Learning by play

Play-Based Learning: What It Is and Why It Should Be a Part of Every Classroom

Wednesday, April 21, 2021

Renowned psychologist and child development theorist Jean Piaget was quoted in his later years as saying “Our real problem is – what is the goal of education? Are we forming children that are only capable of learning what is already known? Or should we try developing creative and innovative minds, capable of discovery from the preschool age on, throughout life?”

No doubt, Piaget didn’t have to deal with standardized assessment—and he would be at odds with those officials who prioritize test high scores and good grades as the primary goals of education. Instead, Piaget would advocate for helping students understand learning as a lifelong process of discovery and joy. Why do we question the value of this approach?

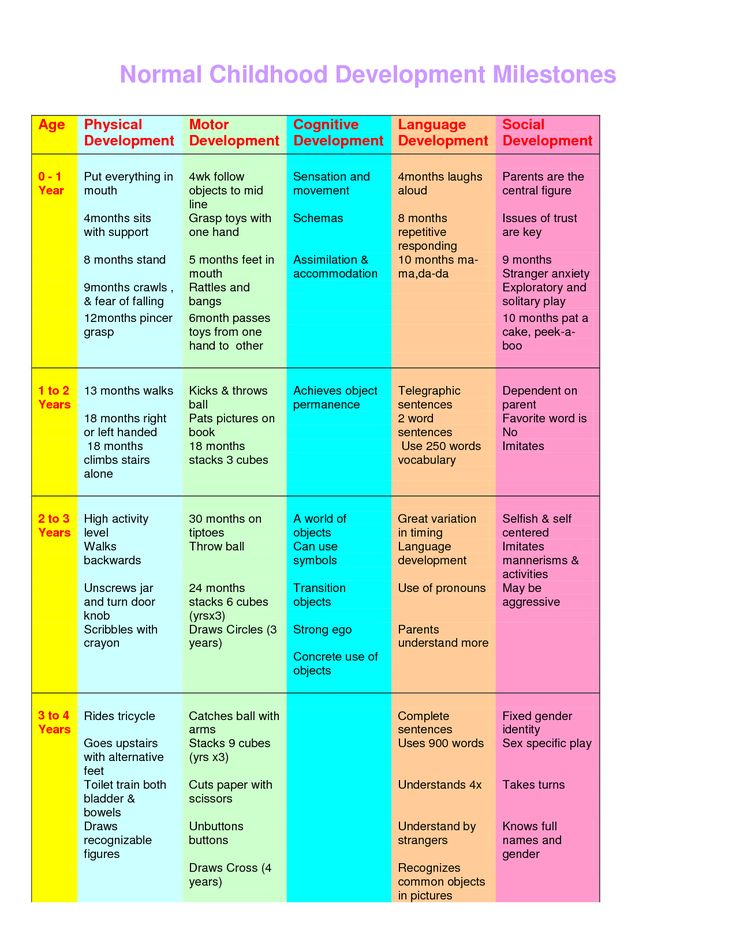

Being a kid is critical. We see the signature of early childhood experience literally in people’s bodies: as this study from the Harvard Center on the Developing Child shows, positive early experiences lead to longer life expectancy, better overall health, and improved ability to manage stress. Plus, long-term social emotional capabilities are more robust when children have a chance to learn through play; form deep relationships; and when their developing brains are given the chance to grow in a nurturing, language-rich, and relatively unhurried environment.

This is something that as educators we understand in our souls but often find it difficult to implement given the restraints and restrictions of the modern classroom and accountability environment. But, it’s critical to address this disconnect directly in order to make progress. So, let’s talk about why students need play and how we can bring it into our own classrooms—even if we have to sneak it in, and even if we are working with kids who are not so little anymore.

Defining a Play-Based Approach to LearningPlay is the defining feature of human development: the impulse is hardwired into us and can’t be suppressed. It’s crucial that we recognize that while the play impulse is one thing, understanding the nuts and bolts of actually playing is not always so natural, and may require careful cultivation.

That’s why a play-based approach involves both child-initiated and teacher-supported learning. The teacher encourages children’s learning and inquiry through interactions that aim to stretch their thinking to higher levels. There are other foundational thinkers who have built from Piaget’s theories that support this; educators like Montessori and Stanley Greenspan have recognized that the way to teach a child is through their own interests and developed concrete strategies to do so.

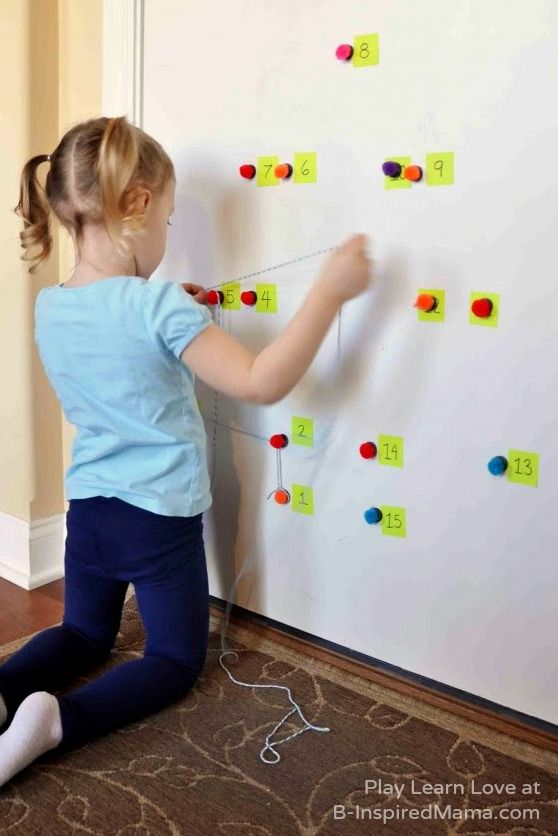

For example, while children are playing with blocks, a teacher can pose questions that encourage problem solving, prediction, and hypothesizing. The teacher can also bring the child’s awareness towards mathematics, science, and literacy concepts. How tall can this get? How many blocks do you need? Can you BLOW the house down? Who else does that? These simple questions elevate the simple stacking of blocks to application of learning. Through play like this, children can develop social and cognitive skills, mature emotionally, and gain the self-confidence required to engage in new experiences and environments.

When children engage in real‐life and imaginary activities, play can challenge children’s thinking.

Children learn best through first-hand experiences—play motivates, stimulates and supports children in their development of skills, concepts, language acquisition, communication skills, and concentration. During play, children use all of their senses, must convey their thoughts and emotions, explore their environment, and connect what they already know with new knowledge, skills and attitudes.

It is in the context of play that children test out new knowledge and theories. They reenact experiences to solidify understanding. And it is here where children first learn and express symbolic thought, a necessary precursor to literacy. Play is the earliest form of storytelling. And, it is how children learn how to negotiate with peers, problem-solve, and improvise.

It is in play that basic social skills—like sharing and taking turns—are learned and practiced. Children also bring their own language, customs, and culture into play. As an added benefit, they learn about their peers’ in the process.

Children also bring their own language, customs, and culture into play. As an added benefit, they learn about their peers’ in the process.

Involvement in play stimulates a child’s drive for exploration and discovery. This motivates the child to gain mastery over their environment, promoting focus and concentration. It also enables the child to engage in the flexible and higher-level thinking processes deemed essential for the 21st century learner. These include inquiry processes of problem solving, analyzing, evaluating, applying knowledge and creativity.

Finally, play supports positive attitudes toward learning. These include imagination, curiosity, enthusiasm, and persistence. The type of learning processes and skills fostered in play cannot be replicated through traditional rote learning, where the emphasis is on remembering facts.

Play-Based Learning and Executive FunctionChildren are naturally motivated to play. A play-based program builds on this motivation, using it as a context for learning. In this framework, children can explore, experiment, discover, and solve problems in imaginative and playful ways. They also expand their executive function skills by practicing their ability to retain information—like where the butterfly was in the spread of memory cards, who had the “4” in Go Fish, and what color card they have and need for in UNO.

In this framework, children can explore, experiment, discover, and solve problems in imaginative and playful ways. They also expand their executive function skills by practicing their ability to retain information—like where the butterfly was in the spread of memory cards, who had the “4” in Go Fish, and what color card they have and need for in UNO.

When students play games that involve strategy, they have an opportunity to make plans, and then to adjust those plans in response to what happens during gameplay. This engages other critical executive function skills like inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility, and working memory. Think Battleship, checkers, tick-tack-toe, or Hide-and-Go-Seek; these games have children develop a plan and adjust on the fly in response to the other player.

Teachers can provide opportunities for students to build their executive function skills through meaningful social interactions and fun games—including activities as common as checkers, Simon Says, and I Spy. Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child offers lots of great ideas for children at different ages.

Harvard’s Center on the Developing Child offers lots of great ideas for children at different ages.

Play-based learning is an important way to develop active learning. Active learning means using your brain in lots of ways. When children play, they explore the world—and build on their understanding of the natural and social environments around them.

On the physical level, kids work on both gross and fine motor development through play. Students working in a play-based classroom explore spatial relationships and hone these important motor capabilities. In fact, it is before the age of 7 years—traditionally known as “pre-academic” age—when children desperately need to have a multitude of whole-body sensory experiences daily in order to develop strong bodies and minds. This is best done outside where the senses can be fully engaged, and young bodies are challenged by the uneven and unpredictable, ever-changing terrain—but a well-equipped, thoughtfully set-up classroom can be just as effective.

Children build language skills while developing content knowledge. Plus, cooperative experiences provide children the opportunity to cultivate social skills, competencies, and a disposition to learn.

Play also builds self-esteem. Children are most receptive to learning during play and exploration and are generally willing to persist in order to learn something new or solve a problem. The experience of successfully working through something new or challenging helps kids gain the self-confidence required to engage in new experiences and environments.

And a big winner in play is Social development. Interpersonal skills like listening, negotiating, and compromising are challenging for 4- and 5-year-olds (as well as older kids and adults). Through play, children get to practice social and language skills, think creatively, and gather information about the world through their senses. Think about the games that students come up with on their own—they are creative, often intricate, and their “rules” always have to be negotiated.

Some educators regard the time kids spend socializing with their friends while gaming online as the salvation during the COVID-19 pandemic, or in any scenario where a child might experience barriers to in-person socialization. In addition to the social connections, there is an increased understanding that video games can actually improve kids’ remote learning. As educators we know that using student’s passions to engage them in learning is critical and kids love games. Done right, gaming and gamification of games can engage both intrinsic (pleasure and fulfillment) and extrinsic (recognition and rewards) motivation.

How Teachers Can Encourage and Promote Play-Based LearningTeachers help enhance play-based learning by creating environments in which rich play experiences are available. The act of being a teacher is recognizing the goals of education, understanding how learning works, and figuring out how to apply all this to each student, one at a time. Teaching children how to learn is a strong basis for every grade level.

Teaching children how to learn is a strong basis for every grade level.

It is pretty clear that students learn through play. Every child. Some use play to explore their world, others to gain language, and on and on and on. In fact, we have also seen that it is a natural impulse—like getting hungry, or crying when upset, children play. So why not lean into it? Find ways to increase the time spent on play in your class. Whether you create centers for dramatic play, bring in costume boxes, explore problem solving with board games, or design your own multiplication board game or even better, have your students design that game, lean in. Use what is part of a child’s fabric to enhance instruction and learning.

Looking for additional ideas to make your classroom a more hands-on learning environment for your young students? Check out this blog post on Exploring CTE at the Elementary Level Through Play for more outside-the-box inspiration!

Interested in learning more about play-based learning? Check out our OnDemand webinar where we explore this topic in-depth!

This post was originally published October 2019 and has been updated.

Playing to Learn | Harvard Graduate School of Education

Research Stories

By: Grace Tatter

Posted: March 11, 2019

Play and school can seem diametrically opposed. School is structured, often focused on order; play, by definition, is not.

But within this paradox of play and school, educators can find meaningful learning opportunities, advancing students' academic skills as well as the social skills that will allow them to thrive in adulthood and enjoy their childhood now, according to researchers from Project Zero (PZ), a research center at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

With support and collaborative input from the LEGO Foundation, Project Zero embarked on an exploration of the pedagogy of play in 2015, in partnership with the International School of Billund in Denmark, which has made play a key part of its approach to learning. Since then, researchers have looked at how play enlivens lessons in three schools in South Africa, as well. The goal is to understand, articulate, and advocate for the role of play in learning and schools.

Since then, researchers have looked at how play enlivens lessons in three schools in South Africa, as well. The goal is to understand, articulate, and advocate for the role of play in learning and schools.

In Denmark, playful learning has meant allowing middle school students to design their own schedules for two weeks, for instance; or students drawing a map of the world onto an orange. In South Africa, it looked like five-year-olds drawing words with the ‘er’ sound. Universally, a playful pedagogy allows students to experiment, use their imaginations, and be creative.

Widen Layout:

standard

There is a universality to play: children are often more relaxed and engaged during play, and it’s enjoyable — all aspects that facilitate learning. But there are also cultural specifications to what play looks like, when it’s appropriate, and who children play with.

The hope of the PZ researchers is that by observing playful learning and asking questions about its characteristics, they can work with educators to develop a pedagogy of play in their own contexts — a systematic approach to the practice of playful learning and teaching — that can weave through the tensions between school and play.

Here are some takeaways from their research thus far — and the questions that they, and other educators, are grappling with for the future.

It’s possible to play with a purpose. There is a difference between free play and playful learning. While both are important, a pedagogy of play is grounded in playing toward certain learning goals, designing activities that fit in and leverage curricular content and goals. Children are trusted to direct their own learning, but with appropriate supports from their teachers to meet specific goals.

While learning through play is universal, what that looks like depends on the culture. There is a universality to play: children are often more relaxed and engaged during play, and it’s enjoyable — all aspects that facilitate learning. But there are also cultural specifications to what play looks like, when it’s appropriate, and who children play with. In South Africa, Pedagogy of Play researchers and local researchers identified three South African indicators of play, centered around the concept of ubuntu, or a sense of human interconnectivity: ownership, curiosity, and enjoyment. In Denmark, that looked a little different. The indicators of play the researchers and educators identified were choice, wonder, and delight.

In Denmark, that looked a little different. The indicators of play the researchers and educators identified were choice, wonder, and delight.

Older students can benefit from play in the classroom, too. “Play is a strategy for learning at any age,” says PZ researcher Mara Krechevsky. While older students and their teachers might have more curricular demands than younger students, playful learning still has an important role to play — it might just look different. The kinds of activities that inspired a sense of ownership, curiosity, and enjoyment among older students in South Africa — like a debate over the nature of facts — might not qualify as play for younger learners.

“The commonality is this sense of playfulness — some sort of agency and sense of control over what you’re doing; some sort of curiosity; and that you’re enjoying yourself,” says PZ researcher Ben Mardell.

Widen Layout:

standard

“Play is a strategy for learning at any age.” – Project Zero's Mara Krechevsky.

And so can adults. “We want students to feel they have agency, and it’s really hard to imagine someone who doesn’t have agency instilling it in someone else,” Mardell says. “We need to provide teachers with that agency so they can take that back to their students.”

Again, what’s playful for a group of educators might look different than it does for children. In one study group of teachers in Denmark, the process of coming up with research questions to explore together felt like purposeful play.

But the PZ researchers do have at least one example of teachers participating in more childlike play: PZ researcher Lynneth Solis recalls how, at a school in South Africa, a group of teachers actually went out to play a game on the playground. “The idea was to bring themselves back to what it means to be a child, and what interactions are happening during play,” she says. During the game, the educators “realized they were bumping into each other, and it provided some insight that when children bump into each other during playtime it doesn’t mean they’re trying to hurt each other — it gave a little insight into the child’s experience. ”

”

Learn more

Project Zero has a dedicated blog to Pedagogy of Play. You can also find more resources at the International School of Billund site and at Project Zero, including the most recent Pedagogy of Play working paper, “Toward a South African Pedagogy of Play.”

Widen Layout:

standard

See More In

Early ChildhoodGlobal EducationK-12Learning and Teaching

- Any -ArtsCivics and HistoryCollege and CareerDiversity and InclusionEarly ChildhoodEducation PolicyGlobal EducationK-12Language and LiteracyLearning and TeachingMind and BrainParenting and CommunitySchool LeadershipSocial-Emotional WellbeingSTEM LearningStudents with Disabilities

Research Stories

5 Ways Educators Can Start Innovating

Project Zero authors show that making change doesn’t have to be daunting

By: Jill Anderson

Posted: August 20, 2021

Tagged: Early Childhood, K-12, Learning and Teaching

Research Stories

Playing in Uncertainty

The importance of outdoor, child-centered play in helping children manage unpredictability

By: Emily Boudreau

Posted: January 8, 2021

Tagged: Early Childhood, K-12, Parenting and Community, Social-Emotional Wellbeing

Artboard 113 Appian Way | Cambridge, MA 02138

©2022 President and Fellows of Harvard College

how good learning in games works - Gamedev on DTF

The modern industry is oversaturated with a variety of projects, many of which do not even require money for downloading. It costs nothing for the user to abandon the game at the very beginning and switch to another if the training tires him. And despite this, many studios seem to deliberately make tutorials lengthy and boring.

2504 views

Today we will tell you how to make a good training in the game that will keep the player. And also we will understand why even experienced teams do not always cope with this task.

Author: Denis Dudushkin

Annoying notifications

According to Sheri Grainer Ray, who has worked at Sony and EA, neither developers nor gamers like tutorial sections. The first do not like that their creation has to be postponed until the last moment. And it’s not always clear how meticulous the tutorial should be - after all, studio employees often think that the mechanics of their game are intuitive.

Producers, on the other hand, according to Ray, believe that training is not so important, so it makes no sense to allocate additional resources for it. As a result, a small part of the team with a limited amount of resources and time makes a nondescript and clumsy tutorial, which the player is already dissatisfied with.

As a result, a small part of the team with a limited amount of resources and time makes a nondescript and clumsy tutorial, which the player is already dissatisfied with.

Sometimes developers are aware of this, but continue to do things the same way. The situation with Far Cry is most indicative. The spin-off of the third part of Blood Dragon makes fun of one of the most annoying tricks in modern tutorials - pop-ups, that is, pop-ups that stop the gameplay so that you read something about the game mechanics.

"Press Enter to get rid of those annoying pop-ups"

The game parodies this trend by putting annoying pop-ups one after the other. However, a year later, the fourth part was released, which does almost the same thing, but in earnest.

So why do they keep putting pop-ups into games? As we wrote above, developers often postpone learning until the very last moment. For example, the NetherRealm studio had a little over three months to create a tutorial for Injustice 2. All because of the mechanics of the game, which changed until the release.

All because of the mechanics of the game, which changed until the release.

As a result, it remained to use universal and at the same time simple tools for teaching. Pop-ups are great for this because they are easy to incorporate into games and don't require context. And you don’t need to create complex sections with a thoughtful training design.

This is their key advantage and, at the same time, their disadvantage. Pop-ups are a simple but lazy solution. They pull the player out of the gameplay and destroy immersiveness. Good learning differs from bad learning precisely in the presence of context - the player is actively involved in the process.

You are probably expecting me to list a huge list of useful tools for good learning. But this is not necessary. In fact, everything is very simple and fits into one sentence: “Teach gradually through gaming experience.”

Nikolai Berbechee , Founder of the indie studio Those Awesome Guys

Learn gradually through play experience

Learning should be part of the gaming experience, both in terms of gameplay and narrative. A good example of this approach is Fallout 3.

A good example of this approach is Fallout 3.

Since at the very beginning we control the child, the episodes where the father teaches us to walk, shoot, use Pip-boy and even communicate with other people seem natural. They do not disrupt the natural flow of the game, but, on the contrary, create it.

Moreover, the developers tried to incorporate even the conventional RPG conventions into the game world. The player receives the first set of skills after a special test that all residents of the shelter pass.

Ideally, the tutorial should be as interesting as the rest of the game. To do this, you need to get rid of the elements that pull the player out of the context of what is happening. For example, cumbersome control schemes, as well as any canvases of text, complicate the learning process and do not allow you to enjoy the process.

The less text, the better. Super Mario Bros. or projects from Playdead (Inside and Limbo) create the illusion that there is no learning in the game at all. This, of course, is not so - in the same "Mario" a chain of coins in the shape of a parabola actually elegantly teaches the jump.

This, of course, is not so - in the same "Mario" a chain of coins in the shape of a parabola actually elegantly teaches the jump.

The more mechanics in the game, the more difficult it is for developers to refuse text hints - you still can't do without them, and this is normal. But the inscriptions need to try to make less annoying. Ideally, fit them into the aesthetics or world of the game.

For example, like in Braid - where text hints are sometimes inscribed directly into obstacles.

However, it is not always possible to get out this way. The more realistic the game, the more noticeable the conventions - like a training inscription on the wall. So, for example, Splinter Cell Conviction succinctly enters hints in suitable places for this, and, at the same time, makes the text inside the game part of its style.

But learning through experience is not a universal approach. It does not always work in games with complex and deep mechanics (like fighting or strategy games) or party games where no one wants to spend time learning. But for story projects, this approach is just right.

But for story projects, this approach is just right.

Safety

Immersiveness does not guarantee that the player will like the tutorial. Good learning should also be safe.

For example, in Half-Life 2, when the player is shown that zombies can do damage by throwing objects, the hero is between two bars to hide behind.

But in the second part of The Witcher, the prologue was greatly overcomplicated. From the start, the developers threw several opponents at Geralt and, in addition to this, taught the player to run away from the dragon - such mechanics are not even used in the future. For this, many players over the years have remembered the developers with an unkind word. Steam statistics clearly show why it is not necessary to do this - only 52% of the players made it to the first act of the game.

Naturalness

Tutorial should fit well into context and gameplay. After all, most often we miss the initial sections of the game, when we seem to be forcibly led by the hand.

It feels very comical in the first part of Dead Space. The player first sees a warning written in blood: "shoot off the limbs". Elegantly and logically explained how to most effectively kill Necromorphs.

But then the game pops up with the same information. In the same place, the player finds an audio diary where a spaceship employee advises colleagues to shoot at the limbs. Then comrades contact the main character to report the same thing. And finally, after the dialogue, another pop-up reminds you where to shoot. All this game throws out in a matter of minutes.

Even though the developers have never taken the player out of context, the episode still doesn't work - because it looks like they think he's a fool. On the other hand, shooting limbs is not just an important, but a key mechanic for the game. Developers must be sure that absolutely all players without exception will understand where to shoot.

Could it have been done better? Undoubtedly. For example, the kinesis module from Dead Space 2 - it allows you to move objects at a distance. In the first part, the hero picks it up from the corpse and an audio message with a detailed description of the device's operation is turned on. In the second part, they give you a look at the action of kinesis from the side, and then make you use it right away - you can use it to break a window to get into the next room.

In the first part, the hero picks it up from the corpse and an audio message with a detailed description of the device's operation is turned on. In the second part, they give you a look at the action of kinesis from the side, and then make you use it right away - you can use it to break a window to get into the next room.

Episodes with new mechanics for the player can be woven into context so carefully that they will not be inferior to the rest of the game.

In Ravenholm from Half-Life 2, the developers created a gameplay situation to explain to players how to kill zombies with a gravity gun and a circular saw.

At some point, the hero will have to go through a narrow opening, which is blocked by several disk blades. As soon as the player pulls one of them to pass, the script is activated and a zombie comes out from around the corner ahead. The player automatically shoots him. Unlike Visceral Games, Valve did not use pop-ups, audio messages, or text.

There are many such training sections in the game, but the developers never take control from the player and do not point to the training literally. Although this is a risky approach, it does not guarantee that the player will learn all the necessary mechanics.

Although this is a risky approach, it does not guarantee that the player will learn all the necessary mechanics.

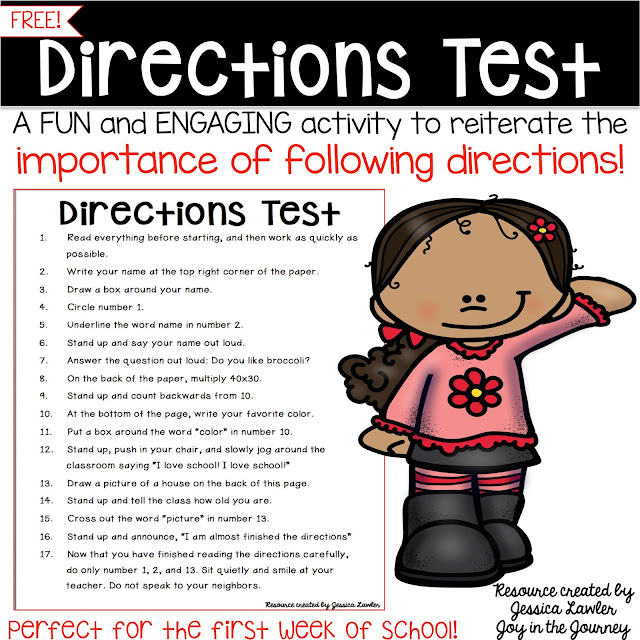

Teach only what is necessary

Any training can be simplified if you know the target audience. It's easier for players familiar with the genre. For example, shooter fans know not only about walking on WASD and running on Shift, but also about throwing grenades on G, and interacting with objects on E. It is better to keep this layout to make life easier for yourself and the players.

Former UX specialist at Epic Games, Celia Hodent, noted that for effective learning, you need to know how the brain perceives, processes and stores information. In the article about the attention of the player, we already talked about this.

In a simplified form, obtaining information works like this: first, the brain reads something with the senses, then the information enters the working (short-term) memory, after which it gets to the long-term memory, if you're lucky.

It is important to remember that learning is primarily a process of memorization. Therefore, Celia Hodent recommends paying attention to two points.

First, the brain does not have to make an effort to remember if it encounters something familiar. For example, in the world around things with handles on the sides instantly create an intuitive feeling that they can be taken in hand. Developers take the same into account in games. This is called the affondance of objects - or "expected assignment".

Game design has developed standards that evoke certain reactions in players. For example, red means no access or danger, while the glow of an object indicates interaction with it. In fact, the control layout is the same unique affordance for gamers.

Red spikes effectively warn of danger

Repeatability, value, context

The second useful learning mechanism is related to the transfer of information from short-term memory to long-term memory. According to studies, if you do not fix information in memory, then after 20 minutes it will be forgotten by 40% of people, and in a day - already 70%. This is called the forgetting curve. To avoid this, repetition is needed, as well as context and need.

According to studies, if you do not fix information in memory, then after 20 minutes it will be forgotten by 40% of people, and in a day - already 70%. This is called the forgetting curve. To avoid this, repetition is needed, as well as context and need.

The player needs to repeat about the existence of this or that mechanic. But there is no need to be zealous - it is enough to remind you several times at the beginning, and then less and less often. If you constantly fill the player's head with the same information, then the player will feel that he is being led by the hand.

The method was cleverly applied in God of War (2018) during the ax throwing tutorial. First, the player is offered to throw it in one of the battle scenes. After that, Kratos needs to solve a simple problem with this mechanic.

Then the intervals between episodes where the use of an ax is mandatory increase: first after ten minutes, then after twenty, and then even after half an hour. In between these episodes, the player is taught the combat system, rune mechanics, and optional ax throwing challenges. Thus, the developers immediately reward the players who quickly mastered the mechanics so important to the game.

In between these episodes, the player is taught the combat system, rune mechanics, and optional ax throwing challenges. Thus, the developers immediately reward the players who quickly mastered the mechanics so important to the game.

Celia Hodent Mechanics Reminder Model

In addition to repeatability, good learning needs context and need . Simply put, the player must subconsciously want to learn something.

This is not always taken into account in games where the player is asked to complete an obstacle course in a separate room. For example, in Bionic Commando, the player is locked in an abstract space, and even taught mechanics that are not available at the beginning of the passage.

But in Death Stranding this works well, because the player is taught new mechanics when they need it, but not before. Just imagine that the player was given various exoskeletons from the very beginning for efficient movement. It would not make sense, because heavy loads will appear later, which means the player would not realize the full value of the power-ups.

As a result, when you get tired of walking, they give you transport, and after a couple of difficult expeditions to the mountains, you will be happy to figure out how to build a cable car.

Material prepared by the XYZ Media team.

Our channels in Telegram and YouTube.

Why is learning through play the most effective? — T&P

As we found out last time, games create ideal conditions for a person to enter the most pleasant and creative state - that's why we like them so much. Can they be used not only for entertainment, but also for good?

There is only one school in the world that is completely built on the game model - it is called Quest to Learn and is located in New York. The school was opened with the support of the Bill Gates Foundation, and both teachers and game designers took part in its creation. In fact, children learn the subjects familiar to us: mathematics, history, geography, but the learning process itself is completely built on a gaming basis.

Instead of getting grades, there is a system of leveling up and earning titles. If there is a desire, children can take on additional missions to score points and increase their gaming status. The system of negative stress, when an unsuccessfully completed task leads to a low score, has been replaced by positive stress - you can always pick up new quests and try again to earn more experience points.

Periodically there are "boss battles" - two-week intensive sessions aimed at solving some task. Each student has his own role, you need to assemble the right team.

An internal social network, Being Me, has been developed, through which students can search for companions for team missions - just like in some online game like World of Warcraft.

Periodically there are "battles with the boss" - two-week intensive classes aimed at solving a certain task. Each student has his own role, you need to assemble the right team. This means that you don't have to be the best at math, you can specialize in your favorite subject and find a partner who loves math.

Reinforcing the learned material takes place in an unusual way - each student has a digital mentee who needs to be taught something. This is an excellent replacement for control tests, instead of being tested, the student himself gives the virtual character his knowledge, answers his questions and, if necessary, finishes learning something, fills in his gaps.

The main benefit of this approach is very clearly stated on the Quest to Learn website: "Students learn to be biologists, historians and mathematicians instead of studying biology, history or mathematics."

This is a key point that comes from the difference between the types of knowledge acquisition learning and education - in the first case, we learn to be specialists, and not just observers of how one or another specialty works. Unlike the traditional education system, games give us this opportunity now. This is also evidenced by the successful example of Lee Sheldon, who introduced experience points and an increase in levels for each student instead of a grading system.

Scientists conducting experiments in laboratories and a child playing in a sandbox are doing the same thing - knowing the world through experiments. "What if?" - this is the main question that drives both scientists and the child.

There is another opinion: Edward Castronova, an assistant professor in the Department of Economics at California State University and the author of the book Escape to the Virtual World, studied games in great detail, taking into account his professional experience. In his blog, he writes that game principles cannot yet be used in training. In the game, we accumulate experience through an infinite number of repetitions - in order to achieve mastery, we have as much time as it takes. During the lesson, everything is different: there are several tasks, time is limited, plus there is a teacher who evaluates your results after the time has passed. Moreover, the lesson cannot be perceived as a game, it should be taken more seriously.

Let's rewind time and start from the beginning: how does one learn something new? In his lecture on learning and play, Will Wright says that we can gain experience in only two ways: alone through toys (a toy car gives some idea of how the wheel works and why cars move on the streets) or by receiving information from others. people (parents explain how the same machines work). These are the basic techniques for teaching a person - a game and a story, narration. From the point of view of terminology, in English there are two separate words that reflect these two processes, in Russian this difference is not so noticeable. Learning is essentially self-learning, knowledge gained through knowledge of the world. And education is education, knowledge that someone gives.

The first way to gain knowledge is more natural - children can explore the world through the game without being able to speak long before they can perceive information from their parents in the form of a narrative. Scientists conducting experiments in laboratories and a child playing in a sandbox are doing the same thing - knowing the world through experiments. "What if?" - this is the main question that drives both scientists and the child.

Scientists conducting experiments in laboratories and a child playing in a sandbox are doing the same thing - knowing the world through experiments. "What if?" - this is the main question that drives both scientists and the child.

In contrast to the learning we are used to, when a positive result is encouraged by evaluation, games teach differently. And it's not about the grading system itself, as Lilya Brainis believes. Grades are a great way to motivate a student to improve in their field, but only on the condition that they have the right to make a mistake.

The main benefit of this approach is very clearly stated on the Quest to Learn website: "Students learn to be biologists, historians and mathematicians instead of studying biology, history or mathematics."

Failure in the game is also a success. You made a mistake, lost, but at the same time you have the opportunity to start anew, taking into account the experience gained. And every time you do it better and better.