Where the wild things are story text

Novelas

Los resultados que se exponen en la presente página sobre «Novela y su traducción» es fruto de mi docencia e investigación a lo largo de los últimos veinte años sobre el estado de la traducción de la narrativa clásica del siglo XIX y XX, principalmente del ámbito anglo-norteamericano. Los textos están dispuestos en columnas paralelas para poder ser cotejados con facilidad, precisión y rigor. Encontraréis ya casi unas doscientas obras clásicas de entre las quinientas que proyecto investigar en los próximos años. En algún que otro caso hay además traducciones en algún otro idioma a fin de poder comparar cómo se hacen dichas traducciones en otros países, así como traducciones inversas por idénticas razones comparativas. Gracias a esta metodología se puede ver de forma fehaciente y ágil el estado de las traducciones abordadas. Al hacerlo, os encontraréis con aciertos pero también con sorpresas pasmosas como podéis comprobarlo por vosotros mismos en The old man and the sea / El viejo y el mar de Ernest Hemingway; o si preferís, leed el informe adjunto a la misma de una media docena de páginas sobre el estado de esta traducción.

Como en la novela anterior hay bastantes obras ya anotadas, otras a medias y unas pocas tienen al menos colocados los textos en columnas y a punto de empezar a ser anotadas. En unas y otras el proceso de anotación, revisión y evaluación es continuo. En las anotaciones empleo subrayados ( ______ ) para indicar mis dudas sobre la corrección de la traducción, o para indicar la ausencia de la misma; también utilizo cruces rojas ( X ) al margen para indicar que dicha traducción es cuando menos errónea o que no consta. Generalmente subrayo también el texto de partida para mejor localización de su correspondencia, salvo en numerosas instancias del Ulysses de James Joyce. También hay algún que otro comentario al margen y a veces una traducción alternativa para que se vea que es posible su equivalencia. El resaltado del texto en negrita o/e igual color tiene como objeto una más rápida localización; la mayoría de estas palabras o expresiones suelen tener definiciones sinonímicas o imágenes al margen como podéis comprobar en el corto relato de ‘The birds’ / ‘Los pájaros’ de Daphne du Maurier.

Para todas las obras se intenta referir un audio en mp3 del texto original a fin de que al escucharlo se pueda ir leyendo el texto de llegada, lo que agiliza el cotejo. Esta estrategia refuerza el propósito general de la página que es no sólo dar cuenta del estado de las traducciones sino también facilitar el aprendizaje cabal de ambas lenguas en el ejercicio tanto del cotejo como de la escucha. Realizar una correcta traducción literaria no consiste sólo en transvasar la equivalencia lingüística per se sino también en mantener el funcionamiento de los elementos literarios universales implícitos tales como tono, estructura, punto de vista, focalización, registro, frecuencia de uso, etcétera y que, como se verá, casi nunca se transvasan aunque a veces suene correcta la expresión. Estos elementos de equivalencia universal tienen que manifestarse con igual función en el texto de llegada, algo que lamentablemente no sucede casi nunca, con lo que se tergiversa el significado y la visión última de la obra que se cree haber traducido.

Para todas las obras se intenta referir un audio en mp3 del texto original a fin de que al escucharlo se pueda ir leyendo el texto de llegada, lo que agiliza el cotejo. Esta estrategia refuerza el propósito general de la página que es no sólo dar cuenta del estado de las traducciones sino también facilitar el aprendizaje cabal de ambas lenguas en el ejercicio tanto del cotejo como de la escucha. Realizar una correcta traducción literaria no consiste sólo en transvasar la equivalencia lingüística per se sino también en mantener el funcionamiento de los elementos literarios universales implícitos tales como tono, estructura, punto de vista, focalización, registro, frecuencia de uso, etcétera y que, como se verá, casi nunca se transvasan aunque a veces suene correcta la expresión. Estos elementos de equivalencia universal tienen que manifestarse con igual función en el texto de llegada, algo que lamentablemente no sucede casi nunca, con lo que se tergiversa el significado y la visión última de la obra que se cree haber traducido. Julián Rodríguez

Julián Rodríguez

Julián Rodríguez

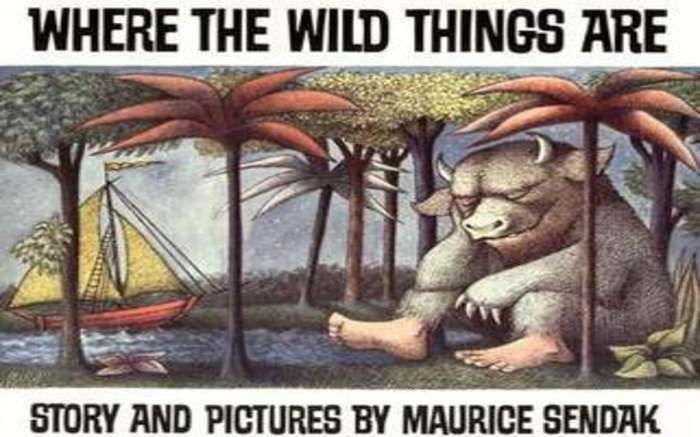

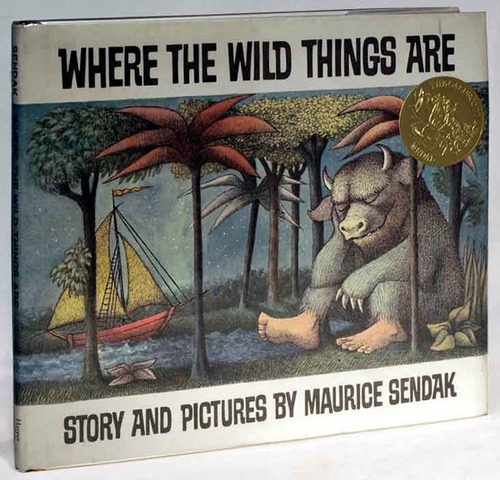

Queer and Jewish Identity Are the Heart of “Where the Wild Things Are”

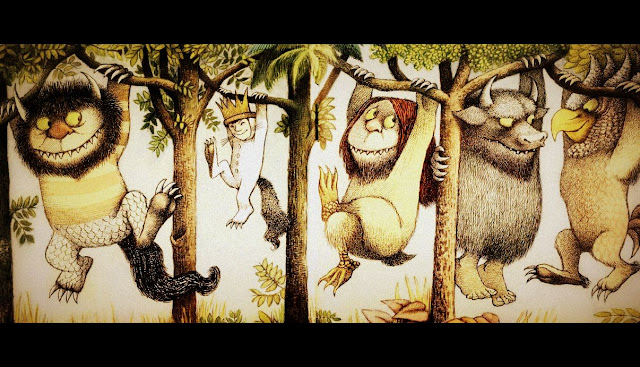

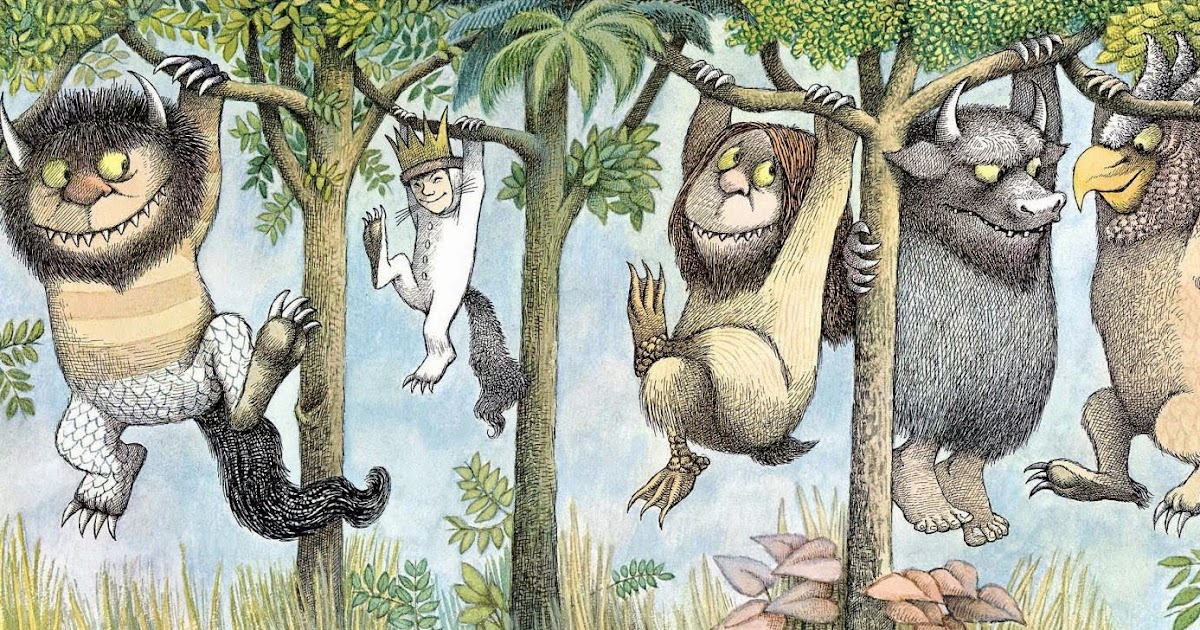

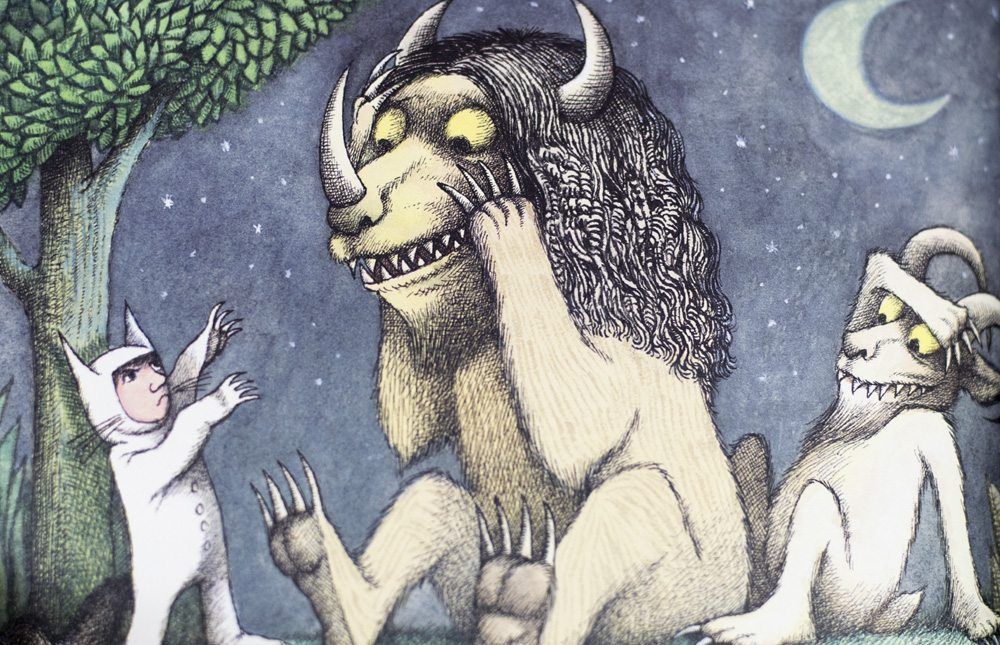

Maybe you’re familiar with this story: A young boy in a white wolf costume is sent to his room after he runs around the house, terrorizing his family, screaming at his mother, “I’LL EAT YOU UP!” After being sent to bed with no dinner, the boy finds himself in a strange new world, filled with vines and trees and terrible creatures he calls the “Wild Things.” He becomes the king, the wildest thing of them all.

When Where the Wild Things Are was first published in 1963 by what was then Harper & Row Books, no one predicted how it would take the world of children’s literature by storm. Adults were puzzled as their children, once reluctant readers, dragged them to the library over and over again to read this story, one that was unlike any other at the time. Within the realm of children’s books, a space previously marked by the conservative, didactic messaging of

Dick and Jane stories, Sendak was a breath of fresh air, having written a child protagonist who was as messy and loud and chaotic as he longed to be.

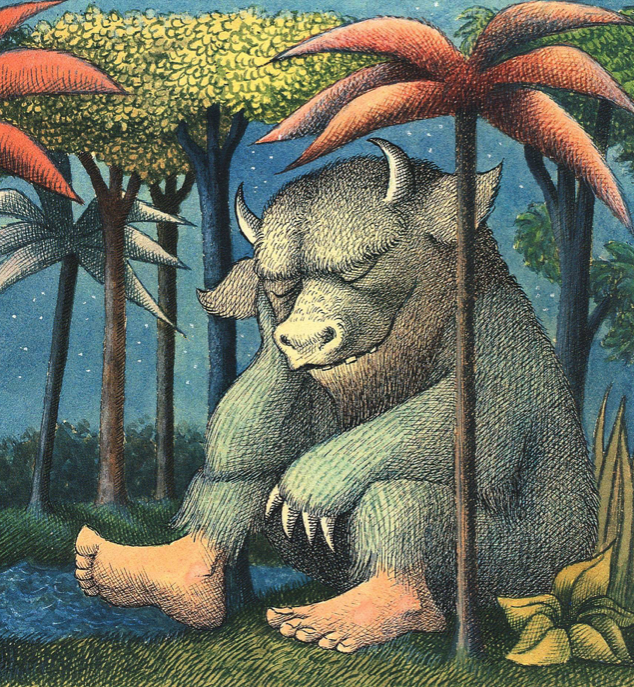

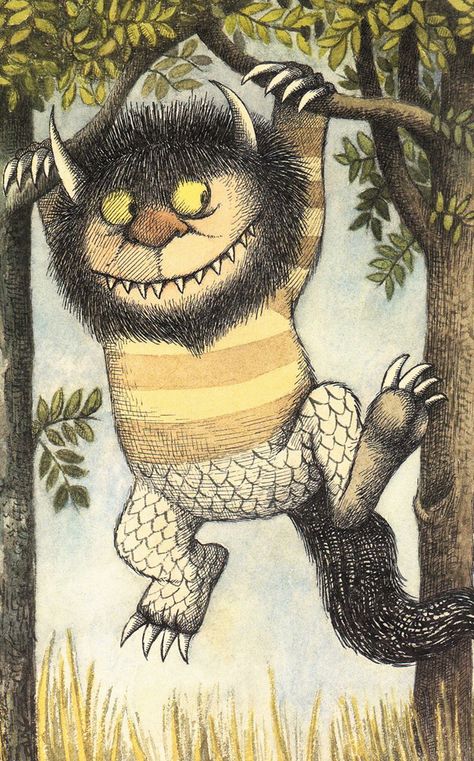

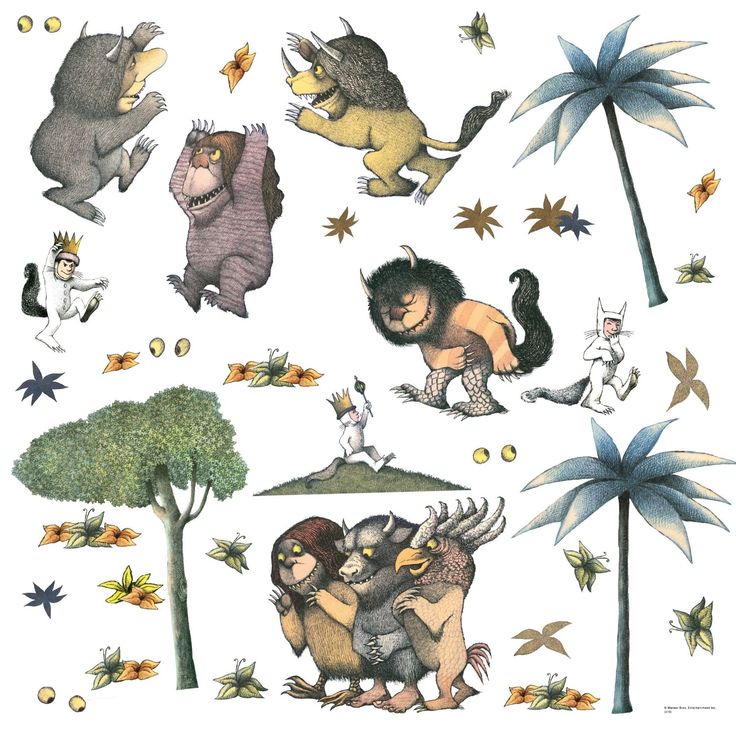

Maurice Sendak broke new literary and artistic ground by turning to the darker realities of childhood, illustrating a blend of anger, frustration, and other complicated emotions among the monsters he painted. Rather than patronizing his young readers, painting an illusion of childhood “innocence,” he respected them by acknowledging the terrifying reality of what it meant to be a child, someone who existed on the margins of life, who possessed both intense vulnerability and incredible insight, unfiltered by adult biases. Sendak, along with literary innovator and legendary editor Ursula Nordstrom, created a book that would become emblematic of the richness and depth of children’s picture books. He explored his own past, and mined and reflected upon his own experiences as a queer, Jewish child learning to grow up in the world. Sendak was, himself, the real deal “wild thing.”

Born and raised in Brooklyn, New York to Jewish Polish immigrant parents, Sendak occupied an “outsider” status in multiple senses of the word. Whether it was a physical “outsidership,” gazing upon the world outside from his bedroom window while sequestered from illness as a child in his home, or an internal one as the descendent of immigrant Holocaust victims and a gay adolescent in an extremely heteronormative world, Sendak could never quite blend into 20th century America’s idea of “normal.”

Whether it was a physical “outsidership,” gazing upon the world outside from his bedroom window while sequestered from illness as a child in his home, or an internal one as the descendent of immigrant Holocaust victims and a gay adolescent in an extremely heteronormative world, Sendak could never quite blend into 20th century America’s idea of “normal.”

Sendak was, himself, the real deal ‘wild thing.’

While it is debatable how early Sendak became aware of his own queerness, he understood how his “difference” was perceived by others, saying in an interview, “You know what they all thought of me: sissy Maurice Sendak.” In addition to his attraction to men, Sendak’s natural early queer sensibilities—including his love for art and storytelling, as well as his physical departure from the Western athletic masculine ideal defined by Superman (whose Jewish immigrant/refugee origins have often been erased or “goy-washed” by American media)—created a sense of unease and “otherness” that carried into his work.

It should be noted that when it comes to fantasy and speculative fiction, queer readers and writers have always gravitated toward this medium. For instance, in an interview with Geeks OUT, author and illustrator, Ethan M. Aldridge (Estranged series) states:

There are so many themes and tropes in fantasy that resonate with the queer experience; outsiders finding their way through a strange world, transformations, hidden identities. People find impossible loves, change form and gender, escape from inescapable isolation into a world wider and more strange than they ever imagined. Fantasy is all about a life and a world outside of what we are told is possible, and I think that sense is something that speaks to a lot of queer people. We grew up with those feelings in us, so we gravitated to the stories that told us those feelings meant something true and important and beautiful. From changelings to voiceless mermaids to love-lorn princesses locked away in remote towers, queer people have been using fantasy as a way to express feelings of queerness for a long time.

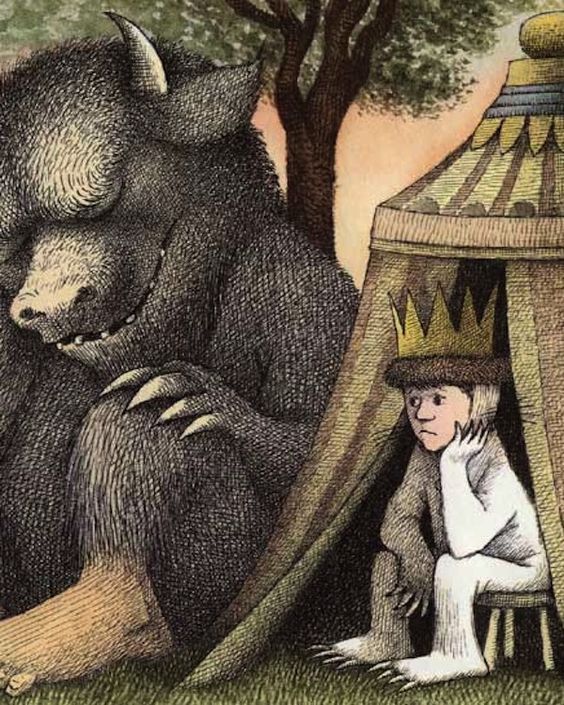

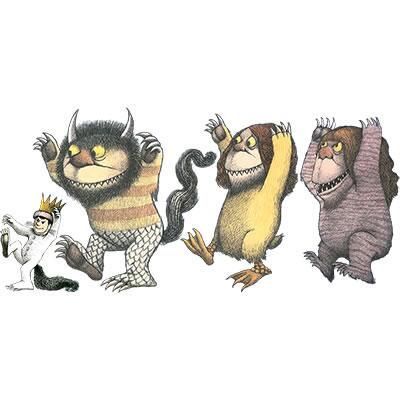

While Max isn’t explicitly queer in the sense of sexuality or gender exploration, his “queerness” may refer to the older 19th century definition of queer as something “strange” or “peculiar.” As we see in Where the Wild Things Are, Max is considered a stranger to his own family. He is “cast out,” banished to his room for excessive and wild behavior. And like Dorothy Gale from The Wizard of Oz (another icon of children’s media that maintains a significant queer following), Max finds himself in a wonderland that simultaneously terrifies and welcomes. It is in the land of the Wild Things where Max finds the space to experiment, identify, and play. He learns how to be a new version of himself, braver and louder than he was ever allowed to be at “home,” while finding a new sense of self and chosen family—an also inherently queer theme— along the way.

It is in the land of the Wild Things where Max finds the space to experiment, identify, and play.

And speaking of family, like Sendak’s queerness, and his own familial roots, his Jewishness is something also inherently inescapable from his work. As an artist, Sendak frequently turned to his family for inspiration, even modeling the faces of his characters after the ancestors he found in family photo albums. This is seen in his illustrations for Zlateh the Goat and Other Stories, a collection of stories by the Jewish writer Isaac Bashevis Singer.

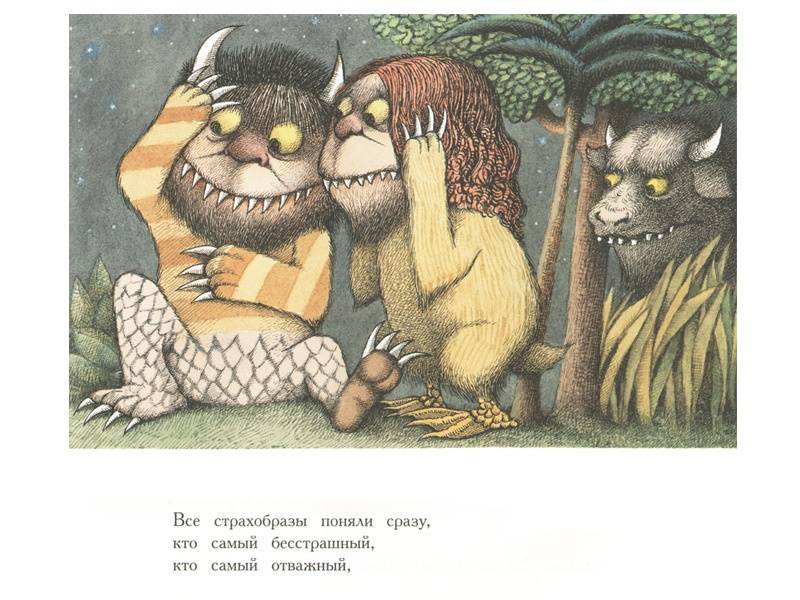

Yet the inspiration did not stop at transcribing from photos. Sendak also drew symbolically from his family, modeling his Wild Things after his Old World Yiddishist immigrant relatives.

In the piece titled “Moby Dick, Creativity, and Other Wild Things,” Sendak describes a typical day with his family:

They were a huge bunch who would roughly snatch you up at any moment. They’d jabber loudly in a foreign tongue—kiss, pinch, maul, and hug you breathless, all in the name of love. Their dread faces loomed—flushed, jagged teeth flaring, eyes inflamed, and great nose hairs cascading, all oddly smelly and breathy, all dangerous, all growling, all relatives.

In writings such as this, readers can see an obvious connection between the creatures in Max’s story and the “Wild Things” in Maurice’s life, otherwise known as his relatives. If you’ve ever had a relative come up to you and say something along the lines of, “you’re so cute, I could just eat you up!” then you’ve encountered a very Sendakian line of thought, a familial love that is both overwhelming and consuming (sometimes even literally). Yet in early 20th century America, when the model of the emotionally bland nuclear family was aggressively showcased, and conservative assimilation meant purging many “ethnic” modes of family behavior and flavor, Sendak’s family’s vibrant Jewish distinctiveness was likely considered “non-normative.” Perhaps his relatives’ own aggressive mannerisms and affections could even be mistaken for monstrosity.

Golan Y. Moskowitz, literary scholar and author of Wild Visionary: Maurice Sendak in Queer Jewish Context, had this to write about Sendak’s family: “In their inability to express love without eliciting terror, the Wild Things, whom Sendak called ‘foreigners, lost in America, without a language,’ are also like queer people experiencing love and attraction in ‘wrong’ ways, according to a prejudiced society. ” In the context of xenophobia, antisemitism, and queerphobia, the different elements of Sendak’s life, the ones he himself regarded with both exasperation and deep love, were demonized, lending further weight to the sense of the “other” encountered in his stories.

” In the context of xenophobia, antisemitism, and queerphobia, the different elements of Sendak’s life, the ones he himself regarded with both exasperation and deep love, were demonized, lending further weight to the sense of the “other” encountered in his stories.

Within children’s literature, there’s often a legacy of depicting marginalized groups as monsters, symbolic liminality illustrating the emblematic “other.” A more obvious example of this can be seen within early fairy tales. In her piece “Can I Still Love the Antisemitic Fairy Tales That I Grew Up With?“, Jewish writer Aleksia Mira Silverman notes that many of the classic Grimm Brothers’ stories she grew up with and loved contain a hostile legacy, writing, “I struggle to reconcile how much I love Grimms’ fairy tales with their reliance on antisemitic tropes and the deadly impact they’ve had on Jewish communities throughout history.” Taking in the archetypical witch model within the illustrations of many children’s books and fairy tales, it’s easy to identify the antisemitic tropes taking center stage: the curved noses, the wild, frizzy hair, all of which are classically stereotyped features for Ashkenazic Jewish women.

Consuming these narratives in story after story, it’s no wonder how any child lacking fair skin, reading how their other features, like hair and noses, are described as ugly and evil, might internalize feeling like a monster. Yet there are those like Sendak who have seen this wildness, this “monstrosity,” and turn towards it with compassion and empathy. Unlike most fairy tale stories, where those marked as “other” or different are considered the villains, in Sendak’s stories those marked as the “other” are capable of both loving and receiving love in return. As we see in Where the Wild Things Are, the Wild Things don’t hurt Max, but instead play with him, joining him in a “wild rumpus.” And toward the end of the book, when Max feels ready to return home, his mother, originally presented as the most antagonistic force in the story, is shown to contain multitudes. She leaves a warm meal waiting for her child. And what’s more Jewish than food as a symbol of our love?

And what’s more Jewish than food as a symbol of our love?

In their book, Craft in the Real World: Rethinking Fiction Writing and Workshopping, writer Matthew Salesses writes: “To be a writer is to wield and to be wielded by culture. There is no story separate from that. To better understand one’s culture and audience is to better understand how to write.” Salesses believes the act of writing is never created in an apolitical or neutral vacuum. It is never fully separate from the elements that affect our own lives and stories. While this does not mean every writer’s story is based on their life story, i.e., sometimes a story about talking cars is just about a story about talking cars, it would be limiting to say there is never any influence at all.

There is no story separate from that. To better understand one’s culture and audience is to better understand how to write.” Salesses believes the act of writing is never created in an apolitical or neutral vacuum. It is never fully separate from the elements that affect our own lives and stories. While this does not mean every writer’s story is based on their life story, i.e., sometimes a story about talking cars is just about a story about talking cars, it would be limiting to say there is never any influence at all.

Growing up, one of the most useful lessons I learned came from a teacher who suggested that when reading, one should always turn to the back of the book and read the author’s page first. I was initially puzzled by this, wondering how knowing about the author in real life had anything to do with reading their work. Yet over the years, as I learned more about myself as a writer, I also started to learn to read between the lines. By doing so, I saw the richness of the stories I was reading, and the richness of where these stories came from. Sendak’s complicated and intersecting identities are intimately tied to his work as an artist. At the heart of Where the Wild Things Are lies Sendak’s heart: a boy like Max who was pulled between worlds, between his old Yiddishist Jewish immigrant heritage and the hostile, homophobic American landscape he was navigating. He embraced those who were considered “monsters” by the outside world, and in them he found his chosen family. He taught an entire generation that “wildness” need not be tamed by the artificial boundaries of society—that children like Max could simply be themselves, wild hearts and all.

Sendak’s complicated and intersecting identities are intimately tied to his work as an artist. At the heart of Where the Wild Things Are lies Sendak’s heart: a boy like Max who was pulled between worlds, between his old Yiddishist Jewish immigrant heritage and the hostile, homophobic American landscape he was navigating. He embraced those who were considered “monsters” by the outside world, and in them he found his chosen family. He taught an entire generation that “wildness” need not be tamed by the artificial boundaries of society—that children like Max could simply be themselves, wild hearts and all.

Take a break from the news

We publish your favorite authors—even the ones you haven't read yet. Get new fiction, essays, and poetry delivered to your inbox.

About the Author

Michele Kirichanskaya is a freelance journalist and writer from Brooklyn, New York. A student of the New School MFA Program and Hunter College, when she is not writing, she is reading, watching an absurd amount of cartoons, and creating content for platforms like GeeksOUT, Catapult, Bitch Media, Salon, The Mary Sue, ComicsVerse, and more. Her work can be found here and on Twitter @MicheleKiricha1.

Her work can be found here and on Twitter @MicheleKiricha1.

The story of the ballad Where the Wild Roses Grow

True connoisseurs of alternative music frown with displeasure every time a rock musician enters the same stage with someone from the "pop". And even if he records a song with such a performer, a stream of righteous anger falls upon him, accusations of betraying ideals, and so on.

At the same time, no one remembers that rock arose as a protest against everything that fetters a person, including such conventions.

The history of creation and the meaning of the song Where the Wild Roses Grow

Australian rocker Nick Cave is not bothered by such nonsense. Despite his sinister image, sullen manner of performance and gloomy lyrics, he did not consider it shameful to invite the famous pop diva Kylie Minogue to sing Where the Wild Roses Grow with him. Even more surprising is that Kylie dared to accept the offer, although the producer called the idea crazy.

Even more surprising is that Kylie dared to accept the offer, although the producer called the idea crazy.

But neither Cave nor Minogue failed. Where the Wild Roses Grow turned out to be a very beautiful song, which is still a success with listeners in many countries.

Nick said that he wrote it under the influence of the folk ballad Rose Connolly, also known as Down in the Willow Garden.

Cave also admitted that even while working on the song he was going to invite Kylie to sing it as a duet. He drew attention to the singer when he saw the Better the Devil You Know video, but he always thought that "it would be better if she performed something sad and slow. "

"

The song Where the Wild Roses Grow tells about a man who fell in love with a young and beautiful girl and killed her so as not to see her beauty fade. Naturally, Nick sings on behalf of a maniac, and Kylie performs the part of the victim (that is, her ghost).

Release and Achievements

They first performed Where the Wild Roses Grows in August 1995 during a performance in Ireland. A year later, the song was released on Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds' album "Murder Ballads" (the most successful in the band's history). It was included in NME magazine's "100 Best Songs of the 1990s" list.

Video clip Where the Wild Roses Grows

A spectacular video was shot for the song, directed by Rocky Schenk. If you haven't seen it, be sure to check it out.

Interesting facts

- Nick Cave and Kylie Minogue only met while working on the video.

- On set, Kylie is said to have been covered in champagne that Nick filled the pool with.

- Nick was nominated for an MTV award, but he publicly turned it down, saying that his band's music is unique, so they simply have no one to compete with.

- Murder Ballads records the deaths of over sixty people.

- At the band's concerts, Blix's guitarist Bargeld sings Kylie's part, defiantly reading the text from a piece of paper. Nick Cave finds his performance to be "really creepy".

Where The Wild Roses Grow – Nick Cave

Chorus:

They call me the Wild Rose

But my name was Elisa Day the first day I saw her I knew she was the one

She stared in my eyes and smiled

For her lips were the color of the roses

That grew down the river, all bloody and wild

When he knocked on my door and entered the room

My trembling subsided in his sure embrace

He would be my first man, and with a careful hand

He wiped at the tears that ran down my face

On the second day I brought her a flower

She was more beautiful than any woman I've seen

I said , “Do you know, where the wild roses grow

So sweet and scarlet and free?”

On the second day he came with a single red rose

He said “Give me your loss and your sorrow?”

I nodded my head, as I lay on the bed

If I show you the roses will you follow alone 9

On the third day he took me to the river

He showed me the roses and we kissed

And the last thing I heard was a muttered word

As he knelt above me with a rock in his fist

On the last day I took her where the wild roses grow

She lay on the bank, the wind light as a thief

And I kissed her goodbye, said “All beauty must die”

And I knelt down and planted a rose between her teeth

Translation songs Where the Wild Roses Grows – Nick Cave

Chorus:

They call me Wild Rose

But my name was Eliza Day

I don't know why they call me that

Cause my name was Eliza Day

From the day I first saw her I knew that there is no other like it,

She gazed into my eyes and smiled

Her lips were the color of roses,

That grow down the river, blood red and wild

When he knocked on the door and entered the room,

My trembling subsided in his confident embrace

He was destined to be my first man, and a gentle hand

He wiped away the tears that were running down my face

On the second day I brought her a flower

She was more beautiful than all the women I saw

And I said, “You know where the wild roses grow,

free?"

On the second day he came with one wild rose,

He asked: “Will you give me your loss and sorrow?”

I nodded as I lay down on the bed

"If I show you roses, will you follow me?"

On the third day he took me to the river

He showed me roses and we kissed

The last thing I heard were unclear words,

When he knelt over me with a stone in his hand

On the last day, I took her to where wild roses grow,

She lay on the shore, and a barely noticeable breeze blew

Kissing her goodbye, I said, "All beauty must die"

Leaned in and put a rose between her teeth

Quote about the song

Where the Wild Roses Grow was written with Kylie in mind.

Nick Cave

about the "golden crutch", romance, wild teams and a million teeth - Amurskaya Pravda

SocietyThe youngest and northernmost city of the Amur region, Tynda, this year celebrates the anniversary of the most popular construction site in the USSR. 45 years have passed since the construction of the Baikal-Amur Mainline began in the harsh taiga. Railway troops cut down forests, blew up hills, and builders followed in armored trains, laying tracks and creating new stations in permafrost areas. BAM built the entire Soviet Union. Surprisingly, Komsomol members dreamed of the taiga wilderness to live in trailers without heating and with imported water, to wear earflaps at -50. Many builders, hardened by BAM, remained our countrymen. On a memorable date, Amurskaya Pravda collected the memories of the pioneers of the legendary road.

His name is a legend. The same foreman Ivan Varshavsky, who drove in the "golden crutch" at the BAM dock at the Balbukhta junction. The 81-year-old Ivan Nikolaevich still greets the next anniversary of the great construction project with trepidation. Half a lifetime ago, he demanded a ticket to BAM. And to this day he lives in Tynda.

The same foreman Ivan Varshavsky, who drove in the "golden crutch" at the BAM dock at the Balbukhta junction. The 81-year-old Ivan Nikolaevich still greets the next anniversary of the great construction project with trepidation. Half a lifetime ago, he demanded a ticket to BAM. And to this day he lives in Tynda.

- I was born in the Odessa region. He graduated from the courses of brigadiers - track fitters in Moldova, then the Odessa Railway College. From 1960 to 1970 he worked at the Moldavian branch of the road. At 19The construction of the BAM began in 1972. And I went to the road Abakan - Taishet, for reconnaissance, - Ivan Nikolaevich recalls.

In those years, many romantics dreamed of investing their work in an ambitious project. In April 1974, the XVII Congress of the All-Union Leninist Communist Youth Union was held, where BAM was declared a shock construction site, detachments of Komsomol members from all over the USSR went there.

In May, patriotic Soviet youth made a stop in Taishet, and Ivan Varshavsky became an eyewitness to their rally. “I envied them. The city committee of the party did not let me go to BAM, because I was the secretary of the party organization, I did things well, ”the brigadier shares. Then Ivan Nikolaevich went to the trick.

“I envied them. The city committee of the party did not let me go to BAM, because I was the secretary of the party organization, I did things well, ”the brigadier shares. Then Ivan Nikolaevich went to the trick.

“We worked with enthusiasm! For myself and for that guy! In the timesheet, you set a working day of 8 hours, and you work for 12. Sometimes even 24 hours was not enough! Ivan Varshavsky recalls.

- There was an instruction from the Central Committee of the party that old cadres, experienced as mentors, were needed at BAM. I referred to it. And they had nothing to do, he smiles.

36-year-old specialist gathered his wife, two children and moved from comfortable conditions to the taiga wilderness. “People lived in tents, wagons. The brigades were quickly thrown into the construction of temporary huts. 2-3 days - and the hostel is ready. But my family willingly moved - where the needle is, the thread is there, ”the builder continues his story. The first winter at BAM seemed especially fierce.

The famous Tynda "barrels" in which the BAM builders lived.

- The cold was over 50, the ears were wrapped. You wrap the muzzles of the children with a scarf, carry them in your arms - some to kindergarten, some to school. Frost squeezes tears! Ivan Nikolaevich laughs.

In exchange for a room in a small family, Varshavsky reluctantly agreed to get a job as the head of the housing and communal organization, and his wife became the commandant of the hostels. Having launched the boiler house after the accident, when the utility pipes stood up from the cold, Ivan Nikolaevich still fled to the railway. “While the chief and the chief engineer were absent somewhere, the deputy for personnel signed my application. Then this deputy received. But I said: "I'm a traveler, I'm a specialist." And just our SMP took over the baton for laying the track at the Belenkaya station, ”Varshavsky narrates, as on New Year’s Eve 19On the 74th he received the coveted position of brigadier.

- Led a team of seven people. My group was called the "wild brigade" because I had all the professionals, - the BAM builder is proud.

"Wild Brigade" took on any work: participated not only in laying the track - loaded materials, built bypass bridges and shield houses. The team was moving north, developing new stations at Maly BAM. In the 80th, an experienced foreman was transferred to the main course. “The family remained in Tynda, and I was all on the road - forward and forward, through rivers, passes, gorges. Sometimes I didn’t see my relatives for two or three months. You will arrive for 2-3 days - and there is no more time, ”Ivan Varshavsky throws up his hands.

- Landing forces were thrown forward: mechanized columns, explosives, bridgemen. They cut down the forest, prepared the earthwork. And I had an armored train and people who did the main laying,” he says.

September 29, 1984 at 10:00 and 10 minutes Moscow time, two brigades - Ivan Varshavsky and Alexander Bondar - met at the Balbukhta junction, where they laid the last "golden link" that closed the BAM. A day to which ten years went and which Ivan Nikolayevich remembered for the rest of his life.

A day to which ten years went and which Ivan Nikolayevich remembered for the rest of his life.

- I close my eyes - and everything is in the style. I wake up and my hands are trembling. We have experienced many cases when everything was on the verge of collapse. Thank God, I stopped dreaming about this track-laying crocodile. Before that, BAM had ingrained itself into my blood, into my character,” Ivan Nikolayevich sighs.

After the “golden docking”, Ivan Varshavsky was summoned to Ostankino, and he simply told from television screens that he “worked like everyone else.” And upon his return from Moscow, on the stage of the city House of Culture, the Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU Vladimir Dolgikh presented the famous foreman with the star of the Hero of Socialist Labor.

- Jitters! I didn't believe myself! How could I know?! - and now his breath breaks from the exciting memories.

In October 1984 through traffic was opened along the Baikal-Amur Mainline. The famous railway worker was thrown into the electrification of the Trans-Baikal Railway and the Trans-Siberian. “For 10 years, we have covered the entire Amur region and half of the Chita region. I was already the deputy of the general construction and assembly train. Then they were engaged in the electrification of the Bikin - Ussuriysk road, ”Ivan Nikolayevich talks about labor exploits. Many of the first builders, retiring, left the harsh edge. But the foreman Varshavsky refused, even when offered an apartment in St. Petersburg, in a house on the Obvodny Canal embankment. He sincerely believes that, having left BAM, he will die.

The famous railway worker was thrown into the electrification of the Trans-Baikal Railway and the Trans-Siberian. “For 10 years, we have covered the entire Amur region and half of the Chita region. I was already the deputy of the general construction and assembly train. Then they were engaged in the electrification of the Bikin - Ussuriysk road, ”Ivan Nikolayevich talks about labor exploits. Many of the first builders, retiring, left the harsh edge. But the foreman Varshavsky refused, even when offered an apartment in St. Petersburg, in a house on the Obvodny Canal embankment. He sincerely believes that, having left BAM, he will die.

- When I worked on the Odessa-Kishinev road, I suffered from tonsillitis: on the tracks +45, and I drink water +30. The surgeon told me: "Leave!" I arrived at BAM. I drank ice-cold water from the springs, swam. Never got sick in 45 years. I'm better here. I have acclimatized. People who worked here a lot, and then left for a year or two - and died, - Ivan Nikolayevich explains.

Armored train with disco, cinema and gym

Varshavsky's armored train was a dormitory on wheels. The builders lived in compartment cars for two people. The group had its own cleaners, cooks, stokers. “There was a gym car, movies were played, a disco was held once a month, as expected, with light music. Bachelors invited girls from the stations. Champagne, cognac drank. But everything was carried out culturally, it was recorded through the police. My guys were vigilantes and kept order, ”notes Ivan Nikolayevich. Whole families lived in the working train.

- There were women, not many, but there were. And even with kids. The husband called his wife, we accepted - you have to wash, cook, clean, - explains the foreman.

Who disrupted the construction of BAM

Ivan Varshavsky on the right. Photo: Gudok

- There were many different cases. One day the boss calls me, says: “Send the bridge to take over the Small BAM. Bridgemen hand over by March 8 necessarily - a gift to women. They accepted and signed the documents. The next day we will return, the tracklayer has been started, but there is no bridge span! We look under the flight, and there the wardrobe and mirrors are broken into chips, - Varshavsky recalls. - It turned out that the railway troops were going here. They lived in trailers, and then they gave the commander an apartment in Tynda. And he also wanted to make a gift to his wife by March 8! When they were driving in one direction across the ice, there was no bridge yet. And in the opposite direction they did not notice the new building. They didn’t pass the dimensions, they hooked the span with the visor of KrAZ, pulled it off and fled!

Bridgemen hand over by March 8 necessarily - a gift to women. They accepted and signed the documents. The next day we will return, the tracklayer has been started, but there is no bridge span! We look under the flight, and there the wardrobe and mirrors are broken into chips, - Varshavsky recalls. - It turned out that the railway troops were going here. They lived in trailers, and then they gave the commander an apartment in Tynda. And he also wanted to make a gift to his wife by March 8! When they were driving in one direction across the ice, there was no bridge yet. And in the opposite direction they did not notice the new building. They didn’t pass the dimensions, they hooked the span with the visor of KrAZ, pulled it off and fled!

At the "golden docking" bonfires were lit and wept

Famous foremen Varshavsky and Bondar at the docking of the "golden link". Photo: nashatynda.ru

- When there was a docking at Balbukhta, indeed, people cried with happiness. The people have gathered! It was very cold, it was snowing. Many were waiting for a significant moment in the cars. And those who came just like that, without tents, warmed themselves around the fires all night! Representatives from all the Union republics arrived, all the top authorities, the entire Politburo. The path has already been laid. But we went back, painted two links with gold. Bondar's brigade removed one link, mine removed another. They parted, and then went towards each other. This moment was captured in the film,” recalls Ivan Varshavsky.

The people have gathered! It was very cold, it was snowing. Many were waiting for a significant moment in the cars. And those who came just like that, without tents, warmed themselves around the fires all night! Representatives from all the Union republics arrived, all the top authorities, the entire Politburo. The path has already been laid. But we went back, painted two links with gold. Bondar's brigade removed one link, mine removed another. They parted, and then went towards each other. This moment was captured in the film,” recalls Ivan Varshavsky.

During the celebration, Ivan Varshavsky "lost" his helmet, which was later found in the BAM History Museum. It is kept there to this day.

- When they docked, I took out a link sewn with a shawl, and in it champagne, vodka, sweets, chocolate. Lots of people, not enough glasses. I jumped on this link, take off my helmet, made “Northern Lights” in it (a cocktail of shamanic vodka. - Approx. AP.), took a sip a couple of times and passed it around. So my helmet is gone. It turned out that the museum. This is an ordinary helmet, only our entire route is marked on it, all the stations that we passed are marked. I had an artist in my team who painted these helmets.

So my helmet is gone. It turned out that the museum. This is an ordinary helmet, only our entire route is marked on it, all the stations that we passed are marked. I had an artist in my team who painted these helmets.

Gennady Lukich is also a pioneer of the BAM. But he did not build a road, but built local medicine. A graduate of the Vitebsk State Medical Institute in 1968, by distribution, he ended up on the Trans-Baikal Railway, in the Amur village of Taldan.

- Worked in Taldan for five years. There were 7.5 thousand people, 8.5 doctors, and I worked alone. I also had a maternity ward, surgical and emergency assistance, and night calls,” recalls Gennady Sychev.

When in 1973, by order of the head of ZabZhD, the Komsomol member was transferred to the capital of BAM, he was no longer afraid of anything. Gennady Lukich became the first doctor at the famous construction site. “Before BAM, there was only a district hospital with about 25 beds. The first doctor’s office was opened for me in SMM-544,” the doctor continues his story.

The first doctor’s office was opened for me in SMM-544,” the doctor continues his story.

- In 1980, there were many pregnant Komsomol women, immediately the rate of an obstetrician-gynecologist was introduced. Then venereal diseases appeared, a dermatovenereologist was brought from Moscow, - the Bamovsky doctor tells the truth with humor.

« The first pregnant women at BAM gave birth in the city of Skovorodino. We drove 200 kilometers off-road. In 1976 or 77, the Minister of Health of the RSFSR, Anatoly Potapov, came to us. He looked at our maternity hospital, and there is such a wreck! Now it's funny to say. He wanted to tear down the sign that said "Maternity Ward." And he himself is not tall - he jumped several times and did not get it! But after his arrival, the BAM members urgently built a maternity hospital, ”says Gennady Sychev with a smile.

The population of Tynda grew rapidly. In 1984, a hospital was finally opened in the capital of BAM - a luxurious seven-story building with 540 beds.

— Two powerful operating units worked in the surgical department. They even brought us by helicopter from Mogocha and from the city of Skovorodino. The road hospital was like a regional hospital: 180 doctors, specialized departments! The equipment was Swedish. The Minister of Communications presented us with a magnetic resonance tomograph - the first in the Far East. This is generally a fairy tale! The Khabarovsk regional hospital was surprised to see what kind of pictures they were, such unknown as aliens, - Gennady Lukich nostalgically.

The Directorate for the construction of the BAM and the Ministry of Railways spared no expense in the development of health resorts. New dispensaries were built along the highway, which carried out up to 1.5 million visits per year.

Gennady Sychev conducts a reception at the BAM.

- Only 1.5 million teeth were pulled out at BAM. And then I stopped counting,” the doctor says seriously.

Basically, the BAM builders were treated for colds and pneumonia, because they worked in harsh conditions. In second place were industrial and domestic injuries. “It got to the point that they were fools! They are driving across the bridge, one in a Magirus, the other in a KrAZ — someone will throw someone off the bridge. The youth!" Gennady Lukich waves his hand. Returning memories of the past years, the first doctor of BAM warmly recalls the shock work of his colleagues.

In second place were industrial and domestic injuries. “It got to the point that they were fools! They are driving across the bridge, one in a Magirus, the other in a KrAZ — someone will throw someone off the bridge. The youth!" Gennady Lukich waves his hand. Returning memories of the past years, the first doctor of BAM warmly recalls the shock work of his colleagues.

- Our mortality rate was the lowest in the region. Five people died per thousand admitted to our hospital, and 35 died in the territorial health care! the doctor clearly remembers.

BAM gave a second life. “Once the head of the department of the Ministry of Railways arrived. During the celebration, he had a heart attack. They called me, I said: "Urgent hospitalization." And he rolled a barrel at me! They insisted. Then he stayed with us for a month and a half, left alive,” Gennady Lukich smiles. There were also cases when doctors themselves found themselves on the verge of death.

Tynda received city status in November 1975. Before that, there was the village of Tyndinsky with a population of about 2 thousand people. By the 80s, according to unofficial data, about 80-100 thousand people lived in the city

Before that, there was the village of Tyndinsky with a population of about 2 thousand people. By the 80s, according to unofficial data, about 80-100 thousand people lived in the city

- When the "golden link" was being laid, the head doctor of Severomuysky (Severomuysky tunnel - the most difficult section of BAM. - Approx. AP) crashed on the road in an accident, he was drunk. The head of the medical and sanitary service, Viktor Shcherbakov, and I were taken by helicopter right from the siding. We helped the victims, and when we came back, we almost died. Caught in such a snowstorm, the helicopter began to throw like a bug. Shcherbakov and I hugged, we thought that we would stay in the gorge, - Gennady Sychev sighs.

Honorary railway worker and honorary resident of Tynda doctor of the highest category Gennady Sychev gave his soul to his vocation until 2017, until the railway hospital was closed. “120 doctors were fired, and our seven-story building still stands with broken windows,” he says bitterly. Now the doctor is 75. Whatever the memories of BAM, they are the best in his life.d

Now the doctor is 75. Whatever the memories of BAM, they are the best in his life.d

His road to the legendary construction site was long, his fate was amazing. Ivan Shestak, a native of the Minsk region and a graduate of a vocational school, worked everywhere. In northern Kazakhstan, he built cowsheds and pigsties, at the Bratsk hydroelectric station he was a carpenter and fitter. He also worked in the Irkutsk region at the Ust-Ilim hydroelectric power station. Romantic dreams brought him to BAM.

- I wanted to catch the beginning of construction and complete it to the end! - says Ivan Mikhailovich.

Ivan Shestak met XVII Congress of the Komsomol at the western section. “They offered to stay, but I said: “If you build BAM, then only in Tynda, in the central section. And he wrote a letter to the Amur regional committee of the CPSU. Then the bell rang: “We are waiting for you,” he shares his memories. Ivan Shestak bought tickets and flew away with one briefcase in hand, leaving a well-fed life in a comfortable apartment and a Volga car in Bratsk. The road to BAM was difficult, and the harsh land immediately met him unfriendly.

The road to BAM was difficult, and the harsh land immediately met him unfriendly.

We ate the Finnish Servelat. There was a longing for beer, they flew to Blagoveshchensk for it. Beer was brought, but it fermented and quickly fell into disrepair.

- They gave me a prefabricated house. I slept in a hat, in fur boots, in trousers. Electricity was obtained from diesel engines, it was not enough, everything was cut down. No heating. Imported water, in a barrel. In winter they were heated by potbelly stoves. Yes, it's the little things in life! What to remember them! Ivan Mikhailovich laughs. - Despite the difficult living conditions, the capital of BAM received generous supplies, and builders received good salaries. There was a lot of scarce goods, full of Japanese things. Fabrics, sheepskin coats, tape recorders. We ate Finnish servelat. There was a longing for beer, they flew to Blagoveshchensk for it. Beer was brought, but it fermented and quickly fell into disrepair.

Ivan Shestak did not come to BAM as a builder. While still in Bratsk, he began to write first for the city newspaper, and then was noted by his superiors and invited as a literary worker to the Bratskgesstroy publication Angara Lights. Ivan Mikhailovich became the first journalist of BAM. In 1974, he was appointed editor of the Baikal-Amur Mainline newspaper.

While still in Bratsk, he began to write first for the city newspaper, and then was noted by his superiors and invited as a literary worker to the Bratskgesstroy publication Angara Lights. Ivan Mikhailovich became the first journalist of BAM. In 1974, he was appointed editor of the Baikal-Amur Mainline newspaper.

- My first edition - a chair in the corridor of the BAM construction management. He wrote articles by hand, the employees of the department helped to type, then they sent them to the Skryavinsky printing house. Four bands were made until four in the morning, - Ivan Mikhailovich shares.

Three years later, by a resolution of the Central Committee of the CPSU, a large editorial office of the BAM newspaper was opened with a material and technical base and staff. “We received a trailer: one half of it is the editorial office, the other is housing for employees,” the journalist says. Ivan Shestak traveled the entire highway in an UAZ. Then no one cared about off-road, and it was simply a shame to ask for comfort.

In 1996, the newspaper "BAM" was liquidated along with the enterprise in which the litrab served. However, Ivan Shestak continued the chronicle of BAM in his works. His documentary books about the great Komsomol construction project were published: “BAM. Kilometers of the epoch” and “BAM. Fraternization of the Possessed." To the 45th anniversary of highway 79-year-old Ivan Mikhailovich is preparing for the release of the third book - “BAM. Pouches of memory. Contemporaries could see two plays by Ivan Shestak on the stage - "Bypass" and "Margin of Safety". The scenario is based on real stories that took place on the famous road. The Amur and Chita theaters played Shestak on the stages of Lenkom and the Moscow Art Theater.