Write a story games

Finish The Story Game: How To Play + 15 Story Prompts

December 29, 2019

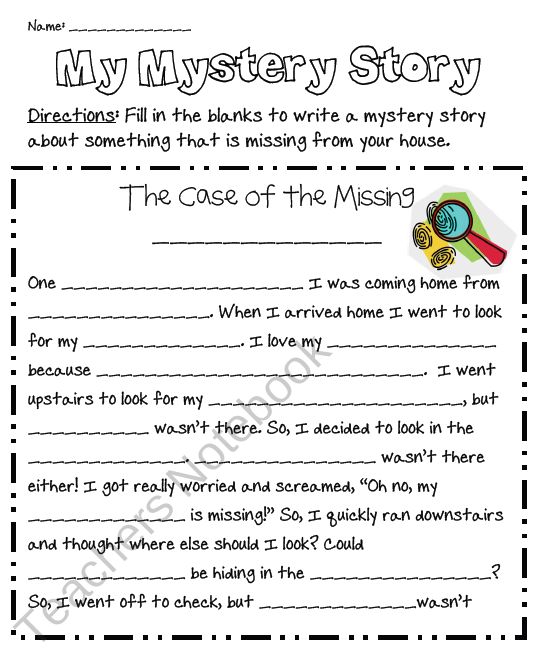

The Finish the story Game is a great way to encourage reluctant writers. Whether it’s down to laziness or just the lack of inspiration, these finish the story game prompts are a great source of inspiration. You can even take this fun activity one step further, by turning it into a multiplayer game for your students. When used in the classroom, this is a great writing game to improve your student’s creativity, teamwork, communication and writing skills. This makes it a fun activity for students in the 3rd, 4th and 5th grade.

Table of contents [Hide]

- Finish the Story Game: How To Play

- Finish the Story Game Rules & Tips

- Finish the Story Example Game

- Finish the Story Game Prompts & Ideas

- Finish the story: 3rd Grade Ideas

- Prompts for 4th Grade

- Prompts for 5th Grade

Looking for more fun game ideas? Check out or would you rather questions game.

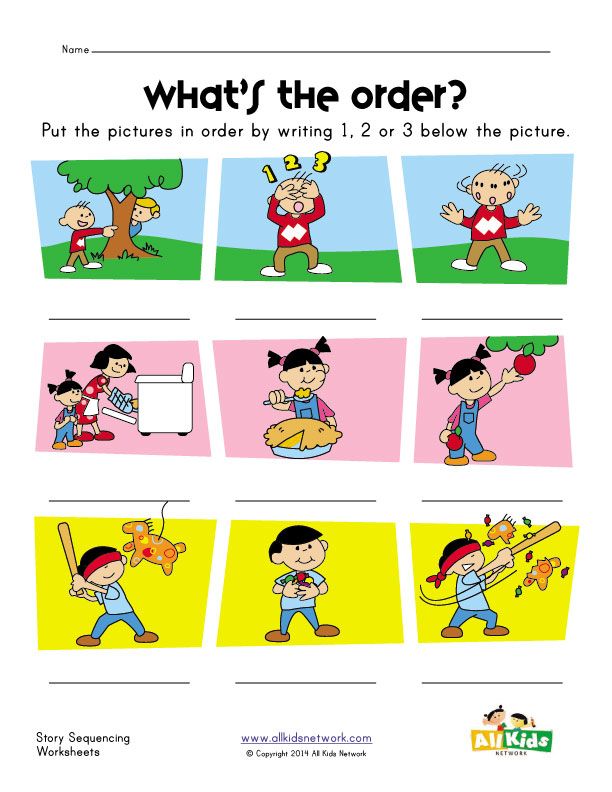

The Finish the story game is a fun group activity which develops each player’s storytelling skills. This game is best played between 2 to 8 players. The aim of the game is to create a complete story as a team. Going around in a circle each player will contribute one sentence to the story.

Here are some step-by-step instructions on how to play the game:

- Gather your players into a circle on the floor or around a table.

- Person one (this could be the teacher), starts off the story.

- Person two continues the story by saying the next sentence.

- Person three carries the story on and so on.

- Depending on the size of the group each player may have between 2 to 5 goes each.

- When the story is coming to an end, the last player says the ending sentence.

Finish the Story Game Rules & Tips

There are not many rules in this game, as the goal of this game is to expand your child’s imagination. However, there are some tips to make sure the game goes smoothly:

However, there are some tips to make sure the game goes smoothly:

- You need at least two players in the game

- Players must finish the previous sentence off and then start off a new sentence.

- The game can be as long as you like or as short as you like.

- Make sure you go around the circle, so each player has equal turns.

- You can appoint someone has the game moderator (i.e. the teacher). Their job could be to write the story down as the players are speaking to keep a record of it.

- The game moderator could also start the story off, as younger players may struggle to start.

- To make the game more challenging for older players, you might want to set a time limit or a limit on how many turns each player has.

- You could also make the game more challenging by introducing ‘special words’ that the players must use in their sentences.

- If players are a little shy or if you’re looking to improve writing skills, you can use a paper and pen in this game instead of saying the sentences out loud.

Feel free to experiment and customise the game in any way you like to suit your player’s abilities and writing level.

Finish the Story Example Game

Here’s an example of the finish the story game in practice, played between three players:

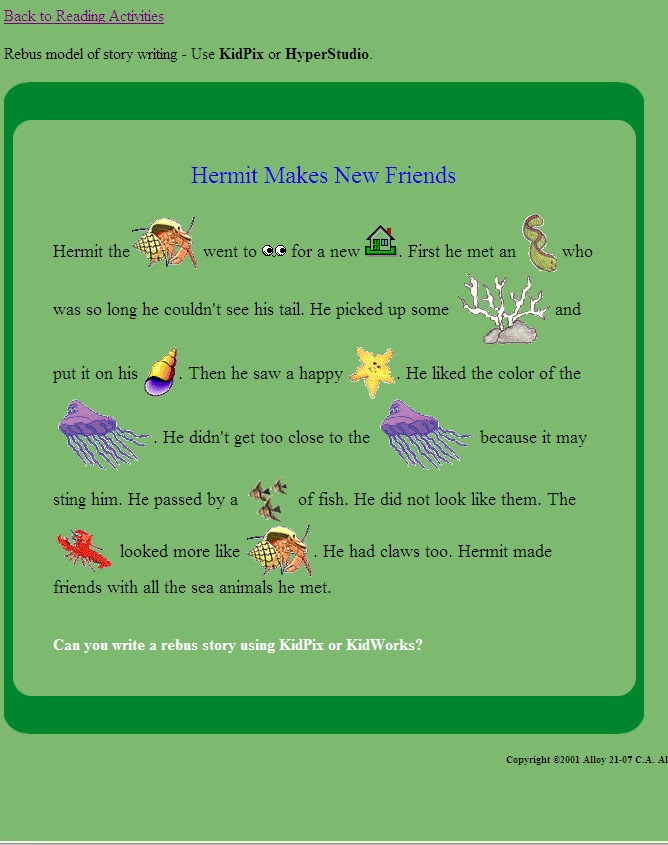

Player 1: As the rain poured, I walked to…

Player 2: School. Here I saw…

Player 3: An alien. He was…

Player 1: Dancing. So I asked him…

Player 2: What are you doing here? He replied…

Player 3: I’m here to eat you all! I ran…

Player 1: To my mom’s house. And shouted…

Player 2: Mom, where’s my lunch? She said…

Player 3: Your lunch is at school. So I walked…

Player 1: To school. And found…

Player 2: The alien had my lunch. However…

Player 3: That alien was my dad. And then…

Player 1: We laughed. My dad called me a…

Player 2: Silly snail. And he…

Player 3: hugged me. The end.

The end.

In this example game, each player had 5 turns and then finished their game. Remember you can finish your story in any amount of turns you like!

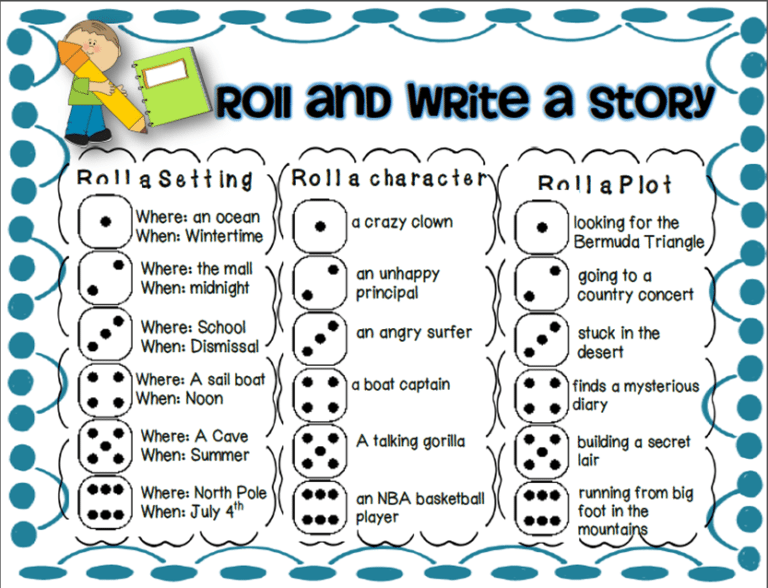

Finish the Story Game Prompts & IdeasNeed inspiration for your story? Here are some story starters and first-line prompts that you can use in the finish the story game or as stand-alone activities.

Finish the story: 3rd Grade Ideas

Finish the story ideas for 3rd-grade students:

- You hear a knock on the door and…

- You find a monster hiding in your cupboard and…

- Walking down the street, you find something…

- You receive a letter from…

- It’s your mom’s birthday today and you…

Prompts for 4th Grade

Finish the story ideas for 4th-grade students:

- On your way to school, something strange happens…

- You find one million dollars and…

- After getting stuck in the basement, you notice…

- You grow 10 inches every day and…

- You break the world record for…

Prompts for 5th Grade

Finish the story ideas for 5th-grade students:

- You time-travel to the year 3000 and…

- As you walk around town, you notice something strange…

- You invent something new and…

- After a bad day, you mistakenly create a cure for…

- While reading a book, you realise…

Looking for more story starters for the finish the story game? We recommend 101 story starters for little kids book (Amazon Affiliate link). This book contains a range of quick and easy story starters, which are great fun for the whole family:

This book contains a range of quick and easy story starters, which are great fun for the whole family:

For older children, you might be interested in the 101 story starters for kids book (Amazon Affiliate link). This book contains a brilliant range of quick and easy prompts to start your story. A great way to inspire the most reluctant storyteller out there:

Finish the story is a great game to play indoors or outdoors with family and friends. If you enjoyed playing this game, then why not try playing telephone Pictionary? Another great writing game to improve your child’s creativity and storytelling skills.

Marty

Marty the wizard is the master of Imagine Forest. When he's not reading a ton of books or writing some of his own tales, he loves to be surrounded by the magical creatures that live in Imagine Forest. While living in his tree house he has devoted his time to helping children around the world with their writing skills and creativity.

How To Write A Good Game Story

06 Aug How To Write A Good Game Story

Stories are an essential part of games. Surely there are games that don’t seem to have a story – but if you look closer, you see that they actually have a lot going for them.

Look at chess – chess doesn’t seem to have story. But if you look at it closely, it has characters, a world, progression, and a plot. There is a beginning, a middle, and an end. Even little pawns have an adventure and a transformation ahead. It’s all-out war, with conflict, death and victory. There are kings, queens, even horses. I say chess has a story, dammit.

Another example is Angry Birds. The story of Angry Birds is very short. Is it a story at all? Yes. The birds are on a mission. They hate the guts of these pigs. The Angry Birds story is one of thievery, sacrifice, parenthood, and ultimately revenge.

Stories are essential. In games there are heroes and villains. There is conflict, there is an imaginary world. We need to provide players with stories to give them context as to what they are doing.

We need to provide players with stories to give them context as to what they are doing.

With that in mind, here is my process for writing stories.

Step 1: Create the world

The story starts with the world. Geography is important, and it gives you a whole range of ideas to work with.

Some questions to ask yourself:

- Which continents does this world have?

- Which cities are there?

- Who lives here?

- Are there interesting landmarks?

- What could spawn conflict in this world?

- How did the nations come to their current form?

- Are there contested borders?

- Do people have enough resources? (food, water, wood etc)

- What technologies exist? (magic? teleportation?)

- Are there specific cultures?

- Is there free trade? Freedom of religion?

- What kinds of governments are there?

- Are people thriving or struggling in this place?

When you have the world set up, you can use it as a guideline for your characters’ backstories. The world will also be your point of reference for any future games you might be making in the same “universe”. Think hard about this step, and the rest will be much easier.

The world will also be your point of reference for any future games you might be making in the same “universe”. Think hard about this step, and the rest will be much easier.

(I generated the world of Momonga in Minecraft. I’m lazy.)

Step 2: Create the characters

The characters are the most important asset. A good character is someone the player can relate to. This means that he or she is “human” (even when they’re not). What makes someone “human”? They have flaws, a history, and somewhere deep down they have good intentions, no matter how messed up they are.

Characters are constructed. They have emotions, assumptions about the world, goals, likes and dislikes, enemies and friends. But most importantly, they have a history. This is where you start the construction.

Ask yourself the following questions:

- In what environment did they grow up? (Link this to the world design!)

- What were they like at age 5? At age 15? 30? 50?

- Do they have particular skills? (Use this for your game mechanics!)

- Were there life-changing events in their past?

- What is their personality like? How would they react in specific situations?

- What do they look like?

Note that we start in the past. The events and environments shape a character, and this in turn determines their personality. Then, and only then, do we define the looks.

The events and environments shape a character, and this in turn determines their personality. Then, and only then, do we define the looks.

(Note that I am guilty of defining the looks first. This is the easiest mistake to make.)

(Also note that if you are a man, it is very easy to forget to add women in your game. I am guilty of that too and I am ashamed of it. So please add women. And let them talk to each other.)

(if nothing else, your game characters make for some great business cards)

Step 3: Write the Grand Storyline

The grand storyline is the overarching conflict. You probably don’t want to reveal this in your game all at once, but with little bits. In the case of Momonga, we are stepping into all-out war, with the momongas at the center of it. But when you play the game, you only see a tiny little bit of that grand story. You see Momo’s village under attack, and you see that Panda rescues him. The true scope of the adventure is still hidden, and that gives us plenty of opportunity to raise the stakes and introduce new characters and obstacles.

The Grand Storyline should tie in with the World design. A great way is to ask these questions:

- Which nations / rulers are in conflict?

- What is the history of these nations?

- What is the role of the hero in the grand scheme of things?

- Is there an event (in the past or future) that shakes up the world?

- Which unknowns are revealed along the way?

- How are different characters plotting and clashing?

A beautiful story to take as an example is Game Of Thrones. The books and series alternate between lively “close-ups” of the main characters. You see them breathing and bleeding, and you get to know them. But every now and then, there are events that shape the course of history. These events should be mapped out in your Grand Storyline.

Step 4: Write the Game Story

When you have your world, your characters, and your Grand Story, it is time to take a tiny little piece of all that fluff. It is like framing a photo so that only a little bit is visible. You zoom in, and leave things out. Only tell the things that are important.

You zoom in, and leave things out. Only tell the things that are important.

A good checklist for writing the dialogue and in-game story:

- Is this moving the story forward?

- Is this revealing something of a character?

- Can a third-grader understand it?

It’s a simple checklist, but every line needs to follow these rules. And that can be tough to accomplish.

That third one may be a bit controversial. After all, not all games have to be kindergarten material. But please, pretty please, keep things simple. One line on screen at a time. No fancy words. No extravagant grammar. Simple punctuation. A guy from Popcap gave a great speach at GDC 2012, about the dialogue in Plants vs Zombies. He called it the “sophisticated caveman”. Write as though someone from the ice age would say it – except without the grunting and skullbashing.

This is not because your players are stupid. It is because they are impatient. And when you write lines that they can understand at a glance, they will pick up on the story even though they skip through the dialogue. They might even forgive you for throwing words at them.

They might even forgive you for throwing words at them.

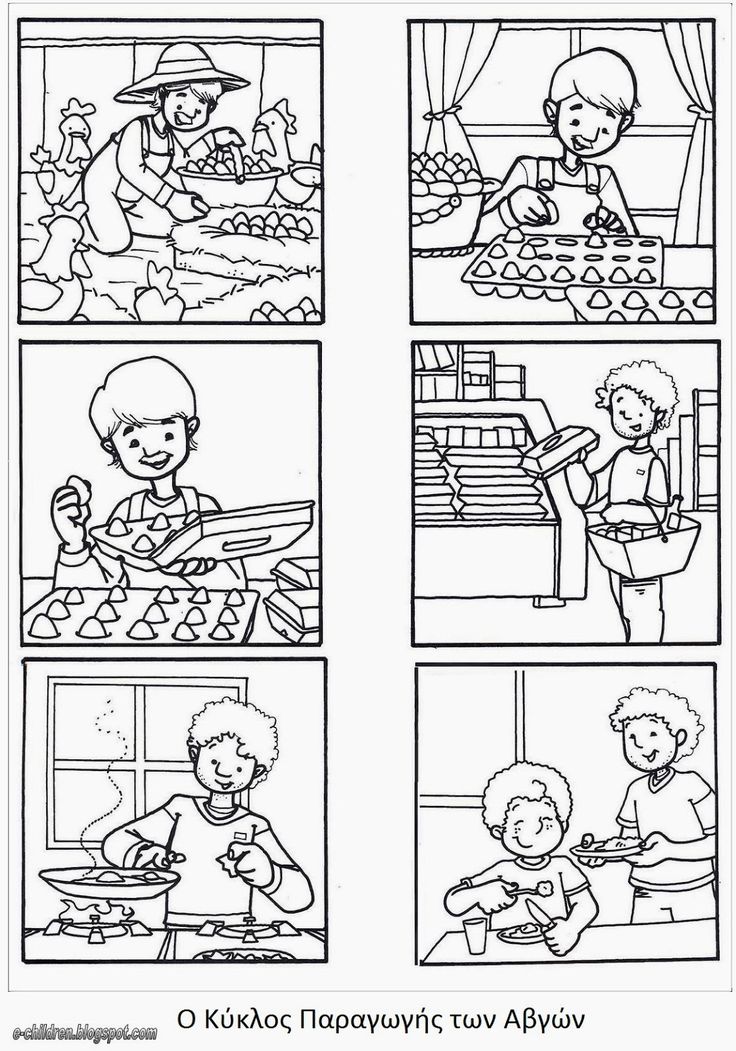

Step 5: Make the Storyboard

Yay, we get to draw now! The next step is to make the storyboard and show your teammates how it should all look on screen. There is not much to be said here, but storyboarding is an art in itself and it takes some skill to communicate cutscenes clearly.

Here is the storyboard for the introduction cutscene:

(read from left to right, and note that this is not finalized yet)

Step 6: Implement the story in the game

Great, you have a story! You have worked for weeks on end to get that done. But now it turns out, you are making a chess game! Ohnoes! Chess doesn’t have a story, right?

When implementing the storyline in your game, you are in charge. The trick is to mix and match the game mechanics with the narrative. And this can be tricky – especially when you are making a chess game (or in our case, a pinball game).

You have a lot of tools at your disposal. Here are a few:

Here are a few:

- Cutscenes – simply pause the gameplay and show some dialogue or pre-scripted action.

- Environment – Your levels tell a lot about the world and its history.

- Enemies – The bad guys tell a story by just being there.

- Allies – Your teammates can make scripted decisions that progress the story.

- Loading screens – give them something to read or look at while waiting.

- Artbooks, blogs, special content – it doesn’t have to be all in the game.

We mostly use cutscenes and the environment to tell the story.

This is what that looks like in Momonga Pinball Adventures:

(still work in progress, but it’s getting close)

Step 7: Iterate!

This is the step that allows me to be lazy. Because when you iterate, you can delay the hard work of writing a bit. But only a bit, mind you.

I don’t have time to write a 500 page world bible. So I don’t. I wing it. And that is how it should be when you’re making a game.

I like to start from the top: Make the world, characters, grand storyline. After “sketching” that out, I take the plunge all the way down to the dialogue. I want to see if the story fits with the game mechanics. And play around with it. But then it is time to take a step back and see if it all still works in the grand scheme of things.

When you do this, you will have to re-think certain characters, or even change big chunks of the world. This is no big deal, except if you reach a dead end street. And being cornered is the one thing to avoid. So you always need to think two steps ahead and have a plan ready for when things don’t turn out well.

With a bit of luck, you will have a good world with great characters. And with enough hard work, it will all fit together. And when it does, you might be having your hands on the next Lara Croft 😉

Your Turn

How about you? Do you have any tips to share? Leave them in the comments so we can all write better stories! And get filthy rich!

Cheers,

-Derk

PS: I will be at Gamescom next week, and the week after I am at Got Game Conference (giving a talk on Momonga on Tuesday) and Unity. So my posting schedule will be a bit different than usual.

So my posting schedule will be a bit different than usual.

How to create a story or plot for a game

As Seth Godin, author of inspiring best-selling marketing books (Purple Cow, All Marketers Are Liars, Permission Marketing), says, sell stories, not products. I think this advice should be applied in the field of games.

The story of a game is its plot. It is the story that keeps the player in suspense. A well-told story can even hide poor gameplay.

But how to come up with this story? Especially if the mechanics and graphics are already thought out.

After digging through a bunch of materials, I found a very interesting book by Gianni Rodari "Grammar of Fantasy". This book tells how to compose children's fairy tales. Methods are given on how to liberate your imagination. One of them is the binomial fantasy method:

“A story can only arise from the 'binomial fantasy'.

"Horse-dog", in essence, is not a "fantasy binomial". It's just a simple association within one species of animal. At the mention of these two quadrupeds, the imagination remains indifferent. This is a major third-type chord, and it does not promise anything enticing.

At the mention of these two quadrupeds, the imagination remains indifferent. This is a major third-type chord, and it does not promise anything enticing.

It is necessary that two words be separated by a certain distance, so that one is sufficiently alien to the other, so that their proximity is somehow unusual - only then the imagination will be forced to activate, striving to establish a relationship between the indicated words, to create a single, in this case fantastic, a whole in which both foreign elements could coexist. That's why it's good when the “fantasy binomial” is determined by chance”

I liked this idea and decided to try this method to create my story. But I made a small correction. Not all words were determined by chance, because I already had rough drafts for the game, such as gameplay and main characters.

I wrote down the words that I already have. They are like the initial condition in my problem.

But I decided to find the second part of the binomial randomly. And I found two ways to get random words.

And I found two ways to get random words.

1. I used the following word generation service: http://linorg.ru/randomword.php and wrote down all the words that I randomly generated.

Initial words : Cart, Stone, Treasure, Adventure, Caves.

Random words : Kicking, Absolutely, Approached, Needed, Shot

2. I used the matrix of ideas from Artemy Lebedev: http://www.artlebedev.ru/tools/matrix. In this version, I received only nouns. I wrote the initial words and got random nouns for them.

Cart - Protection,

Stone - Rainbow,

Treasure - Personality,

Adventure - Plain,

Caves - Weak.

I liked the second option better. I immediately started having ideas.

For example, "To protect the townspeople, our Seeker Hero took his old beat-up cart and went to the caves." This is where the story began. I immediately started asking myself questions. From what or whom does the townspeople protect? Why exactly him? Why did you go to the caves? Etc.

Before answering all the questions, I decided to form all sentences with these words. Here's what happened:

- To protect the townspeople, our Seeker Hero took his old battered cart and went to Caves

- The caves are said to hold a magical rainbow stone that can heal people. It is this stone that the Seeker Hero wants to find.

- When the Hero Seeker was a small child, his uncle told him extraordinary stories about treasure seekers. All these stories were about strong personalities who became heroes for the future Seeker.

- There are terrible beliefs about caves in the plains. They say that fabulous treasures are hidden there and all who tried to find them never returned. But those who have pure thoughts and souls have nothing to fear.

- Seeker Hero never considered himself a weakling, and he decided to volunteer for this disastrous task to descend into the caves. Yes, and there was no one else.

The story was already spinning in my head. It remains only to think of it a little. I started to combine the sequence of suggestions received. The most suitable option in my opinion: 3-5-4-2-1.

It remains only to think of it a little. I started to combine the sequence of suggestions received. The most suitable option in my opinion: 3-5-4-2-1.

Now the matter is small. Fill in missing gaps. What is the fatal mission? What threatens the citizens? What does this have to do with the magic stone in the cave?

After answering all the questions, this is the story I came up with:

“When I was little, my uncle used to tell me stories about treasure hunters. Their lives looked so exciting and interesting! And the seekers themselves were heroes! When I grew up, I became one of them. Everything turned out a little differently than in those fairy tales. Seekers are after money, they have no principles. Except don't kill. If it works out of course.

So, I am a Seeker. Yes, yes, I'm not proud of it. But come on, who doesn't love money?!

My story began in a small town. I've heard rumors of caves with an obscene amount of treasure! But, there was a small but. You can enter them, but you can’t get out ... Of course, I love money, but I love my life even more. Eh, if only I had known about this before, but... And as soon as I wanted to leave this unfortunate town, as who would have thought, a deadly disease descended on the city! And not just any disease! Damn them! And sent by the ruler of neighboring cities. Something they did not share, you know. And on the one hand, what's my business. Yes, but everyone who was in the city got sick. All!! And now my whole short life has already flashed before my eyes! Such is not justice.

You can enter them, but you can’t get out ... Of course, I love money, but I love my life even more. Eh, if only I had known about this before, but... And as soon as I wanted to leave this unfortunate town, as who would have thought, a deadly disease descended on the city! And not just any disease! Damn them! And sent by the ruler of neighboring cities. Something they did not share, you know. And on the one hand, what's my business. Yes, but everyone who was in the city got sick. All!! And now my whole short life has already flashed before my eyes! Such is not justice.

A meeting was organized in the city to decide how to be saved, because otherwise absolutely everyone who was in the city would die over time. Of course, they remembered the old beliefs about the fact that in the caves (yes, in those) there is a magic stone that heals all diseases and blah blah blah. Talk long and hard, to be honest, I don't like boring gatherings. Only suddenly it became very quiet at this meeting, and for some reason all these little people were looking intently at me! Then everything was like a fog. I woke up in a cave. Yes! Imagine, they decided that since I am a seeker, then I should get them this pebble !! They just forgot to ask me. That's the kind of people they are. And this is the beginning of my story0003

I woke up in a cave. Yes! Imagine, they decided that since I am a seeker, then I should get them this pebble !! They just forgot to ask me. That's the kind of people they are. And this is the beginning of my story0003

Undertale, Cradle, Her Story - Gambling

About the nomination: it's hard to write a good story, but even that's only half the battle. The most difficult thing is to tell this story in accessible ways and in such a way that nothing ultimately interferes with it.

No matter how beautiful the British hinterland is in Everybody's Gone to the Rapture , there are many complaints about this project as a story game, and they can easily be reduced to one thing: participating in those events yourself could be much more interesting than silently watching people you don't really care about.

Hotline Miami 2 falls into this category only because like makes you look at the events of the first part. It turns one of the bloodiest games of our time almost into an anti-war manifesto. Leaving no choice but to do evil and then poke your nose into the consequences is not the best way to shame, but the residue is still interesting.

Leaving no choice but to do evil and then poke your nose into the consequences is not the best way to shame, but the residue is still interesting.

The Beginner's Guide is ambiguous in every way. Some even, it turns out, thought that Davy Rieden stole his friend's games and began to sell them in the form of a "conceptual" project. Who Koda was and whether he really was is a question that seems to remain forever open, but the creator of The Stanley Parable certainly presented the search for the author's "I" from a curious point of view.

And finally SOMA . SOMA, unlike Hotline Miami 2, offers choices but doesn't show the consequences - and thus makes it even more overwhelming. After passing, it leaves you in thought, but the thoughts are not the same as usual. Not “what would have happened if I had acted differently?”, but “what have I done?”.

Don't be fooled. After all, you yourself know that you decided to load the saved game not because something has changed inside you, but simply to check whether it was possible to do otherwise.

Undertale knows better than you how you play games and uses it to fool you. Take the pixel art that makes it look like Undertale is so high-end for the Atari 2600. That's also a lie. A part of the game language that exists so that one day the work can go beyond its scope.

To make it clearer that there is "going beyond", imagine that you are reading a book without pictures - a strict book printed in Times New Roman font, fourteenth point size. But on one of the pages, the letter "G" is framed as a drop cap. As soon as you stop looking at her, she rises to her full height and breaks your nose. Here you notice that the paragraph was about Gregory, who breaks his nose when others lose their vigilance. Everything falls into place.

Undertale does something similar. She sets the rules so that she can break them one by one, constantly taking them by surprise. But she does it for a reason, not for kitsch sake, no! Or rather, not really. We will not dissemble: Toby Fox, the author of Undertale, often twists jokes for the sake of jokes and from time to time is clearly too addicted. But you don’t think about it when, after a couple of minutes, he hits the spot again, and a simple, in general, story begins to act on a completely different level.

But you don’t think about it when, after a couple of minutes, he hits the spot again, and a simple, in general, story begins to act on a completely different level.

Puzzles, the behavior of opponents in battle, even the interface - all this does not tear you out of the game, but illustrates and complements what is happening. There are almost no episodes in Undertale where what you are already used to happens. She mutates, shows resourcefulness, avoids routine as much as she can. And this is an amazing achievement for a game made by just one person - even though it would be an achievement for any games.

Undertale is remarkable in that it uses game tools to tell the story in the most unexpected and daring way. She may look like a frivolous indie vignette, and here it would be worth saying: "Do not let the appearance fool you." But the opposite is better: let mislead her, as everyone else did. And play.

For some reason, the adjective "pretentious" is usually used mostly in a negative way. Say, a work with a pretension is usually something abstruse and pretentious, but at the same time empty. Let's take it and turn everything upside down: Cradle is pretentious and that's good.

Ilya Tolmachev, project manager, told us that the idea for Cradle came to him in a dream. Dreams are fragmentary, they are woven from scattered patches of memory and processed by the imagination.

Cradle works according to the same logic. It has only two locations, but they are enough to unfold a stunningly voluminous and deep story, one might even say - the whole Universe. With the smallest means, the small studio Flying Cafe for Semianimals not only tells and shows, but makes you imagine. Without imagination, a miracle will not happen. You guess how everything is arranged here, collect a mosaic in your head from small pieces, process it with your imagination and see a dream - this is how Cradle begins to be perceived over time. And this dream is not one of those that are so easily forgotten.

And this dream is not one of those that are so easily forgotten.

You assemble the Universe yourself and actually participate in its creation. Your brain creates entire worlds every night, operating on its own logic. And this is one of those worlds.

The main thing is not to think what you are really doing in Her Story .

Okay, let's say you're actually wasting your time digging through the police video archive, trying to solve a case that's more than twenty years old and has no influence on the outcome. But what's the difference if it's so wondering do?

You comb through the archive for keywords, finding the suspect's important statements in different order, watch her behavior, and gradually come to your conclusion. What did the author of the game, Sam Barlow, do? Without any additional devices, he built an incredibly reliable simulator. Now your monitor is the monitor of a decommissioned police computer, your chair is a shabby office chair, on which several hundred uniformed butts have sat before you. Finishing touches: donuts, coffee, after hours. Full immersion!

Finishing touches: donuts, coffee, after hours. Full immersion!

But as you comb through the archive, you learn more and more, and the investigation of the crime gradually fades into the background. The answer to the question of how exactly the murder happened can be found quite quickly - but that's not the point. Using it as bait, the game forces us to uncover something bigger: not one event, but the whole story of the heroine's life. Her Story .

Sam Barlow achieved the seemingly impossible: he made videos of live actors (more precisely, one actress masterfully performing her role) become part of the gameplay; he made the narrative completely non-linear, allowing us to independently choose which records to watch next; he achieved the utmost involvement of the player, in fact, forcing them to analyze and improvise - after all, without another relevant request to the archive, getting the next piece of the puzzle will not work. And this is not to mention how rich the story itself is with all sorts of metaphors, clues, details: Her Story requires a lot from you, but attentiveness rewards a hundredfold.