Teaching 1st grader to read

9 Fun and Easy Tips

With the abundance of information out there, it can seem like there is no clear answer about how to teach a child to read. As a busy parent, you may not have time to wade through all of the conflicting opinions.

That’s why we’re here to help! There are some key elements when it comes to teaching kids to read, so we’ve rounded up nine effective tips to help you boost your child’s reading skills and confidence.

These tips are simple, fit into your lifestyle, and help build foundational reading skills while having fun!

Tips For How To Teach A Child To Read

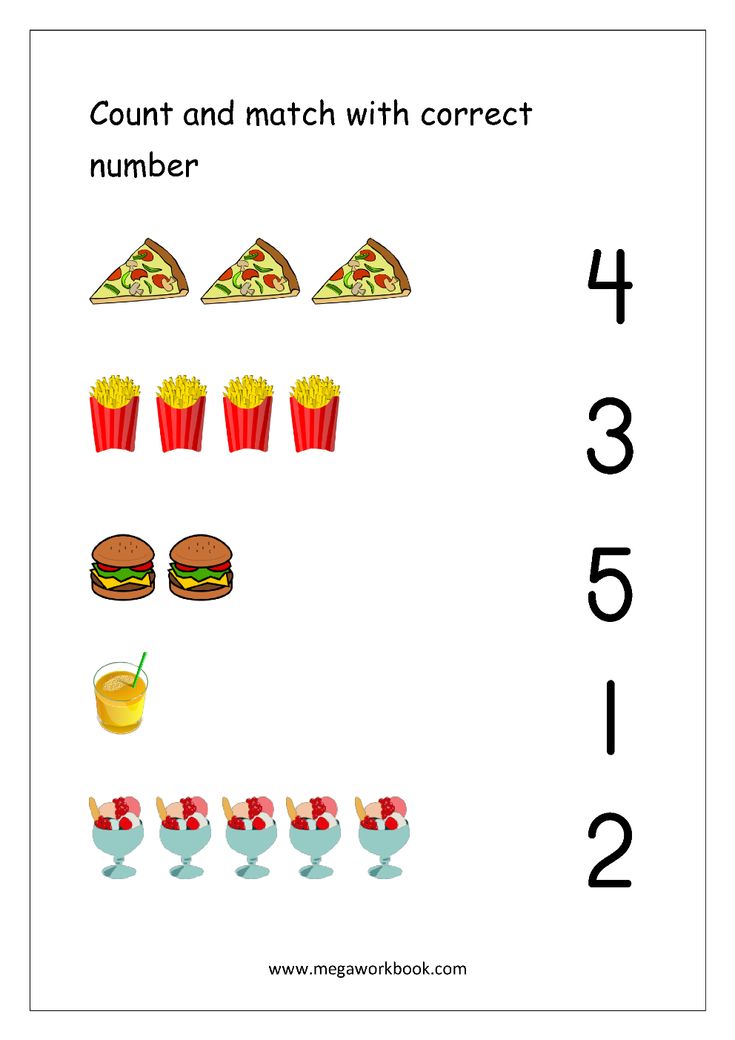

1) Focus On Letter Sounds Over Letter Names

We used to learn that “b” stands for “ball.” But when you say the word ball, it sounds different than saying the letter B on its own. That can be a strange concept for a young child to wrap their head around!

Instead of focusing on letter names, we recommend teaching them the sounds associated with each letter of the alphabet. For example, you could explain that B makes the /b/ sound (pronounced just like it sounds when you say the word ball aloud).

Once they firmly establish a link between a handful of letters and their sounds, children can begin to sound out short words. Knowing the sounds for B, T, and A allows a child to sound out both bat and tab.

As the number of links between letters and sounds grows, so will the number of words your child can sound out!

Now, does this mean that if your child already began learning by matching formal alphabet letter names with words, they won’t learn to match sounds and letters or learn how to read? Of course not!

We simply recommend this process as a learning method that can help some kids with the jump from letter sounds to words.

2) Begin With Uppercase Letters

Practicing how to make letters is way easier when they all look unique! This is why we teach uppercase letters to children who aren’t in formal schooling yet.

Even though lowercase letters are the most common format for letters (if you open a book at any page, the majority of the letters will be lowercase), uppercase letters are easier to distinguish from one another and, therefore, easier to identify.

Think about it –– “b” and “d” look an awful lot alike! But “B” and “D” are much easier to distinguish. Starting with uppercase letters, then, will help your child to grasp the basics of letter identification and, subsequently, reading.

To help your child learn uppercase letters, we find that engaging their sense of physical touch can be especially useful. If you want to try this, you might consider buying textured paper, like sandpaper, and cutting out the shapes of uppercase letters.

Ask your child to put their hands behind their back, and then place the letter in their hands. They can use their sense of touch to guess what letter they’re holding! You can play the same game with magnetic letters.

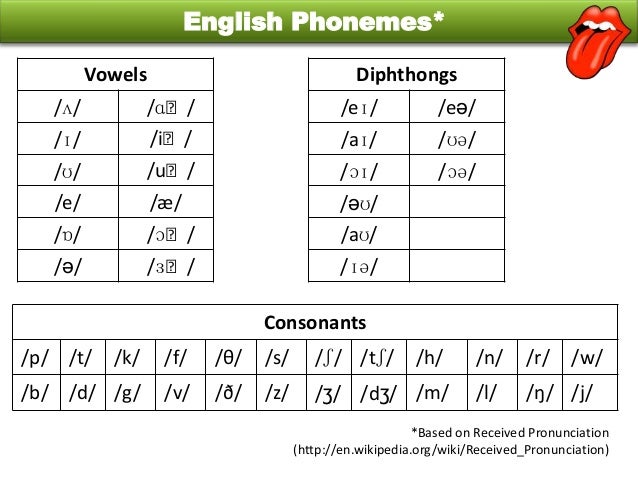

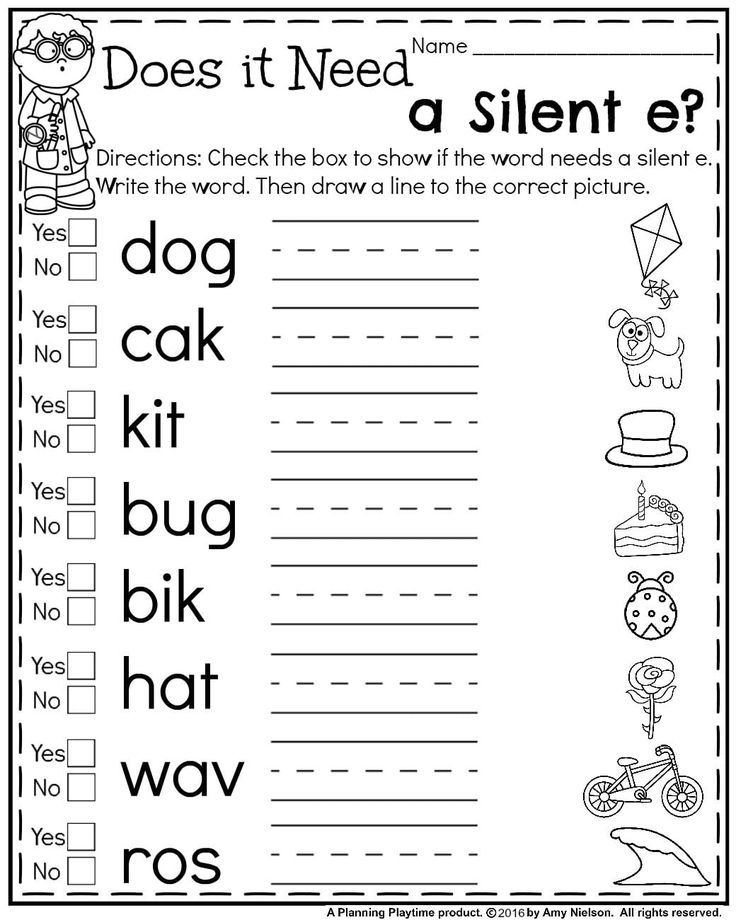

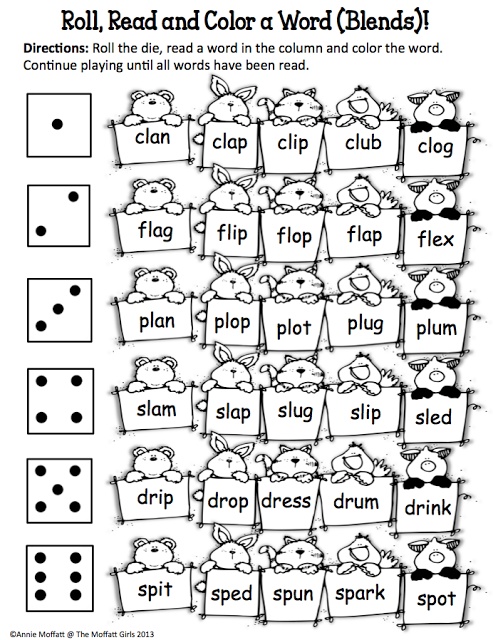

3) Incorporate Phonics

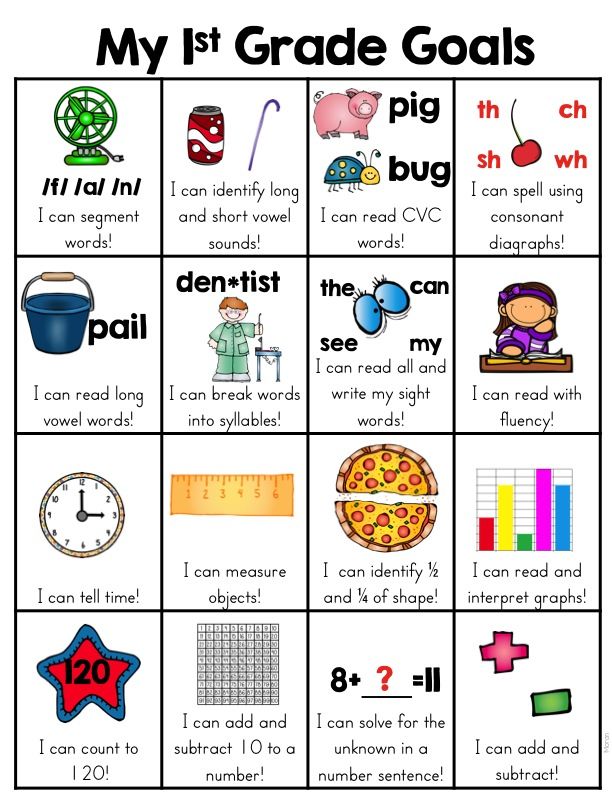

Research has demonstrated that kids with a strong background in phonics (the relationship between sounds and symbols) tend to become stronger readers in the long-run.

A phonetic approach to reading shows a child how to go letter by letter — sound by sound — blending the sounds as you go in order to read words that the child (or adult) has not yet memorized.

Once kids develop a level of automatization, they can sound out words almost instantly and only need to employ decoding with longer words. Phonics is best taught explicitly, sequentially, and systematically — which is the method HOMER uses.

If you’re looking for support helping your child learn phonics, our HOMER Learn & Grow app might be exactly what you need! With a proven reading pathway for your child, HOMER makes learning fun!

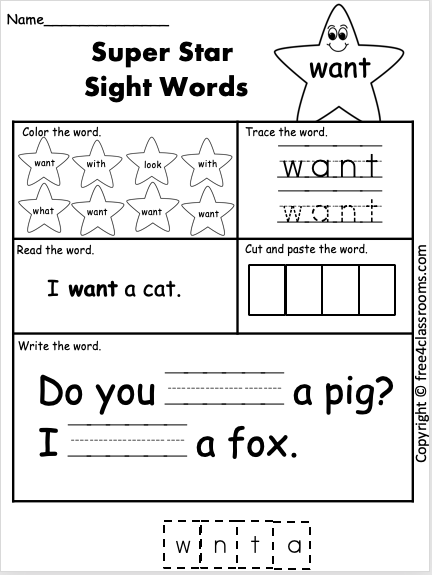

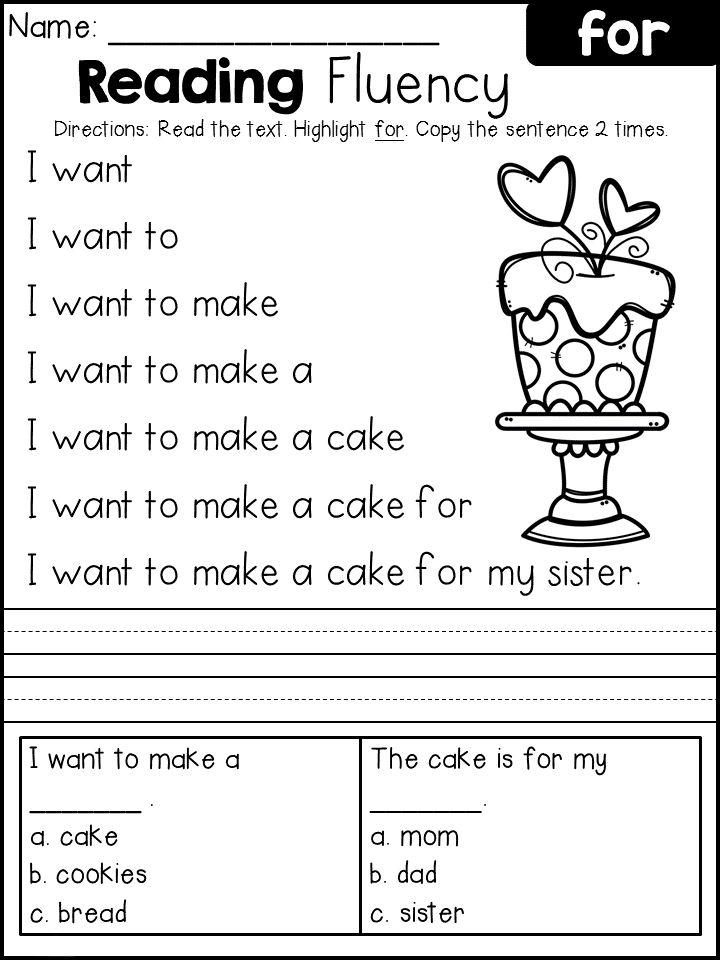

4) Balance Phonics And Sight Words

Sight words are also an important part of teaching your child how to read. These are common words that are usually not spelled the way they sound and can’t be decoded (sounded out).

Because we don’t want to undo the work your child has done to learn phonics, sight words should be memorized. But keep in mind that learning sight words can be challenging for many young children.

So, if you want to give your child a good start on their reading journey, it’s best to spend the majority of your time developing and reinforcing the information and skills needed to sound out words.

5) Talk A Lot

Even though talking is usually thought of as a speech-only skill, that’s not true. Your child is like a sponge. They’re absorbing everything, all the time, including the words you say (and the ones you wish they hadn’t heard)!

Talking with your child frequently and engaging their listening and storytelling skills can increase their vocabulary.

It can also help them form sentences, become familiar with new words and how they are used, as well as learn how to use context clues when someone is speaking about something they may not know a lot about.

All of these skills are extremely helpful for your child on their reading journey, and talking gives you both an opportunity to share and create moments you’ll treasure forever!

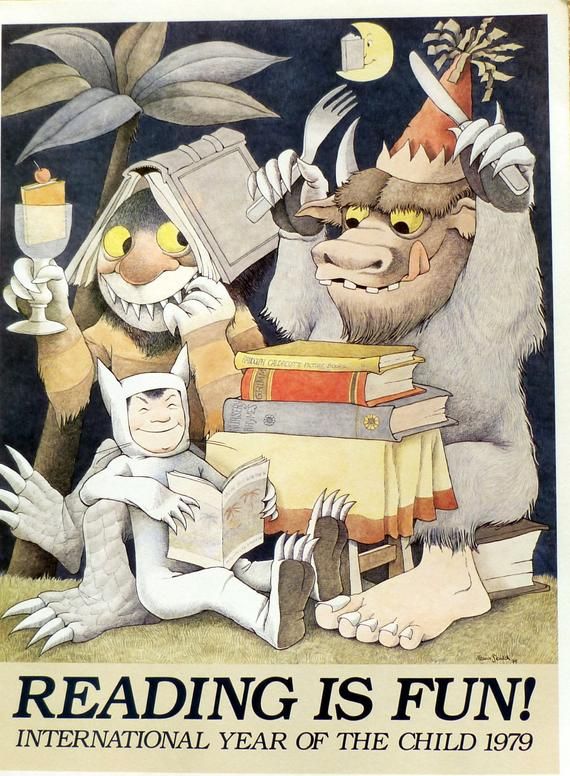

6) Keep It Light

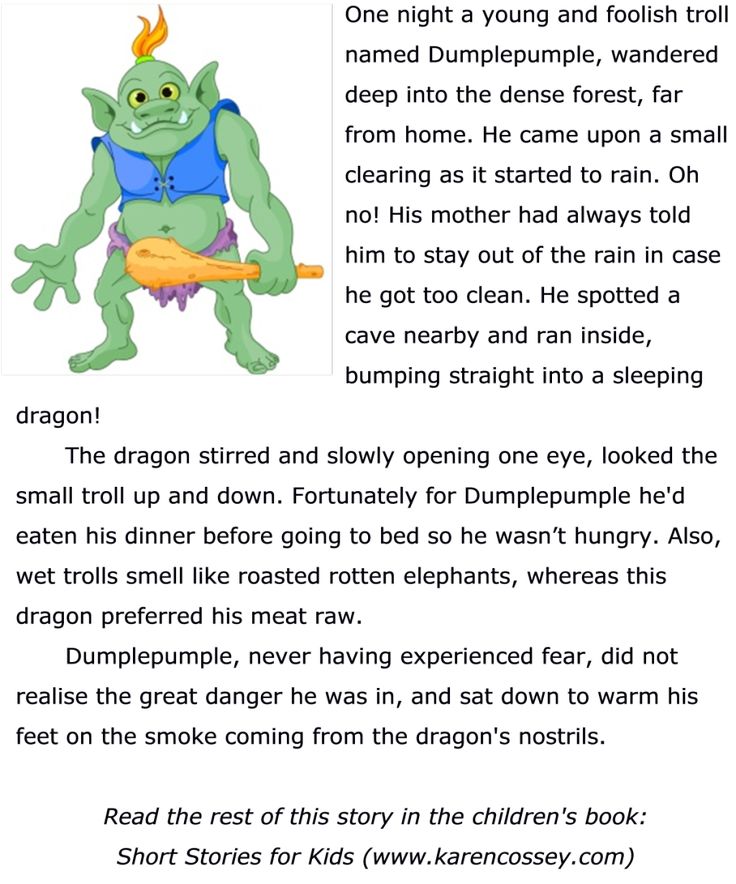

Reading is about having fun and exploring the world (real and imaginary) through text, pictures, and illustrations. When it comes to reading, it’s better for your child to be relaxed and focused on what they’re learning than squeezing in a stressful session after a long day.

We’re about halfway through the list and want to give a gentle reminder that your child shouldn’t feel any pressure when it comes to reading — and neither should you!

Although consistency is always helpful, we recommend focusing on quality over quantity. Fifteen minutes might sound like a short amount of time, but studies have shown that 15 minutes a day of HOMER’s reading pathway can increase early reading scores by 74%!

It may also take some time to find out exactly what will keep your child interested and engaged in learning. That’s OK! If it’s not fun, lighthearted, and enjoyable for you and your child, then shake it off and try something new.

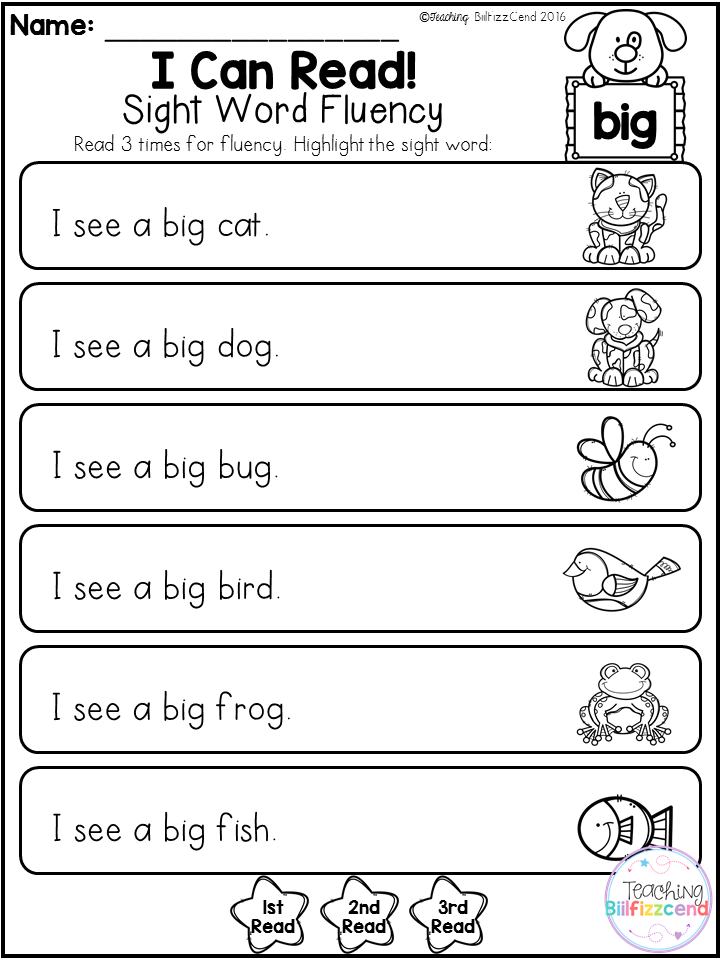

7) Practice Shared Reading

While you read with your child, consider asking them to repeat words or sentences back to you every now and then while you follow along with your finger.

There’s no need to stop your reading time completely if your child struggles with a particular word. An encouraging reminder of what the word means or how it’s pronounced is plenty!

Another option is to split reading aloud time with your child. For emerging readers, you can read one line and then ask them to read the next. For older children, reading one page and letting them read the next page is beneficial.

For emerging readers, you can read one line and then ask them to read the next. For older children, reading one page and letting them read the next page is beneficial.

Doing this helps your child feel capable and confident, which is important for encouraging them to read well and consistently!

This technique also gets your child more acquainted with the natural flow of reading. While they look at the pictures and listen happily to the story, they’ll begin to focus on the words they are reading and engage more with the book in front of them.

Rereading books can also be helpful. It allows children to develop a deeper understanding of the words in a text, make familiar words into “known” words that are then incorporated into their vocabulary, and form a connection with the story.

We wholeheartedly recommend rereading!

8) Play Word Games

Getting your child involved in reading doesn’t have to be about just books. Word games can be a great way to engage your child’s skills without reading a whole story at once.

One of our favorite reading games only requires a stack of Post-It notes and a bunched-up sock. For this activity, write sight words or words your child can sound out onto separate Post-It notes. Then stick the notes to the wall.

Your child can then stand in front of the Post-Its with the bunched-up sock in their hands. You say one of the words and your child throws the sock-ball at the Post-It note that matches!

9) Read With Unconventional Materials

In the same way that word games can help your child learn how to read, so can encouraging your child to read without actually using books!

If you’re interested in doing this, consider using PlayDoh, clay, paint, or indoor-safe sand to form and shape letters or words.

Another option is to fill a large pot with magnetic letters. For emerging learners, suggest that they pull a letter from the pot and try to name the sound it makes. For slightly older learners, see if they can name a word that begins with the same sound, or grab a collection of letters that come together to form a word.

As your child becomes more proficient, you can scale these activities to make them a little more advanced. And remember to have fun with it!

Reading Comes With Time And Practice

Overall, we want to leave you with this: there is no single answer to how to teach a child to read. What works for your neighbor’s child may not work for yours –– and that’s perfectly OK!

Patience, practicing a little every day, and emphasizing activities that let your child enjoy reading are the things we encourage most. Reading is about fun, exploration, and learning!

And if you ever need a bit of support, we’re here for you! At HOMER, we’re your learning partner. Start your child’s reading journey with confidence with our personalized program plus expert tips and learning resources.

Author

First Grade Instruction | Reading Rockets

It is during first grade that most children define themselves as good or poor readers. Unfortunately, it is also in first grade where common instructional practices are arguably most inconsistent with the research findings. This gap is reflected in the basal programs most commonly used in first-grade classrooms. The National Academy of Sciences report found that the more neglected instructional components of basal series are among those whose importance is most strongly supported by the research.

Unfortunately, it is also in first grade where common instructional practices are arguably most inconsistent with the research findings. This gap is reflected in the basal programs most commonly used in first-grade classrooms. The National Academy of Sciences report found that the more neglected instructional components of basal series are among those whose importance is most strongly supported by the research.

In this discussion, there are again certain caveats to keep in mind:

There is no replacing passionate teachers who are keenly aware of how their students are learning; research will never be able to tell teachers exactly what to do for a given child on a given day. What research can tell teachers, and what teachers are hungry to know, is what the evidence shows will work most often with most children and what will help specific groups of children.

To integrate research-based instructional practices into their daily work, teachers need the following:

Training in alphabetic basics

To read, children must know how to blend isolated sounds into words; to write, they must know how to break words into their component sounds. First-grade students who don't yet know their letters and sounds will need special catch-up instruction. In addition to such phonemic awareness, beginning readers must know their letters and have a basic understanding of how the letters of words, going from left to right, represent their sounds. First-grade classrooms must be designed to ensure that all children have a firm grasp of these basics before formal reading and spelling instruction begins.

First-grade students who don't yet know their letters and sounds will need special catch-up instruction. In addition to such phonemic awareness, beginning readers must know their letters and have a basic understanding of how the letters of words, going from left to right, represent their sounds. First-grade classrooms must be designed to ensure that all children have a firm grasp of these basics before formal reading and spelling instruction begins.

A proper balance between phonics and meaning in their instruction

In recent years, most educators have come to advocate a balanced approach to early reading instruction, promising attention to basic skills and exposure to rich literature. However, classroom practices of teachers, schools, and districts using balanced approaches vary widely.

Some teachers teach a little phonics on the side, perhaps using special materials for this purpose, while they primarily use basal reading programs that do not follow a strong sequence of phonics instruction. Others teach phonics in context, which means stopping from time to time during reading or writing instruction to point out, for example, a short a or an application of the silent e rule. These instructional strategies work with some children but are not consistent with evidence about how to help children, especially those who are most at risk, learn to read most effectively.

Others teach phonics in context, which means stopping from time to time during reading or writing instruction to point out, for example, a short a or an application of the silent e rule. These instructional strategies work with some children but are not consistent with evidence about how to help children, especially those who are most at risk, learn to read most effectively.

The National Academy of Sciences study, Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children, recommends first-grade instruction that provides explicit instruction and practice with sound structures that lead to familiarity with spelling-sound conventions and their use in identifying printed words. The bottom line is that all children have to learn to sound out words rather than relying on context and pictures as their primary strategies to determine meaning.

Does this mean that every child needs phonics instruction? Research shows that all proficient readers rely on deep and ready knowledge of spelling-sound correspondence while reading, whether this knowledge was specifically taught or simply inferred by students. Conversely, failure to learn to use spelling/sound correspondences to read and spell words is shown to be the most frequent and debilitating cause of reading difficulty. No one questions that many children do learn to read without any direct classroom instruction in phonics. But many children, especially children from homes that are not language rich or who potentially have learning disabilities, do need more systematic instruction in word-attack strategies.

Conversely, failure to learn to use spelling/sound correspondences to read and spell words is shown to be the most frequent and debilitating cause of reading difficulty. No one questions that many children do learn to read without any direct classroom instruction in phonics. But many children, especially children from homes that are not language rich or who potentially have learning disabilities, do need more systematic instruction in word-attack strategies.

Well-sequenced phonics instruction early in first grade has been shown to reduce the incidence of reading difficulty even as it accelerates the growth of the class as a whole. Given this, it is probably best to start all children, most especially in high-poverty areas, with explicit phonics instruction. Such an approach does require continually monitoring children's progress both to allow those who are progressing quickly to move ahead before they become bored and to ensure that those who are having difficulties get the assistance they need.

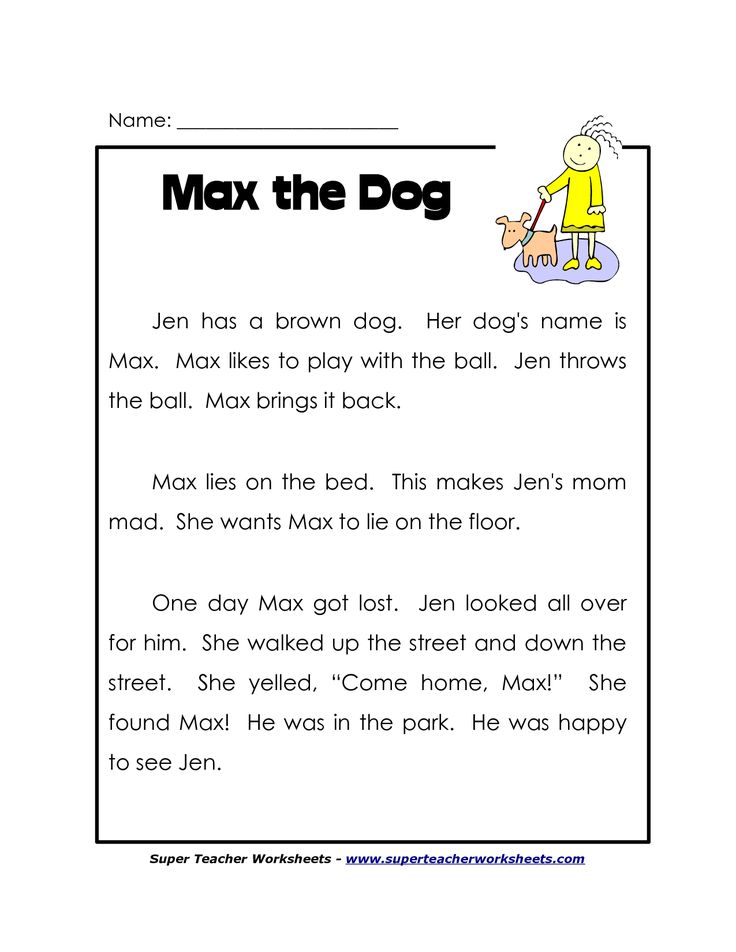

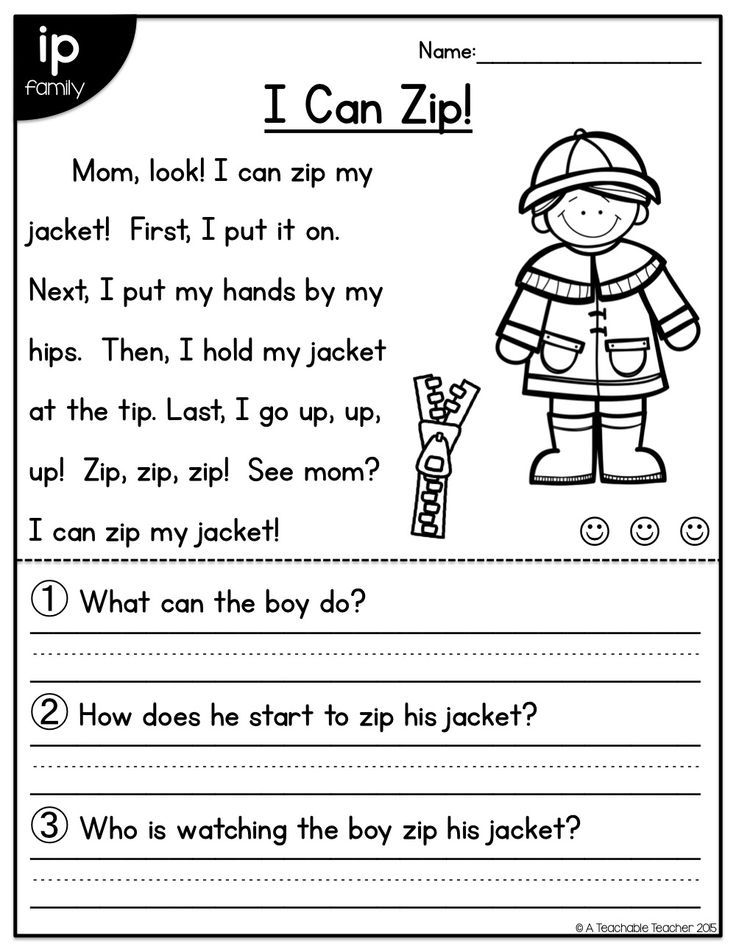

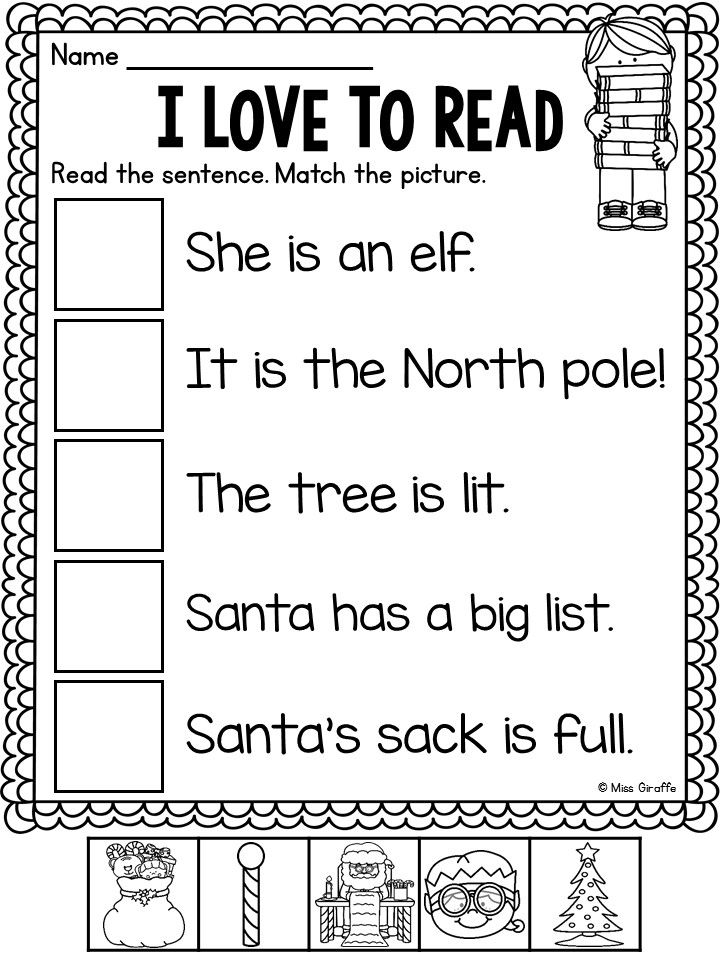

Strong reading materials

Early in first grade, a child's reading materials should feature a high proportion of new words that use the letter-sound relationships they have been taught. It makes no sense to teach decoding strategies and then have children read materials in which these strategies won't work. While research does not specify the exact percentage of words children should be able to recognize or sound out, it is clear that most children will learn to read more effectively with books in which this percentage is high.

On this point, the National Academy of Sciences report recommends that students should read well-written and engaging texts that include words that children can decipher to give them the chance to apply their emerging skills. It further recommends that children practice reading independently with texts slightly below their frustration level and receive assistance with slightly more difficult texts.

If the books children read only give them rare opportunities to sound out words that are new to them, they are unlikely to use sounding out as a consistent strategy. A study comparing the achievement of two groups of average-ability first-graders being taught phonics explicitly provides evidence of this. The group of children who used texts with a high proportion of words they could sound out learned to read much better than the group who had texts in which they could rarely apply the phonics they were being taught.

A study comparing the achievement of two groups of average-ability first-graders being taught phonics explicitly provides evidence of this. The group of children who used texts with a high proportion of words they could sound out learned to read much better than the group who had texts in which they could rarely apply the phonics they were being taught.

None of this should be read to mean that children should be reading meaningless or boring material. There is no need to return to Dan can fan the man. It's as important that children find joy and meaning in reading as it is that they develop the skills they need. Reading pleasure should always be as much a focus as reading skill. Research shows that the children who learn to read most effectively are the children who read the most and are most highly motivated to read.

The texts children read need to be as interesting and meaningful as possible. Still, at the very early stages, this is difficult. It isn't possible to write gripping fiction with only five letter sounds. But a meaningful context can be created by embedding decodable text in stories that provide other supports to build meaning and pleasure. For example, some early first-grade texts use pictures to represent words that students cannot yet decode. Others include a teacher text on each page, read by the teacher, parent, or other reader, which tells part of the story. The students then read their portion, which uses words containing the spelling-sound relationships they know. Between the two types of texts, a meaningful and interesting story can be told.

But a meaningful context can be created by embedding decodable text in stories that provide other supports to build meaning and pleasure. For example, some early first-grade texts use pictures to represent words that students cannot yet decode. Others include a teacher text on each page, read by the teacher, parent, or other reader, which tells part of the story. The students then read their portion, which uses words containing the spelling-sound relationships they know. Between the two types of texts, a meaningful and interesting story can be told.

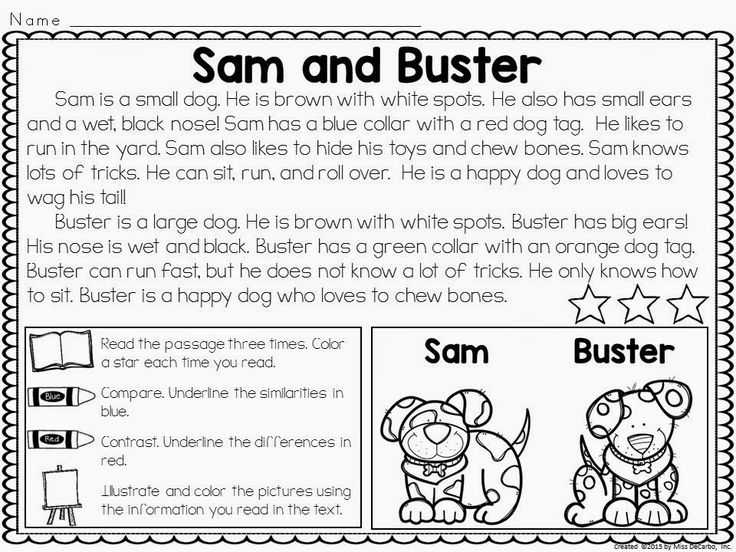

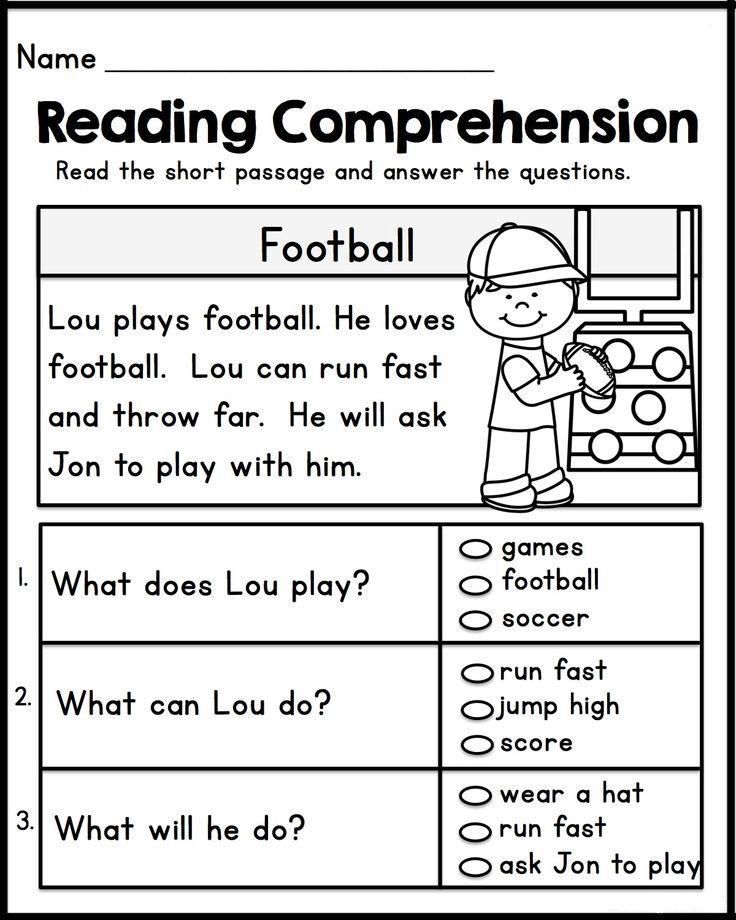

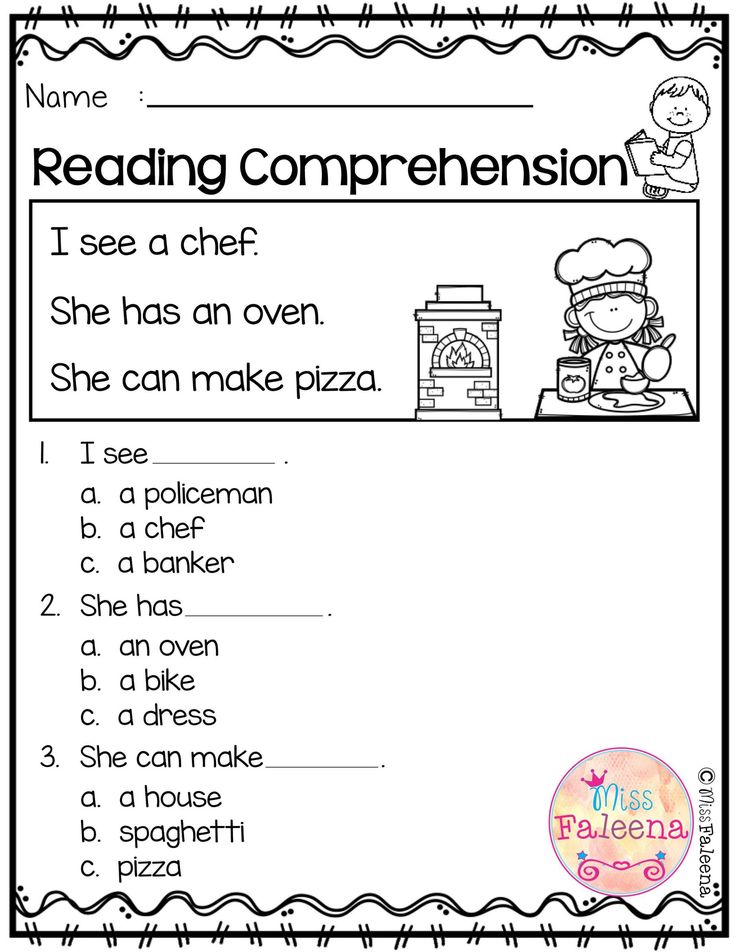

Strategies for teaching comprehension

Learning to read is not a linear process. Students do not need to learn to decode before they can learn to comprehend. Both skills should be taught at the same time from the earliest stages of reading instruction. Comprehension strategies can be taught using material that is read to children, as well as using material the children read themselves.

Before reading, teachers can establish the purpose for the reading, review vocabulary, activate background knowledge, and encourage children to predict what the story will be about. During reading, teachers can direct children's attention to difficult or subtle dimensions of the text, point out difficult words and ideas, and ask children to identify problems and solutions. After reading, children may be asked to retell or summarize stories, to create graphic organizers (such as webs, cause-and-effect charts, or outlines), to put pictures of story events in order, and so on. Children can be taught specific metacognitive strategies, such as asking themselves on a regular basis whether what they are reading makes sense or whether there is a one-to-one match between the words they read and the words on the page.

During reading, teachers can direct children's attention to difficult or subtle dimensions of the text, point out difficult words and ideas, and ask children to identify problems and solutions. After reading, children may be asked to retell or summarize stories, to create graphic organizers (such as webs, cause-and-effect charts, or outlines), to put pictures of story events in order, and so on. Children can be taught specific metacognitive strategies, such as asking themselves on a regular basis whether what they are reading makes sense or whether there is a one-to-one match between the words they read and the words on the page.

Writing programs

Creative and expository writing instruction should begin in kindergarten and continue during first grade and beyond. Writing, in addition to being valuable in its own right, gives children opportunities to use their new reading competence. Research shows invented spelling to be a powerful means of leading students to internalize phonemic awareness and the alphabetic principle. Still, while research shows that using invented spelling is not in conflict with teaching correct spelling, the National Academy of Sciences report does recommend that conventionally correct spelling be developed through focused instruction and practice at the same time students use invented spelling. The Academy report further recommends that primary grade children should be expected to spell previously studied words and spelling patterns correctly in final writing products.

Still, while research shows that using invented spelling is not in conflict with teaching correct spelling, the National Academy of Sciences report does recommend that conventionally correct spelling be developed through focused instruction and practice at the same time students use invented spelling. The Academy report further recommends that primary grade children should be expected to spell previously studied words and spelling patterns correctly in final writing products.

Smaller class size

Class size makes a difference in early reading performance. Studies comparing class sizes of approximately 15 to those of around 25 in the early elementary grades reveal that class size has a significant impact on reading achievement, especially if teachers are also using more effective instructional strategies. Reductions of this magnitude are expensive, of course, if used all day. An alternative is to reduce class size just during the time set aside for reading, either by providing additional reading teachers during reading periods or by having certified teachers who have other functions most of the day (e. g., tutors, librarians, or special education teachers) teach a reading class during a common reading period.

g., tutors, librarians, or special education teachers) teach a reading class during a common reading period.

Curriculum-based assessment

In first grade and beyond, regular curriculum-based assessments are needed to guide decisions about such things as grouping, the pace of instruction, and individual needs for assistance (such as tutoring). The purpose of curriculum-based assessment is to determine how children are doing in the particular curriculum being used in the classroom or school, not to indicate how children are doing on national norms. In first grade, assessments should focus on all of the major components of early reading: decoding of phonetically regular words, recognition of sight words, comprehension, writing, and so on.

Informal assessments can be conducted every day. Anything children do in class gives information to the teacher that can be used to adjust instruction for individuals or for the entire class. Regular schoolwide assessments based on students' current reading groups can be given every six to 10 weeks. These might combine material read to children, material to which children respond on their own, and material the child reads to the teacher individually. These school assessments should be aligned as much as possible with any district or state assessments students will have to take.

Effective grouping strategies

Children enter first grade at very different points in their reading development. Some already read, while others lack even the most basic knowledge of letters and sounds. Recognizing this, schools have long used a variety of methods to group children for instruction appropriate to their needs. Each method has its own advantages and disadvantages.

The most common method is to divide children within their own class into three or more reading groups, which take turns working with the teacher. The main problem with this strategy is that it requires follow-up time activities children can do on their own while the teacher is working with another group. Studies of follow-up time find that, all too often, it translates to busywork. Follow-up time spent in partner reading, writing, working with a well-trained paraprofessional, or other activities closely linked to instructional objectives may be beneficial; but teachers must carefully review workbook, computer, or other activities to be sure they are productive.

Another strategy is grouping within the same grade. For example, during reading time there might be a high, middle, and low second-grade group. The problem with this type of grouping is that it creates a low group with few positive models.

Alternatively, children in all grades can be grouped in reading according to their reading level and without regard to age. A second-grade-level reading class might include some first-graders, many second-graders, and a few third-graders. An advantage of this approach is that it mostly eliminates the low group problem, and gives each teacher one reading group. The risk is that some older children will be embarrassed by being grouped with children from a lower grade level. Classroom management and organization for reading instruction are areas that deserve further research and attention.

Tutoring support

Most children can learn to read by the end of first grade with good-quality reading instruction alone. In every school, however, there are children who need more assistance. Small-group remedial methods, such as those typical of Title I or special education resource room programs, have not generally been found to be effective in increasing the achievement of these children. One-to-one tutoring, closely aligned with classroom instruction, has been effective for struggling first-graders. While it is often best to have certified teachers working with children with the most serious difficulties, well-trained paraprofessionals can develop a valuable expertise for working with these children. Trained volunteers who are placed in well-structured, well-supervised programs also can be a valuable resource.

Home reading

Children should be spending more time on reading than is available at school. They should read at home on a regular basis, usually 20 to 30 minutes each evening. Parents can be asked to send in signed forms indicating that children have done their home reading. Many teachers ask that children read aloud with their parents, siblings, or others in first grade and then read silently thereafter. The books the children read should be of interest to them and should match their reading proficiency.

How to teach a child to read: important rules and effective techniques

October 26, 2022 Likbez Education

Teaching a preschooler to read without losing interest in books is real. Lifehacker has selected the best ways for responsible parents.

How to understand that it is time to teach a child to read

There are several signs of psychological readiness.

- The child speaks fluently in sentences and understands the meaning of what is said.

- The child understands directions: left-right, up-down.

For learning to read, it is important that the baby can follow the text from left to right and from top to bottom.

- The child distinguishes sounds (what speech therapists call developed phonemic hearing). Simply put, the baby will easily understand by ear where the house and the bow are, and where the tom and the hatch are.

- Your child pronounces all the sounds and has no speech problems.

Natalia Zharikova

Speech therapist with 33 years of experience

A child with speech therapy problems does not hear and does not distinguish similar sounds. From here come errors with speech, and subsequently with reading, and even more often with writing. It is very difficult for a parent to identify violations on their own, so usually a teacher or a speech therapist can point this out to them.

How to teach your child to read

Be patient and follow these simple guidelines.

Set an example

In a family where there is a culture and tradition of reading, children themselves will reach for books. Read not because it is necessary and useful, but because it is a pleasure for you.

Read together and discuss

Read aloud to the child and then look at the pictures together, encouraging them to interact with the book: “Who is this picture? Can you show me the cat's ears? And who is that standing next to her?” Older children can be asked more difficult questions: “Why did he do this? What do you think will happen next?"

Don't learn the letters as they are called in the alphabet

Instead, help your child remember the sound the letter makes. For example, you show the letter "m" and say: "This is the letter m (not em )". If a child remembers the alphabetic names of letters ( em , es, ef and so on), it will be quite difficult for him to learn to read. Then, when he sees the word ra-ma in the book, he will try to pronounce er-a-um-a .

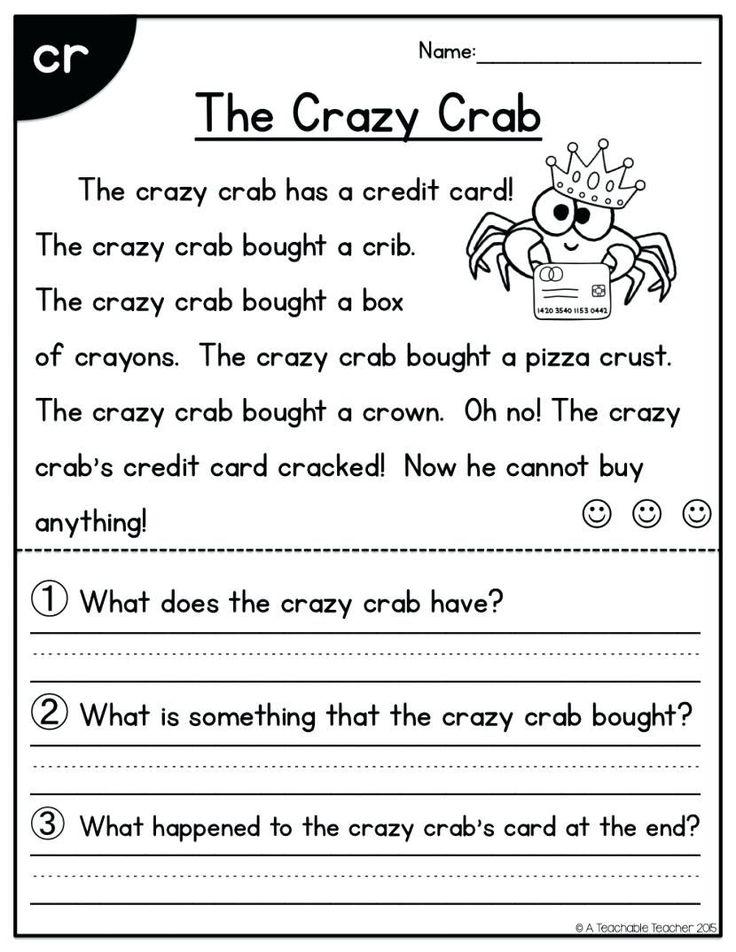

Go from simple to complex

Once the child has memorized a few letters (from 2 to 5) and the sounds they represent, move on to syllables. Let the words consisting of repeated syllables be the first: mum, dad, uncle, nanny . In this case, it is not necessary to break the syllable into separate sounds. Do not say: "These are the letters m and a , and together they read ma ". Immediately learn that the syllable is pronounced like ma , otherwise the baby may start to read letter by letter. After mastering simple combinations, move on to more complex ones: cat, zhu-k, house .

Help to understand the meaning of what they read

Do this when the child begins to slowly but surely reproduce words and whole sentences in syllables. For example, the kid read: "Mom washed the frame." Stop and ask: “What did you just read about?”. If he finds it difficult to answer, let him read the sentence again. And you ask more specific questions: “Who washed the frame? What did mom wash?

Show that letters are everywhere

Play a game. Let the child find the letters that surround him on the street and at home. These are the names of stores, and memos on information stands, and advertising on billboards, and even traffic light messages: it happens that the inscription “Go” lights up on green, and “Wait so many seconds” on red.

Play

And play again. Stack blocks with letters and syllables, make up words, ask your child to read you some kind of sign or inscription on the packaging in the store.

Natalia Zharikova

There are many exercises for memorizing letters. For example, circle the desired letter among a number of others, circle the correctly written among the incorrect ones, color or shade. You can also ask the child to tell what the letter looks like.

Use every opportunity to practice

Whether you are waiting in line at the clinic or driving somewhere, take out a book with pictures and short stories to accompany them and invite your child to read together.

Build on your success

Repeat familiar texts, look for familiar characters in new stories. Runaway Bunny is found both in "Teremka" and "Kolobok".

Do not force

This is perhaps the most important thing. Don't take away a child's childhood. Learning should not go through violence and tears.

What techniques to use to teach your child to read

Here are six popular, affordable and effective techniques. Choose one or try several and choose the one that interests your child the most.

1. ABCs and primers

Frame: This is all mine / YouTubeTraditional, but the longest way. The difference between these books is that the alphabet fixes each letter with a mnemonic picture: a drum will be drawn on the page with B , and a spinning top next to Yu . The alphabet helps to remember letters and often interesting rhymes, but will not teach you how to read.

The primer consistently teaches the child to combine sounds into syllables, and syllables into words. This process is not easy and requires perseverance.

There are quite a lot of author's primers now. According to the books of Nadezhda Betenkova, Vseslav Goretsky, Dmitry Fonin, Natalya Pavlova, children can study both with their parents before school and in the first grade.

Parents agree that one of the most understandable methods for teaching preschoolers is Nadezhda Zhukova's primer. The author simply explains the most difficult thing for a child: how to turn letters into syllables, how to read ma-ma , and not start naming individual letters me-a-me-a .

2. Zaitsev's Cubes

Shot: Little Socrates / YouTubeIf a child consistently masters letters and syllables while learning from an ABC book, then in 52 Zaitsev's Cubes he is given access to everything at once: a single letter or combinations of consonant and vowel, consonant and hard or soft sign.

The child effortlessly learns the differences between voiceless and voiced sounds, because the cubes with voiceless consonants are filled with wood, and the cubes with voiced consonants are filled with metal.

![]()

The cubes also differ in size. The large ones depict hard warehouses, the small ones - soft ones. The author of the technique explains this by the fact that when we pronounce to (hard warehouse), the mouth opens wide, nor (soft warehouse) - lips in a half smile.

The set includes tables with warehouses that the parent sings (yes, he doesn’t speak, but sings).

The child quickly masters warehouse reading with the help of cubes. But there are also disadvantages: he may begin to swallow endings and face difficulties already at school when parsing a word by composition.

3. "Skladushki" and "Teremki" by Vyacheslav Voskobovich

Frame: Play and Toy Club / YouTube In "Skladushki" Vyacheslav Voskobovich reworked Zaitsev's idea: 21 cards show all the warehouses of the Russian language with nice thematic pictures. Included is a CD with songs, the texts of which go under each picture.

Folders are great for kids who like looking at pictures. Each of them is an occasion to discuss with the child where the kitten is, what the puppy is doing, where the beetle flew.

It is possible to teach a child with these cards from the age of three. At the same time, it should be noted that the author of the methodology himself does not consider it necessary to force early development.

"Teremki" by Voskobovich consist of 12 wooden cubes with consonants and 12 cardboard cubes with vowels. First, the child gets acquainted with the alphabet and tries with the help of parents to come up with words that begin with each of the letters.

Then it's time to study the syllables. In the tower with the letter M is embedded A - and the first syllable is ma . From several towers you can lay out words. Learning is based on play. So, when replacing the vowel , house will turn into smoke .

You can start playing tower blocks from the age of two. At the same time, parents will not be left alone with the cubes: the kit includes a manual with a detailed description of the methodology and game options.

4. Chaplygin's dynamic cubes

Shot: Both a boy and a girl! Children's channel - We are twins / YouTubeEvgeny Chaplygin's manual includes 10 cubes and 10 movable blocks. Each dynamic block consists of a pair - a consonant and a vowel. The task of the child is to twist the cubes and find a pair.

At the initial stage, as with any other method of learning to read in warehouses, the child makes the simplest words from repeating syllables: ma-ma, pa-pa, ba-ba . The involved motor skills help to quickly remember the shape of the letters, and the search for already familiar syllables turns into an exciting game. The cubes are accompanied by a manual describing the methodology and words that can be composed.

The optimal age for classes is 4-5 years. You can start earlier, but only in the game format.

5. Doman's cards

Frame: My little star / YouTubeAmerican doctor Glenn Doman suggests teaching children not individual letters or even syllables, but whole words. Parents name and show the child the words on the cards for 1-2 seconds. In this case, the baby is not required to repeat what he heard.

Classes start with 15 cards with the simplest concepts like females and males . Gradually, the number of words increases, those already learned leave the set, and the child begins to study phrases: for example, color + object, size + object.

How can one understand that a child has understood and memorized the visual image of a word, if the author of the methodology recommends starting classes from birth? Glenn Doman in "The Harmonious Development of the Child" strongly emphasizes that it is not necessary to arrange tests and checks for the child: kids do not like this and lose interest in classes.

It's better to remember 50 cards out of 100 than 10 out of 10.

Glenn Doman

But given that parents can't help but check, he advises the child to play the game if they want and are ready. For example, you can put a few cards and ask to bring one or point to it.

Today, psychologists, neurophysiologists and pediatricians agree that the Doman method is aimed not at teaching reading, but at mechanical memorization of visual images of words. The child turns out to be an object of learning and is almost deprived of the opportunity to learn something on his own.

It is also worth adding: in order to proceed to the stage of reading according to Doman, parents need to prepare cards with all (!) Words that are found in a particular book.

6. Montessori method

Photo: Kolpakova Daria / Shutterstock Montessori reading comes from the opposite: first we write and only then we read. Letters are the same pictures, so you first need to learn how to draw them and only then engage in pronunciation and reading. Children begin by tracing and shading the letters, and through this, they memorize their outline. When several vowels and consonants have been studied, they move on to the first simple words.

Much attention is paid to the tactile component, so children can literally touch the alphabet cut out of rough or velvety paper.

The value of the method lies in learning through play. So, you can put a rough letter and a plate of semolina in front of the child and offer to first circle the sign with your finger, and then repeat this on the semolina.

The challenge for parents is purchasing or stocking up a significant amount of handouts. But you can try to make cards with your own hands from cardboard and sandpaper.

What's the result

On the Internet and on posters advertising "educators", you will be offered ultra-modern methods of teaching your child to read at three, two years old or even from birth. But let's be realistic: a happy mother is needed a year, not developmental activities.

The authors of the methods as one insist that the most natural learning process for a child is through play, and not through classes in which the parent plays the role of a strict controller. Your main assistant in learning is the curiosity of the child himself.

Some children will study for six months and start reading at three, others have to wait a couple of years to learn in just a month. Focus on the interests of the child. If he likes books and pictures, then primers and Folders will come to the rescue. If he is a fidget, then cubes and the Montessori system are better suited.

In learning to read, everything is simple and complex at the same time. If your child often sees you with a book, you have a tradition of reading before bed, your chances of getting your baby interested in reading will increase significantly.

See also 🧐

- How to teach a child to keep promises

- How to teach a child to say the letter "r"

- How to teach a child to ride a bicycle

- How to teach a child to swim

- How to teach a child to write

How to teach a child to read: techniques from an experienced teacher

At what age should children start learning to read?

“But still, the starting point for the first steps in this matter should not be a specific age, but the child himself. There are children who are ready to master the skill as early as 3-4 years old, and there are those who "mature" closer to grade 1. Once I worked with a boy who could not read at 6.5 years old. He knew letters, individual syllables, but he could not read. As soon as we began to study, it became clear that he was absolutely ready for reading, in two months he began to read perfectly in syllables, ”said Speranskaya.

How to teach a child to read quickly and correctly

The first thing you need to teach your baby is the ability to correlate letters and sounds. “In no case should a child be taught the names of letters, as in the alphabet: “em”, “be”, “ve”. Otherwise, training is doomed to failure. The preschooler will try to apply new knowledge in practice. Instead of reading [mom], he will read [me-a-me-a]. You are tormented by retraining, ”the speech therapist warned.

Therefore, it is important to immediately give the child not the names of the letters, but the sounds they represent. Not [be], but [b], not [em], but [m]. If the consonant is softened by a vowel, then this should be reflected in the pronunciation: [t '], [m'], [v '], etc.

To help your child remember the graphic symbols of letters, make a letter with him from plasticine, lay it out using buttons, draw with your finger on a saucer with flour or semolina. Color the letters with pencils, draw with water markers on the side of the bathroom.

“At first it will seem to the child that all the letters are similar to each other. These actions will help you learn to distinguish between them faster, ”said the speech therapist.

As soon as the baby remembers the letters and sounds, you can move on to memorizing syllables.

close

100%

How to teach your child to join letters into syllables

“Connecting letters into syllables is like learning the multiplication table. You just need to remember these combinations of letters, ”the speech therapist explained.

Naya Speranskaya noted that most of the manuals offer to teach children to read exactly by syllables. When choosing, two nuances should be taken into account:

1. Books should have little text and a lot of pictures.

2. Words in them should not be divided into syllables using large spaces, hyphens, long vertical lines.

“All this creates visual difficulties in reading. It is difficult for a child to perceive such a word as something whole, it is difficult to “collect” it from different pieces. It is best if there are no extra spaces or other separating characters in the word, and syllables are highlighted with arcs directly below the word, ”the speech therapist explained.

According to Speranskaya, cubes with letters are also suitable for studying syllables - playing with them, the child will quickly remember the combinations.

Another way to gently help your child learn letters and syllables is to print them in large print on paper and hang them all over the apartment.

“Hang them on the refrigerator, on the board in the nursery, on the wall in the bathroom. When such leaflets are hung throughout the apartment, you can inadvertently return to them many times a day. Do you wash your hands? Read what is written next to the sink. Is the child waiting for you to give him lunch? Ask him to name which syllables are hanging on the refrigerator. Do a little, but as often as possible. Step by step, the child will learn the syllables, and then slowly begin to read,” the specialist said.

Speranskaya is sure that in this way the child will learn to read much faster than after daily classes, when parents seat the child at the table with the words: "Now we will study reading ..."

“If it is really difficult for you to give up such activities, then pay attention that the nervous system of preschoolers is not yet ripe for long and monotonous lessons. Children spend enormous efforts on the analysis of graphic symbols. Learning to read for them is like learning a very complex cipher. Therefore, it is necessary to observe clear timing in such classes. At 5.5 years old, children are able to hold attention for no more than 10 minutes, at 6.5 years old - 15 minutes. That's how long one lesson should last. And there should be no more than one such “lessons” a day, unless, of course, you want the child to lose motivation for learning even before school,” the speech therapist explained.

How to properly explain to a child how to divide words into syllables

When teaching a child to divide words into syllables, use a pencil. Mark syllables with a pencil using arcs.

close

100%

“Take the word dinosaur. It can be divided into three syllables: "di", "but", "zavr". The child will read the first syllables without difficulty, but it will be difficult for him to master the third. The kid cannot look at three or four letters at once. Therefore, I propose to teach to read not entirely by syllables, but by the so-called syllables. This is when we learn to read combinations of consonants and vowels, and we read the consonants separately. For example, we will read the word "dinosaur" like this: "di" "but" "for" "in" "p" The last two letters are read separately from "for". If you immediately teach a child to read by syllables, he will quickly master complex words and move on to fluent reading, ”the speech therapist is sure.

In a text, syllables can be denoted in much the same way as syllables. Vowel + consonant with the help of an arc, and a separate consonant with the help of a dot.

Naya Speranskaya gave parents a recommendation to memorize syllables/syllable fusions for as long as possible, and move on to texts only when the child suggests it himself.

“If a preschooler is not eager to read, then there is no need to put pressure on him. Automate syllables. Take your time. Learning should take place gradually, from simple to complex. The reading technique develops over time, ”added Speranskaya.

Another important clarification from the speech therapist: when the child begins to read words and then sentences, parents need to clarify the meaning of what they read.