Writing is fun

Is Writing Fun? | Writing Forward

Is writing always fun?

People have different reasons for writing. For some, it’s a hobby. For others, it’s a livelihood. For most, it’s a hobby they dream of turning into a livelihood.

It’s a worthwhile dream, and a lofty one too. But what does it take to get there? How much fun will you have, and just how much work must you do to turn your passion for writing into a full-time job?

And if you do manage to make a career out of creative writing, will it still be as fun as when it was just a hobby?

Having Fun with Creative Writing

Young and new writers often come to creative writing because they find it enjoyable. Many are avid readers, so inspired by their love of literature that they want to create it. Others are compelled to express themselves on the page or share their ideas or visions with readers.

Most of us have experienced sudden inspiration. You’re sitting there and a poem comes to you fully formed. It’s finished within minutes, and it just might be brilliant. It feels like the poem came to you from some source outside of yourself. It’s pure magic. It’s exciting. It’s fun.

When we’re being creative, and especially when we’re tapped into that magical kind of creativity, it’s an extremely pleasurable experience. From the instant we start writing until our work is completed, we’re on a wild ride, exciting but dangerous too. Because if we rely on having fun, we may start to believe the many myths about writing that are floating around.

When the Fun Stops

It’s not uncommon for novice writers who have experienced the magic of sudden inspiration to wait for it to strike again. It’s likely that it will strike again, eventually. But waiting for this type of inspiration to hit you is a bad habit. You’re fostering dependence on a rare event instead of cultivating your creativity and developing good work habits.

Many hobbyists only write as long as it’s enjoyable. When they hit a brick wall in their story or finish a rough draft, they discover that blasting through the wall or delving into edits is not quite as fun as creating that first draft.

This idea that creativity happens magically is just one of the many misconceptions that inexperienced writers believe about the craft. These misconceptions are dangerous because they are beliefs that direct writers away from their work. And sometimes, being creative is hard work indeed.

Get to Work

Like anything, if you want to succeed in creative writing, you’ve got to work at it. I’ve tried many creative endeavors over the years, and writing is one of the most challenging pursuits you can choose. It requires a vast skill set, intense determination, and a willingness to work hard. It also requires a good measure of creativity, and you need business skills too. Talent is just the icing on the cake, something you’re born with if you’re lucky.

That’s why a lot of writers keep their day jobs and have no intention of becoming full-time authors. They want to stick with the fun stuff, so writing remains a hobby — something they do for personal pleasure. And there’s nothing wrong with that.

But if you want to turn that hobby into a career, you need to be prepared to do the hard work that is required to succeed. That means writing when you don’t feel like it, finishing what you start, and doing the tedious work of editing. You know, stuff that isn’t necessarily fun.

One of the best things young and new writers can do is prepare themselves mentally and emotionally for the writing life, and it starts with understanding that while writing is fun at times, it’s also work. At times, the work is immensely difficult.

The good news is this: it’s totally worth it, because reaching your goals as a writer — whether it’s getting a poem published or finishing a novel, is worth every challenge and struggle that it takes to get there, whether it’s pushing yourself to write when you don’t feel like it, blasting through a creativity block, or working through countless tedious edits.

Is writing fun? Yes, sometimes it is fun. Other times, not so much. But have faith, because the fun always comes back around.

Do you write as a hobby or is your goal to turn it into a career? Are you willing to do the hard work or would you prefer to stick with the fun stuff? Share your thoughts by leaving a comment, and keep writing!

A Guide to Playfulness for Serious Writers

Writing is a lot of work, and there are definitely parts of the process that aren’t fun. But if writing has become a drudgery, if it’s become something you dread every day, then maybe it’s time for a little play to reinvigorate your love for writing. What if you were writing for fun?

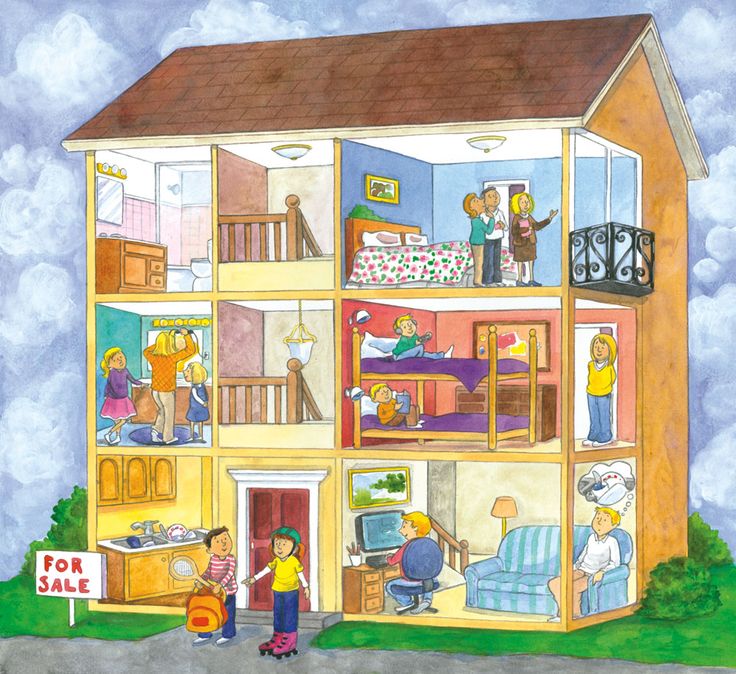

I’ve spent most of my teaching career with high school and college students, but I had the opportunity to work as an elementary librarian for a few years, running book and writing clubs and basically playing in the literary sandbox with kids. It was a blast.

The kids who came to my book and writing clubs embraced the experimental in their work, willing to play with words in a way I’d not seen in the majority of my teen and adult students. I remember a student who would read the same line or page in a book with multiple voices, each one adding a new line or slightly altering the message and tone until we couldn’t hear his voice anymore over our laughter.

I remember a student who would read the same line or page in a book with multiple voices, each one adding a new line or slightly altering the message and tone until we couldn’t hear his voice anymore over our laughter.

It was pure joy.

Joy: lost and found

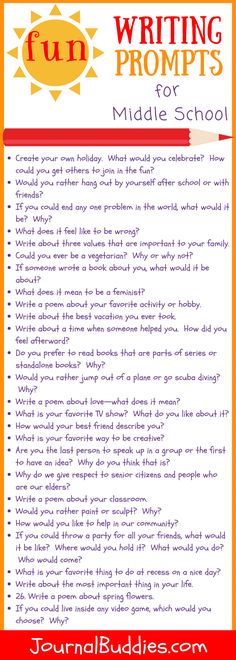

As I went back to my high school and college classrooms, I found that most of my students loathed writing. If I announced a writing project or exploration, it was met with groans. The questions that these writers asked included, “How long does it have to be?” and “Am I done?” Writing had become pure torture.

Somewhere along the way, someone made them feel like they weren’t writers. They stopped trusting their own creativity and voice.

As I began to unpack why, most reported that all the fun had been drained out of writing with uninteresting prompts and five-paragraph essays. They didn’t have time or the option to write about things that interested them. Too often we prioritize academic niche writing at the expense of every other form that we consume and enjoy daily.

My first goal is always the same: help them rediscover their voice and ability to play with language. Put another way, help them rediscover writing for fun. I gently nudge writers toward topics and forms they like, in hopes they would rekindle some of that childhood curiosity and creativity. We begin to see pages in notebooks filled where blank lines had once sat hopeless.

Invariably, I begin to hear conversations that include, “Listen to this!” and “OMG, I’ve never written this much before.”

A few students still eye me warily, sure I'm about to force them to turn their fun into something they’ll dread. Instead, we find the lines that sing, we find one thing to improve, and we keep going.

Volume and deliberate practice yield results. And the way to more volume? The way to keep going? Is to make the writing practice fun.

But what about (cough, cough)

serious writingThat’s fine and well, you might say, but what about the *serious writing*? I teach that too, but students need freedom in topics and form as much as possible. And I would argue that *serious writing,* like all good writing, is created from a place of fervency (some call it exigence)—the topic matters, and the form rises to meet the needs of the writer and the audience.

And I would argue that *serious writing,* like all good writing, is created from a place of fervency (some call it exigence)—the topic matters, and the form rises to meet the needs of the writer and the audience.

But don’t underestimate the power of play. We don’t outgrow it.

My college classes are finishing an argumentative writing course right now, and their culminating project asks them to engage a form creatively that uses the same skills we applied to formal academic writing: research, curation, analysis, and synthesis.

Some students are analyzing true crime podcasts. Others are building public service announcements. Some are writing fiction and others are honing creative skills like learning a complex piano piece and tracking development.

I’ve heard comments such as, “I hadn’t thought of this as writing!” and “I can’t believe I get to do this for school. I’m learning so much. Thank you!”

Turns out the best way to take your writing seriously is to play.

“

The best way to take your writing seriously is to play. Give yourself permission to have fun writing.

For adults: Meet your mentor, a kid

How do we do it, then? Is it really as simple as, “OK, today I’m going to play”?

For kids, it is—they don’t think so much about the rules and what sells and what’s expected. If you’ve ever played a game with a child who was improvising the day as she went along, you’ve experienced this.

For adults, I’ll wager we’re all sitting at our laptops trying to force ourselves into some childlike state, fingers poised over the keyboard. “Play, darn it! Write for fun!” Really, we need to start by letting our minds wander.

What games did you love as a kid? Make a list or describe a game the way you remember it. Then write a variation.

Add something absurd. Add an alliterative line. Smile as you write or type.

Take a snack break. Smell something near you and describe it to your dog.

Read something that makes you laugh. Read something that takes your breath away. Describe what happened or mimic the form.

Read something that takes your breath away. Describe what happened or mimic the form.

Don’t think about what you’re going to do with the writing that emerges. Just play. The experience is its own reward.

For kids: The Write Summer Camp 2020

Do you have a child age 7 to 14 whom you would love to see keep their writing joy and develop it this summer?

We’ve gathered a group of bestselling authors, professional writers, and award-winning teachers to create a fun, interactive, week-long writing experience.

Camp sessions are all held online, and we combine the right blend of writing instruction, encouraging feedback, and lots of writing fun for kids.

During your child’s Write Summer Camp experience, they’ll get to:

- Learn from professional writers

- Find and develop ideas for writing

- Write their own story, ready to share by the end of camp

- Practice revising their own work using feedback

- Build their creative muscles and writing confidence

We're inviting kids ages 7 to 14 to play with writing this summer. Sound like fun?

Sound like fun?

Learn more and apply »

Playtime

No matter your age, you can always rekindle the joy of play in your writing. Relax and give yourself permission to be silly. Let your curiosity and whimsy guide you.

Remember, the more you write for fun and enjoy the process, the more others will enjoy reading it!

When have you found joy in writing? What are your favorite ways to play in your writing? Share in the comments.

PRACTICE

Take fifteen minutes. Make a list of your favorite childhood games or describe a game the way you remember it.

Then write a variation. Add something absurd. Add an alliterative line. Smile as you write or type. Take a snack break. Smell something near you and describe it to your dog.

Alternately? Just sit on the floor and tinker with something for ten minutes, and then come back and describe the experience.

Share your play in the comments below, and be sure to leave feedback for your fellow writers!

Sue Weems

Website

Sue Weems is a writer, teacher, and traveler with an advanced degree in (mostly fictional) revenge. When she’s not rationalizing her love for parentheses (and dramatic asides), she follows a sailor around the globe with their four children, two dogs, and an impossibly tall stack of books to read. You can read more of her writing tips on her website.

When she’s not rationalizing her love for parentheses (and dramatic asides), she follows a sailor around the globe with their four children, two dogs, and an impossibly tall stack of books to read. You can read more of her writing tips on her website.

Why writing code is not fun and easy → Roem.ru

Walter Vannini

Kids, Column, Education, Translation ru-RU 2017 OOO "Roem" Personnel

“Writing code is not the only activity that requires increased attention. But no one ever says that brain surgery is 'fun' and designing buildings is 'easy'"

Development of events: The programmer is a new working specialty (February 23, 2017)

Big Data consultant and researcher Walter Vannini wrote an essay on Aeon about how making programming easy and fun is wrong and often dangerous. He also tried to understand the reasons why such an attitude towards software creation came from. "Roem!" publishes an essay in translation.

He also tried to understand the reasons why such an attitude towards software creation came from. "Roem!" publishes an essay in translation.

Programming is a piece of cake. At least the gurus of the digital world want to convince us of this. From Code.org, a non-profit organization that promises "Anyone can learn!" to Apple CEO Tim Cook, who believes coding is "fun and interactive", the art and science of software is available to everyone like the alphabet.

Unfortunately, this pink painting has nothing to do with reality. For starters, the mindset inherent in programmers is not often found in people. Software developers, in addition to excellent analytical and creative abilities, need an almost superhuman concentration to cope with the complexity of their tasks. Manic attention to detail is a must; carelessness is prohibited. To maintain this level of concentration, the mind must be in a state that can be called "flow" - a quasi-symbiotic connection between a person and a machine that improves performance and motivation.

Writing code isn't the only activity that requires extra attention. But you never hear that doing brain surgery is “fun” and designing buildings is “easy.” When it comes to programming, why do politicians and technologists say otherwise? For example, it helps bring people into the industry at a time when software (in the words of venture capitalist Marc Andreessen) is “devouring the world” — and thus, by expanding the job market, it keeps the industry on track and keeps wages from rising too high. Another reason is that the very word "programming" sounds routine, as if there is some kind of solution that developers use over and over again to solve any problem. It doesn't help Hollywood, which portrays "coders" as an unavoidably white male with communication problems - a hacker who mindlessly hits keys and can hack the CIA or ruin the plans of the Nazis.

Emphasizing the charm and fun of programming is a bad way to get kids into it. This detracts from their mental faculties and fosters the destructive knowledge that discipline is not needed for development. Anyone who has the slightest idea of programming knows that a minute of practice takes an hour of theory.

Anyone who has the slightest idea of programming knows that a minute of practice takes an hour of theory.

It's better to admit that programming is difficult, technically and ethically. Computers today can only execute orders of varying levels of complexity. Therefore, the developer needs to be very clear: the machine does what you say, not what you mean. An increasing burden of responsibility is being placed on programs, including responsibility for life or death: whether to take self-driving cars, semi-automatic weapons, or Facebook and Google, which interfere with your marital relationship and physical and mental health, to sell them to the most generous bidder. Despite this, business and the state rarely encourage the curiosity of people who want to know what is behind these processes.

All this is built on a purely technical basis. But we cannot say that the issues raised by technology are purely technical. Programming is not a detail that can be left to technicians on the grounds that their decisions will be "scientifically neutral. " Societies are too complex, their algorithms are political. Factory automation has already taken its toll on low-skilled workers in factories and warehouses around the world. White collar workers are next in line. Today's IT giants employ far fewer people than the workers of the industrial giants of the past, and the irony of recruiting people into the ranks of programmers is that these programmers are slowly depriving themselves of their jobs.

" Societies are too complex, their algorithms are political. Factory automation has already taken its toll on low-skilled workers in factories and warehouses around the world. White collar workers are next in line. Today's IT giants employ far fewer people than the workers of the industrial giants of the past, and the irony of recruiting people into the ranks of programmers is that these programmers are slowly depriving themselves of their jobs.

In a world that has become more confusing and complex than ever, where programs play an increasingly important role in daily life, it is irresponsible to talk about programming as a frivolous activity. A program is not just lines of code, and it is not a banal product of technology. Within just a few years, an understanding of programming will be mandatory for any active citizen. The idea that programming is an easy path to social acceptance and personal excellence works to the advantage of a growing techno-plutocracy that hides behind its own technologies.

Authors of quality texts receive - royalties, fame and useful contacts in the comments. Submit articles, reviews and analytics.

Quick search: Children, Column, Education, Translation.

30 comments

Share

"Detective should be written fun..." | White Spot

August 8, 2009 Author: Konstantin Boyandin

Mikhail Mikheev would have turned 98 this fall.

The date is not round, but there is a good reason to remember the talented writer, the author of the famous fantasy-detective novels "Virus B-13" and "The Secret of the White Spot", which at one time were read by a whole generation. Moreover, in November the city will host the White Spot fantasy festival, which aims to draw attention to the figure of Mikheev and to the names of other talented Siberian writers.

Strokes to the portrait

The author of these lines remained forever grateful to Mikhail Mikheev for the unforgettable excitement that was presented by his books. "Virus B-13" was read at night in one breath with a flashlight under the covers. Waiting until the morning to find out "what happened next" simply did not have the strength. Experiences for the heroes were superimposed on the fear that the parents, hearing the rustle of the pages, would take away the treasured reading. This, thank God, did not happen. With the same degree of enthusiasm in the same 11-12 years, only "Spartacus" by Giovagnolli and "The Odyssey of Captain Blood" by Sabatini were read ... Then, already in adulthood, I had a chance to personally express my gratitude to Mikhail Petrovich and receive from him as a gift a book with a signature, which is still carefully preserved ...

"Virus B-13" was read at night in one breath with a flashlight under the covers. Waiting until the morning to find out "what happened next" simply did not have the strength. Experiences for the heroes were superimposed on the fear that the parents, hearing the rustle of the pages, would take away the treasured reading. This, thank God, did not happen. With the same degree of enthusiasm in the same 11-12 years, only "Spartacus" by Giovagnolli and "The Odyssey of Captain Blood" by Sabatini were read ... Then, already in adulthood, I had a chance to personally express my gratitude to Mikhail Petrovich and receive from him as a gift a book with a signature, which is still carefully preserved ...

Today, of course, the story of the villain Professor Morgue, the inventor of a terrible virus, and the Soviet scientist Rusakov, who saves the world, looks somewhat naive. As well as the story of the valiant geologists, engaged in the search for uranium ore, from the "Secrets of the White Spot". But all this is not the point. It is important how famously the author was able to twist the plot! How excited and remembered his heroes! How swiftly he drew more and more new characters into action! It was this art that he taught the members of his Club of Science Fiction Lovers, which he led for many years under the Writers' Union. He treated the writers very tenderly and humanely, and they paid him the same. Many of them later became successful writers and are still grateful to Mikheev for his school.

But all this is not the point. It is important how famously the author was able to twist the plot! How excited and remembered his heroes! How swiftly he drew more and more new characters into action! It was this art that he taught the members of his Club of Science Fiction Lovers, which he led for many years under the Writers' Union. He treated the writers very tenderly and humanely, and they paid him the same. Many of them later became successful writers and are still grateful to Mikheev for his school.

Mikheev told me that he started inventing adventures as a child. In the evenings, he gathered his peers and spent hours entertaining them with fantastic stories - "a shameless compilation of books he had read." As an adult, he did not forget his youthful delights from acquaintance with adventure books. His imagination was filled with wild heroes and fantastic plots, which he poured into the pages of his adventure novels.

He had his own rather peculiar approach to science fiction. And many of the provisions of his "theory" could be argued. But he was never orthodox, he knew how to listen and hear. When, for example, he was given the manuscript of Gennady Prashkevich's fantastic novel "The Stolen Miracle" for review, he, assessing it positively on the whole, expressed a wish to the author to throw out all the documents from there. And that was the heart of the book! There, for example, incredible information was collected for that time about the payment of killer labor or contracts with legionnaires. This information was collected bit by bit, with great difficulty, from foreign sources. For them, in fact, the book was written. Prashkevich called Mikheev back, explained all this intelligibly. Mikheev said "good" and withdrew his objections. The book was published without cuts and made a name for Prashkevich... It was very pleasant to work with him - this is noted by everyone who has ever done it.

And many of the provisions of his "theory" could be argued. But he was never orthodox, he knew how to listen and hear. When, for example, he was given the manuscript of Gennady Prashkevich's fantastic novel "The Stolen Miracle" for review, he, assessing it positively on the whole, expressed a wish to the author to throw out all the documents from there. And that was the heart of the book! There, for example, incredible information was collected for that time about the payment of killer labor or contracts with legionnaires. This information was collected bit by bit, with great difficulty, from foreign sources. For them, in fact, the book was written. Prashkevich called Mikheev back, explained all this intelligibly. Mikheev said "good" and withdrew his objections. The book was published without cuts and made a name for Prashkevich... It was very pleasant to work with him - this is noted by everyone who has ever done it.

Mikheev himself, by the way, wrote not only science fiction and action stories, but also poetic fairy tales for children and travel essays. .. But readers (such are the laws of the genre) still remember him more as the author of action stories. He liked to quote Bertolt Brecht, who argued that "the detective story should be written cheerfully." He also tried to work easily and cheerfully, which, however, did not at all negate his serious and demanding attitude to writing.

.. But readers (such are the laws of the genre) still remember him more as the author of action stories. He liked to quote Bertolt Brecht, who argued that "the detective story should be written cheerfully." He also tried to work easily and cheerfully, which, however, did not at all negate his serious and demanding attitude to writing.

This is the memoirs of Gennady Prashkevich. We hope they will be of interest to you and will add a significant touch to the informal portrait of the writer.

Gennady Prashkevich From Notebooks

On the evening of January 16, 1987, Mikhail Petrovich Mikheev arrived at Akademgorodok. We invited him to a meeting with members of the Literary Club at the House of Scientists.

It was frosty, a hard wind was blowing. Perhaps that is why people gathered slowly. “Martovich,” Mikheev said in a low voice, pacing against the backdrop of a huge black blackboard built into the wall of the Small Hall. “Let’s go down to the dining room and have some coffee. ” And as a highly obligatory person, he warned: "Even if no one comes, I will speak to you."

” And as a highly obligatory person, he warned: "Even if no one comes, I will speak to you."

I didn't mind.

The people, fortunately, have gathered.

Mikheev walked along the slate, smiled and, without removing his tiny pipe from his mouth (by the way, he never lit it up), remarked: "Brecht said that detective stories should be written cheerfully." It was he, as it were, who already answered my question why he stopped writing science fiction.

“Lack of knowledge, Martovich,” he admitted. — Fiction should be written by people who understand science. Science fiction has always been written by people who understand science. I don’t know how it is with foreigners, but it’s the same with us. Obruchev is a geologist, Efremov is a paleontologist, Kazantsev is an engineer, Dneprov is a physicist, the youngest of the Strugatsky brothers is an astrophysicist. You have to be scientific to write science fiction, and I'm just an electrician. I can mess around with technology, nothing more. And in general, Martovich, now police stories are dearer to me than any philosophy. Why should I continue to write fiction if I have already worked out my plots? In front of Efremov, Martovich, I am even shy. This, in my opinion, is no longer a fantasy. Just a very smart person, a very knowledgeable person talking to you, believing that you know as much as he does, no less. And I don't know that much."

And in general, Martovich, now police stories are dearer to me than any philosophy. Why should I continue to write fiction if I have already worked out my plots? In front of Efremov, Martovich, I am even shy. This, in my opinion, is no longer a fantasy. Just a very smart person, a very knowledgeable person talking to you, believing that you know as much as he does, no less. And I don't know that much."

“From fiction, Martovich, Evgeny Ryss scared me away. There was such a writer. After reading my book The Secret of the White Spot, he wrote a terrible review about "some stupid failures in Eastern Siberia." Of course, I didn’t know much about geology, but Yevgeny Ryss proved to me that I’m generally a fool.”

Mikheev sighed and added: "For some reason, geologists like my book."

“I grew up on my own, Martovich. In the thirties he worked as a fitter in an electrical shop in Biysk, he did not think about science fiction, but he read it with pleasure. And he wrote poetry and songs. Well, you know, like "A driver and a Komsomol member met at the factory committee." And once, for a friend’s wedding, I wrote the song “There is a road along the Chuisky tract” - about Kolka Snegirev. For some reason, this song was immediately sung, now many consider it folk. And then I had to worry. The city Biysk newspaper published an article about the poor condition of the Altai roads, frequent accidents, and poor discipline among drivers. And what discipline can drivers have if they sing such songs? the author of the article asked and quoted lines from my song. And at work, they once shouted to me: “Mikheev, to a special department!” I walked, Martovich, and my legs were trembling. You could go anywhere from the special department. And whatever. Let's say, a stage along the same Chuisky. I entered the office, took off my cap. The special officer in uniform looked at my protruding ears for a long time and was silent. I was also silent. I saw, Martovich, that in front of the special officer was a piece of paper with the text of my song.

Well, you know, like "A driver and a Komsomol member met at the factory committee." And once, for a friend’s wedding, I wrote the song “There is a road along the Chuisky tract” - about Kolka Snegirev. For some reason, this song was immediately sung, now many consider it folk. And then I had to worry. The city Biysk newspaper published an article about the poor condition of the Altai roads, frequent accidents, and poor discipline among drivers. And what discipline can drivers have if they sing such songs? the author of the article asked and quoted lines from my song. And at work, they once shouted to me: “Mikheev, to a special department!” I walked, Martovich, and my legs were trembling. You could go anywhere from the special department. And whatever. Let's say, a stage along the same Chuisky. I entered the office, took off my cap. The special officer in uniform looked at my protruding ears for a long time and was silent. I was also silent. I saw, Martovich, that in front of the special officer was a piece of paper with the text of my song. Then the special officer asked: “Your job?” - "My". “Listen,” said the special officer and even slapped the table with his palm, “you are our poet, Mikheev! Maybe learn to send you?

Then the special officer asked: “Your job?” - "My". “Listen,” said the special officer and even slapped the table with his palm, “you are our poet, Mikheev! Maybe learn to send you?

We laughed.

“I've always wanted to write in such a way that my main character has something to love for. Well, how can I write a scientist if I don't know him? In general, - he waved his hand, - my vocation is an electrician. I, Martovich, do not show off. I really love this job. But, of course,” he admitted, “my main business is literature. Usually a person notices a lot, but immediately forgets a lot. And a writer, having found some incredible detail, can keep it for everyone, give it to everyone, and for a long time. For example, what do you know about diamond mining?”

I shrugged.

“Here I am, too,” Mikheev laughed. - In the city of Mirny, where diamonds are mined, I asked the workers I spoke to: “Let's say you stumbled upon a real diamond in rock heaps. Do you immediately carry it to the foreman or call special people? The workers, Martovich, looked at me like I was crazy. “You, grandfather, must have gone crazy,” one of them finally said. “You, grandfather, probably flew off the cut.” - "Why?" “Yes, if one of us, grandfather, sees a diamond, he will run away from him, and before that he will also dig it with the toe of his boot so that it is not visible!” - "But why?" “Yes, because if one of us, grandfather, brings a diamond to the authorities, they will immediately take such a person by the ass and ask: where is the second one?”

“You, grandfather, must have gone crazy,” one of them finally said. “You, grandfather, probably flew off the cut.” - "Why?" “Yes, if one of us, grandfather, sees a diamond, he will run away from him, and before that he will also dig it with the toe of his boot so that it is not visible!” - "But why?" “Yes, because if one of us, grandfather, brings a diamond to the authorities, they will immediately take such a person by the ass and ask: where is the second one?”

“And what about poetry, Mikhail Petrovich? After all, you started with poems and songs.

“Evgeny Ryss scared me away from science fiction, and Elizaveta Konstantinovna Stuart scared me away from poetry. All great writers. After my poetry book Forest Workshop, Elizaveta Konstantinovna categorically stated that everything that I write is not poetry, cannot be poetry and will never be poetry. Poetry requires a completely different feeling. I think, Martovich, she was right. A poet really shouldn't look like a normal person. And I'm normal."

And I'm normal."

“How is that?”

“I, Martovich, will explain to you with an example. We have one poet in our organization, for a long time, due to my stupidity, I did not consider him a poet. Okay, writer. But why a poet, if no one remembers a single line of his poetry? But one day, Martovich, I went with a friend to one eatery not far from the writers' organization - Russian Tea. And they served only tea there, because it happened during the dry law. When we entered, I noticed that in the half-empty hall the poet I am talking about was sitting at the last table. On the table in front of him lay a boiled chicken on a plate, he reluctantly picked it with a fork. Seeing this, I finally decided that he was not a poet at all. So-so, writer. It does not matter that the poet hid a bottle under the table. Think back then everyone did it. Mikhail Sergeevich or Yegor Kuzmich forbade keeping bottles on the table, so everyone kept them under the tables. We were talking with a friend, and then I turned around and saw a picture that helped me understand, Martovich, that I didn’t consider this poet a poet in vain. - Mikheev looked at me and laughed softly: - Some twenty minutes passed, and everything changed with the poet. Now the bottle stood before him on the table, and he hid the hen at his feet under the table. He drinks a sip and picks under the table with a fork. Just, as chess players say, I mixed up the order of moves, but I, Martovich, realized that this man is a poet.

- Mikheev looked at me and laughed softly: - Some twenty minutes passed, and everything changed with the poet. Now the bottle stood before him on the table, and he hid the hen at his feet under the table. He drinks a sip and picks under the table with a fork. Just, as chess players say, I mixed up the order of moves, but I, Martovich, realized that this man is a poet.

Later I looked into the book “Writers about Myself” (Novosibirsk, 1973) and immediately came across the words in Mikheev's article: “The first book was remembered for a long time - as it turned out, for a lifetime! It was Treasure Island. Then immediately went the books of Jack London, Fenimore Cooper, Conan Doyle and other authors of adventure classics. The world of strong, courageous, such attractive heroes immediately captured my imagination. I got these books by hook or by crook, and by the age of twelve or thirteen I managed to read everything I could find from friends and in city libraries. And when there was nowhere to get new books, I began to invent adventures myself.