What are the first sight words to teach

A New Model for Teaching High-Frequency Words

We have visited many schools to observe intervention lessons and core reading instruction. For years we have been struck that even schools embracing research-based reading instruction teach high-frequency words through rote memorization. It is as if the high-frequency words are a special set of words that need to be memorized and can’t be learned using sound–symbol relationships.

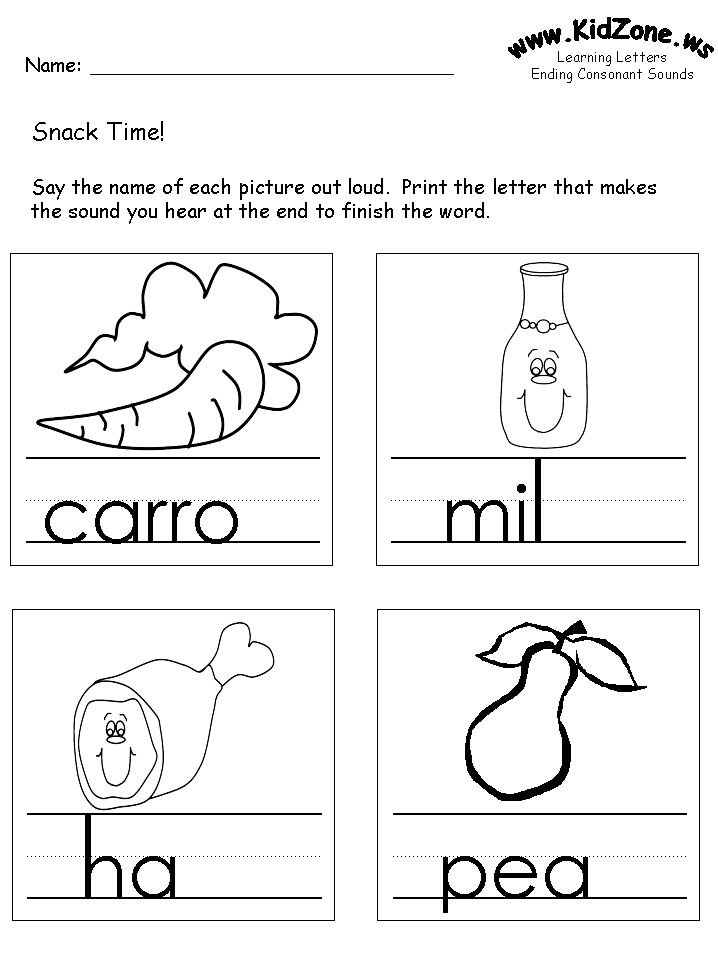

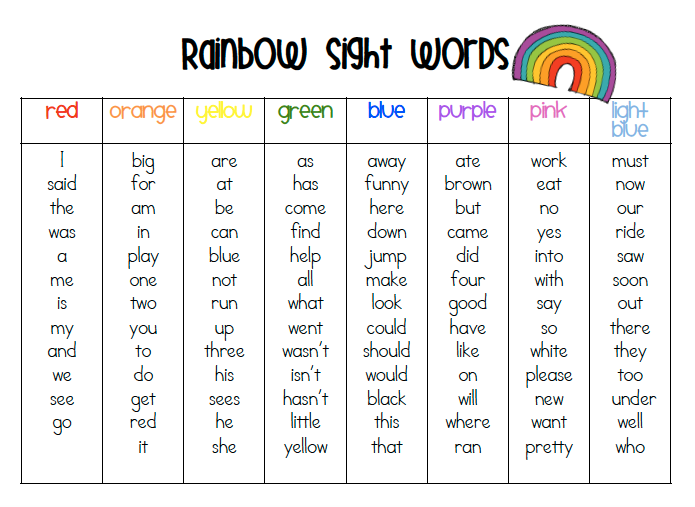

A number of years ago, a teacher we respect enormously asked for help because many of her Tier 2 students and all of her Tier 3 students in first and second grades were failing to learn high-frequency words, even though they were progressing in their phonics lessons. We observed her teaching the digraph

th to a group of four Tier 3 first grade students. This lesson was in April. Her students had learned to read CVC words and this was their first lesson with digraphs. The high-frequency words the students were responsible for knowing in this lesson were the color words: blue, red, yellow, orange, purple, and green. None of the four students could spell more than two of the words accurately. All four students had difficulty reading those words when they were mixed into lists with other high-frequency words. (Indeed, they were having difficulty reading all the high-frequency words in the lists.)

These students could read words that followed spelling patterns they had learned and practiced, but they struggled learning words that made no sense to them from a sound–spelling viewpoint. We suggested that the students learn high-frequency words according to spelling patterns, and not according to frequency number or theme.

Together with the teacher, we organized the high-frequency words to fit into the phonics lessons so that the words were tied to spelling patterns students were learning. First, we focused on identifying decodable high-frequency words such as but, him, and yes and integrating them into phonics lessons instead of teaching them as words that had to be memorized. Next, we identified irregularly spelled high-frequency words such as

said, you, and from. These words have two or three letter sounds students knew and only one or two letters that had to be memorized. We integrated 2 or 3 of these words into a phonics lessons, and students learned to identify the letters spelled as expected and to learn “by heart” the letters not spelled as expected.

Next, we identified irregularly spelled high-frequency words such as

said, you, and from. These words have two or three letter sounds students knew and only one or two letters that had to be memorized. We integrated 2 or 3 of these words into a phonics lessons, and students learned to identify the letters spelled as expected and to learn “by heart” the letters not spelled as expected.

With this approach, students had an easier time learning to read the word said because they knew that only the letters ai are an unexpected spelling. Students also soon stopped confusing was and saw because they learned to think about the first sound before reading or spelling those words. The teacher told us that she, her students, and their parents were thrilled that they were no longer “banging their heads against the wall” going over and over the words as students tried to memorize how to read or spell high-frequency words with little success.

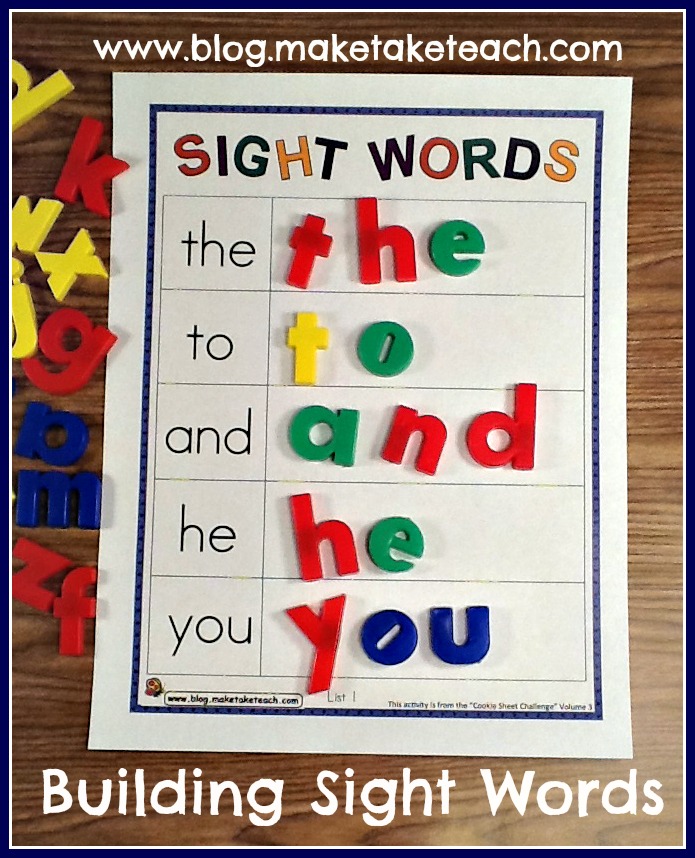

Current practices

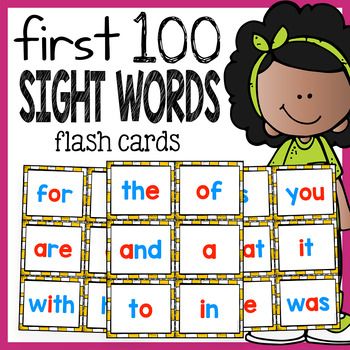

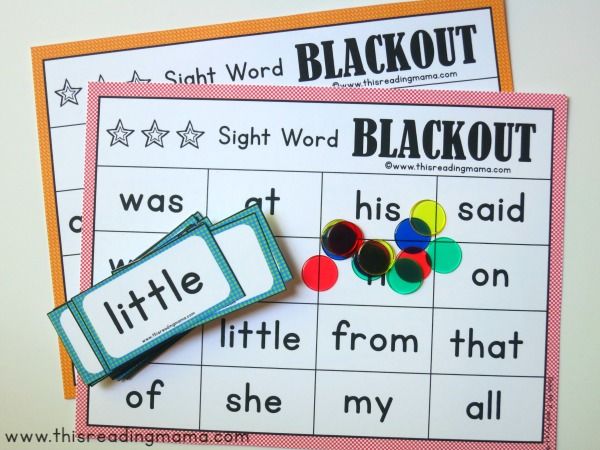

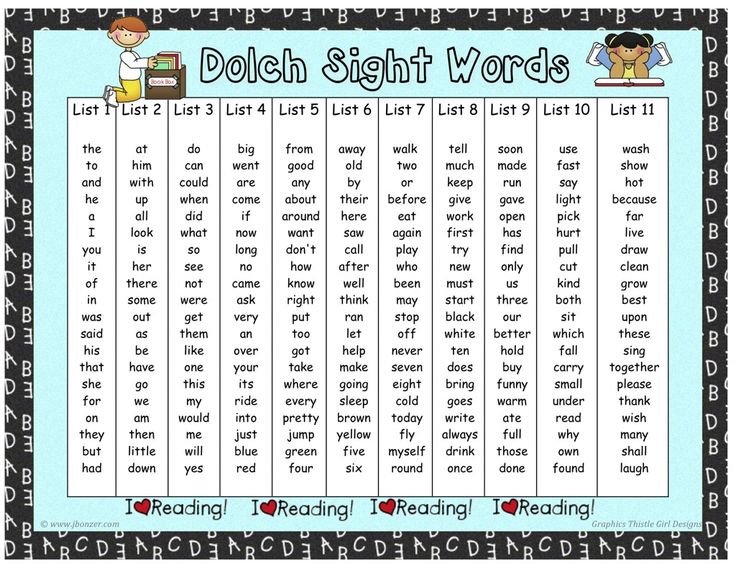

High-frequency words are often referred to as “sight words”, a term that usually reflects the practice of learning the words through memorization. These words might be on the Dolch List, Fry Instant Words, or selected from stories in the reading program. Common practice often includes sending these “sight words” home for students to study and memorize, or drilling with flash cards in school. Students may start with word #1 and progress through the words in the order of frequency. Some teachers, like our friend above, group the words in categories, such as numbers or colors, whenever possible. In essence, high-frequency word instruction is often fully divorced from phonics instruction. While this method works for many students, it is an abysmal failure with others.

These words might be on the Dolch List, Fry Instant Words, or selected from stories in the reading program. Common practice often includes sending these “sight words” home for students to study and memorize, or drilling with flash cards in school. Students may start with word #1 and progress through the words in the order of frequency. Some teachers, like our friend above, group the words in categories, such as numbers or colors, whenever possible. In essence, high-frequency word instruction is often fully divorced from phonics instruction. While this method works for many students, it is an abysmal failure with others.

Overview of suggested restructuring

Integrating high-frequency words into phonics lessons allows students to make sense of spelling patterns for these words. To do this, high-frequency words need to be categorized according to whether they are spelled entirely regularly or not. Restructuring the way high-frequency words are taught makes reading and spelling the words more accessible to all students. The rest of this article describes how to “rethink” teaching of high-frequency words and fit them into phonics lessons.

The rest of this article describes how to “rethink” teaching of high-frequency words and fit them into phonics lessons.

Teach 10–15 “sight words” before phonics instruction begins

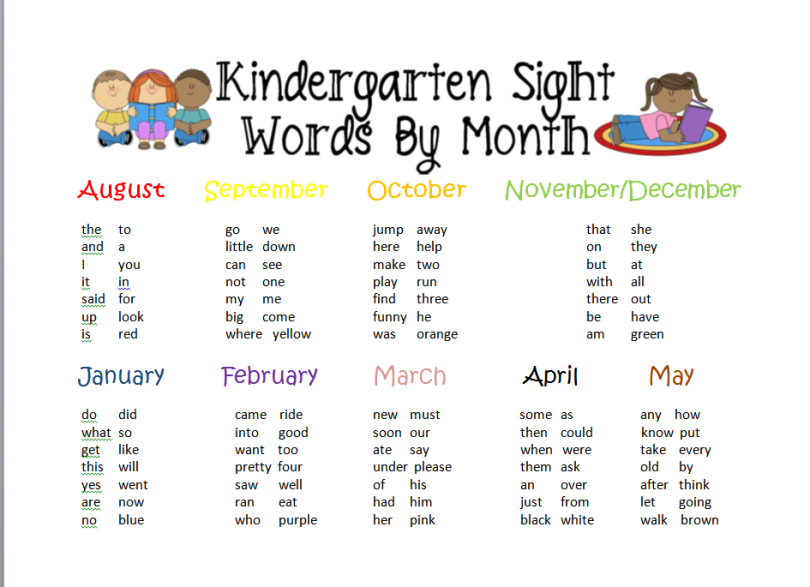

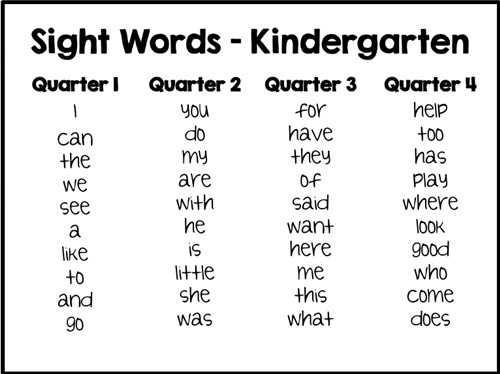

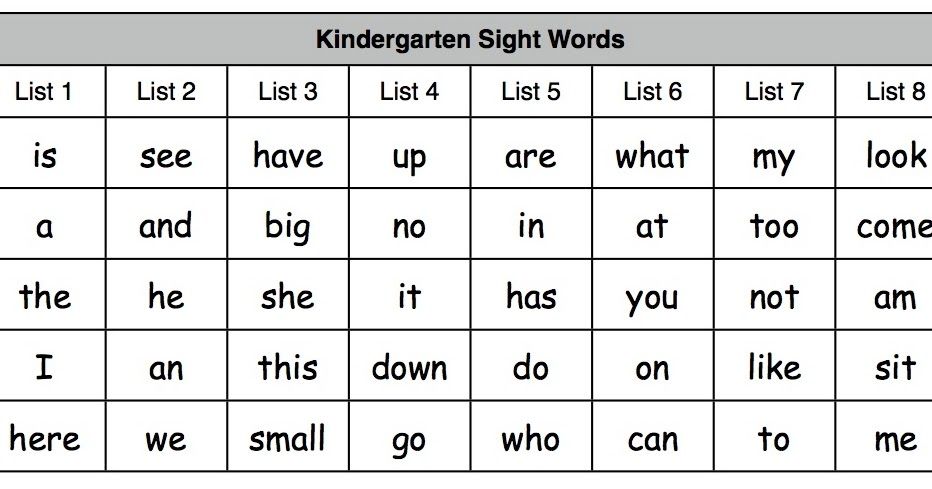

Many kindergarten students are expected to learn 20 to 50, or even more, high-frequency words during the year. The words are introduced and practiced in class and students are asked to study them at home. Learning these “sight words” often starts before formal phonics instruction begins.

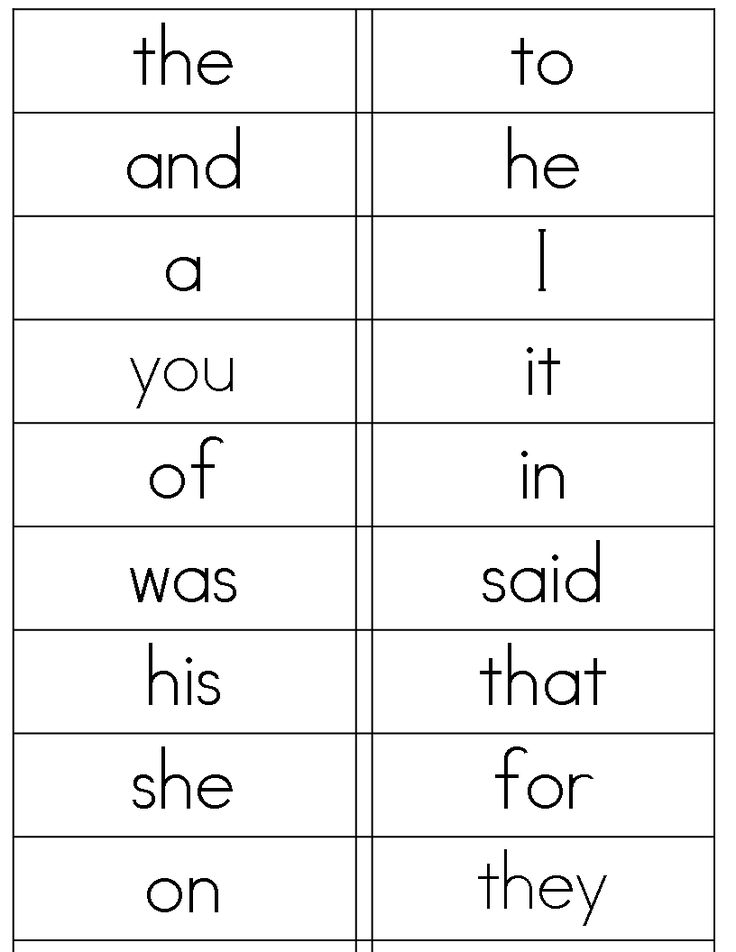

Children do need to know about 10–15 very-high-frequency words when they start phonics instruction. However, these words can be carefully selected so that they are the “essential words” that are not decodable when the short vowel patterns VC and CVC are taught. Words such as at, can, and had are easier for students to learn using phonics than by simply memorizing them.

We recommend teaching 10–15 pre‐reading high-frequency words only after students know all the letter names, but before they start phonics instruction. (Students who have not learned their letter names inevitable struggle to learn words that have letters they cannot identify.) Teaching students to read the ten words in Table 1 as “sight words” even before they begin phonics instruction is unlikely to overburden even “at risk” students. These ten words can be used to write decodable sentences when phonics instruction begins. The words in Table 1 are suggestions only, and teachers may revise or add words based on their reading materials and their students. For example, the words

are and said are often added.

(Students who have not learned their letter names inevitable struggle to learn words that have letters they cannot identify.) Teaching students to read the ten words in Table 1 as “sight words” even before they begin phonics instruction is unlikely to overburden even “at risk” students. These ten words can be used to write decodable sentences when phonics instruction begins. The words in Table 1 are suggestions only, and teachers may revise or add words based on their reading materials and their students. For example, the words

are and said are often added.

To teach these ten pre-reading sight words, we recommend introducing one word at a time. Teaching these words in the order listed can minimize confusion for students. For example, the and a are unlikely to be confused, as are I and to. However, to and of are widely separated on the table because both are two-letter words with the letter o, and t and f have similar formations.

As we recommended above, the words in Table 1 should not be taught or practiced until a student knows all the letter names.

Students can demonstrate they know these words in a number of ways, including (1) finding the word in a list or row of other words, (2) finding the word in a text, (3) reading the word from a card, and (4) spelling the word.

If students know letter sounds and can identify the first sound in a word, the following words can be tied to beginning letter sounds because the initial sound is spelled as expected: to, and, was, you, for, is. The word I is easily recognized by students who know their letter names. On the other hand, the words the, a, and of cannot be tied to known letter sounds.

Teaching a “ditty” to help students learn the, a, and of works for many students. Teachers have had success teaching students to sing the ditties below. It is important that students have the word in front of them when they say the ditty. They should point to the word when they say it in the ditty, and point to the letters when they say them in the ditty.

They should point to the word when they say it in the ditty, and point to the letters when they say them in the ditty.

- The: I can say ‘thee’ or I can say ‘thuh’, but I always spell it ‘t’ ‘h’ ‘e’

- A: I can say ‘ā’ or I can say ‘uh’, but I always spell it with the letter ‘a’

- Of is hard to spell, but not for me. I love to spell of. ‘o’ ‘f’ of, ‘o’ ‘f’ of, ‘o’ ‘f’ of

Table 1: 10 Sight Words for Pre-Readers to Learn

| Word | Dolch Frequency Rank | Fry Frequency Rank |

|---|---|---|

| the | 1 | 1 |

| a | 5 | 4 |

| I | 6 | 20 |

| to | 2 | 5 |

| and | 3 | 3 |

| was | 11 | 12 |

| for | 16 | 13 |

| you | 7 | 8 |

| is | 22 | 7 |

| of | 9 | 2 |

Dolch words are from: Dolch, E. W. (1936). A basic sight vocabulary. The Elementary School Journal, 36(6), 456-460.

W. (1936). A basic sight vocabulary. The Elementary School Journal, 36(6), 456-460.

Dolch Rankings were found on lists at K12 Reader and Mrs. Perkins Dolch Words.

Fry words and rankings are from: Fry, E., & Kress, J.K. (2006). The Reading Teacher’s Book of Lists. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco.

Flash Words and Heart Words defined

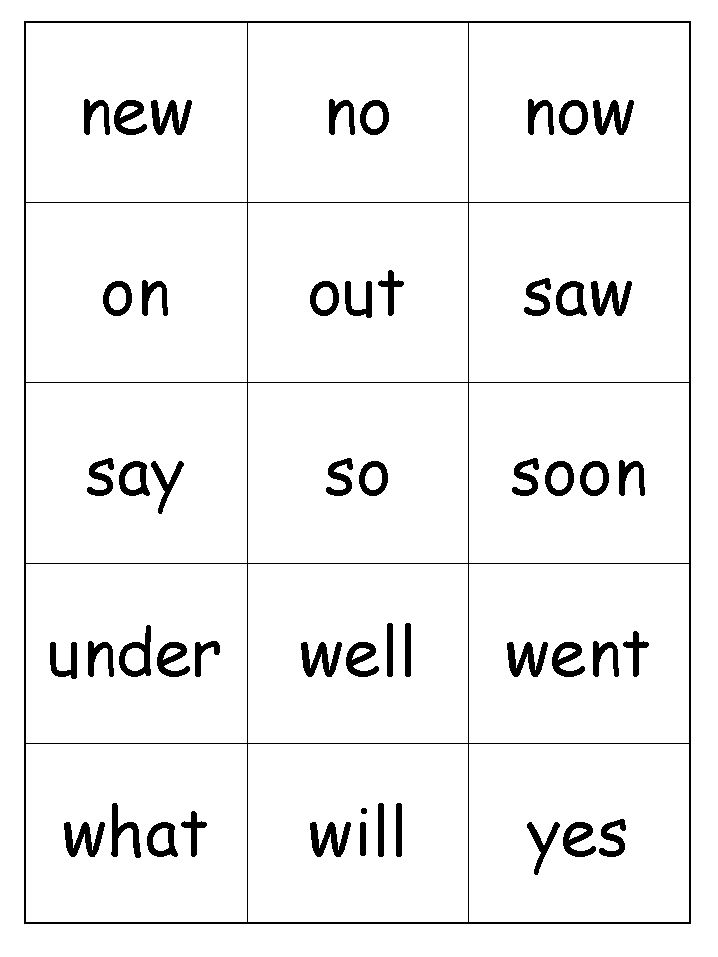

For instructional purposes, high-frequency words can be divided into two categories: those that are phonetically decodable and those with irregular spellings. We call high-frequency words that are regularly spelled and thus decodable “Flash Words”.

Although their spelling patterns are easily decoded, Flash Words are used so frequently in reading and writing that students need to be able to read and spell them “in a flash”. Examples of Flash Words at the cvc level are can, not, and did. Irregularly spelled words are called “Heart Words” because some part of the word will have to be “learned by heart.” Heart Words are also used so frequently that they need to be read and spelled automatically. Examples of Heart Words are: said, are, and where.

Examples of Heart Words are: said, are, and where.

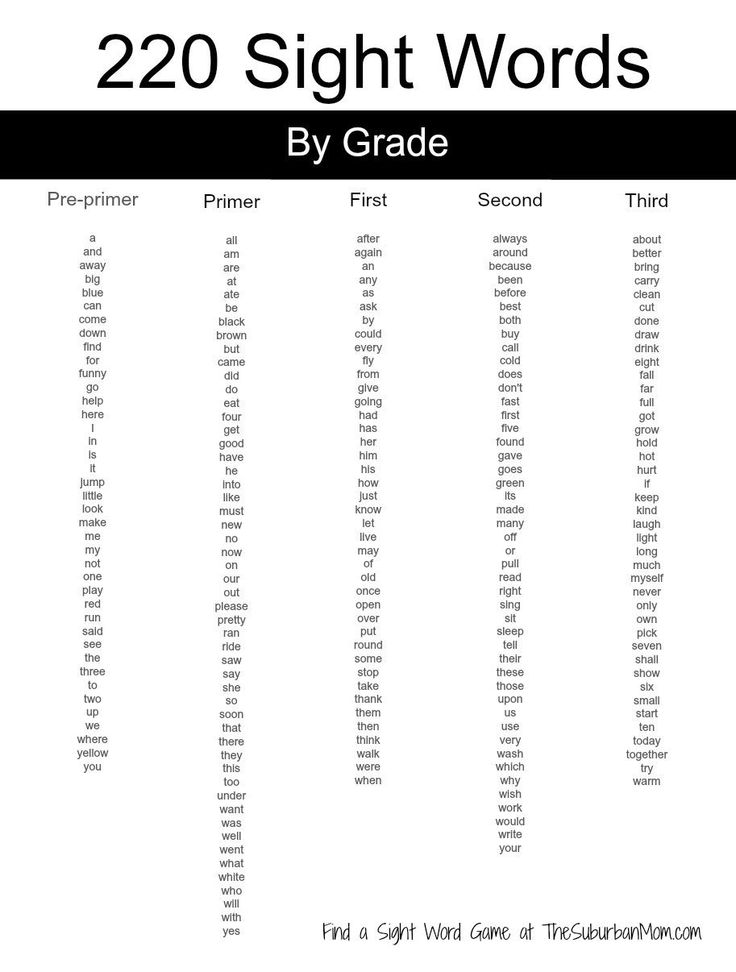

Words on any high-frequency word list can easily be categorized into Flash Words and Heart Words. However, be cautioned that a word may change categories. For example, early in a phonics scope and sequence, see may be a Heart Word because the long e spelling patterns haven’t been taught. When students learn that ee spells long e, see becomes a Flash Word. Further, many of the Heart Words can be categorized into words with similar spellings. This article categorizes words on the Dolch List of 220 High Frequency Words (Dolch 220 List)1. The method we use to categorize words on the Dolch 220 List works with any high-frequency word list.

Flash Words

One hundred and thirty-eight words (63%) on the Dolch 220 List are decodable when all regular spelling patterns are considered. Tables 2A, 2B, and 2C show the 138 decodable words categorized by spelling patterns. These tables can help teachers determine when to introduce the words during phonics lessons. Table 2A may be most useful for teachers of beginning reading because it lists the 60 one-syllable decodable words with the short vowel spelling pattern.

These tables can help teachers determine when to introduce the words during phonics lessons. Table 2A may be most useful for teachers of beginning reading because it lists the 60 one-syllable decodable words with the short vowel spelling pattern.

Table 2A: Flash Words (Decodable Words)

60 One-Syllable Words with Short Vowel Spelling Patterns

(Numbers in parentheses are the Dolch frequency ranking)

| VC | CVC | Digraphs | Blends | Words Ending in NG and N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Sorted by vowel spelling) | (Sorted by vowel spelling) | (Sorted by digraph) | (Sorted by ending blends, then beginning blends) | (Sorted by ending letters) |

| at (21) | had (20) hot (203) | that (14) | and (3) | sing (213) |

| am (37) | can (42) but (19) | with (23) | just (78) | bring (155) |

| an (72) | ran (111) run (163) | then (38) | must (149) | long (167) |

| it (8) | him (22) cut (188) | them (52) | fast (182) | thank (216) |

| in (10) | did (45) get (51) | this (55) | best (210) | think (110) |

| if (65) | will* (59) yes (60) | much (142) | went (62) | drink (159) |

| on (17) | big (61) red (80) | pick (185) | ask (70) | |

| off* (132) | six (120) well* (109) | wish (217) | its (75) | |

| up (24) | sit (191) let (112) | when (44) | jump (98) | |

| us (169) | not (49) tell (141) | which (192) | help (113) | |

| got (93) ten (153) | stop (131) | |||

| black (151) |

*Students easily understand that two consonants at the end of a word spell one sound.

1The source for words on the Dolch 220 List is: Dolch, E. W. (1936). A basic sight vocabulary. The Elementary School Journal, 36(6), 456-460. Tables in this article show frequency rankings for words on the Dolch 220 list. Rankings for words on the Dolch 220 List can be found in many places, but we did not find a primary source that can be attributable to Dr. Dolch.

Rankings were retrieved on March 15, 2013, from K12 Reader and Mrs. Perkins Dolch Words.

Flash Words that can be taught with spellings students know will vary at any given time, depending on which phonics patterns students have been taught. For example, the words had, am, and can will be decodable when students have learned short a and vc and cvc spelling patterns. That, when, pick, and much will be decodable after students learn digraphs and can read words with digraphs. The words just, went, black, and ask will be decodable when students learn to read words with blends.

Flash Words should be introduced when they fit into the phonics pattern being taught, which is different from teaching them based on their frequency of use. Flash Words are different from other decodable words only because of their frequency. They are called Flash Words because students will need lots of practice to read and spell these words “in a Flash”. These are called “Flash Words” instead of “sight words” because students do not have to memorize any part of Flash Words. They can use their knowledge of phonics patterns to read and spell the words.

Flash Words are different from other decodable words only because of their frequency. They are called Flash Words because students will need lots of practice to read and spell these words “in a Flash”. These are called “Flash Words” instead of “sight words” because students do not have to memorize any part of Flash Words. They can use their knowledge of phonics patterns to read and spell the words.

Flash Words with advanced vowels to teach with early phonics instruction

Table 2B shows 60 one-syllable words with more advanced vowel spelling patterns. A few of these are so frequent that they will need to be taught when students are still learning the short vowel spelling patterns (VC and CVC) during phonics lessons.

Table 2B: Flash Words (Decodable Words)

60 One-Syllable Words With R‐Controlled, Long, and Other Vowel Spellings

(Numbers in parentheses are the Dolch Frequency Ranking)

| r-Controlled Vowels | CV Long Vowel | VCe (silent e) | Vowel Teams with Long Vowel Sounds | Vowel Teams with Other Vowel Sounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Sorted by vowel spelling) | (Sorted by vowel spelling) | (Sorted by vowel spelling) | (Sorted by vowel sound, then vowel spelling) | (Sorted by vowel sound, then vowel spelling) |

| for* (16) | I* (6) | came (69) | play (127) | out* (31) |

| or* (123) | he* (4) | take (94) | may (130) | round (140) |

| start (150) | she* (15) | make (114) | say* (183) | found (200) |

| far (205) | be* (33) | made (162) | see* (48) | down* (40) |

| her* (28) | we* (36) | gave (164) | green (99) | now* (66) |

| first (146) | me* (58) | ate (177) | sleep (116) | how* (88) |

| hurt (186) | go* (35) | like (53) | keep (143) | brown (117) |

| so* (47) | ride (76) | three (170) | look (26) | |

| no* (68) | five (119) | eat (125) | good (82) | |

| my* (56) | white (152) | read (197) | new (148) | |

| by* (103) | clean (208) | soon (161) | ||

| fly (138) | right (90) | draw (207) | ||

| try* (147) | light (184) | saw* (106) | ||

| why (198) | own (199) | |||

| show (202) | ||||

| grow (209) |

* Many programs teach these words as Heart Words when students are still learning to read words with short vowels.

Traditionally, many words in Table 2B would be taught as “sight words” and not included as part of phonics lessons. These words might be introduced as they are encountered in a story, or they might be taught in order. For example, he would be taught as high-frequency word #4, then she taught as high-frequency word #12, with we (#26), be (#33), and me (#58), following later.

Under the new model, words with asterisks in Table 2B are still introduced when short vowels are being taught. The difference in the new model is that these words are grouped together by vowel spelling pattern to make it easier for students to remember the words. Instead of teaching he in isolation as a word to be memorized, we teach he, be, we, me, and she together (as shown in the CV column in Table 2b) and point out that the letter e spells the long e sound. Go, no, and so can be taught together, as can my, by, and why.

Students will learn words more easily when grouped together by similar spelling than by memorizing words one at a time as whole units. If the curriculum requires a Flash Word to be taught before the vowel pattern has been introduced, teachers can refer to Table 2B to find words that can be grouped together.

Flash Words with two and three syllables

Table 2C shows 16 Flash Words with two syllables and one Flash Word with three syllables. We recommend teaching these words after students have learned to read two‐syllable words in phonics instruction. If these words must be introduced earlier, students will learn them more easily if the teacher breaks the words into syllables and shows any known letter sounds in each syllable. This way students learn to read each syllable and blend the syllables into a word, instead of having to memorize the whole word.

Table 2C: Flash Words (Decodable Words)

17 Two-Syllable Words and 1 Three-Syllable Word

(Numbers in parentheses are the Dolch Frequency Ranking)

| CVC | "A" Spells Schwa in First Syllable | Short Vowels and r-Controlled Vowels | Short Vowel and Long Vowel | All Other Two-Syllable Words | Three-Syllable Word |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| seven* (134) | about* (84) | after (108) | myself (139) | little (39) | every** (96) |

| upon (211) | around* (85) | never (133) | open* (165) | over (73) | |

| away* (101) | better (172) | funny (175) | going (115) | ||

| under (196) | yellow 118) | ||||

| before (124) |

* These words have a schwa sound in the first or second syllable.

** This word is often pronounced with two syllables, especially in conversation.

Heart Words

The Dolch 220 List has 82 Heart Words (37%) that are shown on Tables 3A and 3B. Heart Words have Heart Letters, which are the irregularly spelled part of the word. For example, o is the Heart Letter in the words to and do.

Some of the Dolch Heart Words with similar spelling patterns can be grouped together, even though the spelling patterns are not regular. Table 3A (on the next page) shows 45 Heart Words grouped according to similar spelling patterns. The table also lists twelve words not on the Dolch List. These twelve words have similar spelling patterns to the Dolch words listed, and the words are likely to be words already in young students’ vocabularies. For example, could and would are Dolch words. We recommend adding should when could and would are taught, even though it is not on the Dolch 220 List.

The groups of words in Table 3A can be added to any phonics or spelling lesson, with the Heart Letters pointed out. For example, the words his, is, as, and has can all be taught as vc and cvc words in which the letter s is the Heart Letter because it spells the sound /z/.

For example, the words his, is, as, and has can all be taught as vc and cvc words in which the letter s is the Heart Letter because it spells the sound /z/.

Table 3A: Heart Words

59 Words Grouped by Similar Spelling Patterns

45 Words from the Dolch List and 14 Not on the Dolch List

(Numbers in Parentheses Are the Dolch Frequency Ranking)

(Diamond [♦] indicates word is not on the Dolch List, but it fits the spelling pattern)

| Unusual Spelling Pattern | High-Frequency Words |

|---|---|

| s at the end of the word spells /z/ | his (13), is (27), as (32), has (166) |

| v is followed by e because no English word ends in v | have (34), give (144), live (206) |

| o-e spells short u /ŭ/ | some (30), come (64), done (180) |

| o spells /ōō/ (as in boot) | to (2), do (41), into (77) |

| rhyming words spelled with the same last four letters | there (29), where (95) |

| s spells /z/ in a vce word | those (179), these (212) |

| all spells /ŏll/ | all (25), call (167), fall (193), small (195), ball ♦ |

| oul spells /ŏŏ/ (as in cook) | could (43), would (57), should ♦ |

| e at the end is after a phonetic r-controlled spelling | were (50), are (63) |

| vcc and cvcc words with o spelling long o /ō/ | old (102), cold (136), hold (173), both (190) |

| cvcc words with i spelling long i /ī/ | find (167), kind (189), mind ♦ |

| words similar in meaning and spelling | one (54), once (160) |

| a after w sometimes spells short o /ŏ/ | want (86), wash (201), watch ♦ |

| ue spells /ōō/ as in boot | blue (79), glue ♦, clue ♦, true ♦ |

| u spells /ŏŏ/ (as in cook) | put (91), full (178), pull (187), push ♦ |

| rhyming words with silent l | walk (121), talk ♦ |

| rhyming words - the letter a spells short i or short e (depending on dialect) | any (83), many (218) |

| oo at the end of a word spells /ōō/ (as in boot) | too (92), boo ♦, moo ♦ |

| or spells /er/ | work (145), word ♦, world ♦ |

| uy spells long i /ī/ | buy (174), guy ♦ |

Teaching Heart Words

Table 3B shows 37 Heart Words not easily grouped by spelling patterns. Most of the words are more difficult for spelling than for reading.

Most of the words are more difficult for spelling than for reading.

As with all Heart Words, these words can also be incorporated into phonics instruction when students learn to read the regularly spelled letters a word. For example, when students know the digraph th, they and their can be introduced. The digraph th in both these Heart Words is a regular spelling for the sound /th/. The Heart Letters are ey in they and eir in their. Similarly, the Heart Letter in the word what is a, and the Heart Letter in the word from is o.

Table 3B: Heart Words

37 Words that Do Not Fit into Spelling Patterns

(Numbers in parentheses are the Dolch Frequency Ranking)

| the (1) | very (71) | here (105) | does (154) | use (181) |

| a (5) | yours (74) | two (122) | goes (156) | carry (194) |

| of (9) | from (81) | again (126) | write (157) | because (204) |

| you (7) | don’t (87) | who (128) | always (158) | together (214) |

| was (11) | know (89) | been (129) | only (168) | please (215) |

| said (12) | pretty (97) | eight (135) | our (171) | shall (219) |

| they (18) | four (100) | today (137) | warm (176) | laugh (220) |

| what (46) | their (104) |

Students enjoy drawing a heart above Heart Letters, and the hearts help them remember the irregular spellings.

For example, in the word said, the hearts would go above ai because those letters are an unexpected spelling for short e (/ĕ/). A student’s practice card for the word said is shown at the right.

Implementing the new model

In order to implement the new phonics-based model for teaching high-frequency words, teachers will need to fit high-frequency words into phonics instruction. To do this, generally a committee of three or four kindergarten and first grade teachers organizes their lists of high-frequency words according to Heart Words and Flash Words by spelling patterns. Next they determine when and how high-frequency words fit into the phonics scope and sequence. These same teachers provide professional development to show other teachers how to implement the new model.

Sometimes a coordinated effort to change the way high-frequency words are taught is not an option, and teachers are able to only partially implement the suggestions in this article. These teachers continue to introduce the words as determined by their curriculum. However, they tell students whether the “sight word” is a Flash Word or a Heart Word, and they introduce the words by teaching letter–sound relationships as outlined in this article. Further, teachers introduce words with similar spelling patterns whenever possible. For example, if only the word would is scheduled to be introduced, they also teach could and should, which fit the spelling pattern. Finally, these teachers do not hold students accountable for high-frequency words that are beyond the spelling patterns that have been taught in phonics lessons.

These teachers continue to introduce the words as determined by their curriculum. However, they tell students whether the “sight word” is a Flash Word or a Heart Word, and they introduce the words by teaching letter–sound relationships as outlined in this article. Further, teachers introduce words with similar spelling patterns whenever possible. For example, if only the word would is scheduled to be introduced, they also teach could and should, which fit the spelling pattern. Finally, these teachers do not hold students accountable for high-frequency words that are beyond the spelling patterns that have been taught in phonics lessons.

The new model allows a different approach for working with students who have difficulty learning high-frequency words. For example, students working on short vowel patterns may confuse her and here, which are often introduced early as part of the “sight word” list. A teacher who recognizes the source of this confusion would not expect students to continue trying to memorize the two words. Instead, the teacher would include her as part of instruction on r-controlled vowels and include here when silent e is taught. Students will be less likely to misread or misspell these words when they understand the relation of the spelling er to the sound /er/ and the spelling ere to the sound /ēr/.

Instead, the teacher would include her as part of instruction on r-controlled vowels and include here when silent e is taught. Students will be less likely to misread or misspell these words when they understand the relation of the spelling er to the sound /er/ and the spelling ere to the sound /ēr/.

Traditionally, students would have continued struggling with and failing to memorize these easily confused words. With the new model, those students are not held accountable for accurately reading and spelling the words until they can understand and use the sound–spelling correspondences. All teachers using this approach say that students learn to spell and read the words much more easily than with the traditional approach.

About the authors

Linda Farrell and Michael Hunter are founding partners of Readsters, LLC. They provide professional development and write curriculum to support excellent reading instruction to students of all ages. Their favorite work is in the classroom where they can model effective reading instruction and coach teachers. Their most unusual work so far has been helping develop early reading instruction for children in Africa who are learning to read in 12 different mother tongue languages that Linda and Michael don’t even speak.

Their favorite work is in the classroom where they can model effective reading instruction and coach teachers. Their most unusual work so far has been helping develop early reading instruction for children in Africa who are learning to read in 12 different mother tongue languages that Linda and Michael don’t even speak.

Tina Osenga was a founding partner at Readsters, and she is now retired.

The Teaching of Sight Words: Part 1

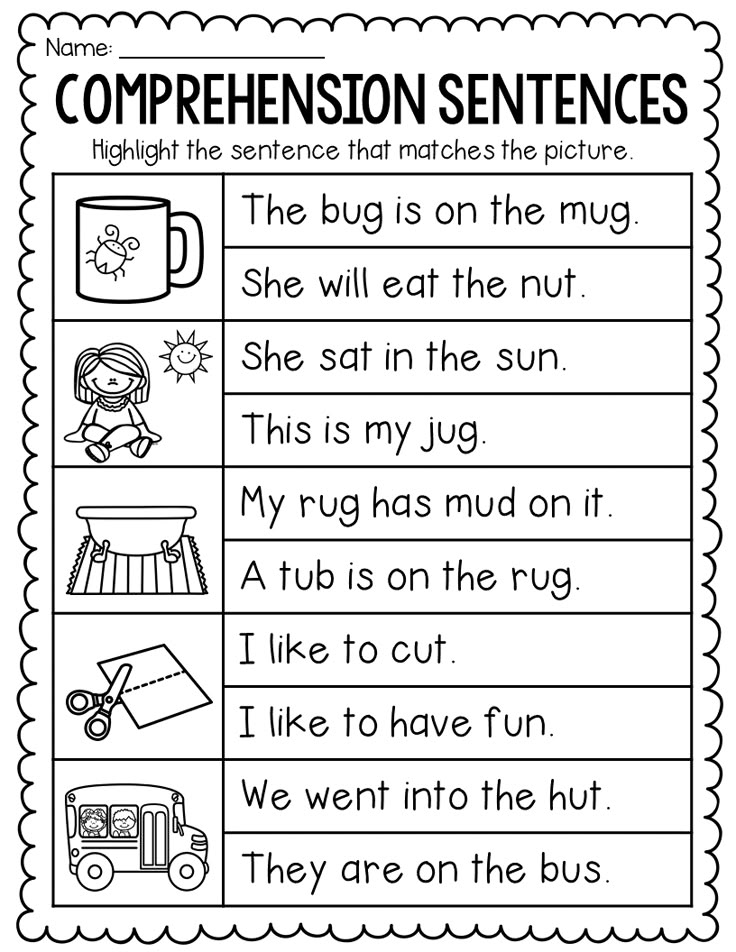

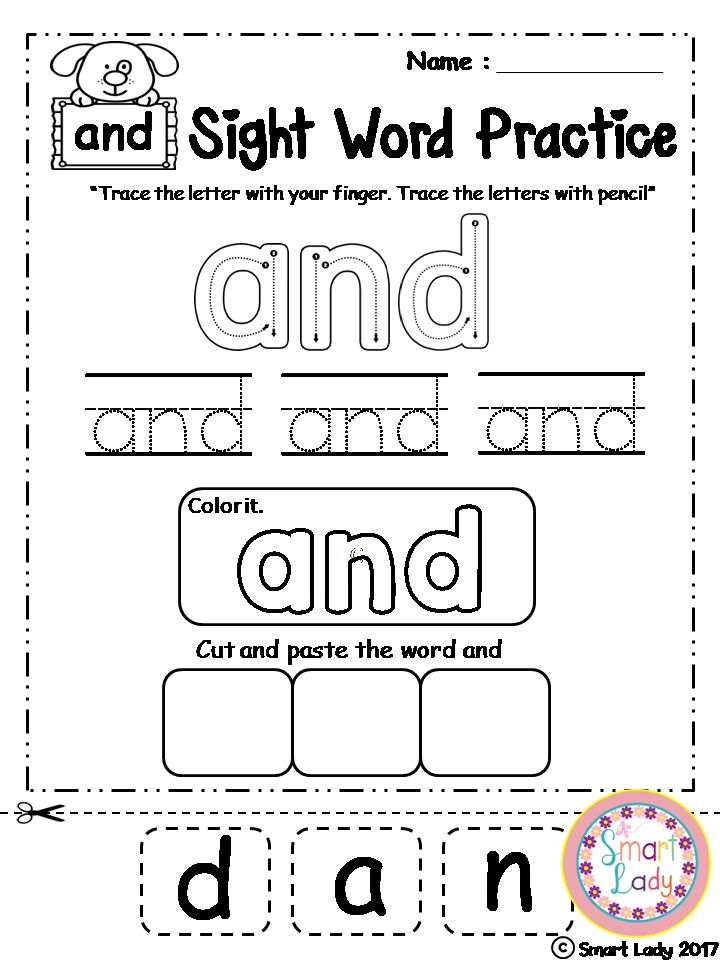

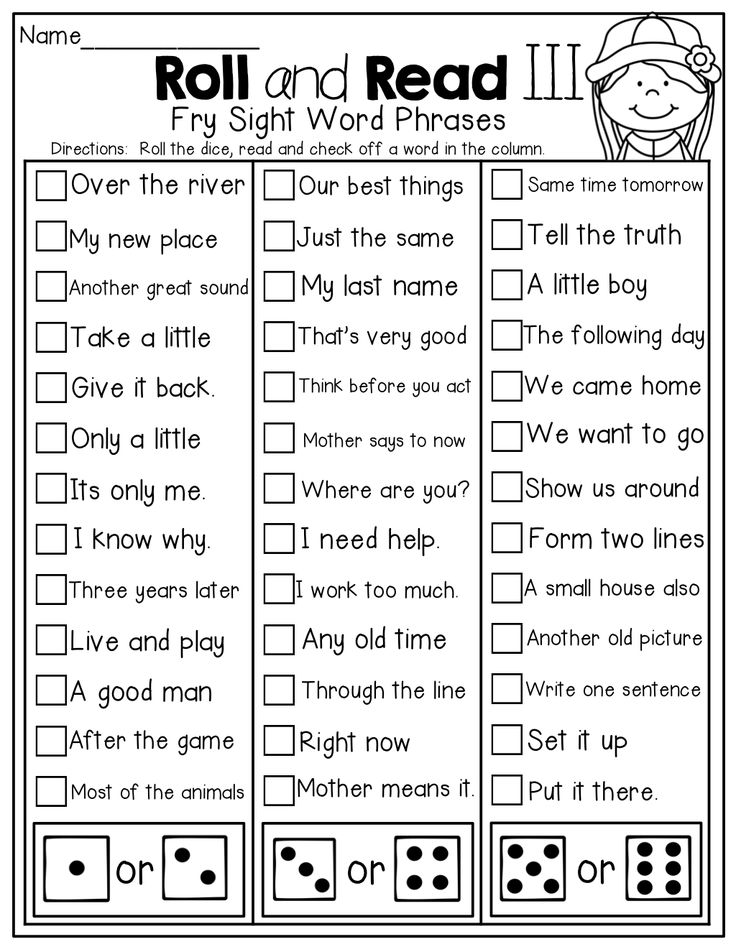

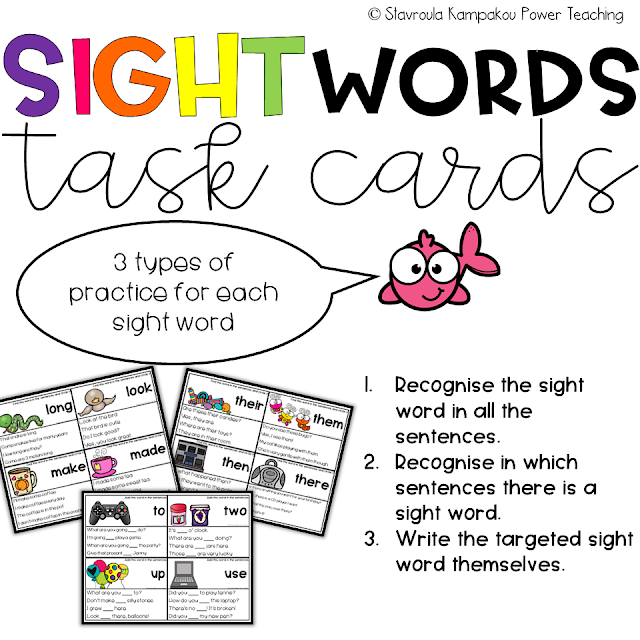

I get many questions regarding the teaching of sight words {often called high frequency words}: Are they really needed? If so, why? In what order should they be taught? How do you help them to “stick”? How do you hold kids accountable to spelling them correctly? I thought I’d take a couple of weeks to answer these questions by showing you how I have taught sight words as a classroom teacher, reading tutor, and now as a homeschooling mama.

What is a Sight Word?

Simply put, sight words are the commonly used words in our language {the, of, have, two, etc. }. Some of the common sight words cannot be sounded and out and therefore need to be learned by sight as whole word {such as was, the, or of}.

}. Some of the common sight words cannot be sounded and out and therefore need to be learned by sight as whole word {such as was, the, or of}.

While it is a great practice to help kids see that many sight words relate to phonics, sounding out the more phonetic sight words {and, red, to, etc.} should not be a child’s first line of defense. Because these words are so common, knowing them by sight {within one second of seeing the word} is preferred to increase fluency and support comprehension.

Sight words are only part of a balanced reading program. I am a firm believer that kids need both phonics {I love word study} AND sight words.

These two, of course, don’t stand alone. Word and phonics knowledge have to be applied to real reading and writing to be of any use. With that being said, sight words ARE vitally important because they make up so much of what we read {more about that in a minute}.

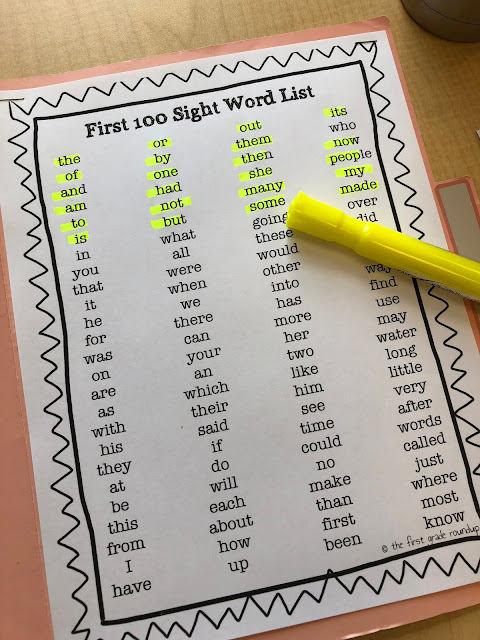

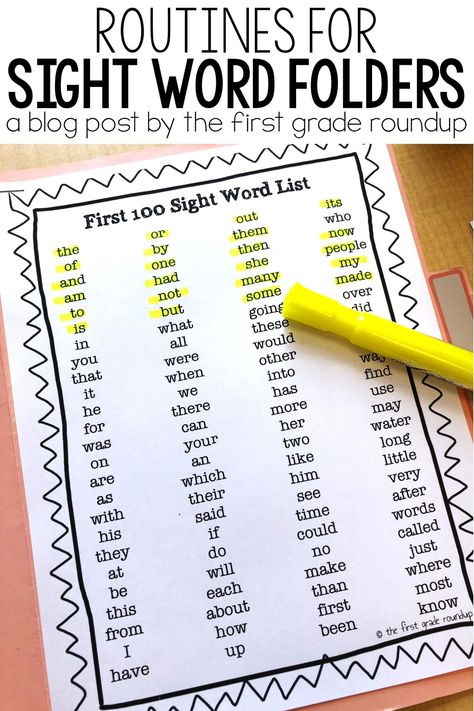

Sight Word Lists

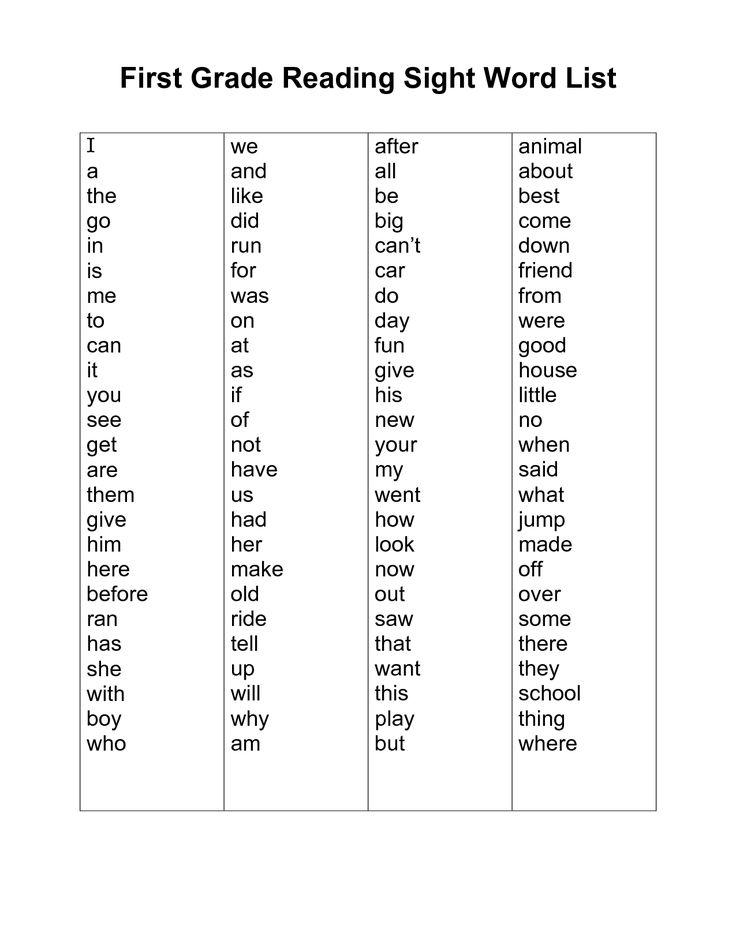

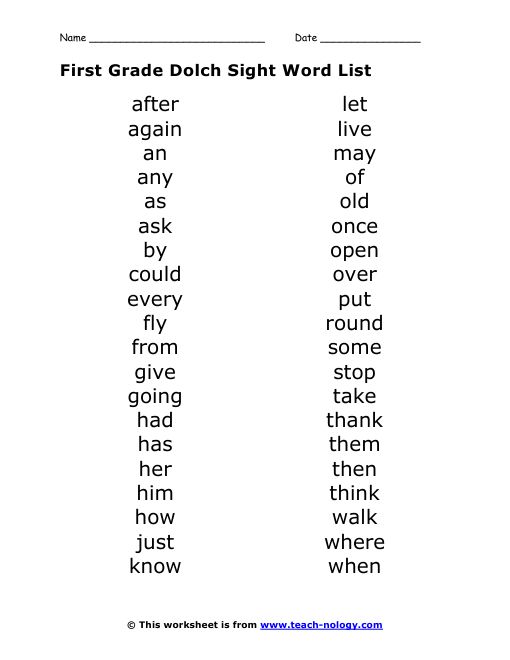

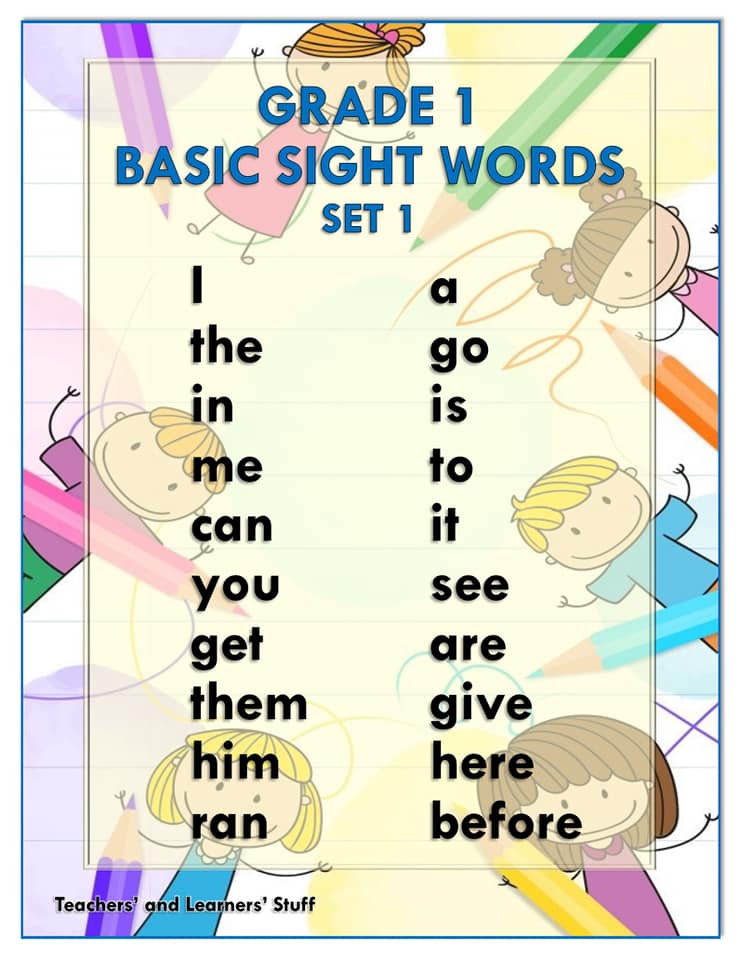

The two most commonly used sight word/high frequency word lists are:

1. Dolch Words– 220 commonly used words, listed in order by grade level {PP through 3rd grade}. I lean towards the camp of reading teachers who feel the entire list should be familiar by the end of 1st grade.

Dolch Words– 220 commonly used words, listed in order by grade level {PP through 3rd grade}. I lean towards the camp of reading teachers who feel the entire list should be familiar by the end of 1st grade.

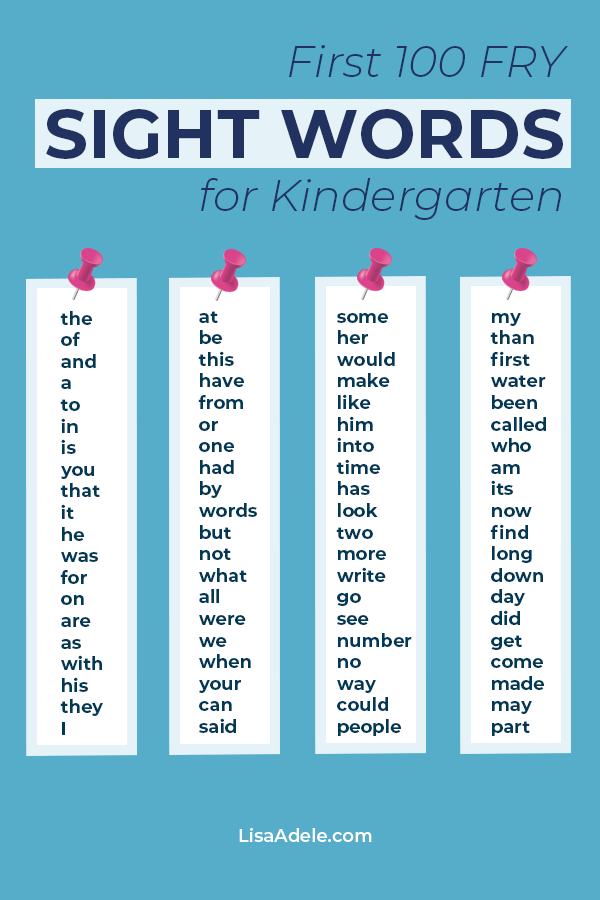

2. Fry’s List– I honestly prefer Fry’s list, probably because that’s the list I used in my teacher training as well as in the classroom. It’s a little more in-depth than the Dolch word list, with 100 words on each list {10 words on each list}. Fry’s first 100 words alone make up over 50% of what we read! Yes, 50%. That’s A LOT of words! It’s no wonder that they are important!

How Many Sight Words Should I Introduce?

Introduction of sight words depends mainly on the developmental stage of your child. Age can also play a factor, but don’t let that be your deciding factor.

The developmental stage of your child should be your main indicator. For example, NJoy started showing me he was ready for sight words at the age of three. He was highly interested and knew all of his letters and sounds. Your child may be in the 1st grade, but in the same developmental stage as my son was at three. Pay attention to this. For more information about teaching sight words in a developmental way, please visit my post: When Sight Words Just Don’t “Stick”.

Your child may be in the 1st grade, but in the same developmental stage as my son was at three. Pay attention to this. For more information about teaching sight words in a developmental way, please visit my post: When Sight Words Just Don’t “Stick”.

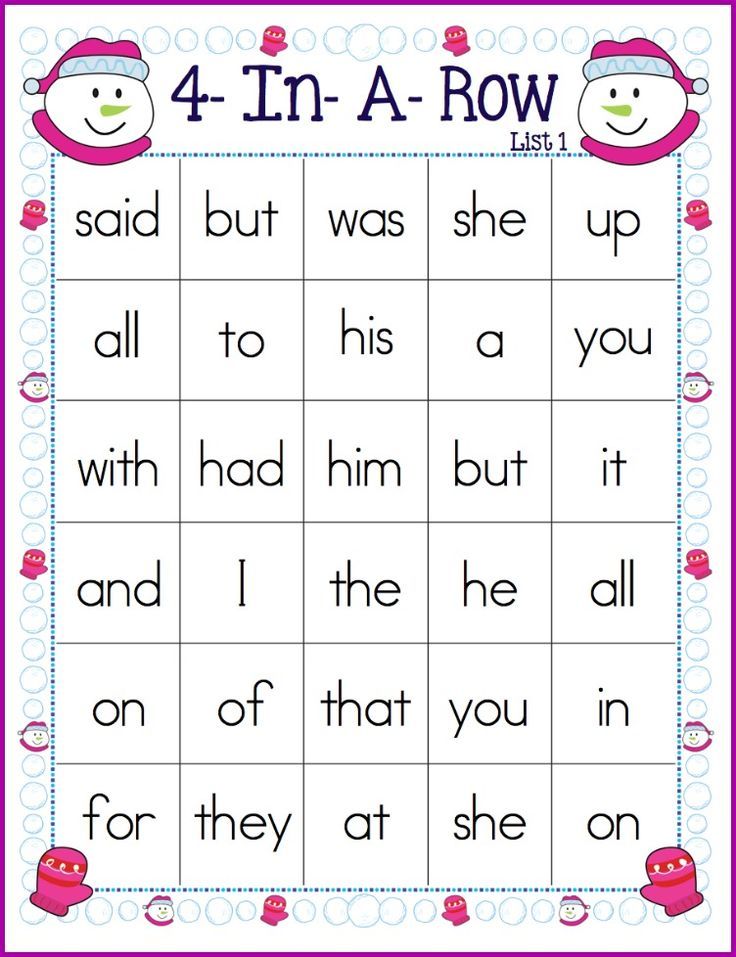

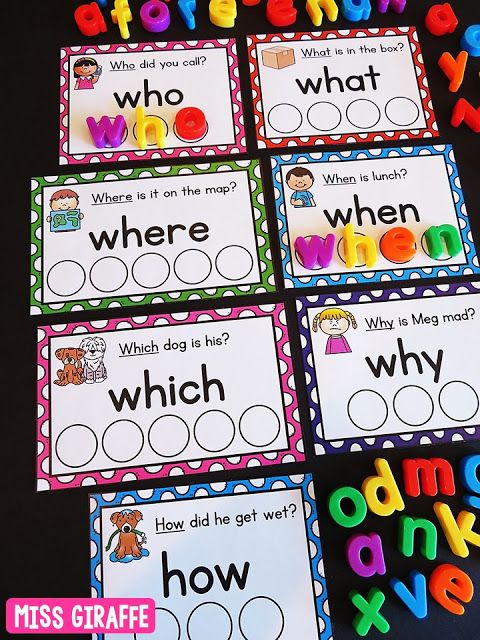

With a young reader, it is good to only introduce one to two sight words at a time. If you introduce more than one at a time, the words need to be visually different {the, of= yes! / is, in = no!}. When kids are first learning sight words, they can get them easily confused and having two or more words that are visually the same makes it all the more confusing to remember them.

As kids grow in their reading, 5-10 sight words might be more appropriate. The general rule I follow is: if the words aren’t “sticking”, I’m going to fast for my child.

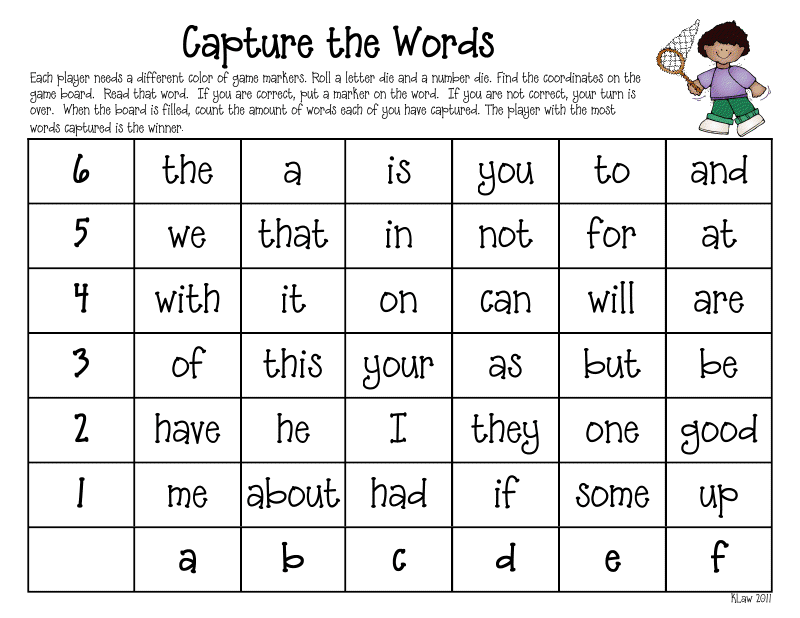

Connecting Sight Words to Real Reading and WritingI don’t always pick the sight words in order {referring to the order of the Dolch or Fry’s list}. While I typically don’t pick the 99th word first, I start with a text. I have quite a collection of beginning readers. I’ve collected books over the years at used book stores, yard sales, and from retiring teachers.

While I typically don’t pick the 99th word first, I start with a text. I have quite a collection of beginning readers. I’ve collected books over the years at used book stores, yard sales, and from retiring teachers.

When my kids are just starting out, I began with predictable texts {much like the emergent readers I’ve created for Reading the Alphabet}. Predictable text repeats the same phrase over and over in the book; usually with a little variation on the last page. For example, I might notice that the text says, “I like to _____…I like to_____…” on each page. Naturally, I would pick like and to as the sight words for that week or time period.

As a classroom teacher, reading tutor, and now homeschooling mom, this is my thought process when I’m looking through a book and choosing sight words to study:

- Is this text on the child’s level? Are there too many words he doesn’t know? Are there a few words he doesn’t know? This is also important, as new words and new decoding strategies help kids grow as readers.

I don’t want to pick a book in which he knows every single word. It would be too easy. {I have all my books leveled and organized in boxes by their level, something I did when I first starting tutoring.}

I don’t want to pick a book in which he knows every single word. It would be too easy. {I have all my books leveled and organized in boxes by their level, something I did when I first starting tutoring.} - What sight words on the list {Dolch/Fry’s list} have not been introduced, yet?

- Are there any reocurring sight words that I could pull from the story/stories for the week {that match words on the list}? If there are too many sight words I’d need to teach him before he could read the text, I know the text will probably be too hard for him.

These two books made a great pair as they introduced some of the same words.

I REALLY like to pull the words from the texts and use those for the week because it connects learning words to reading. The purpose of learning these sight words anyway is to comprehend text. If I decide on the sight words, then have him read texts all week that either don’t have the sight words in them or they are few and far between, his literacy instruction is choppy and disconnected.

As he’s learning new words, I also like to point them out when I read text aloud or when they appear in authentic situations, like in a cookbook or road sign. Of course, these sight words naturally come up when writing and spelling, too {more about that next week in Part 2}.

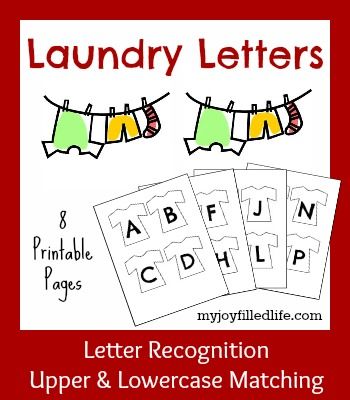

Where do I put the Sight Words?

I have a special board in our schoolroom that “hosts” the new words for the week. They stay on the board all week. We play sight word games with the words and refer to them frequently when reading and writing. {This were his words on the board the week I introduced the two books mentioned in the picture above.}

With NJoy, I post his new word on the wall at his desk.

Next week {Part 2}, I plan on talking more about what do to with the sight words you’ve introduced once the week is over. I hope you will find it helpful!

~Becky

Want MORE Free Teaching Resources?

Join thousands of other subscribers to get hands-on activities and printables delivered right to your inbox!

How to remember everything - instantly and forever

- David Robson

- BBC Future

Image courtesy of Thinkstock

is here to learn how to remember facts instantly and forever. BBC Future met with a group of scientists and memory champions.

BBC Future met with a group of scientists and memory champions.

The world's leading memory experts make me feel embarrassed about my modest abilities. Ben Whatley, for example, told me about a famous mnemonist named Matteo Ricchi.

Lived in the 16th century. a Jesuit priest became the first European to pass an examination for high-level officials in China.

This exam was a very painful test and included, among other things, the memorization of a huge array of texts of classical poetry. This task could take a lifetime.

"Only 1% of the subjects passed these exams, and yet Ricky managed to pass them after 10 years, although he did not know a word of Chinese before."

(Similar articles from the "Journal" section)

Can psychology endow us with the ability to master our own memory in such a brilliant way? That is what Watley is aiming for.

Together with former memorization champion Ed Cook, he has already developed the Memrise educational application, which uses some of the principles of mnemonics.

Now they have joined forces with researchers at University College London to find ways and means to improve their techniques.

They approached memory experts and asked them to conduct a series of experiments in order to discover the easiest and most effective method for memorizing new information.

Which way to choose

First round. The task given to the contestants is, at first glance, simple, says Rosalind Potts of University College London: "If you only have one hour to memorize 80 words, what will you do to remember them in a week?" The task is complicated by the fact that the scientists chose 80 words from the Lithuanian language.

The participants of the experiment were divided into two groups. In one group, they used special techniques for memorizing words (they were prompted by scientists), in the other group, participants did not resort to any tricks.

Some techniques failed to improve the memorization and subsequent reproduction of information. "It shows how difficult it is to translate scientific principles into real learning," says David Shanks, also from the university.

"It shows how difficult it is to translate scientific principles into real learning," says David Shanks, also from the university.

image copyrightThinkstock

image caption,To better remember information, admit to yourself that you don't know everything

colleagues were paid for participating in the experience with cakes."It happens," says Jana Weinstein of the University of Massachusetts Lowell, who was on the panel of judges.

However, many teams managed to learn something from the experiment. Some participants were able to memorize twice as many words - instead of being locked into one single technique, they tended to use a combination of several techniques.

Admitting your own ignorance

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

End of Story Podcast

Self-examination is one of the surest ways to improve your memory.

What I found surprising and potentially useful was a trick called "false reproduction".

The participants in the experiment were made to guess the meaning of certain Lithuanian words without prior preparation.

"They always got it wrong the first time," says Shanks. However, as psychological studies have shown, initial mistakes lead to the fact that later words - in the correct meaning - are well remembered.

"This method gives much more tangible results than just memorizing words."

Simply admitting one's own ignorance has been found to stimulate memory and allow for twice as much information to be absorbed compared to groups that do not use this method.

In psychology, it is known that if you complicate a task a little, it can increase concentration and lay a stronger foundation for subsequent memorization and recall of information.

Sliding on the waves of memory

Excessive study leads to a waste of time. Some participants developed algorithms to determine the level of effort needed to memorize and recall each of the 80 words.

You can go the other way and rely on your own intuition when scheduling the training, setting longer and longer pauses between sessions of self-examination and work on the mistakes.

Image copyright Thinkstock

Image captionThe more you interact with the information, the more likely you are to remember everything

was to promote memory).

Of course, when you are studying, you need to take short breaks so that fatigue does not reduce your natural abilities.

Buffet

You may be tempted to sort the material into blocks by topic and memorize these blocks one by one. So, some mentors did, organizing the words into categories and topics.

However, one team concluded that repeating all 80 words in a circle could also be an effective method. As Ben Whatley points out, memorization tournament champions memorize the sequence of cards in a deck in a similar way. They skim through the entire deck quickly, instead of dividing it into blocks and memorizing them one by one.

If this method confuses someone, experiments show at least one thing: training sessions need to be diversified. It is better to spend time studying a variety of subjects and mastering different skills than concentrating on one single subject. Imagine that you are trying different dishes from the buffet, and not ordering lunch by choosing something from the menu.

Entertaining stories

Any form of "theme development" is a way to activate connections between neurons and imprint information in memory. One of the mentors asked the participants to write a short story using the words they were supposed to learn. Cook and Whatley were pleasantly surprised when they discovered that one team had adopted the "memory palace" method. This is a way of remembering by linking words to objects in a place you know well, for example, in your own apartment.

Cook and Whatley were pleasantly surprised when they discovered that one team had adopted the "memory palace" method. This is a way of remembering by linking words to objects in a place you know well, for example, in your own apartment.

The program developed by them will show you a picture of the room and suggest you the Lithuanian word lova - bed. You can imagine your sweetheart on the couch. Once you organize the memorization process, you can reverse all your steps and easily remember the right word.

Image copyright, Thinkstock

Image caption,A string on the finger and a cross drawn on the inside of the wrist will help you remember small but important things. It also underlies Cook's ability to memorize 2265 two-digit numbers in less than half an hour. Cooke and Watley's computer program simplifies the process, making it nearly automatic. "If our method wins, it will be a big breakthrough," says Cook.

And yet it is difficult to get rid of the idea that these methods are very far from what we need in everyday life. In the previous task, I tried to learn about 1000 Danish words using mnemonics. And although these techniques helped me remember the words individually, I was never able to start using these words on a flight, in a bar or restaurant.

In the previous task, I tried to learn about 1000 Danish words using mnemonics. And although these techniques helped me remember the words individually, I was never able to start using these words on a flight, in a bar or restaurant.

Cook agrees that this is just the first step. Such techniques, he says, can only form the basis of memory training. The same method makes it easier to learn not only languages, but also any other disciplines - history, mathematics. "Repeated checks, increasing the interval between tests - these techniques work in almost every case," he says.

Educational games

The judges hope to be able to hold competitions every year as they improve the art of memory.

In the future, there may be new inventive approaches that deserve attention. Shanks, for example, mentions one project that didn't get approved this year but may prove promising in the future.

"They've developed a video game where you have to shoot down spaceships in the sky. By chance, these ships have Lithuanian and English words written on them," he says. "I think it's a brilliant idea."

By chance, these ships have Lithuanian and English words written on them," he says. "I think it's a brilliant idea."

The real challenge for memory experts, however, is not just to make learning fast and efficient.

As every student knows, the biggest barrier to learning is distraction, whether it's the thought of going to the park to sunbathe or turning on the TV. Many new competitions may be required before this hurdle can be overcome.

Read the original of this article in English is available on site BBC Future .

Love at first sight

© Photo by Ilya Usatov

– Once upon a time there was a sixteen-year-old girl who fell in love with a blue-eyed guy – this is how Alla Shabalina begins the story of her life.

– Once she was walking down the street hand in hand with her grandmother, he came out to meet her. Their eyes met, their hearts beat faster. Here, in front of his grandmother, the guy confessed his love. He promised to marry. But he did not have time to finish the sentence. An old woman's bag flew past his face, almost brushing his cheek.

He promised to marry. But he did not have time to finish the sentence. An old woman's bag flew past his face, almost brushing his cheek.

The grandmother promised to beat the boy if he even once approaches his beloved granddaughter.

Aleksey was handsome and not stupid, but he had a reputation for being a bully, which is why he caused such a reaction.

But in addition to all other advantages and disadvantages, the guy was a man of his word. That same evening, he knocked on the window of his beloved. He did not know that the girl was under strict surveillance. And again everything that then fell under the arm of the granny flew into it: a dustpan, a broom, a piece of some kind of piece of iron. That evening the battle for Alla's heart was lost, but not the war.

Long exhausting conversations did not make the schoolgirl forget the blue-eyed guy. And in 1969, barely graduating from school, she moved to live with Alexei, her lover.

- There was no money for a magnificent wedding. So we just started living together. Only a few years later we managed to register a marriage, she recalls.

So we just started living together. Only a few years later we managed to register a marriage, she recalls.

Alla Shabalina considers this time to be a turning point in her life. She had another boyfriend, good grades at school, recommendations to go to college. But she chose love and marriage.

Left without education, she followed in her mother's footsteps and became a milkmaid at the local Voskhod collective farm. She experienced two personal tragedies - first the first child died, then the second.

Only in 1980, daughter Julia was born. Alla then worked as a teacher in a local kindergarten. She liked the classes, she always found a common language with the children.

Somehow, after another regional check, she was recommended to get an education. Assessing her approach to children, they predicted success in teaching. The only thing left was to get a diploma. Party organizer Yuri Lysenko even prepared for Alla a referral to the institute, knocked out housing in the regional center.

However, the young teacher refused to study. Alexei could not let his wife go to Stavropol even for a while. Again, the woman chose a family.

And soon she changed her job. She returned to the dairy farm of the collective farm. The Shabalins did not have their own cow then, and the child needed milk every day. She left the teaching profession forever.

- Once I had a fight with my husband. Yes, so much so that for a while she moved to live with her mother, - says Alla Shabalina. - Every day I passed by my house and only looked at my husband. He sat on the bench, but said nothing. Me too. After a week of silence, unable to stand it, she asked why he did not call me home. The husband replied: “But I didn’t kick you out.” Since then, I have not left the house, no matter how bitter our quarrels were.

After the birth of Yulia, Alla was looking forward to the birth of another child, but, unfortunately, he also died.

– In the 80s, Alexei was offered a job in another district, she recalls. - Together we went, as they said then, for big money to the Krasny Manych sheep farm. The husband was a shepherd, more than once his photograph fell on the Board of Honor. I helped as much as I could, both in the shed and in the pasture.

- Together we went, as they said then, for big money to the Krasny Manych sheep farm. The husband was a shepherd, more than once his photograph fell on the Board of Honor. I helped as much as I could, both in the shed and in the pasture.

A year and a half later, the Shabalins returned to their native village with money, as it seemed to them then, “big”, and farming: cows, sheep, poultry.

Alla was pregnant for the fifth time. In 1990, a second daughter was born. They named him Alla in honor of his mother.

Life went on as usual. The couple again got a job at the Voskhod collective farm. They worked hard and raised two beautiful daughters. Were happy. It seemed that all the hardships that fate had prescribed for them were left behind. In 2007 Alexei suffered a stroke. For several years before his recovery, he could not only move, but even speak. Alla learned to understand her husband's eyes. All cases for some time fell on the shoulders of the woman. But no matter how difficult it was for her, she did not quit working on the collective farm.