Reading comprehension and fluency

Reading Fluency vs Reading Comprehension

by Melissa Mullin, Ph.D. | posted in: Dyslexia, Learning, Reading | 0

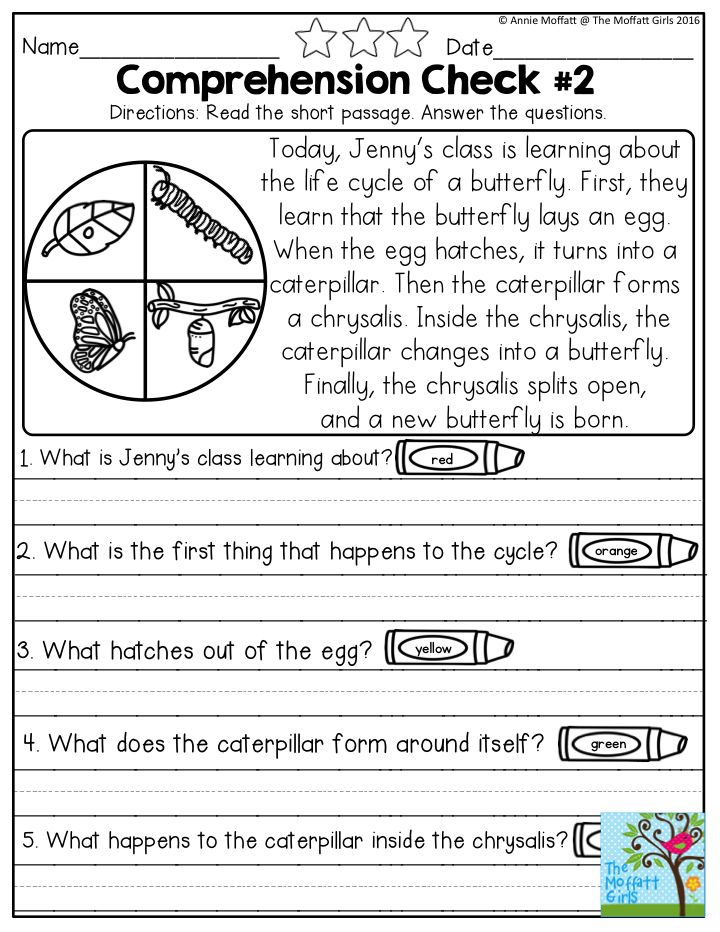

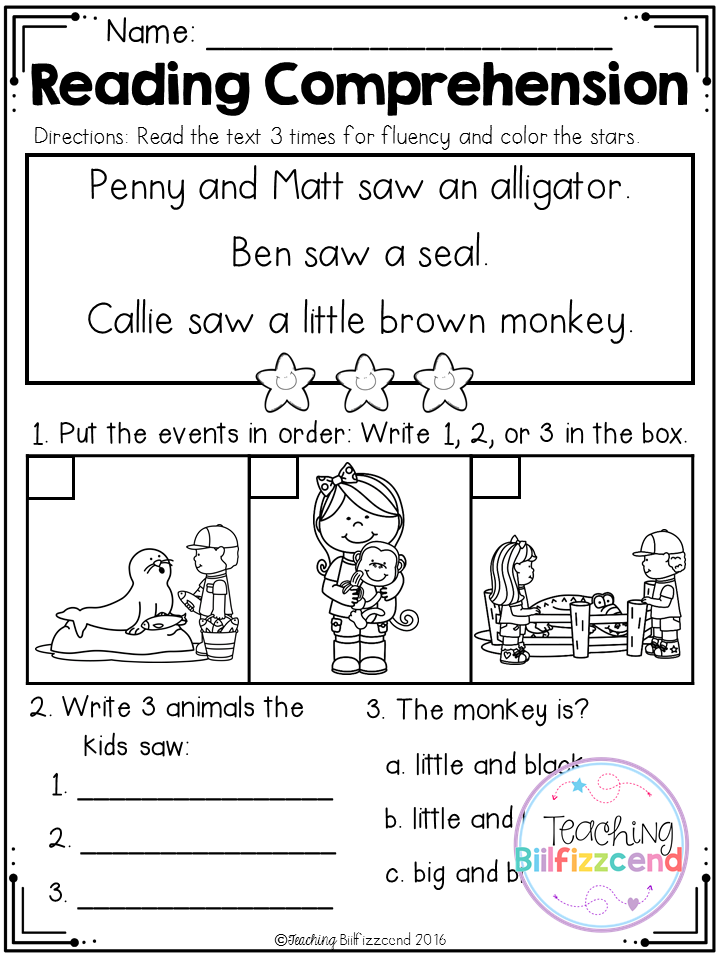

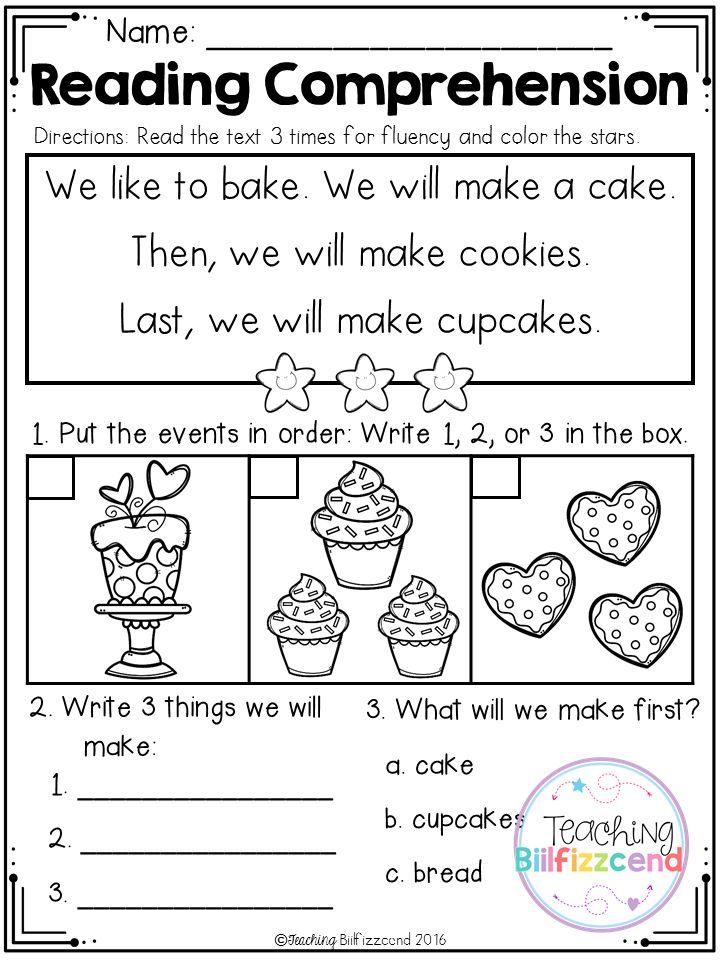

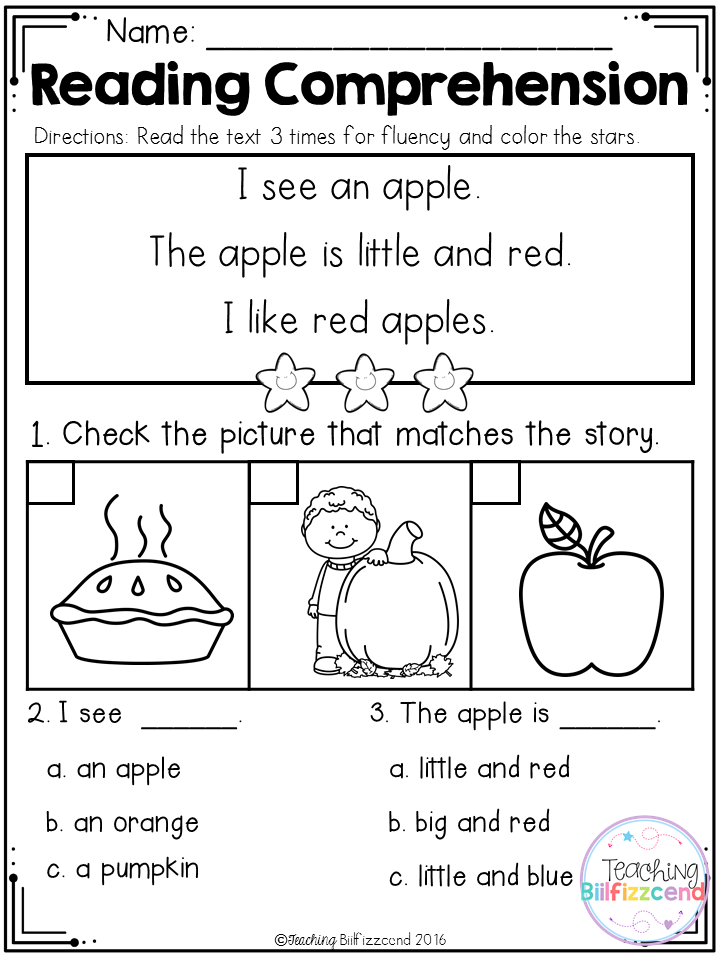

The goal of reading is to gain information, whether it is what happens to the characters in a story, or learning about the world. Reading fluency is the speed and accuracy of decoding words. Reading comprehension is the ability to understand what you are reading. A student is considered a proficient reader when reading fluency and reading comprehension are at grade level.

Achieving the proper balance between reading fluency and reading comprehension is important. Some students who struggle with learning to read will focus more on the mechanics of reading (decoding) and miss comprehending what they are reading. Other students can easily understand what they are reading even though they struggle with decoding.

It is important to develop both reading fluency and reading comprehension in all students. Fluid reading skills make reading easier and more enjoyable. Reading comprehension lets the student acquire knowledge and follow a story line. When there is a significant difference between fluency and comprehension skills it is wise to address them separately.

When reading comprehension skills are higher than reading fluency skills:

- Practicing reading fluency at the child’s reading decoding level will help build reading fluency skills.

- When reading fluency is low, consider these interventions:

- Does the child need repeated practice readings to develop a better reading rate?

- Does the child need phonemic rules to increase reading accuracy

- Does the child need rapid automatic naming skills to build the phonological loop?

- Listening to audiobooks, or being read to, at comprehension level, will enable a student who struggles with reading fluency to gain knowledge, build vocabulary, hone thinking skills, and develop the joy of the written word.

- Consider getting extra time for tests and exams so students can demonstrate their knowledge.

- When reading fluency is low, consider these interventions:

Check out my blog post on reading apps that use text-to-speech software to allow students to read along as the story is read to them. Bookshare offers free access to students with dyslexia or visual issues. These programs allow students to enhance their vocabulary and enjoyment of books. The best part of these apps is that they highlight the words as they read, encouraging students to read along.

When reading fluency skills are higher than reading comprehension skills:- Make sure the student slows down and processes what the words are saying.

- Before beginning a book take time to discuss the cover and title with the student:

- Why do you think they chose this title?

- What do you think the book is going to be about?

- Before beginning a book take time to discuss the cover and title with the student:

- Stop and ask comprehension questions as you read:

- What do you think the main character looks like?

- What do you think the setting looks like?

- What do you think will happen next?

- Why do you think that character did that?

- Is what just happened in the book something you have ever experienced?

Fluid reading with good comprehension is the goal for all readers. Some students learn one aspect of reading more easily than the other. Take the time to build both fluency and comprehension so your child becomes a proficient reader.

Some students learn one aspect of reading more easily than the other. Take the time to build both fluency and comprehension so your child becomes a proficient reader.

Like this:

Like Loading...

Fluency: Introduction | Reading Rockets

Fluency is the ability to read a text with accuracy, automaticity, and prosody (expression) sufficient to enable comprehension. Fluency is a key skill to becoming a strong reader because it provides a bridge between word recognition and comprehension.

Letter of completion

After completing this module and successfully answering the post-test questions, you'll be able to download a Letter of Completion.

Why fluency is important

When fluent readers read silently, they recognize words automatically. They group words quickly to help them gain meaning from what they read. Fluent readers read aloud effortlessly and with expression — their reading sounds natural, as if they are speaking, an aspect of fluency that is termed prosody. Readers who have not yet developed fluency read slowly, word by word. Their oral reading is choppy and lacks prosody.

Readers who have not yet developed fluency read slowly, word by word. Their oral reading is choppy and lacks prosody.

Fluency is important for several reasons. First, fluent reading is a foundation for good reading comprehension. Because fluent readers do not have to concentrate on decoding words, they can focus their attention on what the text means. They can make connections between the ideas in the text and their background knowledge.

In other words, fluent readers recognize words and comprehend at the same time. Reading fluency also affects a child's motivation to read. Children (and adults!) typically do not enjoy activities that feel burdensome and difficult. When children’s reading is not fluent, they often don’t enjoy reading, and they are less inclined to practice reading, which may contribute even further to a decline in their reading skills.

In addition, learning to read fluently helps children become better prepared for the demands of the upper grades.

In the middle school and high school, students are usually expected to do a lot of independent reading. Even if students can read accurately, if they are not fluent, they may take much longer to complete their schoolwork.

Even if students can read accurately, if they are not fluent, they may take much longer to complete their schoolwork.

Fluent reading is a product of strong decoding and strong language comprehension. Less fluent readers, however, must focus their attention on figuring out the words, leaving them little attention for understanding the text.

Fluency is important because it frees students to understand what they read!

Adapted from: Put Reading First: The Research Building Blocks for Teaching Children to Read Kindergarten Through Grade 3, a publication of The Partnership for Reading.

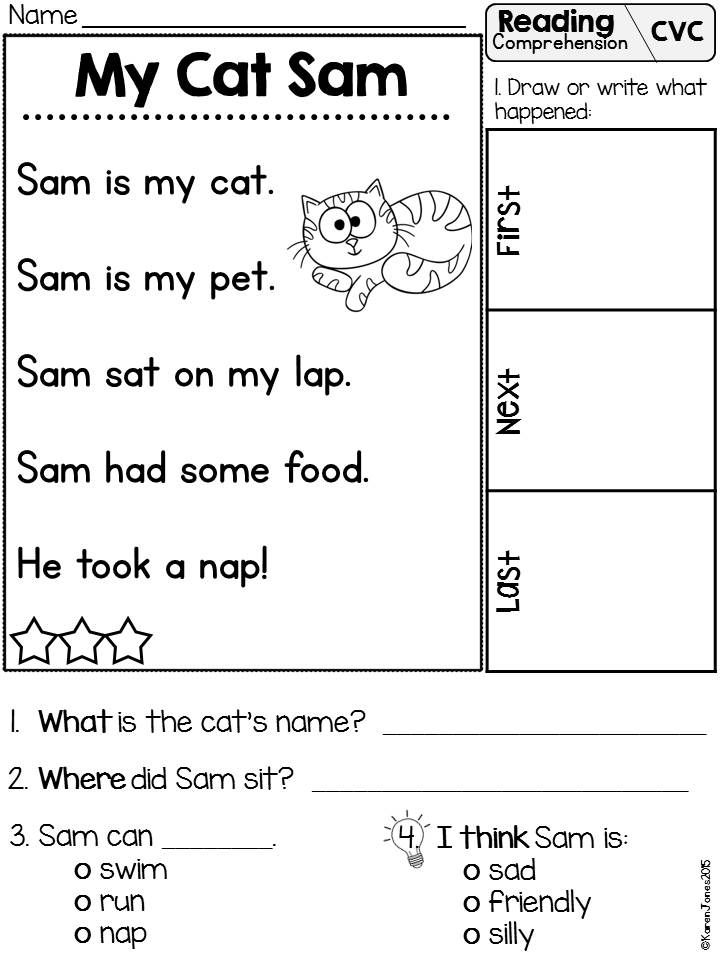

Reading fluently: what it looks like in kindergarten to third grade

In this milestones series from Great Schools, listen to how fluent readers sound in kindergarten through third grade.

Next: Fluency Pre-Test >

6 Key Skills for Reading Comprehension

For some people, reading is like a walk in the park on a warm summer day, an enjoyable activity that is easy to master. In fact, reading is a complex process that involves many different skills. Together, these skills lead to the ultimate goal of learning to read: comprehensive reading comprehension.

In fact, reading is a complex process that involves many different skills. Together, these skills lead to the ultimate goal of learning to read: comprehensive reading comprehension.

Text comprehension can be difficult for children for many reasons, but regardless of them, knowing what underdeveloped skills this is due to, you will be able to provide your child with the best help.

Let's take a look at the six reading comprehension skills and how you can help your child develop them.

1. Decoding

Decoding is an extremely important step in the reading process. Children use this skill to sound out words they have heard before but not seen written. The ability to decode is the foundation of all other reading skills.

Decoding relies on one of the first language skills to develop, phonemic comprehension (this skill is part of a broader set of skills called phonological comprehension). Phonemic awareness allows children to hear and distinguish individual sounds in words (also known as phonemes). It also allows them to "play" with sounds in syllables and words.

Phonemic awareness allows children to hear and distinguish individual sounds in words (also known as phonemes). It also allows them to "play" with sounds in syllables and words.

Decoding also relies on the ability to match individual sounds and letters. For example, to read the word "sun", the child must know that the letter "s" sounds like "s". Understanding the relationship between letters and sounds is an important step towards "voicing" words.

How to help: Many children learn phonological awareness naturally by reading books, listening to songs and poems. But for some children it is not so easy. In fact, one of the earliest signs of reading difficulty is trouble with rhyming, counting syllables, or identifying the first sound in a word.

The best way to help your child improve these skills is to guide them with precise instructions and lots of practice. Children need to be taught how to correctly identify sounds and work with them. You can also develop phonological perception by playing with words, reading poems aloud to your child, or using special computer techniques aimed at developing phonemic perception and decoding.

You can also develop phonological perception by playing with words, reading poems aloud to your child, or using special computer techniques aimed at developing phonemic perception and decoding.

2. Reading fluently

To read fluently, children must recognize words immediately, including words that do not read as they are written. By developing reading fluency, the child increases not only reading speed, but also reading comprehension.

Decoding and reading each word can be a lot of work. Word recognition is the ability to recognize a word instantly just by looking at it, without having to read it out loud. When children can read quickly and with almost no errors, they are said to be able to read "fluently".

People who can read fluently read fluently and rhythmically. They use the context to understand the meaning and change the intonation in their voice depending on what they are reading about. The ability to read fluently is critical to a good understanding of the text.

How to help: Word recognition can be a big hurdle for beginning readers. Usually a person needs to see a word from 4 to 14 times in order to learn to automatically recognize it. But, for example, children diagnosed with dyslexia may need to see the word up to 40 times.

Many children have difficulty reading fluently. To improve word recognition and other reading skills, children need help and a lot of practice. The best way to strengthen these skills is to practice reading books. It is important to choose books that are appropriate for the child's reading level.

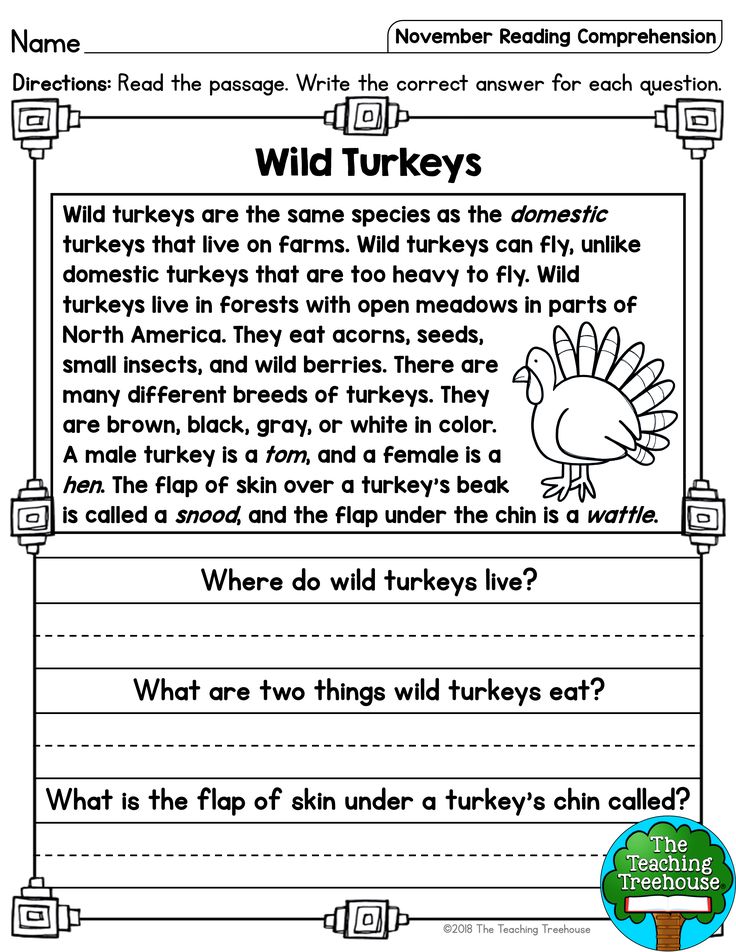

3. Vocabulary

To understand what you read, you need to understand at least most of the words in the text. A rich vocabulary is a key component of text comprehension. Students can learn new words during class, but they usually learn the meaning of words through everyday situations and while reading.

How to help: The more new words children learn, the more their vocabulary grows. You can help your child develop vocabulary by talking to him often about different topics, introducing him to new words and concepts. Word games and funny jokes are also fun ways for children to reinforce these skills.

You can help your child develop vocabulary by talking to him often about different topics, introducing him to new words and concepts. Word games and funny jokes are also fun ways for children to reinforce these skills.

Daily reading together also helps to build vocabulary. When reading aloud to your child, stop when you encounter new words and explain their meaning. But it is also important that the child reads independently. Even if there is no one to explain the meaning of a new word, the child can guess its meaning from the context, and also learn with the help of a dictionary.

Teachers can also help by choosing interesting words to study and learning them all together in class. To practice vocabulary, the teacher can engage students in dialogue during the lesson, or play word games to make learning new words fun.

4. Sentence construction and cohesion

Understanding how sentences are built can seem like a skill necessary for writing. The same can be said about the connection of ideas within and between sentences, which is called cohesion. But these skills are also important for reading comprehension.

The same can be said about the connection of ideas within and between sentences, which is called cohesion. But these skills are also important for reading comprehension.

Knowing how ideas connect at the sentence level helps children make sense of passages and entire texts. This also leads to what is called coherence, or the ability to relate ideas to other ideas in a common work.

How to help: Explain the basics of sentence construction to your child. Work with him to connect two or more thoughts, both in writing and orally.

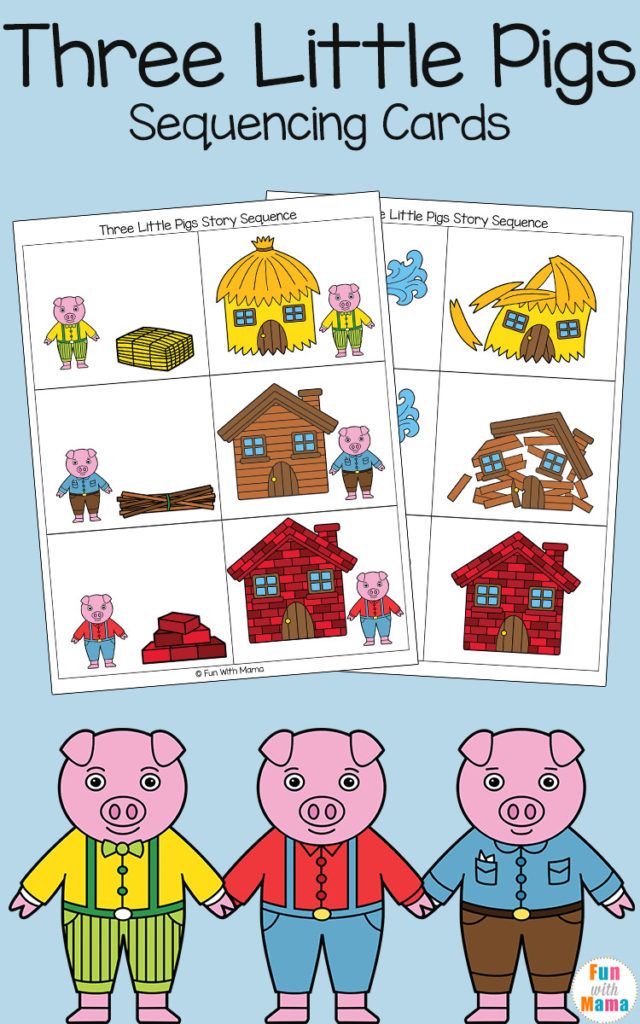

5. Expanding horizons and reasoning

read. It is also important to teach the child to “read between the lines” and find meaning where it is not literally written.

How to help: Your child can broaden their horizons through reading, socializing, watching movies and TV shows, and exploring art. Also many things come with years of personal experience.

Open up opportunities for your child to gain new useful knowledge in different areas and discuss with him what you have learned from the experience gained, both together and separately. Help your child make connections between new and old knowledge and ask questions that require extended answers and thoughtful explanations.

Help your child make connections between new and old knowledge and ask questions that require extended answers and thoughtful explanations.

You can also read these tips on how to use cartoons to help your child learn to judge for themselves.

6. Working memory and attention

These two skills are part of a group of skills also known as executive functions. They are different, but closely related.

When children read, attention allows them to absorb information from the text. Working memory helps them retain this information and use it to make sense and gain knowledge from what they read.

The ability to control oneself while reading is also related to executive functions. The child must be able to recognize when he does not understand something, stop, go back and reread, so that there is no doubt about the understanding of what he read.

How to help: There are many ways to help your child improve working memory, and it doesn't have to look like a lesson. There are many games and daily activities that can help develop working memory in a way that your child won't even notice!

There are many games and daily activities that can help develop working memory in a way that your child won't even notice!

To improve your child's concentration, look for reading materials that interest and/or motivate your child. For example, some children love graphic novels. Teach your child to stop and reread the text when something is not clear to him. And show him how you “think out loud” when you read to make sure it makes sense.

More ways to help with text comprehension

When children have difficulty learning the above skills, they may find it difficult to fully understand what they read.

Find out what might be causing your child's reading difficulties. Remember, if a child has difficulty reading, it does not mean that he is not smart. But some children need extra support to successfully develop reading skills. The sooner you contact a specialist or start applying a special corrective technique, the less stress and lag in learning and development your child will receive. Pay attention to the computer technique Fast ForWord, aimed at developing the skills of phonemic perception, decoding, memory, concentration and other executive functions.

Pay attention to the computer technique Fast ForWord, aimed at developing the skills of phonemic perception, decoding, memory, concentration and other executive functions.

Pins

-

Decoding, reading fluency and vocabulary are key skills needed for reading comprehension.

-

Understanding how ideas connect within and between sentences helps children understand the entire text.

-

Reading aloud and discussing experiences can help a child develop reading skills.

Quickly and permanently develop reading skills: decoding, reading comprehension, extracting meaning from context, reading fluency, etc., as well as concentration, memory, information processing - classes using the Fast ForWord online method will help you.

Sign up for trial online classes in Fast ForWord right now!

Don't delay helping your child!

Source

A study of the co-development of reading fluency and reading comprehension through mindful learning of phrases [In English]

Science for Education Today, 2020, vol. 10, no. 3, pp. 7–27

10, no. 3, pp. 7–27

© Honamri F., Pavlikova M., Falahati F., Petrikovikova L., 2020

UDC:

378+159+314

A study of the co-development of reading fluency and reading comprehension through conscious learning of word combinations [In English]

Honamri F. 1 (Babolser, Iran), Pavlikova M. 2 (Nitra, Slovakia), Falahati F. 1 (Babolser, Iran), Petrikovikova L. 2 (Nitra, Slovakia)

1 University of Mazandaran

2 University of Constantine the Philosopher in Nitra

Annotation:

Problem and goal. Mindfulness propensity and its impact on student performance has been extensively researched over the past two decades. Mindfulness is defined as focused attention to present moment experiences, devoid of judgment, resulting in a sense of stability and non-reactive awareness (Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, 2004). In addition, it has been proven that the phrase plays an important role in the development of reading fluency and understanding in students. Thus, the present study attempted to investigate whether mindful learning of phrases has a positive effect on students' reading fluency and reading comprehension.

Thus, the present study attempted to investigate whether mindful learning of phrases has a positive effect on students' reading fluency and reading comprehension.

Methodology. To this end, 30 students of English language and literature, studying at the Department of English at the University of Mazandaran, took part in this study. A reading comprehension test taken from TOEFL was used to measure students' reading ability in order to homogenize them in terms of their initial behavior. In addition, the Word Associate test advanced by Read (1993, 1998) was used to examine participants' vocabulary depth and collocation knowledge. In addition, the Conscious Attention Scale (MAAS) developed by Brown & Ryan (2003) was used to identify attentive and less attentive students. All participants were then divided into two groups of attentive and less attentive participants for a deeper analysis.

Results. The Wilcoxon and Maan-Whiteney U-test results showed that both explicit and implicit groups progressed between pretest and posttest, and there were no significant differences between the effects of explicit and implicit collocation training.

In addition, the results of mindful learning of phrases were not effective. The results showed that none of the instruction types had an effect on students' reading fluency. Further analysis of the effect of mindfulness on students' reading fluency showed that there was little difference between less attentive and attentive students.

Conclusion. The authors concluded that educators should be alert to which method might be more influential in improving students' reading fluency.

Keywords:

improvement in reading fluency; development of reading comprehension; conscious learning of phrases; reading comprehension ability.

WoS/RSCI URL: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/rsci/full-record/RSCI:43091307

SciVal Relevance Percentile : 95.235 Vocabulary Learning | Extensive Reading | EFL Learner

https://www.scopus.com/record/display.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85088372110&origin=...

Reference:

Honamri F. , Pavlikova M., Falahati F. ., Petrikovikova L. A study of the co-development of reading fluency and reading comprehension through conscious learning of phrases [In English] // Science for Education Today. - 2020. - No. 3. - P. 7–27. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15293/2658-6762.2003.01

, Pavlikova M., Falahati F. ., Petrikovikova L. A study of the co-development of reading fluency and reading comprehension through conscious learning of phrases [In English] // Science for Education Today. - 2020. - No. 3. - P. 7–27. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15293/2658-6762.2003.01

References:

- Aghbar A. Fixed expressions in written texts: implications for assessing writing sophistication. Paper presented at a meeting of the English Association of Pennsylvania State System Universities, 1990. URL: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED329125

- Bahns J. Lexical collocations – a contrastive view. ELT Journal. ‒ 1993. ‒ Vol. 47(1). – Pp. 56–63. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/47.1.56

- Cain K., Oakhill J., Bryant P. Children’s reading comprehension ability: concurrent prediction by working memory, verbal ability, and component skills // Journal of Educational Psychology. ‒ 2004. ‒ Vol. 96(1). – Pp. 31. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.1.31

- DeKeyser R.

M. Implicit and Explicit Learning // C. J. Doughty, M. H. Long (Eds.) The Handbook of Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. 2005. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470756492.ch21

M. Implicit and Explicit Learning // C. J. Doughty, M. H. Long (Eds.) The Handbook of Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. 2005. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470756492.ch21 - Fuchs L., Fuchs D., Hosp M., Jenkins J. Oral reading fluency as an indicator of reading competence: A theoretical, empirical, and historical analysis // Scientific Studies of Reading. ‒ 2001. ‒ Vol. 5. -Pp. 239-256. ISSN-1088-8438

- Gadušová Z., Hašková A., Jakubovská V. Stratified Approach to Teachers' Competence Assessment // INTED 2018: Proceedings from 12th International Technology, Education and Development Conference. Valencia: IATED Academy. 2018. ‒ Pp. 2757–2766. ISBN 978-84-697-9480-7, ISSN 2340-1079

- Gadušová Z., Hasková A., Predanocyová Ľ. Teachers’ professional competence and their evaluation // Education and Self Development. ‒ 2019. ‒ Vol. 14(3). – Pp. 17–24. ISSN 1991-7740. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.26907/esd14.3.02

- Gitsaki C. Second language lexical acquisition: A study of the development of collocational knowledge.

Maryland: International Scholars Publications. 1999. ISBN: 9781573093897

Maryland: International Scholars Publications. 1999. ISBN: 9781573093897 - Grossman P., Niemann L., Schmidt S., Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits. A meta-analysis // Journal of Psychosomatic Research. ‒ 2004. ‒ Vol. 57(1). – Pp. 35–43. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7

- Howarth P. Phraseology and second language proficiency // Applied Linguistics. - 1998. - Vol. 19(1). – Pp. 24–44. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/19.1.24

- Hsu J-Y. The effects of direct collocation instruction on the English proficiency of Taiwanese college students in a business English workshop // Soochow Journal of Foreign Languages and Cultures. ‒ 2005. ‒ Vol. 21. ‒ Pp. 1–39. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.16986/HUJE.2018038632

- Irwansyah D., Nurgiyantoro B., Sugirin Literature-Based reading material for EFL students: a case of Indonesian Islamic University // XLinguae. ‒ 2019. ‒ Vol. 13(3). ‒ ISSN 1337-8384, eISSN 2453-711X.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18355/XL.2019.11.03.03

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18355/XL.2019.11.03.03 - Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, N.Y.: Dell Publishing. 1990. Ebook/DAISY202 ISBN: 978-0-345-53693-8/ URL: https://www.scirp.org/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=1683041

- Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) // Constructivism in the Human Sciences. ‒ 2003. ‒ Vol. 8. - Pp. 73–107. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2018.63049

- Kintsch W. Comprehension: a paradigm for cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1998. ISBN-13: 978-0521629867

- Králik R., Lenovský L., Pavlikova M. A few comments on identity and culture of one ethnic minority in central Europe // European Journal of Science and Theology. ‒ 2018. ‒ Vol. 14(6). – Pp. 63–76. ISSN: 1841-0464. URL: http://www.ejst.tuiasi.ro/Files/73/7_Kralik%20et%20al.pdf

- LaBerge D., Samuels S. J. Toward a theory of automatic information processing reading // Cognitive Psychology.

- 1974. - Vol. 6. -Pp. 293–323. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(74)-2

- 1974. - Vol. 6. -Pp. 293–323. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(74)-2 - Langer E. J. The power of mindful learning. Cambridge, MA: Persesus Publishing. 1997. ISBN-10: 0738219088, ISBN-13: 978-0738219080

- Langer E. J., Moldoveanu M. The construct of mindfulness // Journal of Social Issues. ‒ 2000. ‒ Vol. 56. - Pp. 1–9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537

- Lewis M. The lexical approach: The state of ELT and the way forward. Hove, England: Language Teaching Publication. 1993. ISBN-13: 978-0906717998 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.090671799X

- Lewis M. Implementing the lexical approach: Putting theory into practice. Hove, England: Language Teaching Publications. 1997. ISBN 1-899396-60-8

- Lewis M. Teaching collocation: Further developments in the lexical approach. Language Teaching Publications. 2000. ISBN 1-899396-11-X

- Liu C. P. A study of Chinese Culture University freshmen's collocational competence: ʻKnowledgeʼ as an example // Hwa Kang Journal of English Language Literature.

- 1999. - Vol. 5. -Pp. 81–99. URL: http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume18/ej72/ej72a4/

- 1999. - Vol. 5. -Pp. 81–99. URL: http://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume18/ej72/ej72a4/ - Linden W. Practicing of meditation by school children and their levels of field dependence-independence, test anxiety, and reading achievement // Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. ‒ 1973. ‒ Vol. 41. ‒ Pp. 139–143. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0035638

- Mahrik T., Kralik R., Tavilla I. Ethics in the light of subjectivity - Kierkegaard and Levinas // Astra Salvensis. ‒ 2018. ‒ Vol. 6. -Pp. 488–500. ISSN 2393-4727. URL: https://kpfu.ru/staff_files/F610085577/astra_salvensis_year_vi_2018_supplemnt_no_2.pdf

- Muryasov R. Z. On the periphery of the parts of speech system // XLinguae. ‒ 2019. ‒ Vol. 12(4). ISSN 1337-8384, eISSN 2453-711X. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18355/XL.2019.12.04.05

- Nattinger J., DeCarrico J. Lexical phrases and language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1992. ISBN-13: 978-0194371643, ISBN-10: 0194371646

- Nation I.

S.P. Learning Vocabulary in another language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 2001. ISBN:9781139524759

S.P. Learning Vocabulary in another language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 2001. ISBN:9781139524759 - Nesselhauf N. The use of collocations by advanced learners of English and some implications for teaching // Applied Linguistics. ‒ 2003. ‒ Vol. 24(2). – Pp. 223–242. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/iral-2016-0015

- Nation P., Waring R. Vocabulary size, text coverage, and word lists // N. Schmitt, & M. McCarthy (Eds). Vocabulary: Description, acquisition, pedagogy. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997. ‒ Pp. 6–19. ISBN:0521584841

- Nassaji H. The relationship between depth of vocabulary knowledge and L2 learners’ lexical inferencing strategy use and success // The Canadian Modern Language Review. ‒ 2004. ‒ Vol. 61(1). – Pp. 107–134. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/cml.2004.0006

- Novikova Y. B, Alipichev A. U., Kalugina O. A., Esmurzaeva Z. B., Grigoryeva S. G. Enhancement of socio-cultural and intercultural skills of EFL students by means of culture-related extra-curricular events // XLinguae.

‒ 2018. ‒ Vol. 11(2). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18355/XL.2018.11.02.16

‒ 2018. ‒ Vol. 11(2). DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18355/XL.2018.11.02.16 - Paribakht T. S., Wesche M. Vocabulary enhancement activities and reading for meaning in second language vocabulary acquisition // J. Coady, T. Huckin (Eds.) Second language vocabulary acquisition: A rationale for pedagogy Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. ‒ Pp. 174–200. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.461

- Stranovská E., Hvozdíková S., Munková D., Gadušová Z. Foreign Language Education and Dynamics of Foreign Language Competence // The European Journal of Social and Behavioral Sciences. ‒ 2016. ‒ Vol. 17(3). – Pp. 2141–2153. ISSN 2301-2218 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15405/ejsbs.192

- Stranovská E., Gadušová Z., Ficzere Factors Influencing Development of Reading Literacy in Mother Tongue and Foreign Language // ICERI 2019: 12th International conference of education, research and innovation Valencia. IATED, 2019. ‒ Pp. 6901–6907. ISBN 978-84-09-14755-7

- Tavilla I.

, Kralik R., Webb C., Jiang X., Manuel A. J. The rise of fascism and the reformation of Hegel’s dialectic into Italian neo-idealist philosophy // XLinguae. ‒ 2019. ‒ Vol. 12(1). – Pp. 139–150. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18355/XL.2019.12.01.11

, Kralik R., Webb C., Jiang X., Manuel A. J. The rise of fascism and the reformation of Hegel’s dialectic into Italian neo-idealist philosophy // XLinguae. ‒ 2019. ‒ Vol. 12(1). – Pp. 139–150. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18355/XL.2019.12.01.11 - Qian D. D. Assessing the role of depth and breadth of vocabulary knowledge in reading comprehension // The Canadian Modern Language Review. - 1999. - Vol. 56(2). – Pp. 282–307. ISSN-0008-4506. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.56.2.282

- Qian D. D. Investigating the relationship between vocabulary knowledge and academic reading performance: An assessment perspective // Language Learning. - 2002. - Vol. 52. - Pp. 513–536. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9922.00193

- Qian D. D., Schedl M. Evaluation of an in-depth vocabulary knowledge measure for assessing reading performance // Language Testing. ‒ 2004. ‒ Vol. 21(1). – Pp. 28–52. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/0265532204t273

- Read J. The development of a new measure of L2 vocabulary knowledge // Language Testing.

Learn more