Story about pigs

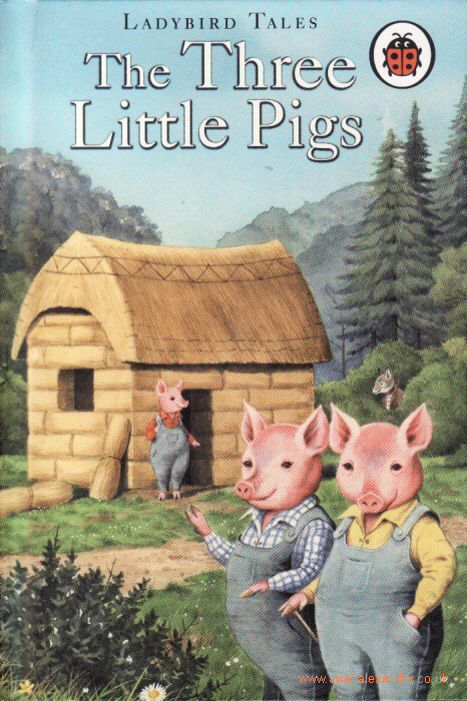

English | The Three Little Pigs

The Three Little Pigs

Mrs Pig was very tired: 'Oh dear,' she said to her three little pigs, 'I can’t do this work anymore, I’m afraid you must leave home and make your own way in the world.' So the three little pigs set off.

The first little pig met a man carrying a bundle of straw.

'Excuse me,' said the first little pig politely. 'Would you please sell some of your straw so I can make a house?'

The man readily agreed and the first little pig went off to find a good place to build his house.

The other little pigs carried on along the road and, soon, they met a man carrying a bundle of sticks.

'Excuse me,' said the little pig politely. 'Would you please sell me some sticks so I can build a house?'

The man readily agreed and the little pig said goodbye to his brother.

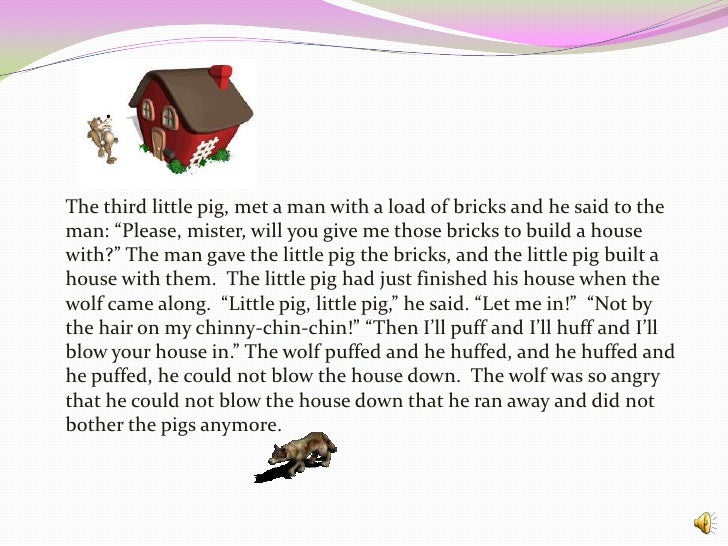

The third little pig didn’t think much of their ideas:

'I’m going to build myself a much bigger, better, stronger house,' he thought, and he carried off down the road until he met a man with a cart load of bricks.

'Excuse me,' said the third little pig, as politely as his mother had taught him. 'Please can you sell me some bricks so I can build a house?'

'Of course,' said the man. 'Where would you like me to unload them?'

The third little pig looked around and saw a nice patch of ground under a tree.

'Over there,' he pointed.

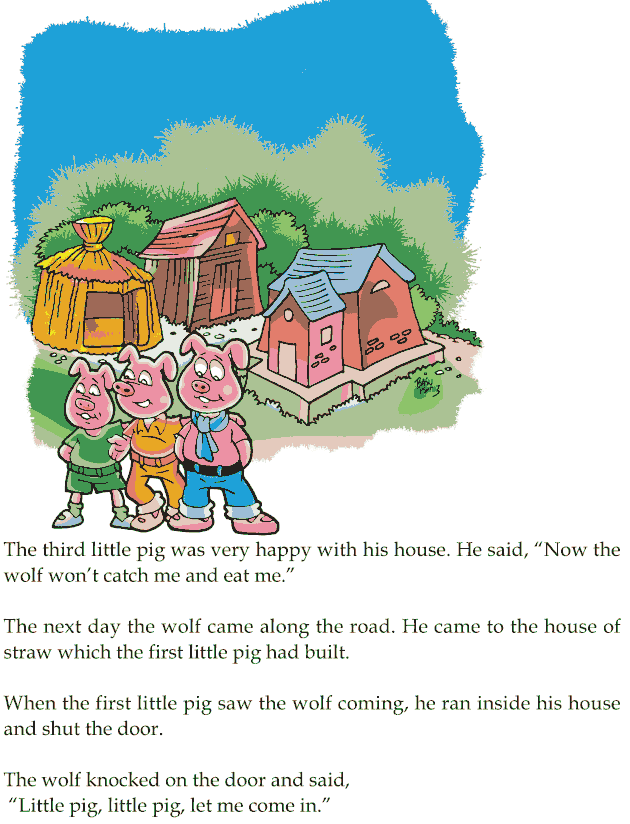

They all set to work and by nighttime the house of straw and the house of sticks were built but the house of bricks was only just beginning to rise above the ground. The first and second little pigs laughed, they thought their brother was really silly having to work so hard when they had finished.

However, a few days later the brick house was completed and looked very smartwith shiny windows, a neat little chimney and a shiny knocker on the door.

One starlit night, soon after they had settled in, a wolf came out looking for food. By the light of the moon he espied the first little pig’s house of straw and he sidled up to the door and called:

By the light of the moon he espied the first little pig’s house of straw and he sidled up to the door and called:

'Little pig, little pig, let me come in.'

'No, no, by the hair of my chinny chin chin!' replied the little pig.

'Then I’ll huff and I’ll puff and I’ll blow your house in!' said the wolf who was a very big, bad, and a greedy sort of wolf.

And he huffed, and he puffed and blew the house in. But the little pig ran away as fast as his trotters could carry him and went to the second little pig’s house to hide.

The next night the wolf was even hungrier and he saw the house of sticks. He crept up to the door and called:

'Little pig, little pig, let me come in.'

'Oh no, not by the hair on my chinny chin chin!' said the second little pig, as the first little pig hid trembling under the stairs.

'Then I’ll huff and I’ll puff and I’ll blow your house in!' said the wolf.

And he huffed, and he puffed and he blew the house in. But the little pigs ran away as fast as their trotters could carry them and went to the third little pig’s house to hide.

'What did I tell you?' said the third little pig. 'It’s important to build houses properly.' But he welcomed them in and they all settled down for the rest of the night.

The following night the wolf was even hungrier and feeling bigger and badder than ever.

Prowling around, he came to the third little pig’s house. He crept up to the door and called:

'Little pig, little pig, let me come in.'

'Oh no, not by the hair on my chinny chin chin!' said the third little pig, while the first and the second little pigs hid trembling under the stairs.

'Then I’ll huff and I’ll puff and I’ll blow your house in!' said the wolf.

And he huffed, and he puffed and he blew but nothing happened. So he huffed and he puffed and he blew again, even harder, but still nothing happened. The brick house stood firm.

So he huffed and he puffed and he blew again, even harder, but still nothing happened. The brick house stood firm.

The wolf was very angry and getting even bigger and even badder by the minute.

'I’m going to eat you all,' he growled, 'just you wait and see.'

He prowled round the house trying to find a way in. The little pigs trembled when they saw his big eyes peering through the window. Then they heard a scrambling sound.

'Quick, quick!' said the third little pig. 'He’s climbing the tree. I think he’s going to come down the chimney.'

The three little pigs got the biggest pan they had, and filled it full of water and put it on the fire to boil. All the time they could hear the sound of the wolf climbing the tree and then walking along the roof.

The little pigs held their breath. The wolf was coming down the chimney. Nearer and nearer he came until, with a tremendous splash, he landed in the pan of water.

Nearer and nearer he came until, with a tremendous splash, he landed in the pan of water.

'Yoweeeee!' he screamed, and shot back up the chimney thinking his tail was on fire.

Three Little Pigs Short Story

Free Bedtime Stories & Short Stories for Kids

Three Little Pigs Short Story

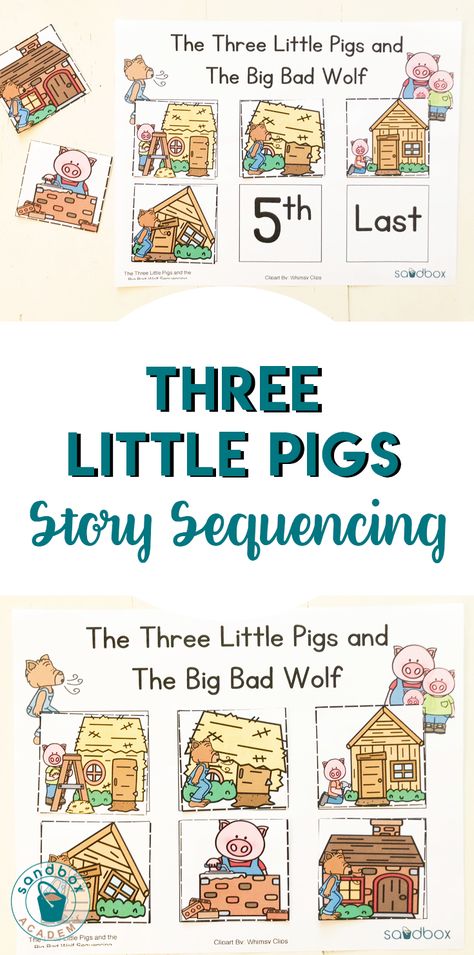

by Surbhit Chauhan in Age 0-3This is the three little pigs short story. Once upon a time, there were three little pigs and the time came for them to seek their fortunes and build their houses. The first little pig built his house of straw while the middle brother decided to build a house of sticks. They were done with building their houses very quickly and without much hard work.

The third pig who was the oldest amongst them decided to build a house of bricks. He did not mind doing some hard work because he wanted a strong house as he knew that in the woods nearby, there was a wolf who liked to catch little pigs and eat them up.

He did not mind doing some hard work because he wanted a strong house as he knew that in the woods nearby, there was a wolf who liked to catch little pigs and eat them up.

Also, read Three Little Pigs Song.

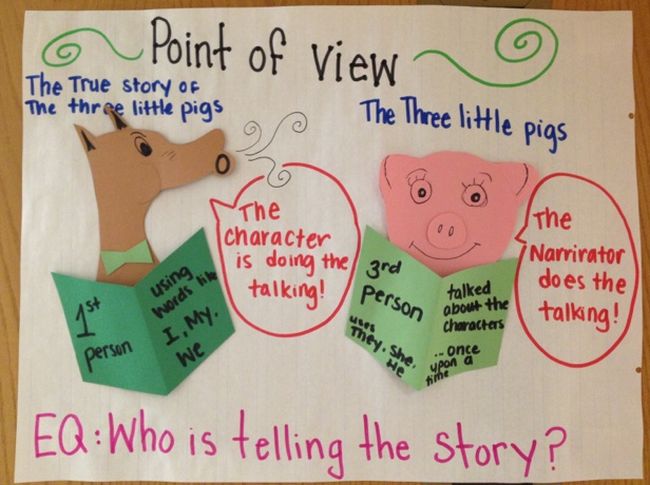

the true story of the three little pigs

When the three houses were finished, they sang and danced happily the whole day. After enjoying a lot, just as the first pig reached his door, a big bad wolf popped up from the woods. The little pig got scared and quickly hid in his house made of straws. The big bad wolf huffed and puffed and blew the house down in minutes.

Seeing this the little pig ran to his middle brother’s house made of sticks. The wolf now came to this house and huffed and puffed and blew the house down in hardly any time. Now, both the terrified pigs ran to their oldest brother’s house which was made of bricks.

Also, read The Yucky Pig.

The big bad wolf tried to huff and puff and blow the third house down, but he could not. He kept trying for hours but the house was very strong and all the three pigs were safe inside. He tried to enter through the chimney but the third pig boiled a big pot of water and kept it below the chimney. The wolf fell into it and died. The two young pigs felt sorry for being so lazy while building the houses. They also built their houses with bricks and all the three little pigs lived happily ever after.

He tried to enter through the chimney but the third pig boiled a big pot of water and kept it below the chimney. The wolf fell into it and died. The two young pigs felt sorry for being so lazy while building the houses. They also built their houses with bricks and all the three little pigs lived happily ever after.

Moral of the story: “Never shy away from doing hard work as hard work always pays off”.

Here is a short visual depiction of, “Three Little Pigs Short Story”. See the video story below,

Three Little Pigs Short Story videoTagged with: 3 little pigs short story, 3 pigs and a wolf, the three little pigs short story, the three little pigs story, the true story of the three little pigs, three little pigs, three little pigs and the big bad wolf, three little pigs children story, three little pigs for kids, three little pigs online, three little pigs original story, three little pigs story online read

The Truth About Pigs: We Made Them That Way

- Henry Nichols

- BBC Earth

Image copyright Thinkstock

Image captionWhen wallowing in the mud, a pig cleans its skin rather than soiling it

They have a reputation for being unclean animals that sweat profusely while wallowing in mud. In reality, they have outstanding abilities, as the correspondent BBC Earth .

In reality, they have outstanding abilities, as the correspondent BBC Earth .

It is said that: Pigs dig and sleep in feces. Pigs sweat like pigs. Pigs are dirty animals. A male pig (aka boar or knur) can experience an orgasm within half an hour.

Reality: Most of these stereotypes are best explained by poor conditions of detention. In the wild, wild boars do not sleep in or pick at feces. They fall out in the clay, but only because it is a great way to cool the body in the heat. Domestic pigs are often pink, but we humans made them that way. Males can ejaculate for minutes on end.

Photo copyright, Nick Turner NPL

Photo caption,Pigs don't have sweat glands, so the expression "sweats like a pig" doesn't make any sense. So said Jules Winfield, the Pulp Fiction mobster (played by Samuel Jackson), explaining why he doesn't eat pork.

If Winfield had known a little more about pigs, he might not have spoken so hastily and arrogantly about them.

Rabbits, for example, willingly swallow their fecal pellets in order to once again drive a poorly digestible herbal dinner through the digestive system.

And after all, it never occurs to anyone to speak rudely about eared and fluffy rodents.

Diet and hygiene

Wild boar, the original distant relative from which we have bred our domestic pigs, are omnivorous animals that do not show increased pickiness in food.

And yet, 90% of their diet consists of plant foods, so they are unlikely to have any special predilection for their own excrement.

If a domestic pig starts chewing excrement from time to time, this is most likely due to the fact that her dwelling littered with uncleaned sewage leaves her no other choice.

Photo copyright, Wild Wonders of Europe Zacek NPL

Image caption, A pig sometimes chews sewage, but wild boars were somehow caught washing apples in a stream , Switzerland, became famous for its cleanliness and legibility in food.

Animals were given slices of apples rolled in the sand. Instead of eating them immediately, the boars carried them to the banks of the stream that flowed through their enclosure, put the fruits in the water and rinsed them, pushing back and forth with their snouts before sitting down.

Boars would not do this procedure with clean apples. Even when they were very hungry, they found time to wash their food.

In addition to their food preferences, pigs enjoy a reputation as "dirty animals" in a more general sense.

Photo copyright Roger Powell NPL

Photo captionThe clay on the skin of the pig acts as a cream, protects against heat and insects

Boars do wallow in the clay, but most likely they do it to escape the heat.

The fact is that pigs do not have functioning sweat glands. It's worth remembering this whenever you hear someone say that he or she "sweats like a pig."

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

End of Story Podcast

This physiological feature means that pigs are at serious risk of overheating, and cloudy clay water evaporates much more slowly than clear water.

"A pig, like any other animal, tries to make itself comfortable," says Greger Larson of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. to find another solution, but the conditions for this have not been created, since people keep them in rather cramped pigsties.

The layer of clay on the skin can also serve other purposes, such as a cream to protect the surface of the body from burns, or to repel insects such as mosquitoes and others.

When a pig rubs against something, scraping off a crust of dried clay, this can be an effective way to get rid of mites and other parasites.

The paradox lies in the fact that, having rolled in the mud, they clean, not dirty their skin.

image copyrightNick Garbutt NPL

Image caption,The family suidae, or "pigs", has over a dozen different species

innovation.Both domestic pigs and their wild relatives, wild boars, are all members of the family of artiodactyl non-ruminant animals, scientifically called suidae, i.e. "pigs".

Extensive relatives

This family includes more than a dozen species, from the warthog to the pygmy pig; among them there is a babirussa (an animal with huge fangs that lives on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi), and there is also a large forest pig and an African brush-eared (aka river) pig.

Image copyright, Thinkstock

Image caption,Domestic pigs come in a wide variety of colors, but the most common is pinkish

Genetic evidence suggests that humans have domesticated wild boars twice. For this, two hereditary lines were used - one in Asia and the other in Europe.

For this, two hereditary lines were used - one in Asia and the other in Europe.

The division of the ancestors of modern wild boars began about one million years ago, i.e. long before domestication, which occurred about nine thousand years ago.

Despite their long separate existence, Asian and European wild boars have exactly the same camouflage color.

The same cannot be said for domestic pig breeds. The genetic code of their skins is very diverse and, accordingly, they show a great variety of shades and patterns of outer covers.

We've achieved this diversity in less than 10,000 years, Larson says. In a paper published in 2009, he and a colleague wrote that "humans have been selecting for rare mutations that would be destined for rapid extinction in the context of the wild."

In conclusion, one more popular myth should be addressed - that a male pig, a boar, is able to experience an orgasm within 30 minutes.

The first thing to say is that we don't know how males or females feel when they copulate. So any talk of "orgasm" is speculative.

A 2012 report on the top performing boars noted that they averaged 6 minutes of ejaculation. However, one male is said to have actually ejaculated for 31 minutes.

Read the original of this article in English is available on the website BBC Earth .

Almost like us. The whole truth about pigs - analytical portal POLIT.RU

Alpina non-fiction publishing house presents the book by the Norwegian historian and journalist Kristoffer Endresen “Almost like us. The whole truth about pigs ”(translated by Yana Matrosova).

Winston Churchill once said: “I like pigs. Dogs look up to us, cats look down, but pigs look at us as equals.” However, the relationship between people and pigs is not at all so simple. The pig for us is the living embodiment of everything dirty, vile, shameful and sinful. She was deftly removed from our field of vision, or rather, locked away from human eyes. The life of a pig on a large farm lasts only six months. Unlike cows, she is never destined to breathe fresh air in her whole life, but no one cares about that. At the same time, the pig is an indispensable model of the human body in medical science and the animal whose meat we eat most often in the last half century. Kristoffer Endresen traced the life path of piglets from birth to industrial slaughterhouse and turned the facts he collected into a fascinating story about gastronomic addiction and aversion, about food and moral choice. His book re-poses the question that people have been asking for centuries: where is the line that separates us from animals?

She was deftly removed from our field of vision, or rather, locked away from human eyes. The life of a pig on a large farm lasts only six months. Unlike cows, she is never destined to breathe fresh air in her whole life, but no one cares about that. At the same time, the pig is an indispensable model of the human body in medical science and the animal whose meat we eat most often in the last half century. Kristoffer Endresen traced the life path of piglets from birth to industrial slaughterhouse and turned the facts he collected into a fascinating story about gastronomic addiction and aversion, about food and moral choice. His book re-poses the question that people have been asking for centuries: where is the line that separates us from animals?

We offer you to read an excerpt from the story about the history of the pork ban.

It is still a big mystery to anthropologists why some people abstain from pork for cultural or religious reasons, and this topic is increasingly starting to concern us, representatives of Western civilization. So history decreed: once, after the domestication of a pig, it occurred to someone that it was impossible to eat it. The factual justification for this is known: in both Islam and Judaism, there is a ban on eating pork, enshrined in religious texts. But what served as a prerequisite for such a ban is a completely different question.

So history decreed: once, after the domestication of a pig, it occurred to someone that it was impossible to eat it. The factual justification for this is known: in both Islam and Judaism, there is a ban on eating pork, enshrined in religious texts. But what served as a prerequisite for such a ban is a completely different question.

No one knows exactly when the Pentateuch of Moses was compiled, but it can be said with a high degree of certainty that at least by 500 BC. e. it already existed. With regard to pigs, it says this: “Do not eat their meat and do not touch their corpses; they are unclean to you” 1 . A millennium later, the prohibition was repeated in the Koran: "...dead meat, or spilled blood, or the meat of a pig ... is filth" 2 . There are many versions explaining the ban. Let's start with perhaps the most common, according to which it is associated with health protection. The famous Jewish thinker Moses Maimonides was the first to speak about this, who in the 12th century. wrote that pork had a harmful effect on the body. Today, this explanation is supported by the knowledge that pork may contain trichinella - parasitic roundworms that can cause trichinosis in humans if the meat is poorly fried or cooked. A simple and understandable theory, but it cannot be called a plausible explanation, and the vast majority of seekers of the mystery of the origin of the ban agree with this. Trichinella was first discovered in 1835, and the fact that parasites cause disease was scientifically proven only several decades later. You can, of course, object: they say, in the old days people noticed the relationship between eating pork and symptoms, even if they did not know exactly what led to the disease, but it was hard to believe in it. Symptoms of trichinosis develop a few days after eating meat infested with larvae. If during this period a person managed to eat other meat, causal relationships are no longer so obvious. In addition, in terms of the degree of danger, pork was far from in the first place in those days.

wrote that pork had a harmful effect on the body. Today, this explanation is supported by the knowledge that pork may contain trichinella - parasitic roundworms that can cause trichinosis in humans if the meat is poorly fried or cooked. A simple and understandable theory, but it cannot be called a plausible explanation, and the vast majority of seekers of the mystery of the origin of the ban agree with this. Trichinella was first discovered in 1835, and the fact that parasites cause disease was scientifically proven only several decades later. You can, of course, object: they say, in the old days people noticed the relationship between eating pork and symptoms, even if they did not know exactly what led to the disease, but it was hard to believe in it. Symptoms of trichinosis develop a few days after eating meat infested with larvae. If during this period a person managed to eat other meat, causal relationships are no longer so obvious. In addition, in terms of the degree of danger, pork was far from in the first place in those days. Cows, sheep and goats - all of them could be carriers of a much more dangerous, even fatal disease - anthrax (pigs are practically not affected by it). It would be more logical to refrain from eating the meat of these animals, since people were so afraid of getting infected, but this, as you know, did not happen. If you continue to be afraid of trichinella and therefore refuse pork, know that these parasites have not been found in Norway since the beginning of 1990s, and even then the meat did not hit the market. Decades have passed since the last detection of trichinella. Most pigs pick up this parasite when they are free-ranging and encounter small rodents such as rats, mice and squirrels. Although there are quite a few mice snooping along the walls of Norwegian pigsties, it's nice to know that the chance of encountering Trichinella in industrial meat is actually much less than if we were dealing with pigs that could roam freely in nature.

Cows, sheep and goats - all of them could be carriers of a much more dangerous, even fatal disease - anthrax (pigs are practically not affected by it). It would be more logical to refrain from eating the meat of these animals, since people were so afraid of getting infected, but this, as you know, did not happen. If you continue to be afraid of trichinella and therefore refuse pork, know that these parasites have not been found in Norway since the beginning of 1990s, and even then the meat did not hit the market. Decades have passed since the last detection of trichinella. Most pigs pick up this parasite when they are free-ranging and encounter small rodents such as rats, mice and squirrels. Although there are quite a few mice snooping along the walls of Norwegian pigsties, it's nice to know that the chance of encountering Trichinella in industrial meat is actually much less than if we were dealing with pigs that could roam freely in nature.

A completely different explanation for the ban was put forward by the authoritative ethnographer Mary Douglas. The main thesis of her book "Purity and Danger" (Purity and Danger) 3 , published in 1966, was the statement: "Dirt is, in fact, a mess." Douglas shows how the concepts of "clean" and "impure" are reflected in different cultures. According to the ethnographer, our views on what is clean and what is not are determined by cultural norms of ownership of various objects. The stool belongs to the toilet, not the sink; lunch is served on plates, not on the table itself. Today, we associate hygiene mainly with such rules. In the old days, clean and unclean was more a matter of order and disorder.

The main thesis of her book "Purity and Danger" (Purity and Danger) 3 , published in 1966, was the statement: "Dirt is, in fact, a mess." Douglas shows how the concepts of "clean" and "impure" are reflected in different cultures. According to the ethnographer, our views on what is clean and what is not are determined by cultural norms of ownership of various objects. The stool belongs to the toilet, not the sink; lunch is served on plates, not on the table itself. Today, we associate hygiene mainly with such rules. In the old days, clean and unclean was more a matter of order and disorder.

Douglas believes that the pig violated the Jews' understanding of the order and system of nature. The researcher shows that in the rules of kashrut in Judaism, set forth in the book of Leviticus, a strict categorization of nature and the animal kingdom is visible. Its main principle was that land animals are either carnivores with paws or ruminants with cloven hooves. God says to Aaron: “These are the animals that you can eat from all the cattle on the earth: every cattle that has cloven hooves and a deep cut in the hooves, and that chews the cud, eat. ” 4 . The pig definitely has a “cut” on its hooves, but it does not chew the cud, so, along with several other land animals, it fell into disgrace. The pig turned out to be "essentially a mess", it spoiled the whole coherent "taxonomic" system.

” 4 . The pig definitely has a “cut” on its hooves, but it does not chew the cud, so, along with several other land animals, it fell into disgrace. The pig turned out to be "essentially a mess", it spoiled the whole coherent "taxonomic" system.

The main weakness of Douglas's version is seen in the possibility of easily changing cause and effect. Maybe it's not the Jewish notions of order that explain the "impurity" of the pig, but the whole system was built to reinforce and justify an already existing disgust. In a later edition, the author herself admitted the shakiness of the evidence base of her hypothesis: “In my reasoning about the Bible, I made several mistakes, which I deeply regret.” Archeology has played a major role in debunking this notion. Studying the data accumulated over several decades of excavations in the Middle East, scientists have traced a striking pattern. From about 1500 BC. e. bones of pigs are found less and less, and by 1200 BC. e. practically disappear. This leads to an important conclusion: pigs were disliked long before the inclusion in the Bible and the Koran of prohibitions on eating their meat. Moreover, on the basis of the same collected data, archaeologists discovered something else remarkable. Simultaneously with the gradual disappearance of pork from the diet, it increasingly included another type of meat - chicken. This coincidence leaves no doubt that we are talking about a systematic replacement. The fundamental question sounds like this: did they refuse pork in favor of chicken, or did they gladly replace the hated pork with chicken? Archaeologist Richard Redding opined that pork was replaced for purely economic reasons. Unlike cows, sheep and goats, which provide milk and wool, pigs are not valuable except for meat. However, there is a certain benefit: for every kilogram of beef and lamb, there are 43,000 and 51,000 liters of water drunk by animals, respectively, and no more than 6,000 liters will go per kilogram of pork.

This leads to an important conclusion: pigs were disliked long before the inclusion in the Bible and the Koran of prohibitions on eating their meat. Moreover, on the basis of the same collected data, archaeologists discovered something else remarkable. Simultaneously with the gradual disappearance of pork from the diet, it increasingly included another type of meat - chicken. This coincidence leaves no doubt that we are talking about a systematic replacement. The fundamental question sounds like this: did they refuse pork in favor of chicken, or did they gladly replace the hated pork with chicken? Archaeologist Richard Redding opined that pork was replaced for purely economic reasons. Unlike cows, sheep and goats, which provide milk and wool, pigs are not valuable except for meat. However, there is a certain benefit: for every kilogram of beef and lamb, there are 43,000 and 51,000 liters of water drunk by animals, respectively, and no more than 6,000 liters will go per kilogram of pork. According to Redding, this made keeping pigs a profitable business only as long as it was not possible to raise chickens. It takes no more than 3,500 liters of water to produce a kilogram of chicken. In addition, chickens bypass pigs in terms of protein content in meat: in 100 g of pork - 13 g, and in chicken - 19Since chickens also lay eggs, they are, of course, a serious competitor to pigs. It is quite possible that keeping chickens turned out to be so profitable that further pork production became simply unprofitable.

According to Redding, this made keeping pigs a profitable business only as long as it was not possible to raise chickens. It takes no more than 3,500 liters of water to produce a kilogram of chicken. In addition, chickens bypass pigs in terms of protein content in meat: in 100 g of pork - 13 g, and in chicken - 19Since chickens also lay eggs, they are, of course, a serious competitor to pigs. It is quite possible that keeping chickens turned out to be so profitable that further pork production became simply unprofitable.

Of course, Redding makes a very convincing case for all the benefits of keeping chickens, but still, his arguments alone do not explain well the imposition of a religious prohibition on pork meat. It is doubtful that pork has lost the nutritional competition as easily as Redding describes it. Although chicken contains more protein, pork wins in calories due to fat. It is for a modern society of abundance that fats are associated with something bad, in ancient times they played a primary role in human nutrition. And is the difference in 6 g of protein in pork and chicken so noticeable that people of those ancient times could determine it? Redding's theory also bears little resemblance to the fact that chicken meat was no longer new to the Middle East when it began replacing pork. Separate finds of bones of chicken legs date back as far as 3900 BC e. If chicken really was such a consummate meat, as Redding shows, why didn't the substitution come sooner? Why has this only been seen in the Middle East? And why did Muslims decide it was necessary to emphasize the ban on pork in the Koran, 1,500 years after the pig had virtually disappeared from the region?

And is the difference in 6 g of protein in pork and chicken so noticeable that people of those ancient times could determine it? Redding's theory also bears little resemblance to the fact that chicken meat was no longer new to the Middle East when it began replacing pork. Separate finds of bones of chicken legs date back as far as 3900 BC e. If chicken really was such a consummate meat, as Redding shows, why didn't the substitution come sooner? Why has this only been seen in the Middle East? And why did Muslims decide it was necessary to emphasize the ban on pork in the Koran, 1,500 years after the pig had virtually disappeared from the region?

In an effort to confirm his theory, Redding draws on the research of anthropologist Marvin Harris, who attaches great importance to the climatic and environmental conditions of the region. In ancient times, animal husbandry in the Middle East was expressed mainly in the fact that nomads grazed herds of cattle, sheep and goats on arid and barren lands between the rivers - Tigris, Euphrates, Nile and Jordan. By decree of the authorities, the shepherds drove their cattle to the cities, and there the food was already distributed centrally. This type of animal husbandry strongly contradicts the physiology of pigs: they do not graze in large areas, and where the nomads roamed, they do not have enough food. Unlike ruminants such as cows, sheep, and goats, which are able to find their food in bushes and isolated patches of grass, pigs depend on more nutritious and easily digestible food sources such as carrion, nuts, roots, and grains. And although conditions in the Middle East were slightly different 3000-4000 years ago, the region was still a sun-scorched land with a hot and dry climate. Pigs, devoid of sweat glands and completely dependent on the ability to cool off in the shade, water or mud, in such conditions it is almost impossible to survive. So these animals, being clumsy and swampy creatures, could never fit into the economy and food distribution policy of the centralized authorities.

By decree of the authorities, the shepherds drove their cattle to the cities, and there the food was already distributed centrally. This type of animal husbandry strongly contradicts the physiology of pigs: they do not graze in large areas, and where the nomads roamed, they do not have enough food. Unlike ruminants such as cows, sheep, and goats, which are able to find their food in bushes and isolated patches of grass, pigs depend on more nutritious and easily digestible food sources such as carrion, nuts, roots, and grains. And although conditions in the Middle East were slightly different 3000-4000 years ago, the region was still a sun-scorched land with a hot and dry climate. Pigs, devoid of sweat glands and completely dependent on the ability to cool off in the shade, water or mud, in such conditions it is almost impossible to survive. So these animals, being clumsy and swampy creatures, could never fit into the economy and food distribution policy of the centralized authorities.

Catering during the construction of the Egyptian pyramids is a clear example of this. For decades, the Egyptian pharaohs had to feed thousands of workers who cut down and laid blocks of stone for the glory of their rulers. The entire Nile Delta was involved, so cows, sheep, and goats were driven to Giza, where they were slaughtered and the meat was immediately distributed. Those who were not involved in construction got little meat. For those who remained on the margins of society, raising pigs became a way out. The same thing happened in Puzrish Dagan, an important city near Nippur, a religious center in modern-day Iraq. Approximately 4,000 years ago, there also existed a centralized economy and the population was highly dependent on food, which was distributed by the authorities. Tens of thousands of animals were driven into the city and slaughtered for provisions. Among them were cows, goats and sheep, but archaeologists did not find any traces of pigs.

For decades, the Egyptian pharaohs had to feed thousands of workers who cut down and laid blocks of stone for the glory of their rulers. The entire Nile Delta was involved, so cows, sheep, and goats were driven to Giza, where they were slaughtered and the meat was immediately distributed. Those who were not involved in construction got little meat. For those who remained on the margins of society, raising pigs became a way out. The same thing happened in Puzrish Dagan, an important city near Nippur, a religious center in modern-day Iraq. Approximately 4,000 years ago, there also existed a centralized economy and the population was highly dependent on food, which was distributed by the authorities. Tens of thousands of animals were driven into the city and slaughtered for provisions. Among them were cows, goats and sheep, but archaeologists did not find any traces of pigs.

From what has been said, we can conclude that in the first major civilizations, animal husbandry was a matter of class. Nomads who herded cattle and other ruminants formed the basis of the emerging market economy and were closely associated with the elites. Pigs, on the contrary, were kept by representatives of the lower strata of society. For those in power, pigs could represent poverty and an attempt to get out of control of the distribution economy. If the injunctions of the Pentateuch of Moses were crafted with power and political influence in mind, it's not unbelievable that the pork ban was a well-thought-out strategy to please those in power. In any case, one thing is clear: pork was never included in the diet of the ruling class and the townspeople, either in Mesopotamia or in Egypt.

Nomads who herded cattle and other ruminants formed the basis of the emerging market economy and were closely associated with the elites. Pigs, on the contrary, were kept by representatives of the lower strata of society. For those in power, pigs could represent poverty and an attempt to get out of control of the distribution economy. If the injunctions of the Pentateuch of Moses were crafted with power and political influence in mind, it's not unbelievable that the pork ban was a well-thought-out strategy to please those in power. In any case, one thing is clear: pork was never included in the diet of the ruling class and the townspeople, either in Mesopotamia or in Egypt.

2000 to 1500 BC e. Palestine experienced rapid population growth and urban development along the banks of the Jordan River. The process followed the same path as the entire urbanization of those times: the original habitats of pigs were under threat. Forests were cut down, valuable water was diverted from swamps to fields for growing vegetables. The pigs had no choice but to look for new habitats. As a result, many of them moved to the city streets, where, like dogs, they could hide from the sun in the shade of houses and eat garbage from the human table. In those days, when they didn’t really think about what to do with garbage, but they didn’t know about sanitation, a real holiday of abundance came for pigs and dogs. Almost everything they ate was associated with fundamental taboos for humans: feces, garbage and carrion. The natural reaction was disgust. A Babylonian text says, "The swine is unclean" because "the streets stink from it" and it "defiles the houses." It got to the point that in the 5th c. BC e. the ancient Greek historian Herodotus spoke of an Egyptian who was unfortunate enough to accidentally touch a pig. The unfortunate man immediately threw himself into the river in his clothes. Herodotus even points out that he knows a legend explaining such disgust, but he does not consider it proper to quote it. Pigs not only aroused disgust in people.

The pigs had no choice but to look for new habitats. As a result, many of them moved to the city streets, where, like dogs, they could hide from the sun in the shade of houses and eat garbage from the human table. In those days, when they didn’t really think about what to do with garbage, but they didn’t know about sanitation, a real holiday of abundance came for pigs and dogs. Almost everything they ate was associated with fundamental taboos for humans: feces, garbage and carrion. The natural reaction was disgust. A Babylonian text says, "The swine is unclean" because "the streets stink from it" and it "defiles the houses." It got to the point that in the 5th c. BC e. the ancient Greek historian Herodotus spoke of an Egyptian who was unfortunate enough to accidentally touch a pig. The unfortunate man immediately threw himself into the river in his clothes. Herodotus even points out that he knows a legend explaining such disgust, but he does not consider it proper to quote it. Pigs not only aroused disgust in people.