Kids and emotions

How to Decipher the Emotions Behind Your Child’s…

My four-year-old daughter: You CAN’T comb my hair!

Me: It’s late—we have to leave for school in five minutes. I need to comb your hair.

My daughter: I’ll never let you comb my hair! I want wild hair!

Some version of this battle occurred daily over a very long three weeks, during which I tried five different types of brushing implements—from wide-toothed combs to wet brushes—three different kinds of spray-on conditioners, myriad forms of distraction (songs, books, TV), and, of course, the promise of lots of rewards. Yet nothing worked, for this kiddo did not want to have her hair combed. It was no use.

Quite often, we parent in what could be considered non-ideal circumstances—when we’re physiologically and emotionally running on empty and tending to many other demands. Understandably, this can result in us becoming frustrated and upset when our children refuse to heed our advice or when they continually engage in what we perceive as harmful habits.

Meet the Greater Good Toolkit

From the GGSC to your bookshelf: 30 science-backed tools for well-being.

When it comes to many parenting challenges with typically developing kids, simple strategies can go a long way. However, every so often, a particularly irksome parenting challenge crops up—the kind that just won’t back down in response to our go-to positive reinforcement, clear limit-setting, or distraction.

Clearly, some situations require us to dig deeper. Research suggests that parental mentalizing—the capacity to seek to understand our own and our child’s behaviors from the perspective of underlying mental states, such as thoughts, feelings, and needs—can help us get to the heart of the trickiest parenting issues.

The power of parental mentalizing

Parents who have the ability to mentalize can perceive the less obvious and less immediately apparent causes of their children’s behaviors.

When a child is angry, for example, we might be tempted to respond by giving a firm consequence, such as a time-out, or by removing something that the child likes, such as a prized toy or technology time. But a parent who mentalizes may see the hurt underneath the child’s outward anger and respond in a way that directly addresses that pain and gets to the root of the problem—for instance, by slowing down to ask the child whether they are upset and want to talk about it. In so doing, the parent may be able to remove the reason behind the anger, rather than addressing only the symptom of the problem, and may actually give the child a tool to address this issue in the future: reaching out for support.

But a parent who mentalizes may see the hurt underneath the child’s outward anger and respond in a way that directly addresses that pain and gets to the root of the problem—for instance, by slowing down to ask the child whether they are upset and want to talk about it. In so doing, the parent may be able to remove the reason behind the anger, rather than addressing only the symptom of the problem, and may actually give the child a tool to address this issue in the future: reaching out for support.

It turns out that parents who mentalize see a wide range of benefits in their children. For one, their kids develop greater attachment security, which transpires when children feel safe and secure in their relationships with their parents. Further, in one experiment, parents who mentalized more for their own children persisted longer in trying to soothe a pretend crying baby. This vividly illustrates how being able to reflect on children’s thoughts and feelings may give us the mental flexibility to try multiple approaches in responding to their distress. In turn, not surprisingly, children of parents who mentalize more are able to take better care of their own emotions, engaging in better self-regulation and -soothing.

In turn, not surprisingly, children of parents who mentalize more are able to take better care of their own emotions, engaging in better self-regulation and -soothing.

In addition, recent research suggests that mentalizing may be especially important when parents or kids are experiencing higher levels of stress or trauma. Among mothers who seemed to be more prone to stress, those who mentalized more behaved the most sensitively toward their children. After another stressful night when our toddler refuses to sleep, learning to focus on their mental states and needs could help us respond sensitively to them, and even reduce these types of battles in the future.

Mentalizing also has advantages for the parents themselves. Mentalizing can allow us to reflect on our own emotions in the parenting role, providing clarity on why our children’s behaviors activate such strong reactions in us. For instance, after being criticized for incompetence by her colleague at work one day, a mother might be able to recognize that her frustration about her child’s limit-testing behavior is exaggerated—ultimately more related to her work challenges than to her own child. Such clarity can help us identify the true source of our feelings, which in turn can assist us in regulating them. Ultimately, research suggests that parents higher in mentalizing experience greater well-being in their roles as parents.

Such clarity can help us identify the true source of our feelings, which in turn can assist us in regulating them. Ultimately, research suggests that parents higher in mentalizing experience greater well-being in their roles as parents.

OPENing up to your child

Although mentalizing sounds like a complicated concept, implementing it with your child involves only a few simple steps, represented by the term OPEN.

1. Reflect on your Own emotions. When you’re feeling stressed, pause and think about how you’re feeling, what you’re thinking, and what the impact of that might be on your child. Your stress is a good guide to how your child is probably feeling.

Some questions to ask yourself include:

- How am I feeling right now?

- What’s happening in my body?

- What thoughts or feelings am I having that could be impacting my parenting or my child?

For example, during a stressful parenting moment, you may realize that you’re worried about arriving late somewhere and that pressure could be impacting your behavior, making you clench your fists and grit your teeth. It may also be spilling over into your interactions with your child, causing you to speak more sternly with them.

It may also be spilling over into your interactions with your child, causing you to speak more sternly with them.

Engaging in some mindfulness practices—in the moment or at other times in your day—may also help you to avoid any destructive emotional responses to your child. Learning to check in with yourself and pay attention to your current thoughts and feelings without judgment can help you attend to your own and your child’s experiences.

2. Pause to reflect on your child’s thoughts and feelings. When your child is exhibiting a behavior that is perplexing or upsetting to you, pause to allow yourself to think of all the different potential internal explanations for this behavior, such as the thoughts, feelings, or desires your child might have. Here, it is important to remember that often our emotions are layered, such that we may show one feeling but are actually experiencing others.

Some questions to ask yourself include:

- Is it possible my child is worried, sad, or angry right now?

- Even though my child’s behavior makes it seem as though they are angry, is it possible they are actually feeling something else that they are too scared to show?

- What underlying need might my child have that they are trying to express through their actions? How can I help them give voice to this need?

For example, if your child stomped off to a different room after an interaction with his sibling, it would be easiest to assume that he is angry. If you paused to check on what he might be feeling, you may learn that he is feeling rejected or excluded, and talking about the feelings or getting help from a parent to feel included in his sibling’s play may help him feel better.

If you paused to check on what he might be feeling, you may learn that he is feeling rejected or excluded, and talking about the feelings or getting help from a parent to feel included in his sibling’s play may help him feel better.

Trying to take a third-person perspective on the situation can help you figure out what your child may be experiencing without adding your own interpretation into the mix.

3. Engage. Slow down and ask your child what they are experiencing. Use open-ended questions and convey curiosity in understanding your child’s true thoughts and feelings, wherever they may take you. Make sure to do this at a time when your child does not have any time pressure or competing demands on their attention (a hard thing for a parent to accomplish, we know!).

Statements and questions such as the following may help set the desired tone:

- Is something on your mind?

- I’m wondering if you are feeling upset about something.

- I always want to know how you’re really doing.

4. Be open to New experiences. Once you have created the right environment to talk about your child’s thoughts and feelings, it is important to continue to convey a state of openness to new experiences. Maybe your child has always hated being the center of attention, so when a group of kids sing happy birthday to her, it would be easy to assume that she’s embarrassed. But remember to ask before assuming; you might be surprised to learn that the reason she’s actually upset is that her friends forgot to call her by her preferred nickname. It’s important to remember that, just like us, our children’s thoughts, feelings, and preferences are constantly evolving.

Past experiences serve as a database for us to reference when we encounter new situations. However, we must remain OPEN to the always-evolving child, continually revising this database. Once OPEN, always OPEN.

It turns out that my daughter’s hatred of hair combing had nothing to do with simple defiance, garden-variety limit testing, or avoidance of combing-induced pain. She did not want to comb her extremely blond hair because kids at school made comments about it when it was combed—she is the only kid in her after-school program with blond hair, which makes her stand out, something she detests. Apparently, the groomed look accentuates what makes her “different” from other kids at school, and she was nervous about getting this kind of attention. I happened upon this information when we had a conversation about the combing struggle during a nightly pre-bedtime talk—notably, a less stressful time of day, when emotions run calmer and time pressure is lower.

She did not want to comb her extremely blond hair because kids at school made comments about it when it was combed—she is the only kid in her after-school program with blond hair, which makes her stand out, something she detests. Apparently, the groomed look accentuates what makes her “different” from other kids at school, and she was nervous about getting this kind of attention. I happened upon this information when we had a conversation about the combing struggle during a nightly pre-bedtime talk—notably, a less stressful time of day, when emotions run calmer and time pressure is lower.

This is something I, a child psychologist who studies mentalizing, never would have guessed on my own. It wouldn’t have been the fourth or even the tenth explanation I would have come up with as an account for her behavior.

Knowing that my daughter was nervous about the extra attention of combed hair allowed us to come up with a plan to address the issue in a way that would mutually achieve her parents’ goals (non-tangly hair) and her goals (not attracting undue attention): gradually exposing her to increasing amounts of combing each day over a week.

Although there will undoubtedly be challenges that stump even the most gifted mentalizers, this parenting trick is a good one to have in your back pocket—even better than those amazing wet brushes—especially when all of the rewards in the world can’t untangle the situation.

An Age-By-Age Guide to Helping Kids Manage Emotions

How we react to our kids’ emotions has an impact on the development of their emotional intelligence.

How we react to our kids’ emotions has an impact on the development of their emotional intelligence.

How we react to our kids’ emotions has an impact on the development of their emotional intelligence.

We are all born with emotions, but not all those emotions are pre-wired into our brains. Kids are born with emotional reactions such as crying, frustration, hunger, and pain. But they learn about other emotions as they grow older.

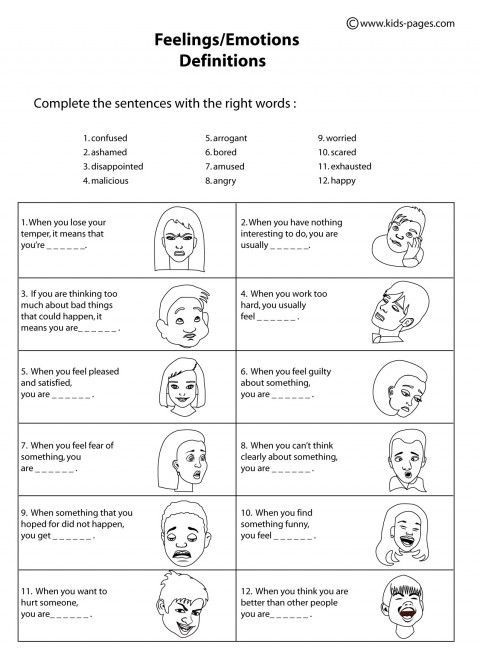

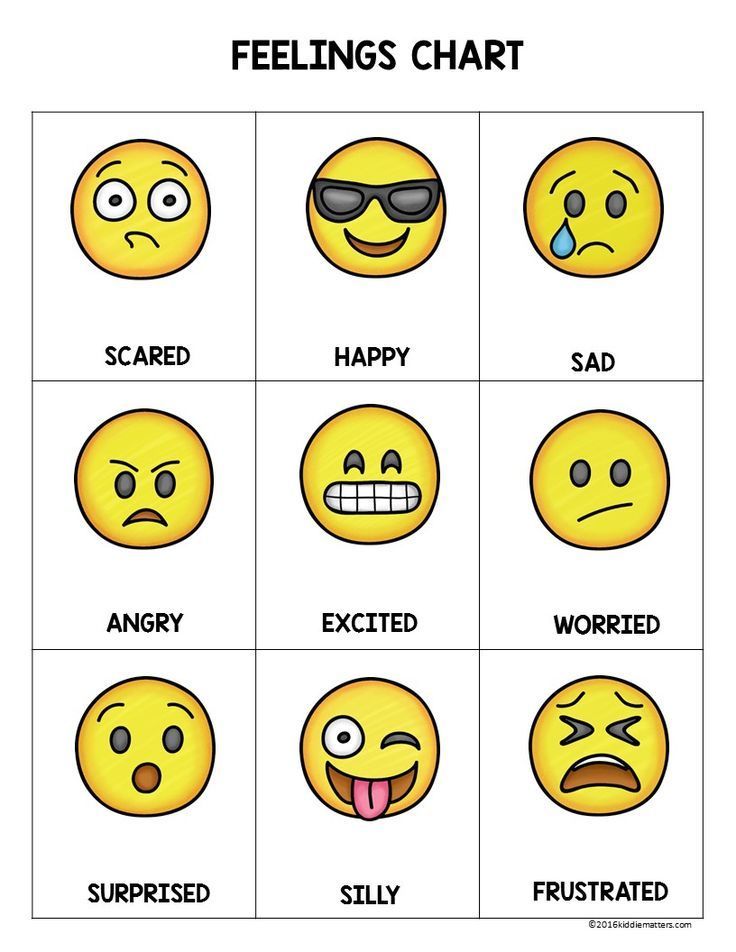

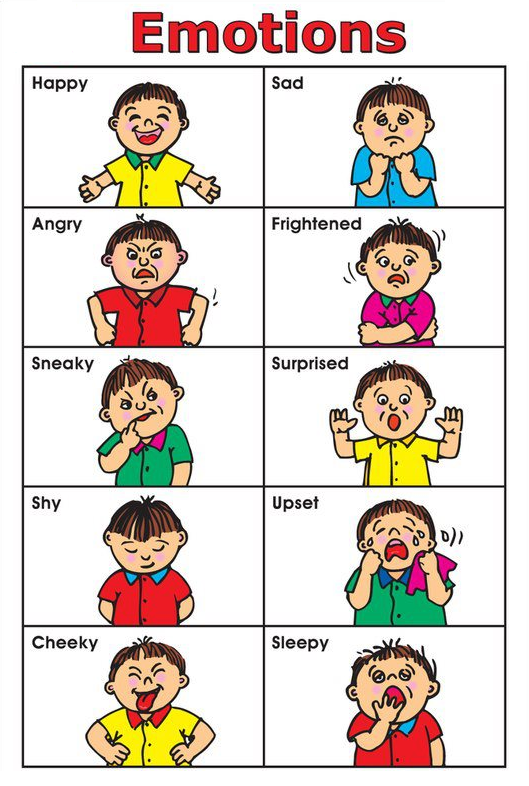

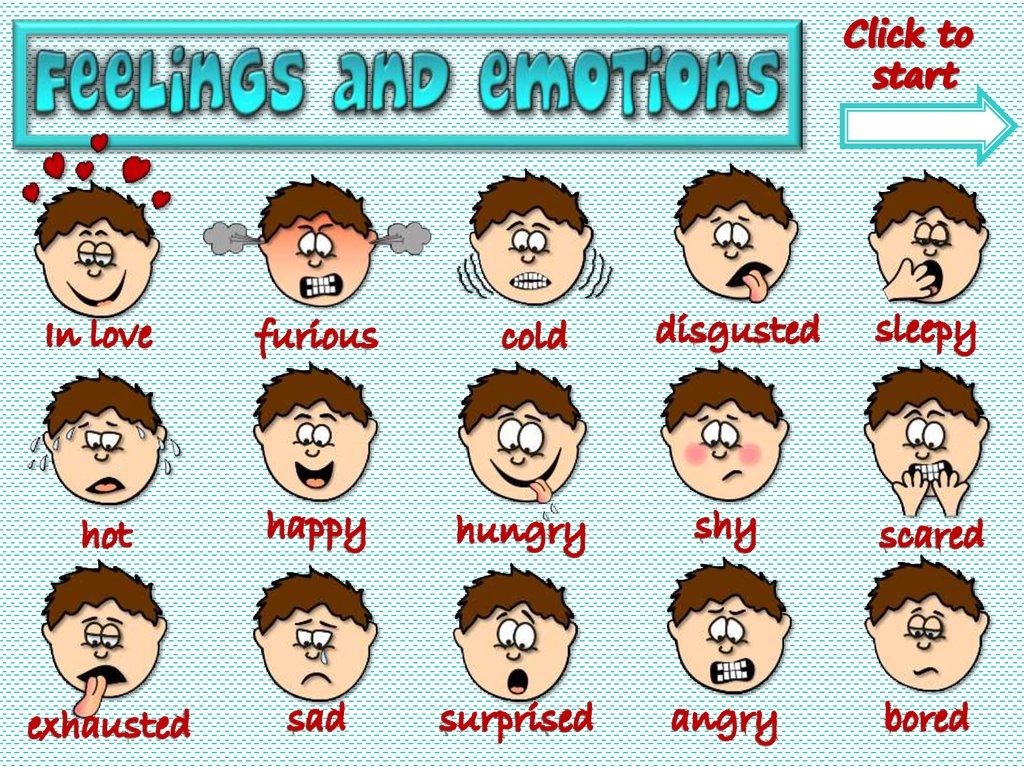

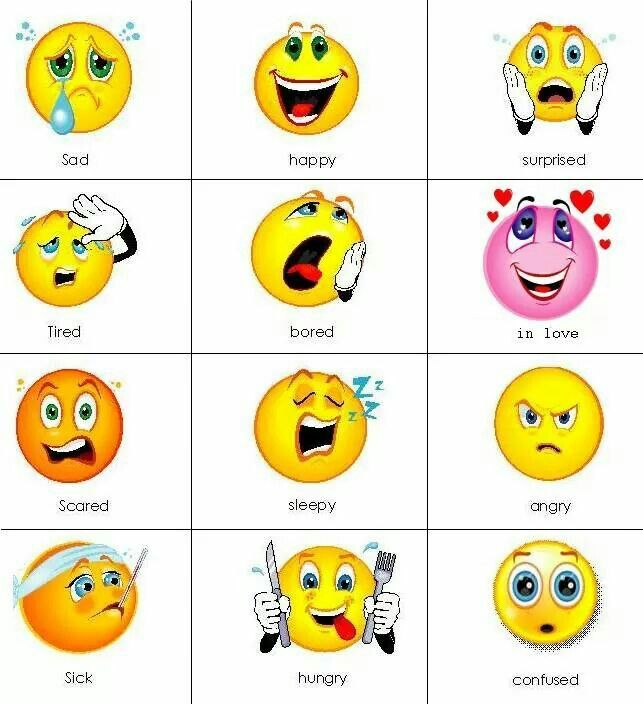

There is no general consensus about the emotions that are in-built versus those learned from emotional, social, and cultural contexts. It is widely accepted, however, that the eight primary in-built emotions are anger, sadness, fear, joy, interest, surprise, disgust, and shame. These are reflected in different variations. For instance, resentment and violence often stem from anger, and anxiety is often associated with fear.

It is widely accepted, however, that the eight primary in-built emotions are anger, sadness, fear, joy, interest, surprise, disgust, and shame. These are reflected in different variations. For instance, resentment and violence often stem from anger, and anxiety is often associated with fear.

Secondary emotions are always linked to these eight primary emotions and reflect our emotional reaction to specific feelings. These emotions are learned from our experiences. For example, a child who has been punished because of a meltdown might feel anxious the next time she gets angry. A child who has been ridiculed for expressing fear might feel shame the next time he gets scared.

In other words, how we react to our kids’ emotions has an impact on the development of their emotional intelligence.

Emotional invalidation prevents kids from learning how to manage their emotions. When we teach kids to identify their emotions, we give them a framework that helps explain how they feel, which makes it easier for them to deal with those emotions in a socially appropriate way.

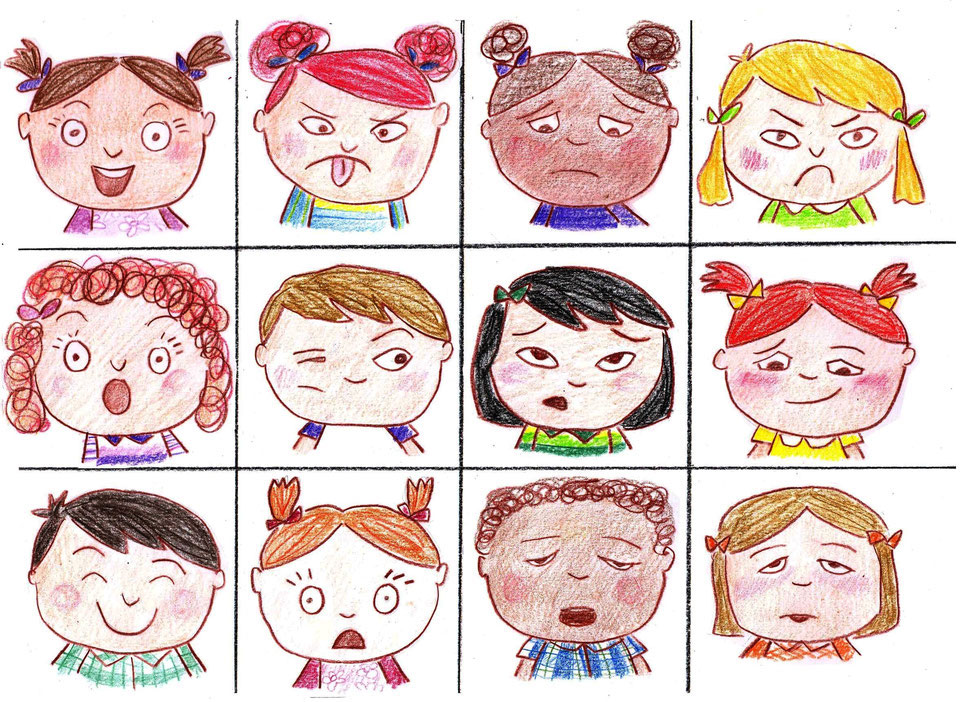

The emotions children experience vary depending on age.

Infants

Infants are essentially guided by emotions pre-wired into their brains. For instance, cries are usually an attempt to avoid unpleasant stimuli or to move towards pleasant stimuli (food, touch, hugs).

Evidence suggests that, in the first six months, infants are capable of experiencing and responding to distress by adopting self-soothing behavior such as sucking. Other studies have found that toddlers develop self-regulation skills in infancy and are able to approach or avoid situations depending on their emotional impact.

How you can help

A recent study suggests that “listening to recordings of play songs can maintain six- to nine-month-old infants in a relatively contented or neutral state considerably longer than recordings of infant-directed or adult-directed speech.”

The study explains that multimodal singing is more effective than maternal speech for calming highly aroused 10-month-old infants. It also suggests that play songs (“The Wheels on the Bus” for instance) are more effective than lullabies at reducing distress.

It also suggests that play songs (“The Wheels on the Bus” for instance) are more effective than lullabies at reducing distress.

Toddlers

By the time they turn one, infants gain an awareness that parents can help them regulate their emotions.

As they grow out of the infancy stage, toddlers begin to understand that certain emotions are associated with certain situations. A number of studies suggest that fear is the most difficult emotion for toddlers. At this age, parents can begin using age-appropriate approaches to talk to kids about emotions and encourage them to name those emotions.

By the time they turn two, kids are able to adopt strategies to deal with difficult emotions. For instance, they are able to distance themselves from the things that upset them.

How you can help

Situation selection, modification, and distraction are the best strategies to help kids deal with anger and fear at this age, according to one study. In other words, helping toddlers avoid distressing situations or distracting them from those situations is one of the most effective emotion-regulation strategies.

As they grow older, toddlers can be taught to handle those situations by themselves. Indeed, they are capable of understanding different emotions and of learning different self-regulation methods that can help them deal with difficult situations. Providing toddlers with an appropriate framework can help them learn how to manage those emotions by themselves.

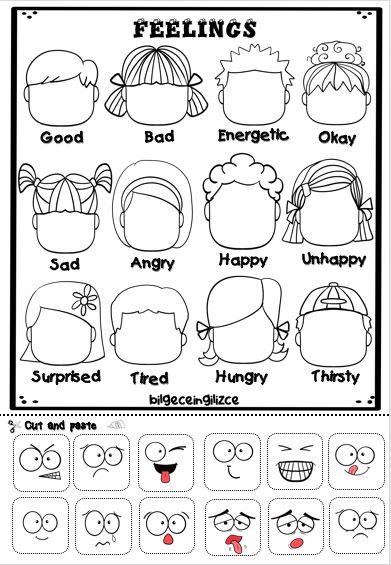

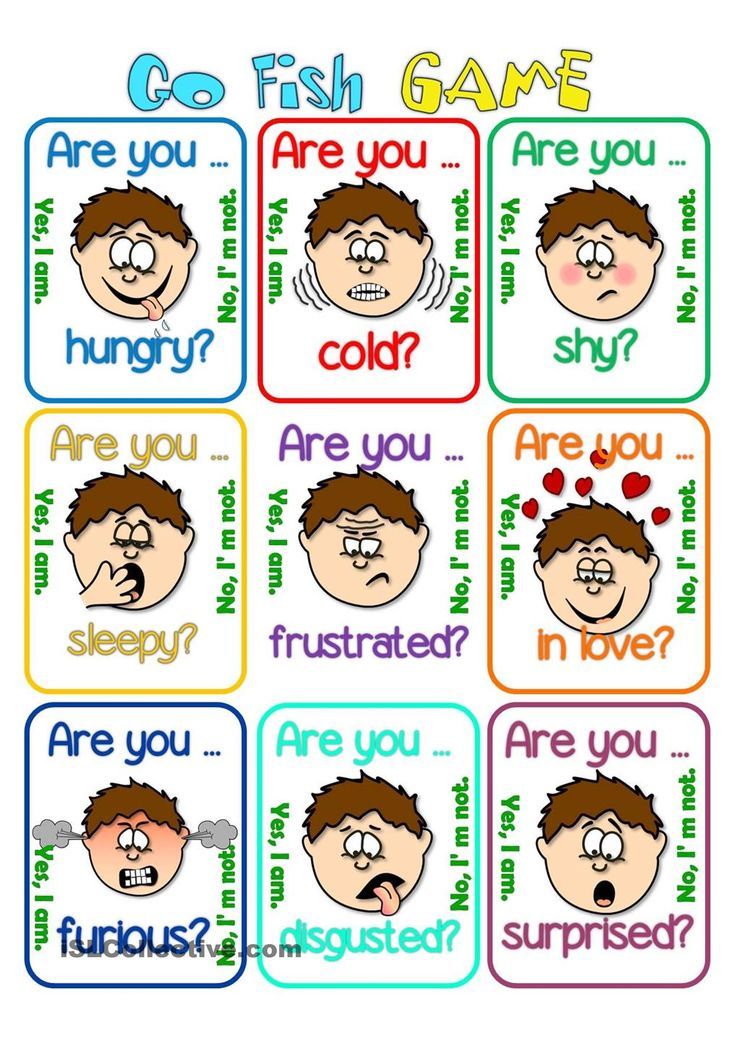

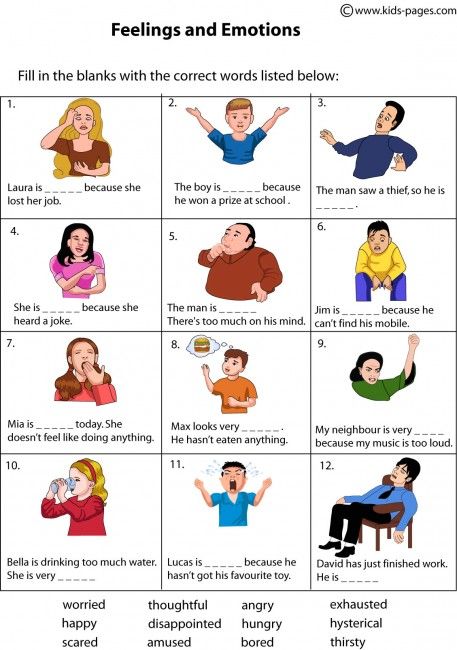

Naming emotions also helps toddlers learn that emotions are normal. Everyday opportunities provide occasions to talk to kids about emotions: “He sure looks angry.” “Why do you think he looks so sad?”

Toddlers also learn about managing their emotions by watching us.

Childhood

Kids experience many emotions during the childhood years. Many secondary emotions come into play at this age as a child’s emotions are either validated or invalidated, influencing future emotional reactions.

Children are able to understand and differentiate appropriate from inappropriate emotional expressions, but they still find it hard to express their emotions, especially if they haven’t learned to identify and name them.

How you can help

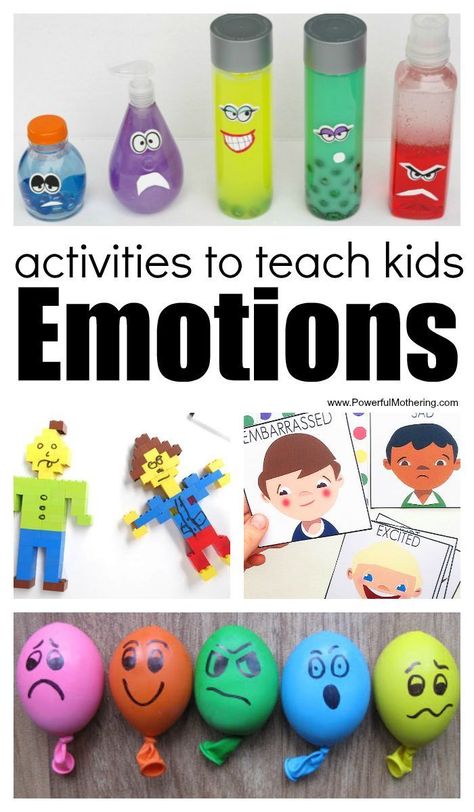

Emotion regulation is not just about expressing emotions in a socially appropriate manner. It is a three-phase process that involves teaching children to identify emotions, helping them identify what triggers those emotions, and teaching them to manage those emotions by themselves. When we teach kids that their emotions are valid, we help them view what they feel as normal and manageable.

Modeling appropriate behavior is also important during the childhood years. The best way to teach your child to react to anger appropriately is to show her how. Evidence suggests that kids pick up our emotions, and that those exposed to many negative emotions are more likely to struggle.

Ultimately, helping kids manage their emotions begins by validating those emotions and providing an environment in which they feel safe to express them. As several studies have shown, kids who feel safe are more likely to develop and use appropriate emotion regulation skills to deal with difficult feelings. ="wpforms-"]

="wpforms-"]

Emotions as a way of successful interaction of the child with the world

Glazunova MA, teacher-psychologist GBU DO TsPMSP Vasileostrovsky district of St. Petersburg

Raising the child's feelings is the most important task facing parents. Preschool childhood is a particularly crucial period in the development of a child, when the main foundation of his personality is laid - a system of ideas about the world around him, about his abilities, about relationships with others.

Leading educational psychologists such as L.S. Vygotsky, D.B. Elkonin, S.S. Mnukhin and many others note the "uniqueness, special significance of this period" for all subsequent human development. Of primary importance are the unique features and conditions created by this age that are not repeated in the further development of children. In other words, it is extremely difficult or not at all possible to make up for what will not be reached in the future. The peculiarity of the psyche of a small person lies in the gradual development of various emotional experiences into personality traits and his character.

The peculiarity of the psyche of a small person lies in the gradual development of various emotional experiences into personality traits and his character.

The emotional mood of a preschooler, and sometimes even a younger schoolchild, is characterized by ease of emergence, changes and susceptibility to external influences. The mental state of the baby is also related to his activities. Modern researchers note that excessive brightness and duration of emotions and feelings experienced by children can cause changes in the body. In this regard, it can be argued that the emotional state directly determines the level of health of the child and, in turn, depends on it.

Children are not always able to determine what emotions and feelings they experience and what causes them. And here the role of a “smart adult” is very important, who will come to their aid and help determine the cause of their bad mood, tell them how to change it. When characterizing the emotional state of children, it is necessary to note its extreme diversity in strength, duration, stability, and depth of flow. Children experience various experiences much brighter and deeper than an adult. "Children's misfortune is boundless, the despair of an adult, perhaps, is incomparable with the despair of a child." A. Merdyuk.

Children experience various experiences much brighter and deeper than an adult. "Children's misfortune is boundless, the despair of an adult, perhaps, is incomparable with the despair of a child." A. Merdyuk.

Emotional development affects not only the formation of personality and character, but also the features of future behavior, as well as the success of relationships with friends, parents, teachers. A child, observing various phenomena in life, evaluates them emotionally, as attractive or repulsive, good or bad - this is how his future value system, his morality is formed. The ability to control one's feelings and emotions, to cope with adverse mental states in difficult situations will help in the future to easily adapt in an unfamiliar place and a new team, as well as to feel confident, independent, free from social fears (shame).

VA Sukhomlinsky notes the enormous influence of the emotional state on the mind and the entire intellectual life of the child. He concludes that the character, the direction of thinking is reflected in the emotional state, which in turn is: "The conductor, from the wave of a wonderful wand, disparate sounds turn into a harmonious sound of a beautiful melody. "

"

An emotionally healthy child will successfully cope with ever-increasing demands and workload not only during the period of preparation for school, but throughout the entire learning process. Such a child, in most cases, will safely and independently overcome age-related crises.

Psychologists assign a huge role in the educational process of children to the development of adequate and safe ways of self-regulation of various adverse emotional states, which in turn is the prevention of various types of addictions, incl. chemical.

For the emergence and maintenance of a favorable emotional psychological climate of the child, parents need to be able not only to determine, but also to correct the state of the preschooler in time.

The following concrete suggestions can serve as the main recommendations for parents that will contribute to the successful development of the emotional sphere of life of preschoolers:

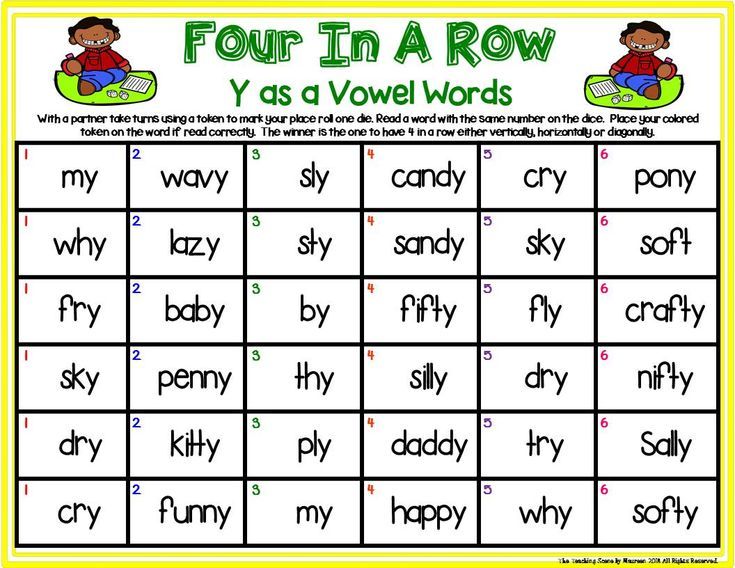

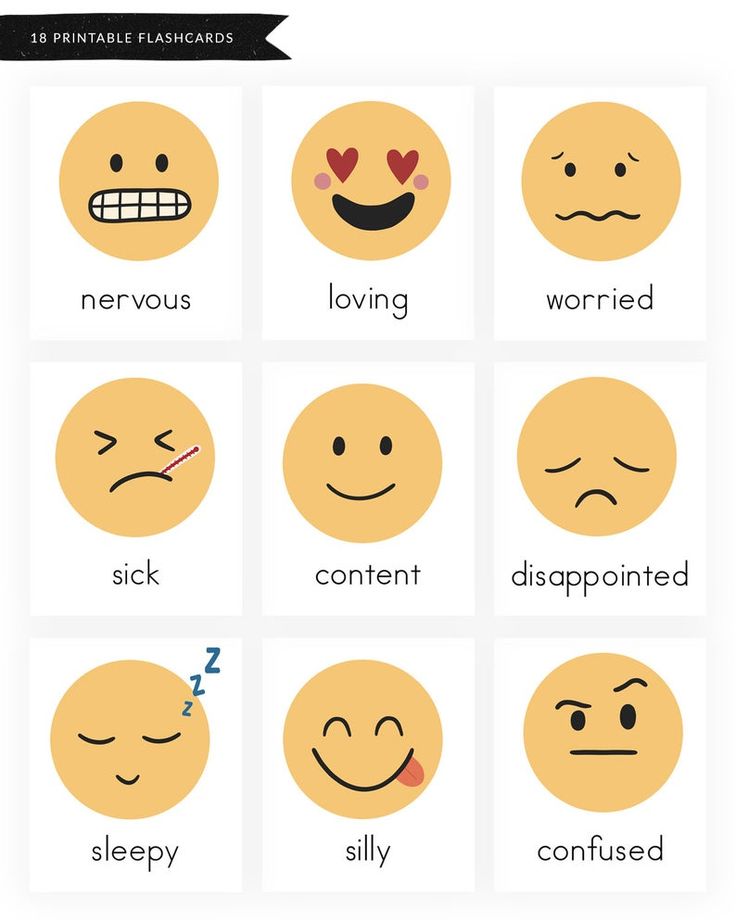

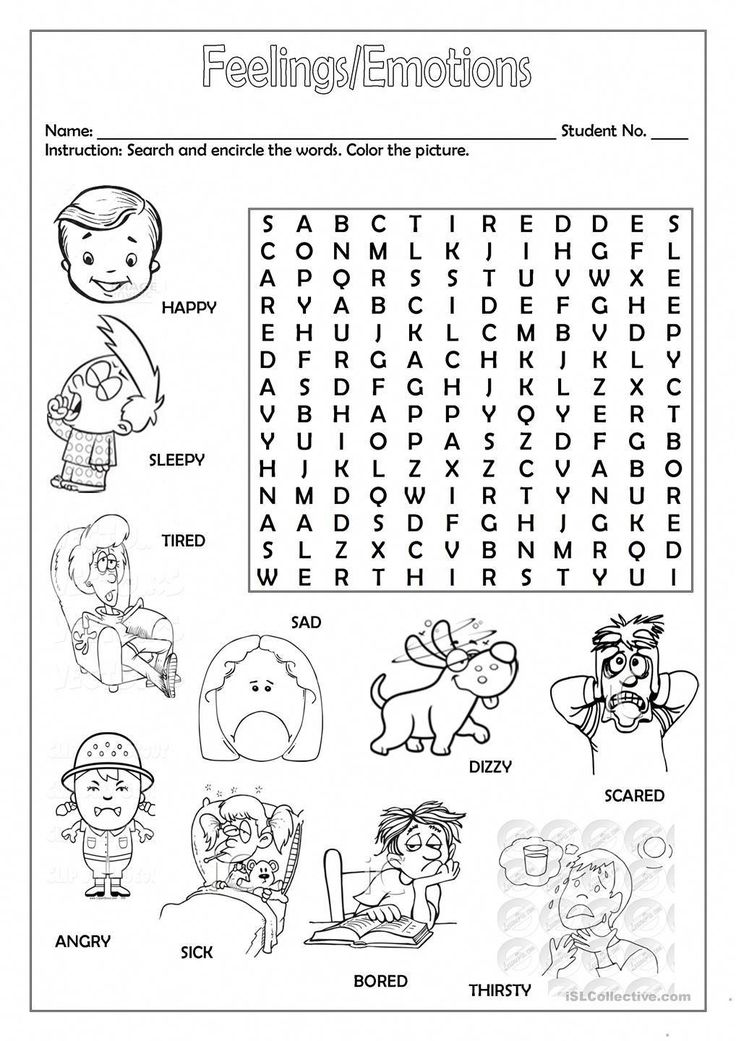

- Develop vocabulary. This means learning to name your feelings and emotions.

Parents, in turn, need to pay attention to their own feelings, read literature on this topic, and be able to recognize the feelings of other people. Introduce into the child's vocabulary as many related words as possible, denoting various emotions and feelings.

Parents, in turn, need to pay attention to their own feelings, read literature on this topic, and be able to recognize the feelings of other people. Introduce into the child's vocabulary as many related words as possible, denoting various emotions and feelings. - To teach children to recognize the difference between emotions and actions.

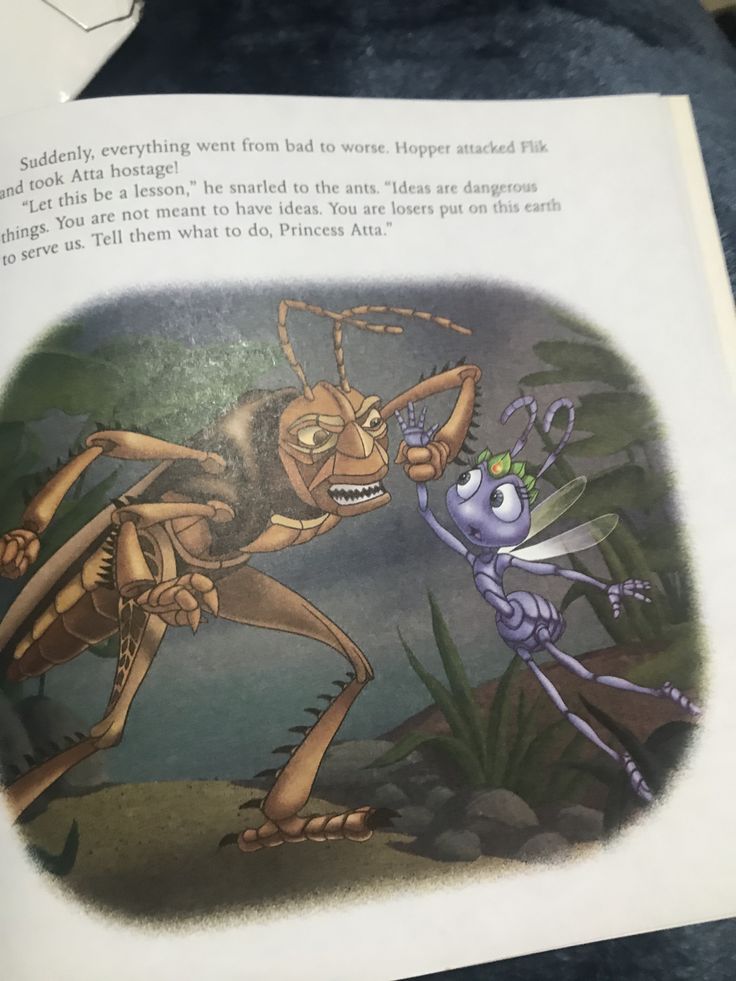

- Explain to the child that feelings cannot be good or bad, but actions can be bad, and one must be held accountable for them.

- Leave children the right to express their feelings and emotions. In no case should you suppress and ignore them. It is important to help the preschooler assert the right to his feelings, this can be achieved simply by listening carefully to him and thinking about his emotions together. You can’t condemn the child for any of his feelings, you can’t step back, remain indifferent, evaluate, because. feelings belong only to him.

- When discussing his feelings with a child, one should not solve the problem for him, but only try to explain the cause of the feelings and emotions that have arisen - this will help him cope on his own.

- Offer your child different ways to "pull himself together." Children can express their feelings in many different ways: physical, creative, and other ways. When various methods have been tried, it is important to ask which one he prefers. If you constantly tell your baby: “Express feelings in words,” then becoming a teenager, he will easily cope with his emotional state. You can offer him various ways to get out of a state of emotional stress, let him make the choice himself.

- Must be consistent. Some situations are resolved quickly, others take time. You can not lose sight of the goal that is set for the child, and, of course, always celebrate the successes that he has achieved.

Managing emotions is a natural side of children's mental development. If this does not happen, there is a violation of emotional regulation, which can lead to various behavioral disorders that require the intervention of a psychologist and long-term corrective work.

The emotional well-being of a child is the way to successful interaction with the world, to the development of a harmonious personality, and in order to achieve this goal, children simply need smart, friendly, loving parents who will not only pass on the necessary knowledge, but also prepare them for independent life. Good luck to you!

Good luck to you!

Emotions for children - studying feelings and emotions with children simply and visually

We will introduce the child to the variety of human emotions, teach them to express their feelings and recognize the emotions of other people through exciting story games

Try for freeTry for free

Why should a child study emotions?

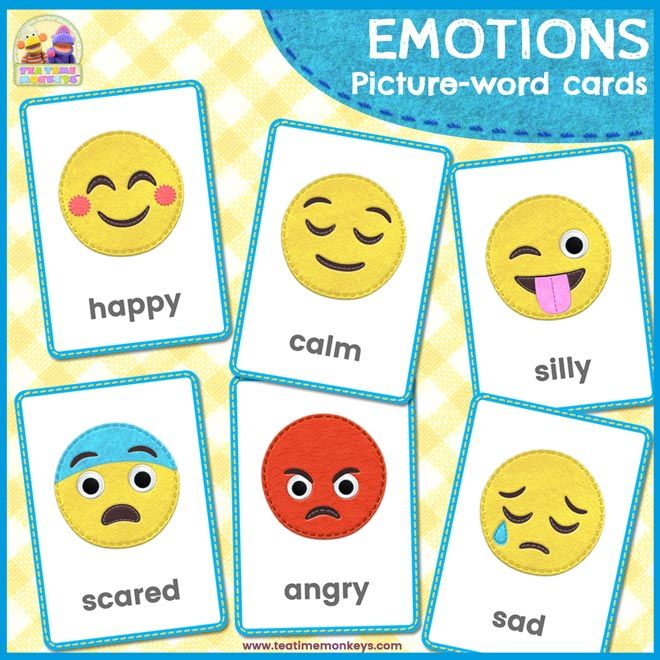

Better understand yourself

It is sometimes difficult for a child to even realize, and even more so to formulate what he wants now, what he feels, why he suddenly became uncomfortable. And most importantly, understand what to do with it. Knowing the emotion "in the face", the child will not be at a loss in front of her.

Manage your emotions

Emotions arise uncontrollably, but how to dispose of them is up to us. Even a brave person can be frightened, but at the same time one will cry and hide, while the other will look fear in the face and defeat it. And this is exactly what you should learn from childhood - otherwise you won’t become successful.

And this is exactly what you should learn from childhood - otherwise you won’t become successful.

Communicate more effectively with people

For productive communication, it is important to be able not only to recognize the emotions of others, but also to correctly express your own. Many will prefer to deal with a calm, friendly interlocutor, and not with a closed beech or a person who expresses his feelings too violently.

Protect yourself from manipulation

Each of us hides our true emotions in some situations. Sometimes it's a matter of etiquette. But sometimes people can pretend to benefit at our expense and even harm us on purpose. This is where basic knowledge of human emotions comes in handy.

What should a child know about emotions?

What are emotions and how they arise

The child should learn that emotions are a reaction to what happens to him. They help us to be aware of our attitudes to people and events, regulate behavior and better understand others. Emotions can arise spontaneously, but there is no need to be afraid of this - they can and should be controlled.

They help us to be aware of our attitudes to people and events, regulate behavior and better understand others. Emotions can arise spontaneously, but there is no need to be afraid of this - they can and should be controlled.

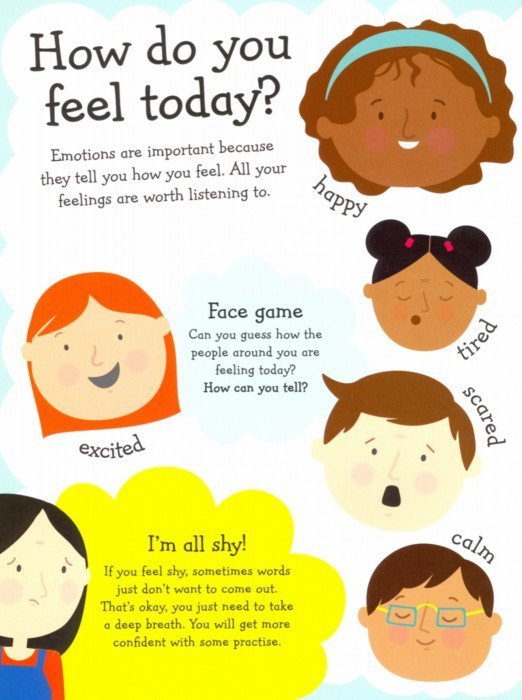

How to visually distinguish one or another emotion

People don't often talk about their feelings and emotions directly. How do you know if a person is scared or sad? Is he happy or nervous? Surprised or interested? Is he sincere? You can distinguish the emotions of other people based on their facial expressions, facial expressions, actions.

How to control your own emotions

Those who do not know how to cope with their emotions are perceived as ill-bred and unpleasant people. Children are usually forgiven for inappropriate expressions of emotions, but the sooner the child learns to take control of them, the better he will get along with people and the more he will achieve in the future.

How to introduce a child to emotions and feelings?

Be sincere with children

Parents who believe that the manifestation of emotions is a weakness and it is better to ignore them altogether will grow up unhappy, socially unadapted children. Feel free to express your feelings in front of a child: angry, laughing out loud, sad. Let him understand that different emotions are normal.

Pay attention to the child's emotions

If you see that the child, for example, is sad, turn to him: “You are sad. What happened? And what do you think to do with it? It is important that he understands: he will not be punished for what he feels, you are ready to analyze his feelings with him - and you will always tell you how to express them, what to direct them to.

Expand your child's emotional vocabulary

Psychologists have noticed a connection between emotional vocabulary and communication and introspection skills. Use at home more synonyms for words denoting sensations. Address the shades of emotions. For example, the general “evil” may mean “irritated”, “angry”.

Use at home more synonyms for words denoting sensations. Address the shades of emotions. For example, the general “evil” may mean “irritated”, “angry”.

Read and analyze literature together

The ability to empathize is formed when a person imagines himself in the place of another. Invite the child to imagine how he would feel if he were in the place of one or another literary hero. What would you do with these emotions? Would you express them or hide them? How would you proceed from them?

We study emotions with children in an interactive

game format

Take a Free Trial Lesson

Explore the interactive play activities your child will have with Umnaziah's Introducing Emotions course.

Try

The structure of the course "Emotions for children"

10 THEMED LESSON GAMES 30-40 MINUTES EVERY

Each lesson is dedicated to one of the situations or emotions. The theory for the lesson is presented in the format of short stories and interactive tasks designed for children aged 6-13.

The theory for the lesson is presented in the format of short stories and interactive tasks designed for children aged 6-13.

40 FUN CHALLENGES BUILT INTO THE LESSON SCENARIO

Each lesson contains 5-7 tasks to consolidate the material covered. All tasks have a plot and bright illustrations or are presented in the form of a game.

UNLIMITED ACCESS TO ALL COURSE MATERIALS

The child will be able to take the course as many times as he needs. You buy the course once and can return to it even after 5 years.

INTERACTIVE KNOWLEDGE QUIZ GAME

The course ends with an interactive quiz game, for the successful completion of which the child receives a certificate. You will be confident in his knowledge!

What topics do we study in the course "Emotions for Children"?

Galaxy of Emotions

Joy and Sadness

Fear and Anger

Interest and Surprise

Trust and Aversion

Complex emotions

What is empathy?

Dating Cloak

Control helmet

Find yourself

Start training

Examples of tasks for the study of emotions

Explore the other steps of the Emotional Intelligence for Kids course

"Introducing Emotions" is the first of four steps in the Emotional Intelligence course for children from Umnaziah. See what topics our students are studying in other levels.

See what topics our students are studying in other levels.

Getting to know emotions

In this course, we will introduce the child to the spectrum of human emotions, try to understand their own feelings, and learn to recognize and recognize the emotions of others. How are curiosity and surprise related? Is it possible to stop worrying at the blackboard and is fear so terrible?

Personality types

The main objective of this course is to show the child the diversity of human characters. We are all different in some ways, but similar in some ways. Why do some guys easily make new acquaintances, while others are reluctant to make contact, and how do different people make decisions?

More

Teamwork

The course is designed for children 9-13 years old and introduces the child to the basic principles of teamwork, teaches to identify and take into account the strengths of each team member and give constructive

feedback.