Tips on teaching your child to read

9 Fun and Easy Tips

With the abundance of information out there, it can seem like there is no clear answer about how to teach a child to read. As a busy parent, you may not have time to wade through all of the conflicting opinions.

That’s why we’re here to help! There are some key elements when it comes to teaching kids to read, so we’ve rounded up nine effective tips to help you boost your child’s reading skills and confidence.

These tips are simple, fit into your lifestyle, and help build foundational reading skills while having fun!

Tips For How To Teach A Child To Read

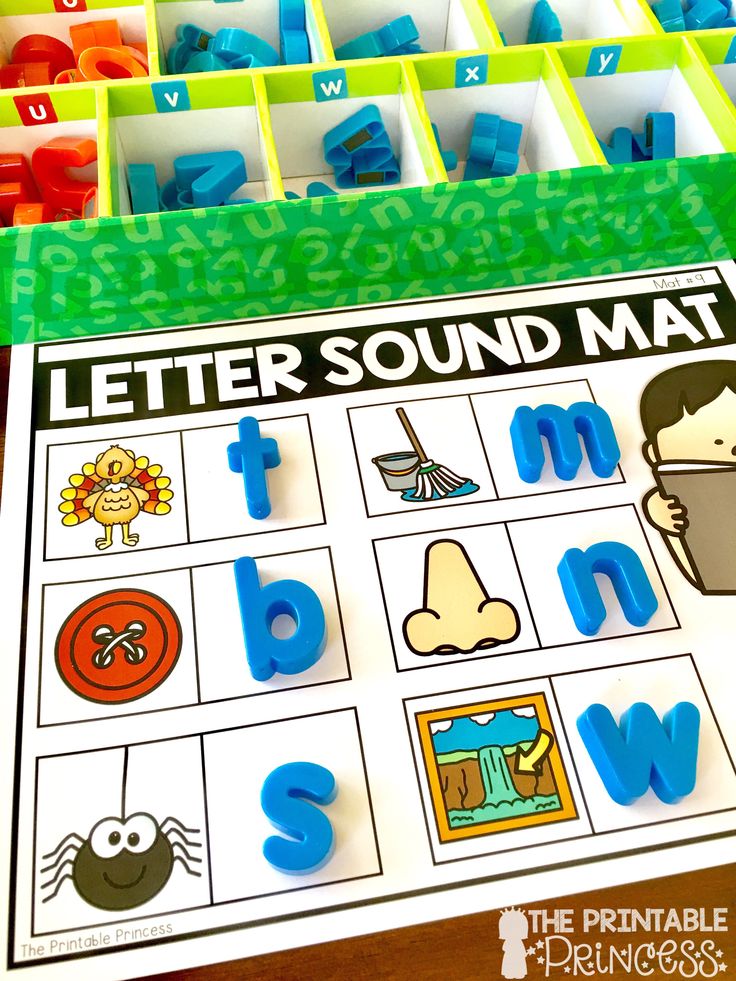

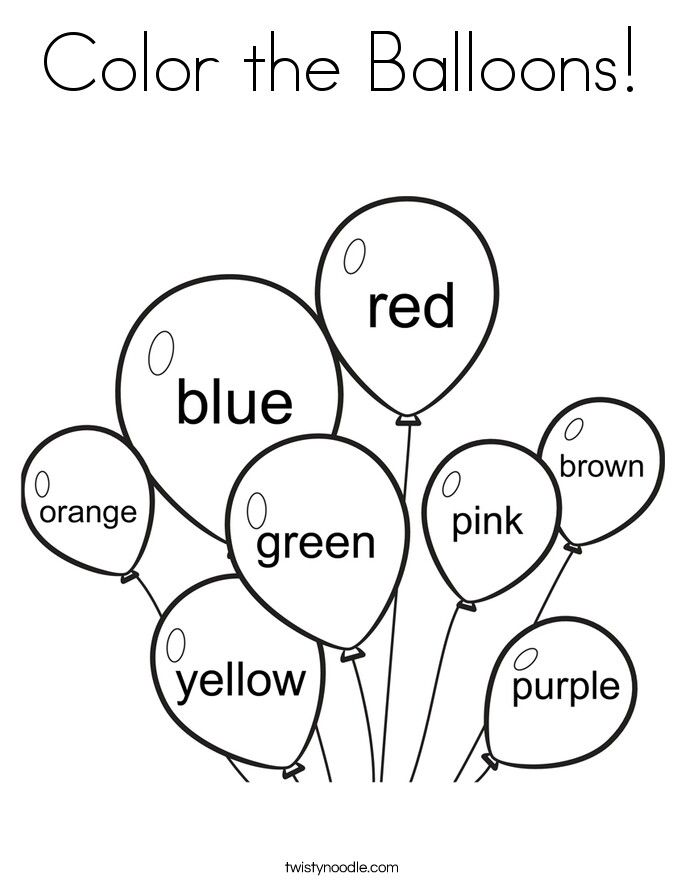

1) Focus On Letter Sounds Over Letter Names

We used to learn that “b” stands for “ball.” But when you say the word ball, it sounds different than saying the letter B on its own. That can be a strange concept for a young child to wrap their head around!

Instead of focusing on letter names, we recommend teaching them the sounds associated with each letter of the alphabet. For example, you could explain that B makes the /b/ sound (pronounced just like it sounds when you say the word ball aloud).

Once they firmly establish a link between a handful of letters and their sounds, children can begin to sound out short words. Knowing the sounds for B, T, and A allows a child to sound out both bat and tab.

As the number of links between letters and sounds grows, so will the number of words your child can sound out!

Now, does this mean that if your child already began learning by matching formal alphabet letter names with words, they won’t learn to match sounds and letters or learn how to read? Of course not!

We simply recommend this process as a learning method that can help some kids with the jump from letter sounds to words.

2) Begin With Uppercase Letters

Practicing how to make letters is way easier when they all look unique! This is why we teach uppercase letters to children who aren’t in formal schooling yet.

Even though lowercase letters are the most common format for letters (if you open a book at any page, the majority of the letters will be lowercase), uppercase letters are easier to distinguish from one another and, therefore, easier to identify.

Think about it –– “b” and “d” look an awful lot alike! But “B” and “D” are much easier to distinguish. Starting with uppercase letters, then, will help your child to grasp the basics of letter identification and, subsequently, reading.

To help your child learn uppercase letters, we find that engaging their sense of physical touch can be especially useful. If you want to try this, you might consider buying textured paper, like sandpaper, and cutting out the shapes of uppercase letters.

Ask your child to put their hands behind their back, and then place the letter in their hands. They can use their sense of touch to guess what letter they’re holding! You can play the same game with magnetic letters.

3) Incorporate Phonics

Research has demonstrated that kids with a strong background in phonics (the relationship between sounds and symbols) tend to become stronger readers in the long-run.

A phonetic approach to reading shows a child how to go letter by letter — sound by sound — blending the sounds as you go in order to read words that the child (or adult) has not yet memorized.

Once kids develop a level of automatization, they can sound out words almost instantly and only need to employ decoding with longer words. Phonics is best taught explicitly, sequentially, and systematically — which is the method HOMER uses.

If you’re looking for support helping your child learn phonics, our HOMER Learn & Grow app might be exactly what you need! With a proven reading pathway for your child, HOMER makes learning fun!

4) Balance Phonics And Sight Words

Sight words are also an important part of teaching your child how to read. These are common words that are usually not spelled the way they sound and can’t be decoded (sounded out).

Because we don’t want to undo the work your child has done to learn phonics, sight words should be memorized. But keep in mind that learning sight words can be challenging for many young children.

So, if you want to give your child a good start on their reading journey, it’s best to spend the majority of your time developing and reinforcing the information and skills needed to sound out words.

5) Talk A Lot

Even though talking is usually thought of as a speech-only skill, that’s not true. Your child is like a sponge. They’re absorbing everything, all the time, including the words you say (and the ones you wish they hadn’t heard)!

Talking with your child frequently and engaging their listening and storytelling skills can increase their vocabulary.

It can also help them form sentences, become familiar with new words and how they are used, as well as learn how to use context clues when someone is speaking about something they may not know a lot about.

All of these skills are extremely helpful for your child on their reading journey, and talking gives you both an opportunity to share and create moments you’ll treasure forever!

6) Keep It Light

Reading is about having fun and exploring the world (real and imaginary) through text, pictures, and illustrations. When it comes to reading, it’s better for your child to be relaxed and focused on what they’re learning than squeezing in a stressful session after a long day.

We’re about halfway through the list and want to give a gentle reminder that your child shouldn’t feel any pressure when it comes to reading — and neither should you!

Although consistency is always helpful, we recommend focusing on quality over quantity. Fifteen minutes might sound like a short amount of time, but studies have shown that 15 minutes a day of HOMER’s reading pathway can increase early reading scores by 74%!

It may also take some time to find out exactly what will keep your child interested and engaged in learning. That’s OK! If it’s not fun, lighthearted, and enjoyable for you and your child, then shake it off and try something new.

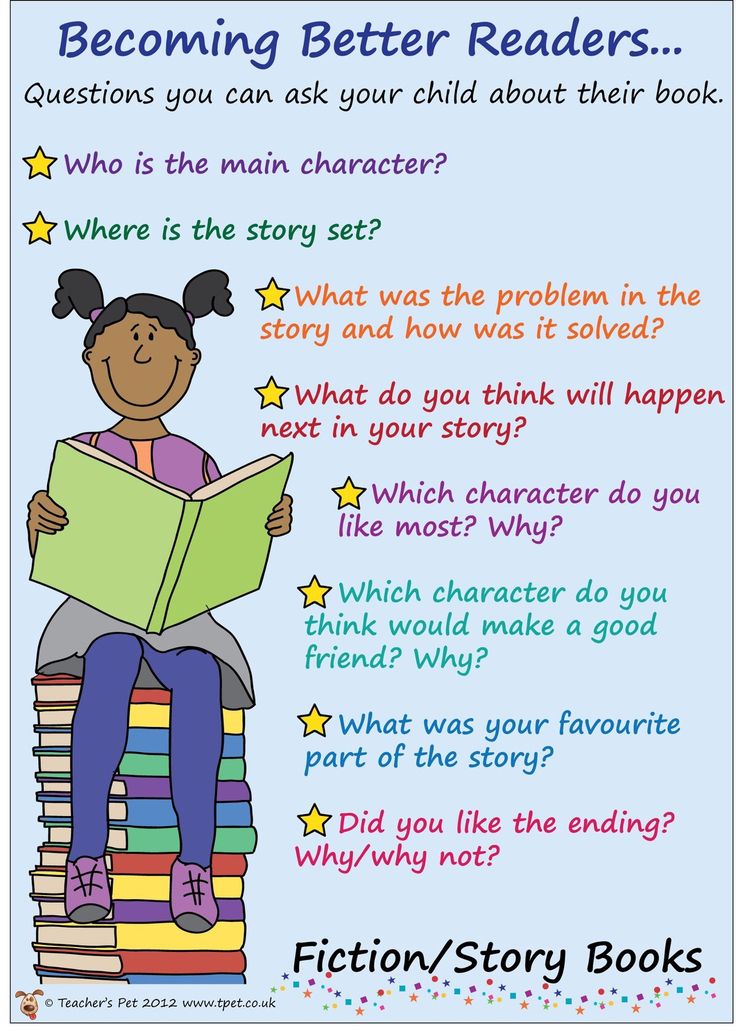

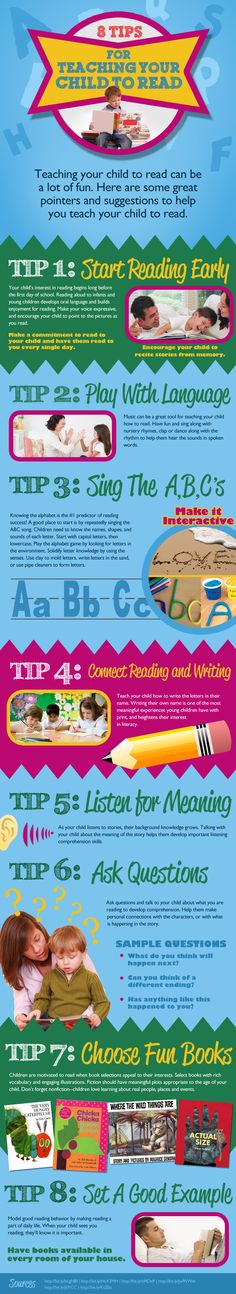

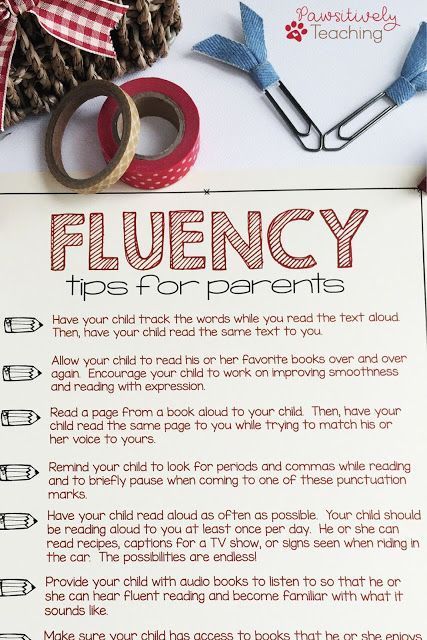

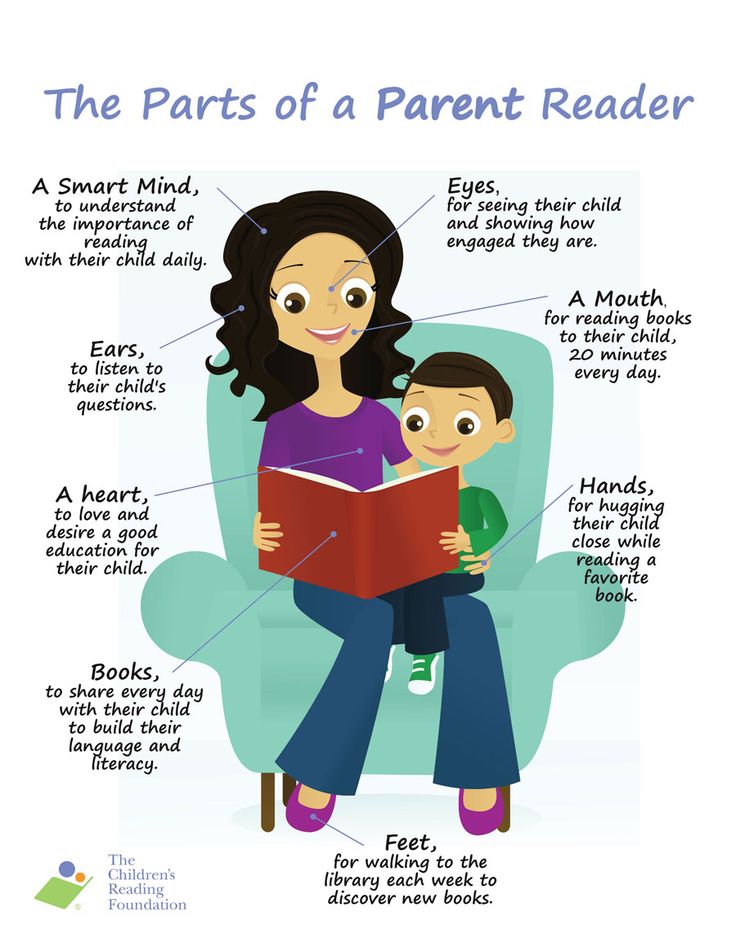

7) Practice Shared Reading

While you read with your child, consider asking them to repeat words or sentences back to you every now and then while you follow along with your finger.

There’s no need to stop your reading time completely if your child struggles with a particular word. An encouraging reminder of what the word means or how it’s pronounced is plenty!

Another option is to split reading aloud time with your child. For emerging readers, you can read one line and then ask them to read the next. For older children, reading one page and letting them read the next page is beneficial.

For emerging readers, you can read one line and then ask them to read the next. For older children, reading one page and letting them read the next page is beneficial.

Doing this helps your child feel capable and confident, which is important for encouraging them to read well and consistently!

This technique also gets your child more acquainted with the natural flow of reading. While they look at the pictures and listen happily to the story, they’ll begin to focus on the words they are reading and engage more with the book in front of them.

Rereading books can also be helpful. It allows children to develop a deeper understanding of the words in a text, make familiar words into “known” words that are then incorporated into their vocabulary, and form a connection with the story.

We wholeheartedly recommend rereading!

8) Play Word Games

Getting your child involved in reading doesn’t have to be about just books. Word games can be a great way to engage your child’s skills without reading a whole story at once.

One of our favorite reading games only requires a stack of Post-It notes and a bunched-up sock. For this activity, write sight words or words your child can sound out onto separate Post-It notes. Then stick the notes to the wall.

Your child can then stand in front of the Post-Its with the bunched-up sock in their hands. You say one of the words and your child throws the sock-ball at the Post-It note that matches!

9) Read With Unconventional Materials

In the same way that word games can help your child learn how to read, so can encouraging your child to read without actually using books!

If you’re interested in doing this, consider using PlayDoh, clay, paint, or indoor-safe sand to form and shape letters or words.

Another option is to fill a large pot with magnetic letters. For emerging learners, suggest that they pull a letter from the pot and try to name the sound it makes. For slightly older learners, see if they can name a word that begins with the same sound, or grab a collection of letters that come together to form a word.

As your child becomes more proficient, you can scale these activities to make them a little more advanced. And remember to have fun with it!

Reading Comes With Time And Practice

Overall, we want to leave you with this: there is no single answer to how to teach a child to read. What works for your neighbor’s child may not work for yours –– and that’s perfectly OK!

Patience, practicing a little every day, and emphasizing activities that let your child enjoy reading are the things we encourage most. Reading is about fun, exploration, and learning!

And if you ever need a bit of support, we’re here for you! At HOMER, we’re your learning partner. Start your child’s reading journey with confidence with our personalized program plus expert tips and learning resources.

Author

Teaching children to read isn’t easy. How do kids actually learn to read?

A student in a Mississippi elementary school reads a book in class. Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger Report

Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger ReportTeaching kids to read isn’t easy; educators often feel strongly about what they think is the “right” way to teach this essential skill. Though teachers’ approaches may differ, the research is pretty clear on how best to help kids learn to read. Here’s what parents should look for in their children’s classroom.

How do kids actually learn how to read?

Research shows kids learn to read when they are able to identify letters or combinations of letters and connect those letters to sounds. There’s more to it, of course, like attaching meaning to words and phrases, but phonemic awareness (understanding sounds in spoken words) and an understanding of phonics (knowing that letters in print correspond to sounds) are the most basic first steps to becoming a reader.

If children can’t master phonics, they are more likely to struggle to read. That’s why researchers say explicit, systematic instruction in phonics is important: Teachers must lead students step by step through a specific sequence of letters and sounds. Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

That’s why researchers say explicit, systematic instruction in phonics is important: Teachers must lead students step by step through a specific sequence of letters and sounds. Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

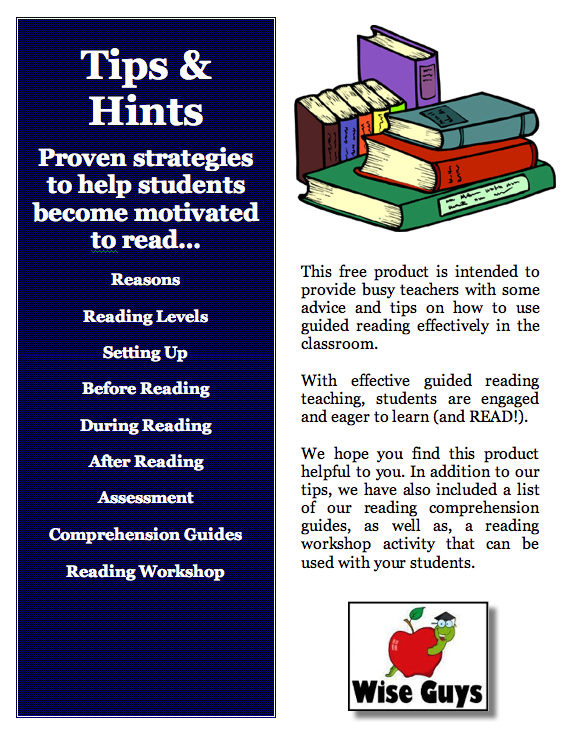

How should your child’s school teach reading?

Timothy Shanahan, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago and an expert on reading instruction, said phonics are important in kindergarten through second grade and phonemic awareness should be explicitly taught in kindergarten and first grade. This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

The wars over how to teach reading are back. Here’s the four things you need to know.

Wiley Blevins, an author and expert on phonics, said a good test parents can use to determine whether a child is receiving research-based reading instruction is to ask their child’s teacher how reading is taught. “They should be able to tell you something more than ‘by reading lots of books’ and ‘developing a love of reading.’ ” Blevins said. Along with time dedicated to teaching phonics, Blevins said children should participate in read-alouds with their teacher to build vocabulary and content knowledge. “These read-alouds must involve interactive conversations to engage students in thinking about the content and using the vocabulary,” he said. “Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

“Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

Rasmussen’s school uses a structured approach: Children receive lessons in phonemic awareness, phonics, pre-writing and writing, vocabulary and repeated readings. Research shows this type of “systematic and intensive” approach in several aspects of literacy can turn children who struggle to read into average or above-average readers.

What should schools avoid when teaching reading?

Educators and experts say kids should be encouraged to sound out words, instead of guessing. “We really want to make sure that no kid is guessing,” Rasmussen said. “You really want … your own kid sounding out words and blending words from the earliest level on.” That means children are not told to guess an unfamiliar word by looking at a picture in the book, for example. As children encounter more challenging texts in later grades, avoiding reliance on visual cues also supports fluent reading. “When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

“When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

Related: Teacher Voice: We need phonics, along with other supports, for reading

Blevins and Shanahan caution against organizing books by different reading levels and keeping students at one level until they read with enough fluency to move up to the next level. Although many people may think keeping students at one level will help prevent them from getting frustrated and discouraged by difficult texts, research shows that students actually learn more when they are challenged by reading materials.

Blevins said reliance on “leveled books” can contribute to “a bad habit in readers.” Because students can’t sound out many of the words, they rely on memorizing repeated words and sentence patterns, or on using picture clues to guess words. Rasmussen said making kids stick with one reading level — and, especially, consistently giving some kids texts that are below grade level, rather than giving them supports to bring them to grade level — can also lead to larger gaps in reading ability.

How do I know if a reading curriculum is effective?

Some reading curricula cover more aspects of literacy than others. While almost all programs have some research-based components, the structure of a program can make a big difference, said Rasmussen. Watching children read is the best way to tell if they are receiving proper instruction — explicit, systematic instruction in phonics to establish a foundation for reading, coupled with the use of grade-level texts, offered to all kids.

Parents who are curious about what’s included in the curriculum in their child’s classroom can find sources online, like a chart included in an article by Readingrockets.org which summarizes the various aspects of literacy, including phonics, writing and comprehension strategies, in some of the most popular reading curricula.

Blevins also suggested some questions parents can ask their child’s teacher:

- What is your phonics scope and sequence?

“If research-based, the curriculum must have a clearly defined phonics scope and sequence that serves as the spine of the instruction. ” Blevins said.

” Blevins said.

- Do you have decodable readers (short books with words composed of the letters and sounds students are learning) to practice phonics?

“If no decodable or phonics readers are used, students are unlikely to get the amount of practice and application to get to mastery so they can then transfer these skills to all reading and writing experiences,” Blevins said. “If teachers say they are using leveled books, ask how many words can students sound out based on the phonics skills (teachers) have taught … Can these words be fully sounded out based on the phonics skills you taught or are children only using pieces of the word? They should be fully sounding out the words — not using just the first or first and last letters and guessing at the rest.”

- What are you doing to build students’ vocabulary and background knowledge? How frequent is this instruction? How much time is spent each day doing this?

“It should be a lot,” Blevins said, “and much of it happens during read-alouds, especially informational texts, and science and social studies lessons. ”

”

- Is the research used to support your reading curriculum just about the actual materials, or does it draw from a larger body of research on how children learn to read? How does it connect to the science of reading?

Teachers should be able to answer these questions, said Blevins.

What should I do if my child isn’t progressing in reading?

When a child isn’t progressing, Blevins said, the key is to find out why. “Is it a learning challenge or is your child a curriculum casualty? This is a tough one.” Blevins suggested that parents of kindergarteners and first graders ask their child’s school to test the child’s phonemic awareness, phonics and fluency.

Parents of older children should ask for a test of vocabulary. “These tests will locate some underlying issues as to why your child is struggling reading and understanding what they read,” Blevins said. “Once underlying issues are found, they can be systematically addressed. ”

”

“We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs. But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York

Rasmussen recommended parents work with their school if they are concerned about their children’s progress. By sitting and reading with their children, parents can see the kind of literacy instruction the kids are receiving. If children are trying to guess based on pictures, parents can talk to teachers about increasing phonics instruction.

“Teachers aren’t there doing necessarily bad things or disadvantaging kids purposefully or willfully,” Rasmussen said. “You have many great reading teachers using some effective strategies and some ineffective strategies.”

What can parents do at home to help their children learn to read?

Parents want to help their kids learn how to read but don’t want to push them to the point where they hate reading. “Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

“Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

- Challenge kids to find everything in the house that starts with a specific sound.

- Stretch out one word in a sentence. Ask your child to “pass the salt” but say the individual sounds in the word “salt” instead of the word itself.

- Ask your child to figure out what every family member’s name would be if it started with a “b” sound.

- Sing that annoying “Banana fana fo fanna song.” Jiban said that kind of playful activity can actually help a kid think about the sounds that correspond with letters even if they’re not looking at a letter right in front of them.

- Read your child’s favorite book over and over again. For books that children know well, Jiban suggests that children use their finger to follow along as each word is read. Parents can do the same, or come up with another strategy to help kids follow which words they’re reading on a page.

Giving a child diverse experiences that seem to have nothing to do with reading can also help a child’s reading ability. By having a variety of experiences, Rasmussen said, children will be able to apply their own knowledge to better comprehend texts about various topics.

This story about teaching children to read was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

How to teach a child to read: advice to parents

Today, a first grader entering school should read well. This is one of the main criteria for preparing for modern schooling. Basically, the task of teaching a child to read falls on the shoulders of the parents. Before teaching a child to read, parents should understand what mental processes help the formation of this skill.

Memory promotes visual memorization and reproduction of the image of letters, letter combinations, syllables and whole words.

Attention, its volume and distribution help the child to keep a certain number of letters, syllables, words in the “field of vision”.

Thinking is responsible for the synthetic-analytical process of reading, stimulates the development of phonemic hearing, which allows you to learn the sound-letter composition of the word. Good pronunciation and a broad outlook also play an important role in the formation of reading skills.

Developing mental functions, parents create a foundation on which it will be easy to learn not only reading, but also writing and counting.

How to teach a child to read at home without the help of preschool teachers?

First, let's make it a rule never to force a child to read. Everything we want to do, we call a game. In the game we learn letters. Letters should be everywhere: cubes, pictures, posters, magnets, etc. Letters can be drawn, cut, glued, made from the constructor. It’s good if a child can touch a letter created with his own hands from different materials: fabric of various textures, millet, plasticine, etc. Fingertips also "remember" the letter.

Fingertips also "remember" the letter.

How to teach a child to read by syllables?

This is the next step in learning to read at home. Do not confuse the child by explaining to him that: "VE and A are BA." How many "extra" sounds are there in this phrase? It is better to purchase a syllabary table or make cards with syllables yourself. We play again, memorizing a whole syllable at once: Wa, Ri, Su. The child visually perceives the whole image of the syllable at once. At the same time, we develop phonemic awareness. It is important for a child to learn to isolate words from speech, sounds and syllables from words. You can also play with sounds: a) find around the words with the sound "p"; b) guess the word in which the first sound is “t”; c) in which word the sound "a" is hidden. These and similar games will not only teach the child to be attentive to the word, but will also become a great helper when you need to keep the child busy with something. The next game can be a bridge in learning to read. Guess which word is meant. An adult calls the word by sounds: K-O-T, and the child pronounces the whole word. First we make small words, then more authentic. It is already possible to take books. Consider carefully the page, name the familiar letters, syllables. We are trying to name fusion syllables, stretching out a consonant sound: v-v-v-a. But syllabic reading has been mastered.

The next game can be a bridge in learning to read. Guess which word is meant. An adult calls the word by sounds: K-O-T, and the child pronounces the whole word. First we make small words, then more authentic. It is already possible to take books. Consider carefully the page, name the familiar letters, syllables. We are trying to name fusion syllables, stretching out a consonant sound: v-v-v-a. But syllabic reading has been mastered.

How to teach a child to read fluently?

Let's work on the pronunciation first. Any poem that a child knows by heart can be turned into a game. We will tell the poem quietly, loudly, smoothly, as we sing a song, like a bird market. Such speech exercises help develop articulation. When a child begins to read, we warn that our tongue does not cut words like an ax firewood. The tongue pronounces the syllables smoothly, like a duck swimming along the river. The performance of a junior schoolchild is characterized not only by grades, but also by some indicators of the development of learning skills. One of them - reading technique.

One of them - reading technique.

How to teach a child to read quickly?

The following rules must be followed:

-

Additional reading must be regular and permanent.

-

Every evening the child should read aloud on his own. Let it be one page at the beginning, then the number of pages increases. Select literary material in accordance with the interests of the child.

-

Don't forget about the game. We read in a chain: first mother, then son; read by roles; we read only short words, then only long ones; we read words with letter combinations ORO, OLO, EP, etc.

-

You can come up with many interesting tasks for reading together. Parents show an example of smooth, fluent reading, the child tries to imitate.

-

Continue to develop attention and memory.

The better these processes are developed, the faster the reading skill will be formed.

The better these processes are developed, the faster the reading skill will be formed.

All information is taken from open sources.

If you believe your copyright has been infringed, please contact write in the chat on this site, attaching a scan of a document confirming your right.

We will verify this and immediately remove the publication.

Tips for parents to teach their child to read | Related article:

Tips for parents on how to teach a child to read

When teaching a preschooler to read, there are a number of subtleties that you need to know. Learning to read should take place in several stages. The first stage is to master the sounds, then the letters. First of all, pay attention to the fact that when teaching a preschooler to read, emphasis should be placed on memorizing sounds, not letters. That is, for example, when mastering the letter B, you need to teach the child to speak [b], and not [be]. Accordingly, [g], [t] . .., and not [ge], [te], etc.

.., and not [ge], [te], etc.

With this approach, it will be much easier for the child to understand why, for example, [b] and [a] in the syllable BA give [ba]. If you learn letters as they are pronounced in the alphabet, then you will agree that the transition from [be] and [a] to [ba] is not very natural.

So, B+A=BA

[b]+[a]=[ba]

It’s not worth being afraid that your child won’t know the correct (alphabetic) names of letters, it’s not worth it - having gone to the first grade and being able to read, he will easily learn the required letter names as they are pronounced in the alphabet.

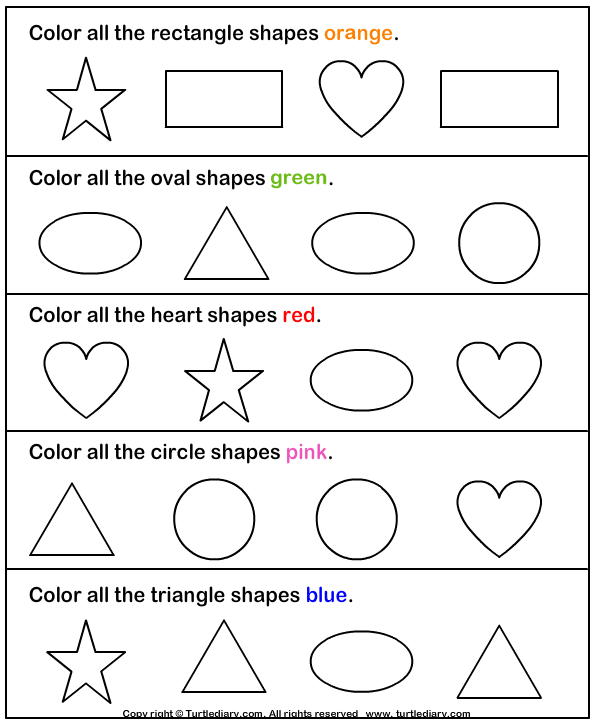

When studying letters, we first master the vowels: A.O, U, I, S, E, and then several consonants: B, C, D, D, Z, K, L, M, N, P. Already this will be enough to successfully master the syllables. And the rest of the letters "pull up" later. Remember that consonants are pronounced like sounds.

Having learned most of the letters, you can proceed to the next stage - reading the syllables made up of these letters.

At first, only syllables of the form consonant + vowel are mastered, i.e. BA, VA, GA, etc., then BO, VO, GO, etc., BU, VU, GU, etc.

Since the syllables with the vowels E, E, I, Yu are more difficult to read, at the first stage you need to read syllables only with the vowels A, O, U, I, Y, E.

Before reading syllables on paper, one must learn to read them in the "mind". Tell the child: “B, A - what will happen? That's right BA!" etc. When pronouncing the sounds B, A, it is impossible to add a union between them, because. this will prevent the baby from correctly connecting letters into syllables. After reading “in the mind”, you can proceed to reading the syllables on paper. In mastering all of the above, you will be helped by: cubes, cards with written letters, plastic letters, etc. Strive to ensure that the child, in the end, read the syllables at once, and not by letter.

Then learn with your child the syllables where the vowel comes first AB, AB, AH, etc. Children very often, especially at first, read the other way around, i.e. instead of the syllable AB - the syllable BA. Don't be discouraged, things will gradually work out. Correct it gently each time. Pay special attention to your child's diction. Speech defects that are common at this age will interfere with reading. Therefore, it is necessary to contact a speech therapist. If you feel that your child is already quite confident in reading syllables with vowels A, O, U, I, S, E, then move on to syllables with the remaining vowels E, E. Yu, I. With these vowels, syllables are most difficult for children. It's related to that. That when pronouncing each of them, we actually pronounce two sounds E = [Y] + [E], E = [Y] + [O], I = [Y] + [A], Yu = [Y] + [U]

Children very often, especially at first, read the other way around, i.e. instead of the syllable AB - the syllable BA. Don't be discouraged, things will gradually work out. Correct it gently each time. Pay special attention to your child's diction. Speech defects that are common at this age will interfere with reading. Therefore, it is necessary to contact a speech therapist. If you feel that your child is already quite confident in reading syllables with vowels A, O, U, I, S, E, then move on to syllables with the remaining vowels E, E. Yu, I. With these vowels, syllables are most difficult for children. It's related to that. That when pronouncing each of them, we actually pronounce two sounds E = [Y] + [E], E = [Y] + [O], I = [Y] + [A], Yu = [Y] + [U]

The next step is reading simple three-letter words. Move on to reading words when your child names the syllable immediately, and not by letter. O-LA, A-NYA, KO-T

Each time you move on to a new stage of reading, do not forget to repeat what you have gone through all the time.

Do not push the child, he will learn everything at his own pace, do not speed up and do not scold him if he has forgotten. It is very important that the child gets the joy of learning, along with you. If you decide to start teaching your child to read, then you need to do this in a playful way. The duration of training with children 4 years old should not exceed 10 minutes, if you see that it is difficult for a child to sit for 10 minutes, reduce the time. At this age, it is not necessary to study every day, however, try not to take long breaks (more than 3 days) With children 5- 6 years, do 15 minutes. At the first signs of fatigue, absent-mindedness, loss of interest in playing with letters, stop learning. Try to encourage the baby more often, let him be joyful, his interest in knowledge and learning in the future largely depends on this. Try to diversify the games, use your child's favorite toy as another learner, which can be actively involved in the game. Arrange competitions - who will read this or that syllable faster, you.