Article on reading strategies

4 Reading Strategies to Retire This Year (Plus 6 to Try Out!)

As a novice teacher, Timothy Shanahan recalls doing round robin reading with his third-grade students—even though his professors in graduate school strongly advised against it, and he vividly remembered his own negative feelings about the practice, he confesses in a 2019 blog post.

“I used it because it kept the kids on task, I could be sure they read the text, and frankly, I didn’t know what else to do,” writes Shanahan, distinguished professor emeritus at the University of Illinois at Chicago and former director of reading for Chicago Public Schools. “I was wrong. … They were telling me not to do it 50 years ago, but these days round robin appears to still be de rigueur, and it will be 50 years from now if we don’t end it ourselves.”

It’s not uncommon for classroom literacy practices to stick around in spite of, as in the case of round robin, well-established research and readily available resources offering a variety of research-based alternatives for improving reading fluency and deepening comprehension and engagement. In fact, when literacy specialists Gwynne Ellen Ash, Melanie R. Kuhn, and Sharon Walpole surveyed teachers and literacy coaches to more deeply understand “the persistence of Round Robin Reading in public schools in the United States,” they found that close to half of the 80 teachers they surveyed admitted to using some variation of round robin, and more than 30 percent “acknowledged that the research said Round Robin Reading was not best practice but they used it anyway.”

As students return to school and educators begin to plan for instruction that adequately challenges kids but also catches them up after a year of uneven pandemic learning, there’s a valuable opportunity to reconsider—and ultimately retire—some of the stale literacy practices that research suggests aren’t the best use of limited instructional time. We combed through our Edutopia archives to find practices that shouldn’t make the cut and selected more effective alternatives that come recommended by literacy experts and experienced educators.

4 LITERACY PRACTICES TO RETIRE

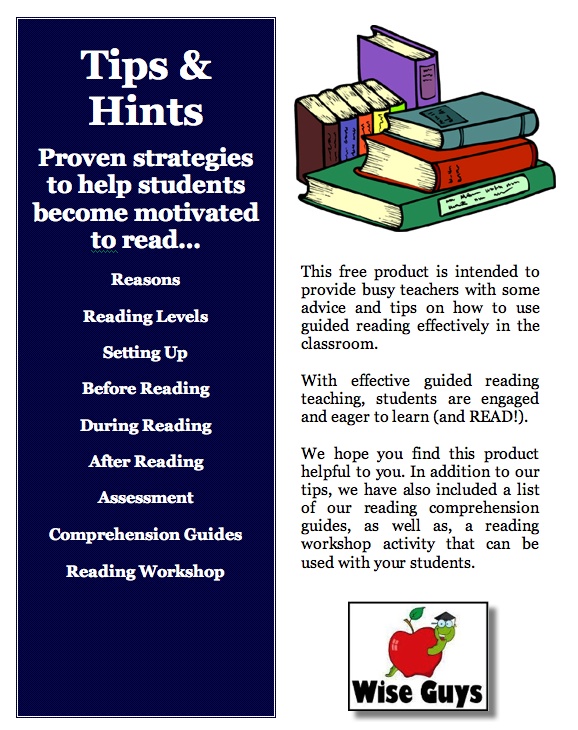

Reading logs (and other rote accountability tasks): Like many teachers, Allie Thrower had her fifth-grade students fill out daily reading logs as part of their homework. But after some time, Thrower, now an elementary school continuous improvement coach, noticed that her students’ log entries looked the same each day. “It was always 20 [minutes],” Thrower writes. “My students seemed to be reading merely because they had to—not because it opened up windows to the world, because reading about a character who looked like them brought them a sense of belonging and hope, or because they wanted to learn how to change the world for the better.”

After discussing the topic with colleagues and digging into the research, she realized that “many parents and educators had strong negative feelings about reading logs,” Thrower writes. And a 2012 study of the practice found that “students with mandatory logs expressed declines in both interest and attitudes towards recreational reading in comparison to peers with voluntary logs, and attitudes towards academic reading decreased significantly. ”

”

Turn-taking oral reading practices: In this type of practice—round robin reading is probably the most common; similar approaches include popcorn reading, combat reading, and Popsicle stick reading—students “read orally from a common text, one child after another, while the other students follow along in their copies of the text,” writes Todd Finley, a professor of English education at East Carolina University. Finley surveyed more than 30 studies and articles about this close-knit family of reading strategies and concluded that oral turn-taking reading practices like round robin stigmatize poor readers, weaken comprehension, and sabotage fluency and pronunciation.

“To be clear, oral reading in other formats does improve students’ fluency, comprehension, and word recognition, though silent or independent reading should occur far more frequently as students advance into the later grades,” Finley notes.

Awarding prizes for reading: In a well-intentioned effort to motivate students to read more, schools and teachers sometimes offer prizes for meeting reading goals—rewards might range from small items like stickers or bracelets to movie or amusement park tickets, gaming tokens, and fast food coupons. But research shows that extrinsic motivators like these don’t do much to build reading habits and, especially among students who already enjoy reading, may actually decrease motivation to read, say literacy experts Barbara A. Marinak and Linda B. Gambrell, authors of No More Reading for Junk: Best Practices for Motivating Readers, in an interview for Education Week. Instead, offer rewards that are closely aligned with reading, like books they can keep and extra reading time, for example.

But research shows that extrinsic motivators like these don’t do much to build reading habits and, especially among students who already enjoy reading, may actually decrease motivation to read, say literacy experts Barbara A. Marinak and Linda B. Gambrell, authors of No More Reading for Junk: Best Practices for Motivating Readers, in an interview for Education Week. Instead, offer rewards that are closely aligned with reading, like books they can keep and extra reading time, for example.

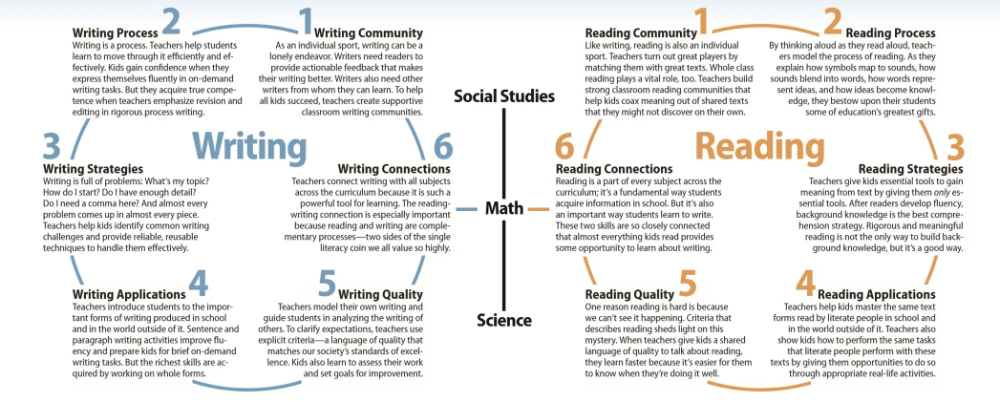

Overemphasis on reading as a discrete skill: Traditional ELA reading curriculum tends to focus on exposing students to unfamiliar subjects while teaching them ostensibly transferable skills like summarizing and finding the main idea. But a growing group of educators, writes journalist Holly Korbey, are shifting away from this approach, based on research indicating that predominantly skills-based instruction does little to improve overall reading proficiency for many students.

In the landmark baseball study, for example, Donna Recht and Lauren Leslie found that “struggling readers who knew a lot about baseball did better on a reading comprehension test about the topic than strong readers who knew nothing about the sport,” Korbey writes. Similarly, high school students who “met a basic knowledge threshold on a dense topic like ecosystems had much stronger performance on a reading test about ecosystems than those who didn’t,” she notes. “For low-income students and students of color, these disparities were particularly pronounced.”

6 READING APPROACHES THAT WORK BETTER

Reading accountability partners: After quitting reading logs, Thrower tried several alternatives before settling on reading accountability partners, a strategy where partners meet daily for 10 minutes to discuss the previous day’s reading. “The practice may seem simple, but the results have been impressive,” Thrower says, noting that pairings work best with students who will challenge each other academically and encourage each other emotionally.

Via mini-lessons, she helps students understand their roles, discusses how to hold peers accountable and how to be receptive to feedback, sets kids up with guiding questions, and circulates among the groups to make sure everyone’s on task.

Choral reading: In this oral reading activity, the teacher and class read a passage aloud together, reducing “struggling readers’ public exposure” and extending the length of the passages that kids are exposed to, writes Finley. Or try a variation on choral reading in which “every time the instructor omits a word during oral reading, students say the word all together,” Finley suggests. Lowering the stakes for all students in this way allows everyone to practice reading for longer chunks of time and smooths out modeling hiccups and individual fluency issues. The research, meanwhile, shows that the practice results in marked improvements in decoding and fluency.

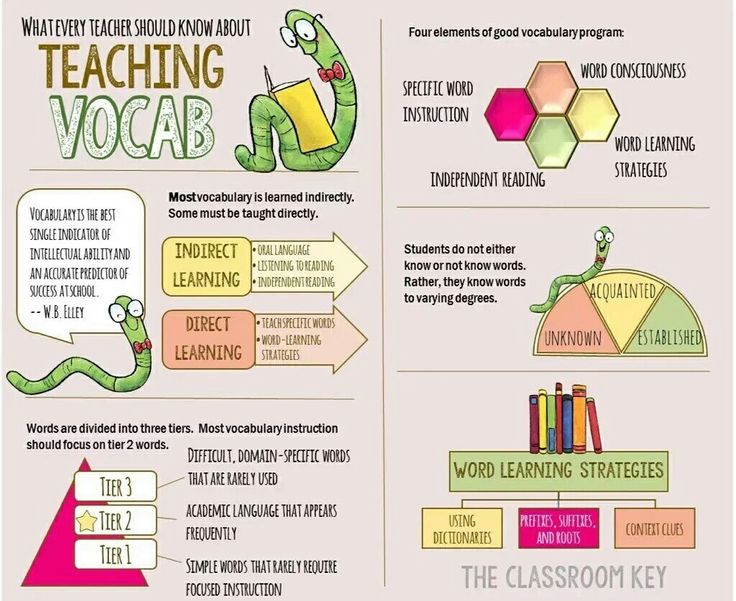

Scaffolded silent reading: Silent reading is important, but before sending kids off with a book, consider scaffolding the activity by pre-teaching vocabulary, providing a plot overview, and maybe introducing a K-W-L activity.

“Many of us, myself included, are guilty of sending students all alone down the bumpy, muddy path known as Challenging Text—a road booby-trapped with difficult vocabulary,” writes Rebecca Alber, an instructor at UCLA’s Graduate School of Education. “We send them ill-prepared and then are often shocked when they lose interest, create a ruckus, or fall asleep.” When pre-teaching vocabulary, “introduce the words to kids in photos or in context with things they know and are interested in,” Alber suggests. “Give time for small-group and whole-class discussion of the words.”

Teacher read-aloud and modeling: It’s tough to find time in the school day for read-alouds; however, “reading aloud to students each day is not only a productive investment; it also has powerful benefits for learners of all ages,” writes educator Christie Rodgers, who routinely alloted five to seven minutes to the task every day with her fourth- and fifth-grade students. It’s a practice that’s rewarding and beneficial for middle and high school students as well.

“Throughout my 25 years in education, the read-aloud was my way of getting the most stubborn students to fall in love with reading,” says Rodgers. Besides being enjoyable—a 2019 report from Scholastic found that 83 percent of students ages 6 all the way to age 17 surveyed said that being read to was something they either loved or liked a lot—it’s also a powerful opportunity to model reading strategies, stopping frequently to wonder out loud and thus showing students “what good readers do when they don’t know a word, understand a plot twist, or agree with a character in the story,” Rodgers writes.

Reading buddies: For this practice, pair upper-grade classes with lower-grade ones—third graders with pre-K students, for example—and plan to set aside at least one 30-minute session per month for students to read together. Kids can work in pairs, but groups of three work too. “Let the younger students pick the books at first so they get hooked with an interesting read,” says Ryan Wheeler, a behavior specialist in Houston, Texas.

The practice builds community, but it’s also a powerful literacy tool. “Reading buddies allows younger readers to see what being fluent looks like as they have a peer model demonstrating reading skills,” notes Wheeler. “For upper elementary students who are struggling with grade-level reading, the opportunity to access easier reading material without stigma or shame while sharing with a novice reader can create a positive experience with an activity that may otherwise be less than enjoyable.”

Building background knowledge: Background knowledge—about the topic and about the world in general—“plays an important role in helping students make sense of a text because the things readers already know work like a scaffold on which to build a more complete, and nuanced, mental model of the subject matter,” writes Holly Korbey. Try pre-teaching key vocabulary and concepts, and reduce the cognitive load by linking the new, unfamiliar material to material they’ve already learned.

In order to teach the kind of knowledge-rich lessons that will effectively boost students’ reading comprehension, cognitive psychologist Daniel Willingham, author of The Reading Mind: A Cognitive Approach to Understanding How the Mind Reads, tells Korbey, “teachers should emphasize a cohesive, well-sequenced curriculum with lots of background information on different topics embedded within it so that no students are left hanging when they read.”

Ultimately, beyond abandoning ineffective practices, the deeper work of motivating kids to read starts with connecting them to books that genuinely reflect their own interests—and giving them some choice in the matter. This may require being flexible about reading levels so kids are exposed to texts that provide them with an abundance of cultural, racial, and socioeconomic perspectives and cater to a wide variety of reading tastes across a broad range of reading levels—from books that are easy to read to ones that pull them into unfamiliar and demanding territory.

When we provide young readers with a rich mix of books, Melanie Hundley, a former English teacher and now professor at Vanderbilt University, tells Korbey, it primes students to feel more engaged and excited to take on tougher texts. “If kids will read and you can build their reading stamina, they can get to a place where they’re reading complex texts,” says Hundley. “Choice helps develop a willingness to read… [and] I want kids to choose to read.”

Seven Strategies to Teach Students Text Comprehension

1. Monitoring comprehension

Students who are good at monitoring their comprehension know when they understand what they read and when they do not. They have strategies to "fix" problems in their understanding as the problems arise. Research shows that instruction, even in the early grades, can help students become better at monitoring their comprehension.

Comprehension monitoring instruction teaches students to:

- Be aware of what they do understand

- Identify what they do not understand

- Use appropriate strategies to resolve problems in comprehension

2.

Metacognition

MetacognitionMetacognition can be defined as "thinking about thinking." Good readers use metacognitive strategies to think about and have control over their reading. Before reading, they might clarify their purpose for reading and preview the text. During reading, they might monitor their understanding, adjusting their reading speed to fit the difficulty of the text and "fixing" any comprehension problems they have. After reading, they check their understanding of what they read.

Students may use several comprehension monitoring strategies:

- Identify where the difficulty occurs

"I don't understand the second paragraph on page 76."

- Identify what the difficulty is

"I don't get what the author means when she says, 'Arriving in America was a milestone in my grandmother's life.'"

- Restate the difficult sentence or passage in their own words

"Oh, so the author means that coming to America was a very important event in her grandmother's life.

"

" - Look back through the text

"The author talked about Mr. McBride in Chapter 2, but I don't remember much about him. Maybe if I reread that chapter, I can figure out why he's acting this way now."

- Look forward in the text for information that might help them to resolve the difficulty

"The text says, 'The groundwater may form a stream or pond or create a wetland. People can also bring groundwater to the surface.' Hmm, I don't understand how people can do that… Oh, the next section is called 'Wells.' I'll read this section to see if it tells how they do it."

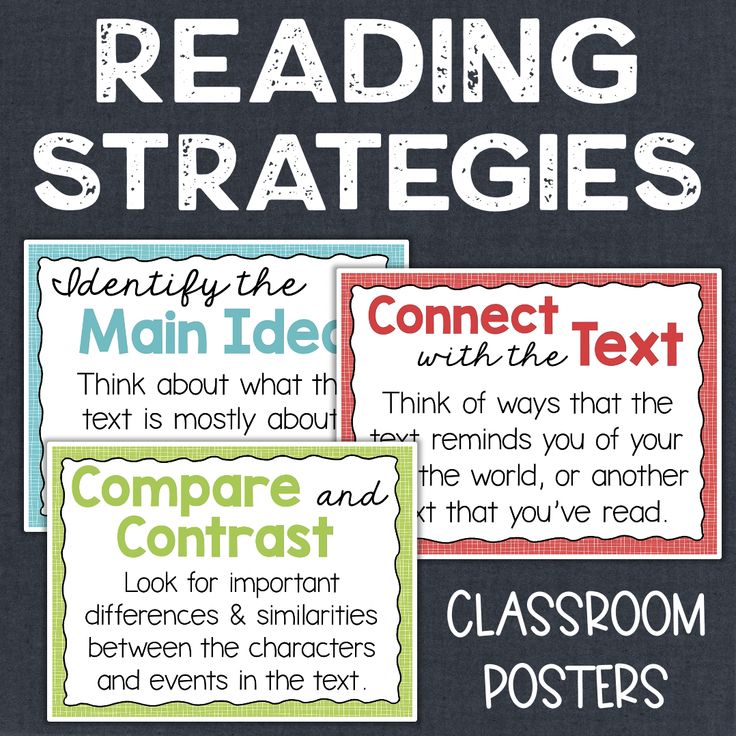

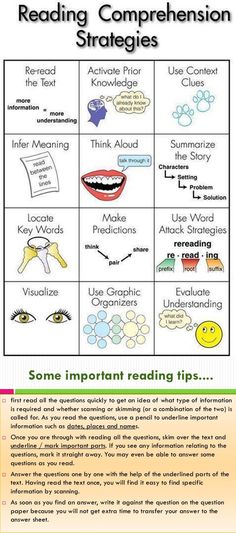

3. Graphic and semantic organizers

Graphic organizers illustrate concepts and relationships between concepts in a text or using diagrams. Graphic organizers are known by different names, such as maps, webs, graphs, charts, frames, or clusters.

Regardless of the label, graphic organizers can help readers focus on concepts and how they are related to other concepts. Graphic organizers help students read and understand textbooks and picture books.

Graphic organizers help students read and understand textbooks and picture books.

Graphic organizers can:

- Help students focus on text structure differences between fiction and nonfiction as they read

- Provide students with tools they can use to examine and show relationships in a text

- Help students write well-organized summaries of a text

Here are some examples of graphic organizers:

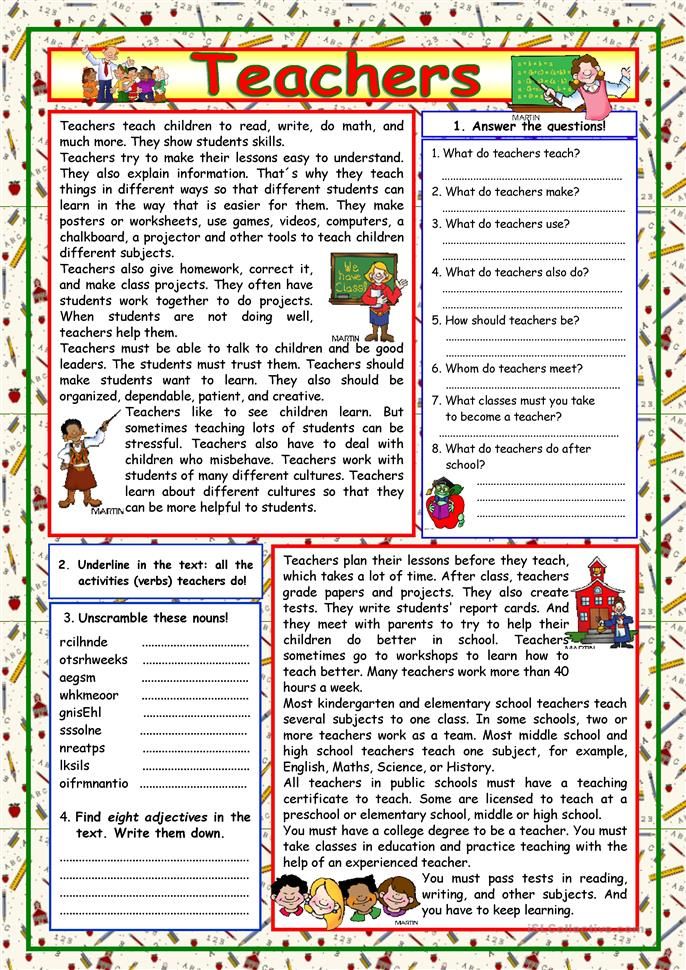

4. Answering questions

Questions can be effective because they:

- Give students a purpose for reading

- Focus students' attention on what they are to learn

- Help students to think actively as they read

- Encourage students to monitor their comprehension

- Help students to review content and relate what they have learned to what they already know

The Question-Answer Relationship strategy (QAR) encourages students to learn how to answer questions better. Students are asked to indicate whether the information they used to answer questions about the text was textually explicit information (information that was directly stated in the text), textually implicit information (information that was implied in the text), or information entirely from the student's own background knowledge.

There are four different types of questions:

- "Right There"

Questions found right in the text that ask students to find the one right answer located in one place as a word or a sentence in the passage.

Example: Who is Frog's friend? Answer: Toad

- "Think and Search"

Questions based on the recall of facts that can be found directly in the text. Answers are typically found in more than one place, thus requiring students to "think" and "search" through the passage to find the answer.

Example: Why was Frog sad? Answer: His friend was leaving.

- "Author and You"

Questions require students to use what they already know, with what they have learned from reading the text. Students must understand the text and relate it to their prior knowledge before answering the question.

Example: How do think Frog felt when he found Toad? Answer: I think that Frog felt happy because he had not seen Toad in a long time. I feel happy when I get to see my friend who lives far away.

- "On Your Own"

Questions are answered based on a student's prior knowledge and experiences. Reading the text may not be helpful to them when answering this type of question.

Example: How would you feel if your best friend moved away? Answer: I would feel very sad if my best friend moved away because I would miss her.

5. Generating questions

By generating questions, students become aware of whether they can answer the questions and if they understand what they are reading. Students learn to ask themselves questions that require them to combine information from different segments of text. For example, students can be taught to ask main idea questions that relate to important information in a text.

6. Recognizing story structure

In story structure instruction, students learn to identify the categories of content (characters, setting, events, problem, resolution). Often, students learn to recognize story structure through the use of story maps. Instruction in story structure improves students' comprehension.

Instruction in story structure improves students' comprehension.

7. Summarizing

Summarizing requires students to determine what is important in what they are reading and to put it into their own words. Instruction in summarizing helps students:

- Identify or generate main ideas

- Connect the main or central ideas

- Eliminate unnecessary information

- Remember what they read

Effective comprehension strategy instruction is explicit

Research shows that explicit teaching techniques are particularly effective for comprehension strategy instruction. In explicit instruction, teachers tell readers why and when they should use strategies, what strategies to use, and how to apply them. The steps of explicit instruction typically include direct explanation, teacher modeling ("thinking aloud"), guided practice, and application.

- Direct explanation

The teacher explains to students why the strategy helps comprehension and when to apply the strategy.

- Modeling

The teacher models, or demonstrates, how to apply the strategy, usually by "thinking aloud" while reading the text that the students are using.

- Guided practice

The teacher guides and assists students as they learn how and when to apply the strategy.

- Application

The teacher helps students practice the strategy until they can apply it independently.

Effective comprehension strategy instruction can be accomplished through cooperative learning, which involves students working together as partners or in small groups on clearly defined tasks. Cooperative learning instruction has been used successfully to teach comprehension strategies. Students work together to understand texts, helping each other learn and apply comprehension strategies. Teachers help students learn to work in groups. Teachers also provide modeling of the comprehension strategies.

Effective strategies for working with text in the classroom at school

The ultimate goal of teaching Russian is practical literacy and language competence. The basis of the content of literature as an academic subject is reading and textual study of works of art.

The basis of the content of literature as an academic subject is reading and textual study of works of art.

Work with the text as the main didactic unit allows schoolchildren to combine the activities of developing practical skills of literate writing and speech development.

Every teacher dreams that all students come to the lesson prepared: they have completely read this or that work or paragraph. And not just read, but understood the meaning of the text read. During the final certification, the graduate must also understand the meaning of the read text. Whether it is a task to the text or the text itself.

Teachers working in grades 9 and 11 know that most mistakes are made due to misunderstanding of what is read, as well as when reading the assignment itself.

Teaching a child to read “correctly”, “effectively”, “productively” is an important task for a teacher. That is why the technology of productive reading (PRT), developed by Professor N. Svetlovskaya, acquires a leading role and contributes to the achievement of the results that are mentioned in the new standards.

The technology is universal and can be used in lessons of any cycle.

It is aimed at the formation of all universal educational activities: cognitive, communicative, regulatory, personal.

The technology of productive reading differs sharply from the traditional technology of transferring ready-made knowledge to a student. The teacher organizes the children's research work in such a way that they themselves "think" about solving the key problem of the lesson and can themselves explain how to act in new conditions. The teacher becomes a partner, a mentor, an observer.

The developed technology includes three stages of working with text, a three-stage process.

The goal of is the development of anticipation (the ability to guess, predict the content of the text). Task - to develop motivation for reading the text

1. Strategy "Forecast by headline".

Task: think about what can be discussed in the story of K.G. Paustovsky "Warm bread", in the work of P.P. Bazhov "Mistress of the Copper Mountain", etc.

– Try to predict the content by the first line of the story…Remember the name of the story….Does the content of the story match the title?

Give examples of such discrepancies.

Associative bush (circle, row). Today we will read and discuss the topic… What associations do you have about the stated topic?

2. Strategy "Brainstorm" ("Basket of ideas").

Task: answer the questions before reading the text (fairy tales "Warm bread") - What do you know about K. G. Paustovsky? What do you think the story will be about? Who can be the main character? What event in the story can be described.

3. Strategy "Image of the text".

Task: check your assumptions. Based on the words taken from the text, try to make a short plot story. The title of the story is given.

4. Strategy "Battery of questions".

Task: make up questions to the text according to the title, according to the illustrations.

5. Glossary strategy.

Task: look at the list of words and mark those that can be related to the text. When you finish reading the text, go back to these words and look at their meaning and the use of words used in the text.

6. "Competing with the writer" strategy.

Task: try to predict the content of the book by looking at the illustrations. One student offers his version, the rest complete it.

7. Strategy "True and False Statements".

8. Strategy I know, I want to know, I found out.

Stage 2 - stage of text activity.

The purpose of is to understand the text and create its reader's interpretation, summarizing part of the read text, asking questions of a general nature, making assumptions about the further development of the plot and the role of characters in the composition of the text, etc.).

The main task of is to ensure the full perception of the text. The main strategies at the stage of text activity are dialogue with the author, commented reading.

1. Strategy "Reading in a circle". The text is read in turn (each "circle member" reads a paragraph). After this, a stop follows: everyone asks questions to the read passage. If the question cannot be answered (it does not correspond to the text), then the question is considered incorrect. * All correct questions can be recorded.

2. Silent reading with questions strategy.

3. Strategy “Reading to yourself with notes. (Insert)" . Marginal notes: + - knew; - - new; ? - Interesting; V is unclear. Others are possible: B - question; O - answer; Z - I know; N - new; And - interesting; X - I want to know; C - ask; U to clarify.

4. Strategy "Reading with stops". Reading the text with stops, during which tasks are given in the form of questions: some are aimed at checking understanding, others - at predicting the content of the next passage.

5. "Pose a problem - offer a solution" strategy. Remember what problems the heroes of the work face (the problem is formulated and written down in an oval). Next, the children can name several problems, students are divided into groups and offer all kinds of solutions to problems.

6. Strategy "Creating a question plan". The student carries out a semantic grouping of the text, highlights the strong points, divides the text into semantic parts and titles each part with a key question…….

Stage 3 – stage of post-text (post-text) activity.

The purpose of is to correct the reader's interpretation in accordance with the author's meaning.

The main task of is to provide in-depth perception and understanding of the text, to raise a question to the text as a whole, followed by a conversation, the result of which should be an understanding of the author's meaning. Re-addressing the title, illustrations, performing creative tasks.

2. Question tree strategy Crown – what? Where? When? Barrel - why? How? Could you? Roots - how to relate the text to life? With current events? What is the author trying to show?

3. Strategy "Bloom's Cube" (Benjamin Bloom is a famous American teacher, author of many pedagogical strategies = technician).

The beginnings of the questions are written on the faces of the cube: “Why?”, “Explain”, “Name”, “Suggest”, “Think up”, “Share”. The teacher or student rolls the die.

It is necessary to formulate a question to the educational material on the side on which the cube fell.

The “Name” question is aimed at the level of reproduction, i.e. at the simple reproduction of knowledge.

Question "Why" - the student in this case must find cause-and-effect relationships, describe the processes occurring with a certain object or phenomenon.

“Explain ” question – student uses concepts and principles in new situations.

All of the above strategies provide for serious work with the text, its deep analysis and understanding, the organization of independent cognitive activity of students on educational material. socially moral experience and makes you think, knowing the world around you.

Technology Advantage:

1. Applicable in the lessons of any cycle and at any level of education.

2. Focused on personal development.

3. Develops the ability to predict the results of reading.

4. Promotes understanding of the text in the lesson.

Articles on the topic

- RAFT technique in Russian language and literature classes

- TRIZ pedagogy techniques in speech development lessons in elementary school

- 4 quick reading techniques for educational and scientific literature

- How to analyze literary texts using the Russian National Corpus

- 5 exercises to develop creative thinking

- Important to know: amazing brain rules that improve learning

Strategies for teaching meaningful reading | Article on the topic:

Municipal Autonomous Educational Organization

Secondary school No. 3 of the city of Ruza

143100 Moscow Region, Tel./Fax 8 (496) 272 30-06

Volokolamsk highway, house 4 e-mail: [email protected]

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________0007

STUDENT COUNCIL – ROUND TABLE

“RESOURCES OF A MODERN LESSON THAT ENSURE THE MASTERING OF NEW EDUCATIONAL STANDARDS. PEDAGOGICAL TECHNOLOGIES»

ACTIVITY APPROACH IN LEARNING

Teaching semantic reading. Strategies for pre-text, text and post-text activities

Teacher of the Russian language and literature

Makina Natalia Mikhailovna

December 29, 2018

mastering the skills of semantic reading of texts of various styles and genres. According to scientists, it is semantic reading that can become the basis for the development of value-semantic personal qualities of a student, reliable support for successful cognitive activity throughout his life.

The task - to teach to understand, analyze, interpret the text in familiar and unfamiliar cognitive situations for students - is becoming one of the most urgent tasks of the modern school.

Semantic (productive) reading is a type of reading that is aimed at understanding the semantic content of the text by the reader. In the concept of universal educational activities (AG Asmolov, GV Burmenskaya, IA Volodarskaya, etc. ) semantic reading activities are identified, related to:

- understanding the purpose of reading and choosing the type of reading depending on the purpose;

- extracting the necessary information from the listened texts of various genres;

- definition of primary and secondary information;

- by formulating the problem and the main idea of the text.

The purpose of semantic reading is to understand the content of the text as accurately and completely as possible, to catch all the details and practically comprehend the information. This is a careful "reading" and penetration into the meaning of the text through its analysis. Possession of semantic reading skills contributes to the development of oral speech and, as a result, written speech and productive learning. The development of the ability of semantic reading helps to master the art of analytical, interpretive and critical reading.

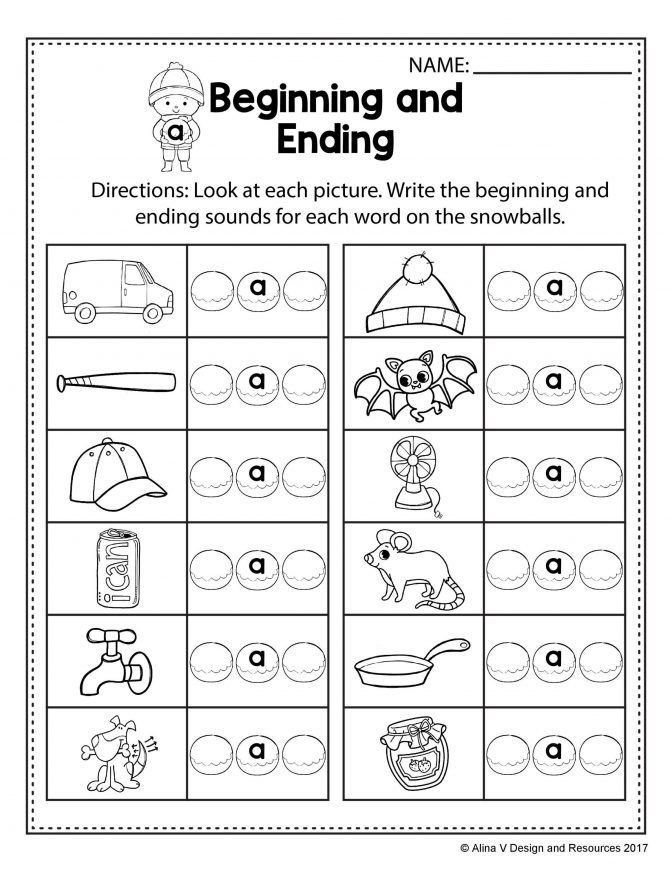

How to help a primary school student to master “the skills of meaningful reading of texts of various styles and genres”? One of the main ways to develop reading literacy is a strategic approach to teaching meaningful reading.

According to N. Smetannikova's definition, "the way, the reader's program of actions for processing various information of the text is a strategy." Reading strategies are an algorithm of mental actions and operations in working with text. By ensuring its understanding, they help to master knowledge better and faster, retain it longer, and foster a culture of reading.

Traditionally, the method of working with text was based on the scheme "Read the text" - "Answer the questions (mainly of a reproductive nature)". When implementing the activity approach, working with the text includes seven steps that the reader must complete:

Pre-text activity:

- Setting the goal of reading

- Determining the nature of the text

- Viewing the heading and subheadings

- Making a decision about the author’s intention

- 02 about the type of reading, the beginning of activity

Text activity:

- Proposing hypotheses that are refuted or confirmed in the process of activity

Post-text activity:

- Thinking about the text and performing reproductive, productive, communicative, creative tasks.

For each of the steps, you can choose your own strategies, and we will focus on some of them today.

Strategy of pre-text activity "Landmarks of anticipation"

This strategy is similar to the children's game "Do you believe?", but the question is worded slightly differently: "Do you agree?". The goal of the strategy is to update readers' existing knowledge on the topic. For work, a table is presented, the central column of which is filled with judgments prepared by the teacher on the topic of the text. At the pre-text stage, the student must mark in the left column those judgments with which he agrees.

| Before reading | Judgment

| After reading |

| There are at least two ideas about how the universe works. | ||

| The achievements of modern physics have made it possible to find answers to all questions about the origin of the Universe. | ||

| The idea that the Earth is not flat was scientifically substantiated by modern European scientists. | ||

| The experience of the ancient Greek sea voyages confirms the idea that the Earth is round. |

At the post-text stage, students fill in the right column, find discrepancies in answers, and explain the reasons for this.

Strategies of textual activity

Numerous works of recent years state that students have difficulty reading even not very voluminous texts. Often this is due to the fact that readers very quickly move from studying reading to viewing reading, transferring “screen” reading techniques (the “five-line” principle) to reading “paper” text. Consequently, there is a need to use special techniques that “slow down” reading, help to keep attention, and make the reading process interactive.

The easiest way to keep attention is to break the text into small fragments and invite the student to write answers to the questions posed to the text.

There is an opinion in the pedagogical environment that a good teacher is not the one who explains well, but the one who knows how to ask interesting questions. However, the art of "questioning" is important not only for the teacher. Students should be encouraged to ask their own questions about the text. Soviet psychologist L.P. Doblaev wrote: “The first and main method of independent understanding of the text is to pose questions in front of oneself and search for answers to them.”

There are quite a number of strategies for dealing with questions while reading a text.

As part of the technology for the development of critical thinking through reading and writing, all questions were divided into "thin" (requiring an unambiguous answer) and "thick" (requiring a detailed answer).

Text strategy

Table “Who? What? When? Where? Why?"