work of the Center for the Application of Mathematics and Data Processing in intelligence activities. I abandoned my plans for a doctorate in theoretical economics and the temptation to become an economic adviser to Her Majesty's Treasury. Instead, I chose a career as a civil servant, which opened doors to the world of intelligence, defense, and national security. While serving in the Department of Defense as Assistant Chief of Staff for Military Policy, I used intelligence data to make recommendations to ministers and chiefs of staff. I worked three times in the private office of the Secretary of Defense (six ministers, to be exact - from Lord Carrington at 1973 to John Knott in 1981) and has repeatedly observed the heavy burden of decision-making in a crisis placed on the political leadership of the country. I've seen how good intelligence can be useful to a cause, and what problems its absence causes. When I worked as a UK Defense Adviser at NATO Headquarters in Brussels, it was clear to me how intelligence work shapes arms control and a nation's foreign policy. And as Assistant Undersecretary of Defense for Policy, I was an extremely voracious customer for operational intelligence on the crisis in the former Yugoslavia. In this capacity, I became a member of the UK Joint Intelligence Committee, the key intelligence-assessment unit of the Kingdom's Cabinet, in which I served for a total of seven years.

I worked three times in the private office of the Secretary of Defense (six ministers, to be exact - from Lord Carrington at 1973 to John Knott in 1981) and has repeatedly observed the heavy burden of decision-making in a crisis placed on the political leadership of the country. I've seen how good intelligence can be useful to a cause, and what problems its absence causes. When I worked as a UK Defense Adviser at NATO Headquarters in Brussels, it was clear to me how intelligence work shapes arms control and a nation's foreign policy. And as Assistant Undersecretary of Defense for Policy, I was an extremely voracious customer for operational intelligence on the crisis in the former Yugoslavia. In this capacity, I became a member of the UK Joint Intelligence Committee, the key intelligence-assessment unit of the Kingdom's Cabinet, in which I served for a total of seven years.

By the time I left the Department of Defense to return to the Government Communications Center as its director in the mid-1990s, computing had completely transformed the ability to process, store, and retrieve data on an unheard-of scale. I still remember how engineers triumphantly reported to me that they had managed to achieve stable storage of a terabyte of data with fast access - a big step at the time, although my small laptop today has only half the memory. More importantly, the Internet has become an important area of work for professionals, the World Wide Web has gained popularity, and the new Microsoft Hotmail service has made e-mail a fast and reliable form of communication. We knew that digital technologies would sooner or later permeate all areas of our lives and that organizations such as the Government Communications Center would have to radically change to cope with the challenges that arise as life and society become digital [8] .

I still remember how engineers triumphantly reported to me that they had managed to achieve stable storage of a terabyte of data with fast access - a big step at the time, although my small laptop today has only half the memory. More importantly, the Internet has become an important area of work for professionals, the World Wide Web has gained popularity, and the new Microsoft Hotmail service has made e-mail a fast and reliable form of communication. We knew that digital technologies would sooner or later permeate all areas of our lives and that organizations such as the Government Communications Center would have to radically change to cope with the challenges that arise as life and society become digital [8] .

The pace of digitalization has been faster than expected. In those years, smartphones had not yet been invented, and, naturally, there were no Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and other social media platforms and related applications. What was to become the Google search engine was at that time just a research project at Stanford University. During this small part of my working life, I saw how these and many other revolutionary achievements began to dominate our world. In less than 20 years, our economic, social and cultural priorities have come to depend on access to connected digital technologies and on learning to coexist safely with them. There is no way back.

During this small part of my working life, I saw how these and many other revolutionary achievements began to dominate our world. In less than 20 years, our economic, social and cultural priorities have come to depend on access to connected digital technologies and on learning to coexist safely with them. There is no way back.

When, in 1997, I was unexpectedly appointed as Permanent Under Secretary of State for the Home Office, this led to my close association with MI5 and Scotland Yard. These services used intelligence in investigations aimed at identifying and eliminating internal threats, including the activities of terrorist and organized crime groups. It was during this period that the Ministry of the Interior developed the Human Rights Law (1998) and legislation regulating and supervising the powers of the investigating authorities to ensure a permanent balance between our basic rights to life and security and the right to privacy in her personal and family sphere. . My career as Deputy Home Secretary was continued after the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 as the UK's first ever Security and Intelligence Coordinator. Back then, back at the UK Joint Intelligence Committee, I was responsible for keeping the British intelligence community running smoothly and developing the first UK counter-terrorism strategy, CONTEST, which is still active as of this writing in 2020.

Back then, back at the UK Joint Intelligence Committee, I was responsible for keeping the British intelligence community running smoothly and developing the first UK counter-terrorism strategy, CONTEST, which is still active as of this writing in 2020.

In this book, I offer you lessons from the world of intelligence, not only from within the intelligence service itself, but also from the perspective of a politician as an intelligence user. I have learned the hard way that intelligence is hard to come by, always fragmented and incomplete, and sometimes erroneous. But if you work with them consistently and with an understanding of the limitations of the information contained in them, then their significant role and benefit for ensuring the safety of society becomes obvious. The exact same is true for you.

BOOV: A Method of Analytical Thinking

I am currently an adjunct professor of intelligence at the Department of Military Studies at King's College London, at the Institute of Political Studies in Paris, and at the Defense University of Oslo. It's been my experience that having a methodology to review the decision making process and establish an appropriate level of trust in them really helps. The methodology I have developed - let me call it the abbreviation VOOV - is based on four types of information processing that allow you to form an intellectual product obtained at different levels of analysis:

It's been my experience that having a methodology to review the decision making process and establish an appropriate level of trust in them really helps. The methodology I have developed - let me call it the abbreviation VOOV - is based on four types of information processing that allow you to form an intellectual product obtained at different levels of analysis:

● Mastery of the situation: what is happening and what we are facing right now.

● An explanation of why we see what we see and the motivations of those involved in the current event.

● Estimates and forecasts of the development of an event under various circumstances.

● Development of a strategic notification of problems that may arise in the long term.

There is a powerful logic behind this fourfold way of thinking, the BOOB methodology.

Take as an example an investigation into an attack by far-right extremists. The first step is to find out as precisely as possible what is going on. As a starting point, the police will gather information about known crimes, interview witnesses, and obtain forensic evidence. Nowadays, there is also a fair amount of information available on social networks and the Internet, but the credibility of such sources requires careful verification. In fact, even well-verified facts can be interpreted in completely different ways, which can lead to erroneous exaggeration or underestimation of the problem under investigation.

As a starting point, the police will gather information about known crimes, interview witnesses, and obtain forensic evidence. Nowadays, there is also a fair amount of information available on social networks and the Internet, but the credibility of such sources requires careful verification. In fact, even well-verified facts can be interpreted in completely different ways, which can lead to erroneous exaggeration or underestimation of the problem under investigation.

We need to add meaning to the actions of the extremists so that we can explain what is really going on. We do this in the second phase of SBIA by constructing a better explanation of the actions that is consistent with the available evidence and understanding of the motives of the individuals involved. We see this process in every criminal court, when attorneys for the prosecution and defense offer their versions of the truth to the jury. For example, why are the accused's fingerprints on fragments of a beer bottle used to make a Molotov cocktail? Did he throw the bottle himself, or was the bottle taken from the dustbin of his house by a mob looking for materials to make weapons? The court is required to verify these facts, and then the jury must choose the explanation that they think best fits the available evidence. Facts rarely speak for themselves. At the second stage, in the case of an investigation of an attack by extremists, we must come to an understanding of the reasons that unite such people. We will understand what drives their anger and hatred. This will provide us with an explanatory model that will allow us to proceed to the third stage of WWII, in which we can assess how the situation may change over time - perhaps after a wave of arrests and successful prosecutions of extremist leaders by the police. We will also be able to assess how likely it is that arrests and convictions will lead to a reduction in the threat of violence and the anxiety of society as a whole. This third step provides the intelligence base for evidence-based policy decisions.

Facts rarely speak for themselves. At the second stage, in the case of an investigation of an attack by extremists, we must come to an understanding of the reasons that unite such people. We will understand what drives their anger and hatred. This will provide us with an explanatory model that will allow us to proceed to the third stage of WWII, in which we can assess how the situation may change over time - perhaps after a wave of arrests and successful prosecutions of extremist leaders by the police. We will also be able to assess how likely it is that arrests and convictions will lead to a reduction in the threat of violence and the anxiety of society as a whole. This third step provides the intelligence base for evidence-based policy decisions.

The SBIA methodology has a critical fourth component, the development of a strategic notification about events in the long term. For our example, we could consider the further growth of extremist movements elsewhere in Europe or the evolution of such groups in the event of major changes in the patterns of refugee movements as a result of new regional conflicts or due to climate change. This is just one example, but there are many other situations where anticipation of future events is of great importance, as it allows us to intelligently prepare for the future.

This is just one example, but there are many other situations where anticipation of future events is of great importance, as it allows us to intelligently prepare for the future.

The BOOB four-part methodology can be applied to any situation that concerns us, as long as we want to understand what happened and why, and what might happen next, from stressful situations at work to losing your sports team. The SBIA methodology is applicable to any situation where you have current information and want to make a decision about how best to act on it.

We should not be surprised to find patterns in the various types of errors inherent in working on each of the four components of the BOOB process. For example:

● Mastery of the situation depends on the difficulty of assessing what is happening at the moment. The presence of gaps in information is real and often causes a reluctance to change one's mind after receiving new facts.

● Our explanations suffer from a poor understanding of other people: their motivations, upbringing, culture and background.

● Estimates of the development of events can be thrown off by unexpected changes in situations that were not taken into account in the forecast.

● Strategic achievements are often overlooked due to being too narrowly focused and the analyst's lack of imagination about the future.

The four-part methodology for assessing a situation is applicable not only in public affairs. At its core, it contains a call for rationality in the entire course of our thinking. Our choice, even between unpleasant alternatives, will be more logical as a result of adopting methodical ways of thinking. Such ways of thinking contain the ability to distinguish what we know from what we don't know and from what we assume to be probable. This kind of thinking requires integrity.

In Buddhism there is a notion that there are three poisons that cripple the mind: anger, attachment and ignorance [9] . We must be aware that strong emotions, such as anger, can distort our perception of what is true and what is false. Attachment to old, comfortable ideas that give us hope that the world is predictable can make us blind to emergencies. This is what allows us to be taken by surprise. Still, ignorance is the most destructive poison for the mind. And the goal of intellectual analysis is to eliminate this ignorance and develop our ability to make intelligent decisions so that we can make better choices in everyday life.

Attachment to old, comfortable ideas that give us hope that the world is predictable can make us blind to emergencies. This is what allows us to be taken by surprise. Still, ignorance is the most destructive poison for the mind. And the goal of intellectual analysis is to eliminate this ignorance and develop our ability to make intelligent decisions so that we can make better choices in everyday life.

On that fateful day in March 1982, Margaret Thatcher immediately realized what the intelligence was telling her. She understood what the Argentine junta was planning and what the possible consequences of these plans for her as British Prime Minister. Her words demonstrated the ability to use this understanding: “I must contact President Reagan immediately. Only he can convince Galtieri [General Leopoldo Galtieri, leader of the junta] to stop this madness.” I was authorized to ensure that the latest intelligence from the Government Communications Center was passed on to the American authorities, including the presidential administration. The British government quickly prepared a personal message from Thatcher to Reagan, asking him to speak with Galtieri and obtain confirmation that he would not give permission for Argentine landings in the Falklands, let alone military action, and a warning that the UK would not turn a blind eye to such an invasion. . But the Argentine junta ignored Reagan's request for talks with Galtieri and did nothing about it until the invasion could no longer be cancelled.

The British government quickly prepared a personal message from Thatcher to Reagan, asking him to speak with Galtieri and obtain confirmation that he would not give permission for Argentine landings in the Falklands, let alone military action, and a warning that the UK would not turn a blind eye to such an invasion. . But the Argentine junta ignored Reagan's request for talks with Galtieri and did nothing about it until the invasion could no longer be cancelled.

But the full-scale Argentine invasion and military occupation of the islands took place only two days later, on April 2, 1982. There was only a small detachment of the Royal Marines on the islands, and only the lightly armed ice reconnaissance ship Endurance operated in their area. Effective resistance to the enemy was impossible. The islands were too far away for naval reinforcements to arrive within two days, and the only airport did not have a runway capable of receiving long-range military transport aircraft.

We lacked adequate knowledge of the situation in terms of our intelligence's knowledge of the plans of the Argentine junta. We failed to understand the facts at our disposal, and therefore could not predict how events would develop. Moreover, over the years we have not been able to get strategic notice that such a situation could ever arise, and therefore we have not taken steps that could have prevented an Argentine invasion of the Falklands. These were failures at each of the four stages of the BOOV methodology.

We failed to understand the facts at our disposal, and therefore could not predict how events would develop. Moreover, over the years we have not been able to get strategic notice that such a situation could ever arise, and therefore we have not taken steps that could have prevented an Argentine invasion of the Falklands. These were failures at each of the four stages of the BOOV methodology.

All lessons to be learned.

Structure of this book

The four chapters of the first part of this book are devoted to the above-mentioned BOIA methodology. Chapter 1 describes how we can take control of the situation and check our sources of information. Chapter 2 is about causation and the interpretation of a situation, and how a mathematical technique called Bayesian inference allows us to use new information to change the degree of confidence in our chosen hypothesis. Chapter 3 explains the process of generating estimates and forecasts. Chapter 4 describes the long-term benefit of strategic event notification.

There are lessons to be learned from these four stages of analysis:

1. 1 Jerome K. Jerome. Should we say what we think and think what we say? // Selected works in 2 volumes. - M .: GIHL, 1957. - T. 2.

2. 2 The history of these radio interceptions and the decision to set up a task force to recapture the Falklands is detailed in the official history of the Falklands Campaign by Sir Lawrence Freedman and in the memoirs of Sir John Knott and Admiral Sir Henry Leach, First Sea Lord of the time. Lawrence Freedman. The Official History of the Falklands Campaign, vol. 1. London, Routledge, 2005, ch. 19. John Nott. Here Today, Gone Tomorrow. London, Politico, 2002. Henry Leach. Endure No Makeshifts. London, Pen and Ink Books, 1993.

3. 3 One of the best summaries of the nature and use of classified intelligence is found in Chapter 1 of the Butler report on intelligence failures prior to the 2003 invasion of Iraq. This was written by Investigative Advisor, the late Peter Freeman, my former senior colleague at the UK Government Communications Centre. Robin Butler. Review of Intelligence on Weapons of Mass Destruction. London, HMSO, 2004, ch. 1

Robin Butler. Review of Intelligence on Weapons of Mass Destruction. London, HMSO, 2004, ch. 1

4.4 In the official language of the Joint Intelligence Committee, it is "the process of obtaining known information about situations and objects of strategic, operational or tactical significance and characterizing known and future actions in such situations."

5.5 The ethics of secret intelligence is the subject of a dialogue between political scientist Professor Mark Fithian and myself, as a former practitioner, in our book below. David Omand, Mark Phythian. Principled Spying. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2018.

6.6 In psychology, a specific personality trait is studied, which characterizes the ability of a person to endure ignorance of important life circumstances without suffering and anxiety - tolerance for uncertainty. – Hereinafter, except for specially noted footnotes, approx. scientific ed.

7.7 I am using the term "negative capacity" here in the sense that the 20th-century British psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion coined Keats's term to illustrate the attitude of openness of mind and the ability to dwell in uncertainty, which he considered central not only to the psychoanalytic session, but also to in life itself. Diana Voller. "Negative Capability". Contemporary Psychotherapy, vol. 2, no. 2, 2010.

Diana Voller. "Negative Capability". Contemporary Psychotherapy, vol. 2, no. 2, 2010.

8.8 A description of the problems faced by British intelligence at that time can be found in the two books below. Richard Aldrich. GCHQ. London, Harper Press, 2010, ch. 24. John Ferris. Behind The Enigma. London, Bloomsbury, 2020.

9.9 Ringu Tulku Rinpoche. Living without Fear and Anger. Oxford, Bodhicharya, 2005.

Dolch Word List

Not to be confused with Dutch Word List.

B Dolch Word List is a list of commonly used English words (also known as target words) compiled by Edward William Dolch, the main proponent of the "whole word" method of starting reading instructions. The list was first published in a journal article at 1936 year. [1] and then published in his book Problems with reading in 1948 [2]

Dolch compiled a list based on children's books of his era, so nouns like "kitten" and "Santa Claus , appear in the list in place of more common words. The list contains 220 "functional words" that Dolch believes should be easy to recognize in order to achieve fluent reading in English. The collection excludes nouns, which make up a separate list of 95 words. According to Dolch, between 50% and 75% of all words used in school textbooks, library books, newspapers, and magazines are part of Dolch's core language. target word vocabulary; However, keep in mind that he compiled this list in 1936.

The list contains 220 "functional words" that Dolch believes should be easy to recognize in order to achieve fluent reading in English. The collection excludes nouns, which make up a separate list of 95 words. According to Dolch, between 50% and 75% of all words used in school textbooks, library books, newspapers, and magazines are part of Dolch's core language. target word vocabulary; However, keep in mind that he compiled this list in 1936.

Contents

- 1 Critics

- 2 Learning strategies

- 3 Dolch list: Nouns

- 4 Dolch list: Nouns

- 6 See also 60 260 6 Recommendations 60260 60261

- 7 external link

Critics

Critics of learning to read with the whole world and the whole language methods (and proponents of phonics) argue that memorizing whole words can do more harm than good because it takes time from the important aspect of the practice of basic decoding methods. [3]

The cognitive neuroscientist, Stanislas Dehaene, writes: "Cognitive psychology directly refutes any notion of learning by a 'global' or 'whole language' method. " He goes on to talk about the "whole-word-reading myth" (also: visual words), saying that it has been debunked by recent experiments. "We don't recognize a printed word through a holistic perception of its contours, because our brain breaks it down into letters and graphemes." [4] Cognitive neuroscientist, Mark Seidenberg, says that "the tenacity of whole language ideas, despite the mass of evidence against them, is most striking at this stage", and further describes it as a "theoretical zombie" because it persists despite for lack of supporting evidence. [5] In addition, according to research, memorizing a whole word is "time consuming", requiring an average of about 35 attempts per word. [6]

" He goes on to talk about the "whole-word-reading myth" (also: visual words), saying that it has been debunked by recent experiments. "We don't recognize a printed word through a holistic perception of its contours, because our brain breaks it down into letters and graphemes." [4] Cognitive neuroscientist, Mark Seidenberg, says that "the tenacity of whole language ideas, despite the mass of evidence against them, is most striking at this stage", and further describes it as a "theoretical zombie" because it persists despite for lack of supporting evidence. [5] In addition, according to research, memorizing a whole word is "time consuming", requiring an average of about 35 attempts per word. [6]

Learning strategies

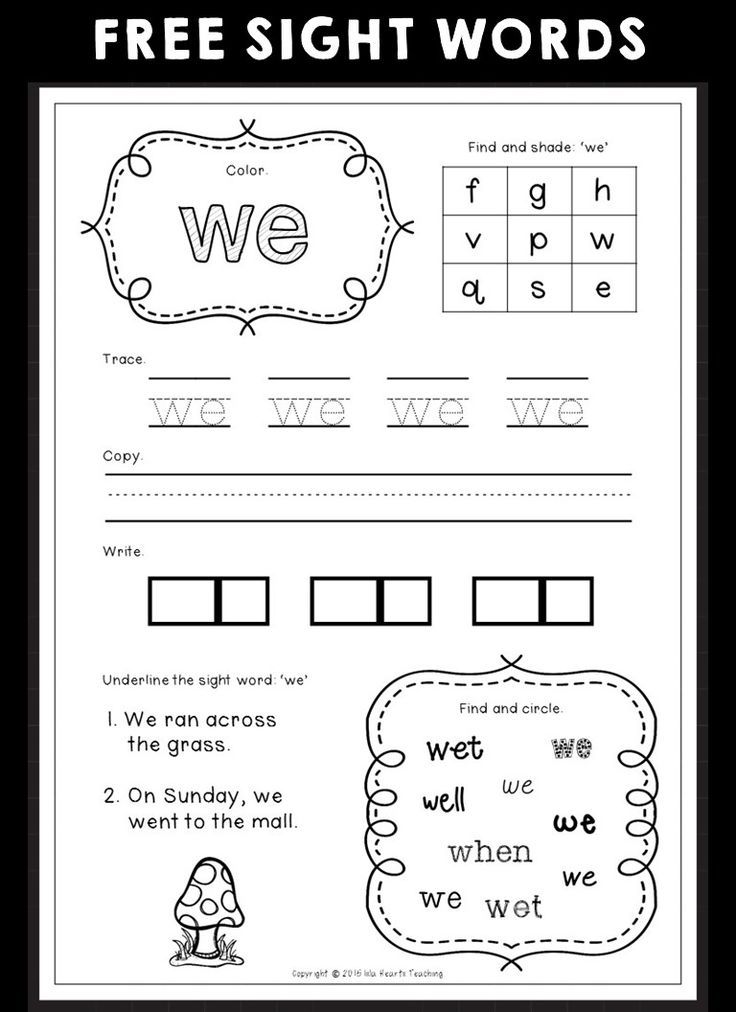

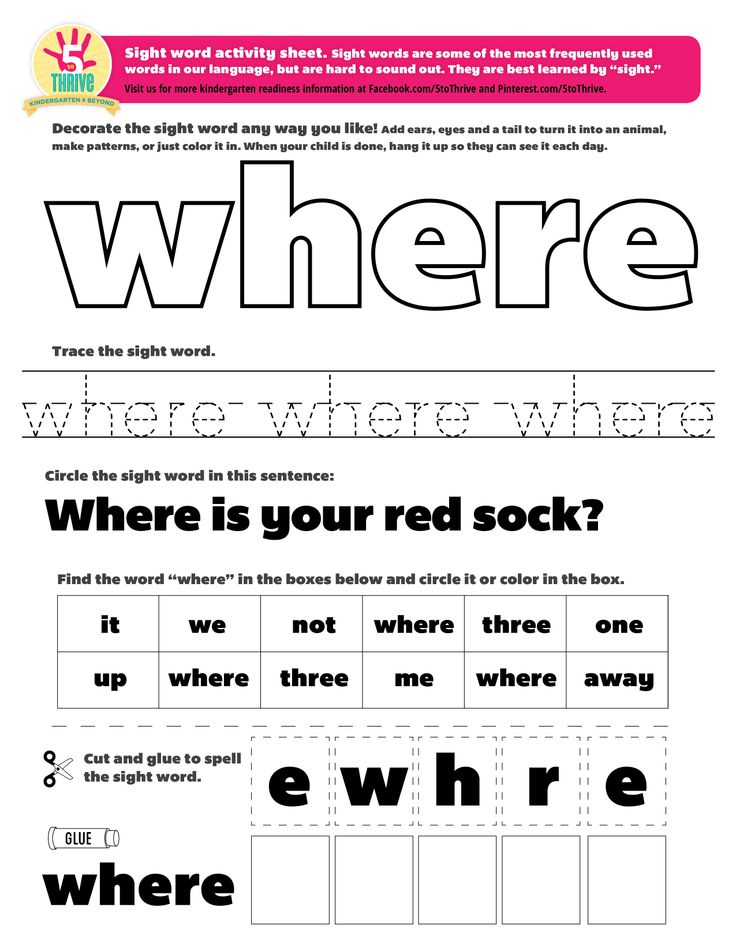

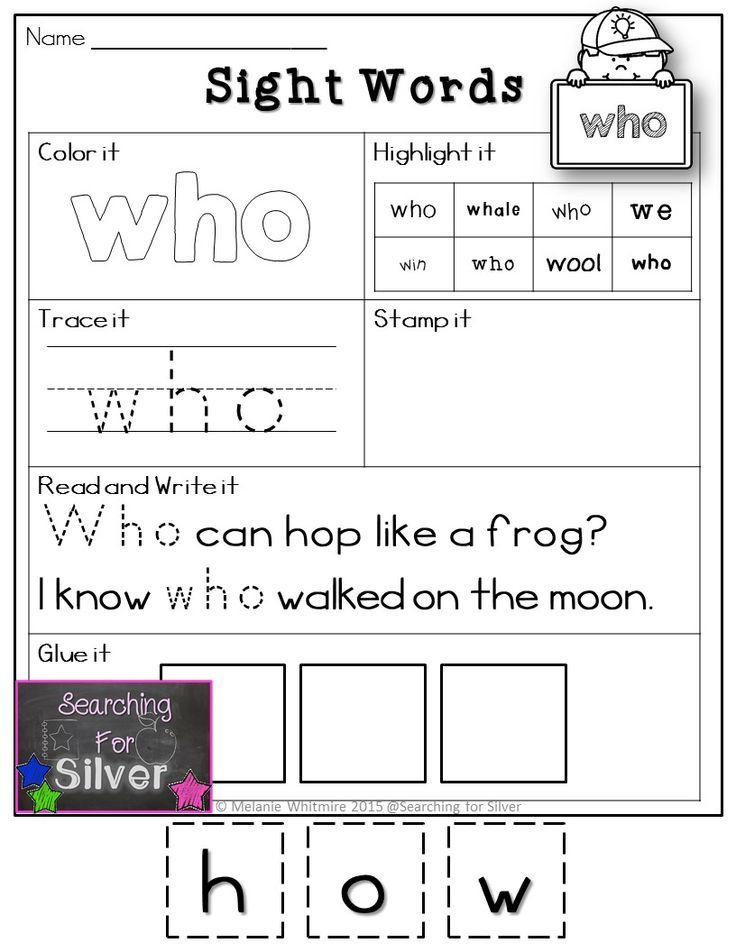

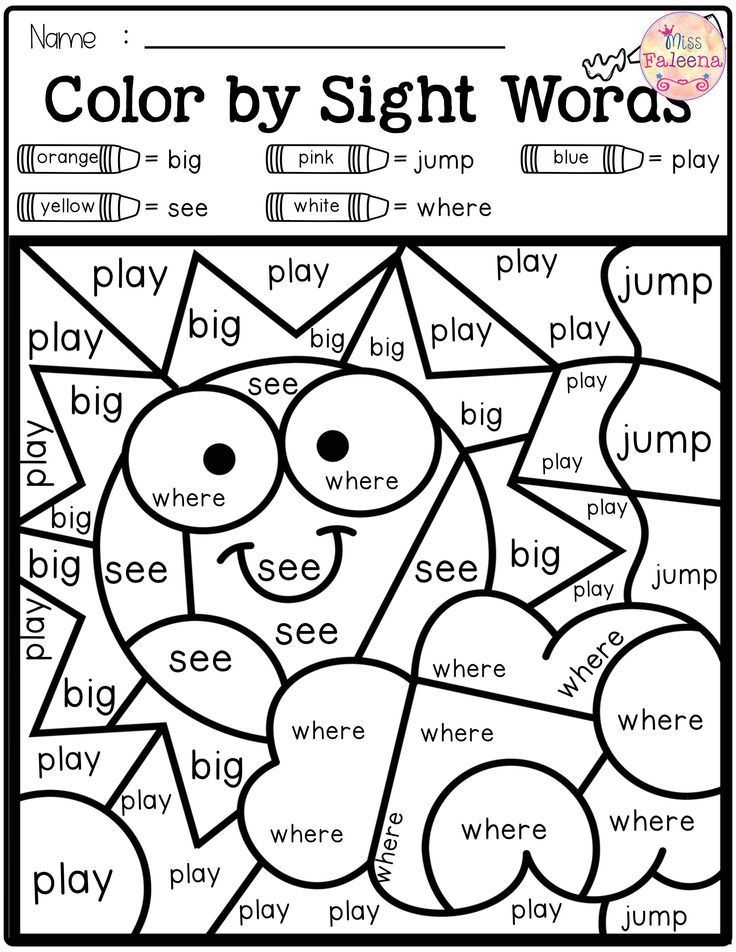

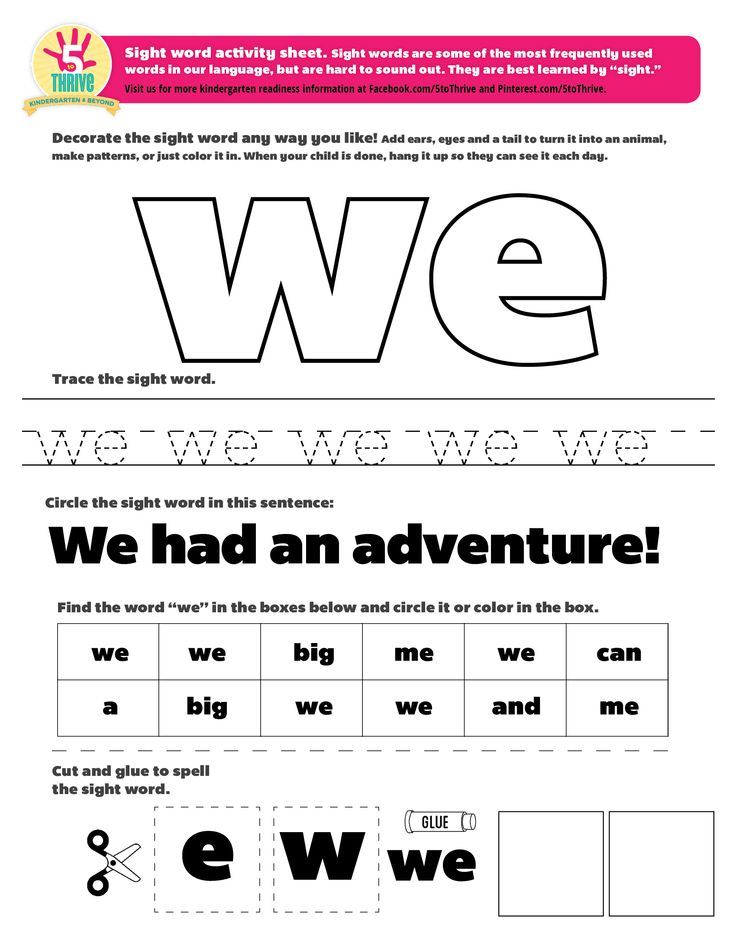

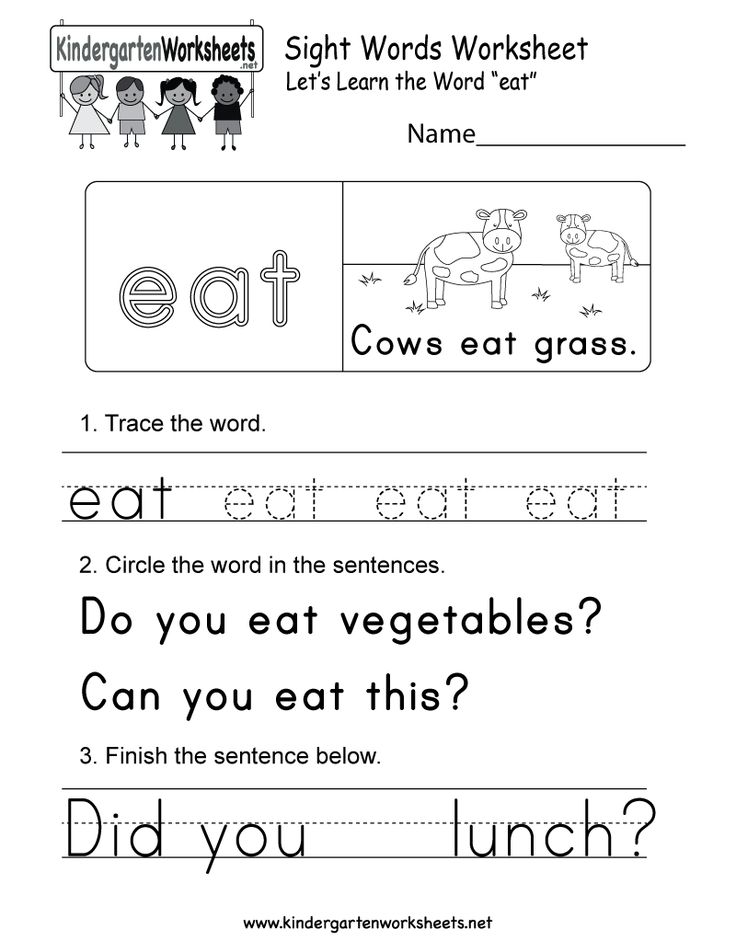

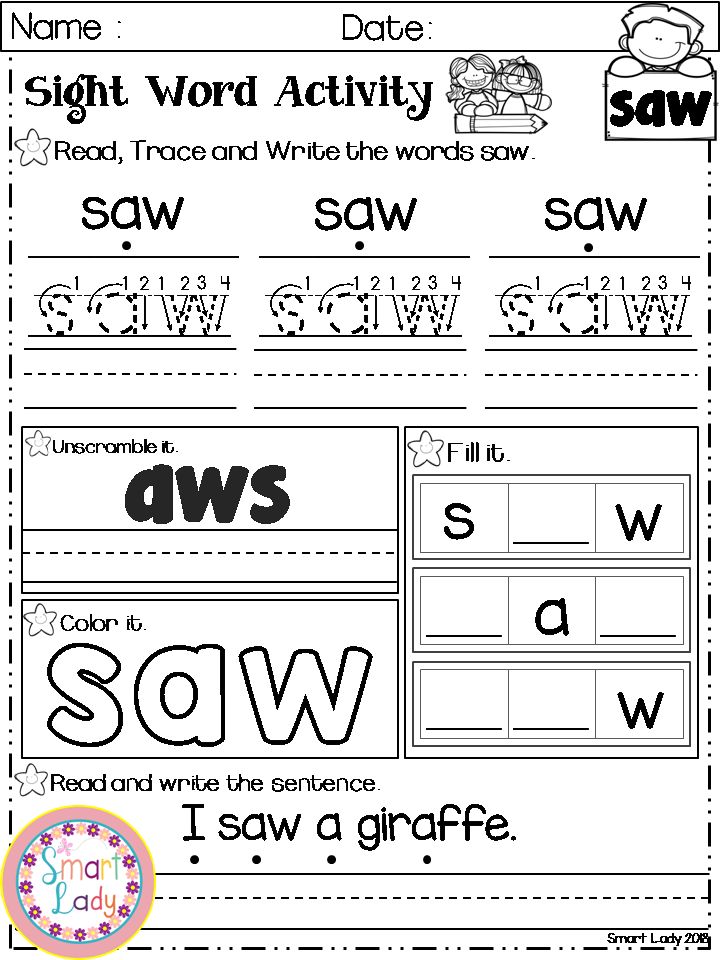

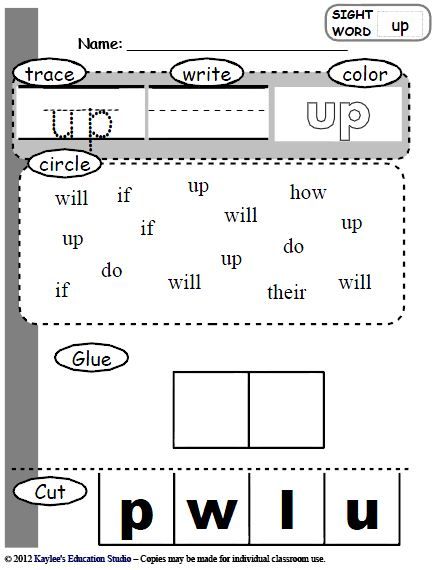

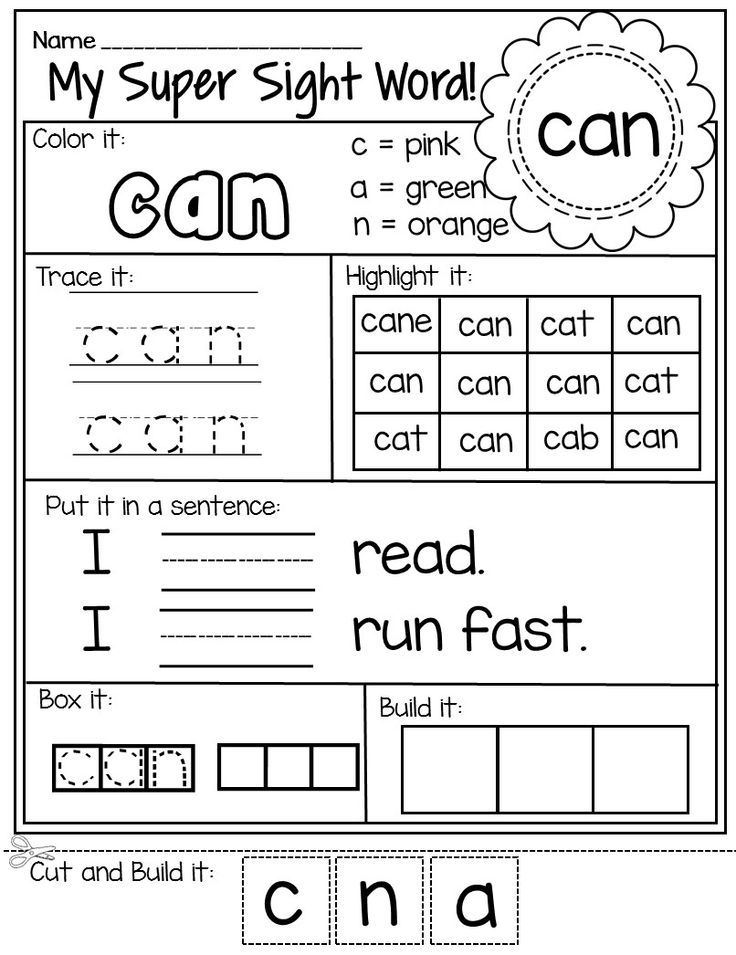

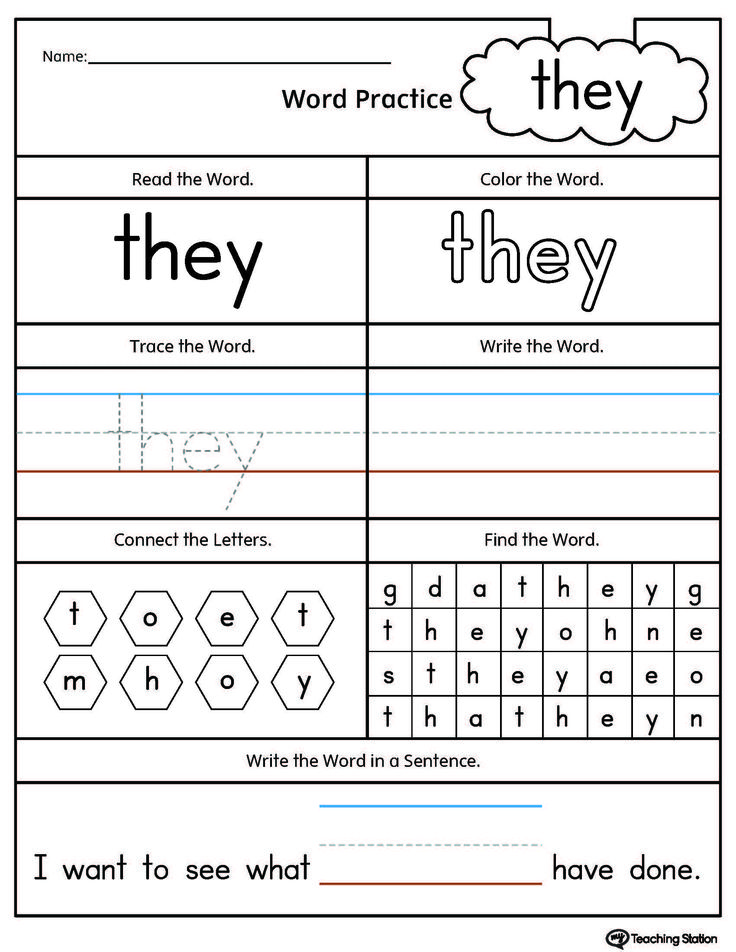

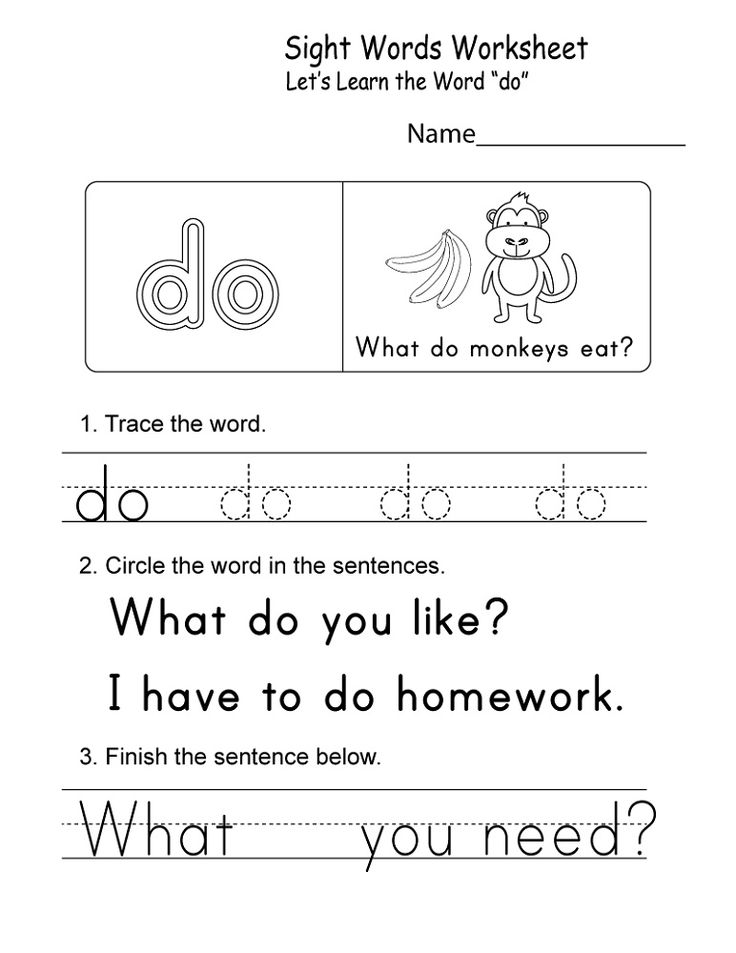

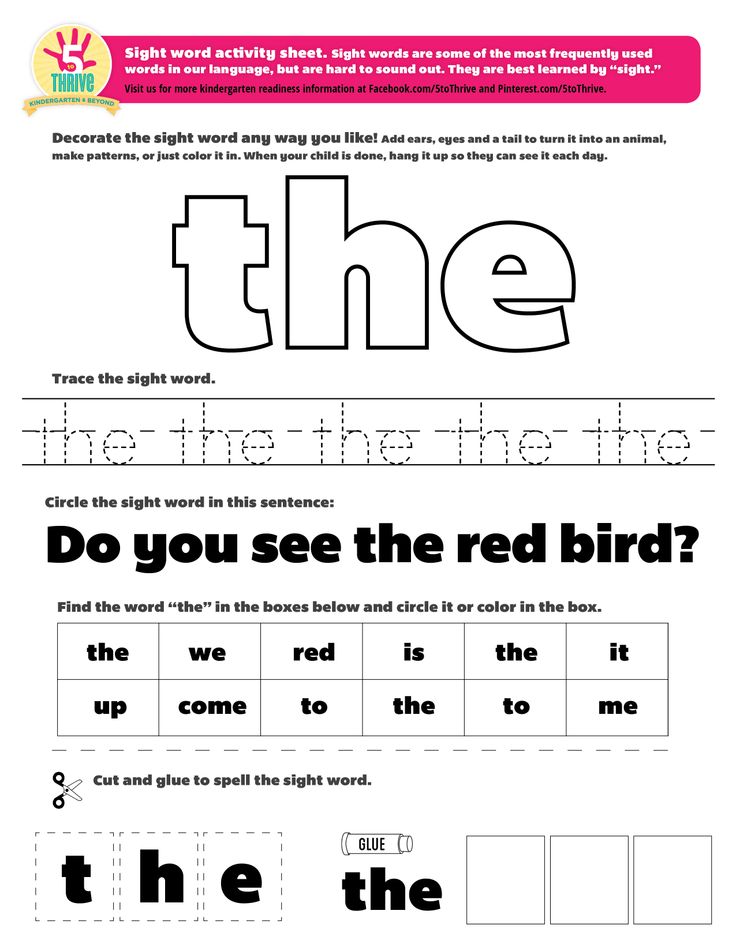

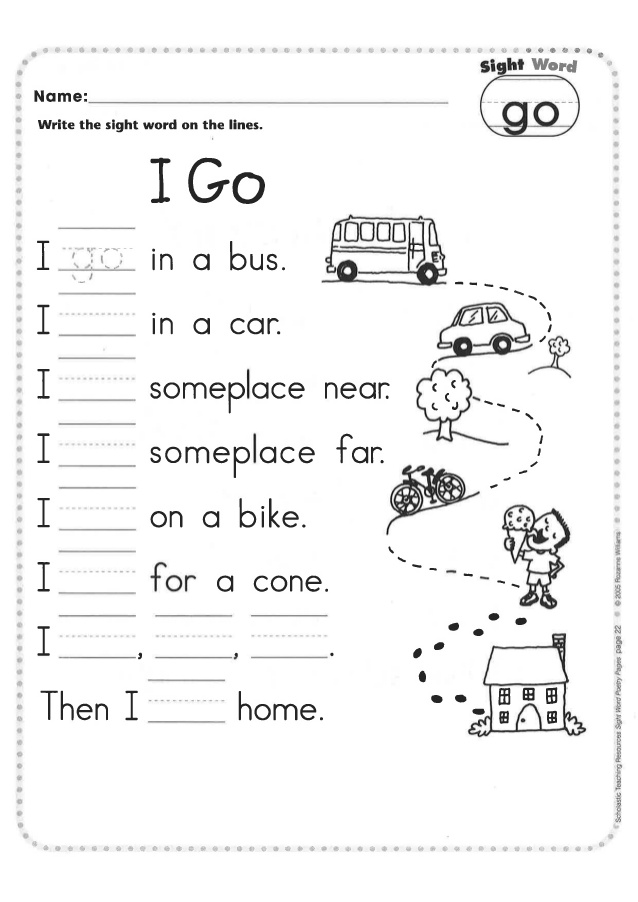

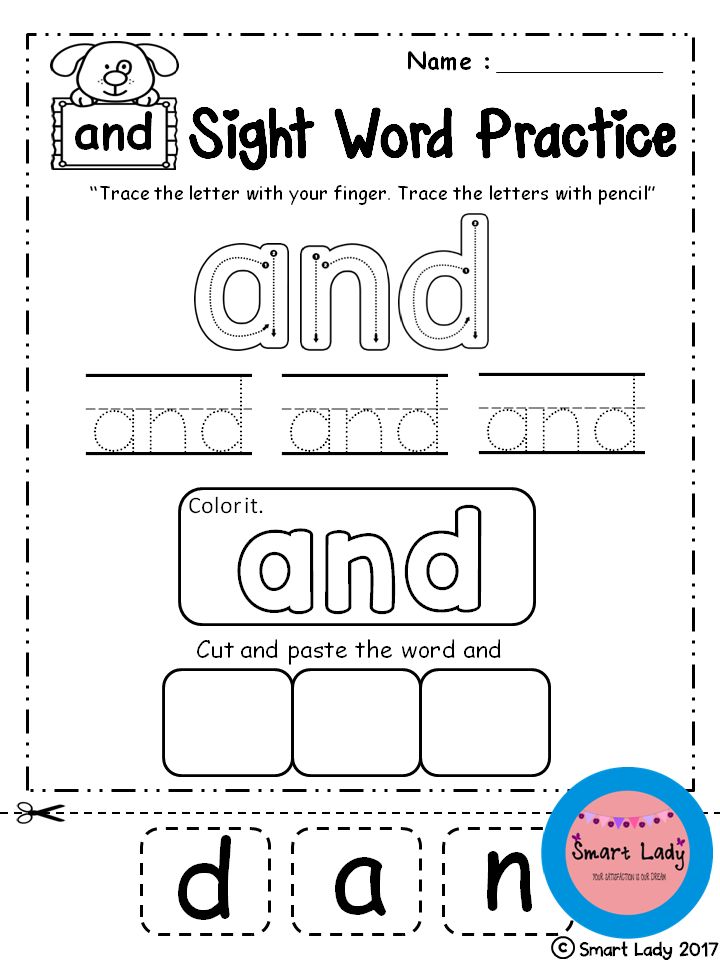

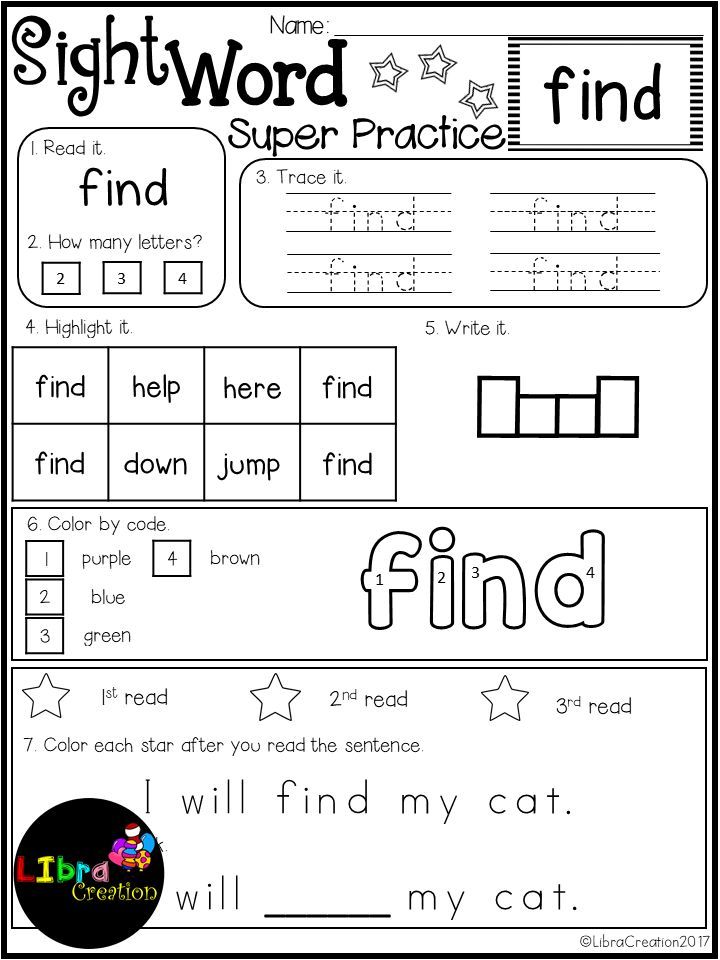

These word lists are still meant to be memorized in elementary schools in America and other countries. Although most of Dolch's 220 words are phonetic, children are sometimes told that they cannot be "voiced" using the usual letter designation. acoustic patterns and must be studied by sight; hence the alternative term "target word". The list is divided by Educational stage, in which the children were expected to memorize these words.

acoustic patterns and must be studied by sight; hence the alternative term "target word". The list is divided by Educational stage, in which the children were expected to memorize these words.

Some educators say that the Dolch list can be useful if teachers no teach children to memorize them; instead, they learn words using an explicit, systematic phonics approach, perhaps using a tool such as Elkonin's Boxes. [7]

Some educators prefer to use the "Instant 1000 Words" list prepared in 1979 by Edward Fry, professor of education and director of the Reading Center at Rutgers University and Loyola University in Los Angeles. [8]

Dolch list: Non-nouns

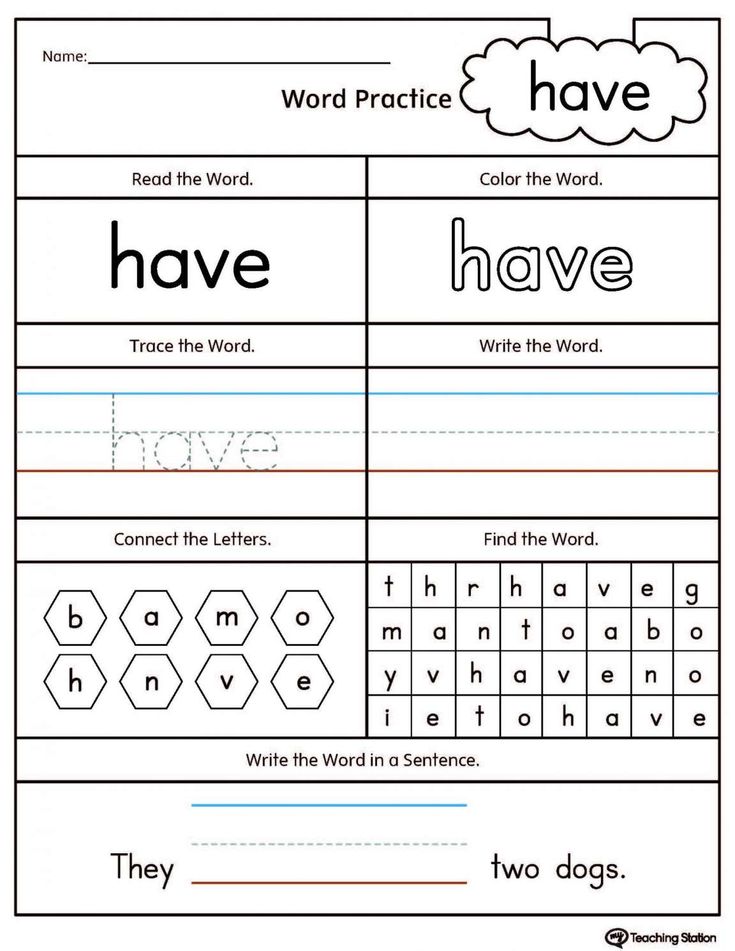

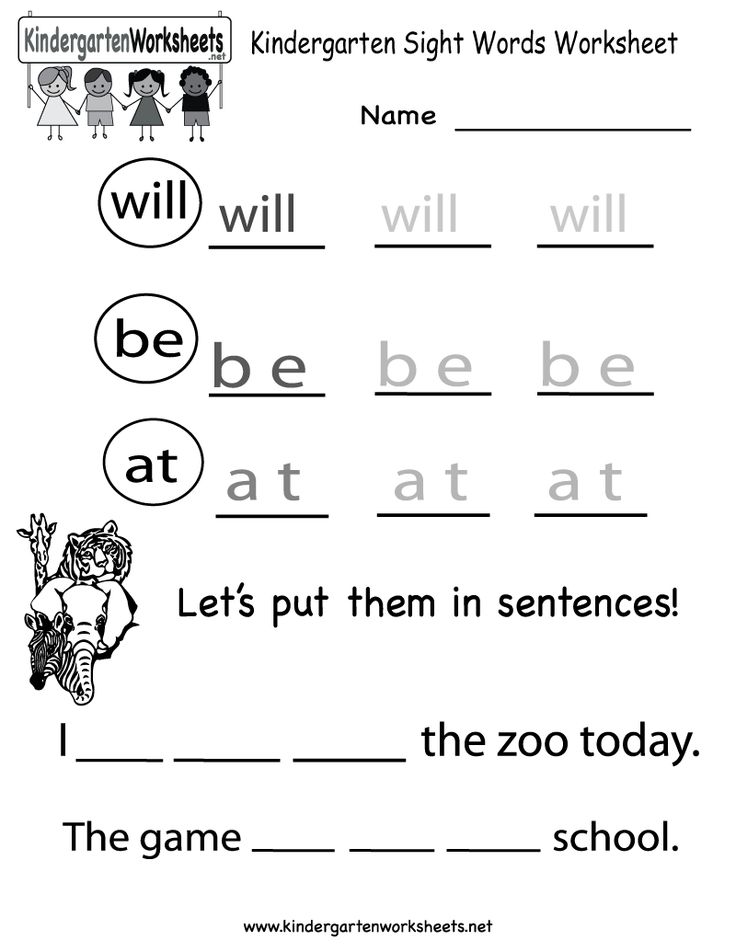

Preprimer : (40 words) a, and, away, big, blue, maybe, come, down, find, for, funny, go, help, here, me, in, this, jump, small, look , do, me, mine, not, one, play, red, run, said, look, three, before, two, up, we, where, yellow, you

Primer : (52 words) all, am, are, at, ate, be, black, brown, but, come, did, do, eat, four, get, good, have, he, into, like, must, new, no, now, further, ours, out, please, pretty, ran, rode, saw, tell me, she, so, soon, here, they, this is also under, they want, it was, well, let's go, what, white, who, will, with, yes

Grade 1 : (41 words) after, again, en, anyone, how, ask, past, could, each, fly, from, give, give, had, has, her, him, him, how, simply , know, give, live, maybe, from, old, once, open, over, put, round, some, stop, take, thank, them, then, think, pass, were, when

2nd class : (46 words) always, around, because, was, before, the best, both, buy, call, cold, do, don't, quickly, first, five, found, gave, goes, green, him, did , a lot, off, or, pull, read, correctly, sing, sit, sleep, tell, them, these, those, on, us, use, very, erase, what, why, wish, work, will, write, your

Grade 3 : (41 words) oh, better, bring, take away, clean, cut, ready, draw, drink, eight, fall, far, full, got, grow, hold, hot, hurt, if, hold , kind, laughter, light, long, many, I, never, only, own, choose, seven, will, show, six, small, start, ten, today, together, try, warmly

Dolch List: Nouns

(95 words) apple, child, back, ball, bear, bed, bell, bird, birthday, boat, box, boy, bread, brother, cake, car, cat, chair, chicken, kids, christmas, coat, corn , cow, day, dog, doll, door, duck, egg, eye, farm, farmer, father, legs, fire, fish, floor, flower, game, garden, girl, goodbye, grass, earth, hand, head, hill, home, horse, house, kitty, leg, writing, person, people, milk, money, morning, mother, name, nest, night, paper, party, painting, pig, rabbit, rain, ring, robin, santa Claus, school, seed, sheep, shoe, sister, snow, song, squirrel, stick, street, sun, table, thing, time, up, toy, tree, watch, water, way, wind, window, wood 9 Seidenberg, Mark (2017).

Learn more