Pretend play age

Stages of Play from 24–36 Months: The World of Imagination

Learn how infants and toddlers develop play skills from birth to 3, and what toys and activities are appropriate for their age.

From age 2 to 3, your toddler’s interests and skills are blooming at an amazing, almost dizzying rate! All the new things they can do—from walking and talking to figuring out how things work and beginning to make friends—are fuel for the imagination and creativity. This is a special time in your child’s life. Learn more about how infants and toddlers develop play skills. And don’t forget—YOU are still their most important playmate and toy!

Playing Pretend

Between 2 and 3, your toddler will use their growing thinking skills to play pretend. With props, like a doll and toy bottle, she will act out steps of a familiar routine—feeding, rocking, and putting a doll to sleep. As your toddler learns to use symbols, imaginary play skills will grow more complex. A round pillow, for example, can become a yummy pizza!

TOYS TO EXPLORE:

- Stuffed animals and dolls

- Accessories such as baby blanket, bottle for doll, etc.

- Toy dishes, pots and pans, pretend food

- Toy cars, trucks, bus, or train, with little people that fit inside

- Blocks

HELPING YOUR TODDLER PLAY AND LEARN:

- Let your child choose what to play, and then add on to his activity. If they have a toy bus, you might ask where it’s going or if they would like to pick up some people waiting at the bus stop.

- Give your child a block and say, “Do you want a piece of my birthday cake? It’s so yummy!” (as you pretend to munch on it). Do they understand the block can stand in for something else? If so, have a birthday party using the block as a cake, sing a birthday song, pretend to blow the candles out, and “cut” a slice to eat.

Solving Problems Through Play

Sorting toys—putting cars in one basket and balls in another—is just one way that your toddler is solving problems using thinking skills. You may also see them try one puzzle piece in different spaces, or turn it around to see if it fits. Your child is now also using tools (like a stick) to solve problems (how to reach a toy under the couch).

Your child is now also using tools (like a stick) to solve problems (how to reach a toy under the couch).

TOYS TO EXPLORE:

- Chunky puzzles

- Memory-type games

- Stacking cups or ring stacks

- Shape-sorters and bead mazes

- Toys that can be activated—like cars that roll forward when you pull them back

HELPING YOUR TODDLER PLAY AND LEARN:

- Make your own Memory game using photos of family members. Print out two copies of 10 photos, glue each photo to an index card. Place them face up on the floor and see if your child can find the matches.

- Turn cleaning up into a sorting game. Take photos of your child’s different toys and tape them to the basket or box where they belong. Show your child how to sort her toys. Before you know it, they’ll be an expert at the “clean-up game”!

Now You’re Talking!

Toddlers are learning new words by the day! Most are using two-word phrases (“what that”) and by age 3, some three-word phrases (“Josie want cookie!”). Toddlers can now follow two-step requests such as “Please get your hat and put it on.” Two-year-olds can also understand stories. They can now connect the words you say with the illustrations.

Toddlers can now follow two-step requests such as “Please get your hat and put it on.” Two-year-olds can also understand stories. They can now connect the words you say with the illustrations.

TOYS TO EXPLORE:

- Board books

- Songs and fingerplays

- Dolls

- Child-safe mirror

HELPING YOUR TODDLER PLAY AND LEARN:

- During bath-time, ask your child to wash his nose and belly. Then ask them to wash his doll’s nose and belly. Look in a mirror together and name the different parts of your faces—eyes, nose, mouth, ears, and more.

- Read together. If your toddler is wiggly, ask them to do the actions on the page—hopping like the frog or dancing like the little mouse. Ask questions, too: “What do you see on this page?” or “Do you see a moon?”

Fantastic Fingers

Your toddler is now able to use his hands and fingers to pick up food, small toys, and more. They may even hold a crayon using his thumb and pointer finger, instead of their fist. Toddlers are learning to control the strokes they make with crayons and markers.

Toddlers are learning to control the strokes they make with crayons and markers.

TOYS TO EXPLORE:

- Foam or wooden blocks, plastic interlocking blocks, or bristle blocks

- Chunky puzzles

- Pull-toys, stringing beads, and pop-beads

- Washable crayons and markers

HELPING YOUR TODDLER PLAY AND LEARN:

- Tape paper to your child’s high chair or to the table and let your child explore with crayons and markers. Watch them scribble away! See if they want to imitate making a line or circles that you draw first. But don’t worry if they have their ideas about what she wants to draw—or how to draw it.

- Play with play-dough. Practice rolling the dough, poking holes in it, or making little balls of dough and dropping them in a small cup to dump out. Older toddlers still like fill-and-dump activities—plus this lets them use their hands and fingers to explore and create.

The 5 Stages of Pretend Play in Early Childhood

- Share

Throughout early childhood, children engage in many types of play that are all equally important for their development. One of these is pretend play, also known as imaginative, make-believe or fantasy play.

One of these is pretend play, also known as imaginative, make-believe or fantasy play.

Children typically progress through 5 stages of pretend play.

Pretend play may appear to just be a child imitating what they see around them and how others are behaving, but it stimulates a great deal of creativity and thinking skills.

When children act out their world together, they engage in cooperative behaviour as they work together to create a fantasy scene. This involves high levels of social skills.

They also develop emotionally as they act out life scenarios that are full of emotions and new experiences. Playing gives them a safe space to experience these big emotions.

Here are the 5 stages of imaginative play in early childhood:

1. Enactive Naming

The first phase of pretend play is called enactive naming. In this stage, a child is not yet actively “pretending,” rather she is showing the knowledge she has.

For example, the first time she puts an empty spoon or cup to her mouth, she may be imitating a behaviour she has seen, or acting out her understanding of the objects, but she is not yet playing.

She is beginning to learn the difference between real and not real.

Young children love to imitate the actions and behaviours they see around them and may also want to sweep the floor, whether with a real broom or a toy broom.

2. Autosymbolic Schemes

In the second stage, called autosymbolic schemes, the young child begins to display the first signs of pretending, but only in relation to herself. This starts around the age of 12 months.

A child may pretend to lie down and sleep or take a pretend sip from their cup while making noises to show she is drinking.

At this stage you will see that the child is intending to play by her mannerisms and actions – she may smile or look at you to show you that she is pretending.

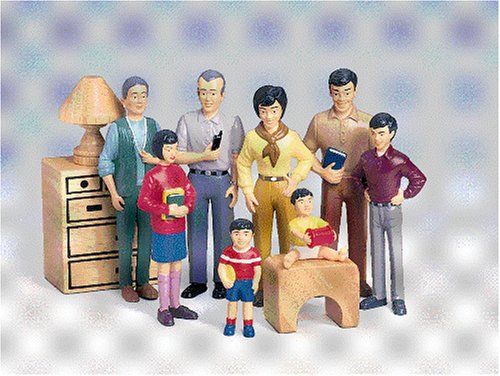

Playing with toy replicas of household objects is fun for young toddlers, and by using these items for their correct functions, they show their growing cognitive skills.

At some point, the young child will start to engage in pretend play by using objects to represent other objects. This is called symbolic play.

This means a child who wishes to pretend to talk on the phone, may reach for a block instead of a real phone or a toy that represents the real object.

The child feels that the block shares some characteristics with a phone – perhaps the size and the shape – and it becomes a good replacement for the phone.

This kind of symbolic pretend play shows yet another layer of advanced thinking.

Pretending while playing is rooted in a child’s social development. Their interactions with parents, family, peers and other caregivers forms the basis of their play, and forms the foundation for their cognitive development.

3. Decentred Symbolic Schemes

Between the age of 12 and 24 months, a child will begin to involve others in her pretend play.

She will pass you the cup to take a sip from or try to feed you with an empty spoon. This shows that she is becoming aware of others as being separate from herself.

From around 2 years of age, toddlers often begin to play with dolls. They see their dolls as living beings, with feelings and states, such as hunger and tiredness.

This behaviour shows a huge leap in a child’s thinking skills as she matures.

It is also believed that the advanced thinking shown during pretend play is not yet seen in other aspects of a child’s life at this young age.

During this type of play, a child knows she is pretending and knows that the other child is pretending, and that they are both attaching mental concepts to their scenario.

This type of awareness is unusual as children typically see everything from an egocentric viewpoint.

During pretend play; however, they are able to experience something from someone else’s shoes and even try out different points of view.

Children also show that while engaging in symbolic play they are able to assign two separate identities to an object – such as understanding that a block is a block, and in this case, also a phone.

This is something they are not able to do in other contexts, for example when looking at pictures of objects that represent other objects.

To give an example of this in a language context – a very young child knows that a banana is a banana, but will not also refer to it as a fruit.

Pretend play, therefore, plays a big role in helping a child develop thinking skills.

Even the objects that a child uses to play with show her level of thinking. In the beginning, she uses real objects, then toy replicas, then other objects as representations.

The older a child gets, the more she can use non-realistic toys in her play, with her imagination being the only thing she needs.

4. Sequencing Pretend Acts

In this stage, a child learns to apply a logical sequence to her pretending. If she wants to give her doll a bath, for example, she will take off her clothes before doing so.

If she wants to give her doll a bath, for example, she will take off her clothes before doing so.

The child has learned through observing others and how people behave in various contexts and is strengthening her memory skills, so that this knowledge can be used later, in a play context.

5. Planned Pretend

In this final stage, known as planned pretend, a child will collect props and items that she needs for her pretend play.

She will have a specific idea in mind for what she wants to act out and will plan accordingly. She may pretend to be a teacher giving a lesson, or a mother taking her child to the shops.

Preschoolers are usually in this stage of pretend play and they use high-level social skills while engaging.

They need to communicate well, play a specific role, allow others to play their roles, share and take turns, and follow the agreed rules, as they play with a common goal.

Sometimes this requires compromising, negotiating and persuading.

Read more about the types of play in early childhood.

Source:

Natanson, J. 1998. Learning Through Play: A parent’s guide to the first five years. Tafelberg Publishers Limited: Cape Town.

Get FREE access to Printable Puzzles, Stories, Activity Packs and more!

Join Empowered Parents + and you’ll receive a downloadable set of printable puzzles, games and short stories, as well as the Learning Through Play Activity Pack which includes an entire year of activities for 3 to 6-year-olds.

Access is free forever.

Signing up for a free Grow account is fast and easy and will allow you to bookmark articles to read later, on this website as well as many websites worldwide that use Grow.

- Share

Games for preschoolers.

Types and description

Types and description Each child's age corresponds to characteristic game forms and actions. And this is understandable, since with the help of the game the child discovers and learns the world, and with the acquisition of new knowledge and skills, the ways of mastering the world change. At first, the child plays with the things around him directly with his hands, mouth and body. Later, he finds increasingly abstract ways to study objects and events. During symbolic play, the child begins to replace things with the help of other objects. In role play, the child is already taking on different roles. In the collective children's game, real life is imitated, since everything takes place on an abstract playing field. A child's play can be divided into phases that build on each other. It also helps to understand how developed the child is. At the same time, the concept of "already" is much more important than the concept of "still". And if a child plays role-playing games at an early age, then there is progress in his development.

But at the same time, a sign of developmental delay is not that the child needs more time than usual to enter this process. The secret of the game lies in the fact that we can enjoy the game for a long time, the important phases of which, it seems, have long been passed. Adults can also experience joy during symbolic or role play. And that's great, because that's why we, as educators, can immerse ourselves with children in their play world, without having to pretend.

Consider three play forms created for young children.

1. Functional game:

everything starts with understanding

Children from the first year of life during the game literally take matters into their own hands. With a sure grip, and also, of course, with lips and tongue and, if possible, with the whole body, they explore around them all the things that they can reach. At first it seems that such a study has no system: young children, as a rule, first try what can be done with a thing, under the motto “Something can be done with this!”. And at some point they begin to understand that, for example, if you shake a rattle, you can make a sound. If you lick a metal rod, you get an interesting taste sensation. If you hit the heating battery with a cube, it rattles. If you press the desired button, the CD player starts making noise. And if certain objects are thrown off the table, they burst or scatter into pieces, and the reaction of adults to this follows, well, very interesting ... So the child notices that all his actions cause the reaction of others. Again and again, the baby joyfully states that he made this discovery in the process of studying the functioning of things.

And at some point they begin to understand that, for example, if you shake a rattle, you can make a sound. If you lick a metal rod, you get an interesting taste sensation. If you hit the heating battery with a cube, it rattles. If you press the desired button, the CD player starts making noise. And if certain objects are thrown off the table, they burst or scatter into pieces, and the reaction of adults to this follows, well, very interesting ... So the child notices that all his actions cause the reaction of others. Again and again, the baby joyfully states that he made this discovery in the process of studying the functioning of things.

Therefore, this form of play is called "functional play". Many game patterns, such as letting an object fall, take it apart, and move it to another place, are understood as varieties of functional play.

In the functional game, the child plays in most cases with himself and with a thing from which he tries to "lure" a function. As for other children, he plays next to them rather than with them. In the irritated cry of those from whom he takes something away, in a smile as a reaction to affection or in a greeting gesture of the hand - in all this a small child sees the function he has evoked and is satisfied with the realization that he already knows how to evoke an emotional response from adults.

In the irritated cry of those from whom he takes something away, in a smile as a reaction to affection or in a greeting gesture of the hand - in all this a small child sees the function he has evoked and is satisfied with the realization that he already knows how to evoke an emotional response from adults.

2. Symbolic game:

act as if...

Big eyes look at us adults. Whatever thing we pick up, whatever daily action we perform, a small child is watching us. He explores the things that surround him and tries to attribute meaning to them: for example, they eat with the help of a plate and a spoon. With the help of a car, you can move in space, and a hat is needed in order to put it on your head. The progressive development of the child's motor skills at the end of the first and beginning of the second year of life gives him the opportunity to repeat the actions he has seen in the game. So, for example, a child feeds a doll a cube, which in his mind becomes a spoon or bread. The sand in the sandbox becomes a pie, and the bucket becomes a saucepan. Symbolic play is a form of play focused on oneself. The child expresses in the game his individual idea of the world and checks that he has already learned about it. Emotional experience is symbolized in exactly the same way as the result of actions. Children play, as a rule, by themselves or next to each other.

The sand in the sandbox becomes a pie, and the bucket becomes a saucepan. Symbolic play is a form of play focused on oneself. The child expresses in the game his individual idea of the world and checks that he has already learned about it. Emotional experience is symbolized in exactly the same way as the result of actions. Children play, as a rule, by themselves or next to each other.

There is practically no agreement between them. Play material is not shared, everyone needs their own toy and play space.

Only those who are completely confident in themselves can share their toys with others. This usually occurs towards the end of the second year of life and if elements of role play are observed at an early age.

3. Role play:

I also want to be a child

With the transition to the third year of life, the child begins to interact with other children. The game action expands: just now Maria was just feeding her doll, and now she is already beginning to be interested in Max, who is busy washing dishes in the doll's kitchen. She walks over to him and starts placing the washed dishes on the table. Max does not agree with this: after all, these are his plates.

She walks over to him and starts placing the washed dishes on the table. Max does not agree with this: after all, these are his plates.

A few weeks later, both discuss the game plan: “I cook food, and you sit at the table and eat!” Such small arrangements among themselves are new for both children. In this life phase, their social abilities develop rapidly. More recently, they have learned that there is a difference between "I" and "you". And now they are starting to play together. The first cases of playing mother-daughter are observed already at toddler age.

Adaptation Interaction with family Children's Initiative Children's typography Children's advice Didactic guide Distance learning Plastic bottle toys Games ICT Individual approach Inclusion Innovation platforms Correctional work MATE:PLUS Maths Mathematical development media pedagogy Modeling Music Musical development Partial program Educational psychologist Pedagogical support Pedagogical observations Initiative support cognitive development Portfolio Projects Psychological support Development environment Child development Early development Speech development Speech: plus Role-playing game RPPS symbolic game Cooperation Socialization Wednesday Early childhood play patterns Thematic cards Technical education Technology Teacher speech therapist Physical development functional game Artistic and aesthetic development Digital environment Chess Heuristic learning Experiments Nursery

Myths about child-centered play therapy //Psychological newspaper

I am sincerely grateful to my parents who believed in me as a play therapist before I realized for myself that the chosen direction of work gives me the opportunity to help children cope with problems. Perhaps these parental expectations partly "made me" as a professional. It was they, loving fathers and mothers, who left their children behind closed doors with me, trusting to come into contact with the soul of the child. It is they, the parents, who found out that we used class time to launch paper airplanes, watch how colorful threads of paint mix and intricately intertwine in a glass of water, talk about cartoons, play with bakugan, robots, wooden cubes, crumple paper so that it looks like old maps, continued to take the children to the sessions and had the patience to see the first results - a change in the behavior and / or internal state of the child.

Perhaps these parental expectations partly "made me" as a professional. It was they, loving fathers and mothers, who left their children behind closed doors with me, trusting to come into contact with the soul of the child. It is they, the parents, who found out that we used class time to launch paper airplanes, watch how colorful threads of paint mix and intricately intertwine in a glass of water, talk about cartoons, play with bakugan, robots, wooden cubes, crumple paper so that it looks like old maps, continued to take the children to the sessions and had the patience to see the first results - a change in the behavior and / or internal state of the child.

Along with trust, of course, I sometimes feel the opposite attitude: skepticism, irony, doubts. Here are some parenting myths (or misconceptions) about the child-centered play therapy process and the play therapist himself. I also offer my "refutations" of these myths. I think it is important to do this - the more aware of the approach the parents have, the less the work started will be interrupted, the more children will be able to take full advantage of the rich possibilities of child-centered play therapy.

1. The play psychotherapist knows what is behind each play action by the child, behind each of his statements. In fact, the specialist cannot read the mind of the child and cannot interpret his every action. Another thing is that he tries to understand “what the child is playing about”, and is very attentive to his actions and words.

2. The play therapist knows why my child behaves the way he does and should always be able to explain to me why he, the child, does it. In fact, the specialist builds a working hypothesis, comprehends the motives of the child's behavior, but does not solve his behavior as a rebus, in which each action has one unambiguous meaning and reason.

3. The play therapist has a plan for each play session. Otherwise, why is he needed at all as a specialist? In fact, child-centered play therapy does not involve directed "treatment" of this or that symptom. The task of a specialist is to create conditions for the child to be able to use his own internal resources to the maximum for development, restoration and harmonization. It seems surprising, but the child, under appropriate conditions, literally "outlives" his symptoms.

It seems surprising, but the child, under appropriate conditions, literally "outlives" his symptoms.

4. Play therapy implies permissiveness. Play therapy involves the freedom of expression of the child, as well as the observance of a number of restrictions.

5. The play psychotherapist may not remember the rules of the Russian (English) language, multiplication tables, he has no speech therapy training - he does not correct my child's mistakes. In fact, the play psychotherapist has his own professional tasks, which he implements during interaction with the child. The game psychotherapist should not correct the child's mistakes, performing the functions of a teacher, speech therapist, defectologist that are not characteristic of him.

6. The play therapist is good at pretending to be interested in sandboxing, talking about computer games, and playing with dolls. In fact, it is interesting for a good play therapist to share with the child his ways of expressing himself in a play session.

7. The play psychotherapist knows some tricks, thanks to which my child rushes to his classes as if they were smeared with honey. In fact, the atmosphere of full acceptance by an adult specialist of all the feelings of the child and the possibility of freedom of expression attracts many children, in contrast to the requirements of ordinary life, where they must always comply with established standards.

8. The play therapist says that he does not conduct psychological diagnostics with the help of tests - he is probably too lazy or he is not confident in his abilities. In fact, a play therapist, if necessary, can refer a child for diagnostics and can cooperate with various specialists - a neurologist, a neuropsychologist, a psychiatrist. The function of a play psychotherapist does not really include the task of conducting standardized diagnostic procedures.

9. The play therapist says that the child's behavior during the sessions is diagnostic and that one or two meetings cannot give a clear picture of what is happening - probably, he specifically wants to extend the time of work in order to get more money. The play therapist, indeed, constantly monitors the behavior of the child and collects a lot of diagnostic material during work. And while there is a need for this work, he has something to “diagnose” (without conducting tests).

The play therapist, indeed, constantly monitors the behavior of the child and collects a lot of diagnostic material during work. And while there is a need for this work, he has something to “diagnose” (without conducting tests).

10. Playing with toys can slow down my child's intellectual development. It seems that he seems to be getting younger in these classes. In fact, during play sessions, a child may regress to an earlier age. This is a temporary phenomenon that allows the child to return to the early stages of development and "live" them again, getting rid of the corresponding problems. In addition, the game itself activates creativity and imagination, which has a beneficial effect on the cognitive abilities of the child.

11. The play therapist insists that the parents also come to see him regularly. Looks like he wants to make more money. In fact, communication between a play therapist and parents helps him to better understand what is happening with the child.