How many syllables are in even

Six Syllable Types | Reading Rockets

By: Louisa Moats, Carol Tolman

Six written syllable-spelling conventions are used in English spelling. These were regularized by Noah Webster to justify his 1806 dictionary's division of syllables. The conventions are useful to teach because they help students remember when to double letters in spelling and how to pronounce the vowels in new words. The conventions also help teachers organize decoding and spelling instruction.

Warm-up: Why double?

Read this fascinating tale. As you read, underline words in which there are two or more consonants between the first and second syllables.

Thunker's pet cats, Pete and Kate, enjoyed dining on dinner. They were fated to fatness. The pet Pete, who was cuter than Kate, was a cutter cat with sharp claws and teeth, scary scars, and one jagged ear.

Pete was ripping up ripening apples and biting bitter strips of striped bug bits as he stared into the starry night.

The cat Kate was not as scared or scarred. Kate liked licking slimy slops that slopped from a bucket, sitting at a site that sloped and caused the slop to slide. Kate liked sitting at the site where the slops slid.

— Created by Bruce Rosow (Moats & Rosow, 2003)

What do you notice about the vowel sounds that come before the doubled consonants?

Why teach syllables?

Without a strategy for chunking longer words into manageable parts, students may look at a longer word and simply resort to guessing what it is — or altogether skipping it. Familiarity with syllable-spelling conventions helps readers know whether a vowel is long, short, a diphthong, r-controlled, or whether endings have been added. Familiarity with syllable patterns helps students to read longer words accurately and fluently and to solve spelling problems — although knowledge of syllables alone is not sufficient for being a good speller.

Spoken and written syllables are different

Say these word pairs aloud and listen to where the syllable breaks occur:

bridle – riddle table – tatter even – ever

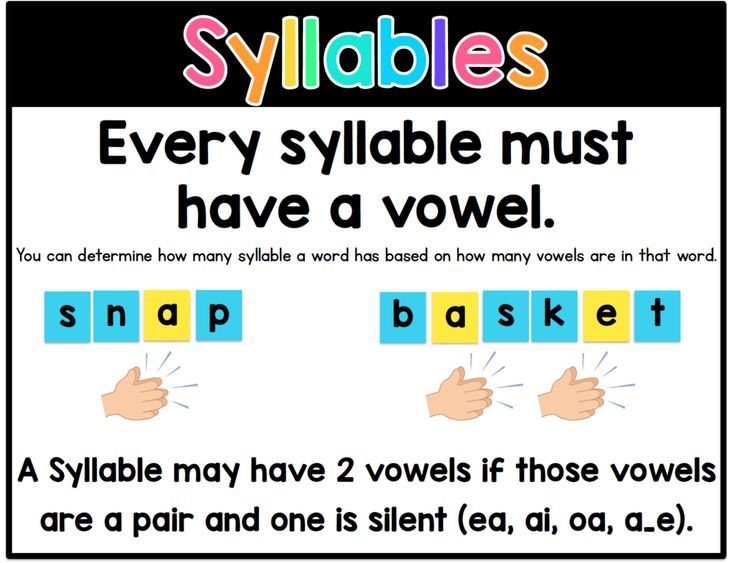

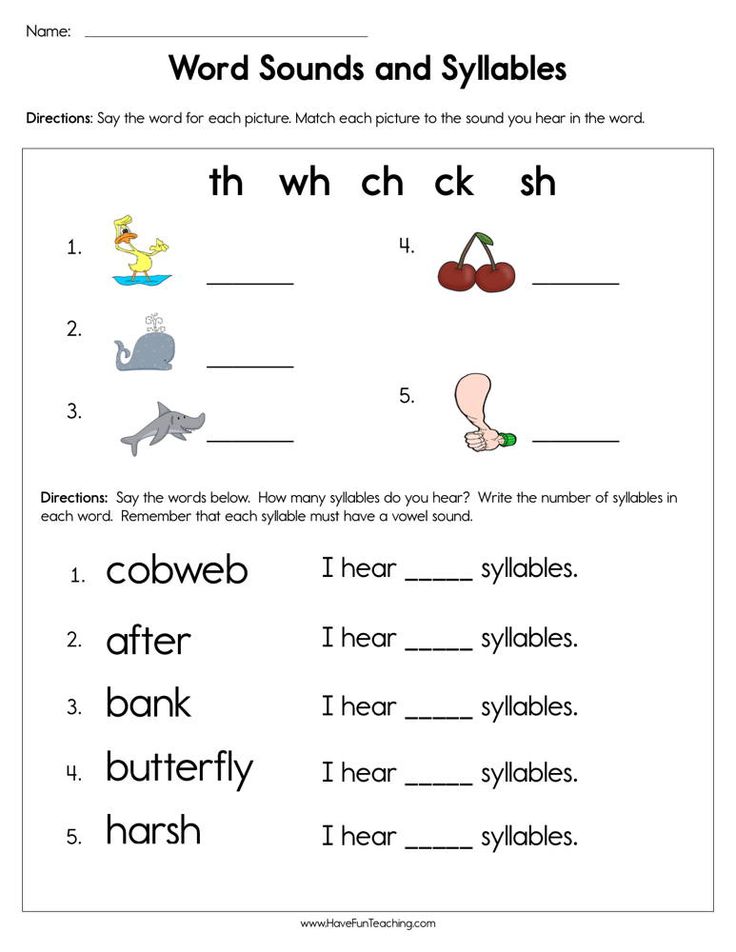

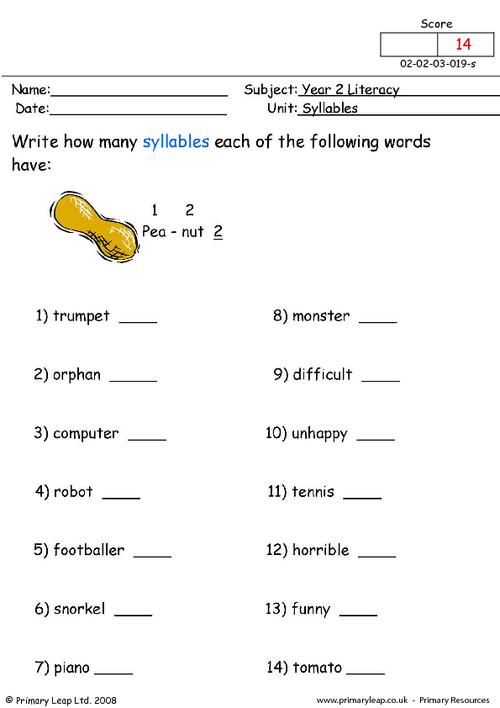

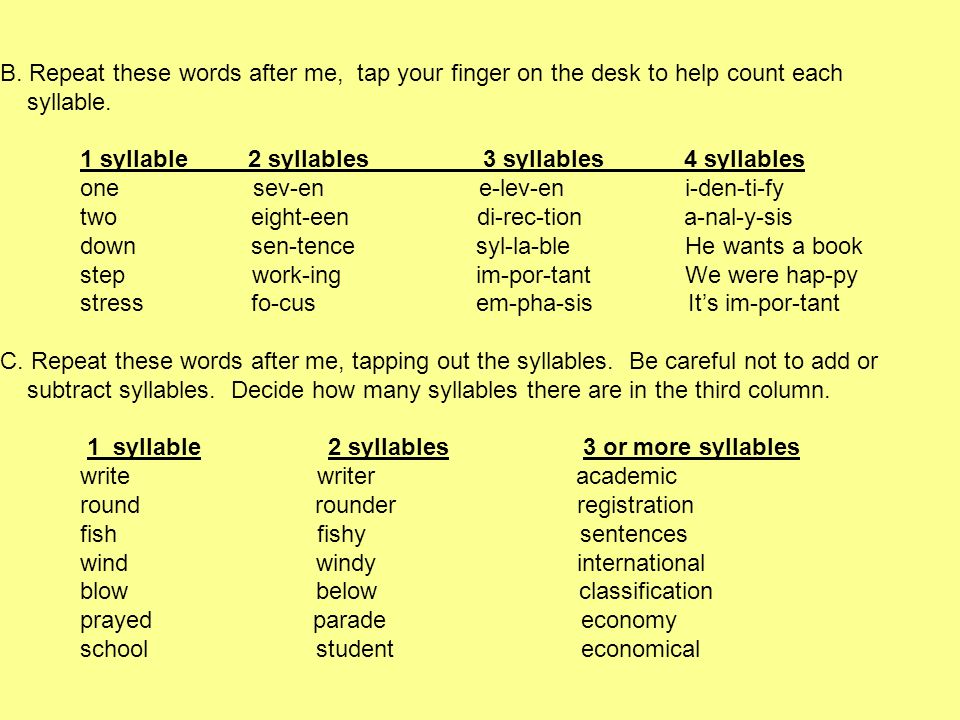

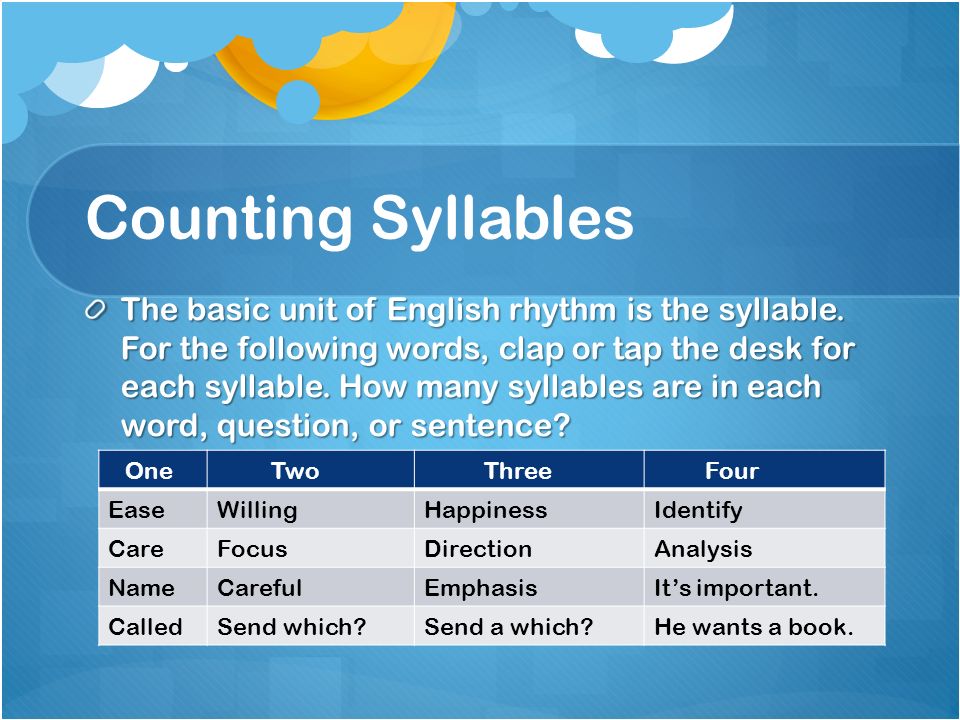

Spoken syllables are organized around a vowel sound. Each word above has two syllables. The jaw drops open when a vowel in a syllable is spoken. Syllables can be counted by putting your hand under your chin and feeling the number of times the jaw drops for a vowel sound.

Each word above has two syllables. The jaw drops open when a vowel in a syllable is spoken. Syllables can be counted by putting your hand under your chin and feeling the number of times the jaw drops for a vowel sound.

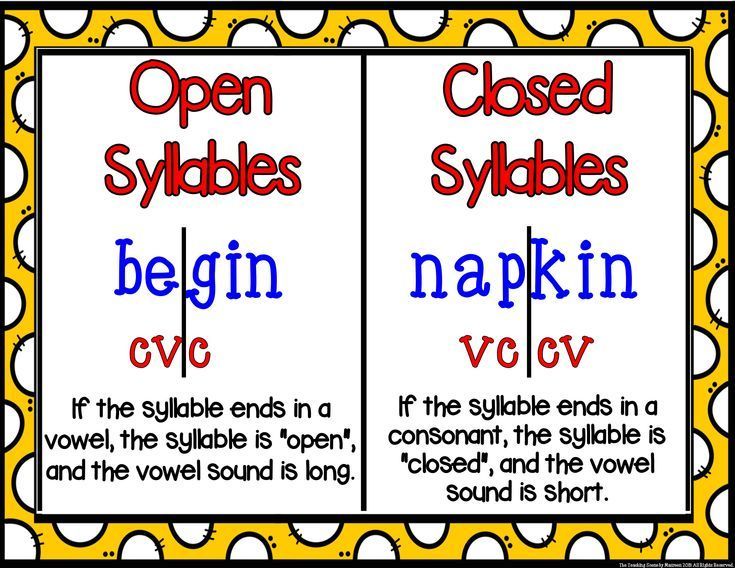

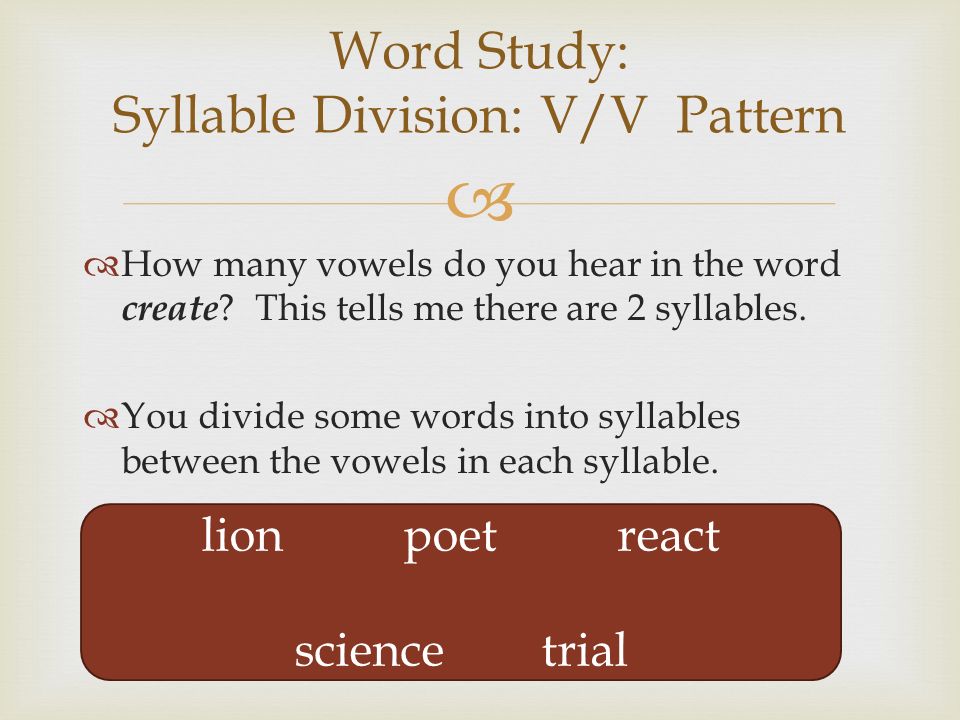

Spoken syllable divisions often do not coincide with or give the rationale for the conventions of written syllables. In the first word pair above, you may naturally divide the spoken syllables of bridle between bri and dle and the spoken syllables of riddle between ri and ddle. Nevertheless, the syllable rid is "closed" because it has a short vowel; therefore, it must end with consonant. The first syllable bri is "open," because the syllable ends with a long vowel sound. The result of the syllable-combining process leaves a double

d in riddle (a closed syllable plus consonant-le) but not in bridle (open syllable plus consonant-le). These spelling conventions are among many that were invented to help readers decide how to pronounce and spell a printed word.

These spelling conventions are among many that were invented to help readers decide how to pronounce and spell a printed word.

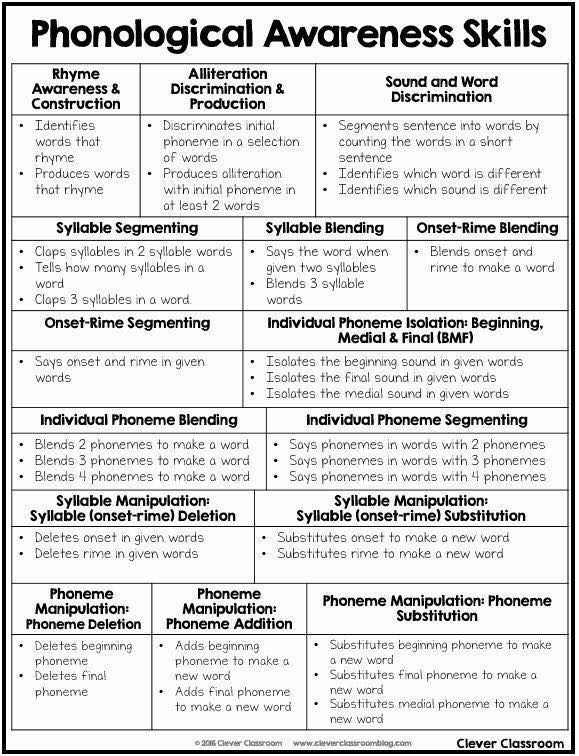

The hourglass illustrates the chronology or sequence in which students learn about both spoken and written syllables. Segmenting and blending spoken syllables is an early phonological awareness skill; reading syllable patterns is a more advanced decoding skill, reliant on student mastery of phoneme awareness and phoneme-grapheme correspondences.

Figure 5.1. Hourglass Depiction of the Relationship Between Awareness in Oral Language and Written Syllable Decoding

(Contributed by Carol Tolman, and used with permission.)

Click to see full image

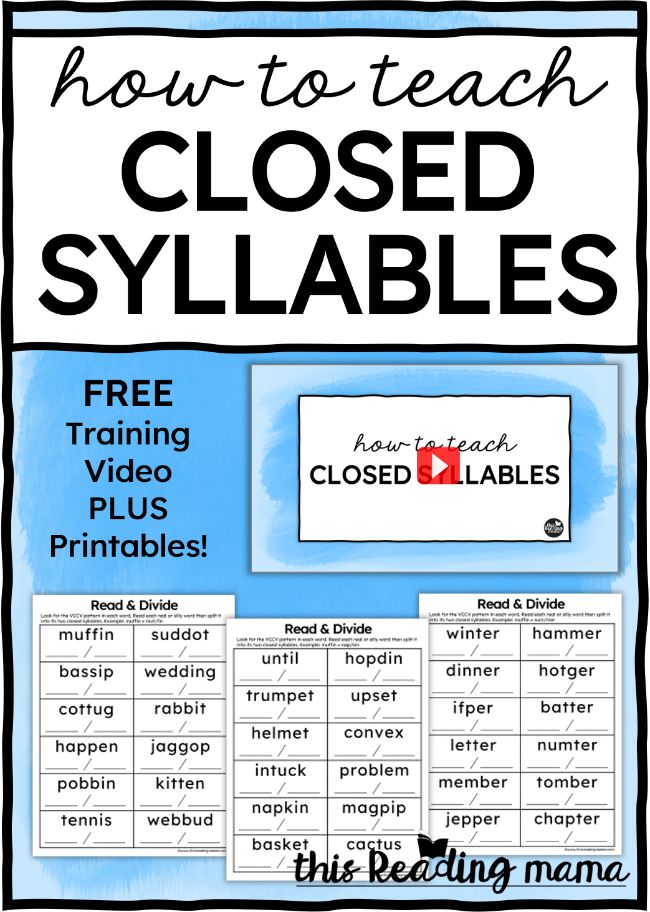

Closed syllables

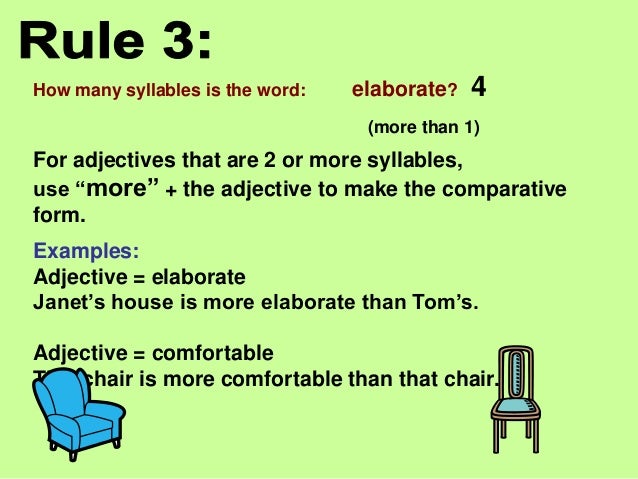

The closed syllable is the most common spelling unit in English; it accounts for just under 50 percent of the syllables in running text. When the vowel of a syllable is short, the syllable will be closed off by one or more consonants. Therefore, if a closed syllable is connected to another syllable that begins with a consonant, two consonant letters will come between the syllables (com-mon, but-ter).

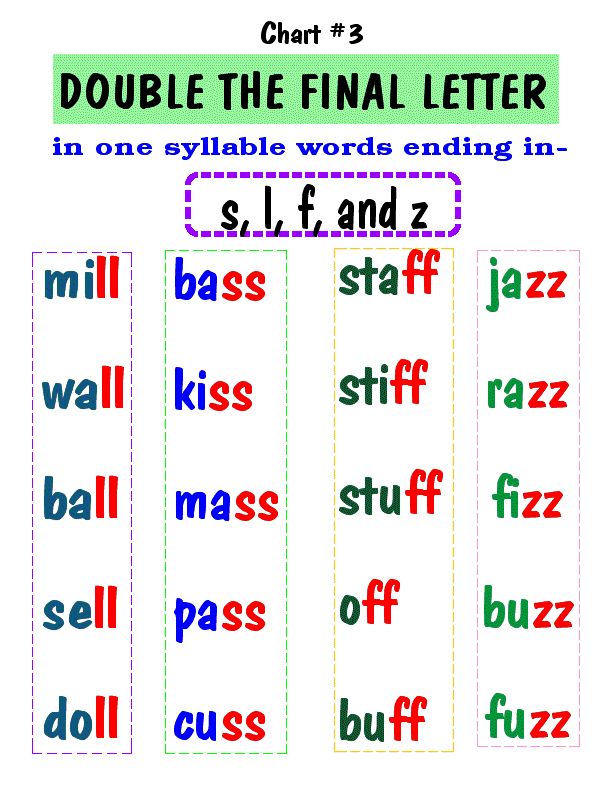

Two or more consonant letters often follow short vowels in closed syllables (dodge, stretch, back, stuff, doll, mess, jazz). This is a spelling convention; the extra letters do not represent extra sounds. Each of these example words has only one consonant phoneme at the end of the word. The letters give the short vowel extra protection against the unwanted influence of vowel suffixes (backing; stuffed; messy).

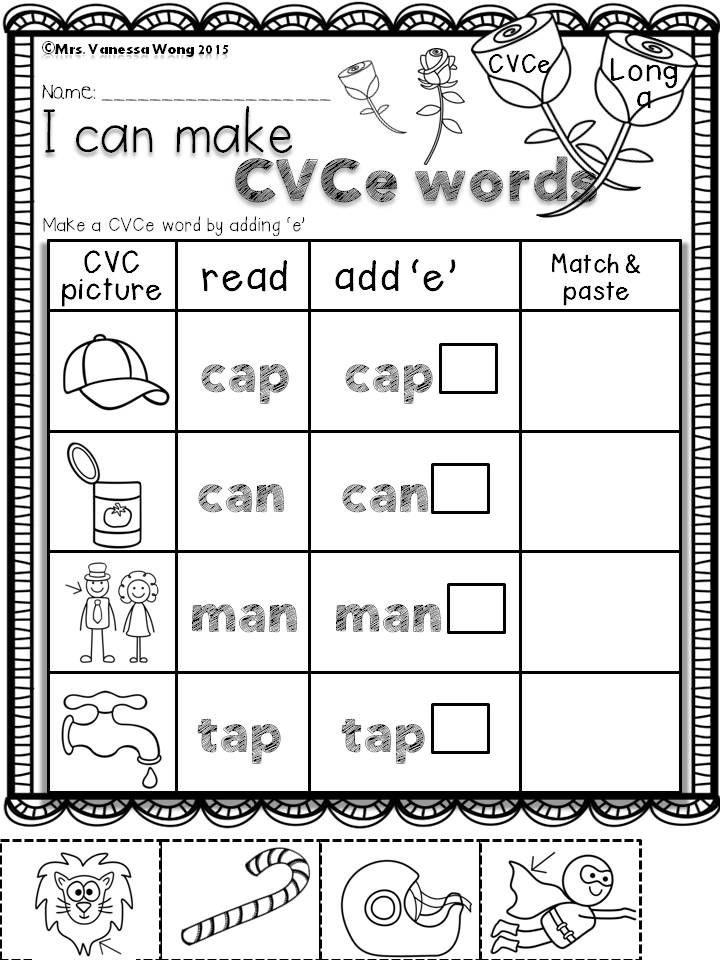

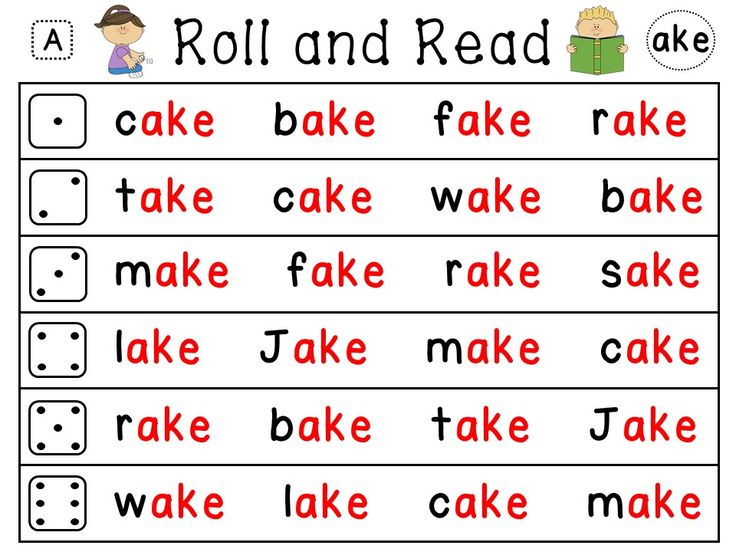

Vowel-Consonant-e (VCe) syllables

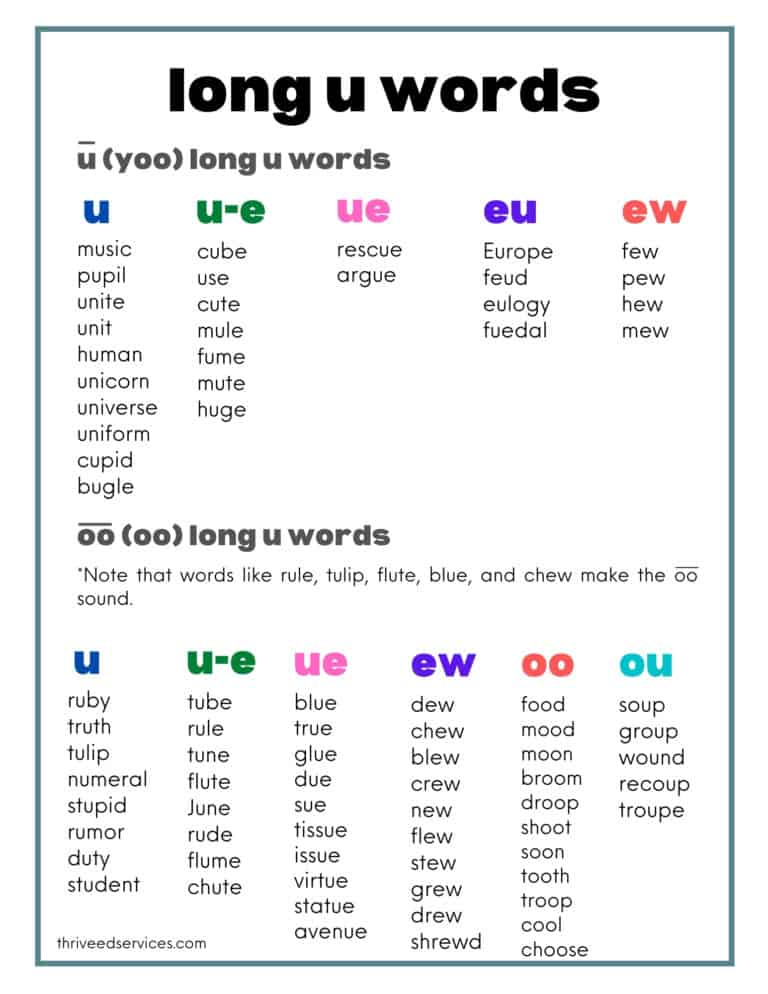

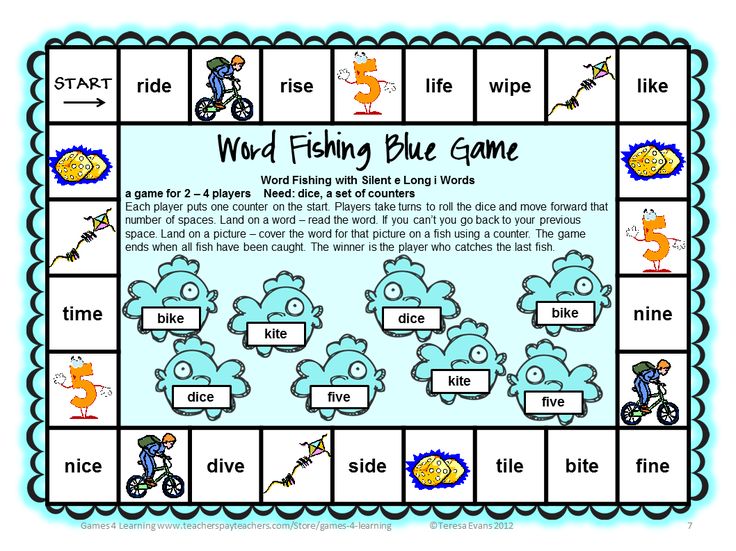

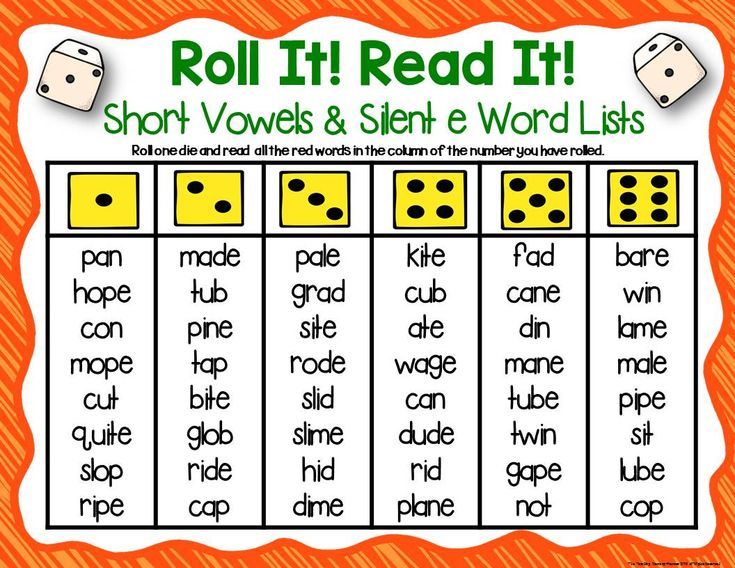

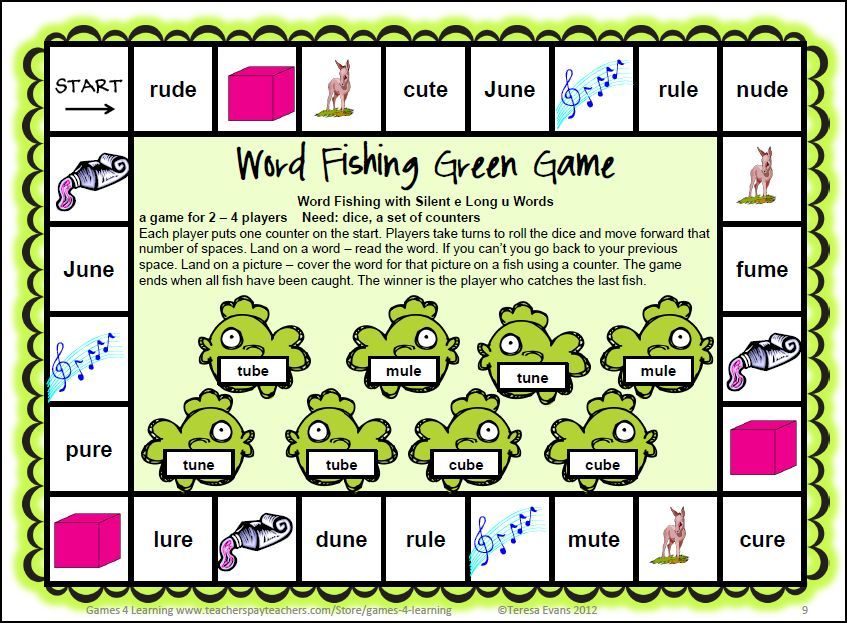

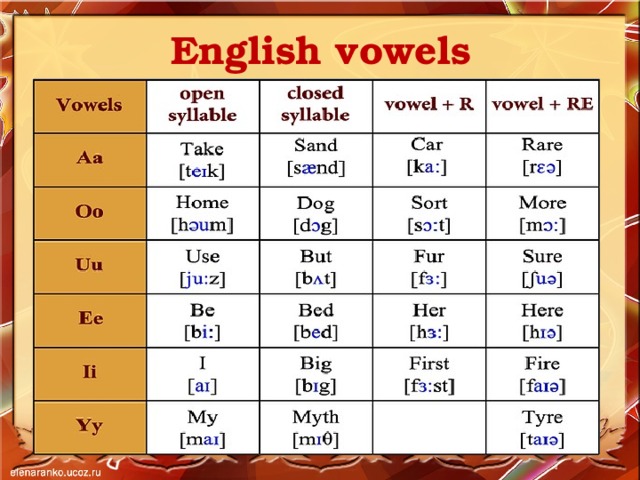

Also known as "magic e" syllable patterns, VCe syllables contain long vowels spelled with a single letter, followed by a single consonant, and a silent e. Examples of VCe syllables are found in wake, whale, while, yoke, yore, rude, and hare. Every long vowel can be spelled with a VCe pattern, although spelling "long e" with VCe is unusual.

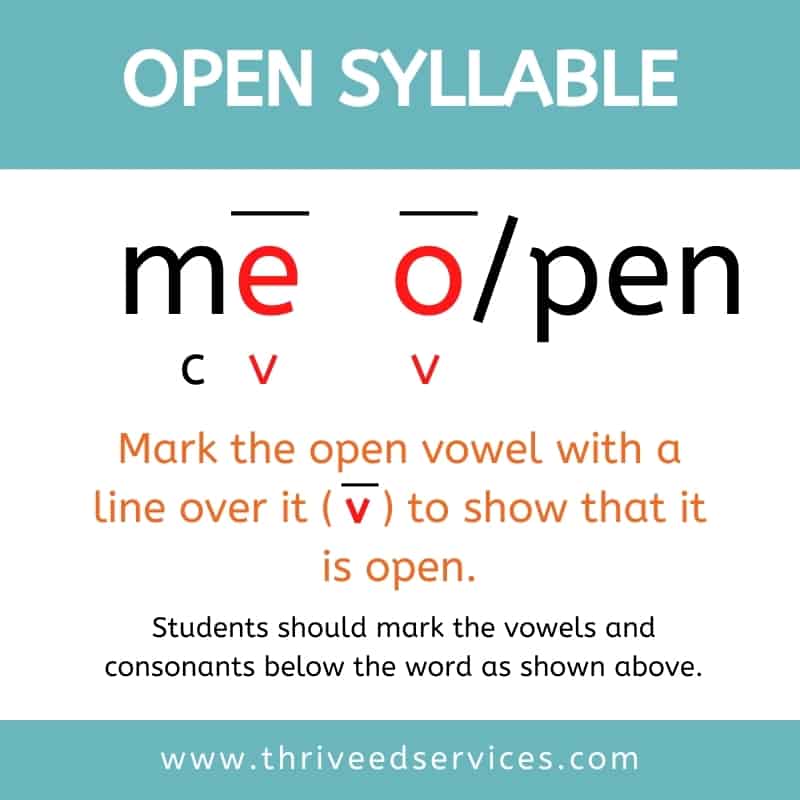

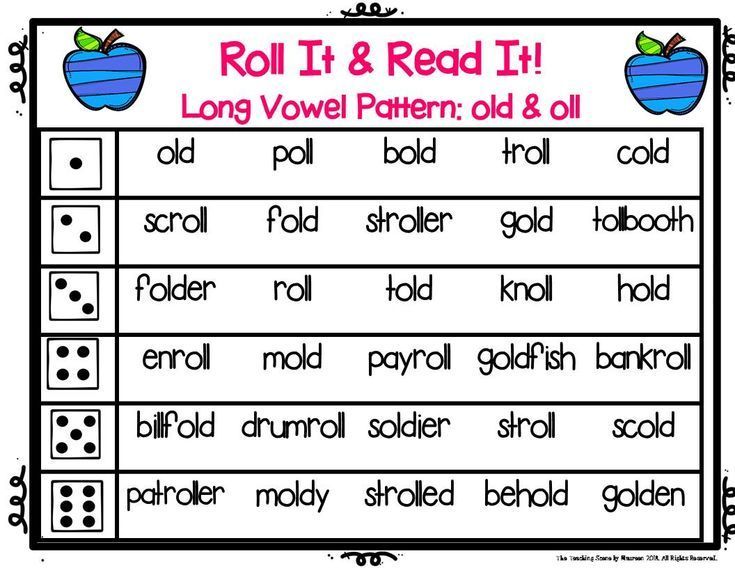

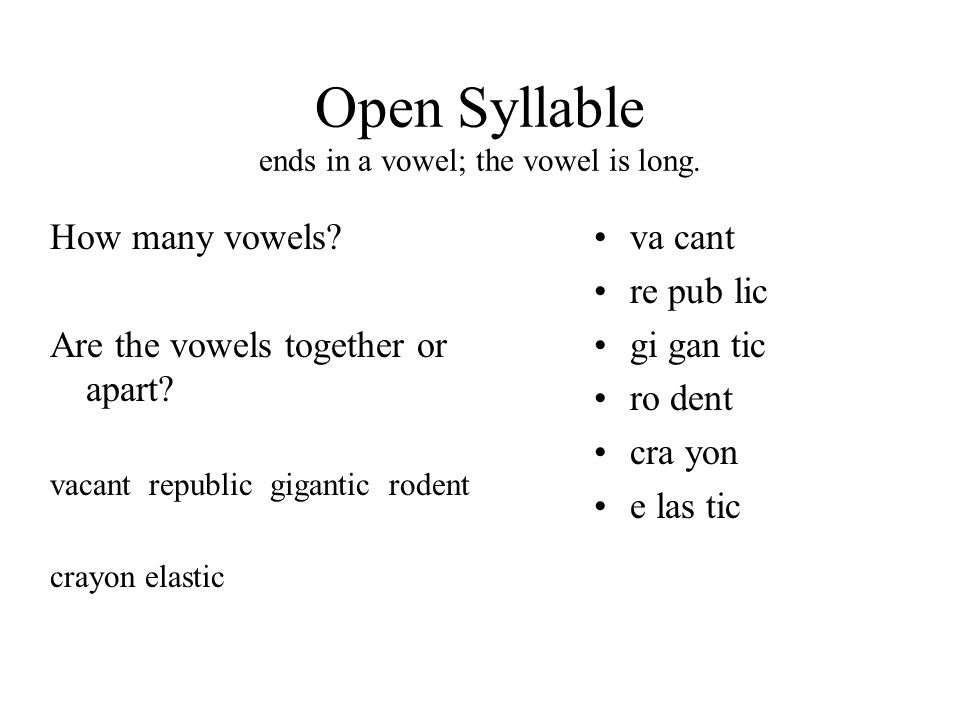

Open syllables

If a syllable is open, it will end with a long vowel sound spelled with one vowel letter; there will be no consonant to close it and protect the vowel (to-tal, ri-val, bi-ble, mo-tor). Therefore, when syllables are combined, there will be no doubled consonant between an open syllable and one that follows.

Therefore, when syllables are combined, there will be no doubled consonant between an open syllable and one that follows.

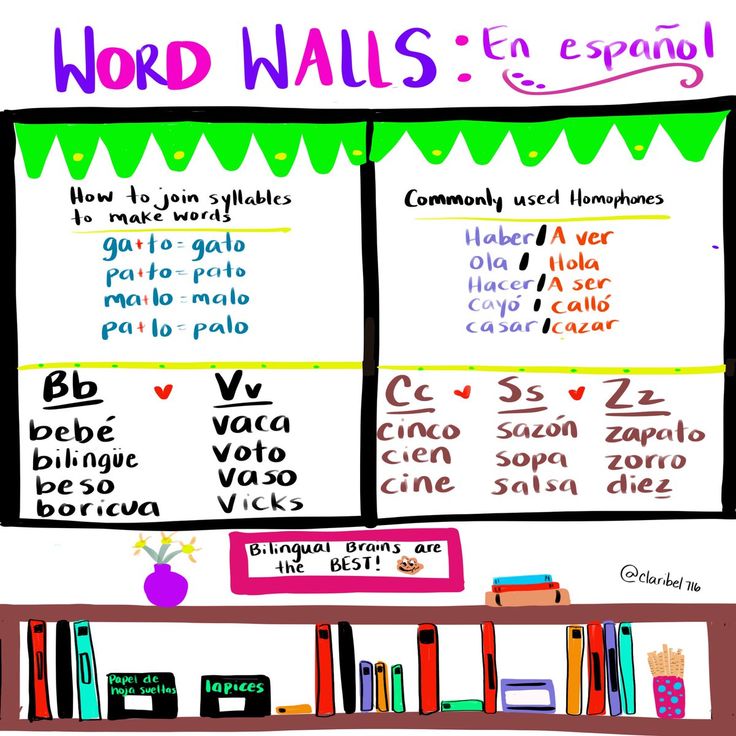

A few single-syllable words in English are also open syllables. They include me, she, he and no, so, go. In Romance languages — especially Spanish, Portuguese, and Italian — open syllables predominate.

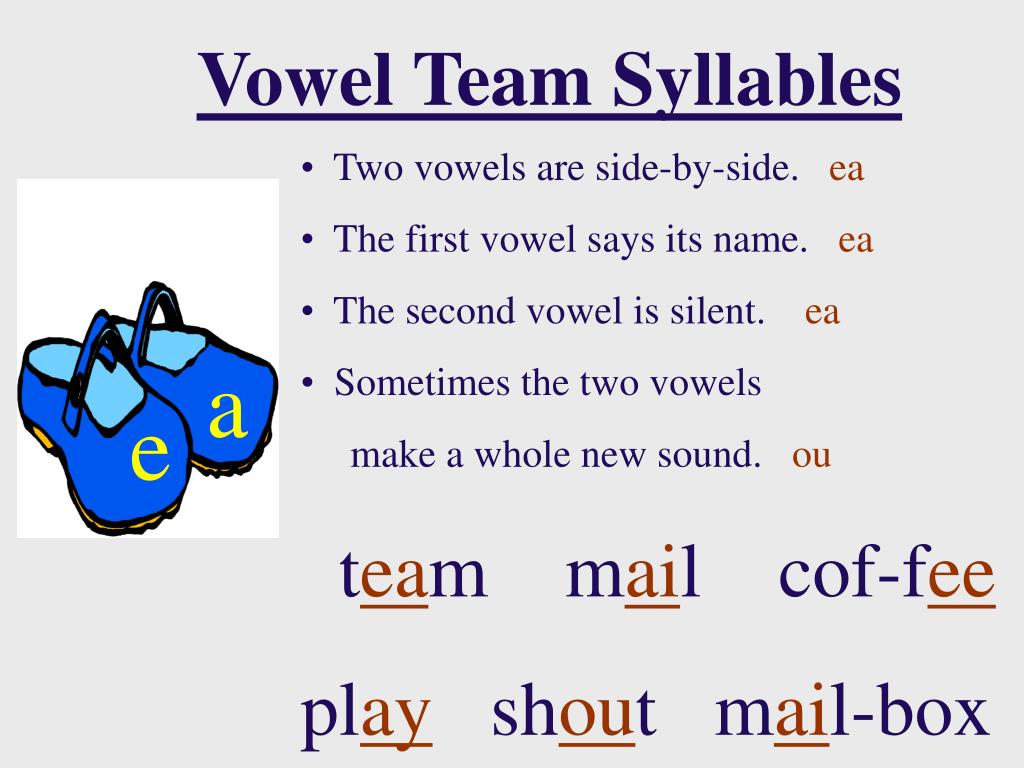

Vowel team syllables

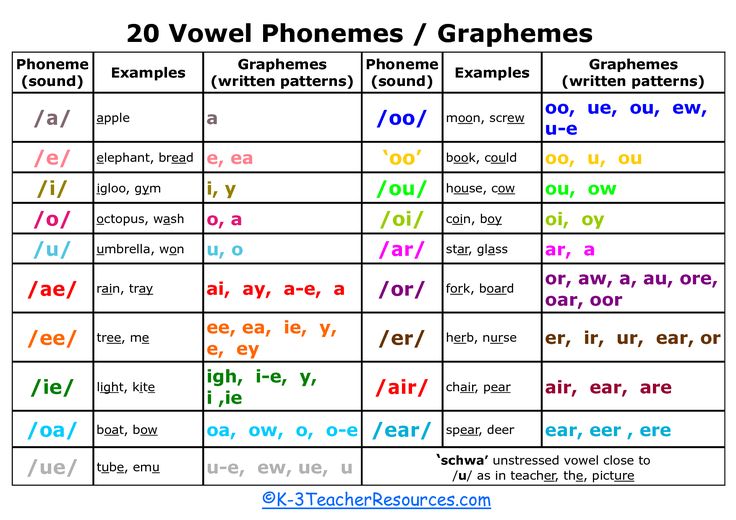

A vowel team may be two, three, or four letters; thus, the term vowel digraph is not used. A vowel team can represent a long, short, or diphthong vowel sound. Vowel teams occur most often in old Anglo-Saxon words whose pronunciations have changed over hundreds of years. They must be learned gradually through word sorting and systematic practice. Examples of vowel teams are found in thief, boil, hay, suit, boat, and straw.

Sometimes, consonant letters are used in vowel teams. The letter y is found in ey, ay, oy, and uy, and the letter w is found in ew, aw, and ow. It is not accurate to say that "w can be a vowel," because the letter is working as part of a vowel team to represent a single vowel sound. Other vowel teams that use consonant letters are -augh, -ough, -igh, and the silent -al spelling for /aw/, as in walk.

Other vowel teams that use consonant letters are -augh, -ough, -igh, and the silent -al spelling for /aw/, as in walk.

Vowel-r syllables

We have chosen the term "vowel-r" over "r-controlled" because the sequence of letters in this type of syllable is a vowel followed by r (er, ir, ur, ar, or). Vowel-r syllables are numerous, variable, and difficult for students to master; they require continuous review. The /r/ phoneme is elusive for students whose phonological awareness is underdeveloped. Examples of vowel-r syllables are found in perform, ardor, mirror, further, worth, and wart.

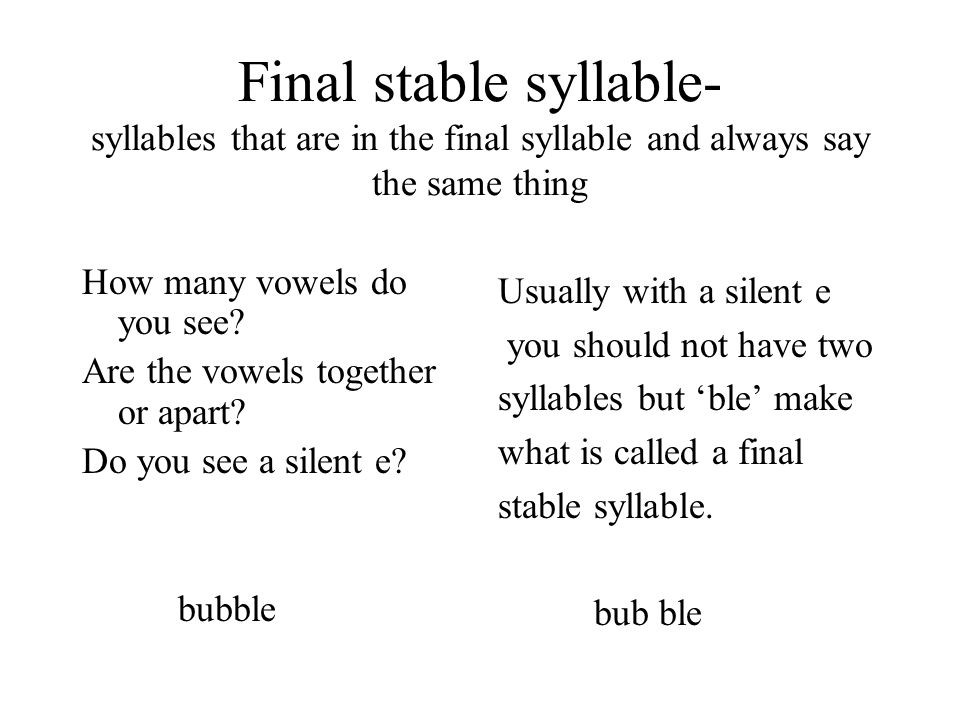

Consonant-le (C-le) syllables

Also known as the stable final syllable, C-le combinations are found only at the ends of words. If a C-le syllable is combined with an open syllable — as in cable, bugle, or title — there is no doubled consonant. If one is combined with a closed syllable — as in dabble, topple, or little — a double consonant results.

If one is combined with a closed syllable — as in dabble, topple, or little — a double consonant results.

Not every consonant is found in a C-le syllable. These are the ones that are used in English:

| -ble (bubble) | -fle (rifle) | -stle (whistle) | -cle (cycle) |

| -gle (bugle) | -tle (whittle) | -ckle (trickle) | -kle (tinkle) |

| -zle (puzzle) | -dle (riddle) | -ple (quadruple) |

Simple and complex syllables

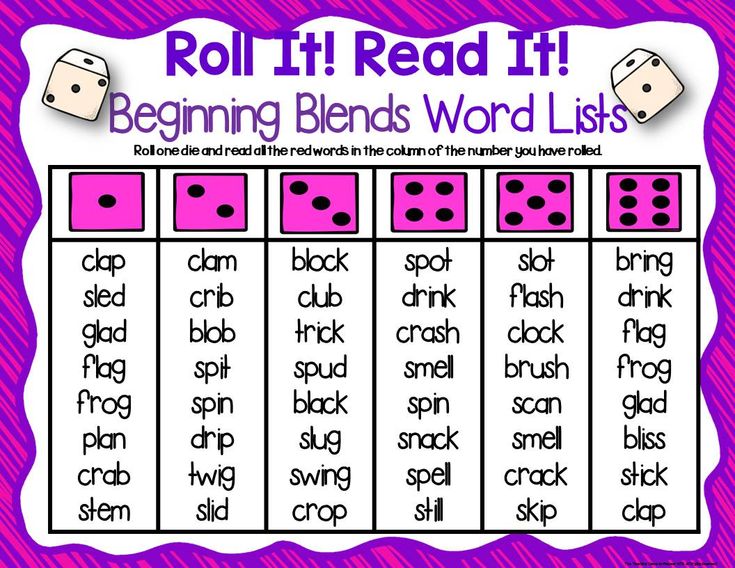

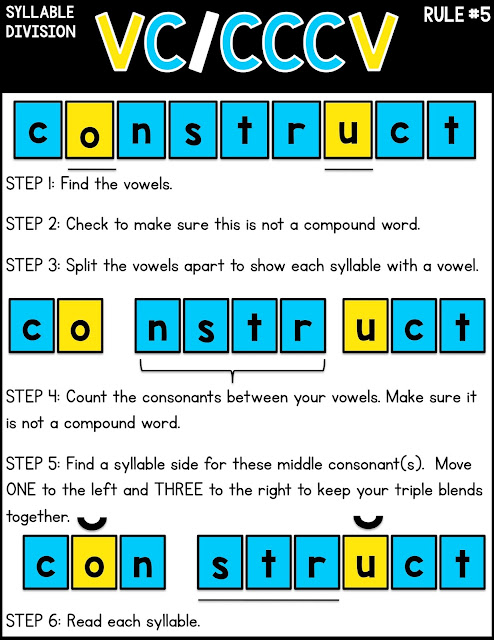

Closed, open, vowel team, vowel-r, and VCe syllables can be either simple or complex. A complex syllable is any syllable containing a consonant cluster (i. e., a sequence of two or three consonant phonemes) spelled with a consonant blend before and/or after the vowel. Simple syllables have no consonant clusters.

e., a sequence of two or three consonant phonemes) spelled with a consonant blend before and/or after the vowel. Simple syllables have no consonant clusters.

| Simple | Complex |

|---|---|

| late | plate |

| sack | stack |

| rick | shrink |

| tee | tree |

| bide | blind |

Complex syllables are more difficult for students than simple syllables. Introduce complex syllables after students can handle simple syllables.

Table 5.1. Summary of Six Types of Syllables in English Orthography

| Syllable Type | Examples | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Closed | dap-ple hos-tel bev-er-age | A syllable with a short vowel, spelled with a single vowel letter ending in one or more consonants. |

| Vowel-Consonant-e (VCe) | com-pete des-pite | A syllable with a long vowel, spelled with one vowel + one consonant + silent e. |

| Open | pro-gram ta-ble re-cent | A syllable that ends with a long vowel sound, spelled with a single vowel letter. |

| Vowel Team (including diphthongs) | aw-ful train-er con-geal spoil-age | Syllables with long or short vowel spellings that use two to four letters to spell the vowel. Diphthongs ou/ow and oi/oy are included in this category. |

| Vowel-r (r-controlled) | in-jur-i-ous con-sort char-ter | A syllable with er, ir, or, ar, or ur. Vowel pronunciation often changes before /r/. |

| Consonant-le (C-le) | drib-ble bea-gle lit-tle | An unaccented final syllable that contains a consonant before /l/, followed by a silent e. |

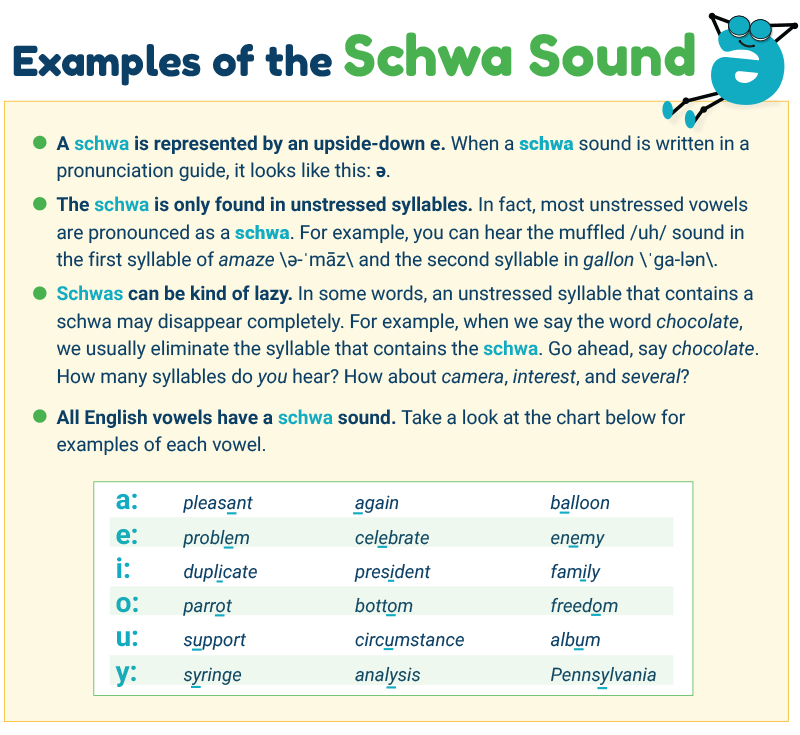

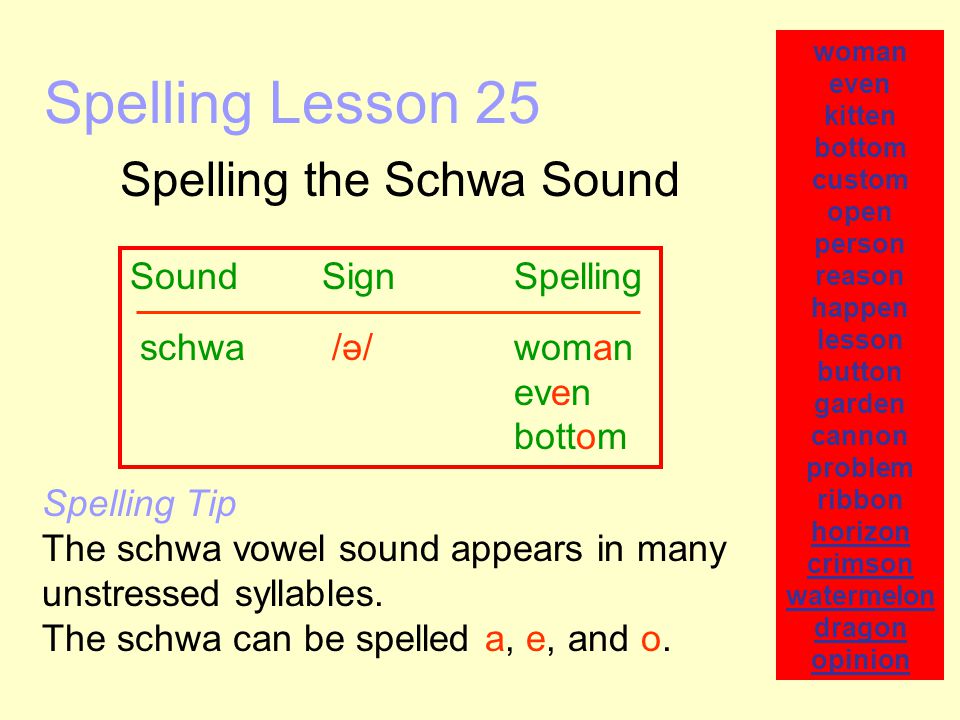

| Leftovers: Odd and Schwa syllables | dam-age act-ive na-tion | Usually final, unaccented syllables with odd spellings. |

2.5 Syllables – Psychology of Language

Skip to content

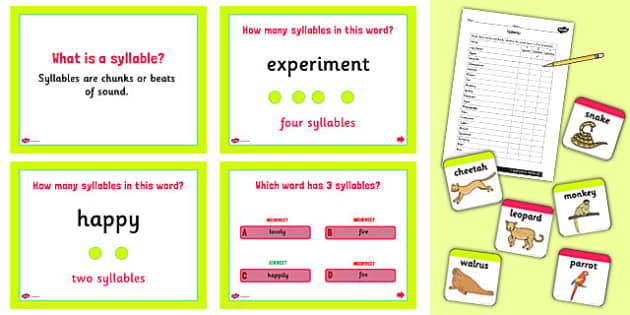

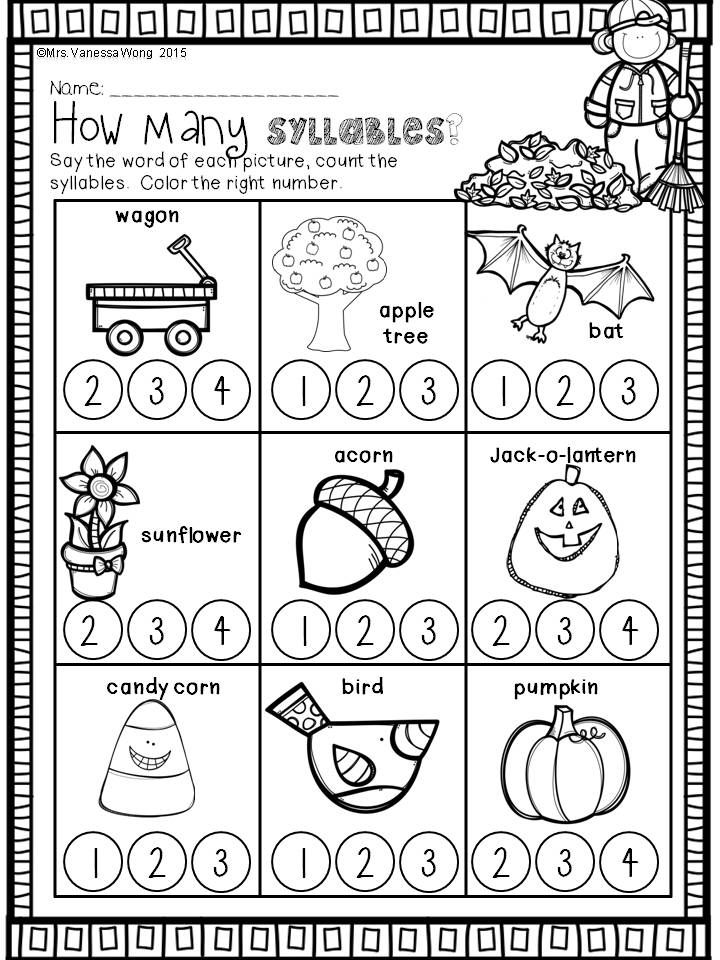

While phonemes are the smallest units of sound, we don’t actually speak in phonemes. If I say the word ‘cat’ /kæt/ and record it, I won’t be able to break it into three units of /k/, /æ/ and /t/. Therefore, the smallest unit of articulation is not the phoneme but rather the . Most native speakers of a language will know how many syllables are in a word in their language. You can try this in English by saying a word slowly. For example, the word ‘elephant’ has three syllables: e-li-phant. As seen in Figure 2.3, all syllables must have a mandatory or . This is usually a vowel. Some languages can also have a syllabic consonant as a nucleus of a syllable as in the English word ‘button’ [bʌtn̩] where there are two syllables [bʌ] and [tn̩]. You can see that the second syllable has no vowels but a syllabic [n̩] as the nucleus.

For example, the word ‘elephant’ has three syllables: e-li-phant. As seen in Figure 2.3, all syllables must have a mandatory or . This is usually a vowel. Some languages can also have a syllabic consonant as a nucleus of a syllable as in the English word ‘button’ [bʌtn̩] where there are two syllables [bʌ] and [tn̩]. You can see that the second syllable has no vowels but a syllabic [n̩] as the nucleus.

Consonants that come before the nucleus of a syllable are know as and those that come after it are called . The nucleus and coda of a syllable form a group called a . These onsets and codas can be complicated or simple depending on what is allowed in a language. English allows up to three consonants in the onset and at least as much in the coda. Consider the word ‘twelfths’ /twɛlfθs/. It has two consonants in the onset and four consonants in the coda. Generally, the onset is more restricted in what is consonants are allowed.

Figure 2.3 Syllable StructureIn English, you can have almost all consonants other than the velar nasal /ŋ/ as an onset. If there are two consonants in the onset and the first one isn’t /s/ then the second has to be either /l/, /r/, /w/, or /j/. if there are three consonants in the onset, then the first has to be an /s/, the second has to be either /p/, /t/ or /k/, and the third has to be either /l/, /r/ or /w/.

If there are two consonants in the onset and the first one isn’t /s/ then the second has to be either /l/, /r/, /w/, or /j/. if there are three consonants in the onset, then the first has to be an /s/, the second has to be either /p/, /t/ or /k/, and the third has to be either /l/, /r/ or /w/.

Consider some words in your language and try to syllabify them. Think of what phonemes occur in the onset, nucleus and coda of these syllables. Can you come up with long onsets and codas in your language? Ask a friend who speaks another language to do the same. Are there any differences between your languages’ syllable structure?

As we saw earlier, what is allowed in the onset, nucleus and coda of a language can be different across languages. While a sequence such as /pl/ is allowed in English, /ps/ would not be allowed. However, /ps/ is a legal sequence in Greek which is why we still spell ‘psychology’ with the ‘ps’ sequence even though English speakers don’t pronounce the ‘p’. Similar examples of Greek onsets include /mn/ as in ‘mnemonic’. Figure 2.4 illustrates the syllable structure of the word Tk’emlúps ‘Kamloops’ in Secwepemc. As we can see, Secwepemc allows the sequence of an unvoiced dental stop and a glottalized velar stop /tkˀ/ in the onset of its syllable. The sequence /ml/ is not a legal onset in Secwepemc, so it gets separated between two syllables, the /m/ becoming the coda of the first syllable and the /l/ becoming the onset of the second.

Figure 2.4 illustrates the syllable structure of the word Tk’emlúps ‘Kamloops’ in Secwepemc. As we can see, Secwepemc allows the sequence of an unvoiced dental stop and a glottalized velar stop /tkˀ/ in the onset of its syllable. The sequence /ml/ is not a legal onset in Secwepemc, so it gets separated between two syllables, the /m/ becoming the coda of the first syllable and the /l/ becoming the onset of the second.

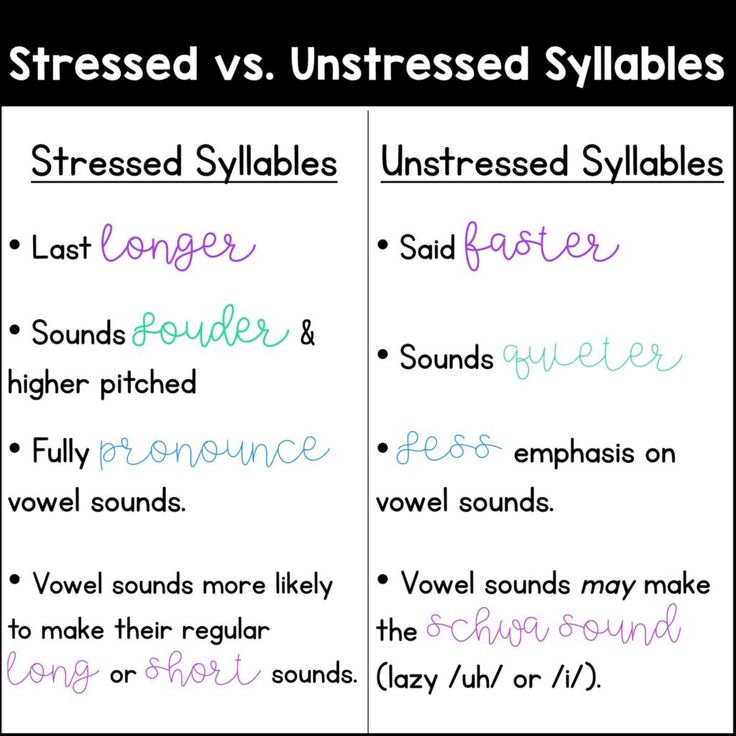

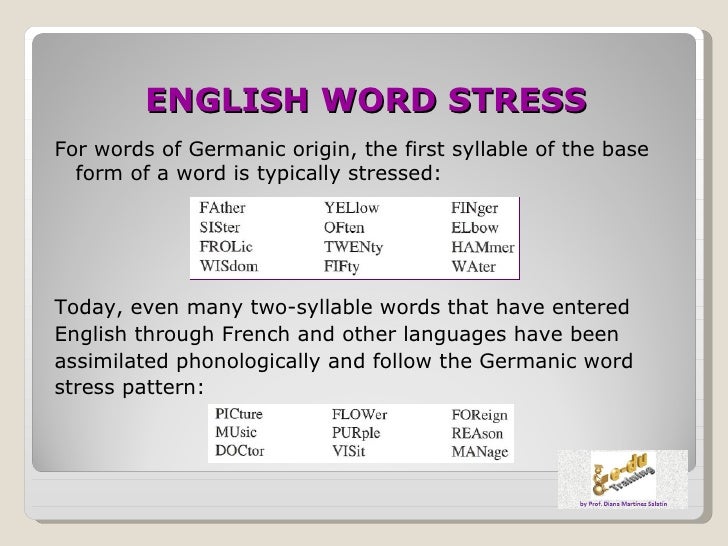

As syllables are the smallest units of articulation, they provide the rhythmic patterns of a language. In languages such as English, syllables carry features such as stress. This determines which syllable in a word receives emphasis. Try saying ‘I am recording a song.’ You will stress the second syllable in the word ‘recording.’ Now say ‘That was a record.’ You will find yourself placing more stress on the first syllable of the word ‘record.’ Languages that place equal time periods for stressed syllables are called stress-timed languages. English is a stress-timed language and we can see how this is employed in Shakespeare’s sonnets with iambic pentameters. Each line consists of five iambs and each iamb consists of two syllables with the second one more stressed that the first. As we see in Figure 2.5, this creates a beautiful pattern of unstressed and stressed syllables that may even go across word boundaries. Read the sonnet out loud and you will notice the stress patterns.

English is a stress-timed language and we can see how this is employed in Shakespeare’s sonnets with iambic pentameters. Each line consists of five iambs and each iamb consists of two syllables with the second one more stressed that the first. As we see in Figure 2.5, this creates a beautiful pattern of unstressed and stressed syllables that may even go across word boundaries. Read the sonnet out loud and you will notice the stress patterns.

Unlike English, other languages may produce each syllable with equal time. These are called syllable-timed languages. French is a good example of such a syllable-timed language. Poetry in syllable-timed languages will make less use of stress and will take into account what consonants appear in the coda of the syllable to determine the structure of their poems.

Syllables in Poetry (Shakespeare)

Syllables in Poetry 2

Media Attributions

- Figure 2.3 Syllable Structure by Dinesh Ramoo, the author, is licensed under a CC BY 4.

0 licence.

0 licence. - Figure 2.4 Syllable Structure of the word Tk’emlúps by Dinesh Ramoo, the author is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 licence.

- Figure 2.5 Stress Patterns in a Shakespearian Sonnet contains an edited version of The Droeshout portrait of William Shakespeare, and is a public domain work of art.

License

Psychology of Language by Dinesh Ramoo is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Share on Twitter

How to determine the poetic size • Arzamas

You have Javascript disabled. Please change your browser settings.

CourseHow Literature WorksLecturesMaterialsAuthor Kirill Golovastikov

Hello! Most likely, if you ended up here, you are a schoolboy, a student of a philological or journalism faculty, or even a poor parent of a schoolboy - and you need to determine the size of the poem, because it was given at home. In the past, I did a lot of versification - the science of rhythm in poetry - and I know that very often this not the most difficult thing is poorly understood and even more so explained even by those teachers who teach it. I will try to make your life easier.

In the past, I did a lot of versification - the science of rhythm in poetry - and I know that very often this not the most difficult thing is poorly understood and even more so explained even by those teachers who teach it. I will try to make your life easier.

Important! Here I want to help with practical tasks - determining meters and sizes. If you are preparing for a theoretical exam, it is better to memorize the definitions from those textbooks that teachers advised you to pass on five. And - I will immediately use terms like "syllabic-tonic" and "foot", without particularly explaining them: since you are reading this material, it means that you are at least approximately in the know.

So, first we will learn how to determine the meter, then we will move on to the size. But first -

Small warning

Let's agree on this: in each line, we will assign a serial number to each syllable - counting from left to right. In "The storm covers the sky with darkness" the syllable "bu" is the 1st, "rya" is the 2nd, and so on, up to the 7th "cro" and the 8th "et".

Optional introduction: why is it difficult for many to determine the meter?

Most likely, you were told that iambic and trochee are stops of two syllables. In the iambic foot, the first syllable is unstressed, the second is stressed; in chorea it is the other way around. It turns out that in verses written in iambic, stress should fall on even syllables in each line (2nd, 4th, 6th, and so on), and in trochee - on odd (1st, 3rd, 5th y…).

However, problems begin immediately. You take up "Eugene Onegin", firmly knowing from school that it was written in iambic tetrameter! (in general, most of the examples will be in iambic to make it more convenient, but the same can be said about the trochee):

My best honest right pitchfork,

Everything is in order: even-numbered syllables - 2nd, 4th, 6th, 8th - are really stressed.

No He y wa press ce ba for sta pitchfork

And beam she you du mother not could .

Stop. Everything is wrong here. There is no stress on the 6th syllable, on the 2nd, again on the 6th ... What is happening? It's still not iambic, is it?

There are many such examples. Here is another classic iambic tetrameter, now Tyutchev:

Thought out of re che nna i is l o live.

Here there is no stress on the 2nd syllable (“from”) and on the 6th (“I”), but there is on the 1st (“thought”), and also on the 7th (“is”), which seem to be unstressed in iambic. The most striking thing is that there are much more such lines that do not fit the line of the "ideal" iambic than the "ideal" ones! So, is it all a scam?

(In school versification, perhaps, they would have launched into discussions about Pyrrhic and Spondei, but this is of no use to us now - especially since they do not explain anything. )

)

The same with anapaests and dactyls (trisyllabic syllabic tonic feet). In dactyl lines, stress should fall on the 1st, 4th, 7th, 10th syllables, and so on. In anapaests - on the 3rd, 6th, 9th, 12th ... However, in fact, in dactyls very often there are no stresses on the 1st syllable, although they are needed there (" A for ok nom shelle st topo la …"). And in anapaests they are not needed there, but very often they turn out to be:

Child old picture hell,

where seven skins are lowered in the old fashioned way -

they fry alive, beat them thoughtfully,

cor mint herring and do not give to drink.

And when science triumphs,

enlightened torment enters :

paradise lost (view from the window) -

li pa, flowerbed, barbecue, elderberry.Sergey Gandlevsky

You ask - what kind of nonsense is this?! I'll explain now. But first -

But first -

The easiest way to identify the meter

The easiest way to define a simple (classical, syllabo-tonic) meter is the scandovka. The way the fans shout chants in the stands. An attempt to feel the rhythm, substituting accents where they are not, but they are needed, and not making them where they seem to be, but the rhythm tells not to strike. This is done intuitively:

my YA! for SA! my HONOR! PRA! forks

thought And! zre CH! to Me! is FALSE!

Poetry scholar Alexander Ilyushin suggested an elegant way of translating the results of chanting into the language of poetry. He compared the five basic syllabo-tonic meters with five forms of a popular Russian male name:

Chorya: VA NYA- VA NYA- VA NYA- VA Nya

YAMB: and Van Van VAN WAN Dactil: VA Nechka- VA Nechka- VA Nechka- VA Nechka

amphibrachia: Va nyu Sha-vu Sha-vu Shau

Anapaest: Jo Ann -Io ann -Io ann -Io ann

Scanned a line? Now look at what the result looks like more - "Ivan", "Vanya" or "John". This not quite scientific method will always remain with you as a reinforcement. And now -

This not quite scientific method will always remain with you as a reinforcement. And now -

A bit of science

What are the definitions of iambic and chorea accepted in strict science? Something like this: iambic is a meter in which the stresses of non-monosyllabic words can fall on even-numbered places in a line. Trochee - the same, but for odd numbers.

Here, firstly, the word “may” is added, which means they are not obliged: this explains the lines “When it’s not a joke for couldn’t” (iambic, although there is no stress on the 6th syllable) or “He in is important I forced myself” (there is no stress on the 2nd). Secondly, the word “non-monosyllabic” is added: then you don’t have to think about examples like “ Thought spoken is a lie” or “ Run sledge along the wide Neva” (or, in the case of trochees, “On the same day became reign he"). Indeed, there are “extra” stresses here - but they are all provided with monosyllabic words, and we agreed not to take them into account.

Lectures on poetry and prose

Russian literature of the 20th century

Lectures on Blok, Mayakovsky, Khlebnikov and others

How literature

lectures works, in which literary criticism becomes an accurate science and reveal the secrets of Pushkin, Pasternak, Mandelstam — and artistic creativity in general

But there are two problems. Firstly, this definition is true only for iambic and chorea (that is, disyllabic syllabic-tonic meters). For dactyl, amphibrach or anapaest (three-syllable syllabo-tonic meters), it would have to be changed to "stresses of non-monosyllabic and non-disyllabic words", which is already too complicated. And the definitions of many other meters are not classical (syllabic-tonic), but, for example, dolniks (“We are all hawkers here, harlots, / How unhappy we are together! / There are flowers and birds on the walls / Yearning for the clouds”) or tacticians (“ A black man was running around the city. / He extinguished the lanterns, climbing the stairs") cannot be deduced from this rule at all.

/ He extinguished the lanterns, climbing the stairs") cannot be deduced from this rule at all.

Secondly, and most importantly, these rules can be violated - in one line or another. They can be violated by accident, by oversight: “I propose to drink in e go memory ...” (“A feast during the plague”, this is iambic pentameter).

May be violated because the poet adapts the language to his needs: “ During all the time of the conversation / He stood behind the fence ...” (“The Tale of Tsar Saltan”, trochee): here we must “swallow” the emphasis on “in everything”, so as not to assume that Pushkin has an error in the meter.

And, most importantly, they can be violated on purpose. Just because no rules are given to a poet - he, the poet, sets the rules, and not some miserable versifiers. Here is a poem by Marina Tsvetaeva, where iambic is broken regularly:

When offended - drunk

Angry Soul,

When she swore seven times

Fight demons -Not with those showers of fires

Into the abyss lashed down:

With the earthly baseness of days.

With human bones -Trees! I'm coming to you! Save yourself

From the roar of the market!

your swings up

How the heart breathes!God-fighting oak! In battles

Walking with all roots!

willows my seers!

Birches-virgins!Elm - furious Absalom,

Rearing Tortured

Pine - you, my mouth psalm:

Bitterness Rowan…To you! In lively mercury

Foliage - let it crumble!

Open your arms for the first time!

Throw away manuscripts!Green reflections swarm…

As in hands - splashing ...

Hairy mine,

My trembling!

An iambic is broken four times - however, this does not make it not an iambic. First, if this is not iambic, then what else? Secondly, "violation" of the meter does not mean that these are bad poems. On the contrary, it can be interpreted as a manifestation of poetic power: the poet himself set the conditions - he himself violated them, he has the right.

Arzamas for classes with schoolchildren! A resource pack for teachers and parents

Lectures and texts on literature, history and art, games, tests, videos, podcasts and more

What to do?!

So you tried chanting or something, but it didn't work or you're not sure. Here's what to do. Arm yourself with a pencil. Take the text or, if it is large, its fragment - 16 lines, no less. Arrange the stresses in it as it seems right to you, taking into account intuition (it is clear that nouns and verbs are almost always stressed, prepositions and conjunctions are almost always unstressed, and the rest of the speech is different. For example, if it seems to you that one and the same word - “he”, “they”, “was”, “became”, “his”, “his”, “everything” - in one case it’s more likely to be stressed, and in the other it’s more likely not - mark it like that).

Between the stresses you will have unstressed syllables: somewhere one, somewhere two at once, somewhere three, four, five, and somewhere zero. Calculate which of these intervals occur most often, and which are rarer - and check the table:

Calculate which of these intervals occur most often, and which are rarer - and check the table:

Among poetic forms, free verse is also distinguished, it is also free verse: it is believed that sometimes a poet writes without any metric scheme in his head, as God puts on his soul. In this case, the inter-strike intervals will be distributed as follows: 2 and 3 will occur most often, 1 and 4 less often, 0 and 5 even more rarely, but none of them will be specifically avoided (for example, if 5 turns out to be more often than 4, and there will be no zeros at all, a reason to suspect that something is wrong - that this is not just free verse, but something else).

We almost did everything. It remains to apply Occam's razor. In the table, the sizes go from the most strict to the most relaxed - you need to make sure that you did not choose a looser size when a more strict match could be found:

- If you got a tactician, but there are not enough intervals of 2, then check if it is actually iambic and trochee (using chanting).

- If it seems to you that you have a dolnik, then with the help of chanting, check if it is an ideal dactyl, or anapaest, or amphibrach. Remember Gandlevsky's poem? It has a lot of "superfluous" (poeticists would say, super-scheme) stresses on the 1st syllable, but if you start chanting and humming it, it becomes clear that this is the purest anapaest.

If you immediately got iambs/trochaeas or dactyls/amphibrachs/anapaests, then determine what it is exactly (iambus or trochaic, and so on) by scanning.

Meter identified. And the size?

Size is to calculate how much a stop (or "Ivanov-Vanyush") fits in a line. How many times they meet, so put: five "Vanyush" - a five-foot amphibrach, three "Vanya" - a three-foot trochee, and so on. If in different lines the number of "Van-Ivans" turns out to be different (as in Krylov's fables, "Woe from Wit" or Mayakovsky's "To Comrade Netta, the Steamboat and the Man"), then this is called free (not free!) Verse, so write: free iambic/amphibrach. If it is different, but alternates regularly (as in Pushkin's "Monument": first three lines of iambic six-foot, then one - four-foot, and then again), then say so: a regulated alternation of such and such iambic lines.

If it is different, but alternates regularly (as in Pushkin's "Monument": first three lines of iambic six-foot, then one - four-foot, and then again), then say so: a regulated alternation of such and such iambic lines.

However, there are important clarifications. Often the line is not completely divided into stops: at the end of the line there are, as it were, halves or thirds of the stops. For example, in the line "Whirlwinds of snow twisting" the last foot of the chorea lacks one syllable to the fullness (Vanya-Vanya-Vanya-Va!). And in the line “Because I am tart sadness”, on the contrary, the syllable “pour” seems to be superfluous (or, if you are an optimist, two syllables are missing to the full foot of the anapaest). The rule is simple: an “incomplete” foot is considered if it has a stressed syllable (therefore, “Snow whirlwinds twisting” is a four-foot trochee no matter what), and it does not count if only unstressed syllables are taken from the foot (“Because I am tart sadness" - only a three-foot anapaest, not a four-foot one).

Don't fall for another trap: sometimes a whole foot could fit at the end of a line, but if there is no accent, you don't need to take it into account. The lines “In the evenings over restaurant us ” and “As promised, without deceiving ” is iambic tetrameter, although after the last stress there are still two (“us”) and three (“whipping”) unstressed syllables, respectively.

There is also a dolnik and a tactician, they are not divided into feet, they count the accents. In tacticians (which are actually very rare in Russian poetry, especially in their pure form!) just count the number of stroke intervals in each line, all these ones, twos and threes. Have you counted? Now add one: if there are two intervals in the lines, then there are three accents, which is logical. Write, respectively: three-stroke tactician.

You have to be careful with sharers. The easiest way is to find lines that have only intervals of 1 and 2 syllables, and do the same with tacticians: count the number of intervals and add one. But if you decide to determine the size by lines that have intervals 4 and 5, then count differently: intervals 1 and 2 are one, and 4 or 5 are two. Then add one too.

But if you decide to determine the size by lines that have intervals 4 and 5, then count differently: intervals 1 and 2 are one, and 4 or 5 are two. Then add one too.

In ver libre (free verse), size is not considered, hurrah!

What, is that all?

No, of course not. There are many complex and transitional forms. There are complex works - in which the author, in different lines or fragments, likes to push together meters that are usually incompatible: for example, iambs, anapaests and dolniks. Finally, there are complex hybrid sizes (which, for example, says "Don't leave the room ..." by Brodsky). But you are unlikely to come across these complex forms on the exam - they are more likely for specialists.

P.S. Why is all this necessary?

For happiness! That is, of course, I understand those who say that it is difficult and boring, but you understand me too. Firstly, poetry (not as basic as we have just revealed) is an exact science, with graphs and formulas, and you can get the same pleasure from it that a mathematician gets from an elegant theorem. In addition, poetry is often like a detective, and solving riddles is very exciting. Finally, verse in its highest manifestations is very strongly connected with poetry - with the language in which the poem is written, and with the meanings that are expressed in it. In some masterpieces, this achieves an amazing connection. In an old lecture, I tried to reveal one such example - on the example of Lermontov's "Prayer" (I don't know if he will convince you):

In addition, poetry is often like a detective, and solving riddles is very exciting. Finally, verse in its highest manifestations is very strongly connected with poetry - with the language in which the poem is written, and with the meanings that are expressed in it. In some masterpieces, this achieves an amazing connection. In an old lecture, I tried to reveal one such example - on the example of Lermontov's "Prayer" (I don't know if he will convince you):

cheat sheets for those who are preparing for the exam or want to understand the topic

All Russian literature of the 19th century in 230 cards

Russia, West, East: 10 centuries in one table

From Rurik to Robespierre - a synchronous table on world history

The entire 19th century in one table

From Napoleon to the revival of the Olympic Games: main events, heroes and ideas in a synchronous table of history

Philosophy of the Enlightenment in one table styles of painting in one table

Laying it all out: from Fauvism to Conceptualism

Medieval literature: main books in one table

Beowulf, Dante, Edda, troubadours and others

Images: Rijksmuseum

Tags

Poetry

Cheat sheet

Svetlana Sheils: "The happiest day was when I found out that I have relatives in Russia" She recalls her childhood in exile, meetings with her father, tea in Kuprin's kitchen, life in America, and an amazing acquaintance with her sister

Do you want to know everything?

Subscribe to our newsletter, you'll love it. We promise to write rarely and to the point

We promise to write rarely and to the point

Courses

All courses

Special projects

Lectures

13 minutes

1/5

Why does a literary text affect people?

What tricks Pushkin, Mandelstam and Gogol use to infect us with their feelings

Reading Alexander Zholkovsky

What tricks Pushkin, Mandelstam and Gogol use to infect us with their feelings

11 minutes

2/5

How does the author create his world?

The unchanging principles by which Mandelstam and Pasternak build their texts and which make their poems so recognizable

Reading Alexander Zholkovsky

The unchanging principles by which Mandelstam and Pasternak build their texts and which make their poems so recognizable

3/5

When does form become content?

Rhymes, repetitions and other devices that help to increase the impact of the text and emphasize its meaning

Reading by Alexander Zholkovsky

Rhymes, repetitions and other techniques that help enhance the impact of the text and emphasize its meaning

13 minutes

4/5

How can a writer express everything in one word?

Separate objects that express the whole meaning of the work or the entire creative style of the author (from Chekhov to Sherlock Holmes) )

14 minutes

5/5

Why does literature talk about itself?

Poems about writing poetry and novels written on top of other novels

Reading by Alexander Zholkovsky

Poems about writing poetry and novels written on top of other novels

Materials

6 evidence that literature is useful in ordinary life 04 90 six concepts from the theory of literature

Alexander Zholkovsky: “I wonder what the secret of the focus is”

© Arzamas 2023. All rights reserved

All rights reserved

Trochee, iambic, anapaest, amphibrach, dactyl. Examples. How to determine and learn the poetic size?

Poetic meter

The meter is the order (rule) of alternating stressed and unstressed syllables.

The size is usually defined as a sequence of several feet.

Poetic meters are never performed exactly in a poem, and there are often deviations from a given scheme.

The omission of stress, that is, the replacement of a stressed syllable by an unstressed one, is called pyrrhic , while the replacement of an unstressed syllable by a stressed one is called sponde .

Syllabo-tonic meters

In Russian syllabo-tonic versification

five feet:

- Khorei

- Yamb

- Dactyl

- Amphibrachium

- Anapaest

Poetic meters (in the syllabo-tonic system of versification)

Legend

___/ - stressed syllable

___ - unstressed syllable

- Two-syllable meter: __/__ - foot Chorea

Khorei - TWO-syllable meter of verse, in which

the stressed syllable is in the first place , the second is unstressed.

To remember:

Clouds are rushing, clouds are winding,

__ __/ - foot Yamba

On ferrets they flyYamb - TWO-syllable meter in which

the first syllable is unstressed the second is stressed. - Trisyllabic meter: __/__ __ - foot Dactyl

Dactyl is a three-syllable meter in which

the first syllable is stressed , the rest are unstressed.To remember:

Dug dactyl deep hole

__ __/__ - foot AmphibrachAmphibrach - THREE-syllable meter in which

__ __ __/ - foot Anapesta

the second syllable is stressed , the rest are unstressed.

Anapaest0052 the third syllable is stressed , the rest are unstressed.

To memorize names

Three-syllable sizespoems you need to learn

the word LADY .Lady deciphers as follows:

D - D Actile - Stress to the first syllable,

AM AM Fibrahiy - stress on the second syllable,

A - A A napest - stress stress on the third syllable.To memorize ALL poetic meters, you need to learn stresses in five variants

named after Ivan:- Va-nya - trochee (2 syllables, the first is stressed)

- I-van - iambic (2 syllables, the second is stressed)

- Va-ne-chka - dactyl (3 syllables, first stressed)

- Wa-nu-sha - amphibrach (3 syllables, second stressed)

- I-o-ann - anapaest (3 syllables, third stressed)

- Va-nya - trochee (2 syllables, the first is stressed)

Examples

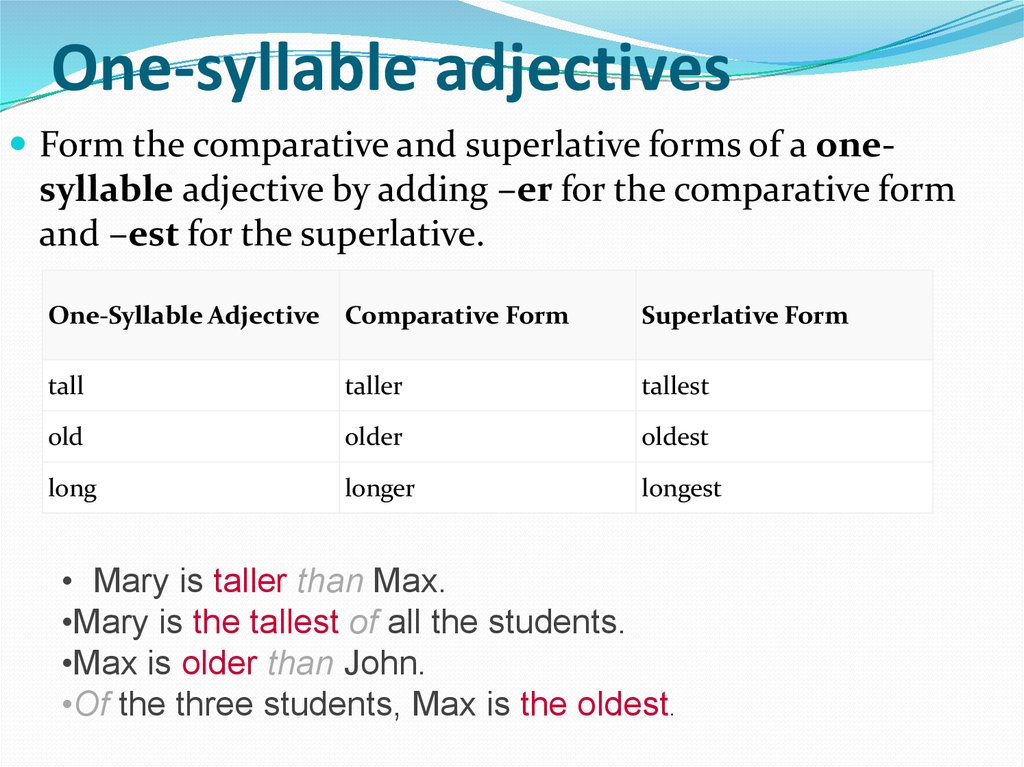

| Examples of poems | Poetic meter |

Example of a four-foot trochaic: The storm covers the sky with darkness | Chorey __/__ |

Example of a four-foot trochaic: I came to you with greetings | Chorey __/__ |

Example trochaic pentameter: I go out alone on the road; | Chorey __/__ |

Example of trimeter trochaic: The swallows are gone | Chorey __/__ |

Example iambic tetrameter: My uncle of the most honest rules, | Yamb __ __/ |

Example iambic tetrameter: I remember a wonderful moment | Yamb __ __/ |

Example iambic pentameter: Together we are dressed to know the city, | Yamb __ __/ |

Example iambic pentameter: You will be sad when the poet dies, | Yamb __ __/ |

Example of a three-foot dactyl: Whoever calls - I do not want | Dactyl __/__ __ |

Example of a four-foot dactyl: Heavenly clouds, eternal wanderers! | Dactyl __/__ __ |

Example of a four-foot dactyl: Glorious autumn! Healthy, vigorous | Dactyl __/__ __ |

Example trimeter amphibrach: It is not the wind that rages over the forest, | Amphibrachium __ __/__ |

Example tetrameter amphibrach: Dearer than the fatherland - did not know anything | Amphibrachium __ __/__ |

Example trimeter amphibrach: There are women in Russian villages | Amphibrachium __ __/__ |

Example trimeter amphibrach: In the midst of a noisy ball, by chance, | Amphibrachium __ __/__ |

Example of a three-foot anapaest: Oh, spring without end and without edge - | Anapaest __ __ __/ |

Example of a three-foot anapaest: There are in your secret melodies | Anapaest __ __ __/ |

Example of a three-foot anapaest: I will disappear from melancholy and laziness, | Anapaest __ __ __/ |

| Example (diverse size) alternately: dactyl, amphibrach and anapaest: Not complicated at all |

Dactyl __/__ __ Amphibrachium __ __/__ Anapaest __ __ __/ |

Poetic measurementstrochee, iambic, dactyl, amphibrach, anapaest See: other Examples of poems | |

How to determine the meter?

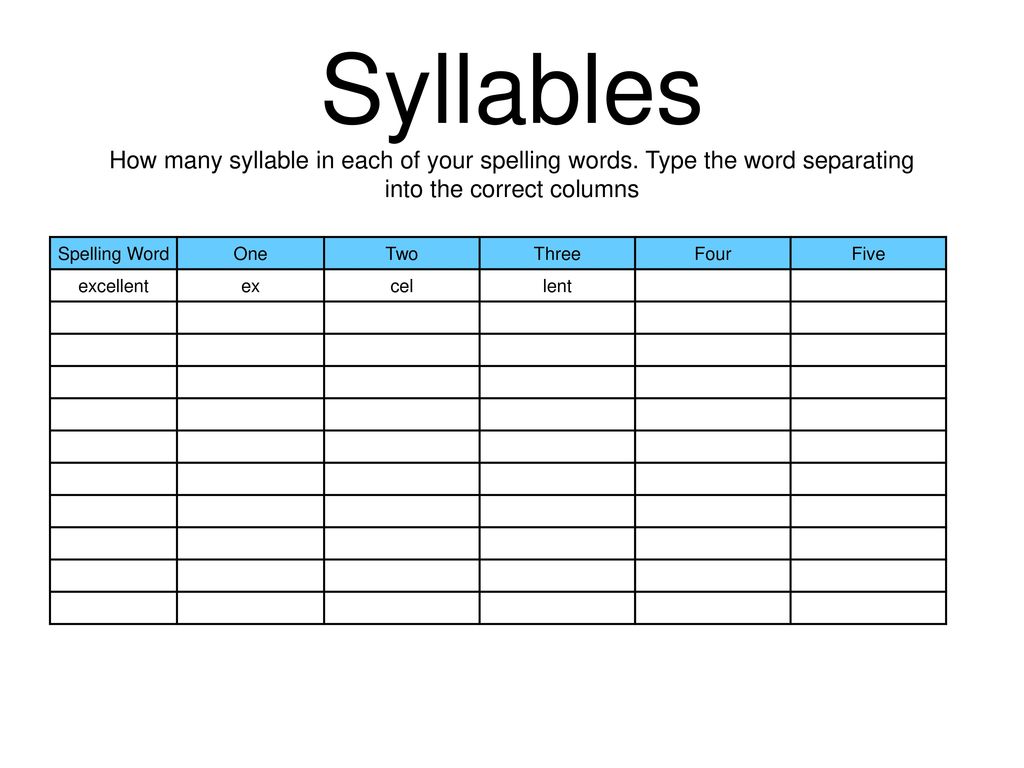

- Determine the number of syllables in a line. To do this, underline all vowels.

- We pronounce the line in a singsong voice and place the stresses.

S. Pushkin)

S. Pushkin)

S. Pushkin)

S. Pushkin)

..

..

Block)

Block)  Block)

Block)  Fet)

Fet)  V. Onufriev)

V. Onufriev)