Your kid can read

Your Child Can Read!

Toggle Nav

Search

Search

Menu

Account

Settings

Language

English (US)

- Add More

Currency

USD - US Dollar

- GBP - British Pound

- EUR - Euro

Your Child Can Read! is the follow-up series to Your Baby Can Learn! Children under age 5 years should use the Your Baby Can Learn! series before starting this program. Please click here to see Your Baby Can Learn! kits.

Sort By Position Product Name Price Set Descending Direction

View as Grid List

11 Items

Show

15 30 All

per page

Sort By Position Product Name Price Set Descending Direction

View as Grid List

11 Items

Show

15 30 All

per page

Filter

Shopping Options

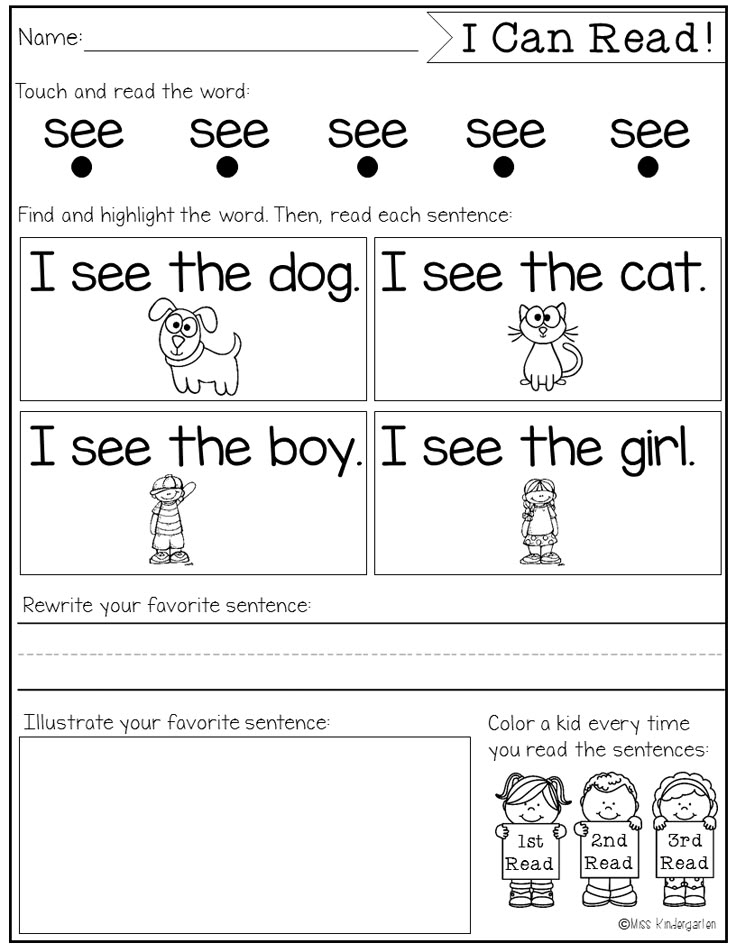

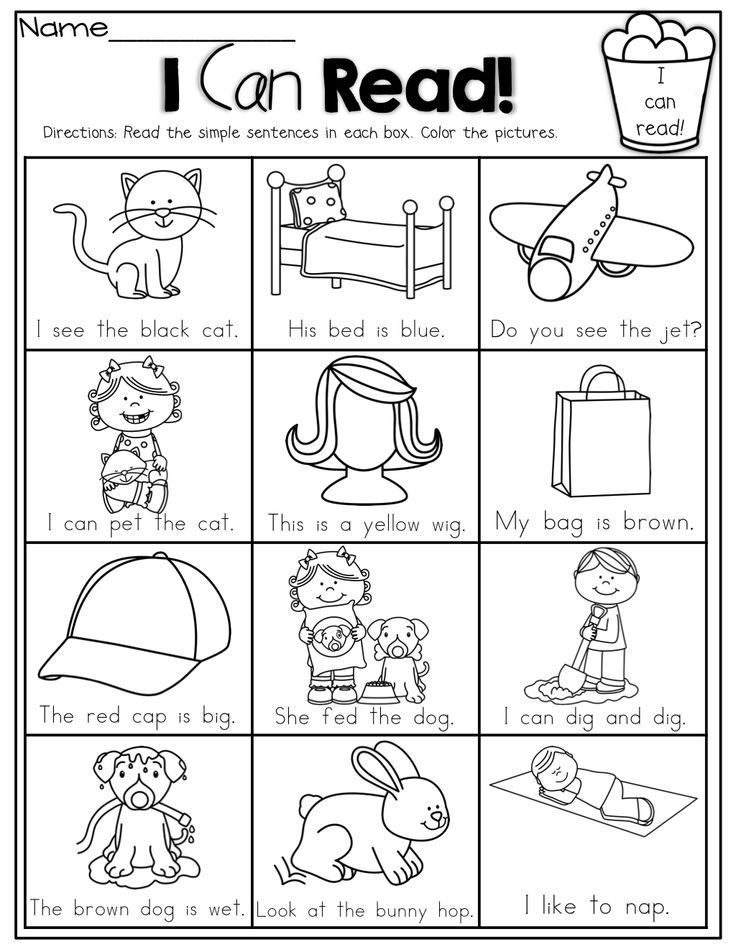

Teaching children to read isn’t easy.

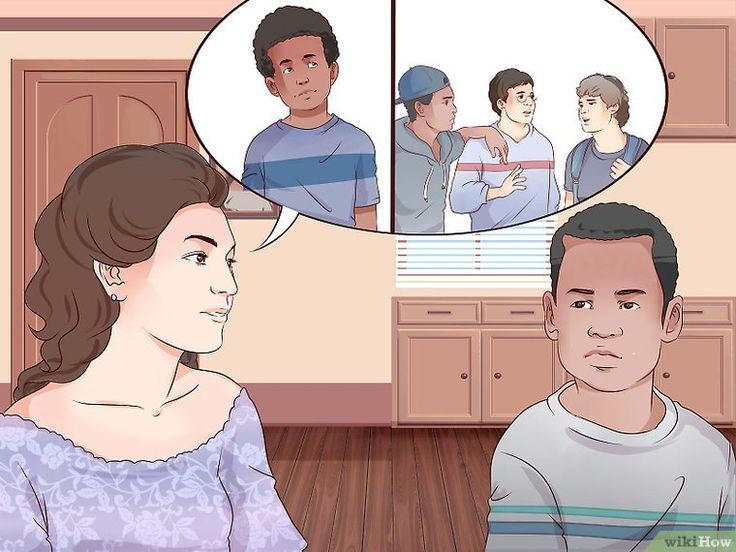

How do kids actually learn to read? A student in a Mississippi elementary school reads a book in class. Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger Report

How do kids actually learn to read? A student in a Mississippi elementary school reads a book in class. Research shows young children need explicit, systematic phonics instruction to learn how to read fluently. Credit: Terrell Clark for The Hechinger ReportTeaching kids to read isn’t easy; educators often feel strongly about what they think is the “right” way to teach this essential skill. Though teachers’ approaches may differ, the research is pretty clear on how best to help kids learn to read. Here’s what parents should look for in their children’s classroom.

How do kids actually learn how to read?

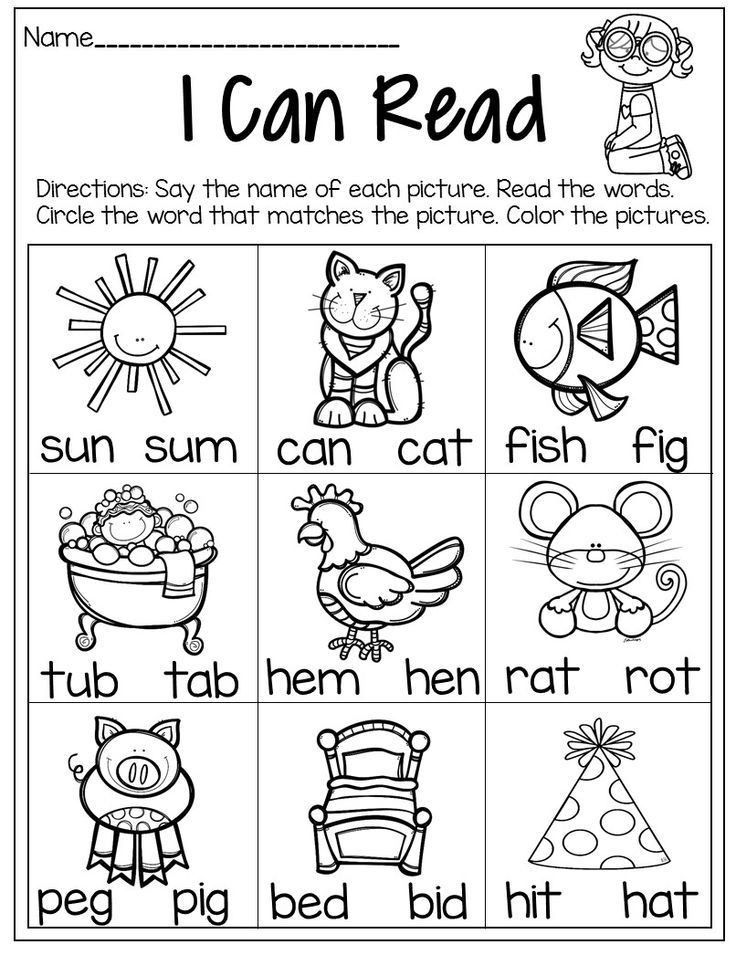

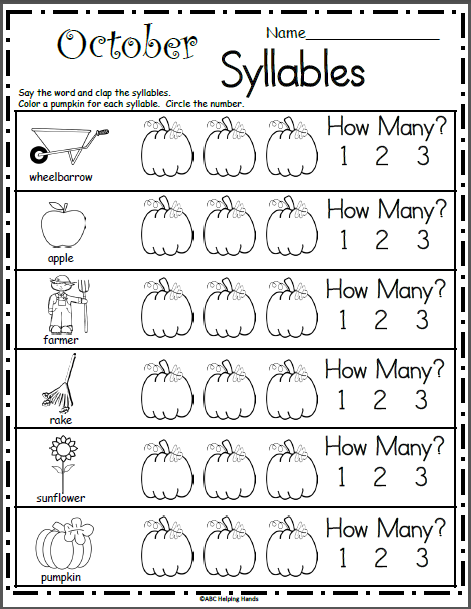

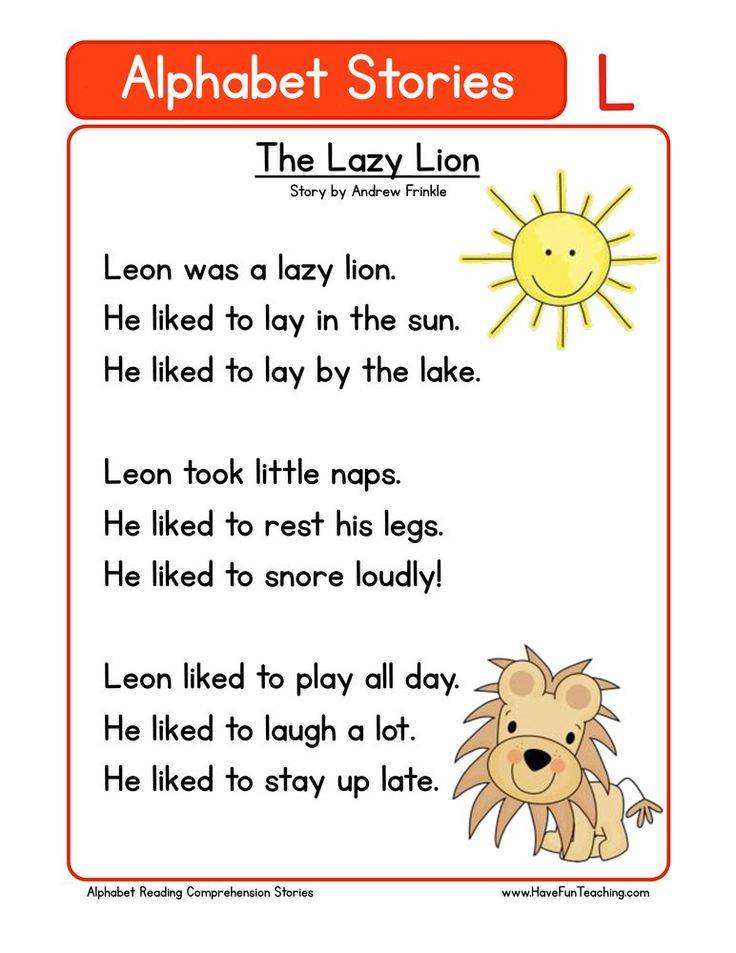

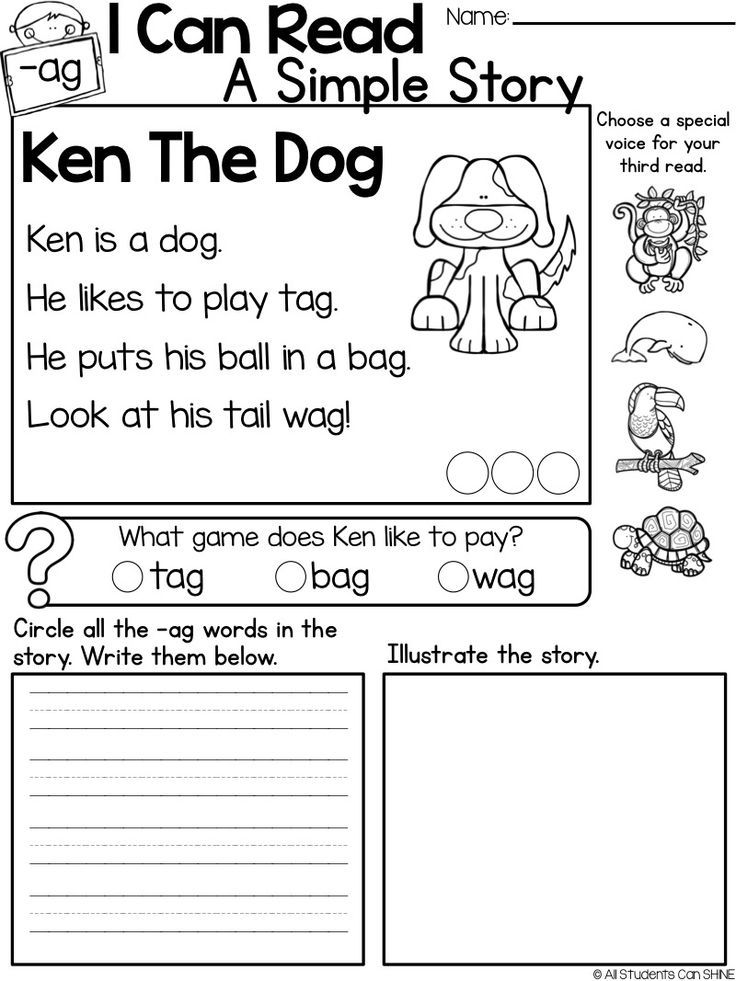

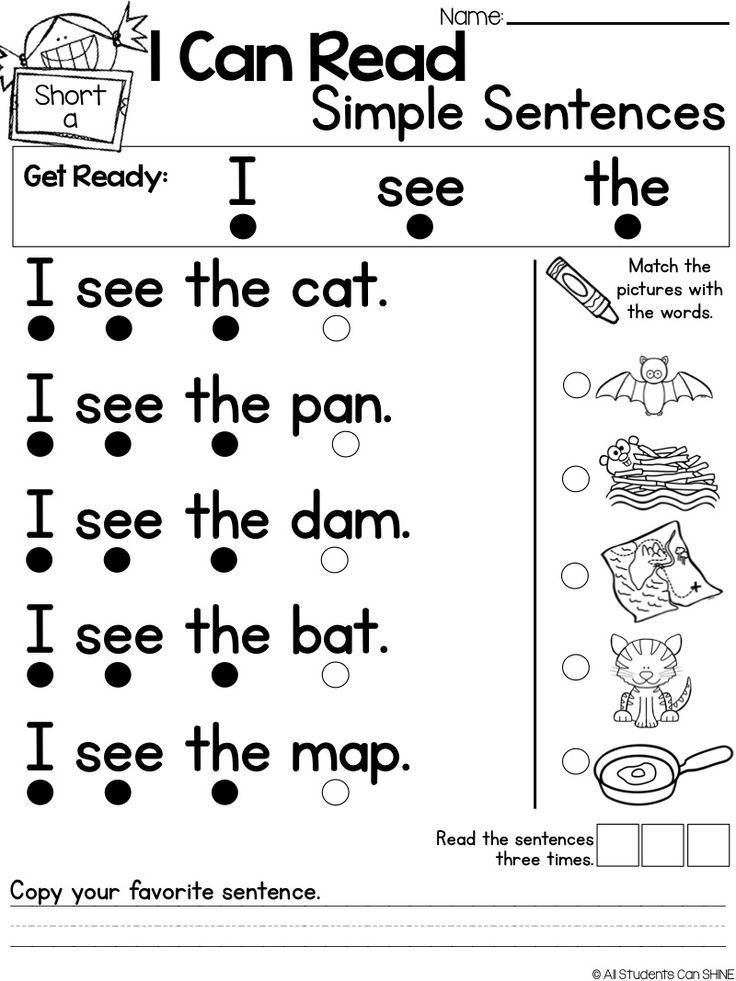

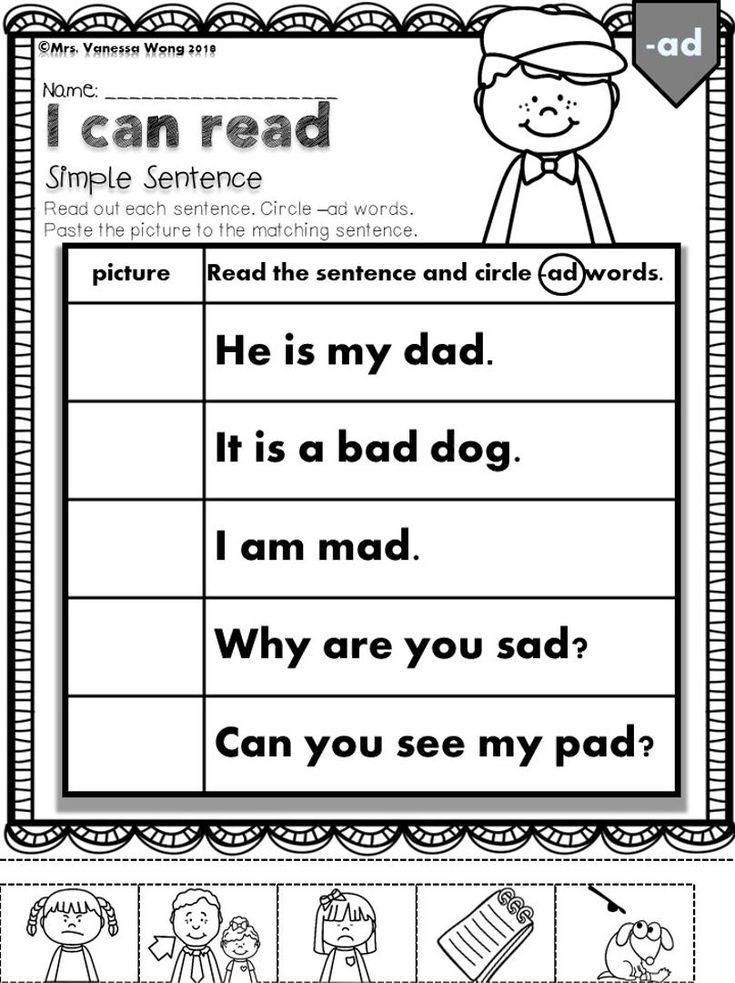

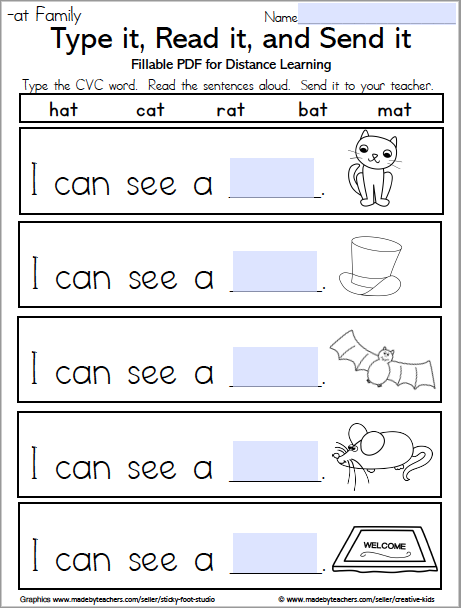

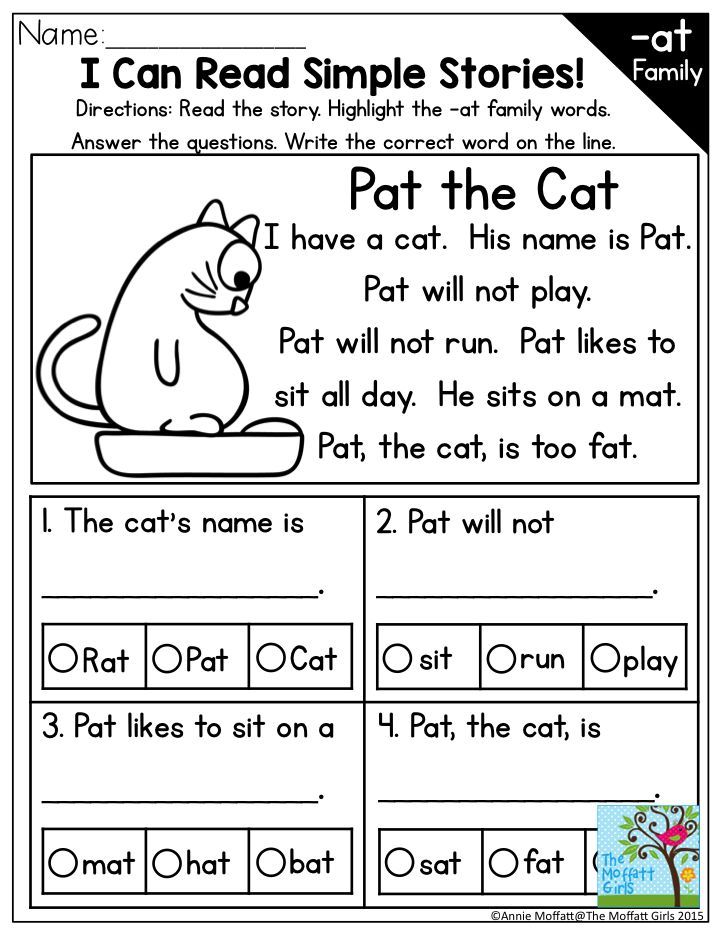

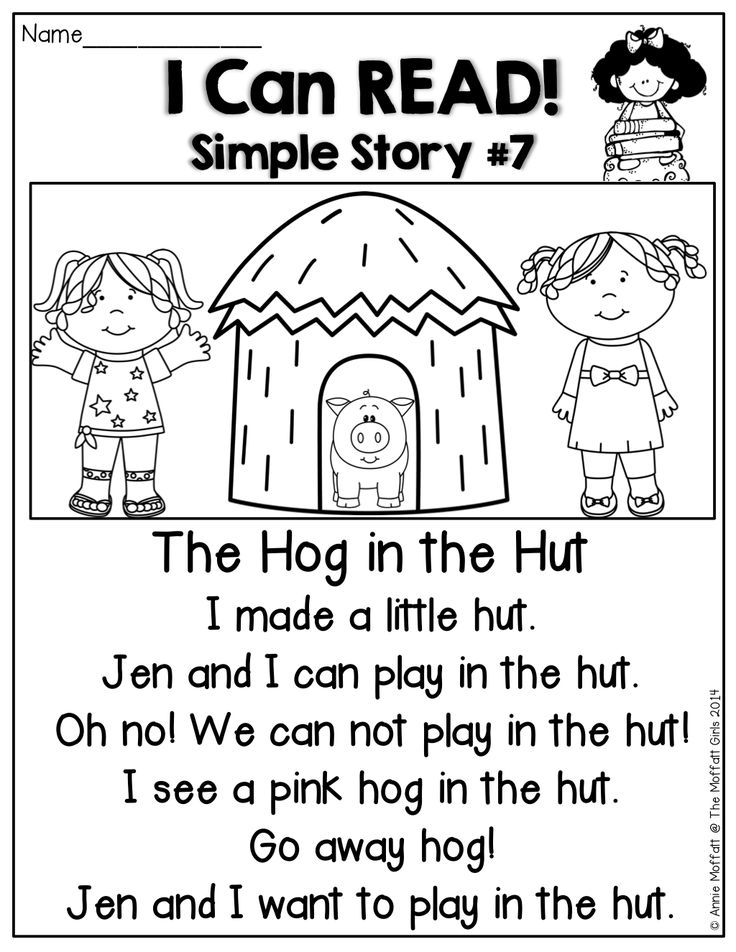

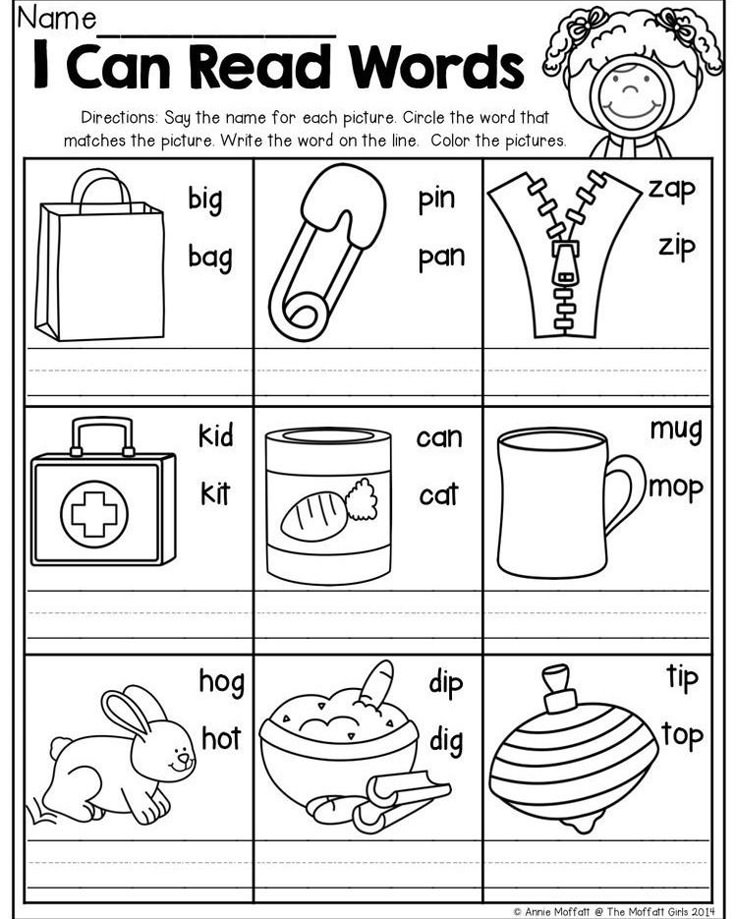

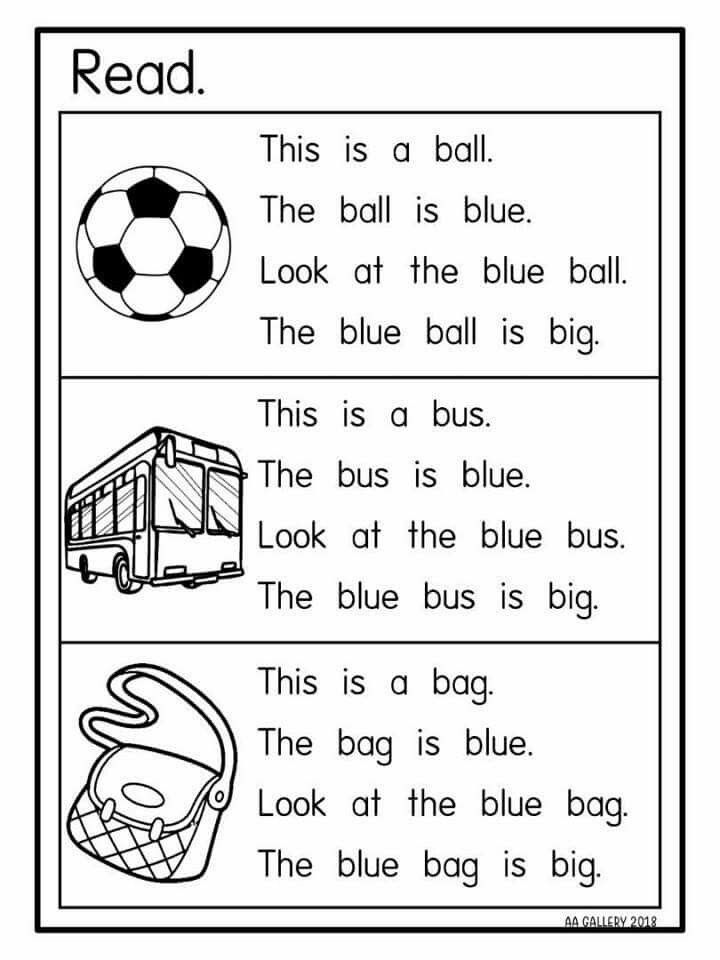

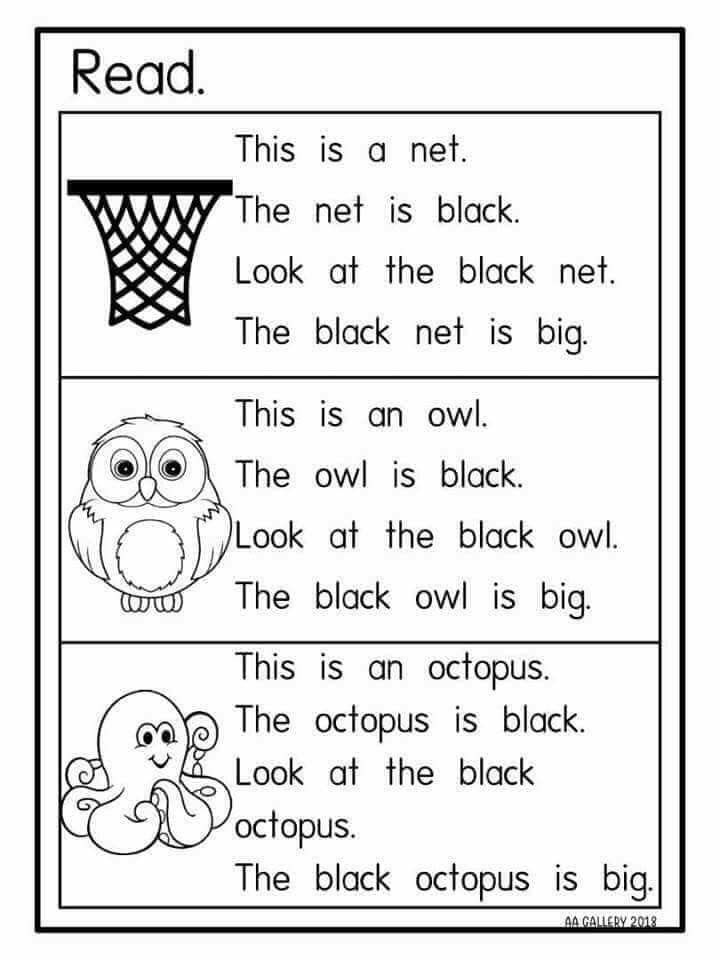

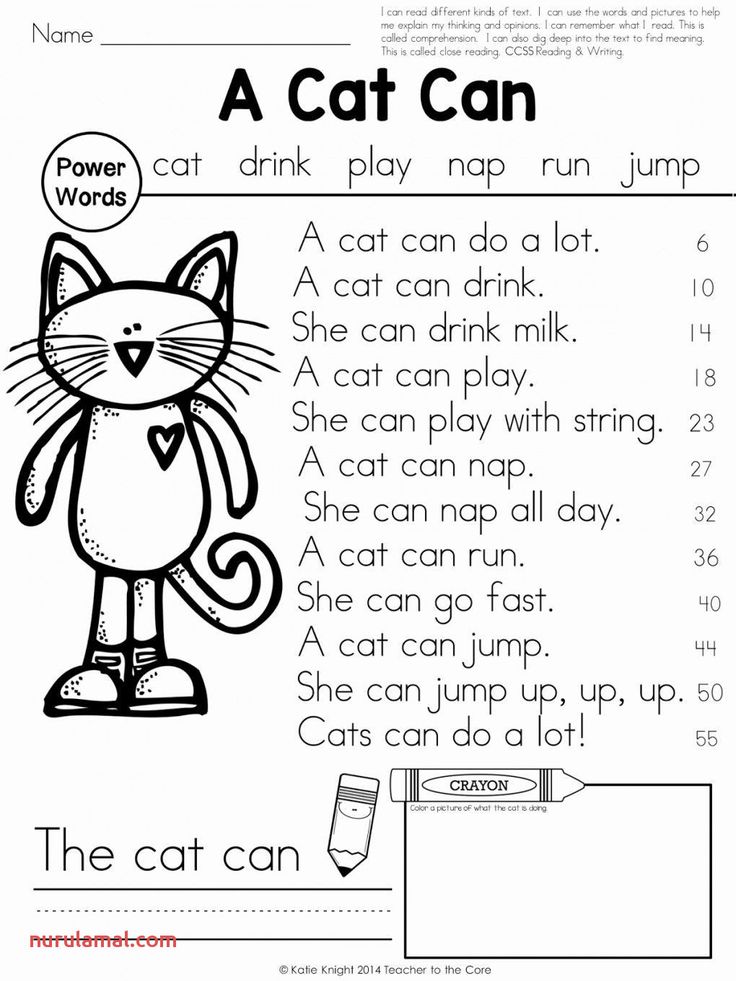

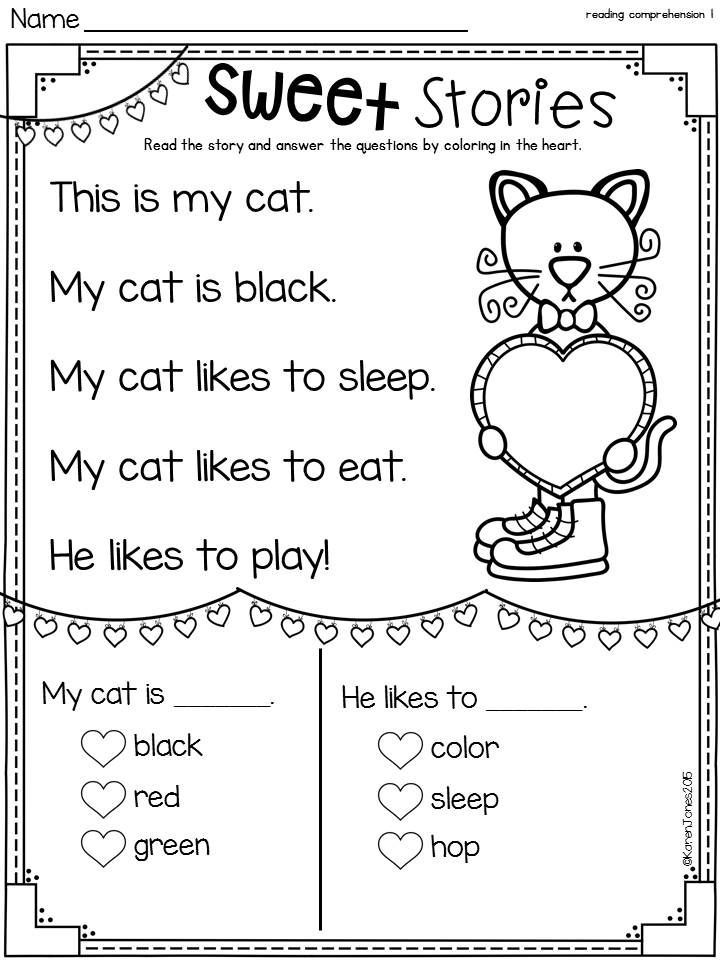

Research shows kids learn to read when they are able to identify letters or combinations of letters and connect those letters to sounds. There’s more to it, of course, like attaching meaning to words and phrases, but phonemic awareness (understanding sounds in spoken words) and an understanding of phonics (knowing that letters in print correspond to sounds) are the most basic first steps to becoming a reader.

If children can’t master phonics, they are more likely to struggle to read. That’s why researchers say explicit, systematic instruction in phonics is important: Teachers must lead students step by step through a specific sequence of letters and sounds. Kids who learn how to decode words can then apply that skill to more challenging words and ultimately read with fluency. Some kids may not need much help with phonics, especially as they get older, but experts say phonics instruction can be essential for young children and struggling readers “We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs,” said Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York, who recently led the transformation of his schools’ reading program to a research-based, structured approach. “But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

How should your child’s school teach reading?

Timothy Shanahan, a professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago and an expert on reading instruction, said phonics are important in kindergarten through second grade and phonemic awareness should be explicitly taught in kindergarten and first grade. This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

This view has been underscored by experts in recent years as the debate over reading instruction has intensified. But teaching kids how to read should include more than phonics, said Shanahan. They should also be exposed to oral reading, reading comprehension and writing.

The wars over how to teach reading are back. Here’s the four things you need to know.

Wiley Blevins, an author and expert on phonics, said a good test parents can use to determine whether a child is receiving research-based reading instruction is to ask their child’s teacher how reading is taught. “They should be able to tell you something more than ‘by reading lots of books’ and ‘developing a love of reading.’ ” Blevins said. Along with time dedicated to teaching phonics, Blevins said children should participate in read-alouds with their teacher to build vocabulary and content knowledge. “These read-alouds must involve interactive conversations to engage students in thinking about the content and using the vocabulary,” he said. “Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

“Too often, when time is limited, the daily read-alouds are the first thing left out of the reading time. We undervalue its impact on reading growth and must change that.”

Rasmussen’s school uses a structured approach: Children receive lessons in phonemic awareness, phonics, pre-writing and writing, vocabulary and repeated readings. Research shows this type of “systematic and intensive” approach in several aspects of literacy can turn children who struggle to read into average or above-average readers.

What should schools avoid when teaching reading?

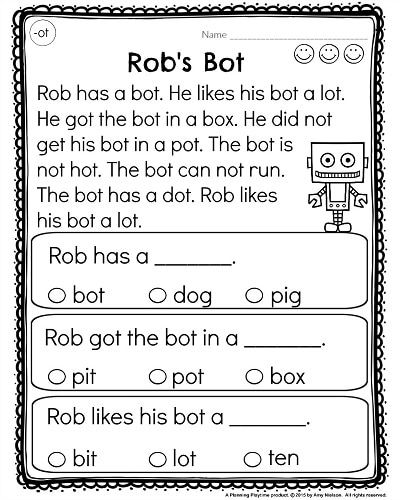

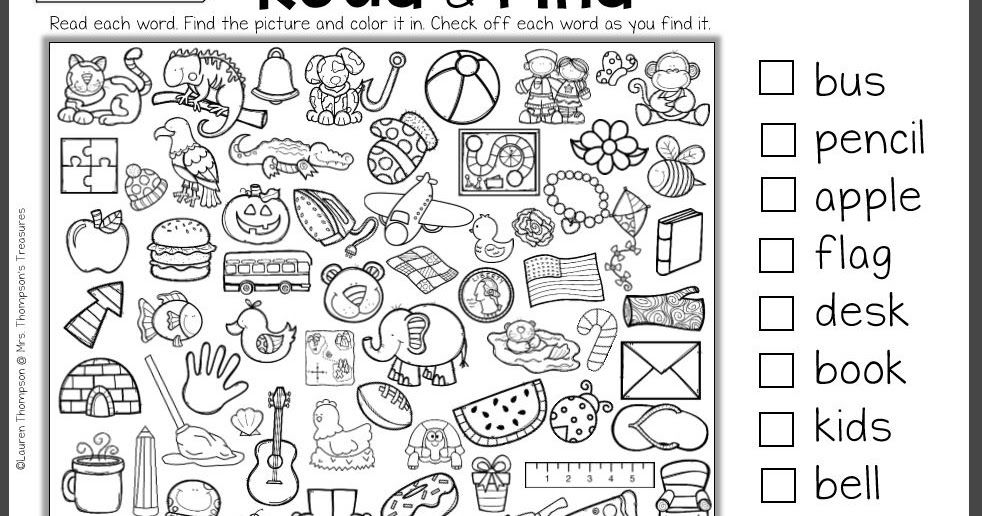

Educators and experts say kids should be encouraged to sound out words, instead of guessing. “We really want to make sure that no kid is guessing,” Rasmussen said. “You really want … your own kid sounding out words and blending words from the earliest level on.” That means children are not told to guess an unfamiliar word by looking at a picture in the book, for example. As children encounter more challenging texts in later grades, avoiding reliance on visual cues also supports fluent reading. “When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

“When they get to ninth grade and they have to read “Of Mice and Men,” there are no picture cues,” Rasmussen said.

Related: Teacher Voice: We need phonics, along with other supports, for reading

Blevins and Shanahan caution against organizing books by different reading levels and keeping students at one level until they read with enough fluency to move up to the next level. Although many people may think keeping students at one level will help prevent them from getting frustrated and discouraged by difficult texts, research shows that students actually learn more when they are challenged by reading materials.

Blevins said reliance on “leveled books” can contribute to “a bad habit in readers.” Because students can’t sound out many of the words, they rely on memorizing repeated words and sentence patterns, or on using picture clues to guess words. Rasmussen said making kids stick with one reading level — and, especially, consistently giving some kids texts that are below grade level, rather than giving them supports to bring them to grade level — can also lead to larger gaps in reading ability.

How do I know if a reading curriculum is effective?

Some reading curricula cover more aspects of literacy than others. While almost all programs have some research-based components, the structure of a program can make a big difference, said Rasmussen. Watching children read is the best way to tell if they are receiving proper instruction — explicit, systematic instruction in phonics to establish a foundation for reading, coupled with the use of grade-level texts, offered to all kids.

Parents who are curious about what’s included in the curriculum in their child’s classroom can find sources online, like a chart included in an article by Readingrockets.org which summarizes the various aspects of literacy, including phonics, writing and comprehension strategies, in some of the most popular reading curricula.

Blevins also suggested some questions parents can ask their child’s teacher:

- What is your phonics scope and sequence?

“If research-based, the curriculum must have a clearly defined phonics scope and sequence that serves as the spine of the instruction. ” Blevins said.

” Blevins said.

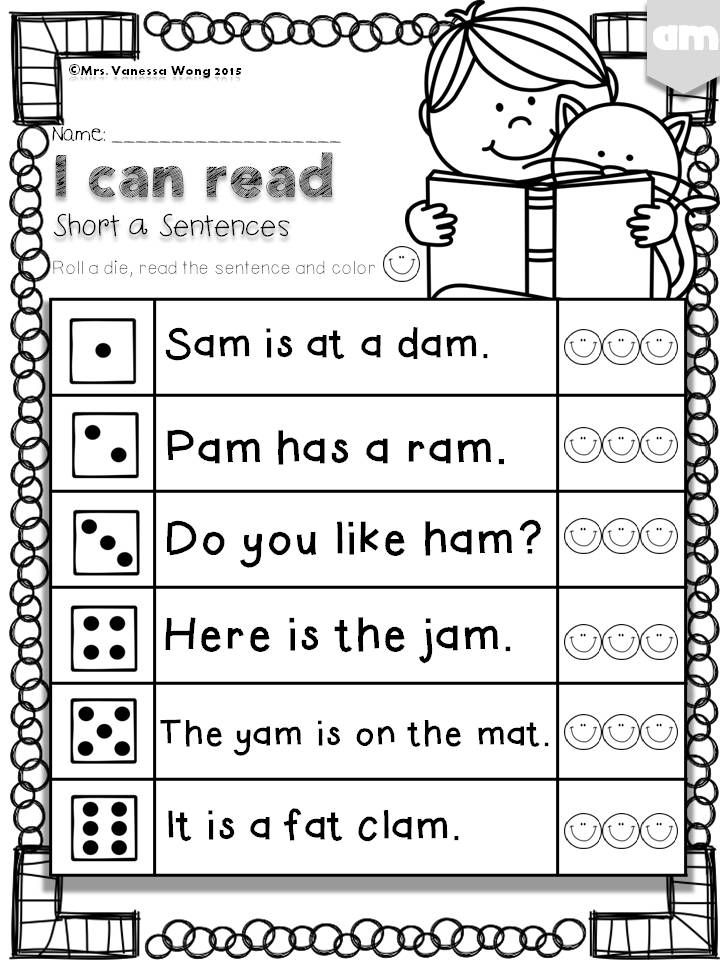

- Do you have decodable readers (short books with words composed of the letters and sounds students are learning) to practice phonics?

“If no decodable or phonics readers are used, students are unlikely to get the amount of practice and application to get to mastery so they can then transfer these skills to all reading and writing experiences,” Blevins said. “If teachers say they are using leveled books, ask how many words can students sound out based on the phonics skills (teachers) have taught … Can these words be fully sounded out based on the phonics skills you taught or are children only using pieces of the word? They should be fully sounding out the words — not using just the first or first and last letters and guessing at the rest.”

- What are you doing to build students’ vocabulary and background knowledge? How frequent is this instruction? How much time is spent each day doing this?

“It should be a lot,” Blevins said, “and much of it happens during read-alouds, especially informational texts, and science and social studies lessons. ”

”

- Is the research used to support your reading curriculum just about the actual materials, or does it draw from a larger body of research on how children learn to read? How does it connect to the science of reading?

Teachers should be able to answer these questions, said Blevins.

What should I do if my child isn’t progressing in reading?

When a child isn’t progressing, Blevins said, the key is to find out why. “Is it a learning challenge or is your child a curriculum casualty? This is a tough one.” Blevins suggested that parents of kindergarteners and first graders ask their child’s school to test the child’s phonemic awareness, phonics and fluency.

Parents of older children should ask for a test of vocabulary. “These tests will locate some underlying issues as to why your child is struggling reading and understanding what they read,” Blevins said. “Once underlying issues are found, they can be systematically addressed. ”

”

“We don’t know how much phonics each kid needs. But we know no kid is hurt by getting too much of it.”

Anders Rasmussen, principal of Wood Road Elementary School in Ballston Spa, New York

Rasmussen recommended parents work with their school if they are concerned about their children’s progress. By sitting and reading with their children, parents can see the kind of literacy instruction the kids are receiving. If children are trying to guess based on pictures, parents can talk to teachers about increasing phonics instruction.

“Teachers aren’t there doing necessarily bad things or disadvantaging kids purposefully or willfully,” Rasmussen said. “You have many great reading teachers using some effective strategies and some ineffective strategies.”

What can parents do at home to help their children learn to read?

Parents want to help their kids learn how to read but don’t want to push them to the point where they hate reading. “Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

“Parents at home can fall into the trap of thinking this is about drilling their kid,” said Cindy Jiban, a former educator and current principal academic lead at NWEA, a research-based non-profit focused on assessments and professional learning opportunities. “This is unfortunate,” Jiban said. “It sets up a parent-child interaction that makes it, ‘Ugh, there’s this thing that’s not fun.’” Instead, Jiban advises making decoding playful. Here are some ideas:

- Challenge kids to find everything in the house that starts with a specific sound.

- Stretch out one word in a sentence. Ask your child to “pass the salt” but say the individual sounds in the word “salt” instead of the word itself.

- Ask your child to figure out what every family member’s name would be if it started with a “b” sound.

- Sing that annoying “Banana fana fo fanna song.” Jiban said that kind of playful activity can actually help a kid think about the sounds that correspond with letters even if they’re not looking at a letter right in front of them.

- Read your child’s favorite book over and over again. For books that children know well, Jiban suggests that children use their finger to follow along as each word is read. Parents can do the same, or come up with another strategy to help kids follow which words they’re reading on a page.

Giving a child diverse experiences that seem to have nothing to do with reading can also help a child’s reading ability. By having a variety of experiences, Rasmussen said, children will be able to apply their own knowledge to better comprehend texts about various topics.

This story about teaching children to read was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

Can your child read and understand the text?. Ekaterina Buneeva's home online literacy school

How to determine if a child understands a read text? This question is very often asked by adults who know how important it is for a child to learn from an early age not just to voice the text or skim through it with his eyes, but to perceive and truly understand.

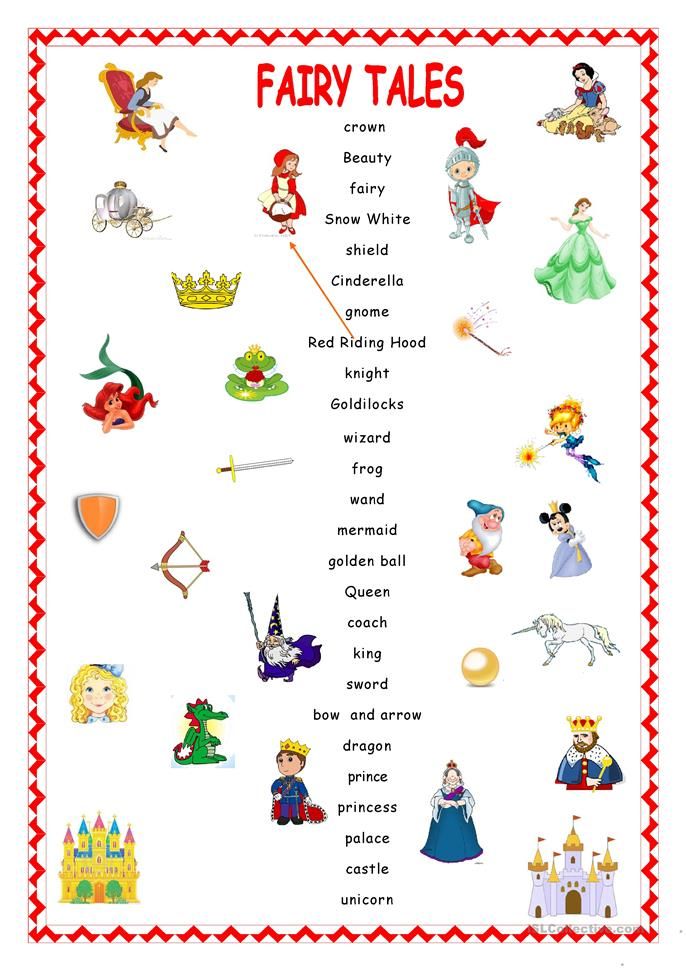

Any text contains three levels of information. On the surface there is always something that is reported in the text directly, explicitly (factual information). Its easier to read. There is subtext information. This is something that is not directly stated, but the reader guesses, as if reading “between the lines”. And there are the main meanings of the text or a certain “main idea” that the reader must independently formulate. And you need to make sure that the child sees all these levels of information in the text.

And there are the main meanings of the text or a certain “main idea” that the reader must independently formulate. And you need to make sure that the child sees all these levels of information in the text.

Here, for example, is a poem by Daniil Kharms.

GOOD DUCK

Crossed the river

Exactly in half a minute:

Chicken on a duckling,

Chicken on a duckling

Chicken on a duckling,

And the chicken on the duck.

What does this text say directly, explicitly? About the fact that a duck, a duckling, a chicken and a chicken crossed the river, and the chicken sat astride the duckling, and the chicken on the duck. And this duck is kind (see the title). Everything seems simple and clear.

And what does the author of the poem inform the reader about implicitly, “between the lines”? The fact that the river is not wide, it is more like a stream, since it was crossed in half a minute, that is, in 30 seconds, very quickly. Also about how the hen and chick can't swim, so they needed help. And the duck and duckling swim well. And they helped the hen and the chicken. That's how much it says! And this fun crossing can be easily imagined by turning on the imagination and drawn.

Also about how the hen and chick can't swim, so they needed help. And the duck and duckling swim well. And they helped the hen and the chicken. That's how much it says! And this fun crossing can be easily imagined by turning on the imagination and drawn.

It is clear that this is a poem-game, the same line is repeated in it, it can be read, cheerfully beating the rhythm, used as a rhyme, etc. And the child should feel it, convey it when reading.

And if we ask the question why the poem is called that and why the duck is kind, what answer will we expect from the child? The duck is kind because it helped the chicken cross the river. But not only for this reason. The meaning of the poem is deeper: after all, the duck is not only kind herself, ready to help, but also taught her duckling kindness.

There are so many meanings in such a small and, at first glance, simple and understandable poem. And if the child saw all this in the text, felt the rhythm and mood, chose, while reading aloud, the appropriate pace of reading and intonation, then he knows how to perceive and understand the text.

If you have a family reading tradition, you can teach your child to read this way. To do this, you need to conduct a dialogue with the author in the course of reading: to see hidden questions in the text and ask them (B), together with the child to assume answers (O) and check yourself in the text, finding the answer (P).

Here's how to read O. Driz's poem "A Sad Day" together.

SAD DAY

(How many questions at once: why is the day sad? For whom? What happened? Must read to understand.)

This day was very sad.

(Q. Why? What happened? It’s hard to guess anything yet, read on.)

It began with grief:

(Q. What's the chagrin? No answers yet, only questions...)

Spoon drowned in a jar

Strawberry jam.

(P. Here it is, grief: the spoon sank ... Q. And how could the spoon sink in a jar of jam? Guessed it? O. The child guesses that the hero of the poem ate jam directly from the jar ...)

New boots coming soon,

Those that gloriously creaked so,

Wet in a deep puddle

And they barely mutter.

(Q. I wonder how they ended up in a puddle? A. The child guesses that the hero of the poem walked through the puddles in new shoes and they got wet. Is this disappointment? Yes, the shoes no longer creak nicely, but “mumble”, wet because. )

Wanted to bathe a kitten -

He dropped the pot on the floor. (Was he going to bathe the kitten in a pot?!)

Nothing succeeded:

Only scratched his hands.

(Q. What scratched it? O. The child guesses that it was the kitten that scratched the boy. By the way, only in this stanza do we understand that the hero of the poem is a boy (he wanted the word, dropped it, scratched it.)

In the evening, lying in bed,

Looked out from under the blanket

I saw a star in the sky

And she immediately fell.

(Q. Is the boy also to blame? A. We listen to the answer of the child.)

After reading, you can talk to your child about why the poem is called that. It says a lot between the lines. Now we understand that this day was sad for the boy, the hero of the poem. But not only because he failed all the time. Look: after all, he did everything that he most likely was not allowed to, and for sure he was scolded or even punished. This is not directly stated in the poem, but the reader guesses. And really a very sad day ... Including for the boy's parents.

Now we understand that this day was sad for the boy, the hero of the poem. But not only because he failed all the time. Look: after all, he did everything that he most likely was not allowed to, and for sure he was scolded or even punished. This is not directly stated in the poem, but the reader guesses. And really a very sad day ... Including for the boy's parents.

© E. V. Buneeva, 2019

How to teach a child to read confidently: 5 tips for parents

What skills should a child develop by the first grade? What place is given to reading among them? The secrets of the formation and development of this most important skill are shared by Marina Kolosova, leading methodologist at the Center for Primary Education of the Prosveshcheniye publishing house.

To teach a child to read quickly and correctly by the first grade is the goal of every parent. I want him to feel confident at this new stage of his life, to be competitive and successful among his classmates. Today, many parents try to develop and prepare their children in advance by improving their reading speed even before they enter the first grade, although teaching the basics of reading and writing has traditionally been one of the main goals of elementary school. How justified is this approach?

Today, many parents try to develop and prepare their children in advance by improving their reading speed even before they enter the first grade, although teaching the basics of reading and writing has traditionally been one of the main goals of elementary school. How justified is this approach?

In fact, today there are no such requirements for the ability to read and write, without which the child could not go to the first grade. There are two parallel lines: the first is from the side of parents: they would like their children to come to school prepared and become successful there. On the other hand, there are no exams or knowledge requirements without which a child will not enter the first grade. He does not have to be able to write and read, the only thing he needs is to be emotionally and socially ready for the first grade, ready to participate, interact, listen to the teacher. And to read and write it, as in our childhood, they will teach at school.

Moreover, teachers in elementary grades often face the fact that before school the child has learned to read incorrectly, and he has to be re-taught. Today, the situation when the entire first class in its entirety would be able to read immediately, on the very first day, is practically impossible. However, no one forbids parents to send their children to developmental circles and teach something in advance, as well as send them to specialized schools. But even there, the impossible is unlikely to be demanded from the child, therefore, parents who decide to engage in early development should not rush their children and expect them to learn everything at once.

Today, the situation when the entire first class in its entirety would be able to read immediately, on the very first day, is practically impossible. However, no one forbids parents to send their children to developmental circles and teach something in advance, as well as send them to specialized schools. But even there, the impossible is unlikely to be demanded from the child, therefore, parents who decide to engage in early development should not rush their children and expect them to learn everything at once.

What should parents pay attention to first of all?

Don't forget that quality is more important than quantity

Today, the diagnosis of reading technique is not at all necessary. No one will blame you for the fact that your child read 49 words per minute, not 50. Now both the Federal State Educational Standards and the recommendations for teachers and parents state that you should not increase the speed, but read correctly, carefully. Then you will develop not a subject skill (quick reading), but the mental processes necessary for this. If the focus has shifted from reading speed, this does not mean that it is not particularly important. You just don’t need to chase only after it, and over time this quality will improve on its own.

Develop memory and attention

To make learning to read easier, you need to train the memory and attention of the child, expand the square that the child covers with one eye, ask what he just read, without rereading. This will help you learn to concentrate on letters, words, and sentences. Exercises with a game will also be useful, where you need to recognize the contours of letters, to cover the entire word when reading. You can offer your child different games for making words from parts.

Do not rush the child and do not raise expectations

Sometimes parents rush the child too much, remembering what they or your neighbor's children could do at his age. In an effort to meet inflated expectations (perhaps far-fetched by himself), the child will try to read faster than his abilities allow. This leads to errors: he can swallow the endings or invent the second half of the word, trying to guess. Don't make your child pretend they can read the fastest. Explain to him that it is better to move along the line a little slower, but more carefully. Offer him a game where you need to choose the correct endings for words, show the same word in different numbers and cases, and ask how these options differ.

This leads to errors: he can swallow the endings or invent the second half of the word, trying to guess. Don't make your child pretend they can read the fastest. Explain to him that it is better to move along the line a little slower, but more carefully. Offer him a game where you need to choose the correct endings for words, show the same word in different numbers and cases, and ask how these options differ.

Pay attention to the meaning of what they read

If the child makes mistakes or reads quickly but does not remember what the text was about, discuss the content and meaning of phrases and texts with him more often. Perhaps you gave him too difficult material. Ask yourself more often whether all the words are clear to him, whether he perceives them entirely, whether he grasps the meaning of the sentence. Expand his vocabulary, offer to select synonyms and antonyms for words, suitable adjectives for nouns. Come up with a child with a series of words that differ by one letter (for example, pillar-table-groan-elephant-slope), show the words with the same root and ask how they are similar and different in meaning. Offer the child a text in which you need to find the answer to some question, as is done in tests in foreign languages.

Offer the child a text in which you need to find the answer to some question, as is done in tests in foreign languages.

Work on your grammar

It can also be helpful to play grammar constructions to improve your understanding of texts. And for this it is not at all necessary to explain the concepts of "subject" or "circumstance". But from understanding what happened and what the text says, you can move on to discussing who did what in this sentence. You can play a game by building a building out of bricks. To do this, use the bricks "who" or "what", "what did." For example, a cat ate a sausage. Add definitions, circumstances, let the child build a more complicated sentence out of them: “Our cat ate delicious sausage yesterday” or “soft butter”. Play at making sentences from disparate words, harmonize them with each other by putting them in the right form.

Parents should not worry if the child is still reading slowly, it is better to pay attention to the development of his mental skills - attention, memory, recognition of symbols and translation of symbols into meanings.