What age do you start reading

Reading Milestones (for Parents) - Nemours KidsHealth

Reviewed by: Cynthia M. Zettler-Greeley, PhD

Nemours BrightStart!

en español Hitos en la lectura

This is a general outline of the milestones on the road to reading success. Keep in mind that kids develop at different paces and spend varying amounts of time at each stage. If you have concerns, talk to your child's doctor, teacher, or the reading specialist at school. Getting help early is key for helping kids who struggle to read.

Parents and teachers can find resources for children as early as pre-kindergarten. Quality childcare centers, pre-kindergarten programs, and homes full of language and book reading can build an environment for reading milestones to happen.

Infancy (Up to Age 1)

Kids usually begin to:

- learn that gestures and sounds communicate meaning

- respond when spoken to

- direct their attention to a person or object

- understand 50 words or more

- reach for books and turn the pages with help

- respond to stories and pictures by vocalizing and patting the pictures

Toddlers (Ages 1–3)

Kids usually begin to:

- answer questions about and identify objects in books — such as "Where's the cow?" or "What does the cow say?"

- name familiar pictures

- use pointing to identify named objects

- pretend to read books

- finish sentences in books they know well

- scribble on paper

- know names of books and identify them by the picture on the cover

- turn pages of board books

- have a favorite book and request it to be read often

Early Preschool (Age 3)

Kids usually begin to:

- explore books independently

- listen to longer books that are read aloud

- retell a familiar story

- sing the alphabet song with prompting and cues

- make symbols that resemble writing

- recognize the first letter in their name

- learn that writing is different from drawing a picture

- imitate the action of reading a book aloud

Late Preschool (Age 4)

Kids usually begin to:

- recognize familiar signs and labels, especially on signs and containers

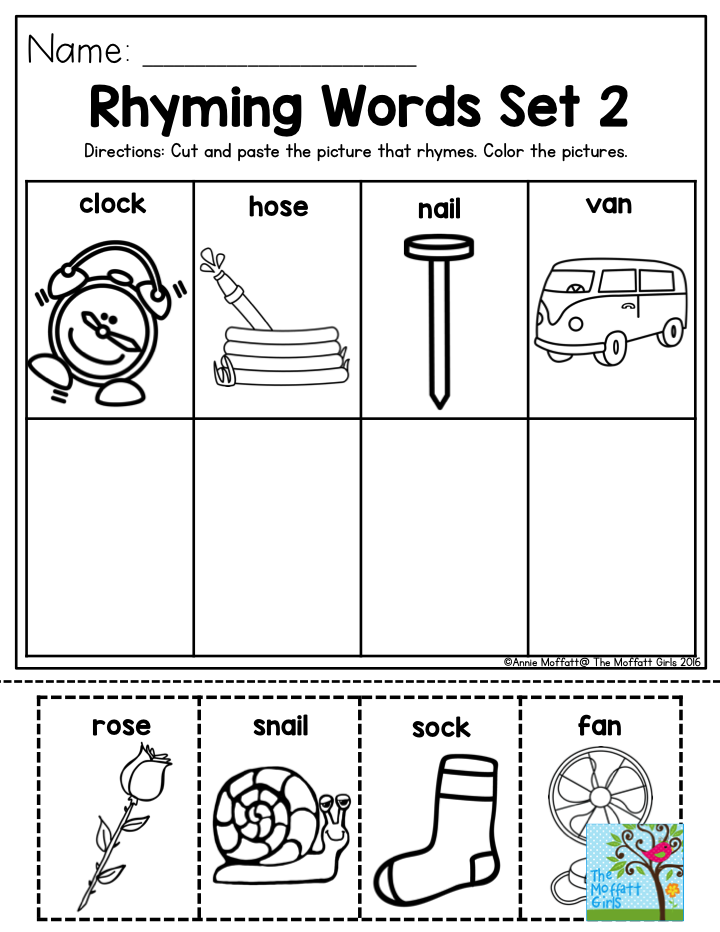

- recognize words that rhyme

- name some of the letters of the alphabet (a good goal to strive for is 15–18 uppercase letters)

- recognize the letters in their names

- write their names

- name beginning letters or sounds of words

- match some letters to their sounds

- develop awareness of syllables

- use familiar letters to try writing words

- understand that print is read from left to right, top to bottom

- retell stories that have been read to them

Kindergarten (Age 5)

Kids usually begin to:

- produce words that rhyme

- match some spoken and written words

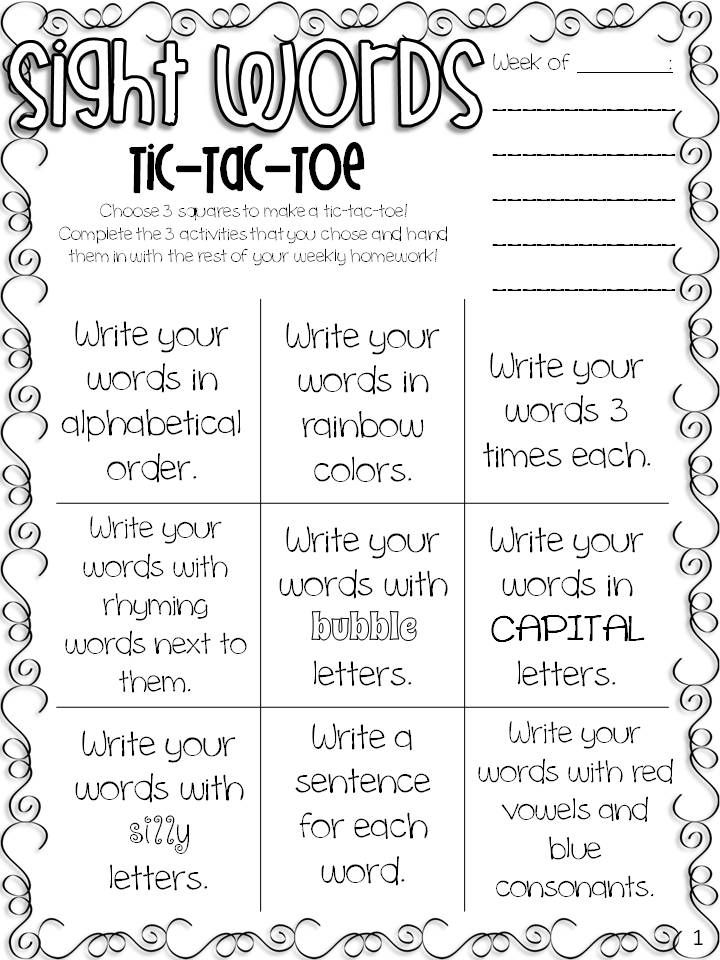

- write some letters, numbers, and words

- recognize some familiar words in print

- predict what will happen next in a story

- identify initial, final, and medial (middle) sounds in short words

- identify and manipulate increasingly smaller sounds in speech

- understand concrete definitions of some words

- read simple words in isolation (the word with definition) and in context (using the word in a sentence)

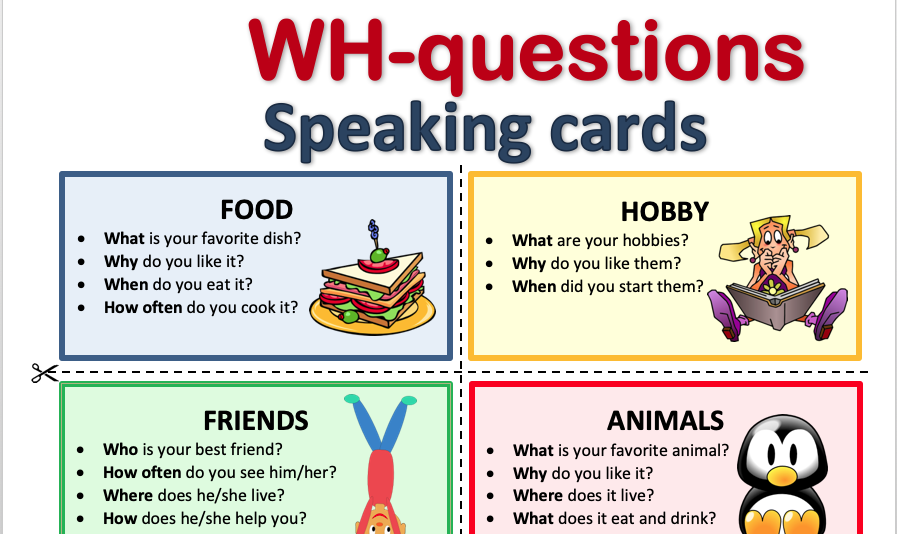

- retell the main idea, identify details (who, what, when, where, why, how), and arrange story events in sequence

First and Second Grade (Ages 6–7)

Kids usually begin to:

- read familiar stories

- "sound out" or decode unfamiliar words

- use pictures and context to figure out unfamiliar words

- use some common punctuation and capitalization in writing

- self-correct when they make a mistake while reading aloud

- show comprehension of a story through drawings

- write by organizing details into a logical sequence with a beginning, middle, and end

Second and Third Grade (Ages 7–8)

Kids usually begin to:

- read longer books independently

- read aloud with proper emphasis and expression

- use context and pictures to help identify unfamiliar words

- understand the concept of paragraphs and begin to apply it in writing

- correctly use punctuation

- correctly spell many words

- write notes, like phone messages and email

- understand humor in text

- use new words, phrases, or figures of speech that they've heard

- revise their own writing to create and illustrate stories

Fourth Through Eighth Grade (Ages 9–13)

Kids usually begin to:

- explore and understand different kinds of texts, like biographies, poetry, and fiction

- understand and explore expository, narrative, and persuasive text

- read to extract specific information, such as from a science book

- understand relations between objects

- identify parts of speech and devices like similes and metaphors

- correctly identify major elements of stories, like time, place, plot, problem, and resolution

- read and write on a specific topic for fun, and understand what style is needed

- analyze texts for meaning

Reviewed by: Cynthia M. Zettler-Greeley, PhD

Date reviewed: May 2022

What is the best age to learn to read?

Loading

Family Tree | Education

What is the best age to learn to read?

(Image credit: Ozge Elif Kizil/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

By Melissa Hogenboom

2nd March 2022

In some countries, kids as young as four learn to read and write. In others, they don't start until seven. What's the best formula for lasting success? Melissa Hogenboom investigates.

I

I was seven years old when I started to learn to read, as is typical of the alternative Steiner school I attended. My own daughter attends a standard English school, and started at four, as is typical in most British schools.

Watching her memorise letters and sound out words, at an age when my idea of education was climbing trees and jumping through puddles, has made me wonder how our different experiences shape us. Is she getting a crucial head-start that will give her lifelong benefits? Or is she exposed to undue amounts of potential stress and pressure, at a time when she should be enjoying her freedom? Or am I simply worrying too much, and it doesn't matter at what age we start reading and writing?

Is she getting a crucial head-start that will give her lifelong benefits? Or is she exposed to undue amounts of potential stress and pressure, at a time when she should be enjoying her freedom? Or am I simply worrying too much, and it doesn't matter at what age we start reading and writing?

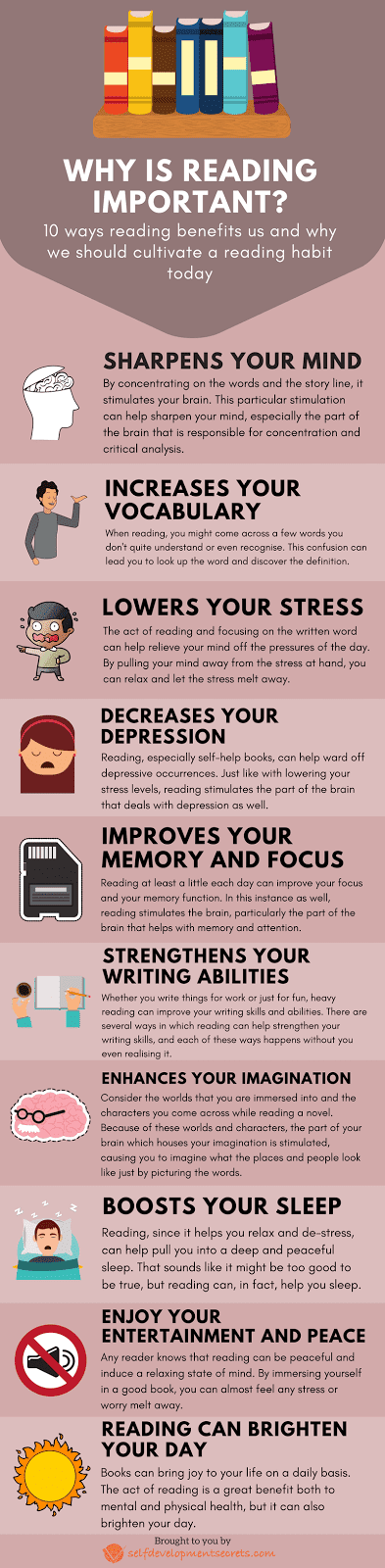

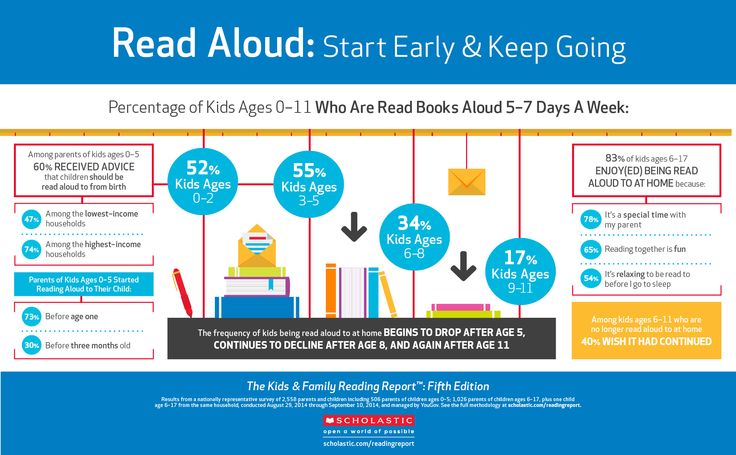

There's no doubt that language in all its richness – written, spoken, sung or read aloud – plays a crucial role in our early development. Babies already respond better to the language they were exposed to in the womb. Parents are encouraged to read to their children before they are even born, and when they are babies. Evidence shows that how much or how little we are talked to as children can have lasting effects on future educational achievement. Books are a particularly important aspect of that rich linguistic exposure, since written language often includes a wider and more nuanced and detailed vocabulary than everyday spoken language. This can in turn help children increase their range and depth of expression.

Since a child's early experience of language is considered so fundamental to their later success, it has become increasingly common for preschools to begin teaching children basic literacy skills even before formal education starts. When children begin school, literacy is invariably a major focus. This goal of ensuring that all children learn to read and write has become even more pressing as researchers warn that the pandemic has caused a widening achievement gap between wealthier and poorer families, increasing academic inequality.

There are many ways to enjoy reading. In this Namibian school, blind and visually impaired children learn the Braille script (Credit: Oleksandr Rupeta/NurPhoto/Getty Images)

Family Tree

In many countries, formal education starts at four. The thinking often goes that starting early gives children more time to learn and excel. The result, however, can be an "education arms race", with parents trying to give their child early advantages at school through private coaching and teaching, and some parents even paying for children as young as four to have additional private tutoring.

Compare that to the more play-based early education of several decades ago, and you can see a huge change in policy, based on very different ideas of what our children need in order to get ahead. In the US, this urgency sped up with policy changes such as the 2001 "no child left behind" act, which promoted standardised testing as a way to measure educational performance and progress. In the UK, children are tested in their second year of school (age 5-6) to check they are reaching the expected reading standard. Critics warn that early testing like this can put children off reading, while proponents say it helps to identify those who need additional support.

However, many studies show little benefit from an early overly-academic environment. One 2015 US report says that society's expectations of what children should achieve in kindergarten has changed, which is leading to "inappropriate classroom practices", such as reducing play-based learning.

The risk of "schoolification"

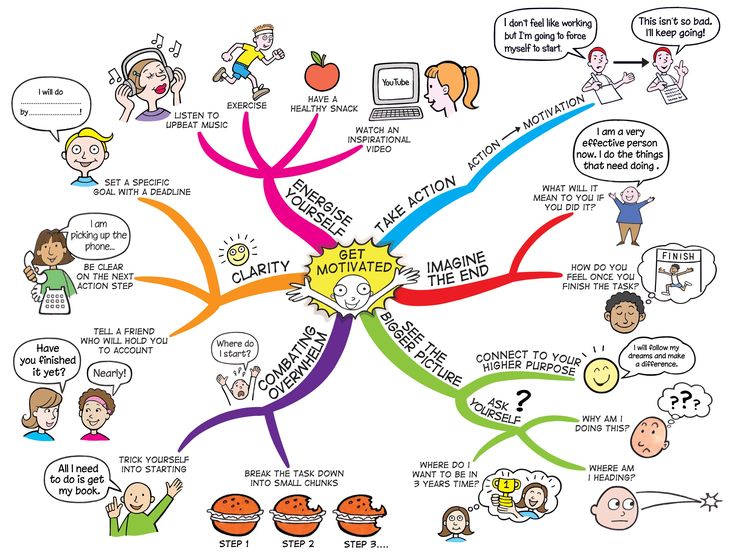

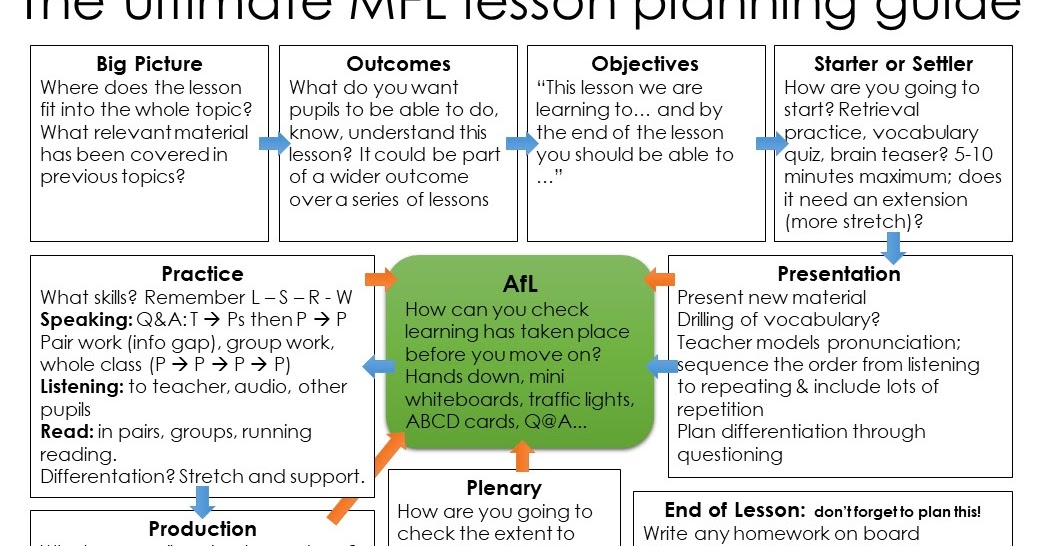

How children learn and the quality of the environment is hugely important. "Young children learning to read is one of the most important things primary education does. It's fundamental to children making progress in life," says Dominic Wyse, a professor of primary education at University College London, in the UK. He, alongside sociology professor Alice Bradbury, also at UCL, has published research proposing that the way we teach literacy really matters.

"Young children learning to read is one of the most important things primary education does. It's fundamental to children making progress in life," says Dominic Wyse, a professor of primary education at University College London, in the UK. He, alongside sociology professor Alice Bradbury, also at UCL, has published research proposing that the way we teach literacy really matters.

In a 2022 report, they state that English school system's intense focus on phonics – a method that involves matching the sound of a spoken word or letter, with individual written letters, through a process called "sounding out" – could be failing some children.

A reason for this, says Bradbury, is that the "schoolification of early years" has resulted in more formal learning earlier on. But the tests used to assess that early learning may have little to do with the skills actually needed to read and enjoy books or other meaningful texts.

For example, the tests may ask pupils to "sound out" and spell nonsense words, to prevent them from simply guessing, or recognising familiar words. Since nonsense words are not meaningful language, children may find the task difficult and puzzling. Bradbury found that the pressure to gain these decoding skills – and pass reading tests – also means that some three-year-olds are already being exposed to phonics.

Since nonsense words are not meaningful language, children may find the task difficult and puzzling. Bradbury found that the pressure to gain these decoding skills – and pass reading tests – also means that some three-year-olds are already being exposed to phonics.

"It doesn't end up being meaningful, it ends up being memorising rather than understanding context," says Bradbury. She also worries that the books used are not particularly engaging.

Language in all its richness – written, spoken, sung or read aloud – plays a crucial role in our early development (Credit: Xie Chen/VCG via Getty Images)

Neither Wyse nor Bradbury make the case for later learning per se, but rather highlight that we should rethink the way children are taught literacy. The priority, they say, should be to encourage an interest in and familiarity with words, using storybooks, songs and poems, all of which help the child pick up the sounds of words, as well as expanding their vocabulary.

This idea is backed up by studies that show that the academic benefits of preschool fade away later on. Children who attend intensive preschools do not have higher academic abilities in later grades than those who did not attend such preschools, several studies now show. Early education can however have a positive impact on social development – which in turn feeds into the likelihood of graduation from school and university as well as being associated with lower crime rates. In short, attending preschool can have positive effects on later achievement in life, but not necessary on academic skills.

Children who attend intensive preschools do not have higher academic abilities in later grades than those who did not attend such preschools, several studies now show. Early education can however have a positive impact on social development – which in turn feeds into the likelihood of graduation from school and university as well as being associated with lower crime rates. In short, attending preschool can have positive effects on later achievement in life, but not necessary on academic skills.

Too much academic pressure may even cause problems in the long run. A study published in January 2022 suggested that those who attended a state-funded preschool with a strong academic emphasis, showed lower academic achievements a few years later, compared to those who had not gained a place.

This chimes with research on the importance of play-based learning in the early years. Child-led play-based preschools have better outcomes than more academically focussed preschools, for example.

One 2002 study found that "children's later school success appears to have been enhanced by more active, child-initiated early learning experiences", and that overly formalised learning could have slowed progress. The study concluded that "pushing children too soon may actually backfire when children move into the later elementary school grade".

Similarly, another small study found that disadvantaged children in the US who were randomly assigned to a more play-based setting had lower behavioural issues and emotional impairments at age 23, compared to children who had been randomly assigned to a more "direct instruction" setting.

Preschool studies like these don't shed light on the impact of early literacy per se, and small studies in single locations must always be treated with care, but they suggest that how it is taught, matters. One reason why early education can result in positive social outcomes later in life may have nothing to do with the teaching at all, but with the fact that it provides childcare. This means parents can work uninterrupted and provide more income to the family home.

This means parents can work uninterrupted and provide more income to the family home.

Anna Cunningham, a senior lecturer in psychology at Nottingham Trent University who studies early literacy, argues that if a setting is too academically focused early on, it can cause the teachers to become stressed over tests and results, which can in turn affect the kids. "Of course it's not good to judge a five-year-old on their results," she says. Parental anxiety about how well their child is doing at school can also feed into this: according to a survey commissioned by an educational charity in the UK, school performance is one of parents' top concerns.

With the right support, children can learn to read in a wide range of settings, like this open-air school in Dhaka, Bangladesh (Credit: Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

Later start, better outcomes?

Not everyone favours an early start. In many countries, including Germany, Iran and Japan, formal schooling starts at around six. In Finland, often hailed as the country with one of the best education system in the world, children begin school at seven.

In Finland, often hailed as the country with one of the best education system in the world, children begin school at seven.

Despite that apparent lag, Finnish students score higher in reading comprehension than students from the UK and the US at age 15. In line with that child-centred approach, the Finnish kindergarten years are filled with more play and no formal academic instruction.

Following this model, a 2009 University of Cambridge review proposed that the formal school age should be pushed back to six, giving children in the UK more time "to begin to develop the language and study skills essential to their later progress", as starting too early could "risk denting five-year-olds' confidence and causing long-term damage to their learning".

Research does back up this idea of starting later. One 2006 kindergarten study in the US showed there was improvement in test scores for children who delayed entry by one year.

Other research comparing early versus late readers, found that later readers catch up to comparable levels later on – even slightly surpassing the early readers in comprehension abilities. The study, explains lead author Sebastian Suggate, of the University of Regensburg in Germany, shows that learning later allows children to more efficiently match their knowledge of the world – their comprehension – to the words they learn. "It makes sense," he says. "Reading comprehension is language, they've got to unlock the ideas behind it."

The study, explains lead author Sebastian Suggate, of the University of Regensburg in Germany, shows that learning later allows children to more efficiently match their knowledge of the world – their comprehension – to the words they learn. "It makes sense," he says. "Reading comprehension is language, they've got to unlock the ideas behind it."

"Of course if you spend more time focusing on language earlier on, you are building a strong foundation of skills that takes years to develop. Reading can be picked up quickly but for language (vocabulary and comprehension) there's no cheap tricks. It's hard work," says Suggate. In other work looking at differing school entry ages, he found that learning to read early had no discernible benefits at age 15.

The question remains that if reading ability is not improved by learning early, then why start early? Individual variation in reading appetite and ability are one important aspect.

"Children are hugely different in terms of their foundational skills when they start school or start learning to read," explains Cunningham. In her study of Steiner-educated children, who only start formal education at about seven, she had to exclude 40% of the sample as the children could already read. "I think that's because they were ready for it," she says. She also found the older children were more ready "to learn the process to read in terms of their underlying language skills" because they had had three extra years of language exposure.

In her study of Steiner-educated children, who only start formal education at about seven, she had to exclude 40% of the sample as the children could already read. "I think that's because they were ready for it," she says. She also found the older children were more ready "to learn the process to read in terms of their underlying language skills" because they had had three extra years of language exposure.

World Book Day celebrates the joy of reading, and has become increasingly popular. Here, British Olympic Gold Medallist Greg Rutherford joins in (Credit: Matt Alexander/PA Wire)

Studies also show that reading ability is more closely linked to a child's vocabulary than to their age, and that spoken language skills are a high predictor of later literary skills. However, we know that many children who enter school are behind on their language skills, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds. Some argue that formal teaching allows these children to access the support and skills that others may pick up informally at home. This line of thinking is espoused by UK educational authorities, who say that teaching reading early to those behind on their spoken language is "the only effective route to closing this [language ability] gap".

This line of thinking is espoused by UK educational authorities, who say that teaching reading early to those behind on their spoken language is "the only effective route to closing this [language ability] gap".

Others favour the opposite approach, of immersing children in an environment where they can enjoy and develop their language comprehension, which is after all central to reading success. This is exactly what a playful learning setting helps encourage. "The job of teaching is to assess where your children are and give them the most appropriate teaching related to their level of development," says Wyse. The 2009 Cambridge review echoed this and stated: "There is no evidence that a child who spends more time learning through lessons – as opposed to learning through play – will 'do better' in the long run."

Cunningham, whose daughter has also recently started learning to read, has a reassuringly generous view of the ideal reading age: "It doesn't matter whether you start to read at four or five or six as long as the method they are taught is a good, evidenced method. Children are so resilient they will find opportunities to play in any context."

Children are so resilient they will find opportunities to play in any context."

Our obsession with early literacy appears to be somewhat unfounded, then – there's no need, nor clear benefit of rushing it. On the other hand, if your child is starting early, or shows an independent interest in reading before their school offers it, that's fine too, as long as there is plenty of opportunity to down tools and have fun along the way.

* Melissa Hogenboom is the editor of BBC Reel. Her book, The Motherhood Complex, is out now. She is @melissasuzanneh on Twitter.

--

Join one million Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter or Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.

A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife, Travel and Reel delivered to your inbox every Friday.

When to start reading books to your child

So when, when should you start reading books to your child? With all due respect to psychologists, it is hardly worth attacking a newborn baby with a book. That does not negate the need and benefit of communication. Talk to the child so that the child will speak to you as soon as possible, tell poems and fairy tales, sing songs. But let's be honest, how many of them do you remember? Poems and fairy tales?

If you are a storehouse of folk wisdom, then, of course, you can do without a book for now. Otherwise, books will be a great help to you. Fairy tales, poems, fables, stories, counting rhymes, nursery rhymes - there is everything in the books. Children are very receptive to rhyme, poetry will appeal to almost every kid. But you can even read novels to him, children not only like to hear the voice of loved ones, loving people, they need it.

Children are very receptive to rhyme, poetry will appeal to almost every kid. But you can even read novels to him, children not only like to hear the voice of loved ones, loving people, they need it.

Intending to make a child friends with a book seriously, you should take into account both the general stages of development of children and the individual characteristics of your baby. To help you figure out at what age to start reading books, we offer a small cheat sheet by age.

Age 3 - 6 months

The baby begins to crawl, study objects, babble. Read to him or tell him, that is the question? Tell me! At this stage, the best book for him is you. Tell what you remember by heart, fairy tales familiar from childhood, favorite poems. Learn new ones: nursery rhymes, songs, boring tales (a hit for all time is a fairy tale about a white bull, but there are actually a lot of them).

Children love repetition (you will have time to make sure of this). And, for the future, if the baby asks, do not refuse to read the tale of the chicken Ryaba for the five hundredth time, do not be angry with him. Repetitions help children learn not only new words, but also speech turns, phrase construction.

And, for the future, if the baby asks, do not refuse to read the tale of the chicken Ryaba for the five hundredth time, do not be angry with him. Repetitions help children learn not only new words, but also speech turns, phrase construction.

You can read a book before going to bed, and during the day tell: while you are going for a walk, play with your little one, dress or bathe him. He will respond, answer you (even if for now only boo-boo and ha-ha), and you address him by name. It is a good idea to insert the name of your baby, on occasion, into rhymes (for example, the gate creaks and creaks, and our Petya / Olya sleeps and sleeps).

As for the interaction with the book, then, let's be honest: at this age, children most of all like to nibble on them. Therefore, it is better to buy a rattle or a teether for a baby, but for yourself - a good collection of baby rhymes, it will come in handy for you.

Age 6 – 9 months

The kid takes the first steps, plays with other children, actively interacts with objects, repeats syllables and simple words after adults. It's time to introduce him to the book! But we must understand that at first the book will be more of a toy. There is no need to be afraid of this, it is useful and correct.

It's time to introduce him to the book! But we must understand that at first the book will be more of a toy. There is no need to be afraid of this, it is useful and correct.

You will still have time to introduce your child to the masterpieces of world literature, and now you are starting to teach him to use a book as you teach him to use a spoon or other everyday item. While playing, children learn the simplest actions - turn pages, understand where to look, where the beginning and where the end of the book is.

Many excellent children's books are now being published:- ⚫ soft sensory books,

- ⚫ bathing books,

- ⚫ transformers with moving valves,

- ⚫ folding pictures.

Looking at illustrations, repeating words after you, touching textured inserts, your baby develops fine motor skills, coordination, sensory abilities and communication skills. And, of course, learns to love the book, because it brings so much joy!

Age 9 – 12 months

This age can be described in two words - all by yourself! The kid tries to walk without support, sit, eat on his own, pronounce the first words, initiate communication with his parents, listen with pleasure as his mother (or father) reads to him, examines the pictures. It is with looking at the pictures that the meaningful interaction of the child with the book begins. The book is not just an object, but a source of information about the real world and the world of imagination, and he learns to discover these worlds for himself.

It is with looking at the pictures that the meaningful interaction of the child with the book begins. The book is not just an object, but a source of information about the real world and the world of imagination, and he learns to discover these worlds for himself.

Sit with your baby in an embrace so that it is convenient for you to hold and read a book, and for him to watch. Pictures are better to choose bright, but as simple as possible, with the image of one or two characters or objects. Colorfully designed fairy tales, illustrated dictionaries of the first words will do. Parents will also have to try: memorized rhymes are no longer enough, it's time to improvise. Choose a book with illustrations, according to which you yourself can tell a story, for a start it’s quite simple - who is shown in the picture? What are you wearing? What is he doing? What does he say?

Be ready to read expressively, in faces, depicting characters, croak and meow, squeak and growl - this will help the baby to distinguish and better remember the characters, and, of course, he will like it! Try it, you will like it too. Sometimes it is also useful for serious, adult people to fool around. But, of course, for reading before bed, it is better to choose something rhythmic, read or hum in a calm manner.

Sometimes it is also useful for serious, adult people to fool around. But, of course, for reading before bed, it is better to choose something rhythmic, read or hum in a calm manner.

Age from one to two

By the age of one and a half, a kid usually already utters short phrases, dances, sings along, begins to draw (goodbye, wallpaper!), Recognizes images in pictures, understands a short story or a fairy tale. Pictures are still very important, they help very young children build a plot sequence for themselves, but this is the beginning of real, real reading. Sit your child on your lap (so it will be easier for him to concentrate), and start reading!

When rereading your favorite fairy tale, pause so that the baby can finish the phrase, insert a familiar word, but if it doesn’t work out yet, it doesn’t matter - tell me, offer to repeat after you. The same with pictures. Ask who is pictured, what they are doing, or ask them to show you where a certain character is drawn.

This is an important stage of development, your little listener slowly becomes an interlocutor. But, if it is difficult for him to sit still, do not force him. At this age, children have a lot to do: they learn new movements, learn to jump, like to sculpt, assemble a designer (by the way, the development of fine motor skills is directly related to the development of speech).

From the age of one, children begin to form their own taste. Perhaps your child just doesn't like a certain book. In this case, give him the opportunity to choose for himself (for this, a shelf with children's books should be in a place accessible to the child).

Two to three years of age

The child independently performs the main actions, actively communicates with adults, with other children, he develops self-esteem (most often he evaluates himself as “good” - and you can’t argue!), He not only listens with pleasure to poems, fairy tales, stories, but already and tells himself.

Teremok, Gingerbread Man, Chicken Ryaba - a great choice for this age. You can also start reading children's encyclopedias, stories about animals, long poems. Showing the baby pictures, ask them to tell what is drawn there, this contributes to the development of speech and imagination. Discuss the heroes of the fairy tale, their actions (for example, where did the Bear go, is he good or bad). And, if you are not reading a fairy tale for the first time, offer to continue it from some point to train memory and attention.

But these are all pretty general guidelines. We hope that they will be useful, but you should not take them as an unconditional guide to action. You need to focus solely on the abilities and needs of your child. It happens that even at three months, a baby listens to fairy tales with bated breath, but if your one-year-old is still trying to nibble on a book and likes to play patties more, do not force him to sit and listen. Everything has its turn. There is no need to turn reading together into a heavy duty, either for yourself or for the child. Your little one has a long road of knowledge ahead, let him walk it with joy. Even the stern samurai Yamamoto Tsunetomo, in his treatise Hidden in the Leaves, strongly recommended not to punish children under four years old - so that the baby, not knowing fear, would grow up inquisitive and courageous.

There is no need to turn reading together into a heavy duty, either for yourself or for the child. Your little one has a long road of knowledge ahead, let him walk it with joy. Even the stern samurai Yamamoto Tsunetomo, in his treatise Hidden in the Leaves, strongly recommended not to punish children under four years old - so that the baby, not knowing fear, would grow up inquisitive and courageous.

Where to start reading?

Little white fish.

Age recommendation 1+.

A series of books by Belgian author Guido Van Genechten about the adventures of a small white fish and its friends: red crab, blue whale, green turtle and many others. The illustrations are bright, colorful characters are easier to recognize and remember. The paper is thick enough not to tear or wrinkle, so the books are suitable for younger children as well. Simple but captivating stories are sure to please both your baby and you.

Bunny Styopa and a pot.

Age recommendation 2+.

An excellent series of educational help books from Andrian Hayman. The illustrations are large and colorful, the book is in a convenient format, on thick cardboard. The text will help to explain to the child in a fun and intelligible way how to dress, use the potty, go to the doctor. The books in the series will also be useful for older children, and kids who are still too early to potty will surely love pictures with the cutest bunny Styopa.

Crocodile, I have to go - I'm leaving in the morning!

Age recommendation 3+.

A funny book in verse by Sally Hopgood about a sluggish baby turtle who decides to leave the zoo, but first to say goodbye to all his friends. Wonderful illustrations that will introduce your baby to animals: there is a crocodile, and an antelope, and a snail, and a cat. The lyrics are simple, funny and easy to memorize. The cover is soft, the paper is coated. The book will be interesting even for the smallest, but, unfortunately, the pages are easy to tear.

The cover is soft, the paper is coated. The book will be interesting even for the smallest, but, unfortunately, the pages are easy to tear.

At what age should a bilingual child be taught to read Russian?

I am very glad to all your questions and continue my Christmas stories about the wonderful world of sounds and letters. It's time to move on to one of the most important questions:

- At what age can a child be taught to read?

- I must say right away that this does not depend on age. It's time to start teaching the child to read then, when he is ready for it . And when answering this question, searching the Russian-speaking Internet will not help you. For the simple reason that it correctly and in detail describes the situation of readiness to learn to read for a monolingual child who is preparing for school, that is, 6-7 years old.

Our situation is completely different - children go to school from the age of 4, and they are bilingual. And here we have another main task of teaching reading, no matter how paradoxical it may sound. We teach to read, first of all, in order to develop and retain the Russian language . So that the child has a visual support as early as possible in the form of a syllable, a word and a short sentence, which will allow him to develop phrasal speech, expand his vocabulary and, thus, preserve the Russian language, which after 4 years is on the periphery of his speech activity - a few hours after school with a Russian-speaking parent, and sometimes less. And it is not the main language of knowledge of the world, that is, the language of the educational and play activities of the child. The task of enjoying reading, of regularly reading books in Russian, arises only at the second, later stage, when Russian is preserved. By the way, this stage begins approximately at the age of the beginning of the first grade in Russian-speaking countries - from 6 years old.

And here we have another main task of teaching reading, no matter how paradoxical it may sound. We teach to read, first of all, in order to develop and retain the Russian language . So that the child has a visual support as early as possible in the form of a syllable, a word and a short sentence, which will allow him to develop phrasal speech, expand his vocabulary and, thus, preserve the Russian language, which after 4 years is on the periphery of his speech activity - a few hours after school with a Russian-speaking parent, and sometimes less. And it is not the main language of knowledge of the world, that is, the language of the educational and play activities of the child. The task of enjoying reading, of regularly reading books in Russian, arises only at the second, later stage, when Russian is preserved. By the way, this stage begins approximately at the age of the beginning of the first grade in Russian-speaking countries - from 6 years old.

It is also important to understand that readiness criteria for learning to read in a bilingual child is formed in two languages and may not be developed in the same way in each language . And if in the Russian language some moment is not fully formed, but it is formed in English, then this does not interfere with starting to teach the child to read in Russian.

And if in the Russian language some moment is not fully formed, but it is formed in English, then this does not interfere with starting to teach the child to read in Russian.

What are these criteria for a child's readiness to learn to read ?

Experts consider three main aspects of a child's readiness to learn to read: psychological, speech and phonemic . What exactly do they mean and what are the key points for us to start teaching a bilingual child to read in Russian and what can we turn a blind eye to?

Psychological readiness for reading is associated with the development of the child's cognitive activity and his readiness for learning activities in general. How to define it? Ask yourself the following questions:

Does the book itself arouse curiosity in the child? When you walk into a bookstore or library, do the books spark a keen interest? Does your child like looking at books?

Does he try to "write" his own "book" by sticking pictures on a folded piece of paper or drawing them?

Does he ask an adult to read a book to him? Would he prefer reading a book or looking at pictures to a TV or a computer? Does he enjoy a bedtime reading ritual, if there is such a thing?

Does he try to “read” the book himself, imitating reading and imitating adults?

For parents of bilingual children, it is clear that it is not very important whether the child is drawn to Russian or English books. It is clear that the books in the store or library are in English, but it is also clear that this does not matter. It doesn't matter if the child tries to write in Latin or Cyrillic, or asks to read an English-speaking or Russian-speaking parent. Our bilingual baby lives in the world of two languages at the same time, simultaneously in two “book worlds”, without separating them in terms of psychological readiness for reading and learning.

It is clear that the books in the store or library are in English, but it is also clear that this does not matter. It doesn't matter if the child tries to write in Latin or Cyrillic, or asks to read an English-speaking or Russian-speaking parent. Our bilingual baby lives in the world of two languages at the same time, simultaneously in two “book worlds”, without separating them in terms of psychological readiness for reading and learning.

Speech readiness , according to monolingual criteria, includes a rich vocabulary, the ability to speak in extended extended sentences, knowledge of poems and songs, the ability to listen and retell fairy tales, solve riddles. Of course, we should take such criteria calmly.

It must be remembered that we are going to teach a bilingual child to read in Russian in order to develop his speech and move towards the named criteria. And do not start, relying on them. Our baby can sing in English and not know a single Russian song, not be able to solve Russian riddles, but I would not particularly worry about this. His total vocabulary in both languages usually exceeds that of his advanced monolingual peer, and active grammatical constructions in speech include two grammatical systems that he already separates well. Not to mention the intonations of both languages, the ability to feel the speech situation and context.

His total vocabulary in both languages usually exceeds that of his advanced monolingual peer, and active grammatical constructions in speech include two grammatical systems that he already separates well. Not to mention the intonations of both languages, the ability to feel the speech situation and context.

But the phonemic readiness of is a key point for us. But there is some amazing news! It consists in the fact that this readiness in a bilingual baby is formed easier than precisely because he had to learn to hear and pronounce twice as many sounds very early and his phonemic perception developed more intensively. In the world of sounds, a bilingual child is a much more serious expert than a monolingual child. It is very important for us to support and preserve this “experience of absorbing sounds” in order to develop literacy in Russian on its basis. Our language is phonetic, we write by ear. Spelling is important, but secondary to auditory writing skill.

What exactly do we need to form for a child's phonemic readiness? Let's make a short list:

The ability to clap words by syllables and the ability to say how many times clapped (name the number of syllables).

The ability to distinguish the first sound in a word.

The ability to name words for a given sound. For example, to the sound O or the sound A. (Not to the letter! The child will only learn letters🙂, while he already hears the sounds.)

The ability to select words to rhyme. And it doesn't really matter what language. Although, of course, it is very desirable that the child could name “words that sound similar” in Russian. For example, poppy varnish.

The ability to hear a certain sound in a word and the same sound in other words. For example, in the word mouse-sh-sh-shka you hear "wind song: sh-sh-sh-sh". Show objects that also have “wind song” in their name. You need to select pictures whose names contain the sound [Ш] from a set of cards on which, for example, are drawn: skis, tires, sleds, a car, a wheel. That is, the child must be able to differentiate consonants by ear. In this case W-W-S.

That is, the child must be able to differentiate consonants by ear. In this case W-W-S.

Is it necessary for a bilingual child to pronounce all the sounds of the Russian language clearly in order to learn to read Russian? I will express a seditious thought - no, not necessarily. Moreover, teaching reading in our country leads to two very important results: a significant improvement in pronunciation in Russian and the prevention of an English accent in it. In children with an English accent that has already appeared, it goes away, softens, and with regular and not at all difficult exercises, you can remove it.

It is highly desirable that the child could hold a pencil - paint, be able to draw straight and oblique lines. But this is usually done by most British children by the age of 4-5. Namely, at this age it is optimal to start teaching a bilingual child to read in Russian. Some a little earlier, some a little later, of course. As far as readiness, psychological and phonemic first of all.