The important book read aloud

The Important Book - Teaching Children Philosophy

by Margaret Wise Brown

FILTERS: reality, grade-1-2, prek-k

Book Module Navigation

Summary »

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion »

Questions for Philosophical Discussion »

Activity Suggestion »

Summary

The Important Book introduces the difference between “essential” and “accidental” properties of things.The important thing about everyday objects like apples and glasses of water is presented in this funny and eye-opening book.

Read aloud video by AHEV Library

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

The Important Book raises the question of whether everything that exists has an essential property. The distinction between essential and accidental properties dates back to the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle. Aristotle thought that there were certain features of a thing–its essential properties–that it could not lose to still be the thing it was.

Other properties can be altered without changing the nature of the thing. Think about hair color. You can remain yourself even if you dye your hair. But what about more significant features of yourself, such as your personality or your central interest? Could you still be you even if you no longer enjoyed listening to opera or whatever is your passion?

In thinking about whether things have essential properties or not, it is important to distinguish different types of things. It’s pretty clear that implements or artifacts–things that we have created–have an essence. A knife can only be a knife so long as it can cut. But natural things are different. Can something be an apple if it’s not round? Sure. In fact, most apples are not really round, if that means spherical. And we can certainly imagine scientists creating an apple with a flat side so it will sit still on your kitchen table. So, is there any property that an apple has to have to be an apple? This is the sort of question that the children will have fun discussing even as they learn to think more deeply about the nature of things. (Since apples hold the tree’s seeds, might that be its most important property?)

(Since apples hold the tree’s seeds, might that be its most important property?)

People are, of course, the most complex. The Important Book says that the most important thing about you is that you are you. What exactly does this mean? It’s hard to say, but it is still a fun thing to discuss. Is there something that makes each of us the individuals we are? One important German philosopher, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, thought that everything that is true of us is equally important to making us the individuals that we are. Most of us would disagree. But then what do you think the most important thing about you is–the thing that makes you you?

In discussing this book with children, it’s important to let them say that the book is wrong about what’s most important about some things. This gives them the opportunity to see that books are not always right, that they may have more insight into a question than the book (or even its author) does.

We’ve structured the discussion of this book differently than that of most of the other books on this website. Starting with the activity we describe will make it easier to raise the deep metaphysical issues discussed by this book.

Starting with the activity we describe will make it easier to raise the deep metaphysical issues discussed by this book.

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

A good way to begin discussing this book is to ask the children to make a chart with you on large paper or a blackboard. There should be three columns: Object, Most Important Thing, Other Things. Then go through some (or all, depending on time) of the objects that the book discusses and fill out the chart, listing the object, what the book says are the most important things about the object, and what the book says are other things that are true of the object. Make sure to include one created thing like a spoon, one natural thing like an apple, and “you.” Once you’ve done this–or, perhaps, as you are filling out the chart–ask the children if they agree with what the book says. The idea is to get them to think about two things. First, is the book right in its classification of the most important thing about an object? Generally, they will see that they don’t agree with what the book said. Second, is there actually a “most important thing” about the object in question? Here, they probably will at least disagree about what is most important about the things we are discussing. You might ask them the following:

Second, is there actually a “most important thing” about the object in question? Here, they probably will at least disagree about what is most important about the things we are discussing. You might ask them the following:

The book says that the most important thing about a spoon is that you eat with it.

- Have you ever seen a spoon that is not a spoon that you eat with?

- What are some other things about spoons that are important?

- Is there one “most important” thing about a spoon? If so, what is it and why? If not, why not?

The book says that the most important thing about an apple is that it is round.

- What are some other important things about apples?

- Is being round the most important thing about an apple?

- Could something be an apple and have some other shape?

- Is there one most important thing about being an apple?

The book says that the most important thing about you is that you are you.

- Tell us one very important thing about you.

- Could you still be you and not possess that very important thing?

- What makes you you?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Thomas Wartenberg. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.

Activity Suggestion

Ask the students to choose any item in the classroom, list some of its properties, and say whether there is one “most important property.”

Download & PrintEmail Book Module Back to All Books

Reading Aloud to Build Comprehension

Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown is a beloved children's bedtime story. Young children instantly relate to the struggle of the little bunny trying to get to sleep. Such stories are memorable because they move children and allow them to make personal connections that inspire them to think more deeply, to feel more wholeheartedly, and to become more curious listeners.

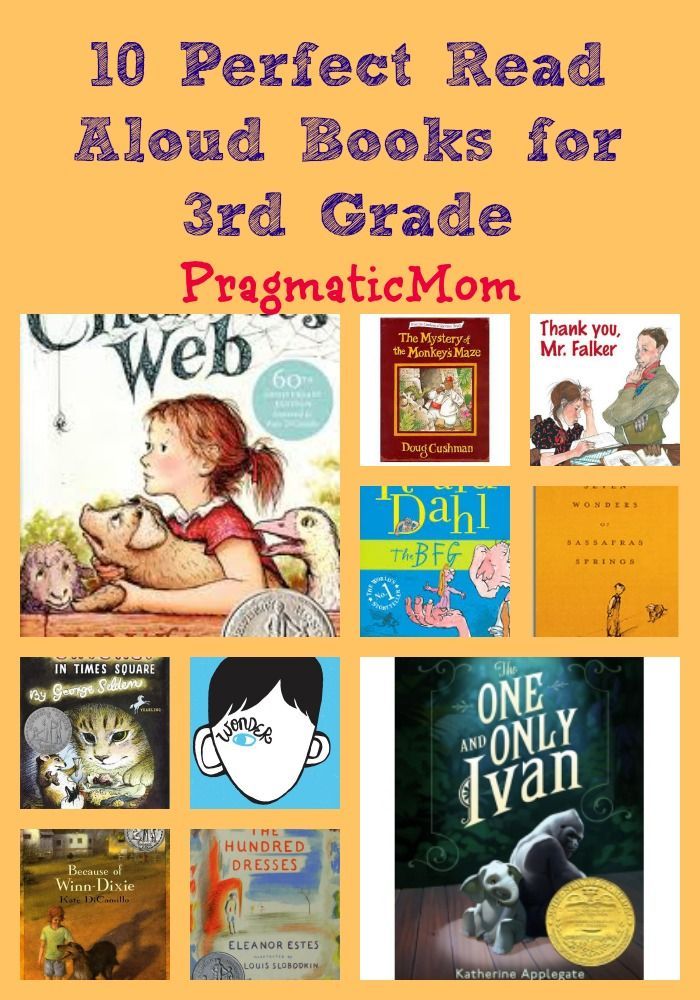

Many of us can remember from our own experience the precious time spent sharing and talking about stories. We remember relating to the friendship between a little girl and a teddy bear named Corduroy in the book of the same name by Don Freeman. We also related to the friendship between a spider and her pig friend, Wilbur, in E.B. White's Charlotte's Web.

We connected to the characters, their situations, or the settings in which the stories took place. Little did we know that when we were making such connections we were learning to think and act like good readers. Because reading aloud provides children with a model of confident and expert reading, many parents and teachers make it a vital part of their teaching practice.

Helping children understand what they read

This article praises the power of reading aloud and goes a step further to praise the power of thinking out loud while reading to children. It's an easy way to highlight the strategies used by thoughtful readers.

Katherine Paterson, author of Bridge to Terabithia, once told a seventh-grader, "A book is a cooperative venture. The writer can write a story down, but the book will never be complete until a reader, of whatever age, takes that book and brings to it his own story." Developing into this kind of reader requires children to become conscious of the multiple comprehension strategies that allow them to deeply understand and engage with the material.

This article focuses on three specific comprehension strategies:

- Connecting books to children's own life experience

- Connecting the books children are reading to other literature they have read

- Connecting what children are reading to universal concepts

The first three sections of this article present current research and practices related to reading aloud. The last section shows how to apply this research to your work with children. We will discuss the important benefits of reading aloud; how to choose good books to read aloud; how to model or teach comprehension strategies as you read aloud; and examples of how to use these comprehension strategies with two sets of books.

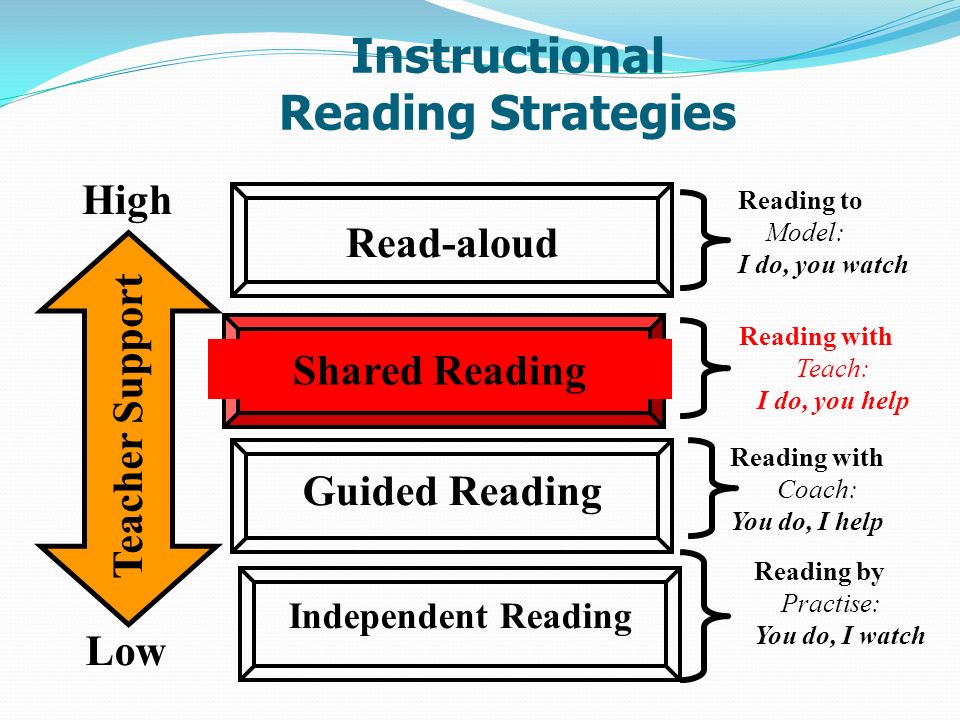

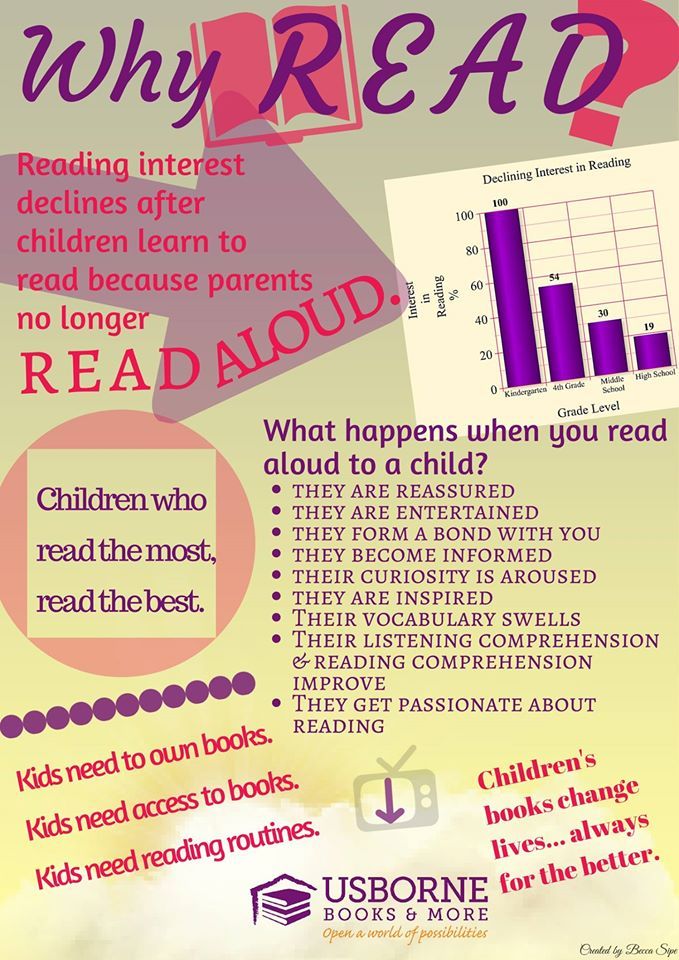

The benefits of reading aloud

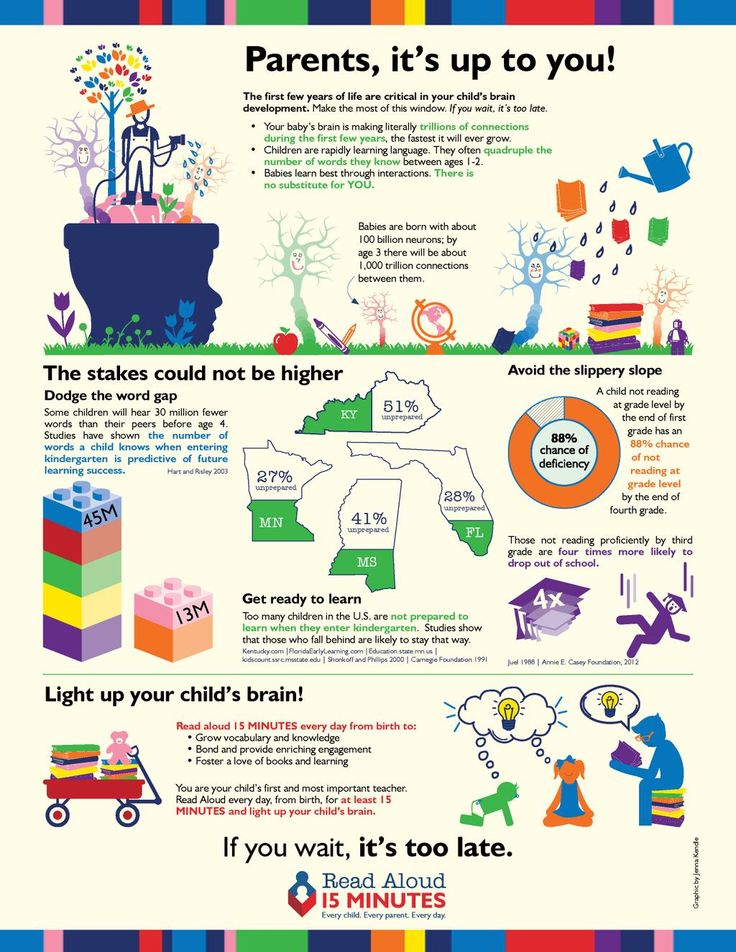

Reading aloud is the foundation for literacy development. It is the single most important activity for reading success (Bredekamp, Copple, & Neuman, 2000). It provides children with a demonstration of phrased, fluent reading (Fountas & Pinnell, 1996). It reveals the rewards of reading, and develops the listener's interest in books and desire to be a reader (Mooney, 1990).

Listening to others read develops key understanding and skills, such as an appreciation for how a story is written and familiarity with book conventions, such as "once upon a time" and "happily ever after" (Bredekamp et al., 2000). Reading aloud demonstrates the relationship between the printed word and meaning – children understand that print tells a story or conveys information – and invites the listener into a conversation with the author.

Children can listen on a higher language level than they can read, so reading aloud makes complex ideas more accessible and exposes children to vocabulary and language patterns that are not part of everyday speech. This, in turn, helps them understand the structure of books when they read independently (Fountas & Pinnell, 1996). It exposes less able readers to the same rich and engaging books that fluent readers read on their own, and entices them to become better readers. Students of any age benefit from hearing an experienced reading of a wonderful book.

This, in turn, helps them understand the structure of books when they read independently (Fountas & Pinnell, 1996). It exposes less able readers to the same rich and engaging books that fluent readers read on their own, and entices them to become better readers. Students of any age benefit from hearing an experienced reading of a wonderful book.

Choosing good books

Children need to be exposed to a wide range of stories and books. They need to see themselves as well as other people, cultures, communities, and issues in the books we read to them. They need to see how characters in books handle the same fears, interests, and concerns that they experience (Barton & Booth, 1990). Selecting a wide range of culturally diverse books will help all children find and make connections to their own life experiences, other books they have read, and universal concepts. (Dyson & Genishi, 1994).

Children use real life to help them understand books, and books help children understand real life. Choose books that invite children to respond with enthusiasm and understanding. Look for books with rich language, meaningful plots, compelling characters, and engaging illustrations (Gambrell & Almasi, 1996).

Choose books that invite children to respond with enthusiasm and understanding. Look for books with rich language, meaningful plots, compelling characters, and engaging illustrations (Gambrell & Almasi, 1996).

Keep two simple questions in mind: Is it a good story? Is it worth sharing with my student? Other ideas to consider when selecting good books include:

- Is the book worthy of a reader's and listener's time?

- Does the story sound good to the ear when read aloud?

- Will it appeal to your audience?

- Will children find the book relevant to their lives and culture?

- Will the book spark conversation?

- Will the book motivate deeper topical understanding?

- Does the book inspire children to find or listen to another book on the same topic? By the same author? Written in the same genre?

- Is the story memorable?

- Will children want to hear the story again?

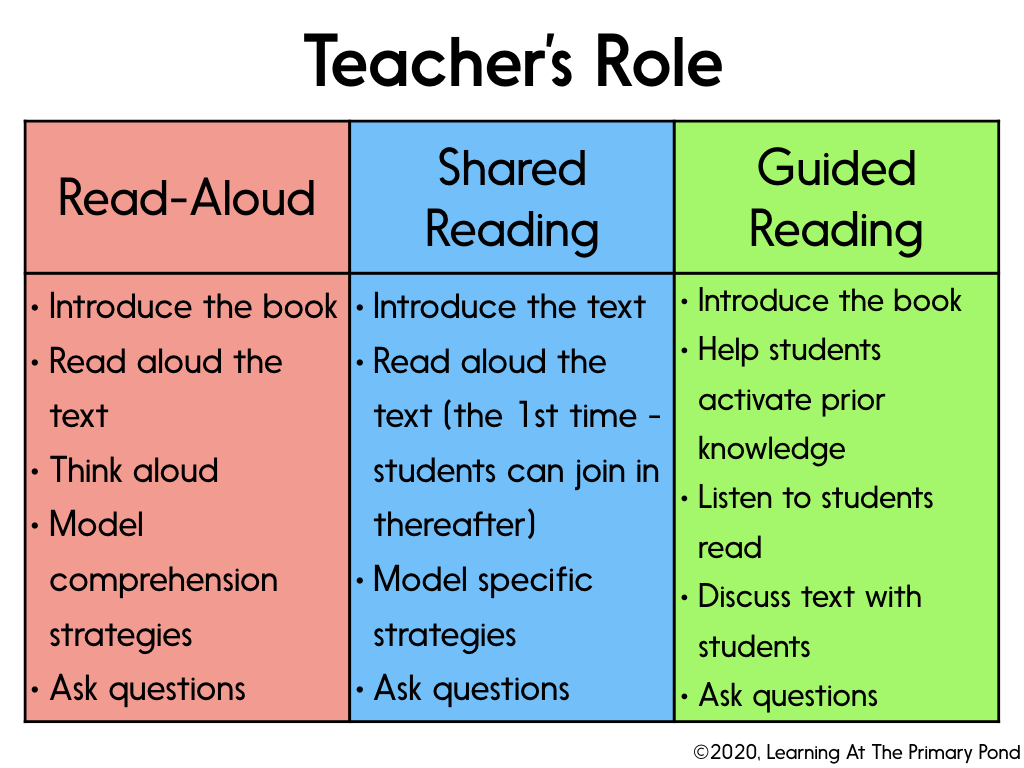

"Think aloud" to model how to make connections

By modeling how fluent readers think about the text and problem solve as they read, we make the invisible act of reading visible. Modeling encourages children to develop the "habits of mind" proficient readers employ.

Modeling encourages children to develop the "habits of mind" proficient readers employ.

Helping children find and make connections to stories and books requires them to relate the unfamiliar text to their relevant prior knowledge. There are several comprehension strategies that help children become knowledgeable readers. Three are:

- Connecting the book to their own life experience

- Connecting the book to other literature they have read

- Connecting what they are reading to universal concepts

- (Keene & Zimmermann, 1997)

Helping children discover these connections requires planning and modeling. Parents and teachers can encourage and support thinking, listening, and discussion, and model "think-alouds," which reveal the inner conversation readers have with the text as they read (Harvey & Goudvis, 2000). Parents and teachers can point out connections between prior experiences and the story, similarities between books, and any relationship between the books and a larger concept.

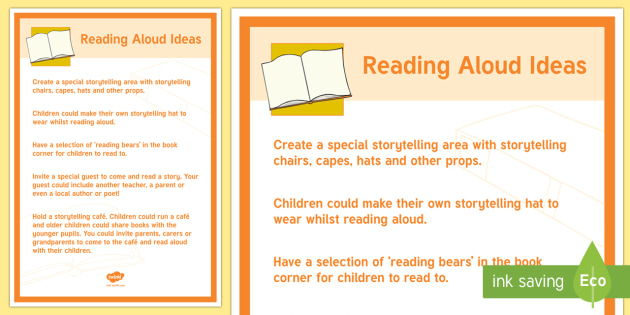

Here are some examples of "think-alouds":

- To make connections between the book and your own life, think aloud as you share. When you read the beginning of A River Dream by Allen Say, for example, you can comment, "This book reminds me of the time my father took me fishing. Have you ever been fishing?"

- To make connections between related books with the same author or similar settings, characters, and concepts, say "Mufaro's Beautiful Daughters by John Steptoe is an African tale that is similar to the tale of Cinderella. Both stories are about sisters – one kind and the other spiteful. Do you know any stories about nice and mean sisters or brothers? Let's continue reading to find out other ways the stories are similar."

- To connect a book to a larger world or universal concept, you could say to your student, "Stellaluna by Janell Cannon helps me understand that we are all the same in many ways, but it's our differences that make us special.

"

"

While fluent readers make these types of connections with ease, many readers do not. Children need to be shown this type of thinking and then asked to join in and participate in book conversations. This active involvement gives you, the teacher, a glimpse into each reader's thinking.

Putting it all together

We found that many children's books are based on classic or universal concepts that come up again and again: understanding ourselves, exploring relationships with families and friends, and investigating other communities, people, and ideas. These concepts help children better understand the social fabric that makes up our world.

One way to begin training parents in how to use "think alouds" is to bring a selection of books with a universal theme, like friendship or family traditions, and have parents read them aloud to one another. Prompt parents to think about the comprehension strategies they are using and to make the same connections they want children to make.

The following are two collections of books that lend themselves especially well to "think alouds."

Read aloud collection 1: We can be anything we want to be

This sample set of books communicates the idea that we can be anything we want. As children develop their sense of self, they often doubt their own abilities. These stories allow children to share such doubts and they model how children can reach their goals.

- Concept: We can be anything we want to be.

- Anchor book: Amazing Grace by Mary Hoffman

- Companion book: The Wednesday Surprise by Eve Bunting

- Companion book: City Green by DyAnne DiSalvo-Ryan

- Age range: All

Amazing Grace opens the conversation. Begin by asking an open-ended question to help the listener make a connection between the book and his or her own life experience. For example, "Grace loves to pretend to be characters from stories. When you pretend, who do you like to be?"

When you pretend, who do you like to be?"

The story then reveals that Grace wants to play Peter in her class's production of Peter Pan, but the other kids tell her she cannot – Peter's neither African American nor a girl. Model thinking out loud with a connection such as, "This reminds me of the time I was told I couldn't play soccer because I couldn't run fast enough." This helps draw the listener into the connection.

Ask the listener to share his own experiences, and to predict what Grace might do next. Like many children, Grace turns to her family. Nana, Grace's grandmother, takes her to see an African American ballerina performing Juliet from Romeo and Juliet. While this reference may be lost on some children, they will relate to the line from the story, "I can be anything I want?"

Children will be eager to predict the ending of the story – at the tryouts for the play, the class agrees that Grace is best – and will relate to the last line of the book, "If Grace put her mind to it, she can do anything she wants. "

"

In The Wednesday Surprise, Anna and Grandma work every Wednesday night on a surprise for Dad's birthday. At the beginning of the story, ask your student to talk about hir or her experiences of attending surprise parties, being watched by a babysitter, having a grandparent who lives nearby, or simply reading books with someone – including with you.

As the story continues, model book-to-book connections. For example, "This story is about the relationship between a grandmother and her granddaughter. There were also a grandmother and granddaughter in Amazing Grace. Do you think these two stories will be alike? Let's keep reading to find out."

Encourage your student to think about what reading every Wednesday night might have to do with the surprise. The story reveals that Anna is teaching her grandmother how to read. Although Dad thinks he has received all his presents, Grandma gives him the best one of all – she reads aloud the stories that Anna has taught her.

Draw out the book-to-book connection: "When I read that Anna's grandmother wanted to be a reader, I think that the story is about how we can be anything we want to be. This reminds me of the story, Amazing Grace. Grace also believed she could be anything she wanted to be. Also, like that story, this one shows the relationship between a grandmother and a grandchild." Then follow i[ with an open-ended question to your student, "How is Anna's relationship with her grandmother different than Grace's?"

City Green is the last book in this set. Like the others, it is well written and supports the universal concept of self-determination.

When a young girl and her elderly friend create a community garden, an empty lot in an urban neighborhood is transformed into a wonderful place filled with flowers and vegetables. While many children may not have had experiences with community gardens, they may connect to the city scene and the idea of wanting the place you live to be beautiful.

By this time, your student might be eager to share her thoughts on book-to-book connections. All three stories depict a grandparent figure and a young girl. All three show how the two work together to get something done. In both Amazing Grace and City Green, the characters did not believe in something, but had a change of heart.

Connections between books and universal concepts are made during the reading of each story, and deepen after the last story. You might model how all three stories support the idea that we can be anything we want. "Grace wanted to be Peter Pan. Anna's grandmother wanted to be a reader. What did Marcy want to be in City Green? What would you like to be? Who will help you become what you want to be?"

Read aloud collection 2: Being a newcomer

This collection allows children to share their own stories of being new to a situation and to gain an awareness of the experiences of other newcomers. In addition, these stories allow you to discuss ideas about diversity and acceptance with your student.

- Concept: Being a newcomer is filled with challenges and memories.

- Anchor book: Painted Words/Spoken Memories by Aliki

- Companion book: Going Home by Eve Bunting

- Companion book: The Memory Coat by Elvira Woodruff

- Companion book: My Freedom Trip by Frances Park and Ginger Park

- Age range: Second grade and up

Painted Words/Spoken Memories is the anchor book for this theme. It is a picture book that shows two aspects of the immigrant experience, both from a child's perspective. The first story, "Painted Words," follows Marianthe or Mari, who is new to the United States, and her mother on the dreaded first day of school.

Some children have personal stories of being new to this country; others have stories of being new to a classroom, school, or neighborhood. These experiences will help relate what you read to the theme. Your conversations with your student may include topics such as moving to a new home, making new friends, or learning a new language.

Your conversations with your student may include topics such as moving to a new home, making new friends, or learning a new language.

In the "Spoken Memories" section of the book, Mari shares her life story through art. Encourage your student to share parts of his life story by modeling how to do so. "My mother used to tell me stories about what it was like to leave her home in Jamaica. Has your family always lived in this area or did they move here from some place else?" Try to be sensitive if the child is not comfortable sharing. Your student will see herself as a storyteller and immediately relate to this aspect of the book.

Like "Painted Words", Going Home is about a family leaving one country to live in another. Ask your student to make this connection between the two books. This book also presents the idea that parents may call one place home, and their children, another. When Carlos and his family go to his parents' village for Christmas, he realizes the sacrifices his parents have made so their children may have better lives.

Pause to listen to your student's thoughts about work, family values, and so on. Reread the lines from "Spoken Memories": "People were leaving our poor village. They were going to a new land, hoping for a better life." This line will emphasize the connection between the two books.

Compared to the first two, the remaining books in this collection may be more abstract (for some children). The Memory Coat begins at the turn of the century in the characters' native country and ends in the United States. The character, Grisha, who has lost his parents, will not give up the tattered coat his mother made him before her death.

Unless your student has a personal experience with immigration, it will be the coat that he or she relates to. Your student will likely make a connection between a sentimental or favorite item he or she could not part with and the character's need to hang onto the coat.

My Freedom Trip is the last companion book in this collection. Unlike the other books, the characters in this book do not immigrate to the United States. They flee North Korea for a better life in South Korea.

Unlike the other books, the characters in this book do not immigrate to the United States. They flee North Korea for a better life in South Korea.

Your student may want to compare and contrast this story with the others for a richer understanding. Explore the idea that many people leave their countries or communities for a better life, and a better life does not necessarily have to take place in the United States. You can also ask, "What are the things that make life better?" Through this rich discussion, you can help your student make connections between the books and the main concept of the collection – being a newcomer is filled with challenges and memories.

Final thoughts

Developing comprehension strategies through reading aloud requires planning and setting up an environment of thinking, listening, and discussion. You will soon learn how to follow your student's lead: modeling connections, asking questions, encouraging discussion, and using literature to prompt personal storytelling.

Become comfortable with slight diversions. Through conversations and diversions, children make meaning and share connections that are relevant to them. Reading aloud to children gives them the opportunity to try on the language and experience of others. It helps them make connections with their lives, and informs their view of themselves and others. Thinking aloud helps children learn how to use comprehension strategies that are important when reading independently.

Sample read aloud collections to try

Family traditions (Age range: all)

- Chicken Sunday by Patricia Polacco

- Dumpling Soup by Jama Kim Rattigan

- Owl Moon by Jane Yolen

Friendship (Age range: all)

- Chester's Way by Kevin Henkes

- Henry Hikes to Fitchburg by D. B. Johnson

- Matthew and Tilly by Rebecca C. Jones

- Henry and Amy (Right-Way-Round and Upside-Down by Stephen Michael King

- Ira Sleeps Over by Bernard Waber

Immigration (Age range: second grade and up)

- Painted Words/Spoken Memories by Aliki

- Going Home by Eve Bunting

- How Many Days to America? A Thanksgiving Story by Eve Bunting

- My Freedom Trip by Frances Park and Ginger Park

- The Memory Coat by Elvira Woodruff

The wonders of literacy (Age range: second grade and up)

- More Than Anything Else by Marie Bradby

- Papa's Stories by Dolores Johnson

- Amber on the Mountain by Robert Johnston

- Tomás and the Library Lady by Pat Mora

- Thank You, Mr.

Falker by Patricia Polacco

Falker by Patricia Polacco

Reading aloud guide. A handbook for loving parents, caring grandparents, and intelligent educators

Jim Trelease's Read-Aloud Handbook

edited and revised by Cyndi Giorgis

Translated from English by Marina Aromshtam and Olga Lisenkova

, 1989, 1995, 2001, 2006, 2013

© The James J. Trelease Read-Aloud Royalties Revocable Trust, 2019

© M. Aromshtam, O. Lisenkova, Russian translation, 2021

© Russian edition, design. Azbuka-Atticus Publishing Group LLC, 2021

CoLibri®

* * *

Reading is the heart of education. The acquisition of knowledge in almost any subject is associated with reading. To understand the essence of a mathematical problem, the student must read it. If a child is not able to read a text in a textbook on physics or social studies, how will he answer the questions after the paragraph?

Since reading is the core around which learning is built, we can say that this is the key to longevity. The American non-profit organization RAND at one time investigated the factors that affect life expectancy - racial, gender, geographic, educational, marital status, diet, smoking, and even church attendance. It turned out that the main determining factor is education. Another researcher studied the era of a hundred years ago, when universal compulsory education was introduced in the United States. It turned out that each year of training prolongs a person's life by an average of one and a half years. The same pattern emerged in other countries. And scientists studying Alzheimer's disease have found that reading in childhood and expanding vocabulary can be preventive measures against the devastating effects of this disease. You will find more information about this on the pages of this book.

The American non-profit organization RAND at one time investigated the factors that affect life expectancy - racial, gender, geographic, educational, marital status, diet, smoking, and even church attendance. It turned out that the main determining factor is education. Another researcher studied the era of a hundred years ago, when universal compulsory education was introduced in the United States. It turned out that each year of training prolongs a person's life by an average of one and a half years. The same pattern emerged in other countries. And scientists studying Alzheimer's disease have found that reading in childhood and expanding vocabulary can be preventive measures against the devastating effects of this disease. You will find more information about this on the pages of this book.

Summarizing all of the above, it can be argued that it is reading (and not watching videos or exchanging text messages) that is the most significant factor in social life. The formula that I give here may seem too simple, but its every statement is substantiated and documented.

Jim Treleese

Reading aloud is a joyful experience for both child and parent. Trelease's book offers helpful clues as to why this experience is so pleasurable for both parties, and how to achieve this effect.

Arthur Schlesinger, historian, writer, politician

This classic guide to reading aloud, updated and expanded, is a real source of inspiration for parents, teachers and anyone who loves children and cares about their future.

The Denver Post

The most important thing we as parents can do for our children is to read to them as often as possible from early childhood. Reading is the road to success in school and in life. If a child learns to love books, he will love to learn.

Laura Bush, Former School Librarian, Former First Lady of the United States

As I read this treasure book, I became more and more fascinated by its contents.

.. I give my unqualified recommendation.

"Dear Abby" (Dear Abby), the cult American column of answers to letters from readers

Preface to the Russian edition

What needs to be done to make a book enter the life of a child?

Read aloud to him.

Not that this was an incredible discovery. Many of us have been read as children. Many of us, having become parents and teachers, read to our own children and students. But this was something taken for granted, almost a routine of life for any intelligent family, where, due to unspoken rules and Soviet traditions, a special attitude to books was cultivated.

And suddenly it turned out that reading aloud is not just a way to spend time with a child: it is a powerful tool of socio-pedagogical influence with far-reaching consequences. It is a way to transform social reality.

A new understanding of reading aloud emerged in the 1980s with the book The Reading Aloud Guide by American author Jim Treleese. I should probably call him "Educator" with a capital P, even though Treleese had no teaching background and never worked as a teacher. Apparently, he also did not think about an academic career, having graduated from the university with a bachelor's degree. Jim Treleese enjoyed and rather successfully (judging by the awards he received) worked as a journalist and artist for a regional newspaper in Springfield. True, before starting his journalistic career, Jim served in the army as a military analyst.

I should probably call him "Educator" with a capital P, even though Treleese had no teaching background and never worked as a teacher. Apparently, he also did not think about an academic career, having graduated from the university with a bachelor's degree. Jim Treleese enjoyed and rather successfully (judging by the awards he received) worked as a journalist and artist for a regional newspaper in Springfield. True, before starting his journalistic career, Jim served in the army as a military analyst.

Perhaps his background in analytics played an important role when Jim Treleese began to sort out his impressions of communicating with sixth graders, whom he met as a volunteer in extracurricular courses and told about the profession of journalism. It turned out that among children there are readers and those who do not read. For some reason, the existence of non-reading children was a discovery for Jim Trelez and greatly upset him (apparently, the interest of schoolchildren in journalism, combined with an unwillingness to read, looked like a glaring paradox).

And Jim began to THINK about it.

Reading children... Where do they come from? It turned out that for many children who read, school teachers read during the lessons ...

And then he found a study that substantiated the benefits of reading aloud. For people with ideas about the value of critical thinking, the rationale for certain actions is incredibly important. A well-founded judgment is the best argument for promoting an idea into practice. And Jim, using his journalistic skills, recounted his “discovered” research, providing it with comments and examples from his own experience. The result was a small 32-page brochure. In the same 19In 1979, a pamphlet called The Read-Aloud Handbook was published by Weekly Reader Books. But Jim Treleese had to pay for the publication himself.

It turned out that the book is in demand. In 1982, the "Guide" came out, albeit in paperback, but in one of the leading American publishers Penguin Books - and produced the effect of an exploding bomb.

In 1983, the book entered the New York Times bestseller list.

Just think: a book on how and why to read to a child has become a bestseller!

From that moment the triumphal procession of the book around the world began. It was published in English-speaking countries - both in the UK and in Australia. It has been translated into Spanish, Japanese, Korean, Chinese and Indonesian. The book was quoted at every opportunity, and now on the Internet you can stumble upon publications like "20 quotes from the book of Jim Treleese ...", "32 most important quotes from the book of Jim Treleese ...".

The Manual was reprinted seven times, and each new edition was marked "revised": true to himself, Jim Treleese included references to new reading research.

This is not surprising. In the 1980s, 1,200 research projects on the topic of "children's reading" were launched annually in the United States. And in 1985, the Reading Commission was established in America, whose task was to collect material, analyze and develop recommendations for the development of children's reading literacy. The report of the commission, titled "Becoming a Reading Nation," contained important data and no less important conclusions, and Jim Treleese could not help but react to this event: in 1989, the third revised edition of his book was published with references to the results of the commission's work. In the same year, the American International Reading Association included The Handbook in its list of the eight greatest books on education produced in the 80s, and the year before, Jim Treleese was awarded the Jeremiah Ludington, founder of the association, for his outstanding contribution to the field of educational publishing. publishers of educational paperbacks.

The report of the commission, titled "Becoming a Reading Nation," contained important data and no less important conclusions, and Jim Treleese could not help but react to this event: in 1989, the third revised edition of his book was published with references to the results of the commission's work. In the same year, the American International Reading Association included The Handbook in its list of the eight greatest books on education produced in the 80s, and the year before, Jim Treleese was awarded the Jeremiah Ludington, founder of the association, for his outstanding contribution to the field of educational publishing. publishers of educational paperbacks.

The 2006 edition was already a mature, well-structured teaching aid, and included chapters on book start, the stages of reading aloud, and the do's and don'ts of reading to a child. It also included an annotated list of books selected by Jim Treleese for adult and child reading, which Jim himself called "The Book Treasury. "

"

* * *

The name of Jim Treleese and the mention of his book in our country first appeared in 2009, in the abstract collection “Reading from the sight, from the screen and “by ear”: the experience of Russia and other countries” (M.: Russkaya school library association). It was from this collection that Russian-speaking experts learned both about Treleese's book and about the Reading Commission, created in response to the concerns of the American pedagogical community in connection with the reading crisis (at that moment it was associated with the rapid development of television: by the mid-80s in every American the family had an average of three televisions), and that this crisis can be countered with something.

And now, ten years after the first mention, we have the opportunity to get acquainted with the eighth edition of the book, which was published in the USA quite recently - in 2018. True, the eighth edition was prepared for publication not by Jim Treleese himself, but by children's literature specialist and university lecturer Cindy Georgis. Probably, you should not be surprised at this, just look at the date of birth of Jim Treleese - 1941. Apparently, this work is important for him not only and not so much as a text written by himself, but as a conductor of a certain idea: it is necessary to convey to parents and teachers the data of new research in the field of children's reading, it is necessary not to abandon attempts to teach as many people as possible to read aloud, because it can change their lives. And Cindy Georgis shares his ideas about the role of reading aloud in education and is a recognized expert in the field of children's books.

Probably, you should not be surprised at this, just look at the date of birth of Jim Treleese - 1941. Apparently, this work is important for him not only and not so much as a text written by himself, but as a conductor of a certain idea: it is necessary to convey to parents and teachers the data of new research in the field of children's reading, it is necessary not to abandon attempts to teach as many people as possible to read aloud, because it can change their lives. And Cindy Georgis shares his ideas about the role of reading aloud in education and is a recognized expert in the field of children's books.

But, for all the relevance of the topic and general problems, for all its "practical orientation", translated into Russian "Guide" is not at all a simple and easy book.

First of all, this is explained by American specifics: the author appeals to the experience of American parents and teachers, talks about discussions on the problems of American school education, refers to studies conducted by American scientists, and lists of recommended books include works only by American authors, a significant part which are unknown to us.

But this feature of the book may even arouse more interest in it. On the one hand, it can be read in accordance with the intention of the authors (Jim Treleese and Cindy Georgis) - in order to gain additional arguments in favor of reading aloud, write out certain maxims or practical algorithms, take note of some books (how many , it turns out, translated into Russian!).

And you can consider the "Guide" as a kind of culturological journey: this, then, is how the problems of reading are understood in American society! These are the kinds of discussions that arise there, these are the decisions school principals and individual teachers can make! This is the role libraries play in American cities and towns! And here is an interesting reading-aloud experience in the American army (even more interesting is the practice of reading aloud in British prisons - a rare case when Cindy Georgis refers to a non-American experience).

All this is incredibly interesting material for analysis. For example, for the authors of this book, there is an obvious relationship between a child's reading level and the social status of the family in which he grows up. And the degree of development of reading skills largely determines the child's ability to learn, his ability to move from one educational level to another, get a "good education" and, as a result, take a place in society that allows him to "earn good money." There is a direct and irrevocable connection here: education in the United States plays the role of a social elevator. So by helping children learn to read (and reading aloud is seen as one of the most important ways to encourage independent reading), American educators and librarians are helping them rise to a new level of social well-being. And reading aloud becomes almost the main way to fight ... against poverty!

For example, for the authors of this book, there is an obvious relationship between a child's reading level and the social status of the family in which he grows up. And the degree of development of reading skills largely determines the child's ability to learn, his ability to move from one educational level to another, get a "good education" and, as a result, take a place in society that allows him to "earn good money." There is a direct and irrevocable connection here: education in the United States plays the role of a social elevator. So by helping children learn to read (and reading aloud is seen as one of the most important ways to encourage independent reading), American educators and librarians are helping them rise to a new level of social well-being. And reading aloud becomes almost the main way to fight ... against poverty!

Such a "social" turn of the topic is completely unexpected for the Russian reader. When we talk about reading aloud, we think of anything but fighting poverty. Our reading is loaded with a completely different meaning.

Our reading is loaded with a completely different meaning.

Yes, indeed, in every intelligent Soviet family, books were cultivated and read aloud to children. But, we will notice, only to small children. And only until the time when they learned to read on their own. The true value was not at all shared experiences when reading aloud, but reading to oneself, because with it a person acquired an additional degree of freedom - not external, but internal. I don’t know if the image of a child who has covered himself with a blanket and in the darkness of this cozy cave, illuminating the pages of a book with a flashlight, will say anything to an American teacher. Perhaps such a "niche of peace", such a secret individual space is characteristic only of the child of the Soviet era. And with such a reading experience, some sort of “History without an End” by Michael Ende, where reading was seen as an escape from reality, fit in perfectly. And the statuses of "a person who reads" and "a person who is socially prosperous" in our country were not directly connected and still are not connected.

Perhaps that is why Jim Treleese's book came to us so late - about ten years later than the idea itself. And the idea took root, because in the late 90s in our country they suddenly started talking about the crisis of reading: they say, what is it? Kids today don't read at all! What to do?

Unlike the Americans with their 1,200 reading research projects a year, our public anxiety was only confirmed by the sharp drop in library attendance at the start of the 2000s. But these "data" were opposed by others - related to the intensively developing book market and the ability to freely purchase books for personal use, which was so difficult under Soviet rule.

And what we called the “children’s reading crisis”, in my opinion, was due to a much more serious phenomenon: we suddenly felt a cultural gap between people of the “Soviet mix” (or “anti-Soviet”, in this context there is not much difference between them ) and "new" children. It turned out that the “new” children (just like the Americans) do not at all strive, armed with a flashlight, to hide with a book in a “cave” from a blanket. And, what is especially unpleasant, they have little interest in the books that we read in childhood. They generally have a completely different attitude to information and education. And their ideas about the "niche of peace" are completely different.

And, what is especially unpleasant, they have little interest in the books that we read in childhood. They generally have a completely different attitude to information and education. And their ideas about the "niche of peace" are completely different.

So reading aloud was almost the only way for us to bridge the resulting cultural gap. If you want, the opportunity to preserve with children (and grandchildren) a common cultural identity. What we can read to them will become part of their cultural baggage, and will unite us with them.

In the wake of such aspirations in the early 2000s, we really liked the book of the French writer Daniel Pennack "Like a Novel" - a personal experience of dealing with non-reading teenagers and the opportunity to turn the tide through reading aloud. We hoped that such an approach would, among other things, teach us to accept children as they "turned out." But Pennack's provocative and harsh thesis - "The child has the right not to read" - plunged us into despondency, despite all the efforts we made to come to terms with it.

I think that for both Jim Treleese and Cindy Georgis such a statement would be completely unacceptable. It's like saying, "A child has the right to live in poverty" or even "A child has the right to go to jail." You demand from the child that he clean the room or wash before bed, even if he does not want to do it, writes Cindy Georgis. And the habit of reading is no less important for life than the habit of personal hygiene.

Something tells me that such a position is more acceptable to Russian readers.

In other words, the book by Jim Treleese and Cindy Georgis gives a serious impetus to reflection - just as its appearance at one time became the starting point for an entire international movement, which, however, did not affect European countries and the countries of the former USSR. Only the Poles fell under the influence of this book. It was not translated into Polish - apparently it was read in English - but in 2001 Poland launched the national campaign "All Poles Read to Children". By 2007, 87% of the country's population knew about it, and 37% of parents claimed to read to their children. True, it was about children of preschool age. Also a lot.

By 2007, 87% of the country's population knew about it, and 37% of parents claimed to read to their children. True, it was about children of preschool age. Also a lot.

In fact, the most important thing is to give the child the right cultural start. And the "Guide", without any doubt, has a great power of persuasion. I would even say that after reading the book, you understand that the ideas presented in it have simply eaten into your brain. This is how they are presented there: they convince you, and they speak, and they set you up, and they call you to action. And you naively thought that even without any "Guidelines" you are adept at reading aloud...

So reading this book is also an interesting experiment set on yourself and helping you move to a new level of progressive parenthood.

Marina Aromshtam,writer, teacher, translator, creator of the website www.papmambook.ru for those who read to children published in Russian are marked in the text with a special sign ★.

Cindy Georgis reads aloud to second graders during Dr. Seuss' Birthday General Reading Day (March 2)

The 8th edition of the Reading Aloud Guide is dedicated to two Jims:

to Jim Treleese for his passion for reading aloud and for his educational work in this area. Jim, I am forever indebted to you for allowing me to share this incredible legacy with you.

to Jim Kruger for love and endless support over the years. You are the best science assistant in the world. I am grateful to you for reading and rereading this work, for your advice and editing of the new edition. You and I are a great team!

Cindy GeorgisIt is important that your baby's first encounters with a book bring him pleasure. Only then will the child want to repeat this experience - both in the near future and in the future. Our main goal is to grow a lifelong reader

Acknowledgments Cindy Georgis

When you have the opportunity to rewrite one of the most famous and authoritative books on reading aloud, nothing is more important than the support of loved ones, colleagues, teachers, children, librarians and editors.

I would like to express my deep gratitude:

to my parents, Donna Zanetti and Glenn Martens. If only they had lived to see me rise to this incredible new level of professional development! My parents did not have a higher education, but they managed to instill a love of reading in me and my sister Glenda. As a child, my mother read books to us, and my father read magazines and the daily press, involving us in a discussion of a variety of issues. They did exactly what needs to be done and what I talk about in this book;

- to my past and present students. They let me know time and time again that reading aloud together brings people together. I read books to six-year-olds, nineteen-year-old boys and girls, and people over the age of forty. The applause that bursts out of your listeners after reading the picture book is amazing;

to my friends, old and new, who shared their reading stories with me. I want to give special thanks to Melissa Olans Antinoff, Kathleen Armstrong, Jim Bailey, Diane Crawford, Matt de la Peña, Charity Delach, Peter Delach, Christine Draper, Sean Dudley, Alma S.

Baca Hernandez, Clara Lackey, Mark Lackey, Erica and Richard McCallum , Tiffany Nay, Elisha O'Brien, Jasmine E. Rich-Arnold, Scott Riley, Maria Rue, Jessica Saad, Francisco Sanchez, Megan Sloane and Jimma Teidlek;

to my wonderful friends and colleagues Nancy Johnson and Marie LeJeune, not only for their stories, but also for understanding the importance of the work I undertook. I cannot express how much I value our friendship;

to children's book publishers and marketers: Laurie Benton, Terry Borzumato-Greenberg, Lucy Del Priore, Lisa DiSarro, Cathy Halata, Emily Huddleson, Angus Killick, Neil Porter, Lisette Serrano, Dina Sherman, Victoria Stapleton and Jaime Wong. You were ready at any moment to give me friendly support and offer the books I needed for the work;

, to children's writers Rosemary Wells and Kate DiCamillo, longtime readers of reading aloud. Rosemary wrote the book Read to Your Bunny and launched a campaign of the same name to encourage parents to read aloud to their children for 20 minutes each day.

And Kate is not only a wonderful writer and storyteller, but also a National Ambassador for Children's Literature. She never ceases to remind that reading aloud can change someone's life, and her voice is heard by children, parents, educators and librarians around the world;

to my editors Catherine Court and Victoria Sevan. From the moment we first met, I knew that you, like me, love this book with all your heart and would like parents, teachers, librarians, all members of the community to once again take it in their hands and experience its beneficial effects.

Last but not least, I would like to thank my husband Jim Krueger. Thank you for making your own meals and taking the dogs out for walks without me countless times. Thank you for letting me read sentences, phrases and paragraphs aloud to you to check how they sound.

Meetings on Wednesdays, or Aunt Gulda says "Let's run!"

I must say right away, so that there are no questions later: I do not recommend this book for independent reading to children! We read each chapter aloud, discuss it, and believe me, there is something to discuss there…

Let's go!

Well.

I was completely unprepared for this book.

In places when reading, even my hair stands on end, although I consider myself a fairly progressive person😀. I took a photo of the pages that triggered me so well. To see what style is in the book, just read the highlighted fragments of these spreads.

I promise you the first reaction to some parts of the work from shame to amazement and thoughts, why write about this to children at all.

Although I confess that my daughter and I pretty much laughed while reading, what can we hide.

Sometimes the author walks completely on the edge, but never stumbles! This is a masterpiece:

Let me explain why I still recommend getting to know this book better, taking a closer look.

First . My gaze, sometimes blinkered by Soviet childhood, did not allow me to immediately accept the book as kind, sincere, tender. All my insides opposed this work, the book seemed ambiguous, controversial, too lax or something.

But if you, like me, allow yourself to abandon the imposed stereotypes, you will feel the depth of this amazing book about a girl and an aunt, about true kindness and selflessness.

Second . Aunt Gulda is bright, unthinkably friendly, fantastically kind, a person with special needs... The girl is the main character of the book, she forms an attitude towards herself and others, of course mom and dad behave so-so, but in all honesty, many of their phrases are heard all around... Girl Sarah sees much more than adults, and one can still argue which of the characters in the book is "normal" in fact. After reading, I am sure that you will want to reconsider your relationship with your environment, with your children.

Third . Think! This book will really make you think! Yes, it is not only about the good and the eternal, but there is also about dirt around, and about misunderstanding, about the cry of the soul and suffering ... Here I will repeat for the hundredth time that books, like cinema, come in different genres, not only about good deeds, love and princes with a horse to boot.