Print knowledge definition

Print Awareness: An Introduction | Reading Rockets

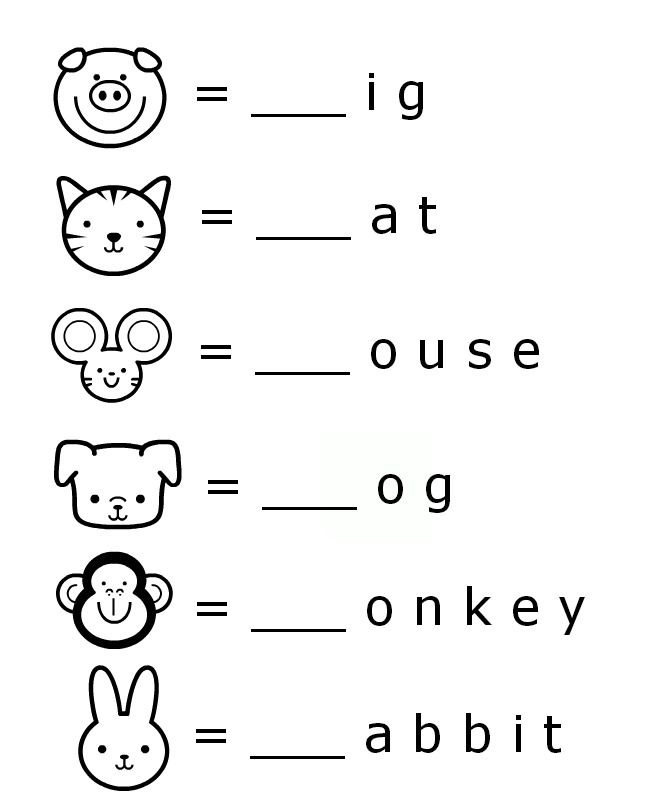

Children with print awareness can begin to understand that written language is related to oral language. They see that, like spoken language, printed language carries messages and is a source of both enjoyment and information. Children who lack print awareness are unlikely to become successful readers. Indeed, children's performance on print awareness tasks is a very reliable predictor of their future reading achievement.

Most children become aware of print long before they enter school. They see print all around them, on signs and billboards, in alphabet books and storybooks, and in labels, magazines, and newspapers. Seeing print and observing adults' reactions to print helps children recognize its various forms.

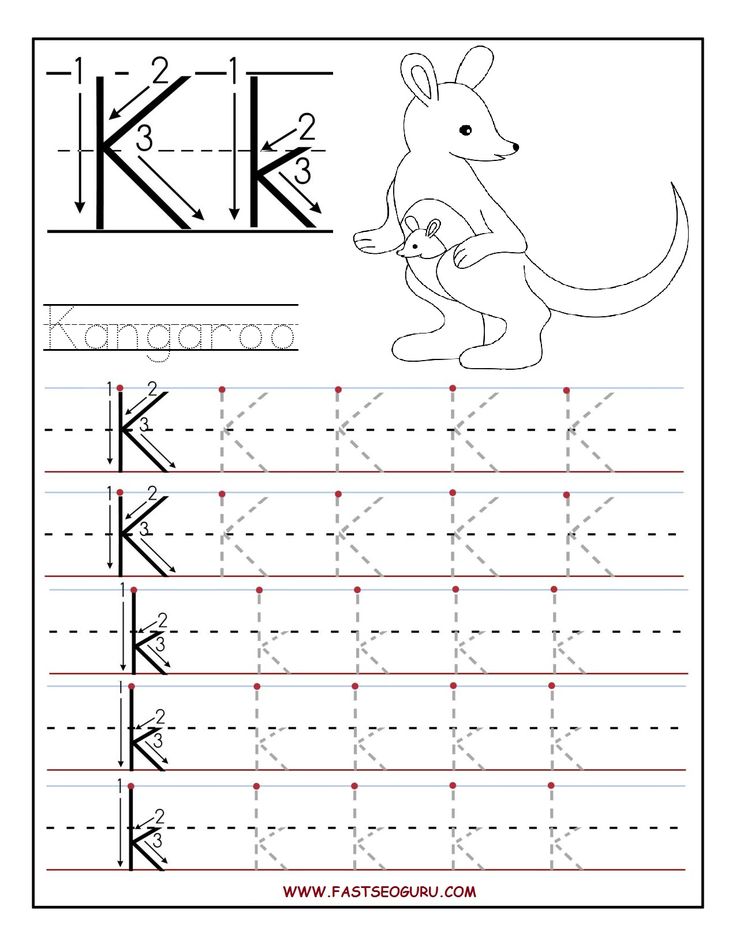

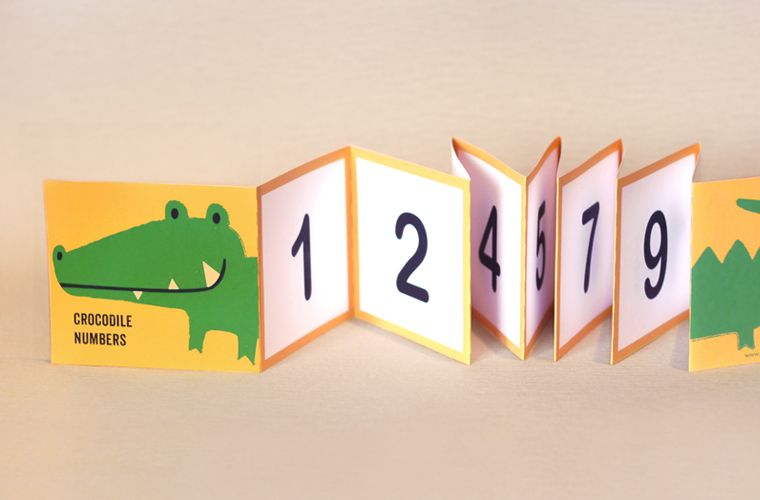

The ability to understand how print works does not emerge magically and unaided. This understanding comes about through the active intervention of adults and other children who point out letters, words, and other features of the print that surrounds children. It is when children are read to regularly, when they play with letters and engage in word games, and later, when they receive formal reading instruction, that they begin to understand how the system of print functions; that is, print on a page is read from left to right and from top to bottom; that sentences start with capital letters and end with periods, and much, much more.

As they participate in interactive reading with adults, children also learn about books author's and illustrators names, titles, tables of content, page numbers, and so forth. They also learn about book handling how to turn pages, how to find the top and bottom on a page, how to identify the front and back cover of a book, and so forth. As part of this learning, they begin to develop the very important concept "word" that meaning is conveyed through words; that printed words are separated by spaces; and that some words in print look longer (because they have more letters) than other words.

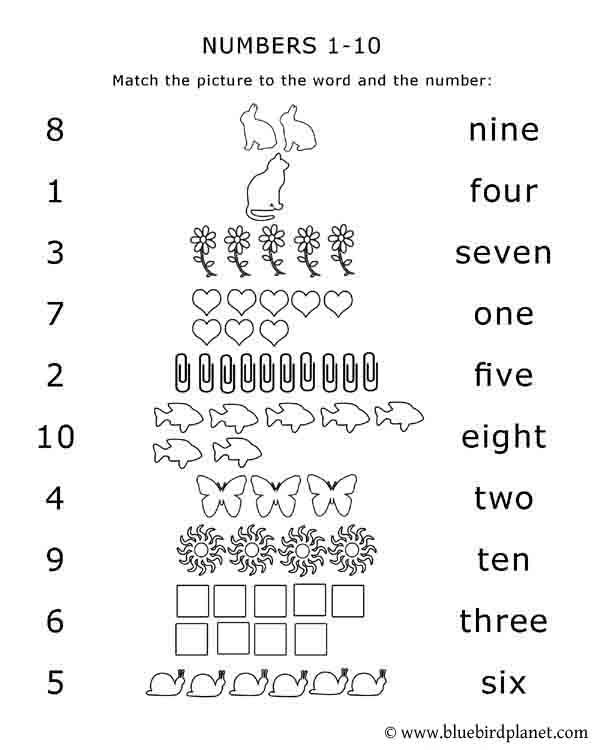

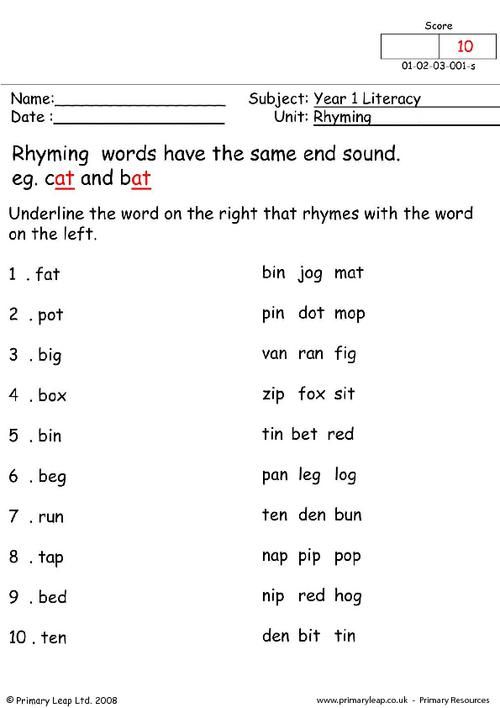

Books with predictable and patterned text can play a significant role in helping children develop and expand print awareness. Typically these books are not decodable that is, they are not based on the sound-letter relationships, spelling patterns, and irregular/high frequency words that have been taught, as in decodable texts. Rather, predictable and patterned books, as the names implies, are composed of repetitive or predictable text, for example:

Typically these books are not decodable that is, they are not based on the sound-letter relationships, spelling patterns, and irregular/high frequency words that have been taught, as in decodable texts. Rather, predictable and patterned books, as the names implies, are composed of repetitive or predictable text, for example:

Two cats play on the grass.

Two cats play together in the sunlight.

Two cats play with a ball.

Two cats play with a toy train.

Two cats too tired to play.

Most often, the illustrations in such books are tied closely to the text, in that the illustrations represent the content words that change from page to page.

As they hear and participate in the reading of the simple stories found in predictable and patterned books, children become familiar with how print looks on a page. They develop book awareness and book-handling skills, and begin to become aware of print features such as capital letters, punctuation marks, word boundaries, and differences in word lengths.

Awareness of print concepts provides the backdrop against which reading and writing are best learned.

Concepts of Print Assessment | Reading Rockets

By: Reading Rockets

An informal assessment of the concepts of print, including what the assessment measures, when is should be assessed, examples of questions, and the age or grade at which the assessment should be mastered.

All assessments should be given one-on-one.

What it measures

If a student understands:

- That print has meaning

- That print can be used for different purposes

- The relationship between print and speech

- There is a difference between letters and words

- That words are separated by spaces

- There is a difference between words and sentences

- That there are (punctuation) marks that signal the end of a sentence

- That books have parts such as a front and back cover, title page, and spine

- That stories have a beginning, middle, and end

- That text is read from left to right and from top to bottom

When should it be assessed?

Assess concepts of print twice during kindergarten, at the start of school and at mid-year. In addition, as you model story reading techniques to help guide instruction, identify students who need additional support, and determine if the pace of instruction should be increased, decreased, or remain the same.

In addition, as you model story reading techniques to help guide instruction, identify students who need additional support, and determine if the pace of instruction should be increased, decreased, or remain the same.

Examples of assessment questions

Give the student a book and ask the following questions:

- Can you show me:

- a letter?

- a word?

- a sentence?

- the end of a sentence (punctuation mark)?

- the front of the book?

- the back of the book?

- where I should start reading the story?

- a space?

- how I should hold the book?

- the title of the book?

- how many words are in this sentence?

Age or grade typically mastered

Some students enter kindergarten with an understanding of print concepts, but other will master it as the school year goes on.

See also this concepts of print assessment from Michigan's Mission: Literacy.

Reading Rockets (2004)

Reprints

You are welcome to print copies or republish materials for non-commercial use as long as credit is given to Reading Rockets and the author(s). For commercial use, please contact [email protected]

For commercial use, please contact [email protected]

Related Topics

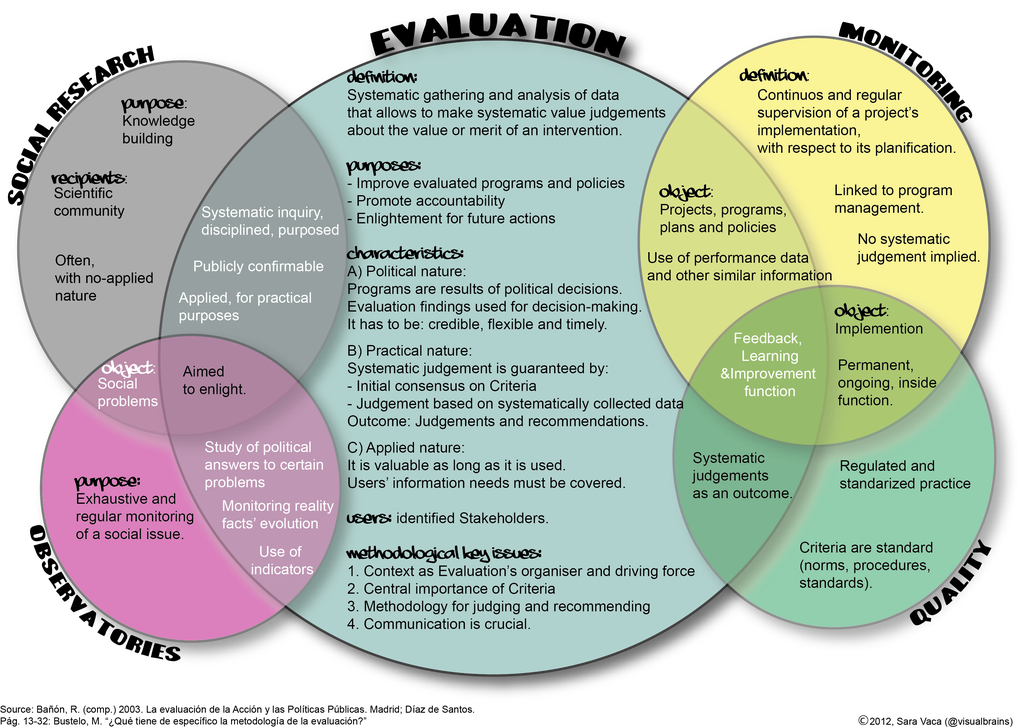

Assessment and Evaluation

Early Literacy Development

Print Awareness

New and Popular

Print-to-Speech and Speech-to-Print: Mapping Early Literacy

100 Children’s Authors and Illustrators Everyone Should Know

A New Model for Teaching High-Frequency Words

7 Great Ways to Encourage Your Child's Writing

Screening, Diagnosing, and Progress Monitoring for Fluency: The Details

Phonemic Activities for the Preschool or Elementary Classroom

Our Literacy Blogs

Shared Reading in the Structured Literacy Era

Kids and educational media

Meet Ali Kamanda and Jorge Redmond, authors of Black Boy, Black Boy: Celebrating the Power of You

Get Widget |

Subscribe

Item of Knowledge - Semyon Ludwigovich Frank

Semyon Ludwigovich Frank

Download

epub fb2 pdf Original: pdf26Mb

Foreword

Part one. Knowledge and being Chapter 1. The subject and content of knowledge Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4. Consciousness and being. The concept of absolute being Part two. Intuition of unity and abstract knowledge Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9. Intuition and abstract meaning Part three. Concrete unity and living knowledge Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Appendix. On the history of ontological proof

Knowledge and being Chapter 1. The subject and content of knowledge Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4. Consciousness and being. The concept of absolute being Part two. Intuition of unity and abstract knowledge Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9. Intuition and abstract meaning Part three. Concrete unity and living knowledge Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Appendix. On the history of ontological proof

Preface

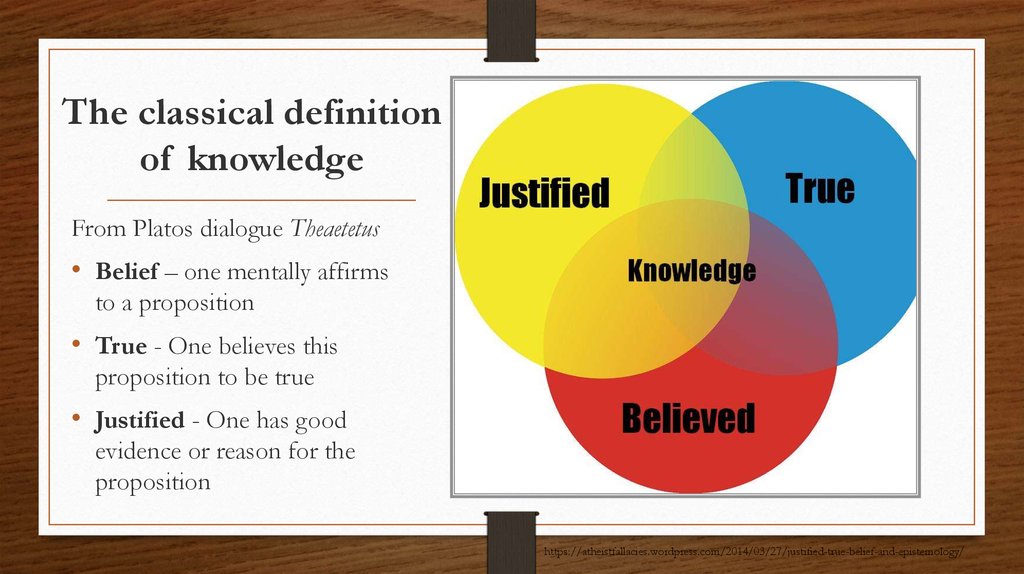

The proposed book is devoted to the study of the subject of knowledge, that is, it is an attempt to resolve the basic epistemological question of the nature and conditions of the possibility of knowledge. For us, however, this question is inseparably intertwined with another, perhaps even older and, at the same time, newly put forward in modern philosophy question - the question of the meaning and limits of knowledge expressed in concepts. This knowledge, which in former times it was customary to call, according to its supposed psychological source, "rational" and to oppose knowledge by means of "reason", we prefer to characterize it purely logically and call it abstract knowledge.

At first glance, it may seem that the epistemological problem has no more connection with this question than with any other question of logic. All our research tries, on the contrary, to show that these are not two questions, but one and the same question, only taken from two different sides. Knowledge is necessarily knowledge about the object, i.e., the disclosure for our consciousness of the contents of the object as "a being that exists independently of our cognitive attitude towards it; we are trying to establish this exact concept of knowledge in spite of all attempts to circumvent or modify it. But if so , then knowledge must be preceded by that primary relation potential possession of an object, outside of which cognition and knowledge are just as inconceivable as the conscious realization of any goal without anticipating this goal is impossible, or as no activity is possible on an object that we do not have at hand. We try to show that this primordial possession of an object, which precedes any turning of consciousness to an object, is possible only if the subject and object of knowledge are rooted not in any consciousness or knowledge, as is commonly thought, but in absolute being, as the primary unity directly and inalienably present in us and in us, on the basis of which a split between the cognizing consciousness and its object is possible for the first time. This is the conclusion of the first part of our study. But since the difference between the object itself and the content of knowledge about it is preserved even in already realized knowledge - although the known content is the content of the object itself - we obviously distinguish and thereby know the object in that in which it differs from the content. knowledge. This would be, however, completely impossible, because it is contradictory, if we did not have the right to distinguish between two kinds of knowledge - knowledge about object from knowledge, identical with the possession of the object itself. And here it is revealed that knowledge expressed in a judgment by means of concepts, what we call abstract knowledge always has its object outside itself and, reaching the content of the object itself, at the same time is not the true possession of the object , but gives only a secondary reproduction of it in the reflected, lower sphere of concepts.

This is the conclusion of the first part of our study. But since the difference between the object itself and the content of knowledge about it is preserved even in already realized knowledge - although the known content is the content of the object itself - we obviously distinguish and thereby know the object in that in which it differs from the content. knowledge. This would be, however, completely impossible, because it is contradictory, if we did not have the right to distinguish between two kinds of knowledge - knowledge about object from knowledge, identical with the possession of the object itself. And here it is revealed that knowledge expressed in a judgment by means of concepts, what we call abstract knowledge always has its object outside itself and, reaching the content of the object itself, at the same time is not the true possession of the object , but gives only a secondary reproduction of it in the reflected, lower sphere of concepts. The object, unlike knowledge, the intuitive possession of which is a condition and an unattainable guiding ideal of abstract knowledge. The study of this ratio of crops the second part of our book. In the third part the study of the relationship between knowledge and being is supplemented by an understanding of the concept of being as a concrete-over-time all-unity, precisely as a unity of timelessness and becoming, or ideality and reality. From this it is revealed that the highest stage of intuition can be lshiazshgyaie-life, where the subject in general is no longer opposed to the object, but knows the object by virtue of being merged with it in its very being, or where being and knowledge are really one and the same . Thus, the resolution of the epistemological problem of the relationship between knowledge and being is possible only through the clarification of the meaning of the concept of being, i.e., through the discovery of that excess of unity, self-affirmation, completeness and concreteness that distinguishes being from knowledge about it; thus this resolution coincides with the clarification of the foundations and limits of abstract knowledge.

The object, unlike knowledge, the intuitive possession of which is a condition and an unattainable guiding ideal of abstract knowledge. The study of this ratio of crops the second part of our book. In the third part the study of the relationship between knowledge and being is supplemented by an understanding of the concept of being as a concrete-over-time all-unity, precisely as a unity of timelessness and becoming, or ideality and reality. From this it is revealed that the highest stage of intuition can be lshiazshgyaie-life, where the subject in general is no longer opposed to the object, but knows the object by virtue of being merged with it in its very being, or where being and knowledge are really one and the same . Thus, the resolution of the epistemological problem of the relationship between knowledge and being is possible only through the clarification of the meaning of the concept of being, i.e., through the discovery of that excess of unity, self-affirmation, completeness and concreteness that distinguishes being from knowledge about it; thus this resolution coincides with the clarification of the foundations and limits of abstract knowledge. The dispute between idealism and realism is the dispute between rationalism and intuitionism; the justification of realism is possible only through seeing the falsity of rationalism. All this relationship as a whole is expressed in the beautiful, energetic and intelligible words of Nicholas of Cusa, in which we can summarize our general worldview:

The dispute between idealism and realism is the dispute between rationalism and intuitionism; the justification of realism is possible only through seeing the falsity of rationalism. All this relationship as a whole is expressed in the beautiful, energetic and intelligible words of Nicholas of Cusa, in which we can summarize our general worldview:

"Negari nequit, quin prius natura res sit, quam sit cognosibilis. Igitur essendi modum neque sensus, neque imaginatio, neque intellectus attingit, cum haec omnia praecedat... Habemusigitur visum mentalem intuentem in id, quod est priusomni cognitione" (Compendium, cap. 1, Opera 1514, 169 a).

the prejudicial question is opposed: have we not transgressed the limits of a pure "theory of knowledge", have we not fallen into "dogmatism", solving questions of epistemology through ontological research? The only answer we can give to this question is that we consider the statement itself question is false. It is known that methodological requirements and concepts are always determined by one or another understanding of the essence of the subject. geological problem, there is no "epistemology" outside of "ontology". If knowledge by its very concept is knowledge of an object, then no investigation of knowledge is possible outside the investigation of the object of knowledge. Fortunately, we are not alone in this understanding: at the present time, in principle, it can no longer be considered a novelty, and, moreover, it was achieved in the movement that arose on the basis of Kantianism and set as its task precisely the development of pure epistemology. In the works of such thinkers as Schuppe, Cohen, Rehmke, Husserl, in various forms, the general conviction is expressed that there is no epistemology as a study of "cognition" outside the study of its subject, but there is only a single science that embraces the unity of knowledge and its subject - all the same whether we call it "phenomenology", "pure logic", "basic science" or "ontology". In essence, the whole movement of purifying epistemology from "psychologism" comes down precisely to the destruction of a special "theory of knowledge" as a science that is different from the "theory of being" and precedes it.

geological problem, there is no "epistemology" outside of "ontology". If knowledge by its very concept is knowledge of an object, then no investigation of knowledge is possible outside the investigation of the object of knowledge. Fortunately, we are not alone in this understanding: at the present time, in principle, it can no longer be considered a novelty, and, moreover, it was achieved in the movement that arose on the basis of Kantianism and set as its task precisely the development of pure epistemology. In the works of such thinkers as Schuppe, Cohen, Rehmke, Husserl, in various forms, the general conviction is expressed that there is no epistemology as a study of "cognition" outside the study of its subject, but there is only a single science that embraces the unity of knowledge and its subject - all the same whether we call it "phenomenology", "pure logic", "basic science" or "ontology". In essence, the whole movement of purifying epistemology from "psychologism" comes down precisely to the destruction of a special "theory of knowledge" as a science that is different from the "theory of being" and precedes it. However, in view of the ambiguity of the word "ontology", we prefer to call this unified "theory of knowledge and being" not an ontology, but the old and quite appropriate Aristotelian term "first philosophy". The first philosophy is really the first study, no longer based on anything else, of the fundamental principles of being, on the basis of which the distinction between knowledge and the object of knowledge is first possible; in relation to this science, both "epistemology" and "ontology" in the narrow sense are only subordinate and interconnected private spheres of knowledge. nine0003

However, in view of the ambiguity of the word "ontology", we prefer to call this unified "theory of knowledge and being" not an ontology, but the old and quite appropriate Aristotelian term "first philosophy". The first philosophy is really the first study, no longer based on anything else, of the fundamental principles of being, on the basis of which the distinction between knowledge and the object of knowledge is first possible; in relation to this science, both "epistemology" and "ontology" in the narrow sense are only subordinate and interconnected private spheres of knowledge. nine0003

This already indicates that our worldview has points of contact with modern German philosophy and thus with classical German idealism, of which the latter is only an imperfect revival; however, in its general spirit, it deviates far from them. We feel ourselves closer to the philosophy of Bergson, even closer to certain currents of Russian philosophy. Nevertheless, we cannot classify ourselves as belonging to any modern philosophical school and have the courage to think, for better or worse, but in our own way. This by no means, however, does not mean that we lay claim to the unconditional originality and novelty of our views. The mood of the bachelor from Faust, to whom Mephistopheles’ apt words about “originals” are directed, does not tempt us in the least; old truth. This “old truth” seems to us to be most deeply and most fully revealed in the systems of two thinkers, of which one is not only chronologically, but also systematically the finalizer of the most valuable traditions of ancient thought, and the other is not only the initiator and forerunner of all new philosophy, but at the same time and the best exponent in it of its eternal foundation in the face of the ancient heritage. We mean Plotinus and Nicholas of Cusa. We are far from any blind worship of these thinkers, which is impossible simply because they differ in many respects; and whoever is familiar with the process of philosophical creativity knows that genuine philosophical convictions cannot be "read" from any books at all. We personally turned to these forgotten thinkers only when the philosophical worldview already formed in us forced us to pay more attention to their previously only superficially known systems.

This by no means, however, does not mean that we lay claim to the unconditional originality and novelty of our views. The mood of the bachelor from Faust, to whom Mephistopheles’ apt words about “originals” are directed, does not tempt us in the least; old truth. This “old truth” seems to us to be most deeply and most fully revealed in the systems of two thinkers, of which one is not only chronologically, but also systematically the finalizer of the most valuable traditions of ancient thought, and the other is not only the initiator and forerunner of all new philosophy, but at the same time and the best exponent in it of its eternal foundation in the face of the ancient heritage. We mean Plotinus and Nicholas of Cusa. We are far from any blind worship of these thinkers, which is impossible simply because they differ in many respects; and whoever is familiar with the process of philosophical creativity knows that genuine philosophical convictions cannot be "read" from any books at all. We personally turned to these forgotten thinkers only when the philosophical worldview already formed in us forced us to pay more attention to their previously only superficially known systems. In addition, for us these two systems are only the brightest and richest expressions of a single great, truly universal current of philosophical thought. And if one must unfailingly belong to a certain philosophical "sect", then we recognize ourselves as belonging to the old, but not yet obsolete, secteplatonicists. From this point of view, for us, even the whole "transcendental philosophy" is only a stage in the history of Platonism. nine0003

In addition, for us these two systems are only the brightest and richest expressions of a single great, truly universal current of philosophical thought. And if one must unfailingly belong to a certain philosophical "sect", then we recognize ourselves as belonging to the old, but not yet obsolete, secteplatonicists. From this point of view, for us, even the whole "transcendental philosophy" is only a stage in the history of Platonism. nine0003

According to the original plan of our work, it was to be accompanied by a number of historical excursions, in which we wanted to reveal more precisely the historical roots and horizons of the worldview of absolute or concrete ideal-realism, which is outlined in our study. But, on the one hand, our book has already grown excessively, and on the other hand, it became clear to us that the historical studies we had planned were too broad and - due to the undeveloped material - too responsible to be combined with a systematic study. We have therefore limited ourselves to one appendix on the "history of the ontological proof", in which, on a particular but central issue, we have attempted to present this kind of historical perspective; otherwise, we could only casually note in epigraphs and notes our connection with the philosophical past, and, moreover, almost exclusively with the two named representatives of Platonism. nine0003

nine0003

The author considers it his duty to express his deep gratitude to the Faculty of History and Philology of Petrograd University, which provided funds for the publication of his work and on whose proposal the author was sent abroad, and, in particular, to prof. AI Vvedensky, who initiated this idea.

Borovichi, Novgorod. lips.

Summer 1915

S. Frank

Source: Subject of knowledge about the foundations and limits of abstract knowledge; Soul of man: Experience introduced. in philosophy. psychology / S. L. Frank; [Intro. Art. I. I. Evlampiev, p. 5-34]. - St. Petersburg. : Nauka : St. Petersburg. ed. firm, 1995. - 655 p. / Subject of knowledge. 37-416 p. ISBN 5-02-28231-6

TASK: print the given passage, find definitions, determine what they are

6 Find two sentences on the shell (house) of the snail. Write them down. Make up interrogative and incentive sentences to continue this current … Art.

§ 31. WHY? I Read the text. We were alone in the dining room - me and Boom. I dangled under the table with my feet, and Boom lightly tapped me by my bare heels. I was ticklish … and funny. Above the table hung a large camera, my mother and I only recently gave it to be enlarged. On this card, dad has a cheerful, kind face. But when, playing around with Boom, I began to sway in a chair, - P shakes his head. 1 - Look, Boom, - I said in a whisper and, strongly swaying in a chair, grabbed the edge of the tablecloth. There was a ringing... My heart sank. I quietly SLIDED FROM the chair and lowered my eyes. Pink shards lay on the floor. Boom crawled out from under the table, carefully sniffed at the skulls, and sat down with his head tilted to one side and one ear raised up. Oar Quick footsteps were heard from the kitchen. - - What is it? Who is this? Mom knelt down and covered her face with her hands. Papa's papa's cup... - she repeated bitterly. Then she raised her eyes and asked reproachfully: My knees were shaking, my tongue was slurring.

WHY? I Read the text. We were alone in the dining room - me and Boom. I dangled under the table with my feet, and Boom lightly tapped me by my bare heels. I was ticklish … and funny. Above the table hung a large camera, my mother and I only recently gave it to be enlarged. On this card, dad has a cheerful, kind face. But when, playing around with Boom, I began to sway in a chair, - P shakes his head. 1 - Look, Boom, - I said in a whisper and, strongly swaying in a chair, grabbed the edge of the tablecloth. There was a ringing... My heart sank. I quietly SLIDED FROM the chair and lowered my eyes. Pink shards lay on the floor. Boom crawled out from under the table, carefully sniffed at the skulls, and sat down with his head tilted to one side and one ear raised up. Oar Quick footsteps were heard from the kitchen. - - What is it? Who is this? Mom knelt down and covered her face with her hands. Papa's papa's cup... - she repeated bitterly. Then she raised her eyes and asked reproachfully: My knees were shaking, my tongue was slurring. - It's... it's... Boom! - Boom? - Mom got up from her knees and slowly asked again: - Is this Boom? I nodded my head. Boom, hearing his name, moved his ears and wagged his tail. Mom rela first at me, then at him. How did he break? My ears were on fire. I spread my arms: -He jumped a little... and with his paws... Mom's face darkened. She took Boom by the collar and walked with him to the door. I stared after her. Boom jumped out into the yard barking. “He will live in a booth,” my mother said, and, sitting down at the table, thought about something. Her pas were slowly raked into a pile of crumbs of bread, rolled them into balls, and her eyes looked at one point over the table. I stood there, not daring to approach her. Boom scratched at the door. - Don't let it! - Mom said quickly and, taking my hand, pulled me to her. Pressing her bami against my forehead, she still thought about something, then quietly asked: - You were very frightened. Of course, I was very frightened: after all, since my father died, my mother and I took care of every thing.

- It's... it's... Boom! - Boom? - Mom got up from her knees and slowly asked again: - Is this Boom? I nodded my head. Boom, hearing his name, moved his ears and wagged his tail. Mom rela first at me, then at him. How did he break? My ears were on fire. I spread my arms: -He jumped a little... and with his paws... Mom's face darkened. She took Boom by the collar and walked with him to the door. I stared after her. Boom jumped out into the yard barking. “He will live in a booth,” my mother said, and, sitting down at the table, thought about something. Her pas were slowly raked into a pile of crumbs of bread, rolled them into balls, and her eyes looked at one point over the table. I stood there, not daring to approach her. Boom scratched at the door. - Don't let it! - Mom said quickly and, taking my hand, pulled me to her. Pressing her bami against my forehead, she still thought about something, then quietly asked: - You were very frightened. Of course, I was very frightened: after all, since my father died, my mother and I took care of every thing.