Teaching how to read and write

Teaching children to read isn’t easy. How do kids actually learn to read?

A student in a Mississippi elementary school reads a book in class. Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger ReportTeaching kids to read isn’t easy; educators often feel strongly about what they think is the “right” way to teach this essential skill. Though teachers’ approaches may differ, the research is pretty clear on how best to help kids learn to read. Here’s what parents should look for in their children’s classroom.

How do kids actually learn how to read?

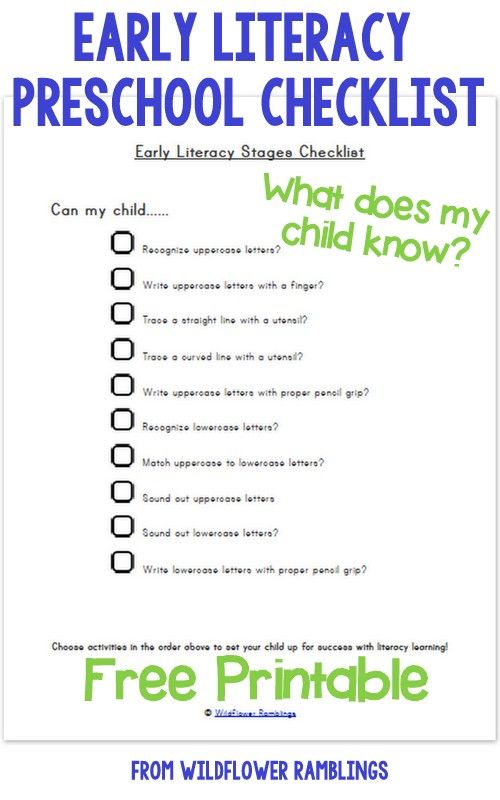

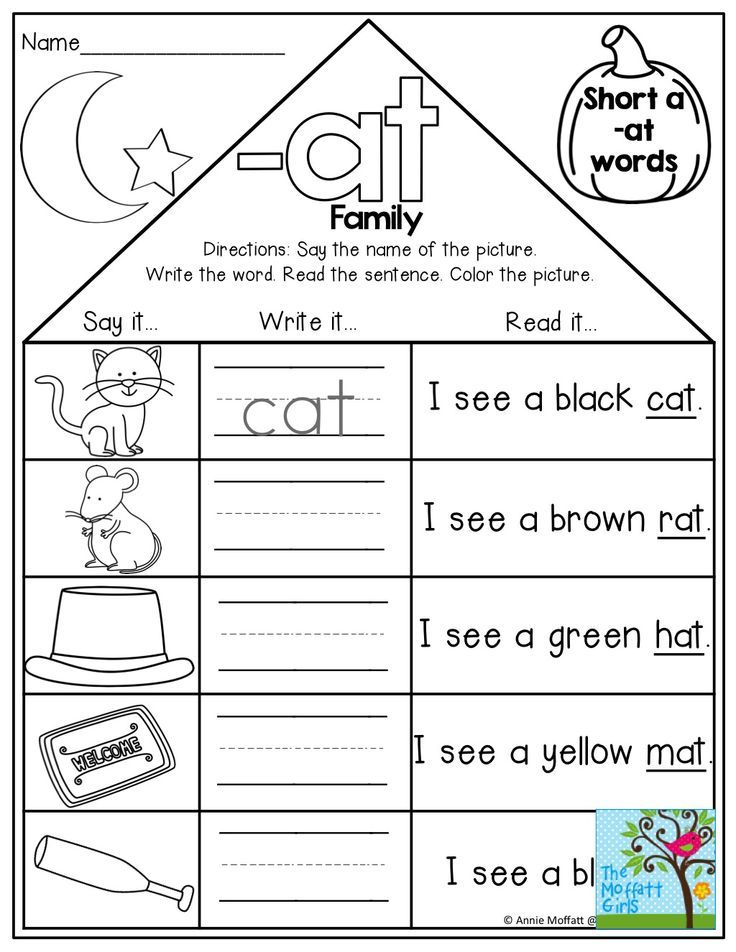

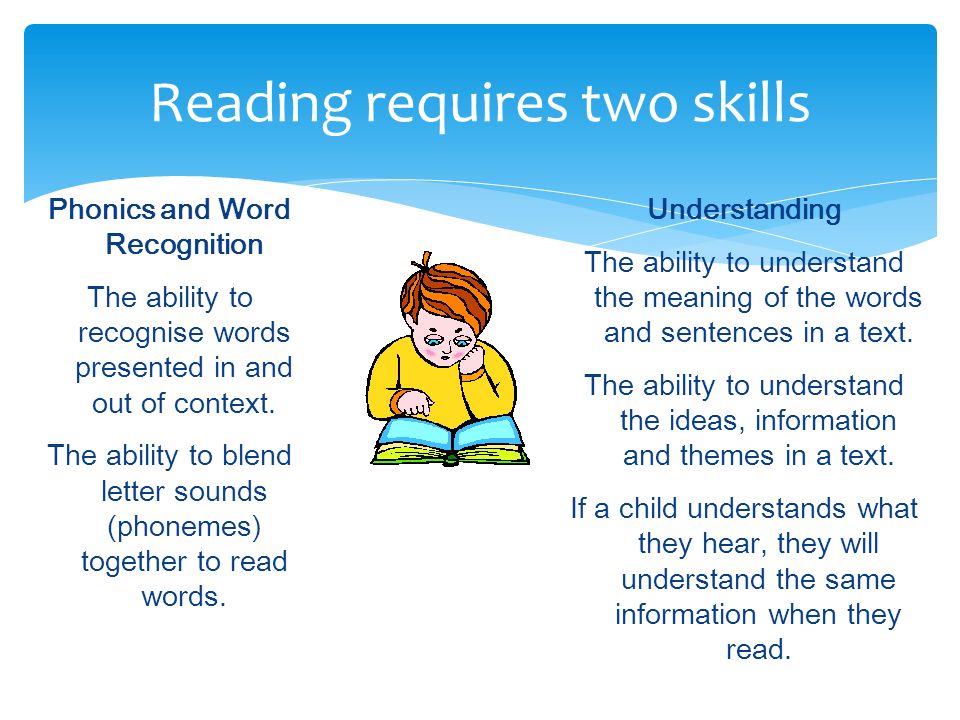

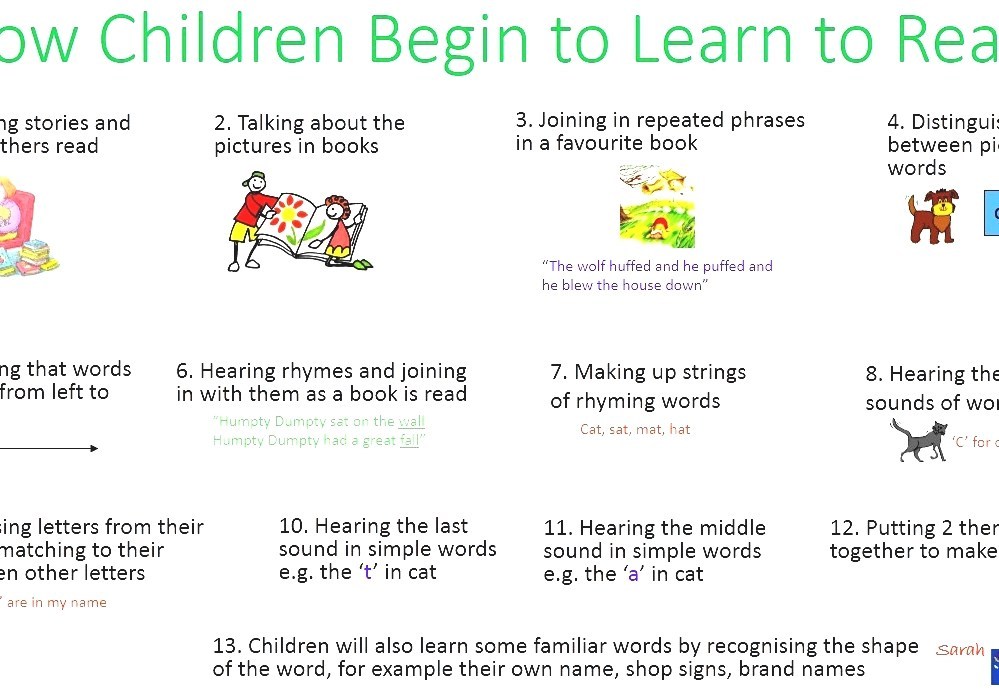

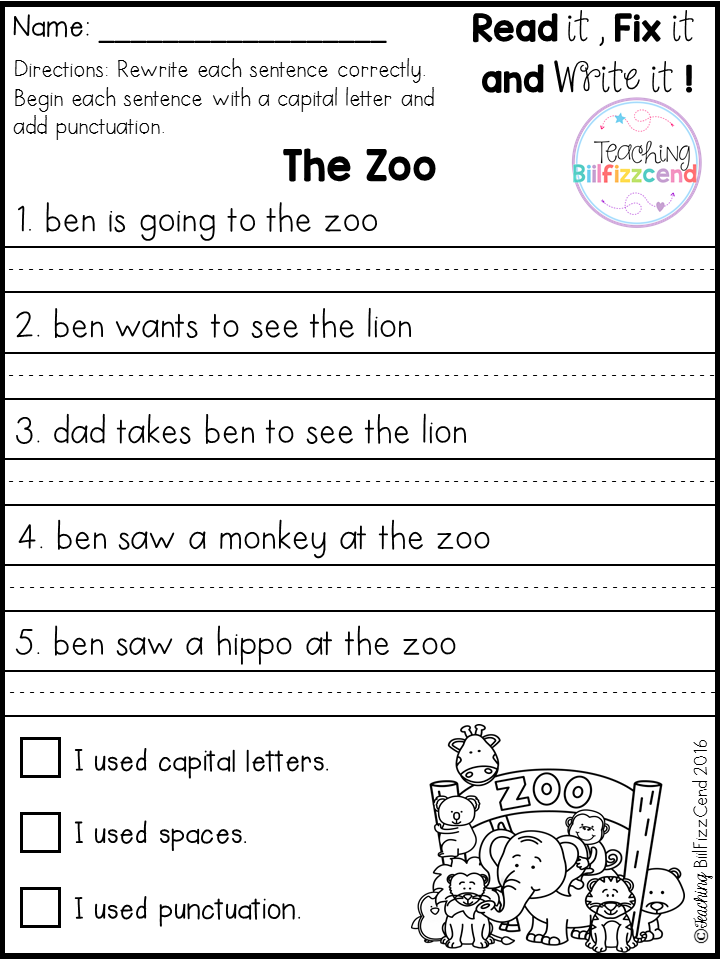

Research shows kids learn to read when they are able to identify letters or combinations of letters and connect those letters to sounds. There’s more to it, of course, like attaching meaning to words and phrases, but phonemic awareness (understanding sounds in spoken words) and an understanding of phonics (knowing that letters in print correspond to sounds) are the most basic first steps to becoming a reader.

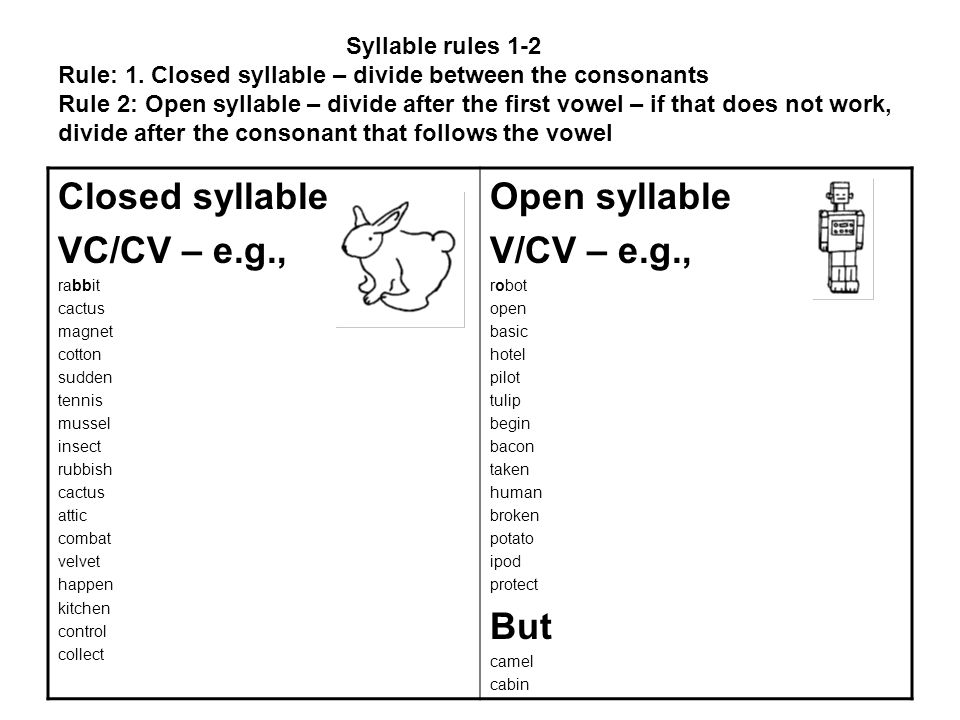

If children can’t master phonics, they are more likely to struggle to read. That’s why researchers say explicit, systematic instruction in phonics is important: Teachers must lead students step by step through a specific sequence of letters and sounds. Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

How should your child’s school teach reading?

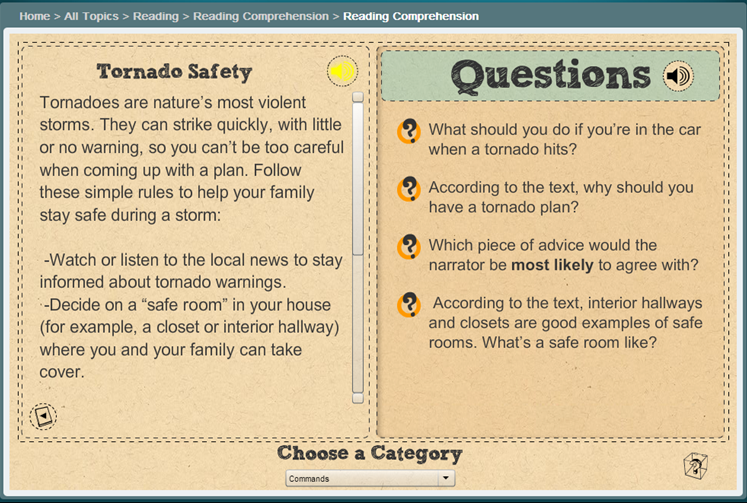

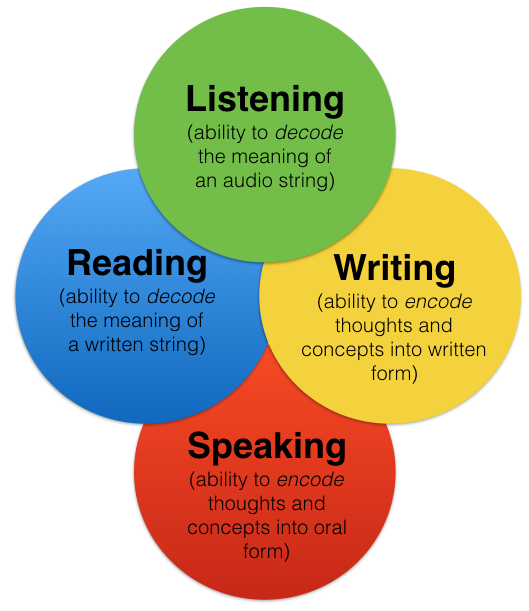

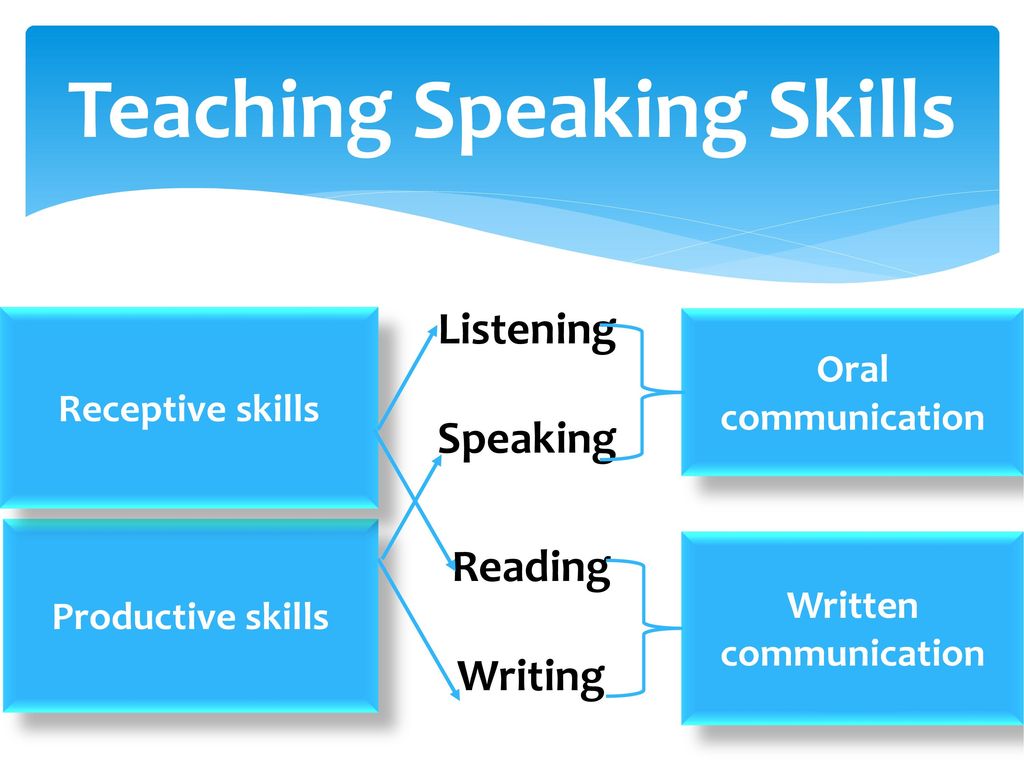

Timothy Shanahan, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago and an expert on reading instruction, said phonics are important in kindergarten through second grade and phonemic awareness should be explicitly taught in kindergarten and first grade. This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

The wars over how to teach reading are back. Here’s the four things you need to know.

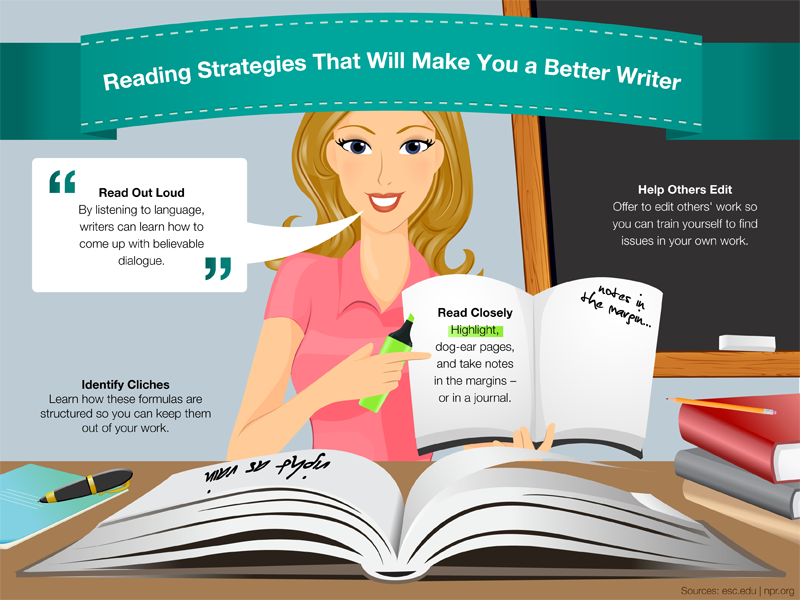

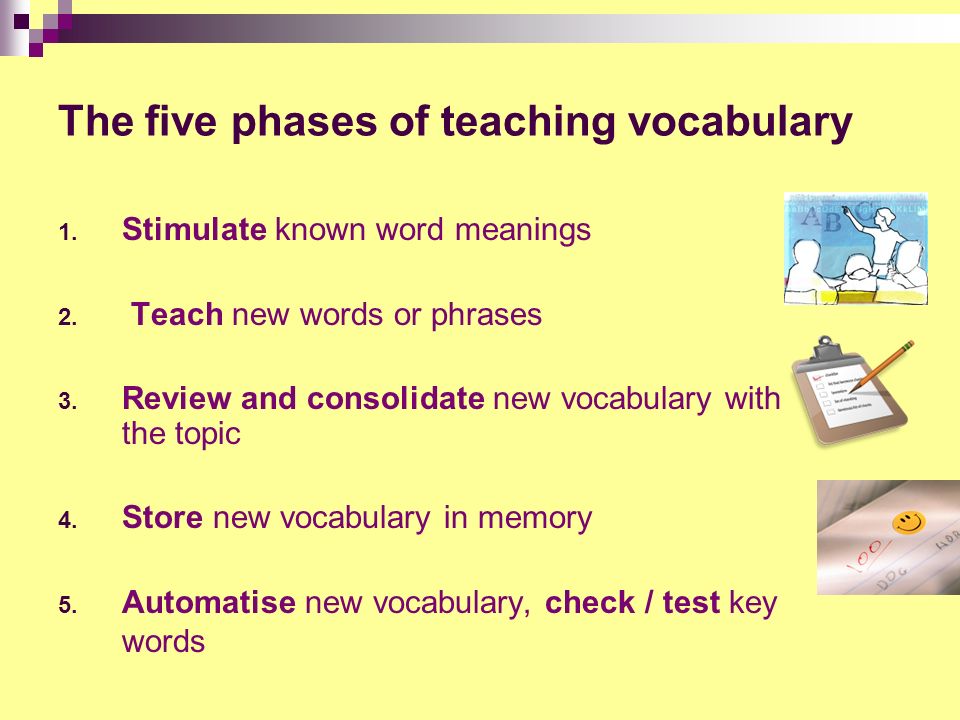

Wiley Blevins, an author and expert on phonics, said a good test parents can use to determine whether a child is receiving research-based reading instruction is to ask their child’s teacher how reading is taught. “They should be able to tell you something more than ‘by reading lots of books’ and ‘developing a love of reading.’ ” Blevins said. Along with time dedicated to teaching phonics, Blevins said children should participate in read-alouds with their teacher to build vocabulary and content knowledge. “These read-alouds must involve interactive conversations to engage students in thinking about the content and using the vocabulary,” he said. “Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

“Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

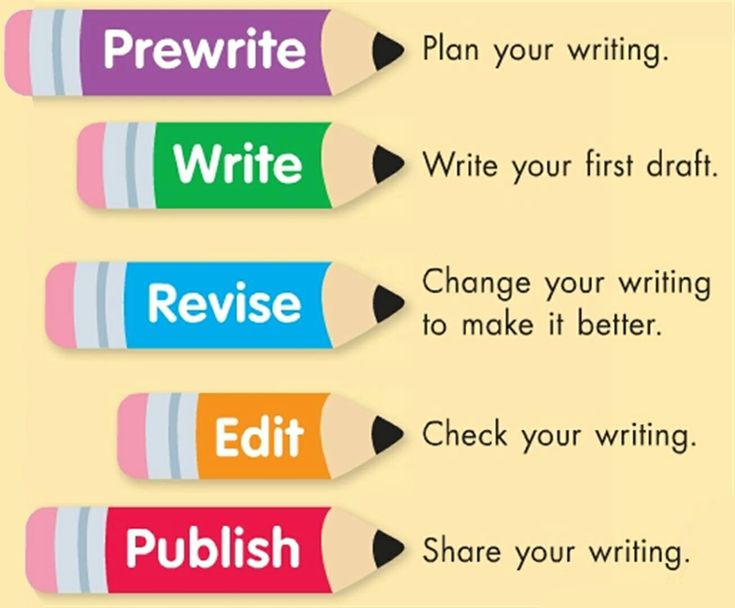

Rasmussen’s school uses a structured approach: Children receive lessons in phonemic awareness, phonics, pre-writing and writing, vocabulary and repeated readings. Research shows this type of “systematic and intensive” approach in several aspects of literacy can turn children who struggle to read into average or above-average readers.

What should schools avoid when teaching reading?

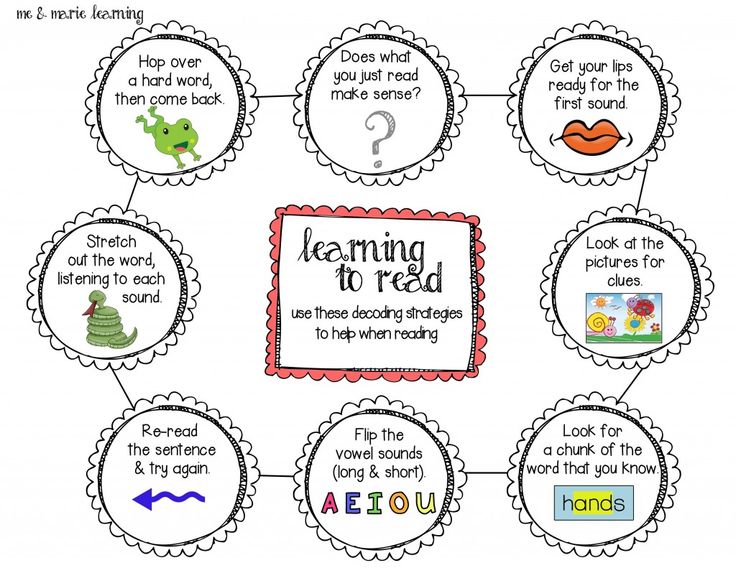

Educators and experts say kids should be encouraged to sound out words, instead of guessing. “We really want to make sure that no kid is guessing,” Rasmussen said. “You really want … your own kid sounding out words and blending words from the earliest level on.” That means children are not told to guess an unfamiliar word by looking at a picture in the book, for example. As children encounter more challenging texts in later grades, avoiding reliance on visual cues also supports fluent reading. “When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

“When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

Related: Teacher Voice: We need phonics, along with other supports, for reading

Blevins and Shanahan caution against organizing books by different reading levels and keeping students at one level until they read with enough fluency to move up to the next level. Although many people may think keeping students at one level will help prevent them from getting frustrated and discouraged by difficult texts, research shows that students actually learn more when they are challenged by reading materials.

Blevins said reliance on “leveled books” can contribute to “a bad habit in readers.” Because students can’t sound out many of the words, they rely on memorizing repeated words and sentence patterns, or on using picture clues to guess words. Rasmussen said making kids stick with one reading level — and, especially, consistently giving some kids texts that are below grade level, rather than giving them supports to bring them to grade level — can also lead to larger gaps in reading ability.

How do I know if a reading curriculum is effective?

Some reading curricula cover more aspects of literacy than others. While almost all programs have some research-based components, the structure of a program can make a big difference, said Rasmussen. Watching children read is the best way to tell if they are receiving proper instruction — explicit, systematic instruction in phonics to establish a foundation for reading, coupled with the use of grade-level texts, offered to all kids.

Parents who are curious about what’s included in the curriculum in their child’s classroom can find sources online, like a chart included in an article by Readingrockets.org which summarizes the various aspects of literacy, including phonics, writing and comprehension strategies, in some of the most popular reading curricula.

Blevins also suggested some questions parents can ask their child’s teacher:

- What is your phonics scope and sequence?

“If research-based, the curriculum must have a clearly defined phonics scope and sequence that serves as the spine of the instruction. ” Blevins said.

” Blevins said.

- Do you have decodable readers (short books with words composed of the letters and sounds students are learning) to practice phonics?

“If no decodable or phonics readers are used, students are unlikely to get the amount of practice and application to get to mastery so they can then transfer these skills to all reading and writing experiences,” Blevins said. “If teachers say they are using leveled books, ask how many words can students sound out based on the phonics skills (teachers) have taught … Can these words be fully sounded out based on the phonics skills you taught or are children only using pieces of the word? They should be fully sounding out the words — not using just the first or first and last letters and guessing at the rest.”

- What are you doing to build students’ vocabulary and background knowledge? How frequent is this instruction? How much time is spent each day doing this?

“It should be a lot,” Blevins said, “and much of it happens during read-alouds, especially informational texts, and science and social studies lessons. ”

”

- Is the research used to support your reading curriculum just about the actual materials, or does it draw from a larger body of research on how children learn to read? How does it connect to the science of reading?

Teachers should be able to answer these questions, said Blevins.

What should I do if my child isn’t progressing in reading?

When a child isn’t progressing, Blevins said, the key is to find out why. “Is it a learning challenge or is your child a curriculum casualty? This is a tough one.” Blevins suggested that parents of kindergarteners and first graders ask their child’s school to test the child’s phonemic awareness, phonics and fluency.

Parents of older children should ask for a test of vocabulary. “These tests will locate some underlying issues as to why your child is struggling reading and understanding what they read,” Blevins said. “Once underlying issues are found, they can be systematically addressed. ”

”

“We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs. But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York

Rasmussen recommended parents work with their school if they are concerned about their children’s progress. By sitting and reading with their children, parents can see the kind of literacy instruction the kids are receiving. If children are trying to guess based on pictures, parents can talk to teachers about increasing phonics instruction.

“Teachers aren’t there doing necessarily bad things or disadvantaging kids purposefully or willfully,” Rasmussen said. “You have many great reading teachers using some effective strategies and some ineffective strategies.”

What can parents do at home to help their children learn to read?

Parents want to help their kids learn how to read but don’t want to push them to the point where they hate reading. “Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

“Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

- Challenge kids to find everything in the house that starts with a specific sound.

- Stretch out one word in a sentence. Ask your child to “pass the salt” but say the individual sounds in the word “salt” instead of the word itself.

- Ask your child to figure out what every family member’s name would be if it started with a “b” sound.

- Sing that annoying “Banana fana fo fanna song.” Jiban said that kind of playful activity can actually help a kid think about the sounds that correspond with letters even if they’re not looking at a letter right in front of them.

- Read your child’s favorite book over and over again. For books that children know well, Jiban suggests that children use their finger to follow along as each word is read. Parents can do the same, or come up with another strategy to help kids follow which words they’re reading on a page.

Giving a child diverse experiences that seem to have nothing to do with reading can also help a child’s reading ability. By having a variety of experiences, Rasmussen said, children will be able to apply their own knowledge to better comprehend texts about various topics.

This story about teaching children to read was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

9 Fun and Easy Tips

With the abundance of information out there, it can seem like there is no clear answer about how to teach a child to read. As a busy parent, you may not have time to wade through all of the conflicting opinions.

That’s why we’re here to help! There are some key elements when it comes to teaching kids to read, so we’ve rounded up nine effective tips to help you boost your child’s reading skills and confidence.

These tips are simple, fit into your lifestyle, and help build foundational reading skills while having fun!

Tips For How To Teach A Child To Read

1) Focus On Letter Sounds Over Letter Names

We used to learn that “b” stands for “ball. ” But when you say the word ball, it sounds different than saying the letter B on its own. That can be a strange concept for a young child to wrap their head around!

” But when you say the word ball, it sounds different than saying the letter B on its own. That can be a strange concept for a young child to wrap their head around!

Instead of focusing on letter names, we recommend teaching them the sounds associated with each letter of the alphabet. For example, you could explain that B makes the /b/ sound (pronounced just like it sounds when you say the word ball aloud).

Once they firmly establish a link between a handful of letters and their sounds, children can begin to sound out short words. Knowing the sounds for B, T, and A allows a child to sound out both bat and tab.

As the number of links between letters and sounds grows, so will the number of words your child can sound out!

Now, does this mean that if your child already began learning by matching formal alphabet letter names with words, they won’t learn to match sounds and letters or learn how to read? Of course not!

We simply recommend this process as a learning method that can help some kids with the jump from letter sounds to words.

2) Begin With Uppercase Letters

Practicing how to make letters is way easier when they all look unique! This is why we teach uppercase letters to children who aren’t in formal schooling yet.

Even though lowercase letters are the most common format for letters (if you open a book at any page, the majority of the letters will be lowercase), uppercase letters are easier to distinguish from one another and, therefore, easier to identify.

Think about it –– “b” and “d” look an awful lot alike! But “B” and “D” are much easier to distinguish. Starting with uppercase letters, then, will help your child to grasp the basics of letter identification and, subsequently, reading.

To help your child learn uppercase letters, we find that engaging their sense of physical touch can be especially useful. If you want to try this, you might consider buying textured paper, like sandpaper, and cutting out the shapes of uppercase letters.

Ask your child to put their hands behind their back, and then place the letter in their hands. They can use their sense of touch to guess what letter they’re holding! You can play the same game with magnetic letters.

They can use their sense of touch to guess what letter they’re holding! You can play the same game with magnetic letters.

3) Incorporate Phonics

Research has demonstrated that kids with a strong background in phonics (the relationship between sounds and symbols) tend to become stronger readers in the long-run.

A phonetic approach to reading shows a child how to go letter by letter — sound by sound — blending the sounds as you go in order to read words that the child (or adult) has not yet memorized.

Once kids develop a level of automatization, they can sound out words almost instantly and only need to employ decoding with longer words. Phonics is best taught explicitly, sequentially, and systematically — which is the method HOMER uses.

If you’re looking for support helping your child learn phonics, our HOMER Learn & Grow app might be exactly what you need! With a proven reading pathway for your child, HOMER makes learning fun!

4) Balance Phonics And Sight Words

Sight words are also an important part of teaching your child how to read. These are common words that are usually not spelled the way they sound and can’t be decoded (sounded out).

These are common words that are usually not spelled the way they sound and can’t be decoded (sounded out).

Because we don’t want to undo the work your child has done to learn phonics, sight words should be memorized. But keep in mind that learning sight words can be challenging for many young children.

So, if you want to give your child a good start on their reading journey, it’s best to spend the majority of your time developing and reinforcing the information and skills needed to sound out words.

5) Talk A Lot

Even though talking is usually thought of as a speech-only skill, that’s not true. Your child is like a sponge. They’re absorbing everything, all the time, including the words you say (and the ones you wish they hadn’t heard)!

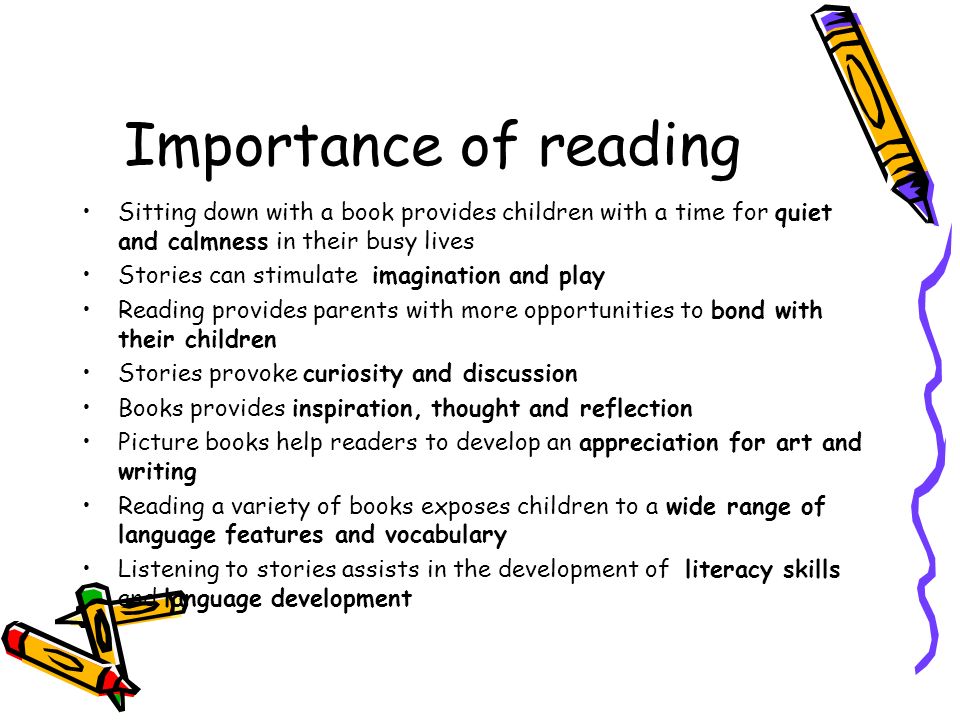

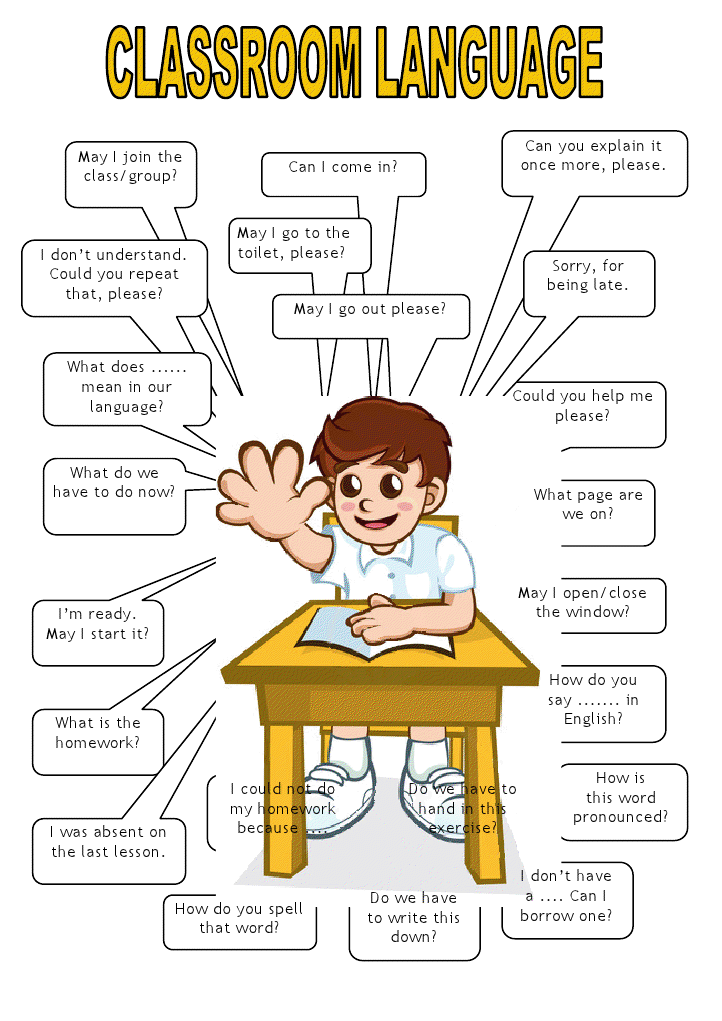

Talking with your child frequently and engaging their listening and storytelling skills can increase their vocabulary.

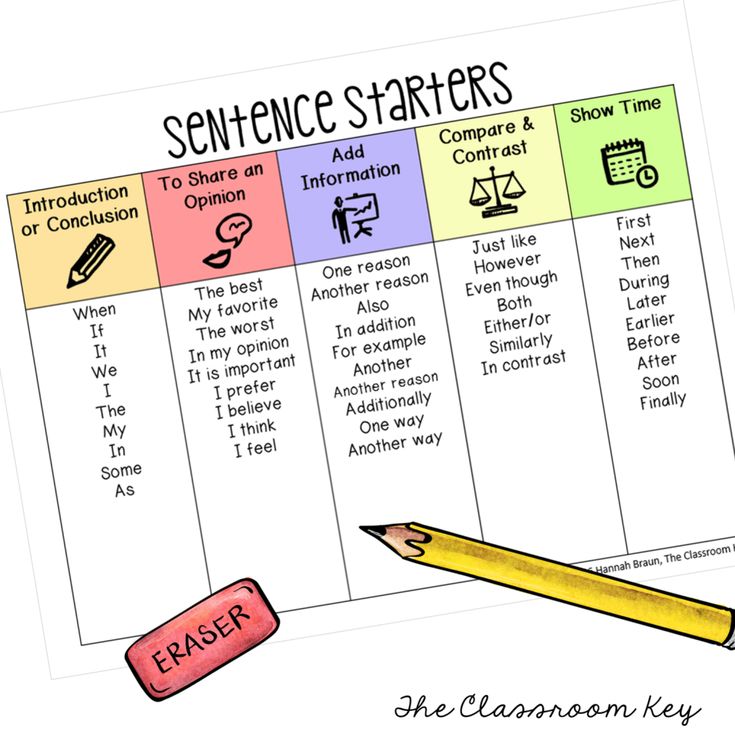

It can also help them form sentences, become familiar with new words and how they are used, as well as learn how to use context clues when someone is speaking about something they may not know a lot about.

All of these skills are extremely helpful for your child on their reading journey, and talking gives you both an opportunity to share and create moments you’ll treasure forever!

6) Keep It Light

Reading is about having fun and exploring the world (real and imaginary) through text, pictures, and illustrations. When it comes to reading, it’s better for your child to be relaxed and focused on what they’re learning than squeezing in a stressful session after a long day.

We’re about halfway through the list and want to give a gentle reminder that your child shouldn’t feel any pressure when it comes to reading — and neither should you!

Although consistency is always helpful, we recommend focusing on quality over quantity. Fifteen minutes might sound like a short amount of time, but studies have shown that 15 minutes a day of HOMER’s reading pathway can increase early reading scores by 74%!

It may also take some time to find out exactly what will keep your child interested and engaged in learning. That’s OK! If it’s not fun, lighthearted, and enjoyable for you and your child, then shake it off and try something new.

That’s OK! If it’s not fun, lighthearted, and enjoyable for you and your child, then shake it off and try something new.

7) Practice Shared Reading

While you read with your child, consider asking them to repeat words or sentences back to you every now and then while you follow along with your finger.

There’s no need to stop your reading time completely if your child struggles with a particular word. An encouraging reminder of what the word means or how it’s pronounced is plenty!

Another option is to split reading aloud time with your child. For emerging readers, you can read one line and then ask them to read the next. For older children, reading one page and letting them read the next page is beneficial.

Doing this helps your child feel capable and confident, which is important for encouraging them to read well and consistently!

This technique also gets your child more acquainted with the natural flow of reading. While they look at the pictures and listen happily to the story, they’ll begin to focus on the words they are reading and engage more with the book in front of them.

Rereading books can also be helpful. It allows children to develop a deeper understanding of the words in a text, make familiar words into “known” words that are then incorporated into their vocabulary, and form a connection with the story.

We wholeheartedly recommend rereading!

8) Play Word Games

Getting your child involved in reading doesn’t have to be about just books. Word games can be a great way to engage your child’s skills without reading a whole story at once.

One of our favorite reading games only requires a stack of Post-It notes and a bunched-up sock. For this activity, write sight words or words your child can sound out onto separate Post-It notes. Then stick the notes to the wall.

Your child can then stand in front of the Post-Its with the bunched-up sock in their hands. You say one of the words and your child throws the sock-ball at the Post-It note that matches!

9) Read With Unconventional Materials

In the same way that word games can help your child learn how to read, so can encouraging your child to read without actually using books!

If you’re interested in doing this, consider using PlayDoh, clay, paint, or indoor-safe sand to form and shape letters or words.

Another option is to fill a large pot with magnetic letters. For emerging learners, suggest that they pull a letter from the pot and try to name the sound it makes. For slightly older learners, see if they can name a word that begins with the same sound, or grab a collection of letters that come together to form a word.

As your child becomes more proficient, you can scale these activities to make them a little more advanced. And remember to have fun with it!

Reading Comes With Time And Practice

Overall, we want to leave you with this: there is no single answer to how to teach a child to read. What works for your neighbor’s child may not work for yours –– and that’s perfectly OK!

Patience, practicing a little every day, and emphasizing activities that let your child enjoy reading are the things we encourage most. Reading is about fun, exploration, and learning!

And if you ever need a bit of support, we’re here for you! At HOMER, we’re your learning partner. Start your child’s reading journey with confidence with our personalized program plus expert tips and learning resources.

Start your child’s reading journey with confidence with our personalized program plus expert tips and learning resources.

Author

Teaching reading and writing as stages of written translation Text of a scientific article in the specialty "Linguistics and Literary Studies"

5. Pejn-Gollu'ej Ral'f Kniga arbaletov. Istoriya srednevekovogo metatel'nogo oruzhiya. Translated from anglijskogo E.A. Kaka. Moscow: ZAO Centrpoligraf, 2005.

Composer R.A. Kasimov. Sterlitamak Zajnab Biishevoj, 2009.

The article was received on 29.09.16

UDC 803.0-853=03(07)

Kondrashova N.V., Cand. of Sciences (Pedagogy), senior lecturer, Head of Department of Russian as a Foreign Language,

National Research University of Information Technologies, Mechanics and Optics (St. Petersburg, Russia),

Е-mail: [email protected]

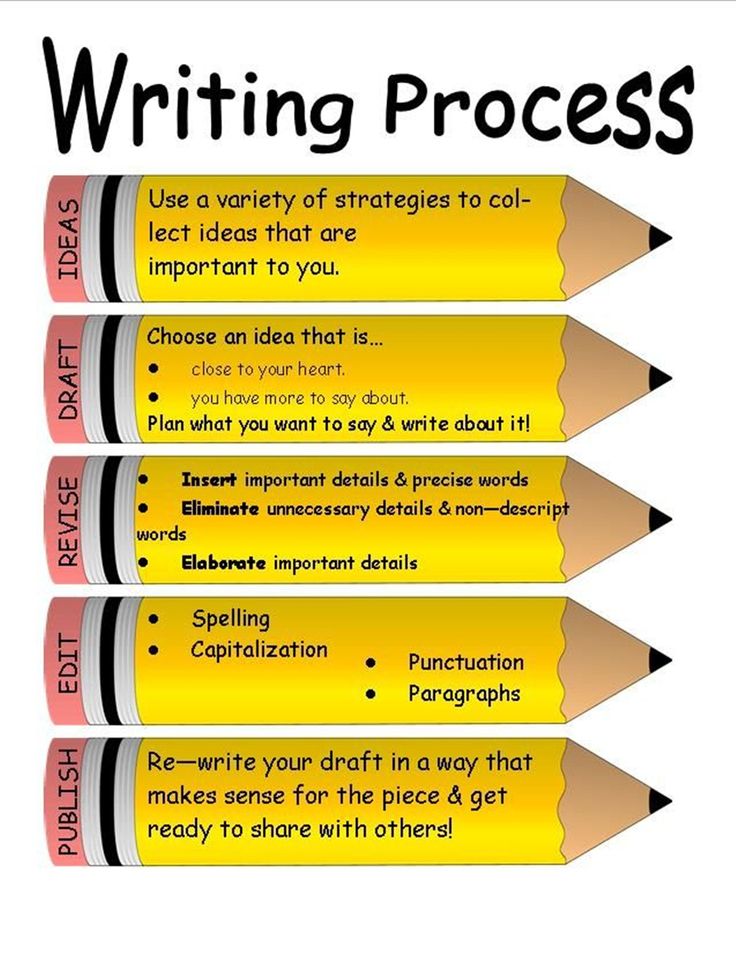

TEACHING READING AND WRITING AS STAGES OF TRANSLATION. The article discusses a translation process from a psycholinguistic point of view. Special attention is paid to stages of reading an original text and writing a translated text. The author analyzes mechanisms of perception and understanding written language and mechanisms of writing. On the basis of the conducted psycholinguistic analysis of reading and writing as stages of translation, the author gives methodological recommendations on how to train these language skills. Reading subskills that are necessary to understand the original written text, as well as mechanisms to form writing skills are defined and described. The researcher concludes that the mechanisms of perception and of speech production are similar, and that there is a necessity to conduct a comprehensive training in reading and writing as stages of translation.

The article discusses a translation process from a psycholinguistic point of view. Special attention is paid to stages of reading an original text and writing a translated text. The author analyzes mechanisms of perception and understanding written language and mechanisms of writing. On the basis of the conducted psycholinguistic analysis of reading and writing as stages of translation, the author gives methodological recommendations on how to train these language skills. Reading subskills that are necessary to understand the original written text, as well as mechanisms to form writing skills are defined and described. The researcher concludes that the mechanisms of perception and of speech production are similar, and that there is a necessity to conduct a comprehensive training in reading and writing as stages of translation.

Key words: translation, reading, writing, perception, comprehension, speech production.

N.V. Kondrashova, Ph.D. ped. Sciences, Assoc., Head. cafe Russian as a Foreign Language, St. Petersburg

Petersburg

National Research University of Information Technologies, Mechanics and Optics (ITMO University

), St. Petersburg, E-mail: [email protected]

TEACHING READING AND WRITING AS STAGES OF WRITTEN TRANSLATION

The article examines the process of translation from a psycholinguistic point of view. Particular attention is paid to the stages of reading the source text and compiling a written translated text. The author analyzes the mechanisms of the semantic perception of written speech and the mechanisms of writing. Based on the psycholinguistic analysis of reading and writing as stages of written translation, the author gives methodological recommendations for teaching these types of speech activity. The types of reading necessary for understanding the original written text, as well as the mechanisms for the formation of writing skills, are singled out and considered. The article concludes that the mechanisms of speech perception and production are similar and substantiates the need for comprehensive teaching of reading and writing as stages of visual-written translation.

Key words: translation, reading, writing, perception, understanding, speech generation.

Understanding written source text (hereinafter referred to as IT) by a translator is a multi-stage process that begins with the physical perception of text units. The double-sidedness of the word as a linguistic sign creates a special specificity of the perception of written speech. When recognizing signs of written speech, not only their perception takes place, but semantic perception - reading.

“Reading is the process of perception and active processing of information graphically encoded according to the system of a particular language” [1, p. eleven]. From a psychological point of view, reading is an unusually complex process of activity of the human higher nervous system, characterized by a huge amount of subconscious brain work. There are two aspects here: technical and semantic. The technical (perceptual) side of reading is the visual perception of written speech; here there is a comparison of the graphic symbol with a trace in the cerebral cortex. The semantic (conceptual) side of reading consists in correlating graphic images of words with concepts and in understanding the meaning of the entire text; here the entrance into the sphere of the mental lexicon and the identification of the received percept with the concept (concept) is carried out [2, p. 102].

The semantic (conceptual) side of reading consists in correlating graphic images of words with concepts and in understanding the meaning of the entire text; here the entrance into the sphere of the mental lexicon and the identification of the received percept with the concept (concept) is carried out [2, p. 102].

Although the perceptual and conceptual mechanisms of reading closely interact, they are still two different, sequential acts. In addition, if the perception of the words of the native language is almost always accompanied by their understanding, then when reading a written foreign text, this is not always the case. Therefore, we consider it necessary to conditionally divide and consider the stages of perception and understanding of written IT separately.

Perception is made up of sensations. Sensation is a mental process of reflecting the individual qualities of objects or phenomena of reality that directly affect our senses [3]. The perception of speech is also based on sensations. This fact seems significant to us when considering written translation activities, in which the initial and final product is a holistic written text - a material object capable of influencing the human senses.

This fact seems significant to us when considering written translation activities, in which the initial and final product is a holistic written text - a material object capable of influencing the human senses.

When perceiving any object, information processing moves from the general to the particular. First, the general impression of the object appears, then its components are analyzed. When perceiving a text, its preliminary holistic image is very important, however, as a complex object, the text requires great attention to its details, that is, to the words, because the stages of the process of forming the image of the text are the sequential formation and accumulation of images of its constituent words.

The perception and recognition of a word as a stimulus is a complex activity. Identification of a stimulus is “the whole ensemble of mental processes, the product of which is the subjective experience of knowledge (understanding) of what is being discussed, the willingness to operate with this knowledge, taking into account the versatile previous experience and emotional and evaluative nuances, with the constant interaction of the conscious and unconscious, verbalized and not amenable to verbalization” [2, p. 103]. When a word is recognized, its phonetic, spelling, syntactic and semantic representation is updated, that is, the mental representation of the stimulus, its trace in the cerebral cortex. From the physical characteristics of the signal through their mental representations in memory, there is a transition to the meaning of the word. From the point of view of physiology, if written speech is perceived, then the primary visual cortex is first activated [3, p. 142]. Consequently, for the identification of graphic speech, the spelling representation of the word will be the base one, therefore, the formation of spelling representations of words in the mental lexicon of a person, that is, a good visual memory, will be the key to easy access to the lexical meaning of the word. But orthographic representations of words alone are not enough. The surface tier of the lexicon is subdivided into 2 sub-tiers: the sub-tier of graphic images and the sub-tier of sound (auditory) images. Researchers note that in the process of recognition of a graphic word, phonetic representation is activated almost immediately after the visual presentation of a graphic stimulus - within 60 ms [2, p.

103]. When a word is recognized, its phonetic, spelling, syntactic and semantic representation is updated, that is, the mental representation of the stimulus, its trace in the cerebral cortex. From the physical characteristics of the signal through their mental representations in memory, there is a transition to the meaning of the word. From the point of view of physiology, if written speech is perceived, then the primary visual cortex is first activated [3, p. 142]. Consequently, for the identification of graphic speech, the spelling representation of the word will be the base one, therefore, the formation of spelling representations of words in the mental lexicon of a person, that is, a good visual memory, will be the key to easy access to the lexical meaning of the word. But orthographic representations of words alone are not enough. The surface tier of the lexicon is subdivided into 2 sub-tiers: the sub-tier of graphic images and the sub-tier of sound (auditory) images. Researchers note that in the process of recognition of a graphic word, phonetic representation is activated almost immediately after the visual presentation of a graphic stimulus - within 60 ms [2, p. 110]. Experiments on the recognition of graphic speech have also recorded the presence of reduced speech movements [4, p. twenty]. Visually perceived words are "voiced"

110]. Experiments on the recognition of graphic speech have also recorded the presence of reduced speech movements [4, p. twenty]. Visually perceived words are "voiced"

in internal speech. Consequently, the understanding of a graphic word presupposes the presence in memory of other representations: kinesthetic and sound, and reading as a receptive type of speech activity is based on the activity of visual and auditory-speech-motor analyzers. At the same time, the leading analyzer is visual, the accompanying ones are speech and auditory. However, reliance on the phonetic image of a word is most distinct only at the first stages of mastering the ability to read, where for understanding it is necessary to correlate visual images of words with auditory-motor ones. The strengthening of mental connections between the visual image of the word and its meaning leads to a direct understanding of the graphic sign without correlation with the auditory image. When perceiving a foreign language text, such stability of the connections between words and their meanings makes it possible to read this text without translation.

From a methodological point of view, in order to understand written IT, it is necessary to teach students the following types of reading: viewing, introductory, studying [5].

Introduction to written IT begins with skimming reading aimed at the most general understanding of the text: an idea of its topic, main issues raised, etc. This type of reading provides an understanding of 10% of the content of the text, that is, factual information. For this, the semantic perception of only nouns in their main functions (subject and object) is sufficient. These units are the keywords of the text.

The role of a set of keywords is very important. In text linguistics, a set of keywords is considered as a minimal text. Each keyword, being a semantic milestone of the text, covers a part of the information space of the text. Thus, a set of keywords contains the main content of the text and has integrity and coherence. This is due to the strategy of the hemispheres of the brain. The integrity of the text is the result of the mechanism of perception of the object as a whole, and the coherence is the result of the mechanism of perception of the object by elements. Neurophysiological studies suggest that the keywords themselves are associated with the mechanisms of the right hemisphere responsible for the integrity of the text, and the ordering of keywords is provided by the mechanisms of the left hemisphere responsible for the coherence of the text. At the same time, keywords are usually arranged in sets in the same order in which they first appear in IT. This allows, by predicative addition of a set of keywords, to build a detailed text close to IT. These features of the set of keywords should be used when teaching translation, because the IT translation process can be interpreted as the deployment of a set of foreign language equivalents of its keywords.

The integrity of the text is the result of the mechanism of perception of the object as a whole, and the coherence is the result of the mechanism of perception of the object by elements. Neurophysiological studies suggest that the keywords themselves are associated with the mechanisms of the right hemisphere responsible for the integrity of the text, and the ordering of keywords is provided by the mechanisms of the left hemisphere responsible for the coherence of the text. At the same time, keywords are usually arranged in sets in the same order in which they first appear in IT. This allows, by predicative addition of a set of keywords, to build a detailed text close to IT. These features of the set of keywords should be used when teaching translation, because the IT translation process can be interpreted as the deployment of a set of foreign language equivalents of its keywords.

Introductory reading, or reading with a general scope of content, gives a deeper understanding of the text, providing an understanding of 70 - 75% of all its information. The purpose of this type of reading is to assimilate the general semantic content of the text without delving into the details and details. Therefore, during introductory reading, a selective approach to the information of the text is used, which implies the ability to highlight the main thing, to distinguish between primary and secondary information, the ability to guess the meaning of an unfamiliar word or grammatical phenomenon.

The purpose of this type of reading is to assimilate the general semantic content of the text without delving into the details and details. Therefore, during introductory reading, a selective approach to the information of the text is used, which implies the ability to highlight the main thing, to distinguish between primary and secondary information, the ability to guess the meaning of an unfamiliar word or grammatical phenomenon.

Learning reading is reading with the aim of understanding the text in all details and details of its semantic content. This type of reading provides understanding of 100% of the text information. This is how special literature is usually read, which is necessary for a person's professional activity [6; 7].

At the lessons devoted to the translation of the text, the first stage should be its viewing reading in order to form the primary image of IT. Then, introductory reading should follow, leading to the compilation of a generalized semantic image of IT. The final stage of working with IT is its studying reading, which provides the most accurate and complete understanding. At the last stage, the complication, addition and correction of the semantic image of the text takes place, that is, its formation is completed; on this basis, the choice of a strategy for the subsequent translation of the text is carried out [5]. Note that these types of reading and their sequence are important for both direct and reverse translation, however, all three types of reading are fully realized only when translating difficult and large foreign texts. When translating from a native language into a foreign language, all types of reading IT proceed much faster than when reading the original foreign text.

The final stage of working with IT is its studying reading, which provides the most accurate and complete understanding. At the last stage, the complication, addition and correction of the semantic image of the text takes place, that is, its formation is completed; on this basis, the choice of a strategy for the subsequent translation of the text is carried out [5]. Note that these types of reading and their sequence are important for both direct and reverse translation, however, all three types of reading are fully realized only when translating difficult and large foreign texts. When translating from a native language into a foreign language, all types of reading IT proceed much faster than when reading the original foreign text.

A complete understanding of IT is the basis for further translation action - the transfer of the extracted meaning by means of the target language. There are several psycholinguistic models of the speech generation process: the speech generation model of T. V. Ryabova, A.A. Leontiev, models of the process of verbal and mental activity A.A. Zalevskoy, I.A. Winter. Their analysis shows that when a statement is generated, the basic component is a certain concept, a semantic cluster of all elements of the future text, and the process of its generation is the deployment of this cluster of meaning, built taking into account the forecast of its perception. The content and connection of the text components is set in such a way as to provoke the necessary verbal-thinking actions of the addressee, "program" their sequence.

V. Ryabova, A.A. Leontiev, models of the process of verbal and mental activity A.A. Zalevskoy, I.A. Winter. Their analysis shows that when a statement is generated, the basic component is a certain concept, a semantic cluster of all elements of the future text, and the process of its generation is the deployment of this cluster of meaning, built taking into account the forecast of its perception. The content and connection of the text components is set in such a way as to provoke the necessary verbal-thinking actions of the addressee, "program" their sequence.

The generation of a translated text (hereinafter referred to as PT) has a specificity due to its secondary nature: the meaning and program for the generation of this text are given to the translator. The idea of Pt is that semantic image of IT, which has developed in the mind of the translator as a result of the semantic perception of the latter. If we consider the generation of a TP as a chain "intent - text", then this process can be recognized as productive, as well as the process of generating any written statement. However, the fact that the intent of a TP is not the translator's own intent, but is embedded in the IT, as well as its form expressions, transfers the process of generating a TP into the category of productive-reproductive.It seems that this process cannot be considered completely reproductive, since the translator creates a full-fledged written text, and the need to use another language inevitably leads to some change in the original.0003

However, the fact that the intent of a TP is not the translator's own intent, but is embedded in the IT, as well as its form expressions, transfers the process of generating a TP into the category of productive-reproductive.It seems that this process cannot be considered completely reproductive, since the translator creates a full-fledged written text, and the need to use another language inevitably leads to some change in the original.0003

The predetermination of the concept of the future TP can lead to difficulties in its implementation, since the concept of one person may not correspond to the ability to form and formulate it in another person (translator). Therefore, if in all other types of speech activity the formation and formulation of thoughts is carried out, then reformulation is also carried out in translation. By reformulation, we understand both code transitions from written speech to inner speech and subject-scheme code, as well as the transition from one language to another, that is, reformulation of the idea according to the laws of the target language.

As a rule, students of non-linguistic universities do not speak a foreign language well enough, so it is necessary to dwell on the sequence of translation actions in a situation of imperfect language proficiency. Under these conditions, the functioning of these speech mechanisms is mediated by the native language, which can have a negative impact. The probability of interference is especially high when translating from a native language into a foreign one. In this case, understanding IT for a specialist in the subject area to which the text belongs does not cause difficulties. However, the lack of strong links between the units of the native and foreign languages does not allow the formation of the meaning of IT and the design of the TP in the target language. Both of these mental actions take place in the native language, and reformulation, that is, the moment of switching from one language to another, occurs only at the stage of generating the TP. Consequently, here we are faced with "translation in translation": first, an understanding of linguistic signs arises, and the resulting image is associated with the native language, since it is the signs of the native language that are most firmly connected with the concepts; then this concept, built according to the laws of the native language, is encoded in the target language This causes numerous errors in students' translations. When translating from a foreign language into a native language, the formation of the meaning of IT and the design of the TP is carried out in the native language, in which the TP is then formulated.However, in order to reformulate the source language into the target language at the stage of comprehending the presence of strong links between foreign language units and concepts, otherwise deciphering IT words is possible only with the help of a dictionary.Thus, if when translating from a native language into a foreign language, the main difficulty is the last stage - the stage of formulating a formed thought in the target language, then when translating from a foreign language on native OS Particularly difficult is the first stage - the stage of understanding IT. The solution to these problems is the same for both cases: the formation of the skill of switching from one language to another, that is, the establishment of strong links between lexical units or grammatical structures of the native and foreign languages in the unity of their forms and meanings.

When translating from a foreign language into a native language, the formation of the meaning of IT and the design of the TP is carried out in the native language, in which the TP is then formulated.However, in order to reformulate the source language into the target language at the stage of comprehending the presence of strong links between foreign language units and concepts, otherwise deciphering IT words is possible only with the help of a dictionary.Thus, if when translating from a native language into a foreign language, the main difficulty is the last stage - the stage of formulating a formed thought in the target language, then when translating from a foreign language on native OS Particularly difficult is the first stage - the stage of understanding IT. The solution to these problems is the same for both cases: the formation of the skill of switching from one language to another, that is, the establishment of strong links between lexical units or grammatical structures of the native and foreign languages in the unity of their forms and meanings.

When reading, these connections are manifested in the free semantic perception of graphic images of linguistic phenomena, while generating PT (writing) - in the automatic correct lexico-grammatical formulation of the statement in the graphic code.

When generating an utterance, the knowledge of syntactic rules is of particular importance. Researcher T.N. Ushakova believes that the process of text deployment can be explained on the basis of the concept of dynamic stereotypy in the second signal system. T.N. Ushakova identifies the so-called "syntactic stereotype", the result of which is the sequential activation of functional nervous structures that fix generalized grammatical meanings. The formation of syntactic stereotypes should occur as a result of multiple perception of sentences of the same type. In other words, the constant repetition of the “pattern” of excitation of nervous formations corresponding to grammatical generalizations should result in the emergence of an internally coordinated system. Such functional systems T.N. Ushakov and calls it syntactic dynamic stereotypes. They play an important role in the speech process when constructing sentences and understanding perceived phrases, being their “backbone”, which can be implemented in the statement after activation in the second signal system of the basic elements corresponding to the meaningful words of the future speech. Variation of specific words in a sentence does not interfere with the formation of a stereotype because each specific word has a generalized grammatical design and meaning [8, p. 190 - 192].

Such functional systems T.N. Ushakov and calls it syntactic dynamic stereotypes. They play an important role in the speech process when constructing sentences and understanding perceived phrases, being their “backbone”, which can be implemented in the statement after activation in the second signal system of the basic elements corresponding to the meaningful words of the future speech. Variation of specific words in a sentence does not interfere with the formation of a stereotype because each specific word has a generalized grammatical design and meaning [8, p. 190 - 192].

The choice of specific word forms when constructing a phrase is as follows. As a result of the generalizing and classifying work of the nervous system, a system of secondary signal structures is created that corresponds to the morpheme system of the language. The basic elements are connected in thinking, forming a verbal network. When choosing a word, diffuse foci of excitation are localized in the second signal system, covering, in particular, functional structures that fix word paradigms. These foci cannot be directly translated into speech. In order for an isolated structure corresponding to a single word to be singled out from them, a differentiating process must occur. At the moment of constructing a phrase, the form of a word (for example, a noun in a certain case) is formed each time anew by combining the root morpheme and the ending. The result is a connected sentence. We believe that such a mechanism for generating a sentence is applicable to speech activity in both native and foreign languages.

These foci cannot be directly translated into speech. In order for an isolated structure corresponding to a single word to be singled out from them, a differentiating process must occur. At the moment of constructing a phrase, the form of a word (for example, a noun in a certain case) is formed each time anew by combining the root morpheme and the ending. The result is a connected sentence. We believe that such a mechanism for generating a sentence is applicable to speech activity in both native and foreign languages.

When writing, as well as when reading, hidden articulation is carried out, that is, silent, reduced internal pronunciation, the intensity of which depends on the degree of automation of the writing technique and the difficulty of the text. Consequently, when writing, complex connections of motor, speech-motor-auditory and visual-graphic images of phenomena are actualized in unity with their meaning, while the leading analyzer here is motor, accompanying - visual, speech-motor and auditory. Thus, the written utterance program is realized in internal pronunciation with the leading role of the auditory analyzer and, to a lesser extent, speech-motor (reduced articulation), and then is fixed in the form of a written text according to the syntax rules of the desired language, that is, there is a transition to the graphic code.

Thus, the written utterance program is realized in internal pronunciation with the leading role of the auditory analyzer and, to a lesser extent, speech-motor (reduced articulation), and then is fixed in the form of a written text according to the syntax rules of the desired language, that is, there is a transition to the graphic code.

It can be concluded that the perception and generation of speech have similar mechanisms. Writing is a reverse process, but in many ways similar to reading, therefore, when teaching visual-written translation, reading and writing must be considered in close relationship as different forms of a single speech activity.

1. Klychnikova Z.I. Psychological features of perception and understanding of written speech (psychology of reading): Abstract of the dissertation ... doctor of psychological sciences. Moscow, 1975.

2. Psycholinguistic problems of the functioning of the word in the human lexicon (under the editorship of A.A. Zalevskaya). Tver: Tver State University, 1999.

Tver: Tver State University, 1999.

3. Fundamentals of human physiology. Edited by N.A. Agadzhanyan. Moscow: Peoples' Friendship University Press, 2000.

4. Burlakov Yu.A. Physiological characteristics of the formation of speech skills and abilities. Moscow: MGU Publishing House, 1985.

5. Kondrashova N.V. Teaching translation to senior students of the Faculty of Fine Arts of a Pedagogical University (based on the German language). Dissertation ... Candidate of Pedagogical Sciences. St. Petersburg, 2002.

6. Folomkina S.K. Dependence of the types of exercises on the types of reading M. Torez, 1970.

7. Krelenshtein N.S. Types of reading and levels of text compression Teaching scientists foreign languages. Moscow: Nauka, 1984.

8. Ushakova T.N. Functional structures of the second signal system: Psychophysiological mechanisms of inner speech. Moscow: Science, 1979.

References

1. Klychnikova Z.I. Psihologicheskie osobennosti vospriyatiya i ponimaniya pis'mennoj rechi (psihologiya chteniya): Avtoreferat dissertacii . .. doktora psihologicheskih nauk. Moskva, 1975.

.. doktora psihologicheskih nauk. Moskva, 1975.

Tver': Tverskoj gosudarstvennyj universitet, 1999.

3. Osnovy fiziologii cheloveka. Edited by N.A. Agadzhanyana. Moscow: Publishing house Universiteta druzhby narodov, 2000.

4. Burlakov Yu.A. Fiziologicheskaya harakteristika formirovaniya rechevyh navykoviumenij. Moscow: Publishing house MGU, 1985.

5. Kondrashova N.V. Obuchenieperevodu studentovstarshih kursov fakul'teta izobrazitel'nogo iskusstva pedagogicheskogo vuza (na materiale nemeckogo yazyka). Dissertaciya ... kandidata pedagogicheskih nauk. Sankt-Peterburg, 2002.

6. Folomkina S.K. Zavisimost' tipov uprazhnenij ot vidov chteniya Metodicheskie zapiski po voprosam prepodavaniya inostrannyh yazykov v vuze (Problemnye voprosy obucheniya chteniyu) Moscow: MGPIIYa im. M. Toreza, 1970.

7. Krelenshtejn N.S. Vidy chteniya i urovni kompressii teksta Obuchenie nauchnyh rabotnikovinostrannym yazykam. Moscow: Nauka, 1984.

8. Ushakova T. N. Funkcional'nye struktury vtoroj signal'noj sistemy: Psihofiziologicheskie mehanizmy vnutrennejrechi. Moskva: Nauka, 1979.

N. Funkcional'nye struktury vtoroj signal'noj sistemy: Psihofiziologicheskie mehanizmy vnutrennejrechi. Moskva: Nauka, 1979.

Received September 26, 2016

UDC 378:316.77

Martynova Ye.V., Cand. of Sciences (Pedagogy), senior lecturer, Kemerovo State University of Culture (Kemerovo, Russia), E-mail: [email protected]

Sorokina V.V., Deputy Director for Educational and Methodical Work, teacher of Russian language and literature, Gymnasium No. 25 (Kemerovo, Russia), E-mail: [email protected]

Sherbinin A.A., translator, member of the Union of Translators of Russia, English instructor, Secondary School No. 16 (Kemerovo, Russia), E-mail: [email protected]

FORMATION OF INCLINATION TO COMPILATION OF RUSSIAN AND ENGLISH ANALYTICAL TEXTS BY STUDENTS AND PUPILS. The article highlights many years of research and teaching experience in the formation of inclination of learners to the compilation of analytical texts on different levels of education: school and university. The study is conducted in Kemerovo State University of Culture at the Department of Documentary Communications Technology. The disclosure of analytical texts specificity includes the fol-

The study is conducted in Kemerovo State University of Culture at the Department of Documentary Communications Technology. The disclosure of analytical texts specificity includes the fol-

Teaching children to read and write

Submitted by Ilya Danshyn on Mon, 11/15/2021 - 14:31

Learning to read and write

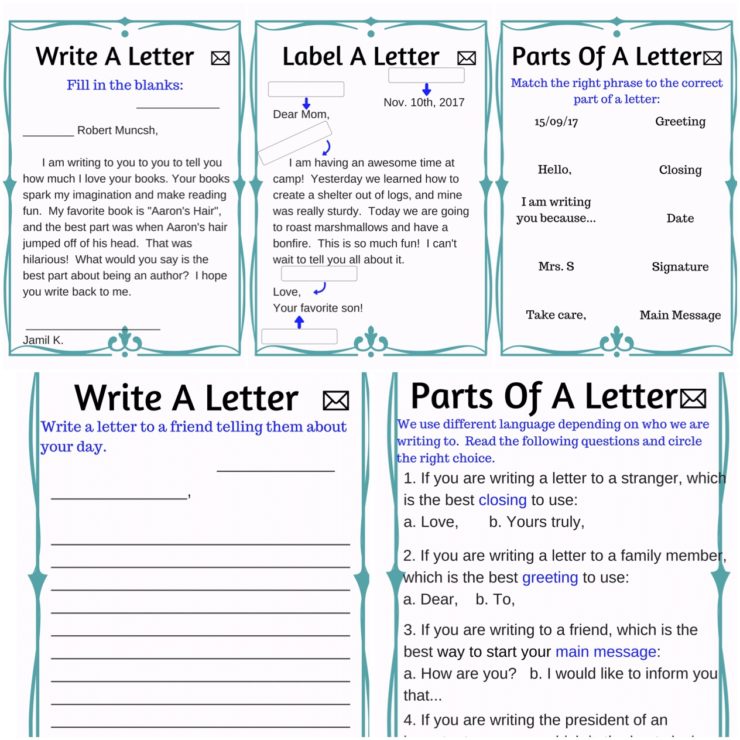

Talking, singing, playing with sounds and words, reading, writing and drawing with your child are all great ways to create a good foundation for your child to read and write in the future.

Regular daily activities at home or occasional activities in bookstores or libraries are all excellent opportunities for children to learn to read and write.

And You don't need much time to practice reading and writing with your child - just five minutes is enough several times a day. The key is to do it at different times and use different opportunities to help your child learn. It can be the simplest activity, such as making a shopping list, playing rhymes, or reading fairy tales before bed.

It's never too early to involve your child in activities that will teach him to read and write - even babies love to hear stories and engage in conversation. The following are activities for children of all ages. If you have several young children of different ages, you can combine or change activities according to their interests and skills.

Infants, Toddlers and Preschoolers: Teaching Reading and Writing

Communication and Singing

Communication and singing with young children helps them develop listening and speaking skills. Here are some ideas to get you started:

- Use rhyme when you get it right. Use phrases such as “a gray top will come and bite on the flank”, or compose meaningless rhymes about what you are doing, for example: “I will prepare such beauty for the cat.”

- Sing traditional nursery rhymes to your child. Thanks to them, the baby begins to understand what language, rhyme, repetition and rhythm are.

Think back to something you heard as a child, no matter what language.

Think back to something you heard as a child, no matter what language. - If you have a baby, repeat the sounds he makes, or make up sounds and see if he can repeat them. For example: “Cows say “mu-u-u-u”. Can you say "moo-o-o-o"?

- As you eat, talk about the meals you've cooked, what you've done with the food, how the food tastes and looks.

- Talk about what's going on outside: how the leaves rustle, the birds sing, or the noise of the cars. Ask your child if they can imitate the sounds that wind, rain, water, planes, trains, and cars make.

- Play "I am a Spy" to guess colors. This can be a lot of fun, especially for preschoolers. For example: “I am a spy, and I look secretly and see something green. What green can I look at?

Reading and studying with books

Even for toddlers, reading aloud develops vocabulary, listening and understanding skills, and forms the basis for further development of the ability to connect sounds and words. Your child may like:

Your child may like:

- Read books that have rhyme, rhythm and repetition.

- Turn the pages and talk about what he sees (for preschool children). To guide your child's gaze, slide your finger from left to right across the page as you read and point to specific words or phrases. It is important that the child has fun.

- Flipping through books with windows that open or books that are fun to touch and feel - this activity will be especially appreciated by toddlers. Such books will help satisfy the need of toddlers to touch and explore. You can even make your own book with items your child loves to look at and touch.

- Read stories interactively. Ask, for example: “What do you think will happen next?” or “Remember when we were on the bus?”

- Correlate what is told in books with real life. For example, if you have read a book about games under a tree, you can take the child to the yard, sit it under the tree, show the leaves and branches, and play as described in the book.

- Do what you read about. For example, ask him to jump like a kangaroo from a book.

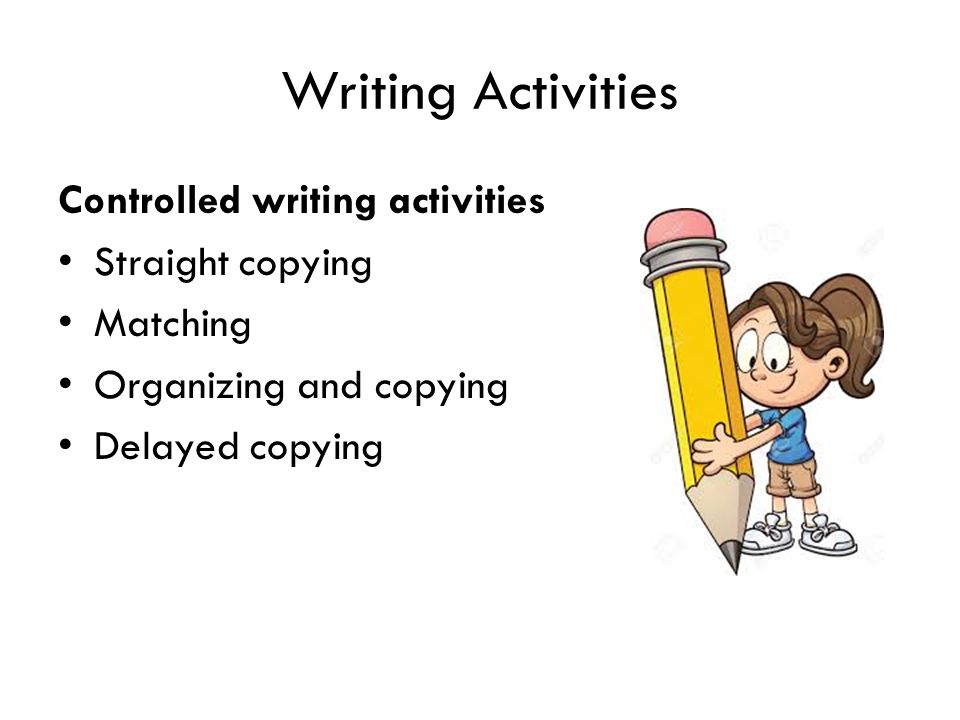

Drawing and Writing Activities

Scribble writing and drawing help young children practice the skills they will need later to develop writing skills with pencils and pens. Toddlers and preschoolers can do the following:

- Draw and write with pens, pencils, crayons and markers. The kid will definitely want to add his own inscriptions or a bright multi-colored drawing to greeting cards or letters.

- Write some letters or your name on all the drawings the child has made: write the letters in one color and have the child circle them in another color.

- Make letters of the alphabet or numbers from salt dough or plasticine.

- Use the letters of the alphabet in a variety of forms - on cubes, puzzle pieces, and magnetic letters that can be hung on a refrigerator or board.

- Cut or draw the main household items (chair, table, TV, wall, door, etc.

), then write their names on separate small pieces of paper. Ask your child to match the name of the object with its image.

), then write their names on separate small pieces of paper. Ask your child to match the name of the object with its image. - Encourage the child to talk about their drawings. Help your child write down the words he uses to describe them.

Senior preschool children: additional classes for learning to read and write

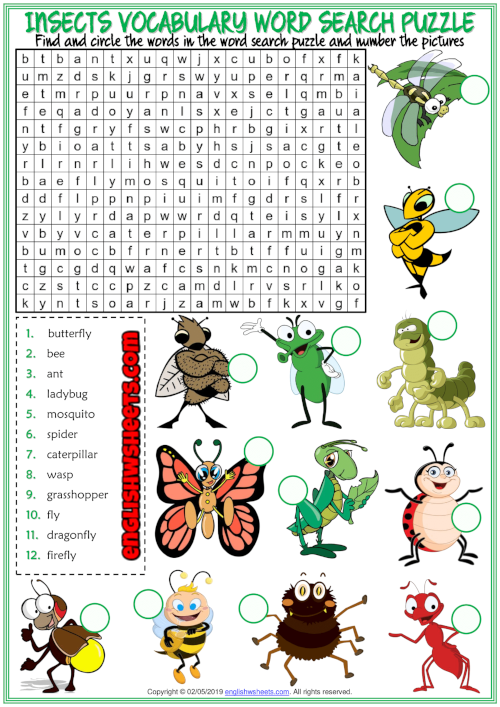

In addition to those already listed, as school gets closer and if your child is interested, you can try the following activities: - thanks to such games, your child learns sounds. For example: “I will think of something that starts with “m”. What do you think I'm looking at that starts with that letter?"

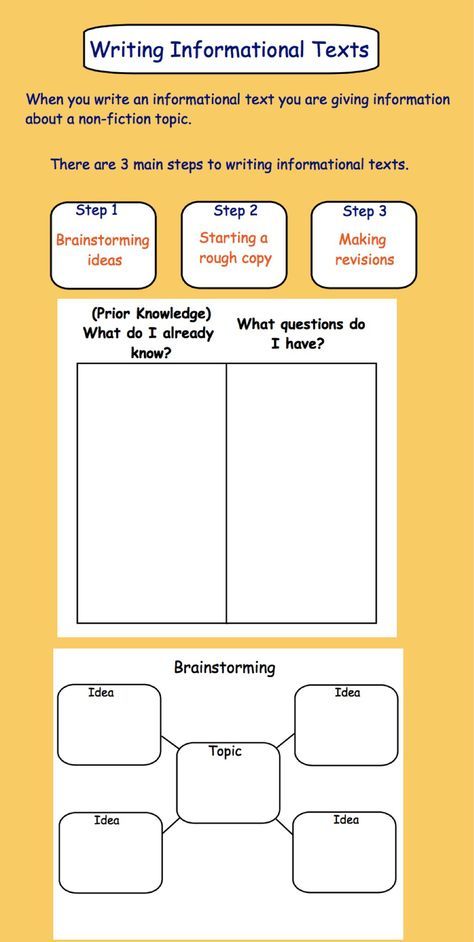

Ask your child to tell you about what they enjoyed doing in kindergarten this week. Sometimes you can write down what the child says.

Ask your child to tell you about what they enjoyed doing in kindergarten this week. Sometimes you can write down what the child says. Reading and activities using books

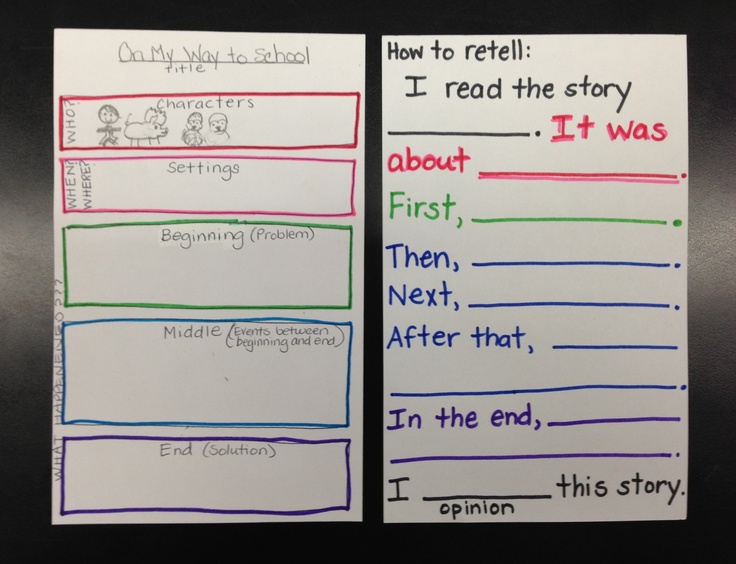

- Read and talk about fairy tales. Ask the child: "What was the story about?" or “Did you like this character? Why?"

- Older children love alphabet books. Ask your child to name words that begin with the same sound as the letter you point to.

- Invite the child to make a story book with his own pictures. With your help, he can do this on a computer or using pencils and paper. If the child is interested, help him write at least a few letters in the story.

- While walking or shopping, ask your child to choose or name certain letters or words on billboards, shop signs, road signs, or supermarket merchandise.

Learn more